Holly Tucker's Blog, page 9

November 30, 2016

Nursery Terrors

by Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

One of the more elusive bogeymen is Rawhead and Bloody Bones. The Oxford English Dictionary notes references to this monster dating from the mid-sixteenth century and the tale was widespread enough to be imported to the United States, but actual early stories about Rawhead and Bloody Bones are scant on the ground. Rather, his name is more likely to be used as a warning: ‘Keep away from the marl-pit or Rawhead and bloody bones will have you!’ Although he was associated with pools of water, he might also be found living in cupboards or under stairs, sat upon the bones of naughty children. But the whys and wherefores of his determination to punish children is unclear.

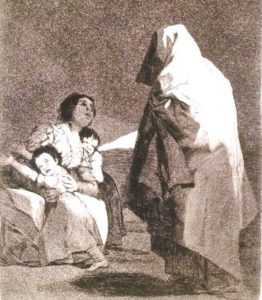

Here Comes the Bogeyman, Francisco Goya. Credit: Brooklyn Museum, Wikimedia Commons.

Rawhead was also a creature lurking in the nursery—a terrifying assistant to the busy mother or nursemaid for keeping children under control. As John Locke put it in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693):

This he will be in danger of from the Indiscretion of Servants, whose usual Method is to awe Children, and keep them in subjection, by telling them of Raw-head and Bloody-bones, and such other Names as carry with them the Ideas of something terrible and hurtful, which they have Reason to be afraid of when alone, especially in the Dark. This must be carefully prevented: For though by this foolish way, they may keep them from little Faults, yet the Remedy is much worse than the Disease.

(Dolly Parton has a charming account of her own mother’s invocation of Rawhead and Bloody Bones when trying to put twelve children to bed, which is well worth a listen.)

By the late seventeenth century, people were beginning to question the wisdom of relying on stories about bogeymen. The real problem, of course, wasn’t scaring small children – but its long-term damage, particularly when it came to training the men of the future. Locke noted that the minds of the young were impressionable and such fancies ‘frequently haunt them with strange Visions, making Children Dastards when alone, and afraid of their Shadows and Darkness all their Lives after’ (138).

He provided a cautionary true tale, beginning (oddly enough) in a fairy-tale fashion: ‘There was in a Town in the West a Man of a disturbed Brain, whom the Boys used to teaze when he came in their way’. One day, the man seized a sword from a nearby cutler’s shop and chased a boy. The boy escaped—just—to his house, and as he was about to turn the latch, he chanced to look behind ‘to see how near his Pursuer was, who was at the Entrance of the Porch, with his Sword up ready to strike; and he had just Time to get in, and clap to the Door to avoid the Blow, which, though his Body escaped, his Mind did not’ (139). The boy was haunted into adulthood by the memory, always having to check behind him when going in that door.

Dialogues on the passions, habits, and affections peculiar to children by James Forrester (1748) was much more specific about the damage, which Forrester blamed on nurses, mothers and grandmothers. Forrester mused that ‘something of Raw-head and Bloody-bones occurs to you as often as you look into a dark unfrequented Corner of a Church’, which came from ‘some Remains of the Nursery, some Remnants of Fear, and that Idea of Dread, which, Thanks to our Mothers and Grandmothers, is constantly connected with Churches, Church-years, and Charnel-houses’ (27).

The first stage of fear, connected to self-preservation, began before the age of five. Carers could use:

the Appearance of Objects, capable of giving them Pain; Objects, with the Idea of Pain, connected with them by the Imagination, such as Raw-head and Bloody-bones, &c. &c. Objects, that are new to them, with the Idea of Danger connected to them, and sudden Surprizes, which in Young and Old always create some Degree of Terror, but in Children more especially (33).

The second stage of fear was nurtured by the stories of women who ‘have strong Faith in Spirits, Apparitions, and Witches, love to hear and repeat Stories of that Kind’ (35). In this way, the children’s imaginations were trained to connect mischievous spirits with horror and dark places. The third stage of fear was connected to punishment. As the nursemaid switched from relying on the threats of bogeymen to using actual corporal punishment to ensure good behaviour, the child blurred the boundaries between the types of punishment in his own mind. And this was most dangerous of all, according to Forrester:

If the Spirit is kept long in this Subjection, Timidity becomes a Habit, and nothing afterwards can persuade it to look at the most visible Terror, and all he Marks of Cowardice, which is the lowest and must abject State, to which a rational Creature can be reduced (37).

The whys and wherefores of Rawhead and Bloody Bones’ punishment apparently didn’t need explanation, since the real terror of the nursery–for the Enlightened male–was the long-term effects masculine rationality, perpetuated by the wild imaginations of women and servants.

I leave you with ‘Rawhead and Bloodybones’ by Siouxsie and the Banshees, mashed up with a video clip from Jan Svankmajer’s “Neco z Alenky” (Alice)–which together evokes the terrors of the nursery and the suspension of rationality.

November 28, 2016

How Desert Caravans Crossed the Sahara

By Pamela D. Toler (Regular Contributor)

In the eighth century CE, after camels were introduced into North Africa, Muslim merchants of North Africa began to organize regular camel caravans across the western Sahara. North African merchants carried luxury goods from across the Islamic world and salt purchased from the desert salt mines to the great trading cities of the Sudan: Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenne. (They also carried Islamic theology and learning, but that’s another story.) They traded for gold and slaves, and to a lesser degree tropical products such as ostrich feathers, ivory and kola nuts. Both sides benefited from the trade. At times a North African merchant could sell his salt for an equivalent weight in gold. According to fourteenth century Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun, by the twelfth century caravans as large as 12,000 camels crossed the desert each year.

In the eighth century CE, after camels were introduced into North Africa, Muslim merchants of North Africa began to organize regular camel caravans across the western Sahara. North African merchants carried luxury goods from across the Islamic world and salt purchased from the desert salt mines to the great trading cities of the Sudan: Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenne. (They also carried Islamic theology and learning, but that’s another story.) They traded for gold and slaves, and to a lesser degree tropical products such as ostrich feathers, ivory and kola nuts. Both sides benefited from the trade. At times a North African merchant could sell his salt for an equivalent weight in gold. According to fourteenth century Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun, by the twelfth century caravans as large as 12,000 camels crossed the desert each year.

It was a dangerous three-month journey along routes that was little more than a string of oases separated by long stretches of featureless desert. But how did it work?

Caravans were temporary associations of merchants who joined together to make the difficult journey under the leadership of a hired caravan leader using camels rented from the nomadic bedouins who lived in the desert. They often included one thousand to five thousand camels and hundreds of people. Typically, a third of the camels carried food and water for the caravan as a whole.

The success of a caravan dependent on the caravan leader, who was typically a desert bedouin. Paid either in cash or as shares of the merchants’ profit, a caravan leader was responsible for navigating the route from watering place to watering place, managing relationships with the desert population–who could quickly turn from service providers to marauders–and supervise the daily work of loading, unloading, and feeding the camels. He had a paid team of laborers, scouts, healers and occasionally a Muslim clergyman to provide services, all generally members of the same bedouin tribe as the leader.

Oases were the critical element. They were resting places where the caravan could find food, water, and fresh camels–the medieval equivalent of the truck stop. Some of the larger oases held regular markets during the caravan season, which typically ran from October to March in order to avoid the worst heat. The failure of a caravan to reach an oasis could mean disaster not only to the caravan but to those who lived at the oasis and depended on the trans-Saharan trade for their survival.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

November 22, 2016

How a Mosquito Defeated Napoleon – and Freed Haiti

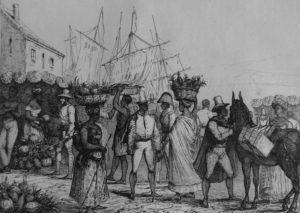

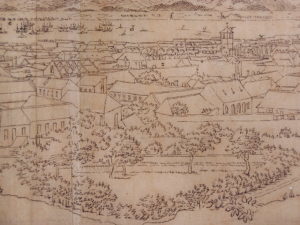

Street scene in colonial Haiti

by Philippe Girard (Guest Contributor)

Early in 1758, François Makandal stood before the church of Cap-Français, the main French town in what is today Haiti. Bearing a sign that read “Seducer, Blasphemer, Poisoner,” he was ordered to publicly confess his crimes. They included a poisoning conspiracy that had allegedly cost the lives of thousands of planters and slaves. This was a serious charge in a colony that was the most prosperous in the New World, and where hundreds of plantations produced the bulk of Europe’s sugar and coffee. Makandal’s sentence: to be burnt alive.

Executions were meant as teaching moments for the general public, so many people, both free and enslaved, gathered on the plaza in front of the church. Makandal, whose name roughly translates as “sorcerer,” claimed magical powers such as the ability to transform himself into a mosquito. As he was tied to a stake, everyone present wondered who would prevail on that day—French justice or the occult powers of Vodou.

View of Cap-Français. Makandal was executed in front of the Church.

As the flames engulfed him, Makandal fought and struggled… until he freed himself. All the slaves gasped “Makandal sauvé”! “Makandal is free!” Fearing a riot, authorities evacuated the plaza. They then tied Makandal and threw him back onto the pyre, but the public did not witness his death and a rumor soon spread among the slaves of the colony that Makandal had become a mosquito and flown away from the execution site unscathed. One day, they thought, Makandal would return to exact his revenge and free the slaves of Haiti.

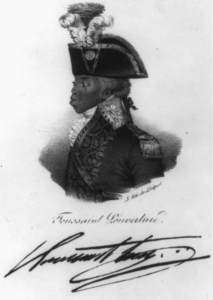

Portrait of Haitian revolution leader Toussaint Louverture by Nicolas Maurin (1832).

It is easy to dismiss such belief as artefacts from a pre-scientific age governed by superstition. But two decades later, in 1791, the slaves of Haiti did revolt against their masters. The uprising involved 500,000 slaves, one thousand times more than the largest slave revolt in US history. Amazingly, they prevailed.

Many factors contributed to the success of the Haitian slave revolt, the only successful slave revolt in the history of the world. The rebels’ courage and dedication evidently played a role. So did the extraordinary skills of their leader Toussaint Louverture, the “black Napoleon.” It was under his leadership that the slaves of Haiti repelled invasions by Spain and Britain, then a massive expedition led by Napoléon’s own brother-in-law, and eventually secured the independence of Haiti in 1804.

But equally important were successive outbreaks of yellow fever that decimated the armies sent to quell the Haitian slave revolt. One by one, European expeditionary forces were dispatched to Haiti, only to melt away as yellow fever took its toll. This was a dramatic example of the phenomenon described by William McNeill in Plagues and Peoples: history is shaped by great individuals like Toussaint Louverture, but also by natural forces like disease.

Yellow fever, we now kno w, is a virus transmitted by a mosquito, the Aedes aegypti. Maybe Makandal survived his execution after all.

w, is a virus transmitted by a mosquito, the Aedes aegypti. Maybe Makandal survived his execution after all.

Philippe Girard is a Professor of Caribbean History at McNeese State University and the author of Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life (Basic Books, November 2016) © Philippe Girard 2016.

November 21, 2016

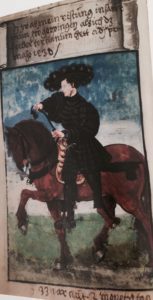

Fashions for Work, Play, and Travel: A Renaissance Accountant Writes His Life in Clothes

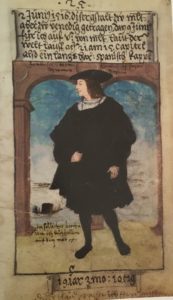

“Today, 20th February, 1520, I, Matheus Schwartz of Augsburg, was just 23 years old and looked as above.”

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

One of the most remarkable books of fashion ever produced is an illustrated manuscript, created by a German accountant born in 1497. At the age of 23 he decided to document his life in clothes. Over the next 40 years he had 137 images of himself painted for inclusion in his pictorial autobiography. We see him working at his desk, preparing for a voyage, “flirting in the streets,” attending a funeral. Accompanying each portrait in this work that he called his “Book of Clothes” is a careful description of the style, fabric, and design of his outfit.

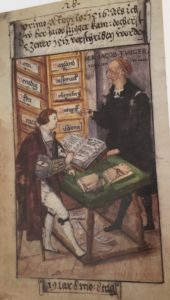

Matthäu s Schwarz was inspired in his project by a lively interest in fashion which he saw as rapidly changing in this period of increased travel and international trade. He himself loved to travel and embraced the business assignments that took him away from Augsburg. As head accountant for the powerful Fugger family of merchants, he developed a keen appreciation of the luxury fabrics that were traded along with other precious items through the firm of Jakob Fugger.

s Schwarz was inspired in his project by a lively interest in fashion which he saw as rapidly changing in this period of increased travel and international trade. He himself loved to travel and embraced the business assignments that took him away from Augsburg. As head accountant for the powerful Fugger family of merchants, he developed a keen appreciation of the luxury fabrics that were traded along with other precious items through the firm of Jakob Fugger.

As a child Matthäus dreamed of adventure and travel. In one of the illustrations in his book that reflect on his youth, he shows himself discarding his schoolbooks and yearning to enter the distant landscape. The caption reads: “At the end of 1510, I threw away my school bag. My desire was to see foreign lands, and I liked to be dressed in this way.”

His wishes were granted when he was sent to Italy to learn accounting. Fashionable attire was essential for him to be able to project his status. But his fondness for expensive fabrics did not always work out so well. In one image he is wearing a French outfit that was stolen from him while in Milan. Moving on to Venice, he dressed a bit more soberly, all in black.

To mark the beginning of his brilliant career, Matthäus had himself painted at his new desk, with his work smock hanging loosely open, revealing a ruffled shirt and a doublet with slashed sleeves, yellow inner fabric, and black velvet ties. The portrait shows off his new connections to the world, via the drawers for correspondence with cities such as Milan, Rome, Lisbon, and Venice.

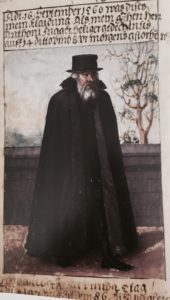

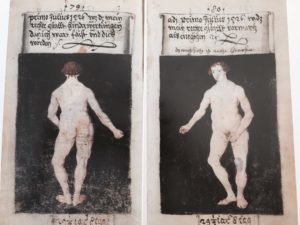

But the most startling illustration in the ‘Book of Clothes’ is one that he commissioned at age 29, when, as he puts it, “I had become fat and round.” It is the only illustration showing him from both front and back. It is not idealized. It is as though he wanted to include one image in the book that would show his body as it really was, stripped of the beautiful illusion that fashionable clothing could create.

“This was my proper figure from behind, for I had become fat and round, and this was my proper figure from the front on the first of July 1526. The face is well captured.”

An English translation of The Book of Clothes was published in 2015 as The First Book of Fashion, edited by Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward.

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin (Public Affairs Books, 2012). She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

November 15, 2016

A House Built from a B-29 Bomber

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

The United States was in the midst of a severe housing shortage in 1946 when Roy Rasmussen, a Marine Corps veteran, spotted a section of a B-29 bomber airplane sitting in a scrap metal yard in Omaha, Nebraska. Along with his wife, Evelyn, and two-year-old son, Roy Jr., Rasmussen needed an affordable place to live while he was taking classes at the University of Minnesota, so he bought the 20-foot-long hunk for $130 and towed it up to Minneapolis.

A B-29 Superfortress in flight

Over the next several weeks, Rasmussen fixed up the fuselage—formerly the portion of the airplane that housed the crew and radio section— and installed a cooking range, stove, sink, closet, fold-down tables, and a davenport that doubled as the couple’s bed.

“One day I saw this thing coming down the street,” recalled Charles Amble, the owner of a service station at the corner of Eighteenth and East Hennepin Avenue in Minneapolis. “The man pulling it said he was looking for a place to park it. I thought it was kind of a novelty, so I said he could park it next to my station.”

For the next year, the Rasmussens lived in the bomber on Amble’s property. They used the service station’s bathroom, and Roy Jr. played in back of the airplane in a sandbox made from a bubble window of the fuselage. Evelyn Rasmussen did not recall whether the home received much attention from her neighbors. “It was located in the back and under a tree, so I don’t think too many people noticed it,” she said.

Soon, however, the Rasmussens sold the bomber to another couple, Galen and Elayne Armstrong. Elayne remembered that she and her husband frequently hosted parties there, watched the trains pass on the nearby tracks, and “loved the view of the bubble where the gunner was [and where we] could lay in bed and look at the stars.” After about seven years, the Armstrongs sold the home to a Mr. Lewis, who, Elayne believed, moved the bomber about 90 miles north to a location near Lake Mille Lacs.

Roy Rasmussen’s strange living space had at least temporarily saved the day. “I thought it was wonderful that he thought of it, and there was no place else left to live,” said Evelyn Rasmussen.

This is an excerpt from Jack El-Hai’s book Lost Minnesota: Stories of Vanished Places (University of Minnesota Press).

November 11, 2016

Little Chefs

By Michael Garval (Regular Contributor)

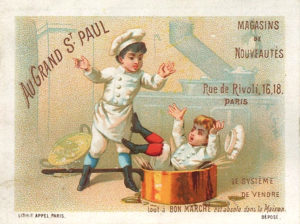

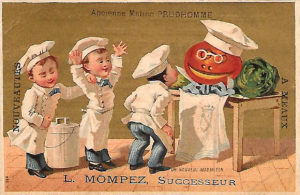

Au Grand St. Paul, chromolithographic trade card, c. 1880.

“Little chef.” In the 2007 animated film Ratatouille, this is what bungling culinary neophyte Alfredo Linguini calls his sidekick and alter ego, the talented rat Remy. But “little chefs”—impish kitchen apprentices or, in French, marmitons—are no Disney Pixar invention. They were already fixtures in nineteenth-century French culture, linked in the popular imagination to the rise of the celebrity chef.

Apprentice celebrities

After millennia of cooks toiling in relative obscurity, as domestic help, celebrity chefs burst on the scene in post-revolutionary France, most notably with the great Antonin Carême (1784-1833). Musing and mythmaking abounded, as contemporaries puzzled over the origins of such a novel public figure. By the latter nineteenth century there had emerged an extensive mythology of the marmiton. Illustrated menus, prints, postcards, popular theater, biography, and children’s literature imagine the lowly scullion’s magical transformation into an accomplished culinarian—an individual metamorphosis mirroring the broader, but also seemingly miraculous advent of the celebrity chef. Marmiton mythology draws likewise upon the rich, deep-rooted lore of culinary sorcery, to offer a fanciful yet compelling vision of the celebrity chef’s extraordinary new place in the public sphere.

Little marmitons making mischief, detail from illustrated menu for Restaurant de l’Âne Rouge, August 6, 1916.

Fairy tale logic

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, chefs were overwhelmingly male and adult, while underrepresented as such in popular culture. Instead, comical chef figures abound, particularly mischievous boys or even infants—marmitons or yet more implausible petits marmitons, their iconography closely linked to the retrograde revival of cherubic putti in nineteenth-century academic art. Such ill-qualified chefs typically appear clumsy, foolish, irresponsible, spilling food, swilling drink, burning sauces, chasing uncooperative fowl, getting assaulted by lobsters.

La sauce est brûlée (“The sauce is burnt”), postcard, 1902.

Such fantasies of culinary disaster proliferated while French kitchens were producing elaborate feasts, in a gastronomic golden age, with French culinary prowess a pillar of national pride and international prestige. How might we reconcile this seeming contradiction between the spectacular ineptness of so many little chefs and the triumph of French gastronomy? How might we sort out the paradox of the marmiton?

Not yet a chef, the marmiton is a potential chef. In marmiton mythology, fairy tale logic reigns. Little apprentices, however hapless, could become great chefs, just as a humble stepsister could become a princess; a frog, a prince; or, a pumpkin, a carriage. Within this fairy tale logic, the lowlier the beginnings, the loftier the outcome, the more wondrous the transformation. The marmiton provides the necessary antithesis and anticipation of the great chef, his opposite and origin.

Magical marmitons

How to represent the little apprentice’s metamorphosis? Most often it is not depicted, with otherworldly occurrences excluded from this world, like violence relegated offstage in classical theater. But some rare, revealing works try to show such a change.

A “nouveau marmiton” envisioning his future, chromolithographic trade card, c. 1890.

In one chromolithographic trade card, two marmitons play a practical joke on their newest peer, assembling an adult chef effigy out of spare kitchen paraphernalia, including that most enchanted vegetable, the pumpkin. Like us, they look on as the “nouveau marmiton” meets his would-be boss. The boy gazes at the pumpkin-headed chef he might become, as if facing a prophetic mirror. He glimpses his future, a vision of potential, magical transformation.

In a curious 1904 children’s book, later surrealist poet and painter Max Jacob offers us le Marmiton Gauwain, a royal kitchen apprentice in a fictional kingdom resembling Provence. In this culinary fairy tale, food is always magical, starting with Gauwain’s first exploit: a white powder concocted from anise, sugar, orange, acid, and Hungarian wild thyme, sprinkled over a cake, creates an extraordinary taste, alerting the king to his talents. Later, “alchemical” substances make water boil, and Gauwain prepares a feast overflowing with wondrous fare—Egyptian mongooses, or Brazilian yams garnished with internally illuminated ice.

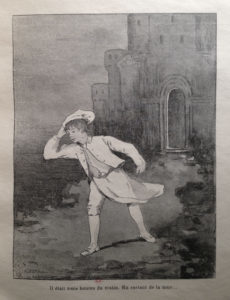

L. Saint, illustration for Max Jacob, Histoire du Roi Kaboul Ier et du Marmiton Gauwain, 1904.

His professional ascent astonishingly quick, Gauwain prevails at sixteen:

Gauwain worked, worked, worked, so so much, so so much, that he knew all the recipes by heart and invented some more, so that he was the best cook in the world.

The incantatory repetition of “worked” and “so so much,” like the improbable speed of his apotheosis, make Gauwain’s success seem less the result of hard work than of magic.

Behind the fanciful figure of le Marmiton Gauwain looms the spectre of Auguste Escoffier, the period’s premier celebrity chef. While Jacob’s tale never mentions him explicitly, it was published in 1904, a year after Escoffier’s epoch-making Guide culinaire, when he was seen more than ever as the paragon of culinary authority. Much in Gauwain’s story recalls Escoffier, and evokes key aspects of the regional, national, and international contexts surrounding his ascendance: meridional origins and a blacksmith father, a gift for hobnobbing with social superiors, profitable collaboration with an enterprising hotelier (in Escoffier’s case César Ritz), sparkling success in a once hostile kingdom (for Escoffier England), and ultimate reconciliation between hereditary enemies (like Jacob’s book, the Franco-British Entente Cordiale dates from 1904).

Gauwain’s meteoric rise, his magical metamorphosis from apprentice to “best cook in the world,” then conqueror and king, offers a mock-heroic allegory, a parodic fairytale rendering of Escoffier’s remarkable career, impact, and international ambition. A century after Carême’s First Empire stardom, the apotheosis of the celebrity chef remained so astonishing that it was imagined, not as the result of exceptional achievement, but rather as a supernatural transformation.

Latter-day marmitons

Marmiton lore still haunts popular culture, on the big and small screen. In Ratatouille, the marmiton role splits in two. Linguini displays the apprentice’s conventional incompetence, while Remy taps into the deep magic of marmiton mythology. This little rat’s improbable triumph takes him from the lowest places to the loftiest heights—visually, from sewers to rooftops—as he becomes the greatest chef in Paris and by extension in the world, like Gauwain or his real-world analogue Escoffier.

Latter-day marmitons surface as well on television, notably in the cooking competition show MasterChef Junior, an international phenomenon, with versions broadcast from Brazil to France, Indonesia to Vietnam. The show’s name conflates youth and mastery, and likewise young contestants seem preternaturally skillful from the start. Maybe this radical foreshortening of the path to culinary stardom stems from our modern penchant for instant outcomes, and maybe also from a newfound comfort with fame in the kitchen. Perhaps becoming a celebrity chef is such a familiar thing these days, attaining this exceptional status now so unexceptional, that even a child could do it.

Michael Garval , Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

, Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

Letters of a Madman?

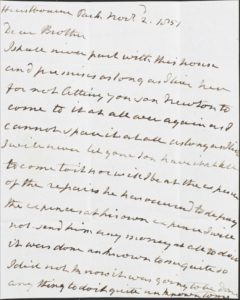

“I shall never part with this house” Portsmouth’s heartfelt letter to his brother

(Oneworld Publications)

By Elizabeth Foyster (Guest Contributor)

My book started with a tip-off. It was July 2000 and I was working in one of my favourite places, Lambeth Palace Library in London, on a book about marital violence. Surrounded by theologians, who I am sure were researching worthier things, I was ploughing through the depressing stories of couples whose violent marriages were ended by the English church courts during the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I was looking for an excuse for a break. Then Melanie Barber, the Senior Archivist, entered the room. I had liked Melanie ever since I had first visited the Library as a naïve PhD student, and she had responded to my many queries with patience and kindness. As was Melanie’s way, she walked around the room, asking each person what they were reading, and taking an interest in their work. Then it was my turn. “You should take a look at the Portsmouth annulment case,” she told me. “There are boxes of material and nobody has ever looked at them before.”

I still have the pencil note of this conversation, and the case reference number, but a combination of work and family commitments meant that it was a long time before I opened those boxes. To my great regret, I never got to thank Melanie for her generous advice, as she died in 2012. I hope she would think I have done the archive justice.

“No More Insane Than Any Other Person Going to Be Married”

The boxes at Lambeth are a treasure trove. Never before had I come across such a volume of words and outpouring of emotion about a historical figure. The annulment case had been called to decide whether the 3rd Earl of Portsmouth had been insane when he married his 2nd wife on 7 March 1814. Doctors gave their opinions, but couldn’t agree, and the case came to rest on the views of very humble people who otherwise would have disappeared from history. Portsmouth’s servants and farm labourers, as well as the villagers who lived close to his Hampshire estate, were given a platform to speak. Over a hundred witnesses came forward, and it seemed as if in the 1820s everyone had an opinion about Lord Portsmouth, but I had never heard of him. Why had his story laid buried in the archives for so long?

“Hurstborne Park” Portsmouth’s home

The annulment case got me hooked, but it turned out to be just the last of the legal trials that Portsmouth faced. When I traced his story back, I discovered lawyers’ notes relating to a first call for a Lunacy Commission in 1815, and printed accounts of an 1823 Lunacy Commission. Reading through these records I discovered that Portsmouth had been tutored as a boy by the father of Jane Austen at his rectory in Steventon, and that Jane attended balls at his Hampshire home. Lord Byron was a witness to Portsmouth’s second marriage, and was adamant that Portsmouth was no “more insane than any other person going to be married.”

In On the Secret

It is all very well reading the notes taken by legal clerks, but for me, nothing beats handling and folding open letters that were exchanged between family members. These are sources that were never intended to be read by anyone but the recipient. Here I struck lucky again, because the Portsmouth family kept up a huge correspondence. It turned out that Portsmouth was not the only member of his family with mental problems. An aunt and two of his cousins were locked away in madhouses, but the family were so adept at keeping secrets that these facts were never revealed in Portsmouth’s trials. I was in on the secret.

on the secret.

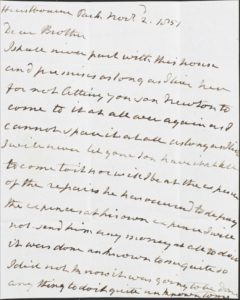

I made one more discovery that was tucked away in these family papers: letters written by Lord Portsmouth himself. I spent so long reading about Portsmouth via the words of others, that it was wonderful to come across his words, in his handwriting. I didn’t have a portrait of him (one was never commissioned), so this was the closest personal thing I had. This small group of letters was written by Portsmouth when he was in his early 80’s (he died in his eighty-sixth year). After all the years of legal trials, and the many stories that had been told about his eccentric and sometimes disturbing behaviour, his letters were not what I’d expected. Clearly written, all they lacked was punctuation. They defended his right to continue living in Hurstbourne Park, a perfectly reasonable request since this was his lifelong home. And to me they did not look or read like the letters of a madman. Why, then, had Portsmouth’s sanity been so publicly questioned?

Bringing together all these stories from the archives, I’ve presented the case of Lord Portsmouth in my book, The Trials of the King of Hampshire: Madness, Secrecy and Betrayal in Georgian England (Oneworld). I invite you to join the jury at the Lunacy Commission, and decide the truth about this extraordinary man.

Elizabeth Foyster is a Fellow and Senior College Lecturer at Clare College, Cambridge. She explores the sort of subjects that are often left out of the history books – childhood, married life, sex, relationships with siblings and parents, masculinity, old age and widowhood. She lives in London.

Letters of a madman?

“I shall never part with this house” Portsmouth’s heartfelt letter to his brother

(Oneworld Publications)

By Elizabeth Foyster (Guest Contributor)

My book started with a tip-off. It was July 2000 and I was working in one of my favourite places, Lambeth Palace Library in London, on a book about marital violence. Surrounded by theologians, who I am sure were researching worthier things, I was ploughing through the depressing stories of couples whose violent marriages were ended by the English church courts during the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I was looking for an excuse for a break. Then Melanie Barber, the Senior Archivist, entered the room. I had liked Melanie ever since I had first visited the Library as a naïve PhD student, and she had responded to my many queries with patience and kindness. As was Melanie’s way, she walked around the room, asking each person what they were reading, and taking an interest in their work. Then it was my turn. “You should take a look at the Portsmouth annulment case,” she told me. “There are boxes of material and nobody has ever looked at them before.”

I still have the pencil note of this conversation, and the case reference number, but a combination of work and family commitments meant that it was a long time before I opened those boxes. To my great regret, I never got to thank Melanie for her generous advice, as she died in 2012. I hope she would think I have done the archive justice.

“No More Insane Than Any Other Person Going to Be Married”

The boxes at Lambeth are a treasure trove. Never before had I come across such a volume of words and outpouring of emotion about a historical figure. The annulment case had been called to decide whether the 3rd Earl of Portsmouth had been insane when he married his 2nd wife on 7 March 1814. Doctors gave their opinions, but couldn’t agree, and the case came to rest on the views of very humble people who otherwise would have disappeared from history. Portsmouth’s servants and farm labourers, as well as the villagers who lived close to his Hampshire estate, were given a platform to speak. Over a hundred witnesses came forward, and it seemed as if in the 1820s everyone had an opinion about Lord Portsmouth, but I had never heard of him. Why had his story laid buried in the archives for so long?

“Hurstborne Park” Portsmouth’s home

The annulment case got me hooked, but it turned out to be just the last of the legal trials that Portsmouth faced. When I traced his story back, I discovered lawyers’ notes relating to a first call for a Lunacy Commission in 1815, and printed accounts of an 1823 Lunacy Commission. Reading through these records I discovered that Portsmouth had been tutored as a boy by the father of Jane Austen at his rectory in Steventon, and that Jane attended balls at his Hampshire home. Lord Byron was a witness to Portsmouth’s second marriage, and was adamant that Portsmouth was no “more insane than any other person going to be married.”

In On the Secret

It is all very well reading the notes taken by legal clerks, but for me, nothing beats handling and folding open letters that were exchanged between family members. These are sources that were never intended to be read by anyone but the recipient. Here I struck lucky again, because the Portsmouth family kept up a huge correspondence. It turned out that Portsmouth was not the only member of his family with mental problems. An aunt and two of his cousins were locked away in madhouses, but the family were so adept at keeping secrets that these facts were never revealed in Portsmouth’s trials. I was in on the secret.

on the secret.

I made one more discovery that was tucked away in these family papers: letters written by Lord Portsmouth himself. I spent so long reading about Portsmouth via the words of others, that it was wonderful to come across his words, in his handwriting. I didn’t have a portrait of him (one was never commissioned), so this was the closest personal thing I had. This small group of letters was written by Portsmouth when he was in his early 80’s (he died in his eighty-sixth year). After all the years of legal trials, and the many stories that had been told about his eccentric and sometimes disturbing behaviour, his letters were not what I’d expected. Clearly written, all they lacked was punctuation. They defended his right to continue living in Hurstbourne Park, a perfectly reasonable request since this was his lifelong home. And to me they did not look or read like the letters of a madman. Why, then, had Portsmouth’s sanity been so publicly questioned?

Bringing together all these stories from the archives, I’ve presented the case of Lord Portsmouth in my book, The Trials of the King of Hampshire: Madness, Secrecy and Betrayal in Georgian England (Oneworld). I invite you to join the jury at the Lunacy Commission, and decide the truth about this extraordinary man.

Elizabeth Foyster is a Fellow and Senior College Lecturer at Clare College, Cambridge. She explores the sort of subjects that are often left out of the history books – childhood, married life, sex, relationships with siblings and parents, masculinity, old age and widowhood. She lives in London.

November 10, 2016

Yellow Fever

By Flora Fraser (Guest Contributor)

I’m not normally one to pursue the “What if’s” of counterfactual history. Recently, however, I’ve been indulging wild thoughts about the yellow fever epidemic that afflicted Philadelphia in the summer of 1793, at the outset of Washington’s second term of office. I blame Designated Survivor on Netflix, which I’ve been watching. A Secretary of Housing is sworn in as President, after he escapes a bomb at the Capitol that kills the rest of the government . What if, in 1793, the deadly epidemic had killed off Washington and all his Cabinet, bar one? A Netflix series for someone other than me to make about President Hamilton or Knox or Randolph … Ultimately, I’m always more interested in fact than fiction.

The trials of a young republic

In 1793 Philadelphia was the seat of government, and the republic, still young. Anti-federalists condemned the President’s insistence on American neutrality, after France declared war on Britain. They criticized the stately receptions that George and Martha Washington hosted each week at their Market Street home as ‘monarchical’. The President dwelt, in conversation with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, on ‘the extreme wretchedness of his existence’.

And then, in July and August, yellow fever developed in the city. Noone then understood the role of mosquitoes in transmitting the virus. A drought had succeeded heavy spring rains and pockets of standing water abounded where these insects thrived. Washington’s deficiencies on the national and international stage were forgotten in the urgent need to address the chaotic situation. By early September, despite the best efforts of doctors, hundreds were dying.

Physician Benjamin Rush recorded his symptoms. The sweats, he recorded, were ‘so offensive as to oblige me to draw the bedclothes close to my neck, to defend myself from their smell.’ He survived, as did Alexander Hamilton, Treasury Secretary, and his wife, Betsy. Countless others, including numerous Government clerks and the speaker of the Pennsylvania senate, perished. Henry Knox, Secretary for War, recorded in mid-September : ‘the great seat of it [the epidemic] at present seems to be from 2nd to 3rd street, and thence to Walnut Street. Water Street, however, continues sickly.’ By the end of October over four thousand, in a city with a population of 50,000, had died.

The president’s life in danger

Those who could, fled the city early on. The home the Washingtons occupied on Market Street was dangerously close to the streets that Knox named. Indeed, the President’s valet there was to number among the dead. Either or both of the Washingtons might so easily have succumbed to the fever. Martha would not leave for their Virginia home without her husband. On September 9 he was persuaded to go, leaving Knox in charge of a skele ton government. At Mount Vernon a sombre President received reports of the mounting death toll.

ton government. At Mount Vernon a sombre President received reports of the mounting death toll.

Frosts, in late October, rather than medical intervention, brought the epidemic to a halt. Congress, which had prepared to assemble elsewhere in case of need, reconvened in Philadelphia. Slowly life resumed its normal pattern, and the President was soon under attack again from his critics. But everywhere there were reminders of the recent tumultuous months. Martha Washington wrote, on her return to the city, that almost every family had lost some of their friends: ‘black [for mourning] seems to be the general dress of the city.’

The sources of all quotations are to be found in the relevant pages of my book, The Washingtons.

Flora Fraser is author of Beloved Emma: The Life of Emma, Lady Hamilton; The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline; Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III; and Pauline Bonaparte: Venus of Empire. The Washingtons won the George Washington Book Prize. She is chair of the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography, established in 2003 in affectionate memory of her biographer grandmother. She lives in London.

November 7, 2016

The Metallic Ink of Herculaneum Scrolls

By Keith Houston (Guest Contributor)

In January 2015, scientists at the European Radiation Synchrotron Facility in Grenoble, France, announced that they had deciphered handwritten text from a series of papyrus scrolls excavated at the Roman town of Herculaneum by passing X-rays through the scrolls’ carbonized remains. Then, in March this year, another secret was revealed. Those same scrolls were discovered to have been written with distinctive metallic ink, once through to have been invented many hundreds of years later, and which boasted – or rather, whispered of – roots in ancient spycraft.

The Disappearance of Carbon Ink

Since time immemorial Roman scribes had employed a system of hollow reed pens, homemade ink, and papyrus scrolls purchased according to length. The ink in which they dipped their pens was a mixture of water, gum arabic, and soot, just as it had been for the Egyptians and Greeks before them. Gum came from the acacia trees found in Asia Minor to the East; soot, on the other hand, could be scraped off burnt cooking utensils, ground down from cremated elephant bones, or prepared in a purpose-built furnace, depending on the motivation and the means of its maker. It was a simple recipe, and a flawed one: the distinguishing feature of carbon ink was that it could be washed off papyrus scrolls with nothing more than a moistened finger. (Martial, a Roman poet of the first century CE, wrote of sending out his books still wet so that discerning patrons could erase poems not to their liking.)

Sometime during the first century, however, things began to change. As the ERSF researchers discovered, scribes at Herculaneum were using a quite different kind of ink no later than 79 CE, when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius choked the life out of the town – an ink with metallic elements in its make-up that is opaque to X-rays. The days of carbon-based ink were numbered.

A New Medium: Metal Ink

Until now, the received wisdom was that metal-based ink had become popular only during the third or fourth century CE, popularized by Christian scribes who copied and re-copied the Gospels and other important religious works. To make metallic ink, nutlike tree growths called galls were dried, crushed and infused in rainwater, wine, or beer, before being mixed with sulfate of iron or copper. The acidic gall liquor reacted with the metal sulfate as soon as the two were brought together to form an insoluble pigment that fixed itself on the page, and scribes learned to breathe into their ink jars to replace the air with unreactive carbon dioxide before stoppering them. For ancient writers, metallic ink was a quantum leap forward, as permanent on papyrus as it was on the new-fangled parchment becoming popular with scribes as far afield as Gaul and Britannia.

But the irony of metallic ink is that it may well have grown out of a need for subterfuge rather than brazen permanence. In the third century BCE, a Greek engineer named Philo wrote of what he called “sympathetic ink” made from tree galls and copper sulfate, but these familiar ingredients were to be brought together after their message had been written, not before. In Philo’s scheme, a would-be spy or illicit lover wrote on papyrus using a colorless infusion of crushed tree galls; on receipt, their correspondent washed that same papyrus with a solution of copper sulfa te to reveal its hidden message.

te to reveal its hidden message.

Work to decipher the Herculaneum scrolls is still ongoing, and we don’t yet know whether their singular metallic ink is a descendant of Philo’s recipe or something else entirely. But whatever we learn, our understanding of ancient writing practices has already been turned on its head. Metallic ink was used centuries earlier than previously thought, long before Christian monks and scribes turned their hands to it, in a Rome where citizens prayed to household shrines and where the wrath of Vulcan, god of the volcano, was still a thing to be feared.

Keith Houston is the founder of shadycharacters.co.uk. His latest book, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time, is available now from W.W. Norton & Co.