Holly Tucker's Blog, page 71

February 2, 2013

Lenin’s Lamps

Arkady Shaikhet’s “Lenin’s Lamp” (1925)

In Arkady Shaikhet’s photograph “Lenin’s Lamp” (1925) two peasants examine a light bulb hanging from a cord that appears to be strung through the portrait of Mikhail Frunze, Bolshevik and son of a peasant. Electricity seems to be directed from Frunze’s mind and into the hands of the unenlightened peasant, whose traditional haircut and clothing contrast sharply with Frunze’s and point to the intended modernizing influence of the electrification campaign. In the early Soviet period, showing the light-bulb–nicknamed “Lenin’s lamp”–to the peasants became a demonstration of technology that Lenin claimed would “show the population, especially the peasants, that we have [. . .] broad plans which aren’t taken from fantasies, but supported by technology grounded in science.” The image showed up on posters, lacquered boxes, and even in a children’s cartoon. The light-bulb may seem a strange choice of evidence to prove that communism is not “fantasy,” but as seen in Shaikhet’s often-reproduced photograph, the light-bulb is endowed in Soviet propaganda with the significance of a religious artifact that merely needs to be touched or seen in order to work wonders. The peasant is presented in Bolshevik propaganda about electrification as a scapegoat for everything regressive in post-revolutionary Russia; Lenin writes: “[Electrification] will enable us to fully and decisively defeat that backwardness, that fragmentation, disintegration, the darkness of the countryside, that is to this point the main cause of all stagnation, all backwardness, all oppression.” Lenin presents electricity as a high-tech adhesive that could mend the “fragmentation, disintegration” of the countryside and meld the dark fragments into one cohesive brightly-lit whole, lighting up the darkness both literal and figurative. The primitive, flickering light of the peasant home and work-place would be replaced by Lenin’s lamps: “Cheap light energy from mighty regional electrical stations spreads around the whole country, goes right up to village huts with their wood-splinter torches and other home-grown means of illumination, overthrowing the coarse backwardness of village life.”

[image error]

“Electrification and Counterrevolution” (1921)

Repeatedly, Bolshevik propaganda argued that electricity would defeat capitalism, religion, hierarchy and exploitation. In the 1923 poster “Electrification and Counter-revolution” an enormous hand holds up one of Lenin’s lamps, and a group of stereotypical counterrevolutionaries representing the evils of the class system try to extinguish its light. To the left of the light bulb a fat capitalist crouches on his hands and knees so that a White general and an Orthodox priest can climb up on his back with a fire hose; to the right a fashionable gentleman fetches a bucket of water; and in the center a foreign diplomat attempts to blow out the light bulb with a small bellows. The tiny figures each wear identifying markers of the exploiting class—clerical garb, gold epaullettes, a top hat, a gentleman’s straw boater, and a monocle. They also wear technological ignorance and backwardness on their well-tailored sleeves. Under the electric light of the proletariat they become comic buffoons, motivated by fear and greed and fighting the progress of technology with the ineffectual weapons of a more primitive age. Embodied in the electrification campaign is the promise that with technological superiority comes moral purity. The proletarian hand, like the right hand of God, gives humanity the light of truth, guiding followers to the bright future and illuminating the technologically ignorant exploiters of humankind, so that they can be seen as cartoon figures, easily defeated by the mighty–electrified–Soviet hand.

[image error]

Cover of “We Build” (1929)

As we can see in the cover of the November 7, 1929 issue of We Build, a Soviet journal dedicated to construction photography, after his death in 1924, Lenin’s image became inextricably linked to the lamps that carried his name and that fought the darkness of ignorance. Here Lenin’s head is enclosed in an enormous light bulb, a fusion of human and technology that gives new meaning to the term “Lenin’s lamp.“ Below the disembodied Lenin’s lamp, we see one of the massive hydroelectric dams envisioned by the electrification campaign and the constructions enabled by their power. A power tower is pictured in the upper right-hand corner. Moving diagonally down the page and separating the picture of the construction site from the picture of the electric tower is a series of letters forming steps that spell out: “XII October is a New Step toward Socialism,” in large font in Russian and in smaller letters in German and English–to show the triumph of Soviet construction over the leading industrialized countries of the world. In this tribute to the twelfth anniversary of the October revolution and the first five-year plan, Lenin’s head becomes a source of light for everything contained in the picture; and, by implication, in the journal issue that follows. The power goes both ways. The lines connecting the base of the light-bulb to the tops of cranes and the roofs of factories also charge up the light-bulb and by implication the memory of Lenin, who “lived, lives, and will live” in memorials like this one that help the Soviet people move up the stairway to socialism. According to the circular logic displayed in the image, each year after the revolution takes another “step toward socialism” through the human energy that accomplishes monumental construction feats, and it also produces energy for revolutionary enlightenment that will push the Soviet people up one more step. The cult of Lenin and technology that is powered by the head in the light bulb is an energy loop of propaganda and construction, each of which feeds energy to the other.

The Bottle and the Gallows

By Joel Harrington (W&M Regular Contributor)

Rare is the human society, past or present, in which drinking alcohol has not served a variety of purposes. Naturally we think of relaxation and celebration, and of course the lubricating role of drink in a multitude of personal relationships: friendship, romance, business, politics, and even at the very end of life (think wakes).

In premodern Europe, drinking served all these functions and more. Beer and wine were ubiquitous, as were distilled spirits from the sixteenth century onward. Given the scarcity of potable water and other non-alcoholic drinks, personal consumption of a gallon a day of beer was not considered excessive. Even the smallest hamlet boasted at least a tavern or two. Not surprisingly, many if not most Europeans went through the day legally drunk by modern standards, providing some relief for the harsh conditions of their lives, but also spawning a growing problem with public drunkenness.

Alcohol also played a pivotal role in law enforcement. Or rather, in the most severe form of law enforcement—public executions. First, there were the condemned prisoners themselves, traditionally known as “the poor sinners.” In most locations, like today, the poor sinners were granted one last feast before the final hour. Some individuals had little appetite for any food, while others gorged themselves on meat and drink until the very last minute. Virtually every condemned soul was offered the executioner’s “special drink,” a high-alcohol concoction typically laced with a sedative. This was in fact a delicate operation, since some fragile women might pass out, while some boisterous young men might become even more aggressive, endangering the executioner and his assistants. The overarching goal was to calm an agitated poor sinner, but still make it possible for him or her to walk to the execution grounds from the prison and face death awake.

During the condemned prisoner’s procession to the gallows, alcohol played still another role—though hardly aiding the executioner in the performance of his duties. Spectators began assembling many hours before public executions, eager to secure good viewing spots. Street vendors selling bottles of beer and wine roamed the crowds, invariably populated to some degree by numerous drunken young men, jostling one another and singing ribald ditties. The poor sinner, public executioner, and other members of the formal death procession thus ran a gauntlet of shouting, spitting, and thrown objects on their way to the place of execution

Once having reached their destination, the executioner than often had to wait through long farewell speeches or sung ballads, often growing visibly more anxious. Drunken and angry spectators, after all, were known to verbally abuse the executioner as if he were a referee at a professional sports event—with the notable difference than any botched performance on his part might trigger a public stoning or other deadly assault on him and his assistants.

Not surprisingly, many professional executioners thus found solace in—what else—a drink. In fact, executioners were largely reputed to be heavy drinkers, even by premodern standards. While understandable, drinking too much before the execution sometimes caused mishaps, such as multiple strokes of the sword at a beheading. Crowds did not react well to botched executions, nor did government superiors, who fired without hesitation an executioner who ruined their public spectacles of justice. That is, if the crowd didn’t get to him first.

It was thus a remarkable anomaly when an executioner had a reputation as a sober man, yet the man I have come to know through the writing of my recent book—Meister Frantz Schmidt of Nuremberg—not only didn’t get drunk, he didn’t drink at all. This decision, as I discovered, was a very clever bit of self-promotion and marketing, but also reflected an exceptionally determined individual with a lifelong agenda.

January 29, 2013

Medicinal Compounds, Efficacious in Every Case

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

Perhaps the most famous cure-all of all time is Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, immortalized in song as “Lily the Pink” (or “The Ballad of Lydia Pinkham”).* Although the original vegetable compound aimed to treat women’s ailments, the song suggests—tongue in cheek–that it might have much wider, rather miraculous applications. The boy with sticky out ears learns how to fly; the man who thought himself Julius Caesar becomes emperor of Rome.

Ridiculous. How, after all, could one drug cure so many ailments? In the modern world, cure-alls just don’t make sense.

But they did at one time. In early modern Europe, cure-all medicines were as likely to be sold by elite physicians as by “quacks” and were often made domestically. These treatments made sense. In a humoral body, with its properties of cold, hot, wet and dry, many seemingly different problems might have the same underlying cause.

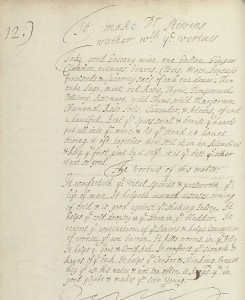

Bridget Hyde’s book, late seventeenth century. Wellcome Library, MS 2990, f. 52v. Image Credit: Wellcome Library.

“Dr Stevens’ Water” was a common remedy in English remedy collections kept by well-to-do families. Authors sometimes provided lists of a treatment’s “virtues”, which usefully explain the underlying rationale. Bridget Hyde, for example, described Dr. Stevens’ Water as good for the vital spirits, inward colds, palsy, dropsy, gout, bladder stones, weak sinews, barrenness, worms, tooth-ache, stomach, and “rayns of ye back”. (Reins of the back refers to a urinary or genital discharge.)

An even more impressive and random list than Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound! What all of these illnesses had in common, however, was that they were caused by cold and wet humours. Looking up each ingredient in herbals and pharmacopoeias reveals that herbs like nutmegs, cloves, mace, aniseeds, lavender and rosemary (for example) had warming and drying properties. Rosemary was ruled by the Sun and Aries; given its warming and comforting properties, it was commonly prescribed for any problems caused by cold humours. Mace, ruled by Venus, was chiefly used for treating problems of the womb.

Sometimes the connections are surprising. “Pertes de sang” (or blood loss) in French collections could refer to general losses of blood, excessive menstruation or uterine bleeding, miscarriage – or diarrhoea. For example, one remedy for fluxes of blood in Mme Lievain’s book (Wellcome Library MS 3258, f. 132) also specified its use in diarrhoea. The main herb, cinquefoil, was commonly used for stomach problems as well as fluxes of all kinds, with a cooling property to sweeten the blood.

Most cure-alls did not try to treat everything, but had a clear rationale and focused on a group of closely-related ailments.

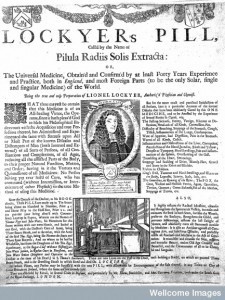

That said, not all cure-alls were created equal — and there were some weird ones out there. Lionel Lockyear, for example, claimed that his pills had the extract of the sun in them. Even better than Lily the Pink, then…

Broadsheet advertising L.Lockyer’s patent medicine. Image Credit: Wellcome Library.

*A rather entertaining song, though it needs an ear worm alert.

Interested in recipes and remedies? This post has been cross-posted at The Recipes Project, a group blog about historical recipes and remedies of all sorts!

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and recently taught a course on natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog. For more on multi-purpose remedies, see Smith’s article, “Imagining Women’s Fertility before Technology”, Journal of Medical Humanities, 31, 1 (2010): 69-79.

January 23, 2013

Tales of the Blockade Runners

Nina (left) and Lucy Ann, two dolls that may have been used to smuggle quinine during the Civil War.

by Karen Abbott

In April 1861, as soon as President Lincoln declared a blockade of 3,500 miles of coastline in an attempt to cut off the Confederacy’s overseas trade, savvy Southerners found ways to evade it. England, which remained neutral, allowed agents to buy at will, and a blockade-running business flourished abroad. Low, sleek ships like the Bermuda set sail from Liverpool and broke the cordon, slipping into the wharf at Savannah with a million-dollar cargo: cannon, rifles, cartridges, gunpowder, shoes, blankets, morphine, and ever-valuable quinine, which was used to treat malaria. Domestically, two Philadelphia-based, politically connected chemical manufacturing companies, Powers Weightman and Rosengarten Sons, supplied quinine to Union troops, but employees who valued profit over patriotism or sympathized with the South were always eager to make a deal.

Smugglers and spies swarmed the towns along the Potomac River, a burgeoning network that linked rebels in Virginia and Maryland, the latter a tobacco-producing border state with a significant slave population. Despite constant patrolling by the federal navy, hundreds of rebels crossed the river at Pope’s Creek, where the water stretched fewer than two miles wide. A farmer named Thomas A. Jones—who would aid John Wilkes Booth’s escape in 1865—lived on the Maryland side. He had calculated a sliver of time, just before dusk, when the sun grazed the high bluffs above Pope’s Creek and threw a shadow across the river, enabling small rowboats to land and hide without detection.

Jones cooperated closely with Benjamin Grimes, a fellow farmer on the Virginia side, and together they orchestrated at least two crossings a night—some of them conducted by nine-year-old Robert Fitzgerald, the father of the future writer. Boats set sail from Grimes’s property, deposited packages in the fork of a dead tree on Jones’s shore, and collected packages from the same spot if, for some reason, Jones himself was not standing on the beach waiting with them in hand. When it wasn’t safe for a boat to cross from Virginia, Miss Mary Watson, the 24-year-old daughter of a Confederate major, sent a signal by draping a black shawl from the window of her home.

Women proved to be some of the most dependable and daring blockade runners. One managed to conceal inside her hoop skirt a roll of army cloth, several pairs of cavalry boots, a roll of crimson flannel, packages of gilt braid and sewing silk, cans of preserved meats, and a bag of coffee—the contraband tally for a single crossing. Another found a functioning pistol on a battlefield, took it apart, and endeavored to smuggle the pieces to a rebel solider. She hid the two halves of the wooden butt in between soft ginger cookies, pushed the barrel into a loaf of bread, and buried the screws in a jar of potted shrimp, also filched from a Union officer. Large quantities of quinine passed through, sometimes packed in sacks of oiled silk and tucked inside the hollowed, papier-mâché heads of children’s dolls.

As the war progressed the blockade had its intended effect, interrupting business and choking the Confederacy of supplies. No one could receive checks or access funds held in northern banks. Coffee was a luxury good. Atlanta jewelers set coffee beans instead of diamonds in breast pins, and newspapers printed suggestions for ersatz brews: take the common garden beet, wash it clean, dice into small pieces, roast in the oven and grind, boil with a gallon of water, settle with an egg. Newspapers dealt with shortages by printing on wallpaper, wrapping paper, and the backs of business forms. Textbooks became an entrepreneurial enterprise and adopted a decidedly local flavor. One arithmetic book posed the problem: “If one Confederate soldier kills 90 Yankees, how many Yankees can 10 Confederate soldiers kill?”

Ultimately it was the occupation of the Confederate ports, rather than the vigilant watch kept by federal cruisers, that stopped the blockade runners. Union capture of Mobile Bay in August 1864 closed what was virtually the last port on the Gulf. Charleston and Wilmington, the South’s last ports on the Atlantic Coast, fell in early 1865, and the Confederacy was finally starved into submission.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her next book, a true story of four female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins in 2014.

Sources:

Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1988; author interview with Catherine Wright, curator of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, VA.

.

January 22, 2013

The Broken Mirror

by Anthony Martin (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

“I don’t do humans!” This declarative statement, uttered by actor Jim Carrey in the movie Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994), is also my usual response to anyone who asks how much of my research in ichnology (the study of plant and animal traces) deals with humans. Sure enough, nearly all of my studies are of the tracks, burrows, trails, nests, toothmarks, feces, and other sign left by plants and non-human animals via their behaviors. Moreover, as a paleontologist, I also compare these modern traces to fossilized traces in the geologic record. Through such methods, I am applying a basic principle of geology, uniformitarianism, which has been followed by geologists and paleontologists for the past 200 years, and is often defined by the pithy phrase, “the present is the key to the past.” More elaborately, its tenets are that the modern processes we observe today – such as flowing water, weathering, erosion, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, natural selection, and ecological change – also operated during the pre-human past.

Notice I said “pre-human past,” revealing both my biological and chronological biases. This perspective is also shared by most of my colleagues, as only a few ichnologists study behaviors of modern humans and the traces of these behaviors. This is more the realm of anthropologists, psychologists, historians, or forensic scientists (the last of these all too often depicted as glamorous detectives in lurid TV shows). In reality, the majority of ichnologists ignore humans, and more often use their observations of modern non-human traces as guides for traveling back in time to interpret the products of behavior from earth history. This is how we can interpret when (and why) a trilobite stopped and changed its direction while burrowing along a Paleozoic seafloor more than 400 million years ago. This is how we figure out what a dinosaur was eating on a given day during the Mesozoic Era, and that dung beetles were living with those dinosaurs, making use of the digested part of that dinosaur’s meal. This is how we identify the size and species of fish that swam along a lake bottom more than 50 million years ago, despite it having left only marks from its fins and mouth. Given nearly ten million species of modern life-forms and their behaviors to consider, four billion years of life history, and innumerable trace fossils that resulted from that life, why should we waste our time being anthropocentric, or otherwise let ourselves be distracted by just our species in the here and now?

Yet in my study of modern traces, a misgiving haunts me as I otherwise blissfully follow the tracks of an alligator, measure the width of a ghost-crab burrow, or sketch the drillholes left by a woodpecker in a tree trunk. My apprehension is best communicated by the metaphor of a broken mirror. Such a mirror may reasonably reflect the truth in front of it, but also may be fractured enough that it obscures important details, rendering imperfect portraits of its subjects and potentially misleading its observers. In my world, the “cracks” in this mirror are the altered ecosystems and changed behaviors of other organisms, all of which have been and will continue to be affected by human behavior. So it turns out that no matter where I go to study the traces of modern plants and animals, I can’t ignore humans after all.

Behold! A beautiful beach at low tide on St. Catherines Island (Georgia), an island untouched by the hand of man. Well, except for all of the Native American shellrings, Spanish mission, logging, agriculture, slave dwellings, roads, and feral animals. Other than that, it’s untouched.

For example, the word “pristine,” applied so blithely to describe nearly all of the Georgia barrier islands, is about as appropriate as calling Mick Jaggar “virginal.” Starting with the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, about 12,000 years ago, the first humans in North America may have hastened the extinctions of mammoths, giant ground sloths, and other large mammals that lived near or on what is now the Georgia coast. Native Americans who lived on the Georgia islands, beginning about 5,000 years ago, used fire and agriculture to modify island landscapes, while also making settlements and building large shell rings. The arrival of Europeans on the Georgia coast in the 16th century then accelerated ecological change in the islands. With European colonization, more large animal species were extirpated from the southeast, including cougars and red wolves. New species of plants and animals were introduced, including feral hogs, which still inflict ecological havoc on island ecosystems today. Europeans and Americans clear-cut maritime forests for ship-building, and enslaved large numbers of people from western Africa, who filled in salt marshes and cultivated vast fields of rice and other non-native crops. Fresh water, formerly abundant in island interiors in alligator-made ponds and fed by artesian wells, became more scarce as alligators were overhunted, their habitats erased, and groundwater resources over-tapped. Europeans and Americans created new islands from ship ballast, which included soils holding seeds of more invasive species. Most recently, climate change – the largest and most over-arching human trace of all – has resulted in rapid sea-level rise during the past 200 years, quickening coastal erosion and salt-water intrusion of maritime forests. In summary, when someone describes the Georgia barrier islands as “pristine,” it brings to mind another movie quotation, but this one from the character of Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride: “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

An ecological interaction on St. Catherines Island beach told by traces, and one that would not have happened there before the 16th century: a feral hog (Sus crofa), its species originally native to Europe and a land-dwelling animals, scavenged a native and sea-dwelling horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) after the latter was stranded by a high tide. So how does an ichnologist apply this weirdness to the fossil record?

So does such a startling and potentially depressing realization disprove all of uniformitarianism, reduce all of our studies of modern traces to meaninglessness, and mock those genuinely gasp-inducing moments of loveliness we experience on the Georgia barrier islands? Of course not. Just like cracks in a mirror, or the faults we might see in our loved ones, we ichnologists just accept that this legacy is part of our changed world, overlain as it is by the traces of human behavior. In this sense, the environments and traces we study and appreciate today are palimpsests, manuscripts being overwritten by a mixture of traces by modern and exotic species, humans included. This knowledge does not make our science any less significant or fun, and certainly should not cause anyone else to huddle indoors and use all of their spare time to correct people who are wrong on the Internet. Instead, it should inspire you to go outside, find some traces, and be awed at what these traces tell you about their makers and their evolutionary heritage. Give thanks that you can see them here and now, the most recent of marks left by life in our 4.5 billion-year-old planet. And that’s a beautiful practice, no matter how flawed your mirror might be.

A trail with its tracemaker, always a welcome sight on a Georgia beach, but this one was particularly striking. The tracemaker is a lined sea star (Luida clathrata), and it was making a trail on the exposed sandflat as it sought the comfort of sea water. Yes, I threw it back into the water after taking the photo, with the hope I would see its traces again some day.

Anthony (Tony) Martin is an ichnologist, paleontologist, and geologist, who teaches in the Department of Environmental Studies at Emory University. His most recent book is Life Traces of the Georgia Coast: Revealing the Unseen Lives of Plants and Animals (Indiana University Press), and he blogs regularly at his Web site, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast .

January 20, 2013

Greek Myths You Never Heard Of

by Tracy Barrett (W&M Contributor)

Nonfiction was my first love in writing for younger readers. I had published seven nonfiction books—mostly American history and biography—before my first novel came out, and since then I’ve published three more.

A vase in the Getty Villa in Malibu was the inspiration for my current project. It shows a scene from a myth that must have been familiar to people viewing it at the time it was made, but was new to me. (There’s a similar vase in Spain’s National Archaeological Museum in Madrid.) It shows Herakles (identifiable by his size and lion-skin) with a pole over his shoulder, from either end of which dangles, upside-down, an odd-looking small man.

A vase in the Getty Villa in Malibu was the inspiration for my current project. It shows a scene from a myth that must have been familiar to people viewing it at the time it was made, but was new to me. (There’s a similar vase in Spain’s National Archaeological Museum in Madrid.) It shows Herakles (identifiable by his size and lion-skin) with a pole over his shoulder, from either end of which dangles, upside-down, an odd-looking small man.

It turns out that the myth is a very funny one (and too long to recount here) and it got me curious about other myths that I wasn’t familiar with. In the process of tracking them down, I’ve found a lot of bizarre and contradictory tales, strange critters, and many, many unhappy love stories. It appears that in ancient Greece, falling in love led to death as swiftly as it did for women who had the misfortune to catch the eye of Captain Kirk.

Here’s one tidbit that surprised me: Did you know how many kinds of nymphs there were? I thought that once you had mentioned naiads (water nymphs) and dryads (tree nymphs), that was pretty much it. But no. Here’s a very abbreviated list of nymphs (names are in the singular) and what each is associated with:

alseid: sacred groves

anthousa: flowers

aura: breezes

dryad: forests

epimeliad: flocks of sheep and goats

hamadryad: oak and poplar trees

leimakis: meadows

limniad: lakes, marshes, swamps

naiad: fresh water

napaea: valleys

nereid: Mediterranean Sea

oceanid: oceans

oreiad or oread: mountains

potameid: rivers

There are lots more. Each kind of tree has its own type of nymph, for example.

As I often do here, I’m asking for your help. Do you have any favorite Greek myths that most people don’t know about? My rule of thumb is that if it’s mentioned by Edith Hamilton, it’s too well known. Thanks in advance!

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

January 18, 2013

The Baburnama : An Emperor Tells His Own Story

By Pamela Toler (Wonders and Marvels Contributor)

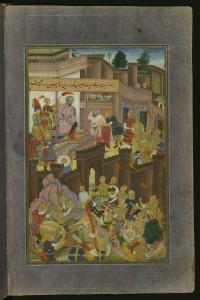

‘Ali Dust Taghayi Paying Homage to Babur

Zahir-u-din Muhammad Babur was the first Mughal ruler of India–one of history’s great empire builders by any standard.

Born in 1483 in the Central Asian kingdom of Ferghana (part of modern Uzbekistan), Babur was descended from two great conquerors: Genghis Khan and Timur (known in the west as Tamurlane). After being edged out of his own kingdom, he conquered Samarqand when he was thirteen, lost it, conquered it again when he was nineteen, and lost it again a year later. He carved out a new kingdom for himself in the mountains of Afghanistan and then went on to conquer a large section of northern India.

Much of what we know about him comes from his autobiography, the Baburnama (Book of Babur). It’s not clear what inspired Babur to write his memoirs. Historical accounts were popular in the Islamic world of his time, but there was no tradition of royal memoirs. His choice of language was also unusual. Babur was perfectly at home writing Persian, the literary language of Central Asia at the time. But he chose to write the Baburnama in Chagaty Turkish, the language spoken by himself and his people.

The memoir is lively, personal and direct. Babur begins the story when he inherited the throne at the age of twelve and ends in mid-sentence in September, 1529, a year before his death. He paints a picture of a warrior who partied as hard as he fought. He loved wine, melons, and gardens. He hated India, which was, in his opinion, lacking in all three. He was proud of his ability to write Persian poetry–and pleased to recite it at a party. (Poetry was a courtly skill and popular party game in the Central Asia kingdoms of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, just as it was in Elizabethan England and eighteenth century France.) He tells us what he did, thought and saw–not to mention how much he drank and how sick he was afterwards. He details who was at each event and why their presence was important. He outlines his military strategy at important battles. He complains about India, which he described as “a place of little charm”, but describes its animal and plant life with careful, loving detail.

It is, in short, an intimate self-portrait of a prince, warts, binge drinking, and all. “I have simply written the truth,” he tells the reader at one point. “I do not intend by what I have written to compliment myself: I have simply set down exactly what happened…May the reader excuse me; may the listener not take me to task.” Speaking only for myself, this reader hung on every word.

Image courtesy of the Walters Art Museum

January 14, 2013

Did Twain use the F-word?

Caroline and Mark Twain

“In certain trying circumstances, urgent circumstances, desperate circumstances, profanity furnishes a relief denied even to prayer.” Mark Twain, A Biography

“You do not want to be a dirt-worshipping heathen from this f—–g point forward. Pardon my French.” Al Swearengen, HBO’s Deadwood

For the past five years I’ve been immersed in the letters and newspaper articles of Samuel Langhorne Clemens AKA Mark Twain, especially those written between the years of 1861 and 1866, when he lived in Nevada and California.My interest in this period was sparked by HBO’s Deadwood, a TV series that ran three seasons from 2004 to 2005, charting the rise of the notorious mining town in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It was the first ‘Western’ that made me sit up and cry ‘That’s what it would have been like!’ I love it when historical fiction gets the details of the period right: the food, the clothes, the speech patterns, the customs, the environment, the morals, the manners. Deadwood did this in spades.

The series’ creator and show-runner David Milch immersed himself in the primary sources and then gathered a fine team of set- and costume-designers around him so that he make the world as convincing as possible. And he gets it right, in every respect but one: his characters, especially the suitably-named Al Swearengen, curse using words that would make a Comanche blush. Milch he didn’t just sprinkle them in. He threw them in as liberally as beans in chili con carne. Sadly, this decision might have been the fatal flaw of the series, which should have lasted more than three seasons. I often tried to convince friends to watch but most were put off by the gattling-gun barrage of F- and C-words.Twain has been posthumously rapped on the knuckles for using the N-word, but did he ever – like Al Swearengen – use the F-word?

Did they really cuss like that back in the 1860s and 1870s? To find the answer I moseyed on down to my primary sources, particularly the letters of Mark Twain who was notorious in his day for his ability to swear. His own newspaper, The Daily Territorial Enterprise affectionately dubbed him “Profaner of Divinity” and his friend Steve Gillis once jokingly urged Twain not to shoot at a howling dog who was disturbing their sleep. “Just swear at him. You can easily kill him at any range within your room.”A friend later wrote of his swearing while playing billiards, “…occasionally made a very bad stroke, and then the varied, picturesque, and unorthodox vocabulary, acquired in his more youthful years, was the only thing that gave him comfort. Gently, slowly, with no profane inflexions of voice, but irresistibly as though they had the headwaters of the Mississippi for their source, came this stream of unholy adjectives and choice expletives.”

So was Twain a literary Al Swearengen? At first I came across charming and chuckleworthy examples of Twain-cussing:

“By jings!”

“Dang my buttons!”

“By the humping, jumping Jesus!”

In a great essay on the language of Deadwood, professor Geoffrey Nunberg observes: “The taboo against profanity comes from on high; the taboo against obscenity comes from within.” Obscenity RapI thought I had found my answer: Twain blasphemed – defying the taboo from on high – but Swearengen obscened, prodding the taboo that comes from within. His expletives all had to do with crude bodily and sexual functions and his liberal use of the F- and C-words. Twain’s cursing was blasphemous, using sacrilegious words like damn, hell and Jesus Christ.

Twain himself cheerfully admits to “blasphemy”. Before he went west he promised his ma he would not swear and is always teasing her about this. In one of his letters home he tells of a particularly slow and stupid horse named Bunker who “required all the black-snaking and shoving and profanity at our disposal to keep him on the move five minutes at a time. But we did shove, and whip and blaspheme all day and all night, without stopping to rest or eat, scarcely.”

It is hard for us today to imagine the shock value of words like damn and hell a century ago. Many contemporaries of Twain censored themselves thus: d—n, dang, dam, dadburn, blank, even text-messagey acronyms like D.O.G. (danged old galoot).

In an illuminating essay entitled Deadwood and the English Language, Brad Benz quotes Nunberg (again) who writes that if the characters in Deadwood had sworn in a manner authentic to the period, they’d sound like Yosemite Sam. This is surely why Milch took the decision to sacrifice historical accuracy on the altar of dramatic license in this one aspect, in order to give us a sense of the barely subdued violence and rebelliousness of the people of Deadwood. I reckoned this meant that today’s F-word was equivalent to olden days’ D-word.

But then I found evidence that Twain could be obscene (i.e. use sexual and bodily function words) as well as profane.

In an after-dinner speech exclusively to men at the Stomach Club in Paris in 1879, Twain’s topic was ‘Some Thoughts on the Science of Onansism’ This very witty short piece includes repeated uses of the word “masturbation” – the subject of the talk – and not the sort of topic we are used to Twain expounding on. He employs some hiliarious and unique metaphors for the male member: “os frontis“, “Major Maxillary” and “Vendome Column” (this latter a monument which Twain looked out upon during his stay at the Hotel de Vendome in Paris.)

Much more elegant that Al Swearengen, I’m sure you’ll agree, but it definitely comes under the definition of bodily functions rather than religious insolence. And why not? The 27-year-old Mark Twain I’ve been getting to know was a hard-drinking, pistol-packing, ex-prospector turned newspaper reporter who lived in Virginia City, a mining town just as wild and woolly as Deadwood would be a decade later. In fact, Twain was generally considered crude. One reviewer remarked that Huckleberry Finn was “no coarser than Mark Twain’s books usually are…”

Then I came across the real eye-opener. In 1876, the summer than Tom Sawyer was published, Twain wrote what was once called “the most famous piece of pornography in American literature”. First written as a whim for his best friend the Rev. Twichell, this top secret, privately published tract is set in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Written in faux-Shakespearean, it is called 1601, (a deliberately obscure and even boring title referring to the year the fictional conversation is supposed to have taken place).

Calling it “pornography” is hyperbole, but this is Twain at his most risqué.It might be more accurately called Ode to a Fart and begins thus: Ye Queene.—Verily in mine eight and sixty yeres have I not heard the fellow to this fart. Meseemeth, by ye grete sound and clamour of it, it was male… (You can read the whole piece HERE.)

Twain confessed that 1601 was one of the few examples of his own writing that made him laugh. He obviously had great fun using real Elizabethan words such as tup and coition; pseudo-Elizabethan spellings like pricke, maidenhedde, capulate (i.e. copulate); charming pseudo-Elizabethan double-entendres as in a little birde nestling in a downy neste; and less Elizabethan euphemisms like tool, roger and member. With bollocks, piss and shit we become a little more edgy and finally a C-bomb or two (c–t not c——–r) that would have caused Al Swearengen to nod his approval. But nary an F-word in sight.

And why not? Was that word not around then?

In the foreword of his book The F-Word, Jesse Sheidlower writes that the word f–k wasn’t even printed in the United States until 1926 in a WWI diary. Even then, it was not used as an expletive but rather in its verbal sense, for the act of intercourse.

The only instances of the F-word I have found from the 1860’s are in the Journals of Alfred Doten, where he uses the word in the verbal sense written in a code of his own devising. (The word appears as vcuk, not very opaque.) Doten and Twain were colleagues moving in exactly the same circles, so Twain must have known it. But Doten’s usage confirms that the F-word was NOT used as a swear word back then.

So, in answer my original question: No, Mark Twain did not use the F-word.

So, in answer my original question: No, Mark Twain did not use the F-word.

At least not in print.

Caroline Lawrence is the author of a passel of history-mystery books for kids. Her new P.K. Pinkerton Mysteries series is set in Nevada Territory during the era of the Silver Boom. P.K. Pinkerton and the Deadly Desperados is out in paperback March 7th 2013, and P.K. Pinkerton and the Petrified Man is out on April 18th.

January 13, 2013

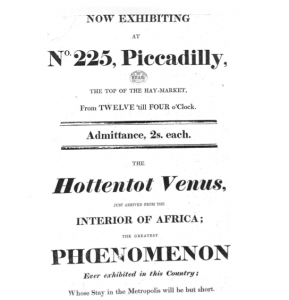

The Hottentot Venus

Throughout Georgian London there are many ‘freaks’, whose main source of income was displaying themselves: tall or strong women, tiny people, the prematurely aged (probably suffering from progeria) and ‘mer-people’. Sexual freaks such as bearded ladies or hermaphrodites were particularly popular. Anything exotic or ‘other’ caused queues to form in the street outside the chosen venue of display. All of these factors combined to make the exhibition of Saartjie (‘little Sara’ in Dutch) Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus, at 225 Piccadilly one of the sideshows of the age.

Sara was of the Khoikhoi people of South Africa. They had proved of particular interest to missionaries and early travelling scientists for numerous reasons, not least their distinctive features, often termed simian, and their clicking language. However, the greatest attraction for the ‘collectors’ of natural phenomena of the day was the appearance of Khoikhoi females: predisposed to carrying large amounts of fat on their breasts and high on their buttocks (called steatopygia). In addition to these distinctive features, the women of the tribe wore little or no clothing when in their natural environment, making their super-developed genitalia the focus of great curiosity for white male visitors.

Sara’s origin is unknown. She may not have grown up with the Khoikhoi, but been the child of enslaved parents. Alexander Dunlop was a ship’s surgeon and also acquired ‘specimens’ of all kinds for museums from the African Cape. In 1810, he brought Sara to England through Liverpool. She had been working in the Cape for a man named Peter Cezar, who had likely named her Saartjie Baartman, but Dunlop had promised her fame and fortune before the English public.

Upon her arrival in England, Dunlop sold Sara to a showman, Henrik Cezar (apparently coincidental). She was brought to London, and soon a flyer was produced advertising her presence, and the invitation to view, at 2 shillings a go. Charles Matthews was a keen ‘viewer’ of all London freakery, and he recorded his visit to the Hottentot Venus:

‘He found her surrounded by many persons, some females! One pinched her; one gentleman poked her with his cane; one lady employed her parasol to ascertain that all was, as she called it, ‘nattral.’ This inhuman baiting the poor creature bore with sullen indifference, except upon some provocation, when she seemed inclined to resent brutality.’

Matthews also referred to Sara being restrained by her ‘keeper’, making the whole idea by turns both grim and dismal in modern eyes. Sara was however, fully clothes during her exhibition, although the dress was tight in order to show her curves. Her naturally small waist was bound by African beads and ornaments for emphasis.

Sara’s exhibition caused an uproar, both by those rushing to see it, and amongst the more sensitive and also amongst the abolitionists who saw her condition as slavery. The Morning Chronicle, a liberal newspaper featured a letter on the 12th of October 1810 declaring, ‘It was contrary to every principle of morality and good order,’ but Cezar soon responded, argued that it was Sara’s right to exhibit herself and thus earn her living, just as if she were a giant or a dwarf. Sarah, however, was not like the other exhibits, she was all of them combined: female, black, physically unique and sexually intriguing.

Sara’s situation prompted a court case, with her would-be protectors stating that she was held against her will and pressing for her repatriation to Africa. The case failed, with the court finding for Cezar, but it soured the exhibition in London and Sara and Cezar moved on to Manchester (where she was baptised) and probably, Ireland.

In 1814, Sara was in Paris, being exhibited by an animal trainer and the following year would be studied by professors from the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle. She was finally studied nude, having taken a great deal of persuading, and the resulting images of her were presented in a book about exotic animals. Prurience continued to masquerade as science and upon her death in 1815, she was anatomised in Paris by Georges Cuvier, with particular and particularly distasteful attention given to her genitalia. A cast of Sara’s body and her skeleton remained on show in Paris until the late 1970s, when she was finally able to take a break from exhibiting, it having taken only one hundred and seventy years for people to understand, as the reader of The Morning Chronicle had done in 1810, that it was an ‘offence to public decency’.

January 11, 2013

Lenin’s Map of the Future

By Eric Laursen (W&M Contributor)

1961 Soviet Commemorative Stamp

For GOELRO, 1920 Electrification Campaign

In December 1920 Russia was embroiled in civil war, and Moscow was short on food and fuel, rapidly heading into a cold, dark winter. Yet rather than focusing on survival, the Bolsheviks launched a massive ten-year electrification campaign at the world-famous Bolshoy Theater. In defiance of a shortage of ink and paper, delegates to the Eighth Congress of Soviets were given 5000 copies of a four-color 50-page synopsis of the original 672-page plan. On a stage that usually held dying swans and singing divas, Lenin and the Director of the Soviet Electrification Commission gave rousing speeches in front of a map of the Soviet Union inset with light-bulbs, each designating a future power plant. Soviet historians later endowed the map with an almost supernatural power. According to one source, the lights of the Bolshoy were dimmed to accommodate it. Other accounts make the unlikely claim that the map caused blackouts in regions of Moscow. Whatever the wattage, this map of the future gained real power not through copper wires but through the propaganda machine of the Soviet Union, which reproduced its light not only in awestruck written accounts, but also on postage stamps, paintings, pins, and even children’s cartoons throughout the twentieth century.

H.G. Wells’s account of his interview with Lenin in October 1920 depicts the Soviet leader as a slightly unhinged visionary whose belief in the transforming power of science far exceeds the bounds of common sense (or science fiction!). Under Wells’s pen, Lenin becomes the ultimate mad scientist, launching with the electrification campaign “an age of limitless experiment” and seeing a “utopia of the electricians” superimposed on the ruined cities of a war-ravaged country. The materials and speeches surrounding the electrification campaign support Wells’s claim, as exemplified by this passage from a 1920 brochure: “And now every cultural center above all can be characterized by the glow of the electric fire that burns in it at night. The electric searchlight with its fiery sword cuts through the darkness of the night for tens of miles–these are the first rays of those electric suns that the utopians dreamed about.” In Lenin’s electrician’s utopia “cultural centers” would be marked not by a church, museum, or government building, but by “electric suns,” and eventually the entire world would become a single cultural center, a network of enlightened people all connected by Bolshevik power lines.

Shass-Kobelev

“Lenin & Electrification” (1925)

On a 1925 propaganda poster “Lenin & Electrification” we see the electrified landscape promised by Lenin’s map, a mechanized pastoral made possible only by tapping the unharnessed power of the earth: “Construction of the Volkhov hydroelectric dam will give current!” To the left of this arching proclamation is the Volkhov dam and to the right an electric tower that sends blue lightning bolts down to a light bulb, which points toward Lenin’s image, made celestial by his death the year before. At the bottom of the poster is the formula that Lenin delivered at the launching of the electrification campaign in 1920: Soviet Power + Electrification = Communism. After his death, Lenin’s image becomes a symbol for Soviet power, which links it to revolutionary tradition and makes of it the “electric sun” promised by the electrification campaign. Lenin and his light-bulb (nicknamed “Lenin’s lamp” during the electrification campaign) embody the variables in his formula. When added together they promise to produce communism, a state of being that requires the transformation of the natural world into an electrician’s utopia, a reworked landscape envisioned by Lenin’s map of the future.