Holly Tucker's Blog, page 91

November 11, 2011

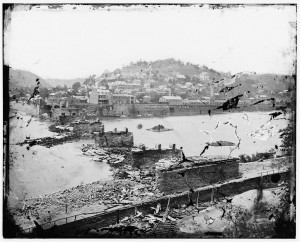

Crossing the Bridge With John Brown

Ruined railroad bridge at Harper's Ferry, W.Va., 1862.

By Brook Wilensky-Lanford (Wonders & Marvels Contributor)

Recently, I reviewed Tony Horwitz's new book, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War, for the San Francisco Chronicle. As history readers, you probably know Horwitz's previous work Confederates in the Attic, telling the Civil War story through its modern-day re-enactors, or A Voyage Long And Strange, following in the footsteps of pre-Mayflower explorers.

In these books, Horwitz writes in the first person, dramatizing historical events through his own physical presence. Someone once said the job of the writer is to build two bridges: between yourself and the subject, and between the subject and the reader. For Horwitz, the two bridges were the same. He let you in on his own experience discovering the subject.

But Midnight Rising, an account of the life, defeat, and eventual martyrdom of the revolutionary abolitionist John Brown, is entirely in the third person. In the prologue, he explained: "I could tread where Brown's men did, glimpse some of what they saw, but the place I wanted to be was inside their heads." It's always impressive when a seasoned writer tries out new things, and it got me thinking about my own process.

My own book, Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, covers almost 200 years of history. Several people advised me to write it in the first person. But it just didn't seem right–I wasn't there in 1881, when the first president of Boston University said that the Garden of Eden had been at the North Pole! Like Horwitz, I was less interested in commenting on my characters than in trying to get inside their heads.

I ended up compromising: the first three sections are in third-person, and the final section, in the present, is in the first person. But Midnight Rising makes me wonder about this. In his acknowledgements (which I always read first!) Horwitz mentions crossing the bridge at Harper's Ferry by night, as Brown's men did. So he did go and do all the on-the-ground research, he just didn't include it as part of the narrative.

Would you ever put yourself in a story about the past? If so, when? And how does your on-the-ground research inform your in-the-past storytelling?

Brook Wilensky-Lanford is the author of Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, which was a New York Times Editors' Choice in August. Her reviews and essays have appeared in Salon, Lapham's Quarterly, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Boston Globe. A graduate of Columbia University's nonfiction writing MFA program, she lives in New Jersey.

November 9, 2011

The Prince of Evolution

By Lee Alan Dugatkin (Atlanta Science Tavern Guest Blogger)

"… [He is] that beautiful white Christ which seems to be coming out of Russia… [one] of the most perfect lives I have come across in my own experience." - Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde was not the sort of man prone to effusive compliments. Who could possibly have merited such glowing praise from Wilde's typically satirical, razor-edged pen? That perfect life, the White Christ, belonged to a quite remarkable Russian scientist, explorer, historian, political scientist, and former prince by the name of Peter Kropotkin.

Oscar Wilde was not the sort of man prone to effusive compliments. Who could possibly have merited such glowing praise from Wilde's typically satirical, razor-edged pen? That perfect life, the White Christ, belonged to a quite remarkable Russian scientist, explorer, historian, political scientist, and former prince by the name of Peter Kropotkin.

Prince Peter Kropotkin was one of the world's first international celebrities. He was known as a brilliant scientist, famous for his work on animal and human cooperation, and on his role as a founder of anarchism. Tens of thousands of people followed Prince Peter during two speaking tours that took him around America. Kropotkin's path to fame was labyrinthine, with asides in prisons, breathtaking 50,000-mile journeys through Siberia, and banishment from most respectable Western countries of the day. In Russia, he went from being Czar Alexander II's favored teenage page, to a young man enamored with the theory of evolution, to a convicted felon and jail-breaker, eventually being chased halfway around the world by the Russian secret police.

Somehow Kropotkin found the energy to write books on a dazzling array of topics: evolution and cooperation, ethics, anarchism, socialism and communism, penal systems, and the coming industrial revolution in the East to name a few. Though seemingly disparate topics, a common thread – Kropotkin's scientific law of mutual aid, which guided the evolution of all life on earth – tied these works together. Just like in the animals he watched for five years in Siberia, Kropotkin saw human cooperation as ultimately being driven not by government, but by groups of individuals spontaneously uniting to do good, even when they have to pay a cost to help.

Dr. Lee Alan Dugatkin is a Professor of Biology at The University of Louisville. His latest book is a history of science page-tuner entitled The Prince of Evolution: Peter Kropotkin's Adventures in Science and Politics .

November 8, 2011

Contributor Q&A: Marc Merlin, Atlanta Science Tavern

From Holly: Marc Merlin and I first met when he asked me to do a Skype Book Talk about Blood Work for his fantastic group, the Atlanta Science Tavern. I had a chance to meet so many interesting people, who were all fascinated by the history of science (among other things). We met in real life in September at the Decatur Book Festival, where I gave a talk to a standing-room only crowd (thanks to Marc's great PR work) and also sat on a panel about social media in science writing. These experiences were so great that I wanted to continue collaborating with the Atlanta Science Tavern–and what better way than to ask Marc to help us feature the great work of its members and its speakers.

Q: Could you tell us a little bit more about the Atlanta Science Tavern?

Q: Could you tell us a little bit more about the Atlanta Science Tavern?

A: The Atlanta Science Tavern began as a science pub early in the summer of 2008 in the tradition of the science cafe movement whose goal it is to bring researchers into conversation with the general public in informal settings. Because of the reach of the social networking site Meetup.com the group has grown to include over 1,500 members and has become a significant public science forum in its own right, producing 2 or 3 events of our own each month and partnering with other organizations, such as the Decatur Book Festival and the Atlanta Botanical Garden, to bring educational programs of all stripes to our expanding audience of science enthusiasts.

Q: What is your own background? And what motivated you to create this great group?

Q: What is your own background? And what motivated you to create this great group?A: My fascination with science began when I was a child and eventually led me to study physics in college and graduate school with the (unrealized) goal of becoming a researcher myself. Over the years, while pursuing a career as a computer programmer, I became very involved with human rights work and similar progressive causes. Although the Science Tavern was created by my friends Josh Gough and Carol Potter, I joined not long after it started. I took on the role of lead organizer in order to expand the program to meet the growing demand for science-related activities like the ones we offer. I see the Science Tavern as a natural extension of my long-standing commitment both to science and to social activism, and I consider myself now a full-time "science activist".

Q: What types of posts do you have in store for us?

A: Our posts will draw on the wide variety of topics featured in our Science Tavern program – evolutionary biology, physics, medical science, anthropology, paleontology, and neuroscience, to name a few – and will relate these subjects to historical personalities or periods of general interest.

Q: And the perennial question, if you could go back in the past, where would you go? Who would you meet? And why?

I hope this isn't considered a dodge, but, given the opportunity, I would travel back in time to Atlanta, Georgia in 1967 to talk with my father. He died the following year when I was only 13, and I never had the opportunity to engage him in a adult conversation of any sort. I imagine that much of my interest in science and curiosity about the natural world originated with him, so it would be a joy for me to bring him up to date about all the amazing discoveries that have been made in the last 45 years.

November 7, 2011

The Uses of Snake Venom in Antiquity

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Despite the perils of handling deadly snakes, arrows steeped in snake venom were the most popular—and the most feared—biological weapons in the ancient world. The deep antiquity of the concept of envenomed projectiles is revealed in Greek mythology, when Heracles dipped his arrows in venom leaking from the dead Hydra Monster. Snake-venom arrows were reported in many historical battles in antiquity. In 326 BC, for example, Alexander the Great encountered lethal arrows in India—the symptoms of his dying soldiers identify the poison as Russell's viper venom. By the fifth century BC, Scythian archers concocted such a nasty arrow poison that their much publicized recipe still has the power to horrify today. They mixed the venom of steppe vipers with blood and dung and left the ghastly glop to putrefy underground. They even painted their arrow shafts to mimic the markings of poisonous serpents.

Snake-handling shamans of the Agari and other Scythian tribes of the Black Sea and Caucasus went far beyond simply weaponizing venom. According to ancient Greek historians, they also possessed the secret of milking snake venom to make antidotes and medicines.

Mysterious Agari doctors were recruited by Mithradates of Pontus, whose Black Sea empire challenged Roman power in the first century BC. As the world's first experimental toxicologist, Mithradates and his international team of investigators sought a universal antidote to neutralize all poisons, by ingesting a cocktail of tiny doses of toxins and antidotes. His regimen calls to mind the principles of immunization.

An astonishing medical milestone, carried out by Mithradates' Scythian doctors, was reported by Appian, a Greek historian of the Mithradatic Wars. Their secret knowledge of venom's beneficial powers saved Mithradates' life on the battlefield and anticipated modern scientific discoveries by more than 2,000 years.

In 67 BC, Mithradates suffered a grievous sword slash to the thigh. Bleeding profusely, he hovered near death, but the Agari staunched his wound with serpent venom. Mithradates recovered and led his army to victory. This is the first documented account of using the coagulating effects of miniscule amounts of steppe viper venom to stop severe hemorrhage, an exciting discovery made only recently by scientists in the new field of "venomics." The ancient Scythian healers would not be surprised to learn that crystallized venom of steppe vipers (Vipera ursinii) from their homeland is now a major export to emergency rooms around the world.

Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World" (2009) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

November 6, 2011

The Royal Miracle

By Gillian Bagwell

The defeat of Charles II by Cromwell's forces at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651 set off one of the most astonishing episodes in British history – Charles's desperate six-week odyssey to reach safety in France, which came to be known as the Royal Miracle because he narrowly escaped discovery and capture so many times.

The defeat of Charles II by Cromwell's forces at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651 set off one of the most astonishing episodes in British history – Charles's desperate six-week odyssey to reach safety in France, which came to be known as the Royal Miracle because he narrowly escaped discovery and capture so many times.

Charles and his ragged and outnumbered army knew that all their hopes rested on the outcome of the day. Their bloody rout ended the Royalist cause. Once Charles had been convinced that the best he could do was survive, he fled as his supporters made a last ferocious stand, and legendarily dashed out the back door of his lodgings as the enemy entered at the front, slipping out the last unguarded city gate.

From that disastrous night until he finally sailed from Shoreham near Brighton on October 15, he was on the run, sheltered and helped by dozens of people – mostly simple country folk and very minor gentry – who could have earned the enormous reward of £1000 offered for his capture, but instead put their lives in jeopardy to help him.

For most of the time Charles was traveling, he was riding with a woman, and disguised as a servant. It was an improbable scheme. He was a noticeable man, six feet two and very dark, yet time after time he rode right under the noses of Cromwell's soldiers without being recognized.

He was in grave danger of capture and death throughout his 600-mile journey (which can be recreated by following the Monarch's Way footpath), but the experience was strongly formative. After his restoration to the throne he told the story frequently for the rest of his life, and the hardships he endured gave him an understanding of the common people such as no other king had had. If he hadn't escaped, England's history would likely have come out quite differently.

Gillian Bagwell's novel The September Queen, the first fictional account of Jane Lane, an ordinary Staffordshire girl who risked her life to help the young Charles II escape after the Battle of Worcester, will be released on November 1. Please visit her website, to read more about her books and read her blog Jane Lane and the Royal Miracle, which recounts her research adventures and the daily episodes in Charles's flight to freedom.

Mozart and Machine Guns

The last time someone shot a machine-gun at me, I remember listening to the ricochets off the nearby rocks and thinking: Mozart sounds a lot better than this. I was crouching behind a concrete block on the edge of the West Bank town of Ramallah and I still don't know if the bullets zinging past were Palestinian or Israeli. I was covering the intifada for Time Magazine and I had taken to soothing my traumatized mind with Mozart's compositions. (Scientific studies have shown that it's good for many other ailments, including attention deficit disorder and epilepsy.)

As I drove home that day, I played his final Jupiter symphony extra-loud on my car stereo to counter the jitters. I suggested to my wife that we take a break to travel to Austria. I wanted the mountains, beautiful cities, and lovely music.

But I stumbled across something that brought me to life creatively in the tiny village in the mountains near Salzburg where Mozart's sister Nannerl lived as the wife of a boring functionary. Nannerl had been almost as talented as her brother, but was cooped up in the mountains while he grew famous in Vienna. As a crime fiction writer, I started to think about her response to his sudden death.

Later, I was dining with Maestro Zubin Mehta, formerly the musical director of the New York Philharmonic. I asked him which of all the great composers he valued most highly. "I'd find it hard to live without Mozart," he said. That started me thinking about those people who had lived with Mozart. After his death at only 35, what had it been like to live without him. To have lost one of the greatest geniuses in the history of the world.

In MOZART'S LAST ARIA I answer Maestro Mehta's question through Nannerl and the music of his last great opera The Magic Flute. The music showed me the great composer's dangerous ideals and the risks he took for them. His sister gave me a character who might uncover them.

Matt Rees is the award-winning author of five crime novels, including MOZART'S LAST ARIA, published Nov. 1 by HarperCollins. A former foreign correspondent, he lives in Jerusalem.

November 2, 2011

Bloody Powerful Stuff

By Marri Lynn (W&M Contributor)

If pad commercials were made in the middle ages, there would be no women in linen dresses running in slow motion across beaches.

If pad commercials were made in the middle ages, there would be no women in linen dresses running in slow motion across beaches.

The next closest thing to these commercials — medieval pseudomedical treatises — presented a very different idea of what women should expect during their time of the month. These books, like the Trotula and others, certainly reveal the expectations of men, who more frequently wrote, possessed, and read these works.

Because of a woman's humoural qualities, being both wetter and colder than men, she suffered from being unable to fully digest her food. Thus, Nature in her genius, devised menstruation in order that women should be able to excrete the remaining impure, potentially putrefacient matter.

But once this 'undigested food' left the female body and emerged into the world, it could be bloody dangerous. By texts alone, menstruation appears to have been a time of danger not only to the woman herself, but the social and natural world around her.

The French version of a text called the Secreta mulierum ("Secrets of Women," probably composed in the 13th century by Dominican theological Albertus Magnus), paints a particularly gruesome portrait of menstrual blood's noxious potential. It could generate within itself "vile, horrible, poisonous creatures," and drive dogs rabid, discolor mirrors, and destroy trees. It could poison a woman from within, whether by menstrual retention – a disease with potentially fatal effects – or by bestowing upon her the ability to inflict harm on children by a mere glance, like a kind of puerperal Medusa.

Yet menstrual blood was not simply poison; it was also necessary for conception. It was called the "flower" of a woman, because in order to be able to bear fruit, women must first flower, like trees. (A poetic metaphor only made possible by the grace that her blood had not been employed to destroy said trees, one imagines.)

Menstrual blood was ascribed the power to become the food for a new life within the womb once conception had occurred, and, once the baby was born, that menstrual blood would be transformed and purified into mother's milk. Many materia medica in medieval herbals and compilation texts, like mugwort and agnus castus in the De proprietatibus rerum of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, seem to have been included specifically because of their potency in producing or regulating menses. If menstruation could destroy, but also nourish, it paid to be able to reign in such a force.

Whether menstrual blood itself or the menstruation process more broadly was presented as a generative or a corruptive force depended much on social, geographical, and temporal context, and medieval and feminist historians are still teasing out these links and relationships. What already seems clear, though, is that even if a woman (or those around her) may not be able to have the white-linen "happy period," medical and philosophical literature at least suggested she would have a metaphysically and physiologically significant one.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She currently studies French, and writes (and copy edits) for the McGill Tribune as well as freelance projects. You can find out more at her About.me page.

October 29, 2011

The woman who almost married Mozart

by Stephanie Cowell (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Mozart almost didn't marry his lovely wife; he almost married her older sister. And if he had married the sister, I believe we'd be missing a great deal of his music today.

When Mozart was twenty-one and unemployed, he was invited to the home of a violinist Fridolin Weber who had four musical daughters, ages fourteen through nineteen. Aloysia was sixteen: she was gifted with a gorgeous voice and quite ravishing. The other three Weber sisters could not come close to her and she knew it.

Mozart was so much in love that he wanted to turn over his own struggling career to promote her singing. (Again, think what music we may have lost!) But there were several obstacles in his path. Her mother was a bit crazy; she thought Mozart would never make a penny and wanted her beautiful daughter to marry a wealthy man. His father was controlling; he didn't want his son to marry anyone but to send all his money home (if Mozart ever made any).

Mozart had to travel in search of earnings, and when he finally found his love again in Vienna, she had forgotten him and was now pregnant by a tall and handsome actor. Mozart was not very tall and not very handsome. When his heart healed a little, he found himself as a boarder in the house of the three remaining Weber sisters. He could have married any of then, but that is a complicated story, so complicated that I wrote a novel about it called Marrying Mozart. He settled on the third sister and had a happy life. He also began to make a good deal of money now and then.

Mozart died at the age of thirty-five and his wife spent the remaining fifty years of her life preserving and sharing her husband's music. By the time Aloysia was quite old, Mozart's name was famous throughout Europe. One of his admirers came to visit the aging prima donna in Salzburg and Aloysia swore to them that Mozart had never ceased to love her. "But why did you refuse him so many years ago?" the admirer asked bewildered and she replied that at that time she was not capable of appreciating his talent and character…" Hmm.

So he didn't get the first girl he loved but he got the right one for him and the right one to save his work for posterity. And if it were not for the music Mozart wrote for Aloysia Weber Lange, history would scare remember her name.

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet and Marrying Mozart. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

October 28, 2011

"We're Still Here!": Slang of the Roaring Twenties

By Joseph Wallace

[image error]When you're writing a historical novel, there's one simple but crucial rule: Make sure the language rings true. Don't , and your readers will be fleeing for the exits, laughing at you as they go.

Early on in researching my 1920s-set novel, Diamond Ruby, I learned that the slang of the era was extremely rich and risqué. People said, "Cash or check?" for "Do I kiss you now or later?" and "Bank's closed" when the answer was a categorical no. A convertible car was a breezer, and a struggle buggy was a car with a back seat, where you…struggled.

Unsurprisingly, in the age of Prohibition, slang words for being drunk were everywhere. You weren't merely tipsy, you were spifflicated, canned, corked, tanked, zozzled, owled, ossified, or fried to the hat.

So the source material was abundant (you can see more expressions here). The problem was using it. Every time I tried, it came across as stilted, silly, fake. As if each use carried invisible quotation marks.

I finally figured out why: Because 1920s slang did come with invisible quotation marks. It wasn't an organic language. It was an invention, created by people whose goal was to forget the past and remake themselves.

The Roaring Twenties was, at heart, a child of the 1910s. All its wildness, the outlandish flapper fashions and headline-grabbing gangster capers and days-long parties were a reaction to two cataclysms of the previous decade: the long, brutal slog of World War I and the great influenza epidemic of 1918.

Those who survived both knew how lucky they'd been – and how fragile life was. Slang was just one small but crucial part of the frenetic seize-the-day spirit that followed.

This insight – that all this wonderful slang was created as a way of saying, "We're still here!" – gave me the key to writing Diamond Ruby in the truest voice I could. In an essential way, it even allowed me to understand the madcap, tragicomic spirit of the time.

About the author: Joe Wallace has been fascinated by the Roaring Twenties since he first decided he wanted to go there and meet James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. He got to explore that world when he researched and wrote his first novel, Diamond Ruby, which is set in a 1920s New York City teeming with gangsters, rum-runners, and other colorful characters. He is currently at work on a Ruby sequel and an apocalyptic thriller definitely not set in that era.

October 27, 2011

A Queen's Anger

In the summer of 1474 (only a few months after the acclamation ceremony I described in my earlier post), King Fernando met with miserable failure on the battlefield. Upon returning to the court, according to the chronicler Juan de Flores, his wife, Queen Isabel, delivered a scathing harangue: "Using the courageous words of a man rather than those of a fearful woman," she upbraided Fernando. She said that as news reached her of the outcome she "had sat in the palace, with an angry heart, gritted teeth and clenched fists." She berated his temerity and weakness.*

Despite the fact that there are at least five contemporary chronicles of the monarchs' reign, this account of the queen's anger only appears in the one by Juan de Flores. Only one other comments on Isabel's emotional state, saying simply that she was saddened by the loss.

We should ask ourselves, then, what image of the queen does Flores' account create? At first blush we might think that he is criticizing her. What right did she have to speak to her husband like that? Conduct manuals of the day cautioned wives—even powerful ones—to be silent, circumspect, and obedient. Curiously, Flores may thwart this dilemma by endowing her with manly attributes. And he doesn't limit himself to descriptions of Isabel. In fact, this assertive Isabel is consistent with his portrait of another forthright personality of Isabel's day, Beatriz de Bobadilla. Beatriz, due to her husband's illness, had periodically administered the city of Segovia. According to Flores, she performed the necessary tasks "like a very discrete man and woman" and with a "shrewdness more intense than women customarily possess." Like Isabel, Beatriz conducts herself in a masculine fashion.

Flores' contemporaries would have seen in his portrayals of Isabel and Beatriz familiar images of what they called a mujer varonil or manly woman. It was also how a fifteenth-century Spanish biography described the cross-dressing warrior Joan of Arc. This gender-bending category praised women not for feminine virtue, but for the transcendence of their womanly nature (perceived as weak) and the assumption of male qualities. Thus, Isabel's anger is not a liability, but rather an indication of her strength.

* All translations are my own taken from Flores' Crónica incompleta de los Reyes Católicos.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in Europe between 1400 and 1700 with an emphasis on Spain, queens, and convents.