Holly Tucker's Blog, page 63

October 14, 2013

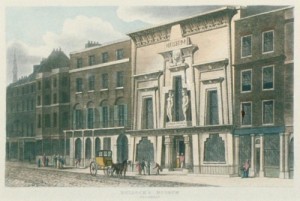

Piccadilly’s Egyptian Hall

Eighteenth century Piccadilly was a place for all sorts of curiosities to be displayed. Almost opposite Burlington House, at 170–173 Piccadilly, a Starbucks coffee shop now sits where William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall once stood. From 1798, when Nelson triumphed at the Battle of the Nile, English interest in the ‘East’ began to soar. While obelisks and other monumental pieces had been leaking out of Egypt for a century, Napoleon’s heavy thieving from Luxor and Karnak made Egyptian objects desirable amongst the European elite. The victory of the Battle of the Nile also coincided with a period in which an extended grand tour took in Turkey or Egypt. The romance of the East rapidly took hold of the English upper-class imagination, with books, prints and Eastern costume all the rage.

In 1809, Bullock’s Museum arrived in London from Liverpool. The following year, Bullock turned down the opportunity to display the Hottentot Venus, Saartjie Baartman. His reasons are not recorded. In 1812, the Egyptian Hall was ready for occupation. It must have appeared quite surreal to the man on the street. The grand hall of the interior was an extraordinary replica of the avenue at the Karnak Temple complex, near Luxor. By 1819, Bullock was ready to sell his collection of real and spurious objects, and did so in an auction lasting twenty-six days. It was dispersed all over the world. Emptied of its original tenant, the Egyptian Hall received a new and rather more suitable guest: Giovanni Battista Belzoni, known to his English friends as ‘John’.

An Italian strongman and performer, with an English wife, Belzoni was a true adventurer: in 1817, he travelled to the Valley of the Kings and broke into the tomb of Seti I. From Seti’s tomb, Belzoni took a sarcophagus of white alabaster inlaid with blue copper sulphate of great beauty. The retrieval of the sarcophagus, however, was not without peril: the tomb was located in the catacombs, a maze of traps and dead ends, dug to confuse grave robbers. The French interpreter panicked and an Arab assistant broke his hip in a booby trap. Undeterred, Belzoni retrieved the sarcophagus and brought it to England along with the head of the ‘Younger Memnon’. Belzoni suffered constant vomiting and nosebleeds in Egypt, whilst Sarah was unaffected by so much as a case of sunburn – much to her husband’s chagrin.

London eagerly anticipated the imminent arrival of these treasures. Shelley’s famous poem of 1818, ‘Ozymandias’, was written for a newspaper competition held by The Examiner in advance of the arrival of Belzoni’s treasures. The exhibition opened at the Egyptian Hall in May 1821, but a year later the collection was put up for auction. The sale drew two of the greatest collectors of the day: the British Museum and Sir John Soane. The Museum acquired the colossus and Soane the sarcophagus. John Belzoni, financially if not spiritually satisfied, handed in the manuscript of his travels to his publisher, John Murray, and set off for Benin. He died of dysentery one week after arriving there.

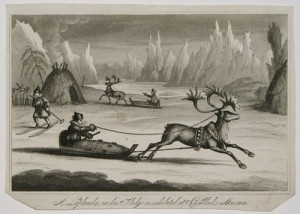

Before long, the Egyptian Hall moved on to displaying real-life Laplanders, who gave sleigh rides up and down the central space. It continued on as an exhibition space until redevelopment in 1904, when this extraordinary Georgian flight of fancy was replaced with offices as part of the great slum clearances.

October 11, 2013

Frederick Law Olmsted, John Singer Sargent, and Nature’s Design

By Elizabeth Goldsmith (W&M Contributor)

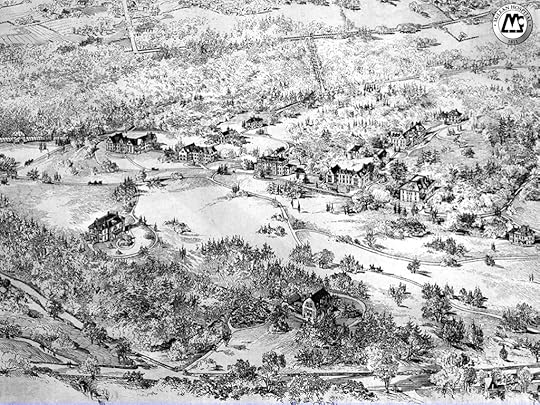

Last week, I visited the Frederick Law Olmsted Historic Site in Brookline, Mass. It is a soothing place, an 1810 farmhouse purchased by Olmsted in 1883 and remodeled by him to accommodate his growing landscape architecture business. On just two acres of land, Olmsted managed to design the grounds using his favorite techniques, creating small, inviting stone paths that curve through stands of elm, pine, and oak, then opening out to a sunny lawn that Isabella Stewart Gardner allowed him to blend with the field below her summer house next door. In an early photograph, the whole Olmsted house is covered in vines.

As a National Historic Site it is also a modest place, considering the huge scope of the legacy left by the man who lived and worked there. Olmsted is best known as the creator of Central Park, a design he completed with his partner Calvert Vaux. With that celebrated project he may be said to have invented the field of landscape architecture, going on provide most of the major cities in America with a legacy of his genius. To name a few, the great parks of Boston, Chicago, Brooklyn, Milwaukee, Louisville, Rochester, Buffalo, Baltimore, Denver, Seattle, all bear his signature. He designed the grounds of the U.S. Capitol and all or parts of the campuses of Stanford, Cornell, Amherst, Yale, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, Smith, Mount Holyoke, and many others.

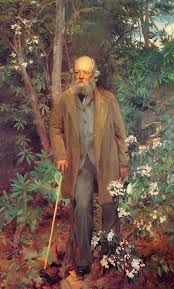

Olmsted by Sargent

The final work project of his life, though, was for a private client, George Washington Vanderbilt, who in 1895 had just completed The Biltmore, the largest private residence ever built in the United States. It was a 250-room chateau outside of Ashville, North Carolina. Olmsted worked to landscape the place. Perhaps recognizing that his 73-year-old landscape designer was in poor health, Vanderbilt arranged for Olmsted’s friend, the artist John Singer Sargent, to come down from Boston to paint his portrait on the grounds of the estate. Sargent chose to place his subject in a setting of thick vegetation. It is a poignant picture of an old man leaning on a cane and somehow receding slightly into the mass of greenery around him. Flowers and flowering bushes had never been Olmsted’s forte; he had always preferred to plant trees that took little tending. In Sargent’s portrait, the flowers seem slightly out of control, reaching to overtake the elderly gentleman standing in their midst.

Olmsted was ill, and had to leave the Biltmore before the portait was completed, leaving his son to put on his father’s coat and continue the posing sessions so that Sargent could finish his work. For the next two years Olmsted’s family and doctors tried to slow what became an inevitable decline into senile dementia, moving him to Deer Isle, Maine where they hoped that the isolation and beauty of the natural surroundings would have it’s usual curative effect on him. Through it all, he wrote letters obsessively, expressing his panic that the Biltmore and other commissions were not being properly completed. Finally, in 1898 he was committed to the McLean Asylum in Belmont, Mass.

The new McLean hospital, boasting a large campus sheltering the institutional buildings from the stressful urban environment where it had previously been located, had been built in 1895. The initial selection of the site and the first drawings for the grounds had been done by … Frederick Law Olmsted. He remembered that project. When he arrived at the hospital he was immediately drawn to the grounds, but to his disappointment he realized that the final plan used was not of his design. “They did not carry out my plan,” he said to his family, “confound them!”

He died at McLean on August 28, 1903.

McLean Asylum 1900

Further reading:

Justin Martin, Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted ( Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2011).

Lee Hall, Olmsted’s America: An ‘Unpractical’ Man and His Vision of Civilization (Boston and New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1995).

October 9, 2013

One-sex and two-sex bodies?

by Helen King

Tomorrow is a big day for me; finally, my latest book is published. It’s about the claim that there was a clear division in the history of Western Europe between two models of the body: ‘one-sex’ and ‘two-sex’. In the first model, men and women were seen as having exactly the same genital bits and pieces, but with men’s on the outside because they had the ‘heat’ to push them out. In this model, stories of a woman changing into a man later in her life made sense, because she had become ‘hot’ enough for her bits to come out. In the second model, men and women were completely different and there was no point trying to match up the bits in the way the first model encouraged: vagina = penis, womb = scrotum and so on. This picture of two models is most closely associated with the work of Thomas Laqueur, who dated the shift from one to the other to some time in the (long) eighteenth century, and associated it with other changes that created the ‘modern’ world.

Now, as the title suggests, I don’t find this model works for the historical periods with which I’m most familiar, the classical and the early modern. Instead, I’ve argued that back in 5th/4th c Greece, the Hippocratic texts saw women as very different from men; so different, that they needed their own branch of medicine. This suggests one of the reasons why it’s important to know what people believed about sex difference. If you think men and women are pretty well the same, but with a few extra bits or a few of the same bits in different places, then you may as well offer them broadly similar medical treatments. But if women are seen as fundamentally different, this difference extending to every part of their flesh all over their bodies, then that can be an argument for separate doctors and different treatments.

So how did I come to write this book? In a previous job, I realised that Laqueur’s book was the only one in our university library that seemed to be falling apart. Clearly a lot of courses had it as set reading. But the argument made little sense for any of the primary sources I was reading. So in 2005 I wrote an article, but realised there was a book lurking in there somewhere. A few more years down the line, I started working on a Hippocratic case history – Phaethousa, who grew a beard when her husband left her. She didn’t become a man – instead, she died. Was this a one-sex or a two-sex story? Did it suggest movement between the sexes, or total difference? Or – moment of breakthrough – did it suggest that things were a lot more complicated than the ‘one-sex to two-sex in the eighteenth century’ model envisaged?

So I wrote the first draft of a book, and sent it to the editor of a suitable series in which to publish it. He liked it, but decided there was a different book lurking inside that original draft – a book which engaged directly with the Laqueur model and its continued popularity. Hence the choice of title: ‘trial’ and ‘evidence’. So, a total rewrite was needed, and it did indeed become a very different book. And now it gets released to the world. Unlike Laqueur, I’m not offering an attractively simple model of change from weird and old, to sensible and new. But the debate I’m describing still applies to medicine today; just how different are men and women, and where does that difference reside in their bodies?

More on my book, including some sample content, on http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/978140946...

A pre-print draft of the 2005 article, ‘The mathematics of sex’, is on http://oro.open.ac.uk/28098/1/Mathema...

October 8, 2013

Nine Nazi leaders and the secrets only their psychiatrist knew

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

My newest book, The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII (PublicAffairs Books), tells the story of a U.S. Army psychiatrist’s quest to make sense of the months he spent in the company of the imprisoned leaders of the Third Reich as they awaited trial in Nuremberg. For five months in 1945-46, Douglas M. Kelley enjoyed the plum assignment of examining and studying the top Nazis. He hoped to identify a “Nazi personality” or common mental disorder that the prisoners shared, but the project ultimately proved his ruin.

Psychiatrist Douglas M. Kelley a few years before he met the Nazis at Nuremberg

In his interviews with the Nazi captives, however, Kelley learned much about the psychiatric idiosyncrasies of the German leaders, and he recorded them in his medical notes and writings. Here’s a listing of a few:

9. Alfred Rosenberg, Nazi party philosopher and Reichsminister for the Eastern Occupied Territories, believed that the United States should maintain the superiority of the white race by deporting its black and Jewish citizens to the African island of Madagascar.

8. The brutal former governor of Nazi-occupied Poland, Hans Frank, returned to his Catholic faith during his incarceration and professed to welcome his prosecution and punishment. Kelley believed that Frank was playing the martyr, and the International Tribunal’s justices sentenced the Nazi to hang.

7. Karl Dönitz, an admiral and Hitler’s designated successor in the final days of the war, hoarded and hid in his cell such items as shoelaces, string, a screw, and a bobby pin. Prison authorities never determined how Dönitz intended to use them.

6. The group’s lowest IQ score, 107, went to Julius Streicher, editor of the notoriously antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer (The Storm Trooper) and a pornography collector considered so vulgar by his fellow defendants that few would sit at the same table with him.

5. Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president and former minister of economics, had the highest IQ among the top Nazi defendants, scoring 143 on the intelligence test.

4. Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop kept the messiest cell of all the Nazi captives. Kelley regarded the disarray as a sign of Ribbentrop’s distraught mind.

3. The fearsome Ernst Kaltenbrunner, chief of the German security police, felt such stress and anxiety as the Nuremberg Trial approached that his high blood pressure triggered a cerebral hemorrhage, and he had to miss the first weeks of the court sessions.

2. Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess believed that his jailers were trying to slip poison into his food, and he kept samples of chocolate, sugar, crackers, and other foods that he suspected were tainted.

1. Hermann Göring, Reichsmarschall, Luftwaffe chief, and a planner of the Holocaust, was a warm-hearted supporter of animal rights who designed German laws that reformed hunting regulations and sent violators of anti-vivisection legislation to concentration camps.

There’s much more about the psychological study of the top Nazis, their responses to Dr. Kelley’s assessment tests, and their contribution to the psychiatrist’s personal and professional downfall in The Nazi and the Psychiatrist.

Video trailer for The Nazi and the Psychiatrist

October 6, 2013

Alexander the Great and the Giants

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Alexander and his men waded across the raging Hydaspes River during a violent lightning storm to surprise the vast army of 35,000 men commanded by king Porus of India (326 BC). Already taken aback by Porus’s 200 war elephants, the Macedonians were awe-struck by the prodigious height of the Hindu king. According to Alexander’s biographer Plutarch, the monarch’s “great size and powerful physique made him appear as suitably mounted on an elephant as an ordinary man looks on a horse.” Porus was nearly 7 feet tall, towering over Alexander, who was about 5 feet, average size for a Greek man of that era. The Porus’s high turban and majestic bearing amplified the impression of grandeur, as did his seat on the back of an extra-large Indian elephant, about 11 feet at the shoulder.

The Macedonians emerged victorious after a long and bloody battle. Porus was captured; he’d lost a staggering 23,000 of his men. Alexander politely asked his king-sized prisoner how he wished to be treated. “Like a king!” was Porus’s booming reply. The two rulers became friends and Alexander gave him command of his former kingdom as his vassal.

Porus was not the first giant encountered by Alexander and his army. In 335 BC when he was consolidating his power in the Balkans, Alexander met with the robust, tall Celts of the Danube and Adriatic Sea region. The historian Arrian wrote that Alexander, hoping to hear his own name, asked “these people of great stature and arrogant disposition” to name their greatest fear. “That the sky might fall on their heads!” came the booming reply. Alexander stalked away, muttering that the Celts’ answer seemed to trumpet their own sky-scraping height. Averaging about 6-6.5 feet tall, the Celts were not truly giants—but they certainly seemed so to the smaller Greeks.

The gigantic stature of Porus (and the Celts) may have inspired Alexander’s psychological ruse of war after the great battle at the Hydaspes River. To discourage potential attacks and to impress the inhabitants of Pakistan and northern India, Plutarch reported that Alexander ordered his blacksmiths to forge special weapons and equipment that “far exceeded the normal size and weight.” He left these huge items in his camps around the countryside to frighten the populace. But the country of India itself proved far vaster than the Macedonians had imagined. Not long after the defeat of Porus, Alexander and his army began the long march home.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

October 1, 2013

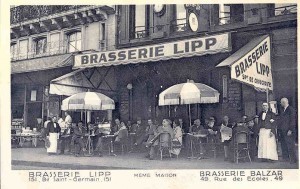

Work Should Be More Like a Café

By W. Scott Haine & Jeffrey H. Jackson

When Yahoo!’s president required employees to work from the office rather than home, she raised a fundamental question about where we generate our most innovative ideas. Do we need to work collaboratively to be inventive, or can we be inspired when we are alone?

When Yahoo!’s president required employees to work from the office rather than home, she raised a fundamental question about where we generate our most innovative ideas. Do we need to work collaboratively to be inventive, or can we be inspired when we are alone?

We suggest that in a creative economy, people need what we call “thinking spaces.” These sites offer two key elements: they provide time for individual thought, but they also encourage in-depth conversation. Innovation comes from a balance of both.

The original model for the “thinking space” was the café. Born in 17th century London, the modern café allowed thinkers to spend the day contemplating new ideas for the price of a drink. As hubs of human activity, patrons could also find others with whom to share and debate their thoughts. Cafés created the first “social networking sites” where innovators interacted in depth and in real time.

In the nineteenth century, cafés in cities like Paris, Vienna, Rome, and New York became famous for the cutting-edge artistic movements and fervent political ideologies generated there. Revolutionaries, philosophers, and artists all had their favorite haunts. Cafés were the incubators of “bohemianism,” the avant-garde practice of living on the edge for the sake of one’s highly idiosyncratic ideas even while trying to sell those ideas to a publisher or a gallery. Bohemian ingenuity was in many ways the origin point of the modern creative economy.

The innovations generated in cafés have shaped the world we live in. Cafés as thinking spaces continue to offer a model for how we can work in a creative economy where we’re all bohemians. Each of us needs privacy to cultivate our own unique voice and generate ideas, but we must refine those notions through conversation, brainstorming, and exchange with others. Without that balance, great ideas can suffer in silence or be subsumed in groupthink.

Ironically, despite the growing number of coffee shops in American cities and their historic role in creative exchange, cafés offering a blend of isolation and sociability have been replaced by sites where we are alone in public. Starbucks and many others have brought elements of the historic café tradition into the present, but most customers in these places cut themselves off from one another with earbuds and laptops. How many people truly discuss ideas with someone at Starbucks on a regular basis?

It doesn’t have to be this way. Cafés themselves can still offers inspiration, and encouraging interaction might be good for business. When one New Haven, Connecticut coffee shop banned laptops, business boomed as people came in for the human interaction rather than the wi-fi.

Local coffee shops provide a sign to place on the table inviting other people to sit down and talk. Nearly all university libraries and many office buildings offer a café where people gather. Meet-ups often happen in cafés and bars in order to bring people together and share new ideas. These new approaches to re-creating the café feeling represent a self-conscious effort to combat the tendency toward isolation and balance private thoughts with public conversation.

Business is emulating the café as well. Many offices, especially those in the high-tech sector, mimic important aspects of the café as a thinking space. Steve Jobs insisted that the corporate headquarters of Pixar allow random, spontaneous, serendipitous sociability. Such well-designed offices have proven to be some of the most creative places around.

The phenomenon of “co-working,” where freelancers or business travelers use a common space even though they are working on different projects or for different employers, is changing how many people conceive of the social nature of work. “Co-working” is based on the premise that we work best when we are in a community, even when our ideas are heading in different directions.

An old-fashioned activity like talking is not efficient in modern technological terms, and it certainly requires more than 140 characters or a status update. But as creativity increasingly becomes a necessity at work, the tried-and-true model of the café as a “thinking space” may provide a way to update an old idea for a new era.

W. Scott Haine teaches at the University of Maryland University College and Jeffrey H. Jackson is the J.J. McComb Professor of history at Rhodes College in Memphis. The authors are co-editors of the book The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy, and Vienna (Ashgate Press).

September 29, 2013

Archival Wonders

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

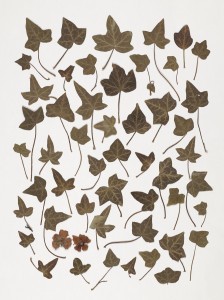

Cut foliage in Bridget Hyde’s book (c. 1676-1690): Wellcome MS 2990, image 150. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

A few days ago, a friend of mine mentioned on a certain social media site that she had just found pressed flowers in an eighteenth-century recipe book. Nothing unusual in that—there are lots of bits and bobs stuck into old papers.* But it is always a delight for researchers.

Here is my top five list of unexpected things that I’ve found:

a doodle of a strange turtle man holding an envelope, at the bottom of an eighteenth-century love letter (Wellcome Library).

two crumbling blue pills in a small packet attached to an early nineteenth-century collection of family medical letters and recipes (Dordogne Archives).

several recipe clippings, with hand-written notes, stuck into an early twentieth-century cookery book that I found at an Oxfam shop.

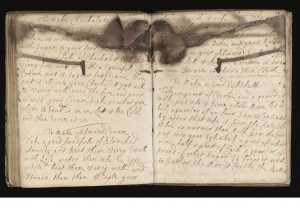

a burn mark that goes through half of a seventeenth-century recipe book (Wellcome Library).

the scent of tea leaves wafting through a series of eighteenth-century medical consultation letters (British Library).

We might handle old texts and piece together stories all the time, but somehow these surprises tease us with the sense that we’ve directly encountered the past. The burn mark evokes a busy woman who had been cooking while keeping the book a little too close to the hearth where a stray cinder landed upon int. Or perhaps, she was scratching away in the book by candlelight and accidentally knocked the candle over onto the open book… We can imagine the woman’s consternation as she beat out the fire on her book.

Epicentre of the burn in Wellcome MS 4051. (Thanks to archivist Helen Wakely who told me about this book!) Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Our fragmentary link to the past, however, is not straightforward. As my friend pointed out, the biggest mystery is what century the flowers are from. Just as there is no evidence to indicate who pressed the flowers, or when, the true circumstances of the recipe book damage will never be determined. The blue pills don’t correspond to any specific references in the family’s papers; the recipe clippings are undated and the tea-scented letters might have been put in a chest over a hundred years later. The only definitive evidence for my list is that the turtle man doodle was in the same ink as the rest of letter.

These moments of archival wonder may not offer much in the way of facts, but they are nonetheless important. They remind us that the manuscripts had users other than us: people who read the books, failed to take their pills and stored letters in safe places.

And they give us an excuse to let our historical imaginations run rampant before we get back to business…

Have you found any surprises in the archives?

* The medievalfragments blog , for example, frequently discusses textual curiosities in medieval manuscripts. My favourite post is on “Paws, Pee and Mice: Cats among Medieval Manuscripts”.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and blogs at Sloane Letters Blog and The Recipes Project. She tweets as @historybeagle.

September 20, 2013

Retreating to Recharge

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

I’ve written elsewhere about the need—for me, anyway—to develop a routine for my writing. But once in a while it’s beneficial to shake that routine up.

So a few weeks ago I left my treadmill desk and my schedule and went to Loretto, Kentucky for a three-day retreat with my critique group. We stayed in an old (1860s) boarding school at an academy that was founded in 1812 by three young women—girls, really—who were determined to educate girls in what was then the frontier.

This convent is the mother house of the order of the Sisters of Loretto and serves primarily as a home for about eighty dynamic, intelligent, engaged elderly women who spent their youth working in AIDS wards at a time when most people, even health-care professionals, refused to go near those patients; setting up and teaching in schools in Latin America and Africa; teaching inner-city youth that others had written off.

A path marked by timbers, leading to a maze

These women, some of whom are more than 100 years old, have earned a leisurely retirement, but they refuse to retire from life. They’re engaged in replanting native species on their land; solar panels are on the roofs of all but the historic buildings; they’re actively involved in the local schools; they raise funds for a school in South Sudan; they know all about politics (and sports) and have strong opinions about both. They accept donations to subsidize housing people recently released from incarceration for civil disobedience. They’ve been referred to as “badass” in the media for refusing to allow an oil pipeline to cross their property.

Three girls used to share the room I slept in

My critique group had an entire floor to ourselves. The wood floors of the corridors, wide enough to allow two girls in hoop skirts to pass each other side by side, were so polished you could see your reflection in them. The ten-foot ceilings, huge windows, and transoms made for a constant exchange of air. We each had a private room, and we had a large lounge to work in. We ate meals with the nuns, which led to some fascinating conversations.

In other words, a writer’s paradise. We wrote in groups and individually, took walks, critiqued madly, did writing exercises (this one proved particularly useful), talked about writing and life and the writing life, and left inspired and recharged.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

September 18, 2013

Gandhi’s March to the Sea

Gandhi picking salt on the beach at the end of his march.

by Pamela Toler

The American Revolution had the Boston Tea Party; the Indian independence movement had Gandhi’s salt march.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the British government in India had a heavily taxed monopoly on the production and sale of salt. It was illegal for anyone to make or sell salt. If a peasant who lived near the sea picked up a piece of natural salt, he could be arrested.

In 1930, Gandhi used the issue of the salt tax to turn non-violent protest against British rule into a mass movement. The Indian independence movement had long focused on British laws that concerned middle and upper class Indians, such as discrimination against Indians who applied for government jobs. Gandhi argued that the salt tax was an example of British misrule that affected all Indians.

Gandhi began his campaign against the salt tax on March 2 with a letter to Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, announcing his intention of breaking the salt laws. Ten days later he began a 240-mile march to the sea with seventy-eight followers–carefully chosen to represent a cross-section of India.

Crowds gathered along the route to cheer the marchers on. The international press followed them, reporting their progress each day to a watching world. More protestors joined the march each day. By the time Gandhi reached the shore, twenty-five days later, several thousands protestors marched with him.

Gandhi spent the night of April 5th in prayer with his followers. Early the next morning, he waded into the surf, then walked along the beach until he found a place where the evaporating water had left a thick crust of salt. He picked up a lump of natural salt and urged Indians to resist the tax by manufacturing their own salt.

People across India responded to the Mahatma’s call for civil disobedience. Villagers all along India’s coastline went to the beach to make salt. Volunteers from the nationalist movement openly sold illegal salt in the cities and distributed pamphlets telling people how to make salt. Over the course of a month, the police arrested tens of thousands of people for salt-related crimes and protests. True to Gandhi’s principles, his followers did not resist arrest, even when the police beat them with clubs. Gandhi himself was arrested on May 4 and held without trial or sentence until January. News of the Mahatma’s arrest led to more protests–and still more arrests.

With salt protests breaking out all over India, the British government was forced to negotiate with Gandhi. On March 5, 1931, Lord Irwin signed the Gandhi-Irwin pact, ending the salt protest. Indians were now allowed to collect salt for their own use. Gandhi and other political prisoners were released. More important, the British scheduled a conference in London to discuss changes in Britain’s rule of India.

Gandhi’s 240 mile march had brought India one step closer to independence.

September 14, 2013

Georgian London: Into the Streets

It’s finally here! Georgian London: Into the Streets is now on the streets, available at your local bookstore or on Amazon. Due to distribution issues, I know Amazon US customers have been redirected to buy from Amazon UK. However, there’s a signed copy up for grabs here at Wonders and Marvels. Simply leave a comment with why the Georgian period is your favourite and I’ll pick a winner tomorrow morning. Hurray!