Holly Tucker's Blog, page 53

July 13, 2014

The Bespoke Midwife

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

Midwives Made to Order

‘Call the midwife’: yes, but call as you go into labour, or call well in advance of the due date? Today, when we talk about having something ‘bespoke’ we mean having it made to order – for example, a suit, or a pair of shoes. But a person too can be ‘bespoke’ if engaged – that is, ‘spoken for’, or booked specifically – in advance. And in the eighteenth century, when men were moving into normal childbirth as ‘men-midwives’, a key stage of their progress was when they came to be ‘bespoke’.

Books, Booking, and Training

We can get some idea of how this worked from Brudenell Exton’s 1751 book, A New and General System of Midwifery in four parts (London: W. Owen). He described his training under Edmund Chapman in 1737 and 1738, and said that although he admired Chapman’s practical skills he was not so convinced of his theoretical knowledge. After learning with Chapman, he took some more courses with Richard Manningham. While Chapman was a user of the still-new equipment, the obstetric forceps, Manningham rejected these and preferred the older method of the ‘fillet’, a more flexible looped structure by which the baby’s head could be grasped. Indeed, in the eighteenth century there was not always a neat line between forceps-fans and forceps-opponents; Chapman, although he used the forceps, preferred manually turning the baby in the womb, and if that failed, then he would use the fillet or the forceps.

In his book Exton gives details of 19 cases to which he was called. Some of these are emergency cases. In others, however, he was ‘bespoke’ – booked in advance. These cases show the sorts of reasons that, at this early stage of men-midwives, led to them being used, and also hint at why you would book one in advance.

Why Make the Call?

Sometimes, a man-midwife was called because there was an emergency, such as a very long labor, or the waters breaking too early. It is interesting to speculate about who decided that labor has gone on for too long, but in two of these cases the period of two days is mentioned, and in another the midwife had been in attendance for several days before calling Exton in. Exton says for one of his emergency calls that a midwife and ‘a Gentleman just set out in the Profession’ were there already. The baby’s head was ‘monstrously large’. In another, the woman is having twins but the second of these is not emerging normally. There is another multiple birth in his case list – this time, triplets, which are born alive without his intervention. It is not clear here why he was called, but a potential emergency seems most likely. He was also called after the baby had been delivered, if the placenta remained inside, or when the midwife suspected there was a ‘false conception’ still to come out.

What about the bespoke calls? In one, ‘A Person, who had a very hard labour of her first Child, spoke to me to attend her of the second. Accordingly I was sent for…’ In another, ‘I was sent for to a Woman in this Neighbourhood, who had some time before spoke to me to attend her in her Pains, having before had a difficult Delivery’. Here, ‘spoke to me’ indicates his status as ‘bespoke’. In another, ‘About three Years ago, a Person came, to desire that I would attend her in her Labour, for that she was in her 42nd Year, and the first Child. I promised her I would’. The fourth and final bespoke case opens as follows: ‘I was sent for, about Six months since, to a Woman who had before spoke to me to attend her in her Labour’.

So in two cases, the previous labor was so bad that a man-midwife seemed the way to go. In another, the woman was having her first baby in her 42nd year – what we now call an ‘elderly primagravida’. But in the fourth, there is no reason given. Perhaps this case represents the point at which the man-midwife becomes the attendant of choice even for those who have not had a previous bad experience, and who are not in an unusual category.

Lessons Learned

One lesson we can learn from this concerns how to use the wonderful online resources now available. Exton’s book is on Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). This site allows the user to search the text. But if you search ‘bespoke’, you won’t find it in Exton. ‘Spoke’ will find you three out of four of the bespoke cases. But the fourth one, ‘came to desire that I would attend’ is not going to show up with a search on either ‘bespoke’ or ‘spoke’. There is no substitute for reading the whole text!

Further reading:

Adrian Wilson, The Making of Man-Midwifery: Childbirth in England, 1660-1770 (1995)

Helen King, Midwifery, Obstetrics and the Rise of Gynaecology (2007)

July 12, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. vi

Another week has passed, and we reopen the CABINET OF CURIOSITIES to our readers. What intrigued us this week?

Another week has passed, and we reopen the CABINET OF CURIOSITIES to our readers. What intrigued us this week?

The Vault reported on the discovery of a 175 year old letter from “Amistads” thanking John Quincy Adams for arguing their case in front of the Supreme Court in 1841. The article includes images and transcriptions that reveal a great deal about religious and abolitionist beliefs during the period.

Elsewhere, The Journal of the American Revolution asked historians to debate “Who was the Best Husband-Wife Duo” of the revolution? (Favorites include John and Abigail Adams and George and Martha Washington.)

Moving back in time, Medievalists considered rhetoric and friendship in medieval letter collections.

Our love of material culture was stoked, as the folks at “Mr. Pepys’s Small Change” walked us through the process of researching early London with an eye to how even the seemingly simplest tokens can lead historians to uncover stories about long-gone individuals and their lives.

Finally, we loved the Smithsonian’s story about Smokey the Bear’s iconic hat and how it was lost not once, but twice, before joining the museum’s collection. We’re grateful that this piece of sartorial history is now safe and sound.

What caught your attention this week? Be sure to tell us in the comments section below, or on Twitter!

July 11, 2014

Editor’s Corner: Books We love

Holly Tucker, Editor-in-Chief

Holly Tucker, Editor-in-Chief

Remember in Harry Potter when the owls drop thousands of letters on the front porch, down the chimney…everywhere?

That’s sometimes how it feels at my house.

As Editor of Wonders & Marvels, I receive all sorts of books for consideration on the site. There is rarely a day when fewer than one, two, three or more books show up at my door.

Many of these, publicists send in the hopes a book will catch the eye. Others, I request. In any case, I’m always happy to get a visit from the book owls.

I’m always on the prowl for new books on topics that will interest W&M readers. I scour Publisher’s Weekly, publisher’s catalogues, and read tons of book reviews. My coffee table, computer desk, and nightstand are full of books in various states of reading.

When one really grabs me, I reach out to the author and invite them to share something about their book with our readers. But it has to be a really compelling book. And it has to be well-writted and meticulously researched. (That goes for both nonfiction and historical fiction.)

There it is, that’s the unscientific process of how it’s done. That’s how we consistently bring great posts about the hidden stories of history.

But sometimes there is a book that is just so unforgettable, so amazing, that a guest post just doesn’t do the trick.

Karen Abbott’s Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy is one of them.

By way of disclaimer, I count Abbott as a friend. She’s also a regular contributor on Wonders & Marvels. (And, FYI, she prefers to be called by her last name.)

But none of this matters. What matters is that the book is good, really good. I had the privilege to read the book in drafts as it was slowly taking form. And not long ago, I read an advance copy of the final version. Even being already super-familiar with the story by now, I could not put it down.

Abbott has an uncanny ability to bring the past to life. Her story of four spies, all women, captures the drama, intrigue, and deep human dimension of the Civil War.

Wonders & Marvels has paired with Abbott to provide a special weekly newsletter that provides a behind-the-scenes look into Civil War espionage.

It is the first of what we hope will be three or four partnerships with Authors-Whose-Books-We-Love each year. Think of it as something like a very special “Good House Keeping” stamp of approval. I’ve read the book; our managing editor Miranda Nesler has read the book. We love the book, and we think our readers will too. (For the record, we receive no financial gain for doing this. No incentives, commissions, nothing, nada.)

So sign up for Abbott’s newsletter! You’ll be glad you did.

Rumor has it there are some very special treats in store for subscribers to the Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy newsletter—including some messages written in hidden ink. I think the first giveaway starts next week.

Have a great week!

Holly

(p.s. Know of any great titles we won’t want to miss? As always, feel free to shoot me an email!)

July 10, 2014

Bone Magic

By Sandra Gulland (Guest Contributor)

By Sandra Gulland (Guest Contributor)

What is Bone Magic?

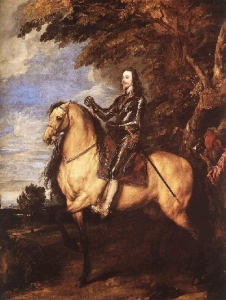

Bone Magic was a ritual used in the 17th century to tame unruly horses. George Ewart Evans details the procedure in The Days That We Have Seen:

1) Kill a frog or toad.

2) Leave it on a whitethorn bush overnight.

3) Bury in an anthill.

4) Under the light of the full moon, dig it up and–watching it very carefully, never glancing away, take the skeleton to a running stream. Throw it into the water, and watch it go upstream, then wait for the crotch bone to float back, against the current. (“The Devil is there with you then,” it was said.”

5) When dry, crush the bone into a powder and mix with oil.

6) Dip your finger in it and wipe it on the horse’s tongue, his nostrils, his chin and chest.

The bone powder was believed to give the possessor “magic” (i.e., diabolical) control over horses. “Then the horse is your servant, and you can do what you like with him.”

Continued Uses and Traditions

Bone Magic continued to be used even into the last century. “It gives you that confidence. You can trust yourself to it. There’s nothing that will get away from me.” Some of the men who practiced Bone Magic were reported to go mad, become “unhinged.” It was said that they had “been to the river,” “been round rivers and streams.” One man claimed that his stallion stood beside his bed at night. His wife told him, “You have to do something. Nothing bakes right; I don’t feel right. And you, awake all night and your horse coming to the side of your bed.” To get rid of the curse, he dug a hole in clay, filled the tin of bone powder with milk and vinegar, and buried it in the hole. He could sleep then, but he couldn’t control horses as well, he said, having to use “circus cords” to keep them under control.

Bone Magic continued to be used even into the last century. “It gives you that confidence. You can trust yourself to it. There’s nothing that will get away from me.” Some of the men who practiced Bone Magic were reported to go mad, become “unhinged.” It was said that they had “been to the river,” “been round rivers and streams.” One man claimed that his stallion stood beside his bed at night. His wife told him, “You have to do something. Nothing bakes right; I don’t feel right. And you, awake all night and your horse coming to the side of your bed.” To get rid of the curse, he dug a hole in clay, filled the tin of bone powder with milk and vinegar, and buried it in the hole. He could sleep then, but he couldn’t control horses as well, he said, having to use “circus cords” to keep them under control.

Sandra Gulland’s novel, Mistress of the Sun, is set in the 17th century court of Louis XIV, the Sun King. She is also the author of the Josephine B. Trilogy, internationally best-selling novels based on the life of Josephine Bonaparte, now published in 14 countries. She has two blogs, one on writing and one on 17th century research. For more information, see her author website.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 26 December 2008.

Image: Anthony van Dyck, “Charles I on Horseback,” 1635. (Windsor Castle Royal Collection)

Source: Evans, George Ewart. The Days That We Have Seen. London: Faber and Faber, 1975.

Wonders and Marvels

July 9, 2014

“Welcome to the Battle” (21st Century Style)

Me with some new Confederate friends, July 24, 2011.

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

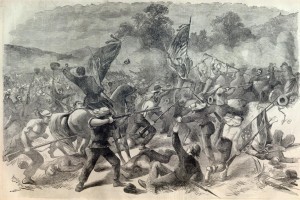

July 21, 1861, saw the first major battle of the Civil War: The Battle of Bull Run (called Manassas in the South). President Lincoln was counting on a decisive victory to quell the rebellion, then only three months along. But Rose O’Neal Greenhow, one of the Confederate spies I feature in my book, Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, provided the rebel army with crucial information that led to its shocking victory. When the 150th anniversary reenactment of this battle took place, I was there.

Witnessing History

At 9 a.m. on Sunday, July 24, 2011, a phalanx of shuttle buses lined up at the Jiffy Lube Live amphitheater in Bristow, Virginia, waiting to transport twenty-five thousand Civil War aficionados to the reenactment, a two-hour production in 93 degree heat. They came from all over the country: men sweating in period muslin undergarments and wool frock coats; women wearing swinging hoop skirts and calico hats; squealing babies swaddled in Confederate-style onesies. After a ten-minute ride, during which spectators sipped iced Frappuccinos and watched an educational video about the significance of this event, the caravan arrived at Pageland Farm, a 200-acre spread adjacent to the actual battlefield.

People jockeyed for prime seats on the bleachers. One woman yanked on a volunteer’s sleeve. “I was told there would be bleachers in the shade,” she said. “Where are they?” The volunteer shrugged and directed her to the information table. One row back, a father turned to his son, about twelve years old. “You gotta know the battlefield,” he scoffed. “Who asks for bleachers in the shade?”

Reenactment and Its (Dis)Contents

On crisp, yellowed grass, 9,000 Confederate and Federal troops wielded authentic smoothbore muskets and hunched over cannons, wrapping gunpowder in aluminum foil. A man from the 6th North Carolina napped near the sidelines. The cheery sounds of “Dixie” drifted from a fife, and a ten-year-old drummer boy kept up a steady beat. Soldiers filled their caps with ice from plastic bags. An announcer came on the PA system to request that all cell phones be turned off. “Welcome to the battle,” he added, and it was on.

Illustration of the battle from Harper’s Weekly, August 1861.

One hundred fifty years ago a hailstorm of cannon balls filled the sky; now the air remained clear save for waving flags and thick, drifting rings of smoke. “A soldier could look and find his regiment flag if he got separated from the group,” the announcer explained. “And look! Here comes the cavalry of J.E.B. Stuart.” The spectators wolf-whistled and applauded. Latecomers arrived carrying paper baskets of cheese fries and red-white-and-blue snow cones. On July 21, 1861, civilians arrived by carriage from Washington hoping to glimpse the carnage, dipping into picnic baskets and sipping champagne, waiting to toast a Union victory.

The bleachers shuddered at each crackle and boom. People brandished video cameras and iPhones and leaned forward. Confederate reserves arrived by horse, regiment after regiment, a furious vortex streaming in from all sides. General Thomas Jackson, who acquired the nickname “Stonewall” during this battle, appeared on the top of the Henry House Hill plateau. “The Army of the Shenandoah is on the battlefield,” the announcer intoned. “Jackson instructed his men to ‘yell like furies!’” The 21st century Jackson doppelganger instructed the same. The soldiers obliged and unleashed their “rebel yell,” the Confederate battle cry that Shelby Foote described as a “wildcat screech, foxhunt yip, banshee squall.”

Above the din, the son asked his father, “Wait… where’s Jackson?”

“Look over there by the power lines,” the fathered replied, pointing. “There’s the man who’s portraying him.”

“Duh,” the kid said.

The announcer’s voice grew ominous. “The tide of battle is beginning to turn,” he intoned. “The Federals are retreating.” Rows of men in dark blue marched calmly toward the general direction of Washington. The fife player switched to “Yankee Doodle.”

A woman in the front row shielded her eyes with her hand, squinting at the field. “Why is no one dying?” she asked her companion. “Never mind—there’s one on the ground.”

As if on cue, the dead soldier, in a last full measure of devotion, reached his hand back and scratched his ass.

With every boom of cannon the spectators cheered louder. One woman circled a corndog above her head.

“It’s not historically accurate,” the man told his son, “but there’s Robert E. Lee coming down the field.”

“Are you having a good battle, general?” the announcer asked, and General Lee raised an arm. “I’ll take that as a yes.”

One Confederate solider helped a wounded comrade off the field, gripping his arm as he limped along. “All right, that’s good enough,” the wounded man said as they passed by the bleachers. A volunteer offered a bottle of water, donated by Prince William Hospital.

“Many Washington politicians,” the announcer explained, “came down with their wives and families to see the battle and got mingled with the Federals on their retreat. Congressman Alfred Ely from New York was captured by the Confederates, hiding behind a tree.”

“What an asshole,” the kid said.

“Duh,” the dad retorted.

Two hours after the first shot, spectators began stomping down bleachers, heading back toward the direction of Jiffy Lube Live. The retreat to the idling, air-conditioned shuttle buses was slow but orderly. None of them drowned in the creek or slipped on grass slick with blood, as they had at First Manassas.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the announcer called, “you have just witnessed a glimpse of what it might have been like here in 1861. Please let’s have a round of applause for their efforts.”

The remaining crowd shouted half-hearted “Huzzahs,” muted by the effects of the soaring heat.

“Thank you for attending the 150th reenactment of First Manassas,” the announced concluded. “Don’t forget to get your souvenir programs. And there will be a program at 1 p.m. in Tent One called “The Scourge of Slavery: the Frederick Douglass Story.”

“Let’s go watch Gods and Generals now,” the kid said.

The last of the fallen reenactors rose, brave patriots eager to share a cold beer with their countrymen, and the wisps of smoke looped faintly around the trees.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her forthcoming book about female Civil War spies, Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, will be published by HarperCollins on September 2.

In collaboration with Wonders& Marvels, Karen Abbott is hosting a special newsletter with giveaways and sneak peeks for LIAR, TEMPTRESS, SOLDIER, SPY. Be sure to subscribe below!

Subscribe to our newsletters!

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

Subscriptions

Weekly Feature: Liar Temptress Soldier Spy

Wonders & Marvels Monthly

July 8, 2014

A Friend of Men of Color: Francis Scott Key & Slavery

By Marc Leepson (Guest Contributor)

Early in June of 1842, a huge crowd of mourners turned out for the funeral of William Costin, the widely respected leader of the free African-American community in the nation’s capital. More than seventy carriages filled with people, some of them white, trailed his casket to the cemetery, followed by a long line of men on horseback, all of them African-Americans with one exception. The one white rider was the noted Washington, D.C., lawyer Francis Scott Key.

It “must be admitted,” an abolitionist newspaper commented, “that for a distinguished white citizen of Washington to ride alone among a larger number of colored men in doing honor to the memory of a deceased citizen of color evinces an elevation of soul above the meanness of popular prejudice, highly honorable to Mr. Key’s profession as a friend of men of color. He rode alone.”

Francis Scott Key is known to nearly every American as the man who wrote the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1814. During his lifetime, however, he was much better known as one of the top lawyers in Washington who ran a lucrative private practice in Georgetown and Washington. He played important roles in several high-profile court cases, argued scores of cases before the Supreme Court, and served for eight years (1833-41) as the city’s U.S. Attorney.

“As He was Known to Family and Friends”

Frank Key—as he was known to family and friends—was a morally upright, conservative, and deeply religious family man. He also was a national player throughout his adult life in the most important social, political, economic and humanitarian issue of the Early Republic: slavery. As the young nation came alive in the 1820s, 30s and 40s, the slavery issue remained stubbornly unresolved. Francis Scott Key helped shape the national debate over slavery.

A slave owner from a large slave-owning family, Key was an early and ardent opponent of slave trafficking. By all accounts, Key treated his own slaves humanely, and freed several during his lifetime. What’s more, he had a deserved reputation for providing free legal advice to impoverished free blacks and slaves in Washington.

“If ever man was a true friend to the African race, that man was Francis Scott Key,” his friend, the Rev. John T. Brooke, one wrote. “Throughout his own region of the country, he was proverbially the colored man’s friend. He was their standing gratuitous advocate in courts of justice, pressing their rights to the extent of the law, and ready to brave odium or even personal danger in their behalf.”

A Complicated Legacy

There is no doubt that Key’s legacy is a complicated one. The “true friend to African Americans” was, after all, one of the founders and most active proponents of the American Colonization Society. That was the controversial group founded in Washington in 1816 that worked for decades to send free African-Americans to a colony on Africa’s West Coast that became the nation of Liberia. The group was reviled by abolitionists and many free blacks as little more than a vehicle to rid the nation of African Americans.

In addition, there is the fact that Key’s long-time close personal and professional friend (and brother-in-law) Roger B. Taney, the U.S. Chief Justice, issued the infamous majority opinion in the 1857 Supreme Court Dred Scott case. In that case, Taney ruled that no enslaved African-American or any freed African-American descended from slaves could be a citizen of the United States.

Journalist and Historian Marc Leepson is the author of eight books. His latest, What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, A Life, the first full biography of the author of The Star-Spangled Banner in more than seventy-five years, was published by Palgrave on June 24.

Wonders & Marvels has five (5) copies of Marc Leepson’s WHAT SO PROUDLY WE HAILED for an exciting July giveaway! Simply subscribe to our monthly giveaway list here! The entry period will end 11:59pm EST on July 31. (Currently we can only ship in the US)

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our newsletter below!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

July 7, 2014

Zuni Creation Story

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

image/Walter Myers

“All kinds of beings were changed to stone. We find their forms, sometimes large like the beings themselves, sometimes shriveled and distorted. We see among the rocks the shapes of many beings that live no longer. ” –Zuni elders, 1891

The Zuni creation story has strong ties to the landscape of volcanic mountains and deeply eroded canyons of the Colorado Plateau (Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico). Like many other Native cultures, the Zuni believed that our present era was preceded by a series of ages, each populated by different beings.

Origins

In Zuni myth, the new earth was flooded and wracked by earthquakes. Bizarre monsters ruled this dark, watery world, while small proto-humans with clammy skin, goggle eyes, bat ears, tails, and webbed feet crept along like salamanders, barely surviving in muddy island caves. To keep these “unfinished” humans from succumbing to the great monsters of the deep, the Twin Children of the Sun realized that the world needed to be dried out and solidified. With a magical rain-bow and cosmic lightning arrows, the Twin Heroes set tremendous conflagration over the face of the earth, scorching it dry and hardening the ground. Proto-humans emerged into the sunlight and began to become “finished” human beings.

But now, on dry land, huge predators with powerful claws and teeth multiplied and devoured the still-weak human beings. The Twin Heroes stalked across the world, blasting with lightning all the land monsters—gigantic bears, enormous lions, and other immense creatures. Instantly immolated, the dangerous beasts shriveled and became stone.

The Role of Material Objects in Myth Making

The Zuni interpreted the fossilized skeletons of dinosaurs and other extinct creatures that continually weather out of the Southwestern desert as the forms of the old monsters. Large animals transformed to stone were the original We-ma-we, fetishes with “hearts of power,” but they were too big to carry, so the Zuni gathered smaller teeth, claws, and fossil bones as amulets. Zuni carvers, aware of the links between fossils and We-ma-we, have recently begun to make small fetishes in dinosaur shapes.

Extensive exposures of Cretaceous sediments lie in Zuni territory. As Zunis gathered bentonite clay, salt, jet, gems, and minerals they came across the remains of large marine reptiles and dinosaurs with bizarre, horned skulls and huge teeth and talons trapped in rock. It was very good fortune to discover powerful relics from the “days of the new.” Among the most impressive dinosaur fossils in Zuni lands is a ceratopsian theropod with terrible claws, named Zuniceratops. Some 90 million years ago, razor-toothed raptor dinosaurs, duck-billed hadrosaurs, flying pterosaurs, giant centipedes, and tropical trees flourished on the fluctuating western shores of the inland sea that bisected North America, wetlands teeming with prehistoric crocodiles, giant sharks, and immense marine reptiles called mosasaurs. That ecology corresponds to the “days of the new” in Zuni mythology.

The Science Beneath the Stories

The dry climate and exposed topography make the Southwest a veritable textbook of geology. Millions years of geological events have left strong traces for scientists to piece together. The Zuni saw the presence of stone clams, ammonites, fish, large marine fossils, and impressions of ripples and mud cracks on the receding shorelines as proof that a sea had long ago covered the desert. Geological and paleontological clues led the Zuni to perceive that, eons ago, the arid desert was a watery world populated by monsters that no longer exist, followed by a fiery period marked by gigantic land predators that were transformed to stone. Volcanic evidence and lava flows—and living memories of eruptions—supported the Zuni idea of a great conflagration that dried out the young earth.

Some scientists propose that mass extinctions of Permian marine species 250 million years ago may have been caused by underwater explosion of gases, which could have been ignited by a single lightning bolt to set the earth aflame–a scenario remarkably reminiscent of Zuni myth. Paleontologists have discovered evidence of vast prehistoric fires that raged across the land, leaving burnt, petrified stumps, more stark evidence for the Zuni scenario, which also imagined the first humans as evolving from lower lifeforms. Concepts of evolution, extinction, climate change, deep time, geology, and fossils–all contained in one elegant Zuni myth!

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of Fossil Legends of the First Americans (2005), The First Fossil Hunters (2000, 2011), The Poison King (2010), and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

July 4, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. v

Ah, the CABINET OF CURIOSITIES. Once again, we get to open the door and reveal what historical news and happenings caught our imaginations this week and reminded us why we love the work we do!

Ah, the CABINET OF CURIOSITIES. Once again, we get to open the door and reveal what historical news and happenings caught our imaginations this week and reminded us why we love the work we do!

Ever considered body piercing and tattoos? Are you sporting body art of your own? UT Health Science Center reminds us that you’re participating in a long-standing, cross-historical tradition of body modification and visual bodily expression.

Oxford’s Dictionary reminded us that when we flippantly say “oodles,” we’re actually drawing on slang from the mid nineteenth century.

A group of medieval historians debated why (and what it means) that battlefields continue to be tourist landmarks - in Europe and beyond. (Which have you visited and how did they shape your childhood experience of ‘summer vacation’?)

The lovely team at Epistolae reminded us that women’s letters exist, and that they deserve attention from the public and from researchers. (We’re certainly grateful for such work!)

What caught your attention? Share it in the comments or get in touch with us on Twitter @history_geek!

Can’t get enough of W&M? Join our newsletter subscription list for regular updates, right in your inbox!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

var err_style = '';

try{

err_style = mc_custom_error_style;

} catch(e){

err_style = '#mc_embed_signup input.mce_inline_error{border-color:#6B0505;} #mc_embed_signup div.mce_inline_error{margin: 0 0 1em 0; padding: 5px 10px; background-color:#6B0505; font-weight: bold; z-index: 1; color:#fff;}';

}

var head= document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var style= document.createElement('style');

style.type= 'text/css';

if (style.styleSheet) {

style.styleSheet.cssText = err_style;

} else {

style.appendChild(document.createTextNode(err_style));

}

head.appendChild(style);

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

var mce_preload_checks = 0;

function mce_preload_check(){

if (mce_preload_checks>40) return;

mce_preload_checks++;

try {

var jqueryLoaded=jQuery;

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.type = 'text/javascript';

script.src = 'http://downloads.mailchimp.com/js/jqu...

head.appendChild(script);

try {

var validatorLoaded=jQuery("#fake-form").validate({});

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

mce_init_form();

}

function mce_init_form(){

jQuery(document).ready( function($) {

var options = { errorClass: 'mce_inline_error', errorElement: 'div', onkeyup: function(){}, onfocusout:function(){}, onblur:function(){} };

var mce_validator = $("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").validate(options);

$("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").unbind('submit');//remove the validator so we can get into beforeSubmit on the ajaxform, which then calls the validator

options = { url: 'http://wondersandmarvels.us6.list-man...?', type: 'GET', dataType: 'json', contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

beforeSubmit: function(){

$('#mce_tmp_error_msg').remove();

$('.datefield','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var txt = 'filled';

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

var bday = false;

if (fields.length == 2){

bday = true;

fields[2] = {'value':1970};//trick birthdays into having years

}

if ( fields[0].value=='MM' && fields[1].value=='DD' && (fields[2].value=='YYYY' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else if ( fields[0].value=='' && fields[1].value=='' && (fields[2].value=='' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else {

if (/\[day\]/.test(fields[0].name)){

this.value = fields[1].value+'/'+fields[0].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

} else {

this.value = fields[0].value+'/'+fields[1].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

}

}

});

});

$('.phonefield-us','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

if ( fields[0].value.length != 3 || fields[1].value.length!=3 || fields[2].value.length!=4 ){

this.value = '';

} else {

this.value = 'filled';

}

});

});

return mce_validator.form();

},

success: mce_success_cb

};

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').ajaxForm(options);

});

}

function mce_success_cb(resp){

$('#mce-success-response').hide();

$('#mce-error-response').hide();

if (resp.result=="success"){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(resp.msg);

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').each(function(){

this.reset();

});

} else {

var index = -1;

var msg;

try {

var parts = resp.msg.split(' - ',2);

if (parts[1]==undefined){

msg = resp.msg;

} else {

i = parseInt(parts[0]);

if (i.toString() == parts[0]){

index = parts[0];

msg = parts[1];

} else {

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

}

} catch(e){

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

try{

if (index== -1){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

} else {

err_id = 'mce_tmp_error_msg';

html = '

'+msg+'

';

var input_id = '#mc_embed_signup';

var f = $(input_id);

if (ftypes[index]=='address'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-addr1';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else if (ftypes[index]=='date'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-month';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else {

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index];

f = $().parent(input_id).get(0);

}

if (f){

$(f).append(html);

$(input_id).focus();

} else {

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

} catch(e){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

}

// ]]>

Editor’s Corner: Going Medieval

I’ve spent the past few weeks in jail. Or more precisely, a medieval dungeon.

I’ve spent the past few weeks in jail. Or more precisely, a medieval dungeon.

It’s too early to talk about the specifics of my next book. But I can say that a fair bit of it takes place in the keep of the Chateau of Vincennes.

A Fascinating Place

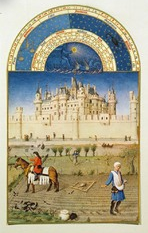

Most famous for its appearance in the Duke of Berry’s Book of Hours, the tower was once home to Charles V, who had been born there in in the 14th century. I first became fascinated by Charles V in graduate school. I took a course on the history of science in the Middle Ages. (Yes, there is such a thing as medieval sciences. The Dark Ages were not as dark as most people think.)

I remember writing a seminar paper on Charles V’s contributions to early libraries. The collection of manuscripts that he kept at Vincennes was unrivaled. Eventually they were transferred out of the tower at to the Louvre and became the foundation of what is now the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF).

Into a New Space

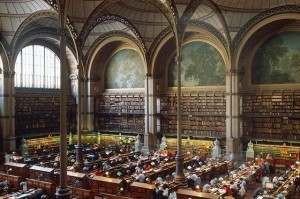

In 1666, Jean-Baptiste Colbert established the King’s Library in his home on the Rue Vivienne, where library remained until 1999. I can’t begin to tell you of my nostalgia for the many hours, days, months I’ve spent in

Bibliothèque Nationale’s small, stunning 19th-century reading room before the move.

The library’s transfer to the massive Tolbiac compound brings far less nostalgia. The place is huge. And, built

The library’s transfer to the massive Tolbiac compound brings far less nostalgia. The place is huge. And, built

deep into the ground, it makes you feel like you are trapped in a ultra-modern bomb shelter. It doesn’t help that the place has not aged well over the 15 years since it opened. I was stunned by how trashed out it was when I was there last summer.

Fortunately, with all that is now available in the BNF’s digital collections, I haven’t had to be subjected to the place much. The strangely efficient digital reproduction services for manuscripts has also been a huge boon for my work.

Out of the Reading Room, into the Dungeon

But back to the dungeon. From the late sixteenth century to WWII, the Tower of Vincennes served as one of the most notorious prisons in France.

The Tower has four turrets, one at each corner. A narrow and winding stone staircase fills one of the turrets. In the others, there is a small room on each floor. On the first few floors, these rooms had served as chambers for Charles V’s trusted advisors or as meeting rooms. The high, arched ceilings and walls were painted in rich indigo and burgundy. The rooms on the upper floors housed archers who stood guard

Later, the grandeur of the Tower gave way to great suffering. Prisoners paced the rooms nervously as they waited interrogation and eventual sentencing. Over time, the rich royal paint gave way to graffiti. Prisoners scribbled messages, prayers, and obscenities on the walls. Some marked time in hash marks.

This spring, I was lucky to get a private tour of the upper floors of the tower. They are usually closed to the public because the graffiti is so precious.

In my Editor’s Column next week, I’ll share some images of some of the more stunning bits that I found on those walls.

July 2, 2014

Secret Salem

An Appetite for Witches

Every year thousands of visitors throng into Salem, Massachusetts, appetites whetted for witches. And witches there are, for in Salem we are experts in witchery: witch hats, witch t-shirts, witch plays, even some real witches thrown in for good measure. Sometimes visitors are puzzled, however, that there aren’t more places to see that are tied to the actual Salem witch trials of 1692. The Witch House, was the home of a real Salem witch judge, and is maintained as a historic house today. But other than that, we find few elements of historical witchery remaining in what is essentially a nineteenth century city. Where did it go?

Origins and Background

Salem Town was first founded in the 1620s (its name comes from Salaam, or Shalom, meaning “peace”), and very quickly became one of the busiest and most important seaports in early colonial New England. So busy, in fact, that the rocky sea coast could not produce enough food to support the growing population. As a result, in 1636 an outlying farm region was established, to supply grain and goods for the port town. Initially the region was called Salem Farms, though quickly that name changed to Salem Village.

As we know, it was in Salem Village that the witch crisis first broke out. Salem Village held the meeting house where the most dramatic accusations took place. Salem Village was the home of Rebecca Nurse, Samuel Parris, and the people we remember from the The Crucible. Salem Village had a distinct personality that separated it from Salem Town, and some historians think that these clashing cultures contributed to the panic. Salem Village tried early on to pull away from Salem Town, but was not successful until 1757, when its name was changed to Danvers.

Present Day

Today, in Danvers, a memorial stands on the ground that once held the Salem Village meeting house, and Rebecca Nurse’s house is maintained as a historic property open in the summertime. True hunters after historical witchery know to look in modern Salem, and also its shadowy neighbor, the secret Salem Village, Danvers.

Katherine Howe is the author of the New York Times bestseller The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane

. She is completing a PhD in American and New England Studies at Boston University, and this August (2010), Signet Classics is publishing a new edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables with a new introduction written by Katherine. Read more about the book here.

. She is completing a PhD in American and New England Studies at Boston University, and this August (2010), Signet Classics is publishing a new edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables with a new introduction written by Katherine. Read more about the book here.This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 9 June 2010.

IMAGE: The Witch House, home of Judge Jonathan Corwin, is the only structure still standing in Salem with direct ties to the Witchcraft Trials of 1692.

Congratulations to the following W & M winners of this book:

Kimberly and Melanie