Holly Tucker's Blog, page 5

February 3, 2017

Five for Friday: The Last Day of Leda Grey

Interview with Essie Fox

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

The Last Day of Leda Grey is the story of a reclusive old woman who once starred in Edwardian silent films. Leda is entirely fictional, but her youthful image was inspired by a picture of Theda Bara I once saw in a junk shop window – with Theda dressed for her starring role in a film called Cleopatra. Sadly that film has now been lost, but many photographs remain of the very first vamp of the silent screen. They, and some myths and legends based on Egyptian mummies, inspired me to write the story of an actress whose flickering eerie films begin to haunt her real life.

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

In the years leading up to the First World War the film business was in its infancy. With many professional photographers, and even stage magicians being drawn into the industry there were often incredible special effects. All the wonders and marvels of double exposures, or theatrical smoke and mirror tricks in which these directors were well versed.

However, before writing the fantasies I needed to know the real facts. I read general Edwardian histories, then more specific details about people who’d worked in the industry – all of which can be found at end of my novel. But, perhaps the most valuable resources were all the old photographs and stills I found in books, or else online. The BFI has a growing list of silents that they have digitized, as does the Library of Congress. Many of these are on Youtube today. I recommend Georges Méliès!

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

The biggest challenge was the structure. Although the book looks back in time to events in Leda’s Edwardian youth I decided to set the main story in 1976, when she’s visited by a journalist who has come across a photograph of Leda in a silent film. He can’t get her image out of his mind, and when he discovers she’s still alive, having hidden away as a recluse in an isolated cliff top house for more than half a century, he is compelled to track her down in the hope of obtaining an interview.

As he is my main narrator I had to find a way for her to tell him the story of her life – with many mysterious clues to solve. In the end, I revealed much of this through their present day conversations – or by Leda showing him old films – or through memoirs that she lets him read; what she calls her Mirrors. Mirrors, because they reflect the past. But they may not always tell the truth.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

I cut out so much of the backstory related to Ed, my young journalist – so much that I think I could write a whole new book based on his memories. Perhaps I will. I know I’m finding it hard to let Ed Peters go…

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

I am tagging Anna Mazzola whose debut Victorian Mystery, The Unseeing, is based on a true sensational crime. The novel has many twists and turns, and the finely tuned period detail is there but never outweighing the essence of the characters and the story told.

Essie Fox lives in London. Having worked in publishing and design she now writes historical novels published by Orion Books. Her debut, The Somnambulist, was shortlisted for the National Book Awards. Her latest, The Last Days of Leda Grey, is essentially a ghost story with the theme of Edwardian silent film.

Essie Fox lives in London. Having worked in publishing and design she now writes historical novels published by Orion Books. Her debut, The Somnambulist, was shortlisted for the National Book Awards. Her latest, The Last Days of Leda Grey, is essentially a ghost story with the theme of Edwardian silent film.

Missed our previous Five for Friday? Check out our interview with Ami McKay about The Witches of New York or our interview with Eva Stachniak about her book The Chosen Maiden. Still craving some tidbits about fabulous women? Read our post about “Fashion as Resistance in WWII France” by Anne Sebba.

The post Five for Friday: The Last Day of Leda Grey appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 2, 2017

A Failed Immigration Ban: Closing the Mexican Border

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Concerns that immigrants flooding across the border threaten the nation’s basic institutions. Construction of armed posts to defend the border. Passage of new, more restrictive immigration laws. Sound familiar? Welcome to Mexico in 1830.

The story began when Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821. At first the newly independent country welcomed settlers from the United States. The government signed contracts with immigration brokers, called empresarios, who agreed to settle a set number of immigrants on a set piece of property in a set amount of time. In exchange for the right to buy land, settlers agreed to obey Mexican law, become Mexican citizens, and convert to Catholicism. At the same time, the US Congress passed a new land act that made emigration to Mexico even more appealing. Public land in the US cost $1.25/acre*, for a minimum of eighty acres and could no longer be bought on credit. Public land in Mexico cost 12 1/2¢/acre and credit terms were generous. Not a hard choice for anyone who was cash-poor and land hungry.

Some empresarios brought in groups of settlers from France or Germany. More, including Stephen Austin,** brought in settlers from the southern United States. Most new colonists settled in new communities east of modern San Antonio. By the mid-1830s, Anglo settlers outnumbered native Tejanos by as many as 10 to 1 in some parts of Texas. These settlers brought the culture of the American South with them, including slaves and slavery.*** In addition, many Anglo settlers traded (illegally) with Louisiana rather than with Mexico.

Concerned about growing American economic and cultural influence in the region, the Mexican government passed a law banning immigration into Texas from the United States on April 6, 1830. They also assessed heavy customs duties on all US goods, prohibited the importation of slaves, built new forts in the border region and opened customs houses to patrol the border for illegal trade.

The law didn’t have the intended affect. Instead of re-gaining control over Texas, Anglo colonists and the Mexican government were in constant conflict. The law was repealed in 1833, too late to staunch the wound. The first shots in what would become the Texas War of Independence were fired on October 2, 1835.

*$31.44 in today’s currency. Still a bargain.

** Hence Austin, Texas. (I don’t know about you, but I’m always curious as to how a town got its name.)

***Outlawed in Mexico is 1829–so much for obeying the laws.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Find Pamela on Twitter at @pdtoler

Read more of her writing on her personal blog

The post A Failed Immigration Ban: Closing the Mexican Border appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 1, 2017

Revisiting Dreyfus: Fake News and Alternative Facts in the Nineteenth Century

By Rachel Mesch (Regular Contributor)

In October of 1894, a French man by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested for passing confidential documents to Germany. If you are reading this on the Wonders & Marvels page, chances are, you know that part of the story already. (If not, you can review the details here.) But the reason that you know this story is also why it remains relevant today: as a controversy driven by the press. Indeed, the arrest of Dreyfus turned into the Dreyfus Affair because of the media—and because of the French public’s insatiable appetite for news.

“The Age of Paper”

In late nineteenth-century France, the rapidly developing, technologically advanced mass press had taken root like nowhere else. Fueled by an increasingly literate public, looser laws on freedom of expression, and a competitive marketplace, the number of newspapers multiplied. Circulations skyrocketed from a combined total of one million in 1870 to five million in 1910. Whereas in 1882 there were 3,800 periodicals printed in France, within ten years that already sizable number had tripled.

The proliferation of the mass press had an immediate effect on the French public, especially those in Paris. As historian Vanessa Schwartz has demonstrated, newspapers changed the way that city dwellers related to each other, allowing readers to feel as if they were part of a social community, reading about the same things, interested in the same stories. But this new virtual community also had ways of tearing people apart.

It was in the midst of this subtle yet profound transformation of the urban social fabric that the arrest of Captain Dreyfus became the Dreyfus Affair.

Truth Vs. Hate

As the espionage intrigue unfolded, full of emerging and mostly untruthful details about who gave what to whom and why, a vast web of publications, able to churn out both morning and evening editions (the original “24 hour news cycle”), fed the public’s unquenchable thirst for new information. For those paying close attention, the facts were proven to be on Captain Dreyfus’s side fairly quickly: in 1896 Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart, no friend of French Jews himself, discovered the real spy in Captain Esterhazy and provided the evidence to prove it.

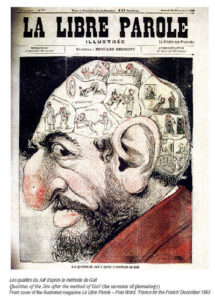

A caricature of the Jewish brain from Drumont’s illustrated weekly.

No matter. Dreyfus would not be exonerated for another ten years.

This was largely because, with the help of the mass press, the Dreyfus Affair pitted facts against feelings, turning marginal flames of hate into a raging anti-Semitic fire.

Guess which side sells more papers?

Before Zola made his voice heard in 1898, most newspapers were feeding the slow-brewing populist rage against the intellectual class, with a special hatred for Jews like Dreyfus who had risen up in French society through the military.

The French Anti-semite-in-chief was Édouard Drumont, who had written the virulent tract La France Juive (Jewish France) in 1886 and followed up by establishing his Antisemitic League. But it wasn’t until he launched his newspaper La Libre Parole (The Free Word) that he had a vehicle in which to serve up hateful stereotypes on the daily.

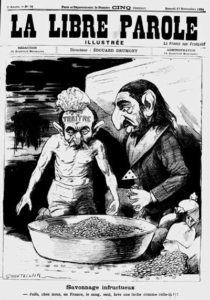

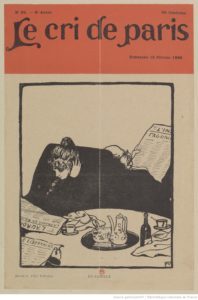

November, 1894. “Fruitless Washing.” “Jews, here in France only blood washes out this kind of stain.”

The Panama scandals of 1892—involving German Jews Jacques Reinach and Cornelius Herz—paved the way for the Affair, showing Jewish involvement in state sanctioned bribery. Drumont’s newspaper offered juicy details installment by installment. In doing so, it created an addicted readership primed for daily controversy. The ingredients for the perfect (media) storm were now at the ready.

After Alfred Dreyfus’s arrest and repeated convictions, La Libre Parole hit its hateful—and self-congratulatory–stride. “Down with Jews” screams one famous headline above an image of Drumont himself. The illustrated version of the newspaper rejoiced in full page meme-like cartoons on its covers. “Frenchmen,” reads one caption from 1894 calling out “Judas Dreyfus.” “I’ve been telling you this every day for eight years!”

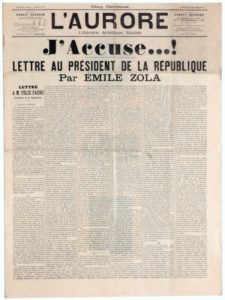

While initially anti-Dreyfus sentiments dominated the daily papers, supporters of Dreyfus slowly found their voice, aided ultimately by Emile Zola’s famous accusation—where else but on the front page of a daily newspaper. Zola’s 1898 “J’accuse” was as much an act of typographical genius as a rhetorical one: the bold-faced letters of his plea demanded attention through dramatic visual revolt against the broadsheet itself.

Alternative Facts

With one side deftly fanning the fames of populist rage, the other side continued to insist on the facts of the matter. “You want confessions? Here are some!” declared a poster from 1898, delineating the various testimonies that should have resolved the whole thing.

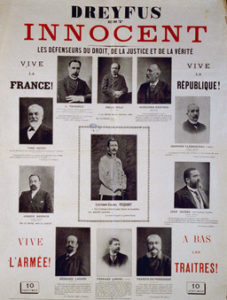

“Dreyfus, An Innocent Man”

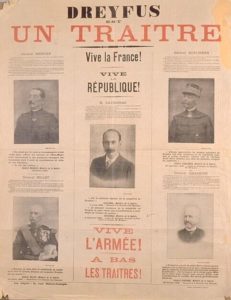

“Dreyfus, A Traitor”

But facts were no match for… alternative facts.

When anti-Dreyfusards created an official looking poster in 1898 declaring Dreyfus a traitor, replete with photographs of government ministers making statements to that effect, Dreyfusards responded precisely in kind.

They produced a mirror image, with their own officials testifying to the captain’s innocence.

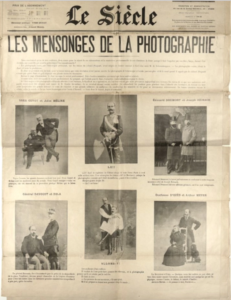

And thus the most polarizing controversy of the modern era took its intractable shape, with each side doubling down on their version of the truth. But how to tell the difference, in what must have felt like a brave new journalistic world? How to distinguish between fact and fiction, equalized with the proper fonts and technological flourishes? The camera was a still new technology, especially for newspapers, and readers were inclined to trust its veracity. To call attention to this very problem, in 1899 the newspaper Le Siècle published a series of images entitled “The Lies of Photography.”

“The Lies of Photography”

In order to demonstrate how easy it was to doctor photographs, they juxtaposed sworn enemies in chummy postures. It was time for the French to learn that the camera does lie sometimes.

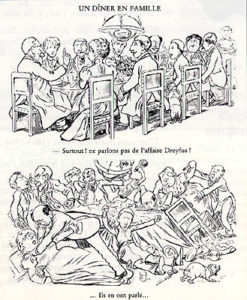

“A Family Dinner” before and after the Affair is mentioned.

So what was the public to do?

Buy more newspapers of course, devour any details to confirm the accuracy of their side, and fly into a blistering rage when faced with the opposition.

A Polarized Society

The media was happy to record this as well. Who doesn’t need a dose of self-deprecating humor in the midst of these maddening debates? Images from newspapers show happy families descending into chaos at the mention of Captain Dreyfus.

Neutrality proved impossible even in the domestic safe space of the breakfast table as husbands and wives retreated to their separate headlines. Bedrooms were torn asunder; togetherness seemed impossible.

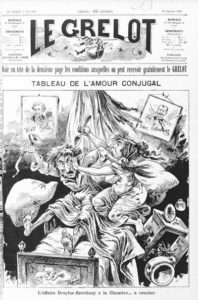

“A Portrait of Conjgual Love,” 1898, with Zola as hero on one side, and Esterhazy denounced on the other.

People were no longer talking to each other, no longer meeting each other’s eyes, their interactions mediated exclusively by their choice of media.

People were no longer talking to each other, no longer meeting each other’s eyes, their interactions mediated exclusively by their choice of media.

Truth Wins?

The Dreyfusards were eventually vindicated, with the Captain’s full exoneration coming in 1906. The side of truth had spilled the most ink in the end—through long treatises, full published volumes, and tedious records of the trials and legal proceedings. The facts can be boring, sometimes.

But if truth ultimately won the media war that was the Dreyfus Affair, it was a Pyrrhic victory at best. The anti-Dreyfusards had waged far too many inky battles, in sound bites and caricatures, inflammatory headlines and vile rhetoric, for the public to emerge unscathed.

Further reading:

For more on the extensive visual record of the Dreyfus Affair, see Norman L. Kleeblatt’s edited volume for the Jewish Museum, The Dreyfus Affair. Art, Truth & Justice. Berkeley: U of California Press, 1987.

The Fonds Dreyfus at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaisme in Paris has a wonderful collection of over 3,000 objects relating to the Affair, over two-thirds of which are personal items that belonged to the Dreyfus family.

For more on the late nineteenth-century mass press and its impact on Parisian society, see Vanessa Schwartz, Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris. Berkeley: U of California Press, 1999.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York. She is the author of Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman (Stanford UP, 2013) and The Hysteric’s Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle. She is currently at work on a book examining transgender identity in the nineteenth century.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York. She is the author of Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman (Stanford UP, 2013) and The Hysteric’s Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle. She is currently at work on a book examining transgender identity in the nineteenth century.

The post Revisiting Dreyfus: Fake News and Alternative Facts in the Nineteenth Century appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 31, 2017

Fashion as Resistance in WWII France

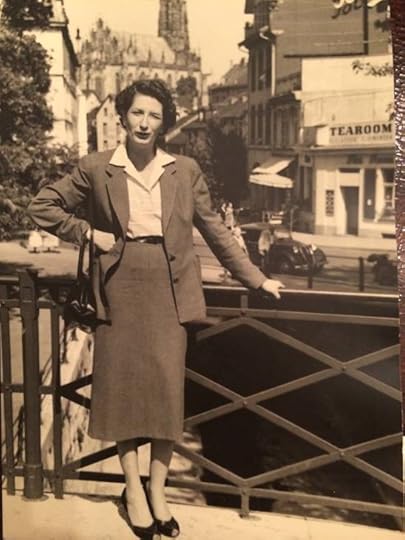

Odette Fabius, member of the Résistance and survivor of the Ravensbruck camp. Here, she proudly wears a Lanvin suit while being an active résistante.

By Anne Sebba (Guest Contributor)

Mentioning resistance in France during World War Two conjures up images of brave citizens blowing up railroad tracks, assassinating Nazi soldiers or broadcasting information on secret wireless sets. And it’s usually men who are involved. But there were many types of resistance. For women, especially those trapped in Paris who had to encounter Germans possibly on a daily basis, there were constantly decisions to be made: should you walk out of a café if the enemy came in, could you hide a downed airman before moving him on to a safe house or even distribute resistance documents and pamphlets? Some women, concerned for the safety of their children or elderly parents, decided that they would use fashion and keeping stylish as a weapon of resistance. Yet, at a time when materials were rationed and often hard to come by, remaining fashionable was far from trivial for Parisiennes throughout the War. It became a matter of personal and national pride to dress in as beautiful and outrageous a way as possible.

For many women this was the best revenge they could exert on their German occupiers. The writer Colette, in Paris throughout the War, observed young women and the ridiculous concoctions on their heads of flowers, vegetables, straw, cascades of ribbon and even an upside down bird concluding that they were driven by ‘the terrible rage to live.’

Reflecting on this for the past five years as I’ve been writing a book about Parisian women in wartime, I’ve concluded that while British and American women could wear smart military uniforms to show they were resisting evil, French women, after the armistice, had no way of showing they were on the side of the morally righteous. So flaunting fashionably ridiculous hats and short skirts with large power sleeves was often the best they could do. From the moment war was declared, magazines played a role urging women to ‘stay how they (their menfolk) would like to see you. Not ugly… The men want to think of you looking how you did when they said goodbye, pretty and soignée.’ They argued that the Germans might be running the country but they could not destroy the pride and the sense of superiority in fashion that Parisiennes considered was theirs.

Those magazines that continued, even with limited paper supplies, became increasingly popular during the War years. They often gave advice on how to adapt existing items including patterns for dresses made of several different fabrics – not intrinsically beautiful but fashionable by force of circumstance. Shoes were now made of cork or wood and resourceful girls would spend hours artfully covering them with scraps of fabric trying to make them chic. Throughout the War, finding silk stockings (other than those costing 300 francs on the black market, ten times the price of a pre-war pair) caused particular difficulties since it was considered distinctly unladylike in France to be seen without stockings. Yet wearing trousers, insufficiently femini ne, was in theory banned according to an unenforceable law dating from 1800 that was reinforced by Vichy as well as individual prefects who equated trouser wearing with female emancipation. Elizabeth Arden invented a miracle bottle of iodine dye sold in three shades: flesh, gilded flesh and tanned flesh marketed as ‘the silk on your legs without silk stockings.’ Some women also became adept at painting a straight black line up their calves to imitate the seam of a real stocking. But others, especially women resisters working as couriers or delivering leaflets, took to wearing culottes – trousers disguised as a skirt – since traveling by bicycle was essential and it was important for them not to draw attention to themselves. For most women in wartime France, fashion was a question of overcoming shortages and deprivation caused by the enemy and a determination to remain elegant was paramount.

ne, was in theory banned according to an unenforceable law dating from 1800 that was reinforced by Vichy as well as individual prefects who equated trouser wearing with female emancipation. Elizabeth Arden invented a miracle bottle of iodine dye sold in three shades: flesh, gilded flesh and tanned flesh marketed as ‘the silk on your legs without silk stockings.’ Some women also became adept at painting a straight black line up their calves to imitate the seam of a real stocking. But others, especially women resisters working as couriers or delivering leaflets, took to wearing culottes – trousers disguised as a skirt – since traveling by bicycle was essential and it was important for them not to draw attention to themselves. For most women in wartime France, fashion was a question of overcoming shortages and deprivation caused by the enemy and a determination to remain elegant was paramount.

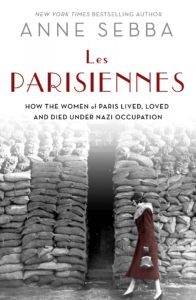

Photo Credit @Serenaboltonphotography

Anne Sebba is former foreign correspondent for Reuters who has written ten books, mostly biographies of women, including Enid Bagnold, Mother Teresa, Laura Ashley, Jennie Churchill and Wallis Simpson (aka That Woman). She makes regular TV appearances and her latest book is Les Parisiennes: How the women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died under Nazi Occupation (St Martin’s Press).

The post Fashion as Resistance in WWII France appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 30, 2017

The Early American Daguerreotype

By Sarah Gillespie (Guest Contributor)

Mid-nineteenth-century American society liked to tout its eagerness to embrace the new. The term “go-ahead” was often shorthand to indicate the nation’s forward-looking character, as when Samuel F. B. Morse remarked upon his telegraph: “There is more of the ‘Go-ahead’ character with [Americans], suited to the character of the electro-magnetic telegraph.” Despite Americans’ belief in their own progressiveness with regard to new technologies, the French invention of the daguerreotype (one of the first photographic processes) was initially met with uncertainty, skepticism, and wariness on the part of Americans.

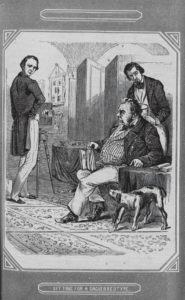

Timothy Shay Arthur’s “Sitting for a Daguerreotype,” in Sketches of Life and Character. Philadelphia: J. W. Bradley, 1850.

Perhaps it was due to the aura of the supernatural around the radical idea of a reflection being captured and held. The operator had the slight aura of a conjurer, disappearing behind a curtain before emerging to reveal, as if by magic, the image floating upon the silvered, finished plate. A magazine called The Pathfinder exclaimed: “When [the daguerreotype was] first announced, most persons imagined it to be a delusion. It seemed at the time utterly incredible.” A group of artists in Philadelphia, upon reading an early letter describing the new process, mocked the idea: “[The letter] was received with considerable ridicule by most present. After the discussion the consensus of the meeting was that they could believe Herschel’s moon story, but this one—never.” “Herschel’s moon story” was a famous hoax in which a series of newspaper articles falsely attributed to British scientist Sir John Herschel fooled New Yorkers into believing all kinds of fantastic creatures lived on the moon, such as men with bat wings. The New York Morning Herald admitted, about the daguerreotype, “I am aware that you will think that this is a second moon hoax, and so I thought till sufficient reasons were adduced, when I was forced to the belief.” Humor was often used to mask this uncertainty about the technology: “Every thing and every body may have to encounter his double every where, most inconveniently.”

Language of the otherworldly is often apparent in early commentaries about the daguerreotype; it was characterized as having “magic power,” and the camera itself was referred to as the “magic box.” In addition, the final image was thought to rarely resemble the subject.

Perhaps, despite their optimism, mid-nineteenth-century Americans were simply overwhelmed with the ever-widening array of rapidly evolving technologies. One of the earliest written descriptions of the daguerreotype, published in the U.S. in April 1839, described a sort of bewilderment around the new medium: “Invention . . . has found out the one new thing under the sun. . . . There is no breathing space—all is one great movement. Where are we going? Who can tell? The phantasmagoria of inventions passes rapidly before us—are we to see them no more?”

Americans eventually overcame their uncertainties regarding the daguerreotype. Indeed, they took ownership of it to the point that by the 1850s they had two journals devoted to the form and bragged that American improvements had earned the daguerreotype the nickname “the American process.”

Sarah Kate Gillespie is curator of American art at the Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia. Her book The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology was published by MIT Press in 2016. Her next book, Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann, will accompany a 2018 exhibition on the photographer.

Sarah Kate Gillespie is curator of American art at the Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia. Her book The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology was published by MIT Press in 2016. Her next book, Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann, will accompany a 2018 exhibition on the photographer.

The post The Early American Daguerreotype appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 27, 2017

Five for Friday: The Witches of New York

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

I began writing The Witches of New York because I couldn’t stop daydreaming about the protagonist from my previous novel, The Virgin Cure. She had another story to tell, replete with witches and ghosts. I finished writing it because halfway through, I discovered there were “witches” in my family tree, including my nine times great aunt, Mary Ayer Parker who was hanged at Gallows Hill during the Salem witch trials. Women of the 19th century were still under threat of being labeled “witch” if they dared step outside the norms of society by being too intelligent, outspoken, radical, or different. (Not unlike the “nasty women” of today.)

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

I spent many happy hours sifting through the newspaper and image collections of the New York Public Library system and the New York Historical Society Library and Archives. I also read as many books on witchcraft in America as I could get my hands on as well as books on healing traditions and folk magic of the 19th century, chief among them, the scholarly works of historian Owen Davies.

As a result, a “big binder of witches” became my constant companion. Organized by topic—asylums, witchcraft, herbalism, tea superstitions, women’s suffrage, dream interpretation, demonology, Egyptomania, 19th century inventions, spiritualism, NYC landmarks—images, research materials, notes, character sketches, chapter outlines etc. All went into a large three-ring binder that I kept on my desk. I write first drafts by hand and tend to be a doodler, so having a place where I could deposit sticky notes and additional hand-written pages was the perfect fit for my writing process.

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

Finding the right balance between history, fiction and the fantastic. Although my previous novels contain elements of fairy tales and folk traditions, this is the first work I’ve written where ghosts, magic and questions about the afterlife play such large roles in the plot. Late-night conversations with friends and family about strange personal experiences and “things that can’t be explained,” helped bolster my resolve to not shy away from those things. In the end, I found that exploring the realm of the unknown while writing about specific historical events actually helped bring the tale into focus. It’s my hope that The Witches of New York does what all good fairytales do: immerse the reader in a world of magic to bring them closer to truth.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

There are several amazing connections between spiritualism in the 19th century and the suffrage movement. For example, Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for President of the United States, was also a practicing fortune-teller and clairvoyant. It was tempting to try to broaden the range of the book to include her story as well, but hers is a story that would’ve eclipsed the narrative of my witches in short order. While there are several nods to the suffragists of the 1800’s in the novel, Victoria didn’t make the cut.

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

Essie Fox, best known for her novels set in the Victorian era has recently entered the world of the silent film era with her novel, The Last Days of Leda Grey. I’ve always found her masterful ability to capture the setting, language and atmosphere of a chosen period to be both compelling and delightful.

Ami McKay’s debut novel, The Birth House was a # 1 bestseller in Canada, winner of three CBA Libris Awards, nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and a book club favourite around the world. Born and raised in Indiana, Ami now lives in Nova Scotia.

Ami McKay’s debut novel, The Birth House was a # 1 bestseller in Canada, winner of three CBA Libris Awards, nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and a book club favourite around the world. Born and raised in Indiana, Ami now lives in Nova Scotia.

The post Five for Friday: The Witches of New York appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 26, 2017

Divine Fat: Butter in Spiritual Mythology

A woman making butter, Paris 1499.

By Elaine Khosrova (Guest Contributor)

In modern times, butter has become a commodity that serves primarily a culinary purpose. But for many of our early ancestors, this dairy fat (and its derivative, ghee) also had another role—a sacred one. As a kind of metaphysical actor, butter stars in numerous religious mythologies and rituals created by civilizations long ago. These narratives were central to early man’s quest for existential meaning, if not answers. Because butter was often perceived as a divine mystery in itself (hidden in milk and temperamental to produce), it was naturally cast in many sacred liturgies.

Sumerian clay tablets from 2500 BCE, for instance, describe a well-established cult whose followers brought regular offerings of butter to their temple in order to satisfy the dairy desires of the goddess Inanna. Sumerian writings also reveal a reverence for the act of buttermaking, in passages like, “The rocking of the churn will sing for you, Inanna . . . thus making you joyous.”

Among the Vedic Aryans of the Indus River Valley, butter was a centerpiece of religious ritual. Throughout their Sanskrit texts from

500 BCE and earlier, we see butter referred to often and reverently. In one hymn dedicated to Agni, the fire god, a verse is recited while melted butter or ghee is used to feed tall flames: “ . . . these waves of Butter flow like gazelles before the hunter . . . Streams of Butter caress the burning wood. Agni, the fire, loves them and is satisfied.”

The Vedas formed the foundation of what would later constitute Hindu mythology, so it’s no surprise that butter and ghee figure in those stories as well. One classic tale features Vasuki, the Snake God, acting as a rope to spin Mandhara, a mythological mountain, like the plunger in a butter churn. Together they heroically churn an ocean of milk into blessed talismans and creatures. The story personifies the Hindu belief that butter/ghee is hidden in milk like the divine Lord is hidden in all creation; spiritual work and its rewards are symbolized by the hard job of churning.

One of the more popular narratives in Hindu mythology continues to be celebrated today. It describes the boyish mischief of Lord Krishna in his predilection for stealing ghee and yogurt (dahi) from the milkmaid’s hanging pots. (He is affectionately nicknamed makhan chor, the butter thief). Each year, during the festive commemoration of his birthday, known as Janmashtami, modern-day Hindus re-enact Krishna’s antics by hanging pots of yogurt and ghee atop street poles and forming human pyramids to reach them. It’s all done for fun, though the playful metaphor is nonetheless profound: Higher purpose rewards us with a rich spiritual life.

Elaine Khosrova is an award-winning food writer and editor, and the author of Butter, A Rich History, published in 2016 by Algonquin Books. She continues to hunt down butter’s cultural stories, past and present, and welcomes any leads at @butterdishing

Elaine Khosrova is an award-winning food writer and editor, and the author of Butter, A Rich History, published in 2016 by Algonquin Books. She continues to hunt down butter’s cultural stories, past and present, and welcomes any leads at @butterdishing

The post Divine Fat: Butter in Spiritual Mythology appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 25, 2017

Robinson Crusoe as a Woman

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Robinson Crusoe, shipwrecked traveler and solitary survivor, has always been regarded as a manly figure. The first thing he does on his island is build a fort, and he is the ultimate handyman, always inventing ways to construct and use new tools that enable him to survive and prosper. There aren’t any women on Robinson Crusoe’s island. The novel was immediately associated with new approaches to forming the characters of young men based on the principles of nature. Rousseau declared that an entire boyhood education could be derived from reading Defoe’s novel alone.

Robinson Crusoe, shipwrecked traveler and solitary survivor, has always been regarded as a manly figure. The first thing he does on his island is build a fort, and he is the ultimate handyman, always inventing ways to construct and use new tools that enable him to survive and prosper. There aren’t any women on Robinson Crusoe’s island. The novel was immediately associated with new approaches to forming the characters of young men based on the principles of nature. Rousseau declared that an entire boyhood education could be derived from reading Defoe’s novel alone.

Soon after its publication in 1719, the story started generating imitations. Among these is an interesting assortment of stories published in the late 18th century by women writers, portraying the castaway as a woman, and broadening the shipwreck narrative to include varied circumstances and new types of adventurers. A common feature in all of these stories re-gendering Robinson Crusoe is that the female characters are not alone. They embark on their adventure with friends, sisters, lovers, or husbands. When the castaways do find themselves alone or abandoned, they seek out new contacts – with indiginous people or with other lost travelers who are washed up on shore. The Robinson Crusoe adventure becomes for them a way of creating new types of community. Female ‘Robinsons’ are preoccupied not only with building forts, they also focus almost immediately on finding entertainment, making music, telling stories, and building ovens for cooking.

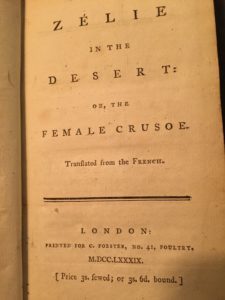

One of the most curious is a little known French novel by Marguerite Daubenton, published in 1786. She called it Zélie dans le désert. The narrator is a young noblewoman who embarks on a ship sailing for Batavia along with a female friend named Nina. Both women are fleeing their families who are opposed to the marriages that they want. Among the other passengers on the ship is Zélie’s lover Ermancour. Nina is in the most difficult position – she is alone, and she is pregnant.

One of the most curious is a little known French novel by Marguerite Daubenton, published in 1786. She called it Zélie dans le désert. The narrator is a young noblewoman who embarks on a ship sailing for Batavia along with a female friend named Nina. Both women are fleeing their families who are opposed to the marriages that they want. Among the other passengers on the ship is Zélie’s lover Ermancour. Nina is in the most difficult position – she is alone, and she is pregnant.

The ship is wrecked off a remote island, inhabited only by a solitary, bearded old man who himself had been castaway on the island 20 years before. He takes the women in, providing them with essential items like new dresses that he had saved from the wardrobe of his deceased wife. He also tells them stories and writes a book describing all he had learned about surviving in the wilderness. Nina gives birth and dies, leaving the baby Ninette in the care of her friend. Ninette will grow up to be a free-spirited girl, a child of nature, free of the constraints that her mother and friend had fled in Europe.

This tale of shipwreck and adventure seems to refer to Defoe’s version, with a difference: The old Crusoe-like man is thrilled to find a family and pass on his wisdom before he dies. And when Zélie sees a footprint in the sand, it does not turn out to be that of a man who will become her servant, like Friday for Robinson Crusoe. Instead, it is the footprint of Ermancour, her lover who had been thought to be drowned. Together the new family of cast-out castaways goes into the forest to look not just for tools and food but for “beautiful, useful, and agreeable objects.” Ermancour builds not a fort but a more fanciful structure, “as beautiful as an opera stage.”

The story is long! And the plot takes many more twists and turns. It was popular enough to be translated into English almost immediately. In the English title, there is an added phrase: Zélie in the desert, or, the Female Crusoe.

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

The post Robinson Crusoe as a Woman appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 23, 2017

Mud Mosques

By Pamela D. Toler (Regular Contributor)

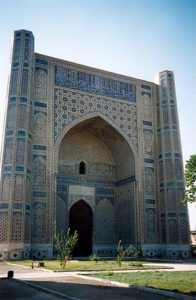

The Bibi Khanym of Samarkand

Unlike the classic blue-tiled mosques of the Middle East, the mosques of West Africa are made from mud brick. That doesn’t mean they are simple mud huts. They are complicate and beautiful buildings that combine traditional West African building techniques with the ritual requirements of Islamic worship to make uniquely West African religious spaces.

The Great Mosque at Djenne

The most famous West African mosque is the Great Mosque of Djenne, in central Mali. A mosque has occupied the site since 1240, when the city’s twenty-seventh ruler, Koy Kumboro, converted to Islam. In order to show his devotion to his new faith, he demolished his palace, and built a mosque in its place. The new mosque was built over a frame of palm timbers using cylindrical sun-dried bricks, about the size and shape of a can of soda pop, and then plastered with a layer of mud. According to Mali legend, the local djinn help build it by carrying clay from the desert in baskets on their heads.

Koy Kunboro’s mosque dominated the market plaza at the center of Djenne for almost six hundred years. In the early nineteenth century, fundamentalist leader Seku Amadou declared jihad against Djenne in the name of restoring Islam to its true nature. After he captured the city, he abandoned the mosque to the weather. Islamic law forbids the destruction of a mosque, but mud buildings are fragile. Without regular maintenance, the Great Mosque crumbled into ruins.

In 1907, masons skilled in the traditional techniques of mud construction rebuilt the mosque under French rule. Like Notre Dame in Paris, the re-built Great Mosque combines monumentality with verticality. The mosque stands on a raised square plinth and dominates the city’s main market square. The major facade, which faces the market, consists of three stepped minarets divided by a series of sharply defined vertical columns. This facade is not the entrance. It is the qibla, which points the way to Mecca.

The oldest sections of the mosque are made from cylindrical bricks about the size of a can of soda pop; the bricks in the newer sections are rectangular. The building bristles with projecting fan palm timbers, set horizontally into the walls as expansion joints to reduce cracking caused by extreme changes in humidity and temperature.

The timbers also provide permanent scaffolding for the ongoing maintenance required by mud construction. Djenne is taking no chances on losing the Great Mosque to the weather again. Re-plastering the walls after the inevitable damage caused by the rainy season is now an important element of the local Ramadan festival.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Find Pamela on Twitter at @pdtoler

Read more of her writing on her personal blog

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

The post Mud Mosques appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 20, 2017

Five for Friday: Eva Stachniak’s THE CHOSEN MAIDEN

Interview with Eva Stachniak

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

The Chosen Maiden was born out of my fascination with Ballets Russes, a Russian dance company which, in the summer of 1909, took Paris by storm. Bronislava (Bronia) Nijinska –the intended Chosen Maiden from the 1913 production of The Rite of Spring choreographed by her famous brother Vaslav–was my inspiration. A brilliant dancer and a ground-breaking choreographer, herself, Bronia lived a life fuelled by art and made possible by the fierce loyalty of the Nijinsky women who stood by each other through thick and thin. The Chosen Maiden is what I like to call an archival fantasy, a historical novel weaved together from facts and imagination, an intimate portrait of a woman whose art and life helped to define what it means to be modern.

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

Bronislava Nijinska died in California in 1972 leaving behind rich personal archives. Her papers–160 boxes of them–found their way to the National Library of Congress. This is where I spent long hours reading diaries, notes, letters, as well as looking at hundreds of personal snapshots Bronia took of her family and friends. To organize this material I turned to my favourite writing tool, Scrivener, which lets me keep all related files in one project and organize them into clearly distinguished and easily accessible categories. When I finally began to write, these notes contained all I needed: descriptions of historical characters and places related to the story, details of dances and performances featured in the novel, as well as images which guided me through the most important moments of the story.

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

I have to confess that the richness of the archival material was both a blessing and a curse. After all I was not writing a biography of a famous choreographer but a novel. In order to hear the voices of my fictional characters I had to forcibly step away from all the material I have collected, let my own vision emerge. This took time and confidence which I gained by interviewing contemporary dancers and getting to understand the way they see the world. In the end–after several drafts– I struck the right note: true to the recorded facts, but also free to express my own understanding of Bronia’s story and its meaning.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

The story of Olga Kokhlova, Picasso’s first wife. Olga was a Ballets Russes dancer, one of Bronia Nijinska’s closest friends from before World War I. The story of that early friendship belonged to the novel, but I soon found myself writing long passages about Olga’s troubled and often tragic relationship with Picasso. It took me quite some time to admit that, however compelling, this relationship was not relevant to Bronia’s own story, and had to go.

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why?

Ami McKay writes historical fiction which blends together fantasy, magic realism and meticulous research. Ami’s inspiration are unconventional women who find their strength in female solidarity. Her latest novel, The Witches of New York, has just been published and I would like to hear her answers to the questions I have just answered.

Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

Eva Stachniak is the award-winning and internationally bestselling author. She holds a PhD in literature from McGill University. Born and raised in Poland, she moved to Canada in 1981, and lives in Toronto. The Chosen Maiden is her fifth novel.

Eva Stachniak is the award-winning and internationally bestselling author. She holds a PhD in literature from McGill University. Born and raised in Poland, she moved to Canada in 1981, and lives in Toronto. The Chosen Maiden is her fifth novel.

The post Five for Friday: Eva Stachniak’s THE CHOSEN MAIDEN appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.