Holly Tucker's Blog, page 93

October 7, 2011

All Hallows' Eve and All Souls' Day

Dusk which falls early, cooler winds which rise, dry leaves rustling around old gravestones. This last day of October, known as All Saints' Eve or All Hallows' Eve (now called Halloween), was a somber season, marking the very ending of the warmth of the earth and the long entry into a cold winter. Its ancient customs are a haunted mixture of Christian and pagan.

Originally celebrated in the middle of lovely May, All Hallows' Eve was only moved to its present drearier date about eight hundred years ago.

It was a religious eve. In some parts of Europe, bells rang out at dusk for departed souls and people lit candles on graveyard tombs and left them burning all night in the darkness and solitude of the cemetery. In rural Brittany, four men would go from farmhouse to farmhouse ringing bells, asking prayers for departed souls. According to Polish custom, ghosts haunted empty churches at midnight. People would courteously leave windows and doors open the next day in case a ghost wished to come in.

All Hallows' Eve is derived from the Celtic Night of the Dead. The Celtic people divided the year by four major holidays. The festival observed at this time was called Samhain (pronounced Sah-ween); the Celts believed that this night, the souls of those who had died this past year were traveling their lonely way to the other world, and thus, for those few hours, division between this mortal world and the world to come all but vanished. Ghosts could walk the world and did.

In medieval England, on the 2nd of November (All Soul's Day), children and the poor went "a-souling," going from door to door to beg for a special little cake, marked with a Cross, called a soul cake. Each cake eaten would free a soul from Purgatory which, if you look at any medieval church painting, was a pretty terrible place. Turnips were also carved into lanterns as a way of remembering the dead. Soul cakes were left in graveyards to feed the dead and prevent any mischief they might be contemplating.

But why were the dead seen as malevolent? Perhaps because they so envied the living who were sitting home by their fires drinking warm ale? Was this the beginning of Gothic horror tales, stories of vampires and the dead arisen?

What do you think?

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

October 6, 2011

Animal trials

By Lynn Ramey (W&M Contributor)

Known for his tragedies, Jean Racine (1639-1699) wrote a single comedy, Les Plaideurs (The Litigants). The play tells the story of lovers thwarted by their parents, inevitably to be reconciled in the end after having tricked the older generation into seeing the folly of opposing their children. In the culminating act, the father, a judge, must rule on the case of a dog, who is accused of stealing and eating a chicken. The puppies come before the judge, and their "attorney" speaks in their voice, asking the judge to spare the dog so that the pups can avoid the orphanage. The judge nonetheless condemns the dog to hang, but his conscience is pricked by the pleas of the puppies, making way for the marriage of the young lovers.

The ridiculous appearance of a dog in court, accompanied by puppies who upset the judge by crying and peeing all over the courtroom floor, was the comic highpoint of Racine's play, but animals in court were a very real phenomenon in France from the 13th to the 18th centuries. The most common offenders seemed to be domesticated pigs who killed small children. In 1606, a female dog was killed and burned alongside a M. Guyart for having had illicit relations, as determined by the dog's testimony. Such trials are found in records dating from 824 (against French moles) up to 1906, when a Swiss dog was condemned to death for his part in a robbery resulting in death (the men involved were sentenced to life in prison).

The definitive book on the subject remains E.P. Evans's The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (London, 1951). While it is hard to imagine imputing criminal intent to the mind of animals, it was somewhat unnerving to come home to find that my own dog had taken this book, and only this book, off my bookshelf to tear apart.

October 4, 2011

Theodora

By Stella Duffy

In 527AD Theodora was crowned Empress of Rome in Constantinople. The daughter of a bear-keeper, she had risen from poverty to become the city's most successful comedian and acrobat. At eighteen she ran away with the Governor of the Pentapolis (modern day Libya), and when he broke off their relationship she travelled to Egypt, where she underwent a religious conversion. She was reviled by contemporaneous historian Procopius for her lascivious stage shows, made a saint in the Orthodox Church for her dedication to the faith, and named 'our most pious consort' by her husband, enabling her to rule when he lay ill during the plague pandemic.

In 527AD Theodora was crowned Empress of Rome in Constantinople. The daughter of a bear-keeper, she had risen from poverty to become the city's most successful comedian and acrobat. At eighteen she ran away with the Governor of the Pentapolis (modern day Libya), and when he broke off their relationship she travelled to Egypt, where she underwent a religious conversion. She was reviled by contemporaneous historian Procopius for her lascivious stage shows, made a saint in the Orthodox Church for her dedication to the faith, and named 'our most pious consort' by her husband, enabling her to rule when he lay ill during the plague pandemic.

This complex woman is immortalised in the mosaics of the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy – a city she never saw.

Theodora is depicted in full Imperial garb, accompanied by an entourage of prominent women. Scholars offer varying meanings the mosaics; they exhibit the powerful stance taken by both Emperor and Empress in their leadership; the Imperial couple are leading the faithful into the Church (standing opposite each other to symbolise their opposing views in an early Christian schism); and perhaps most intriguingly, that a curtain is held open for Theodora because the mosaic may have been completed after her death, her likeness taken from a death mask.

Whatever the truth behind the imagery, the mosaics are now a UNESCO World Heritage site and we are fortunate to have a glimpse of such an astonishing woman, crafted in her own time.

About the author: Stella Duffy has written twelve novels, eight plays, and over forty short stories. Her novels have twice been longlisted for the Orange Prize and she is a recipient of the Crime Writer's Association Short Story Dagger Award. In addition to her writing work she is an actor and theater director. She lives in London with her wife.

We have five (5) copies of Theodora to giveaway. To enter, simply leave a comment on this post (below). Feel free to answer this question in your comment: What is your favorite book featuring a female character who is either insane or thought to be insane? Sorry, we can only ship winning copies in the US at this time.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

Lindbergh and All Those Other Guys

By Richard Bak

Most people know Charles Lindbergh was the first person to fly from New York to Paris, pulling off what essentially was a stunt flight in the Spirit of St. Louis on May 20-21, 1927. Generally overlooked is that 91 others had flown across the Atlantic before him, though none had traveled as great a distance or alone. Those early birds included the American crew of the NC-4, a winged amphibious craft that in May 1919 was the first flying machine of any type to cross the ocean, albeit in stages; and the British airmen John Alcock and Teddy Brown, who three weeks later made the first nonstop crossing (a 16.5-hour flight between Newfoundland and Ireland that covered roughly half the distance of Lindbergh's 33.5-hour, 3,600-mile flight) in a giant Vickers biplane.

Most people know Charles Lindbergh was the first person to fly from New York to Paris, pulling off what essentially was a stunt flight in the Spirit of St. Louis on May 20-21, 1927. Generally overlooked is that 91 others had flown across the Atlantic before him, though none had traveled as great a distance or alone. Those early birds included the American crew of the NC-4, a winged amphibious craft that in May 1919 was the first flying machine of any type to cross the ocean, albeit in stages; and the British airmen John Alcock and Teddy Brown, who three weeks later made the first nonstop crossing (a 16.5-hour flight between Newfoundland and Ireland that covered roughly half the distance of Lindbergh's 33.5-hour, 3,600-mile flight) in a giant Vickers biplane.

Lindbergh was part of the competition to win the $25,000 Orteig Prize established to reward the first nonstop flight between New York and Paris, crossing either way. His achievement – and the universal and often mindless idolatry it inspired – have largely overshadowed the other equally brave (some would say foolhardy) airmen who contemporaneously competed for the prize, several of whom either died or were seriously injured in the attempt.

As a group, the scarred, war-weary French pilots were more interesting than their American counterparts. All had large personalities and compelling personal histories. Paul Tarascon flew with one foot, François Coli with one eye. Charles Nungesser's body was so shot up and wired together that it was a wonder that there was enough left of the man to hang all the medals awarded him. These aces were a joy to research and to write about as I rummaged through overlooked French sources to give the familiar Lindbergh story a fresh recital. Along with such U.S. pilots as Richard Byrd, Noel Davis, and Clarence Chamberlin, they were every bit as worthy of the unprecedented fame the boyish Lindbergh received. When it comes to public memory, none was as lucky as Lindy, but that doesn't mean their names should fall away in the slipstream of history.

About the author: Richard Bak is a Detroit-based journalist with a healthy appetite for history. His latest book is The Big Jump: Lindbergh and the Great Atlantic Air Race (Wiley).

We have two (2) copies of The Big Jump to giveaway. To enter, simply leave a comment on this post (below). Feel free to answer this question in your comment: What is your favorite book featuring a female character who is either insane or thought to be insane? Sorry, we can only ship winning copies in the US at this time.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

October 3, 2011

Hidden Animals in the Children's City

By Rebecca Onion

As a historian interested in the way that animals and humans have co-existed, I'm forever on the lookout for animal stowaways—the secret passengers lurking in primary sources. I found plenty in Esther Singleton's The Children's City, published in 1910. This book, intended for young readers, is the story of two bored young New Yorkers, Nora and Jack, whose adult acquaintance Doodle (these were less anxious times) tours them around the city in an attempt to show them that the place where they live is full of interesting things. Doodle, Nora, and Jack visit the Aquarium, the Bronx Zoo, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Botanical Garden. Along the way, they meet an impressive cast of animal prisoners. Doodle's storytelling about these trapped beasties isn't meant to create sympathy, but rather to impress his charges; a modern eye might see things differently.

As a historian interested in the way that animals and humans have co-existed, I'm forever on the lookout for animal stowaways—the secret passengers lurking in primary sources. I found plenty in Esther Singleton's The Children's City, published in 1910. This book, intended for young readers, is the story of two bored young New Yorkers, Nora and Jack, whose adult acquaintance Doodle (these were less anxious times) tours them around the city in an attempt to show them that the place where they live is full of interesting things. Doodle, Nora, and Jack visit the Aquarium, the Bronx Zoo, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Botanical Garden. Along the way, they meet an impressive cast of animal prisoners. Doodle's storytelling about these trapped beasties isn't meant to create sympathy, but rather to impress his charges; a modern eye might see things differently.

There's Silver King, a gigantic polar bear whose transition to captivity didn't go so well ("twenty men worked ten hours before they could get him off the boat and into his den in the Zoological Park…he fought so desperately that they had to chloroform him and it took four pounds of chloroform to make him quiet!") Denizens of the aquarium resist captivity as well, Doodle adds. "Sometimes a fish will refuse to eat for days," Doodle says, "as did the large Moray that came from Bermuda. At one time this great eel fasted for eighteen days, and at another time for twenty-seven, thus causing its caretakers the utmost anxiety." Was the eel sick, or "moping," as Doodle calls it? Either way, the children shouldn't worry—the aquarium has "hospital-tanks" that can deal with the problem.

Then there's Lopez the Jaguar. Doodle tells the story of how Lopez was captured in Paraguay, then transported on a small boat and "nearly drowned" several times, before saying, confidentially, "I know something about Lopez that does not speak well for his character." Lopez had killed a female jaguar that was put in his cage. "The murder was fully premeditated," Doodle adds to his wondering audience. "As a consequence of this act of treachery, Lopez will live in solitude the remainder of his life." How is this "living in solitude" very much more of a punishment than being trapped indefinitely in a zoo? Doodle doesn't say.

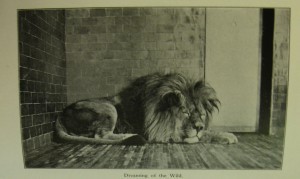

Plate from Esther Singleton, The Children's City (New York: Sturgis & Walton, 1910)

Rebecca Onion is a graduate student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently finishing up a dissertation about popular science and American childhood. Her research blog, Songbirds & Satellites, is at www.rebeccaonion.com

October 2, 2011

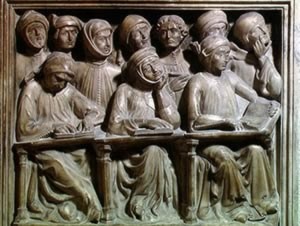

On the Shortcomings of University Students

By Marri Lynn (W&M Contributor)

It's become a commo n conceit to think that the disappointing student is a modern invention. Lecture-halls filled with napping students and dull eyes are, we often think, the lamentable but inevitable result of such distractions as Facebook, cell phones, and the devaluation of education for education's sake.

n conceit to think that the disappointing student is a modern invention. Lecture-halls filled with napping students and dull eyes are, we often think, the lamentable but inevitable result of such distractions as Facebook, cell phones, and the devaluation of education for education's sake.

We may take heart – or despair at the persistence of the habits of the errant student — in learning that these complaints are as old as university education itself.

The Franciscan Alvarus Pelagius turned his talent for social critique (honed in penning De planctu ecclesiae libri duo, a prose campaign for curbing ecclesiastical excess) toward his experiences of students, resulting in a short but pointed tract. The university students that Pelagius complained of numbered among a select few afforded the privilege of attending university in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

It was a privilege and an historical moment which, according to Pelagius, was completely wasted on them.

These students were opinionated, ignorant partiers who engaged in gambling and drinking with more gusto than they ever applied to their education. If they bothered to go to class, they were merely physically present, letting the words of their educated masters flow in one ear and out the other. The exception to this rule was when "forbidden sciences, amatory discourses, and superstitions" (timeless student favorites) came up in a lecture; these the student would learn avidly, when they should be ignored.

Students skipped church, choosing to "gad about town with fellows." When they did deign to attend church, it was to see girls and exchange stories, not to worship – a fact which seemed to especially displease Pelagius.

Above being merely self-destructive, these students harmed others: When they weren't shirking their spiritual duties or studying amatory discourses, they were busy trying to entangle themselves in the gears of the university administration by forming illicit students' societies and fraternities in order to promote their favorite professors on the basis of personal affection and whim. And, of course, they would take their expense money from parents and spend it in taverns and games, only to eventually flee the university (with outstanding fees), bereft of knowledge, conscience, or money.

Those students of the twenty-first century who do not rise above the lowest common denominator are, at least, keeping a centuries-old tradition alive.

Marri Lynn is a Master's student in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal. You can find out more about her other projects at her About.me page.

September 30, 2011

Contributor Q&A: Lynn Ramey

As you may have seen, we're adding some contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them, so we're planning on doing a Q&A (like the one below) with each new contributor. This time around, we're hearing from Lynn Ramey.

We're so glad you're joining us at Wonders & Marvels. Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

I'm a professor of French literature at Vanderbilt University, specializing in the Middle Ages. I also venture into film studies and 16th century studies, especially if it has some medieval connection.

What made you decide to go into Medieval Studies? Was there a moment when you just knew that you wanted to study this period?

There was definitely a moment. I was taking a class with an amazing professor, Stephen Nichols, at the University of Pennsylvania. He included art and culture in his lectures (something very few other professors did at that time), and I was hooked. This choice was really confirmed for me as a graduate student when I visited the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and got to order manuscript after manuscript from the vaults to look at the text and illuminations. Back in the day you could actually touch the manuscripts themselves, and it was unbelievable to me that they were so beautiful and so relatively new looking even though they were at least 800 years old.

You're embarking on some really interesting projects in the Digital Humanities. What types of things are you thinking about right now?

Perhaps since the things that made the Middle Ages come alive for me were so visual and tactile, I am still drawn to that and to making the Middle Ages come alive for my students. Currently I'm working on a site devoted to pre-modern travel that will allow visitors to really experience what it might have been like to move from place to place circa 1000-1500. Getting into the Viking longboat, feeling and hearing the seas, experiencing the sagas sung by the campfire at night…

One thing that many people don't know is that you started your academic career as an engineer. What an interesting shift!

I think I never fully left my scientific roots behind! Computers have been a passion for me since I got my first IBM jr in college. No hard drive, just double floppies. It was great. Thanks to the fact that the only study abroad for engineers that Penn had was in France, I also fell in love with French culture, but I didn't really think of that as a career. Got my first job as a programmer working by myself in a converted utility closet, and I was out of there in a couple of weeks. Made the shift to humanities and haven't regretted it.

And the question I love to ask everyone: Imagine you get to step back in time for a day. Where would you go? What would you see? Who would you meet?

Thank goodness I don't actually have to pick because that would be so hard. I mean, who wouldn't want to see the dinosaurs? But high on the list would be the 12th century court of Eleanor of Aquitaine in the hopes of getting a glimpse of Chrétien de Troyes or Marie de France, since we know so little about these writers. To drink in the medieval court atmosphere at its apogee– that would be amazing!

September 29, 2011

Ottoman Bank Bombing in 1903

By David Abulafia

Dubrovnik, credit David Abulafia

Salonika, now known as Thessaloniki, was one of the great Mediterranean cities in which Jews (forming the majority, and still speaking the Spanish of their ancestors expelled from Spain in 1492), Christians and Muslims lived side by side, but increasing nationalism eventually created powerful tensions between the different communities.

In the 1890s radical Macedonian Slavs, who spoke a form of Bulgarian, organised themselves around the 'Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation' (IMRO), seeking autonomy for the wide swathe of Ottoman provinces between Salonika and Skopje; but they saw Salonika as the obvious capital, and they were intent on giving these lands a Bulgarian cultural identity. This was intolerable to the Greeks of Salonika, who obliged the Turks with information they picked up about the activities of IMRO.

Before long IMRO decided that the time had come for drastic action. In January 1903 IMRO agents acquired a small grocery shop opposite the Ottoman Bank, staffed by a dour Bulgarian who seemed unwilling to sell the exiguous stock he displayed. At night, though, the shop came to life, as an IMRO team burrowed under the road, placing mines under the handsome edifice of the Ottoman Bank. The tunnellers were almost caught, because they had blocked off one of the city sewers that lay across their path, and the Hotel Colombo, nearby, complained that its plumbing had ceased to work. On 28 April they set off their bombs, demolishing the bank and several neighbouring buildings.

About the author: David Abulafia is Professor of Mediterranean History at Cambridge University and the author of The Mediterranean in History.

We have three (3) copies of The Great Sea to giveaway. To enter, simply leave a comment on this post (below). Sorry, we can only ship winning copies in the US at this time.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

September 28, 2011

Research at 13,000 Feet: The Incan Agricultural Legacy

This summer, I spent a few weeks traipsing around Peru, in part to learn more about the agricultural techniques of the Incas. The first two stories from that reporting trip recently appeared, about the ways in which ancient Incan farming practices can help the descendants of the Incas face food insecurity and climate change. The print story was published on the Smithsonian Magazine's website, and a radio story aired on the public radio show The World.

This summer, I spent a few weeks traipsing around Peru, in part to learn more about the agricultural techniques of the Incas. The first two stories from that reporting trip recently appeared, about the ways in which ancient Incan farming practices can help the descendants of the Incas face food insecurity and climate change. The print story was published on the Smithsonian Magazine's website, and a radio story aired on the public radio show The World.

I found this story as I was pulling together ideas for a trip for the radio show I worked for at the time, the World Vision Report (which would also be funding the journey). Then, suddenly, the show was canceled. Still, I remained fascinated by the topics, so I found other interested radio and print venues. In May, I flew off to Peru.

One story in particular grabbed my attention: I read a newspaper article from the 1990s that referenced the work of Cusichaca Trust, a nonprofit founded by British archaeologist Ann Kendall. Kendall and her associates studied Incan agricultural systems in Peru, their terraces, irrigation canals, and systems of planting. And they've been working to bring these systems back to life in the Andes today.

I discovered that the nonprofit had since spun off a local development group, called Cusichaca Andina, and that they were one year into a two-year World Bank grant to fight the effects of climate change. I was struck by the premise that history can help us meet the future.

I'm fascinated by agricultural traditions and history, and the Incas were expert farmers. They had to be; they ruled a gargantuan empire that sprawled over some of the most diverse and at times forbidding ecosystems. And now, hundreds of years later, we're learning that these techniques were significantly more effective in the Andes than anything that has been developed since.

I tagged along with Cusichaca Andina and met development workers, farmers, and construction workers who were rebuilding an ancient irrigation canal. The altitude hit me hard, and the narrow roads that wrapped around the steep mountainside left me breathless with fear. Still, I was able to view first-hand the ways in which local communities are learning from their ancestors. And I ate some mighty tasty potatoes.

About the author: Cynthia Graber is a print and radio reporter who specializes in science, technology, agriculture, and anything else that captures her imagination. Her work has been published/broadcast via a number of venues, including Scientific American, Smithsonian magazine, the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, The World, Living on Earth, and a variety of children's magazines. She's a recipient of the AAAS Pinnacle of Excellence award for science journalism. You can read more at http://www.cynthiagraber.com.

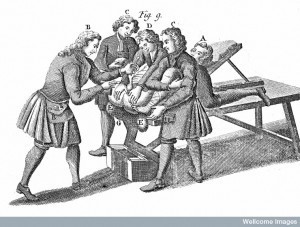

Cutting for the Stone: the Case of Stephen Pollard

By Lindsey Fitzharris (W&M Contributor)

If you visit the Gordon Museum at Guy's Hospital in London, you will see a small bladder stone—no bigger than 3 centimetres across. Besides the fact that it has been sliced open to reveal concentric circles within, it is entirely unremarkable in appearance. Yet, this tiny stone was the source of enormous pain for 53-year-old Stephen Pollard, who agreed to undergo surgery to remove it in 1828.

Many people suffered from bladder stones during the early modern period. Depending on their size, these stones could block the flow of urine into the bladder from the kidneys; or, they could prevent the flow of urine out of the bladder through the urethra. Either situation was potentially lethal. In the first instance, the kidney is slowly destroyed by pressure from the urine; in the second instance, the bladder swells and eventually bursts, leading to infection and finally death.

Bladder stones were unimaginably painful for those who suffered from them during this period. Many acted in desperation, going to great lengths to rid themselves of the agony. In the early 18th century, one man reportedly drove a nail through his penis and then used a blacksmith's hammer to break the stone apart until the pieces were small enough to pass through his urethra. [1]

It is not a surprise, then, that many sufferers chose to undergo surgery. Although the operation itself lasted only a matter of minutes, lithotomic procedures were painful, dangerous and humiliating. The patient—naked from the waist down—was bound in such a way as to ensure an unobstructed view of his genitals and anus [see illustration]. Afterwards, the surgeon passed a curved, metal tube up the patient's penis and into the bladder. He then slid a finger into the man's rectum, feeling for the stone. Once he had located it, his assistant removed the metal tube and replaced it with a wooden staff. This staff acted as a guide so that the surgeon did not fatally rupture the patient's rectum or intestines as he began cutting deeper into the bladder. Once the staff was in place, the surgeon cut diagonally through the fibrous muscle of the scrotum until he reached the wooden staff. Next, he used a probe to widen the hole, ripping open the prostrate gland in the process. At this point, the wooden staff was removed and the surgeon used forceps to extract the stone from the bladder.

Unfortunately for Stephen Pollard, what should have lasted 5 minutes ended up lasting 55 minutes under the gaze of 200 spectators. The surgeon, Bransby Cooper fumbled and panicked, cursing the patient loudly for having "a very deep perineum," while the patient, in turn, cried: "Oh! let it go; —pray, let it keep in!'"

When Thomas Wakley heard of this medical disaster, he railed against Cooper in The Lancet, accusing him of incompetence and implying he had only been appointed surgeon to Guy's Hospital because he was the nephew of the well-known surgeon, Sir Astley Cooper. Later, Cooper sued Wakley for libel. The judge reluctantly awarded him £100 in damages. [2]

But Cooper's reputation, like his patient, never recovered. Sadly, Pollard survived the surgery only to die the next day. His autopsy revealed that it was indeed the skill of his surgeon, and not his alleged "abnormal anatomy," which was the cause of his death.

2. Thomas Wakley, A Report of the Trial of Cooper v. Wakley (1829), pp. 4-5.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.