Holly Tucker's Blog, page 50

August 14, 2014

The Random Researcher: The Happiest of Hours

Last week, we considered the collegiate fashions of the 12th century. Now, as we encounter another Friday and approaching weekend, our attention is locked onto happy hour. Are we alone in thinking that this happiest of weekday hours also has the potential for deep conversations and random questions? As we pour ourselves one, we have to wonder:

Last week, we considered the collegiate fashions of the 12th century. Now, as we encounter another Friday and approaching weekend, our attention is locked onto happy hour. Are we alone in thinking that this happiest of weekday hours also has the potential for deep conversations and random questions? As we pour ourselves one, we have to wonder:

What is the origin of the happy hour cocktail?

“Cocktail” or Not?

To begin with, a good barfly should know what kind of drink she is ordering as she approaches the bar. What defines a “cocktail”?

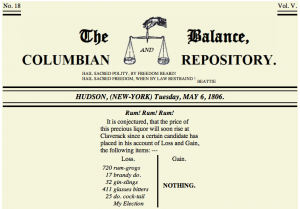

The term first appeared in print in “The Balance and Columbian Repository” of New York on May 6, 1806 — and the article provided no definition. Rather, a political candidate who had lost the election provided a satirical itemized list of his campaign losses, including “411 glasses bitters, 25 do. cock-tail, My Election” (1). Approximately a week later, the paper’s editor responded to a confused reader who had asked “will you be so obliging as to inform me what it meant by this species of refreshment?”

The answer?

“As I make it a point, never to publish anything (under my editorial head) but which I can explain, I shall not hesitate to gratify the curiosity of my inquisitive correspondent: Cock tail, then, is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water and bitters it is vulgarly called a bittered sling” (1).

The modern cocktail remains close to its 1806 roots. Different from a shot, martini, or blended drink, it is a short drink composed of a liquor combined with a juice or sugar based mixer.

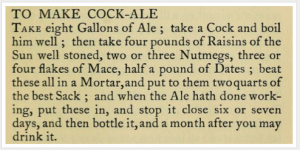

While the exact etymology of the term remains unknown, our managing editor’s favorite possibility is that it derives from an early drink called “cock ale” that was popular in English huswifery manuals and receipt books of the 16th and 17th centuries (2).

But What About the Happy Hour?

Regardless of what you drink at happy hour — and the trends have changed across time — we also need to consider the origins of the gathering time itself.

As with the most interesting parts of our past, the exact beginnings of “happy hour” are difficult to pin down because they were sociable, communal, and oral. Many scholars believe that the actual term “happy hour” was appropriated from U.S. naval practice in 1920s. In order to assist seamen in releasing energy while on ship, the Navy sanctioned at this time a daily “happy hour” for wrestling, boxing, and other physical entertainment.

On land, Prohibition was shaping American drinking culture, and the expression became a euphemism for illegal drinking in the period between the end of the workday and the return to domestic life (3).

Hooked? Join in For More!

Tell us what you think or what other questions you might have in the Comments below or on Twitter. But first, subscribe to our features below so that you don’t miss a single quirky minute.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

Resources:

(1) “The Origin of the Cocktail,” The Museum of the American Cocktail 2007.

(2) Kenelm Digby, “The Closet of the Eminently Learned Kenelme Digbie” (London, 1669).

Joel A. Klein, “Cock Ale: A Homely Aphrodisiac,” The Recipes Project 14 January 2014.

(3) Johnny Acton et. al. The Origin of Everyday Things (Sterling, 2006), 107.

August 13, 2014

Tales of the Blockade Runners

Nina (left) and Lucy Ann, two dolls that may have been used to smuggle quinine during the Civil War.

by Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

In April 1861, as soon as President Lincoln declared a blockade of 3,500 miles of coastline in an attempt to cut off the Confederacy’s overseas trade, savvy Southerners found ways to evade it. England, which remained neutral, allowed agents to buy at will, and a blockade-running business flourished abroad. Low, sleek ships like the Bermuda set sail from Liverpool and broke the cordon, slipping into the wharf at Savannah with a million-dollar cargo: cannon, rifles, cartridges, gunpowder, shoes, blankets, morphine, and ever-valuable quinine, which was used to treat malaria. Domestically, two Philadelphia-based, politically connected chemical manufacturing companies, Powers Weightman and Rosengarten Sons, supplied quinine to Union troops, but employees who valued profit over patriotism or sympathized with the South were always eager to make a deal.

Smugglers and spies swarmed the towns along the Potomac River, a burgeoning network that linked rebels in Virginia and Maryland, the latter a tobacco-producing border state with a significant slave population. Despite constant patrolling by the federal navy, hundreds of rebels crossed the river at Pope’s Creek, where the water stretched fewer than two miles wide. A farmer named Thomas A. Jones—who would aid John Wilkes Booth’s escape in 1865—lived on the Maryland side. He had calculated a sliver of time, just before dusk, when the sun grazed the high bluffs above Pope’s Creek and threw a shadow across the river, enabling small rowboats to land and hide without detection.

Jones cooperated closely with Benjamin Grimes, a fellow farmer on the Virginia side, and together they orchestrated at least two crossings a night—some of them conducted by nine-year-old Robert Fitzgerald, the father of the future writer. Boats set sail from Grimes’s property, deposited packages in the fork of a dead tree on Jones’s shore, and collected packages from the same spot if, for some reason, Jones himself was not standing on the beach waiting with them in hand. When it wasn’t safe for a boat to cross from Virginia, Miss Mary Watson, the 24-year-old daughter of a Confederate major, sent a signal by draping a black shawl from the window of her home.

Women proved to be some of the most dependable and daring blockade runners. One managed to conceal inside her hoop skirt a roll of army cloth, several pairs of cavalry boots, a roll of crimson flannel, packages of gilt braid and sewing silk, cans of preserved meats, and a bag of coffee—the contraband tally for a single crossing. Another found a functioning pistol on a battlefield, took it apart, and endeavored to smuggle the pieces to a rebel solider. She hid the two halves of the wooden butt in between soft ginger cookies, pushed the barrel into a loaf of bread, and buried the screws in a jar of potted shrimp, also filched from a Union officer. Large quantities of quinine passed through, sometimes packed in sacks of oiled silk and tucked inside the hollowed, papier-mâché heads of children’s dolls.

As the war progressed the blockade had its intended effect, interrupting business and choking the Confederacy of supplies. No one could receive checks or access funds held in northern banks. Coffee was a luxury good. Atlanta jewelers set coffee beans instead of diamonds in breast pins, and newspapers printed suggestions for ersatz brews: take the common garden beet, wash it clean, dice into small pieces, roast in the oven and grind, boil with a gallon of water, settle with an egg. Newspapers dealt with shortages by printing on wallpaper, wrapping paper, and the backs of business forms. Textbooks became an entrepreneurial enterprise and adopted a decidedly local flavor. One arithmetic book posed the problem: “If one Confederate soldier kills 90 Yankees, how many Yankees can 10 Confederate soldiers kill?”

Ultimately it was the occupation of the Confederate ports, rather than the vigilant watch kept by federal cruisers, that stopped the blockade runners. Union capture of Mobile Bay in August 1864 closed what was virtually the last port on the Gulf. Charleston and Wilmington, the South’s last ports on the Atlantic Coast, fell in early 1865, and the Confederacy was finally starved into submission.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, her forthcoming book about female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins on September 2.

Sources:

Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1988; author interview with Catherine Wright, curator of the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, VA.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 January 2013.

.

Origins of the “Secesh Cleopatra”

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

Oddly Conspicuous

It was an oddly conspicuous act for a girl purporting to be a spy: On May 23, 1862, Belle Boyd, newly 18 and possessed of a “little rebel heart,” sprinted across the battlefield in Front Royal, Va., crinoline swinging, bullets plowing up the earth around her. She waved her white bonnet in grandiose loops, a signal for Confederate troops to advance, and caught the attention of staff officer Henry Kyd Douglas.

“It took only a few minutes for my horse to carry me,” Douglas wrote, “to meet the romantic maiden whose tall, supple, and graceful figure struck me as soon as I came in sight of her.” Speaking in gasps, Belle said she had vital intelligence for General Stonewall Jackson: the Union had only 1,000 men at Front Royal under Colonel John Kenly, but forces in the adjacent towns of Strasburg, Winchester and Harpers Ferry could easily unite and set a trap. If Jackson charged down quickly, he could catch them all. “I must hurry back,” Belle said, and blew Douglas a kiss. “Goodbye. My love to all the dear boys.”

The Confederate victory at Front Royal was a minor incident in Jackson’s legendary Valley Campaign, waged throughout the spring of 1862 in the crucial territory between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains, but it brought immediate national fame to the teenager who thrust herself, literally, into the heat of battle. Although Jackson might have already possessed the intelligence Boyd risked her life to deliver, as some historians suggest, she became one of the most controversial and enigmatic figures of the war, a fervent secessionist whose efforts on behalf of the Confederacy evoked admiration and derision, in equal parts.

No one knew quite what to make of this “Siren of the Shenandoah,” this “Belle Rebelle,” this “Secesh Cleopatra,” this “Pet of the Confederacy” — monikers whose hyper-femininity discounted the complexity of Boyd’s career and her carefully constructed persona, both of which have been debated, to little consensus, since the publication of her memoir in 1865. Was Belle Boyd a heroine or a clever charlatan? A thrill-seeking opportunist or a brave Confederate patriot? The Civil War’s most overrated spy, or, as Carl Sandburg wrote, someone who “could have been legally convicted, shot at sunrise, and heard of no more?” Such rhetorical musings, while contributing to her myth, also miss the point of why it has endured; Belle Boyd isn’t remembered today for the efficacy of her spying, but for the way she went about it.

Origins

Belle Boyd was born in May 1844 in Bunker Hill, Va. (now West Virginia), the oldest of eight children and the daughter of a shopkeeper, Benjamin Boyd, who enlisted in the Second Virginia Infantry, part of the Stonewall Brigade. When Belle was 10 the family moved to nearby Martinsburg with their six slaves, one of whom, Eliza Corsey, became Belle’s close companion and sometime accomplice in her espionage adventures. Every night, by candlelight, Belle defied the law and taught Eliza to read and write. “Slavery, like all other imperfect forms of society, will have its day,” Belle wrote, “but the time for its final extinction in the Confederate States of America has not yet arrived.”

At age 11, according to family lore, Belle protested her exclusion from an adult dinner party by riding her horse into the dining room and asking, “Well, my horse is old enough, isn’t he?” The following year she attended Baltimore’s Mount Washington Female College, where young Southern women “of gentle birth” were “trained to place proper reliance on their own powers.” After her formal societal debut in Washington, she returned to the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1861, shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter.

Three months later, on July 4, Union forces under General Robert Patterson captured Martinsburg, ransacking local homes and business in the process. One particularly drunken and unruly group invaded the Boyd home and tried to raise a Yankee flag over its door. At this, Belle’s mother, Mary Boyd, stepped forward. “Men,” she said, “every member of my household will die before that flag shall be raised over us.” When one soldier, 25-year-old Frederick Martin of the Seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers, physically threatened Mary, Belle took a Colt 1849 pocket pistol and shot him dead. She was cleared of all wrongdoing but found herself consumed by “thoughts and plans of vengeance.” This served to open the door to her becoming an infamous Confederate courier and spy.

Interested in learning more about Belle Boyd and the female spies of the Civil War?

Subscribe to “Secrets & Spies” —

Abbott and W&M’s Books We Love Newsletter.

Email Address *

First Name

Subscriptions

Weekly Feature: Liar Temptress Soldier Spy

Wonders & Marvels Monthly

** This post is drawn from “The Siren of the Shenandoah,” Disunion 23 May 2012.

August 12, 2014

The Duchess’s Shells

By Beth Tobin (Guest Contributor)

+ Giveaway Below

The Duchess, illustration by Lauren Nassef

An Incredible Cache

When Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland, one of Britain’s wealthiest women, died in 1785 at the age of 70, the London newspapers were filled with gossip about her will, her heirs, and what would happen to her extensive collections of decorative and natural objects. She had collected objects of great beauty and rarity– Japanese porcelain, French snuffboxes, Italian cameos, Roman statuary and other antiquities–but her great love was natural history. She collected minerals, fossils, insects, corals, and lots and lots of shells. When the news soon spread that all would be sold at auction, rumors circulated about her having bankrupted herself purchasing natural history specimens and objets d’art and the need for an auction to refill the ducal coffers. These rumors proved to be untrue; she had simply stipulated in her will that the auction’s proceeds were for the benefit of her younger children as her first son would inherit her several residences and estates. The auction was held in the spring of 1786, it having taken the executors and auctioneers nine months to inventory, organize, and describe her collections. Advertised daily in the newspapers, the auction, lasting 38 days, was a spectacular event, drawing hundreds of people who gladly crowded into her Whitehall townhouse to see her things and to watch the action as antiquarians, connoisseurs, and natural history brokers and collectors outbid each other in quest of the rare and beautiful.

A Collector “Few Men Have Equaled”

Of her collecting practices, W. S. Lewis wrote: “Few men have equaled Margaret Cavendish Holles Harley, Duchess of Portland, in the mania of collecting, and perhaps, no woman. In an age of great collectors she rivalled the greatest.”[1] Although she is known today

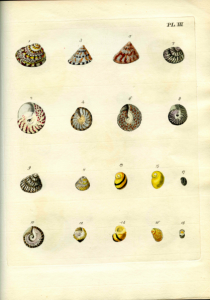

Plate III from Emanuel Mendes da Costa, The British Conchology (London, 1778).

The shells like these would have been in the duchess’s collection, some of which she would have collected herself along England’s southern coast.

primarily as a collector and the possessor of the Portland Vase, her interests in collecting extended beyond the exotic and rare to include a passionate engagement with the natural world. At Bulstrode, her country estate, she built a community where natural history inquiry was pursued with enthusiasm and conviction. Visitors to Bulstrode included Sir Joseph Banks, who became the President of the Royal Society, Daniel Solander, curator at the British Museum, and Mary Delany, now famous for her paper mosaics of botanically correct flowers. The duchess oversaw the construction of a botanical garden, a hot-house, a menagerie, and an aviary on her estate’s grounds; however, her interest in natural history went well beyond the aristocratic culture of collecting. Too often dismissed by historians of science as a magpie and a bowerbird, the duchess was a dedicated naturalist engaged in the Enlightenment project of collecting and classifying the natural world.

Formation to Dispersal

Cuban land snail shell. Photograph by Michael Kesl

The formation and the dispersal of duchess’s shell collection, one of the largest in eighteenth-century Europe, is the subject of my book. Some shells she gathered herself on the grounds of her estate, in nearby rivers, ponds, and streams as well as on visits to the English seacoast where she found new species of mollusks. Most, however, were the products of elaborate systems of exchange with gifts, trades, loans, and purchases that involved naval officers, colonial officials, natural history brokers, and other collectors. Her goal was to collect every known molluscan species and to publish a catalogue describing her collection. Her death put an end to this project, and her magnificent collection, containing at least 20,000 shells if not double that, was broken up into bite-size pieces, readily consumed by the auction’s eager crowds. So thoroughly dispersed, her shells disappeared into other collections, their provenance lost. Today we know the whereabouts of only three. A Cymbiola aulica, a sea snail shell from the Philippines, is in the British Museum, and two Cuban land snail shells are housed in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow; all three were bought at the Portland auction.

[1] W. S. Lewis, “Introduction,” The Duchess of Portland’s Museum (New York: The Grolier Club, 1936), v.

Beth Fowkes Tobin is a professor of English and Women’s Studies at the University of Georgia. She has published widely on eighteenth-century British art, literature, and natural history. Her most recent book is The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages (Yale UP, 2014).

Beth Fowkes Tobin is a professor of English and Women’s Studies at the University of Georgia. She has published widely on eighteenth-century British art, literature, and natural history. Her most recent book is The Duchess’s Shells: Natural History Collecting in the Age of Cook’s Voyages (Yale UP, 2014).

Wonders & Marvels is excited to announce that we have five (5) copies of THE DUCHESS’S SHELLS for a giveaway! To enter, sign up for the August giveaway below, and you’ll also get updates from our Monthly Features.

The entry period ends 11:59pm EST on August 29.

(At this time, we can only ship within the US)

Subscribe to our Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

August Book Giveaways

Beth Fowkes Tobin, “The Duchess’s Shells”

Miles Unger, “Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces”

Chet Van Duzer, “Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps”

August 10, 2014

The King Must Die?: Favorite Plot-lines

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

What’s your favorite plot line? One of my friends is a genius when it comes to recommending sci-fi and fantasy books, and not just on the ‘If you loved that, you’ll like this’ principle. I remember once saying to her: ‘Human lost in alien universe, not much happens beyond trying to get used to the culture, relates to ancient myths, preferably includes a romantic human-alien relationship’. She could make a suggestion just on that basis.

Not Much Happens…Or Does It?

I really like the ‘not much happens’ plot in which there is a quest, but getting to the end of it isn’t the point; it’s more about the individuals who work together on the journey, and about the universe in which they find themselves.

Overall, though, my favorite plot has to be ‘person moves to alien environment in which s/he hasn’t a clue what is going on, but painfully discovers the truth’.

Cases in Point

An example of that would be George R.R. Martin’s The Dying of the Light (1977), which is my favorite fantasy novel ever, ever (and before you ask, yes, I am working through the DVDs of Game of Thrones as I write this). In this the female protagonist, Gwen Delvano, has married a member of the Kavalar race but really doesn’t understand the complexity of the relationship of her husband with his male comrade, let alone the honor codes of the Kavalar.

One of the variants of this is ‘person moves to deserted part of their own world/country and misunderstands completely what’s happening’. Here I’d include The Wicker Man (1973), that wonderful cult movie based around the theme of the survival of pagan rituals of death and rebirth in a Scottish island. Or Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home (also 1973), a horror novel in which a family moves from New York City to a village Connecticut where they still follow ‘the old ways’. There’s another of my favorite plot lines here too – the ‘community conspiracy’, where Something Is Going On but our naive hero doesn’t see it, until It’s Too Late!

Both The Wicker Man and Harvest Home use the theme of a human sacrifice being necessary to ensure the fertility of the land. That also features in a novel by the excellent Mary Renault, The King Must Die (1958), which tells the story of the ancient Greek hero Theseus. The person most obsessed with this particular plot line, in which the death of the king and his replacement by a younger one is somehow the cause of the annual renewal of nature, must have been J.G. Frazer. In his influential The Golden Bough (abridged edition, 1922, but earlier versions from 1890), Frazer wanted to understand the Roman myths of the priest-king of Nemi, who was killed at the end of the year and another man chosen to take his place. Mary Beard has analysed the errors Frazer made and the leaps he needed to take in order to get his theories about Nemi to work, and shows something of the popularity of The Golden Bough in the twentieth century, but it’s perhaps in the work of the Dutch scholar Henk Versnel that we find the best analysis of the popularity of Frazer: Versnel described Renault’s book ‘as a kind of romanticized “Frazer abridged””.

So it’s not just me who likes this plot line. Where the ‘person moves to alien environment in which s/he hasn’t a clue what is going on, but painfully discovers the truth’ plot perhaps reminds me of those times in my life when I have felt completely out of my depth, and the ‘community conspiracy’ plays to my paranoia, the ‘the king must die’ plot plays to an even deeper underlying and unspoken fear that (to quote Game of Thrones) ‘Winter is coming’ and that we have not done what we must to ensure that the cycle of life is renewed again.

Further reading:

Mary Beard, ‘Frazer, Leach, and Virgil: the popularity (and unpopularity) of The Golden Bough‘, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 34 (1992)

Henk Versnel, Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion 2: Transition and reversal, Leiden: Brill, 1993

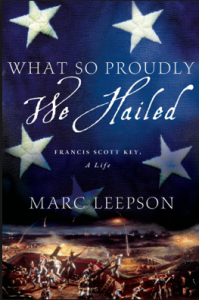

How I Write History…with Marc Leepson

An Interview with Marc Leepson (Guest Contributor)

An Interview with Marc Leepson (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: What is the earliest experience with writing that you remember?

Marc Leepson: When I was in second grade, our teacher, Mrs. Knobler, told us that we could write extra book reports if we liked. I took that to heart and wrote tons of them. I checked out just about every book aimed at boys my age from my local library. They were either sports oriented or adventure yarns, including The Hardy Boys. On the last day of school Mrs. K surpised my by giving me a prize for the most book reports. I believe it was a pen and pencil set.

W&M: You’ve come a long way from writing book reports! Can you tell us a bit about what sparked inspiration for one or more of your books?

Leepson: My latest book, What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, A Life, is the first biography of the writer of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in more than seventy-five years. It came about this way:

After I finished my previous book in 2010, I began brainstorming about my next book. I was thinking about 2014 and it being the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I–a subject I have been very interested in for a long time. I investigated, though, and found that there were already a ton of great books about the year 1914—one of the most monumental in history.

That let me to think backward in time about 1814, and Key writing “The Star-Spangled Banner” came immediately to mind. I remembered that in 2003-04 when I was doing the research for my book, Flag: An American Biography, a history of the American flag from the beginnings to the 21st century, I couldn’t find a current bio of Key. The most recent had been published in 1937.

So, I checked again. Still the same situation. I then called my agent. He didn’t believe me at first, but after doing some checking himself, he said to write a proposal for a biography of Francis Scott Key. I got the contract in 2012.

W&M: Thinking back across your projects, is there one research or writing related habit that’s crucial to a good workday?

Leepson: I start virtually every day by writing in my journal. I look at it as a kind of warm-up exercise for the day’s writing and research to come.

W&M: What is the most or least helpful advice you’ve ever received about research and writing?

Leepson: One of the most helpful was to use file folders—physical file folders arrayed on my desk in a file folder holder so the tabs are easily visible. I know it may sound odd in the digital age, and I do have plenty of Word files on my computer. But I like to print out nearly everything as well and file them in their appropriate files. It keeps me very well organized when it comes time for writing.

Marc Leepson is a journalist, historian and the author of eight books, most recently: What So Proudly We Hailed (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2014), the first biography of the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in more than 75 years. His previous books include Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General(Palgrave/Macmillan, 2011), Desperate Engagement (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2007), Flag: An American Biography (Thomas Dunne, 2005), and Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built(Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 2001; University of Virginia Press, paper, 2003).

Marc Leepson is a journalist, historian and the author of eight books, most recently: What So Proudly We Hailed (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2014), the first biography of the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in more than 75 years. His previous books include Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General(Palgrave/Macmillan, 2011), Desperate Engagement (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2007), Flag: An American Biography (Thomas Dunne, 2005), and Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built(Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 2001; University of Virginia Press, paper, 2003).

August 8, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. x

This week’s Cabinet of Curiosities is an explosion of oddities small and large…

This week’s Cabinet of Curiosities is an explosion of oddities small and large…

For those suffering summer colds and allergies, you may be interested in Renaissance Studies‘ recent articles on early modern health. While Jane Stevens Crawshaw considered Venetian women’s contributions to public health (with special attention to the medical secrets passed down in their families), Elaine Leong explored two women’s very different methods of reading and using medical manuals of the period.

Moving out from “under the weather” and over to “under the water,” a team of archaeologists began excavating the remains of The London — a ship sunk in 1665. Their major questions revolve around what, exactly, caused the explosion that sank the ship, and why there were so many female remains left behind.

While the archaeologists seek to answer questions, other historians were interested in debunking “common knowledge” answers to history trivia. Think that Napoleon was short? Or that Vikings wore horned helmets? Yeah…you may need to check this out!

Combining small and large scale historical experience, the New England Historical Society shared Calvin Coolidge’s written recollection of becoming president. The attempt to balance a sense of personal and national loss (among other moments) is a nice reminder of how human our officials truly are.

Finally, in 1744, Dr. Alexander Hamilton reported of his brief sojourn to Boston that he saw many pretty women and no prudes — a position that helped to shape his book Itinerarium (a collection describing the dress and behaviors of the people in the ‘wide range of society and scenery in colonial America.’ We wonder what Itinerarium II would contain…

What random findings ticked your fancy this week? Let us know in the Comments, or visit us on Twitter!

Addicted? Get your fix by subscribing to our features! You can choose how often you get updates (and you’ll get the latest in news and book giveaways).

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

The Random Researcher: Back to School

Last week, we reminisced about historical summer travel. This week, we turn our sights to the beginning of fall (otherwise known as back-to-school season). As you start thinking about restocking your wardrobe for cooler temperatures and scholastic spaces, let us take you into the archives to consider:

Last week, we reminisced about historical summer travel. This week, we turn our sights to the beginning of fall (otherwise known as back-to-school season). As you start thinking about restocking your wardrobe for cooler temperatures and scholastic spaces, let us take you into the archives to consider:

How did students dress during the 12th century?

The Medieval University

While universities existed earlier than the 12th century, this period saw a rise in their popularity and social importance. The University of Bologna, University of Paris, and Oxford University became three of the earliest preeminent establishments, providing physical institutions for their students as well as formalized seminars (1). Aided by the common tongue of Latin — in which all courses were taught, regardless of location — scholars could exchange ideas more broadly in dialogue and print (1). At this time, only men were admitted.

Practical Matters: Academic Regalia

Originating out of the Church, the early University carried with it similar visual markers — and academic dress was one of them. Students and professors alike wore on a daily basis the gowns of clerics (most had, after all, taken some kind of orders, made some kind of vow, or been tonsured) (2). But regalia also served practical purposes, as meetings took place in  cold halls and stone buildings. The lengths of gowns and volume of their sleeves allowed the wearer to preserve heat, add under layers, or tuck cold hands within. Meanwhile, academics also favored adding caps and hoods that could be lifted to cover the tonsured head.

cold halls and stone buildings. The lengths of gowns and volume of their sleeves allowed the wearer to preserve heat, add under layers, or tuck cold hands within. Meanwhile, academics also favored adding caps and hoods that could be lifted to cover the tonsured head.

Sartorial Developments: Rank & Specialty

The assignment of hood and sleeve designs (to designate rank) and regalia colors (to designate specialty) began later in the century, with universities such as Coimbra, Oxford, and Cambridge providing strict dress codes that made academic bodies readable. However, these prescriptions varied among the universities and did not become regularized across academic circles until the 19th century (2).

Regalia in the modern university is worn only for celebrations and key events, and academic historians are still working to develop a vocabulary and terminology to maintain formal dress codes.

Resources:

(1) “Medieval Education and the Rise of Universities,” Introduction to Medieval Philosophy and Modern Science 2008.

(2) Eugene Sullivan, “”Historical Overview of the Academic Costume Code,” American Council of Education 1997.

From the Archives: Back to School

Last week, we reminisced about historical summer travel. This week, we turn our sights to the beginning of fall (otherwise known as back-to-school season). As you start thinking about restocking your wardrobe for cooler temperatures and scholastic spaces, let us take you into the archives to consider:

Last week, we reminisced about historical summer travel. This week, we turn our sights to the beginning of fall (otherwise known as back-to-school season). As you start thinking about restocking your wardrobe for cooler temperatures and scholastic spaces, let us take you into the archives to consider:

How did students dress during the 12th century?

The Medieval University

While universities existed earlier than the 12th century, this period saw a rise in their popularity and social importance. The University of Bologna, University of Paris, and Oxford University became three of the earliest preeminent establishments, providing physical institutions for their students as well as formalized seminars (1). Aided by the common tongue of Latin — in which all courses were taught, regardless of location — scholars could exchange ideas more broadly in dialogue and print (1). At this time, only men were admitted.

Practical Matters: Academic Regalia

Originating out of the Church, the early University carried with it similar visual markers — and academic dress was one of them. Students and professors alike wore on a daily basis the gowns of clerics (most had, after all, taken some kind of orders, made some kind of vow, or been tonsured) (2). But regalia also served practical purposes, as meetings took place in  cold halls and stone buildings. The lengths of gowns and volume of their sleeves allowed the wearer to preserve heat, add under layers, or tuck cold hands within. Meanwhile, academics also favored adding caps and hoods that could be lifted to cover the tonsured head.

cold halls and stone buildings. The lengths of gowns and volume of their sleeves allowed the wearer to preserve heat, add under layers, or tuck cold hands within. Meanwhile, academics also favored adding caps and hoods that could be lifted to cover the tonsured head.

Sartorial Developments: Rank & Specialty

The assignment of hood and sleeve designs (to designate rank) and regalia colors (to designate specialty) began later in the century, with universities such as Coimbra, Oxford, and Cambridge providing strict dress codes that made academic bodies readable. However, these prescriptions varied among the universities and did not become regularized across academic circles until the 19th century (2).

Regalia in the modern university is worn only for celebrations and key events, and academic historians are still working to develop a vocabulary and terminology to maintain formal dress codes.

Resources:

(1) “Medieval Education and the Rise of Universities,” Introduction to Medieval Philosophy and Modern Science 2008.

(2) Eugene Sullivan, “”Historical Overview of the Academic Costume Code,” American Council of Education 1997.

August 6, 2014

Poisoning Enemies in the Ancient Mideast

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Insidious Acts

The insidious tactic of poisoning one’s enemy—noncombatants and soldiers alike—is nothing new. Only the technologies have changed. Choking clouds of dust with the effect of tear gas and rains of red-hot burning sand with the effect of phosphorus bombs are two examples of chemical weapons and biological strategies actually employed in antiquity (see for example, “Alexander the Great and the Rain of Burning Sand,” and “Before Pepper Spray,” among my other posts, in Wonders and Marvels archives).

Instances in Antiquity

Several instances of poisoning water and food supplies in North Africa by the Romans and their enemies the Carthaginians were reported by historians in antiquity. Such practices raised ethical issues even then but that did not stop some commanders from using biological and chemical strategies to destroy entire populations. Some Romans, for example, bristled at the very notion of resorting to toxic weapons because they contradicted the traditional ideals of Roman courage and honor. When several cities in the Near East revolted against Roman rule in 129-131 BC, however, the general sent to quell the rebellion turned to poison. Manius Aquillius was known as a cold-blooded commander notorious for his harsh military discipline and his ruthless suppression of the uprising in Rome’s new Province of Asia Minor (Turkey and Syria) led to disturbing rumors in Rome. The Roman historian Florus reported what occurred in his military history written in about AD 140.

The insurrection against Rome was led by Aristonicus of Pergamum (Turkey) succeeded in mobilizing ordinary people, rich and poor as well as slaves. Several cities joined the revolt and Aquillius’s Roman army was unable to gain control. “Aquillius finally ended the Asian War,” wrote Florus, “but his victory was clouded. For Aquillius had used the wicked expedient of poisoning the cities’ springs to force their surrender.” Florus was very clear about the immorality of such measures. “Though it hastened the Roman victory, it brought shame because he disgraced Roman arms and battle skills which until now had been unsullied by the use of foul drugs.” Aquillius’s poisoning of the entire populace of several cities, declared Florus, “violated the laws of heaven and the practices of our forefathers.”

Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009) and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 6 September 2013.