Holly Tucker's Blog, page 61

January 6, 2014

Cuvier and the “Living Mastodon”

by Adrienne Mayor  (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

(Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), the father of modern paleontology, was the first European naturalist to articulate a scientific theory of extinction, based on his studies proving that mastodons and mammoths were the prehistoric ancestors of living elephants. (Mastodons and mammoths went extinct 10,000-6,000 years ago.) This crucial advance in understanding the fossils of long extinct creatures came about in part because of Cuvier’s deep knowledge of ancient cultures’ discoveries of mammoth and mastodon fossils in Mediterranean lands and in the New World.

Cuvier gathered every known account of “giant bones” in classical literature and he also maintained an extensive archive of Native American discoveries and legends, sent to him by various Euro-American colonists and explorers. Yet the influence of ancient accounts of “the stone bones of giants and monsters” and the contributions of Native American observations of remarkable tusks, molars, and bones on Cuvier’s thinking are unappreciated today. One reason is that the leading historian of paleontology, Martin Rudwick, in his translations of Cuvier’s essential works into English (1997), omitted Cuvier’s French essays describing his avid curiosity about Native American fossil traditions. This omission leads recent commentators on Cuvier’s theories, such as Elizabeth Kolbert (“Annals of Extinction,” New Yorker, December 16, 2013), to overlook a significant body of evidence, one that Cuvier himself acknowledged.

Cuvier relied on friends and travelers in the Americas to send him every scrap of evidence they heard from Native Americans about petrified teeth, bones, and tusks found in the ground. They also sent him many actual specimens of fossils which he eagerly examined in Paris. The first mastodon femur and molars to be studied in Europe had been discovered by Abenaki Indian guides on the Ohio River in 1739 (another little-known fact in the history of paleontology). Specimens like these were crucial to Cuvier’s theory. But one object shipped across the Atlantic was just too good to be true.

Cuvier described the startling specimen from America in 1821 (Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles). The crate contained a mastodon tooth with pointed cusps—and a rotting front pachyderm foot complete with five toenails. According to the letter inside, the relics had been discovered in a cave by “les sauvages” living “west of the Missouri river.” Cuvier’s informant had purchased them from a comanchero (Mexican trader) who said he had obtained it from an Indian tribe. “But this foot was fresh!” It looked as though it had been “hacked from an elephant carcass,” noted Cuvier. “This find—if authentic—was almost enough to make one doubt that mastodons were extinct!”

Ever the scientist, Cuvier remarked: “I could not refrain from suspecting a fraud.” These specimens were displayed in Paris in the early 19th century but they no longer exist. The hoax from America was clever, since it combined a recognizable fossil mastodon tooth with a “fresh” elephant foot. One mystery remains: where did the foot come from? Possibly it had been removed from a well-preserved mammoth (not mastodon) carcass naturally mummified in a dry desert cave. But it seems more likely that it was taken from a recently deceased circus elephant. Elephants were being exhibited in America by the end of the 18th century.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times (2000, 2011); “Fossil Legends of the First Americans” (2005); and “The Poison King” (2010), a National Book Award nonfiction finalist.

December 18, 2013

The Amritsar Massacre: Another Step Toward Indian Independence

by Pamela Toler

Narrow entrance into Jallianwala Bagh

World War I brought India one step closer to demanding its independence from Great Britain.

Indian regiments sailed overseas and fought alongside their Canadian and Australian counterparts. (If you visit the memorial gateway at Ypres, you will see how many of them died in defense of the empire.) Indian nationalists loyally supported the British government during the war, fully expecting that British victory would end with Indian self rule on the dominion model.

Instead of self-rule, India got repressive legislation. The Rowlatt Acts, passed by India’s Imperial Legislative Council in March, 1919, continued the special wartime powers of the Defense of India Act. The new act took powers originally intended to protect India against wartime agitators, including the right to imprison those suspected of “revolutionary conspiracy” for up to two years without trial, and aimed them at the nationalist movement.

Indian members of the legislative council resigned their seats in protest. Mahatma Gandhi took the protest further, declaring a national day of work stoppage in the first week of April as the first step in a full-scale campaign of non-violent, non-cooperation against the so-called “Black Acts”.

The first implementation of the new laws occurred on April 10 in the Sikh city of Amritsar. The government of the Punjab arrested Indian leaders who had organized anti-Rowlatt meetings were arrested and deported without formal charges or trials. When their followers organized a protest march, troops fired on the marchers, causing a riot. Five Englishmen were killed and an Englishwoman was attacked. (She was rescued from the rioters by local Indians.)

Brigadier General Reginald Dyer was called into Amritsar to restore order. The situation called for diplomacy and good sense. Dyer used neither. On April 13, he announced a ban on public gatherings of any kind. That afternoon, 10,000 Indians assembled in an enclosed public park called Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate a Hindu religious festival. Dyer arrived with a troop of Gurkhas and ordered them to block the entrance to the park. Giving the celebrants little warning and no way to escape, he ordered the soldiers to fire on the unarmed crowd. They fired 1650 rounds in ten minutes, killing nearly 400 people and wounding over 1000.

In Britain, Dyer was widely acclaimed as “the man who saved India.” The House of Lords passed a movement approving his actions. The Morning Post collected £26,000 for his retirement and gave him a jeweled sword inscribed “Saviour of the Punjab.”

The government of India censured Dyer’s actions and forced him to resign his commission, but did nothing to stop local officials from continuing to inflame public opinion. In the Punjab, which remained under martial law for months following the Amritsar massacre, government officials acting “in defense of the realm” repeatedly humiliated and offended the people under their rule with actions such as making Indians crawl through Jallianwala Bagh.

Instead of “saving India”, Dyer accelerated Indian nationalist activity. Many Indians who had previously been loyal supporters of the Raj now joined the Indian National Congress, India’s largest nationalist organization. Bengal poet Rabindranath Tagore resigned the knighthood he had received after winning the 1913 Nobel prize for Literature. Motilal Nehru, president of the Congress and father of the first president of independent India, declared that “all talk of reform is a mockery”. Attempts to become equal partners within the Raj were almost over. Soon the push for independence would begin.

December 15, 2013

How Aeneas invented Pizza

Pizza Margherita, Neapolitan style

When most people think of Italy, they also think of pizza.

In Naples they will tell you they invented this culinary sensation and that their pizza is still the best in the world. Pizza purists say when in Naples there are only two types you should eat: Marinara and Margherita.

The first and most basic kind of pizza is simply a flat discus of hand-kneaded high-protein wheat dough covered with garlic-infused tomato sauce, garnished with a little oregano and put in an oven for a few minutes. Legend has it that fisherman made this as a substantial early morning breakfast. That is why it is called Marinara which means sailor (or “boatman”) in Italian. I had a wonderful pizza marinara at the Pizzeria I Re di Napoli with a view across the Via Partenope towards a medieval castle with a little fishing village at its foot: the Marinari Village. Get up early and you will see the fishermen going out as the sun rises behind Vesuvius.

The second type of pizza for purists is the Margherita. Rich, creamy buffalo mozzarella is added to the simplest version to create a pizza the same three colours as the Italian flag: red tomato sauce, green basil and white cheese. Guide books will tell you this tricolore version was created in honour of Queen Margherita’s visit to Naples in the late 1800s, but a BBC researcher recently exposed this as a clever publicity ploy.

However the pizzas got their names, they are delicious. When I was in Naples a few months ago, I was astounded at how something so simple could be so good. Whether it’s something in the water – as tour guide Nina Bernardo suggests – or maybe just the magic in the air, Neapolitan pizzas really are the best.

Ancient loaf of bread from Herculaneum

While sitting at an outdoor table on the Via Partenope and reading Virgil’s Aeneid, I came across a passage that almost made me choke on my pizza. The bronze age hero Aeneas has been sailing the seas with other fugitives from Troy looking for a new home. When he and his men land on the shores of mainland Italy, they are nearly out of food. They only have some stale round loaves of bread to eat. They collect some “fruits of the field” (cheese? herbs? garlic?) and put these on top of the thin base.

“Hey! We’re even eating our tables!” says Ascanius, the son of Aeneas.

[Heus etiam mensas consumimus inquit Iulus. VII.116]

Immediately Aeneas remembers a prophecy given earlier in their adventures: When you arrive at a place so tired and hungry that you eat your tables, you will know you have reached your promised land. (Aeneid VII. 124-127, paraphrased)

No, they didn’t have tomatoes in the Bronze Age, and yes, Aeneas and his men ate the toppings before the base, but this passage is a lovely link between modern Italian cuisine and its ancient legends.

So next time you bite into a pizza, remember to quote the words of Aeneas’ son: Heus! Etiam mensas consumimus!

Caroline Lawrence visited Naples with Andante Travels. She is working on a retelling of an incident from Virgil’s great epic poem for Barrington Stoke.

December 9, 2013

Pregnancy between East and West

By Helen King

(image courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Library and Center for Knowledge Management, University of California, San Francisco)

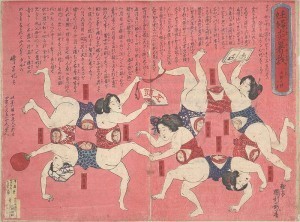

Sometimes you come across an image that really sticks in your mind. I recently attended a workshop on the representation of the womb across time, and one of the papers introduced me to this striking image by Utagawa Kunitoshi, dated to 1881; at first the eye sees five pregnant women frolicking, but then you realise there are in fact ten, sharing heads. This means that there are a total of ten wombs, represented as transparent so that the viewer can see the various stages of pregnancy. And this is possibly the most amazing aspect of the image; because it means that this Japanese woodblock, created in 1881, seems to refer to a Western tradition of showing the fetus-in-utero that goes back to the Middle Ages.

Japanese medicine in this period mixed traditional and modern, Western and Eastern. In premodern Japan, the womb is not visualised in this way; one of the participants at the conference, Anna Andreeva, showed that illustrations of a pregnant woman in medical treatises would show the fetus vaguely placed in the belly, or linked to the right kidney, without a ‘womb’ shown. In the West, images of babies in the womb, in a variety of positions, seem to have originated in the 5th or 6th c AD work of the Latin writer Muscio, who worked in North Africa. From the 13th century, the sequence of images associated with Muscio - originally a total of 15, with a further image of twins added later – also turns up attached to the surgical writings of Albucasis, and then in various manuscripts of the 15th century. In these images, the womb is usually just a circle, or a jar shape, and there is normally no sign of the woman; the focus is on the babies, and the accompanying text describes the range of different ways in which a baby can present for birth. While Muscio’s text also included instructions on how to deal with difficult presentations, the images seem to have floated loose from the practical advice as the midwives to whom Muscio addressed his work increasingly ceased to have control over difficult births, and as Galenic medicine increased its dominance over Europe. But the babies in Kunitoshi’s image are not at full term, presenting in different positions; they appear to be normal babies, developing in a normal way.

But those transparent bellies of those playful Japanese women recall another feature of western European iconography; medieval images in which Mary, the mother of Jesus, meets Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, and the artist shows the babies in the wombs of their respective mothers. As the women embrace each other, their unborn children greet each other.

While Japan in the Meiji era - the time of Kunitoshi – was welcoming western medicine and the modern illustrations from textbooks, and increasing state involvement in healthcare, the wombs of the playful pregnant women echo images from a much older western tradition. Were there any direct connections? Or did these transparent wombs arise spontaneously in this very different cultural context?

Further reading:

Monica H. Green, ‘The sources of Eucharius Roesslin’s “Rosegarden for Pregnant Women and Midwives” (1513)’, Medical History 53 (2009): 167-92: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/artic...

Susan L. Burns, ‘The body in question: the politics and culture of medicine in Meiji Japan, 1868-1912′, Wellcome History 36 (2007): http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/64249/1/Wellcome_History_36_Winter_2007_.pdf

December 8, 2013

A History of American Advertising in 19 Headlines

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

A few weeks ago, while cleaning my office at my wife’s insistence, I came upon an old collection that my uncle, Ben Sussman, had gathered. Ben, who died in 2003 at the age of 82, was the founder of an advertising agency and a columnist for Motor Trend magazine, recreational vehicle trade magazines, and many other publications. Warm, funny, and a maestro of sly teasing, he was endlessly curious and knowledgeable about the history of advertising. His professional papers are now available for all to see in the archives of Duke University.

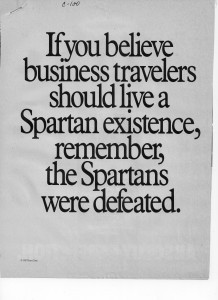

Ad headline for Hyatt Hotels & Resorts, 1987

Ben had saved a folder full of print advertising ledes, or headlines, that he found especially memorable. He scavenged them from magazines, newspapers, and trade journals, mostly during the 1970s and ‘80s. Many reflect his own distinctive taste and sense of humor, but some are undeniable classics of their kind.

Paging through them carried me back to a time when print advertising was king. A copywriter who could consistently invent clever ad headlines could count on a rewarding career. Today, of course, print advertising is in decline, and the art of lede writing has undergone many changes to adjust for the importance of ads in other media.

What Ben collected amounts to a museum of a lost craft of writing. Perhaps some of you recall the appeal and satisfaction of an advertising headline that demanded attention because of its wit and succinctness. I’ve assembled here a sampling of Ben’s favorites for your enjoyment.

“An Oasis in the Desert of Mediocrity.” — The Union Crackerjack bicycle. [Confederate Veteran, 1895]

“He Stopped a Whiskering Campaign.” — Gillette Blades. [Fortune, 1937]

“What’s the difference between an American bath and a French bath? What’s the difference between an American lover and a French lover?” — Parfums Marcel Rochas. [Vogue, 1971]

“It feels soft. It works hard.” — Ultra Ban deodorant. [1973]

“If Gas Pains Persist, Try Volkswagen.” [1974]

“Dumb Looking Sponge Has Something Inside It That Oozes Out and Washes Your Car.” — Suds-O-Matic sponges [1974]

“If You Steal $300,000 From the Mob, It’s Not Robbery. It’s Suicide.” Across 110th Street (motion picture). [1974]

“If Your Hair Isn’t Beautiful, the Rest Hardly Matters.” — Pantene shampoo. [1974]

“You are what you wheat.” — Kretschmer wheat germ. [Business Week, 1981]

“Our new typewriter system has more memory than what’s their name’s.” — Xerox. [Business Week, 1982]

“Where the Successful Stay Calm, Cool and Connected.” — The IBM Smart Desk personal computer. [Business Week, 1983]

“Not a Crowd in the Sky.” — TWA. [Fortune, 1983]

“Title Wave.” — RCA/Columbia Pictures Home Video. [American Film, 1984]

“We’ve Helped Five Million Americans Buy Homes. Yet Some People Think We Sell Candy.” — Fannie Mae. [Business Week, 1984]

“Here Today, Gone to Mali.” — Promoting NBC-TV foreign correspondent Steve Handelsman. [Advertising Age, 1986]

“If you believe business travelers should live a Spartan existence, remember, the Spartans were defeated.” — Hyatt Hotels and Resorts. [Fortune, 1987]

“Try our immortal sole.” — The Manhattan Ocean Club. [Advertising Age, 1987]

“Will your friends be seeing more of you this summer?” — Women Only private health club/spa. [Los Angeles Times, 1987]

“He Sells She Shells and He Shells.” — Advertising a bathroom furnishings designer who carries shell-shaped his-and-hers bathroom sinks. [Architectural Digest, 1989]

December 6, 2013

Scorpions in Antiquity

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

(Wonders and Marvels contributor)

“Scorpions are a horrible plague,” declared Pliny, “poisonous like vipers except that they inflict even worse torture by killing their victims with lingering, painful death that lasts three days.” “Everyone detests scorpions” chimed in Aelian, another natural historan of ancient Rome. In the desert of the Middle East the deadly creatures “lurk beneath every stone and every clod of dirt.” Scorpions posed such a menace along the caravan routes that Persian kings of antiquity routinely ordered great scorpion hunts and paid bounties for the most killed. In the Sinai Peninsula, said Aelian, giant scorpions “prey on lizards and cobras.” “Anyone who treads barefooted on scorpion droppings suffers terrible ulcers on the sole of the foot.” The largest scorpion species are 7-8 inches and they do hunt lizards and snakes, but scorpion poop pellets are not known to be dangerous to step on.

Aelian listed eleven types of scorpion: white, black, smoky, red, green, pot-bellied, crab-like, fiery red-orange, those with a double sting, those with seven segments, and those with wings. Most of these have been identified by entomologists; the others may have been venomous insects mistaken for the stinging arthropods. Twenty different scorpion species are known today in the Mideast. None of them fly, although many ancient texts refer to flying scorpions and winged scorpions are depicted in ancient Mesopotamian art. Pliny explained this error by pointing out that very strong desert winds and sandstorms gave the scorpions “the power of flight” and while they are airborne they extend their legs to resemble membraned wings. Pliny also claimed that scorpion stings were most deadly in the morning before the creatures have used up their venom.

The sting of a scorpion is terrifically painful, causing profuse sweating, intense thirst, great agitation, muscle spasms, convulsions, swollen genitals, slow pulse, irregular breathing, and death. Common defenses against scorpions since antiquity include wearing high boots and sleeping in hammocks or raised beds with each bedpost in a basin of water. Sprinkling scorpions with powdered aconite (monkshood, a poisonous plant) caused the creatures to shrivel up, remarked Aelian, but they were supposedly revived by hellebore, another toxic plant.

Roman historians reported that natives of desert regions were immune or had only mild reactions to local scorpions. Following ancient traditions still practiced today, some Bedouins believe that ingesting crushed, dried scorpions makes one immune to their sting. Interestingly, meerkats and some mice have developed immunity to scorpion venom, a neurotoxin. As with many other powerful, lethal natural toxins, medical uses for miniscule doses are being discovered by modern researchers.

The fear factor of the dread scorpion was exploited by ancient Greek hoplite soldiers who painted scorpion figures on their shields to terrify their foes. The scorpion was the emblem of the Praetorian Guard, the Roman emperor’s personal army, and a catapult with a tremendous kick was nicknamed “the scorpion.” It is no coincidence that US military missiles carry names like “Scorpion” and “Stinger” to instill confidence in the soldiers who man them and inspire terror among the enemy.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award

November 24, 2013

Congratulations to Lucy Inglis, W&M Contributor!

A HUGE WONDERS & MARVELS CONGRATULATIONS to our friend and colleague, Lucy Inglis, for the call-out to her Georgian London: Into the Streets as a History Today’s Best Books of 2013. “Reading her brisk, astringent and highly amusing tour around various quarters of Hanoverian London on Boxing Day is the ideal antidote to the excesses of Christmas and will keep you snugly entertained in your armchair for hours.”

Lucy is in great company, including Joel Harrington’s “sparkling” The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent 16th Century. Joel is a longtime Vanderbilt colleague, who is co-directing the Robert Penn Warren Fellows Program on “Public Scholarship” with me next year.

I’m checking in with Lucy to see if she has more updates to share about the fantastic things that have been happening around her book. From what I can tell, she’s been BUSY. Check out her Twitter updates here. In the meantime, you’ll find all of her W&M posts here.

November 22, 2013

From Genealogy to Genocide: Family History and Big History

By David Laskin (Guest Contributor)

*The publisher is offering a giveaway copy or two. For a chance to win one, please leave a comment. David will be keeping an eye on comments and is looking forward to interacting with W&M readers. Winners will be selected randomly. US only.

I love how the term “family history” straddles the intimate and the momentous. We family historians start with our grandparents’ memories and recipes, move on to census records and army discharge papers, and end, to our delight or horror or both, with world war, fortunes made and lost, the rise and fall of nations, boom, bust and genocide.

Surprises are to be expected when you go searching for your roots.

I had always know that my Great Aunt Itel, known to the world as Ida Rosenthal, founded the legendary Maidenform Bra Company (“I dreamed I…in my Maidenform Bra”). On the strength of wits, ambition and marketing genius, this chain-smoking 4 foot 11 inch immigrant dynamo turned a novelty undergarment line into one of the largest family businesses in the world.

What I discovered, after searching Ancestry.com and interviewing distant relatives, is that while Aunt Itel was becoming a tycoon in Roaring Twenties New York, her first cousins Chaim and Sonia were struggling to make the desert bloom as idealistic Zionist pioneer farmers in what was then Palestine.

Chaim and Sonia’s children in present-day Israel revealed to me that there was yet a third branch of the family that I had never known of. These were the relatives who had chosen to remain behind in what was then Poland. A trove of family letters that the Israelis had saved for 40 years revealed the story.

As economic and social conditions deteriorated during the 1930s, the family in Poland agonized about leaving. In September,1939, the door slammed shut. With the outbreak of war, the family was trapped in Soviet-occupied Poland. Two years later, Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and the Germany army seized the sector of Poland where my family lived. The cousins of the glamorous bra tycoon became prisoners of the Third Reich.

All of them perished in the Holocaust.

David Laskin is author of The Family: Three Journeys into the Heart of the 20th Century, just published by Viking.

November 18, 2013

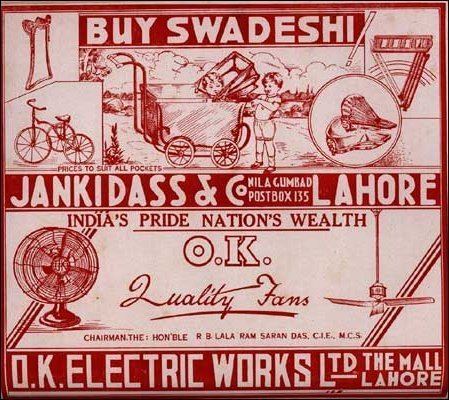

The Swadeshi Movement: The First Step Toward Indian Independence

by Pamela Toler

Beginning in the 1830s, the British East India Company provided Western education to a small number of Indian elites: it was cheaper and more effective than recruiting the entire work force of the empire back home in Britain. In addition to training clerks of all kinds, the East Indian Company created as a by-product what Thomas Babington Macaulay described as “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”. A large proportion of this class came from Bengal province, home to Calcutta, then the capital of British India. Calcutta soon became the center of a thriving Indian intelligentsia.

Following the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, expanded opportunities for Western education and Queen Victoria’s proclamation of equal opportunity for all races seemed to open the door for advancement. A generation of young Indians saw Western education as the path to jobs in law, journalism, education, and, most importantly, the Indian Civil Service. They soon discovered that the door was less open than it initially appeared. Thwarted in their desire to play a larger role in India’s government, the most politically conscious among them founded India’s first nationalist organizations. At first, their model was not the United States but Canada: not independence, but self-rule within the Commonwealth.

In 1905, the Indian government divided Bengal into two provinces, leaving its powerful western-educated elite a minority in its own homeland. The official explanation for the division was bureaucratic efficiency. The western-educated Bengali elite saw it as an attempt to undercut their power base.

Bengalis signed petitions against the partition and marched in protest through the streets of Calcutta. They also boycotted British imports, especially British cloth. Protestors burned British-made saris and other cloth to the cry of swa-deshi (of our own country). Wearing clothing made from swadeshi cloth became an emblem of nationalist beliefs. A few leaders called for Indians to boycott not only British goods, but British institutions, knowing that the law courts and government services could not function without the support of Indian employees. The movement soon spilled over into other regions of India.

As swadeshi sales grew and India’s industrial base boomed, the Indian government cracked down. The movement’s leaders were arrested. Politically active students found their financial air threatened. The police attacked protest marchers with long, metal-tipped poles called lathis.

After several years of increasingly violent protests, the Indian government annulled the partition of Bengal and instituted a series of reforms designed to give Indians a voice in local government. At the time, nationalist leaders were hopeful that they had taken the first step toward self-rule. In fact, the partition of Bengal proved to be the first in a series of decisions made over the next thirty years that would drive Indians to demand their independence.

November 14, 2013

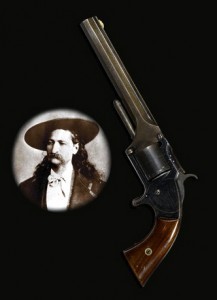

It Didn’t Save Wild Bill

While researching my second Western Mystery for kids, P.K. Pinkerton and the Petrified Man (AKA The Case of the Good-looking Corpse), I discovered a fascinating fact: very few gunfights played out like the iconic Western movie “showdown”. Two antagonists rarely faced each other like self-moderating duelists on Main Street, one honorably waiting for the other to “draw”. More often one man would “throw down” on another without warning, sometimes even shooting from behind through a window or door.

While researching my second Western Mystery for kids, P.K. Pinkerton and the Petrified Man (AKA The Case of the Good-looking Corpse), I discovered a fascinating fact: very few gunfights played out like the iconic Western movie “showdown”. Two antagonists rarely faced each other like self-moderating duelists on Main Street, one honorably waiting for the other to “draw”. More often one man would “throw down” on another without warning, sometimes even shooting from behind through a window or door.

One night in 1876 in a Deadwood saloon, a famous gunfighter with silky golden locks was shot in the back of the head while playing poker. The shooter, a certain Jack McCall, fled. Hurdy girls screamed and other gamblers recoiled in horror. Wild Bill Hickok, already a legend in his own time, was dead. The reputed inventor of the “fast draw”, Hickok usually took a seat in a corner of a saloon or against wall, so nobody could sneak up on him. But on that fatal night he sat with his back exposed. Perhaps he was feeling tired of life. He was an alcoholic who rubbed mercury on his skin to alleviate the symptoms of venereal disease. This poisonous treatment made him drool and start to lose his sight. According to Deadwood author Pete Dexter, it often took him twenty minutes to empty his bladder.

As Hickok slumped onto the table, the five cards in his hand fell on the floor, spattered with drops of blood. Legend has it that he held two pair – black aces and a pair of black eights – that would later come to be know as the ‘Dead Man’s Hand’. He did not even have time to reach for his own weapon.

That weapon was a small, old-fashioned revolver, a Smith & Wesson number two six-shooter which had first gone into production more than fifteen years before. Unlike fiddly cap and ball revolvers, which required the user to combine the ingredients for a bullet in each chamber of the cylinder, the Smith & Wesson had powder, ball and charge encased in a single cartridge. Protected by this rimfire “bullet”, the powder would never grow damp, the ball would never fall out and the charge would never misfire. You could just put a new cartridge into the cylinder. You could even pop out an entire used cylinder and put in a new one with six cartridges pre-loaded in. The gun was small enough to be slipped into a pocket and was therefore favored by gamblers.

In Roughing It, Mark Twain’s account of his days in the Wild West, he describes his own pistol. “I was armed to the teeth with a pitiful little Smith & Wesson’s seven-shooter,” he writes, ”which carried a ball like a homoeopathic pill, and it took the whole seven to make a dose for an adult.” The Smith & Wesson Number 1 took seven .22 caliber cartridges. The new improved Number 2 took six cartridges rather than seven, and they each held a bigger .32 caliber ball, (i.e. the diameter of the ball was about a third of an inch.) Like the Number 1, the Number 2 had a spur trigger which only popped out when you cocked it. This new improved second-edition was so popular that Smith & Wesson had to stop taking orders at one point of production until they could catch up with demand.

Hickok’s Smith & Wesson Number 2 had a pretty rosewood grip and blued steel barrel. Sheriff Seth Bullock took it from Hickok’s pocket and sold it to help pay off the gunfighter’s debts. It then passed from one generation to the next, one of the best documented firearms ever to go on sale.

Yes, on Sunday 17 November 2013 – the day after tomorrow – this famous revolver will go up for auction in San Francisco, and is expected to fetch as much as half a million dollars… maybe more.

Until then it will be on show along with other early pistols and items of armour at Bonham’s auction house on 220 San Bruno Avenue in the Mission District. Viewing is free to the public and starts at high noon today, Friday 15 November. If you are in San Francisco, come along and have a look at a famous piece of Western history. I might see you there!