Holly Tucker's Blog, page 88

December 21, 2011

An Epidemic Caused by Alcohol: Beaune, 1746

By Lisa Smith (W&M Regular Contributor)

After the Battle of Rocoux (11 October, 1746), several Dutch prisoners of war were held in Beaune (Burgundy). Townsmen were recruited as guards, with local lawyers and physicians – men of responsibility – as captains. Physician Vivant-Augustin Ganiare (1698-1781) expressed concerns about the prisoners being a potential source of contagion in November. They had dysentery and seemed to be the source of a local worm outbreak.

After the Battle of Rocoux (11 October, 1746), several Dutch prisoners of war were held in Beaune (Burgundy). Townsmen were recruited as guards, with local lawyers and physicians – men of responsibility – as captains. Physician Vivant-Augustin Ganiare (1698-1781) expressed concerns about the prisoners being a potential source of contagion in November. They had dysentery and seemed to be the source of a local worm outbreak.

Over Christmas, several young captains provided their men with wine and tobacco to help morale, which led first to "bacchanals" and then to the worst-ever hangover: a flu-like epidemic for the whole town. Men, especially those who had been on recent guard duty, were the main victims. Women and children in turn caught it from male family members.

An unnamed 'Monsieur' aged 37 was typical. He spent two nights on watch with his friends, where they drank and danced with the prisoners. Off duty, he ran about the streets in "excessive joy". The alcohol's effects were worsened by sudden temperature changes between the heat of revelry and the cold outside.

Fraternization was bad enough, but the underlying problem was failed leadership. Ganiare was unsurprised that nearly all of Monsieur Navetier's men had died since Navetier had been particularly generous. The captains should have known better than to give their men booze. The entire town now suffered from their foolishness!

Ganiare maintained detailed notes of interesting cases and monthly summaries of general health trends, crops and weather. As a man of science, Ganiare wanted to identify patterns in epidemics and weather; as a religious man, he hoped to see the hand of God in nature. By uncovering nature's secrets, he hoped to control disease outbreaks.

This time Ganiare had no need to search further for nature's secrets. His conclusion? The epidemic, caused by fraternization and carousing, had been entirely preventable.

A cautionary tale for the festive season…

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

Image: Hospital (Hôtel-Dieu), Beaune: courtyard. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Leeches and Lancets: A Sensible Mucus

By Sam McBride (Vanderbilt University)

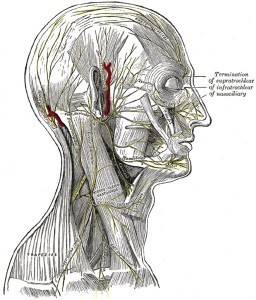

While researching a paper on madness, I came across this statement on the brain in the 1792 essay A Review on the Subject of Canine Madness, "It is allowed by all that the brain is the only sensible part of the body, and that it is diffused over every moving fibre, in form of a sensible mucus" (Bourke, 6). This being a completely new theory to me, I attempted to trace it back to its source. Bourke attributed the theory to the surgeon Thomas Kirkland, who wrote in 1774, "the inside of a nerve is not a mass of fibres arising from the white part of the brain, but that it is a small portion of the white part of the brain itself, which is not fibrous, but the substance described." (8). The substance described is a sensible mucus, which Kirkland supports by referencing the Swiss anatomist Albrecht von Haller, who, "when he saw it (the brain) without knowing what it was, it appeared to be 'a mucus' (7).

At this point the trail goes dead. Kirkland gives no indication as to where Haller wrote this, and I was unable to find that quote. As far as I can tell, no other references exist to "a sensible mucus". Perhaps Kirkland was trying to create a physical model of Thomas Willis' "animal spirits". We may never know. It's a theory lost to the dustbins of history, and a reminder that universal acceptance is a myth: no matter how prevalent the orthodoxy might be, there will always be dissenters like Kirkland and Bourke.

Works Cited

Bourke, Michael. A review of the subject of canine madness.

Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1792.

Kirkland, Thomas. A Treatise on Child-Bed Fevers, And On The Methods Of Preventing Them, Being a Supplement to the Books Lately Written on the Subject. London: 1774. 8-9. eBook.

December 20, 2011

The Cloister and Accounts Payable

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt

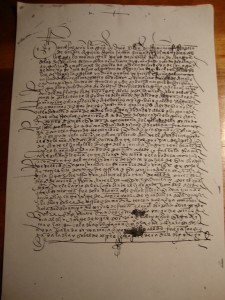

When I began doing research on early modern convents, one of my favorite finds in the archives was their account books. At first glance they were impenetrable. Only by spending hours paging through through them carefully did their internal logic reveal itself. There is no double-entry bookkeeping, for example. Expenditures are grouped together and then all sources of income are listed collectively. Once I got acclimated to their format, I realized that they were a treasure trove of information about convent life. Take, for example, the books from the convents of Santa Isabel and Santa María de las Huelgas, both located in the city of Valladolid.

photocopy of a page from the archives of Santa Isabel de Valladolid

At the turn of the seventeenth century, the pages of these account books reveal that the nuns consumed meat, fish, wine, oil, and eggs with some regularity. "As was customary" the nuns of Santa Isabel were allowed to enjoy pastries at Sunday dinner. The nuns employed a variety of personnel to help them manage their properties and estates. Since normally women were prohibited from performing the sacraments they also had to hire and pay priests to perform these tasks [see my last post for interesting cases of when women could perform sacraments]. The nuns also had to maintain the liturgical life of the community. They purchased items like wax and missals. Music was central to their devotional life; the accounts record expenditures for bellows for an organ and strings for a harp. Just like their secular counterparts, the nuns were constantly having to do maintenance on their physical plant: repairing a sewer; paying someone to pave a walkway, rebuilding chimneys, walls, and doors. They might also pay large sums of money to local artisans for more elaborate projects like repairs to an upper cloister or the commissioning of an altarpiece.

Yet perhaps the most intriguing insight that comes from the pages of these books is that convent officers were responsible for all of this activity and the bookkeeping and responsibilities that it generated. The books include the signatures of nuns who handled money and acted as stewards and accountants. Twice yearly, the abbess added her signature to the records. Despite the fact that their male contemporaries did not think them capable of rational administration, the evidence yielded by these weathered books makes clear that these women managed their resources efficiently and carefully.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She is currently at work on a project exploring the material culture of convents in early modern Europe.

December 17, 2011

Beginning in Wonder

By Christopher Long (W&M Regular Contributor)

Leaf, Grass, Frost via Flickr by cplong11

I endeavor to practice philosophy, and philosophy begins in wonder. Aristotle puts it well toward the beginning of the Metaphysics:

For it is through wondering that human-beings both now and at first began to philosophize, wondering first about the strange things close at hand, and then little by little in this way devotedly exerting themselves and coming to impasses about greater things, such as about the attributes of the moon and things pertaining to the sun and the stars and the coming-into-being of the whole. (Aristotle, Metaphysics, I.2, 982b11-17, translation mine from Aristotle on the Nature of Truth, 4-5)

Philosophy involves the attempt to move from the surface to the depth of things, and Aristotle is right to think of it as requiring devoted exertion. But philosophy also brings us hard up against our finitude, an experience we too often seek to evade by taking refuge in certainties posited dogmatically. But the philosophical activity is impoverished by dogmatism, for philosophy is at heart a collaborative endeavor to respond to the nature of things in ways that return us to our relationships with one another and the world enriched.

Part of the difficulty of it is learning how to respond to the experience of finitude in ways that open rather than close possibilities of relation. My daughters help me with that, as my then 6 year old (who I call "ArtGirl" on the web) reminded me one evening before bed. I love how those quiet moments at the end of the day open the space for philosophy. Listen to what she said:

ArtGirl Wonders about the Beginning of Things (46 second audio file)

The wonder of it for me is how her voice articulates our shared finitude without anxiety or worry; and how she invites us to join her in the experience.

Christopher Long is Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies at the College of the Liberal Arts at Penn State and Associate Professor of Philosophy and Classics. He is the author of two books on Aristotle, The Ethics of Ontology (SUNY 2004) and Aristotle on the Nature of Truth (Cambridge 2011). You can follow him on his blog, the Long Road and on Twitter @cplong.

December 16, 2011

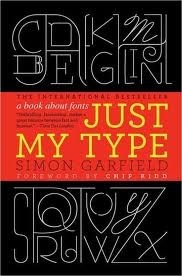

Steve Jobs and Typography

By Simon Garfield

On June 12 2005, a fifty-year-old man stood up in front of a crowd of students at Stanford University and spoke of his campus days at a 'lesser institution' – Reed College in Portland, Oregon. 'Throughout the campus,' he remembered, 'every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully hand calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn't have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can't capture, and I found it fascinating.'

At the time, the student, who would later drop out of college, believed that nothing he had learned would find a practical application in his life. But things changed. Ten years after his college experience, that man, by the name of Steve Jobs, designed his first Macintosh computer, a machine that came with something unprecedented – a wide choice of fonts. As well as including familiar types such as Times New Roman and Helvetica, Jobs introduced several new designs, and had evidently taken some care in their appearance and naming. They were named after cities he loved, such as Chicago and Toronto. He wanted each of them to be as distinct and beautiful as the calligraphy he had encountered a decade earlier, and at least two of the fonts – Venice and Los Angeles – had a handwritten look to them.

It was the beginning of something – a seismic shift in our everyday relationship with letters and with type. An innovation that, within another decade or so, would place the word 'font' – previously a piece of technical language limited to the design and printing trade – in the vocabulary of every computer user.

You can't easily find Jobs's original typefaces these days, which may be just as well: they are coarsely pixelated and cumbersome to manipulate. But the ability to change fonts at all seemed like technology from another planet. Before the Macintosh of 1984, primitive computers offered up one dull typeface, and good luck trying to italicize it. But now there was a choice of alphabets that did their best to re-create something we were used to from the real world.

Chief among them was Chicago, which Apple used for all its menus and dialogs on screen, right through to the early iPods. But you could also opt for old black letters that resembled the work of Chaucerian scribes, London, clean Swiss letters that reflected corporate modernism ', or tall and airy letters that could have graced the menus of ocean liners New York. There was even San Francisco, a font that looked as if it had been torn from newspapers – useful for tedious school projects and ransom notes. IBM and Microsoft would soon do their best to follow Apple's lead, while domestic printers (a novel concept at the time) began to be marketed not only on their speed but for the variety of their fonts. These days the concept of 'desktop publishing' conjures up a world of dodgy party invitations and soggy community magazines, but it marked a glorious freedom from the tyranny of professional typesetters and the frustrations of rubbing a sheet of Letraset. A personal change of typeface really said something: a creative move towards expressiveness, a liberating playfulness with words.

And today we can imagine no simpler everyday artistic freedom than that pull-down font menu. Here is the spill of history, the echo of Johannes Gutenberg with every key tap. Here are names we recognize: Helvetica, Times New Roman, Palatino and Gill Sans. Here are the names from folios and flaking manuscripts: Bembo, Baskerville and Caslon. Here are possibilities for flair: Bodoni, Didot and Book Antiqua. And here are the risks of ridicule:

Brush Script, Herculanum and Braggadocio. Twenty years ago we hardly knew them, but now we all have favourites.

Reprinted from Just My Type by Simon Garfield by arrangement with Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., Copyright © 2011 by Simon Garfield.

Cowboys and Indians: North African Style

By Pamela Toler, W & M Contributor

Unlikely though it seems, I've spent a lot of time thinking about the French Foreign Legion over the last week.

I bet most of you have a few stock images of the Foreign Legion in your heads: men fleeing from their past into the desert and anonymity, absinthe, burning sands and blazing sun, those funny little billed caps with the flap down the back. (Extra points for anyone who knows what those caps are called.)

For most of us, those images come from trashy novels and B-movies that are kissing cousins to the American western at its least thoughtful. Both genres are heavy on the last minute arrival of the cavalry*, noble (or savage) armed horsemen as opponents, last chance saloons, and strong, silent heroes. Not to mention burning sands and blazing sun (see above).

And just like in the American western, the dangerous armed horseman on the ridge has his own version of the story.

Abd al-Qadir by Rudolf Ernst

If the French hadn't invaded Algeria in 1830**, Algerian emir Abd al-Qadir would probably have been content to follow his grandfather and father as the spiritual leader of the Qadiriyah Sufi order. In the fall of 1832, when the French began to expand their control into the Algerian interior, the Arab tribes of Oran elected al-Qadir as both the head of the Qadiriyah order and as their military leader.

Al-Qadir led Arab resistance against French expansion in North Africa from 1832 to 1847. He was so successful that at one point two-thirds of Algeria recognized him as its ruler. The French signed treaties with al-Qadir and broke them. (Similarities to the American western, anyone?) After a crushing defeat in 1843, he was hunted across North Africa as an outlaw.

Abd al-Qadir surrendered at the end of 1847 and was imprisoned in France until 1853. Following his release, he settled in Damascus, where he entered the stage of world history one last time. In 1860, the Muslims of Damascus rose and began slaughtering the city's Christians. When the Turkish authorities did nothing to stop the massacre, Abd al-Qadir and 300 followers rescued over 12,0000 Christians from the massacre. Once hunted by the French as a dangerous outlaw, Abd al-Qadir received the Legion of Honor from Napoleon III for his efforts.

Heroism is in the eye of the beholder.

*In fact, the Foreign Legion was an infantry unit. Just saying.

** Over what the French press called the Incident of the Flyswatter. I couldn't make this stuff up.

This post previously appeared in History on the Margins.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

December 15, 2011

Even Royal Molars Decay

By Lauren Renaud (Vanderbilt University)

A gleaming white smile represents youth and beauty. Today, pearly whites are achievable for many through regular visits to the dentist. However, in eighteenth century France, the dental field was just seceding from quackery. A new professional, the dentiste, was replacing local blacksmiths who remedied toothaches through extraction with bulky metal tools. Without dental hygienists and the knowledge that sugar leads to cavities, even French royalty couldn't escape the blight of tooth decay.

The most visible of royal dental disasters afflicted French King Louis XIV. Ironically, the Sun King, known for visual extravagance, was toothless by age forty. Throughout the 1680's Louis XIV experienced tooth decay probably catalyzed by his taste for candied fruits and sweetmeats. Although the decay necessitated numerous extractions, the royal surgeon refused to remove the king's rotten molars because dentistry was considered a "mechanical" field. Instead, he summoned arracheurs de dents (itinerant tooth pullers) to perform the tasks.

The procedures progressed regularly until 1685, when one extraction merited mention in the Journal de santé [The Health Journal]. In this case, the extractor accidentally removed a large portion of the king's jaw and palate in addition to the rotten tooth. The Sun King was left with a large hole in his mouth. After this incident, whenever the King took a drink, the beverage spouted out his nose in a fountain-like manner. A surgeon later cauterized the hole ending the embarrassment and the festering infection.

After experiencing the woes of tooth decay, Louis XIV appointed a specialist dental surgeon in 1712. Years later, Louis XV also grew concerned about tooth loss. He assigned an even greater importance to the dentistry by granting his personal dentiste, Jean-Francois Capperon, letters of ennoblement. This meant that, by royal decree, the dentiste was now a member of the nobility.

Tooth decay not only afflicted French commoners but also members of high society. For French royalty, who assigned utmost importance to their appearances, the services of the dentiste became necessary for preserving their smiles and the marriage potential of their children.

December 14, 2011

A Tree of Knowledge Branches Out

Back in 2006, someone told me about a new book called Mapping Paradise , an illustrated history of the cartography of Eden by Alessandro Scafi. Too broke to purchase it, I took notes discreetly in a Manhattan Barnes and Noble. The notes looked like an extended haiku by T.S. Eliot; but one item from the book took me on a long journey. A 1946 photograph from the Times of London of a small dead tree in southern Iraq, which was purported to be the Bible's Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The caption suggested creating an international peace park on the spot. That's weird, I thought, how could the Tree still be alive?

But the story got weirder. In 2007, an MFA student at Columbia, I accessed the Times online archive. It turned out that picture sparked a mini-drama in the Letters page. Several British military personnel sent in competing descriptions of a decades-earlier incident: On New Year's Eve, 1919, soldiers stationed in Qurna, Iraq, had climbed—and broken—this very Tree of Knowledge, enraging Iraqis and forcing the Brits to repair it with concrete. Soon afterward, rebellion broke out across Iraq. I had to know more. What were the soldiers thinking? Who was enraged and why? And what did the Garden of Eden have to do with the revolution?

One of the letter-writers claimed he'd gathered a file of outraged telegrams at the time. But I could find nothing in the British Library or Archives online. My professor, visiting London, offered to search the actual Library for me—still nothing. So I tried to accumulate enough background about the place, people, and timeline to able to tell at least a provisional story. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many travelers had passed through Qurna, at the junction of the Tigris and Euphrates, and taken note the Tree. I stitched together numerous tiny references into something that resembled a whole. My proudest discovery was actually the answer to the Times photograph.

During Iraq's one period of stable government between two bloody revolutions in the 1950s, the British-backed king went on a publicity tour of major European capitals, touting the country's resources, achievements, and potential in an (ironically British-printed) glossy propaganda pamphlet. And one of those points of pride was Qurna's Tree of Knowledge. This image shows a healthy Tree flourishing after being broken, bombed, and belittled. Before I returned the pamphlet—too soon, since the library somehow classified it as a periodical—I made sure to scan the photo.

But to actually understand what had gone on in 1919, I had to search closer to the present. Bruce Feiler's Walking the Bible described the post-Saddam park built in Qurna to protect the Tree of Knowledge. One of the few travel companies that still took tourists to Iraq in the 1990s had photographs of the Tree on its website. (Or rather, Trees. By now there were several.) Reuters stories after the 2003 invasion talked of busloads of Iraqis coming to the Tree to pray.

But why? It couldn't really be the tree from the Bible, could it? And weren't Iraqis Muslim anyway? An online search for "trees" "Iraq" "shrine" and "sacred" eventually led me to an academic scholar of Middle Eastern folklore who, as it turned out, lived in my then-neighborhood, Astoria, Queens. We met for coffee. Oh sure, he said, this sounds like traditional Middle Eastern tree-worship. It predates the Bible, and monotheism in general, which is remarkable in a region filled with monotheistic fundamentalists.

I needed firsthand description. My brother, a journalist, put me in touch with a Kurdish Iraqi colleague; we met in the lobby of Columbia's journalism school. Sadly, he didn't remember Qurna's Tree. But when I asked him about sacred trees in general, he lit up. In his hometown, hundreds of miles from Qurna, people visited sacred trees all the time, to request favors. The trees had to be treated with respect. You could not touch them, take a branch, or peel their bark, without risking the wrath of the holy man associated with them—or your mother. Finally, I understood why there were enough outraged telegrams to fill a file folder in 1919. And every time one sacred tree dies, another is planted in the same spot, which explained why there was now a small grove in Qurna. Three years later, I could finally tell the whole story.

A small illustrated version of it (in the literary journal Triple Canopy) became a twenty-page essay, and then informed three chapters of my book, Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden. This week, six years after I first discovered it, the Middle Eastern scholar told me he'd been teaching my story about the Tree in his folklore class. I guess it really is the Tree of Knowledge!

Brook Wilensky-Lanford is the author of Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, which was a New York Times Editors' Choice in August. Her reviews and essays have appeared in Salon, Lapham's Quarterly, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Boston Globe. A graduate of Columbia University's nonfiction writing MFA program, she lives in New Jersey.

December 12, 2011

Accentuate the Vitreous, Eliminate the Resinous

By Marc Merlin (Atlanta Science Tavern)

"Positive" and "negative." These two words associated with everything electrical seem so natural to us that it is surprising to recall that at some point in time they had to have been invented.

Charles François de Cisternay du Fay

Their invention began with Charles François de Cisternay du Fay, a French chemist and superintendent of the Jardin du Roi, who reported in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in December 1733 the discovery of a "universal and remarkable" principle that "casts a new Light on the Subject of Electricity," namely "… that there are two distinct Electricities, very different from one another; one I call vitreous Electricity; the other resinous Electricity."

Du Fay assigned the name vitreous to the type of electricity exhibited by materials like glass and resinous to the type exhibited by those like copal (tree resin) according to patterns of electrical attraction and repulsion that he observed between such substances.

Not much more than a dozen years passed before William Watson and Benjamin Franklin independently recognized that du Fay's "electricities" could be explained as a surplus or a deficiency of what we now call electrical charge, and so came about the names we use, positive for du Fay's vitreous electricity and negative for his resinous one.

More than merely an advance in the electrical studies of the age, du Fay's discovery represents a profound first scientific realization, one which foreshadows the through-the-looking-glass world of quantum physics two centuries later. And that is that the objects of nature possess latent properties for which entries are not to be found in the lexicon of sensory experience; and that to have dominion over such things, like Adam over the animals created in Genesis, we are obliged to give them names.

Marc Merlin had aspired once to be a physicist, has worked mostly as a computer programmer and is now happily ensconced as the organizer of the Atlanta Science Tavern. A longer discussion of the theme of this post can be found in his essay, .

What are your writing goals this week?

The honest title for this post? Ok, "Why sometimes it is better just to do nothing."

I'm a little late posting this because I'm on Pacific Standard Time right now, instead of Central Standard. I also wanted to make sure Beth Dunn's fabulous post on Dickens got plenty of eyes.

As I write, I'm sitting in front of a lovely fireplace having a glass of wine–and unwinding from a hard day of, ok I'll say it, doing nothing.

Each week in early December, I join my mother and sister for a short trip away somewhere. We spend time hanging out with each other, preferably near water.

But most of the time we do little more than sit quietly, together, and read. (Mom and Heather are reading as we speak. I'll be joining them shortly after I pour another glass of red.) And we also always find a way to sneak in a massage and a facial. That's what it is. Total girl time.

Last week, I rushed around trying to finish up the semester and put to rest all of the grading I needed to do. I also began the week by trying to do twice as much research- and writing-wise than I normally would do to make up for the 4 days that I was going to miss.

A few days in, I cut myself a break. The stress of trying to get more done meant that I got less done. Once I stopped being dumb and got back to a normal schedule, I was able to get the chapter descriptions in place. And I'm liking how they read. A lot.

So this week. I have no goals. No guilt. And when I return to Central Standard Time in a few days, I'll be re-energized and ready to get back to work.

What about everyone else? Did you make your goals this week? What's on tap for this one? And most importantly, what do you do to take care of your writerly self?