Holly Tucker's Blog, page 22

November 4, 2015

A Husband or a Hat?

By Susan Hiner, Guest Contributor

Mon Dieu! Still single at 25?!

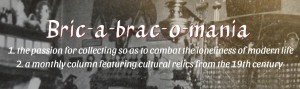

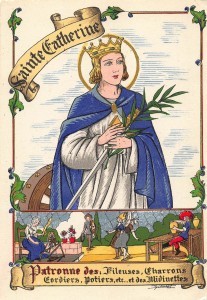

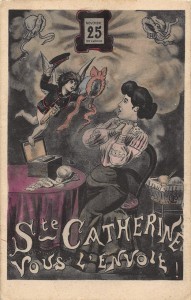

If you were a young woman living in France at the turn of the twentieth century, on November 25th you might have received a number of friendly, encouraging messages by postcard—ranging from the anodyne “Bonne fête” to the more explicitly instructive, “Pray to Saint Catherine, and your wish will be granted” to the downright officious, “pay attention to what this handsome fellow says,” which we find on the verso of this card, admonishing the recipient to take heed of its printed message. Don’t take the hat, the joli garçon apparently utters, take me instead! The gentleman offers his mustachioed self in lieu of the bonnet: a husband instead of a hat.

Don’t take the hat, the joli garçon apparently utters, take me instead! The gentleman offers his mustachioed self in lieu of the bonnet: a husband instead of a hat.

When I first began collecting catherinettes cards, little did I know that this frothy bonnet emblematized a cultural normalizing of female behavior. Or that those cards might eventually challenge that narrative. Indeed, in the first few decades of the twentieth century, young fashion workers would marshal the elements of the ritual into their own celebration of working women.

When girls reached the marriageable age of fifteen, they put order to their unruly girlish hair, donned the bonnet, and could then “coiffer Sainte Catherine,” meaning both wear the bonnet that signified their coming of age and create a bonnet to ornament the saint herself. They put their sewing skills to work and hoped to attract a husband as well. While the origins of this tradition are to be found in religion and folklore, the mass appeal of postcards at the turn of the twentieth century and beyond was tied to technological advances in photography and printing and modernized mail systems. The folklore festival of Saint Catherine originally designated a rite of passage.

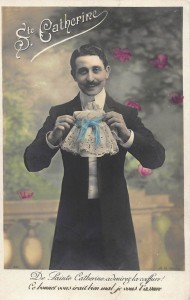

Saint Catherine was the patron saint of unwed girls, but also of old maids, their agin g corollaries. The endgame of Catherine and the bonnet ritual was thus either marriage or spinsterhood. Saint Catherine of Alexandria, who refused to marry the Roman emperor Maxentius, was condemned to death by the wheel. The (Catherine) wheel miraculously broke apart, and she was not harmed. She was, however, subsequently beheaded and thus martyred. The wheel is pictured in much of the iconography of the saint, which may account for her association with fashion workers.

g corollaries. The endgame of Catherine and the bonnet ritual was thus either marriage or spinsterhood. Saint Catherine of Alexandria, who refused to marry the Roman emperor Maxentius, was condemned to death by the wheel. The (Catherine) wheel miraculously broke apart, and she was not harmed. She was, however, subsequently beheaded and thus martyred. The wheel is pictured in much of the iconography of the saint, which may account for her association with fashion workers.

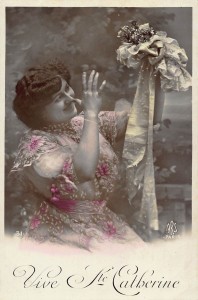

“Coiffing” Saint Catherine thus signified that a girl was eligible, but if she coiffed for too many years without bagging a husband, she was marginalized and doomed to spinsterhood. Woe unto the girl who has no such suitor as our mustachioed friend, for she was condemned to wear the bonnet and wait, as the weeping girl surrounded by her symbolic finery in this card suggests. Her tearful gesture conveys a distressing message of failure and impending solitude, for, as she ages, her chances of married bliss recede. After the age of twenty-five, celibacy would overtake eligibility, and girls could no longer don the coiffe.

The image of the bonnet was reproduced and circulated on a mass scale, demonstrating how the imperative to marry was  transmitted and reinforced at a time when more and more women were entering the workforce and questioning traditional roles.

transmitted and reinforced at a time when more and more women were entering the workforce and questioning traditional roles.

Beneath their quaint photos with their stylized poses featuring industrious, expectant girls and smiling, smarmy gentlemen, pithy rhymes, solemn prayers, and wedding day fantasies, these  catherinettes cards screen a kind of social coercion into a rigid ideology that imposed marriage as the only acceptable pathway for young women to follow.

catherinettes cards screen a kind of social coercion into a rigid ideology that imposed marriage as the only acceptable pathway for young women to follow.

The bonnet even appeared to menace the girl on many cards as if threatening those girls who were not prioritizing marriage.

Sent by Saint Catherine herself, this card says, the diminutive messenger seems to take her quite by surprise, and brings with him an impending threat.

Sent by Saint Catherine herself, this card says, the diminutive messenger seems to take her quite by surprise, and brings with him an impending threat.

So hateful was the bonnet that some cards picture girls casting it off with unseemly gestures, perhaps to indicate that they no longer need Saint Catherine’s protection, having found a husband, or perhaps to indicate that they are throwing off the tradition and what it represents entirely.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, after droves of provincial girls had left for Paris to enter the needle trades, Parisian fashion workers appropriated the November holiday as a celebration of women’s work in the millinery. The crafting of the hat itself became celebratory and the unwed status of the fashion worker a mark of pride when she wore a hat of her own creation.

A hat instead of a husband.

Susan Hiner is Professor of French at Vassar College. The author of Accessories to Modernity: Fashion and the Feminine in 19th-C France (Penn Press, 2010), she is currently working on a new book entitled “Behind the Seams: Fashion, Women, and Work in 19th-Century France.”

For more on the history of this folklore tradition, see Yvonne Verdier, Façons de dire, façons de faire: la laveuse, la couturière, la cuisinière (Paris: Gallimard, 1979). The authority on the subject of the catherinettes is Anne Monjaret. See La Sainte-Catherine: Culture festive dans l’entreprise, preface by Martine Segalen (Paris: Editions du C.T.H.S., 1997).

November 2, 2015

An Ancient Method of Taming a Wild Horse

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

According to the ancient Greeks, nomadic Scythians and Amazons beyond the Black Sea were the first to tame wild horses. Recently translated oral traditions of tribes of the northern Caucasus affirm that ancestral superheroes called “Narts” were the first to ride wild horses. (Nart sagas combine ancient Indo-European mythology with Eurasian folklore.) Notably, modern scientific, historical, and archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest domestication of the horse occurred on the Eurasian steppes in about 3,500 BC.

A Nart saga from Abkhazia (NW Caucasus) credits a folk hero, Sasruquo, with the discovery of a unique method of taming a headstrong horse. In the tale, Sasruquo needs to travel quickly to an important assembly of many tribes. This was in the time when only the Narts knew the secrets of domesticating wild horses. But after his beloved horse Bzow died, Sasruquo had vowed to “sit astride no other steed.”

He sets off on foot but must cross a furiously churning river. He notices a wild stallion grazing on the bank. Sasruquo makes reins and a bit of mulberry bark, thrusts it into the horse’s mouth, and leaps onto the stallion’s back as it plunges into the river. As the horse thrashes and wears itself out against the raging torrent, Sasruquo patiently urges and guides the stallion to safety on the other bank. The horse, now docile, trusts Sasruquo and follows the direction of the reins.

At the assembly of tribes, people are astonished to see someone riding horse and they asked how the feat was accomplished. “From that day onward,” many nomads on the steppes began to tame and ride wild steeds.

This resourceful ancient technique of teaching horses to accept riders is still used by horse-people in the Caucasus and the steppes–and in other places around the world. Some mount horses in streams or rivers; others start riding young or wild horses in deep snow banks. In the Altai region and Mongolia, they train young and/or wild horses by riding them in deep mud or over hillsides. Native Americans and ranchers in the US have used these methods, too. All the versions have the same effect of impeding and tiring the horse. The method should be not be overdone, and the river technique works best if one uses herd instinct, allowing a young or green horse to observe and follow other horses into water, before introducing a rider.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a research scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Her most recent book is The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (Princeton UP 2014)

Acknowledgments: See Saga 81 in John Colarusso’s Nart Sagas of the Caucasus (coming out in paperback 2016). Thanks to knowledge shared by Min Andersen, Lisa Badger, Roberta Beene, Deborah Farvoyager, Scott German, Nolan Gillies, Julie Kinney, Patricia Marinelli-Siutz, Diana Olds, Katie Stearns, Linda Svendsen, and other members of the Amazons Ancient and Modern group on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/groups/ancie...

October 29, 2015

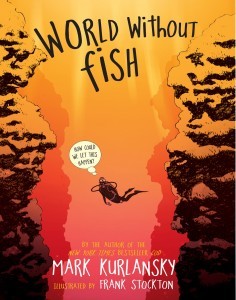

A World Without Fish

By Mark Kurlansky (Guest Contributor)

It was in the North Sea in the late nineteenth century that innovations in fishing began to take place. The North Sea is a body of water rich in fish, which is surrounded by the great European fishing nations, such as Scotland, England, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and Norway. Throughout history, these nations competed with one another for fish and fishing territories. Some of these countries had even gone to war over it: Holland and England battled over North Sea herring during the Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century; France and England fought over North American cod in the early eighteenth century during the Queen Anne’s War.

It was in the North Sea in the late nineteenth century that innovations in fishing began to take place. The North Sea is a body of water rich in fish, which is surrounded by the great European fishing nations, such as Scotland, England, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and Norway. Throughout history, these nations competed with one another for fish and fishing territories. Some of these countries had even gone to war over it: Holland and England battled over North Sea herring during the Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century; France and England fought over North American cod in the early eighteenth century during the Queen Anne’s War.

For centuries, North Sea nations kept bringing in larger and larger catches, with little sign of any decline in the supply of fish. In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch had two thousand ships in the North Sea fishing for herring. The British responded by banning foreign fishing vessels within fourteen miles of the British coastline (this was the distance visible from the top of a mast).

It was the British that first started using a beam trawler in the fourteenth century. Also called a “wondrychoum,” this was a net suspended from a beam and dragged through the sea. The problem with beam trawlers was that sailing ships didn’t have the power to haul huge nets – if the nets were too large and caught too many fish, they would be too heavy to pull so they had to use small ones.

On the other hand, beam trawlers were quite efficient in other ways. The potential of dragging a net through the water and hauling up everything in its path had obvious advantages over setting lines with baited hooks. In addition to requiring no bait, a beam trawler seemed certain to haul in a much higher percentage of the fish it passed. By 1774, beam trawling had become one of the principal fishing techniques in the North Sea.

In the mid-nineteenth century, new ideas were aimed at improving the quality of fish, and of getting the fish to market fresher. Well boats came into use. These were ships that contained a tank of seawater into which the caught fish would be dumped, enabling fish to stay fresh longer than previously. This meant that fishermen could remain at sea, fishing for a longer period of time. Once the quality of fish improved in England, and most notably in London, the demand for fish rapidly increased.

Then in 1848, a new dramatic technological advance was created in the port of Grimsby on the North Sea at the mouth of the Humber River: a rail connection straight to London. Because it was a large port, capable of storing ice from not-too-distant Norway, (ice was essential for keeping fish fresh on its way to market), the port of Grimsby became a premier port for quality fish in London. In 1881, the Zodiac, the first vessel built for dragging fishing nets under steam power, was launched from Grimsby.

Mark Kurlansky is a former commercial fisherman and New York Times bestselling author of Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World, Salt: A World History, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, and 16 other books. He’s won numerous awards, including the James A. Beard Award, Glenfiddich Award for food writing, ALA Notable Book Award, The New York Public Library Best Books of the Year Award, Los Angeles Times Science Writing Award, Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He has illustrated many of his books himself. Kurlansky lives with his wife and daughter in New York City and Gloucester, Massachusetts. His website is www.markkurlansky.com.

Mark Kurlansky is a former commercial fisherman and New York Times bestselling author of Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World, Salt: A World History, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, and 16 other books. He’s won numerous awards, including the James A. Beard Award, Glenfiddich Award for food writing, ALA Notable Book Award, The New York Public Library Best Books of the Year Award, Los Angeles Times Science Writing Award, Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He has illustrated many of his books himself. Kurlansky lives with his wife and daughter in New York City and Gloucester, Massachusetts. His website is www.markkurlansky.com.

Illustrations by Frank Stockton

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in June 2011.

October 26, 2015

“Opening” Japan–The Meiji Restoration

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

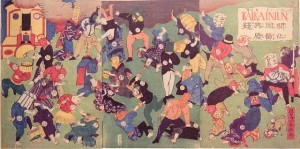

The New Fighting the Old in Early Meiji Japan

In 1853 the United States government forced Japan to open its ports to United States merchants in a literal display of gunboat diplomacy. Commodore Perry’s act of military aggression against Japan is often given credit for dragging Japan into the nineteenth century. In fact, the real credit for Japan’s transformation belongs to the generation of Japanese elites who orchestrated the political and cultural revolution known as the Meiji Restoration.

Under the leadership of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan had chosen to shut itself off from Western influence in the early seventeenth century. By the mid-eighteenth century, Japanese suspicion of all things Western had begun to fray around the edges, at least among the intellectual elite. A handful of Japanese scholars shifted their focus from Chinese culture to so-called “Dutch learning”.*

In the early nineteenth century, motivated by domestic problems and the threat embodied in Perry’s “black ships of evil mien”, reform-minded daimyo** began to mutter against the power of the shogunate, agitate for a restoration of imperial power, and call for the adoption of western learning and technology, particularly Western military technology. (We are, after all, talking about members of the samurai class, who were defined by their role as warriors.) In the years after Perry “opened” Japan,*** muttering turned to civil war.

In January, 1868, after two years of war, reformist (or perhaps more accurately, anti-Shogun) troops occupied Edo Castle, abolished the shogunate and proclaimed the “restoration” of the fifteen year old emperor, known by the reign name of Meiji. The Meiji Restoration, which lasted until 1912, was a period of self-conscious modernization and westernization–a focused leap across more than 200 years of technical innovation and social revolution in a period of forty some years. Members of the Japanese elite were sent to Europe and the United States to learn about Western government, western industry, and western culture. The reforms that followed transformed the government, the economy, land ownership, education, and the military. Much of Japan’s traditional life style was swept away, leaving in its place a new enthusiasm for western ideas on the part of urban intellectuals, a newly reconstructed vernacular literary language, and a new philosophy of individualism.

The abolition of the samurai as a warrior class was perhaps not the most important of the changes in practical terms but it was the clearest symbol of the decision to move from the medieval to the modern world.The samurai class was officially abolished in a series of measures that began in 1871, when all samurais were required to cut off their topknots, and ended with the Haittorei Edict of March 1876, which took away the samurais’ right to carry swords.

Many samurai found new ways to serve Japan in the reformed government. Others found themselves with neither purpose nor livelihood. The last gasp of the samurai came in 1877. Saigo Takamori, sometimes known as the Last Samurai led a hopeless rebellion against the Japanese government. Six hundred samurai, armed with the traditional sword and bow, fought the government’s newly trained modern army in an effort to reverse the westernizing changes that threatened their entire way of life. Many of the rebels believed it was better to die using the traditional weapons of the samurai than to live using modern ones–not surprisingly, they did.

With the samurai no longer a force, Japan built the modern army that would be a force to be reckoned with in the twentieth century.

*During the medieval period, Europeans in the Middle East were collectively known as Franks, after the Germanic tribes that ruled much of Europe. Similarly, “Dutch” was shorthand for all things Western in Japan because the only foreigners allowed to have direct contact with Japan were merchants from the Dutch East India Company (VOC). (You couldn’t describe Dutch interaction with Japan as close–the merchants were confined to the closely guarded island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor and VOC ships were allowed to dock once a year. The Iron Curtain looked like it was made from fishing net by comparison.)

**The feudal lords of shogunate Japan

October 25, 2015

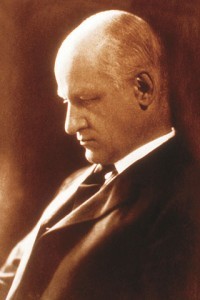

Museum Mysteries: Dr. Cabot’s Cabinet of Curiosities

By Sarah Alger

During the past 200 years, Massachusetts General Hospital has seen buildings rise, come down, and others rise in their place, and has grown to more than 20,000 employees, some of whom spend decades here. As a result (and to the chagrin of our Special Collections department), historical objects might get shifted around before disappearing down some long hallway into someone’s office, to be unearthed years later as the office’s occupant cleans out, prompted by a move or retirement. Then—we hope—we get calls about those objects.

Ooooh…

The most recent emergence from the MGH woodwork: a beautifully crafted wooden, glass-fronted cabinet with a brass plaque that reads “Richard C. Cabot Collection.”

Even among the giants who populate MGH history, Richard Cabot stands particularly tall. Born in 1868 into a prominent Bostonian family (they who, as the famous rhyme went, “speak only to God”), he graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1892. He began his career in hematology, working from his own medical practice, and was invited to join MGH staff in 1898.

There he embarked on one of his most memorable contributions: the clinicopathological conference, in which a physician, before a crowd of colleagues, would be given the details of a difficult case and would figure out the diagnosis aloud. In 1911, Cabot would publish Differential Diagnosis, a compilation of several hundred case studies, in which he outlined the need for such a book: “Why do so many physicians treat symptoms only? Why are their diagnoses and the resulting treatment so full of vagueness, groping, hedging, and ‘shot-gun’ prescriptions? Because they do not know how to get beyond symptoms.” These case study examinations live on in the New England Journal of Medicine as the Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

There he embarked on one of his most memorable contributions: the clinicopathological conference, in which a physician, before a crowd of colleagues, would be given the details of a difficult case and would figure out the diagnosis aloud. In 1911, Cabot would publish Differential Diagnosis, a compilation of several hundred case studies, in which he outlined the need for such a book: “Why do so many physicians treat symptoms only? Why are their diagnoses and the resulting treatment so full of vagueness, groping, hedging, and ‘shot-gun’ prescriptions? Because they do not know how to get beyond symptoms.” These case study examinations live on in the New England Journal of Medicine as the Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Cabot’s other major contribution was to establish, in 1905, the first social service of an American hospital. The following year Cabot hired social worker Ida Cannon to organize the new department. Said Cannon: “He was presenting the idea of social service within the hospital where sick patients, although separated from their home and families, nevertheless cannot separate themselves from their personal problems.”

…Oh.

So, the contents of Cabot’s cabinet: none, unfortunately. Our own archives do not contain an inventory, and each time I look at the piece, it offers me a silent taunt for not having yet contacted Cabot’s previous biographers or delved into the more than 200 cartons of his papers at the Countway Library of Medicine.

In these cartons is a file entitled “Words Symptomatic of Our Current Thoughtlessness.” I have no doubt that such a mind would have compiled a fascinating cabinet.

October 23, 2015

The Art of Understanding Your Son-in-Law (and Maybe Yourself?)

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

Katharine Briggs, left, and daughter Isabel Myers,

The scenario is not unfamiliar: beloved daughter leaves for college and returns for Christmas vacation with less than loveable boyfriend. Sure enough, they soon announce their engagement. What is a mother to do?

Katharine Briggs and Isabel Myers

When Katharine Briggs’ only daughter Isabel brought home Clarence Myers from Swarthmore College in the late 1910s, Briggs responded with remarkable empathy and characteristic bookishness: she created a theory of personality types to help her understand why her future son-in-law was so “different”.

Briggs was born in 1875 and although she was educated in a progressive home and attended agricultural college, cultural expectations prevented her from pursuing her interest in psychology professionally, and she instead became a passionate amateur, practicing her theories of educational psychology and childrearing on her one surviving child, Isabel. Whatever motivated Isabel’s tendentious choice of husband, her mother’s response to him led to an early vision of personality types that –inspired by Karl Jung’s model—became the basis for the now ubiquitous Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.

Mostly Bunk, but sTill In vogue

It seems that Isabel Myers was not initially as enthused by her mother’s project, but once her own children were older, she began to build on Briggs studies, motivated especially by a desire to contribute to the war effort. In 1942, Myers began working for Edward M. Hay, the personnel manager of a Philadelphia bank, in order to learn to use existing career allocation tests. She was frustrated by their inefficacy, however, and began to design paper tests herself, based on her mother’s research on “type”. She continued to work on refining the questions and taking opportunities to test people, making the most of her father’s contacts in the academic world and Hay’s in the business world to secure access to ever-larger groups of test subjects. In 1962, the MBTI was published by Education Testing Service (ETS), for research use. In 1975, Myers contracted with Consulting Psychologists Press Inc. (CPP), who marketed the “indicator” for general use as a personality and career guide, launching the phenomenon we know today.

It seems that Isabel Myers was not initially as enthused by her mother’s project, but once her own children were older, she began to build on Briggs studies, motivated especially by a desire to contribute to the war effort. In 1942, Myers began working for Edward M. Hay, the personnel manager of a Philadelphia bank, in order to learn to use existing career allocation tests. She was frustrated by their inefficacy, however, and began to design paper tests herself, based on her mother’s research on “type”. She continued to work on refining the questions and taking opportunities to test people, making the most of her father’s contacts in the academic world and Hay’s in the business world to secure access to ever-larger groups of test subjects. In 1962, the MBTI was published by Education Testing Service (ETS), for research use. In 1975, Myers contracted with Consulting Psychologists Press Inc. (CPP), who marketed the “indicator” for general use as a personality and career guide, launching the phenomenon we know today.

As this brief sketch of its origins betrays, the MBTI is not based on orthodox scientific experiment, but rather on intuition and observation. It is now broadly dismissed in scientific circles. This skepticism notwithstanding, the MBTI remains tenaciously popular, especially in business and consulting settings, where some use their four-letter code as an introductory icebreaker (“Hi! I’m Clarence. ISTJ”). Cynics explain its popularity as a corollary of its flattery: by design, it describes a personality the test-taker wants to see reflected back, with the added legitimacy of a recognized trademark. A more charitable explanation is that it does serve as a useful shorthand for working styles (moods?) on first meeting (simpler than “Hi! I’m Juliet. Hung-over, impatient, cranky, cantankerous and underpaid” – HICCUP?).

Alas, there is still no scientifically approved method to understand difficult son-in-laws.

—-

There are many articles (and one book) on the history of Katherine Briggs, Isabel Myers and the MBTI, but by far the best read –and the most informative—is Merve Emre’s recent article:

October 22, 2015

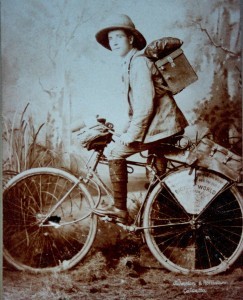

Velocipede: The History of the Bicycle

By David Herlihy (Guest Contributor)

The basic bicycle, or “velocipede,” debuted in Paris during the Universal  Exhibition of 1867. “A Revolution in Locomotion,” effused the New York Times correspondent, adding that the slender vehicle could fly through the air at speeds approaching twelve miles an hour. An industry quickly sprung up in Paris with its own organ, Le Vélocipède Illustré.

Exhibition of 1867. “A Revolution in Locomotion,” effused the New York Times correspondent, adding that the slender vehicle could fly through the air at speeds approaching twelve miles an hour. An industry quickly sprung up in Paris with its own organ, Le Vélocipède Illustré.

Despite its crude construction, consisting of an 80-pound solid iron frame mounted on wooden carriage wheels with no tires, hopes ran high that the bicycle would soon serve as the “poor man’s horse.” Le Vélocipède Illustré. ran a serial entitled “Around the world on a Velocipede,” starring a fictitious American tourist named Jonathan Schopp.

Of course, not everyone shared such a rosy prognosis. Even the highly imaginative Jules Verne seems to have discounted the far-fetched notion that the bicycle would ever prove practical. In his equally fictitious Around the World in Eighty Days (first published in 1873), the protagonist Phileas Fogg makes use of numerous state-of-the-art vehicles and vessels, but pointedly no velocipedes.

Still, time would eventually vindicate the original champions of cycling. In the 1870s, the vehicle gradually evolved into an impressive road-worthy vehicle, shedding half its weight thanks to numerous improvements such as steel tubing and smooth ball bearings, while assuming the daunting but effective profile connoted by “penny farthing.”

At last, in 1884, a young English-born American named Thomas Stevens set off from San Francisco, mounted on a Columbia high wheeler. Three years later he would make his triumphant return, having covered almost 15,000 miles overland while cycling in three continents. He would be the inspiration for Frank Lenz, who set off nearly a decade later on a new-fangled “safety” bicycle (the modern prototype) determined to become the most famous and remarkable of all the “globe girdlers.” In a sense, he would succeed.

David V. Herlihy is the author of The Lost Cyclist (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and Bicycle: The History (Yale University Press), winner of the 2004 Award for Excellence in the History of Science. A recognized authority in his field, he is responsible for the naming of a bicycle path in Boston after Pierre Lallement, the original bicycle patentee, and for the installation of a plaque by the New Haven green where the Frenchman introduced Americans to the art of cycling in 1866.

David V. Herlihy is the author of The Lost Cyclist (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and Bicycle: The History (Yale University Press), winner of the 2004 Award for Excellence in the History of Science. A recognized authority in his field, he is responsible for the naming of a bicycle path in Boston after Pierre Lallement, the original bicycle patentee, and for the installation of a plaque by the New Haven green where the Frenchman introduced Americans to the art of cycling in 1866.

This post was originally published on Wonders & Marvels in August 2010.

October 20, 2015

Dr. Keeley’s Gold Rush

By Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Although we’re crazy for adorning ourselves with gold, humans have invoked a variety of health reasons to take the precious metal inside our bodies, as well. Gold components often go into such implanted devices as heart pacemakers, not to mention dental work. A liquid suspension called colloidal gold may have uses in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and in the delivery of tiny amounts of medications.

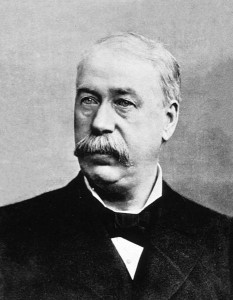

Leslie M. Keeley

Of all the benefits ascribed to the medical exploitation of gold, perhaps the strangest belonged to Leslie M. Keeley, a nineteenth-century physician who convinced countless desperate people that gold could cure them of drinking and doping.

Keeley, who had doctored Civil War troops as a member of the Union Army medical corps, in 1880 first combined the special ingredients of his “Bichloride of Gold” nostrum and declared it a cure for chemical addictions. Over the next 11 years, he developed a marketing scheme for the compound and opened the first Keeley Institute in Dwight, Illinois, in 1891. By 1900, the year of Keeley’s death, there were Keeley Institutes in every state. Keeley hit upon his “cure” at an opportune time when other treatment choices for alcohol and drug addicts offered little genuine chance for recovery.

Keeley’s cure thrived for a time because it offered the credibility of a pseudoscientific explanation for addiction. He declared that alcoholism resulted from damage to nerve cells that weakened the victim’s will power. Patients could lose their craving for alcohol and drugs only if they underwent treatment to purge their cells of poisons and restore them to proper functioning. Teamed with rest, exercise, and healthy food, draughts and injections of Keeley’s claimed “gold cure” could eliminate the addiction. Over the years, an estimated 400,000 people underwent the gold treatment at one of the scores of Keeley Institutes scattered around the U.S. Keeley’s staff claimed a cure rate of 95 percent.

Unfortunately, there was no such thing as “Bichloride of Gold.” A 1907 lawsuit exposed the actual ingredients of the Gold Cure compound: strychnine, atropine (the drug ophthalmologists use to dilate pupils), boric acid, and water — and no gold, in “bichloride” form or otherwise. Keeley was not only a quack — though he deserves some credit for treating alcoholism as a disease instead of a moral failing — but also a purveyor of fool’s gold.

Further reading:

Higby, Gregory J. “Gold in Medicine: A Review of Its Use in the West Before 1900.” Gold Bulletin, 1982, 15, (4).

Lender, Mark Edward and James Kirby Martin. Drinking in America: A History. Free Press, 1987.

October 19, 2015

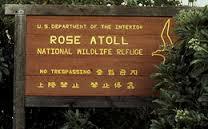

For Love and Adventure: Rose Pinon de Freycinet’s Trip Around the World

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor) The first woman to circumnavigate the globe and write about it was a 19-year-old French bride who, in 1817, sailed on the ship L’Uranie from Toulon, headed for Australia. Her husband Louis de Freycinet was the ship’s 35-year-old captain. He knew that any request to allow his wife to accompany him would be denied. So he had an extra cabin built on the ship, claiming it would be a storehouse for botanical specimens collected on the voyage, but secretly he was preparing it as accommodation for young Rose. As she would narrate the event in letters to her sister Caroline Pinon, Rose boarded the ship in September 1817, dressed “as a man in a blue frock coat with trousers to match”, and introduced by her husband as the son of a friend. The new passenger stayed in her cabin as much as she could for the first few days of the voyage. But once the ship had made its last stop on European soil, in Gibralter, the couple decided it was both safe and necessary to reveal Rose’s true identity.

The first woman to circumnavigate the globe and write about it was a 19-year-old French bride who, in 1817, sailed on the ship L’Uranie from Toulon, headed for Australia. Her husband Louis de Freycinet was the ship’s 35-year-old captain. He knew that any request to allow his wife to accompany him would be denied. So he had an extra cabin built on the ship, claiming it would be a storehouse for botanical specimens collected on the voyage, but secretly he was preparing it as accommodation for young Rose. As she would narrate the event in letters to her sister Caroline Pinon, Rose boarded the ship in September 1817, dressed “as a man in a blue frock coat with trousers to match”, and introduced by her husband as the son of a friend. The new passenger stayed in her cabin as much as she could for the first few days of the voyage. But once the ship had made its last stop on European soil, in Gibralter, the couple decided it was both safe and necessary to reveal Rose’s true identity.

At home, the news was already out, angering Louis Freycinet’s superiors and creating a sensation in the papers. The Moniteur Officiel reported the escapade on October 4, emphasizing both the official transgression and its romantic inspiration:

“News has broken out in Toulon that Madame de Freycinet who had accompanied her husband to the port of embarkation had disappeared thereafter and, dressed as a man had gone on board the ship that same night, despite the ordinances that prohibit the presence of women in state vessels, without official authorisation. This example of conjugal devotion deserves to be made public.”

The voyage of the Uranie would take three years. Both Louis, in his published official account of the voyage, and Rose, in her letters home to Caroline, gave detailed descriptions of their adventures at sea and on land in Australia, Hawaii, the Sandwich Islands, South America, and many other stops on their journey to explore and collect scientific information. But reading the published account of the trip written by the ship’s captain, one would not know that his wife had been on board. Perhaps wary of the price he would have to pay for having violated protocol by bringing her with him, he makes no  mention of her presence on the ship. There is only one moment when he acknowledges it, obliquely, when he reports on the naming of a small island off the coast of Australia (now in American Samoa). He named it, he writes, after “a person who is precious to me.”

mention of her presence on the ship. There is only one moment when he acknowledges it, obliquely, when he reports on the naming of a small island off the coast of Australia (now in American Samoa). He named it, he writes, after “a person who is precious to me.”

On their return trip, off the coast of an uninhabited Falkland Island in February of 1820, the ship was badly damaged when it ran against a rock. The terrified passengers and crew had to abandon the sinking vessel. Rose describes the tension on board as they all slowly realized the ship could not be saved, the difficult passage to shore, and the depravation and hardship encountered on land. But within a month, the crew was able to build another boat, small but seaworthy. This boat sailed to the mainland and was able to arrange rescue for the castaways.

In addition to Louis and Rose, other passengers on the voyage of the Uranie were keeping records. Jacques Arago, an artist who had been commissioned to provide illustrations of the expedition, produced drawings in which Rose can clearly be seen, and he wrote admiring descriptions of her in his accompanying narrative. Alphonse Pellion, another illustrator and draughtsman on board, made drawings of different moments in the voyage that were used in Freycinet’s official report. Some of the illustrations used in that report were revised from earlier versions, with the effect of erasing Rose from the record. In his first version of a drawing showing a campsite of the Uranie community after they landed on the west coast of Australia, Rose can be seen standing outside her tent, on the right side of the painting. In the second, ‘authorized’ version, this figure of a woman has disappeared from the scene.

In addition to Louis and Rose, other passengers on the voyage of the Uranie were keeping records. Jacques Arago, an artist who had been commissioned to provide illustrations of the expedition, produced drawings in which Rose can clearly be seen, and he wrote admiring descriptions of her in his accompanying narrative. Alphonse Pellion, another illustrator and draughtsman on board, made drawings of different moments in the voyage that were used in Freycinet’s official report. Some of the illustrations used in that report were revised from earlier versions, with the effect of erasing Rose from the record. In his first version of a drawing showing a campsite of the Uranie community after they landed on the west coast of Australia, Rose can be seen standing outside her tent, on the right side of the painting. In the second, ‘authorized’ version, this figure of a woman has disappeared from the scene.

But the historical record can be revised and it can also be reconstructed. New discoveries about the Freycinet expedition continue to be made. The submerged wreck of the Uranie was lost for nearly two centuries, only discovered after an ambitious underwater expedition in 2001. And a new edition of Rose’s account of her voyage, based on the manuscript of her letters home, and including original versions of the illustrations, was published in 2003.

But the historical record can be revised and it can also be reconstructed. New discoveries about the Freycinet expedition continue to be made. The submerged wreck of the Uranie was lost for nearly two centuries, only discovered after an ambitious underwater expedition in 2001. And a new edition of Rose’s account of her voyage, based on the manuscript of her letters home, and including original versions of the illustrations, was published in 2003.

For further reading: A Woman of Courage: The Journal of Rose de Freycinet on her Voyage Around the World, 1817-1820. Translated and edited by Marc Serge Rivière. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2003.

October 15, 2015

The Woman Who Modeled for Impressionists

By Stephanie Cowell (Regular Contributor)

In 1860 Paris, the lovely models strolled around the famous fountain at Pigalle, hoping an artist would approach to hire them for a few hours or longer. In the winter perhaps they waited in a café, nursing a coffee or an absinthe.

Beauty for Hire

They were not cheap for a poor artist such as the struggling Renoir or Monet; a woman could expect four or five francs for a three-hour session, though that was less than the cost of one of the more expensive new tubes of oil paint. The women were paid more than male models because the height of their beauty had a shorter season, but an artist had to buy coal for his stove to warm her and often endure the presence of her mother as chaperone.

Sometimes the young male artists fell in love with their models. Aline Charigot was a seamstress when she met Renoir, but Claude Monet’s lovely Camille Doncieux was of good family and was largely disowned by them when she took off to live in poverty with Claude without so much as a wedding ring.

Edouard Manet had several models. He painted his wife nude but he soon was painting his exquisite artist colleague Berthe Morisot; conjecture varies to this day whether she did more than model for him. His most famous model was likely from the Pigalle professional models. She was Victorine Meurent who posed as Olympe lying nude on a sofa which so enraged the public when it was first shown that men tried to ram umbrellas through it. Manet loved women and who knows what may have occurred between him and the red-haired Victorine?

Growing Reputations, Fading Loves

The years passed and by 1880 the group of men now known as the impressionists slowly became better known. Claude Monet’s love would die tragically young and Renoir’s Aline grow old, fat, a mother of sons, and greatly loved. And Victorine?

Ah, Victorine! Edouard Manet promised to leave her something when he died and she wrote a wistful note to his widow reminding her and saying that she was in need. As far we know, the request was never answered.

And the wintry days waiting for a job at the Pigalle fountain? In 1885 one of the models opened an agency for his colleagues in the boulevard de Clichy and painters and sculptors came there to make their choice not from the models themselves but their photographs. By then the womens rate was ten francs an hour, more if she were very pretty.

Stephanie Cowell, a former classical singer, is the author of five books, including her most recent, Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet. She lives in New York, with her husband, a poet and reiki practitioner, not far from all the impressionist paintings at the Metropolitan Museum.

Stephanie Cowell, a former classical singer, is the author of five books, including her most recent, Claude & Camille: A Novel of Monet. She lives in New York, with her husband, a poet and reiki practitioner, not far from all the impressionist paintings at the Metropolitan Museum.

IMAGES: Monet’s first painting of his love Camille

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in April 2010.