Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1263

August 13, 2015

Digital Fairness vs. Facebook’s Dream of World Domination

As founder of the nation of “Facebookistan,” Mark Zuckerberg has his hands full with over a billion worldwide users. But as you may have heard, he has an even bigger dream — to hook up the 4.5 billion people around the world who lack internet access. The one-year-old Facebook-led initiative, called Internet.org, is designed to offer free access to a select set of websites like a “lite version” of Facebook, Wikipedia, and others, along with a limited number of content services on mobile phones. Facebook and the consumer make a deal: the consumer gets free access to a limited form of the internet and it’s a good bet that as more people get this access, Facebook itself will be one of the biggest beneficiaries.

It’s an arrangement that raises questions, especially from activists campaigning for net neutrality. Businesses like Facebook are filling an internet access gap in emerging markets that others, including the public sector, may simply never be able to address. Plus, the company has an interest in giving more people access; a Mobile Africa 2015 study of five of Africa’s major markets found that Facebook is, on average, the most popular phone activity, more popular than sending SMS or listening to the radio.

We believe there’s an even more fundamental issue at play here: What does a digitally “fair” world entail? Is it better for a society to be more digitally inclusive, even with the help of corporations (while also pursuing their business interests), or should a guarantee of absolute principles of net neutrality come first – regardless of whether it deters such private initiative?

India is a prime example. Only 19.2% of its population has internet access (at home or over a wireless device); other estimates, such as that from the World Bank, suggest that the number may be even lower, 15.1% in 2013. According to a McKinsey & Company study India’s biggest barriers to internet adoption are primarily in the areas of internet access capabilities and awareness of the internet itself. While the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced its intentions to help close the gap, including the recent launch of a widely publicized “Digital India” campaign, the country’s vastness, large population, and poor infrastructure mean that it will take time to see real improvements.

The private sector has shown a willingness to step into the breach. Despite having 200 million internet users at the end of 2014, India is not even among the top 10 e-commerce markets in the world, according to a recent eMarketer report. Meanwhile, China’s e-commerce market is 80 times as large. Given this context, it comes as little surprise that businesses — like Facebook, Google, and telecommunications companies — have the motivation to improve internet awareness and access. This helps them and other digital economy players expand their markets where governments continue to fail. It’s an investment for the future. And they are willing to fight for it – Facebook just launched a campaign in India to defend its Internet.org initiative as a government panel prepares a report on net neutrality.

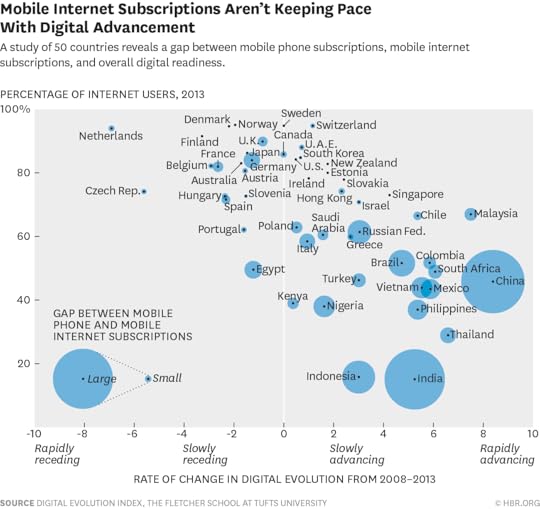

In our Digital Planet study at Tufts, and in our related HBR article “Where the Digital Economy is Moving the Fastest,” we ranked 50 countries on their digital readiness and identified supply infrastructure, including telecommunications bandwidth and subscriptions to services that offer internet access as critical areas to improve. As part of this research, we examined how rates of digital evolution compared to mobile internet usage. We use a measure that we call the “mobile internet gap.” It is the difference between the total number of users in a country with cellphone subscriptions and users whose cellphone subscriptions also provide access to the internet.

The graphic above shows that a country such as India may in fact have great potential for economic growth if the critical bottleneck of internet access improves. It is among the countries with the lowest internet penetration rates; it has one of the highest mobile internet gaps; and finally, it is one of the faster-moving countries in terms of the pace of its digital evolution. To an investor, this combination of factors would make India one of the most attractive markets – not just for Facebook, but for venture capital and private equity investors as well.

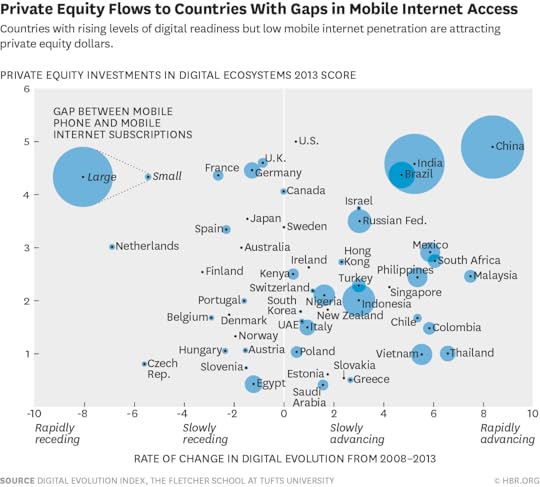

In fact, as the next graphic indicates, a market such as India has been among the top destinations for private equity investments in the space since 2011. For this comparison, we used a scaled score of private equity investment funds that were invested into digital ecosystems in that particular year.

In recent years, there has been a rush to populate India’s nascent internet economy: Amazon committed $2 billion for growing its presence in India last year and local online player Flipkart attracted $550 million in its latest round of funding. Flipkart was ranked third among the world’s most valuable privately held startup companies, alongside stars such as Palantir Technologies and Snapchat Inc., according to a WSJ/VentureSource analysis. In the meantime, Uber is aggressively taking on the domestic competitor Ola Cab, and Ola Cab’s Japanese backer, SoftBank, has pledged to invest up to $10 billion in Indian internet businesses over the next decade. So government efforts are already lagging the profit-driven motives of the private sector.

In other emerging markets, China is still one of the best places to look to get a sense of the economic impact of easing internet access bottlenecks. Its still sizable mobile internet gap notwithstanding, China, according to a Morgan Stanley Report , accounted for 35% of global ecommerce in 2013 at $314 billion versus that of the United States at $255 billion. In the first half of 2014, 26% of all online purchases in China were made on a mobile phone. One can only expect this number to grow as China further narrows its mobile internet gap.

In Latin America, Brazil displays the very same combination of factors as India – its large population size and low mobile internet penetration rates have been attracting interest from companies such as Xiaomi, the Chinese handset maker, which is eyeing Brazil for its first smartphone launch outside Asia, and investors in online marketplaces eager to get a slice of the largest market in the world for beauty products, behind the U.S. and China.

If lagging digital economies are going to ever catch up, there’s a need for greater public-private collaboration around internet access. And until the public sector has a plan — and the budget — for spurring access, spurning ideas from the private sector could further slow the pace of development. This means accepting a tradeoff in the role of private business, but even a limited form of access through initiatives like Internet.org is a better alternative to no access, especially given the size of the excluded population worldwide and how much is foregone by those on the wrong side of the digital divide. A digitally “fair” world may in fact take on many different shapes and deliver services through some unexpected actors.

What the U.S. Military Has Learned About Thwarting Cyberattacks

No sooner had my coauthors and I put the finishing touches on our Harvard Business Review article that holds up the U.S. military approach to cyberdefense as a model than news stories disclosed that there had been a serious breach of the unclassified e-mail system used by employees of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon. But the incident actually heavily underscores our principal point.

Reportedly, the attackers used a spear-phishing e-mail to penetrate the system. The Department of Defense has found that the lion’s share of successful cyberattacks are made possible by poor human performance. Indeed, a key element of our thesis is that most organizations place too little emphasis on changing behavior and too much on technical safeguards.

We suggest that companies should follow the U.S. military’s example. It is strengthening its cybersecurity by applying the methods used by the U.S. Navy’s nuclear-propulsion program, whose safety record is second to none. These include a robust program of training, reporting, and inspections, as well as six operational excellence principles. They are:

Integrity, a deeply internalized ideal that leads people, without exception, to eliminate “sins of commission” (deliberate departures from protocol) and own up immediately to mistakes.

Depth of knowledge, or a thorough understanding all aspects of a system, so people will more readily recognize when something is wrong and will handle any anomaly more effectively.

Procedural compliance, which entails requiring workers to know — or know where to find — proper operational procedures and to follow them to the letter. They’re also expected to recognize when a situation has eclipsed existing written procedures and new ones are called for.

Forceful backup, which means, among other things, having two people, not just one, perform any action that poses a high risk to the system and empowering every member of the crew — even the most junior person — to stop a process when a problem arises.

A questioning attitude, which can be instilled by training people to listen to their internal alarm bells, search for the causes, and then take corrective action.

Formality in communication, which means communicating in a prescribed manner to minimize the possibility that instructions are given or received incorrectly at critical moments (e.g., by mandating that those giving orders or instructions state them clearly, and the recipients repeat them back verbatim). Formality also means establishing an atmosphere of appropriate gravity by eliminating the small talk and personal familiarity that can lead to inattention, faulty assumptions, skipped steps, or other errors.

The entire U.S. military is gradually embracing these methods as a central part of its efforts to bolster its cybersecurity. Despite this recent embarrassing attack, it has actually made good progress. With cyberattacks on the private sector a serious problem, business leaders must also turn their companies into high-reliability organizations. Technological safeguards, while vital, will not alone make a company safe.

August 12, 2015

The Example Larry and Sergey Should Follow (It’s Not Buffett)

Coverage of Google’s restructuring has focused on the idea of Alphabet as a new kind of internet-era conglomerate. Optimists compare the new entity to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway; skeptics point out that the conglomerate model seldom works.

But there’s a better comparison than Buffett: it’s John Malone, the “mastermind” who built the cable TV powerhouse Liberty Media. Malone is a brilliant financial engineer, who creates separate capital structures — each with a unique stock — for his different lines of business. Liberty Media, Malone’s holding company, owns a portion of the stock in each business. This approach allows Malone to attract equity and debt investors whose preferences regarding risk and payoff horizon match those of the business in question.

Having separate stocks also allows Malone to place bets when he believes that one line of business is not correctly valued by investors. If he thinks one of Liberty’s companies has a rich valuation, he can sell more stock to outside investors at a high price. Or, if investors are enthusiastic about a new business that Liberty is incubating inside one of its existing companies, he can spin out that business as a “newco” with its own stock. Conversely, if Malone thinks that the market has undervalued one of the companies, Liberty can buy back its shares.

As The New York Times put it in 1997, when describing the spinoff of TCI Ventures, which provided innovative new broadband internet services:

For Mr. Malone, the spinoff is a way to get more value from assets that he believes have been neglected by investors and overshadowed by Tele-Communications’ prime business, the ownership of cable systems with 14 million customers.

In this case, Malone traded investors some of his shares in the core cable business for a bigger equity stake in risky new ventures, which he thought the investors didn’t fully appreciate. Sound familiar?

To be clear, Google has thus far given no indication that it plans to create separate stocks. But its new structure would making doing so much easier. As Todd Zenger wrote here earlier this week, many investors want to buy stock in a safer, maturing search advertising business without buying into Google’s riskier moonshots. Alphabet promises to make the financial performance of its companies more transparent, but the big change would be if some of these companies traded under different stocks.

At that point Alphabet could sell shares of Google to more risk-averse investors; it could raise capital for its self-driving cars from the same sort of people who are betting on Uber or Tesla; it could seek funding for its renewable electricity projects from energy financiers.

A potential downside to this strategy is that it would make it more difficult for the ad business to directly cross-subsidize riskier tech investments. Formal contracts would be required for transactions between the companies, and each side would need to be able to make the case that a transaction was in the best interests of its respective shareholders.

And there’s still the question of why a holding company with full or partial stakes in a diverse set of somewhat unrelated businesses can be expected to create value. We know from years of academic research that on average, diversification into unrelated businesses doesn’t create value for shareholders. Why should Alphabet be different?

But Google’s founders seem more than happy to challenge the conventional wisdom. “Google is not a conventional company,” they wrote in their original founders’ letter. “We do not intend to become one.” Google’s founders have strong views about where technology is going, and where it should go, and they don’t seem that bothered if others disagree. Malone — also a technology visionary — feels similarly; he’ll bet against the market when he thinks that it is wrong. That’s something he has in common with Larry and Sergey.

How to Give Feedback to Someone Who Gets Crazy Defensive

How do you handle giving unfavorable feedback to someone who will surely take it badly – and I mean really badly? Think: shouting, tears, defensiveness, accusations, personal attacks, revising history, twisting words — pick your nightmare.

Consider the case of Melissa, who was the team leader on a recently concluded project that had not been a stellar experience for anyone involved. For most of the team, the project was a disappointment from the start: team members were assigned, not self-selected; it was known not to be a high profile project; and the deliverables were really important only for Melissa’s mentor’s research. Melissa’s role was not a powerful one. She was first-among-equals and the liaison to management, but had more responsibility than actual authority. The carrot that management held out to members of the team was that this was a steppingstone project: if the results were satisfactory, they could anticipate higher profile projects going forward.

James, a team member in a different location, handled the situation by making the project a lower priority than his other work. His assigned contributions were often late or missing altogether, but he knew Melissa would pick up the slack because it was in her mentor’s interest for someone to do so. He considered this a pragmatic solution — he had a lot of work to do. His miscalculation, however, was to assume that the team’s work would be seen only as a whole, which may have been a bit naïve, as well as self-justifying. Instead, when the project ended, Melissa herself was asked to recommend individuals from the team for a new, more important project. James would not be one of them, and Melissa had scheduled a feedback session with him to let him know.

Melissa knew the conversation would not go well. James was someone who was known to shout at people, distort their words, accuse them of victimizing him, and more. Melissa’s own temperament was very unlike his, and the thought of giving James negative feedback was a nightmare.

How should Melissa handle the situation?

When we fear someone’s reaction, most of us look for techniques to make the other person act differently. But when receiving disagreeable feedback, people generally repeat tactics that they’ve had success with in the past — that’s why they use them. Upon hearing the negative feedback, it’s likely that James will be surprised and angry. He’s likely to believe that Melissa misrepresented the project and is scapegoating him, taking from him the only benefit of four months’ work. In James’ view, how he responds makes sense: Melissa is not reliable, not his boss, and intends to hurt him. Why would he act differently? He wants her to back off.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

Melissa foresees that scenario, but her temperament makes her vulnerable to what business theorist Chris Argyris calls “defensive strategies” — ambiguous, counterproductive behavior chosen to avoid interpersonal discomfort. (Examples of this might be Melissa deferring to James, apologizing and agreeing that he is being misused, while stressing that she is just the messenger. Or, she might email the message, letting him simmer unaddressed. Or she could ask someone else to tell him. Any of these would protect Melissa from immediate discomfort, but they also signal weak competence.) Defensive strategies become “skilled incompetence,” Argyris says. We get really good at avoiding the difficult bits, but cannot reach good outcomes and never really accomplish our goals. That can’t be recommended as a feedback approach, even if it seems better than butting heads.

Yet if Melissa does try to toughen up and match James’ confrontational style, even though she knows firsthand that it is not well-received, it’s sure to backfire. Emotions will rise, and the conversation will degenerate on both sides, destroying the relationship, and potentially both of their reputations.

Melissa needs to try a different approach. One tactic is to focus on immunizing herself against her own vulnerability to James’ difficult behavior. This is like a scientist who, when studying how a pathogen compromises a cell, focuses on the cell, not the bug.

How would Melissa self-immunize against James’ outbursts? By recognizing that she has to react to the tactic for it to work. Instead of reacting, she can neutralize how she responds, without giving in or giving up what she has to say. To get there, she can use a blueprint that pulls together three attributes of speaking well in tough moments: clear content, neutral tone, and temperate phrasing. (These are opposites to both skilled incompetence and confrontation.)

Clear content: Let your words do your work for you. Say what you mean. Imagine that you are a newscaster and that it’s important that people understand the information. If your counterpart distorts what you say, repeat it just as you said it the first time.

Neutral tone: Tone is the non-verbal part of the message you’re delivering. It’s the inflection in your voice, your facial expressions, and your conscious and unconscious body language. These carry emotional weight in a difficult conversation. It’s hard to use a neutral tone when your emotions are running high. That’s why you need to practice it ahead of time, so you’re used to hearing it. Think of the classic neutrality of NASA communications in tough situations: “Houston, we have a problem.”

Temperate phrasing: There are lots of different ways to say what you have to say. Some are temperate; some baldly provoke your counterpart with loaded language. If your counterpart dismisses, resists, or throws back your words, he’s not likely to hold onto your content — so choose your words carefully.

Clear content, neutral tone, and temperate phrasing are a package deal. Melissa won’t get good results if she uses temperate phrasing, but mixes her message with a lot of contradictory body language. Nor will it work well if she thinks her content is too blunt, so she softens it. Being blunt is a characteristic of intemperate phrasing, not of content. So softening the content to fix a problem of phrasing won’t get her where she wants to go.

If Melissa says to James, “In February, March, and April, the team didn’t get the deliverables you committed to on the dates you agreed to,” her content is clear and her phrasing is temperate. We have to imagine that her tone is neutral, but Melissa can do it. If she says, “With those omissions, I can’t stand behind a recommendation for you,” she is clear and temperate again. We do understand that the news is not good and James is still likely to dip into his arsenal of difficult tactics. But Melissa is on solid ground, neither altering her message nor responding to his tactics. With this blueprint in place, repetition can be a good friend: if James challenges her or distorts her message, Melissa can repeat what she has said, rather than following James down a rabbit hole. When it’s time to end the meeting, she can say something simple such as: “Thank you for meeting with me. [Short pause.] I wish this had worked out differently.”

Will James be happy with this conversation? I think not. Nobody likes unfavorable feedback. But remember, when delivering negative feedback to someone who’s likely to get defensive, it’s not your job to make the other person feel better. It’s your job to deliver the information in a clear, neutral, and temperate way — by sticking to the facts, and to the blueprint.

Great UX Doesn’t Guarantee a Great Customer Experience

It’s one thing to create a great looking product that’s easy to use. It’s another to create a great experience that continues to improve, delight, and expand in scope over time. The first is user experience. The second is customer experience.

The two are often used interchangeably. But generally, user experience focuses on designing a particular device or screen and the interactions that occur on it, while customer experience stitches those together with many other touchpoints (front-line staff, promotional emails, store environment, etc.) spread out over time.

Here’s an example. Google Maps has long been the gold standard in mobile mapping applications. Nevertheless, Google continually updates Maps to make it even better– it has introduced 1-finger zoom (instead of the trickier 2-finger-pinch zoom), and the app now gives lane-specific turning instructions (“Take the left two lanes to merge on to…”)

These are examples of iterating the user experience: they improve the usefulness and usability of the app–but they are limited to finite interactions within the app itself.

However, Google is also moving to a more integrated customer experience across touchpoints. For example, the mobile and desktop versions of Maps share common histories of what you’ve looked for, which is great if you start looking up something at home and then hop in the car a few minutes later to actually go there. What you just searched for will be at the top of the recent history list in mobile. That’s smart and helpful.

One recent experience is a good example of Google’s attention to the customer experience. A change to the mobile Maps app really made me mad–mad enough, in fact, to send Google a note using the feedback mechanism within the app. What got me so steamed up? The red, yellow, and green lines denoting heaviness of traffic had been made so thin they were now hard to make out against the amber-colored roadways. Believe me, in San Francisco Bay Area commute traffic, this counts as a major problem!

I checked user reviews in Google’s Play app store to see if anyone else had noticed the same thing – no one had. So I sent in a complaint through the mobile app itself, got a generic “Thank you for your feedback” message (yeah, whatever), and thought nothing else of it.

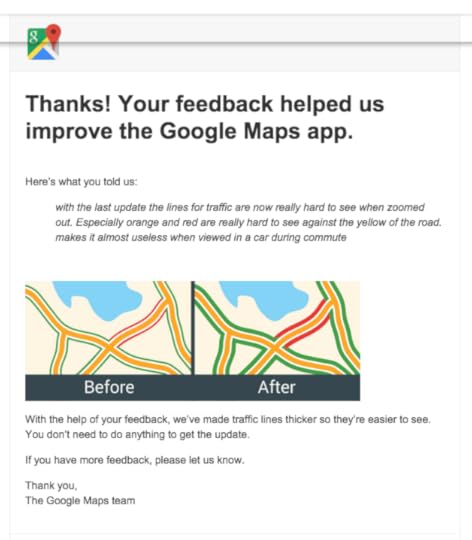

A few weeks later, I got this email from Google:

I literally said “Wow!” I was surprised I got a response at all, but even more amazed at the personalization of the response.

And sure enough, when I checked my Maps app, the lines were back to being thick and easy to see – no update required. (My guess is that I was part of a Maps traffic A/B test, because of the lack of other people commenting on this interface change and the fact that I didn’t need to download an update in order to change it. So it was probably just a flip of a virtual switch to restore my old thick lines.)

Customer experience mission accomplished: delight over a period of time, utilizing multiple touchpoints, responding to feedback. Loyalty restored.

There’s a lot going on behind the scenes to create this delightful experience. But if we peel back the different layers that made it possible, we find practices that — with a little creative application — can help almost any company make the jump from user to customer experience:

Integrate across touchpoints: In 2015 having a cohesive, integrated experience across desktop, mobile, email, call center, sales, etc. is just expected by customers– but it’s still hard to do consistently. It requires fostering cross-team organizational collaboration on features and design, and thinking about how each touchpoint acts as an on-ramp to another.

Don’t ignore the plumbing: Smooth multi-touchpoint experiences are enabled by lots of “boring” behind-the-scenes infrastructure that passes customer data around so that it can be employed at each touchpoint. Arguably, Google faces challenges of a scale that almost no other company does, which is what makes the Maps example of personalized feedback so remarkable: cataloging and tagging of feedback types, scanning of text for keywords and follow-up responses, keeping the A’s and B’s of the test separate over time, etc.

Make the experience personal: Acknowledge the individual customer’s situation and demonstrate that you understand their specific needs. In the Maps example, Google did this by repeating my own words to me and then acting on them.

Make feedback part of the customer experience: How do you tell if you’re moving your customer experience in the right direction? Customer feedback. So make gathering it an integral part of the experience itself, as Google did here — even the customer feedback mechanism was itself a source of delight.

Delivering great customer experiences requires going beyond the surface of individual customer interactions. You must instill a mindset that takes a systemic view over time of the customer needs and your organization, and match it with the capabilities to deliver the integrated touchpoints. If you’re just starting to make the leap from user experience to customer experience, keeping these principles in mind will help steer you in the right direction.

GE’s Real-Time Performance Development

As managers in a large, complex organization at GE, we face a daily challenge: ensure that our employees collaborate, make quick and effective business decisions, and provide our customers with superior products and services. But like at other companies, our teams and departments tend to focus on their piece of the business — siloed behavior that causes frustration and impedes broader aims.

To cultivate empowered, collaborative, cross-functional teams, we have been experimenting with a new approach to performance development. Our teams were among the first to adopt it as part of a pilot, and we have used it to drive a fivefold productivity increase in the past 12 months. GE is now rolling it out throughout the company, and it will replace our legacy Employee Management System (EMS) by the end of 2016.

At its core, the approach depends on continuous dialogue and shared accountability. Rather than a formal, once-a-year review, managers and their direct reports hold regular, informal “touchpoints” where they set or update priorities that are based on customer needs. Development is forward looking and ongoing; managers coach rather than critique; suggestions can come from anyone in an employee’s network.

A simple, contemporary smartphone app, developed internally by one of the company’s top IT teams to support the new approach, accepts voice and text inputs, attached documents, even handwritten notes. The sole aim is to facilitate more frequent, meaningful conversations between managers and employees and among teams.

A summary conversation between the employee and his or her manager still takes place at the end of the year, and a summary document, which both finalize and submit together, reflects on the impact achieved and provides a look forward. Just as they did under the EMS, managers still base compensation, promotion, and development decisions on these inputs (as well as a range of other factors, including business performance, internal and external benchmarks, and budgets).

But thanks to the new performance-development approach, the manager and employee can now draw upon a much richer set of data regarding an employee’s unique contributions and impact throughout the year. As a result, the year-end discussions are more meaningful and future-focused — and less fraught with expectations because they are simply part of an ongoing dialogue.

The new approach encourages flexibility and agility. Today, when priorities can change by the hour, we can’t wait until an EMS-style annual review to share 90% of our feedback on how an employee is performing against goals, what learning and development opportunities they should pursue next, or what they need to do to move to their next role. Managers and employees must be able to focus on contributions and impact within the context of current priorities. By emphasizing day-to-day development, we expect to drive better performance overall.

Our business, the Turbomachinery Solutions unit of GE Oil & Gas, provides solutions and services to upstream and mid-stream customers in seven vertical markets. We have 7,000 employees across three P&Ls, 11 functions, 12 regions, and 15 product lines. In recent years, our customers have faced a tough market; our challenge has been to ensure continued growth while reducing their costs rapidly. To do this, we needed all our teams, including Engineering, Procurement, and Manufacturing. to collaborate together better, something we knew year-end reviews alone could not achieve.

We jumped into the pilot by building a collaboration room where teams could engage and develop new ways of working. We gave them a shared goal on productivity and full autonomy and decision-making authority to figure out how to get there. Instead of each group working separately to optimize its portion of the process, as might have happened in the past, the new performance-development approached helped them work together to optimize the overall results. For example:

An Engineering team redesigned a cooling system for better performance and 50% lower cost.

The percent of purchase orders placed with a should-cost analysis increased 10X in one year to more than 60%, driving teamwork between Engineering and Procurement and significant savings. (Should-cost analysis is a methodology that builds an estimate of supplier costs associated with a given design. This approach sensitizes Engineering to cost tradeoffs in design decisions, and provides Procurement with a benchmark for negotiations with suppliers.)

Procurement and Engineering linked with Operations and Sales to improve forecasting and develop volume commitments with suppliers.

We’re finding that the new performance-development system is promoting trust between managers and employees — the foundation of high-performing teams. The insights we are giving and receiving are very different compared to the scrubbed and anonymous 360-degree reviews of the past. This is uncomfortable at first: It is difficult to truly self-reflect and spot the gifts embedded in the increased feedback. As managers, we need to be more vulnerable and show our teams we are growing to give them the license to do the same.

We’re also learning a new vocabulary, dispensing with sticky labels like “strengths” and “weaknesses,” which can follow an individual long past the point of applicability, and focusing instead on behaviors employees may want to “continue” as well as changes they may want to “consider” making. This new vocabulary focuses our teams less on backward-looking feedback and more on forward-looking actions. It frames feedback in a positive way.

For example, an engineer was asked to “consider” being more open to supplier recommendations and to visit the supplier for a day. He did, and in the following weeks the change was apparent. He championed a new approach that doubled our overall savings rate on budgeted project costs. Similarly, a procurement specialist was told to “continue” encouraging volume pricing and other such practices among vendors to increase savings.

While our business unit and our company are still in the early phases of rolling out the new performance-development approach, we view it both as a means to enhance individual and team success and a way to develop new leaders. The shift from “command and control” to “empower and inspire” is dramatic, and, as evidenced by our fivefold increase in productivity, it is yielding significant benefits for our employees and customers.

Ad Blocking’s Unintended Consequences

With 200 million downloads and counting, ad blockers are quickly growing in popularity. In my experience from working at an advertising technology company, the reasons are clear: they are easy to install and immediately effective, they make the web look cleaner and load faster, and they prevent advertisers from tracking user activity online. They are so effective that even advertising giants such as Google and Facebook are unable to get past them.

The debate on ad blocking is becoming increasingly polarized. Those who oppose ad blocking liken it to content piracy, arguing that exposure to ads is the price that readers must pay for free content. The other side of the debate is championed by companies who create ad blocking software, as well as online privacy activists. They criticize the effect of ads on user experience, but their biggest concern revolves around behavioral tracking, a practice used by many advertising companies to learn about users’ interests based on their web activity. Advertisers use this information to match users with ads they might find relevant.

What many people don’t realize, however, is the impact ad blockers have on the future of the web. The software prevents websites from generating ad revenue, which is often their main source of income. Placing ads next to content helps websites recover the sizeable fixed costs of creating content. Many advertisers pay a fraction of a cent each time an ad is shown to a visitor (contrary to the popular notion that ads only pay when clicked). But ad blockers cut off this revenue stream and make it difficult to offset even the running cost of storing and delivering content to visitors. According to one report, U.S. publishers lose more than 9% of ad revenue due to ad blocking. For some websites, especially those with tech savvy readers, the percentage loss may be as high as 50%. As ad blockers grow in popularity and ad revenues continue to drop, many websites may face a threat of financial collapse.

Diminishing ad revenues in the publishing industry should be a cause for concern for web users. First, it is likely to force websites out of business, hurting competition and reducing available content choices. The websites most likely to suffer are those that aren’t subsidized by print or television. This challenges the very notion of content democratization championed by the web. Second, it will almost certainly increase user costs as websites are forced to charge for content previously supported by ad revenue. Third, it may force the industry to push for regulation, placing the future of the web in the hands of legislators.

Supporters of ad blocking frequently cite its growing popularity as proof that the Internet community shares their concerns about tracking. But research suggests that most users do not understand tracking, nor do they have strong opinions about it. A study conducted by UC Berkeley to find out how Americans feel about tracking found that although users mistrust advertisers with their data, they also don’t understand what data is being collected and why. The study also highlights the difficulty of gauging public opinion on tracking since a large majority knows very little about the subject.

The digital publishing industry has taken concrete measures to resolve concerns voiced by the ad blocking camp. Large publishers are carefully vetting ads placed on their sites and employing teams of usability experts to manage their impact on user experience. They’ve subscribed to self-regulatory programs such as the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA), which aims to set consumer-friendly standards around behavioral tracking. The DAA mandates that advertisers and publishers disclose what data is collected and for how long, and asks that advertisers provide users with clearly visible methods to opt out of tracking altogether. Most large publishers now require advertisers to comply with DAA guidelines.

Unfortunately, these efforts have done little to resolve the impasse between the publishing industry and ad blockers, partly due to the fact that consumers do not have a clear seat at the debate table. Their side is predominantly occupied by ad blocking companies with entrenched commercial interests, which can prevent the dialogue from moving forward.

Innovation in ad technology has historically focused on solving the needs of advertisers and publishers. But data-driven personalization promises to transform advertising into a service that helps users discover relevant and well-timed information. Research has shown that while personalization in any system increases its usability and value, it also challenges user trust in the system. To build trust, the system must provide users with the ability to see how personalization works and the tools to control it. One reason why ad blockers are popular could be that they let users exercise an immediate choice, albeit one that may be damaging to their own interests. The advertising industry must offer a meaningful alternative to ad blocking by placing consumer preferences at the center of future innovation. Ad blocking companies may have a role to play in affecting positive change by choosing to invest in more sophisticated personalization controls.

Ultimately, users will decide whether advertising remains a viable business model for digital content. Unlike print and television, the web affords users the power to democratically shape the future. But to move beyond the current impasse with ad blocking, it is important that consumers understand the impact that it has on the publishing ecosystem. Websites should do more to educate their users about the consequences of using ad blockers and help them make an informed choice.

The Emotions That Make Us More Creative

Artists and scientists throughout history have remarked on the bliss that accompanies a sudden creative insight. Einstein described his realization of the general theory of relativity as the happiest moment of his life. More poetically, Virginia Woolf once observed, “Odd how the creative power brings the whole universe at once to order.”

But what about before such moments of creative insight? What emotions actually fuel creativity?

The long-standing view in psychology is that positive emotions are conducive to creativity because they broaden the mind, whereas negative emotions are detrimental to creativity because they narrow one’s focus. But this view is too simplistic for a number of reasons.

It’s true that attentional focus does have important effects on creative thinking: a broad scope of attention is associated with the free-floating colliding of ideas, and a narrow scope of attention is more conducive to linear, step-by-step goal attainment. However, emerging research suggests that the positive vs. negative emotions distinction may not be the most important contrast for understanding attentional focus. Over the past seven years, research conducted by psychologist Eddie Harmon-Jones and his colleagues suggests that the critical variable influencing one’s scope of attention is not emotional valence (positive vs. negative emotions) but motivational intensity, or how strongly you feel compelled to either approach or avoid something. For example, pleasant is a positive emotion, but it has low motivational intensity. In contrast, desire is a positive emotion with high motivational intensity.

The researchers showed participants funny video clips of cats (triggering emotions of low motivational intensity) and clips of delicious-looking desserts (bringing out high motivational intensity). Even though both evoked positive emotions, the cat videos, which were simply amusing, broadened the mind (measured by subjects making more holistic matches to a target stimulus), whereas the dessert clips that carried higher motivational intensity narrowed subjects’ scope of attention (subjects made more detail-oriented matches to a target stimulus). And it was similar when looking at video clips that tapped into negative emotions: sadness (a state of low motivational intensity) broadened attentional focus, whereas disgust (a state of high motivational intensity for avoidance) narrowed focus.

Motivational intensity, they concluded, was a more important variable affecting scope of attention than the mere experience of positive or negative emotions. Presumably, this is because low motivational states facilitate the search for new goals to pursue, whereas high motivational states focus us on completing a specific goal. So next time you want to keep an open mind and see the big picture, it’s probably best if you’re just in a pleasant (or even sad) mood. If you are too passionate about the activity, you may miss the forest for the trees. If, however, you really need to buckle down and focus on making a new idea practical, high motivational intensity can be just the ticket.

At the end of the day, the ability to broaden attention and the ability to narrow attention are both key contributors to creativity. A recent neuroscience study led by Roger Beaty (and which I was a collaborator on) suggests that creative people have greater connections between two areas of the brain that are typically at odds: the brain network of regions associated with focus and attentional control, and the brain network of regions associated with imagination and spontaneity. Indeed, the entire creative process—not just the moments of deep insight— involves states of euphoria and inspiration as well as states of calm, rational focus. Creative people aren’t characterized by any one of these states alone; they are characterized by their adaptability and their ability to mix seemingly incompatible states of being depending on the task, whether it’s open attention with a focused drive, mindfulness with daydreaming, intuition with rationality, intense rebelliousness with respect for tradition, etc. In other words, creative people have messy minds.

Other research has also found that people who reported experiencing extreme or intense emotions on a regular basis scored higher on measures of creative capacity than those who simply reported feeling positive or negative emotions. There’s something about living life with passion and intensity, including the full depth of human experience, that is conducive to creativity. In my own research, I found that “affective engagement”— the extent to which people are open to the full breadth and depth of their emotions— was a better predictor of artistic creativity than IQ or intellectual engagement.

We are also rarely purely happy or purely sad— we tend to experience mixed emotions. Research scientist Christina Fong at Carnegie Mellon University has investigated the effects of “emotional ambivalence”— the simultaneous experience of positive and negative emotions— on creativity. Fong’s research suggests that simultaneously experiencing multiple emotions that are not typically experienced together (e.g., excitement and frustration) signals “that one is in an unusual environment where other unusual relationships might also exist.” This increased sensitivity to unusual associations is another important contributor to creativity.

Prior research hints at some situations that tend to increase emotional ambivalence: Women who are in higher-status positions report greater emotional ambivalence than women in lower-status positions, and when people are engaged in organizational recruitment and socialization, they report higher levels of emotional ambivalence. Fong suggests that perhaps managers “would benefit from scheduling creative thinking tasks for these time periods or could assign creativity tasks to new organizational members (who are likely undergoing socialization processes).” In other words, it may be during these moments of high emotional ambivalence when the emotions of employees are ripe for creativity.

Fong’s research also suggests that emotional ambivalence and the unusualness of one’s environment may go hand in hand—and that employees who believe they are in an unusual environment can show increased creative thinking. Highly innovative companies such as Disney and IDEO are well aware of this, as their employees benefit from such unusual working environments. IDEO’s workplace in Palo Alto, California has airplanes and bicycles suspended from the ceiling, plastic beaded curtains used as doors, and Christmas tree lights on display all year round. Everywhere you go are toys, gadgets, and prototypes from past projects. Indeed, multiple psychological studies suggest that a crucial trigger of creativity is the experience of unusual and unexpected events. Unexpected events can certainly mix emotions, and mixed emotions, as Fong as shown, can increase sensitivity to unusual associations and ideas.

Taken together, the latest research on the role of emotions in creativity suggests that instead of focusing exclusively on bringing out positive emotions among employees — or attempting to dispel negative emotions — managers may want to consider additional factors, such as whether the environment brings out emotional ambivalence (Is the environment unusual? Will it tap into a wide range of seemingly contradictory emotions?) and motivational intensity (Will it broaden or narrow someone’s focus?) when trying to stimulate creativity. It’s time to move beyond such simplistic black-and-white notions of the role of emotions in innovation, and instead embrace the inherent messiness of the creative process.

Author’s note: Thanks to Adam Grant for bringing many of these studies to my attention.

August 11, 2015

Why Google Became Alphabet

The company that yesterday was known as Google is now a collection of separate companies, owned by a new holding company called Alphabet. The “Google” brand is the largest of those companies, and it includes search, advertising, maps, apps, YouTube, and Android. The company’s less related endeavors – the biotech research project Calico, the Nest thermostat, the fiber internet service, the “moonshot” X lab, Google Ventures, and Google Capital — are all now separate companies housed under Alphabet.

Why? And will it work?

The Google founders are already being called Warren Buffets-in-training. But as always, the company defies easy comparison. Google is not becoming Berkshire Hathaway, at least not exactly. It’s trying out something else entirely. Largely in an attempt to placate investors while preserving the founders’ unique theory of what their company is.

The restructuring is clearly a response to Google’s stagnant share price and investor unease. My argument has long been that Google’s current theory of value creation is essentially to funnel its vast profits from the search and advertising business into the hiring of strong talent, and then to give employees wide latitude to explore and pursue whatever they wish. This is embodied not only in the pattern of rather unrelated investments and acquisitions, but in policies about hiring, salaries, and 20% free time.

Investors have been uneasy about this strategy, but Larry Page and Sergey Brin have also composed a corporate governance regime that insulated them from much shareholder pressure for change. Eventually, with growth in search advertising slowing, investors’ dissatisfaction manifested itself in a stagnant stock price. And in recent months the company has taken steps to rein in some of its investments, slowing growth in expenses, and also tightening the reins on the 20% free time policy. These were the beginnings of a shifting direction at Google.

Analysts had their own problem with Google’s structure: its bundle of businesses was extremely difficult for them to evaluate. The primary challenge for analysts has been that the performance of the main business was not transparent—the financial returns of the search engine and advertising business could not be observed separately from the investments in all of the new businesses. The new structure ensures that there will be, at a minimum, independent accounting numbers produced for the Google business, and perhaps for the others as well.

Investors will inevitably push for more. The market’s response has so far been positive, with the stock price up 6%. And I suspect it will also have a longer-term performance impact, as greater transparency of both its cash flows and investments prompts greater discipline and accountability. But I doubt this move will fully pacify the uneasy investor. While this new organizational form increases transparency, that transparency only further illuminates the disconnect between Alphabet’s various businesses. It simply highlights the question of why the various businesses are bundled together. Investors are still buying the whole collection of projects, only now they’ll be able to see clearly just how much search advertising is subsidizing the rest.

As for the comparison to Berkshire Hathaway, there are some parallels. Berkshire Hathaway is a publicly traded company that is run like a private equity firm. It, like Alphabet, is a portfolio of very unrelated businesses. However, the important distinction is that Berkshire Hathaway’s businesses are generally cash producers and Berkshire’s task is to improve on the cash they already generate. Alphabet will be more like a cash cow coupled to a venture capital firm, investing in early stage and in some cases highly capital-intensive new ventures.

Berkshire Hathaway has assembled a group of investors who are confident in its theory of value creation. That’s the challenge that Google-as-Alphabet still faces. Who wants to simultaneously invest in a search engine, longevity research, thermostats, and drones? The new structure will make that investment proposition more transparent, but the company still needs to convince investors, as Berkshire has, that their theory of value creation makes sense.

Are Uber and Facebook Turning Users into Lobbyists?

Facebook’s News Feed stream is an incredibly valuable piece of digital real estate, without historical precedent. Over 968 million people access it daily. Close to 1.5 billion people view it at least monthly. The web traffic the stream generates has reshaped the journalism, gaming, and music industries, among others.

This week, Facebook took advantage of this asset for political purposes. At the top of the News Feed, users located in India saw a company-issued request to promote Internet.org, the company’s controversial global connectivity effort, to their elected leaders.

If a user agreed to the noble goal of free connectivity for their fellow citizens, they were directed to tell their Member of Parliament to support Facebook’s developing world program:

Internet.org seeks to connect billions of people in the developing world to the internet. It’s controversial because “the internet”, in Facebook’s plan, initially consisted of a limited walled garden curated by Facebook itself. Outside developers are now welcome, but must apply, and must play by Facebook’s limiting technical rules in order to be served up by Internet.org’s delivery platform.

Facebook has similarly leveraged the News Feed for general purpose voter information tools on Election Day in the United States. Facebook’s proven power to affect voting turnout alarmed some, but that concern was largely hypothetical. With this week’s in-feed promotion of Internet.org, Facebook crossed the line between promoting general civic engagement and sponsoring citizen communication by supporting a specific company program favorable to its commercial interests.

Leading technology companies are increasingly soliciting their users to take political action on their behalf to defend controversial business models from regulation, support new programs, and promote their moral values in active political battles. Many of the companies inserting politics into their user experience operate popular social platforms themselves. In directing a flood of political attention toward their targets, these web companies are reshaping attention online so that it flows less like a stream, and more like a canal.

Such advocacy is mostly legal, at least up to a point. In the US, companies voicing political content, or asking citizens to contact their officials, is well-covered under the First Amendment. The situation grows more complicated if companies’ action is considered an in-kind contribution to a candidate or elected official. An Uber ride carries a real commercial value, and donating them en masse to get users to a candidate’s rally, for example, could fit the FEC’s definition of an in-kind contribution (providing an object or service, “anything of value”).

From a transparency point of view, in-app advocacy is arguably an improvement over the status quo in corporate-sponsored public outreach. Not only does it rely on actual citizens, it’s also crystal clear who’s asking us to take action. The tech companies mobilizing their users are owning the request: you find the call to action on their website, in their app, or in an email with their branding. Relative to the fleet of disposable non-profit astroturfing groups created by industry over the years, taking an Uber to a pro-Uber rally is refreshingly direct.

Still, we’re entering a brave new world where the creators of technology platforms can activate billions of users to specific political action of their choosing. We’re being introduced to a new lever of corporate influence on democracy. And Facebook is by no means the only example.

Uber users in New York City found the ride service’s menu of options a little more crowded last month. In addition to a variety of available vehicles and an experimental food delivery service, a new option was presented that read simply, “DE BLASIO”. This new ‘feature’, named after Mayor Bill de Blasio, offered 25 minute wait times and a button inviting the user to “See what happens”. Upon tapping, the user was invited to contact the Mayor and City Council to add their name to a list of people upset by their proposal. The City sought to cap Uber’s growth at 1% per year while they studied the ride service’s effect on traffic congestion in Manhattan. Uber’s gambit succeeded, along with a more traditional barrage of TV ads, mailers, and robocalls: the City backed off the cap proposal. Regardless of the merits of the political battle, Uber’s in-app attack ad set a new bar for the lengths to which a tech company was willing to push its users toward self-serving political action.

The dating site OKCupid brought its moral values to the attention of its users when it asked customers using the Firefox browser to switch to a competitor because of the position Mozilla’s then-CEO had taken on gay marriage in California years earlier. OKCupid seeks to position itself in the dating site market as the place where anyone can find a partner, so this moral stance and customer interruption also served to enhance their brand with the rapidly growing population of people who support gay relationships.

The watershed moment in confronting website visitors and app users with a specific political call to action was the online battle against two pieces of internet legislation: the Stop Online Piracy Act and the PROTECT IP Act (SOPA and PIPA). Many of the web’s premier properties engaged in the tactic to varying degrees: Tumblr, Wikipedia, and Google promoted the cause with homepage takeovers and supportive links and emails. The action prompts covered a spectrum of assertiveness: Google emailed users who had taken part in other net neutrality actions, while Tumblr funneled visitors to the site down an action path that quickly connected people to their congressional representatives by phone (generally considered a higher bar of engagement by Capitol Hill staffers). The decision to place this political action in front of millions of users was made by the relatively few people with the ability to do so.

There’s a business logic to mobilizing customers. To the extent that a company’s users are champions of the product in question, the political action is mutually beneficial to customer and company alike (although perhaps not equally so). It would make sense that a customer who enjoyed Aereo’s cloud-based access to their cable programming would like to express their feelings in the legal battle that went all the way to the US Supreme Court and eventually shut down the company.

So-called “sharing economy” companies have been at the forefront of mobilizing their users to their defense, mostly out of necessity. Uber, Airbnb, Lyft, 23andMe, and other companies working around or, in some cases, outright ignoring existing regulations have found customer loyalty to be an asset in their conversations with lawmakers and regulators.

The strategy has been, as Union Square Ventures’s Nick Grossman writes:

New startup delivers a creative and delightful new service which breaks the old rules, ignoring those rules until they have critical mass of happy customers; regulators and incumbents respond by trying to shut down the new innovation; startups and their happy users rain hellfire on the regulators; questions arise about the actual impact of the new innovation; a tiny amount of data is shared to settle the dispute. Rinse and repeat, over and over.

Grossman argues for lower government barriers to disruptive business models, with stronger commitments from companies to provide data to fuel regulations informed by these companies’ actual impact. In the meantime, faced with rules that threaten their very business models, sharing economy companies are leveraging every asset they’ve got in the regulatory battles, including us.

In going directly to their users, technology companies are participating in the very direct-to-customer media channels they’ve created. If the Obama Administration can create its own internal media studio and increasingly bypass the professional media and reach citizens, why not the companies operating the world’s most popular websites and social media platforms? If the end goal is to reach lawmakers, driving thousands of citizens to contact their offices is an effective way to do it. The companies own the access to the channels of communication. Others must pay for the same access, and in many of these cases, the placement of the message is so valuable, it isn’t even for sale.

Another issue is that the simplified action prompts never include countervailing messages. Companies do not seek to host a conversation around nuanced and emergent issues about how society should adjust to disruptive technologies; they seek only to efficiently channel political action with all of the design and conversion-testing tools in their arsenal.

This was the primary complaint of an official on the receiving end of corporate-funneled advocacy in Toronto last week. Porter Airways created an online poll asking the public where they’d like to fly and promoted it on Facebook. Respondents were immediately prompted to weigh in by calling their city councilors to lobby for more runways at Toronto City Airport. One city councilor opposing the runway was concerned that the citizens prompted to call about their desire to fly non-stop to new destinations hadn’t been informed of any of the downsides of new runway construction. According to the airline’s campaign site, over 50,000 people have signed on.

Opposing viewpoints matter, a lot, if they’re coming from a company’s other customers. Companies may choose to remain silent on issues they’d otherwise be vocal about rather than advocate for a cause that would damage a relationship with a major customer. Business-to-business companies selling to other enterprises are more susceptible to the conflicts of interest that can arise between customers.

There’s also the court of public opinion to keep in mind, for business-to-consumer companies especially. For consumer brands, public perception can act as a limit on corporate political speech—why promote a specific candidate if a majority of your customers will disagree with you? Companies risk alienating entire groups of consumers if they take stances on generally divisive questions.

Finally, there’s the issue of aligned interests. Sometimes, the company and its customers simply have divergent or entirely contradictory interests, and in these cases, we’re unlikely to see companies inviting customers to weigh in. Airbnb regularly asks its users to advocate for the site to remain legal in their cities, but did not invite them into deeper discussions about how the company operates in those cities, such as who’s responsible for the taxes.

The economist Herbert Simon posited that in a society where many of our material needs have been satisfied, people’s attention becomes the limited resource. Limited resources are valuable. This theory is borne out by the immense value of the industries that can deliver our eyeballs to the highest bidder: advertising and public relations. Many of the web’s largest platforms have been built on the fundamental exchange of our attention, in the form of advertising, for free access to products and services. We live in an attention economy, and our apps increasingly have our attention. More and more of our waking minutes are spent looking at screens of various sizes. Technology companies’ ability to use that prime digital real estate to solicit specific political actions from their users is a modern and very real form of power, particularly when it’s wielded by companies as central to our attention as Facebook.

With the 2016 presidential campaign heating up and sharing economy battles reaching a head, we can expect to see many more examples of companies mobilizing customers. I’ll be tracking them here. Technology continues to give us new ways to express ourselves. Democracy depends on that expression. And companies are increasingly seeing the business value in driving this expression themselves.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers