Holly Tucker's Blog, page 51

August 6, 2014

Comrade Count & the Princess of Mars

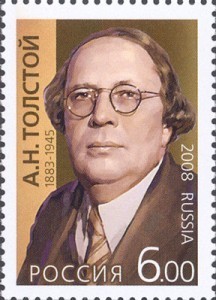

Russian Stamp in Honor of Aleksey Tolstoy

Ticket Home

In November 1922, the Soviet Embassy in Berlin held a festive literary evening for Soviet writers and émigrés sympathetic to the new regime. The occasion was the fifth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, and one of the honored guests was the former Count Aleksey Nikolaevich Tolstoy (a distant relative of Leo Tolstoy). Tolstoy, who had renounced his title earlier that same year, read from his new novel Aelita, or the Decline of Mars. The first installment of Aelita would soon appear in the Soviet journal Red Virgin Soil and in a few short months Tolstoy, now nicknamed “Comrade Count,” would return from Berlin to become a fixture in Soviet literature. Aelita is Tolstoy’s offering to the Soviet Union, his testimony of personal and professional transformation and his ticket home.

Poster for 1924 film Aelita: Queen of Mars

Revolution on a Cold Planet

In Tolstoy’s novel two earthlings travel to Mars where they meet Aelita, a blue-skinned Princess and daughter of the Martian leader. Aelita’s father wants to speed up the decline of his cold, dying planet by destroying its cities, which he sees as a source of anarchy, irrational desire, and discontent. While the working class toils away to support them, the Martian upper class lives a life of peaceful meditation, intentionally suppressing physical desire in favor of rational thought and thereby preparing themselves for exodus into a forced pastoral idyll. Aelita is forbidden to have sex, which would prompt her descent into irrational thought, but she is drawn to the Earthling scientist Los: “In your blood an ancient force is stirring–the red mystery, the desire to perpetuate life. Your blood is in revolt.” Finally she gives in to the Earthling, thereby assuring her death at the hands of the high priests, who will throw her into a pit of giant Martian spiders borrowed from Edgar Rice Burroughs. As Los and the blue-skinned Princess make love, the other Earthling, the Bolshevik revolutionary Gusev, travels to the city and meets a Martian worker, who sees in the earthlings a “fresh, hot-blooded race” that can save the Martians. Just as Los gives Aelita the gift of sexual passion and irrational chaos, Gusev gives the Martian proletariat a violent revolution.

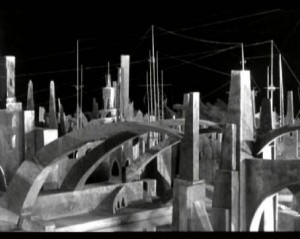

Martian City from film Aelita Queen of Mars (1924)

The Collective Hero & the Martian City

Soviet critics responded positively to Aelita, praising Gusev as the new Soviet hero. A strong, decisive man of action, Gusev immediately claims Mars for the Russian Federated Republic. Yet when the revolution he starts comes to a halt, he must fetch the intellectual Los from his spider-infested love nest to save the day. Gusev needs Los to guide him and to keep the revolution from descending into mindless destruction. Los in his turn needs Gusev, since only the presence of the simple man of action can draw him out of his continual state of angst. Los invented his spaceship to escape from his own suffering on Earth, but after traveling to Mars he starts to think about humanity’s needs more than his own and begins designing power plants for Earth based on Martian technology. Los now uses his science not to help himself but the entire planet. In transforming the angst-ridden self-centered Los into the selfless collective hero, the novel turns from escapist fantasy to Soviet utility, a blueprint for the construction of Soviet Science Fiction and the place of the intellectual in a post-revolutionary Soviet society.

The Princess of Mars on the Silver Screen

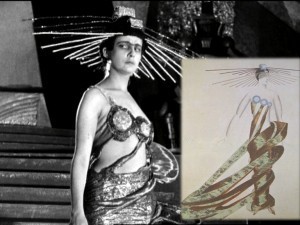

Costume for film Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924)

Although Tolstoy’s novel has been translated into English, Americans might be more familiar with the 1924 silent film Aelita: Queen of Mars which was based on the novel (Aelita becomes a queen, the film has a more developed Moscow plot, and the trip to Mars ends up being a dream). Directed by Yakov Protazanov, the film is best known for its wonderful constructivist sets and costumes designed by Aleksandra Ekster. The look of Martian society in Aelita has been seen to influence other futuristic films of the 1920s such as the Flash Gordon serials and Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis. Along with other products of the early Soviet avant-garde, however, Aelita soon fell out of favor. Until the end of the Cold War, most Russians knew the story not from the film but from the novel.

The Aelita Prize & the Tolstoy Crater

Aleksey Tolstoy Crater on Mars

The Aelita Prize

Tolstoy was later elected to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and became a member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Although he died in 1945, Tolstoy was recognized at the Nuremburg Trials for his early investigations into Nazi atrocities. He was also known as the father of Soviet Science Fiction, and scientists inspired by the novel named a crater on the planet Mars after Tolstoy. Since 1981 the annual Aelita Convention, a gathering of Science Fiction writers, scholars and fans, has been held in the city of Ekaterinburg, where the Aelita Prize is awarded to one Russian Science Fiction writer every year (http://www.rusf.ru/aelita/aelitaeng.html).

August 5, 2014

Private & Confidential: Female Spies of the Confederacy

At Wonders & Marvels, our inaugural Books We Love feature has allowed us to indulge our passion for espionage. Last week began with dossiers on two female Union spies who play a central role in Karen Abbott’s Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy — and today we continue by featuring profiles of her major female Confederate spies. So satisfy your curiosity by reading on, and be sure to join us for this week’s giveaway as well (see below).

Confederate Operative:

Belle Boyd

NAME: Belle Boyd

ALIAS: “The Siren of the Shenandoah”; “The Secesh Cleopatra”; and, in Paris, “La Belle Rebelle”

BORN: May 1844, Shenandoah Valley, Virginia

AFFILIATION: Confederate spy

MARITAL STATUS: Resolutely unattached. Operative was said to be engaged to one Dr. Cherry, a wealthy soldier from Mississippi, but wedding never transpired. Since then, she’s been linked to Union General James Shields and Major Dick Long of the Seventy-Third Ohio. She has a particular affection for Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, desiring to “occupy his tent and share his dangers.”

BACKGROUND: On July 1, 1861, this 17-year-old operative shot a Union soldier who threatened to raise a flag over her home. She then became a courier and spy for the rebel army, and is often spotted wandering through Union camps, wheedling information from federal officers. Contemporaries have deemed her “perfectly insane” and “the fastest girl in Virginia—or anywhere else for that matter.”

SKILLS AND CIRCUMSTANCES

• Operative conceals dispatches under a false dog skin, cut precisely to fit over her pet’s body.

• It is believed operative obtained top-secret information by eavesdropping on a Union war council. In May 1862, at the Battle of Front Royal, she ran onto the field and into gunfire, bullets tearing the hem of her skirt, to deliver a message to Stonewall Jackson.

• Detective Allan Pinkerton is conducting surveillance on operative in the hope of entrapping her.

IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

• Operative sometimes dresses as a man, donning the gray wool frock coat and butternut kepi of a rebel private. When she does wear a riding dress she is known to show off her legs, described as “the best in the Confederacy.”

• Operative is also described as having “large teeth” and a “loud, coarse laugh.” Certain journalists call her the “camp Cyprian” who has “passed the first freshness of youth.”

• Operative has violent tendencies, once instigating a knife fight between two Confederate regiments. It is reported she also dropped a brick on a prison guard’s head.

Confederate Operative:

Rose Greenhow

NAME: Rose O’Neal Greenhow

ALIAS: “Rebel Rose”

BORN: 1813 or 1814, Montgomery County, Maryland

AFFILIATION: Confederate spymaster

MARITAL STATUS: Widowed. Her deceased husband had been a high-ranking official at the state department for more than 20 years, allowing Rose to develop relationships with numerous powerful politicians, both Democrat and Republican. Five of her eight children died, one shortly before Lincoln’s inauguration. One daughter, eight-year-old “Little Rose,” still lives at home with her in Washington, DC.

BACKGROUND: In spring 1861, a Confederate captain asked Greenhow to form a spy ring, which she runs from her home near Lafayette Square—“within easy rifle range of the White House,” as one rebel general observed. She counts among her sources (and conquests) several Northern politicians, including an abolitionist Republican who serves as Lincoln’s chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs. “You know that I do love you,” read one love letter. “I am suffering this morning. In fact, I am sick physically and mentally and know nothing that would sooth me so much as an hour with you.”

SKILLS AND CIRCUMSTANCES

• Operative provided crucial information to the Confederate army before the First Battle of Bull Run, hiding the dispatch in a 16-year-old courier’s hair.

• Operative uses her daughter in her spying exploits, tucking messages in Little Rose’s pantalets and sending her out to the yard to meet Confederate “scouts.”

• Detective Allan Pinkerton has begun a dossier on her, and notes that she uses her “almost irresistible seductive powers” to aid the rebels.

IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

• Seven years after her husband’s death, operative still dresses in mourning, wearing heavy black silk. She can be spotted daily on Capitol Hill, watching Union general George McClellan drill his troops and scribbling in a brown leather diary.

• Operative is an expert seamstress and stitches dispatches, maps of Union fortifications, and other contraband into the lining of her gowns.

• Operative is a virulent racist, and alternately calls Lincoln “beanpole” and “Satan.”

• It is believed that rebel president Jefferson Davis plans to send her to Europe to lobby on behalf of the Confederacy.

Now that you’ve had a chance to meet the women of the Union and the Confederacy, we’d love to know: Who’s Your Favorite Spy?

Spy vs. Spy Fan Favorite Poll

To enter, cast your vote on Twitter by including

Your spy’s Name & Dossier web url (Union / Confederate)

#LTSS

(You may also vote in the Comments section below)

Subscribers to Abbott’s weekly newsletter “Secrets & Spies: A Peek into LTSS” will win a Teaser Chapter on the Winning Spy.

So if you’d like to learn more about the dangerous world of Civil War espionage — and hear some of the salacious tales surrounding these women — be sure to Cast Your Vote by 11:00pm EST on August 16 and Subscribe to the newsletter below.

Subscribe to our Features

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

Subscriptions

Weekly Feature: Liar Temptress Soldier Spy

Wonders & Marvels Monthly

August 4, 2014

Spartans vs the Women of Argos

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

King Cleomenes and the Spartans thought their war against Argos was over. Victory was theirs! The Argive army was decimated and a few survivors had fled the battlefield into a sacred grove for refuge. Those men were easily wiped out–burned alive when the Spartan soldiers set fire to the pine trees. Now all that remained was to march on Argos and take over the city so renowned for music and poetry.

King Cleomenes and the Spartans thought their war against Argos was over. Victory was theirs! The Argive army was decimated and a few survivors had fled the battlefield into a sacred grove for refuge. Those men were easily wiped out–burned alive when the Spartan soldiers set fire to the pine trees. Now all that remained was to march on Argos and take over the city so renowned for music and poetry.

The battle (about 510-494 BC) was celebrated in Greek art and literature. According to legendary accounts recorded by Herodotus, Pausanias, and Lucian, the Argive women saved their city from the Spartan attack. Inside the city walls, a distinguished poetess named Telesilla took charge. She sent old men, young boys, and household slaves to man the walls. Meanwhile she and the women of Argos snatched up weapons and armor from houses and temples. Dressed in men’s clothes, the women massed where the Spartans were beginning the final assault. Resolute and unfazed by the Spartans’ terrifying battle cries, the women met the Spartan charge with valor, stood their ground, and fought back with surprising strength.

Now Cleomenes and his men faced a dilemma. It would be an inglorious kind of victory if they slaughtered such brave women. But on the other hand, what a shameful disaster it would be if crack Spartan warriors somehow failed to defeat the women.

The Spartans withdrew and yielded the battle to Telesilla and her forces.

Because of the women’s victory, it was said that the women of Argos worshipped Ares, the god of war. Writing about 600 years after the battle, Pausanias visited Argos and described a relief near the theater and sanctuary of Aphrodite honoring Telesilla as the poetess-warrior. She was depicted donning a helmet, with her poetry books lying at her feet. That sculpture no longer exists but tiny fragments of Telesilla’s poetry do survive; it seems that she wrote songs for girls and poems on mythic topics. Given the Amazon-like courage of Telesilla and her female recruits, perhaps it is no surprise that the beautiful head of an Amazon, pictured above, was made in Argos in the late fifth century BC.

–Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014)

August 3, 2014

Book Club Giveaways

Here at W&M, one of the best parts of our jobs is connecting talented historians with brilliant readers. It’s part and parcel of a “community for the curious”!

Here at W&M, one of the best parts of our jobs is connecting talented historians with brilliant readers. It’s part and parcel of a “community for the curious”!

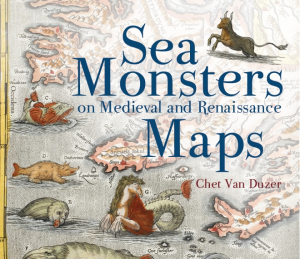

August is an exciting month, given that we had a chance to talk to Beth Tobin about the Duchess of Portland’s shell collection, to Miles Unger about the “modern” qualities of Michelangelo’s work, and to Chet Van Duzer about sea monsters. It’s the kind of diversity every month should have.

We’re also excited that all three of our featured authors are doing giveaways of their upcoming book releases. Interested in getting free copies? (We hope so! We loved ours.) All you need to do is sign up for the giveaway(s) of your choice below. When you do, you’ll be  entered in a drawing to win hat book. You’ll also be subscribed to the W&M Monthly Newsletter, which is chock-full of updates, articles, and other contests so you don’t miss a thing.

entered in a drawing to win hat book. You’ll also be subscribed to the W&M Monthly Newsletter, which is chock-full of updates, articles, and other contests so you don’t miss a thing.

Thanks for joining us!

Subscribe to our Giveaways!

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

August Book Giveaways

Beth Fowkes Tobin, “The Duchess’s Shells”

Miles Unger, “Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces”

Chet Van Duzer, “Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps”

August 2, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. ix

When was the last time you appreciated the difference that semantics make? This week, our Cabinet of Curiosities reveals that historians have been obsessing over brains and vascular pumps as much as we have over minds and hearts.

When was the last time you appreciated the difference that semantics make? This week, our Cabinet of Curiosities reveals that historians have been obsessing over brains and vascular pumps as much as we have over minds and hearts.

In Norway, archaeologists have uncovered an 8,000 year old skull. Given its small size, they believe it belonged to an infant — and while the fragments were fragile, they contained brain matter that’s exciting the scientists involved.

Archaeologists have been busy in Scotland as well. Following up on the discovery of a 14th century graveyard in Edinburgh five years ago, a research team is reporting that the high number of specimens recovered in that one spot have allowed them to track medieval mortality rates, average heights, and common causes of death. The team has also performed some facial reconstruction studies on the bones to see how individuals may have looked.

Over at the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Collation, the archivists walked us through the cerebral puzzle of early print signatures–the markers that printers used when putting together texts.

In honor of the 300th anniversary of the death of Queen Anne, History of Parliament reminded readers about the tangled blood lines and family tensions that not only shaped England, but that affected royal lines throughout Europe. Further attention to British royalty this week emphasized the vanity of kings — as evidenced by the beard-growing rivalry that existed between Henry VIII and Francis I.

This week in history, Cyrano de Bergerac, famed dramatist and duelist, died in 1655 at the age of 36. A known satire, he has become best known in literature for his allegedly large nose and his romanticized reputation as the hidden lover of Roxanne.

Finally, the Smithsonian marked 100 years since WWI by examining the propaganda posters that pushed the US out of isolationism and into international involvement. The images and analysis reveal how advertising can stir the hearts and minds of viewers, for better or worse.

Interested in our fascinations–or inclined to share your own? Leave Comments for us below, or join us on Twitter!

If that’s not enough to satisfy your historical cravings, join in on our features by subscribing to Wonders & Marvels below.

Subscribe to our Features

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

August 1, 2014

The Random Researcher: Wanderlust

It’s now August – which for students, teachers, and professors signals impending fall and incites a desire to cram in as much end-of-summer activity as possible into the schedule. For us at Wonders & Marvels, we feel that same press; and the late summer inspires us with a certain kind of wanderlust. Our reading lists turn to travel and adventure, we plan last minute research trips and family vacations, and we grow nostalgic for the bright days of May.

It’s now August – which for students, teachers, and professors signals impending fall and incites a desire to cram in as much end-of-summer activity as possible into the schedule. For us at Wonders & Marvels, we feel that same press; and the late summer inspires us with a certain kind of wanderlust. Our reading lists turn to travel and adventure, we plan last minute research trips and family vacations, and we grow nostalgic for the bright days of May.

Highly likely our readers share this in common with us. And, because we are all part of the same curious community, it’s also likely that these rituals inspire similar questions. Questions such as

Where did people vacation in 18th century England? And why did they choose certain vacation spots?

The archives are chock full of information about travel from the period — from postcards, letters, and journal entries, to maps and brochures. Even contemporary novels were ready to satisfy English readers’ wanderlust. And while your class rank, income, and gender largely shaped the answers to the questions above, there were a couple of common trends for how individuals and families might plan their trips. Here, we take an admittedly brief glimpse into holiday travel from another time.

Educational Travel

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, The Grand Tour led elite young Englishmen out of London and into Continental cities such as Paris,  Munich, Amsterdam, Madrid, Prague, and Vienna. Aimed at helping young men to “broaden [their] education, mark the end of childhood, and acquire and hone social graces,” such tours were also an opportunity for families to display wealth and solidify political and economic reputations beyond England, as their sons might be abroad anywhere from one to five years (1).

Munich, Amsterdam, Madrid, Prague, and Vienna. Aimed at helping young men to “broaden [their] education, mark the end of childhood, and acquire and hone social graces,” such tours were also an opportunity for families to display wealth and solidify political and economic reputations beyond England, as their sons might be abroad anywhere from one to five years (1).

While a young man’s Tour would differ based on the educational plan set forth for him, the first step would be a crossing from Dover to Calais. The distance of approximately 83 kilometers could take anywhere from 3 to 12 hours to cross by ferry or packet ship, depending on weather and water conditions (2). What’s more, departing or arriving at port was made dangerous by shallow, rocky waters and a lack of landings — which required travelers to disembark their ships (luggage and all) using small row boats.

Restorative Travel

Travel for health was also popular and common during the period, with the fashionable English choosing spa and sea-batching destinations such as Bath or Brighton.

While the thermal waters of Bath made it recommendable to those suffering from a variety of health problems (including gout), its popularity as a vacation spot also stemmed from its architecture and related social calendar of balls, concerts, and exhibitions. Following its erection the 1706 (and later reconstruction in 1795), the town’s Pump Room became host to assemblies, defined generally by the meeting “of polite persons of both sexes for the sake of conversation, gallantry, news and play” (3). Such gatherings provided lush spectacle, as women paraded in their finest in view of other elite visitors.

While the thermal waters of Bath made it recommendable to those suffering from a variety of health problems (including gout), its popularity as a vacation spot also stemmed from its architecture and related social calendar of balls, concerts, and exhibitions. Following its erection the 1706 (and later reconstruction in 1795), the town’s Pump Room became host to assemblies, defined generally by the meeting “of polite persons of both sexes for the sake of conversation, gallantry, news and play” (3). Such gatherings provided lush spectacle, as women paraded in their finest in view of other elite visitors.

For the wealthy at least, transit to Bath involved carriage rides across a system of roads made dangerous by highwaymen who lay in wait for wealthy passengers. Carriages might range from private chariots, chases, and gigs to the more common and larger sized for-hire Royal Mail Coach or stage coach.

Sources:

(1) Ueli Gyer, “The History of Tourism: Structures on the Path to Modernity,” European History Online 3 Dec 2010.

(2) “The Grand Tour,” Georgian Index May 2011.

(3) “Georgians: Dress for Polite Society,” Fashion Museum, Bath & Northeast Somerset Council 2014.

From the Archives: Wanderlust

It’s now August – which for students, teachers, and professors signals impending fall and incites a desire to cram in as much end-of-summer activity as possible into the schedule. For us at Wonders & Marvels, we feel that same press; and the late summer inspires us with a certain kind of wanderlust. Our reading lists turn to travel and adventure, we plan last minute research trips and family vacations, and we grow nostalgic for the bright days of May.

It’s now August – which for students, teachers, and professors signals impending fall and incites a desire to cram in as much end-of-summer activity as possible into the schedule. For us at Wonders & Marvels, we feel that same press; and the late summer inspires us with a certain kind of wanderlust. Our reading lists turn to travel and adventure, we plan last minute research trips and family vacations, and we grow nostalgic for the bright days of May.

Highly likely our readers share this in common with us. And, because we are all part of the same curious community, it’s also likely that these rituals inspire similar questions. Questions such as

Where did people vacation in 18th century England? And why did they choose certain vacation spots?

The archives are chock full of information about travel from the period — from postcards, letters, and journal entries, to maps and brochures. Even contemporary novels were ready to satisfy English readers’ wanderlust. And while your class rank, income, and gender largely shaped the answers to the questions above, there were a couple of common trends for how individuals and families might plan their trips. Here, we take an admittedly brief glimpse into holiday travel from another time.

Educational Travel

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, The Grand Tour led elite young Englishmen out of London and into Continental cities such as Paris,  Munich, Amsterdam, Madrid, Prague, and Vienna. Aimed at helping young men to “broaden [their] education, mark the end of childhood, and acquire and hone social graces,” such tours were also an opportunity for families to display wealth and solidify political and economic reputations beyond England, as their sons might be abroad anywhere from one to five years (1).

Munich, Amsterdam, Madrid, Prague, and Vienna. Aimed at helping young men to “broaden [their] education, mark the end of childhood, and acquire and hone social graces,” such tours were also an opportunity for families to display wealth and solidify political and economic reputations beyond England, as their sons might be abroad anywhere from one to five years (1).

While a young man’s Tour would differ based on the educational plan set forth for him, the first step would be a crossing from Dover to Calais. The distance of approximately 83 kilometers could take anywhere from 3 to 12 hours to cross by ferry or packet ship, depending on weather and water conditions (2). What’s more, departing or arriving at port was made dangerous by shallow, rocky waters and a lack of landings — which required travelers to disembark their ships (luggage and all) using small row boats.

Restorative Travel

Travel for health was also popular and common during the period, with the fashionable English choosing spa and sea-batching destinations such as Bath or Brighton.

While the thermal waters of Bath made it recommendable to those suffering from a variety of health problems (including gout), its popularity as a vacation spot also stemmed from its architecture and related social calendar of balls, concerts, and exhibitions. Following its erection the 1706 (and later reconstruction in 1795), the town’s Pump Room became host to assemblies, defined generally by the meeting “of polite persons of both sexes for the sake of conversation, gallantry, news and play” (3). Such gatherings provided lush spectacle, as women paraded in their finest in view of other elite visitors.

While the thermal waters of Bath made it recommendable to those suffering from a variety of health problems (including gout), its popularity as a vacation spot also stemmed from its architecture and related social calendar of balls, concerts, and exhibitions. Following its erection the 1706 (and later reconstruction in 1795), the town’s Pump Room became host to assemblies, defined generally by the meeting “of polite persons of both sexes for the sake of conversation, gallantry, news and play” (3). Such gatherings provided lush spectacle, as women paraded in their finest in view of other elite visitors.

For the wealthy at least, transit to Bath involved carriage rides across a system of roads made dangerous by highwaymen who lay in wait for wealthy passengers. Carriages might range from private chariots, chases, and gigs to the more common and larger sized for-hire Royal Mail Coach or stage coach.

Sources:

(1) Ueli Gyer, “The History of Tourism: Structures on the Path to Modernity,” European History Online 3 Dec 2010.

(2) “The Grand Tour,” Georgian Index May 2011.

(3) “Georgians: Dress for Polite Society,” Fashion Museum, Bath & Northeast Somerset Council 2014.

July 30, 2014

King James I: Demonologist

By Mary Sharratt (Guest Contributor)

Even by the standards of his age,” King James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, stood out as a deeply superstitious man, obsessed with the occult.

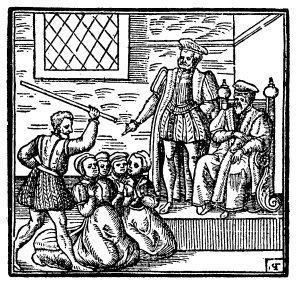

Before his reign, witchcraft persecutions had been rare in Britain. But that all changed in 1590 when James personally oversaw the trials by torture for around seventy individuals implicated in the North Berwick Witch Trials, the biggest Scotland had known. Their alleged crime? Raising a storm which nearly sank James’ ship when he sailed home from Norway with his new bride, Anne of Denmark. The trial resulted in possibly dozens of people burned at the stake, although the precise number is unknown.

In 1597, James published Daemonologie, his rebuttal of Reginald Scot’s skeptical work, The Discoverie of Witchcraft, which questioned the very existence of witches. Daemonologie was an alarmist book, presenting the idea of a vast conspiracy of satanic witches threatening to undermine the nation.

In 1604, only one year after James ascended to the English throne, he passed his new Witchcraft Act, which made raising spirits a crime punishable by execution.

James’ ideas on witchcraft were later popularized by Shakespeare’s play Macbeth, performed for James’s court in 1606. For the first time in history, English drama depicted witches gathering in secret for their own malign scheming. According to Instruments of Darkness by James Sharpe, this terror of supposed witch covens was the driving factor mobilizing 17th century witch hunts.

In 1612, the King’s paranoid fantasy of satanic conspiracy, planted in the minds of local magistrates eager to win his favor, culminated in one of the key manifestations of the Jacobean witch-craze—the trials of the Lancashire Witches, accused of plotting to blow up Lancaster Castle with gunpowder. Eight women and two men were executed.

James’s legacy extends even into our age. The King James Bible, completed in 1611, saw the scriptures rewritten to further the King’s agenda. Exodus 22:18, originally translated as, “Thou must not suffer a poisoner to live,” became “Thou must not suffer a witch to live.”

Further reading:

The Lancashire Witches: Histories & Stories, Robert Poole, ed, Manchester University Press, 2002.

Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England, 1550-1750, James Sharpe, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Mary Sharratt is the author of Daughters of the Witching Hill

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April, 2010), a novel based on the true and heartbreaking story of the Pendle Witches of 1612. She lives at the foot of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, England. To read more about her, click here.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April, 2010), a novel based on the true and heartbreaking story of the Pendle Witches of 1612. She lives at the foot of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, England. To read more about her, click here.This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 14 April 2010.

IMAGE: illustration from the original document, The News from Scotland, about the trial of the Witches of North Berwick

Congratulations to the following winners:

DaintyBallerina, Gian T., and Paul M.,

We’ll be in touch real soon!

July 29, 2014

Private & Confidential: Female Spies of the Union

Are you as obsessed with spies as we are? As we admitted on Sunday, here at W&M we can’t get enough intrigue. To satisfy our curiosity, we’ve teamed up with regular contributor Karen Abbott to access the world of Civil War espionage through the lives of the four female characters in her upcoming book Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy. Today, Abbott opens the dossiers on women of the Union, and at the end, we’re opening up a Giveaway. Read on…

Union Operative: Elizabeth Van Lew

NAME: Elizabeth Van Lew

ALIAS: “My Dear Aunt” or “My Dear Niece” (in espionage correspondence); “Crazy Bet”

BORN: October 15, 1818,Richmond, Virginia

AFFILIATION: Union spymaster

MARITAL STATUS: Single; fiancé died during the yellow fever epidemic in 1841. Known “spinster” who lives with her mother, brother, and Confederate-sympathizing sister-in-law in Church Hill.

BACKGROUND

A wealthy Southerner with Yankee roots,she grew up under an abolitionist governess. After the death of her father, a businessman and slave owner, she began “hiring out,” a practice in which slaves could keep a percentage of their wages to purchase their freedom. Elizabeth also spent some of her inheritance buying slaves to free them. “From what I have seen of the management of the Negroes of the place,” one neighbor reports, “the family of Van Lews are, I am satisfied, genuine abolitionists.”

SKILLS AND CIRCUMSTANCES

• Operative uses a pin to “prick” letters in books, forming questions that communicate to and are answered similarly by Union prisoners. She also hides correspondence and money in an antique plate warmer.

• Operative is rumored to aid in the escape of Union prisoners, hiding them in a secret room in her mansion until she can arrange to get them to Union lines.

• It is believed that Union General Benjamin “Beast” Butler formally recruited her and gave her a cipher and invisible ink, called “S.S. Fluid,” which becomes visible with the application of milk or tannic acid.

IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

• Operative is invariably described as “nervous” and “birdlike,” and, according to one contemporary, “never as pretty as her portrait shows.”

• She sometimes dresses in disguise, wearing a homespun dress, coarse cotton bonnet, and cotton in her cheeks.

Union Operative:

Emma Edmonds

NAME: Sarah “Emma” Edmonds

ALIAS: Private Franklin “Frank” Thompson

BORN: December 1841,New Brunswick, Canada

AFFILIATION: Union army, Company F, 2nd Michigan Infantry

MARITAL STATUS: Single. Suspected paramours include Private Jerome Robbins, 2nd Michigan Infantry, and Lieutenant James Reid, Seventy-ninth New York Highlanders—the only men who know her true identity.

BACKGROUND

In 1859, this Union operative fled her family farm in Canada to avoid an arranged marriage. Exchanging her crinoline and bonnet for trousers and a shirt, she became a Bible salesman, migrating to the U.S. A devout Christian, she could not abide slavery and decided to fight for the Union.

SKILLS AND CIRCUMSTANCES

• Operative, who believes she has a “magnetic power” to “soothe the delirium,” initially worked solely as an army nurse.

• Operative is known to excel at subterfuge and disguises including a male slave, an Irish peddler woman, a female slave, and a male Confederate civilian. At the behest of Union General George McClellan, she often infiltrates rebel territory, noting troop numbers and sketching fortifications.

IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

• Operative was interviewed and examined by Union generals in the spring of 1862, and found to have the head of a man, with “largely developed” organs of secretiveness and combativeness.

• Operative contracted malaria during the Peninsula Campaign and is at risk of a relapse. It is believed she would avoid medical treatment rather than risk being discovered.

Titillated? Certainly we are. And we’d love for you to join in discussion about these women’s exploits.

To kick things off, Abbott and W&M are hosting a limited Giveaway of a Civil War Token and 2 Sets of Civil War Playing Cards open to newsletter subscribers. To enter, sign up below for the Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy newsletter. Entry period ends August 5 at 11:00pm EST.

LTSS Subscribers will have access to a fan favorite poll and another exciting giveaway.

Subscribe to our Features

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

Subscriptions

Weekly Feature: Liar Temptress Soldier Spy

Wonders & Marvels Monthly

July 28, 2014

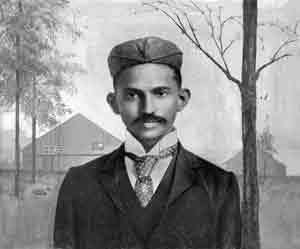

How Gandhi Became Gandhi

The first volume of what may well be the definitive biography of Mohandas Gandhi, Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India covers the years from Gandhi’s birth in 1869 through his departure from South Africa in July, 1914.

Biographers have often treated Gandhi’s earlier life– especially his two decades working in South Africa–as a warm-up for leading the struggle for Indian independence. Guha gives this period serious and detailed attention, arguing that such attention is necessary if we are to understand both “how the Mahatma was made” and Gandhi’s critical role in South African history.

Even a reader who is familiar with Gandhi’s history will find new insights in Gandhi Before India. Guha not only draws on Gandhi’s own writings from and about this period, but also uses a wide range of contemporary sources, from Gandhi’s childhood school reports to secret files kept by South African officials. By focusing on contemporary records rather than retrospective accounts, he overturns some accepted “truths” and introduces new elements to a familiar story. Perhaps the most interesting parts of the book are the side excursions that illuminate elements of Gandhi’s life: the British ranking Indian rulers, the history of vegetarianism in England, Johannesburg as a cultural and intellectual melting pot.

Gandhi Before India is a step-by-step account of how an uninspiring member of a Gujurati merchant caste transcended the conventions of his caste, class, religious and ethnic backgrounds to become one of the most important–and controversial–figures of the twentieth century.

This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers

Photograph courtesy of http://www.resurgence.org. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons