Holly Tucker's Blog, page 43

November 27, 2014

Chaucer’s Room

By Paul Strohm (Guest Contributor)

Plan of Holy Trinity Priory, with Aldgate North Tower

When Chaucer obligingly stepped into a controversial job as Controller of the Wool Custom in 1374, one of his rewards was a rent-free accommodation over Aldgate, the easternmost and busiest of the City’s gates.

There, literally under his feet, passed royal and religious processions, spectacles of public humiliation, expelled convicts and sanctuary seekers, provisioners and trash-haulers with iron-wheeled carts and vans, drovers, water and wood sellers, traders, runaway serfs, 1381 rebels flowing in from Essex, and all the rest of a busy city’s shifting populace . . . Surely no residence more fitting could be imagined for a poet whose subject was soon to become, as Dryden would put it, “God’s plenty.”

But what kind of a place was this, really? Chaucer’s lease for his dwelling survives, describing it with the Latin word for “mansion,” but this could be misleading; Latin mansio could be a sleeping room, a fine accommodation, or anything in between. Fortunately, while researching my Chaucer biography, I have found valuable new evidence.

Life over Aldergate

Tower, Upper Floor

In 1585 John Symonds (a joiner by trade but an exacting draftsman) prepared a detailed sketchmap of neighboring Holy Trinity Priory to facilitate its liquidation in the aftermath of its dissolution. Long unnoticed in the upper left hand corner of his sketch is a scale drawing of the Aldgate north tower, a close equivalent of the south tower in which Chaucer probably lived.

The archaeological “footprint” of this tower has it as some 26 feet in diameter, but (according to other examples and also the Symonds rendition) Chaucer’s room would have had walls at least five feet in thickness, reducing the size of the room to roughly 14 x 16 feet. The interior walls were of unfinished stone. The room’s sole illumination was provided by two (or at most four) arrow slits, wide on the inside for an archer’s access but then tapering to an aperture of four or five inches in the exterior stone wall. Light, even at mid-day, would have been extremely feeble. Arrangement for a small, open fire might have been possible. Waste would be hand-carried down to the open sewer of Houndsditch at the base of the tower. Meals would not ordinarily have been cooked there; London practice of the day was to eat on the run, at open kitchens or in taverns, with bread and other cooked food purchased directly from streetside ovens. Chaucer could have had access to the tower’s crenellated roof, but the stench of Houndsditch (serving the newly-built latrines of the populous and adjacent Holy Trinity) would have nullified the romance of rooftop exposure.

Nor can Aldgate with its dimly-lit and rough-finished stone interior be imagined as any sort of “family” accommodation. Chaucer’s elegant wife Philippa is, significantly, unnamed in his lease–even though such leases often contained the names of both husband and wife. This was, to be frank about it, no place for a classy lady like Philippa. During most or all of Chaucer’s 1374-86 residence in Aldgate, she and the children were living well in Lincolnshire with her notorious and prosperous sister Katherine Swynford, mistress and eventual wife of the awesomely empowered Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt. Any company in the tower would have been bivouacked troops, gatekeepers, and members of the City Watch.

Tower of Solitude

Tower Window with Arrow Slit

Chaucer’s solitude can easily be imagined and, at one moment in his poetry, he imagines it for us. The Aldgate tower is the imagined location to which the “Geffrey” of Chaucer’s House of Fame returns at night, when his “reckonings” at the Custom House are through. His guide in that poem, the overbearing Eagle, taunts him about his solitude:

. . . of thy very neighebores,

That dwellen almost at thy doores,

Thou hearist neither that ne this . . .

Thou goest home to thy house anoon,

And, as dumb as any stoon,

Thou sittest at another book

Til fully dased is thy look;

And livest thus as an heremite . . .

The Eagle undoubtedly has it right. Whatever transient guests he may or may not have entertained along the way, Chaucer lived in Aldgate alone.

References:

Illustration: the Symonds Sketchmap. Hatfield House, Library of the Marquis of Salisbury, CPM I/19, upper left-hand corner]

Chaucer’s lease: Martin M. Crow and Clair C. Olson, Chaucer Life-Records (Oxford University Press, 1966), pp. 144-47.

The quotation from Chaucer’s House of Fame, with spelling slightly modernized, is based on The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry Benson (Boston, 1987).

Images:

From Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury by Paul Strohm. Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House company. Copyright Paul Strohm, 2014.

Paul Strohm is Garbedian Professor of the Humanities, Emeritus, at Columbia University. His Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury was published November 2014 by Viking Press.

Paul Strohm is Garbedian Professor of the Humanities, Emeritus, at Columbia University. His Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury was published November 2014 by Viking Press.

November 25, 2014

The Strange Journey of Niccolò Paganini’s Corpse

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

In the years before I had my own family, I devoted a big part of my life to amateur musicianship. I played the mandolin, an instrument favored by my Greek-born grandfather. Unlike many of today’s American players who immerse themselves in the rich performing styles of bluegrass music, I was most interested in the mandolin’s classical-music traditions. That’s how the 19th-century Italian virtuoso-composer Niccolò Paganini first came to my attention.

Paganini, best remembered today as a violin superstar whose modest output of compositions is still heard in the concert hall, also played the mandolin and wrote intriguing music for the instrument. They were too difficult for me to attempt. But his name and music continue to attract my interest to this day.

Recently, while reading Guy de Maupassant’s nonfiction book Afloat (Sur l’eau) — a lyrical journal of sailing in the Mediterranean — I came upon the author’s account of the strange disposition of Paganini’s body after the composer’s death from a respiratory infection in 1840. In Maupassant’s telling of the tale, Paganini’s son Achillino tried to bring his father’s body to his home city of Genoa for burial. Genoese authorities refused to admit the body into the city for a variety of religious and public-health reasons, and Achillino kept searching for a suitable resting place for his father. The citizens of Marseille and Cannes also would not accept Paganini’s corpse into their cemeteries. Finally, in desperation, Achillino sailed to the uninhabited island of Saint-Ferréol — a reef “red and bristling like a porcupine,” Maupassant wrote — where he buried Paganini’s casket in the rocky soil until a better place could be found. There it remained for five years.

Many biographers of Paganini dismiss Maupassant’s account as an unlikely fable. In 1891, however, a friend of Paganini, Auguste Blondel, published a memoir of the violinist’s final days and burial that supported Maupassant’s narrative and placed Blondel at the scene of the interment on Saint-Ferréol.

Maupassant wrote that Achillino returned to Saint-Ferréol in 1845 to retrieve his father’s body and bring it to Genoa for burial. The corpse of Paganini still did not rest, though, and it was repeatedly subjected to disinterment and openings of the casket until 1896, when it received a final burial in Parma.

I would rather not recall this final episode in Paganini’s life and death when I listen to the composer’s transporting music. Maybe in time I will forget the details. “Would one not have preferred that the extraordinary violinist should have remained at rest upon the bristling reef, cradled by the song of the waves as they break on the torn and craggy rock?” Maupassant declared. I have to agree.

For more information:

Kawabata, Mai. Paganini: The ‘Demonic’ Virtuoso. Boydell Press, 2013.

de Maupassant, Guy. Afloat (Sur l’eau). George Routledge and Sons, 1889.

Paganini, Niccolò. 24 Caprices for Violin. [Video] Performed by Salvatore Accardo.

The strange journey of Niccolò Paganini’s corpse

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

In the years before I had my own family, I devoted a big part of my life to amateur musicianship. I played the mandolin, an instrument favored by my Greek-born grandfather. Unlike many of today’s American players who immerse themselves in the rich performing styles of bluegrass music, I was most interested in the mandolin’s classical-music traditions. That’s how the 19th-century Italian virtuoso-composer Niccolò Paganini first came to my attention.

Paganini, best remembered today as a violin superstar whose modest output of compositions is still heard in the concert hall, also played the mandolin and wrote intriguing music for the instrument. They were too difficult for me to attempt. But his name and music continue to attract my interest to this day.

Recently, while reading Guy de Maupassant’s nonfiction book Afloat (Sur l’eau) — a lyrical journal of sailing in the Mediterranean — I came upon the author’s account of the strange disposition of Paganini’s body after the composer’s death from a respiratory infection in 1840. In Maupassant’s telling of the tale, Paganini’s son Achillino tried to bring his father’s body to his home city of Genoa for burial. Genoese authorities refused to admit the body into the city for a variety of religious and public-health reasons, and Achillino kept searching for a suitable resting place for his father. The citizens of Marseille and Cannes also would not accept Paganini’s corpse into their cemeteries. Finally, in desperation, Achillino sailed to the uninhabited island of Saint-Ferréol — a reef “red and bristling like a porcupine,” Maupassant wrote — where he buried Paganini’s casket in the rocky soil until a better place could be found. There it remained for five years.

Many biographers of Paganini dismiss Maupassant’s account as an unlikely fable. In 1891, however, a friend of Paganini, Auguste Blondel, published a memoir of the violinist’s final days and burial that supported Maupassant’s narrative and placed Blondel at the scene of the interment on Saint-Ferréol.

Maupassant wrote that Achillino returned to Saint-Ferréol in 1845 to retrieve his father’s body and bring it to Genoa for burial. The corpse of Paganini still did not rest, though, and it was repeatedly subjected to disinterment and openings of the casket until 1896, when it received a final burial in Parma.

I would rather not recall this final episode in Paganini’s life and death when I listen to the composer’s transporting music. Maybe in time I will forget the details. “Would one not have preferred that the extraordinary violinist should have remained at rest upon the bristling reef, cradled by the song of the waves as they break on the torn and craggy rock?” Maupassant declared. I have to agree.

For more information:

Kawabata, Mai. Paganini: The ‘Demonic’ Virtuoso. Boydell Press, 2013.

de Maupassant, Guy. Afloat (Sur l’eau). George Routledge and Sons, 1889.

Paganini, Niccolò. 24 Caprices for Violin. [Video] Performed by Salvatore Accardo.

Barclay de Tolly: Traitorous Foreigner or Hero of 1812?

By Sigrid MacRae (Guest Contributor)

Barclay de Tolly, a Baltic German of Scottish origin, had a long and distinguished military career, instituting significant reforms and improvements in the Russian military as Minister of War under Tsar Alexander I. But his greatest test was yet to come. Writing the Tsar in early 1810, he warned that “a power has drawn near the frontiers of Russia…” and of the “the unlimited ambition of the French Emperor…”

Barclay de Tolly, a Baltic German of Scottish origin, had a long and distinguished military career, instituting significant reforms and improvements in the Russian military as Minister of War under Tsar Alexander I. But his greatest test was yet to come. Writing the Tsar in early 1810, he warned that “a power has drawn near the frontiers of Russia…” and of the “the unlimited ambition of the French Emperor…”

Knowing that Russian forces were not only greatly outnumbered by Napoleon’s vast Grande Armée, but also widely dispersed, he had already enunciated a plan for dealing with those ambitions, based on a strategy devised by Fabius Maximus, a Roman general famous for avoiding bloody confrontations with strategic retreats, harassment and delaying tactics. When “the great tempest broke,” as Barclay wrote of Napoleon’s invasion on the moonlit night of June 24, 1812, Fabius’s plan seemed appropriate to the circumstances. He would spare the tsar’s army by withdrawing into Russia’s depths, leaving only scorched earth, and drawing the enemy far from reinforcements and supply lines, until Russia’s bitter winter came to her aid.

In the first weeks, retreat followed retreat, and Barclay’s measured approach — avoiding direct engagements — gradually earned him popular scorn as a “foreigner,” a “traitor,” bringing shame on Mother Russia, and disrepute to her uniform. Even American Ambassador John Q. Adams commented on the “extraordinary clamor” against Barclay.

Given the fevered atmosphere, Tsar Alexander commanded Barclay to fight at the ancient holy city of Smolensk. Napoleon gloated that the resulting conflagration was “like the spectacle an eruption of Mount Vesuvius” offered Neapolitans. It vindicated Barclay’s strategy, but lost him his command, and turned his name into a derisive pun: Boltai da i Tol’ko – all talk, nothing more.

Replaced by aged, ailing, but thoroughly Russian Field Marshal, Mikhail Kutuzov, the bloody battle at Borodino again made the wisdom of Barclay’s delaying tactics clear. Napoleon, in Moscow at last – but in hostile territory, far from supply lines, and still without victory — delayed his retreat. Ultimately, Russia’s “General Winter” reduced his army of roughly 650,000 to pitiful, straggling survivors. It was a military disaster; Barclay had been right.

Barclay was soon reinstated and honored. Though rejected by ardent Russian nationalists — Tolstoy for one, belittled his contributions to victory over Napoleon in War and Peace – Barclay’s statue looms outside St. Petersburg’s Kazan Cathedral, and his august portrait in the Hermitage’s 1812 War Gallery inspired Russia’s great poet, Alexander Pushkin, to immortalize him in “The Commander.”

Further reading:

Clausewitz, Carl von, Der Feldzug von 1812 in Russland, und die Befreiungskriege 1813-1815, Berlin, 1835. Digitized by Google, uploaded to the Internet Archive.

Josselson, Michael and Diana, The Commander: A Life of Barclay de Tolly, New York, Oxford University Press, 1980.

Lieven, D. C., Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace, New York, Viking, 2010.

Zamoysky, Adam, Moscow 1812L Napoleon’s Fatal March, New York, HarperCollins, 2004.

Sigrid MacRae is co-author with Agostino von Hassell of Alliance of Enemies: The Untold Story of the Secret American and German Collaboration to End World War II, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2006. Her latest book A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany has just been released.

Sigrid MacRae is co-author with Agostino von Hassell of Alliance of Enemies: The Untold Story of the Secret American and German Collaboration to End World War II, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2006. Her latest book A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany has just been released.

W&M is excited to have five (5) copies of A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00 pm EST on November 27th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that at this time we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

November Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms’ Folk and Fairy Tales”

Sigrid MacRae, “A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany”

Jerry Brotton, “Great Maps”

November 24, 2014

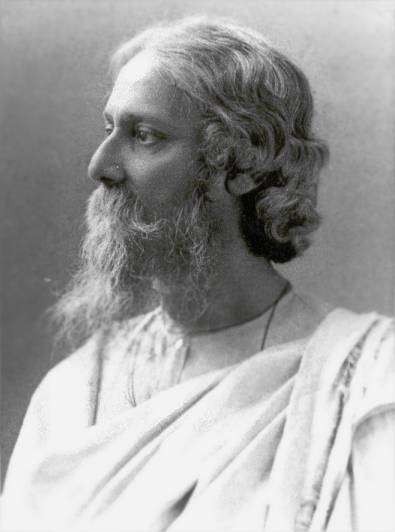

Rabindranath Tagore: Poet, Nobel Laureate, Indian Nationalist (Sort-of)

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Few people in the modern world attain the degree of celebrity that allows them to be known by a single name: Napoleon, Gandhi, Madonna. Even those who reach single-name celebrity in their own country may be largely unknown to the rest of the world. Take the example of Bengali poet, novelist and composer Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) who is known in India simply as Kabi, the Poet. Every Bengali language speaker, all 250 million of them, knows a line or two of his poetry. By contrast, most westerners know Tagore only (if at all) as the recipient of the Nobel Prize, but have no sense of either the poetry for which he won the award or his broader career.

Born in 1861, to a prominent Calcutta family, Tagore was a leading member of the late nineteenth century literary, cultural and religious reform movement known as the Bengali Renaissance. He is generally considered the father of the modern Indian short story, he pioneered the use of colloquial Bengali in literature, and created a new genre of popular contemporary music known as rabindra-sangeet that draws on traditional Bengali folk and devotional music as well as Western Folk melodies. (After independence, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh all chose songs by Tagore as their national anthems.) He is often compared to Tolstoy, and seen as a precursor to Gandhi,

Tagore became famous as a writer when he published his first novel in 1880, at the age of nineteen. In 1905, he became involved in nationalist politics after the British Viceroy, Lord Curzon, divided Bengal province in two, effectively cutting the power base of the Bengali elite who headed the early Indian nationalist movement. In response, Indian nationalists boycotted British goods and institutions, a protest known as the Swadeshi (of our own country) movement. At first Tagore threw himself into the Swadeshi cause, leading protest meetings, writing political pamphlets and composing patriotic songs. His initial enthusiasm for the movement failed when the Bengali population was torn by increasing communal violence between Hindus and Muslims. Despite bitter criticism from nationalist activists., he withdrew from the movement in 1907, concentrating instead on experiments in economic development and education in the villages on his estate.

Tagore made the leap from national to international fame in a single year with the help of one important admirer. He traveled to London in 1912 with a collection of English translations of 100 of his poems, which became the collection known as Gitanjali. While he was in London, he met William Butler Yeats, who became a passionate advocate of his poetry. In part as a result of Yeats’ championship, Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature on November 13, 1913. Tagore’s Nobel Prize sparked a brief, but intense, period of popular and critical interest in his work in the west. It was soon translated into many languages, including a French translation by André Gide and a Russian translation by Boris Pasternak. Tagore himself became an international literary celebrity, traveling around the world on lecture tours and revered as the embodiment of the mystical east. His critics accused him of collaboration with the enemy, especially after he was knighted by King George V in 1915.

Accusations that Tagore was an imperial collaborator ended in 1919. On April 13, Brigadier General Reginald Dwyer ordered soldiers under his command to fire on an unarmed crowd of 10,000 Indians who had assembled in an enclosed public park in the Punjabi city of Amritsar to celebrate a Hindu religious festival–an event that became known as the Amritsar Massacre. The soldiers fired 1650 rounds in ten minutes, killing 400 and wounding more than 1000. Tagore resigned his knighthood in protest.

For the rest of his life, Tagore criticized British rule in india while refusing to reject Western civilization, a position that often placed him in opposition to Gandhi.

November 23, 2014

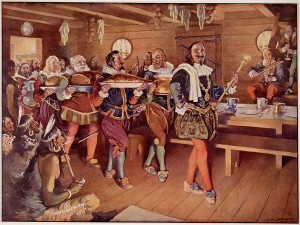

Samuel de Champlain’s Thanksgiving Feasts, French Style

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

When the explorer Samuel de Champlain built a fortified settlement on the south shore of the Bay of Fundy in 1606, he and the group of men who accompanied him were determined to survive the winter in good health. Many of their number – more than thirty – had died of scurvy in the previous year. Europeans at the time didn’t know precisely what foods could prevent scurvy, but they did believe that better nutrition would be key to healthy survival in their new settlement of Port-Royal. Medical treatises also advised that scurvy could be combatted by avoiding the boredom and depression that so often accompanied winter in northern climes. So along with some regular feasting they needed to plan good entertainment.

When the explorer Samuel de Champlain built a fortified settlement on the south shore of the Bay of Fundy in 1606, he and the group of men who accompanied him were determined to survive the winter in good health. Many of their number – more than thirty – had died of scurvy in the previous year. Europeans at the time didn’t know precisely what foods could prevent scurvy, but they did believe that better nutrition would be key to healthy survival in their new settlement of Port-Royal. Medical treatises also advised that scurvy could be combatted by avoiding the boredom and depression that so often accompanied winter in northern climes. So along with some regular feasting they needed to plan good entertainment.

L’Ordre du Bon Temps

They dubbed their new organization ‘The Order of Good Cheer’. This social club pledged to provide festive meals at least every couple of weeks throughout the winter season. The primary beneficiaries were the noblemen and other prominent French settlers, with members of the Mi’kmaq Nation who had assisted in constructing the Port Royal stockade also attending and receiving leftovers. One of the Frenchmen in regular attendance was the writer and poet Marc Lescarbot. He provided theatrical pieces that were staged to music to entertain the guests. The dinners were hosted by Monsieur de Poutrincourt, the appointed leader of the settlement, and the food was provided by all members of the club, who took turns bringing in meat from the hunt and vegetables that had been preserved from summer gardens.

They dubbed their new organization ‘The Order of Good Cheer’. This social club pledged to provide festive meals at least every couple of weeks throughout the winter season. The primary beneficiaries were the noblemen and other prominent French settlers, with members of the Mi’kmaq Nation who had assisted in constructing the Port Royal stockade also attending and receiving leftovers. One of the Frenchmen in regular attendance was the writer and poet Marc Lescarbot. He provided theatrical pieces that were staged to music to entertain the guests. The dinners were hosted by Monsieur de Poutrincourt, the appointed leader of the settlement, and the food was provided by all members of the club, who took turns bringing in meat from the hunt and vegetables that had been preserved from summer gardens.

The Essential Ingredient

At the end of the winter, only seven settlers had succumbed to scurvy, and these were poor folk who had not been present at many of the feasts. Champlain and Poutrincourt congratulated themselves on the success of ‘The Order of Good Cheer’. But modern historians have been mystified, because the key ingredient for preventing scurvy – vitamin C – was not present in the generous portions of meats and vegetables that the settlers managed to keep on the table that winter.

Recently, a closer look at the menus as described in Port-Royal reports and letters sent back to France has yielded a clue. The settlers describe eating a new food that they call “small red apples.” These were no doubt cranberries, rich in vitamin C. This was an item on the menu that had probably been introduced to the settlers by their Mi’kmaq neighbors. They are still called “pommes de prés,” or meadow apples, today in Acadia.

For Further Reading:

Samuel de Champlain, Voyages (1613)

Raymonde Litalien and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America (2005)

November 21, 2014

Teaching Cryptography, Writing History

By Derek Bruff (Guest Contributor)

When you teach mathematics, it’s not every semester that a major motion picture is released that’s squarely on-topic for your course. Then again, the math course I’m teaching this fall isn’t your typical math course.

At Vanderbilt University, where I teach mathematics, every first-year undergraduate in the College of Arts & Science is required to take a first-year writing seminar, and every department is required to offer one. The English and philosophy departments offer plenty, but mathematics? Writing seminars aren’t the kind of courses that come naturally to us.

A few years ago, I volunteered to try my hand at teaching a writing seminar. My day job is directing the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching, so I’ve talked to many instructors from a variety of disciplines about teaching different kinds of courses, and I was eager to teach something other than my usual statistics and linear algebra courses. What would it be like to teach a writing seminar?

The course I put together is called “Cryptography: The History and Mathematics of Codes and Ciphers.” This fall is my third time offering the course, and it’s now my favorite course to teach. It’s an unusual blend of pure mathematics, puzzle solving, history, current events, and, yes, writing. One of my favorite aspects of the course is that the students who take it are generally very interested in the topic. First-years have a lot of writing seminars to choose from, so those who select my cryptography course usually bring with them a high degree of interest in the subject. That’s not the case for my statistics course!

What does it mean to teach writing in a mathematics course? It took me a couple of iterations of the course to develop a good answer to that question, but I think I have one. Effective mathematics writing involves explaining the math you want your audience to learn in a way that makes sense to them, given their mathematical backgrounds. (In that respect, good writing has something in common with good teaching.)

To give my students the opportunity to practice this aspect of mathematics writing with an authentic audience, two years ago I partnered with Holly Tucker, a fellow faculty member at Vanderbilt and editor of the collaboratively authored history blog Wonders & Marvels. My students produced a series of essays on the history of cryptography, and Holly published a selection of these essays on Wonders & Marvels.

Before the students got to work, Holly visited my class and talked with them about the kind of posts that she published on her blog and about the audience who reads them. I believe that this gave my students a far more concrete sense of audience for their writing than they would have had with a more generic writing assignments and that this, in turn, helped them produce better writing. Also very helpful: Holly’s feedback to the students on their submissions, in her role as editor.

Alan Turing

That was two years ago. This fall, Holly and I partnered again, and the assignment has a special relevance. That major motion picture I mentioned? It’s The Imitation Game, a biopic on the British codebreaker, mathematician, and computer scientist Alan Turning, featuring none other than Benedict Cumberbatch in the lead role. Turing’s creative genius was instrumental in cracking the German Enigma cipher, which in turn was a critical part of the Allied victory in World War II. The Imitation Game opens in the US next week, on November 28th.

In my cryptography seminar, we spend a week on World War II military cryptography, with an emphasis on Turing and his fellow codebreakers at Britain’s Bletchley Park. I was thrilled to find out that The Imitation Game would be released while the course was running this fall. Holly and I decided to run my students’ posts on the history of cryptography this week, just before the US release of the film. The posts have been running all this past week, and you can read them all here.

To the Wonders & Marvels readers, I hope you’ve found my students’ essays interesting. The students have done some great work, and they’ve enjoyed writing for you. I also hope you’ll go see The Imitation Game. It’s receiving stellar reviews—and it’s already in theaters in the UK! My students will be on Thanksgiving break when it opens in the US, but we’re planning to go see it as a class on December 1st when we’re all back on campus. A class trip to the movies for a math course? I can’t wait!

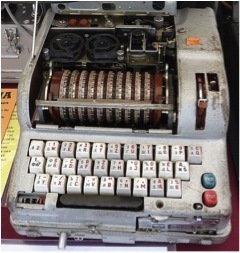

Fialka: The Bigger, Better, Russian Enigma

By Matthew Gu (Guest Contributor)

The nuclear capabilities of the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War were no small matter. A single attack could, in theory, escalate all the way to a devastating nuclear war; millions, if not billions could die. Therefore, secrecy was of the utmost importance. There was a great need for secure channels of communication on both sides of the Iron Curtain. The Russian military needed encryption rivaling Enigma, the fiendishly difficult cipher machine used by the Germans in WWII. But Enigma had been broken by Allied cryptanalysts by the end of WWII. The more secure successor, the German Lorenz cipher machines, had been broken as well by the secret British Colossus computers. A new, stronger encryption was needed.

Enter Fialka. Used primarily through the 1960’s and 1970’s, the machine was used by the Russian military to communicate with other countries in the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. Not much is known about Fialka, as it was declassified quite recently in 2005. Translated as Russian for “purple,” Fialka operated on a very similar basis as the previous Enigma machines. Encryption was through an electromechanical process that sent a current through a set of rotors connected by electrical contacts with internal wirings to scramble each letter. The wirings essentially created a particular substitution cipher alphabet, the encrypted output, to correspond with a plaintext alphabet, or unencrypted input. (Singh, 1999)

Fialka, Dave Clausen, Wikipedia, Public Domain The rack of ten rotors can be seen, as well as the typing and print mechanisms

Traditional ciphers have a single “cipher letter” assigned to every plaintext letter, creating a different “output alphabet”, or cipher alphabet. Ciphers like the Enigma took it a step further. The Enigma was so difficult to crack because after each letter was entered, the first rotor would advance to the next rotation and give a completely new cipher alphabet. Further encryption could be created by changing the initial rotor positions and arrangements. However, Enigma only had three rotors, and the British bombe computers developed to find those initial rotor settings were soon capable of deciphering intercepted plaintext within a day. (Singh, 1999)

While Enigma had three rotors (four towards the end of the war), Fialka had ten. Furthermore, each rotor had 30 electrical contacts corresponding to 30 Russian characters. While the design of the machine meant it was more difficult to rearrange the rotors like the Enigma, the sheer number of possible rotor settings compensated for that shortcoming. The internal wires within each rotor were also removable, and could be repositioned in any of the thirty rotations within the external ring on a rotor as well as backwards, creating 60 possible arrangements. Further security is created by a complex drive mechanism that caused alternate rotors to be turned in opposite directions. (Hamer, Perera, 2005)

Aside from being much more secure than Enigma, Fialka was also easier to use. German Enigma machines frequently required two operators since the letters were output by way of a light board on top of the machine. While one operator typed in plain text or a received cipher message, the other would have to record the light board signals. This was slow enough that touch-typing was impossible.

Fialka, on the other hand, used a printer with a paper tape output to facilitate quick encryption and decryption of messages by a single operator. Additionally, the machine both printed and accepted paper punch cards. One advantage that Enigma did have over Fialka, though, was that it was almost half the weight of Fialka. Being made with a primarily metal body and components, Fialka was almost 50 pounds! Granted, the Cold War was not a traditional war with much fighting and battlefield maneuvering so there was not really a need for portability. (Hamer, Perera, 2005)

Cracking Fialka

Cryptanalysis of Fialka was difficult, but not impossible. The ten rotors with 30 character positions each and two ways to slot in the rotor (forwards and backwards) gave a massive number of starting configurations, over 604 quadrillion possibilities! Adding in the later upgrade of a rotor with changeable wirings gives another 403 heptillion, or 403 trillion trillion possibilities. Like in Enigma, the rotors themselves can be rearranged in another ten factorial, or 3.6 million ways. Finally, a day key can be inputted on a punch card that swaps certain letters, functioning like the Enigma’s plugboard. Multiplying, we see that even without the day key, the number of possible starting configurations number in at 8.7 followed by fifty zeroes (Reuvers, Simons, 2009).

Analyzing some operator habits and captured information such as daily key books could reduce this number significantly. For example, while rotating the rotors was simple, taking all ten out and rearranging them was quite a hassle as the design did not allow for individual rotor removal. And as always, with rotor machines the issue of key distribution from higher command to the operators was a constant issue.

Even more helpful was the introduction of more advanced programmable digital computers. Compared to the British bombes in WWII used to find rotor settings for Enigma, digital computers were not physically limited by machinery and could be programmed for multiple tasks. Also, electronic circuitry operated much faster with less possibility of breakdown than a strictly mechanical solution. Indeed, as the NSA developed more powerful computers, the US was able to decrypt Fialka traffic with relative ease by the 1970’s (Courtois, 2012).

The increasing complexity of electromechanical ciphers using rotor technology had its limitations. Israel captured a machine during the 6 Day War in 1967, and the NSA built a computer to decrypt Fialka traffic fairly easily (Courtois, 2012). The fact was, rotor ciphers became so frequently used that finding a method of cryptanalysis was hardly new territory. Rotor machines and electromechanical ciphers had already begun to reach the end of their usefulness when digital computing delivered the deathblow.

The Next Wave in Cryptography

New encryption methods were needed, both for renewed security as well as to keep up with the Digital Age. Claude Shannon, an American mathematician, wrote an essay on “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” (Shannon, 1948). This was a major spark that set off the development of mathematical cryptography using functions and algorithms instead of cipher alphabets. This led to encryption standards such as the Data Encryption Standard and RSA encryption that much of our online communication today is based on.

Fialka was undoubtedly an impressive piece of technology. It was perhaps one of the most advanced rotor machines ever built. However, it suffered from poor timing. Rotor machines had been around for a while. They were initially secure, but the more time passed, the more familiar cryptanalysts became with decryption techniques. Computers merely hastened that end. Fialka was the capstone of the era of electromechanical ciphers, but it was also a harbinger of times to come. When the world experienced the digital revolution, cryptography was carried along for the ride, and Fialka was left behind.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University in honor of the release of The Imitation Game, a major motion picture about the life of British codebreaker and mathematician Alan Turing. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. For more information on the cryptography seminar, see the course blog. And for more information on The Imitation Game, which opens in the US on November 28, 2014, see the film’s website.

Sources:

Courtois, N. (2012, December 28). Cryptanalysis of GOST. 29th Chaos Communications Congress. Lecture conducted from CCH Congress Center, Hamburg, Germany.

Hamer, D. & Perera, T., (2005, January 1). Russian Fialka Cold War era Cipher Machines. Retrieved October 13, 2014, from http://w1tp.com/enigma/mfialka.htm

Reuvers, P., & Simons, M. (2009, October 24). Fialka. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

Shannon, C. (1948). A Mathematical Theory of Communication. ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review, 3-3.

Singh, S. (1999). The code book: The evolution of secrecy from Mary, Queen of Scots, to quantum cryptography. New York: Doubleday.

November 20, 2014

347 if by Land, 588 if by Sea: The Story of the Culper Spy Ring

By Marianna Sharp (Guest Contributor)

It was the summer of 1778, in the midst of the Revolutionary War, and the Americans needed information. Specifically, they needed information about British activities in New York, which served as an important naval base. In order to get it, a Continental officer named Benjamin Tallmadge would recruit his childhood friends and neighbors to create the war’s most successful intelligence network (“The Culper Spy Ring”).

The Continental Army had previously tried to infiltrate New York by sending Nathan Hale to gather intelligence, but the mission suffered from poor planning and worse execution. It did not take long for a British officer to recognize Hale, who was quickly captured and hanged (Wilcox).

“13 Star Betsy Ross Flag” uploaded by Masturbis, Wikimedia Commons

Tallmadge set out to create his network with the problems the Hale mission had encountered on his mind (Wilcox). By utilizing a network of people, with some collecting information and others transporting the information from one location to another, the mission would not depend solely on one man and would not fall apart entirely if a single member was captured. Additionally, they would encrypt their messages so that even if a courier were intercepted by the British any information he was carrying would be unreadable.

Rather than using soldiers, who would have needed to go undercover to carry out their mission, Tallmadge recruited civilians. Many of the group’s members were from Tallmadge’s hometown of Setauket, New York, and were people Tallmadge had known all his life. In fact, Tallmadge’s first agent, Abraham Woodhull, had been his friend since they were children. Woodhull went by the code name Samuel Culper (or Culper Sr.), and today the group is known as the Culper Ring (Wilcox). The network also included business owners located in New York City who could listen in on British conversations and observe some of their activities without arousing too much suspicion.

The Culper Code Book

Because the spies were civilians without any formal training, the encryption system needed to be simple to use—but it also needed to be able to resist cryptanalysis if a message was captured by the British. The solution to this was to utilize a code contained in a numerical dictionary. Tallmadge chose 710 words and 53 proper names and assigned each of them a number from 1 to 763. The list was ordered alphabetically, and members of the ring who had one of the code books could look up the number of each word used in their message. If a number needed to be encrypted (for example, if a spy was relating the number of troops moving in a certain direction) the digits 0-9 were to be replaced with letters in order to avoid confusion (“The Culper Code Book”).

An obvious problem with this method is that, because numbers stand for whole words rather than individual letters, if a word is not in the dictionary there is no way to encode it. Fortunately, Tallmadge also included a substitution cipher for this purpose. A substitution cipher is created by replacing each letter of the alphabet with a different letter (or other symbol). For example, the cipher used by the Culper Ring replaced A with E, J with D, and K with O (“The Culper Code Book”).

On its own, this type of cipher is dangerous to use for matters of military intelligence because it can be easily broken through a process known as frequency analysis. The cryptanalyst analyzes the letters of the intercepted ciphertext and notes the frequency with which each occurs. He then compares these frequencies with the frequencies of each letter in the language of the message.

For example, the letter “E” is the most frequently used letter in the English language, with a frequency of about 12.7%. A British cryptographer looking at messages sent by the Culper Ring would soon notice that the letter “I” was appearing most frequently, and could therefore easily deduce that it represented “E.” This process becomes more and more accurate as more ciphertext using the same cipher is intercepted, and this made the Culver Ring’s cipher even weaker: because they did not change codebooks, their cipher remained the same throughout the war.

However, the strength of the numerical dictionary makes up for this weakness. Cryptanalysts were able to solve ciphers in which each letter is simply replaced by a different letter or symbol but when whole words were encrypted with a single number their methods failed. The contents of the message remained a mystery to all but the intended recipient, who was in possession of the key.

1 if by land, 2 if by sea—Longfellow

e 281 50 347, f 281 50 588—mqpajimmqy

Example of the code and cipher used by the Culper Ring

Although the code was simple to implement, some of the spies in the ring did not always encipher the entirety of their message. For some, this simply meant that a few words, such as “in” or “only,” were written in plaintext—nothing that could give away the purpose of the message. Woodhull, however, would often write almost the entire message in plaintext, using the code only to encipher critical information such as names and dates (Wilcox).

Fortunately for the Americans, there is no record of one of these messages being captured or deciphered by the British. However, it was still a dangerous method, as information about the type of intelligence being collected by the spy ring could still be inferred from such a message. One of the most surprising examples of someone who chose not to use the code is Caleb Brewster. Brewster worked as a spy and courier for the ring and blatantly disregarded the safety offered by the code when signing his letters: he was so confident in his ability to evade capture that he signed his full name rather than using his number, 725 (Wilcox). (Although this confidence may have been unwise it was perhaps justified—the British never did manage to get their hands on Brewster.)

Beyond Encryption: Other Methods to Maintain Secrecy

The Culper Ring used other methods as well which, although not strictly cryptography, still aided them in sending secret messages to one another. For example, Anna Strong, one of Woodhull’s neighbors, used her clothesline to inform couriers of when and where to meet. A black petticoat meant that it was time for a meeting, and the number of white handkerchiefs on the line indicated the location in which the meeting would take place (Wilcox).

The group also made frequent use of steganography, the practice of hiding a secret message within another, seemingly innocent, message. Tallmadge or Washington himself would send what was apparently a shopping list into the city. The list would both serve as an excuse for the courier’s desire to enter the city and as a vehicle for transporting the true message, which was written in invisible ink in between the lines of the list. When the courier left the city, his purchased supplies would include a ream of paper—a few sheets of which contained a reply message in invisible ink (Wilcox).

Throughout the war the Culper Ring was responsible for bringing a wealth of information about British plans and movements to Washington and his army. The security and simplicity of their code allowed the ring’s to easily use civilians as secret operatives writing and carrying sensitive military messages. Although they are often left out of ordinary history classes, the members of the Culper Ring played a vital role in many of the successes of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University in honor of the release of The Imitation Game, a major motion picture about the life of British codebreaker and mathematician Alan Turing. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. For more information on the cryptography seminar, see the course blog. And for more information on The Imitation Game, which opens in the US on November 28, 2014, see the film’s website.

Sources:

Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. (n.d.). The Culper Code Book. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from http://www.mountvernon.org/george-was...

HISTORY. The Culper Spy Ring. (n.d.). Retrieved October 11, 2014, from http://www.history.com/topics/america...

Wilcox, J. (2012). Revolutionary Secrets: The Secret Communications of the American Revolution. National Security Agency. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from https://www.nsa.gov/about/_files/cryp...

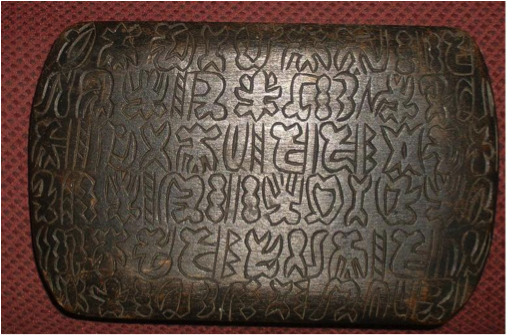

Rongorongo: The Key to Future Cryptography

By Jack Stubblefield (Guest Contributor)

Mystery Language: Rongorongo

If only the Moai statue in the movie, Night at the Museum, had said more than just calling Ben Stiller “Dum dum” perhaps a long lost language could finally have been deciphered. The “Rongorongo” glyphs of Easter Island (indigenously known as Rapa Nui) have remained unsolved for hundreds of years.

Between the years of 300 AD-1200 AD, the Polynesian people migrated and established what is now known as Easter Island (Martin). After an originally successful civilization, the Polynesians overpopulated and overused their resources which resulted in an eventual population decline. In 1722, European explorers further cut into their population by bringing diseases, also giving the island its more popular name “Easter Island”(Martin). Nobody is exactly sure when the Rongorongo texts were written, but historians have determined that the language predates the arrival of the Europeans in the 1700s (Martin).

June 4, 2008 Author: Penarc, creative commons licensed

The major discovery of the Rongorongo glyphs occurred in 1868 almost accidentally. The Bishop of Tahiti was given a strange gift of one of these texts (Martin). The text consisted of hieroglyphic writing carved on a small wooden board. However, he was unable to find anyone on Easter Island who understood the language and could decipher the text due to the fact so many of the indigenous people had been lost to disease and slavery.

Although the Rongorongo texts have never been interpreted, cryptographers and historians have determined certain characteristics of the hieroglyphics. The texts were primarily written as historical accounts of the Polynesian people and were not intended to be secret texts. Rather, they chronicled all the historical events of their civilization. At first, the texts were written on paper created from banana leaves; however, after the leaves started to rot, the King had the elite class rewrite the historical texts onto toromiro wood tablets (Martin).

The major impediment to translating the Rongorongo texts is the sheer number of glyphs. The texts contain over one hundred twenty different basic glyphs with almost five hundred other variations on these glyphs (Stollznow). The glyphs include human and animal forms along with geometric shapes. The animals include many birds while the shapes often represent common items the Polynesian people used on Rapa Nui. Since it is a distinctive language and not a text representing other letters, there is not a special key for decoding it.

It is thought that Rongorongo glyphs may represent idiosyncratic mnemonic devices meant to remind the reader of something that is representative of something else, such as using a “knot” symbol used to represent marriage (Martin). This differs from almost all written forms of languages today that have characters representing only sounds or only letters.

Rongorongo texts contain a mixture of symbols and a phonetic alphabet written in a unique style known as reverse boustrophedon (Ager). The text begins in the lower left corner and is read left-to-right. Then the text must be turned one hundred and eighty degrees to read the next line left-to-right, and the process is repeated with each line.

Many people have tried to decipher the Rongorongo hieroglyphics over the last century and a half but have failed to unlock the mystery of this unique language. Although Rongorongo was not created to hide the meaning of the writer, it has been highly successful in keeping its secrets. If someone is able to finally interpret this language, they could use it to send secret messages and would have an enormous advantage over the cryptanalysts.

For example, during World War II, the United States used the Navajo code talkers to help send messages to American troops overseas (Singh-Chapter 5). Even when the enemy intercepted these messages, they were unable to decipher them because the Navajo language, only spoken and not written, was such an obscure language with no written history. The Navajo code talkers illustrate to us what happens when people use an obscure language with no key to send encoded messages. The United States military was able to expediently send messages to the U.S. army without any worries of cryptanalysts trying to intercept the message.

The Navajo Code is the only wartime code/cipher that was never deciphered by the enemy because our military went to extremes to make sure that a code talker never fell into enemy hands. This could allow the enemy to torture the code talker into giving away some of the secrets of the code allowing a crib to be developed. Even a few words could help the enemy decipher a code. For example, cryptographers were able to use the encrypted annual birthday messages sent to Hitler to decipher parts of the German code because the meaning of the messages was so obvious.

The Future of Cryptography?

If someone was able to use the Rongorongo hieroglyphic language or create a different language that only the sender and receiver know, then it wouldn’t matter if someone intercepted the message because it would be impossible to decipher the message. The interceptor would not be able to decipher the text because there is no key involved in solving the message and no crib could be developed. Using an entirely different language that only the sender and the receiver understand could be groundbreaking because the methods used to decipher a code or cipher would not apply. The only way to break the code would be by knowing the language.

For example, imagine how much more difficult it would have been for the British cryptanalysts in their quest to solve the Enigma machine during World War II if they had not known the German language at all. It would be impossible. This is what makes the Rongorongo texts nearly indecipherable.

For future military actions, many countries should consider using this tactic for sending secret messages. Although it would be time consuming at first to learn an entirely new language that does not relate to any current languages, the result would be worth the difficulties because it would be more efficient in sending quick messages with no concern of interceptors. A new breed of “code talkers” could be used to be dedicated to learning and using the code. The Rongorongo hieroglyphics may show us the next step in cryptography. This could be a check mate for the cryptanalysts because this new innovation in cryptography could put cryptographers ahead in the race for keeping secret messages safe.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University in honor of the release of The Imitation Game, a major motion picture about the life of British codebreaker and mathematician Alan Turing. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. For more information on the cryptography seminar, see the course blog. And for more information on The Imitation Game, which opens in the US on November 28, 2014, see the film’s website.

Sources:

Martin, L. (n.d.). Parrot Time – Issue 5 – Contents. Parrot Time – Issue 5 – Contents. Retrieved October 14, 2014, from http://www.parrottime.com/index.php?i...

Wooden tablet with rongorongo inscription. (n.d.). British Museum. Retrieved October 14, 2014, from http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/...

Ager, S. (n.d.). Rongorongo script.Rongorongo script. Retrieved October 14, 2014, from http://www.omniglot.com/writing/rongo...

Stollznow, K. (2014, August 21). Rongorongo: The Mysterious Writing System of Easter Island. Karen Stollznow. Retrieved October 14, 2014, from http://karenstollznow.com/rongorongo-...

Singh, S. (1999). The Language Barrier. In The code book: The evolution of secrecy from Mary, Queen of Scots, to quantum cryptography. New York: Doubleday.