Holly Tucker's Blog, page 64

September 9, 2013

Menotoxin – when menstruation can kill?

By Helen King (W&M Regular Contributor)

In the 1920s there was a serious medical debate about an invisible substance called ‘menotoxin’. This was believed to exist in menstrual blood; it could blight flowers and prevent jam from setting, and bread from rising. The theory can be seen as a surprising throwback, in the age of germs (germs, rather than air or strange vapors, as the cause of disease, go back to the 1870s or so – although the theory was slow to catch on). Menotoxin seems to resurrect a very ancient idea about pollution arising in the female body, an idea found particularly in Pliny’s Natural History, a work written in the early Roman Empire but well known in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Here, the malign influence of a menstruating woman included her power to blight plants through her breath and through her touch, or to kill insects infecting crops merely by walking through a field (well, there’s a plus!).

Menotoxin theory was developed in the 1920s by Béla Schick (most famous for the ‘Schick test’ used to detect immunity to diphtheria toxin). But it didn’t end there. In 1974 there was a lively debate about menstrual pollution in the medical journal, The Lancet, while some orthodox Jewish websites continue to quote Schick’s findings with approval today.

The most famous menotoxin story concerns an experiment performed by Schick on August 14, 1919 (the story was still being repeated by him to his colleagues in 1954). One afternoon he received a bunch of ten dark red roses (isn’t the color wonderfully suggestive?), which a maid placed in a vase of water. She did not want to do this, but he insisted. When the flowers wilted and died by the next morning, he made inquiries and discovered the maid was menstruating. She said that this always happened to her, if she touched flowers during her period. Schick then carried out experiments with menstruating and non-menstruating servant girls, on flowers and also on making dough, concluding that something was excreted through the skin of those menstruating that had a toxic effect .

When this story was retold in The Lancet in 1974, correspondents wrote in to repeat traditional beliefs found all over Europe that menstruating women should not try to bake bread, preserve meat, sow seeds, reap fruit and so on – and, in a charming modern twist, shouldn’t have a perm, because it wouldn’t ‘take’. Another correspondent cited work in the 1930s and 1940s which apparently showed that the toxin derives from endometrial debris and that it is most lethal at the start of a period, but in the following issue of The Lancet this was attacked and it was argued that the rats in these experiments had died from bacterial infection; if they were given antibiotics before being injected with menstrual extracts, they suffered no harm. The correspondence ground to a halt when another doctor wrote in to argue that all these beliefs were superstition, arguing that ‘a 1924 photograph of a wilted daisy … and the unexplainable death of one Italian tree … are insufficient data on which to build a case in 1974’ (Ernster, Lancet June 29, 1974, 1347). But a further burst of activity on menotoxin occurred in 1977, with a group of botanists and physiologists conducting experiments on menstrual blood, trying to find a substance that could affect not only plants but also women’s moods.

So what’s it all about? In earlier belief systems, in which it was thought that the blood was the material from which a fetus was made, the expulsion of this blood made it (in the words of the great anthropologist Mary Douglas) ‘matter out of place’, and thus something dangerous. Maybe there was simply a male fear of women’s hidden powers. But if so, all these taboos are doing is keeping women away from their normal domestic duties! Perhaps the belief that women should be forbidden from doing certain household tasks while menstruating would even have some benefits for the women themselves, giving them a few days off; across history, some cultures have imposed a time of ‘menstrual seclusion’ which could have had the same effect. But next time you read that bread may not be any good due to an ‘insufficient rising period’, maybe you’ll have a double-take moment!

September 8, 2013

Five Psychiatrists and Psychologists Who Examined Top Nazis at Nuremberg

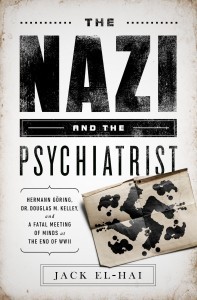

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

September 10 marks the official release of my new book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII (PublicAffairs Books). I’ve worked steadily on this book since 2007, when I found in a private family collection a treasure trove of historic documents intimately connected with the 1945-46 International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, including medical and psychiatric records of the top Nazi defendants that had not seen the light of day for more than 60 years. My book trailer gives an overview of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist.

I’ve worked steadily on this book since 2007, when I found in a private family collection a treasure trove of historic documents intimately connected with the 1945-46 International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, including medical and psychiatric records of the top Nazi defendants that had not seen the light of day for more than 60 years. My book trailer gives an overview of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist.

Throughout that exciting time of research and writing, I gathered a great deal of information on psychiatrists and psychologists who gained access to the Nuremberg prisoners to examine and assess their psyches. And here I present a list:

1. Douglas M. Kelley, M.D., who is the subject of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist. Born in Truckee, California (and the grandson of the first historian of the ill-fated Donner Party that perished in the nearby mountains), Kelley was trained as a psychiatrist at the medical school of the University of California and became an early exponent of the Rorschach inkblot assessment. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942 and quickly broke new ground in treating World War II soldiers for combat exhaustion, commonly known as shell shock. At the end of the war, Kelley received orders to travel to Mondorf-les-Bains, Luxembourg, to study the mental competency of the Nazi leaders being held there. His patients included Reichsmarschall and Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi “philosopher” Alfred Rosenberg, and anti-Semitic propagandist Julius Streicher, and many others. Kelley followed these prisoners to Nuremberg, where preparations were underway for their trial. There deputy Führer Rudolf Hess joined the group, and Kelley continued his examinations using the Rorschach inkblot test and other psychological assessments.

Douglas M. Kelley, M.D.

The psychiatrist had developed his own pet project — a search for psychological traits common to the prisoners that would allow Kelley to describe a “Nazi personality.” Kelley found something much different from what he had hoped, although he built an extremely close relationship with Göring. Kelley’s inability to identify the expected qualities of a Nazi mind rattled him, as did Göring’s suicide in October 1946. By that time, Kelley had changed his professional focus from psychiatry to criminology, and he began a long spiral downward through alcoholism, marital strife, workaholism, and fierce inner rage. He committed suicide on New Year’s Day 1958 by swallowing cyanide, the same poison Göring had used to end his life.

2. Gustave Gilbert, Ph.D. A New York-born psychologist who arrived in Nuremberg two months after Kelley, Gilbert had similar ambitions. He hoped to write a book with Kelley about the top Nazis, but Kelley — confident he could produce a book on his own and unimpressed by Gilbert’s Rorschach skills — abruptly broke their agreement. Although Gilbert was Jewish, his fluency in German endeared him to some of the Nazi defendants. Eventually Gilbert and Kelley both wrote their own books about their Nuremberg experiences.

3. Leon Goldensohn, M.D. Goldensohn became the Nuremberg staff psychiatrist in 1946 when Kelley returned to the U.S. He had a gentler and more soft-spoken demeanor than his predecessor, and a volume of his conversations with the top Nazis was published in 2004, decades after his death.

4. Donald Ewen Cameron, M.D. As the opening of the International Tribunal neared in the fall of 1945, Cameron, a Scottish-born psychiatrist then teaching at McGill University, teamed with psychoanalyst Nolan D.C. Lewis to produce a report for the court on the mental stability of Rudolf Hess. Agreeing with Kelley, they determined that Hess was sane and not psychotic. Cameron later gained notoriety for performing mind-control and behavior modification research for the CIA.

5. Paul L. Schroeder, M.D. An Army psychiatrist like Kelley, Schroeder occasionally assisted in the administration of psychological tests and served on a panel of psychiatrists from the U.S., the U.S.S.R., and France to examine Julius Streicher and determine his mental capacity to participate in his trial.

All of these men — with their varying aims, approaches, and areas of expertise — figure in the story of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist in different degrees.

If you read the book, please leave a comment below or reach me through my website and let me know what you think.

September 6, 2013

Poisoning Enemies in the Ancient Mideast

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

The insidious tactic of poisoning one’s enemy—noncombatants and soldiers alike—is nothing new, only the technologies have changed. Choking clouds of dust with the effect of tear gas and rains of red-hot burning sand with the effect of phosphorus bombs are two examples of chemical weapons and biological strategies actually employed in antiquity (see for example, “Alexander the Great and the Rain of Burning Sand,” and “Before Pepper Spray,” among my other posts, in Wonders and Marvels archives).

Several instances of poisoning water and food supplies in North Africa by the Romans and their enemies the Carthaginians were reported by historians in antiquity. Such practices raised ethical issues even then but that did not stop some commanders from using biological and chemical strategies to destroy entire populations. Some Romans, for example, bristled at the very notion of resorting to toxic weapons because they contradicted the traditional ideals of Roman courage and honor. When several cities in the Near East revolted against Roman rule in 129-131 BC, however, the general sent to quell the rebellion turned to poison. Manius Aquillius was known as a cold-blooded commander notorious for his harsh military discipline and his ruthless suppression of the uprising in Rome’s new Province of Asia Minor (Turkey and Syria) led to disturbing rumors in Rome. The Roman historian Florus reported what occurred in his military history written in about AD 140.

The insurrection against Rome was led by Aristonicus of Pergamum (Turkey) succeeded in mobilizing ordinary people, rich and poor as well as slaves. Several cities joined the revolt and Aquillius’s Roman army was unable to gain control. “Aquillius finally ended the Asian War,” wrote Florus, “but his victory was clouded. For Aquillius had used the wicked expedient of poisoning the cities’ springs to force their surrender.” Florus was very clear about the immorality of such measures. “Though it hastened the Roman victory, it brought shame because he disgraced Roman arms and battle skills which until now had been unsullied by the use of foul drugs.” Aquillius’s poisoning of the entire populace of several cities, declared Florus, “violated the laws of heaven and the practices of our forefathers.”

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009) and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

August 29, 2013

The Sex Life of Dogs in the Eighteenth Century

By Lisa Smith

A bitch is licking its suckling puppies. Etching by C. G. Lewis. 1848, after E.H. Landseer. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

I started out rifling through old animal husbandry books on a whim, looking for references to beagles. (See The Art of Beagling and Buffon and the Beagle here at W&M.) Along the way, I discovered more than I’d ever guess about the canine sex life: mating tips, aphrodisiacs and birth control, and venereal disease… Dogs, as it turns out, had a lot in common with humans.

In The Huntsman (London, 1780), Nicholas Cox offered advice on breeding that seemed remarkably similar to human medicine. The female dog “must come of a good kind, strong, and well proportioned in all parts, having her Ribs and Flanks great and large”. The marks of good health in women were also signs of fertility. The most important consideration for the male dog was age: “let him be young, if you intend to have light and hot Hounds; for if the Dog be old, the Whelps will participate of his dull and heavy nature”. Old men and old dogs might prove able to get up to new tricks, but their fertility was problematic. Many medical writers despaired that men waited until too late to marry, resulting in degenerate seed. To breed good lines, good seed was crucial.

There were remedies to ensure that dogs mated and to maintain the size of the pack. If a female, “grow not naturally Proud so soon as you would wish, you may make her so”, Cox proclaimed. The canine aphrodisiac for either sex included similar ingredients to human treatments: two heads of garlic, half a castor’s stone, watercress juice and twelve Spanish Flies. Cooked into a mutton broth and served two or three times to the dog, “she will infallibly grow proud”.

To control the pack population, the only option was to spay the female. This needed to be done before she bore a litter or while she was pregnant. Done while she was in heat, it would “endanger her life”. The operation required close attention. “Take not away all the Roots or Strings of the Veins; for if you do, it will much prejudice her Reins [kidneys]”, insisted Cox, as it would slow her down. For human couples seeking to control fertility, surgery was unthinkable between the lack of anaesthetic, the permanency of the surgery and wider social concerns about depopulation and degeneracy.

There were also parallels between dogs and humans when it came to venereal disease. In Farriery Improved (vol. 1, London, 1789), Henry Bracken compared the disease in humans, horses and dogs. According to Bracken, the origin of the disease was the female of the species. His evidence was the Bible. A man might have many wives, but would stay disease-free if one of his wives did not contract it elsewhere. Convenient. This fit with what he saw in horses. A stud might mount six or seven mares in a season and remain healthy.

Dogs, on the other hand, “copulate so promiscuously, that they heat the Bitches, and thereby get the Clap, which often turns to an inveterate Mangyness” like leprosy in humans.* The canine treatment was simple—let nature take its course. Frequent urination washed the small urethral ulcers and prevented hard scabs from forming. Humans, however, tended to neglect their health, letting scabs form. When the “venereal venom” could not discharge, it and infected the blood and bones. This touched on wider eighteenth-century debates about nature or intervention in medicine, as well as reflected the long-standing belief in purging unhealthy material from the body. Bracken was adament: the human body could self-cleanse, too, if people let it.

Dogs: not only man’s best friend, but a reflection of his sexual self?

*When syphilis appeared in Europe, people considered it to be related to leprosy. Leprosy was less common by the eighteenth century, but venereal problems were often seen as related to other problems of hot, poisoned blood, such as scurvy. Dogs were sometimes seen as dirty creatures and had been associated with outbreaks of the plague.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and teaches on the boundaries between natural and supernatural worlds.

August 20, 2013

Learning from the Pros

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

A few weeks ago I attended the 42nd annual Summer Conference of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. The keynote speakers were stars—writers, illustrators, editors, agents, publicists—and the breakout sessions covered every aspect of the industry from craft to publicity to how to negotiate a contract, and more.

A few weeks ago I attended the 42nd annual Summer Conference of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. The keynote speakers were stars—writers, illustrators, editors, agents, publicists—and the breakout sessions covered every aspect of the industry from craft to publicity to how to negotiate a contract, and more.

I gleaned several nuggets that will be helpful for writing historical fiction.

Deborah Halverson offered a session on setting. I’ve been to lots of sessions on plot, character, and pacing, but I’d never before seen one on setting. Setting’s just wallpaper, right? You provide enough to situate your reader in the context of your story, but then move on to more important things. I went anyway, mostly out of curiosity; creating a realistic setting is crucial for someone writing historical fiction (and also because I’m a big fan of Deborah’s blog, Dear Editor). I thought that it would be interesting but that I’d be lucky to get even one practical tip.

I wound up with lots more than one. I scribbled all over the handout, which provided examples of setting used to advance the plot and illuminate character. For instance (paraphrasing):

“What are you doing here?” he asked, pushing his bangs out of his eyes.

vs.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, using a handkerchief to turn the filthy doorknob.

The over-used bang-pushing doesn’t add anything to the plot or character (unless the character can’t afford a haircut) whereas in the second example, we learn that he is fastidious and that something is bad wrong in the house.

Deborah also spoke to the importance of sprinkling in bits of setting rather than describing it in one big information dump, again with many examples.

Another tip for writers of all genres: when describing a setting (or a character), add a quirky detail to make it real. Give a dragon crossed eyes, add a face-shaped knot to a board in an old barn (these are my examples; Deborah’s were better). It occurred to me that the house in It’s a Wonderful Life is a pretty generic rambling old ruin. But what detail does everyone remember, the one that turns the house from generic to specific? It’s the broken wooden ornament on the newel post, which drives Stewart’s character crazy until the end, when he kisses it.

I also picked up tips from a panel on world-building with four science-fiction writers (Veronica Rossi, Cynthia Hand, Brodi Ashton, and Tahereh Mafi). It occurred to me that science-fiction authors and historical-fiction authors face similar challenges:

We need to create an unfamiliar world in our readers’ minds without piling on description.

Usually our main character is a native of that world and wouldn’t comment on it (“Gee, there sure are a lot of slaves here in ancient Rome!” “It’s perfectly normal for parents to choose who you’ll marry!” “The Venusians are so weird-looking!” etc.), so we have to figure out a different way to convey that information.

A lot of research is required; I can’t have my characters using a cell phone and a science-fiction writer has to respect the laws of physics, or at least know what they are so she has an explanation for why she’s violating them. (A problem for me is avoiding research rapture—it’s all too obvious when an author is too much in love with a fact to leave it out even when it doesn’t advance the story, add to the character, or do anything other than shout, “ISN’T THIS COOL?”)

I sometimes think that although obviously I don’t know everything about writing, there’s not much left for me to learn in a one-hour conference session. Not true, as I found out a few weeks ago.

If you too are interested in learning more about writing historical fiction for young readers (children and young adults), please check out the Highlights Foundation’s Whole Novel Workshop on writing historical fiction, Nov. 3-9. I’m on the faculty!

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before retiring to write full-time. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before retiring to write full-time. Visit her website and her blog.

August 16, 2013

The very individual journey of novelists

by Stephanie Cowell

It strikes me what great individual journeys each and every novelist has had…different joys, different frustrations. As a writer you start off wanting to tell stories; somewhere along the way some of us add the desire to win a Pulitzer, make the New York Times best seller list, receive several million dollars in contracts — if we are not J.K. Rowling who with a billion dollars in assets never has to worry about paying her mortgage again (even if her home was Windsor Castle). Or perhaps if we are lucky and very  spiritual, we can live as some writers I heard of in an unheated cabin without electricity and an old typewriter. And of course no wifi…

spiritual, we can live as some writers I heard of in an unheated cabin without electricity and an old typewriter. And of course no wifi…

I think of productivity. I have been thinking recently a lot about the unique Harper Lee who wrote one novel in her life, To Kill a Mockingbird. There is a marvelous documentary about her called Hey Boo. In her twenties she came to New York from Alabama and accumulated a bunch of not quite finished stories. Kind friends who had extra money gave her a gift of a year off from her job at an airline reservation counter. A publisher found her very rough draft of her novel to be appealing and gave her a contract. For what she called two terrible endless years, she revised and revised until the book took its final form. She revised it in an old NYC apartment smoking endless cigarettes. And she never published anything again. She was working on something else for a time.

I was considering what a miracle story her one book was when news came from the BBC that ALL of Barbara Cartland’s novels will be published as e-books, well, some for the first time. That is, all 883 of them among which are 160 she never bothered to publish but kept in the drawer. This news came to me when I was feeling that I am a true sloth having published a mere five to this date. She did live until 98, still writing, but though I am much younger than that, I do not expect to catch up.

I remember one story of a truly great novel which took a long time to write: Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcemar. There is a preface in the edition I own which tells the story of the writing of it. She began it in her twenties and then World War II came and much displacement and she forgot about it until perhaps three decades or more later she was sifting through some old papers and found a letter which began with “Dear Mark.” She could not remember knowing anyone called Mark until it occurred to her that this was a fictional letter from Hadrian to Marcus Aurelius from her early draft. With that and one single line from the original, she wrote her novel. That gives me courage as I have a novel set in the ancient world which I have been working on for many years …

Seven years for War and Peace, four for Madame Bovary, five years for my own Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. Some books just spill out like a force of nature but most are revised and revised. Some writers have great books which no one will publish; others publish one book after another. Forty years to write a book or two months?

I am one of those writers who tend to find the shape of the story as she writes it, and therefore my work is 95% revision. It is very hard to simply settle into the way your work goes and what has been given to you to do without wishing you were more productive or famous. Shakespeare in his sonnet 29 writes about “desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope.” If Shakespeare envied someone else’s art and scope, what can the rest of us mortals do? And wasn’t it seventeen years before Jane Austen took her novel called First Impressions and turned it into Pride and Prejudice? Who knows how long it took Shakespeare from first words to final version of his Hamlet?

The more novelists I know, the more I realize how individual is every journey. And it is wonderful when people share it, but sometimes revising and rewriting seems like wandering for years in Dante’s dark wood, never able to remember exactly what path you took or when or why. And once it is done, you never know who will find it and what it may mean to them. It’s really quite miraculous…whether we are rich or poor, whether we write one wonderful book or (gasp!) nearly 900 of them.

______________________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

August 15, 2013

The Egyptian Hall

By Lucy Inglis (W&M Contributor)

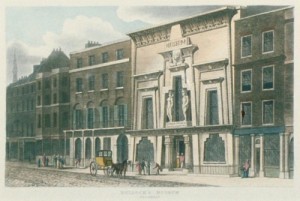

Eighteenth century Piccadilly was a place for all sorts of curiosities to be displayed. Almost opposite Burlington House, at 170–173 Piccadilly, a Starbucks coffee shop now sits where William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall once stood. From 1798, when Nelson triumphed at the Battle of the Nile, English interest in the ‘East’ began to soar. While obelisks and other monumental pieces had been leaking out of Egypt for a century, Napoleon’s heavy thieving from Luxor and Karnak made Egyptian objects desirable amongst the European elite. The victory of the Battle of the Nile also coincided with a period in which an extended grand tour took in Turkey or Egypt. The romance of the East rapidly took hold of the English upper-class imagination, with books, prints and Eastern costume all the rage.

Eighteenth century Piccadilly was a place for all sorts of curiosities to be displayed. Almost opposite Burlington House, at 170–173 Piccadilly, a Starbucks coffee shop now sits where William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall once stood. From 1798, when Nelson triumphed at the Battle of the Nile, English interest in the ‘East’ began to soar. While obelisks and other monumental pieces had been leaking out of Egypt for a century, Napoleon’s heavy thieving from Luxor and Karnak made Egyptian objects desirable amongst the European elite. The victory of the Battle of the Nile also coincided with a period in which an extended grand tour took in Turkey or Egypt. The romance of the East rapidly took hold of the English upper-class imagination, with books, prints and Eastern costume all the rage.

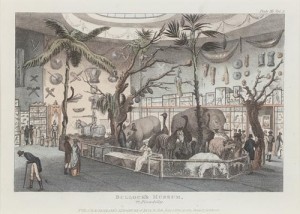

In 1809, Bullock’s Museum arrived in London from Liverpool. The following year, Bullock turned down the opportunity to display the Hottentot Venus, Saartjie Baartman.His reasons are not recorded. In 1812, the Egyptian Hall was ready for occupation. It must have appeared quite surreal to the man on the street. The grand hall of the interior was an extraordinary replica of the avenue at the Karnak Temple complex, near Luxor. By 1819, Bullock was ready to sell his collection of real and spurious objects, and did so in an auction lasting twenty-six days. It was dispersed all over the world. Emptied of its original tenant, the Egyptian Hall received a new and rather more suitable guest: Giovanni Battista Belzoni, known to his English friends as ‘John’.

An Italian strongman and performer, with an English wife, Belzoni was a true adventurer: in 1817, he travelled to the Valley of the Kings and broke into the tomb of Seti I. From Seti’s tomb, Belzoni took a sarcophagus of white alabaster inlaid with blue copper sulphate of great beauty. The retrieval of the sarcophagus, however, was not without peril: the tomb was located in the catacombs, a maze of traps and dead ends, dug to confuse grave robbers. The French interpreter panicked and an Arab assistant broke his hip in a booby trap. Undeterred, Belzoni retrieved the sarcophagus and brought it to England along with the head of the ‘Younger Memnon’. Belzoni suffered constant vomiting and nosebleeds in Egypt, whilst Sarah was unaffected by so much as a case of sunburn – much to her husband’s chagrin.

London eagerly anticipated the imminent arrival of these treasures. Shelley’s famous poem of 1818, ‘Ozymandias’, was written for a newspaper competition held by The Examinerin advance of the arrival of Belzoni’s treasures. The exhibition opened at the Egyptian Hall in May 1821, but a year later the collection was put up for auction. The sale drew two of the greatest collectors of the day: the British Museum and Sir John Soane. The Museum acquired the colossus and Soane the sarcophagus. John Belzoni, financially if not spiritually satisfied, handed in the manuscript of his travels to his publisher, John Murray, and set off for Benin. He died of dysentery one week after arriving there.

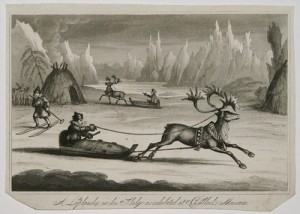

Before long, the Egyptian Hall moved on to displaying real-life Laplanders, who gave sleigh rides up and down the central space. It continued on as an exhibition space until redevelopment in 1904, when this extraordinary Georgian flight of fancy was replaced with offices as part of the great slum clearances.

August 14, 2013

The Secret of Vesuvius

Girolamo Ferdinando De Simone is an Italian-born, Oxford-educated archaeologist based in Naples. We met via Twitter because he likes my children’s book, The Secrets of Vesuvius, and might stage a shortened version using local schoolchildren on the north slope of Vesuvius. Finding himself in London for a colloquium on Herculaneum he tweeted me and we agreed to meet at the South Bank in London one Saturday for a coffee.

He and his girlfriend Ivana arrive looking like Italian movie stars. They are both from Naples and tell me lots of exciting things about excavations on the north slope of Vesuvius, sometimes called “the dark side” of Vesuvius. In return I let them in on a secret: the British Museum Pompeii Exhibition opens at 9am on a Sunday morning. They take the hint and we all meet the next day to go through it.

Although it is my seventh visit to this exhibition, my hour with Ferdinando opens my eyes. He shows me many things I’d never seen, even though they have always been right there in front of me.

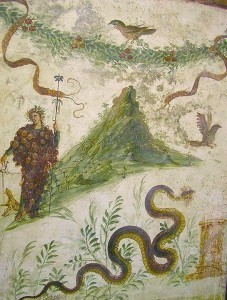

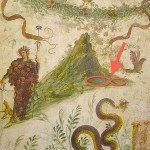

One of those many things is Dionysus, the god of wine.

We stand before the famous fresco of Dionysus and Vesuvius. Some scholars have wondered if this really shows the famous volcano. They are confused by certain elements including a strange “figure of eight” at its foot. Ferdinando believes this was the artist’s way of showing the double caldera (crater) inside the mountain. This is where Spartacus and his men camped roughly a century before Vesuvius’ famous eruption, when they were on the run. I have shown this fresco to pupils hundreds of times but had never noticed this element before!

We stand before the famous fresco of Dionysus and Vesuvius. Some scholars have wondered if this really shows the famous volcano. They are confused by certain elements including a strange “figure of eight” at its foot. Ferdinando believes this was the artist’s way of showing the double caldera (crater) inside the mountain. This is where Spartacus and his men camped roughly a century before Vesuvius’ famous eruption, when they were on the run. I have shown this fresco to pupils hundreds of times but had never noticed this element before!

Ferdinando tells me there were two peaks and in fact still are; the volcano’s official name is Somma-Vesuvius. The vineyards indicate the north slope, where he is now digging. It surprises me to learn that within a generation of Vesuvius erupting, the Romans were once again building on that slope. Volcanic ash is incredibly rich and vineyards would have produced fabulous crops.

I always tell school kids that Dionysus is wearing grapes and giving his pet leopard some wine. But as Ferdinando talks, I see that he is not wearing grapes, they are wearing him. The artist has shown a bunch of grapes with Dionysus inside. He inhabits the cluster. And he is pouring a libation, not trying to get his pet tipsy!

Ferdinando is frustrated that so many people think Dionysus only represents drunkenness and madness. Dionysus is also the god of theatre, plant fertility, resurrection and of course the crop the sustained the region. The whole economy of the Vesuvius region was dependent on grapes and wine.

This particular fresco, says Ferdinando, is about Cult. The Cult of Dionysus. We see it out of context, but was found on the left hand side of a shrine. Garlands, fillets and birds are almost always found on lararium frescos and we can even see an altar in the foreground (it looks like a truncated column with a lucky snake protecting it.)

The name of the god can be confusing. Dionysus is his Greek name. Bacchus is one of the names used for Dionysus in Roman times. It is the Latin version of Dionysus Bacchaus. He is also blended with Liber Pater, an Etruscan/Latin god who was already in Italy. So we have Dionysus in several incarnations: a baby reared by Hermes and the nymphs; a dignified and beautiful youth with long hair; a jolly older man riding a mule. His followers are satyrs, fauns, pans, nymphs and maenads. His special animals are the panther, snake and goat.

Now as we continue through the exhibition, I see Dionysus everywhere. I see him in the panther table, in the hanging marble disc, (“oscilla are 90% associated with the cult of Dionysus”) and in the many theatrical masks. (I forget that theatre started as part of the cultic worship of this god.) I see the cista mystica, the special box or basket containing objects for his cult: a veiled phallus, kantharos and syrinx (pan pipes). I see Ariadne abandoned on an island by Theseus and virtually dead, until Dionysus comes to “resurrect” her.

Finally, we come to two marble reliefs recently uncovered in a villa from Herculaneum. “This one my father discovered!” Ferdinando has written articles about these reliefs but this is the first time he has actually seen them. He points out the cult statue of Dionysus and a procession of people approaching it: two youths, a citizen and a maenad. This is a rare depiction of an ancient Greek rite, seen through Roman eyes.

Ferdinando draws my attention to the hand-gesture Dionysus makes as he holds the kantharos, his special cup. We think of this gesture as cornuto, the horns, used to mock a cuckold, but in Roman times it was a secret sign like a finger to the lips saying “Look but don’t tell…” It may also have been apotropaic: a sign against evil.

The most exciting thing is the revelation that the dagger-like object in one of the youth’s hands is an acus, a vintner’s tool for punching holes in the ground for vine roots. It has flanges to ensure the optimal depth for planting a new vine, not too shallow, not too deep.

There is more, much more, but I have run out of space. And you have almost run out of time. The Pompeii Exhibition will only be on for another month or so in London.

When you go to the Pompeii or the exhibition at the British Museum look for its patron god, Dionysus. You will see him everywhere. He is the Secret of Vesuvius.

August 11, 2013

On Faking Virginity

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (W&M Contributor)

Virginity was a precious commodity on the marriage market in the early modern era, and it continues to be in some cultures today.

Virginity was a precious commodity on the marriage market in the early modern era, and it continues to be in some cultures today.

A couple of years ago, the BBC aired a story about a device designed to help a woman fake her own virginity. Called an artificial hymen, it was made in China and could be ordered online. Many of these were being sold to customers in North Africa, a situation that prompted Egypt to attempt to ban their import.

I encountered this story as I was writing a biography of two sisters, noblewomen at the courts of France and Italy, who had created great scandal by running away from the marriages that had been assigned to them. Marie Mancini, the older of the two, had been the young love of king Louis XIV before his own marriage. He had been forced to abandon her when it came time for his politically determined marriage to a Spanish princess. His youthful romance with Marie has always been described as “innocent” in the history books. Historians have become quite attached to the idea that theirs was a romance that was not consummated. In the title of my biography I use the word “mistress” to describe Marie’s relationship to the king, and I received some objections to that term from readers who pointed out that Marie had remained a virgin until her own arranged marriage, to the Roman prince Lorenzo Colonna.

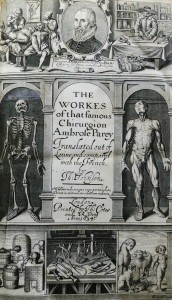

On what basis, I thought, do we continue to assume that Marie remained a virgin until her wedding night? Was it possible that young women of her time knew how to convincingly fake it? A little more research led me to Ambroise Paré, whose 1573 treatise on “monsters and marvels” includes the description of popular techniques, known since the time of Galen, for creating false evidence of virginity by inserting a fish bladder filled with blood into the vagina , so that the sheets on the wedding bed would be stained with the necessary proof. Paré further argues that the very existence of the hymen in the female anatomy is at best questionable, and possibly simply a myth.

More searching convinced me that the project of assuring ‘evidence’ one’s virginity might have been a familiar one to many young women, whether or not they had previously had intercourse with a man. In seventeenth-century comedy, a familiar scene is a dialogue between a young bride-to-be and her governess, who advises her on how to act like a virgin on her wedding night. And when I looked more carefully at Marie Mancini’s story, the only evidence that I found supporting the common reference to her virginity was a proclamation made by her husband on the morning after their first night together. He was pleased, he announced to his friends, to find that his young wife was a virgin, even though she had been loved by a king. This public announcement served the interests of this powerful nobleman, famous for his vanity, in more than one way. Of course he would want to claim possession of a virgin bride, but perhaps even more important to him was making a statement that would suggest that he was more virile than the French king. And Marie? She had been very ill on her wedding night, after a long and difficult voyage from France to her rendez-vous outside of Milan with her Roman husband. Her governess, who had accompanied her, at first asked the bridegroom to postpone the consummation of the marriage, and then when Colonna insisted, she managed to get him to agree to wait a couple of hours while she went with Marie to take communion in a nearby chapel.

More searching convinced me that the project of assuring ‘evidence’ one’s virginity might have been a familiar one to many young women, whether or not they had previously had intercourse with a man. In seventeenth-century comedy, a familiar scene is a dialogue between a young bride-to-be and her governess, who advises her on how to act like a virgin on her wedding night. And when I looked more carefully at Marie Mancini’s story, the only evidence that I found supporting the common reference to her virginity was a proclamation made by her husband on the morning after their first night together. He was pleased, he announced to his friends, to find that his young wife was a virgin, even though she had been loved by a king. This public announcement served the interests of this powerful nobleman, famous for his vanity, in more than one way. Of course he would want to claim possession of a virgin bride, but perhaps even more important to him was making a statement that would suggest that he was more virile than the French king. And Marie? She had been very ill on her wedding night, after a long and difficult voyage from France to her rendez-vous outside of Milan with her Roman husband. Her governess, who had accompanied her, at first asked the bridegroom to postpone the consummation of the marriage, and then when Colonna insisted, she managed to get him to agree to wait a couple of hours while she went with Marie to take communion in a nearby chapel.

Time enough for an intimate conversation.

————————–

Further reading:

Goldsmith, Elizabeth C., The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. New York: PublicAffairs Press, 2012.

Louglin, Mary H., Hymeneutics: Interpreting Virginity on the Early Modern Stage. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1997.

August 9, 2013

“Call the Midwife” – or knit your own womb

By Helen King (W&M Regular Contributor)

(this post develops an earlier version that first appeared in July 2013 on http://departu.org.uk)

It was one of those moments that only happens when academics and practitioners are in the same room…

For about a year, I had been thinking about the history of visual representations of body parts, and had been introducing audiences in the UK and beyond to some of the knitting patterns available to make a womb. On knitty.com, for example, you can find a pattern from the amazing M.K. Carroll which allows anyone with needles and some bright pink wool to make a ‘cuddly’ womb with pipe-cleaner fallopian tubes and ovaries. If you think I’m making this up, look here.

M.K. Carroll took classes in anatomy and physiology which informed her work. But as she points out on the website, her knitted womb is ‘not completely anatomically accurate’. I was interested in two things here. First, the effect of knitting on making body parts look less terrifying and more ‘cuddly’, which is part of a wider movement in contemporary art towards knitting things that one would not normally associate with this medium; for example, cars. Second, the choice of what to include in ‘a womb’. In M.K. Carroll’s womb, tubes and ovaries and cervix are all important, and the cervix needs to ‘look plump (“pouty”, if you will)’.

I mentioned this to the other members of the De Partu history of childbirth research group, expecting the usual surprised response. Instead, they were not thrown in the slightest. ‘Oh yes’, they said, ‘we all know about knitted wombs. We have them, and we make them. They are very useful in parentcraft classes. Would you like us to show you our wombs?’

My jaw dropped. And once I saw the wombs, I was even more amazed and delighted. Firstly, because these wombs are not always brightly colored – in fact, one of the 1960s patterns that was kindly supplied to me by Lynn Balmforth, the librarian of the National Childbirth Trust, makes it explicit that these should be made in neutral, non-scary, colors, to make the effect more ‘acceptable’. Nor are they supposed to be ‘lifelike’. And secondly, because these wombs don’t bother with the ovaries and tubes – irrelevant by this stage of the proceedings! – but focus on the size of the gravid uterus and on the role of the cervix. They are used to show how contractions work and how the cervix dilates. A ball, representing the head, is pushed through the cervix and a ribbon through the external os can be used to control this.

This photograph was sent to me by Sue Tully, who is a Senior Lecturer in Midwifery at Bournemouth University; it gives you the general idea, although this one contravenes the 1960s guidelines on color schemes! So does the one described in the aftermath of the birth of Prince George last month; the Guardian journalist Suzanne Moore mentioned the advice she had received in an ante-natal class from a French midwife who saw no problem with drinking wine with dinner, and compared it unfavourably with ‘the usual midwife, who had knitted a uterus. She apologised for the fact that it was navy blue as she had run out of pink wool. The plain knit was the uterus and the ribbed sock bit was the cervix. She then proceeded to push a tennis ball through it. That, she said, was “birth”‘ (my thanks to Catherine Ebenezer for this reference!). Blue is also the colour used for the ‘cabbage patch doll’ birth described and illustrated in a knitting forum discussion I found.

If you have any images of knitted wombs or information on how they have been, or still are, used around the world, I’d love to receive them.