Holly Tucker's Blog, page 57

June 2, 2014

Breastfeeding… the Grandchildren? Wondrous Early Modern Tales of Aged Women

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

A poor woman in a dingy attic, surrounded by her children, one of whom she is breast-feeding. Engraving by N. de Larmessin III after J. Pierre. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Whenever a hungry infant grandchild rooted for my mother’s breast, she would joke that “there isn’t any milk left in this old cow” and passed the child back to my sister for feeding. She clearly just wasn’t trying hard enough. After all, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society printed cases of aged women who found themselves able to breastfeed their grandchildren…

In 1674, “A Person of Great Veracity” recounted two cases of breastfeeding grandmothers, one of which happened within his own family. Two months previously, the family had hired a nurse for their little girl, which entailed the nurse weaning her own son. But the boy kept “sucking the Breasts of his Grand-mother”, which caused “such a commotion in her, that abundance of milk run to her Breasts for a sufficient nourishment”.

To provide added authority, the author referred to a similar case from Vienna that had been described by Dutch physician Diemerbroeck. A poor woman gave birth to a healthy boy, but both the father and she died soon after. The sixty-six year old grandmother, Joanna Vuyltuyt, took in the child, but had no money to hire a nurse. She desperately attempted to feed the baby herself. “From that old woman’s strong imagination and vehement desire to give suck to this child”, she soon produced a good quantity of milk, and “all that saw it much wondered at” it.

Diemerbroeck and the “Person of Great Veracity” each provided a medical explanation for the cases: a physical reaction to stimulation or imagination and will. Both explanations made sense within the early modern medical world, depending on whether one saw the body as a machine filled with pumps and valves or a body that was intricately connected to one’s mind. There was a third reaction, however: wonder. This was, after all, no ordinary bodily behaviour.

Thomas Stack submitted a letter to the Phil. Trans. in 1739 about a sixty-eight year old grandmother “Who Gave Suck to Two of Her Grand-children”. Stack first heard of the case from “a gentleman of credit” who offered to take him to the breastfeeding granny of Tottenham Court Road (Elizabeth Brian) in London. The plan, this time, was to “discover some Fallacy in the Affair”; wonders were treated much more sceptically by 1739 than they had been sixty years earlier. Stack’s first impressions of the story’s plausibility were favorable: “Her Breasts were full, fair, and void of Wrinkles”, although the woman otherwise looked as old as might be expected for one who had spent the “last Half of her past life in Labour, troubles, and other concomitants of Poverty”.

Mrs Brian had not borne a child for twenty years, but had been breastfeeding her grandchildren for the last four years. Again, this was a case of financial and physical necessity. The mother had left the first infant with her mother and was “likely to be a considerable time absent” (presumably for employment). The little girl did not take to the forced weaning well, though, and was “froward for want of the Breast”. To keep the child quiet, the grandmother let her suckle and after several occasions of this, Mrs Brian’s son noticed that the child seemed to be swallowing something. The son “begg’d leave of his mother to try if she had not milk”. The son “drew Milk from that same Breast from which he had been wean’d above Twenty years”.[1] From that point on, Mrs Brian breastfed the child and was so successful that the daughter decided to have another baby, given that she had such a capable nurse.

Stack examined both girls, noting that they were healthy and sprightly. He also observed the youngest feed to make certain that the baby was truly drawing out milk. Stack did not offer any medical conclusions, but did determine that “the poor Woman seems perfectly honest and artless”. Mrs Brian, however, had an explanation: “She very religiously throws the whole upon a miracle”. And so it must have seemed.

Unusual cases, certainly, but not impossible. Modern medicine has found that milk can be produced by men and non-childbearing women, whether as a bodily malfunction (over-production of prolactin) or–most relevant in each of the early modern cases–as an adaptive measure to cope with maternal loss. In such cases, extreme psychological stress and stimulation of the nipple can result in the ability to breastfeed.[2] We might now have scientific studies, but that explanation sounds rather similar to the ones provided by Diemerbroeck and “A Person of Great Veracity” back in 1674.

In any case, despite my mother’s insistence, there could still be milk left in the old cow (sorry, Mom!)—but thank goodness it was never necessary.

[1] Early modern people were much less troubled by breast-feeding, even for adults. Very ill people might be breast-fed, while squirting breast-milk directly into the eye was often used for eye problems.

[2] Sobrinho, Luis Gonçalves. “Prolactin, Psychological Stress and Environment in Humans: Adaptation and Maladaption”. Pituitary 6 (2003): 35-39.

Naum Kotik and the Brain Ray

In 1903 the French physicist Rene Blondlot announced that he had discovered the n-ray, a form of invisible electro-magnetic radiation named in honor of the University of Nancy, where he served as a member of the faculty. Two years later his results were negated by an American physicist, but not before twenty prominent French scientists confirmed the existence of the non-existent n-ray. By 1907, despite overwhelming evidence that n-rays did not exist, more than 150 scientists in over 300  published articles had claimed to be able to detect N-rays emitted from a variety of objects, including the human body and mind. The Russian scientist Naum Kotik was one who refused to give up on the idea of the n-ray; in 1905 he tried to duplicate the laboratory experiments of parapsychologist Paul Joire, who claimed to have detected nervous energy emanating from the human body by means of the sthenometer, an instrument of his own invention, a type of biometer in which a needle was balanced on a pivot in a glass case. Kotik writes that his own attempts to duplicate Joire’s experiments at the psychiatric clinic of Moscow University were inconclusive, but only because he had abandoned his work there to take part in the failed Russian revolution of 1905. Despite all assertions to the contrary, Kotik expresses confidence in the existence of n-rays and in his own ability to prove in time that they emanate from the human brain.

published articles had claimed to be able to detect N-rays emitted from a variety of objects, including the human body and mind. The Russian scientist Naum Kotik was one who refused to give up on the idea of the n-ray; in 1905 he tried to duplicate the laboratory experiments of parapsychologist Paul Joire, who claimed to have detected nervous energy emanating from the human body by means of the sthenometer, an instrument of his own invention, a type of biometer in which a needle was balanced on a pivot in a glass case. Kotik writes that his own attempts to duplicate Joire’s experiments at the psychiatric clinic of Moscow University were inconclusive, but only because he had abandoned his work there to take part in the failed Russian revolution of 1905. Despite all assertions to the contrary, Kotik expresses confidence in the existence of n-rays and in his own ability to prove in time that they emanate from the human brain.

In a 1904 article entitled “Mind-reading and N-rays,” Kotik describes his experiments in Odessa with a young psychic: “The transmission of thoughts is accomplished by means of the n-ray, which arises at the moment of thought in the brain of one person and has the capability to awaken the brain centers of another person and call up in that person a corresponding representation.” Kotik compares his work on the n-ray, a “special ray energy” that has both “psychological” and “physical” properties, to the recent discovery of electromagnetic waves by Herz, x-rays by Roentgen, and radiation by Marie Curie and Henri Becquerel, in whose laboratory Kotik had worked. According to Kotik, his scientific experiments proved that the human mind works in the same way as any radioactive substance, and that n-rays provide a scientific explanation for all kinds of paranormal phenomena from automatic writing to the practice of reading letters through sealed envelopes.

In addition to transmitting n-rays via the subconscious, or “lower mind,” Kotik argued that they could also be communicated intentionally, which explained the work of hypnotists, since psycho-physical energy “flows from a body with a stronger psychic charge to a body with a weaker psychic charge.” When we speak a word, most of the psycho-physical energy is used up, passing into physical movement of the lips, tongue, vocal cords. Unspoken words on the other hand have a different energy flow: “When we just think words, then the energy produced remains free and becomes concentrated into N-rays (the law of the conservation of energy).” Most of Kotik’s experiments centered on testing to see if psychics, whose minds he believed were specially tuned to n-rays, could detect the radiation that he believed came from human thought.

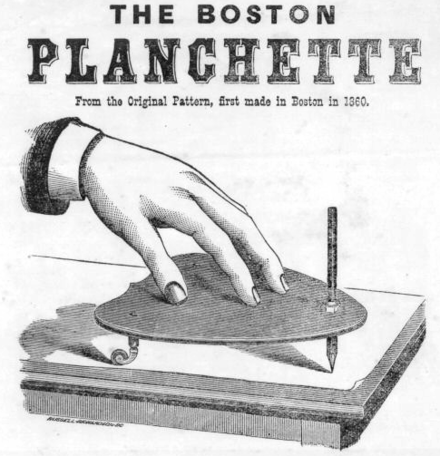

In his 1907 Emanation of Psycho-physical Energy: Experimental Investigation of the Phenomena of Mediumism,  Clairvoyance, and Psychic Suggestion in Connection with the Question of the Radioactivity of the Brain, Kotik describes several experiments with a young psychic named Lydia. One of these involved automatic writing, a common paranormal practice at the turn of the century. Lydia would rest her hand on a planchette, a triangular elevated piece of cardboard equipped with a pencil, and Kotik would look intently at colored postcards while they conversed on an unrelated topic. According to Kotik Lydia’s attention remained wholly on their conversation, yet her hand moved intermittently, seemingly of its own accord, writing descriptions of the postcards in surprising detail. He concludes that while their “upper minds” were occupied with conversation, their “lower minds” were communicating via n-rays, in what Kotik calls a “thought telegram.” If wireless telegraphy could send messages across oceans with electromagnetic rays, then Kotik believed that the same feat could certainly be accomplished at a shorter distance by the electromagnetic rays of the human mind.

Clairvoyance, and Psychic Suggestion in Connection with the Question of the Radioactivity of the Brain, Kotik describes several experiments with a young psychic named Lydia. One of these involved automatic writing, a common paranormal practice at the turn of the century. Lydia would rest her hand on a planchette, a triangular elevated piece of cardboard equipped with a pencil, and Kotik would look intently at colored postcards while they conversed on an unrelated topic. According to Kotik Lydia’s attention remained wholly on their conversation, yet her hand moved intermittently, seemingly of its own accord, writing descriptions of the postcards in surprising detail. He concludes that while their “upper minds” were occupied with conversation, their “lower minds” were communicating via n-rays, in what Kotik calls a “thought telegram.” If wireless telegraphy could send messages across oceans with electromagnetic rays, then Kotik believed that the same feat could certainly be accomplished at a shorter distance by the electromagnetic rays of the human mind.

In a second experiment, by placing her hand on a sealed opaque envelope Lydia “read” the description contained within. Kotik argued that the radiation left on paper by the writer’s n-rays had passed through the envelope and up her arm.  Hypothesizing that psycho-physical energy would work like electromagnetic energy, Kotik set up a second experiment to find out if metal would conduct it. Lydia held one end of a copper pipe that passed through a small hole in a closed door. The other end rested on a sealed envelope. As he predicted, metal readily conducted the psycho-physical energy remaining on the paper. In fact, the radiation that emanated from the human mind was so strong that it could override the written words to communicate an unrelated message sent by the writer’s subconscious mind. For example, when Kotik requested that a preoccupied businessman write similar descriptions of postcards, Lydia could not describe the pictures he wrote about but instead described the financial matters that emanated from his “lower mind.” Kotik speculated that the thoughts directed at the paper were far more powerful than the words actually written. As a test he tried the experiment with blank paper, and asserts that the radiation left by intently thinking at the paper was just as effective as writing on it.

Hypothesizing that psycho-physical energy would work like electromagnetic energy, Kotik set up a second experiment to find out if metal would conduct it. Lydia held one end of a copper pipe that passed through a small hole in a closed door. The other end rested on a sealed envelope. As he predicted, metal readily conducted the psycho-physical energy remaining on the paper. In fact, the radiation that emanated from the human mind was so strong that it could override the written words to communicate an unrelated message sent by the writer’s subconscious mind. For example, when Kotik requested that a preoccupied businessman write similar descriptions of postcards, Lydia could not describe the pictures he wrote about but instead described the financial matters that emanated from his “lower mind.” Kotik speculated that the thoughts directed at the paper were far more powerful than the words actually written. As a test he tried the experiment with blank paper, and asserts that the radiation left by intently thinking at the paper was just as effective as writing on it.

Oh, if only it were true–writers everywhere would be so much more productive!

Cleopatra and Antony Go Fishing

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Cleopatra had a thousand ways of flattering Mark Antony, remarked Plutarch in his biography of the Egyptian queen’s Roman lover. With a raptor’s vigilance she monitored Antony’s moods day and night and was always ready with some new diversion or novel adventure to distract and charm him. Cleopatra was his drinking buddy and his gambling partner at dice; she accompanied him whenever he exercised, hunted, and practiced with his weapons. Dressed in disreputable disguises, the couple enjoyed rambling recklessly around town in the middle of the night like hooligans, pounding on people’s doors and shouting insults at their windows.

One day Cleopatra took Antony fishing on the Nile on her barge, accompanied by a flotilla of smaller fishing boats. Everyone pulled up a good number of Nile perch on their lines that day except Anthony. Feeling humiliated in front of his mistress and determined not to be skunked again, Anthony devised a plan. The next day he secretly paid several fishermen to dive underwater and place their own freshly caught fish on his hook. Over the next hour or so Antony drew up fish after fish. The Egyptians marveled at the heap of silvery blue fish on the deck and wondered at the speed at which the perch were taking the Roman’s bait.

Cleopatra immediately figured out Antony’s ruse but she feigned great admiration, crowing over what a natural fisherman he was. Boasting that his haul would be even more impressive tomorrow, she invited everyone back for another day of fishing.

The next day Cleopatra arranged her own trick. As soon as Anthony let down his line, she had her servants “dive down and affix a large salted fish from the Black Sea on Anthony’s hook.” Feeling the tugging on the line Anthony quickly landed the heavy fish. As everyone stared at his catch it was instantly obvious that he’d pulled up a big fish that was not only long dead but definitely not a denizen of the Nile. As Plutarch comments, you can imagine the guffaws and hoots that ensued. Cleopatra, giggling mischievously, diverted Antony’s irritation with flattery: “Better to leave fishing to us poor Egyptians—your game is conquering kingdoms.”

Nile perch (Lates niloticus) have a high fat content so they were preserved by smoking instead of drying and salting. Black Sea fisheries exported vast stores of salted fish around the ancient Mediterranean world. The large salt-cured fish from the Black Sea “caught” by Antony in the Nile was most likely a tuna. Great schools of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) used to dominate the Black Sea but went extinct there in antiquity; today they are endangered in the Atlantic.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011), “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (fall 2014).

May 24, 2014

In Pursuit of Haydn’s Head

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

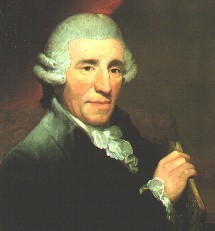

Today people admire the Austrian-born composer Franz Joseph Haydn for many reasons: his output of 107 symphonies, many of them jolly and playful; his countless other compositions for all kinds of instrumental and vocal combinations; his friendship with Mozart and his encouragement of the young Beethoven; and his modest bearing in an age when other musical celebrities had egos far bigger than their talents.

Franz Joseph Haydn, alive and intact

During the decades after his death in 1809, however, the notorious theft and lengthy disappearance of the composer’s head at times overshadowed Haydn’s accomplishments. For nearly 150 years, Haydn’s corpse and skeleton remained headless while various parties — including members of a rogue gang of phrenologists and some of Europe’s most respected educational and musical institutions — bickered over the ownership of the skull.

The surprising tale of Haydn’s wandering head began just a week after the maestro’s death at the age of 77. Due to the Napoleonic wars that still raged in Austria, Haydn’s royal patron and employer, Nikolaus II, Prince Esterhazy, temporarily buried the composer’s body not in the still-contested land of the Esterhazy estate outside Vienna, but in Hundesturm Cemetery, within the city limits. Vienna was rife with phrenologists — people who believed that the shape and bumps of a skull can reveal insights into the intelligence and character of its owner. Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a former secretary to Prince Esterhazy, followed this dubious science, and he conspired with a fellow enthusiast, a prison official named Johann Peter, to take possession of Haydn’s head. They hoped to study the skull and thus learn the secrets of Haydn’s musical genius.

Rosenbaum and Peter bribed a cemetery caretaker to break open Haydn’s casket and cut off the head. In the dead of night, the caretaker did so and delivered a wrapped bundle to the anxious conspirators. Rosenbaum could not resist taking a peek into the bundle as he took his carriage home. He saw that the enterprise had been successful, but had mixed feelings. “I had to vomit — the stench had overcome me,” he later wrote in his journal. “The head was already quite green, but still completely recognizable.” Rosenbaum wasted no time in having the head dissected, de-brained, bleached, and macerated at Vienna General Hospital, and he later designed a specially draped display case for the skull, which received a place of honor in his home.

And there Haydn’s head rested for the next eleven years. If Rosenbaum and Peter learned the secrets of Haydn’s genius, they never shared them with anyone. In 1820, however, Prince Esterhazy belatedly decided to transfer Haydn’s mausoleum to its permanent place in the Eisenstadt City Church on his own estate outside Vienna. In the course of moving the body, Esterhazy’s officers found the head missing. Only a wig occupied the space above the shoulders. Outraged, Prince Esterhazy notified the police, who uncovered rumors of Peter’s involvement in the theft.

Peter squealed on Rosenbaum. The police searched Rosenbaum’s quarters, but his wife feigned illness and hid Haydn’s skull in bed with her. Meanwhile, Rosenbaum surrendered another skull from his collection, and this wrong part joined Haydn’s body and was buried with him in Eisenstadt City Church.

For years, Rosenbaum kept sole possession of what was left of Franz Josef Haydn’s head. But when Rosenbaum died in 1829 (and it is not known whether he took special measures to keep his own skull from the prying fingers of fanatical phrenologists), he bequeathed Haydn’s skull to Peter — with the proviso that Peter must in turn will the skull to Vienna’s Society of the Friends of Music, an archive and professional organization for musicians. When Peter passed on, he had made good on this commitment, but unfortunately he had loaned the skull to another phrenologist, a Dr. Karl Haller, who did not respect Peter’s will and gave Haydn’s head to an anatomist, Professor Karl Freiherr von Rokitansky of the University of Vienna.

Years passed, and the skull remained at the University even though the Society of the Friends of Music knew of Peter’s bequest and tried to gain possession of the boney prize. Finally the Society filed suit against the University. The Esterhazy descendants, astonished to learn that Haydn’s body has been attached to the wrong head, filed their own suit to seize the skull. In 1895 — 86 years after Haydn’s death — the legal wrangle concluded when an Austrian court awarded the skull to the Society of the Friends of Music. For several generations, the skull sat on a pedestal in the Society’s building in Vienna.

In 1932, the bicentennial of Haydn’s birth, the Esterhazy family made another attempt to restore the skull to its family estate, which now lay within the redrawn borders of Hungary. Duke Paul Esterhazy built a fancy new mausoleum for Haydn at the Eisenstadt Hill Church. The Society of the Friends of Music offered to sell the skull to Esterhazy, but the hardships of the Great Depression had hit even noble families. The price for the skull was too high.

During World War II, Haydn’s head remained on its pedestal in Vienna. At the end of the war, however, the Society of the Friends of Music had a change of heart. It offered to give the skull to the Esterhazy Estate.

On May 30, 1954, the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir celebrated the upcoming rejoining of Haydn’s skull with the rest of his skeleton with a performance of the composer’s oratorio The Creation. On July 5, the skull was blessed by Cardinal Theodor Innitzer; it was then carried in a small leather casket from the Society’s building in a hearse on a bed of ferns and flowers. The hearse transported the skull through the town of Rohrau, Haydn’s birthplace, where roadside musicians played the composer’s Emperor Quartet. Then the skull arrived at the Esterhazy castle in Eisenstadt. Along with the rest of Haydn’s bones, the skull was set within a new copper coffin, the old coffin having long since deteriorated. Finally intact, Haydn’s remains were laid to rest at the Haydn Mausoleum of Eisenstadt Hill Church.

Further reading:

Dickey, Colin. Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius. Unbridled Books, 2010.

Geiringer, Karl with Irene Geiringer. Haydn: A Creative Life in Music. University of California Press, 1982.

“Haydn’s Skull is Returned.” LIFE Magazine, June 28, 1954.

Lovejoy, Bess. Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses. Simon and Schuster, 2013.

May 18, 2014

Industrial Espionage

by Pamela Toler

©Trustees of the British Museum

The Chinese produced luxury silk fabrics for several thousand years before they began trading with the west. Scraps of dyed silk gauze found in a neolithic site in Zhejiang Province date from 3600 BCE. Silk fabrics woven in complex patterns were produced in the same region by 2600 BCE. By the time of the Zhou dynasty, which controlled China from the twelfth to the third centuries BCE, silk was an established industry in China.

Wild silk, spun from the short broken fibers found in the cocoons of already-emerged silk moths, was produced throughout Asia. Only the Chinese knew how to domesticate the silk moth, bombyx mori, and turn its long fibers into into thread. They kept close control over the secrets of how to raise the domestic silkworm and create silk from the long fibers in its cocoon. Exporting silkworms, silkworm eggs or mulberry seeds was punishable by death. It was more profitable to export the finished product than the means of production.

The Chinese monopoly on the secrets of silk production and manufacture was eventually broken. According to one story, a Chinese princess, sent to marry a Central Asian king, smuggled out what silk cultivators called the “little treasures” as an unofficial dowry. (In one cringe-inducing version of this story, the princess carried the silkworms in her chignon to escape detection at the border.* It was illegal for a commoner, like a border security agent, to touch the head of a member of the royal family.) A totally different tradition tells of two Nestorian monks who smuggled silkworm eggs out of China in hollow staffs and carried them all the way to Byzantium, traveling in winter so the eggs wouldn’t hatch.

However the “little treasures” traveled, the Chinese monopoly on silk production was over by the sixth century CE, when the Middle Eastern cities of Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo, Tyre, and Sidon became famous for their silks.

* Would you want these in your hair?  Makes your scalp crawl doesn’t it?

Makes your scalp crawl doesn’t it?

May 16, 2014

Virgil and the 9/11 Memorial

The 9/11 Memorial Museum is about to open to the public and a free audio guide app is now available to the public.

The 9/11 Memorial Museum is about to open to the public and a free audio guide app is now available to the public.

As a Classicist who has just adapted an incident from the epic poem The Aeneid for teen readers, what particularly interests me is the quote by Virgil seven levels below ground in the Memorial Hall. This quote sums up the passage I have been working on for the past half year. I was surprised to discover that this exact quote is prominently displayed in Memorial Hall.

And yet, I was not surprised. Poetry, even when written two millennia ago, has the power to give a kind of immortality to those whom the poet commemorates.

Here is a transcription of the part of the audio guide that describes the inscription:

Stop 10 – Memorial Hall. In the vast space known as Memorial Hall, first glimpsed from the overlook, you will again encounter the quote from the poet Virgil, presented in letters about fifteen inches tall, forged by blacksmith Tom Joyce in steel recovered from the World Trade Centre Site. Virgil’s words read “No day shall erase you from the memory of time. ” A sea of blue surrounds the quote: 2983 individual paper watercolours in different shades of blue pay tribute to the people killed on 9/11 and in the 1993 bombing. Artist Spencer Finch created this exhibition titled “Trying to remember the color of the sky on that September morning” especially for this space in the museum. [More about Memorial Hall is available on the Witnessing History Tour.]

Witnessing History – Memorial Hall – Here, dominating the space of this Memorial Hall is a quote from the Roman poet Virgil that captures the commemorative context for the entire museum. Suggesting the transformative potential of remembrance, each letter was forged from remnant World Trade Center steel by blacksmith Tom Joyce. Here’s Tom: “As a sculptor and blacksmith I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the properties of iron. There’s iron in every red blood cell and it’s the iron in our blood that brings oxygen to the cells in our bodies. In a sense, iron makes life possible. Whenever it is touched by fire, iron goes through a transformative process, and that is what you can see in the letters of the Virgil quote. I was invited to use material salvaged from the ruins of the World Trade Center. I knew that fire could forge this wounded, remnant steel into letters of hope and beauty, reminding us that Virgil’s words not just a statement; they are a promise.”

There has been some controversy about the use of this quote based on its original context, the story of two teenage boys. Nisus and Euryalus are refugees from the sacked city of Troy, famous for Achilles, Paris, Hector and the Trojan Horse. The two youths have just landed in Italy under the leadership of the hero Aeneas, who hopes to found a new Troy on the banks of the river Tiber. There have been several prophecies that his band of Trojans will settle there and he believes he has a divine mandate. Aeneas has just gone upstream to make some allies when local warriors besiege the wooden fortress the Trojans have built. The Rutulians threaten to burn the fortress in the morning. That night, Nisus and Euryalus decide to risk their lives by sneaking through the sleeping, besieging troops to warn Aeneas and get help. However, their brave mission goes disastrously wrong when they give in to the temptation to slaughter and rob their slumbering enemies. A flashing helmet, taken as booty, gives away the younger boy, Euryalus. When he is surrounded by enemy troops, his friend Nisus runs out of the woods crying “Me, me! Kill me instead!” Both boys die, but because of the sacrificial gesture of the elder boy, Nisus, Virgil promises that they will never be forgotten.

There has been some controversy about the use of this quote based on its original context, the story of two teenage boys. Nisus and Euryalus are refugees from the sacked city of Troy, famous for Achilles, Paris, Hector and the Trojan Horse. The two youths have just landed in Italy under the leadership of the hero Aeneas, who hopes to found a new Troy on the banks of the river Tiber. There have been several prophecies that his band of Trojans will settle there and he believes he has a divine mandate. Aeneas has just gone upstream to make some allies when local warriors besiege the wooden fortress the Trojans have built. The Rutulians threaten to burn the fortress in the morning. That night, Nisus and Euryalus decide to risk their lives by sneaking through the sleeping, besieging troops to warn Aeneas and get help. However, their brave mission goes disastrously wrong when they give in to the temptation to slaughter and rob their slumbering enemies. A flashing helmet, taken as booty, gives away the younger boy, Euryalus. When he is surrounded by enemy troops, his friend Nisus runs out of the woods crying “Me, me! Kill me instead!” Both boys die, but because of the sacrificial gesture of the elder boy, Nisus, Virgil promises that they will never be forgotten.

Fortunati ambo, writes Virgil. “Blessed pair! If my poem has any power, no day shall erase you from the memory of time.”

You can read the original Latin HERE. It starts at line 175 and our quote is at line 447. You can read the English poet Dryden’s magnificent translation HERE. You can read what various scholars have said about the controversy HERE. And you can read my version of the story in The Night Raid.

May 14, 2014

The Devil’s Cruelty to Mankind: The story of George Gibbs

London’s history is full of sad stories. Despairing single mothers who destroy their children and sometimes themselves. Domestic violence. Addiction. Bedlam. I’ve seen so many of them that although I try to register each one as a human event, sometimes they become politicised or even comical. Worse still, sometimes they are just a number. So, when flipping through a notebook for something completely different today, I stumbled back across the story of George Gibbs of Houndsditch.

George’s life and death were the subject of a broadside ballad published in 1663, when his death had shocked London. The ballad tells of how Satan tempts George repeatedly to take his own life, referring to previous suicidal thoughts. Yet he is not on the margins of society: he has friends, employment as a sawyer, and a wife. Then, on ‘Fryday 7th of March’, George did ‘most cruelly ripp up his own belly and pull’d out his bowells and guts and cut them in pieces; to the amazement of all the beholders and the sorrow of his friends, and the great grief of his wife, being not long married, and both young people’.

For those who had witnessed, or heard of George’s death, the idea that the Devil must have had a hand in it may have seemed very real. Yet the ballad is not the end of the story. George’s death is recorded, baldly, as suicide in the parish register of St Botolph’s Without Aldgate, presumably where he worshipped. George, of course, could not be interred there, but the church instead had him buried in the graveyard at Bedlam Hospital in nearby Moorfields.

There is no clear indicator of George’s age, but the description of them as ‘young people’ would lead me to place them in their early twenties, possibly younger. And while the ballad lays the blame firmly at the feet of the Devil, the church laid the blame at the feet of a mental disturbance. Yet the ballad also gives an intriguing last word. It instructs that the lyrics to the story of George’s suicide should be set to the theme of ‘Two Children [it means Babes] in the Wood’. Babes in the Wood was first published in the late sixteenth century and tells of two small children left in the care of their uncle and his wife after they are orphaned. The uncle then abandons the children in the wood, where they perish alone. I can’t help wondering if the balladeer of that broadside wasn’t taking a personal shot at George’s friends, family and parish, or perhaps wider swipe at a society which stood by and watched as one troubled young man’s life and death played out.

The Divil’s Cruelty to Mankind: The story of George Gibbs

London’s history is full of sad stories. Despairing single mothers who destroy their children and sometimes themselves. Domestic violence. Addiction. Bedlam. I’ve seen so many of them that although I try to register each one as a human event, sometimes they become politicised or even comical. Worse still, sometimes they are just a number. So, when flipping through a notebook for something completely different today, I stumbled back across the story of George Gibbs of Houndsditch.

George’s life and death were the subject of a broadside ballad published in 1663, when his death had shocked London. The ballad tells of how Satan tempts George repeatedly to take his own life, referring to previous suicidal thoughts. Yet he is not on the margins of society: he has friends, employment as a sawyer, and a wife. Then, on ‘Fryday 7th of March’, George did ‘most cruelly ripp up his own belly and pull’d out his bowells and guts and cut them in pieces; to the amazement of all the beholders and the sorrow of his friends, and the great grief of his wife, being not long married, and both young people’.

For those who had witnessed, or heard of George’s death, the idea that the Devil must have had a hand in it may have seemed very real. Yet the ballad is not the end of the story. George’s death is recorded, baldly, as suicide in the parish register of St Botolph’s Without Aldgate, presumably where he worshipped. George, of course, could not be interred there, but the church instead had him buried in the graveyard at Bedlam Hospital in nearby Moorfields.

There is no clear indicator of George’s age, but the description of them as ‘young people’ would lead me to place them in their early twenties, possibly younger. And while the ballad lays the blame firmly at the feet of the Devil, the church laid the blame at the feet of a mental disturbance. Yet the ballad also gives an intriguing last word. It instructs that the lyrics to the story of George’s suicide should be set to the theme of ‘Two Children [it means Babes] in the Wood’. Babes in the Wood was first published in the late sixteenth century and tells of two small children left in the care of their uncle and his wife after they are orphaned. The uncle then abandons the children in the wood, where they perish alone. I can’t help wondering if the balladeer of that broadside wasn’t taking a personal shot at George’s friends, family and parish, or perhaps wider swipe at a society which stood by and watched as one troubled young man’s life and death played out.

May 11, 2014

Famous Sailors Who Couldn’t Swim

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (W&M Contributor)

Most sailors, up until the late nineteenth century could not swim. Why not? I’ve read that it was because European and English sailors were afraid of the cold Atlantic and that many sailors came from landlocked regions where it was thought that immersion in water would only bring disease or death. Water was dirty, and usually cold. And if you were unfortunate enough to fall overboard on a sea voyage, you could not expect to be saved, so it was better to die quickly.

A few early seafarers were famously good swimmers. In a narrative of his father’s life, the son of Christopher Columbus reported that his father had jumped from a burning ship during a sea battle, swimming several miles to shore, while most of his companions, unable to swim, either died on the boat or in the water. The fictional adventurer Robinson Crusoe saved himself from a shipwreck because he could swim. And when he first saw the clever man who would become his servant, Friday was escaping from his captors by swimming away from them. This popular tale did not, however, inspire many real life sailors of the eighteenth century to learn how to keep themselves afloat.

Captain James Cook, whose extraordinary voyages took him thousands of miles around the globe in uncharted waters, died in a violent confrontation on the shoreline of Hawaii. He may well have been able to save himself by jumping in the water, where a group of his men were trying to manoever a boat to reach him just off shore. Who knows, if he had been able to swim he might have returned to England and died at home of some landlubber’s disease, like Christopher Columbus.

The death of Cook, February 14, 1779. Painting by Herb Kawainui Kane

The earliest sailors in the South Pacific were another story. The amazing pioneers who over 900 years ago somehow crossed 2500 miles to Hawaii in outrigger canoes must have been able to swim. And swimming in the warm and clean waters of sparsely populated Polynesia seems to have been something that everyone did – to the astonishment of the first European crews who, arriving off the shores of Tahiti, saw men and women bobbing toward them in the water. No wonder they thought they were seeing mermaids.

May 9, 2014

The ‘Rapunzel syndrome’

By Helen King

Who’s your favourite Disney princess? How about the lovely Rapunzel, whose long golden hair – according to ‘Tangled’ (2010) -has healing properties? Every now and then I come across a disorder or a remedy I had not only never heard about, but had never imagined… Such is ‘Rapunzel syndrome’. To backtrack a little, and – trust me! – this does all connect, the other day I was in the amazing Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna looking at the wonders and marvels collected by the Hapsburg rulers. Among these were some ornately decorated bezoars:

If you know your Harry Potter, you’ll have met these in the first year of Potions classes, but bezoars are a real part of medical history. They are formed from indigestible material that accumulates in the stomach and intestines: cellulose from fruit and vegetables… and hair. While they often come from goats, any mammal – including humans – can form them. The name is Arabic in origin, and means ‘expelling poison’, because these were used as remedies against poison, and were also believed to protect against being poisoned in the first place, so by adding one to a drink, you made it safe. In their ‘raw’ form they look like these:

But in the early modern world they also acquired a range of further medical powers. They were surprisingly light for their size and appearance, and easy to scrape, so that pieces could be ground up and dissolved to be used in a range of remedies. So in Aristotle’s Experienced Midwife a child with worms, if there is also a fever, should be given a remedy containing lemon juice, pomegranates, oranges, vinegar, hartshorn, bezoar and confection of hyacinth.

Ambroise Paré described wealthy sixteenth-century people taking a dose of bezoar twice a year in order to preserve their youth, and tells the story of an experiment performed on a cook who was due to be hanged for stealing silver, but who agreed instead to take poison and bezoar in the hope that he would survive. He didn’t. Paré concluded that no one remedy can be effective against every sort of poison.

Experiments in the 1990s suggest that bezoars do work, against arsenic; and for one of the two toxic parts of arsenic, it is neutralized by ‘bonding to sulphate compounds in the protein of degraded hair, a key component in bezoars’ (Barroso 2013). Hair again. I mentioned that bezoars can form in humans too. Back to Rapunzel! In Stephen Sondheim’s brilliant musical take on fairy tales, ‘Into the Woods’, the prince who longs for Rapunzel describes her:

High in her tower she sits by the hour

Maintaining her hair

Blithe and becoming and frequently humming

A light-hearted air.

He goes on to observe to the prince who has fallen for Sleeping Beauty that:

You know nothing of madness

‘Til you’re climbing her hair.

All that hair can pose a danger. Modern medicine recognizes a rare condition in which people – almost always girls or young women – eat their own hair, which eventually forms a mass that blocks digestion and which has to be removed. The hair can not only fill the stomach, but even have a long ‘tail’ extending into the intestines, like Rapunzel’s long hair hanging down from her window. While this condition has been known since at least the eighteenth century, only in 1968 was it named: ‘the ‘Rapunzel syndrome’. So it’s not the Disney healing hair: it’s a potential cause of death!

M. D. S. Barroso, ‘Bezoar stones, magic, science and art’, Geological Society of London Special Publications 11/2013; 375(1):193-207.

C. Malcom, ‘Bezoar stones’ (1998), http://www.melfisher.org/pdf/Bezoar_S...