Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1265

August 7, 2015

A 6-Part Structure for Giving Clear and Actionable Feedback

Robert was the head of an East Coast insurance company. His greatest asset was his large, extroverted personality. He was the classic glad-handing, backslapping, high-energy salesman. His problem was a familiar one, too: a great salesman – even one with charisma — doesn’t necessarily make a great leader.

After receiving some 360-degree feedback, we met to discuss the data. He’d received low scores on providing clear goals and direction, indicating a chaotic management style. His challenge, as I saw it, was twofold: he had to change himself and his environment simultaneously — which meant aligning his team’s behavior with his own.

In my years of executive coaching and research about behavioral change, I have learned one key lesson, which has near-universal applicability: We do not get better without structure. Structure is a major contributor to successful behavioral change, whether you’re trying to change your own behavior, or your team’s. When either asking for or providing feedback, structure can make the process a positive encounter for both parties.

I had a simple off-the-shelf structure for Robert that had worked with clients many times before. It took the form of six basic questions he would discuss during a bimonthly (every other month) one-on-one meeting with each of his nine direct reports. The agenda for each meeting was a sheet of paper with the six following questions:

Where are we going?

Where are you going?

What is going well?

Where can we improve?

How can I help you?

How can you help me?

Where are we going? This question tackled the big-picture priorities at the company. It forced Robert to articulate what he wanted for the company and what he was expecting from the executive. Answering this question, Robert described a vision that could be discussed openly, not merely guessed at. The back-and-forth dialogue was a first step in changing both the environment and Robert’s reputation.

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Communication

Communication Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Where are you going? Robert then shifted to his view of where each executive should be going. Then he turned the table and asked each person to answer the same question, thus aligning their behavior and mindset with his. In short order, they were replicating Robert’s candor and honesty about their responsibilities and goals.

What is going well? Bad as he was at setting clear goals, Robert scored almost as low at providing constructive feedback. No meetings, no opportunities to praise his superstars. So the third portion of every meeting required him to openly recognize recent achievements by the executive facing him. Then he asked a question seldom asked by leaders: “What do you think that you and your part of the organization are doing well?” This wasn’t just a compulsory upbeat moment in a meeting. It helped Robert learn about good news that he may otherwise have missed.

Where can we improve? This forced Robert to give his direct reports constructive suggestions for the future — something he’d rarely done and that his people didn’t expect from him. Then he added a challenge: “If you were your own coach, what would you suggest for yourself?” The ideas he heard amazed him, largely because they were often better than his suggestions. He was okay with that. He was not only shaping the world around him, he was learning from it.

How can I help? This is the most welcome phrase in any leader’s repertoire. We can never say it enough, whether we’re in the role of a parent or friend — or a busy CEO running a meeting. It has a reciprocal power few of us take advantage of. When we offer our help, we are nudging people to admit they need help. We are adding needed value, not interfering or imposing. That’s what Robert was going for: building alignment between everyone’s interests.

How can I become a more effective leader? Asking for help means exposing our weaknesses and vulnerabilities — not an easy thing to do. Robert wanted to be a role model CEO. By asking for ongoing help and focusing on his own improvement, he was encouraging everyone to do the same.

The improvements at Robert’s company didn’t happen overnight. But they never would have happened without some sort of structure. This simple list of questions played to Robert’s strength. He had always been a great communicator with customers. Now he was deploying the same skill with employees.

In hindsight, the structure’s biggest impact may have been to slow Robert down. Instead of always being on the go, he had to carve out serious time in his calendar for nine one-on-one meetings every two months.

Another key element in Robert’s process was not just what he did every other month, but what each of his directs reports did in between the bi-monthly sessions. Robert involved his team in his own transformation toward becoming a better leader. Robert gave each team member carte blanche to call him on any leadership failing, to take personal responsibility for immediately contacting Robert if he or she felt confusion or ambiguity on direction, coaching, or feedback. Robert changed himself and his environment. Robert added structure. The team assumed responsibility. The combination produced amazing results.

When Robert retired four years later, his final 360-degree feedback report put him in the 98th percentile on “Provides clear goals and direction.” What most amazed Robert was all the time he saved. He summed up: “I spent less time with my people when I was rated a 98 than I did when I was rated an 8. In the beginning, my team couldn’t tell the difference between social chitchat and goal clarity. By involving them in a simple structure, I could give them what they needed from me in a way that respected their time and mine.”

That’s an added value of matching structure with our desire to change. Structure not only increases our chance of success, it makes us more efficient at it.

Why Sales Teams Should Reexamine Territory Design

Companies are using more analytics to enable better sales force decisions, yet one area that is still too frequently undervalued is sales territory design, or the way in which the responsibility for accounts is assigned to salespeople or sales teams.

The distribution of customer workload and opportunity across the sales force has a direct impact on salespeople’s ability to meet customer needs, realize opportunities, and achieve sales goals. Our research shows that optimizing territory design can increase sales by 2 to 7%, without any change in total resources or sales strategy.

So why do companies so often underestimate the value of territory design? Quite often, the symptoms of poor design are misdiagnosed and attributed to other causes. For example:

1. Is the sales force targeting the wrong accounts? If a sales force has some salespeople who don’t follow up on good leads, and others who spend too much time with low-potential prospects, it could be that salespeople can benefit from better targeting data and coaching. But it could also be the symptom of a territory design issue. If some salespeople don’t have enough good accounts to stay fully busy, they may over-cover low-potential prospects. And if other salespeople have too many accounts, they will ignore good leads because they are too busy to follow up and can make their quota by focusing on “easy” accounts. The solution to better targeting may be to redistribute account workload more equitably among salespeople.

2. Is there a hiring and retention problem? If there is constant turnover of salespeople in a particular sales territory, it could suggest a need to improve the hiring process or the programs for developing and retaining salespeople. But high turnover in select territories could also be the symptom of a territory design problem. Salespeople could be leaving because they don’t have enough opportunity in their assigned accounts. There is a strong correlation between sales and opportunity; typically much stronger than the correlation between sales and factors reflecting salesperson effort and ability. Salespeople who have too little opportunity will quickly become discouraged, especially if they see other salespeople making lots of easy money milking territories with many large-opportunity accounts. By giving more accounts to salespeople who have low opportunity, those salespeople have a greater chance of generating sales and being successful. This could address a retention problem.

3. Is something wrong with the incentive compensation plan? If the same salespeople consistently get the highest incentive pay, even though other salespeople work harder and/or have stronger capabilities, it could suggest a need to change the incentive plan. But the situation could also be a symptom of unfair territory design. If opportunity is not equitably distributed among salespeople, the metrics that are commonly used as the basis for determining incentive pay (e.g. sales or market share), are likely impacted by the territory more so than by the salesperson. For example, a sales metric favors salespeople with many large-opportunity accounts, while a market share metric favors those with a smaller base of opportunity and fewer accounts. A change in territory design that gives salespeople more equitable opportunity increases the odds that such metrics will reflect true performance differences, leading to fairer incentive pay and a more motivated sales force. Better territory design also enables improved selection of salespeople for rewards and recognitions such as President’s Club, while reinforcing a “pay for performance” culture.

Sales forces that have not recently evaluated and adapted their territory design to current business needs likely have misalignments that are keeping the sales force from achieving maximum effectiveness. In today’s dynamic marketplace, many factors can cause alignments to get out of synch, including a new product launch, entry into a new market, a revised company strategy, and a new sales force size or structure. To stay current with market needs, alignments need to be re-evaluated at a minimum every two years.

Fortunately, today’s data-rich environment provides access to all kinds of information for helping sales forces address the problem. A first step is creating a database that captures profitable account workload. Then, by analyzing that data by salesperson, it’s possible to identify territories with gaps in customer coverage, as well as territories where sales talent is underutilized. Using a structured territory design process and mapping software, local sales managers can make informed account reassignment decisions that close coverage gaps and better utilize sales talent. In the end, more customers get the attention they deserve, salespeople all get a fair challenge, and it becomes easier to identify and reward the true top performers.

There is no longer any reason that companies should undervalue territory design as a key driver of sales force productivity and performance.

Stop Using Employee Friendships to Measure Engagement

Here’s a question that has been touted by human resources consultants and practitioners for the better part of two decades as an important way to measure employee engagement: “Do you have a best friend at work?” While a principal of the polling organization Gallup, I prominently defended and helped popularize the concept.

But, over the past half-decade, I’ve grown increasingly skeptical about the utility of “best friend” metrics. First, because I believe organizations are incapable of manufacturing or improving such intimate personal connections and, second, because subsequent research has shown other (more easily influenced) factors to be more important drivers of engagement and performance.

Should businesses care if their employees have healthy relationships? Sure. They serve as a source of positive emotion and support and can enhance productivity. Should they get involved in them? No. Friendships, by their very nature, arise naturally, not as part of a corporate initiative. Team-building exercises can, of course, allow people to get to know each other better, enhancing cohesion and understanding. But they don’t make everyone friends. No amount of organizational orchestration can foster those more personal bonds.

What’s more, according to our data, friendship ranks well below collaboration, teamwork, and coworker abilities for maintaining employee commitment and intensity. In fact, when all four of these issues are analyzed together relative to employees’ commitment to the company and intensity on the job, the effect of friendships is so weak it sometimes is not even statistically significant. The data say clearly: “If you want the most from me, give me talented colleagues and some key collaborators, and give us conditions that foster teamwork. If we become friends, that’s great, but not crucial.”

The reason is simple: While friends might make you happy, teammates help you get things done. In a head-to-head match-up between the statements “I have good friends at my current job” and “I have many strong working relationships at my job,” the latter is a much better predictor of employees’ customer focus, innovative thinking, motivation to work hard, pride in their organizations and intention to stay in their jobs.

So if you’re a leader (or a pollster) looking to measure and boost engagement on your team and in your company, forget about friendship. Instead, concentrate on the aspects of work more powerful for performance today: individuality, pay fairness, transparency, meaning, future prospects, leadership opportunities, recognition, corporate culture, freedom from fear, teamwork, and personal accomplishment. Rather than inquiring about “best friends,” decision-makers should ask questions such as:

Do managers support each employee as a unique individual?

Is pay fair, if not generous?

Are leaders transparent?

Is there a clear mission and do employees feel a strong connection to it?

What paths do people have to advancement?

Do more junior people sometimes get to take charge?

Are employees well recognized?

Is this a cool place to work?

Do people feel energized or fearful?

How well do colleagues work together?

How often do people feel a sense of accomplishment?

We’ve found that the answers to these questions are not only highly correlated to strong engagement and performance, they’re also ones that you have the power to control. Each is well within the company’s jurisdiction — subject to the quality of leadership and managing — and not personally intrusive. No employee will balk about whether issues such as pay, work/life balance, or unified team objectives are part of a company strategy session. And should the job come to an end, no one expects those aspects to continue in the same way as would a friendship, which — it turns out — really wasn’t all that important to the business anyway.

August 6, 2015

How to Manage People Who Are Smarter than You

The best managers hire smart people to work for them. But what if your direct reports are smarter than you? How do you manage people who have more experience or more knowledge? How do you coach them if you don’t have the same level of expertise?

What the Experts Say

Getting promoted to a job that includes responsibility for areas outside your domain can be downright terrifying. Your employees may ask questions that you don’t know the answers to and may not even fully understand. “When you’re a technical expert, you know your value to the organization,” says Wanda Wallace, President and CEO of Leadership Forum and author of Reaching the Top. “But when you don’t have the content expertise—or the ‘best’ content expertise, you struggle with: what is my value?” Figuring out the answer to that question requires a change in mindset. “Your role is no longer to be an individual contributor,” says Linda Hill, a professor at Harvard Business School and the coauthor of Being the Boss. “Your job is to set the stage and by definition that means you will have people who are more experienced, more up-to-date, and have more expertise working under you.” And while it may feel professionally disconcerting at first, it bodes well for your future. “The higher you go in an organization, the more you’re expected to make decisions on which you might not have direct experience or expertise,” says Roger Schwarz, an organizational psychologist and the author of Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams. “It’s a beginning of the shift in your career.” Here are some tips on how to make that transition as seamlessly as possible.

Face your fears

It’s natural to feel worried or insecure about your ability to manage someone who has superior experience or knowhow. “Business is emotional,” says Wallace. “And when you’re leading a group that knows more about the day-to-day work than you do, it’s scary.” According to Schwarz, the first step is to consider whether your fear is based in reality. “If no one has said anything to you directly or indirectly, you need to look deeper and ask yourself: where is this fear coming from?” Hill agrees, adding that it can be dangerous to ignore self-doubt. For one thing, “if you feel threatened, other people will pick up on those signals.” For another, “if you don’t feel comfortable coaching someone who has more experience than you, you might end up neglecting that person.”

Seek counsel

Consider reaching out to other managers who may have experienced similar challenges. “Talking to peers, coaches, and mentors about your feelings and fears of inadequacy” will help you feel less alone and may also give you ideas on how to handle the situation, says Wallace. A candid conversation with your manager might also be worthwhile, according to Schwarz. “Share your concerns and ask what led him or her to select you for the role and what you bring to it,” he says. This isn’t “fishing for compliments,” he adds. “There’s nothing wrong with asking for reassurance,” and the answers “will give you insight into your strengths and the development needs of your reports.”

Get informed

In yesterday’s organization, the boss was the teacher and the employees were there to learn and do as they were told. Today, “learning is a two-way street,” says Schwarz. Tell your direct reports that you want to learn from them and then be deliberate about “creating opportunities to make that happen,” he says. “You don’t need to become a technical expert, but you do need to know enough about the details to know where the problems lie,” adds Wallace. She suggests shadowing team members for a day or even for a couple of hours and “asking a lot of dumb questions.” Find out what worries them, where they get stuck, and from whom they could use input. “Get insight into what your people do,” she says. “It’s enormously motivating for employees.”

Confront any issues

If members of your team express concerns about your ability to lead, or you hear that the office rumor mill churning with spite, you need to address the issue head on. When dealing with a direct report who is openly hostile or out for your job, you should be honest and “willing to be vulnerable,” according to Schwarz. He recommends saying something like, “I know you have more experience and expertise than I do, and I understand you have concerns about that.” Don’t go in “trying to protect your ego.” Instead, approach the person with curiosity and talk “about what you can do to help meet his needs.” Remember, Hill adds, your goal is to “figure out how you’re going to work together and support your employee.”

Give—and take—feedback

“It’s rather foolish to think about giving feedback” on your direct reports’ area of expertise when you don’t have the technical chops to do so, says Wallace. So keep your comments to areas where you have authority and legitimacy,” she says. “Find the issue that’s most relevant and be specific. Say: ‘I want to talk with you about the way you communicate with the sales team.’ Give an example, talk about what happened, and the result,” she says. But make sure to get as much as you give, adds Hill. “You need to make it clear that you’re also comfortable getting feedback,” she says. “This is the way you’ll all get better.”

Add value

Perhaps the best way to gain credibility and trust as a manager is to demonstrate “the value you add to the team,” says Wallace. It could be in “how you bring people together, how you use your network to get work done, how you communicate with stakeholders, or the broader perspective” you provide. Hill says you should also show a desire to help your employees advance in their careers. She suggests asking questions like, “Where do you want to go? What do you want to learn? And what do you need from me?” Schwarz adds: “You don’t need to be the person’s mentor, but you need to help the person develop.”

Give employees room

As the leader, one of your most important responsibilities is to “create an environment for talent to be expressed,” says Hill. This requires you learn how to step back and enable things to happen. “Your role is not to be the smartest person in the room anymore. Your role is to make space,” she says. Wallace agrees. “Keep your hand hovering over the team”—like a parent helping a toddler learn how to walk, she says. “Be there, but don’t hold her hand all the time.” Transparency is key. “Get smart about what you need to know and how often you need updates,” Wallace adds. Tell your team when you need to give senior leaders a progress report, “When direct reports know why you’re digging into details, they are tolerant. But when no explanation is provided, it leads to a feeling of ‘do you not trust me?’”

Project confidence, but not too much

Even if it sometimes feels as if you’re in over your head, it’s important to project the right amount of confidence. But “there’s a balance,” Wallace says. “If you come across as overconfident, your people won’t trust you” and you’ll be viewed as arrogant. “Equally, if you look scared to death you won’t be seen as credible.” Executive presence is something you must cultivate. There’s no secret sauce: Be calm. Be respectful. Take yourself and others seriously. Know when detail is necessary and when it’s not. “When your team sees you holding your own among other senior leaders they will give you credit.”

Principles to Remember:

Do

Talk to your manager about the attributes you bring to your role

Find a way to add value to your team and help employees advance their careers

Step back and enable employees to do their jobs without meddling too much

Don’t

Ignore feelings of insecurity; confront your negative emotions and seek advice on how to deal with them

Feel threatened by your direct report’s specialized knowledge; instead seek opportunities to learn from him

Be arrogant; if you come across as overconfident, your team won’t trust you

Case Study #1: Get educated about what your direct reports do

Earlier this year, Emily Burns, founder and CEO of Learnivore, the Boston-based start-up that helps people find local instructors, coaches, and classes, set out to hire a chief technology officer.

Her ideal candidate needed to have topnotch development skills, be conversant in multiple programming languages, and have a deep understanding of emergent web technologies . In short, Emily needed someone with knowledge and capabilities that she herself didn’t possess. “The hardest part about hiring people who have expertise you don’t have is evaluating them,” she says. “I realized I needed to get educated enough about what they do.”

So Emily did lots of reading; she talked to others in the industry and learned about the cadence of development. “I learned how to gauge the quality of the work product even if I can’t do the work myself,” she says. “I learned how long it takes to do things, what’s doable, and what’s not.”

This research had two advantages: One, it made the hiring process go more smoothly and, two, it has helped Emily manage Heather, her new CTO. Emily articulates a vision for “what success looks like” to Heather but stops short of blow-by-blow instructions on how to achieve it. “I understand our application architecture at a high level and I can communicate to my CTO what I need done, but how it gets done is up to her,” she says.

Today Emily and Heather are working together to put the company in the best position for possible venture funding. They’ve identified metrics they need to bolster and new features they want to add. “Heather understands the overall business reasons why we need to do these things; she’s always finding ways to make our technology perform better, and she often has an idea that will save us time or money,” Emily says. “If you know how to do somebody’s job, you tell them how to do it. But when you don’t, you have to listen and be receptive.”

Case Study #2: Provide your team members with resources and support

Early in Meredith Haberfeld’s career, she was made vice president of a marketing services company and put in charge of a large team full of people who were “more experienced and more capable” than her. “They understood how to build a business better than I did,” she recalls.

Meredith suffered a crisis of confidence: “I thought: how could I lead these people? What value did I provide?”

A conversation with a mentor helped change her perspective. The mentor reminded Meredith that she was put in the job for a reason: the company’s higher-ups believed she had something to offer. Her mentor also emphasized that a manager’s role was not to do the job of his or her employees, but to help them do better at their work. “My job was to look for things that they didn’t see and help them shine brighter,” Meredith explains. “She also told me that my insecurity would only get in my way, so I had to stop worrying about them outshining me.”

From that point on, Meredith focused on providing “vision, direction, and strategy,” she says. “I made sure my team had everything they needed to thrive.”

Determined to develop and maintain strong relationships with her team members, she gave them lots of leeway. She trusted their experience and expertise and didn’t worry about how they got their jobs done. “I made people accountable for their results, not their activity, and I gave them a huge amount of room to deliver,” she says.

She also showed humility. When her direct reports asked her questions she didn’t know the answers to, she “was shameless about finding people who did—whether they were people within the company or outside of it.” And she made sure to give them credit for their results. “Sharing public glory was really important,” she says. “It showed that I was not looking to be the hero or the expert.”

Four years into her job, the company was sold for over $200 million to a public entity. Today Meredith is the founder and CEO of ThinkHuman, the career-coaching group and management consultancy. “I look back on those years as my on-the-court MBA,” she says.

What Angel Investors Value Most When Choosing What to Fund

Steven Moore

Despite all the media attention venture capital gets, it’s far from the most common source of startup funding. As Diane Mulcahy explained in a 2013 Harvard Business Review article: ”Angel investors — affluent individuals who invest smaller amounts of capital at an earlier stage than VCs do — fund more than 16 times as many companies as VCs do,” she wrote, “and their share is growing.”

Last year total U.S. angel investments ran to $24.1 billion, according to the Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire. More than 73,000 ventures received angel funding, and there were 316,000 active investors. Yet for how substantial the market is, there’s relatively little data on the decision making process of those who invest in early stage startups.

As a result, we’re stuck with the question of how investors choose which startups to fund. It’s hard to predict whether a novel idea will succeed, and these fledgling firms typically have no financial track record or tangible assets. So Shai Bernstein, an assistant professor of finance at Stanford’s GSB, and Arthur Korteweg of USC’s Marshall School of Business devised an experiment to identify what characteristics do distinguish startups. They partnered with Kevin Laws, the founder of AngelList, and used his platform to measure investors’ initial screening process. In a recent working paper, “Attracting Early Stage Investors: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment,” they report their findings: the average investor responds strongly to the founding team, but not so much to the startup’s traction (its sales or user base) or existing investors.

This probably isn’t much of a surprise. In fact, the importance of founders has been emphasized in these pages before. Nearly 20 years ago, William A. Sahlman argued that most business plans wasted too much ink on numbers, not paying sufficient attention to the information that really matters to investors: people. “When I receive a business plan, I always read the resume section first,” he wrote. “Not because the people part of the new venture is the most important, but because without the right team, none of the other parts really matters.”

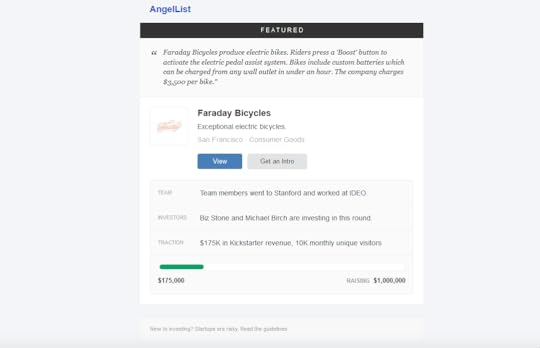

Now, Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws have the evidence to back this up. AngelList regularly sends emails (shown below) highlighting “featured” startups to investors on the platform. These are firms that AngelList’s algorithm matches to investors who have already noted interest in the firms’ industry or location. The email describes the startup’s idea and funding goal, as well as its founding team, traction, and current investors — but the latter three categories only appear if they pass a certain threshold defined by AngelList’s algorithm. To investors, this signals high quality; seeing one of these in the email means that it’s worth paying attention to. So for example, the founders would only be listed if they went to a top university like Harvard or Stanford or previously worked at a Google or PayPal. Investors respond by clicking “View,” which brings them to the company’s full AngelList profile, or “Get an Intro,” which sends the company an introduction request — or they withhold their click and pass on the company.

Note: This email is just an example, and this company did not participate in the experiment.

The researchers randomly choose which categories would appear in the email to alter the perceived quality of the startup’s team, traction, and current investors. So say one company’s team and traction passed AngelList’s threshold; they would create three emails: one that only listed the team, one that only described the traction, and one that showed both. (The idea and funding goal were always visible, and they never excluded all categories from an email.) If AngelList was planning to send that company to a community of 1,500 investors interested in biotech, the researchers would randomly send 500 of them the email showing the team, while another 500 would see traction, and the other 500 got the control email displaying both.

The experiment ran for eight weeks in the summer of 2013, and spanned 21 startups, 4,494 investors, and nearly 17,000 emails. They found that information about the founding team raised investors’ click rate by 2.2% (average investors’ probability to click is 16%, so in relative terms, founding team information increased the click rates by almost 14%, which is economically important), whereas knowing that the startup had material traction or notable investors did not significantly make investors more likely to click. And these clicks are meaningful — they capture the investors’ level of interest in the startup, which affects funding decisions.

This suggests that a startup’s human capital is uniquely important to potential investors. However, Berstein said they’re not arguing that the team is more important than the idea, since their setting didn’t allow that comparison. Rather, they found that conditional on the idea, the team is quite important — more so than the product’s initial traction and ability to attract earlier investors.

The authors have two hypotheses for why the founding team is so highly valued. The first, they wrote, is that “operational capabilities of the founding team may be important at the earliest stages of a start-up, when most experimentation takes place.” The second, and this is where it gets more speculative, is best explained with an example: “Say we have a team that graduated from HBS. They have many opportunities they could pursue, but the fact that they decided to pursue the startup, and not go work for another venture, signals that this is a really good idea and a very promising venture,” Bernstein told me. He said that they found supportive evidence of the first hypothesis, but they do not rule out the existence of the second.

But does investing based on the founding team work? The researchers couldn’t answer this directly, since these were still very early-stage companies and they didn’t have information about long-term performance. However, when they distinguished between investors’ experience levels, they found that the more experienced and successful investors (measured by their number of prior investments) only responded to information about the team, while the least experienced responded to all three categories. Because the former is more likely to invest in successful startups, the authors said, this offers indirect evidence that selecting based on the founding team is a viable investment strategy.

Angel investors sort through thousands of startups vying for funding, each promising the next big breakthrough. This experiment illustrates how they use various cues to filter their pipeline — and how founders significantly influence their decisions to invest. The formula for long-term success may be different, though, when you consider how founders are often replaced, for various reasons, before the startup’s IPO. “What we find suggests that at the very early stages, at which the startup is still experimenting and trying to find the right business model, the founders are very important. Maybe later on, when the company is on track and growing to a larger scale, the founder becomes less important,” Bernstein said. “But our evidence suggests that at least at the very early stages, investors seem to think tremendously about the team and the founders.”

Making Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Business Combinations Work

When you look to external partners for acquiring resources and capabilities, your organization needs a practical roadmap to answer some critical questions: What kind of partners and business combinations do we need? How will we manage them over time? What profits will we earn, and will they justify our investment? The following excerpt from Remix Strategy: The Three Laws of Business Combinations offers a simple, but powerful, framework to help you make those decisions.

Business is being turned outside-in. Acquisitions, mergers, joint ventures, alliances, partnerships, and other business combinations are no longer exceptions for most firms — they have become central to gaining competitive advantage. This combining of assets, capabilities, markets, and talent pools to create new value is what I call remix strategy — and it is critical today to do this remix right.

Most likely, you have considered one or several remixes for your business. The key strategic questions you face are not whether combinations such as these are necessary but, rather, how will they create value, and how are you going to capture that value? How are these ventures going to enhance your competitive position? Whether you are at the top of the company driving the remix, in the middle managing an acquisition or a partnership, or among the operating ranks keeping the pieces humming, you need to know the answers to such questions.

In my work with executives, I’ve noticed a distinct gap in their toolkits. Managers already have a great deal of information and best practices for implementing alliances and acquisitions. The strength of these playbooks is their concrete detail about the legal, managerial, and financial ins and outs of every deal type and the tips on how to manage people and cultures in these combinations on a day-to-day basis. But managers lack a set of guiding principles for actually making the deal create value for the company. Based on my 30 years of consulting, teaching, and academic research on partnership strategy, I have created a simple but powerful framework to help executives see clearly the key decisions that drive value creation and capture, and then to navigate those decisions successfully. I call these guiding principles the three laws of business combinations.

The Three Laws of Business Combinations

Successful business combinations — those that turn out to be a profitable use of resources — all follow the three laws. These laws are not formulated as commandments or orders, but are necessary conditions for success. All business combinations must have the potential to create joint value, must be governed to realize this value, and must share value in a way that provides a reward to each party’s investment. Each law points to a set of practical implications:

First law: The combination must have the potential to create more value than the parties can alone. The first law asks these practical questions: How much more value can we create in the market together? What specific resources must we combine to create this value?

Second law: The combination must be designed and managed to realize the joint value. Which partners and structures fit this goal best? How do we manage the risk and uncertainty inherent in such combinations?

Third law: The value earned by the parties must motivate them to contribute to the combination. How do we divide the joint value created? How will value be shared over time?

Taken together, the laws provide a powerful, systematic approach for creating and capturing value from your partnerships—from when to form a combination, to how to manage collaboration, to how to ensure that you get a return on your efforts.

These three laws determine the success of any business combination, and at first glance, they’re easy to grasp. But each is deeper than it looks. And living by them is tricky in practice. Often, one or the other gets short shrift in the rush to strike a deal or gets lost in the glare of a promising future. Another practical problem is that because each law revolves around a different school of thought in strategy and management science, experts in one area can easily miss cues in another and, in doing so, inadvertently plant the seeds for a costly retreat later on. To avoid these pitfalls, we will need to dig deeper into each one of the laws:.

First Law: Identify Potential Joint Value

In casual conversation, the idea of creating value in combinations is often expressed as 1 + 1 = 3, or some such mathematical metaphor. In fact, that isn’t a crazy way to think about the three laws.

As explained, the first law for a business combination is that the remix must have the potential to create more value than the resources can generate when governed separately, that is, without being combined. In common business language, the combination has to produce synergy. I hesitate to use that term because of its reputation as a business buzzword. But the bad rep comes from ignoring the complex processes involved in creating value in combinations. To actually produce synergy and achieve real results, you need to pay attention to all three laws.

For example, how much more value is created by the combination? In our metaphorical formula, the extra value is 50% (3 is 50% greater than 2). But in a real situation, what is the actual amount of extra value created? That variable is clearly worth pinning down before you launch any new combination. If the increased value is great, then the risk of outright failure is probably lower and there will be more extra value to share in the third law. If the increased value is small, then everything must go right for the combination to pay off— governance must be optimal and setbacks must be minimal. Furthermore, with such a narrow margin of error in the combination, a lopsided division of gains could well leave one party earning less from the combination than it would if the party kept its assets separate. Consequently, this party would be less likely to want to commit to the combination.

And there is an even more fundamental question: How do you even measure value in this context? The numerical metaphor makes it looks easy to add and compare values. But in fact, the benefits of a combination may come in various forms — from added cash profits or lowered costs to added learning or sustainability of an advantage. And not-for-profit partners will usually value outcomes differently still. Similarly, the inputs, or contributions, are also valued differently — these could be cash, technology, know-how, and so forth.

In the abstract, you might think that all the benefits sought and the contributions made affect shareholder value or the market capitalization of a firm. But the steps from strategic benefits to market valuation are, in themselves, usually rough estimates at best. Furthermore, each partner may perceive the benefits from any given combination differently. One partner may estimate an outcome of 3 when the other sees only 2.5. Such differences may get resolved in the negotiation over the distribution of gains, but they make the initial evaluation of joint value murky.

To address these kinds of ambiguities, you need to focus concretely on the economic and competitive mechanisms that will drive the creation of joint value. This calls for fundamental strategic analysis. Why would combining resources yield an added benefit? What new competitive advantages are generated by the combination? Does it matter how the resources are combined? Which key levers affect the amount of value created by the combination?

Second Law: Govern the Collaboration

The second law of business combinations is that they must be implemented in a way that creates joint value in reality, not just on paper. In other words, the combination has to act as an integrated operation in those areas that count for value creation. We might summarize this law as 1 + 1 = 1, referring now to unity in the management of the combination, not to its economic rationale.

Effective governance means more than ensuring that the parties get along at the personal level or that their cultures mesh. Business combinations, of course, involve people, and “soft” factors related to culture need to be addressed with care. Important as these factors are, however, they do not predict success. Excellent combinations have been struck across wide cultural differences, and harmonious personal relationships have often failed to support poorly designed business combinations. I have observed that when “cultural differences” are cited to explain the failure of a deal, the phrase more often than not hides conflicting interests and incompatible strategies.

Alternatively, the effective-governance law might seem to depend mostly on the legal structure of a combination. After all, that structure will reflect some high-level decisions, such as whether to acquire part or all of a firm, how to share investments, and so on. But this too is only a partial condition of success. Joint value does not appear automatically when assets are combined; value creation and distribution also depend on how the combination is shaped and managed after the initial deal is concluded.

When the deal is an acquisition, for example, the acquired resources can be merged into existing units or not, and the management personnel and processes may be left in place or replaced by that of the acquiring firm. Alliances, by definition, leave the partners to be managed as separate firms, but there may be varying degrees of cross-holdings or shared ownership. Simpler transactions usually include little joint management, just an agreement to exchange value on prearranged terms.

Across all these various forms, the elements that are critical to creating joint value must be managed effectively in a coordinated fashion. If the main source of joint value is economies of scale in production, for example, then the combination—whatever its form—must successfully integrate investment and management of the production facilities. If the joint value comes from sales, then that aspect of the deal, similarly, needs coordinated management. Often, the elements critical to a combination do not reside in every part of the value chain. Thus, many combinations can have successful outcomes even if they fall short of full integration and focus only on collaboration in selective areas. But in such combinations, too, excessive rivalry, conflict, or differences in management approach can doom the effort.

Third Law: Share the Value Created

Even when joint value is created by a well-governed combination, your company might not receive enough of the value. That’s why the last law is certainly not the least: ultimately, the joint gains need to be divided in a way that leaves each party better off than it would have been without the combination. The share of profits is the reward, or incentive, that encourages each party to contribute its resources to the combination.

To continue the metaphor, the 3 in the 1 + 1 = 3 of the first law needs to be divvied up. The shares are not always predetermined and don’t need to be equal. So, perhaps the summary formula will look like 1 + 1 = 1.4 + 1.6. The split can also be 50-50 or 80-20 or anything else. What matters is that each party earns a fraction high enough to convince it to redirect its assets and efforts from another use into the combination.

Determining this split of profits is often just as hard as estimating the joint value itself. Just as the joint value depends on future trends in the competitive environment, so too does the division of profits. The balance of power between the parties in the combination usually evolves, and with it, so do the profit shares. For example, a partner may go into an alliance with weakness at the bargaining table, but may gain strength over time—perhaps because its own business options are growing and its contributions to the alliance have become more valuable. As a result, whatever division of gains was agreed upon at the start may come under strain over time, with one party pushing for a renegotiation or angling for new ways to capture additional value. The survival of the alliance may then be at risk if the new conditions are not accommodated.

[ derivative id=”103829″]

Changes in the division of gains over time are also common in acquisitions, though in these deals the changes express themselves differently. In a cash acquisition (or divestment), one party is paid its share and the other gets the remaining returns, including both upside and downside potentials. If the former owners of the acquired resources retain some ownership in the new combination, perhaps because the acquisition is financed by stock, then they share somewhat in the subsequent risk of the combination. In that case, over time, each party may realize more (or less) value than what was initially anticipated.

The three laws apply to all industries and types of combinations — from mergers in industrial sectors to software partnerships in the emerging Internet of Things. To see how the laws work in practice — and what happens when combinations fail to fulfill them — consider the combination strategies of Daimler and of Renault in the early 2000s. It’s a well-known story, but we will use a new lens to compare and dissect these deals.

Leaders at Daimler and at Renault faced similar strategic issues. Each company’s leadership team decided that it needed to expand its footprint globally and increase its volume of production. Organic growth seemed a slow and difficult way to achieve these goals. Both Daimler and Renault therefore sought combinations with existing companies that could help them expand production and sales globally. In other words, both companies saw a potential to create joint value through a business combination—the first law of every business combination. From there, however, they took different steps, which have led to widely different results.

Daimler proceeded by acquiring Chrysler in the United States and then buying a one-third stake in Mitsubishi in Japan. Later, it also took a minority stake in Hyundai Motors in Korea, formed a three-way auto-engine joint venture with Hyundai and Mitsubishi, and added joint ventures in China. Overall, Daimler created a complex network of alliances worldwide at the same time that it worked to integrate the whole of Chrysler’s business.

Renault chose a different route for the governance of its combinations. It focused mostly on its relationship with Nissan, which was a substantially bigger player in Japan and worldwide than Mitsubishi. Renault acquired a one-third stake in Nissan. Later, the two companies created a 50-50 joint venture to run joint operations, and they invested directly in each other. The result was a more coordinated and balanced approach than Daimler’s multiple, but relatively separate alliances.

The differing governance choices made by each leadership team were heavily influenced by the conditions of its combination partners. Daimler was a more powerful player than any of its partners. Renault was almost equally balanced with Nissan in terms of production volumes. Nissan was financially in distress, but it had a proud and successful history, good technology, and good brands.

With these governance choices, collaboration between Renault and its partner was much more successful than that between Daimler and its partners. Daimler’s relationship with Mitsubishi unraveled after a few years; the German company later divested its ownership of Chrysler after pouring money into the American carmaker, at a deep loss on the investment. Renault, by contrast, successfully turned Nissan around and created an integrated global operation rooted in Europe and Japan. The second law of business combinations helps explain Daimler’s failure and Renault’s success.

The third law came into play too. Because the structures of the deals were different, value was shared differently in the two cases. To acquire Chrysler, Daimler paid off Chrysler shareholders with a one-third premium over market value; in other words, the returns to those former owners of the resource were fixed at this point. The residual returns to whatever joint value DaimlerChrysler might create would accrue to the shareholders of the combined company. Unfortunately, because the actual joint value created was negative, these shareholders were left with negative returns.

The Renault-Nissan partnership, by contrast, set out to create new value for all parties and to pay out benefits as the new value occurred. As a result, the structure of the alliance enabled both parties to gain (or lose, if that were the case) proportionally over time. Their mutual and partial shareholdings were the primary way in which they shared the returns of their cooperation.

Renault was clearly more successful with its combination strategy than Daimler. And the benefits of its alliance with Nissan still resonate today, as the partners continue to manage their global businesses together. Even Daimler has since invested in that combination, buying minority shares in Renault and Nissan.

Remix strategy is more relevant today than ever. Not only is the pace of mergers and acquisitions at an all-time high, but alliances, partnerships, and multiparty consortia are increasingly popular, even if sometimes below the radar. Many big pharma companies rely on partnerships for half or more of their drug pipeline. Business models using sharing and technology platforms depend on remixes too. And incumbent firms in traditional industries have to learn to evolve and adapt — often by bringing in assets from outside their boundaries. Increasingly, competition is a battle among groups of allied firms, not between stand-alone companies. Understanding and applying the three laws are keys to success in this new world.

This was adapted from Remix Strategy: The Three Laws of Business Combinations.

Identifying the Skills That Can Help You Change Careers

A lot of talented people grapple with the disruption of having to switch jobs or careers and figuring out how their current profession’s skills can be applied in a fulfilling new way. The good news is that other industries may value your talents just as much, if not more, than your existing one. The challenges are understanding what those talents are and packaging them in a way that their value to others is apparent.

I made a career switch seven years ago, when I went from working as a reporter at the Financial Times, where I covered health care in the United States, to consulting — advising CEOs in the pharmaceutical industry on thought leadership and articulating their corporate strategies. Since then, many friends and strangers have sought my advice about career paths outside of newspaper journalism.

From these conversations, I learned a broader lesson about reinventing yourself: It is tragically easy to take for granted some of your most important skills and attributes. The trouble comes from an identity trap. People associate their core skills with their old profession and assume that those skills are less valuable elsewhere. In fact, they might actually be worth more on the outside.

Consider the legal field. It has long been widely acknowledged that legal skills are broadly applicable to all kinds of careers: business, politics, finance, even sports coaching, fiction writing, and journalism. Presentation and communication skills, analytical thought, diligent preparation, and attention to details are all highly prized. The same is true of other professions. From inside an industry, fundamental skills can seem like a commodity. But to outsiders, they may be crucial to succeeding in 21st century business and life. In the case of journalists, that means the ability to:

Communicate clearly. Inside the profession writing is like breathing — involuntary, common, barely noticed. But outside, the skills of storytelling, structure, and clarity of communication in any form or medium, including the digital, are highly valuable.

Execute fast. Everywhere I turn I hear leaders stress the need for speed and agility to create a competitive edge. Few people or organizations can match the speed with which a newsroom and its reporters can execute. Every newspaper reporter has probably written an important story in under 30 minutes to make an edition — analyzing and digesting incredible amounts of information, formulating ideas, and making decisions before the clock runs out.

Think creatively. At any level of an organization, and particularly at the top levels, the ability to find and piece together disparate bits of information to form a new view of the whole is essential. Journalists do this nearly every hour of every day — driven by the desire to get to the root causes of events and issues.

Build networks. Inside the profession, building an extensive network of contacts and sources for stories is like tying your shoelaces. A friend once said to me, “You actually go to lunch with strangers and find something to talk about the whole time?” It had never occurred to me before that others would find this hard to do. Consider how many articles, advice columns, and books have been devoted to networking and its value for decision making, personal success, and better understanding of the external environment. Journalists can build connections and bring new ideas into an organization as a matter of routine.

Act with courage. Many journalists put their name on the line every day. David Carr, the late New York Times columnist, once said that the moment a controversial story goes live, you brace yourself in anticipation of the “boom.” Your work is publicly scrutinized every day. What leader wouldn’t see this fortitude as a valuable asset in any line of work?

So how does one identify his or her transplantable core skills? Here are some simple, commonsensical steps.

Tap other reinventers. Take a step back and think about the skills that are crucial to excelling in your existing industry. Consult with people who have already transitioned from your industry to a different career. Discuss what core skills you might be overlooking and how they could apply outside. The range of potential applications is probably broader than you think.

Confer with outsiders. Talk with a wide range of folks outside your industry, especially people who have interacted with you professionally. Ask them for their opinions of your core skills. I talked with several CEOs at health care companies. You should also ask: How you should market them? What are less-obvious functions or organizations looking for such skills? What are the obstacles to landing such work?

Create a strategic message. This is often overlooked. The best CEO strategists with whom I have worked distill what a company needs to do to a stunning simplicity. For instance, Fred Hassan’s successful turnaround strategy for drug maker Schering-Plough was: “Grow the topline; grow the R&D pipeline; reduce costs and invest wisely.” Individuals should do the same thing – which is how I came up with: “Communicate clearly, execute fast, think creatively, build networks, and act with courage.”

The skills you take for granted just might be gold. When you position them the right way, you might be able to launch a brilliant second career.

What Companies Can Learn from Military Teams

When Gen. Stanley McCrystal took charge of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Task Force in 2003, he recognized that traditional tactics of warfare were failing in Iraq. Leading this inter-service team — which included Army Rangers, Navy SEALs, and Delta Force — he needed to find new ways to disrupt Al-Qaeda and get these disparate branches of elite U.S. soldiers to work cohesively. In the new book Team of Teams, McChrystal describes the lessons he learned (and applied) in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as research and examples from other fields (including sports, aviation, and emergency medicine) on how teams have learned to work more effectively. (The book is co-authored by his colleagues Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell.)

Since his retirement in 2010 — brought about by intemperate remarks about Obama officials made by McChrystal and his aides in a Rolling Stone article — the former general has taught leadership at Yale University. He’s also founded a consulting firm called CrossLead. I talked to him about what businesses can learn from the military model. Here’s an edited version of our conversation:

HBR: How did the way the military builds teams change between the time you joined the U.S. Army, in the late 1970s, and the early 2000s when you were leading forces in Afghanistan?

McChrystal: When I joined Special Operations as a Green Beret, we were already pretty good at operating as small teams — say, up to about 20 guys. Inside those teams, you had a chain of command, but you also had a more informal set of linkages. You had constant interaction — the ability to not just hear what people say, but see their actions up close. You get a level of familiarity with teammates, and they get in-depth knowledge of you, too. This informal set of interactions is really the magic. The more powerful those informal interactions are, where all it takes is one glance between one person and another, that’s how you go from command and control to organic movements.

You talk about “trust” as the key element in high functioning teams. How can you accelerate the establishment of trust?

Trust does take time, but it doesn’t have to take time between you and me personally. This is the idea of scaling teams. You trust certain things. If you’re driving on a highway and you’re hungry, and you see a McDonald’s sign, you might decide to go there because you’ve developed a level of trust in McDonald’s, even if you’ve never been to that specific location. In the same way, as you try to build trust inside a team, you try to make trust transferrable.

Let’s say you’re a Navy SEAL and I’m in the Army’s Delta Force. I may not know you personally, but I know some SEALS, and I know how they operate. I know your expectation of me, and you know my expectation of you. We have this understanding that I trust in the values of your organization, and the track record of your organization, and I transfer that trust to you if you’re wearing the right patch and have the right pedigree … [But] it does take a certain amount of personal interaction with people from the organization.

When you take on a new leadership role, what do you do the first day to try to jump-start trust and team-building?

You come with a reputation, but the reputation doesn’t necessarily include trust. It includes an assumption of competence. Sometimes it includes negative things. People might be afraid because they hear you’re a hard-ass. Regardless, the number one thing I try to do is develop personal relationships with key people in the organization. I try to exhibit trust in small ways. In a briefing, if somebody asks me for a decision, I might turn to a subordinate and ask them to handle it. I don’t ask for specifics, and I’m very overt — almost theatrical — about it. Everybody else sees it. The message is: “I trust you guys to handle this stuff,” and that can grow virally throughout an organization.

As a general in Iraq, you went on risky nighttime raids with troops. Why?

Three reasons. First, if you’re putting people in harm’s way, it’s helpful to regularly put yourself in harm’s way. They don’t need me on a mission — I’m not adding value — but accepting some level of common risk with them earns respect. Second, you have to see up close what’s actually happening. You can get descriptions, or watch it from a drone on an HDTV, but you don’t see the faces of the Iraqis. You don’t hear things. You don’t smell things. The last part is there’s a certain theater to commanding. People have an expectation of commanders. You can define your expectations any way you want them to be. A lot of people hear about you more than they directly see you. In a big organization, soldiers may only see the commander on a videoconference, or very occasionally in person. And some of the things you do — like going on missions — help to define you as a person and make clear what set of values you think are important.

Special Forces spend a lot of time rehearsing missions, but as you point out in the book, war has become so unpredictable that the value of rehearsal seems to be diminishing. How should training evolve in that situation?

I still believe in rehearsals, but I’ve learned they have a different value. When I joined the Army Rangers in 1985 we’d rehearse airfield seizure operations — we’d parachute in wearing night vision goggles, and take the field. It’s a pretty complex thing, and we’d do it over and over. We’d have contingencies in case things went wrong, but we were always trying to make things as foolproof as we could. The longer we did it, the more I realized the value of rehearsal was not in trying to get this perfectly choreographed kabuki that would unfold as planned. The value of rehearsal was to familiarize everybody with all the things that could happen, what the relationships are, and how you communicate. What you’re really doing is building up the flexibility to adapt. I’ve never been on an operation that went as planned.

Many companies lack an overarching mission that can really bring people together the way the military’s mission does. So are the lessons of military team-building really transferrable to the private sector?

The lessons are hugely transferrable. I’ve spent the last five years on the commercial side, and it’s much less different from the military than I’d expected. The perception of the military is that we’re always on a razor’s edge, operating in dramatic environments, and making extraordinary decisions. Yes, there is a fair amount of that, but that’s more TV and movies than day-to-day. The things that make the military so good and able are very basic things, such as building levels of relationships and understanding capabilities.

I find leadership in the commercial world is extraordinarily similar. There are differences. Military leadership is easier. Money is not a factor — Congress decides what people get paid, and you can’t [decide on your own to] promote your own people, so no one asks for raises. And even if you work for a great company, it’s hard to [make the mission statement] as simple and compelling as the military’s is. So in some ways, the military has it easier. In other ways, civilian companies can be more adaptable and nimble. They’re aren’t burdened by the level of law and regulation and bureaucracy that the military is.

The Key to Giving and Receiving Negative Feedback

Rich was a plant manager with a 10,000-person workforce producing a billion dollars of product per year. He was a pro at his craft and highly respected in his industry. I met with him and his team weekly as an organization development consultant for a couple of years. Someone from HR asked him to participate in a new program called “360 Feedback.” He had never heard of such a thing but thought it seemed worthwhile. “After all,” he told me, “feedback is the breakfast of champions!”

He dutifully identified about 24 director reports, peers, and others to fill out the structured surveys. Two weeks later, he received his feedback — all gussied up in an official looking folder with pie charts, line graphs, and verbatim quotes from his colleagues. The results left him feeling crushed. For days afterward, he arrived at work early, locked his office door, and didn’t emerge until others had gone home.

Most people dread both giving and receiving feedback because we’ve either experienced — or imagined — an episode like Rich’s. We heard something about us that provoked painful emotion. Or we expressed concerns to others and they recoiled in horror. Our belief that these types of exchanges will carry a high probability of hurt makes us understandably reluctant to invite them.

When feedback goes badly, we draw exactly the wrong lesson from the experience. We assume the problem was the content. For example, Rich concluded that the pie charts, line graphs, and quotes in his feedback report created the misery he felt for the subsequent two weeks. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Feedback doesn’t have to hurt. In fact, under the right conditions, there is nothing we want more than to know the “truth” as others see it. We want to know how others feel about us and our performance. I’ve worked closely with dozens of senior executives over the years — and the number one complaint I hear from them is that people won’t tell them the truth.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

The predictor of misery is not in the message itself; it is in how safe people feel hearing the message. If people feel psychologically safe, they crave truth. If they feel unsafe, even the tiniest hint of disapproval can be crushing.

When I discovered Rich had cocooned himself in his office, I knocked on his door. His feedback report was sitting in the middle of the blotter on his desk. When I asked what was so hurtful in it he said, “They think I’m controlling! I can’t believe it. They think I’m a micromanager!” The irony here is that prior to receiving his feedback, I had asked for his predictions and he had said confidently — and with a bit of a smirk — “They’ll ding me for being a control freak.” Now having heard the very message he expected, he was feeling leveled by it. Why?

Clearly it wasn’t because of the content. You can say almost anything to someone if they feel safe. Likewise, you can hear almost anything, if you feel safe. Now let me be clear — I’m not suggesting negative feedback will make you feel giddy — but I am suggesting that if you feel psychologically safe you’ll be able to hear it, absorb it, reflect upon it. Rich’s misery didn’t result from feedback about a personal weakness, but from his conclusion that the feedback was a personal attack. It was his belief about intent not his disagreement with content that generated his despair.

Here are some principles for helping yourself and others feel ready to give and receive feedback.

You can’t make others feel safe. My emotions are my responsibility. No one can pour soothing neurochemicals into another person’s brain to quell the fears that trigger defensiveness. We are ultimately responsible for understanding the fears we carry and for managing them when they interrupt our ability to engage in honest and open dialogue with others. The ultimate responsibility for making me feel safe falls on me.

You can make it easier for others to feel safe when offering feedback. There is a lot you can do to reduce the likelihood that others will feel unsafe hearing your feedback. For example:

Get your intention right before you open your mouth. There’s a difference between feedback and blowback. Feedback is information intended to help others learn. Blowback is information used to wound. If someone has let you down or performed poorly, and you’re feeling resentful or angry — deal with your own emotions before attempting to engage in a dialogue. When you feel a genuine concern for the growth and development of the other person, you’re ready to talk — and not a moment sooner.

Ask permission. Control is central to safety. Never give feedback until it is invited. Offer it, but then wait until the other person feels ready to receive it. When you ask permission by saying something like, “Can I give you some feedback about your presentation?” you recognize the fact that the other person is responsible to get herself into a healthy emotional state before the feedback arrives.

Share intent before content. People become defensive less because of what you’re saying than because of why they think you’re saying it. For example, in Rich’s darker moments, he believed his colleagues were trying to take him down. It wasn’t that he disagreed with what they said, it’s that he concluded anyone who would say something like that must have malicious intentions. Before sharing feedback, ensure that others understand your positive intentions in sharing it. For example, “When you have a moment I’d like to discuss how the sales trip went. I want to be sure I’m doing my best for you on these trips and want to share ways it can work better for me as well. Can we talk?”

You can make yourself feel safe before receiving feedback.

Get ready before opening your ears. Never invite feedback until you are ready for it. “Ready” means that you want to hear the truth, not simply validation. If after receiving feedback you feel defensive, it might be that you wanted approval, not information. For example, when Grandma asks, “Do you like my spinach casserole?” she may really mean, “Tell me I’m a good grandma!” Rich got into the same trouble. He later reflected that, “When I opened the folder my eyes first searched out the relative scores — I was hoping to see that I was better than my peers.” When others give you feedback, you set them up to fail when you make them responsible for your feelings of safety and worth. Don’t do that. Find healthy ways to affirm and center yourself. Meditate. Reflect on your personal values and beliefs. Use whatever rituals work for you to connect with a sense of worth that is independent of others’ assessments prior to opening the spigot — then listen with curiosity, not insecurity.

Hold boundaries until you’re ready. If you feel unready to receive feedback, do yourself and others a favor and let them know. Then take responsibility for scheduling a time by when you will properly prepare yourself. Better to admit that you’re feeling too vulnerable than to prove it by being defensive.

Be curious. The best inoculation against defensiveness is curiosity. Act like a detective pursuing a mystery called “I wonder why they feel that way?” Ask questions. Request examples. Stay curious until — even if you don’t completely agree — you can see how a reasonable, rational decent person would think what they think. Later, you can decide what you agree or disagree with, but for now, your goal is simply to learn. Curiosity inhibits defensiveness because it keeps the focus off of your self worth and on the experience of others.

Rich could have avoided a lot of pain by monitoring his own motives and safety prior to tearing open his envelope. Others could have mitigated his reaction by assuring him of their positive intentions in offering their critique. Pain is not an essential byproduct of feedback — it is the result of an absence of safety.

August 5, 2015

Feedback Without Measurement Won’t Do Any Good

The managerial feedback was excellent — crisp, clear, and constructive. Its tone was caring, compassionate, and compelling. Each criticism was consequently heard, acknowledged, and understood. Message received; next steps agreed. A potentially awkward and painful conversation became a bonding experience. It was a best-case scenario.

Fifty days later, alas, nothing substantive had changed. A quick fortnight of self-awareness yielded to “business-as-usual.” It was as if that open and honest exchange had never taken place.

Sound familiar? People understandably invest significant time and care trying to get better at giving feedback that matters. Unfortunately, those investments typically underperform. The reasons are simple and obvious: The true purpose of better feedback is not to improve receptivity or enhance understanding but to effect measurable change.

Feedback is a means to an end. No matter how charmingly or charismatically delivered, feedback that doesn’t lead to better outcomes fails. Doctors counseling unhealthily overweight patients to eat less and exercise more may indeed be giving life-saving feedback. But until meaningful pounds are actually shed, no one’s getting better. Making the feedback more empathic or persuasive utterly misses the point.

Feedback’s intrinsic flaw isn’t in the medium or the message — it’s in the metrology. Feedback must be explicitly linked to metrics, measures, and mechanisms that track the desired — and desirable — change. Feedback that comes without ways to monitor measurable change is less meaningful feedback than it is well-intentioned advice. In other words, effective feedback requires effective feedback.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

That’s why understanding feedback’s future requires embracing the quantified self. Our expanding abilities to digitally, visually and pervasively self-monitor will transform how on-the-job feedback gets defined, developed, and delivered. Today’s self-quantifiers count calories and steps and time spent; tomorrow’s will be tracking what their bosses, collaborators and — yes — customers and clients want them to improve professionally. Serious feedback will come with self-quantification attached. (That’s how you’ll know it’s serious.)

The future of feedback is the future of self-quantification. The future of self-quantification is the future of feedback. The critical and controversial challenge, of course, revolves around consent. Today’s self-quantifiers choose to do so; will tomorrow’s?

It’s one thing to have a superior, colleague, or client offer constructive criticism; it’s quite another when professional critiques come with apps designed to monitor one’s efforts to improve. A Fitbit tracking physical steps feels like less of an imposition than one tracking tone, temperament, and/or collegiality.

But feedback’s fusion with trackers and performance monitors feels both inevitable and obvious. Do colleagues and subordinates find your email and social media messaging too snarky and off-putting? IBM now offers “sentiment analysis as a service” that tracks the tone and tenor of personal and professional communications. You can now be more reliably “nudged” to become a kinder and gentler communicator.

Mismanage scheduling and follow-ups? Your calendar and contacts lists can be programmed to alert you to coordinate with the frequency and reliability your boss — or peer group — wants. In other words, feedback compliance — or assurance — becomes integrated into the networked fabric of day-to-day performance and processes. I coined the word “promptware” to describe software that could be used by individuals who wanted to take such self-improvement measures. But making “promptware” part of next-generation organizational feedback also makes professional sense.

These technologies and innovations make creating cultures of accountability more practical and transparent. Indeed, feedback should be about enabling and assuring accountability for improvement. We could rightly give these feedback-empowering apps their own name: “accs” or apps designed with “accountability’” in mind and spirit. Organizations that care about Kaizen, or the process of continuous improvement, and facilitating effective feedback will make “accs” a way to make sure that their people have the power to (self) improve. When it comes to tomorrow’s feedback, actions and data will speak louder than words.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers