Holly Tucker's Blog, page 60

February 8, 2014

The FBI investigated John Wilkes Booth — in the twentieth century?

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Admit it — if you’re following this blog, you believe that reading something especially intriguing can transport you through an unexpected window of history. I have that experience almost every time I browse FBI files on notable people and events.

Over the years, in response to Freedom of Information Act requests, the FBI has publicly released its files on a marvelous assortment of deceased people of celebrity, infamy, and importance. On my personal blog, I’ve written about the FBI file on the actress Carole Lombard and the agency’s investigation of the World War II air crash that killed her, as well as the file on architect Frank Lloyd Wright and his tangles with the government.

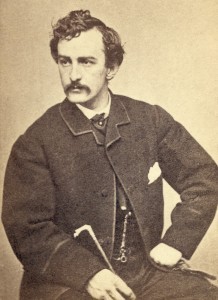

John Wilkes Booth

These files reveal as much about the worldview and techniques of the FBI as they do of the lives of their subjects.

I recently learned that John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated Abraham Lincoln in 1865, is the subject of another bulky FBI file, which is surprising because the FBI did not come into existence until six decades after Booth’s crime and death. What could possibly be in a file compiled so long after Lincoln’s assassination?

Did Booth elude capture?

The oldest pages of the file discuss the possibility that Booth escaped capture after he shot Lincoln. A Missourian who wrote to Bureau of Investigation director William J. Burns in 1922 claimed that his neighbor either was Booth or was in correspondence with the assassin. Burns replied skeptically that the agency was “inclined to believe official records in the case of John Wilkes Booth, and do[es] not feel that any investigation is necessary” to follow up.

Yet the following year, when another letter writer suggested that Burns read a book promoting a theory that Booth successfully fled his captors, the director seemed to have changed his mind. “The work contains very strong evidence in support of the old belief that Booth did escape and live many years after the assassination of President Lincoln,” Burns wrote. Was the agency’s director really among the believers? The file offers no further details.

The FBI gets the boot

The agency’s next encounter with Booth, as documented in the file, came in 1948, when the superintendent of the National Park Service’s U.S. capital properties sent the FBI an odd artifact in his charge: a boot that Booth was wearing when Dr. Samuel Mudd treated the left leg that the fugitive injured when he leapt from a theater balcony after shooting the president. Inside the boot was some faint writing. Could the FBI’s experts make out what it said?

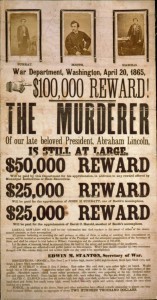

Booth’s wanted poster

The short answer, laid out in a report that director J. Edgar Hoover prefaced and signed, was that despite examining the boot’s interior with ultraviolet and infrared light, the FBI could not determine what the writing said beyond giving the name of the boot maker. The agency then returned the boot, and it currently is on display in the Ford’s Theatre Museum in Washington.

Diary of an Assassin

Most of the FBI’s file on Booth concerns an analysis of a pocket diary that Booth carried with him when he was tracked down and killed in 1865. In 1977, yet another administrator with the National Park Service’s National Capital properties asked the FBI to examine this little book “in order to rest any question about the possibility of invisible writing in the diary,” he wrote. (The concerns of the Park Service grew from the release that same year of The Lincoln Conspiracy, a film that alleged the secret involvement of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in the president’s death.) In addition, the Park Service hoped that the FBI would authenticate Booth’s handwriting by comparing the handscript in the diary with the handwriting in letters known to have been composed by Booth.

The FBI exposed the historical artifact to a variety of light frequencies, including ultraviolet, fluorescence with ultraviolet excitation, infrared, and x-ray. No hidden notations appeared. The agency judged the handwriting to be Booth’s and also confirmed that 27 sheets were missing from the diary. The absence of these pages had been known since 1867.

Unfortunately, Washington newspaper columnist Jack Anderson erroneously reported that the FBI was also analyzing these previously missing pages. The FBI denied having them, and the pages have never turned up. The diary itself, however, is currently exhibited at the Ford’s Theatre Museum.

That’s plenty of investigative intrigue for one file.

Further reading:

Anderson, Jack. “Lincoln Assassination Probed.” August 4, 1977.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. File on John Wilkes Booth.

February 6, 2014

The Big Race: Black Hills Geomyth

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

The Black Hills of South Dakota, sacred to the Lakota Sioux, are surrounded by the fossil deposits of masses of extinct creatures, from Cretaceous dinosaurs and marine reptiles that died out 65 million years ago to mammoths of the Pleistocene (1.7 to 10,000 years ago). The remarkable fossilized bones that continually weather out of the soil on the prairies around the Black Hills were observed by Native Americans over countless generations. Many oral traditions account for the strange remains of enormous creatures no longer seen alive.

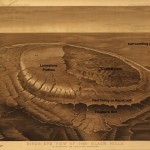

The Black Hills are also surrounded by a curious geological depression. The mountains are encircled by a broad valley of red siltstone that has eroded through the greenish Morrison Formation sediments just inside a steep ring of Cretaceous hogback ridges. This race-course-like landform rimmed with abundant fossil bone beds was noticed by the Lakota. Their myth of the “Big Race” explains the conspicuous geological feature and the layers of immense bones.

The myth begins in the “first sunrise of time,” before the existence of the Black Hills. The Earth summoned all the creatures to a great race to bring order into the violent, chaotic world. The land was covered with a seething crowd of animals. Their fate was at hand! They began to run in a great circle. The earth trembled under the impact of the running beasts and the sky darkened with circling birds. Around and around the racing animals sped. Many fell behind and the weaker ones were trampled, amid the din of groans, cries, roars, and screams. As they ran the earth beneath them began to sink crazily under their weight and a huge mound began to bulge in the center. The rising mountain burst and spewed fire and rock, which mixed with the clouds of dust thrown up by the desperate racers. The animals were struck down by flying rocks and smothered in ashes and debris; but some birds survived. Now, say the Lakotas, the remains of the great racecourse are still visible in the blood-red valley around the Black Hills and the bones of the long-ago beasts lie buried where they fell.

With surprising insight, the tale suggests a concept of extinction as a pitiless race for survival and pictures a catastrophic event in deep time to explain the geological and paleontological evidence. In fact, during the Cretaceous and Miocene (145 million to 5 million years ago), intense volcanic and tectonic forces violently uplifted a 7,500 foot dome of granite rock. Erosion ate away the ash and soil atop and around the dome, creating the race-course-like valley around the Black Hills.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Fossil Legends of the First Americans” (2005); “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011), and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

January 31, 2014

Building and rebuilding a dream in 17th century London: Shakespeare’s Globe

by Stephanie Cowell

Shakespeare’s Globe has been actually built three times…in 1599, in 1613 and after decades of struggle and huge architectural research, again on the south side of the Thames in 1995. But in 1599, it wasn’t really new because the actors salvaged the boards and galleries and perhaps even the hand-made nails from an earlier, much plainer theater (call the Theater) outside the northern walls of the city of London which was even then a very old city.

Shakespeare’s Globe has been actually built three times…in 1599, in 1613 and after decades of struggle and huge architectural research, again on the south side of the Thames in 1995. But in 1599, it wasn’t really new because the actors salvaged the boards and galleries and perhaps even the hand-made nails from an earlier, much plainer theater (call the Theater) outside the northern walls of the city of London which was even then a very old city.

The young men who built it were daring visionaries; they risked themselves financially in the days when an unpaid bill could often mean the stinking rat-filled pestilence of debtor’s prison. Theater companies bankrupt and disbanded; actors languished incarcerated until someone somehow paid their debt.

I have a great personal interest in the history of building the Globe; I always felt I somehow belonged back there. When I first traveled to London I crossed the river to Bankside and wandered among warehouses and other sad buildings until I found a single solitary plaque marking where the great Globe had stood in 1613. And I wrote two novels centering on it, and am in the midst of a third one so the Globe is very much in my heart.

This plaque was fixed to the wall of the brewery Barclay, Perkins & Co. in 1909.

Theater as we know it had only emerged perhaps twenty years before the foundation of the Globe was laid and there were a number of other roughly-raised playhouses (also used for bear baiting and other things) already in London. It was in approximately 1593 (give or take a year) that the gifted young poet Shakespeare from Stratford-on-Avon likely arrived in the city and began working as a reviser/enhancer of older rougher plays and gradually joined a group of actors who would work with him all his life. It is hard to recreate in our minds how young and excited they all were. Elizabeth the Queen, a woman not yet old who loved to dance the night away, loved theater and noblemen wishing to please her patronized acting troupes to play in the city and before her.

But the lease on the land of the original Theater had ended in 1598, and so the company of theater men (then called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, of which Shakespeare was a partial owner) rented land in the south side of the Thames, tore down the Theater, and carted whatever bricks or stone or gallery rail or wooden door they could over the frozen river and began to reshape it to the Globe.

The Globe opened in 1599. We have only a few rough pictures of the exterior and none of the interior, but following Elizabethan’s love of carved and painted and gilded wood, it must have been a beautiful sight. Legend has it that it opened with Shakespeare’s marvelously patriotic Henry V. Undoubtedly, Richard Burbage, one of the two most beloved actors on the Elizabethan stage, played Henry.

They had fourteen years of glory: during those years, Shakespeare wrote Julius Caesar, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and The Tempest, among many other plays. The theater changed plays regularly and ran them in repertory: some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries were Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, Dekker, Middleton, and so on.

Theater was a risky business I said: at any time the actors were concerned that the plague or the Puritans of any other piece of very back luck would shut them down. But it was fire which ended them in 1613. A cannon shot set off sparks in the thatched half-roof of the theater and though the Globe was quickly evacuated and no one was hurt (and they did not even have EXIT signs in those days!) the exquisite theater burned to the ground. Were Shakespeare’s original playscripts in there when it burned?

The sharers rebuilt it but the glory days had passed. Shakespeare shortly retired to Stratford and died there at the age of 52 in 1616. The era of the great outdoor theaters was coming to an end; though the second Globe lasted nearly thirty years, I find most scholars say little about it. Theater had moved indoors, to the Blackfriars Playhouse to name one theater.

Finding the remains of the Curtain Theater (Image credit: Museum of London Archaeology/AP Photo)

The new Globe lingered until 1642 when the Puritans seized Parliament, closed all theaters as being sinful and pulled it to the ground. It would not rise again for another three hundred and fifty years by another young actor with a vision. But that is another and even more wonderful story playing out even now.

You do not have to wander narrow, desolate alleys anymore on Bankside to find the Globe.

____________________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie is currently finishing two novels, one on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, and the second about the year Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

A Case of Spontaneous Human Combustion in 1731

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

[image error]

A young girl playing at being a nurse by rubbing “Vick” ointment on the chest of a doll. VapoRub contains camphor… Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

A strange case from Italy was reported in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1731 (vol. 1, June, p. 263): the body of a “Lady of Quality” was found burned to ashes in her bedchamber. Possibly, she had knocked over “a Lighted Lamp” during a fit. This account doesn’t seem particularly odd, but the brief report hinted at more interesting matters: a letter describing the death had been read before the Royal Society. And for years after, people speculated about how the woman’s body burned with no apparent external cause.

In 1736, The Gentleman’s Magazine (vol. 6, November, pp. 647-648) provided more detail. The sixty-two year old woman regularly applied spirit of camphor to prevent coughs and colds. After the fire, only the woman’s shins, feet, (three) finger bones and pile of ash remained. Although the bedroom hadn’t burned, it was covered in ashes that were “clammy, and stunk intolerable”. A “common fire can hardly reduce so large a body to Ashes”, the author argued, especially without burning the rest of the room.

The author proposed that the fire had been caused by the combination of spirit of camphor and fermentation of bodily juices. In the right circumstances, the first could cause heating and chafing, while the second could cause a flash of flame. The body was a bit like a powder magazine. When put into violent motion, gunpowder could blow up a magazine without any spark. According to the author, the human body had similar characteristics, with its fatty and saline particles. (After all, some people’s sweat even smelled like brimstone.) The result of mixing camphor and bodily fermentation? “Kindled at once in the Veins and the most minute Vessels of the Body”, the fire “consum’d [the body] in a Moment”.

Ten years later, the case appeared in The Gentleman’s Magazine (vol. 16, July 1746, pp. 368-371), this time as a summary of a recent article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (vol. 43, 1744-1745, pp. 447-465). Reverend Joseph Bianchini and his translator Paul Rolli named the victim, the Countess Cornelia Zangari & Bandi. The Countess felt “dull and heavy” before bed, but spent three hours talking with her maid and praying. The maid later discovered the remains, located four feet from the bed. The blankets and sheets on the bed were tossed aside “as when a Person rises up from it”. Close observation was crucial in Bianchini’s account; every detail had potential meaning.

Bianchini dismissed the supernatural, lightening flash (the “most common Opinion”), and spirit of camphor as causes. To support his analysis, Bianchini provided examples from medicine and chemistry. For example, since mixing two cold liquors together could produce flame and the human body was a mixture of acid and oil, “What Wonder then, if they may kindle?” It was common, too, for observers to see “Sparkles of Light” when women combed their hair. Normally, such sparkles were harmless, “but it is only for want of proper Fuel”. In one case, sparkles had burned the hair from a young man’s head.

Interior “sparkles” were even more dangerous. Not only had animal vivisection experiments shown that flames could be created inside bodies, but in several cases, people who drank too much had burned up from the inside. Women had it worst. “A feverish Fermentation, or a very strong Motion of combustible Matters” could easily arise in their wombs “with such an ingenious Strength that can reduce to Ashes the Bones”. One woman even had fire shooting out of her “privy Parts”!

Bianchini concluded that the Countess’ dullness came from “too much Heat concentrated in her Breast”, which prevented her from sweating normally. Her body was outside the bed because she had needed to cool down. Her internal heat also explained the burn pattern, with the fire starting in the torso, then burning upwards as fire usually does.

What interests me about this case is the way that people tried to make sense of it. Was it caused by a lamp, lightening, camphor oil or the body itself? The accounts also reveal a complicated chemical understanding of bodies, with their mix of fermentation and fire. The Countess’ death may have been unusual, but it was entirely explicable in natural terms.

But then so were the sparkles shooting out of women’s privy parts, which—unlike spontaneous human combustion—still seems a mystery to me.

January 18, 2014

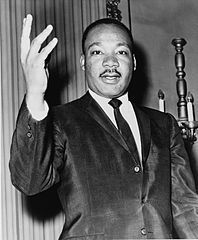

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mohandas Gandhi

by Pamela Toler

American civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. always claimed, “From my background I gained my regulating Christian ideals. From Gandhi, I learned my operational technique.”

The son and grandson of Baptist preachers in Atlanta, George, Martin Luther King went to Crozer Theological Seminary ready to fight for civil rights but full of doubts about the value of Christian love as a political strategy. He had adopted Reinhold Niebur’s philosophy that social evil was too intractable to be transformed by anything as simple as turning the other cheek.

A speech by Mordecai Johnson, then president of the largely Black Howard University, changed his mind. Johnson had just returned from India and had come back electrified by tales of Mahatma Gandhi’s successful struggle for Indian independence. Fascinated by Gandhi’s use of non-violent non-cooperation as a form of protest, the young theological student bought every book he could find on the Indian leader who had defeated the British empire with passive resistance and a spinning wheel. As he read, he became convinced that Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence was “the only logical approach to the solution of the race problem in the United States.”

King got his chance to apply Gandhi’s tactics for the first time in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. On December 1st, at the end of a long work day as a seamstress in a local department store, Rosa Parks was tired and her feet hurt. She refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery city bus to a white man and was arrested. King, 27 years old and the new pastor of Dexter Street Baptist Church, was thrust into a leadership role in the protest against bus segregation that became known as the Montgomery bus boycott.

Under King’s leadership, the black protest remained orderly and peaceful. For thirteen months, the 17,000 Black residents of Montgomery refused to use the public bus system, even if it meant walking to and from work, adding hours to already long working days.

King and 90 others were arrested and indicted for illegally conspiring to obstruct the operation of a business. Unlike Gandhi and his followers, who accepted arrest as a natural consequence of civil disobedience, King appealed his conviction, thereby keeping his cause in the public eye and gaining a national reputation as a civil rights leader in the process.

In 1959, King made a pilgrimage to India as the honored guest of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who had been Gandhi’s right hand man during the battle for independence from Britain. He returned to the Unites States confirmed in his conversion to non-violence and inspired to follow the example of Gandhi’s satyagraha campaigns, particularly his march to the sea.

King’s approach to non-violent non-cooperation was not identical to Gandhi’s. The Hindu ascetic and the Baptist minister agreed that non-violence succeeds by transforming the relationship between oppressor and oppressed, allowing the powerless to seize power through self-sacrifice. But where Gandhi preached that the practice of satyagraha was rooted in patient opposition, King believed in actively confronting his antagonist.

On January 24, 1998, a statue of Gandhi was unveiled at the Martin Luther King Historical Site in Atlanta, commemorating the philosophical tie between the two men.

January 15, 2014

Pinky Pinkerton’s Prayer

Here is my day. Every morning I wake at dawn. I sit Indian fashion on my cot and look out my window over Virginia City and a 100 Mile View. My window faces due East, straight down Mount Davidson. On a Clear Day I can see 100 miles. That reminds me that God sees a million million miles. I pray Dear Lord help me see the Unseen as well as the Seen. I see Sugar Loaf right smack dab there in the middle. It reminds me of Devil’s Peak which looks similar to Sugar Loaf but more pointy. That reminds me to Beware of Satan. I pray Dear Lord Deliver me from Evil. I see the Tailings from some of the mines and I hear the thump of the Quartz Stamp Mills. That reminds me what this place is all about: Mammon. It reminds me not to get entranced by the Pursuit of Riches but to try to Do Good Unto Others.

Here is my day. Every morning I wake at dawn. I sit Indian fashion on my cot and look out my window over Virginia City and a 100 Mile View. My window faces due East, straight down Mount Davidson. On a Clear Day I can see 100 miles. That reminds me that God sees a million million miles. I pray Dear Lord help me see the Unseen as well as the Seen. I see Sugar Loaf right smack dab there in the middle. It reminds me of Devil’s Peak which looks similar to Sugar Loaf but more pointy. That reminds me to Beware of Satan. I pray Dear Lord Deliver me from Evil. I see the Tailings from some of the mines and I hear the thump of the Quartz Stamp Mills. That reminds me what this place is all about: Mammon. It reminds me not to get entranced by the Pursuit of Riches but to try to Do Good Unto Others.

Here is my apparel. On my head I wear a rusty black slouch hat with a hawk feather in it. My mentor Poker Face Jace gave it to me. He told me he won it off an Indian. It smells faintly of bear fat which always makes me think of my original ma, a Lakota or “Sioux”. A party of Shoshone kilt her when I was ten. As I put that bear-fat-smelling-hat on my head I say Thank You Lord for my original Ma who taught me to Track and Shoot and Skin a Critter and also to Ride a Horse.

Next I don a faded miner’s shirt. Some people ask me why I am wearing a Pink shirt. I tell them it is not Pink; it is faded red. I like it because it is flannel and it is soft and warm. It goes with my nick-name: Pinky. It reminds me of my neighbour Isaiah Coffin. He has the Ambrotype & Photographic Gallery next door. He has a whole cupboard of clothes and he lets me borrow them for my Detective Disguises. I say Thank You Lord for Isaiah Coffin who lets me borrow his fancy clothes for my Detective Disguises.

Next I put on my buckskin trowsers. They have fringe like Indian buckskins but also pockets, which most Indian buckskins do not have. The reason my buckskin trowsers have pockets is because they were made special for me as a 12th birthday present by my dead foster Ma Evangeline. When I tug them on I think of her and I say Thank You Lord for Ma and Pa Jones, who taught me to Read & Write and also about You.

Next I lace up my moccasins. They are real soft and help me walk without making a sound. There is a spot of blood on them from where I got shot by a desperado called Whittlin Walt who is burning in Hellfire right about now. That Spot of Blood makes me think of Doc Pinkerton who dug out the ball. I say Thank You Lord for Doc Pinkerton who bears the same last name as me but is not related.

In my pocket I carry a Smith & Wesson’s Seven-shooter. It takes them new cartridges with the ball and powder all in a metal cylinder. I say Thank You Lord for Mr. Sam Clemens who gave me this firearm, even though he is a Lying Varmint. I promised my dying Foster Ma I would never Take a Man’s life but in a town like this where everybody carries a gun it is mighty comforting to have it there in my pocket.

Finally I dangle my Medicine Bag around my neck. Most Indian Braves dangle the Medicine Bag lower down, but that would impede me so I dangle mine around my neck, tucked inside my flannel shirt which is not Pink but faded red and goes with my nick-name: Pinky. In my Medicine Bag are some Lucifers, a flint knife, a gold Eagle and my Detective Button. It is a clew to the Identity of my real Pa. It says Pinkerton Rail Road Detective on it. It might have belonged to my Pa or it might not. I pray Thank You Lord for my Real Pa whether he was a bona fide Pinkerton or Not. If he is bona fide and not bogus, I would like to find him one day and work with him in his Detective Agency in Chicago. Please help me do this, Lord, and not get kilt. Amen.

The above prayer is fiction. It is one of the many passages I trimmed from of my P.K. Pinkerton Mysteries. It gives a taste of P.K.’s third adventure – P.K. Pinkerton and the Pistol-Packing Widows – which comes out soon. You can read a Kirkus review of it HERE.

January 14, 2014

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and the Destroying Angel

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu would not only introduce London to innoculation against smallpox, but also her series of ‘Turkish Embassy Letters’ make up the first secular work on the Muslim Orient by a Western woman.

Her life of adventure began when she escaped an arranged married with the astonishingly named Clotworthy Skeffington by marrying Edward Wortley Montagu. Mary bore him a son and her time in London was spent mixing in the highest circles, both social and intellectual as befitted the widely-educated daughter of a Duke. In the winter of 1715 all of this was to change: Lady Mary contracted smallpox. She survived, but she was ‘very severely markt’ in both appearance and temperament. Although she did not love Edward, she was was forever grateful that he did not cast aside once her beauty was eradicated.

In August of 1716, Edward was made Ambassador to Istanbul and they set out on a long journey via land and sea. In Vienna she was astonished to find that older women were very much in demand.

‘A Woman till 5 and thirty is look’d upon as a raw Girl and can possibly make no noise in the World till about forty. I cannot help lamenting upon this Occassion the pittifull case of so many good English Ladys long since retir’d to pruderie and rattafia, who, if their stars had luckily conducted them hither, would still shine in the first rank of Beautys’

Arriving in Sofia she and Edward went sightseeing, then Lady Mary set out alone on a little mission of her own. She hired a private coach, known as an araba and set out for a Turkish public bath, recording the experience in a letter to a friend dated 1st of April 1717 which opens, I am now got into a whole new World’. The world of the bagnio.

It was hard to tell the mistresses from their servants, Lady Mary remarked for they were all ‘in the state of nature, that is, in plain English, stark naked’. Having observed the conversation and seeing ‘some working, others drinking Coffee or sherbet’ Lady Mary came to the conclusion that, ‘In short, tis the Women’s coffee house, where all the news of the Town is told, Scandal invented etc.‘ Amongst her other letters from Turkey is another, also written on the 1st of April 1717. It tells of the inoculation of her son against smallpox, using an accepted Turkish method of ‘ripping’ a four or five veins with a large needle, applying pus from the sores of a smallpox victim, then covering the site with a ‘hollow bit of shell’ and binding them up. She reported to her husband, ‘The Boy was engrafted last Tuesday, and is at this time singing and playing and very impatient for his supper’. The success of this operation led her to ‘take pains to bring this usefull invention into fashion in England’.

Yet on her return to England she found both smallpox and arguments about its treatment raging. During the epidemic of 1719 which saw many of her friends and acquaintances die of the disease, she was remarkably silent. Then in the early part of 1721 it was so warm that roses bloomed in January and smallpox went ‘forth like a destroying Angel’. Lady Mary called upon Charles Maitland, an English doctor she had met in Turkey, to inoculate her daughter but he hesitated. It was one thing to perform the operation in Turkey, but another to do it in London. He made sure he had two witnesses from the Royal College of Physicians before performing the operation. One was James Keith, a friend of Maitland who had lost two of his sons to smallpox in 1717. After seeing the operation he immediately inoculated his remaining son.

London’s aristocracy began to visit Mary to see if they should engraft their own children. The visitors included Caroline, Princess of Wales who was then behind the testing of inoculation on condemned prisoners in Newgate. The experiment was a success, securing royal approval for smallpox inoculation, but the press did not take to it so kindly, or to Lady Mary. She was branded an ‘unnatural mother who had risked the lives of her own children’ and people began to ‘hoot’ at her in the street. Yet, the list of parents taking early action to protect their children is extensively drawn from Lady Mary’s own friends and acquaintances and the people who came to visit her children. She exploited the polite tea party circuit and took her children all over London to show that they had been unharmed by the operation.

The fact that she was well-known and her position in society contributed largely to the success of Maitland’s subsequent career in inoculation. Their pioneering work would lay the bedrock built upon by Edward Jenner later in the century. Jenner brought mass inoculation to England, but Lady Mary’s and Maitland’s early efforts laid the ground work, particularly amongst the charitable rich.

January 11, 2014

Liglig Kot – An Archeologist’s Dream in Nepal

by ELIZABETH GOLDSMITH (Wonders and Marvels Contributor) January 11, 2014

by Harvey Blustain, guest contributor

Is there anyone who doesn’t sometimes think, “If I could do it all again….”? If I could go back 40 years, I would focus my academic career on understanding Liglig Kot.

Is there anyone who doesn’t sometimes think, “If I could do it all again….”? If I could go back 40 years, I would focus my academic career on understanding Liglig Kot.

Liglig is a mountain in Gorkha District in central Nepal. Kot in Nepali means fort or citadel, usually situated on a hilltop. Mention Liglig to Nepalis and many will tell you about a race. Once a year, a long time ago, they will say, warriors of the Ghale tribe would run from the Chhepe River to the peak of Liglig. The winner was crowned king for that year. But in 1559, Drabya Shah from neighboring Lamjung conquered Liglig by attacking on the day of the race, when its warriors would be preoccupied. In 1768, his descendant Prithvinarayan Shah conquered Kathmandu, 60 miles to the southeast, establishing the dynasty that was to rule Nepal until the overthrow of the monarchy in 2008. The seed of modern Nepal was planted at Liglig Kot.

At 1,441 meters, Liglig Kot offers a commanding position over the strategic Marsyangdi River valley and a panoramic view along 150 kilometers of the Himalayan range. First-time visitors to the site, even jaded Nepalis, are knocked out by the vistas.

The remains of buildings extend for hundreds of yards along the north-south ridge. Some structures, including what local people believe to have been Drabya Shah’s palace, have walls and steps that make it possible to imagine what it looked like. Other large buildings are partially buried, with only massive ramparts protruding from the hillside. Unnatural mounds hint at other structures buried below. Moats and defensive walls encircle the site. It is hard to envision the total site because it has never been mapped or extensively surveyed.

When I did ethnographic fieldwork in the area in the 1970s, Liglig was barren of vegetation and only pilgrims visited the two small Siva temples. Since then, the communities surrounding Liglig Kot have taken an interest in the site with an eye toward tourism. The hilltop has been reforested. A local association has developed the site by building stairs, rest areas, latrines, picnic spots and other amenities. An annual race from the river to the kot is held to recreate the races of yore, complete with the crowning of the king for the year. Cultural festivals draw thousands of spectators.

When I did ethnographic fieldwork in the area in the 1970s, Liglig was barren of vegetation and only pilgrims visited the two small Siva temples. Since then, the communities surrounding Liglig Kot have taken an interest in the site with an eye toward tourism. The hilltop has been reforested. A local association has developed the site by building stairs, rest areas, latrines, picnic spots and other amenities. An annual race from the river to the kot is held to recreate the races of yore, complete with the crowning of the king for the year. Cultural festivals draw thousands of spectators.

Liglig is in danger of being loved to death. The forestation and construction are threatening the historical and structural integrity of the site. A cursory government Department of Archaeology survey recommended the development of a preservation plan that would balance the interests of researchers and development.

For the past 18 months, my archaeologist (retired) wife (on active duty) and I have been living on Liglig, working as volunteer English and computer teachers in the same village where I did my doctoral research. If we could go back in time, we would be strongly tempted to make a career out of the Liglig site. The government’s Department of Archaeology estimates that the site was likely occupied for 13 or 14 centuries. After the Shah conquest, Liglig was the center of a series of regional fortifications, most of which still dot the landscape. There has been relatively little archaeology done in the hills of Nepal, and there is much to understand. Liglig looms large in the local (and to some extent, national) historical and ethnic imagination. There are oral histories to be collected.

For the past 18 months, my archaeologist (retired) wife (on active duty) and I have been living on Liglig, working as volunteer English and computer teachers in the same village where I did my doctoral research. If we could go back in time, we would be strongly tempted to make a career out of the Liglig site. The government’s Department of Archaeology estimates that the site was likely occupied for 13 or 14 centuries. After the Shah conquest, Liglig was the center of a series of regional fortifications, most of which still dot the landscape. There has been relatively little archaeology done in the hills of Nepal, and there is much to understand. Liglig looms large in the local (and to some extent, national) historical and ethnic imagination. There are oral histories to be collected.

We are starting to put together a coalition of people interested in developing a preservation and development plan for Liglig. We will see how far it goes. But what Liglig also needs is an ardent young archaeologist willing to commit to years of really interesting work in a fabulous location. We’re too old.

____________________________

For further reading on life near Liglig and Harvey Blustain’s work in Nepal, see blog.blustain.net

January 9, 2014

Ancient libraries and their dangers

By Helen King

Galen was, to put it politely, a bit of a show-off. Since our main source for Galen is Galen himself, this can make it difficult to work out whether he was as great a physician as he makes out. I think the answer has to be that he was; his second-century AD career, started among the injured gladiators at his home town of Pergamum, peaked with him becoming one of the physicians to the emperor Marcus Aurelius and his family, so he certainly impressed the right people when he lived in the great metropolis of Rome.

But his prolific writings were also about constructing the right image, in an ancient example of ‘reputation management’. For example, he misses no opportunity to tell us just what care he took in understanding the works of his predecessors. Like any good researcher, he went back to the original sources, often comparing several versions of a text to work out what it probably said before it was copied by generations of scribes. This meant that he visited libraries to find old books. Ancient libraries have recently been the focus of a lot of scholarly research, and references to them lurk in the work of many Greek and Roman writers. The ancient Greek word was bibliothêka. Galen’s work contributes to this research. Among the many things we learn from incidental comments he makes about libraries is that people in antiquity could deface books, sometimes with dangerous consequences. For example, in his treatise On Antidotes (1.5) Galen tells us that the common system of using a Greek lettert to represent a number meant that it was far too easy to change a ‘five’ into a ‘nine’ (in Greek, an ‘e’ into a ‘th’). If the text was giving the ingredients for a drug recipe, the results could be very nasty indeed.

This even happened, Galen claims, in the Great Library of Alexandria, which allegedly had the interesting book acquisition policy of inspecting any books brought into the port, having them copied, and then returning the copy to the owner while putting the original into the library. In the treatise in which Galen talks about this – a commentary on the Hippocratic collection Epidemics Book 3 – Galen adds that these originals were then left in ‘heaps’ before being taken into the library itself. Anyone who uses libraries for research today will be familiar with that sinking feeling when the catalogue says ‘being processed’ or ‘being catalogued’; it seems this is not a new phenomenon. Galen is suggesting that even the Alexandrian library was not as well-organised as he himself was!

For Epidemics, Galen tells us that at Alexandria a man called Mnemon added in symbols to the text of the Hippocratic writer, using the same colour of ink and copying the handwriting (in forging, it’s important to remember the ink colour issue). Mnemon then claimed that these symbols were the secret key to understanding the text – and that only he knew what they meant! That has to be nearly as good a job of self-promotion as that done by Galen himself… So, Galen suggests, even books found in the Alexandrian library were not always to be trusted. Perhaps his underlying point is that the only source of reliable information is – Galen.

(PS and when I say ‘books’, think papyrus rolls, in most cases, as seen being unrolled in the image from a physician’s sarcophagus from Roman Ostia, kindly supplied for me by Barbara McManus)

Some reading on ancient libraries:

William A. Johnson and Holt N. Parker (eds), Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Jason König, Katerina Oikonomopolou and Greg Woolf, (eds.) Ancient Libraries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

January 8, 2014

Foreign Accent Syndrome: The History of an Odd Speech Disorder

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Every few months, the news media report on a strange malady: someone unexpectedly and unintentionally begins speaking in his or her native language with a foreign accent. This disorder occurs all over the globe; for instance, a Canadian acquires a Scottish accent, a Japanese develops a Korean accent, and an Indian speaks Hindi with a new American accent.

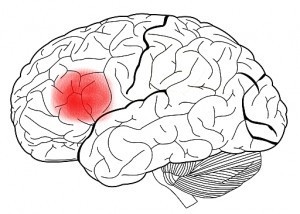

Broca’s area, a region of the brain associated with occurrences of foreign accent syndrome.

The problem is troubling and mysterious to its victims and their friends and families, but it almost always results from trauma to the brain. And the accents that victims suddenly acquire are not true foreign accents — patients rarely have any experience with or exposure to the foreign tongue that supposedly colors their speech — but represent speaking impairments that have appeared after damage to the central nervous system.

Foreign language syndrome first appeared in the medical literature in 1907 with French neurologist Pierre Marie’s description of a patient who began speaking French with an Alsatian accent after suffering a stroke. Twelve years later, neurologist Arnold Pick reported on a patient whose Czech language became flavored with a Polish accent after a stroke.

Over the years the reports continued to trickle in, including a heart-rending case from World War II. In 1941, during the German assault on Norway, a 30-year-old woman identified as Astrid L. was injured by an explosive shell. Left with a splintered skull and exposed brain, she eventually recovered except for the sudden appearance of a German-sounding lilt in her Norwegian speech. Astrid had never been to Germany or spent time with German speakers. But her countrymen assumed otherwise, and she was ostracized and sometimes refused service in shops.

Research by speech pathologists in the following decades uncovered fascinating information about foreign accent syndrome. Among native English speakers, the disorder affects their speech with German, Swedish, Norwegian, Spanish, Welsh, Italian, Irish, and New England overtones, among others. This YouTube video shows a speaker of Midwestern American English who began talking in British English after a stroke.

More than half of patients develop the syndrome after strokes, and others show their accents after head trauma and seizures. Most patients exhibit more common speech disorders such as apraxia and dysarthria in addition to their perceived accent. Prolongations in the pronunciation of vowels, slightly incorrect consonant sounds, the addition of vowel sounds between words, and the placement of unnatural syllabic stresses contribute to the illusion of a foreign accent. Often the appearance of the syndrome is connected with damage to the region of the brain known as Broca’s area. Treatment by a speech pathologist can improve the condition.

The next time you read a news account of someone’s sudden and involuntary use of a foreign accent, remember that neurologists and speech pathologists have long known the causes of this odd disorder, and that there’s nothing supernatural about it.

Further reading:

Aronson, Arnold E. and Bless, Diane M. Clinical Voice Disorders. Thieme, New York, 2009.

Gurd, J.M., Coleman, J.S., Costello, A., and Marshall, J.C. “Organic or Functional? A New Case of Foreign Accent Syndrome.” Cortex 37, 715-718. (2001)

Kurowski, K.M., Blumstein, S.E., Alexander, M. “The Foreign Accent Syndrome: A Reconsideration.” Brain and Language 54, 1-25. (1996)