Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1262

August 14, 2015

Being Professionally Personable on Facebook

When people talk about using social media to advance their careers, they’re usually talking about LinkedIn, Twitter, or maybe their blog. But the reality is that more people use Facebook than any other social network, which means that sooner or later, you need a Facebook strategy for your career.

Companies use Facebook pages to harness the power of its network to reach business goals, and individuals can do the same thing: particularly if you’re an author or other recognized expert, you can create a Facebook page for your professional identity, and promote that page just like any other brand presence.

But most of the time we’re on Facebook we are using our personal accounts, so especially if you’re open to friending your colleagues it’s crucial to think about how you’ll manage your personal account in relation to your professional identity. That’s because life on Facebook increasingly spans both the personal and professional. We use Facebook to share our professional news: career accomplishments, job changes, requests for business advice, or posting links to industry-related content. We also use Facebook to share our personal news: stories about the kids, photos of the family, hysterical YouTube cat videos, and political rants.

When these two worlds collide, it can get awkward. Your boss may have second thoughts about your prospects for professional advancement if you like posting late-night ramblings. Your college buddies may simply unfollow you if you keep filling up your Facebook feed with industry updates or plugs for your business. So how do you keep these worlds separate, without cutting yourself off from either the personal or professional benefits of Facebook? Here’s what I recommend:

Use your restricted list. Facebook automatically provides you with a “restricted” list: a list of people you are friends with, but who don’t get to see the content you’re only sharing with (good) friends. This is the answer to managing all those people who send you friend requests you feel like you have to accept (like your boss), but who you don’t actually want to privilege with the intimate details of your day-to-day life. A good rule of thumb is to put anyone you know professionally on your restricted list, so that you don’t share your friend updates with those people. (For step-by-step instructions on how to use the restricted list, see this post.)

Create your own lists. In addition to the broad distinction between friends and the people on your restricted list, you can make lists that include specific people and have specific viewing permissions. I have a small list of people I call my “kid sharing friends”; they’re the only people who see photos or news about my kids, unless it’s a story that I think will be relevant to a wider audience. It’s not that I think my Facebook friends list is full of child predators; I just know that not everybody recognizes how utterly fascinating my children are. You can use the same approach to target other audiences: professional colleagues, co-workers in your company, best girlfriends, or fellow baseball enthusiasts.

Target each post. Whenever you’re posting to Facebook, get into the habit of thinking about who you want to share that content with. Facebook’s posting interface includes a little button right beside the “post” button, where you can choose to share a post with “public,” “friends” (i.e. everyone who isn’t on your restricted list”, “only me” (something you’re just recording for your personal reference). You can also use the “more options” button to choose one of the custom lists you’ve created, or even to name the specific people who should see this particular post. I generally make content “public” when it’s related to my professional interests, so that even people on my restricted list get to see my professional news and insights. The exciting details on what I ate for breakfast or how I am feeling about my hair are limited to my friends.

Classify your colleagues. One of the things that’s tricky about putting all your colleagues on your restricted list is that some of your colleagues are likely personal friends. When you get a friend request from a colleague, think about which category they fall into: someone you don’t want to know better (deny the request, or put them on the restricted list), someone you think of purely as a colleague (restricted list) or someone you are really, really close with (friend list). Just remember that if you have any co-workers on your un-restricted friend list, you’ll need to picture that person reading every single thing you share — so think twice before posting a gripe about your job.

“View as colleague.” A good way to audit the way your Facebook feed may look to your colleagues is to use Facebook’s “view as” feature. Go to your profile page (by clicking your name in the upper-left corner of your Facebook window) and then choose “view as” (from the menu under the three dots beside the “View Activity Button” at the bottom of your cover image). Choose one person who is on your restricted list, and see what your Facebook profile looks like to that person; do the same thing for someone on your un-restricted friend list. If you’re not comfortable with who is seeing what, tweak the past posts where you’ve over-shared (you can retroactively change the audience for any post, though you can’t ensure it hasn’t already been seen) and be more careful about what you share with which audience in the future.

Set aside times to review your friend requests. One problem with relying on the restricted list is that it makes accepting friend requests a slightly more complicated process. Instead of just accepting a friend request, you have to accept it, and then edit the lists that friend is on (if you’re planning to add someone to your restricted list). So you can’t just accept friend requests as they come in; you’ll need to aside aside some time every week or so when you can review incoming requests and decide who goes on which list.

Tweak your defaults. If you share to Facebook from your phone, check the default privacy settings on your photo uploads. Set the default to the narrowest audience you ever share pictures with; it’s better to accidentally share a post too narrowly than too widely.

Using all of these tactics can ensure you don’t accidentally overshare with colleagues — without denying yourself the pleasure of connecting with them and with your friends. Better yet, once you’ve done a good job of quarantining your personal content on Facebook, you can actually use it to keep in touch with the people you care about, without constantly worrying about the professional impact of each post. When you’re able to use the world’s largest social network for both professional and personal reasons, you’ll rediscover social media at its best: not as a platform for self-promotion, but as a platform for genuine human connection.

Turning Your Complex Career Path into a Coherent Story

ANDREW NGUYEN/HBR STAFF

It’s hard when you’ve had a non-standard career trajectory and you want to re-enter the work force, move to a higher position, or enter a new field. Will a marketing firm see you as a good leadership candidate if you’ve always been a professional fundraiser and small business owner? Would a medical devices company view you as capable of learning their product line if you’ve worked in the automobile or hospitality industries? Will a corporate hiring manager take you seriously if you’ve spent the last 10 years mostly volunteering? In these cases, you may not be the slam-dunk candidate. But you’re more likely to convince an enlightened hiring manager, venture funder, or board member if you can articulate how all of your varied experiences and skills actually make you a better candidate than the conventional applicant.

How do you do that? You tell your story in a way that connects the dots. Unlike a more typical candidate, you have to assure that your audience can identify the thread that runs through your career narrative and make sense of your varied skills, training, experiences, and choices.

First, if others are ever going to understand your trajectory, you have to make sense of it yourself. Identify the themes that run through your professional life. This will take some concentration and reflection. In fact, it may be something that a long-time friend, colleague, or family member identifies before you do:

“You’ve always liked building things, ever since you got a set of wooden blocks for your birthday.”

“You never settle for the status quo; no matter where you’ve worked and what you’ve done, you’re always looking to create something new.”

“You motivate people, whether you’re running the PTA, leading a team at work, or finding people to join the town council.”

Not long ago I recognized a coherent theme in my working life and I’ve shared it with my career-coaching clients as an example of how to capture that story. I’d taken Latin all through high school and loved translating the ancient tale of the Aeneid into something resembling modern English. I majored in literature in college, reading in Italian and French, and almost accepted a job as a translator after I got my degree, but went to work as a fundraiser for my university instead. I went to business school a few years later and then worked in marketing. Soon after I returned to institutional development (the uptown name for fundraising) while getting degrees in counseling psychology. When I finished my PhD, I continued my private practice — but also added career counseling and executive coaching to my professional mix.

Told like that, it seems like a trail of somewhat disconnected experiences. But what ties it all together is the process of translating; translating a text from one language to another, translating the significance of an academic program to a potential donor, translating the benefits of a product to consumers, translating a client’s concerns into possible ways forward, and helping clients to translate their own feelings, thoughts or capabilities to others. Eureka!

Ask yourself: what are the kinds of tasks that I like to do? Consider the kinds of processes and activities you’ve enjoyed most in school, at work, as a volunteer, a family member, or friend. Think about, or ask others, what may tie these together. Without a nod to a specific position or title, you may find that the general motif is being an effective listener, building relationships, solving complex problems, re-thinking standard ways of operating, creating a new vision, or motivating people to take action. This is what you’ve most enjoyed (and therefore tend to do well, because you’ve spent time at it). This theme that emerges from your experience may tie together a wide variety of activities with a common thread that unites them all.

Once you’ve identified your own theme, the next step is to tell your story. Craft it and take any opportunity to share it with those who can help advance your career: hiring managers, funders, colleagues, publicists, or the acquaintance you meet at a networking event or a local barbecue.

Forget titles, positions, and industries. Focus on what you’re best at, using terms that pull together your diverse experiences, those seemingly unrelated industries and the serendipitous opportunities you’ve had to learn something new. Don’t be humble: Leave off the: “Well, I’ve never done exactly this before, but…”. Instead, say with confidence, “Here’s what I do well”.

A few examples:

“I’m a relationship builder, and I’ve always been commended for my ability to listen to people’s needs and help craft a solution for them.”

“Complex problem-solving is exciting to me. I love to delve into thorny problems, work hard at teasing out the issues at hand, and get to the heart of the matter.”

“I thrive on creative thinking, whether I’m coming up with a new product or a new way of working. It’s impossible for me to settle for the status quo when I see that my team can create something better.”

You can talk about previously-held positions or companies later. First, establish the theme you want your audience to understand before they get stuck wondering, “But does he/she have enough time/experience/training?” You’ve connected the dots so they don’t have to.

This theme can then become your proverbial calling card. Include it:

At the top of your resume, at the beginning of your elevator pitch, and in your descriptions to recruiters and in job interviews.

In your pitch to possible funders, your marketing materials, and conversational openers.

In your request to your boss for a promotion.

After all, you want to assure that others understand your competencies and the crystal clear rationale for your landing that job, that funding or that promotion. You can’t expect anyone else to do that for you, though: you have to connect the dots.

Create a Culture Where Difficult Conversations Aren’t So Hard

Photo by TOM EVERSLEY

I worked as a consultant for many years before becoming the CEO of Red Hat. One of the most surprising aspects of that work was that people would open up to me, an outsider, about all the elephants in the room — but they were too polite or embarrassed to call out the obvious issues or blame their peers inside their own organizations. My fellow consultants and I would sometimes joke that just about every individual inside a company could immediately tell you what was going wrong and what needed fixing. But whenever everybody convened for a meeting to point out those very issues, you wouldn’t hear a peep about anything that could be perceived as negative. To our amazement, they were more open to hearing feedback from us, the outsiders, than from their own colleagues.

Though this might be good for the consulting business, shouldn’t companies be having candid conversations — since they almost always know the solution to their problem — on their own? Wouldn’t the ability to share open and honest feedback throughout the organization improve their chances of addressing their issues, and more quickly?

These are the questions that keep me up at night as a CEO. Luckily, the practices of open dialogue and providing constant feedback were already in place and part of Red Hat’s DNA when I joined the company. Because Red Hat sprang from the world of open source software — a community whose members pride themselves on delivering open and honest feedback — having candid, and what others might call difficult, conversations is the norm. We debate, we argue, and we complain. We let the sparks fly. The benefits of operating this way are immense because we are able to tackle the elephant in the room head on, but this kind of culture is hard to build and maintain, especially as companies grow.

Fortunately, we’ve learned a few tips from working in open source communities about how to create and manage a vibrant feedback loop within our organization. Once you establish the practice of sharing regular feedback across the company, it begins to function like a flywheel. It’s hard at first to get it moving. You’ll need to do some substantial pushing and monitoring to get the wheel spinning. But before you know it, you’ll find that the wheel begins to turn all on its own using its own momentum.

We’ve found that there are three key things you need to tackle to get your feedback loop spinning; this is the foundational work that gets everyone pushing in the same direction and that creates a safe environment where everyone feels comfortable having difficult conversations. As a leader, you must role model these behaviors, and encourage them at every level of your organization:

Show appreciation. It surprises me that when people use the term “feedback,” it often comes with a negative connotation. Why can’t feedback also include positive aspects as well? A great way to start a feedback loop, therefore, is to actually begin by recognizing the good work someone has done. What we’ve learned is that one key to creating a self-sustaining feedback loop is that you need to spend much more time recognizing and appreciating someone’s efforts than you do criticizing them. At Red Hat, I’d wager the ratio is something like 9:1 (research typically suggests a 3:1 ratio of positive to negative). You’re far more likely to have someone from outside your department thank you or tell you that you did a great job than anything else — and they mean it. That’s how you can begin to establish trusting relationships that are strong enough to withstand any constructive criticism that might come along.

Open up. We all have the tendency, when we think we’re under attack, to circle the wagons and protect our department and ourselves. You can literally read someone’s body language when this is happening — they fold their arms, furrow their brows — and you can almost see the steam coming out of their ears. But if you want to build a feedback loop in your business, you, especially as a leader, need to lead by example and open yourself up to hear what people are saying. If someone in another department is convinced you’re not listening to them, what makes you think they’ll listen to anything you have to say to them? Yes, opening yourself up makes you vulnerable. But that’s also why we preach the idea that “you aren’t your code,” which is another way of saying that we all need to be able to process constructive criticism without taking it personally. If you can do that, you can create the kind of open and honest culture that is capable of tackling the thorniest of issues together. And you’ll be amazed that when you do listen to someone’s feedback, and take action on it, you’ll increase that person’s engagement level in his or her work.

Be inclusive early and often. One of the interesting complexities inside most organizations, especially larger ones, is that they establish departmental or functional “silos” for reasons of efficiencies. And yet, they inadvertently create mistrust and misinformation by doing so. It often results in an “us-versus-them” type of situation that results in a departmental blame game. That’s why a big part of building an effective feedback loop is to get people from all over the organization involved as soon as possible in your decision-making, whether you work in finance, IT, or human resources — and often. It’s far easier and effective to gather feedback from other departments on smaller incremental issues than waiting until you’re father along where the stakes and risks have increased. If you do get some constructive criticism early on, you can more easily change course while also increasing trust and buy-in from the rest of the company.

So unless you’ve got the budget to hire a consultant to do the straight talk for you, it’s time for you to lead the way by encouraging difficult conversations inside your organization. If you can tackle these three steps up front, you’ll find your feedback flywheel will begin spinning faster and faster. Otherwise, that elephant in the room is bound to trip you up sooner or later.

The Branding Logic Behind Google’s Creation of Alphabet

The Google brand is one of the most valuable brands in the world. In 2014, Interbrand placed a valuation of the brand at $107.43 billion, only trailing the Apple brand in value.

A reasonable person might ask, if the Google brand is so well-known, why muddy the waters by introducing a new parent brand, Alphabet? To help answer this question, the stories of two other iconic brands – Starbucks and Virgin – are instructive.

Starbucks

Starbucks offers a cautionary tale. There is a danger to any brand from diluting its brand promise or overextending into areas where that brand promise is not relevant.

At the turn of the century, having experienced two decades of spectacular growth, Starbucks began to view itself as more than a brand about coffee or a coffee experience, but as a “lifestyle brand” that transcended those roots to reflect more of an attitude that would be relevant to many other categories. Reflecting this broader viewpoint, the company began to expand its market footprint, by, for instance, investing in a start-up that planned to sell furniture via the internet.

Concerned about the company’s lack of focus, Wall Street hammered the Starbucks stock, resulting in a drop in share price of 28% in one day – a $2 billion loss in the company’s market capitalization. Hearing the message from the financial analysts, Starbucks went “back to basics” to focus more on its core business of coffee and a coffee experience and reaped the rewards, maintaining their price premiums and profit margins throughout the subsequent economic downturn.

However, as the decade wore on, the company made a series of decisions – using bagged coffee rather than freshly ground coffee, no longer scooping fresh coffee from the bins and grinding it fresh in front of the customer, blocking the visual sight line customers previously had to watch their drink being made, and so on – that collectively resulted in a significant loss of the personal experience that consumers had with Starbucks and its baristas. By failing to deliver on the Starbucks brand promise of providing the “richest possible sensory experience,” sales naturally slumped as unhappy customers chose to go elsewhere.

Again, Starbucks responded by going “back to basics,” making a number of changes such as introducing new coffee-making machines and selling coffee paraphernalia in stores again, bringing back freshly roasted coffee and introducing new blends (Pike Place & Blond), and famously closing all 7,100 U.S. stores in February 2008 for three hours to re-train baristas. As founder Howard Schultz remarked, “We lost the focus on what we once had, and that is the customer.”

Through these different episodes, Starbucks has come to appreciate the importance of keeping a tight focus and delivering on its brand promise.

Virgin

Virgin has taken an entirely different tack from Starbucks by directly expanding its corporate brand into an incredibly diverse set of industries. Internally, their businesses are organized into seven categories: Entertainment, Health & Wellness, Leisure, Money, People & Planet, Telecom & Tech and Travel. In all that they do, Virgin’s brand promise is to be the “champion of the consumer” – to go into categories where consumer needs are not well met and to do things differently and do different things to better satisfy them.

Such an abstract brand promise has potential relevance across a vast array of categories. Actually delivering on that promise, however, has proven to be extremely difficult, as evidenced by the problems or even failures the Virgin brand has encountered across a whole set of product and service markets. Consumers evidently felt their needs were met sufficiently well enough that they didn’t need a cola, vodka, or bridal apparel from Virgin, among many other products and services which Virgin has introduced and subsequently withdrawn. The danger to Virgin of continuing down that hit-or-miss path is that as young, hip or cool as their brand might be now, repeatedly violating their brand promise will raise doubts in customers’ minds and weaken their bonds to the brand over time.

Think of the equity of a brand in terms of a bank account. When the brand does “good things,” such as introduce a highly innovative new product, a deposit is put into the brand bank account. But when the brand does something “bad,” such as introduce a new product that fails to satisfy or excite consumers or even fails, that results in a withdrawal from that account. Virgin has benefited from the launch of some highly successful new products through the years –Virgin Megastores, Virgin Atlantic, and Virgin Mobile among others – that placed huge deposits in their brand bank account. If they are not careful, however, they run the risk of drawing down that account with too many compromises of the brand promise. The recent tragic crash of a Virgin Galactic test flight underscores the dangers associated with adopting such an expansive corporate brand strategy and the potential tarnishing of the brand that could result.

In contrast to Starbucks, the Virgin brand strategy is a high-wire act that requires incredible management and marketing skill and creativity.

Google is wise to learn from these two brand histories. Up to this point, the company has employed both a “branded house” strategy, where they have used their Google corporate brand one way or another across a broad range of products (such as Google Glass and Google Play), as well as a “house of brands” strategy where they assembled a brand portfolio of different brands where the Google brand is not present (such as with Nest, Calico, Fiber, etc). Hybrid brand strategies are not uncommon, but it is important to ensure that all aspects of the brand strategy are designed and implemented properly.

In Google’s case, they have no doubt come to the realization that as strong as the Google brand is, like all brands, it has boundaries and takes on more meaning and value in certain areas. Just as a “rich, rewarding coffee experience” is at the core of the Starbucks brand, “relevant, available information” is at the core of the Google brand, following directly from its stated corporate mission “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Their search product exemplified that brand promise as well as the related different extensions that followed, maps, books etc.

As Google moved farther and farther afield, however, into areas such as driverless cars and curing diseases, the relevance of that brand promise and corporate mission seemed remote and fairly removed. The brand was being associated with too many different areas, potentially blurring its meaning and creating confusion as to its purpose for both consumers and financial analysts.

With the creation of Alphabet, Google has codified and clarified this dual brand strategy that allows them to have the best of both worlds – a tight focus with the Google brand, as well as a broad portfolio approach with the Alphabet brand. Alphabet will allow the Google brand to focus more directly on its corporate brand promise and mission. That sharpened focus will benefit their business partners, drive profitability, and be rewarded by financial analysts.

Separation also allows the Alphabet brand to serve as an umbrella brand over a diverse portfolio of individual brands. The Alphabet brand would be in the background to the individual brands making up the portfolio, although it could be used, if desired, as an implicit or explicit endorser brand.

Fundamentally, brands survive and thrive on their ability to deliver on a compelling brand promise – to provide superior delivery of desired benefits in ways that can’t be matched by another other brand or firm. By aligning their brand architecture strategy with their brand promise and product development strategies, Google has brought needed clarity to the consumer marketplace and to financial markets.

How to Get Feedback When No One Is Volunteering It

You are probably not getting the feedback you want or need, according to our research conducted with SuccessFactors and Oxford Economics. Less than half of respondents in our 27 country survey say that their manager delivers well on providing feedback either formally during their performance reviews (49%) or informally on a regular basis (43%). It gets worse.

The higher you go in an organization and the more successful you become, the less likely it is that people will voluntarily offer you feedback. You will receive less of it in general, and it may be so diffused that it’s unrecognizable or unhelpful. As a result, the search for genuine feedback becomes more and more your own responsibility over the course of a career.

If you can’t rely on your manager to hand you feedback prettily packaged and perfectly delivered, it’s on you to get what you need. The good news is that useful feedback is available. Sometimes you just need to work to get it from your manager, peers, customers, suppliers, mentors or others you admire. Let’s look at an example.

Mark was a brilliant strategist, ready with a quick response to almost any question. After graduation from business school, he had worked for one of the world’s leading management consulting firms before taking a strategy role inside a technology services company. His office lights were often the last turned off at night as he pored over data and reports, seeking trends that might affect the company’s plans.

Eager to make an impression and succeed in his first corporate role, Mark worked hard and received lots of positive feedback from executives. It was loud and clear: “Brilliant insight.” “Incredible work.” “Superb analysis.”

The accolades boosted his confidence and he doubled-down on providing more of the same. However, Mark’s colleagues didn’t seem to be as enthusiastic about his ideas and he suspected that they might not rate his performance quite so highly. He was right, there was some less explicit negative feedback in circulation as well: “Doesn’t value the opinions of others.” “Fails to collaborate.” “Doesn’t listen well.”

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

This feedback was hidden in informal channels. How could Mark get at the information he needed to address his weaknesses and achieve his career goals? Here are two tips for mining feedback that might require a little elbow grease.

Use more of the feedback you’re already getting. If he’d been more open or aware, Mark might have seen the warning signs of these negative perceptions in hiding. During one of his presentations, for instance, he found himself defending his position to the point of near argument. His colleagues scattered from the room as soon as the meeting ended, but he never followed up to explore what went wrong. Effectively, he had shut down a feedback opportunity.

People may be dissatisfied with the amount of feedback they’re receiving from their managers, but the first step to getting the feedback you need is actually to look inward. Mark wasn’t truly open to hearing criticism from his colleagues.

When we get critical feedback, we find it difficult to accept and then change accordingly. Columbia University neuroscientist Kevin Ochsner has found that people only apply the feedback they are given 30% of the time. What happens to the other 70%? Perhaps people ignore it because it doesn’t fit their self-image or they discount the giver’s view. Or, if they are deeply affected by criticism, they may fail to register negative feedback as a form of self-protection. When someone tells us they are going to give us feedback, we tend to feel threatened — it’s “the cortisol equivalent of hearing footsteps in the dark.”

When delivering feedback, take a lesson from the medical field. Researchers have learned that because of this agitated mental state and other causes, somewhere between 40-80% of medical information given to patients is forgotten immediately and half of what is remembered is incorrect. To improve the likelihood that patients will remember and apply critical information, researchers advise three actions:

Give specific, detailed instructions, avoiding general guidance

Place the content in categories, not lists

Support instructions with written or visual materials

Managers can easily use these techniques to help make feedback easier to absorb, especially during performance discussions.

On the receiving end, you can counteract the natural tendency to disregard or reject criticism by accepting it enthusiastically whenever it’s offered. (Like Mark, you should also be on the lookout for opportunities to seek feedback before it’s offered.) Take notes and listen. After the session, see if you can summarize the feedback and divide it into categories to help with retention. Send a note back to the person thanking them and asking them to confirm the accuracy of what you heard. “Does that cover the key points we discussed? Did I miss anything important?” The mere act of taking notes and following up will help you access more of the feedback at your disposal. It also sends a clear message that you are open to receiving more. By categorizing and summarizing feedback, you can better manage it and identify the nuggets that are most critical to your development.

Ask for a perfect person comparison. Although everyone struggles with receiving negative feedback (or maybe because we do), it is equally difficult for people to deliver it. To increase the odds of getting the tough feedback you need, one of the most important things you can do is to make the person giving the feedback feel comfortable by showing that you are ready to hear what they have to say. One way of doing this is to actively seek out feedback.

Here’s how Mark handled this in real life. Sensing that he wasn’t fitting in, he talked to a colleague who also had a tendency to work late and seemed well respected in the company. The simple question he asked was, “If the perfect person was doing this job perfectly, what do you suppose they’d be doing differently than I am doing now?”

Note how this question takes the focus away from Mark, allowing his colleague to offer his opinions and suggestions without getting personal. The feedback started out in a general fashion, but Mark showed genuine interest and asked follow-up questions. Eventually his colleague got to the heart of the problem: “In this culture,” he said, “getting buy-in on your ideas is more important than the idea itself. I think the perfect person would spend more time socializing ideas with others before making a final pitch. That would also show a commitment to collaboration.”

This was exactly what Mark needed to hear: get out and spend time with others gaining buy-in to demonstrate a willingness to collaborate. He could do something with that feedback and he did, to great success.

Like mining for surface diamonds in a public park, feedback is often waiting for us if we’re willing to put in a little effort. Taking a more disciplined approach to documenting and organizing the feedback you receive will increase the likelihood of acting on it. And if you’re struggling to extract feedback that’s hiding in the shadows, a few simple questions about how the perfect person would handle things differently can help reveal the truth. For better or worse, getting the feedback we need is ultimately our own responsibility. Smart managers don’t wait for it to fall in their laps — they start digging.

August 13, 2015

Create a “Mastermind Group” to Help Your Career

Getting to the top of your field is a challenge, but it’s easier with the support of a strong peer network. A group of trusted colleagues – often known as a mastermind group – can provide honest feedback, help you refine your ideas, and share insights and leads. They can also inspire you with their successes and support you when you face setbacks. Most of us have some helpful professional contacts, but if you want to be part of a community of people focused on helping one another, you’ll likely need to take action to create it.

In my new book, Stand Out, I profile Kare Anderson, an Emmy-winning former journalist who has started two mastermind groups that have been running continuously for over 20 years. Few endeavors these days can boast such longevity, and Anderson says the impact on her personal and professional life has been profound: “You look back on notes you’ve taken, and it’s a way of realizing how much we’ve evolved,” she says.

Here’s how she structured her groups to be a positive force in their members’ lives for more than two decades.

Identify your ideal group makeup. Start by making a list of the people you’d most like to have in the group. Depending on your preferences, it can be a mix of people from different professions (which gives you access to cross-industry insights), or folks in the same industry (who can trade knowledge and experiences). In the latter case, it’s important not to invite direct competitors into the group, to ensure members feel comfortable speaking freely. Whatever you decide on, says Anderson, “Extreme diversity within that framework will make it much more valuable, and you’re going to grow more.”

Choose members wisely. Don’t rush into offering a group membership to someone you haven’t fully vetted – “firing” someone once they’re a member can be extremely awkward. It’s fine to target people you don’t know well as possible members, but go slow and get to know them as individuals before issuing an official invitation. Invite them out for coffee or lunch to see them in different situations. Finally, host an informal gathering of several potential members to see what the social dynamics are like. If one person dominates the conversation or creates a contentious atmosphere, perhaps he’s not the best fit. Depending on how the group is structured, the founder may have exclusive say on who joins, or – as in Anderson’s case – once someone signs on, they may get an equal vote on future members.

Set ground rules. It’s important for members to know exactly what they’re getting into. Stating the group’s goals and values up front will enable potential candidates to make an informed decision about whether they’d like to participate. After all, you want the group to be a commitment they’re making for the long term. Anderson’s groups have three key rules: confidentiality, no referral fees if members send each other new business (to avoid making the relationship transactional), and if you make a commitment to another member, you keep it. Group members strive to be on the lookout for ideas and opportunities for their colleagues. “You ask yourself, ‘Am I giving as much as the others are?’” Anderson says. “It sets a standard.” It’s not a quid pro quo, but there’s an expectation that members will contribute.

Other groups may choose to emphasize different ground rules. For example, some may not need to focus on confidentiality if the topics discussed aren’t personal, or referral fees may be encouraged as a part of the group’s operating model. The key is to provide clarity around the purposes you’d like the group to serve (emotional support, business leads, sharing best practices, joint revenue opportunities, etc.).

Develop a structure. Anderson’s groups meet monthly – not often enough to become a burden on members’ time, but enough to keep up with developments in each other’s lives. “When you’re meeting monthly and you continue to do so, you know so much, you talk in shorthand,” she says. “Together, we can bounce ideas more clearly off each other because we know each other so well and give candid feedback.” Each meeting has a specific structure. The group connects via Skype and members speak in the same order each month, mentioning something they need and any help they can offer to others. The other members chime in if they can assist (“You’ve said you need a new accountant, and I know a great one,” or “You need advice about speaking to an insurance company, and I’m very familiar with the industry”). But when something important comes up, like a new job opportunity or a family upheaval, the group is flexible enough to abandon the typical structure and spend the entire call supporting the member in need by listening, offering advice, and sharing resources.

Anderson has benefited professionally from the group in many ways, from learning about new technologies that improve her business to staying abreast of industry trends. It’s also put dollars into her pocket. When she was being considered as a keynote speaker for a conference and had little experience in the industry, the conference organizer was willing to take a chance on hiring her – purely on the basis of two people from her group vouching for her. She believes the biggest benefit of the group, however, has been the personal growth that’s come from cultivating deep, long-term professional relationships. “It’s scalable, not in terms of more [group members], but in the ways we know to help each other. There’s a record of witnessing each other’s lives,” she says. “It’s made me a better person because of the mutuality at the center of it.”

The public conversation around networking is often about the quick hits: how to shake more hands and grab more business cards. But creating a longer-running mastermind group, whether you want it to last a few years or a lifetime, is a testament to the value of depth over breadth. In a fast-moving world, having people in your life who have watched you grow and progress can be a powerful touchstone, with lasting results.

Google’s Alphabet Move Is Reorganizing 101

The announcement that Google would be reorganized into a holding company named Alphabet has already been interpreted in multiple, often conflicting, ways. Joseph Bower, a strategy professor at Harvard Business School, offers up the simplest interpretation possible: The company’s leaders are doing exactly what executives have done, under similar circumstances, since the 1920s. In other words, it’s Management 101. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

HBR: As a student of corporate strategy, how do you interpret the move to create Alphabet out of Google and its assorted businesses?

Bower: It’s a simple, classic move. At a certain point, companies recognize that they’re in multiple businesses, and that they will be better managed if they organize into business divisions, essentially. Alfred Chandler wrote about this back in the 1960s and the 1970s; DuPont was one of the earliest examples he studied.

It’s a very sensible thing to do.

So will Alphabet be a conglomerate?

We don’t know yet whether it will be a conglomerate or a multi-divisional corporation. Brin and Page and the new CEO could adopt a holding-company strategy: something like Berkshire Hathaway or Loews, whose businesses are not really connected to each other. Warren Buffett doesn’t move talent from one company to another.

Or they could behave more like GE and choose to become a classic corporation, where top management allocates resources — cash and talent – among the different companies and supports a strong corporate culture.

Which direction makes more sense, from your point of view?

Either could work, and I don’t think they know yet which is a better bet, so it’s just as well that they’ve left it open. If it turns out that the people who are good at search are also good at making driver-less cars, then maybe it should be a traditional corporation. That would allow them to treat Google as a cash cow – pull cash out of that and into the more future-oriented businesses.

But you could make just as good an argument on the other side. If one business is capital intensive and others are not…if one business model is throwing off a lot of cash today and another will take years to pay off…they need to be managed very differently.

How will this change affect Google’s very talented and independent workforce, in the near term?

That’s a great question — and my answer relates to what I just said about different business models needing different management systems. If what it takes to operate the businesses and make them successful are fundamentally similar, then it will be helpful to have a unifying corporate culture so that knowledge and learning get shared. But if they are really different, then any attempts at corporate synergy will simply frustrate people. My guess is that in businesses that depend on truly great creative talent, there are fewer economies of scale or scope than one might think.

Take Harvard University. We have great centers of bio-genetic science in several different schools. Would the institution be better –would they be better? — if they were made to work together? I suspect not.

Is it unusual that the founders are still deeply involved at this inflection point?

No, I don’t think so. More and more, we’re seeing that founders of successful businesses like to stick around. Gordon Moore and Andy Grove were at Intel for decades. And for all the talk about hyper-fast change, a lot of successful companies tend to have very slow turnover at the top. Jeffrey Immelt is only the thirteenth CEO of GE, I believe.

Do you think this move was in part a response to pressure from Wall Street?

I don’t think it has anything to do with Wall Street. Google has two classes of stock, so the founders can afford to ignore pressure from activist investors. Basically, they can whatever they want to.

These are smart people. They’re doing what the business needs them to do.

What to Do When Satisfied B2B Customers Refuse to Recommend You

In an ideal B2B world, your happy customers would spread the news about your great products, generating all the well-known benefits of word of mouth. But your customers may not want their competitors to hear about you.

If your product or service has become your customer’s secret sauce – putting them in a position to outperform in the marketplace — then spreading the word may appear to risk diluting the customer’s competitive advantage.

That’s why you might get strange looks if you ask the customer’s managers for referrals. They might even refuse outright, as happened recently to an enterprise-software company that I work with.

But word of mouth is an important ally in your marketing efforts. It can help you overcome skeptical prospects and increase customers’ preference for your products more quickly and effectively than either advertising or PR. It costs very little to generate, yet it reinforces customers’ commitment and strengthens their relationship with your brand. What’s more, customers acquired through referrals are more profitable and stay longer than those acquired in other ways.

So when satisfied customers refuse to provide references, try these avenues:

Explain the product’s network value. Many B2B products become more useful when most players in the industry adopt them. Take price-optimization software: Until the majority of companies in an industry use it, the industry cannot price intelligently as a whole. A competitor using manual methods might fail to pick up on subtle cues, easily detected by optimization software, suggesting that gradual price increases would be appropriate. In such a scenario, the competitor might inadvertently launch a bruising price war. Make the case to your customers that providing references will hasten industrywide adoption and increase the product’s value for everyone.

Extol reputation benefits. In every industry, some companies enjoy alpha status because of their strong reputations. Alpha status has many benefits: risk-averse customers will seek out the company’s products; employees flock to work for it; and vendors and shareholders give it more leeway in downturns or crises. One way to earn alpha status within an industry is to become an opinion leader, by influencing the industry’s business models, standards used, technologies, and customer-management methods. When asking for a reference, marketers should emphasize these benefits. Help the customer realize that providing useful referrals will burnish its reputation among peers and constituents and bring tangible benefits.

Point out the perils of remaining a lone wolf. An ecosystem of users, tinkerers, and enthusiasts is helpful to companies seeking to troubleshoot, customize, or even understand complex products. If others within the industry use the same product, user groups, online communities, and customer conferences can make these tasks less cumbersome and resource-intensive. With a larger customer base, you, as the vendor, also have greater motivation (and resources) to provide education, services, and product improvement. You can let it be understood that without a large customer base, you might even reduce your investments in the product.

Offer incentives for providing a reference. If all else fails, B2B marketers that are keen to penetrate a particular industry must buy their customers’ references. Depending on the product and economic value involved, various forms of incentives may be given for a reference: subsidized maintenance or training programs, exclusive features or services, or the promise of first access to the product’s next generation. But beware: Once incentives are offered, customers may become less enthusiastic about performing such actions voluntarily in the future. Offering incentives may also change the economics of reference-based marketing programs by making them pricey, reducing their power and effectiveness.

Don’t let the imperative to understand and sympathize with your customers’ point of view stop you from seeing the harm caused by their unwillingness to spread the word about your products. If customers view generating word of mouth in narrow terms, help them see more broadly. If they see providing referrals as a potential loss, help them reframe this favor to you as a gain for themselves. Show them that in today’s business environment, network effects can benefit every company, even those that cherish their independence and special advantages.

Giving Feedback When You’re Conflict Averse

“Conflict avoiders are generally people who value harmony in the workplace,” writes Amy Gallo in the HBR Guide to Managing Conflict at Work. ”When they sense a disagreement brewing, they will often try to placate the other person or change the topic. These aren’t passive behaviors, but active things they do to prevent conflict from becoming an issue.”

So what do you do if you naturally avoid conflict but a big part of your job is giving difficult performance feedback? When you’re worried about ruffling feathers, how do you provide your direct reports with the input they need to learn and improve?

The first step is acknowledging your conflict aversion. Have you found yourself saying any of the following statements in the last six months?

“I believe in giving people chances and investing in them so I want to give this more time.”

“I don’t want to crush the person when he is already working so hard. I need him to stay motivated.”

“My style tends to be more collegial. I prefer to roll up my sleeves and help out if someone is having trouble.”

“The person is so difficult, aggressive, and defensive. I hate that kind of conflict.”

If so, you may be actively avoiding confrontation. Which doesn’t mean that you have to change your core values–maintaining relationship harmony is an important part of any job. But you will need to reframe the way you think about tough feedback. Rather than seeing it as a potential violation of your values, consider how it could be an opportunity to put your values to work. Here are some tips for doing that:

Don’t delay and make things worse. Although deferring a difficult conversation can result in temporary relief, things simmer. Problems get worse. Projects get off track or fail. We end up putting the business—or our working relationships–at risk and potentially having to take more dramatic action than if we had acted earlier. When you find yourself hesitating to share feedback, ask yourself: What is the business context? Does it require a swift decision? Be careful that in the effort to spare the feelings of one individual, you don’t end up hurting the morale of many others.

Further Reading

Giving Effective Feedback (20-Minute Manager Series)

Communication Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Or perhaps you see signs of trouble but are holding back because you don’t fully trust your instincts. Consider what would boost your confidence in making the call about when to give tough performance feedback. What additional information could you collect? What objectives are at risk? Ultimately, what are the costs if you don’t give this feedback now?

Be clear and open. The good news is that your agreeable demeanor makes it next to impossible for you to deliver feedback in a belittling way. So don’t worry about being clear and direct. To keep your critique from feeling personal, start by sharing the broader business context for why the feedback matters now. Reassure the person that you know their intentions were probably good, but that you do have some observations to share about the effect of their actions. Provide your take on what is happening for this person today and what needs to be different. Describe the impact they are having now and what impact they need to have. Allow time for them to digest the information and ask for their thoughts. Does this resonate? What is their perspective on the issue? What are they struggling with?

But don’t stop there. Make sure that you get concrete about the changes you need to see (in both skills and actions) and articulate clear time frames. Offer examples of how they might have handled the situation more effectively. For instance, you might say, “With the monthly reports, I need to see you be more proactive and show you are getting in front of things. Or, “When you bring an issue to my attention, also bring a recommendation to show that you’ve dug into it.”

In our attempt to avoid conflict, soft-pedaling or sugar-coating might feel better in the moment, but if we don’t say what needs to be said, real change will never happen.

Get comfortable with uncomfortable emotions. Feedback can potentially lead to disagreement, hurt feelings, or defensiveness. Prepare for tough conversations in advance by playing out possible scenarios so that you’re ready for whatever may occur.

If you or the other person starts to get defensive or emotional, acknowledge the tension and offer a break. “I understand how difficult this must be. What do you need at this point in the conversation?” Or, “This is challenging for both of us. I’d like to take a break and catch up later today.” When the going gets tough, make sure you don’t back-pedal, change your message in an attempt to diffuse the situation, or start talking too much to fill silences or plow through the conversation. You want to give the person adequate time to digest what you are saying.

If they offer new information, take it into consideration. If your assessment and suggested course of action remain intact, stay on message. On the other hand, if the new information could significantly shift your view, it’s best to step back and reassess. You can say, “I appreciate your sharing this information. I was not aware of it. I’d like a chance to look into it. Let’s get together in a few days after I’ve had a chance to learn more.”

Follow up. Even if the first conversation goes well, you can always offer to be available for further discussion to ensure a fair resolution. Loop back to ensure an optimal outcome has been achieved, both in preserving the message and the relationship.

Being an effective leader requires some level of stepping out of your comfort zone and a commitment to continually improving your communication skills. Your preference for harmony can be an asset to the organization and to your team in the right circumstances—but it can also backfire if you’re not careful. You can still cultivate positive relationships by encouraging and cheering others on. But to ensure that your people are performing at their best, you also have to know when it’s time to give tough feedback. Stay true to yourself by delivering it in a clear, respectful way. You may be surprised to find that on a high-functioning team where feedback is shared honestly, conflict is minimal.

The Gig Economy Is Real If You Know Where to Look

A number of reports in recent weeks have stressed that employment effects of the so-called gig economy—contract workers on software platforms such as Uber and AirBnB—have been overstated. At minimum, these reports indicate, any increase in gig economy employment hasn’t shown up in the aggregate statistics—at least not yet anyway.

But my analysis tells a different story, showing that the impacts can in fact be seen if you look more deeply at the data and in the right places.

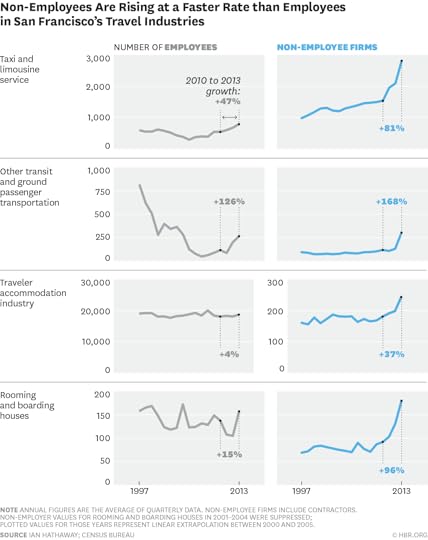

By examining key industrial segments (rides and rooms) and geographies (early-adopters in San Francisco), I found a substantial rise in collaborative economy “gigs” between 2009 (when uptake began) and 2013 (the latest year data are available). I also found that more gigs haven’t been accompanied by fewer workers on payroll, at least so far.

The data show that despite the attention the contractor status of these workers has received—including by leading Presidential hopefuls—software platform companies are not the first to take this approach. In fact, the San Francisco taxi and limousine industry shows a clear shift of activity from workers on employer payrolls to those of independent contractors for at least a decade before the first ride was hailed using Uber.

The gig economy doesn’t show up in aggregate data for several reasons. It’s relatively new, early uptake has been concentrated in some cities and not others, and most of the data we have on self-employment only counts someone’s “primary job.”

To see if other analysts, who have looked at broad national aggregates, have missed something in the details, I analyzed just the passenger ground transit (e.g. Uber) and traveler lodging (e.g. AirBnB) industries. Since the data are current through 2013, I only looked at San Francisco—where uptake started the earliest, so results can reasonably be seen in that timeframe. This is a critical point, because even in this leading city, services such as UberX didn’t really take off until 2013.

Like the others, I also analyzed publicly available data produced by the Census Bureau on so-called “nonemployer firms,” or businesses that earn at least $1,000 per year in gross receipts but don’t employ anyone. The substantial majority of these “firms”—86% across all industries to be precise, 91% for those industries studied here—are self-employed, unincorporated sole-proprietors.

To benchmark the non-employer firms, I matched Census Bureau data on employment in San Francisco for the same industries.

Three major findings stand out. First, there are clear growth surges in nonemployer firms in each of the two industries associated with passenger ground transit between 2010 (when Uber launched in San Francisco) and 2013, and in the two industries linked with traveler accommodation from 2009 (the year AirBnB opened). These increases amount to thousands of workers earning a living in some way (either supplemental or in full) because of these platforms. Because of the way income activity is reported, this is almost certainly an undercount—representing a lower bound on activity. This suggests an increase in the number of contractors employed in these industries.

Second, we do not see declines in payroll employment in the same industries during this period. Instead, we actually see increases in all four—particularly in the passenger ground transit sectors.

Caution is needed when interpreting these figures. Nonetheless, such strong employment growth contradicts the idea that Uber drivers are pushing incumbent firms out of business. Instead, it lends credence to the story behind Uber’s founding, and the experience of San Franciscans at the time (myself included)—Uber and other peer-to-peer ride services like Lyft were meeting unmet consumer demand in a city with a massive shortage of taxi services.

Finally, these figures suggest that the trend toward contractors over payrolled employees in the taxi and limousine industry was going on in San Francisco long before Uber’s arrival. If the employment security of drivers is truly the issue, perhaps the debate has to expand beyond concern over platforms like Uber.

Though more work needs to be done, this simple case study shows that gig economy employment is showing up in the official statistics when one knows where to look. Previous reports that analyzed a wider range of data at higher levels of industry and geographic aggregation, though also important, miss these finer points.

Data for 2014, which will be released one year from now, will likely show an acceleration of these trends in San Francisco, and an extension of them to other cities. Future analysis will need to look more closely at the net effects of the gig economy on employment—and on wages—as well as the impact that a broader and potentially harder-to-measure range of platform services, such as Etsy and Thumbtack, are having on the economy and the workforce.

It’s important to remember that these platforms are very new and that good data usually comes with a time lag. We can’t yet analyze the true impact of these platforms. But, as this case study has shown, the effects might be bigger than has been previously thought.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers