Holly Tucker's Blog, page 94

September 27, 2011

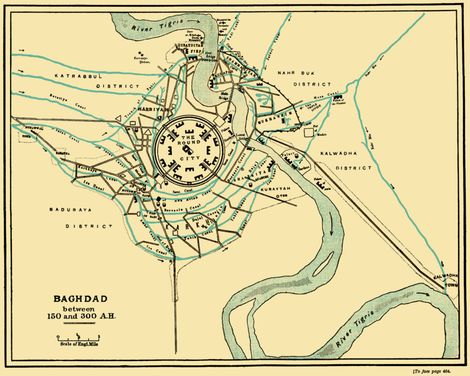

Building Something New In Baghdad

By Pamela Toler

Today we think of Baghdad in terms of tyranny, terrorism and mistakes. A sinkhole for American troops. A sandbox for suicide bombers.

In the eighth century, Baghdad was the largest city in the world–and the most exciting. Like Paris in the 1890s, Baghdad was a cultural magnet that drew scientists, poets, scholars and artists from all over the civilized world. (Just for the record, that didn't include Europe, which was having a bit of trouble on the civilization front in the centuries after the fall of Rome.)

Baghdad was a brand new city, built to replace Damascus as the capital of an Islamic empire that was no longer the sole property of the Arab tribes. The Abbasid caliph al-Mansur had his architects draw the outer walls of his new capital in a perfect circle, using the geometric precepts of Euclid.

Baghdad was a brand new city, built to replace Damascus as the capital of an Islamic empire that was no longer the sole property of the Arab tribes. The Abbasid caliph al-Mansur had his architects draw the outer walls of his new capital in a perfect circle, using the geometric precepts of Euclid.

Completed in 765, the Round City grew quickly. Within fifty years, it had a population of more than a million people: Muslim and Christian Arabs, non-Arab Muslims, Jews, Zoroastrians, Sabians and an occasional Hindu scholar visiting from India. It had separate districts for different trades, including a street devoted to booksellers and papermakers.

Most important of all, Baghdad had libraries. Encouraged by an official policy of intellectual curiosity, scholars in Baghdad collected works of literature, philosophy and science from all corners of the empire. (Baghdad reportedly negotiated for a copy of Ptolemy's Megale Syntax as part of a peace treat with Byzantium.) Ambitious nobles followed the caliphs' example and created their own libraries, many of which were open to scholars. Working in a culture that encouraged learning, Abbasid scholars in the eighth through the tenth centuries not only transcribed and translated the classical scholarship of Greece, Persia and India, they transformed it, pushing the boundaries of knowledge forward in mathematics, geography, astronomy and medicine.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

September 26, 2011

An Unusual Political Marriage

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt, Professor and Chair, History Department, Cleveland State University

She was twenty-three years old when surprising news reached her in the city of Segovia in 1474. Her half-brother, Enrique IV, the King of Castile, had died. She was the lawful heir to his throne—the new sovereign ruler. She was also married. In 1469 she had wed the presumed successor to the kingdom of Aragon, Fernando. She was, however, alone in the city of Segovia when she received the news of Enrique's death; Fernando was traveling in Aragon. In Castile Isabel faced a restless nobility and a competitor for the throne, Enrique's daughter, Juana. Despite her legal rights to the realm (Castile had nothing like the Salic Law of France that excluded women from succession to the throne), she had to contend with a culture that viewed the political power of women warily or even with outright hostility. Many probably expected her to turn the reins of power over to her husband.

But she didn't. Instead, recognizing the power of swift, decisive action, she quickly staged an acclamation ceremony and did not wait for him to arrive and participate. She dressed herself regally and processed through the streets of Segovia. According to at least two chroniclers, she had a member of the nobility walk ahead of her, carrying an unsheathed sword, long-identified as the symbol of justice. One of these chroniclers found this highly unusual, condemning her ostentatious presumption when such an action was more appropriately her husband's prerogative. The other defended her, saying it was her right. Even if Fernando had been present, he argued, it was still appropriate that the sword accompany her, since she was sovereign ruler of Castile.

Her husband, Fernando, was less sanguine. Upon hearing the news of the ceremony and her use of the sword, he reportedly remarked to one his courtiers how strange it was for her to employ such a "manly attribute." When the two were eventually reunited in Segovia, Fernando's displeasure prompted a re-negotiation of their marriage contract. Curiously, despite the fact that his anger had been the catalyst, Isabel retained significant rights and privileges in the kingdom she had just inherited. The two would share some powers, but her precedence in Castile was clear.

In these battles for power, the reign of Isabel and Fernando reveals a curious mix of gender and politics that would continue to characterize their joint reign until her death in 1504.

I have lots of stories about the unusual political marriage of Isabel and Fernando—let me know in the comments if you'd like to hear more in future posts.

Q&A: Christine A. Jones

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Christine Jones. Christine's first post for Wonders & Marvels was on the Porcelain Trianon at Versailles.

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Christine Jones. Christine's first post for Wonders & Marvels was on the Porcelain Trianon at Versailles.

Q: It's always so interesting to learn about how people end up where they end up. What has been your trajectory? Did you always know that you wanted to be a college professor? Where you always certain that you wanted to specialize in 17th and 18th century material culture?

A: Nothing that I've done has been planned. It all seemed to choose me. I had no idea I wanted to be a college professor. All I knew when I got a taste of college-level thinking is that I needed to figure out how to keep doing it. My B.A. is in philosophy, but I gravitated towards the literary expression of philosophy, especially Absurdist theater. I got away with writing a senior thesis on Samuel Beckett, but my mentor made clear that to go further, I would need to work in a literature grad program. Suddenly I was a literature student! The long story short is that my stint as a 20th-centuryist lasted through the M.A., but once I took an 18th-century seminar the first year of my PhD I was hooked. So, no, I was never certain. If you told me when I started grad school that I'd be writing about Enlightenment material culture now, I'd have laughed and said, "What's that?"

Q: Your most recent work has been centered on the history of porcelain making in France. Could you tell us a little more about that? What have been some challenges of working in this field (besides the fact that it must be frightening to actually hold some of that precious and fragile porcelain!)?

A: Most frightening for me about 18th-century porcelain (which I have never held!) was how alien the world of museums and art history were for me as sites of study. I worked in libraries and preferred to be a spectator at museums. And I never set out looking for porcelain. It showed up innocently in a literary study I was working on—a fairy tale—but before I knew it, books on tea cups and chocolate pots were all over my shelf. The story of how French artisans struggled with clay and with the state to make France a world leader in porcelain had never really been told. And after a few years of reading excitedly through archives and teaching myself the basic science of ceramics, I decided to tell it.

Q: You and I have been working together for several years now as writing partners. We talk a lot about what it means to be a writer and what is (at least it was for me) a long process of developing into a "writer" after spending years preparing to be a "professor." What has your journey been like? What advice would you share with readers?

A: I'm so hooked on writing partnerships (and the joy of working with you is the reason I took to it so fast!) that I don't want to write in isolation anymore. My journey to a writing practice came very late in my career as a professor—after tenure. It's not that I did not write, but I did not write with the best part of me and I did not always write for me. The institution made me goal-oriented rather than idea-oriented for a long time. Instead I excelled at Socratic teaching and mentoring—the performing arts of academe—and wrote on the side, essentially as a professional obligation. Now writing feels like a performance art, albeit with a time delay, and I strive to go public with my ideas. The advice I'd share? The longer writer goes unshared, in my experience, the harder it is to share it and the more shattering it feels to get criticism (even constructive criticism) on it. Academics are under so much pressure to be smart and intuitive and innovative that putting ideas out there can feel paralyzing. But it's precisely through sharing that the pressure diminishes, especially if you can swap first with someone you trust.

Q: And as always, the predictable question: If you could show up unannounced in some past moment, where would you go? Who would you see? What would you do?

A: When I was asked what figure in history I'd like to meet at the age of 18 during my interview for a Presidential Scholarship at Villanova my answer was Lizzie Borden. That answer was memorable, if a bit daft, especially for the priests in the room, and I ended up getting the scholarship that enabled me to go to college. Today I think I'd opt to meet people who did NOT make history. Ceramics artisans tinkering formulae in dirty Parisian ateliers and trying to beat the Chinese at their own game of course come to mind. Did they have any idea that they might make history? What did it feel like to invent something and then have a king take credit—and profit—for it? Did they think they were da Vinci, or were they just glad to make enough money to eat? How bad was the stench in trade environments in an 18th-century city? These are things I'd like to experience—with the caveat that I could come back and get 21st-century food and medical attention when it was over.

Q: And the unpredictable one: Is there a past moment that you would never want to experience?

A: Epic wars rank high among things I'd prefer to avoid. But maybe the Crusades are at the top of that list, partially because they so cleanly and frighteningly aligned human destruction and salvation. At least the Romans knew it was sport. But to kill and be killed to liberate the soul from the body—this is the mindset of a community that is capable of embracing, and therefore recklessly inflicting, pain to a degree that I find incomprehensible. In other words, it's not just their lack of antiseptics and analgesics that terrifies me, but also the fact that there was something spiritually desirable about bodily suffering—causing pain could even earn you points in heaven. Not that we're entirely over that theory, especially in the current American political climate, but what we call gruesome now probably doesn't hold a candle to what the average 13th-century soldier on both sides of the moral divide lived every day.

September 24, 2011

The Architecture of Romance

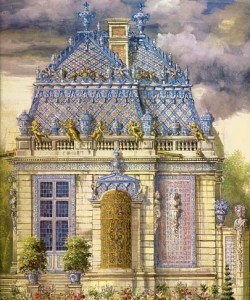

La Maison de Trianon, 1671-1687 (reconstruction)

By Christine A. Jones (W&M Contributor)

Not long after the construction of the legendary Taj Mahal, Louis XIV built a monument to passion, but it was not for his wife, Queen Maria Theresa. Over the course of his reign, he fell in love with other women who came to live at Versailles. His second paramour, the Marquise de Montespan, was a stunning social climber that caught his eye in 1666. Montespan's penchant for excess was striking and earned her a dubious reputation at court. The king's sister-in-law, the Duchesse d'Orléans, registered her distain in scathing descriptions. "[...] Montespan was a very capricious creature, who could never restrain herself in any way," and "her ambition exceeded her debauchery." Little wonder that Louis XIV adored her.

The king celebrated their passion in 1670 with an extravagant getaway built at one end of Versailles' Grand Canal. Inspired by the Marquise's taste for luxury, the King commissioned a richly exotic pavilion the likes of which Europe had never seen: its roof was covered in thousands of sparkling ceramic tiles and vessels done in the style of "blue and white" Ming china. Entering the "Trianon de porcelaine" was like walking into a porcelain universe. Inside, tiles covered the floors, painters finished white walls with cobalt blue motifs, and woodworkers contributed identically patterned furniture. Gardens were planted in such abundance that sometimes the scents were overwhelming. Architectural historian, André Félibien, recorded in 1673 that, "everyone found the palace enchanting." It was a fairy-tale castle for a storybook romance.

But don't look for it at Versailles today. During the 1680s, the aging king fell for the devoutly religious Madame de Maintenon, who turned him away from the wanton passions he had shared with the Marquise. Louis demolished the porcelain love shack in 1687 and built the Grand Trianon in marble to immortalize the glory of his reign, which, unlike his love, stood the test of time.

Christine A. Jones teaches French 17th/18th-century literature and culture at the University of Utah. She writes on fairy tales, porcelain, dance, and, most recently, wine.

September 23, 2011

When the Only Safe Sex was with Vampires

By Karen Essex

[image error]When answering questions about my latest novel, Dracula in Love, I am inevitably asked about the sequences that readers find the most chilling and frightening – the scenes in the Victorian insane asylum. Surely those shocking scenarios, like the fantasy scenes of vampirism, are products of the author's perverse imagination? Ironically, the answer is no; the asylum sequences are based on painstaking research. Truth, as it turns out, is always is stranger than fiction.

Dracula in Love retells Bram Stoker's original story from the perspective of the vampire's muse, Mina Harker, and in the process, turns the story on its ear, freeing Mina from her role as "victim," and putting her at the center of her own story. A good deal of Stoker's book takes place in an asylum. I wanted to utilize that Gothic setting in my book, but I also wanted to paint the asylum as it actually would have been at the time – full of women incarcerated for having what we today would consider normal sexual and other desires.

In the course of my research, I quickly discovered that women in the 1890s had more to fear from their own culture than from vampires. I read the psychiatric journals of the period, which prescribed bizarre treatments for ladies who were "hysterical," which usually turned out to mean that they were "excitable in the presence of men." In many instances, the desire to read all day or engage in intellectual studies, were also regarded as symptoms of mental illness in the female. Young women were committed to asylums for doing cartwheels in mixed company, for desiring sex with someone other than one's husband, or for staring seductively at a man. Most behavior that showed spunk, spirit, or sexual need, was pathologized.

All sorts of harrowing and torturous cures were developed to "settle" these women – restraints, forced housework (to help them remember their true natures), repeated plunges in ice water, and force-feeding, to name a few. As mental illness in females was thought to originate in the womb, doctors also were obsessed with menstrual cycles, figuring that if a patient's cycle could be regulated to a strict 28-30 day cycle, the "illness" of wanting to have sex or read books all day, would disappear. Not coincidentally, an irregular cycle was also considered a sign of mental illness and required treatment.

Curious as to whether these "cures" were actually implemented, I visited the archives of Victorian mental hospitals and read physicians' reports from the late 1800s, often in the doctors' own handwriting. Reading of young women committed for losing interest in housework, for lying about sexual encounters, or in one case, of a fifteen year old girl diagnosed with hysteria because she refused to stick her tongue out for the doctor's tongue depressor, was heartbreaking.

Worse yet were the treatments, which often involved restraints to "pacify" the women. Women's "fluttering, nervous hands" were thought to be a sign of hysteria, and the proscribed treatment was confinement – cuffs, muffs, straps, and strait jackets. Psychiatrists figured that if they could only calm the woman's hands long enough, the patient would be soothed, hence, cured. More often than not, after prolonged periods of restraint, women's spirits were entirely broken, at which point, they were allowed to return home. One of the most amusing anecdotes I ran across was the euphemism of "camisole" for the strait jacket because wearing it soothed a lady's nerves in the same way that putting on a lovely garment might.

Think about that next time you slip into a bustier!

Though the Victorian era had its charms and pleasures – and I do explore those as well in Dracula in Love – it was a dangerous time to be a woman. If I were living in that era, I would surely have been committed. And I'm guessing that if you are reading this, you might have been my cellmate.

About the author: Karen Essex is the best-selling author of Dracula in Love, Leonardo's Swans, Stealing Athena, and two acclaimed biographical novels, Kleopatra and Pharaoh. She lives and works in London and Los Angeles. To learn more about Karen's work, please visit her website: www.karenessex.com.

We have five (5) copies of Dracula in Love to giveaway. To enter, simply leave a comment on this post (below). Feel free to answer this question in your comment: What is your favorite book featuring a female character who is either insane or thought to be insane? Sorry, we can only ship winning copies in the US at this time.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

September 21, 2011

Q&A: Lindsey Fitzharris

By Holly Tucker

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Lindsey Fitzharris.

Q: Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Q: Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

A. As a little girl growing up in my grandmother's house, I remember rifling through closets stuffed with oddities from bygone years: a hand-beaded purse from the 1920s with a lady's calling card tucked inside; faded tintypes of sombre relatives placed in front of Victorian backdrops; a suitcase with my grandfather's marine uniform worn on Okinawa in 1945, along with pieces of shrapnel from the battle.

Individually, these 'things' meant very little. Collectively, they represented my family's past – one which was both tangible and enigmatic to a little girl whose curiosity in history went far beyond genealogy. Who were the 'flappers?' What would it have been like to live in the 19th century? Where exactly is Okinawa and why were we fighting a war there?

As my interest in history deepened, I sought knowledge about the past through books. This, however, was never enough, so I found myself at a place that could not only teach me about history, but also allow me to interact with it as I once did in my grandmother's house: Oxford University. There, I fell in love with the history of science and medicine while reading an 18th-century copy of the French Encyclopédie in the Radcliffe Camera.

Today, I am a postdoctoral research fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. My current project focuses on the history of 17th-century surgery. If I am passionate about my subject, I am even more passionate about sharing my work with others, which is why I also began a blog featuring fascinating (and often gory) details about early modern medicine. One day, I also hope to write historical fiction.

Q: What are some of the greatest pleasures of being a historian?

A: For me, the most rewarding part of my job is sharing my knowledge with others. History doesn't have to be dry and boring, like it may have been for some in secondary school. It can be exciting, surprising, even shocking. If I can help make the past come alive, and challenge people's perceptions about the history of medicine while doing so, then I've done my job.

Q: And the greatest challenge?

A. A historian's job may often be interesting, but it is almost never easy. You might start a project with an idea in mind, only to discover that the past is not at all how you imagined it to be. Sometimes, this can be very disappointing. Other times, it can be exhilarating. There is truth in the old adage, "fact is often stranger than fiction."

Q: Finally, I have to ask everyone this: You have one day to spend in the past. Who, what, where, when…and of course, why?

A: I could say I'd like to attend a lecture given by the famous 18th-century anatomist, John Hunter, but that's a bit predictable. Besides, Hunter was a notoriously bad public speaker, and it is likely I would learn little more than I already know from listening to one of his lectures since they have been very well documented for posterity.

Instead, I'd rather get my hands dirty helping the resurrection men dig up corpses for Hunter. Body-snatchers were made notorious by the crimes of Burke and Hare—two murderers who sold the bodies of their victims to surgeons in the 19th century. Besides these two men, however, there is still very little known about the individuals who worked in the dead of night to supply surgeons with the bodies they so desperately needed. Yet, they are a very important part of the history of medicine. I think spending a night with a gang of "sack-em-up" men would be terribly entertaining, as well as enlightening!

Read more about Lindsey's work at http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

September 20, 2011

Contributor Q&A: Tracy Barrett

Another in our series of introductions of new contributors to Wonders & Marvels: introducing Tracy Barrett, award-winning author of books for young readers, both fiction and non-fiction. Lately she has been concentrating on young-adult fiction set in the ancient Mediterranean.

Another in our series of introductions of new contributors to Wonders & Marvels: introducing Tracy Barrett, award-winning author of books for young readers, both fiction and non-fiction. Lately she has been concentrating on young-adult fiction set in the ancient Mediterranean.

Q: You have an A.B. in Classics from Brown University and a Ph.D. in Medieval Italian literature from U.C. Berkeley, you teach Italian at Vanderbilt University, and you're also an award-winning author. Could you tell us a little bit about your career trajectory? How have these two seemingly different lives intersected?

A: Actually, there are many similarities! My favorite activity is poking around dusty old books that nobody else has looked at since 1951, finding an intriguing fact that makes the past come alive, and communicating that fact to a receptive audience. That's what I did when I investigated the medieval poet Cecco Angiolieri for my dissertation, and that's what I do now when I find out something about Bronze Age Crete to round out a character in a novel.

Q: Of the many books you've written, which one has been the most interesting to write?

A: Like most authors, I usually find my most recent book the most interesting, so for me, that would be Dark of the Moon, releasing—ta-da!—tomorrow! It's a retelling of the myth of the Minotaur, which is itself a Greek retelling (or misunderstanding) of now-lost Cretan rituals, most likely concerning the worship of a bull-god, whose priest might have worn a bull costume during rituals. It's possible that Greek travelers garbled the story and came up with the marvelous tale of the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull who devoured human children. Their inaccurate but exciting retelling gave the world one of its most popular myths.

In my imagined Minoan civilization, Crete is ruled by a moon goddess and Asterion is no monster, but a deformed and nearly mindless man who has to be confined under the palace for his own and others' safety. Everyone is terrified of him except his beloved sister Ariadne, and eventually, Prince Theseus of Athens, who has been sent to kill him.

Told in alternating points of view by Ariadne, a lonely teenager who is also priestess of the moon, and Theseus, who has rediscovered his father only to be sent by him to almost certain death, Dark of the Moon explores the issues of love, faith, and betrayal. Ariadne must decide what her obligations are toward her heritage and her religion. Theseus must discover how much he owes his absent father, his neglectful mother, and his kind stepfather. It's been getting some great reviews, including a star from Kirkus Reviews.

I'd love to share the book with you! I'll send signed (or unsigned, if you prefer) copies to two people who comment on this post over the next week.

Q: You're "retiring" from Vanderbilt at the end of this year to focus on your fiction writing. How will you start transitioning to life as a full-time teacher to life as a full-time writer?

A: I'm weaning myself from teaching and amping up my writing while not shortchanging my students and colleagues at Vanderbilt, which means that I'm working at one or the other job pretty much all the time. Life will be difficult for the next seven months, but I care a lot about both teaching and writing too much to want to do less than my best at either one.

I'm blogging about my last year at Vanderbilt at Goodbye, Day Job!. Guest posts alternate with my own posts about preparing to leave a "regular" job with a paycheck, benefits, social contacts, and interesting coworkers (I'm including my students in that group!) for the uncertain world of working for myself. A new post every Wednesday!

Q: I know that you're deeply connected to the YA writer community. What are the benefits of engaging with author writers? And what's the best way for a new author to reach out to others?

A: You're asking this at a very good time. I just spent the weekend at the annual conference of the Midsouth (Tennessee/Kentucky) chapter of the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators, a 22,000-member international organization. As always, the conference was stimulating and educational, but above all a wonderful networking opportunity. Children's writers are the most generous and interesting people I've ever met, and I'm thrilled that I'll be able to spend more time with them. You don't have to be published to join, so if this is something that interests you, I highly recommend that you join.

Q: Inquiring minds want to know. What do you have in the works? What can we look forward to?

A: I'm working on a YA manuscript set in the Roman Empire. It's still too new and fragile to talk about, but it involves an Etruscan slave girl, a mysterious prophecy, a guilty secret, murder, love, teen angst—I'll share more when I think it's sturdy enough to bear a little scrutiny without bruising!

I look forward to posting here on the 20th of every month on all aspects of young-adult historical fiction.

September 12, 2011

Location Research in 140 Characters or Less

By Beth Dunn

I'll be the first to admit that I'm addicted to the internet. I spend pretty much every minute of the day online, unless I'm sleeping, driving, or exercising. But it's not all funny cat videos and screencaps of sexy British leading men in cravats.

It's also surprisingly useful for doing in-depth location research when I'm writing. Social media lets me spend lots of time in lots of different places at once, and more than once, it's helped me decide where to set a story.

You might think that's putting the cart before the horse, but it's not. I'll let my old graduate school advisor tell you why.

Vienna is lovely in the summer

When I was in grad school for geology, lo these many years ago, one of the first things I needed to do was decide where I was going to do my field work. So, being a logical, methodical kind of person, I thought long and hard about what my research interests were, checked the literature, and made a list of topics that I thought might be fruitful for new contributions in the next year or two. Then I made a list of some of that places where that research might be done, and showed it to my advisor.

She scanned my list, sighed deeply, and handed it back to me. Then she asked me a question.

"Where do you want to spend the next five summers of your life?"

I might have blinked. She went on.

"See, I like my creature comforts, I like to know I can get a decent hotel room and a good meal, so I do research in Europe. I've done field work in the desert, and I hated it. If I read my dissertation now, I'd be able to feel the sand grit between my teeth again in an instant, and I'd want to punch something. If you want to love your work, choose a place that you love. Trust me: There are interesting questions to answer everywhere."

I glanced down at my carefully assembled list. Only one of the places I had come up with even sounded slightly appealing to me, on reflection.

"Vienna," I said.

She smiled. "Vienna is lovely in the summer. And the museum is open later than most. Excellent. Write it up. I'll see you next week."

So I did my field work in Vienna.

Now, I ended up not pursuing the life of a paleontologist, as you've probably already guessed. But my advisor's words have stayed with me. It sounds frivolous on the face of it, but obviously she was right — if you're going to be spending lots of time in a particular place (real or imagined), you'd better be damn sure you like it there.

But as a geologist, I needed to physically visit a place in order to research it. Nobody else was going to climb those mountains and bash a rock hammer against some limestone and ship it home for me. I needed to get on the plane and do it myself.

Fiction writing leaves us a few other options. Writers have long used other books, of course, to research their locations. Maps, timetables, local histories, biographies — the list goes on, and it's a familiar one.

But the internet opens up a whole new world for location research. Social media — Twitter in particular — has been phenomenal in helping me better understand a place I've never been before, often in very fine detail.

Twitter is great for field research

My stories take place in England, so I maintain Twitter lists of a bunch of different groups of people, all composed of Twitterers based in England. I follow a Bath list, a Bristol list, a London list, and a Yorkshire list of folks on Twitter, because I'm currently writing stories that take place in those locations.

I can hear you scoff: Just how helpful is it to know what people in Bath are having for lunch? Or to learn that there's a chronic problem with rubbish collection in Norwich? Or that traffic is absolutely mental today on the M1?

Well, it's actually a lot more helpful than you might think.

First, listening in on conversations on Twitter gives me a great sense of the vernacular of a place. You'd be surprised how well regional differences in speech come through in just 140 characters. And how little these cadences are likely to have changed over time.

Second, I can ask questions about simple things if I'm curious. Folks are usually happy to reply to things like "How long a walk is it from the High Street to the waterfront?" or "What's the weather usually like there at Christmas?"

Third, I've now got friends I can meet up with when I do buy that plane ticket and do the serious, hands-on research. And there's nothing like knowing a local for really getting a feel for a town. I've met up with teachers, librarians, baristas, and garbage collectors in my travels.

I can assure you, garbage collectors give excellent street tours.

Social media is great for meeting people, forming relationships, and establishing professional ties. But it can also give you an ear to the ground in a bunch of different locations at once, providing you with an unmatched opportunity to get a sense of a place, an insider's view of a town, and a local guide when you're passing through.

It's like remote sensing for writers. I dig it.

How do you use social media — or even just the internet in general — to help you in your research?

September 11, 2011

Contributor Q&A: Beth Dunn

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Beth Dunn.

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Beth Dunn.

Q: Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

A: I'm a writer in both my day job and my night job, which is a pretty nice thing to be able to say. My fulltime job is writer, editor, and community manager for HubSpot, a marketing software company in Cambridge, MA. And when I go home at the end of the day, I open my laptop right back up again and start writing historical romance novels — mostly Regency romances, although I occasionally stray into the Victorian era, too, which was my first love. I was raised on Jane Eyre and Little Women, and all my fantasies when I was younger somehow involved me wearing a hoop skirt. But then I discovered Georgette Heyer, realized what a ridiculous amount of fun the Regency era is to roll around in, and before I knew it, I was writing my own stories and reading them to my friends.

Q: What are some of the greatest pleasures of writing historical romance?

A: The best thing about writing historical fiction is that I get to take people from hundreds of years ago and try to make them real to people today. Not real as in oh yes, I see that this was a thing that occurred, but real as in Oh my God, I feel EXACTLY the same way, that's ME you're talking about. I mean, that's how I reacted to Jane Eyre and Jo March, and so did millions of other girls. I love the idea that I can connect with a reader in that way, if I get it just right. Of course, it's also an unmissable opportunity to finally write down all of the frankly hilarious conversations that are constantly going on inside my head. I used to be afraid of writing dialogue, but then I realized that I just needed to write down what those people in my head were nattering on about. I know that makes me sound kind of borderline and possibly in need of medical care, but whatever. Call the ambulance: I'm a writer.

Q: And the greatest challenge?

A: Well, my sense of humor can be very modern, kind of all crackly and smart-alecky, which to some ears might sound a little different from what they might expect to get out of a traditional Regency romance. But there's actually a great community of really funny historical romance writers out there now, and it was when I finally read some of their work that I thought oh good, maybe I can do this too. I realized then that I could write in my own voice. And so that's what I do, while maintaining my love and respect for the historical conventions of the time.

Q: Earlier this year, you headed to London with some specific objectives in mind. What did you do?

A: Well, it's funny, my relationship with London. I went there two years ago with my friend Melissa, largely because we wanted to see , who had just played Rochester in that great 2006 version of Jane Eyre. He was playing the lead in The Real Thing, at The Old Vic. It was magnificent, and we actually got to meet Toby afterwards, and a bunch of other amazing actors who happened to be there that night, too, so we were literally brushing elbows with and and and . For a fan of period drama, which obviously I am, it was all pretty startling. I mean, these actors have played some of the most beloved characters from Regency fiction, and there I was, standing in line with them for the restroom and chatting away.

So this time around, we wanted to try to visit some of our favorite places from these books that we loved. So we took a guided walking tour of Regency London, in and around the gentlemen's clubs and tobacconist shops of St. James's Square; we spent a few nights in Bath and visited the Assembly Rooms and the Royal Crescent; we walked the length of the Serpentine in Hyde Park. And I was working on a book at the time that took place partly in Bath, so I actually walked the streets that my characters were walking, which is always an excellent thing to have done. I'm hoping to go north next year, maybe stagger across the moors of Yorkshire and make a Bronte-themed visit of it.

Q: You and I "met" for the first time when we co-organized the Writers for the Red Cross fundraiser, which raised over $30,000 for the Red Cross in just under a month. What's your best memory of that crazy month? How did it change, or reinforce, your thoughts on the writerly community?

A: My best memory of that month was how coolly you carried it all off! It was a massive undertaking that could have very easily spiralled out of control — we had, what, more than 120 authors, agents, and publishers participating, each with their own donations and posts and schedules and fulfillment needs — but you just cranked out spreadsheet after spreadsheet and kept it all running beautifully. The other thing that was amazing about that month was that the terrible tsunamis in Japan took place just as we were getting started, so there was suddenly a real focus for people's involvement and participation. It was wonderful to see how many people wanted to donate — items for auction, services to authors and aspiring writers, and just straight-up cash donations — in the aftermath of all that. The writing and publishing community gets a lot of press these days for being in turmoil, transition, at loggerheads, however you want to put it, but that month showed me that it's an incredibly powerful community of unbelievably generous and helpful individuals. Not that I ever doubted it, but coming into daily contact with tangible evidence of this passion was a terrific experience.

Q: Finally, I have to ask everyone this: You have one day to spend in the past. Who, what, where, when…and of course, why?

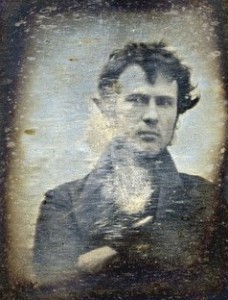

A: I'd go back to Philadelphia, 1839, and find the sidewalk where Robert Cornelius was taking this photograph of himself. It's the first light photograph of an actual human being. Before then, they didn't have the chemical knowledge that would allow them to use a shorter exposure time than, like, an hour. And nobody could sit still for that long, of course. But my man Robert here was a chemist, and he figured it out. I am absolutely in love with this photograph. It's been the wallpaper on my phone for ages now, and I have it saved to my desktop, too. Not only was Robert just sort of casually brilliant in that great way that all the best geeks are, he's also terribly handsome. It's an arresting image, an important piece of photography history, and I'd love to see it happen and meet the man who did it. And then I'd go find Ulysses Grant, my other historical boyfriend, and tell him to lay off the sauce.

A: I'd go back to Philadelphia, 1839, and find the sidewalk where Robert Cornelius was taking this photograph of himself. It's the first light photograph of an actual human being. Before then, they didn't have the chemical knowledge that would allow them to use a shorter exposure time than, like, an hour. And nobody could sit still for that long, of course. But my man Robert here was a chemist, and he figured it out. I am absolutely in love with this photograph. It's been the wallpaper on my phone for ages now, and I have it saved to my desktop, too. Not only was Robert just sort of casually brilliant in that great way that all the best geeks are, he's also terribly handsome. It's an arresting image, an important piece of photography history, and I'd love to see it happen and meet the man who did it. And then I'd go find Ulysses Grant, my other historical boyfriend, and tell him to lay off the sauce.

September 10, 2011

Blogging 101 (or How This Professor Finally Got Smart)

By Holly Tucker

My family and I spent last weekend at the Decatur Book Festival, just outside of Atlanta. On Saturday, I had the chance to talk about Blood Work, to a crowd of just under 200 people. And the following day, I joined the wonderful Maryn McKenna and Tony Martin on a panel about communicating science online.

My family and I spent last weekend at the Decatur Book Festival, just outside of Atlanta. On Saturday, I had the chance to talk about Blood Work, to a crowd of just under 200 people. And the following day, I joined the wonderful Maryn McKenna and Tony Martin on a panel about communicating science online.

Tony opened the panel with a brief overview of his paleontology blog and talked about how online science writing can provide a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the work of researchers. He also stressed that this type of outreach can be an important way to demonstrate to the larger public the relevance of science in our lives.

A former newspaper reporter, Maryn spoke of the way that online writing allowed her to keep her work, and her name, visible to a broad readership while she went underground to write her book, Superbug: The Fatal Menace of MRSA. Her work has paid off. Last year, WIRED magazine offered Maryn a much-coveted gig as one of their premier science bloggers.

I have to admit that when I was listening to Tony and Maryn, I felt like an imposter. I'm not a scientist, like Tony. I'm not an award-winning journalist, like Maryn.

So battling my own insecurities, I truly didn't know what I was going to say when I stepped up to microphone. My first sentence came tumbling out something like this:

"When I first started my blog, I was afraid. As an academic, I was deathly afraid that someone would 'find me out.' That by the very virtue of having a blog, I would be seen as somehow less than serious. So I did everything to remain personally invisible–while crafting posts for a blog, the most visible medium around."

I wonder now, some three years later, why I was so afraid of being "caught." And I wonder now just how well-grounded that fear was in reality for academics like me. Still, I plowed forward.

I wanted to write to a larger readership, rather than the 10 or 12 people in a narrow academic field–which has, regrettably, been too long the case for many Ph.D.s I just had too many good stories about the past to keep them all to myself.

As I was talking about the origins of the blog, I looked over at Maryn. Let's be clear: the only reason why I was in Decatur talking at this panel in the first place was because of her and because of our shared online work.

Maryn and I first "met" a few years ago via Twitter and her own blog. She had recommended me to Marc Merlin, the founder of the Atlanta Science Tavern. The Science Tavern had sponsored a special author track at the Festival, which included my book talk and the blogger panel among others.

When I sat down after my brief presentation, I realized that the last time I had seen Maryn was in Doha, Qatar this past summer. And there again is another wonderful story of online connection.

As editor of Wonders & Marvels, I get a chance to reach out to just about any writer I want who shares a similar interest in history or the history of science. Pulitzer-prize winning Deborah Blum (The Poisoner's Handbook) was one of them.

I have long adored Deborah's work–but was too nervous to make contact with her. But thanks to Wonders & Marvels, I suddenly had an excuse. I asked her to contribute a post related to her new book. Deborah did a fantastic post about the 1920s starlet Olive Thomas's death by poison.

Thanks to this interaction, Deborah and I stayed in touch. She gave incredibly generous feedback on my forthcoming book. We met in real-life in Madison for the first time about a year later. We saw each other again in Florida for a panel at the UCF Book Festival. We continued to correspond. And then Deborah, who was program chair for the World Conference of Science Journalists invited me to present at the WSCJ conference this summer.

From Wonders & Marvels to the Middle East. Oh, the magic of a modest little blog.

Just has this blog has seen so many different iterations over the past years, so have I as a writer and a scholar. I did everything I could at first to make sure that my "secret" would be safe. Now, I am so proud of the community that we have all built here that I have no problem acknowledging to my academic colleagues.

As we speak, I'm up for promotion to Full Professor. I included this website as part of the copious documentation (books, articles, teaching evaluations, statements of endeavors) required for faculty reviews.

Does online engagement help a tenure or promotion case? My guess is no, especially if the core materials aren't there (excellent teaching, fantastic scholarship and publications, plus university service). But can it hurt?

You decide. On Wednesday, my department voted to promote me.

What stories about your own thoughts/interactions/successes do you have about online interactions? And any academics out there? What do you have to day about all of this?