Holly Tucker's Blog, page 38

February 23, 2015

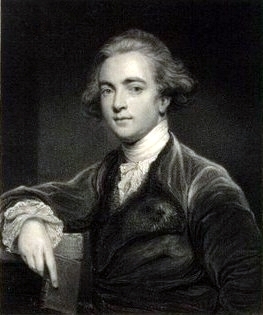

“Oriental” Jones

Sir William Jones (1746-1794), known to his contemporaries as “Oriental” Jones, was one of the great eighteenth century polymaths. He was a linguist, what was then called an Orientalist,* and a successful public intellectual–the kind of scholar who is able to make abstruse topics not only accessible but exciting.

Jones started early with his love of language: he reportedly learned Persian from a Syrian merchant in London and translated the poems of Hafiz into English at the age of sixteen . Over the course of his life he studied twenty-eight languages including not only Latin and Greek, but German, French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian and Turkish, several South Asian languages, and a smattering of Chinese.

By the time he received his bachelor of arts from Oxford in 1768, Jones had already become known as a scholar of all things “Oriental”–by which he and his contemporaries meant South Asia and the Middle East. The King of Denmark hired him to translate a biography of the emperor Nadir Shah from Persian into French. Published in 1770, the translation secured Jones’ reputation as translator and linguist. He was only 24.

Over the next thirteen years, Jones published a number of works related to the language and culture of the Islamic world , including the authoritative A Grammar of the Persian Language (1771), which he later translated into French, and a translation of seven famous pre-Islamic poems from Arabic that Tennyson later claimed as an inspiration . During this period, he also published a volume of his own poetry , in which he combined classical conventions with Islamic themes and imagery. (Anyone feeling a tad inadequate at this point will be pleased to know that his poems are workmanlike but not inspired. His biographer describes them as “minor classics”, but that’s generous.)

Like many a modern adjunct professor, Jones soon found it was difficult to make a living as an independent scholar, so he turned to the study of law. He was called to the bar in 1774. Working as a barrister, an attorney, and an Oxford fellow, he made a name for himself as a legal scholar and translated manuscripts in his spare time. He also became known for his pro-American sympathies, traveling to Paris three times during the American Revolution to meet with Benjamin Franklin regarding the military and political situation. In fact, it was rumored that he intended to emigrate America to help write the new country’s constitution. (The mind boggles at the image of Jones and Madison in collaboration.)

It was perhaps inevitable that a cash-strapped attorney with a talent for languages and a fascination with the Orient would end up in India in the service of the British East India Company.* Jones was engaged to be married,but didn’t have the income to support a wife. When a lucrative job as a judge on the supreme court of the British East India Company’s Bengal Presidency became available, he asked his friends to help him secure the position. Evidently his reputation as a legal scholar and Orientalist outweighed his reputation as a pro-American troublemaker. In 1783, Jones and his new wife sailed to Calcutta.

If Jones had not already earned the nickname “Oriental”, he certainly deserved it after his arrival in India. Many employees of the British East India Company hired local instructors to help them with Bengali, Hindi or Persian. Jones took the unusual step of adding Sanskrit to the list, making him the second Englishman known to have learned the language. During his eleven years in Calcutta, Jones founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal–a Calcutta variation on the Royal Society with an emphasis on “oriental” subjects. In addition to his semi-official work on Indian legal systems, he wrote extensively on Indian history, religion, languages, literature, botany and music. He translated a number of works of Indian literature into English, including Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda , the collection of fables known as the Hitopadesa, and the Laws of Manu, the first step in a compilation of Hindu and Muslim law intended to improve justice in British courts in India.

His most influential translation was Sakuntala, the masterwork of fourth century Indian poet and playwright Kalidasa, whom Jones described as “the Shakespeare of India”. Published in 1789, Jones’ Sakuntala went into five editions in twenty years–a best seller in eighteenth century terms–and was translated into German in 1791 and French in 1803. It is considered one of the most important influences on the first generation of Romantic poets

Most important, his study of Sanskrit led Jones to postulate a common source for what came to be known as the Indo-European languages. In his 1786 presidential discourse to the Asiatic Society, Jones described the relationships he had found between Sanskrit, Latin and Greek, which he believed were too strong to be accidental, and suggested that they not only had “some common source, which perhaps no longer exists”, but were also related to the Gothic, Celtic and Persian languages. That single paper was the beginning of comparative philology

Jones died in Calcutta in April, 1794, exhausted by his twin pursuits of legal studies and Orientalism. His digest of Indian legal systems was incomplete, but he had effectively founded the academic disciplines of comparative philology and Indology (South Asian studies in modern college catalogs) and introduced the first generation of Romantic poets to a broader vision of the world.

* For purposes of this blog post, I am going to ignore the complications that now surround the term Orientalism. Otherwise we’ll be here all day.

**Just a reminder, at this point India was not a colony of the British government. The British East India Company held the right to administer various regions of the subcontinent as a vassal of the Mughal emperor. While this would increasingly become no more than a political fiction, in the 1780s it was still very much a political reality.

February 20, 2015

Invading Species

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

“They make people uncomfortable. We don’t know what they think, how they think, what they do…so…they are going to make us unsafe. Sometimes they will do things that you don’t think they will do and then we will be in trouble…”

In Neill Blomkamp’s short film, Alive in Joburg (2005), which inspired his later blockbuster, District 9, a man shares this observation in a documentary–style interview. In the film, he is describing stranded aliens, who live in slum-like conditions in Johannesburg. An elderly lady complains that their arrival brought rape and crime, and a butcher mans his stall wearing a bulletproof vest, to protect himself and his meat from violent attack.

Illegal Aliens

The apartheid context is an obvious subject of the film, but it addresses xenophobia as well as racism: the script for Alive in Joburg was based on interviews with South Africans about Zimbabwean and Nigerian immigrants. The filming of District 9, released in 2009, was disrupted by anti-Zimbabwean riots in response to an outbreak of cholera in Zimbabwe in 2008. Concerns that Zimbabweans might bring disease into South Africa led to calls for the border to be closed and for Zimbabweans to be denied entry into the county, a call that was echoed in many countries globally in response to the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014.

Alien Disease

Although it was established in the mid-nineteenth-century that cholera was waterborne, the associated stigma remained prevalent, and misguided policies of isolating sufferers and suspected carriers continued. In her book, Gypsies in Germany and Italy, 1861-1914: lives outside the law, Jennifer Iluzzi describes how an outbreak of cholera in Apulia in 1910 became a premise to justify the mistreatment and deportation of “gypsies” who could not prove Italian provenance. In August 1910, the group of “Russian Gypsies” blamed for the outbreak in Apulia was reportedly isolated on boat in the Adriatic, where they were being “maintained” by the authorities, who had burned all of their possessions and food. Even after this measure failed to slow the epidemic, the accusation of spreading cholera was still employed to accelerate the expulsion of people identified as zingari.

While visiting aliens remain a fiction, invading viruses and bacteria are ubiquitous and multiplying. There is a long tradition in modern history of identifying individuals with a pathogen they purportedly carry and using the rhetoric of hygiene to justify their exclusion. The international panic seeded by Ebola and the suspicion under which infected travelers fell are a reminder of how powerful that impulse remains.

For more on policies toward Gypsies in Italy and Germany, see:

Jennifer Illuzzi, Gypsies in Germany and Italy, 1861-1914: lives outside the law (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014)

February 19, 2015

Hendrik Cesars and the Tragedies of Race in South Africa

By Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully (Guest Contributors)

When we began researching our biography of Sara Baartman we thought we knew what we would find. Two white men brought Sara Baartman to 19th-century London, where she was put on show in Piccadilly. Every study, every bit of popular knowledge representing Sara Baartman’s life as the “Hottentot Venus,” had said so.

When we began researching our biography of Sara Baartman we thought we knew what we would find. Two white men brought Sara Baartman to 19th-century London, where she was put on show in Piccadilly. Every study, every bit of popular knowledge representing Sara Baartman’s life as the “Hottentot Venus,” had said so.

Newspapers in London at the time described Hendrik Cesars as a colonist. The extraordinary efforts to return Baartman’s remains, beginning soon after South Africa’s first democratic elections and ending in her state funeral in 2002, had represented her life as that of a black woman taken advantage of by white men. President Thabo Mbeki has said as much in his eulogy, extending his comments to a denunciation of Western science, indeed the entire Enlightenment.

We would discover, however, that Cesars was, in the racial categorization of the Cape, a “free black.” His descendants were slaves, brought forcibly to South Africa to work on the farms and in the city. Cesars’s wife also descended from slaves. The couples’ life in a poor section of Cape Town remained indelibly marked by slavery. Laws prohibited them from wearing fancy clothes. They had to apply for permission to leave the area. And they were barred from many of the economic opportunities “free burghers” enjoyed. One of the men responsible for Sara Baartman’s exploitation was, himself, subjected to prejudice.

South Africans, and indeed most of the modern world, can only see others for the color of their skin. Modern racism and its many legacies seems to have forever shaped how one speak of others, our very apprehensions of past and present. This is not how the world always was. Hendrik Cesars’s complexion was “white”, even as he was known by others in the Cape as “free black.” This is why when Cesars traveled to England Londoners saw him as a white man, a colonial settler, a mean, violent master. They could not see him for what he was, could not understand his humanity even as they criticized his actions, the decisions he made. And this is how it remains, regrettably, today.

Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully are authors of Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in June 2009.

February 17, 2015

Finding Freedom in Paris: African American Women in the Jazz Age

By T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting (Guest Contributor)

“Paris put my foot on the ground,” declared Lois Mailou Jones in a 1996 interview in the New York Amsterdam News. For Jones, Paris represented “freedom, [t]o be shackle free. . . released . . . from all of the pressure and stagnation which we suffered in this country. . . . France gave me my stability, and it gave me the assurance that I was talented and that I should have a successful career.” In Paris, she produced the famous oil on linen painting Les Fétiches (1938), now displayed at the Smithsonian. Paris was a pivotal turning point in her artistic career. She was not the first or the last black woman to express these sentiments about the City of Light.

“Paris put my foot on the ground,” declared Lois Mailou Jones in a 1996 interview in the New York Amsterdam News. For Jones, Paris represented “freedom, [t]o be shackle free. . . released . . . from all of the pressure and stagnation which we suffered in this country. . . . France gave me my stability, and it gave me the assurance that I was talented and that I should have a successful career.” In Paris, she produced the famous oil on linen painting Les Fétiches (1938), now displayed at the Smithsonian. Paris was a pivotal turning point in her artistic career. She was not the first or the last black woman to express these sentiments about the City of Light.

Between the first and second World Wars, the period some call the Jazz Age, France became a place where an African American woman could realize personal freedom and creativity, in narrative or in performance, in clay or on canvas, in life and in love. Paris, as it appeared to them, was physically beautiful, culturally refined, inexpensive as a result of the war, and seductive with its lack of violent racial animus.

The lure and lore of Paris was freedom, opportunity, and acceptance. While the weary and poor of Europe sailed to the New World towards Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, these Americans went to the Old World with its swank soirées, erudite salons and ateliers, its brasseries and cafés, and its happening jazz revues. In America, whiteness allowed the new European immigrants greater access to jobs, trade unions, and public spaces. In France, particularly in Paris, among the French and other Europeans cosmopolitans, black Americanness had a social currency that allowed access to artistic communities and creative spaces.

Though they were talented, they were also privileged as Americans and exoticized as blacks. The French fascination with American technologies and popular culture, including film, radio, and jazz introduced by African American GIs, and French Republicanism itself, embodied in the ideals of equality, liberty, and fraternity—even if imperfectly practiced—helped to further grease the wheels of social equality and freedom for African Americans in Paris. This book, Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris Between the Two World Wars, tells their stories in words and images.

T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Distinguished Professor of French and African American and Diaspora Studies at Vanderbilt University where she also directs the Program in African American and Diaspora Studies. She has published thirteen monographs and edited volumes, including the recent Bricktop’s Paris: African-American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars. She has recently completed a work of genre fiction entitled The Thirteenth Fellow, an academic murder mystery.

T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Distinguished Professor of French and African American and Diaspora Studies at Vanderbilt University where she also directs the Program in African American and Diaspora Studies. She has published thirteen monographs and edited volumes, including the recent Bricktop’s Paris: African-American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars. She has recently completed a work of genre fiction entitled The Thirteenth Fellow, an academic murder mystery.

February 16, 2015

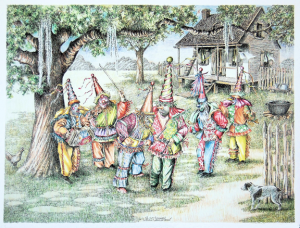

The First New Orleans Mardi Gras

By Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

In 1730 a French clerk working in Louisiana found himself in a strange situation. Marc-Antoine Caillot had come there to work for the Company of the Indies. He had embarked on his voyage in the spirit of adventure. In his memoir he would describe himself as a Don Quixote figure, a knight errant, always seeking and sometimes finding romance and pleasure even when reality was looking a bit harsh.

In 1730 a French clerk working in Louisiana found himself in a strange situation. Marc-Antoine Caillot had come there to work for the Company of the Indies. He had embarked on his voyage in the spirit of adventure. In his memoir he would describe himself as a Don Quixote figure, a knight errant, always seeking and sometimes finding romance and pleasure even when reality was looking a bit harsh.

On this occasion in February, all normal business had come to a halt as the residents of New Orleans waited to learn the latest news of an attack on the colony. The Natchez Indians had decided to fight the French who were confiscating their lands. But Caillot, in typical incongruous fashion, was determined to maintain good humor in the face of adversity. “We were already quite far along in the Carnival season without having had the least bit of fun or entertainment,” he writes. His description of what happened next stands now as the earliest description in existence of Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

In an impromptu masquerade, he and his friends dressed themselves in costume, parading through the streets and then following woodland paths until they reached a house outside the city where he knew there was a wedding celebration going on. Caillot was proud of his costume. He had crossdressed as a “French shepherdess, along with plenty of beauty marks, too, and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up.” Others in the group were disguised as Amazons, musicians, and the “Marquis de Carnival.” The party was escorted by “eight actual Negro slaves, who each carried a flambeau to light our way.”

In an impromptu masquerade, he and his friends dressed themselves in costume, parading through the streets and then following woodland paths until they reached a house outside the city where he knew there was a wedding celebration going on. Caillot was proud of his costume. He had crossdressed as a “French shepherdess, along with plenty of beauty marks, too, and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up.” Others in the group were disguised as Amazons, musicians, and the “Marquis de Carnival.” The party was escorted by “eight actual Negro slaves, who each carried a flambeau to light our way.”

When they “had gone a distance of two musket shots into the woods,” the company was terrified by four large bears who the torch-bearers managed with some difficulty to frighten off. The group continued on their way, “laughing about the little drama we had just seen, which had really given us a fright.”

Joining the wedding festivities, the party-crashers were welcomed and their costumes admired, particularly by the ladies. “I believe,” Caillot writes, “without a doubt, that the day was made for lovers.” But with the end of Mardi Gras came a return to reality. “This is how I spent those days in the land of Mississippi,” he concludes. “Now we will get back to the description of the Indian war.”

Joining the wedding festivities, the party-crashers were welcomed and their costumes admired, particularly by the ladies. “I believe,” Caillot writes, “without a doubt, that the day was made for lovers.” But with the end of Mardi Gras came a return to reality. “This is how I spent those days in the land of Mississippi,” he concludes. “Now we will get back to the description of the Indian war.”

For further reading:

Marc-Antoine Caillot, A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, edited and with an introduction by Erin M. Greenwald (Historic New Orleans Collection, 2013).

February 14, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xiv

By April Stevens (W&M Editorial Assistant)

It’s February 14th and love is in the air…or is that the spirit of President Washington frowning on our frivolous cards and candy? When Valentine’s Day and Presidents’ Day coincide on the same long weekend, one cannot help but notice the juxtaposition between cuddly cupids and an austere Lincoln.

This week’s Cabinet of Curiosities embraces this clash of sentimental and presidential to bring you some interesting historical tidbits about both.

Be Mine?

The origin of Valentine’s Day is still debated, but regardless of how it really began, lovers have been marking their love on this day since at least the 17th century. If you’re interested in the history of the classic paper “Valentine”, take a look at Ruth Webb Lee’s book A History of  Valentines.

Valentines.

For many, the conversation heart candy is a classic 20th century symbol of Valentine’s Day. Can you believe that these chatty little confections date all the way back to 1847? Erin Blakemore gives us the history of these sweet treats.

More lasting than cards and flowers, many have immortalized their love for another in song. But did you know that the history of the classic love song has a complex gender history? Ted Gioia explores the role of female innovators in the development of the love song on the OUPBlog.

For the Love of a President

Abraham Lincoln is considered one of the United States most beloved Presidents. Yet, most Americans today would probably consider the nation’s way of mourning “Father Abraham” to be a bit much. Richard Wightman Fox’s recent article shares how Lincoln’s decaying corpse was sent on a two week, five state funeral tour.

“My purest queen, no man was worthy of your love.” This message Teddy Roosevelt wrote to Alice Lee and other love notes in“Love Letters from the Oval Office” unveil the softer side of some American presidents. Who knew presidents could be such poets?

“My purest queen, no man was worthy of your love.” This message Teddy Roosevelt wrote to Alice Lee and other love notes in“Love Letters from the Oval Office” unveil the softer side of some American presidents. Who knew presidents could be such poets?

If you enjoyed these little factoids, take a look at some of other recent posts:

Unhairing in the 1800s: Animal Processing and Personal Care

Parrots with Shocking Vocabularies

Humanness in the Age of Discovery: Dog-headed Men

Don’t forget to sign up for this month’s Book Giveaways!

Like what you are reading? Subscribe to our mailing list to get updates from Wonders & Marvels in your inbox!

February 12, 2015

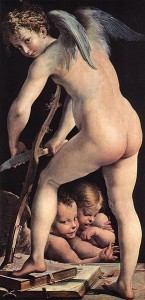

Love, Sex, and Cuddly Cupids

By Vicki Leon (Guest Contributor)

Mid-February in the U.S. brings mushy greeting cards, the overpowering scent of chocolate, and cupids. Lots of cupids.

Mid-February in the U.S. brings mushy greeting cards, the overpowering scent of chocolate, and cupids. Lots of cupids.

Call me a cynic, but I don’t buy that old saw that our Valentine celebrations arose from early Christian activists (all named Valentin) whose bloody martyrdom made this a holiday. And them into saints. (There was one female, a Saint Valentina, but her martyrdom was said to have occurred in July of the year 308.)

Having studied the matter for decades while researching the lifestyles, beliefs, and often quirky customs of long-ago Romans and Greeks, I wager that our sometimes sexy, sometimes loving holiday derives from the pagan side of the equation.

For centuries before Christianity came on the scene, the Romans celebrated a mid-February fertility festival called Lupercalia. (It continued to be honored until the 4th century A.D.) This odd ritual involved a cadre of nearly naked male runners, who roamed the city, lightly whipping every nubile female in sight with bloody strips of goathide. Sounds suspiciously like S&M, but it was a purification ritual. The floggings cleansed the city and chased off evil spirits, making Rome’s women receptive in the most basic sense for procreative sex.

The Greeks of old didn’t celebrate Lupercalia. However, they were the first to come up with a love goddess, Aphrodite, who immediately gave her name to aphrodisiacs, among other things. Her son–we’re still unclear about the father–was Eros, from which comes “erotic.” The Romans enthusiastically adopted both of them early on, calling her “Venus” and her son, “Cupid.”

There was a Greco-Roman obsession with deities. They thought nothing of adding to the already-massive roll-call of gods and goddesses. Thus, at one point, they decided that the love goddess and her sidekick needed help. In nine out of ten myths, she had little maternal control over her son Eros/Cupid, who as everyone knew, was in charge of sexual passion, the juvenile delinquent of the family. (Frightening, the way that kid armed himself with state-of-the-art weaponry.)

Given her deplorable parenting skills, Venus could not keep up with the demands on her time. All those anguished parents, star-crossed lovers, horny teens, forlorn widows, and brides forsaken at the altar needed more divine help. They looked to her for solace. For answers, darn it.

What was the ingenious solution that Greeks (and the copycat Romans) came up with? They took a long hard look at love, lust, and longings, then subdivided those emotions into categories. Once identified, they created a lineup of subordinate demi-gods to handle those calls, so to speak. The concept resembled our smartPhones and answering machines, with their “Press 1, Press 2,” menu choices.

The minor deities that the folks of long ago dreamed up were cuddlesome little rascals. Like Eros/Cupid, they were depicted as young boys or even toddlers. They had rosy, infantile bodies with wings. They ran about nude, playfully shooting arrows and getting into adorable mischief. As a group, they were called the Erotes–the little loves. In art, they often served as the entourage to Eros/Cupid.

Since the Greeks recognized both unrequited love and requited love, they created Himeros and Anteros to report to for people with those afflictions. Or blessings. Popular among the morbidly depressed, love-gone-wrong population was a godlet named Pothos, who commiserated over sexual yearnings. For lovers new to the game, a pair of Erotes called Peitho and Hedylogos handled issues like seduction, sweet-talk, pickup lines, and similar matters.

Taken as a whole, the Erotes provided emotional help and an on-call support group to the general populace.

In addition, the Erotes caused legions of painters, sculptors, and muralists all over ancient Italy, Greece, and the rest of the Roman Empire to breathe a huge sigh of relief. At last! Some fresh new material to work with, a variety of cuddly, fleshy cupids to brighten otherwise humdrum murals, friezes, wine goblets, chamberpots, and more.

Vicki Leon is a nonfiction author of 37 books, includes this tale and 88 others in her newest book, The Joy of Sexus. (Walker, January 2013).

Vicki Leon is a nonfiction author of 37 books, includes this tale and 88 others in her newest book, The Joy of Sexus. (Walker, January 2013).

February 11, 2015

Humanness in the Age of Discovery: Dog-Headed Men

By Lynn Ramey (Guest Contributor)

From early on, travelers reported seeing “races” of men that were later referred to as the “monstrous races,” one of the most unusual being men who looked normal except for having a dog’s head. In Natural History, Pliny the Elder (d. 79) catalogues forty-odd peoples with attributes from cannibalism to excessive hairiness, from those sporting a dog’s head (cynocephali) to those with no discernable head, just eyes and a mouth in their chests. For Pliny, these were simply marvelous peoples, but remained part of humankind.

In the early medieval era, Augustine (d. 386) raises the problem in the City of God using Pliny’s catalog of the monstrous races, but he adds the Christian concern: how do the monstrous races fit into God’s plans for mankind? Later, Bartholomew the Englishman (d. 1272) (who as far as we know never actually travelled) notes several types of monstrous men, including cave-dwelling troglodytes, cynocephali, and the headless blemmye, with eyes in their chests. Tellingly, Bartholomew includes the monstrous men twice in his encyclopedia, once under the categories of men and again under the rubric of animals, as if he is no longer sure of their humanness. Odoric of Pordenone, an Italian Franciscan monk travelled between 1317 and 1330 for the purpose of converting those he encountered. At the island of Nicoveran, he reports on people who are dog-faced, the cynocephali. He notes that they worship oxen and wear a gold or silver ox on their forehead in honor of their god. Odoric clearly considers these to be people capable of religious belief, albeit odd, but he finds other marvelous races that he deems to be inhuman.

In the early medieval era, Augustine (d. 386) raises the problem in the City of God using Pliny’s catalog of the monstrous races, but he adds the Christian concern: how do the monstrous races fit into God’s plans for mankind? Later, Bartholomew the Englishman (d. 1272) (who as far as we know never actually travelled) notes several types of monstrous men, including cave-dwelling troglodytes, cynocephali, and the headless blemmye, with eyes in their chests. Tellingly, Bartholomew includes the monstrous men twice in his encyclopedia, once under the categories of men and again under the rubric of animals, as if he is no longer sure of their humanness. Odoric of Pordenone, an Italian Franciscan monk travelled between 1317 and 1330 for the purpose of converting those he encountered. At the island of Nicoveran, he reports on people who are dog-faced, the cynocephali. He notes that they worship oxen and wear a gold or silver ox on their forehead in honor of their god. Odoric clearly considers these to be people capable of religious belief, albeit odd, but he finds other marvelous races that he deems to be inhuman.

As explorers travelled to the New World, they took their questions about humanness with them. In the first example of an explicitly New World map (1513), the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis shows dog-headed people and blemmye in South America. Like the dog-headed people in Odoric’s medieval account, these dog-men appear to possess some degree of culture, often linked to the ability to reason, as they dance in the margins of the map. However, writing on the map specifically states that the indigenous peoples of South America are animals, with no culture or reason.

Sadly, by the 16th century the monstrous races are no longer cute and marvelous, but they have become linked with real peoples. Having judged these races and peoples to be without reason, the stage has been set for exploitation of New World resources and its inhabitants.

Lynn Ramey is Associate Professor of French at Vanderbilt University. Her research centers on contact between pre-modern cultures via trade, travel, or conquest. Her newest book Black Legacies: Race and the European Middle Ages explores how attitudes and practices in Europe’s Middle Ages contributed to the western concept of race.

Lynn Ramey is Associate Professor of French at Vanderbilt University. Her research centers on contact between pre-modern cultures via trade, travel, or conquest. Her newest book Black Legacies: Race and the European Middle Ages explores how attitudes and practices in Europe’s Middle Ages contributed to the western concept of race.

February 9, 2015

Bed, Bread and Dead: The Dummies’ Guide to Herodotus

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

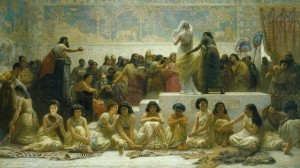

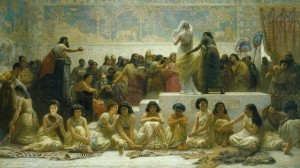

The Babylonian Marriage Market: 1875 painting by the British painter Edwin Long

Herodotus has to be my favorite ancient historian. Hailed as both ‘father of history’ and ‘father of lies’, he wrote a history of the time of the Persian Wars that was everything the later Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian Wars was not: racy, dodgy and fond of tangents. It’s from Herodotus that many of the best stories of ancient Greece come. For example, in Book 6.127-129 he tells the tale of Hippocleides, who was doing pretty well in the contest to win the hand of the daughter of Cleisthenes until he drank rather more than he could handle and danced on a table, ending by standing on his head and beating time with his legs. Cleisthenes told him he’d blown his chances and Hippocleides replied ‘It’s all the same to Hippocleides!’

When I used to teach Herodotus to first-year students at university, I developed a simple way of remembering the basic points about how he categorizes different peoples: bed, bread and dead. That’s to say, when describing anyone, whether that’s the Egyptians or the Amazons, the main things that grip him are what they do sexually, what they eat and how they deal with their dead.

Different ways of handling marriage fascinate him. He tells us that the Babylonians run an annual marriage market in which the unmarried women of each village are graded by their looks and auctioned off, starting with the most beautiful. When these are all sold, the less attractive are given a dowry from the proceeds of the sale, so that all end up married.

He frequently goes into the details of burial customs. The Thracians lay out the bodies of the dead for three days. At the funeral of a king, the Scythians kill one of his concubines and various other personal attendants, then get high on hemp, before killing more servants – and horses – a year later.

He is particularly interested in those who mix up the categories of bed, bread and dead – for example, the Egyptian mummifiers who like to have sex with the corpses of attractive women before mummifying them, or the Issedones who eat their dead fathers, mixing up the flesh with some lamb, and then gild their skulls.

It’s still debated whether stories like this contain any truth, but they were clearly very appealing to Herodotus and to his audience. So why were these the big three areas of interest? The ancient Greeks had very clear ideas about what was ‘normal’ and ‘right’ in each of them. Marriage should be between one man and one woman, arranged by their families. The Amazons come out as pretty weird here, because in various ancient versions of their customs, they either have an annual sex binge with the men of a neighbouring tribe, or they have tame men who are lamed to stop them running away. And in Herodotus they need to kill three men in battle before they are allowed to marry.

Food should consist of what is cooked, not what is raw, and a key aspect of this was the staple product of bread. The dead should be treated with appropriate respect and placed in the earth; think here of the play Antigone in which the disrespectful treatment of the body of the heroine’s brother is at the heart of the drama. Those who had contact with a corpse were polluted. There were rules on how a corpse should be prepared for burial, on where people could be buried, and on how long the period of mourning should last. Eating people was wrong – but so was a completely vegetarian diet.

Bed, bread and dead: so important in ancient Greek anthropology, precisely because they were the areas of human life by which the Greeks defined themselves.

Bed, bread and dead – the dummies’ guide to Herodotus

by Helen King

The Babylonian Marriage Market: 1875 painting by the British painter Edwin Long

Herodotus has to be my favorite ancient historian. Hailed as both ‘father of history’ and ‘father of lies’, he wrote a history of the time of the Persian Wars that was everything the later Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian Wars was not: racy, dodgy and fond of tangents. It’s from Herodotus that many of the best stories of ancient Greece come. For example, in Book 6.127-129 he tells the tale of Hippocleides, who was doing pretty well in the contest to win the hand of the daughter of Cleisthenes until he drank rather more than he could handle and danced on a table, ending by standing on his head and beating time with his legs. Cleisthenes told him he’d blown his chances and Hippocleides replied ‘It’s all the same to Hippocleides!’

When I used to teach Herodotus to first-year students at university, I developed a simple way of remembering the basic points about how he categorizes different peoples: bed, bread and dead. That’s to say, when describing anyone, whether that’s the Egyptians or the Amazons, the main things that grip him are what they do sexually, what they eat and how they deal with their dead.

Different ways of handling marriage fascinate him. He tells us that the Babylonians run an annual marriage market in which the unmarried women of each village are graded by their looks and auctioned off, starting with the most beautiful. When these are all sold, the less attractive are given a dowry from the proceeds of the sale, so that all end up married.

He frequently goes into the details of burial customs. The Thracians lay out the bodies of the dead for three days. At the funeral of a king, the Scythians kill one of his concubines and various other personal attendants, then get high on hemp, before killing more servants – and horses – a year later.

He is particularly interested in those who mix up the categories of bed, bread and dead – for example, the Egyptian mummifiers who like to have sex with the corpses of attractive women before mummifying them, or the Issedones who eat their dead fathers, mixing up the flesh with some lamb, and then gild their skulls.

It’s still debated whether stories like this contain any truth, but they were clearly very appealing to Herodotus and to his audience. So why were these the big three areas of interest? The ancient Greeks had very clear ideas about what was ‘normal’ and ‘right’ in each of them. Marriage should be between one man and one woman, arranged by their families. The Amazons come out as pretty weird here, because in various ancient versions of their customs, they either have an annual sex binge with the men of a neighbouring tribe, or they have tame men who are lamed to stop them running away. And in Herodotus they need to kill three men in battle before they are allowed to marry.

Food should consist of what is cooked, not what is raw, and a key aspect of this was the staple product of bread. The dead should be treated with appropriate respect and placed in the earth; think here of the play Antigone in which the disrespectful treatment of the body of the heroine’s brother is at the heart of the drama. Those who had contact with a corpse were polluted. There were rules on how a corpse should be prepared for burial, on where people could be buried, and on how long the period of mourning should last. Eating people was wrong – but so was a completely vegetarian diet.

Bed, bread and dead: so important in ancient Greek anthropology, precisely because they were the areas of human life by which the Greeks defined themselves.