Holly Tucker's Blog, page 58

May 6, 2014

“Dragons” of Ancient India

By Adrienne Mayor  (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

(Wonders and Marvels contributor)

“Dragons of enormous size and variety infest northern India,” concluded Apollonius of Tyana who traveled through the southern foothills of the Himalayas in the first century AD. “The countryside is full of them and no mountain ridge was without one.” Locals regaled visitors with fantastic tales of dragon hunting, using magic to lure them out of the earth in order to pry out the gems embedded in the dragons’ skulls.

Trophies of these quests were displayed in Paraka at the foot of a great mountain, “where a great many skulls of dragons were enshrined.” Ancient Paraka has never been identified, but linguistic clues suggest it was the ancient name for Peshawar. In later times a famous Buddhist holy place near Peshawar was known as “the shrine of the thousand heads.”

Apollonius traveled through the pass at Peshawar and southeast on a route that skirted the Siwalik Hills below the Himalayas. The barren foothills of the Siwalik range boast vast and rich fossil beds with rich remains of long-extinct bizarre creatures. On these eroding slopes and marshes from Kashmir to the banks of the Ganges, people in antiquity would have observed hosts of strange skeletons emerging from the earth: enormous crocodiles (20 feet long); tortoises the size of a Mini Cooper; shovel‑tusked gomphotheres, stegodons, and Elephas hysudricus with its bulging brow; chalicotheres and anthracotheres; the large giraffe Giraffokeryx; and the truly colossal Sivatherium (named after the Hindu god Siva), a moose‑like giraffe as big as an elephant and carrying massive antlers. It seems safe to guess that the “dragon” heads exhibited at Paraka included the skulls of some of these strange creatures from the Siwalik Hills.

Several details in the ancient descriptions catch the eye of a paleontologist. The dragons of the high ridges were said to be larger than dragons of the marshes, which had sharp twisted tusks. The marsh dragons fought elephants to the death; to find their entwined bodies was a great discovery. The dragons of the ridges were frightening: they had long necks and very prominent brows over deep, staring eye sockets. Huge crests grew on their heads, of moderate size on the young but reaching towering proportions on the adults. Men set out to hunt these creatures for the precious jewels—iridescent, “flashing out every hue”—inside their skulls.

People also claimed that the dragons made a great clashing noise and shook the earth when they burrowed in the ground, relating them to the severe earthquakes of the Siwaliks. The lowland dragons with distorted tusks jumbled with the remains of familiar elephants could have referred to fossil assemblages of early elephants with oddly formed jaws and tusks. Glowering brow ridges over deep‑sunk eyes would fit the appearance of the Giraffokeryx and Sivatherium giganteum. Both skulls have two pairs of prominent bony projections behind and over the eye sockets. The gigantic Sivatherium’s palmated antlers were extremely massive, while the longer‑necked Giraffokeryx’s four ossicones projected back laterally from its long, dragon-like skull.

What about the gems in the dragons’ skulls? The Indian lore about glittering gems prised out of “dragon” skulls appears to describe the sparkling crystals that can form on mineralized bones. Indeed, paleontologists confirm that impressive calcite and selenite crystals are very common in the fossilized bones of the Siwalik Hills.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011), “Fossil Legends of the First Americans,” (2005), and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

April 18, 2014

Book-hoarding, 10th Century Style

by Pamela Toler

Anyone who’s spent a significant amount of time with me in recent months, whether in real life or in some virtual space, has probably heard me bemoan the state of my office bookshelves. As the photo above attests, they overflow. Loaded two deep and stacked rather than shelved, there is still not enough room. Worse, for the first time in my life I am having trouble finding things. Twice in the last year I bought a book I already owned. Once because I couldn’t find the copy I was sure I had and needed right then. Once because I didn’t even realize I owned a copy. It makes me itchy.

Recently, a factoid has begun popping up in my universe that makes me feel even worse. According to Alberto Manguel, author of A History of Reading,

In the tenth century… the Grand Vizier of Persia, Abdul Kassem Ismael, in order not to part with his collection of 117,000 volumes when traveling, had them carried by a caravan of four hundred camels trained to walk in alphabetical order.

Manguel goes on to explain that the camel drivers effectively served as librarians, each responsible for retrieving volumes from his camel at the vizier’s command.

At first, I found the factoid charming: a lovely illustration of the importance of books in the early Islamic world. Then I felt a little jealous at the idea of owning 1117,000 books. Now I just feel inadequate at my inability to keep control over a couple of thousand books without the added complication of moving camels.

Something’s gonna change.

April 15, 2014

Where Warhol meets Venus

In 2010 a millionaire art collector bought a four story house in a pretty hill town on the French Rivera and made it into a boutique museum for his marvellous collection of Classical and modern art. This is the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins, or MACM for short.

In 2010 a millionaire art collector bought a four story house in a pretty hill town on the French Rivera and made it into a boutique museum for his marvellous collection of Classical and modern art. This is the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins, or MACM for short.

For any lover of ancient myths and ancient history, gods and heroes, Greece and Rome, Christian Levett’s collection is a delight. And all the more so because he has sprinkled in some later works of on Classical themes.

So you get a delicate Matisse charcoal of the Emperor Caracalla glowering at an ancient bust of himself, identical to the one Matisse was sketching.

A wax and insulin sculpture by Marc Quinn and a pair of Gormleys call to mind the plaster casts from Pompeii.

My favorite is a case devoted to Aphrodite, goddess of love. Ancient busts and torsos are set against the backdrop of a Warhol screenprint and flanked by an Yves Klein torso and Salvador Dali’s Venus as a Giraffe.

There are over 800 pieces in this museum and every one is a gem. Blue underlit marble stairs and a glass elevator give it a contemporary feel and its compact size makes it do-able in under two hours. Big info boards in French and (real) English plus plasma touch-screens in every room make it kid-friendly.

There are over 800 pieces in this museum and every one is a gem. Blue underlit marble stairs and a glass elevator give it a contemporary feel and its compact size makes it do-able in under two hours. Big info boards in French and (real) English plus plasma touch-screens in every room make it kid-friendly.

The museum has given a new lease of life to the village where Picasso spent his last few years (plenty of his stuff on show). After your visit, wander the snail spiral streets of the old town, a work of art in itself. And if you are there at lunchtime, the restaurant L’Amandier serves a wonderful lunch special for under 20 euros. You can dine with a view of the valley with its olive trees and red roofs.

The museum is a great supporter of local schools, like Mougins School, to which they give a prize for art once a year. Kids love visiting the museum. They like spotting the “odd one out” in a case of Greek helmets or votive figurines of Theseus. But children and adults alike will be stimulated by the juxtaposition of old art and new, all on the same wonderful theme of the Classical World and all it entails.

Caroline Lawrence writes history mystery books for kids and loves mixing old and new.

April 11, 2014

Medicine and Magic–or What I Did This Spring Semester

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders and Marvels)

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders and Marvels)

This year, I have been working closely with my colleague, Lynn Ramey to design a unified web portal (Imagining the Past) for students and faculty working on public-facing projects related to early cultural history. We are obviously still in the early stages–as evidenced by the infelicitous Latin-esque.

As part of this initiative, students in my Honors Seminar at Vanderbilt University: (“Leeches & Lancets: Early Medicine in Cultural Contexts“) created a website on the “darker side” of early-modern medicine, hosted on the Imagining the Past portal.* The goal was to make it attractive to a general audience, as well as those already knowledgeable about the subject.

I had no idea how the students would respond to the Medicine & Magic web experiment. But my adventurers rolled up their sleeves and really got to work. They even helped put together a shared Spotify playlist–the choices were interesting, we’ll just leave it at that.

Me? I can tell you it has been one the most invigorating teaching experiences in my career.

COURSE DESIGN

The course was divided into two parts. The first was structured as a traditional lecture/discussion course. We focused on the scientific, philosophical, religious, and gendered contexts in regard to:

the Rise of the Medical Professions

Anatomy & Physiology,

Therapeutics,

Surgery

Embryology & Childbirth

Epidemics,

Mental Illness

the Establishment of Hospitals

The second part of the course was taught as a COLLABORATIVE LAB, with a focus on creating well-researched and compelling web content on the history of medicine. Students worked in groups, both in- and outside class, on one of three different topics:

Fertility & Birth Control

Witchcraft & Magic

Poison

The course blog documents the core texts each group read in preparation for their work–as well as the guided, multi-step process they followed to create these websites. I was there–not as an intractable “expert” but instead as a guide. My job was to guide them toward appropriate resources and to ask the right questions at the right time–as well as help shape tasks and assignments to help them move their projects forward. But it was the students themselves who determined their own research question(s), reference corpus, approach, and presentation strategies.

CHALLENGES

The comment I heard students say most often? ”This is harder than I thought.” And it was.

For as much as we all have become consumers of web content, most people–including and especially college students–have had little opportunity to be producers of this content. From the start, their attention to audience and medium challenged them to dive into their research in different ways. It wasn’t a matter of making a linear argument that would be read by a single person (the professor). There was also no possibility of feigning “expertise” through page count (the longer the paper, ostensibly, the more “important” it is).

Students had to attend to many things at once: audience, content, voice, organization, judicious use of images, responsibility in research. Now, this is something we would hope they’d be doing in traditional assignments anyway.

But what gave students frank trepidation was the fact that the project was going to be public. They knew from the beginning that I would be tweeting their progress (@history_geek), and that I’d be reaching out to both fellow professors and general readers for commentary/suggestions on their work. **BETWEEN APRIL 12-19: Help me with this! Click here for a direct link to a short survey. You can also leave general comments here.**

We had some interesting discussions about why they could not assume an unlimited readerly attention span for online content. (Actually, why students assume that professors would have an unlimited attention span when it comes to traditional papers, and especially poorly written ones, is still a mystery to me. If only they knew.) They also had think through what it meant that, unlike in an academic papers, readers would not necessarily move through their site–their “argument”–linearly.

At one point in the process, I worried that the complexities of medium were eclipsing the content focus of the course: early-modern medicine. When I asked students about this, the answer was that they have never worked harder, probed deeper, and learned more about a topic. They had no choice. The new medium challenged them to think about research and writing in new ways.

TECH BASICS

A quick word about technology: It was gratifying to see that students needed instruction on Word Press basics (not one of my students had used Word Press before). But once they became acclimated to the basics, they were able to learn–on their own–how to do some ambitious and effective things.

It helps that the Imagining the Past portal itself was designed by a team of fantastic web designers (the same ones who designed and maintain Wonders & Marvels). It meant that the students had a consistent and stable space to work in. No wheels had be reinvented as they spent hours looking for just the right template, which may or may not be stable. As part of a collection of well-maintained and related sites, it also means that the chances are higher that work will be accessible for longer. This would not be the case if it sat as an ad hoc, unhosted site on WordPress.com, for example.

However, outside of the shared design and general infrastructure that is Imagining the Past portal, what you see in Magic & Medicine subsites was entirely created by students.

So, you know it’s been a good semester when you’ve worked very hard–but you’re also sad to see it end. I did. And I am. But I also delighted by the lasting, and public, evidence of all that we accomplished together.

—————-

*The students in Lynn’s Medieval French Studies have also been working on a site on Violence & Crusade, and I am also supervising several independent studies and graduate students working on sites related to “Crime & Passion” in early-modern France–again, hosted on the Imagining the Past portal. These sites are still in development, so stay tuned.

April 9, 2014

Death in Vienna and the City of Salt

By Helen King

Since I’ve been working in Vienna, I’ve become fascinated by the cemeteries: in particular, the Zentralfriedhof, which is so big that there are three tram stops along its perimeter and a special shuttle bus to get around inside, as it takes so long to walk from one end to the other.

I’ve only explored a few sections so far, including the Jewish part, where the tombs are sometimes spectacular and often very moving, because the history of this city includes the slaughter of the prominent Jewish community in 1938 when Hitler announced the annexation of Austria – the Anschluss. Outside this very special part, where what is striking is often precisely the blend of familiar, classical architecture with Hebrew inscriptions, I am fascinated by how different the styles of grave are from those in England with which I’m more familiar.

St Peter’s Cemetery, Salzburg

I was recently in Salzburg, Mozart’s birthplace, for a couple of days, and was struck by how the graves here were different again: grave markers were metal, not stone, and often very delicate, while the graves themselves were planted with masses of pansies. In 19th-century language of flowers, pansies meant ‘thoughts’, and so were appropriate for ‘remembrance’. Is that what they mean in Salzburg?

I also discovered that the city contains the grave of someone who, for a medical historian, means even more than Mozart: Paracelsus, who died there at the age of 48. Born Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, this controversial 16th-century figure has been hailed as the father of chemistry (by various chemistry textbooks), as the authentic voice of central European medicine (by Hitler) and as the founder of alternative medicine (by Prince Charles – or at least by his speech-writer).

Why the controversy? Paracelsus attacked the dominant Galenic tradition in medicine, and the universities which taught it. He is supposed to have said that his shoe-buckles knew more medicine than Galen did. He burned Galen’s books. He said that medicine should be learned not by studying the books of the ‘ancients’, but by travel – one country, one page of the book of  medicine. He hung out in bars, talking to ordinary people and finding out what they believed about medicine. He even abandoned the four humors – the constituent fluids of the body that had to stay in balance for health to be maintained – and instead talked about salt, sulfur and mercury. He was aware of the power of minerals to affect the body, having worked in mines himself.

medicine. He hung out in bars, talking to ordinary people and finding out what they believed about medicine. He even abandoned the four humors – the constituent fluids of the body that had to stay in balance for health to be maintained – and instead talked about salt, sulfur and mercury. He was aware of the power of minerals to affect the body, having worked in mines himself.

Not all of this monument in Salzburg (which incidentally refers to ‘Salz’, ‘salt’ – it’s a salt-mining area) is original; Paracelsus’ bones were moved when the church was repaired in 1752. What interested me most were the achievements of Paracelsus that were listed: ‘his art most wondrously healed even the most terrible wounds, leprosy, gout, dropsy, and other seemingly incurable diseases’. Just two years after the bones were moved, Arentius Lambrechts wrote in his treatise on gout: ‘It is inscribed on the Statue erected to the Memory of Paracelsus, that he could cure the Gout, by which, I suppose, is to be understood, he cured the Fit by ordering a good Diet, giving proper Anodynes, &c. But this does not root out the Seeds of the Disease; Nature left to herself would have performed thus much.’ Lambrechts is making Paracelsus sound like he followed the standard treatments but, in another tradition, also referred to in the inscription, Paracelsus was alchemist more than doctor.

In the past, alchemy was seen as a form of science. Even such an apparently ‘modern’ figure as Isaac Newton also wrote about a million words on his alchemical experiments. When Paracelsus talked about salt, sulfur and mercury, he saw these as three constituent parts of one individual: if you take wood and burn it, the part that burns is the sulfur, the smoke is the mercury, and the ash is the salt, and human beings, too, are composed of three different parts. Because little of his work was known until after his death, and he never wrote a structured book, modern scholars are still trying to work out what Paracelsus meant, and to decide whether he was a madman or a visionary!

April 8, 2014

Thomas Wiggins: A Nineteenth-Century Piano Savant

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

A 19th-century photograph of pianist Thomas Wiggins shows a stout young black man at rest on an overstuffed chair. His eyes are closed, and his hands curl delicately on his lap. He looks distinguished, confident, untroubled — and drowsy.

[image error]

Tom Wiggins photographed with his “Rain Storm” composition, c. 1861

It’s a shock, then, to learn that a reporter once called him “little more than an uncouth but inspired animal.” People called him many things: freak, prodigy, angel, imbecile. They rarely called him Thomas Wiggins. A half-century of concertgoers knew him only as Blind Tom.

Wiggins gained fame for his astonishing musical gifts — his perfect pitch, his ability to replicate at the keyboard anything he had ever heard, his quickness in recalling the 7,000 pieces in his repertoire — and for his alleged imbecility. (He was, in fact, possibly autistic.) Over the years, he became the world’s best known bearer of savant syndrome, a condition in which a mentally disabled person has a single outstanding skill. [I have previously written about Max Weisberg, another person with savant syndrome.]

Born blind in 1849 near Columbus, Georgia, he became a slave of General James Neil Bethune, a leading advocate of Southern succession. He could sing skillfully as a toddler and became a keyboard prodigy after the Bethune family bought a piano in the early 1850s. In 1857, Wiggins gave his first public recital in Columbus. The novelty of his performance — virtuoso playing by an apparently witless slave boy — led to engagements all over the country, from New Orleans to New York.

There was genius, however, in Wiggins’s keyboard interpretations and original compositions. In addition to well-known classical pieces, he played his own moving works, as well as pianistic impressions of bagpipes, a rainstorm, a sewing machine, a Civil War battle, and a brass band. Audiences eagerly awaited the segment of Wiggins’s program in which spectators could mount the stage and challenge him to reproduce anything that they played on the piano. One one occasion, he successfully played back a piece using both of his hands and his nose, just as the challenger had.

In 1864, General Bethune formed an alliance with Wiggins’s parents that for decades kept Wiggins in bondage, regardless of the Emancipation Proclamation. The contract awarded Bethune control of the pianist’s career and 90 percent of all concert receipts. As one of America’s most popular entertainers, Wiggins made Bethune a fortune.

Wiggins’s performing schedule remained full from the 1860s through the end of the century. “Tom has been seen probably more than any one living being,” wrote one biographer. During this time a custody battle flared in which Bethune’s daughter-in-law took control of his career. Willa Cather, haunted by one of his performances in Nebraska, used Wiggins as the model for the character Blind d’Arnault in My Ántonia. At the turn of the century, he ended his four decades of virtually uninterrupted touring with a stint in vaudeville.

In 1908, Wiggins suffered a stroke in Hoboken, New Jersey. He died at his piano.

More information:

John Davis Plays Blind Tom: The Eighth Wonder. Newport Classics audio CD, 2000.

O’Connell, Dierdre. The Ballad of Blind Tom, Slave Pianist. Overlook Press, 2009.

Southall, Geneva Handy. Blind Tom, The Black Pianist-Composer: Continually Enslaved. Scarecrow Press, 2002.

April 6, 2014

Who First Identified Elephant Fossils in America?

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

African slaves dug up some colossal teeth while working in a swampy field on Stono Plantation (North Carolina) in about 1725. The English botanist Mark Catesby visited Stono to view the amazing discovery. His hosts, the plantation owners, told him that the great molars were all that was left of a giant victim of Noah’s Flood from the Bible. At that time, that was the common explanation for all oversized fossils in Europe and the American colonies. But Catesby also questioned the slaves on the plantation. He wrote that the “Opinion of all the Negroes, native Africans, who saw the teeth” was unanimous. These were the molars of a familiar animal from their homeland. The slaves insisted that the big teeth belonged to an elephant. Catesby agreed with the slaves. Unlike the white masters, Catesby had examined some enormous molars of an African elephant in a London museum.

In Paris the famous French naturalist Georges Cuvier was intrigued by Catesby’s account. Cuvier was working on his new theory that huge fossils around the world belonged to prehistoric creatures, mammoths and mastodons. He was gathering evidence to show that these animals were the ancient ancestors of today’s elephants, and that they had all perished in a catastrophe ages ago. Cuvier was impressed, declaring that “les nègres” in America had correctly recognized a fossil elephant species before any European naturalist realized that extinct mammoths were related to living elephants.

The slaves at Stono were originally from Angola or the Congo, the habitat of living Loxodonta elephant species of Africa. The teeth they found at Stono belonged to a great Columbian mammoth that had died thousands of years earlier and was buried in the swamp. Mammoth teeth are flat with ridges (unlike the sharp, pointed teeth of mastodons) and they closely resemble the “grinders” of living African elephants. African people had often observed the skeletons, skulls, and teeth of elephants in Africa, and that experience allowed them to correctly identify the mammoth teeth in America. They must have been excited to find the remains of a familiar African animal so far from home.

About 50 years later, in 1782, workmen digging in salt marshes in Virginia unearthed teeth and “Bones of uncommon size.” Major Arthur Campbell sent these to Thomas Jefferson, with a letter saying that “Several sensible Africans have seen the tooth, particularly a fellow” owned by Jefferson’s neighbor. “All [the Africans] pronounced it an Elephant.” That means that the teeth belonged to a mammoth like at Stono, not to a mastodon. Once again, African slaves correctly identified the fossils that bewildered their white masters. Jefferson had a hard time accepting Cuvier’s idea that all that these behemoths were extinct. He wanted to believe that they still lived somewhere in the New World and hoped that Lewis and Clark would find herds of great American elephants grazing in the Northwest Territories.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Fossil Legends of the First Americans” (2005); “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011), and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 29, 2014

The Experience of False Pregnancies in Early Modern France

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

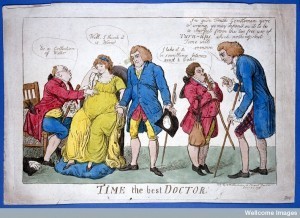

A group of physicians wrongly diagnosing the case of a pregnant woman. Coloured etching by I. Cruikshank, 1803. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

I was rustling through some old research notes on strange pregnancies when a detail in a case addressed to the Société Royale de Médecine from 1787 suddenly caught my eye. The case was one of unexpected pregnancy in which an unnamed forty-four year old woman (sterile for twenty-three years, one month and sixteen days of marriage) at long last gave birth.

Although I’ve looked at the case in terms of the experience of sterility, medical decision-making and community interest, I hadn’t paid much attention to the woman’s fears of a false pregnancy and her attempts to understand her symptoms.

Throughout her pregnancy, the woman had exhibited all the normal symptoms, but rather than celebrate, “she tormented herself with the fears” of false pregnancy, which seemed more likely given her history.

Having truly desired to have a child for so many years she had not dared to flatter herself with a true pregnancy and also feared the mockery.

She consulted with several local “people of the art [of medicine]”, who prescribed treatments to expel a false conception. Although her husband also believed that her symptoms were caused by a Mole (fleshy uterine growth), he asked Dr. Moulet of Caussade, Mantauban for advice. Moulet concluded that the woman was, indeed, pregnant.

This gave the couple hope, although they did not fully believe Moulet’s diagnosis. They prepared for childbirth, but in secret with the assistance of an accoucheur (man-midwife) from outside the community rather than a local midwife. If the the pregnancy proved false, the accoucheur (i.e. a man and one who was not local) would be less likely to gossip. At the centre of Moulet’s diagnosis was the issue of fetal movement. Moulet insisted that the movements in the woman’s belly indicated that she was definitively pregnant. But the woman was unconvinced—“one of her friends had informed [her] of such movement in a false pregnancy.”

This was when I did a double-take: do women with false pregnancies experience such movements? Or was this just a story about pregnancy that, as Moulet put it, served to “spread much timidity and alarm among the women”? I consulted Dr. Google and ended up down a very dark path of pseudocyesis: apparently the sensation of fetal movement in false pregnancies is very common!

I turned to well-known accoucheurs Mauriceau (The Diseases of Women with Child, and in Child-Bed, 1755 edition) and Dionis (A General Treatise of Midwifery, 1719 edition) to see what advice they offered. Mauriceau defined a false pregnancy as one

in which, instead of a Child, is ingendered nothing but Strange Matter, as Wind mixed with Waters, which are called Dropsies of the Womb, false conceptions, Moles, or Membranes full of Blood and corrupted Seed.

The cause of false conceptions, according to Mauriceau, was having too much sex. Dionis, however, believed that the cause came from either the male’s seed being too “effete” to fecundate the egg or the woman’s egg being too tough for the seed.

The symptoms of true and false pregnancies were, indeed, difficult to distinguish (whatever Moulet’s confidence). According to Mauriceau, women often believed they were pregnant if their courses stopped and they felt a bit “qualmish”, but this was an error—for false Conceptions cause almost the same Accidents as true; and cannot easily be distinguished but by the Consequences.”

Whereas Moulet insisted that the baby’s movement was definitive, Mauriceau cautioned: “Be careful not to be deceived by what we feel stir in the Womb, forasmuch as the Infant of it self hath a total [full body] and a partial [only limbs] Motion.” What made it most confusing that was “fits of the Mother and Moles have by accident a total kind of Motion, but never partial.” For example, a Mole always fell heavily onto whichever side a woman was lying on. The only way to know for sure was by physicially examining the woman to see whether the cervix was closed and the womb distended.

In addition, Dionis believed that the woman’s age was important; women “are most subject to these false Big Bellies from the thirty fifth to the fortieth Year of their Age.” At this age, women had less regular courses and the build up of too much blood or the badness of retained blood would easily lead to imperfect conceptions.

Given her age and the ambiguity of pregnancy symptoms, no wonder Moulet’s patient remained uncertain of her pregnancy until the end!

March 20, 2014

YA Historical Fiction and the Classroom—And a Giveaway!

by Tracy Barrett (W & M Contributor)

One of an author’s many jobs is helping to get her books into readers’ hands. Those of us who write for children and adolescents have to appeal to several groups in order for that to happen—not only our intended audience, but adults as well: reviewers, parents, and teachers and librarians. Rather than looking at these gatekeepers as people as obstacles we have to overcome, I choose to look on them as my allies.

There’s not much I can do to reach reviewers. My publisher is responsible for getting ARCs* to them and I just have to wait for the response. I don’t have much opportunity to reach parents, either, except in small numbers at school appearances and signing.

But teachers and librarians—ah, there we go. They’re great friends of writers in general and can really help writers of historical fiction. While readers of historical fiction are usually passionate, even fanatical, about the genre, there aren’t that many of them. Without educators to put my books into the hands of those few but passionate fans, some of them will miss what I’ve written.

Of course, meeting these people is crucial. I regularly address groups of teachers, librarians, and specialists locally and throughout the country (and even in Europe, occasionally).

And I have to work within their reality. They’re strapped for time, so I help them write grants to fund an author visit and provide quizzes, exercises, and writing prompts on the For Teachers page of my web site. They don’t have much funding, so I point them to sources such as SCBWI’s Amber Brown Grant.

Once I convince my listeners of the benefit of encouraging their students to read a story that makes the long-dead figures they’re studying come alive, I’m most of the way there. But the job isn’t done if I want the kids in their care to read what I’ve written.

Teachers have very limited time, so I make it as easy as possible for them to use my books as part of a curriculum, either as outside reading or as extra reading. For example, I let them know that they don’t have to come up with exercises, writing prompts, quizzes, paper topics, etc., since I’ve created those for most of my books. (See my For Teachers page.) I find justification that my school visit will be instructional in the Common Core principles and in the state standards for the grade level I’m addressing.

Most of all, I’ve learned to listen to teachers and librarians. They love books and authors, and they can be our greatest allies. Several teachers told me that they would like to use my King of Ithaka to supplement class study of the Odyssey but the hardcover version was too expensive. So I approached my publisher and asked if they had plans to issue it in paperback. They didn’t, so I asked them to reconsider. And I asked them again. And finally, they agreed. Here it is!

It went on sale just two days ago, and to celebrate, I’d like to give a copy to a classroom teacher or librarian along with a free Skype visit. If you’re not a teacher but would like to enter, please do! You can give the book and Skype visit to the educator of your choice. All you have to do is enter a comment here in the next week (by March 27). I’ll choose one commenter at random.

*ARC: Advance Reading Copy. These are low-cost versions of the book that are sent to reviewers and bloggers ahead of publication.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently

Dark of the Moon

(Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin TEEN in June, 2014 is

The Stepsister’s Tale

. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently

Dark of the Moon

(Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin TEEN in June, 2014 is

The Stepsister’s Tale

. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

March 18, 2014

If You Love Jane Austen….

by Pamela Toler

Allow me to introduce Emily Eden–aristocratic spinster, political hostess, accomplished painter, and talented novelist.

I first discovered Emily Eden through her connection to India. Her brother George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, was appointed Governor-General of India in 1835. Emily accompanied him to India and served as his Burra Lady Sahib (the rough equivalent of an American First Lady) for the six years of his tenure.*

For the first twenty months of their stay, the Edens stayed in Calcutta, then the capital of British India. Emily was miserable. She didn’t like India–or more accurately, she didn’t like Anglo-Indian society in Calcutta, which she viewed with all the snobbery of an aristocrat accustomed to moving in the highest political circles. She felt herself exiled in what she described as a “second-rate society”. Things got better when Emily accompanied her brother on a two-year-long tour of the country. Her diary and letters, published in 1866 as Up The Country, offer a witty and carefully observed account of a specific moment in Indian history as seen from a very specific viewpoint. I read Up The Country for my academic work, but found it an absolute pleasure.

Several years later, I was delighted to stumble across two novels by Eden: The Semi-Attached Couple and The Semi-Detached House. Although Eden’s experience of the world was much broader than Austen’s, their novels are similar in scale. Instead of writing about her experience of India or political London, Eden wrote comedies of manners that drew on the same social mores and concerns as Austen’s novels, though both their author and her characters live higher up the social ladder than Austen. Eden observes her own society with the same sharp-eyed wit that she brought to India.

I don’t claim that Eden is Austen’s equal. (No one who writes the kind of thing Austen writes comes even close.) Her novels are a good read in the same general vein by an author with a distinctive voice. Her writing on India is even better.

* Lord Auckland doesn’t fare well in history He is best remembered for the paranoid decisions that resulted in the debacle of the First Anglo-Afghan War.