Holly Tucker's Blog, page 7

December 27, 2016

The Role of the chef and how it led to the suicide of Francois Vatel

By Christine Smudde (Guest Contributor)

Francois Vatel was the well-respected chef to the noble Condé family in the late 1600s. The Condés lived at Chantilly, the ancestral home of the prince of Condé. It was a grand chateau and Vatel took pride in the fine cuisine he prepared and served at the table. One year, he was orchestrating a two-day banquet celebrating the visit of King Louis XIV and his entourage at Chantilly. The event was going to be fit to match even the highest French standards for grandeur. There would be elegant food, music, and festivities. The first day was deemed enchanted and the culinary abundance refined and extravagant, even with the unexpected guests. But, disaster struck on the second day, a Friday and, therefore, a day where meals are centered on seafood due to the laws of the Roman Catholic Church. When Vatel learned that there might not be enough seafood to feed the entire royal entourage, he promptly went to his room, propped his sword against the door, and drove it through his heart. He would rather die than disappoint the king and dishonor his culinary art. Some thought this was a logical response for a chef who thought he had failed to give his royal guests the meal he had planned for them. Others tried to pass it off as depression. But, the fact is that Vatel preferred death to culinary humiliation.

In the 17th century, a chef was the name given to any man who ran the kitchen of a noble household. He had the job of food preparation and arrangement as well as the orchestration of grand feasts such as the one Vatel organized for the king. It was the chef’s job to mediate between art and nature by highlighting simplicity, purity, and honesty of flavors in his cuisine while upholding the French standards of extravagant sophistication and elegance. When someone hears the term French cuisine, they know the food will be elegant and sophisticated even to this day. Adhering to this new standard of French culinary art was a way to uphold the honor of France. In French cuisine, there are only exquisite meals that are beautifully and carefully prepared and served.

the name given to any man who ran the kitchen of a noble household. He had the job of food preparation and arrangement as well as the orchestration of grand feasts such as the one Vatel organized for the king. It was the chef’s job to mediate between art and nature by highlighting simplicity, purity, and honesty of flavors in his cuisine while upholding the French standards of extravagant sophistication and elegance. When someone hears the term French cuisine, they know the food will be elegant and sophisticated even to this day. Adhering to this new standard of French culinary art was a way to uphold the honor of France. In French cuisine, there are only exquisite meals that are beautifully and carefully prepared and served.

The rise of French cuisine as a fine dining experience elevated the chef’s status in the 17th century. A chef dictated the standards of taste to his diners by providing them with food. He must exude the luxury and extravagance in his creations that had become French standard. He must be able to disguise food for consumption. In this case, disguise refers to the preparations that transformed leftover food into new dishes for a new day. Due to the desire for extravagance, there was often an over abundance of food on any particular day. Due to the need for novelty and elegance that was common in the 17th century, the preparations of the leftover food must be creative, sophisticated, and undistinguishable from the fresh plates. A chef must maintain the curtain between preparation and consumption that protects his art. Therefore, ingenuity was a celebrated quality in a chef. It allowed for variation in simple recipes that could satisfy even the most delicate of tastes and avoid culinary humiliation. As we learned from Vitel, French chefs didn’t take dishonor very well.

Bibliography

Beauge, Benedict On the idea of novelty in cuisine: A brief historical insight. gastronomy and food science December 2011.

DeJean, Joan. Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour. Free Press. 2006.

Landweber, Julia. “Domesticating the ‘Queen of Beans’: How old regime France learned to love coffee.” Montclair State University.

Davis, Jennifer. “Masters of Disguise: French Cooks between Art and Nature, 1651-1793.” University of California Press. Gastronomica Vol 9 No 1. Winter 2009.

Christine Smudde is a senior at Vanderbilt University majoring in Math and French. She was born and raised in Southern California surrounded by good food and friends. Her passion for food began at a young age when she learned to cook with her mom and grandma. It quickly became an important part of her life and has followed her to college. French food combined her passion for France and food to make a great research project.

The post The Role of the chef and how it led to the suicide of Francois Vatel appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 25, 2016

Santa’s Epidemiology

Massachusetts General Hospital: Bulfinch Building, 1941

By Tegan Kehoe (Guest Contributor)

One of the quirks of being a medical museum is that some of our most interesting stories are ones we are very glad not to be able to tell with artifacts. In 1966 a mysterious outbreak of Salmonella took place at Massachusetts General Hospital. Salmonella is not uncommon, but this particular type, Salmonella cubana, is rare. Some of the patients seemed to have contracted the bacterial infection while at the hospital. David Lang, a pediatrician, was determined to find the cause and stop the spread of the outbreak.

The first five cases were all in the same building, which suggested that there was a common source. However, a few weeks after Lang started investigating, S. cubana infections started showing up in completely different places in the hospital. Lang searched for a common factor. At the time each clinical building at the hospital had its own kitchen, so at first Lang didn’t think to look at the food, but then he learned that there was a special-diet kitchen that served all of the buildings.

From the hospital’s collection: cafeteria spoons.

Pictured are a few items from our collection related to nutrition and food services in the 1960s: two MGH cafeteria spoons and a sample 1960 menu. While almost all of the S. cubana patients had been on special diets at one point or other, rigorous testing determined that the kitchen wasn’t the source of the outbreak.

Lang stumbled on the answer in part because of an MGH tradition: Every December, for a grand rounds presentation, surgical residents create a fictional medical case and make up a chart for Santa Claus. Often he is hospitalized suffering from a host of holiday-related ailments – candy-cane scented urine and broken ribs caused by reindeer games are two that come to mind. Regardless of his condition, Santa always recovers and is sent home just in time for his Christmas Eve duties.

A 1960 Mass General menu.

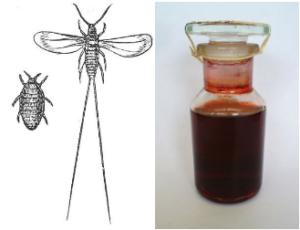

A lab technician remembered that the previous Christmas she had found bacteria that might have been S. cubana in Mr. S. Claus’s urine sample. It wasn’t real urine, and the pranksters who created it and a blood sample gave Lang their recipe – nothing in the urine concoction pointed to Salmonella. Months later, Lang was poring over the records of a young patient with S. cubana and he noticed the boy had been given a test using carmine dye. Lang didn’t know much about carmine, but he knew that it had been in Santa Claus’s blood sample. What if the two fake samples had been mixed up? He soon learned that carmine dye is made from the cochineal beetle, which could easily become contaminated with Salmonella when it is harvested.

Cochineal on a cactus. Credit: Ina Widegren.

Lang couldn’t tell whether all of the sick patients had been exposed to carmine – it was the kind of test that didn’t show up in a patient’s file unless it had unusual results. He tested the carmine dye itself, and found S. cubana. In partnership with the CDC, MGH doctors determined they could continue using carmine safely if it was heat sterilized in processing.

Many mystery outbreaks are never solved. It’s possible that without Santa Claus, this one would not have been solved either.

Tegan Kehoe is the exhibit and education specialist at the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital.

This post was first published in April 2016.

The post Santa’s Epidemiology appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 24, 2016

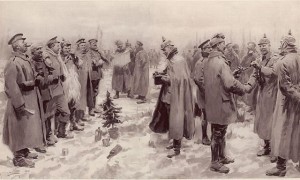

The Christmas Truce of 1914

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

My usual role at Wonders and Marvels is writing about the non-Western world, with an occasional side-step into imperialism and related topics. The next topic on my Big List of Blog Posts was the suppression of thuggee in nineteenth century India. Somehow that didn’t seem appropriate this week. Instead I offer you one of my favorite historical Christmas stories:

For most of us, the most vivid images of World War I are the trenches on the Western front. Men dug into positions on either side of a no-man’s land of craters and burned out buildings. Barbed wire and sandbags provided little protection from enemy shelling or snipers; they provided no protection from rats, lice, flooding, or the dreaded “trench foot”. The battlefields were noxious with the smell of rotting corpses, overflowing latrines and poison gas fumes.

Trench warfare was hell. It also made possible one of the most extraordinary events of the war: the unofficial Christmas armistice of 1914. The truce began when some German troops decorated their trenches with candles and Christmas trees and sang carols. British troops responded with carols of their own. On Christmas Day, some groups ventured into “no-man’s land” to share food, sing carols, hold joint services for their dead and play soccer matches.

One German soldier, Josef Wenzel, described the scene in a letter to his parents:

One Englishman was playing on the harmonica of a German lad, some were dancing, while others were proud as peacocks to wear German helmets on their heads. The British burst into a song with a carol, to which we replied with “Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht. It was a very moving moment–hated and embittered enemies were singing carols around the Christmas tree. All my life I will never forget that sight.

It is estimated that 100,000 men took part in the Christmas truce. In some places, the truce lasted only through Christmas day. In others, it lasted until New Year’s Day. In some sectors, the war continued unabated.

The Christmas truce did not recur in 1915. Both the British and the German high commands were appalled at the blatant fraternization with the enemy and gave strict orders against future incidents. After all, how do you fight a war if the men at the front decide not to fight?

Peace on earth, good will to men.

Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history, a large bump of curiosity, and a red-hot library card. Her books include The Everything Guide to Socialism, Mankind: The Story of Us and Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War.

This post was originally published in December 2015.

The post The Christmas Truce of 1914 appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 23, 2016

A Versailles Christmas

By Christine A. Jones (Guest Contributor)

A few years ago I had the pleasure of visiting the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana in Geneva (a must-do for historical bibliophiles), where the eyes feast on marvels such as a full codex of the gospel of John and a Gutenberg Bible. Among the rare court documents that Martin Bodmer collected over his lifetime sits Elizabeth I’s Christmas gift list for her courtiers; names and gifts descend in order of rank. Looking at it, you have a glimpse into Elizabethan holiday ritual. It occurred to me as a French seventeenth-centuryist that I knew little about Noël at Versailles. I turned to the fountainhead of anecdote about the Sun King’s reign: the Duc de Saint-Simon.

Versailles Chapel

Louis XIV’s outspoken courtier talks about the holiday several times in his 15-volume memoires of the court. Two mentions are incidental and occur because another important event he is describing happens to take place around Christmas. A third that briefly details holiday ritual (Chapter LXXI) is tucked into a description of the religious skepticism of Louis XIV’s brother, Monsieur, Le Duc d’Orléans. Saint-Simon sets his story of the prince’s ungodliness at midnight mass in Versailles’ chapel—three midnight masses to be exact—to which Monsieur accompanied the king. The memoires describe the beauty of the atmosphere as charmed, even for Versailles: music that surpassed the opera, magnificent decoration, and extraordinary lighting. Palace celebration, trimming and all, revolved around the mass.

In the midst of this “brilliant scene,” Monsieur sat reading what looked like a prayer book. A lady-in-waiting was moved by the vision of the Duc immersing himself in the spirit of the night and remarked on it. As Saint-Simon recollects it, the Duc responded, “You are very silly, Madame Imbert. Do you know what I was reading? It was ‘Rabelais,’ that I brought with me for fear of being bored.” So much for holy music and fabulous decoration. On Saint-Simon’s read, no manner of divine celebration could stop Monsieur from “playing the impious, and the wag,” not even Christmas at Versailles.

Christine A. Jones teaches French 17th/18th-century literature and culture at the University of Utah. She writes on fairy tales, porcelain, dance and wine.

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in December 2011.

The post A Versailles Christmas appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 22, 2016

The Gruesome and the Grotesque: A Look at Torture Methods Used in Seventeenth Century France

By Sheridan Lea (Guest Contributor)

During the 16th and 17th centuries in France, what kinds of torture were usually used, and were they really severe enough to require a physician? A brief exploration of a few common torture methods might help answer that question.

During the 16th and 17th centuries in France, what kinds of torture were usually used, and were they really severe enough to require a physician? A brief exploration of a few common torture methods might help answer that question.

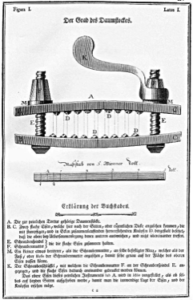

Thumbscrews

Almost exactly what they sound like they would be, thumbscrews place the thumbs of the accused in between studded boards and gradually tightened. This form of torture is sometimes depicted to include the binding of the accused so as to keep him still during the procedure. During this method, the gradual pressure from the studs likely broke the bones in the accused’s thumb, if given a long enough amount of time or a high enough amount of pressure.

The Rack

A common method of torture, the rack effectively stretched the accused, pulling him apart little by little. An individual’s limbs would be tied to ropes which would then be cranked, tightening the rope, and thus stretching the limbs away from the trunk of the body. To increase the pain felt by an individual, and force him to confess to his crimes, this method was occasionally intensified by adding an element of fire. As a suspect was on the rack, an interrogator would burn the sides of the accused with a torch. Supposedly, it was possible to hear the pops as the joints of the accused were being pulled from their sockets.

Hand-binding

This method of torture was usually reserved for women and children. Much like the thumbscrew method, hand-binding was just that. The tightness varied depending on the severity of the case, the hands of the accused were tied very tightly with cords during interrogation. If the crime were severe, sometimes the hands would be extremely tightly bound, only to be unbound and then bound once again with the same or possibly greater tightness. In extreme cases, hand binding could be coupled with the burning of the soles of the feet. In this case, the suspect’s feet would be lit on fire after being covered in a flammable substance.

As evidenced by the different methods described, there was some variability present in the harshness of each method. When a physician was present at interrogations, it was probably for use of methods like the rack, as opposed to thumbscrews. The main goal of these forms of torture was to speed up the process of confession so that the accused may be quickly sentenced for their crimes, and it was likely the fear of pain as much as the pain itself that served as a motivator for confession.

Bibliography

Langbein, John. Torture and the Law of Proof. University of Chicago Press, 1976. Pp. 16-27.

Peters, Edward. Torture: Expanded Edition. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985. Pp. 67-69.

Bennett, Makena, “Medieval Torture: A Brief History and Common Methods” (2012). A with Honors Projects. Paper 71.

Sheridan Lea is a senior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. She studies Anthropology with a minor in French.

Sheridan Lea is a senior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. She studies Anthropology with a minor in French.

The post The Gruesome and the Grotesque: A Look at Torture Methods Used in Seventeenth Century France appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 21, 2016

Beauty from Pain: A Look at 17th Century Beauty Trends and Products

By Lauren Montgomery (Guest Contributor)

What do your typical skin products contain? How about cucumber juice, white lead, and white honey? This was a popular ointment recipe used by women in the 16-17th century created by Jean Liebault to guard against the effects of the sun on the skin.

Women have tried to beautify themselves through different methods since the dawn of time, and beauty ideals have changed throughout history, from heavily lined eyes of the Egyptians to the contouring, strong brows and overdrawn and fuller lips of today (Thanks Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner). Women have gone to great extents to achieve these beauty ideals, often employing dangerous methods like waist trainers and corsets and harsh chemicals. While we might think today’s beauty trends are ridiculous, what about in the 17th century?

Women have tried to beautify themselves through different methods since the dawn of time, and beauty ideals have changed throughout history, from heavily lined eyes of the Egyptians to the contouring, strong brows and overdrawn and fuller lips of today (Thanks Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner). Women have gone to great extents to achieve these beauty ideals, often employing dangerous methods like waist trainers and corsets and harsh chemicals. While we might think today’s beauty trends are ridiculous, what about in the 17th century?

Pale Is the New Tan?

Today, women are constantly in tanning salons and on the beach trying to darken their complexions, but one of the major trends in the 17th century was actually the opposite, having extremely pale skin. This trend was influenced by both aristocracy and religion. A woman who had white skin was seen as higher status, because she didn’t need to work under the sun in the fields all day. White skin also had religious significance, since it was seen as a symbol of moral purity, and the color white was associated with purity, honesty, virginity, cleanliness, etc.

So how did women achieve this pale white look? They definitely left no stone unturned when it came to different methods. Women did everything they could to avoid exposure to the sun, including using parasols and umbrellas, facing their toilette to the north to avoid the sun’s rays, not using water on their skin in the morning because it would make the skin more sensitive to sun exposure, and even wearing masks!

Skincare

In addition to these methods, you could also expect a 17th century woman to use makeup and ointments to lighten her complexion. What was in these early forms of makeup you may ask? They were usually based on a white powder of vegetable or mineral origin, often times items you could find in your kitchen like starch, wheat, rice, etc. Other powders were more chemical and involved metal bases like mercury, bismuth, or lead. You may have heard of these metals for their toxicity and dangerous effects on the human body, but in the 17th century, metals like lead carbonate were believed to “be effective in the treatment of certain skin pathologies, capable of eroding the growths and imperfections of the skin, removing stains, and polishing, cleaning, and bleaching the face”. If phrases like “eroding growths” and “bleaching the face” sound harsh and unsafe, you’re absolutely right. The use of these substances in cosmetics lead to high incidences of lead and mercury poisoning in the 17th century, and women would often report hair loss, inflamed eyes, damaged teeth, and even blackened skin (the opposite effect they were going for with whitening products ironically). In many cases use of these products even lead to death! It definitely gives new meaning to the phrase “beauty from pain”!

In addition to these methods, you could also expect a 17th century woman to use makeup and ointments to lighten her complexion. What was in these early forms of makeup you may ask? They were usually based on a white powder of vegetable or mineral origin, often times items you could find in your kitchen like starch, wheat, rice, etc. Other powders were more chemical and involved metal bases like mercury, bismuth, or lead. You may have heard of these metals for their toxicity and dangerous effects on the human body, but in the 17th century, metals like lead carbonate were believed to “be effective in the treatment of certain skin pathologies, capable of eroding the growths and imperfections of the skin, removing stains, and polishing, cleaning, and bleaching the face”. If phrases like “eroding growths” and “bleaching the face” sound harsh and unsafe, you’re absolutely right. The use of these substances in cosmetics lead to high incidences of lead and mercury poisoning in the 17th century, and women would often report hair loss, inflamed eyes, damaged teeth, and even blackened skin (the opposite effect they were going for with whitening products ironically). In many cases use of these products even lead to death! It definitely gives new meaning to the phrase “beauty from pain”!

But what about the women who didn’t want to put harsh chemicals and substances on their skin? In 17th century cosmetics, there was also a place for more organic products. Many ointments used gourd products like pumpkin, squash, and melon purees, to give a calming and refreshing effect to the humeurs. Starting in the 16th century, cucumber was used for a similar used externally, and over the course of the next century, cosmetic waters and products used more distilled gourd products, especially for ointments that removed redness and refreshed the skin. It was a true 17th century spa experience!

But what about the women who didn’t want to put harsh chemicals and substances on their skin? In 17th century cosmetics, there was also a place for more organic products. Many ointments used gourd products like pumpkin, squash, and melon purees, to give a calming and refreshing effect to the humeurs. Starting in the 16th century, cucumber was used for a similar used externally, and over the course of the next century, cosmetic waters and products used more distilled gourd products, especially for ointments that removed redness and refreshed the skin. It was a true 17th century spa experience!

Completing the Look

While white makeup was the base of most looks in the 17th century, in order to spice up or complete their look, women would add red paint to their lips and cheeks. This paint was often based in vermillion, an orange-red pigment derived from mercury. They found creative ways to create red pigments and went so far as to use cochineal, which was derived from an insect! Other sources included shredded timber like red sanders and brazilwood and other vegetable derived substances. Finally, if a woman was feeling self conscious about different blemishes on her skin, she might cover them with small decorative patches, which were introduced in the mid 17th century.

Bibliography

Lanoë, Catherine. La poudre et le fard: une histoire des cosmétiques de la Renaissance aux Lumières. Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2008. Print

Gunn, Fenja. Artificial Face: History of Cosmetics. David & Charles, 1973. Print

Pointer, Sally. The artifice of beauty: a history and practical guide to perfumes and cosmetics. Stroud : Sutton, 2005. Print

Corson, Richard. Fashions in makeup: from ancient to modern times. London : Peter Owen, 1972. Print

Lauren Montgomery is a senior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. She is originally from Dallas, TX and is majoring in French and European Studies.

Lauren Montgomery is a senior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. She is originally from Dallas, TX and is majoring in French and European Studies.

The post Beauty from Pain: A Look at 17th Century Beauty Trends and Products appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 20, 2016

Race and Gender in the Selection of Patients for Lobotomy

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

I researched my book The Lobotomist, a biography of lobotomy developer and advocate Walter Freeman, M.D., more than ten years ago. I still remember the dismay I felt when I turned up evidence that described how Freeman and his fellow psychosurgeons considered race and gender when they decided whose brains they would cut and disrupt in their quest to treat psychiatric illnesses.

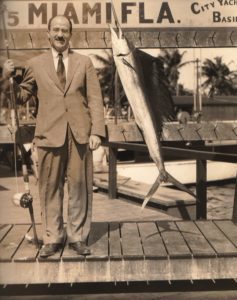

Lobotomist Walter Freeman after deep sea fishing in Florida, 1940

Freeman’s racial attitudes were complicated. As president of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia during the late 1940s, he worked hard to change the organization’s by-laws to allow it to admit African American physicians as members. Yet Freeman held peculiar beliefs about the psychological make-up and social influences of people of color, and these affected his treatment of patients.

He believed, for instance, that African American psychiatric patients, especially women, were among the best candidates for lobotomy because of what he called “the greater family solidarity manifested by these people.” Freeman meant that in his opinion black families were more likely to give their relatives who survived lobotomy devoted post-operative care. In addition, he was impressed by the results lobotomy produced among black patients. At the West Virginia state hospital in Lakin, Freeman operated on many African American patients in 1952 and was happy when he returned “a week or so after operating upon twenty very dangerous Negroes and found fifteen of then sitting under the trees with only one guard in sight,” he wrote.

Chillingly, Freeman in 1951 volunteered to experimentally use his transorbital lobotomy technique on black patients at the Veterans Administration hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. When a neurosurgeon on staff protested, though, the Veterans Administration banned the use of this procedure at this hospital, and in the words of Freeman’s fellow lobotomist William Sargant, the “whole Negro-rescue plan had to be cancelled.”

At the same time, women disproportionately became targets for lobotomization. Of Freeman’s first twenty psychosurgery patients, seventeen were women. From the 1940s through the mid-1950s, men slightly outnumbered women as patients in state hospitals, yet female patients made up about 60 percent of those who underwent lobotomy. A preponderance of women suffering from depression and other affective disorders may be partly responsible, but agitated and boisterous behavior in women was less acceptable to doctors of Freeman’s time than the same behavior in men. Many psychiatrists believed it was easier to return women after operation to a life of domestic duties at home than it was to post-operatively rehabilitate men for a career as a wage earner.

On people of all races and genders, Freeman and his fellow practitioners of lobotomy began performing fewer of the operations after the introduction of psychoactive medications in the U.S. in 1954. When Freeman died in 1972 — remaining a believer in lobotomy to the very end — only a small number of the operations were still being given anywhere.

Further reading:

El-Hai, Jack. The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness. (Wiley, 2005)

Phillips, Michael M. “The Lobotomy Files: One Doctor’s Legacy.” A Wall Street Journal Special Project.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools. The post Race and Gender in the Selection of Patients for Lobotomy appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

Genocide City: the beginnings of WWII in Berlin

Wehrmacht photographing the execution of hostages in Russia in 1941

By Peter Fritzsche (Guest Contributor)

Seventy-five years ago, Helmuth James von Moltke, the great-grandnephew of the famed general in the 1870 Franco-Prussian war, and later, a lonely prisoner of conscience whom the Nazis would execute in 1945, thought the world was coming to an end. Working for the German military in Berlin, he knew a great deal. “The day is so full of gruesome news that I can hardly write,” he confided to his diary on October 21, 1941: “In Serbia, two villages have been burned to the ground. 1700 men and 240 women have been executed. That is the ‘penalty’ imposed for an attack on three German soldiers.” These outrages were “just the first ominous signs of the coming storm.” “Since Saturday,” Moltke added, Berlin’s “Jews are being rounded up.” “What do I say,” he wondered, “if someone asks: and what did you do during these times?” How can “I sit at the table in my heated apartment and drink tea?” The Nazi machinery of destruction continued to supply a steady stream of victims: “Russian prisoners, evacuated Jews, evacuated Jews, Russian prisoners, executed hostages.”

Deportation of Berlin Jews fall 1942

In fall 1941, Berliners could see the Holocaust taking shape. Elisabeth Freund, a young Jew, reported on the “horrible wave of anti-Semitic propaganda:” “Along the whole Kurfürstendamm signs hang in almost every shop,” she noted: “‘No Entry for Jews’ or ‘Jews Not Served.’ If you walk along the street you see ‘Jew,’ ‘Jew,’ ‘Jew’ on every house, on every window pane, in every store.” CBS new correspondent Howard K. Smith pointed out the “jet-black” leaflets littering mailboxes. They have “a bright yellow star on the cover” with “the words: ‘Racial Comrades! When you see this emblem, you see your Death enemy!’” Nazi Germany was startlingly frank about its life-and-death struggle with the Jews. By contrast, in Albert Camus’ veiled novel about World War II, The Plague, it took a long time before city officials dared to use the word “plague;” notices were put up where no one would see them, and newspapers only slowly reported on the death of victims. There was no such hesitancy about what the Nazis considered to be the Jewish plague in 1941.

Kassel deportation 1941

Ordinary Germans understood the broad outlines of the destruction of Jewish communities. They deliberated the deportations of neighbors occurring around them. “The ones from in our neighborhood have had to assemble themselves in Bremen,” wrote one Red Cross helper–“in 2 big schools, right near Heinz and Alma. There they reside with kit and caboodle and they look just terrible.” But these small flickers of sympathy had to be extinguished; “Jews now have to take responsibility for their own kind.” At the same time, news about the murder of Jewish civilians in the Soviet Union–the destination of many of Germany’s deported Jews–raced across Germany. News about Babi Yar, the “big bloodbath” of Kiev’s Jews at the end of September 1941, reached a schoolteacher in Breslau already on October 11. The rumors usually came in three parts, revealing a genuine sense of horror. First, there was the information that the victims included women and children; second, came the fact that victims went to their deaths naked or partly naked; and third, the revelation that SS shooters, the Nazi paramilarities, sometimes went mad. The reference to the SS shows that already in 1941 Germans distinguished SS killers from the allegedly “clean” Wehrmacht, the regular troops.

Bielefeld deportation 1941

The mix of pity, horror, and justification was typical, but came in different combinations. Germans plainly deliberated their regime’s anti-Jewish actions and decided for themselves where exactly to put the information about German killers and Jewish victims. Loyal Nazis such as the Red Cross worker embraced the racial doctrines of the regime, including “special treatment” for the Jews. The course of events, as persecution gave way to outright murder, pulled them deeper into the Third Reich. Others confronted the horror engulfing Jews but since they distinguished “SS shooters” from the regular army, they understood the crimes as outrages undertaken by fanatics rather than as part of a comprehensive state policy. Appalled at the fate of the Jews, a large number of Germans still located the Holocaust on the periphery of wartime events. Nazi sympathizers endeavored to excise empathy altogether by putting Germany’s Phoenix-like rise from defeat in 1918 to victory so near at hand in 1941 first, while doubters of all kinds contained dangerous knowledge by putting the source of anxiety to the side in order to preserve their benevolent idea of Germany.

Peter Fritzsche is the W. D. & Sarah E. Trowbridge Professor of History at the University of Illinois. The author of nine books, including the award-winning Life and Death in the Third Reich, he lives in Urbana, Illinois.

The post Genocide City: the beginnings of WWII in Berlin appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 19, 2016

The Traveling Life of Things

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

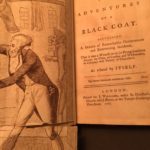

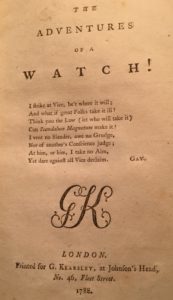

One of the more curious types of travel fiction that circulated in the eighteenth century was the tale of the adventures of a thing. In these books, inanimate objects were the central characters and narrators. The narrator’s voice could belong to anything – one of the most popular was The Adventures of a Corkscrew, and other bestsellers were The Story of a Black Coat, The Adventures of a Rupee, The Adventures of a Watch. The voice of the narrator could also come from the vehicle by which goods and people were transported, as in The Life of a Ship, from the Launch to the Wreck, or The Adventures of a Hackney Coach.

One of the more curious types of travel fiction that circulated in the eighteenth century was the tale of the adventures of a thing. In these books, inanimate objects were the central characters and narrators. The narrator’s voice could belong to anything – one of the most popular was The Adventures of a Corkscrew, and other bestsellers were The Story of a Black Coat, The Adventures of a Rupee, The Adventures of a Watch. The voice of the narrator could also come from the vehicle by which goods and people were transported, as in The Life of a Ship, from the Launch to the Wreck, or The Adventures of a Hackney Coach.

These ‘circulation novels’ were books for adult readers, who were fascinated by the expanding consumerism and the global world of luxury goods and money. Unlike most people, objects that traveled did so freely, crossing social and territorial boundaries, moving with ease from the workshop to the street to the boudoir of a lady. Authors of circulation novels were quick to see the erotic potential in the subject. In The Adventures of a Bank-Note, the narrator is thrilled to find himself tucked between the breasts of a lady: “Oh reader, think (if thou hast any sensation) of my happy situation! Dissolv’d in pleasure, I lay gasping and panting like a great carp in a fishmonger’s basket, placed in a vale between two snowy mountains.”

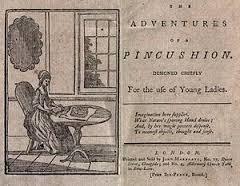

By the end of the eighteenth century, though, circulation novels were increasingly written for children. Imagining the life of an inanimate object became something consigned to the magical imagination of the very young. It takes more of an effort, in the modern age, for adults to look at an item of clothing or a coin or a household appliance and muse over where those things have been, although certainly the  global travels of objects and their parts is even more vast now than it was in 1800. Victorian literature turned toward the educational value of the story of the travels of a doll or a teddy bear, and away from the playful voyeurism of traveling underclothes, jewelry, and money. Beginning with Mary Ann Kilner’s Adventures of a Pincushion, writers of circulation novels focused on the instructive utility of object adventure. The pincushion is a little philosopher, who peppers the tale with reflections on the behavior it observes and admonishes girls who behave badly.

global travels of objects and their parts is even more vast now than it was in 1800. Victorian literature turned toward the educational value of the story of the travels of a doll or a teddy bear, and away from the playful voyeurism of traveling underclothes, jewelry, and money. Beginning with Mary Ann Kilner’s Adventures of a Pincushion, writers of circulation novels focused on the instructive utility of object adventure. The pincushion is a little philosopher, who peppers the tale with reflections on the behavior it observes and admonishes girls who behave badly.

The circulation novel or ‘it-novel’ as it is now sometimes called, survives today in children’s literature, especially of the Christmas variety, when we bask in consumer culture. From the magical bell and train in The Polar Express to the dancing toys in The Nutcracker Suite, we imagine a world where inanimate objects from around the world are alive. And Santa Claus and his reindeer are the biggest travelers of all.

The circulation novel or ‘it-novel’ as it is now sometimes called, survives today in children’s literature, especially of the Christmas variety, when we bask in consumer culture. From the magical bell and train in The Polar Express to the dancing toys in The Nutcracker Suite, we imagine a world where inanimate objects from around the world are alive. And Santa Claus and his reindeer are the biggest travelers of all.

For Further Reading: The Secret Life of Things: Animals, Objects, and It-Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England. Edited by Mark Blackwell (2007).

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin (PublicAffairs Books, 2012). She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

The post The Traveling Life of Things appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 16, 2016

The Ribbon King

By Lucy Hall Hartley (Guest Contributor)

Bust of Louis XIV, 1660

In the late 1670s, a fashion trend emerged amongst Hommes de Qualité in France. Men of stature began wearing a bouquet of ribbons over one shoulder. The Mercure galant, the premiere publication delivering fashion news to trendy 17th-century readers, and other sources of fashion prints, illustrated men wearing the stylish ribbon bouquets from the late 1670s into the 1680sThis accessory was just one of many in the long list of must-have items for the fashionable Frenchman of the 17th century, though not as iconic or long-lasting as high-heeled shoes and cravats.

Louis XIV, King of France, was at the forefront of many men’s fashion trends but interestingly did not wear shoulder ribbons. Jean Donneau de Visé, fashion journalist for the Mercure galant, wrote in 1682 that Louis did not wear the shoulder ribbons because they got caught in his long hair (Thépaut-Cabasset 135).

Louis le Grand, portrait by Nicolas Arnault, 1689

This did not stop artists who produced fashion prints fromportraying the king with bouquets of ribbons, however. Kathryn Norberg writes in the book Fashion Prints in the Age of Louis XIV that “expediency—that is to say, the need to create new prints and sell them quickly—probably motivated the printer” (154). This expediency trumped accuracy and fashion printers, often far from the court, would improvise the clothing of the king in the interest of time. The fashion prints below portray Louis XIV dressed quite elegantly with bouquets of ribbons hanging from his shoulders.

If before the Sun King shunned ribbons, he championed them in later years. 1689 likely marks the year the king began wearing ribbons, not as a means to conform to a dying trend, but in order to revive it for economic purposes. Louis wanted to give the French ribbon makers work. In the August edition of the 1689 Mercure galant, Donneau writes:

The reign of ribbons started again two months ago, and since it’s at Versailles that the first ones appeared, each person has made it [his personal] law to wear them. Luxury has almost always invented fashions, but charity has caused the rebirth of this one. The workers needed us to reprise it, and the King who abandoned this trend long before others, because he does not have the taste for the superfluous, much wished wear the first [ribbons] to give an example.

Le règne des rubans a recommencé depuis deux mois, & comme c’est à Versailles que les premiers ont paru, chacun s’est fait une loy d’en porter. Le luxe a presque toujours fait inventer les Modes ; mais la charité a fait renaistre celle-cy. Les Ouvriers avoient besoin que l’on en reprist, & le Roy qui avoit abandonné cette mode longtemps avant les autres, parce qu’il ne gouste pas ce qui est superflu, a bien voulu emporter le premier pour donner l’exemple. (312)

The history of the shoulder ribbon bouquet incorporates many elements of the complications of a fashion trend in 17th-century France. Oddly, the trend was able to take hold without the blessing of the most fashionable man in Europe. Only when it became relevant to the economy did Louis XIV begin wearing shoulder ribbons.

Bibliography

Arnault, Nicolas. Portrait de Louis XIV, en pied. Digital image. Gallica. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Donneau De Visé, Jean. Mercure Galant Aug. 1689: 311-13. Gallica. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6...

Norberg, Kathryn. “Louis XIV: King of Fashion?” Fashion Prints in the Age of Louis XIV: Interpreting the Art of Elegance. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech UP, 2014. 135-65.

Portrait de Louis XIV, en buste, de 3/4 dirigé à droite dans une bordure ovale. Digital Image. Gallica. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Thépaut-Cabasset, Corinne. L’ Esprit Des Modes Au Grand Siècle. Paris: Editions Du CTHS, 2010.

Lucy Hall Hartley is a Senior in the College of Arts and Sciences at Vanderbilt University majoring in French and Neuroscience. She enjoys fashion and clothing from multiple standpoints, as an observer, wearer, and maker.

The post The Ribbon King appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.