Holly Tucker's Blog, page 40

January 19, 2015

Beauty Tourism and the Early Modern Beauty Contest

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Before the days of guidebooks and tourist sites, the Eiffel Tower and the Empire State Building, voyagers who traveled for pleasure had different sightseeing practices. One of the most common points of discussion in European travel accounts of the seventeenth century was the beauty of women in foreign lands. Such commentary quickly took on a competitive aspect. Were Italian ladies more beautiful than the French? Could the English ladies compete with the Spanish? Artists rushed to fulfill commissions for portraits that would prove the case.

Postcard beauties

Prominent noblemen, happy to make their own palaces worthy of mention in traveler accounts, set up rooms in their residences devoted to displaying portraits of the most beautiful women of their nation. The Flemish painter Jacob-Ferdinand Voet produced a number of ‘beauties series’ paintings for the private galleries of Italian nobleman. These proved so popular that he was asked to complete similar commissions for the Duke of  Savoy and other European noblemen. The painter Peter Lely, based in London, produced a collection of portraits for the residence of the Duchess of York and the Earl of Sutherland that were dubbed ‘The Windsor Beauties’. (This collection can still be viewed at Hampton Court Palace in England). These portraits were reproduced as prints and circulated by travelers, like postcards.

Savoy and other European noblemen. The painter Peter Lely, based in London, produced a collection of portraits for the residence of the Duchess of York and the Earl of Sutherland that were dubbed ‘The Windsor Beauties’. (This collection can still be viewed at Hampton Court Palace in England). These portraits were reproduced as prints and circulated by travelers, like postcards.

Counterculture Beauty Commentary

Women were able to travel as tourists much more easily by the seventeenth century, as improved roads and regularly scheduled public carriages made it safe and practical for voyagers to travel independently. How did female travelers respond to the fashion of beauties series contests? Some women, like Sophia of Hanover, were known for their fondness for travel. Sophia eagerly entered into the discussion of national beauty competitions. In her memoirs she describes how her hosts would organize beauty contests for her amusement. But she was skeptical of the whole exercise, and she took some pleasure in debunking it. She had already noticed that portraits done of herself in her youth were ridiculously flattering. In fact, she writes, “I was skinny and ugly as a child.” When she traveled to England she reported on her impressions of Queen Henrietta Maria and the ladies of her court, all of whom she had previously seen in popular prints of portraits done by the famous artist Van Dyck. Her commentary is a critique of the portraits as well as the whole pretense of the beauty contest:

“The fine portraits by Van Dyck had given me a lofty idea of the beauty of all English ladies. I was therefore surprised to discover that the Queen, so beautiful on canvas, was actually a short woman … with long wizened arms, crooked shoulders, and teeth portruding from her mouth like ravelins from a fortress.”

“The fine portraits by Van Dyck had given me a lofty idea of the beauty of all English ladies. I was therefore surprised to discover that the Queen, so beautiful on canvas, was actually a short woman … with long wizened arms, crooked shoulders, and teeth portruding from her mouth like ravelins from a fortress.”

For further reading:

Sophia of Hanover, Memoirs. Ed. and trans. Sean Ward (2013)

Melville, Lewis. The Windsor Beauties: Ladies of the Court of Charles II (2005)

January 17, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xii

By April Stevens (W&M Editorial Assistant)

The dawn of a new year always seems to invite a reflection on the past. 2015 is no different. This year historians have already shared some new, but very old treasures that give us a new perspective on the past.

Saint Peter

New Year, New Discoveries

The Museum of Somerset in Taunton, England has acquired an Anglo-Saxon sculpture of Saint Peter that a local builder had been using as a grave marker for his cat. The Museum dates the sculpture to around AD 1000, but cannot say where exactly the sculpture was from.

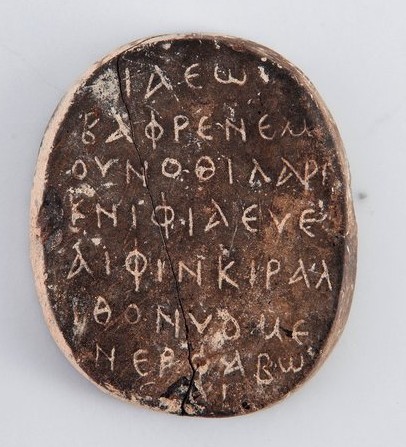

Palindrome on Amulet

In Cyprus, archaeologists unearthed a 1500 year old amulet containing a curious inscription, a 59-letter palindrome, or a message that reads the sam backwards as forwards. The other side of the amulet features several images, including Harpocrates, the god of silence, and a bandaged mummy, likely Egyptian God Osiris.

A Fresh Look on History

On January 6, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston opened a time capsule placed under the the State House cornerstone in 1795 by Samuel Adams, patriot Paul Revere, and Colonel William Scollay. The capsule, containing coins, medals, newspapers, and documents, was opened once before in 1855, when the contents were cleaned and additional objects were added. To watch the opening of the capsule yourself, check out this video.

Statue of Cangrande

Historians continually look for new ways to solve some of histories mysteries, and recently researchers solved a Medieval murder using mummified feces! Since 1329, the sudden death of warrior, autocrat, and Dante’s patron Cangrande della Scala’s was an unsolved controversy. Yet, recent analysis of fecal matter shows that he was in fact most likely poisoned with foxglove.

Some historians are rethinking woman’s role in the Roman military. Traditionally, it was believed that Rome’s total ban on marriage originally put in place by emperor Augustus meant that there were no women attached to the military. However, taking a fresh look at roman forts and even art has led some historians and archaeologists to believe that many Roman soldiers circumvented the ban on marriage.

Have you enjoyed these modern perspectives on history? Share your own new findings in the Comments below and come back to Wonders & Marvels each week for more fresh takes on history!

If you just can’t wait to read more, check out these recent posts:

Don’t forget to register for this month’s Book Giveaway here!

January 16, 2015

Facing Fear

from Le Mécanisme de la Physionomie Humaine (1862)

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

Most adults are adept at reading facial expressions. A smile communicates openness or mirth, and we can infer from photographs of human faces if the subject is shocked, for example, or experiencing disgust or sadness. Even in the nineteenth century, there was evidence that common facial expressions were universal, and not learned from mimicry. It is consequently unsurprising that many scientists of that period saw the human face as a window into the soul.

Physiognomy: the analysis of the facial characteristics

For physiognomists, the face was the key to an individual’s personality and moral character. Charles Darwin’s half cousin, Sir Francis Galton, used composite images of faces to map character types, for example, and criminologists pored over early mugshots of convicts in order to delineate “criminal” measurements and proportions. For the doctor Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne, however, the capacity of every human face to convey inner emotion was a more intriguing subject for research. He was interested not in what made faces remarkable and distinctive, but in the universal—and in his conviction, God-given—array of facial expressions.

Duchenne was an expert in theoretical and practical neurology, a discipline that he pioneered alongside his more famous colleague Jean-Martin Charcot, and his research on facial expression focused on the nerves that produced expressions. He wanted to understand the anatomical mechanisms whereby facial expressions were produced, and to do this, used electrical stimulation of particular muscles to reliably recreate them.

“The old man”

This well-known photograph shows Duchenne performing this experiment on a patient he called “the old man.” It is a startling photograph, because the horror on the man’s face seems to reflect back our own. The image looks simultaneously like torture and like an exquisite studio portrait, and the contrast is disquieting. When Duchenne explained his choice to use the new medium of photography on the grounds that it could produce an image “like a mirror”, he likely did not have this effect in mind. Duchenne was not insensitive to the apparent cruelty of his technique, however: he explained in the 1862 publication in which the photograph was printed that “the old man” suffered from an anesthetic condition of his face which prevented him from feeling pain. Nonetheless, the exposure time required to produce such a clear photograph in the 1860s was such that this cannot have been a comfortable procedure.

In 1862, this image represented both the most advanced neurological knowledge and the most groundbreaking visualization technology available. It makes one wonder whether, say, an MRI scan, might appear as bizarre and oddly fascinating a relic in 150 years.

January 15, 2015

Death by Crinoline

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

Perils of the Era

Cartoon in Punch Magazine, which frequently lampooned crinoline.

In addition to smallpox, cholera, and consumption, Victorian era denizens had to consider the perils of crinoline, the rigid, cage-like structure worn under ladies’ skirts that, at the apex of its popularity, reached a diameter of six feet. The New York Times first reported the phenomenon of crinoline-related casualties in 1858, when a young Boston woman, standing by the mantel in her parlor, caught fire and within minutes was entirely consumed by flames—an unfortunate incident that came on the heels of nineteen such deaths in England in a two-month period. Witnesses, impeded by their own crinolines, were forced to watch the victims burn. “Certainly an average of three deaths per week from crinolines in conflagration,” the Times admonished, “ought to startle the most thoughtless of the privileged sex.” A similar tragedy occurred shortly thereafter in Philadelphia, when nine ballerinas burned to death at the Continental Theatre.

Non-fatal consequences of crinoline included entanglement in carriage wheels and being toppled by strong winds, often with mortifying consequences. Such was the case with Consuelo Montagu, the Duchess of Manchester, who snagged her hoops while climbing over a stile and landed upside down, revealing a pair of scarlet knickers. “I wish that people who wear crinoline could see the indecency of their own dress as other people see it,” wrote Florence Nightingale in her 1859 book, Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. “A respectable elderly woman stooping forward, invested in crinoline, exposes quite as much of her own person to the patient lying in the room as any opera dancer does on the stage. But no one will ever tell her this unpleasant truth.”

Advantages (In the Face of Sartorial Danger)

Nevertheless, crinoline offered some marked advantages over the traditional mode of dressing. It was much lighter and cooler than numerous petticoats suspended from a corseted waist, and, with the invention of the sewing machine in the 1850s, was able to be mass-produced. At the onset of the Civil War, resourceful Southern women discovered new and unexpected benefits of the contraption when they “ran the blockade,” circumventing President Lincoln’s strategy of preventing goods from reaching the Confederate states. One managed to conceal inside her hoop skirt a roll of army cloth, several pairs of cavalry boots, a roll of crimson flannel, packages of gilt braid and sewing silk, cans of preserved meats, and a bag of coffee—the contraband tally for a single crossing. Others tied sabers and pistols around the coils, smuggling small arsenals across the lines. Northern newspapers regularly described the “Secesh in petticoats” who artfully stuffed dozens of bottles of precious quinine beneath their skirts.

The backlash against crinoline intensified during and after the war. Ministers took to the pulpit to warn that wearing hoops was akin to renouncing Christianity. The fad was a “social evil” almost on par with smoking, spitting, and whoring, and women who wore crinoline did so with complete disregard for society. “We have seen the choicest flowers in our gardens and the most cherished plants in our greenhouses cut off by the hoop,” opined The Guardian. “Our wardrobes afford no room for our cloths, because the women of the family want more space than they can get. For five years we have no had room to turn ourselves round in our own homes.” The crinoline craze, or “crinolinemania,” as it was called, waned in the late 1860s, only to threaten revival thirty years later during what would become the heyday of the bustle (Mrs. Grover Cleveland was adamantly anti-crinoline), and again in the 1910s, just before the flapper would change women’s fashion for good. “Greatly daring are the women of today,” declared the New York Times in 1925. “And how they pity their ancestors in crinoline.”

Sources:

Books: Alison Gernsheim, Victorian & Edwardian Fashion. New York: Dover Publications, 1981; Susan J. Vincent, The Anatomy of Fashion. New York: Berg, 2009. Florence Nightingale, Notes On Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. London: Harrison, 1859.

Articles: “Christianity and Crinoline.” New York Times, September 15, 1858; “The Shocking Age.” New York Times, September 20, 1925; “Crinoline: A Real Social Evil.” The Guardian, October 16, 1861; “Mrs. Cleveland Against It.” New York Times, February 19, 1893; “The Perils of Crinoline.” New York Times, March 16, 1858; “Secesh in Petticoats.” New York Times, November 2, 1862.

January 13, 2015

What is Beauty?

By David Konstan (Regular Contributor)

Aphrodite’s beauty attracts the erotic gaze of Pan. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece. Credit: Marie Mauzy / Art Resource, NY.

The English word “beautiful” is very broad: it may refer to an attractive woman or, somewhat less frequently, an attractive man, but it is also a fundamental concept in aesthetics, used of artworks of every sort. We speak of landscapes and flowers and sunsets as beautiful, and even more abstract items such as ideas or mathematical proofs, and also of spiritual qualities, often in religious contexts and opposed to carnal beauty (think of the beauty of the Virgin Mary). But does “beauty” or “beautiful” mean the same thing in these various uses? What does the sex appeal of an actress have to do with the ethereal beauty of a saint? Is a brilliantly executed work of art beautiful, even if it represents objects that in themselves appear ugly or distasteful?

Did ancient Greeks face the same questions about beauty as we do today? It turns out that they did not, or not in these terms. This question is challenging because the Greek vocabulary does not seem to have a proper word for beauty at all. Rather, the term that scholars have examined meant something like “fine” or “noble,” and could be used so generally that it eclipsed even the modern breadth of the word “beauty.” Indeed, some people (among them Umberto Eco) have concluded that the Greeks did not seem to have a concept of beauty at all.

Beauty As a Product of Sexual Desire

Well, there was a word that did come closer, kállos, and curiously it had been all but ignored and never treated as a concept on its own. An analysis of its uses indicates that the Greeks thought of beauty, or what they called beauty, as closely connected to the visual, and to sexual allure in particular; that is why it was more likely to be ascribed to women and boys – the objects of erotic desire in the classical Greek way of thinking – than to adult males. Even women were imagined as preferring boyish looks over macho musclemen: they were more likely to lust after a pale, un-athletic adolescent than a he-man like Hercules.

True, the Greeks could speak of works art, and even of virtues, as possessing beauty, but even in these extended uses the term never lost its association with attractive proportions, on the model of the human figure. Beauty implied desire, even when the object was as transcendental as God. The modern notion of disinterested contemplation was foreign to the classical Greek conception of aesthetics, and so the conundrums mentioned at the beginning of this post never seem to have worried them.

This understanding of Greek beauty begs the question: does classical Latin present the same configuration? To make this comparison we must turn, in part, to the Bible, which is the fullest literary text we have in parallel Greek and Latin versions, as well as Hebrew. The findings are surprising, for it turns out that the Hebrew vocabulary for beauty matches up very well with the Greek. The Latin term has proved somewhat different, despite the powerful influence of Greek thought on Roman ideas. It is this transition of Greek ideas into the Latin West that explains how Western ideals of beauty have shifted over time.

For further reflections on how and why ancient Greek conceptions of beauty gave way to the more problematic status of beauty in modern aesthetics, take a look at my new book: Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. It’s an interesting story.

David Konstan is the author of Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea (Oxford University Press). He is Professor of Classics at New York University and Emeritus Professor of Classics at Brown University. His previous books include Before Forgiveness, The Emotions of the Ancient Greeks, and Friendship in the Classical World.

David Konstan is the author of Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea (Oxford University Press). He is Professor of Classics at New York University and Emeritus Professor of Classics at Brown University. His previous books include Before Forgiveness, The Emotions of the Ancient Greeks, and Friendship in the Classical World.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on January 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

December Book Giveaways

David Konstan, “Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea”

January 12, 2015

Agnodice: Down and Dirty?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

So there I was watching a superb drag burlesque act, The Down and Dirty Show, featuring The Gentleman King and Foxy Tann, the scheduled entertainment at the 2011 Berkshire Conference for Women Historians. And the sky opened. Sometimes moments of insight come when you least expect them.

How many times have you assumed that the person walking down the street in front of you was a man, and then when the person turned round you realized it was a woman? We read various cues, but then we have to change our minds. In this show, men became women who became men again in front of our eyes; which raised the question, were they men to begin with? Gender was most emphatically shown as something to be performed, meanings shifting with clothing and context, so that binaries dissolved and the world became a very different place.

And suddenly the imaginary ancient Greek midwife on whom I was writing a book, Agnodice, started to mean something very different. My main research question had never been the traditional one, namely ‘Was Agnodice a real person, a pioneering midwife who fought for the right of women to attend those giving birth?’ That question, the one asked by existing articles and books aimed at midwives, is I think a dead end. Of course this young girl, who is supposed to have disguised herself as a man to learn medicine and then practiced her profession until accused by jealous rivals, never existed. The story, culminating in her displaying her body to the court to prove she is really a woman and can’t have been seducing female patients, has many of the features of an ancient novel.

Having a ‘founding father’ for a profession is traditional, so claiming Agnodice as ‘first midwife’ just plays the same game as medicine and its specialisms: from Hippocrates as ‘father of medicine’ to Robert Koch as ‘father of microbiology’. Such games involve consolidating an identity for a newly emerging specialism, or making nationalist claims to precedence in a contested field. I was always more interested in how people over the last 500 years or so had refashioned Agnodice: was she, they wondered, a midwife or a female doctor? How that question has been answered can help us think today about debates over what midwifery is, how gender is relevant, and where the professional boundaries between midwives and doctors should be drawn.

One of the aspects of Agnodice in modern discourse that most fascinates me is her use in the name of the excellent Agnodice Foundation, a Swiss group working for the integration of those who are transsexual, intersex or transgender. I asked their founder, Dr Erika Volkmar, why Agnodice had been chosen. She was well aware that the story is a myth but replied that ‘We can assume that if Agnodice was successful in practicing OBG as a man, she must have been at least very androgyne and gender variant … Agnodice is perfect as she was both gender variant AND an outstanding professional. Equally, our foundation council is composed of a majority of great professionals with atypical gender identity. She is a model because as a gender variant person she obtained a major victory against the prejudice and sexism of our society, i.e. making medical studies accessible to women.’

The Agnodice Foundation is not the first to take Agnodice as gender variant. Here is James Sprague in 1912 imagining Agnodice speaking:

And so I reasoned, ’twas a blunder made, for which the gods were not responsible. Dame Nature ’twas who in erratic mood had linked a man’s mind to a woman’s form. And none suspected, none in all these years, the secret of my sex. Oh, strange indeed, the ways of gods are not like those of men — that by mere change of garb a woman is transformed into the semblance of a man, and that great inner difference concealed !

Her sex is female, in bodily terms, but here her mind is not. Would she have wanted to change her body to match her mind, had such an option been available to her? And it’s not just Agnodice’s mind that is male: for Sprague the court hears a voice whose full, rich, swelling tones were like unto an organ’s.

What The Down and Dirty Show showed me is that assuming that Agnodice was easily able to pass for a man because she was gender variant may make us miss an even larger point; namely, that gender is always potentially ambiguous. How do we read the signs? We assume we know who the boys are and who the girls are, but it only takes a change of dress or hairstyle or gesture and our carefully constructed binaries fall apart. Seeing Agnodice as gender variant glosses over the inadequacies of gender binaries, in history and today.

Sprague, James S., ‘Agnodice’, Dominion Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal, 38 (1912): 13–17.

Agnodice: down and dirty?

by Helen King

So there I was watching a superb drag burlesque act, The Down and Dirty Show, featuring The Gentleman King and Foxy Tann, the scheduled entertainment at the 2011 Berkshire Conference for Women Historians. And the sky opened. Sometimes moments of insight come when you least expect them.

How many times have you assumed that the person walking down the street in front of you was a man, and then when the person turned round you realized it was a woman? We read various cues, but then we have to change our minds. In this show, men became women who became men again in front of our eyes; which raised the question, were they men to begin with? Gender was most emphatically shown as something to be performed, meanings shifting with clothing and context, so that binaries dissolved and the world became a very different place.

And suddenly the imaginary ancient Greek midwife on whom I was writing a book, Agnodice, started to mean something very different. My main research question had never been the traditional one, namely ‘Was Agnodice a real person, a pioneering midwife who fought for the right of women to attend those giving birth?’ That question, the one asked by existing articles and books aimed at midwives, is I think a dead end. Of course this young girl, who is supposed to have disguised herself as a man to learn medicine and then practiced her profession until accused by jealous rivals, never existed. The story, culminating in her displaying her body to the court to prove she is really a woman and can’t have been seducing female patients, has many of the features of an ancient novel.

Having a ‘founding father’ for a profession is traditional, so claiming Agnodice as ‘first midwife’ just plays the same game as medicine and its specialisms: from Hippocrates as ‘father of medicine’ to Robert Koch as ‘father of microbiology’. Such games involve consolidating an identity for a newly emerging specialism, or making nationalist claims to precedence in a contested field. I was always more interested in how people over the last 500 years or so had refashioned Agnodice: was she, they wondered, a midwife or a female doctor? How that question has been answered can help us think today about debates over what midwifery is, how gender is relevant, and where the professional boundaries between midwives and doctors should be drawn.

One of the aspects of Agnodice in modern discourse that most fascinates me is her use in the name of the excellent Agnodice Foundation, a Swiss group working for the integration of those who are transsexual, intersex or transgender. I asked their founder, Dr Erika Volkmar, why Agnodice had been chosen. She was well aware that the story is a myth but replied that ‘We can assume that if Agnodice was successful in practicing OBG as a man, she must have been at least very androgyne and gender variant … Agnodice is perfect as she was both gender variant AND an outstanding professional. Equally, our foundation council is composed of a majority of great professionals with atypical gender identity. She is a model because as a gender variant person she obtained a major victory against the prejudice and sexism of our society, i.e. making medical studies accessible to women.’

The Agnodice Foundation is not the first to take Agnodice as gender variant. Here is James Sprague in 1912 imagining Agnodice speaking:

And so I reasoned, ’twas a blunder made, for which the gods were not responsible. Dame Nature ’twas who in erratic mood had linked a man’s mind to a woman’s form. And none suspected, none in all these years, the secret of my sex. Oh, strange indeed, the ways of gods are not like those of men — that by mere change of garb a woman is transformed into the semblance of a man, and that great inner difference concealed !

Her sex is female, in bodily terms, but here her mind is not. Would she have wanted to change her body to match her mind, had such an option been available to her? And it’s not just Agnodice’s mind that is male: for Sprague the court hears a voice whose full, rich, swelling tones were like unto an organ’s.

What The Down and Dirty Show showed me is that assuming that Agnodice was easily able to pass for a man because she was gender variant may make us miss an even larger point; namely, that gender is always potentially ambiguous. How do we read the signs? We assume we know who the boys are and who the girls are, but it only takes a change of dress or hairstyle or gesture and our carefully constructed binaries fall apart. Seeing Agnodice as gender variant glosses over the inadequacies of gender binaries, in history and today.

Sprague, James S., ‘Agnodice’, Dominion Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal, 38 (1912): 13–17.

January 8, 2015

The Puppy Water and Other Early Modern Canine Recipes

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

At first I thought it was a joke when I read a recipe for “The Puppy Water” in a recipe collection compiled by one Mary Doggett in 1682. “Take one Young fatt puppy and put him into a flatt Still Quartered Gutts and all ye Skin upon him”, then distill it along with buttermilk, white wine, pared lemons, herbs, camphire, venus turpentine, red rosewater, fasting spittle, and eighteen pippins.

Saint Roch: The story goes that a dog saved Roch from the plague by licking his wounds. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Although Mary Doggett’s recipe does not specify purpose, puppy water was a facial treatment – as immortalized by Jonathan Swift in his poem, “The Lady’s Dressing Room” (1732):

There Night-gloves made of Tripsy’s Hide,

Bequeath’d by Tripsy when she dy’d,

With Puppy Water, Beauty’s Help

Distill’d from Tripsy‘s darling Whelp.

Swift also, however, refers to another canine usage: gloves made from dog’s hide. As noted in Nicholas Culpeper’s Pharmacopoeia Londinensis (1718), “little puppy dogs” (and various other animals, such as hedge-hogs, snails, foxes, moles, frogs, or earthworms) “may be made beneficial to your sick bodies”. Robert James’s entry for “Canis” in his Medicinal Dictionary (1743-5) explained that Europeans “generally abstain from Dogs Flesh, till Necessity… obliges them to use it.” But use it they did: the flesh, fat, skin and excrement could all be incorporated into medicines recommended even by renowned medical practitioners.

These remedies ranged from the foul: Culpeper’s Oleum Catellorum (Oil of Whelps) “to bath the Limbs and Muscles that have been weakened by wounds or bruises” or George Bate’s gargle for mouth ulcers and thrush that included a white dog turd (Pharmacopoeia Bateana, 1706). To the cruel: Philip Woodman suggested cutting a live puppy lengthwise through the middle and applying it hot to the head to treat a frenzy (Medicus Novissimus, 1712). To the comforting: for iliac passion (intestinal obstruction), Thomas Sydenham instructed that a live puppy should be laid to the patient’s naked belly for two or three days (Praxis Medica, 1707).

James’ dictionary entry explained the rationale for these treatments. For example, keeping a warm puppy next to one’s colicky belly or gouty leg provided “kindly and cherishing Heat”, but it also worked sympathetically by transferring the disease into the animal instead.* Having a dog lick one’s wounds and ulcers could cure them more quickly. The fat of the dog was thought to be better externally than any other animal fat, owing to its penetrating quality, and the drippings could be eaten to treat lung problems or epilepsy. Turned into gloves, the skin of the dog would reflect summer sun; as a piece of leather, it could protect gouty or arthritic legs from cold. Dog dung, being hot and acrid, might treat internal bleeding or toothache.

James did not mention “The Puppy Water” itself. However, for that we might look to the ancient Greeks whom he did discuss. According to Hippocrates, “the Flesh of Dogs is of a heating, drying, and corroborating Nature… whereas that of whelps is of a moistening, lubricating Quality.” The other ingredients in the recipe point to a similar use as the puppy: pippins were moistening and good against inflammation; fumitory and agrimony treated diseases of Saturn (such as old age) and were strengthening and cleansing; plantain firmed the sinews and helped skin problems. Just the thing for a face wash!

*The evidence for this is dubious. James recounted the case of a patient in 1742 being salivated (by mercury). When a visitor arrived, the patient put aside his basin filled with his saliva, which his dog proceeded to drink. Within ten hours, the dog suffered from convulsions and died.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in May 2012.

January 5, 2015

Were Ancient Amazons Giants?

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Were the Amazons, those famous fighting females of Greek myth, giant women? In popular culture we often use the word “Amazon” for exceptionally tall, robust, athletic women. And it is commonly believed that the mythic Amazons were giantesses.

Where does this image originate? In classical antiquity, the Greeks pictured the great heroes and heroines of the glorious days of myth as giants, at least 3 times bigger than ordinary men and women. That means the Greeks imagined Heracles, Achilles, and Atalanta as larger-than-life figures of superhuman strength compared to puny men and women of the present day. And since the celebrated heroes of myth battled fierce Amazons, their equals in physical strength, those formidable women were also assumed to tower over ordinary people.

The idea that heroic mythic figures were larger than life was confirmed by ancient discoveries of enormous fossilized bones of prehistoric animals that the Greeks had never seen alive. Whenever Greeks came across the huge and unfamiliar bones of long-extinct mammals of immense size, turned to stone and weathering out of the ground all around the Aegean, people identified them as the relics of mythic heroes. The fossil femurs and shoulder blades of extinct mammals resembled the limb bones of humans except that they were about 3 times the size! Such impressive remains of heroic dimensions were gathered up and displayed in temples as the bones of mythic characters like Achilles, Theseus, Orestes, and Ajax.

On the island of Samos, the Greeks discovered evidence to prove that the fearsome Amazons were giants too. According to myth, the god Dionysus was attacked by an army of Amazons on Samos. There was a ferocious battle, so bloody that the very earth was stained red. And ever after, people on Samos found colossal bones eroding out of the reddish sediments of the battleground. The huge bones were believed to be those of the Amazons slain by Dionysus.

In the 1970s, German archaeologists excavating the great Temple of Hera on Samos discovered an “Amazon”-sized femur on the altar, among many other items dedicated to the goddess in the sixth century BC. The Amazon’s thigh bone was really that of a prehistoric giant rhinoceros or mastodon, brought to the temple from the abundant fossil deposits of gigantic Miocene mammals that populated the island about 8 million years ago. More than 2,500 years ago someone placed it on the altar as a sacred memento of the Battle between the Amazons and Dionysus.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014) and “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

December 31, 2014

Pop Open the Champagne!

By Tilar Mazzeo (Guest Contributor)

The BBC reported this summer that the owner of a castle in Scotland discovered a bottle of unopened 1893 Veuve Clicquot champagne, the oldest known to exist. The lucky laird gave the bottle to the champagne house, where it is now on display as part of their historical exhibit.

And since much of the value in this special bottle is the fact that it was preserved unopened, chances are slim that this bubbly will ever find its way to a glass. But if it were poured, what would nineteenth-century champagne look and taste like?Veuve Clicquot champagne started using its trademark yellow label sometime in the mid-1860s, and, since it was used exclusively in the beginning to advertise a drier style of champagne to the English market, chances are the wine in this newly discovered bottle is brut champagne.

And since much of the value in this special bottle is the fact that it was preserved unopened, chances are slim that this bubbly will ever find its way to a glass. But if it were poured, what would nineteenth-century champagne look and taste like?Veuve Clicquot champagne started using its trademark yellow label sometime in the mid-1860s, and, since it was used exclusively in the beginning to advertise a drier style of champagne to the English market, chances are the wine in this newly discovered bottle is brut champagne.

The term is a bit relative. Today, brut champagne is a dry wine. But, in the nineteenth century, folks drank their bubbly cold and sweet. An average bottle of champagne for the Russian market, for example, had as much as 300 grams of residual sugar—which is about twice what we find today in sweet dessert wines.

And since champagne then was almost always a dessert wine and not an aperitif, that makes sense. Most champagne at the time was made in the style known as blanc de noirs—a white wine make with a mixture of red and wine grapes. But, in fact, calling this bottle a white wine is probably something of a misnomer. Imbibers expected their champagne to have a rosy tinge, something a quick trip to the Oxford English Dictionary will confirm.

There are early records showing that bubbly was often served as something resembling frozen slush, with that same viscosity that comes after a good bottle of vodka has been sitting the freezer for weeks. So we’d try it cold, something that’s not ideal for bubbles, of course. On the other hand, champagne then didn’t have the same sort of aggressive bubbles we find today in commercially produced sparkling wine either. The quality of the glassware wasn’t strong enough to withstand the intense pressure created by strongly carbonated wines.

We’d probably serve it in those shallow champagne goblets known as coupes and modeled, or so the legend goes, on the much-admired breasts of Madame de Pompadour. Until the Widow Clicquot discovered remuage—a system for efficiently clearing champagne of the yeasty debris that is a by-product of those bubbles—sparkling wine was often served in small, opaque V-shaped pilsner glasses, meant to disguise the floating sediment. By the middle of the century, champagne was reliably clear, and, although flutes existed, the preference was for coupes well into the mid-twentieth century.

Even if someone opens this newly discovered rarity, we won’t be among the lucky few to taste a drop. But what good historian doesn’t want to imagine this kind of first-hand research?

Tilar J. Mazzeo is the author of The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (HarperCollins 2008) and the travel guide to The Back-Lane Wineries of Sonoma (The Little Bookroom / Random House 2009). She teaches English at Colby College.

Tilar J. Mazzeo is the author of The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (HarperCollins 2008) and the travel guide to The Back-Lane Wineries of Sonoma (The Little Bookroom / Random House 2009). She teaches English at Colby College.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in December 2008.