Holly Tucker's Blog, page 19

January 21, 2016

Breastfeeding… the Grandchildren? Wondrous Early Modern Tales of Aged Women

By Lisa Smith (Former Regular Contributor)

A poor woman in a dingy attic, surrounded by her children, one of whom she is breast-feeding. Engraving by N. de Larmessin III after J. Pierre. Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Whenever a hungry infant grandchild rooted for my mother’s breast, she would joke that “there isn’t any milk left in this old cow” and passed the child back to my sister for feeding. She clearly just wasn’t trying hard enough. After all, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society printed cases of aged women who found themselves able to breastfeed their grandchildren…

In 1674, “A Person of Great Veracity” recounted two cases of breastfeeding grandmothers, one of which happened within his own family. Two months previously, the family had hired a nurse for their little girl, which entailed the nurse weaning her own son. But the boy kept “sucking the Breasts of his Grand-mother”, which caused “such a commotion in her, that abundance of milk run to her Breasts for a sufficient nourishment”.

To provide added authority, the author referred to a similar case from Vienna that had been described by Dutch physician Diemerbroeck. A poor woman gave birth to a healthy boy, but both the father and she died soon after. The sixty-six year old grandmother, Joanna Vuyltuyt, took in the child, but had no money to hire a nurse. She desperately attempted to feed the baby herself. “From that old woman’s strong imagination and vehement desire to give suck to this child”, she soon produced a good quantity of milk, and “all that saw it much wondered at” it.

Diemerbroeck and the “Person of Great Veracity” each provided a medical explanation for the cases: a physical reaction to stimulation or imagination and will. Both explanations made sense within the early modern medical world, depending on whether one saw the body as a machine filled with pumps and valves or a body that was intricately connected to one’s mind. There was a third reaction, however: wonder. This was, after all, no ordinary bodily behaviour.

Thomas Stack submitted a letter to the Phil. Trans. in 1739 about a sixty-eight year old grandmother “Who Gave Suck to Two of Her Grand-children”. Stack first heard of the case from “a gentleman of credit” who offered to take him to the breastfeeding granny of Tottenham Court Road (Elizabeth Brian) in London. The plan, this time, was to “discover some Fallacy in the Affair”; wonders were treated much more sceptically by 1739 than they had been sixty years earlier. Stack’s first impressions of the story’s plausibility were favorable: “Her Breasts were full, fair, and void of Wrinkles”, although the woman otherwise looked as old as might be expected for one who had spent the “last Half of her past life in Labour, troubles, and other concomitants of Poverty”.

Mrs Brian had not borne a child for twenty years, but had been breastfeeding her grandchildren for the last four years. Again, this was a case of financial and physical necessity. The mother had left the first infant with her mother and was “likely to be a considerable time absent” (presumably for employment). The little girl did not take to the forced weaning well, though, and was “froward for want of the Breast”. To keep the child quiet, the grandmother let her suckle and after several occasions of this, Mrs Brian’s son noticed that the child seemed to be swallowing something. The son “begg’d leave of his mother to try if she had not milk”. The son “drew Milk from that same Breast from which he had been wean’d above Twenty years”.[1] From that point on, Mrs Brian breastfed the child and was so successful that the daughter decided to have another baby, given that she had such a capable nurse.

Stack examined both girls, noting that they were healthy and sprightly. He also observed the youngest feed to make certain that the baby was truly drawing out milk. Stack did not offer any medical conclusions, but did determine that “the poor Woman seems perfectly honest and artless”. Mrs Brian, however, had an explanation: “She very religiously throws the whole upon a miracle”. And so it must have seemed.

Unusual cases, certainly, but not impossible. Modern medicine has found that milk can be produced by men and non-childbearing women, whether as a bodily malfunction (over-production of prolactin) or–most relevant in each of the early modern cases–as an adaptive measure to cope with maternal loss. In such cases, extreme psychological stress and stimulation of the nipple can result in the ability to breastfeed.[2] We might now have scientific studies, but that explanation sounds rather similar to the ones provided by Diemerbroeck and “A Person of Great Veracity” back in 1674.

In any case, despite my mother’s insistence, there could still be milk left in the old cow (sorry, Mom!)—but thank goodness it was never necessary.

[1] Early modern people were much less troubled by breast-feeding, even for adults. Very ill people might be breast-fed, while squirting breast-milk directly into the eye was often used for eye problems.

[2] Sobrinho, Luis Gonçalves. “Prolactin, Psychological Stress and Environment in Humans: Adaptation and Maladaption”. Pituitary 6 (2003): 35-39.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in June 2014.

January 19, 2016

When businesses operate like the Third Reich

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

During the 1945-46 International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, an American psychiatrist compared the structure of the Nazi leadership to the organization of a runaway corporation. How many firms today are built the same way?

Nazi leaders Hermann Göring, Karl Dönitz, Walther Funk, Baldur von Schirach and Alfred Rosenberg dine during their war crimes trial.

When I wrote my book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books), which is about Kelley’s involvement with the Nazi leaders and the consequences of his experience, I was surprised to learn how the psychiatrist’s insights into the leadership structure of the Third Reich can guide businesses today.

In 1945, U.S. Army psychiatrist Douglas McGlashan Kelley arrived in Nuremberg to study the psyches of the top 22 German officials charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity. He found that these men — including Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, and Albert Speer — were not mentally ill. In fact, under Adolf Hitler’s direction, they had organized themselves in a governmental hierarchy that Kelley found strikingly like that of a modern corporate board.

It was a dysfunctional board, however, with the Nazi leaders occupying four silos under CEO Hitler: a brain group that shaped Nazi ideology, culture, and policy; a marketing group that sold Hitler’s ideas to the world; a group of enforcers who used military and police might to crush dissent and ensure results; and a team of bureaucrats expert in finance, law, and planning who attended to the details.

Each group had little contact with any other. Only Hitler oversaw and understood the activities of the different compartments, and he grew dangerously irrational as World War II went on. Kelley found out, for instance, that Hitler planned to attack the Soviet Union much earlier than his advisors recommended because the Führer feared that stomach cancer would soon kill him. A hypochondriac and hysteric, he had no stomach cancer. But Hitler proceeded as if he did, prematurely launching Operation Barbarossa against the U.S.S.R. on June 22, 1941, and none of his subordinates could stop him. The Soviets ultimately forced back Hitler’s invasion, which proved to be a turning point in the war.

Any business that fails to provide its organizational groups with information and updates from other departments faces the same potential for disaster, especially when one or a small number of executives hoard knowledge of the entire firm’s operations.

Further reading:

Kelley, Douglas M. 22 Cells in Nuremberg. McFadden Publications, 1961.

World Future Fund. “Nazi Germany, Government Structures, Ministries and Party Organizations.”

January 18, 2016

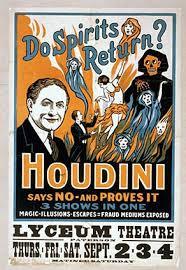

Sarah Bernhardt Meets Harry Houdini

by Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

In 1916, Sarah Bernhardt made a tour of the United States. She was probably the most famous actress in the world by this time. But she was 71, and not in good health. In 1915 she had suffered a gangrenous infection after a stage accident which had almost killed her and resulted in the amputation of her left leg. Any other diva would have declared an end to her career after such an episode, but Bernhardt could not bear to abandon the theatre. And her audiences loved her more than ever. The voyage to America was triumphant. In New York she performed her famous cross-dressed role of Napoleon Bonaparte’s son in L’Aiglon, by Edmond Rostand. In Brooklyn she appeared before a crowd of 50,000 to speak in support of Franco-American cooperation in the war effort.

In 1916, Sarah Bernhardt made a tour of the United States. She was probably the most famous actress in the world by this time. But she was 71, and not in good health. In 1915 she had suffered a gangrenous infection after a stage accident which had almost killed her and resulted in the amputation of her left leg. Any other diva would have declared an end to her career after such an episode, but Bernhardt could not bear to abandon the theatre. And her audiences loved her more than ever. The voyage to America was triumphant. In New York she performed her famous cross-dressed role of Napoleon Bonaparte’s son in L’Aiglon, by Edmond Rostand. In Brooklyn she appeared before a crowd of 50,000 to speak in support of Franco-American cooperation in the war effort.

But there had been another reason for her trip. ‘The Divine Sarah’ was fascinated with a fellow artist who was as famous as she, the great magician Harry Houdini.

Houdini’s tricks were so spectacular that spectators found it difficult to believe in their artifice. Although he himself never claimed true magical powers (and in fact throughout his career he exposed magicians who did make such claims), there were many who thought he had occult powers. Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the eminently rational Sherlock Holmes, was one of those who would persist in this belief long after Houdini’s death. It was an age when it was not unusual to hear of prominent intellectuals and political figures gathering soberly around a seance table.

Bernhardt was given to such beliefs. While on her American tour, she attended some of Houdini’s outdoor escape performances in Boston and New York. The experience confirmed her faith in his special powers. As for Houdini, he was flattered that the great actress admired him and he readily accepted her return invitation to watch her on stage, with a private meeting to follow.

But her conversation took him by surprise. Looking at him earnestly, she asked if he would consider applying his magic to the task of regenerating her lost leg. “She honestly thought I was superhuman,” he would later report to a journalist.

One of the most poignant photographs of Sarah Bernhardt is a snapshot that was taken immediately following her interview with the great illusionist. Houdini is in profile, standing outside the car just after saying goodbye to the actress. Through the window we see Bernhardt’s face looking at him intently, wearing an expression of profound sadness.

One of the most poignant photographs of Sarah Bernhardt is a snapshot that was taken immediately following her interview with the great illusionist. Houdini is in profile, standing outside the car just after saying goodbye to the actress. Through the window we see Bernhardt’s face looking at him intently, wearing an expression of profound sadness.

Photo of Houdini and Bernhardt courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center, Austin TX

January 16, 2016

Mercy Street: A Television Show, A Book, and A Giveaway

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Tonight, like much of America, I plan to sit down and watch the first episode of PBS’s new historical drama about nurses in the Civil War, Mercy Street. (If you’ve watched anything on PBS or gone to the movies in the last few weeks you’ve probably seen the promotions for it.) Mercy Street uses a real Civil War hospital as the setting for a fictionalized (and quite gorgeous) drama. I’m looking forward to the show, but unlike everyone else in tonight’s audience I’ll be waiting breathlessly for the promotional spot at the end of the show, when PBS plugs DVDs of the show and my book, The Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War. My heart beats a little faster just thinking about it.

Tonight, like much of America, I plan to sit down and watch the first episode of PBS’s new historical drama about nurses in the Civil War, Mercy Street. (If you’ve watched anything on PBS or gone to the movies in the last few weeks you’ve probably seen the promotions for it.) Mercy Street uses a real Civil War hospital as the setting for a fictionalized (and quite gorgeous) drama. I’m looking forward to the show, but unlike everyone else in tonight’s audience I’ll be waiting breathlessly for the promotional spot at the end of the show, when PBS plugs DVDs of the show and my book, The Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War. My heart beats a little faster just thinking about it.

The Heroines of Mercy Street focuses on the same Civil War hospital as the series–Mansion House hospital in Alexandria Virginia–and some of the nurse who worked there.

When I began working on the book, I thought I knew something about Civil War nurses. Clara Barton first caught my imagination when I was seven or eight, thanks to a child’s biography that belonged to my mother. I had read Louisa May Alcott’s charming fictionalized account of her brief stint as a nurse in Washington D.C. . I had spent enough time at Civil War battlefields to learn more than I really wanted to know about amputations, conditions in field hospitals, and the symptoms and causes of dysentery.

I soon found that what I knew was only the beginning of the story.

By one estimate, more than 20,000 women served as nurses during the war, not including an unknown number of informal volunteers who put on aprons and rolled up their sleeves to help. They were as diverse as the new and expanding nation from which they were drawn: teenage girls, middle-aged widows, and grandmothers; society belles, farm wives, and factory girls; teachers, reformers, and nuns; free African-Americans and escaped slaves; new immigrants and Mayflower descendants. Some worked from patriotic zeal or a sense of adventure; others took the work because they needed the money. (In theory, the Union army paid $12 a month plus board, rations, and transportation; in practice nurses’ salaries were often months in arrears.) What they had in common was the physical capacity to do the work and a willingness to serve.

The women who worked at Mansion House can be seen as a microcosm for the medical experience of the war. Its nurses did battle with hostile surgeons, corrupt house stewards, dirt, filth, inadequate supplies, and their own lack of training. They fought to make sure their patients received the care they needed along with minimal comforts, wept for those they lost, raged at the enemy, and raged even harder against the indifference and inefficiency that left wounded men lying on the battlefield without care. They learned to dress wounds, bathe naked men with whom they had no familial relationship (not an easy adjustment to make at the height of Victorian prudery), and evacuate the building in case of fire. Worn out by the grinding nature of the work and exposed constantly to diseases, they themselves fell sick, often with no one to nurse them in their turn. Some lasted less than a month; others made the leap from volunteer to veteran. By war’s end their collective experience, along with that of nurses across the country, had convinced Americans that nursing was not only respectable but a profession.

To celebrate the publication of The Heroines of Mercy Street on February 16, I’ll share stories here about some of my favorite Civil War nurses over the next few weeks. You have a chance to share in the celebration, too. We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win. In the meantime, enjoy the show.

January 14, 2016

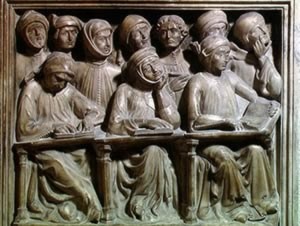

On the Shortcomings of University Students

By Marri Lynn (Guest Contributor)

It’s become a commo n conceit to think that the disappointing student is a modern invention. Lecture-halls filled with napping students and dull eyes are, we often think, the lamentable but inevitable result of such distractions as Facebook, cell phones, and the devaluation of education for education’s sake.

n conceit to think that the disappointing student is a modern invention. Lecture-halls filled with napping students and dull eyes are, we often think, the lamentable but inevitable result of such distractions as Facebook, cell phones, and the devaluation of education for education’s sake.

We may take heart – or despair at the persistence of the habits of the errant student — in learning that these complaints are as old as university education itself.

The Franciscan Alvarus Pelagius turned his talent for social critique (honed in penning De planctu ecclesiae libri duo, a prose campaign for curbing ecclesiastical excess) toward his experiences of students, resulting in a short but pointed tract. The university students that Pelagius complained of numbered among a select few afforded the privilege of attending university in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

It was a privilege and an historical moment which, according to Pelagius, was completely wasted on them.

These students were opinionated, ignorant partiers who engaged in gambling and drinking with more gusto than they ever applied to their education. If they bothered to go to class, they were merely physically present, letting the words of their educated masters flow in one ear and out the other. The exception to this rule was when “forbidden sciences, amatory discourses, and superstitions” (timeless student favorites) came up in a lecture; these the student would learn avidly, when they should be ignored.

Students skipped church, choosing to “gad about town with fellows.” When they did deign to attend church, it was to see girls and exchange stories, not to worship – a fact which seemed to especially displease Pelagius.

Above being merely self-destructive, these students harmed others: When they weren’t shirking their spiritual duties or studying amatory discourses, they were busy trying to entangle themselves in the gears of the university administration by forming illicit students’ societies and fraternities in order to promote their favorite professors on the basis of personal affection and whim. And, of course, they would take their expense money from parents and spend it in taverns and games, only to eventually flee the university (with outstanding fees), bereft of knowledge, conscience, or money.

Those students of the twenty-first century who do not rise above the lowest common denominator are, at least, keeping a centuries-old tradition alive.

Marri Lynn is a freelance writer with a MA in the History of Medicine from McGill University, Montreal. You can find out more about her other projects at her About.me page.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in October 2011.

January 13, 2016

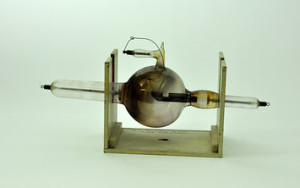

Museum Mysteries: Walter Dodd and His X-Ray Tube

Walter Dodd’s X-ray tube.

By Sarah Alger

On display at the Russell Museum is the first X-ray tube to be used at Massachusetts General Hospital. Mounted on a small wooden stand and its interior dulled with soot, its modesty belies the story of its extraordinary owner.

Walter J. Dodd was born in London in 1869 and came to the United States when he was ten. While working as a janitor at a Harvard chemistry lab, he picked up chemistry from preparing class materials and sitting in on lectures, and joined MGH in 1892 as an assistant apothecary. Three years later he became apothecary in chief, a position he would hold for 13 years. He was also the hospital’s photographer, so when Roentgen published in 1895 his paper about the mysterious X ray, it was natural that Dodd would look into this discovery. In 1896 Dodd would make the first X ray at a Boston hospital (the first in America was made at Dartmouth).

His interest and skill burgeoned; he became the in-house expert, treated as a peer by physicians. Ultimately he decided to pursue a medical degree. At first he took classes in Boston, but distracted by his work at MGH, he went north to the University of Vermont. (Can you imagine? Having to escape the state so you can concentrate on medical school.)

Walter Dodd, posed to disguise his injured fingers. Oil painting by Pietro Pezzati.

You can guess where this story is headed. To test that his X-ray tube was working properly, Dodd would wave his hand in front of it, and even after the dangers of radiation came to light, he continued to do so. The pain in Dodd’s hands became so great that he had to rest them in pans of cocaine solution so he could sleep. Dodd would endure 50 operations to remove bits of his fingers and would eventually succumb to his injuries in 1916.

Why did he persist with his work? Friend and colleague John Macy, who wrote a biography of Dodd, noted: “In his nature cheerfulness and intrepidity merged into recklessness and obstinacy. Though he endured untellable torments, he made light of his sufferings.”

By Macy’s account and others, Dodd’s charm and good cheer are legendary. When I regard his X-ray tube, I choose to think about my favorite anecdote I’ve come across in our archives:

“One day, as the Resident Physician was sitting at his desk in the office by the old Blossom Street entrance of the Bulfinch Building, Walter Dodd came in, looking depressed, and said: ‘I report that I have just been thrown out of the Treadwell Library.’ The Resident Physician asked what the trouble was. Walter replied, ‘I told Mrs. Myers what I thought was a funny story, to the effect that a very pompous alderman, by the name of Hooley, marched down the aisle of the Cathedral one Sunday morning, whereupon the choir began to sing, ‘Hooley, Hooley, Hooley, Lord God Almighty.’ Mrs. Myers said to me, ‘Walter Dodd you get right out of my Library, and don’t you return until you apologize.’”

January 11, 2016

Le bruit de diable: gunpowder, tops and purring cats

by Helen King (Monthly Contributor)

Laennec-type monaural stethoscope, France, 1851-1900

Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images

No, this isn’t a telescope, it’s a stethoscope. René Laennec (1781-1826) invented this device in 1816, as a way to solve the ethical dilemma of having to put his ear to the chest of a young woman patient. He started with a rolled up piece of paper to help him hear her heart and her breathing, but then developed a wooden device. We are now most familiar with the binaural – two ears – stethoscope, but the earliest examples, like this one, were monaural.

The label ‘stethoscope’ suggests ‘looking at the chest’, on the model of ‘telescope’ – looking at something far off – or ‘microscope’ – looking at something very small. But, of course, this isn’t a visual device: it’s about a different sensory mode of knowing the body. Like any new piece of medical technology, it wasn’t an instant success, because physicians needed to be trained to identify what they heard. One of the sounds they heard clearly with the stethoscope came to be known as ‘le bruit de diable’, ‘the devil’s sound’. It was described by Richard Cabot in 1908 as ‘a soft, continuous humming heard by the stethoscope over the veins of the neck’. Today it’s more likely to be called a ‘venous hum’. It’s generally harmless.

So why ‘the devil’s sound’? Earlier imagery for this special background hum had been more benign. Walter Johnson described it in 1849 as like the sound of the sea heard when putting a shell to one’s ear. He wrote that, at Guy’s Hospital, the sound was called the ‘tearing-cotton murmur’. Most poetically of all, in 1872 Armand Trousseau wrote of a sound like ‘the purring of a cat when it is being caressed, or the noise of a spinning-wheel’.

So, why the devil? When I first wrote about this sound, in my book The Disease of Virgins, I assumed that the devil’s presence was heralded by a strange humming noise. Wrong! I’ve now found a piece in The London Medical and Surgical Journal for 1836 which makes it all clear. In a short guide to chest sounds ‘M.R.’ explains that direct listening to the chest is difficult because the friction of the physician’s head on the patient’s body can confuse the sounds. He helpfully tells us that ‘many persons are agitated by the use of the stethoscope’, so the physician should wait until they calm down again. He explains different sounds such as the ‘mucous rattle’ and the ‘crepitant rattle’, or wheeze, and tells the reader both what they resemble and what they mean. In another article, ‘R.’ describes how the condition of the heart can be understood by listening to it, and in particular describes the bruit de diable as an ‘intense degree’ of an arterial sound called bruit de soufflet. The ‘diable’ here, he explains, is from a sport which ‘consists in igniting a train of gunpowder or some other inflammable matter, which gives a continuous whizzing sound, according to some; and to the noise of a humming-top, according to others’.

So it’s not about the devil at all. One variation of the humming top is still known to us as the diabolo. The two different explanations for the use of this label for the sound are interesting because they show how hard it is to create analogies for something we hear. Thanks to the wonders of the internet, you can hear it for yourself. To me, the ‘bruit de diable’ sounds quite different from the ‘continuous whizzing’ of a gunpowder trail igniting, and not much like a top either; I’d say it sounds like static on a radio or TV, but of course both of these technologies were still a long way away in 1836. Hearing the sounds of the body is far from straightforward, and sharing what you hear depends on a common knowledge of sounds – which in turn will inevitably depend on your culture!

So it’s not about the devil at all. One variation of the humming top is still known to us as the diabolo. The two different explanations for the use of this label for the sound are interesting because they show how hard it is to create analogies for something we hear. Thanks to the wonders of the internet, you can hear it for yourself. To me, the ‘bruit de diable’ sounds quite different from the ‘continuous whizzing’ of a gunpowder trail igniting, and not much like a top either; I’d say it sounds like static on a radio or TV, but of course both of these technologies were still a long way away in 1836. Hearing the sounds of the body is far from straightforward, and sharing what you hear depends on a common knowledge of sounds – which in turn will inevitably depend on your culture!

January 8, 2016

Two or Three Things I Know about Pigs (Part One)

By Thomas Parker (regular contributor)

The Ancient Greeks claimed that no other flesh tasted as much like human flesh as pork. In fact, it was said that unscrupulous tavern owners would sometimes serve human meat, passing it off as pork, though little is known about where they sourced their humans or what the incentive (financial or otherwise) would be to do this.

Pigs and humans share much more than the same flavor. Omnivores, like humans, pigs have been able to go where humans go, thriving not only on foraged oak acorns and woodland mast, but also on human leftovers and refuse, making them what Donna Haraway would call a great “companion species.”

Indeed, in Papua New Guinea, pigs double for humans symbolically so much so that women have been known to breastfeed piglets to help them survive (Dwyer, Minnegal, 2005).

Ceremonial Pig Skull- Latmul Peoples- New Guinea. Childrens’ Museum of Indianapolis

Still, sometimes the proximity of hog and human culture has led to pushback throughout the ages. Anthropologists have surmised that the fact that they had cloven hooves but were not ruminants made them anomalous creatures, banned from Jewish and Islamic tables. More recently, as pork became more popular in the colonial United States, it became increasingly derided. William Byrd II, a Virginian living at the time of the American Revolution, declared that North Carolinians ate so much pork that they began to resemble pigs physically and became, “extremely hoggish in their temper, and many of them seem to grunt rather than speak in their ordinary conversation.” (Mitzelle, 2013).

As close as the hog-human bond can be, some of the best pig stories are those that arrive when hogs are separated from humans. This year, my wife and I celebrated the New Year with friends by roasting a whole hog. The party was a success, and why not? In many cultures eating pig on New Years Day is meant to bring luck (presumably because a family who can sacrifice a pig is already prosperous). But our pig symbolized a wrinkle in pig-human relations.

A French New Year’s Eve Postcard (see Michael Garval’s excellent article on French pig postcards here)

Ours was a rare Ossabaw Island Hog, a roaster that enthusiasts claim to be second to none in terms of flavor and purity. That perfection —and it was jaw-droppingly delicious— comes not from human intervention and generations of hybridization, standardization, and homogenization by farmers and Big Pork in search of the perfect pig. Instead the Ossabaws’ goodness owes to the fact that they spent 500 years away from human culture.

Ossabaw Island’s main road. Photo credit: Laura Drummond.

Pigs arrived on Ossabaw Island, a small barrier reef off the coast of Georgia, with Spanish explorers at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Some were left behind and quickly turned feral. There, they acquired an unprecedented ability to forage off the island’s sparse food offerings and drink water with a high percentage of salt. They also acquired insular dwarfism in order to survive (a full-grown female can weigh as little as 100 pounds) and the ability to store fat prodigiously (no other non-domestic animal is as efficient).

That high fat content and the ability to store fat makes the pigs tastier, but also makes them prone to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Ironically, that fat also saved them. In the early 2000s, the animals were considered a menace to native populations of sea turtles on the largely undeveloped Ossabaw Island to the point that Georgian conservationist authorities contemplated eradicating them.

An Ossabaw Pig. Photo credit: livestockconservancy.org

Plans for the pigs changed because 1) Medical authorities sought them out, examining possible gene mutations in Ossabaws in order to understand diabetes and heart disease in humans. 2) High-profile chefs discovered how tasty the meat was, and advertised the merits of Ossabawness (Weiss, 2015).

The fame of the Ossabaws did not save them from being eaten, as was Wilbur’s case. Rather they were saved by being eaten. And saved, somewhat ironically, in the midst of all that good fat, by the shared hog-human susceptibility to heart disease.

New Years Eve- “Some Pig!”

1) Peter Dwyer and Monica Minnegal, “Person, Place, or Pig: Animal Attachments and Human Transactions in New Guinea,” in Animals in Person: Cultural Perspectives on Human-Animal Intimacies, ed. J. Knight, Oxford and New York, 2005, pp. 37-60.

2) Brett Mizelle, Pig, London, 2001.

3) Brad Weiss, “Hybrids, Breeds, and Brands.” Paper presented at “Pig Out: Hogs and Human in Global and Historical Context,” Yale, 2015.

January 7, 2016

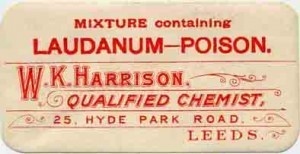

Poetry, Pain, and Opium in Victorian England

By Stephanie Cowell (Former Regular Contributor)

Elizabeth Barrett began to take laudanum, a tincture of opium, for what is thought to have been a spinal injury at the age of fifteen. It is believed she continued to take it through two more serious illnesses in her early 30s (hemorrhaging of the lungs and some extended unspecified illness). It was almost impossible for her to stop it once she had begun it and it worked for and against her.

Elizabeth Barrett began to take laudanum, a tincture of opium, for what is thought to have been a spinal injury at the age of fifteen. It is believed she continued to take it through two more serious illnesses in her early 30s (hemorrhaging of the lungs and some extended unspecified illness). It was almost impossible for her to stop it once she had begun it and it worked for and against her.

Laudanum is an alcoholic herbal preparation which contains about 10% opium; it is very bitter. It was used for many purposes, principally a pain reliever and cough suppressant. She took it for emotional and physical reasons: to slow her rushing heart and to help her sleep, to suppress the cough which could bring on bleeding. It became for her a general panacea. The drug was also used against menstrual cramps.

Laudanum was entirely uncontrolled in the Victorian era; few people took its side effects seriously. Bouts of euphoria were followed by bouts of depression, slurred speech, restlessness, poor concentration while withdrawal could produce muscular aches and abdominal cramps, agitation, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. But even infants were spoon fed laudanum and it was not until years after that people realized it was addictive.

An anonymous report, published in The Journal of Mental Sciences January 1889 and called “Confessions of a Young Lady Laudanum-Drinker,” is rather horrifying. The woman wrote, “Laudanum got me into such a state of indifference that I no longer took the least interest in anything, and did nothing all day but loll on the sofa reading novels, falling asleep every now and then, and drinking tea. My married sisters… said I always seemed to be in a half-dazed state, and not to know what I was doing….my memory was getting dreadful.“ After a time, the young woman quit cold, a great difficulty. “My principal feeling was one of awful weariness and numbness at the end of my back; it kept me tossing about all day and night long. It was impossible to lie in one position for more than a minute, and of course sleep was out of the question. Does anyone who has gone up to three or four ounces a day, and is suddenly deprived of it, live to tell the tale! “

When the poet Robert Browning visited Elizabeth, who was by then much weakened by laudanum and lack of exercise (her family kept her in her room or in the house from fear of what the wretched London fog would do to her lungs), he probably did not understand the extent of the laudanum use. Browning knew she needed to escape from her autocratic father who would not let any of his grown children marry and thus he swept her away to live in Italy. There she regained remarkably good health, though she continued to miscarry her children until Robert and her maid Wilson convinced her to reduce her laudanum dose. Then she bore a healthy child.

When the poet Robert Browning visited Elizabeth, who was by then much weakened by laudanum and lack of exercise (her family kept her in her room or in the house from fear of what the wretched London fog would do to her lungs), he probably did not understand the extent of the laudanum use. Browning knew she needed to escape from her autocratic father who would not let any of his grown children marry and thus he swept her away to live in Italy. There she regained remarkably good health, though she continued to miscarry her children until Robert and her maid Wilson convinced her to reduce her laudanum dose. Then she bore a healthy child.

But for those patients who took laudanum so regularly in the Victorian era, we must consider that there were few other pain relievers until aspirin in 1899. If Mrs. Browning had had antibiotics, she might have cured her lung infection. A mild tranquillizer would have calmed the agitation she felt living with her father (I suspect she had tachycardia). A bit of Ambien or Tylenol PM would have let her sleep. She would not have been so weak.

My research into Elizabeth Barrett Browning is fraught with unanswered questions as must be the research into the health and remedies of most historic people in the Victorian era or earlier. I have read her dosage was at least four times that of the average dosage of opium today. If so, how did she write so much poetry, so many letters? Did it help or harm her? It seems she had pretty good health in the five years after she went to Italy. She could climb steep hills, walk for hours, endure days of jolting carriage rides. When her maid went on holiday, she cared for her toddler. Her health declined around the fifth or sixth year of marriage. Final photographs of her show a very sick woman. Sometimes she could not walk from bed to chair. Did laudanum help her? Or did it hasten her death?

Other laudanum users of the 19th century include Byron, Shelley, Keats, Dickens, Poe, Coleridge, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, the British model, poet, and artist, died of an overdose.

Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie is finishing a novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in February 2013.

January 6, 2016

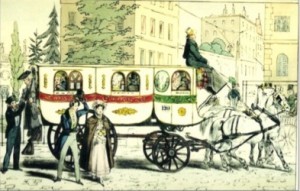

What Not to Wear on the Omnibus

By Masha Belenky, Guest Contributor

If you have recently been on the subway in New York City, you may have noticed a curious ad: “Dude… Stop the Spread…Please. It’s a space issue.” The public service announcement aims to curb the pesky behavior known as “manspreading,” an annoying habit of men sitting with their legs wide apart, encroaching on other seats. First coined by feminist social media, manspreading is unambiguously gendered: a display of male privilege and a way for men to claim public space as exclusively theirs.

Yet these issues surrounding modern locomotion and public space are not new to culture; they surfaced the moment  that public transportation became a salient feature of modern urban life, in nineteenth-century Paris. When the first horse-drawn public conveyance, the omnibus, or l’omnibus hyppomobile, appeared in Paris in April 1828, it immediately attracted popular writers and artists interested in the study of contemporary everyday life. It served as a perfect social laboratory, a microcosm of society and the tensions that agitated it.

that public transportation became a salient feature of modern urban life, in nineteenth-century Paris. When the first horse-drawn public conveyance, the omnibus, or l’omnibus hyppomobile, appeared in Paris in April 1828, it immediately attracted popular writers and artists interested in the study of contemporary everyday life. It served as a perfect social laboratory, a microcosm of society and the tensions that agitated it.  The omnibus (“for all” in Latin ) was unique for its time because it was by law open to anyone regardless of class or sex. This inclusiveness created new forms of urban sociability, as men and women of different social classes mixed and mingled and rubbed shoulders within the narrow confines of the vehicle. Scores of texts such as press articles, pamphlets, city guides, short stories, vaudevilles, poems, society board games, caricatures, songs, and even a piano sonata seized upon the omnibus as their subject of choice through which to tackle hot topics of the day.

The omnibus (“for all” in Latin ) was unique for its time because it was by law open to anyone regardless of class or sex. This inclusiveness created new forms of urban sociability, as men and women of different social classes mixed and mingled and rubbed shoulders within the narrow confines of the vehicle. Scores of texts such as press articles, pamphlets, city guides, short stories, vaudevilles, poems, society board games, caricatures, songs, and even a piano sonata seized upon the omnibus as their subject of choice through which to tackle hot topics of the day.

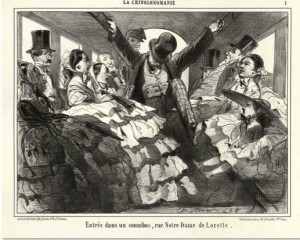

And so, just as manspreading taps into our own cultural anxieties about gender privilege, nineteenth-century writers and artists used the omnibus to express their worries about class, gender, and comportment in public spaces. Predictably, however, these writers did so not to lay bare and correct the abuses of male gender privilege, but rather to protect this privilege from women encroaching upon it.

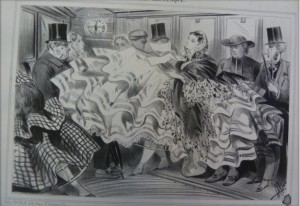

Consider this image from 1859, featuring Madame Crinoliska, a protagonist from a series of caricatures called Paris Grotesque . The series satirizes the fashion of wearing enormous hoop skirts that began in the mid-1850s and lasted into the 1860s. In this image, Mme Crinoliska, a woman of easy virtue, literally invades the omnibus (and the page!), overwhelming her fellow passengers with lacy layers of her outrageously large skirt. Everything about Madame Crinoliska – her tiered skirts, the wide flowing ribbon and enormous bow of her bonnet, her fur-trimmed shawl nonchalantly draped over her shoulders- suggests ostentation, excess, and conspicuous consumption. At the same time, Madame Crinoliska herself is an object to be consumed, visually and otherwise; she is a spectacle on display, entering the omnibus (“faisant son entrée”) as if on a theater stage. From the get-go the attacks against “crinolinomania” took on distinctly gendered tones. And Madame Crinoliska is an excellent illustration of this, a woman literally identified with (or even displaced by) her huge skirt.

Consider this image from 1859, featuring Madame Crinoliska, a protagonist from a series of caricatures called Paris Grotesque . The series satirizes the fashion of wearing enormous hoop skirts that began in the mid-1850s and lasted into the 1860s. In this image, Mme Crinoliska, a woman of easy virtue, literally invades the omnibus (and the page!), overwhelming her fellow passengers with lacy layers of her outrageously large skirt. Everything about Madame Crinoliska – her tiered skirts, the wide flowing ribbon and enormous bow of her bonnet, her fur-trimmed shawl nonchalantly draped over her shoulders- suggests ostentation, excess, and conspicuous consumption. At the same time, Madame Crinoliska herself is an object to be consumed, visually and otherwise; she is a spectacle on display, entering the omnibus (“faisant son entrée”) as if on a theater stage. From the get-go the attacks against “crinolinomania” took on distinctly gendered tones. And Madame Crinoliska is an excellent illustration of this, a woman literally identified with (or even displaced by) her huge skirt.

Why, we may wonder, such vitriol? In the first place, crinolines were a health hazard. They frequently caught fire and killed their wearers. In fact, this is how Madame Crinoliska herself perishes in another image, consumed by flames she sets off by igniting the hearts of her admirers. But the main reason for this contempt was because of the crinoline’s excessive girth. Women in crinolines simply took up too much room, crowding men out of public space, sometimes eclipsing them altogether. As we see in this image, several male passengers, including a priest and three respectable bourgeois men are virtually engulfed by the voluminous ruffles of the skirts. Crinolines and crinoline wearers represented excess, and their exaggerated physical presence flew in the face of rules of propriety and proper behavior that called for women to know their place (i.e. to take as little of it as possible), and threatened their male counterparts through its sheer scale.

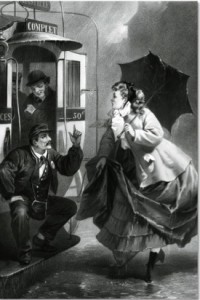

But that wasn’t the only thing that vexed nineteenth-century observers about Mme Crinoliska and her ilk. Another big worry was the risk of finding yourself, or even worse, your wife or sister, sharing a seat with a prostitute. Texts and images suggest that public transport was an ideal place for ladies of the night to solicit clients.  In one image, for example, we see a courtesan – “une poule,” (in French, “chicken” but also “tart”) who attempts to board the omnibus but is turned down by a virtuous conductor, the guardian of moral order.

In one image, for example, we see a courtesan – “une poule,” (in French, “chicken” but also “tart”) who attempts to board the omnibus but is turned down by a virtuous conductor, the guardian of moral order.

Even more troublesome, how was one supposed to distinguish a loose woman from a proper lady at a time when sartorial differences between them were becoming increasingly blurred? Journalist Edouard Gourdon, in Physiologie de l’omnibus (1842), bemoaned the difficulty in establishing a female passenger’s moral and social standing based on her dress: “Nowadays the proper lady’s silk dress, cashmere shawl and hat come from the same boutique where the prostitute shops, and the two share the same jeweler.” In the case of Madame Crinoliska, what identifies her as a cocotte is not so much the crinoline itself, but rather the outrageous way that she carries herself, scandalously displaying her dainty legs and even a bit of the cage, and spreading her skirts everywhere, like a visual metaphor for the venal contagion she represents.

Just as today’s indictment of “manspreading” recognizes public transit as a space of social confrontation, the omnibus in nineteenth-century Paris brought into focus the contest about women’s place in public urban spaces, and by extension, in society.

Masha Belenky is Associate Professor of French at the George Washington University. Author of The Anxiety of Dispossession: Jealousy in Nineteenth-Century French Culture (Bucknell 2008), she is currently working on a book about public transit and popular culture in nineteenth-century Paris.

For further reading:

On crinolines in nineteenth-century culture, see Linda Nead, “The Layering of Pleasure: Women, Fashionable Dress and Visual Culture in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” in Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 35:5 (2013): 489-509.

On fashion accessories as marker of class distinction, see Susan Hiner, Accessories to Modernity: Fashion and the Feminine in Nineteenth-Century France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010).

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.