Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1264

August 11, 2015

Clinton’s Proposals on Stock Buybacks Don’t Go Far Enough

HBR STAFF

The debate over how to reverse ever-increasing income inequality has moved front and center in the Democratic presidential campaign. In speeches on July 13 and July 24, front-runner Hillary Clinton first outlined and then elaborated upon her policy agenda for combating what she calls “quarterly capitalism.” In emphasizing the need for value-creating business investment in an economy in which value-extracting financial interests are driving corporate resource-allocation decisions, the Clinton economic reform package is novel and refreshing for a Democratic presidential contender.

In its superficial focus on time horizons and information disclosure, however, Clinton’s policy agenda may exacerbate the very problem that it seeks to alleviate. For example, one of her key proposals is for shares to be held well beyond the current minimum period of one year before the profits from their sale are taxed as a capital gain. But that will not in any way deter hedge-fund activists from demanding that companies do stock buybacks so that they can time their stock sales to take advantage of short-term, buyback-induced, stock-price boosts.

In some cases, activists may decide to hold a company’s stock for more than a year to reap full advantage of a prolonged run-up in stock prices induced by persistent buyback activity. A prime example is Carl Icahn, who began to accumulate his multibillion-dollar stake in Apple in August 2013. Icahn has regularly demanded that Apple do more buybacks to pump up its stock price and thus far has held some of his Apple shares for two years in anticipation of a bonanza. To date Apple has acceded to Icahn’s demands. In April, its board increased the amount that could be used for buybacks by the end of March 2017 — to $140 billion from the $90 billion it had authorized in 2014. It has spent almost $90 billion on buybacks and almost $33 billion on dividends from 2012 through the third quarter of 2015.

Icahn wants to see Apple’s stock price, which is now at $116, rise as high as $240, at which point the reward for his patience, and Apple’s commitment to doing hundreds of billions of dollars in buybacks, would be over $5 billion. Yet Icahn has never invested in Apple’s value-creating capabilities that increase innovation and productivity. He is a value extractor: someone who buys and sells a company’s already issued shares and then forces the company to take actions that provide a short-term boost to its stock price regardless of the impact on its capabilities. Under Clinton’s proposed scheme, Icahn’s eventual gains from selling Apple stock would get the preferential capital-gains tax treatment that is supposed to incentivize value creation. By failing to identify the types of activity in which a shareholder is engaged, Clinton’s revamped capital-gains tax scheme could very well increase the after-tax profits of the nation’s biggest value-extractors.

Indeed, under Clinton’s proposals, top executives would continue to line their pockets by using their companies’ open-market repurchases of their shares to augment their realized gains from exercising stock options and the vesting of stock awards. Since almost all of this stock-based income is already taxed at the personal income rates, Clinton’s proposed capital-gains tax reforms would have absolutely no impact on the “short-termism” of top executives.

Clinton advocates full implementation of the executive-pay disclosure directives of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. Yet it must be recognized that in the 832 pages of Dodd-Frank the term “stock market” is never mentioned, much less “stock repurchases,” “stock buybacks,” “stock awards,” or “restricted stock.” On page 529, there is one parenthetic reference to “stock options.” Put simply, for combating value extraction at the expense of value creation, both Dodd-Frank and Hillary Clinton’s proposals miss the mark.

Citing my Harvard Business Review article, “Profits Without Prosperity,” Clinton claims that her policy agenda will “take a hard look at stock buybacks.” She explains:

Investors and regulators need more information about these transactions. Capital markets work best when information is promptly and widely available to all. Other advanced economies like the United Kingdom and Hong Kong require companies to disclose stock buybacks within one day, but here in the United States you can go an entire quarter without disclosing. So let’s change that.

Full disclosure is a good idea. Under Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 10b-18, which was established during the Reagan administration, companies need not disclose the actual amount of buybacks that they do on any given day either at the time they are executed or after the fact. If the SEC is going to continue to permit open-market repurchases by companies — which I think should be banned — it should at least require each company to reveal immediately, on a daily basis, how much it has done on any given day so that the SEC and the public can assess whether stock-price manipulation is going on. It would then also be transparent if executives and other insiders have timed the sales of their own personal holdings of the companies’ shares (including those acquired from exercising stock options or the vesting of stock awards) to take advantage of price boosts from buyback activity.

That said, the safe harbor provision of Rule 10b-18 that currently enables a company to repurchase on any one day up to 25% of its stock’s average daily trading volume over the previous four weeks should be eliminated. This “limit” is another license to manipulate the stock market for the benefit of company executives and hedge-fund managers.

Creating more efficient capital markets does not do much good if the purpose of those capital markets is, as is currently the case, value extraction, not value creation. If Clinton wants to attack short-termism, she should call for the repeal of SEC Rule 10b-18.

But perhaps the most elegant solution is one Clinton has not yet advocated: simply banning corporations from making open-market repurchases of their shares.

Looking inside the daily operations of a business enterprise, we find employees in the hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands who go to work each day to develop and utilize the company’s productive capabilities. They — and not parasitic hedge-fund managers like Carl Icahn — are the value creators. A company that truly cares about creating value will share the gains with its employees, and their standards of living will then rise.

That is how any nation gets a rising and prosperous middle class. I would encourage Hillary Clinton — and all other presidential candidates — to mobilize American workers by mounting a political campaign to bring back the middle class. Clinton wants to raise the minimum wage, enforce overtime rules, strengthen collective bargaining rights, and give tax credits to companies that train new employees and share profits with their workers. She should also press for a ban on stock buybacks.

When First Movers Are Rewarded, and When They’re Not

When it comes to launching new products, should your company be a pioneer or a follower? This question presents a constant dilemma for some businesses. Product pioneers face more risk, but can reap big rewards when an innovation proves successful. Second-movers, on the other hand, are assured more reliable returns. But the longer they wait, the higher the chance that the largest spoils have already gone to other, more daring players. So which timing strategy is better?

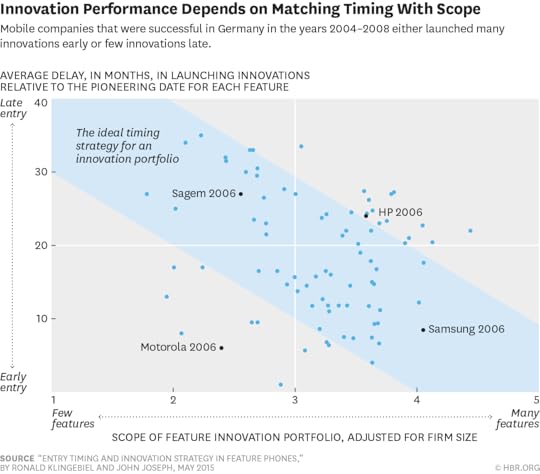

Research I conducted together with John Joseph of Duke University shows that both approaches can be successful — what matters most is not simply timing but whether a company tailors its innovation strategy to whichever approach it adopts. We studied the German mobile-handset market during the feature-phone era of 2004-2008 — a dynamic period in which competition was about equipping devices with new functions such as photography.

When reviewing pioneers and followers in this large European market, we found that both approaches could produce good returns, but that innovation management at successful pioneer firms looked very different from successful follower firms in four key ways:

Scope

A key difference between successful pioneers and followers was how many innovations they launched. Because followers miss out on blockbuster returns, they cannot afford to fail as often as pioneers. Instead, they must weed out projects carefully and launch only a narrow scope of innovations they are (relatively) sure will succeed.

In 2006, HP — then still active in the mobile space – acted as a follower, but failed to focus its innovation portfolio. It introduced a broad set of mobile phone features that had already been on the market—including several audio, video, and camera features. Only some of these proved popular and led to much weaker return on investment than they created for the pioneering firms, making it difficult for HP to compensate for unsuccessful features.

Contrast that with Sagem, a vendor of French origins, which was also about two years behind the pioneers in terms of launching new features, but did so more selectively. It focused on two innovations, video calling and multi-frequency compatibility. This narrow focus on innovative features earned it roughly double the return on innovation investment (as measured by the ratio of R&D expenditure to new-product revenues) of HP and other late-movers that launched a more indiscriminate slate of innovations.

Samsung, a classic pioneer in the handset market, also had a successful year in 2006. While many of the roughly dozen features it brought to market flopped, the Korean tech giant was first to market with storage capacity of up to 4GB and new multimedia features, which allowed it to reap a big chunk of the rewards before other firms joined. These hits more than compensated for its unsuccessful feature innovations. Because of this dynamic, the overall return on innovation investment for broad first-movers such as Samsung is comparable to that of narrow followers such as Sagem.

Pioneers who come to market with a narrow scope of innovations take on enormous risk. Motorola in 2006, for example, concentrated on bringing to market HSDPA-enabled phones. Although technologically advanced, this did not prove profitable and Motorola had launched little else to compensate.

The graphic below plots these companies against others in the mobile industry during the feature phone era and illustrates that firms that match their timing strategy to their innovation portfolio fare better than those who don’t.

Diligence

Another key difference between pioneers and followers was the amount of due diligence they undertook before going to market. Asking too many questions can slow you down. Pioneers understand that even the most sophisticated business cases cannot help them remove the uncertainty of moving first. So instead of trying to get it right, they focus on moving fast, so that if an innovation happens to be a blockbuster, they are the ones to cash in on it.

By contrast, late-movers’ returns on innovation are smaller; there are no blockbusters that can compensate for failures. Successful late-movers spend more time reviewing business cases and attempting to validate assumptions. They proceed only when they are sure. Consequently, their emphasis is on getting it right rather than moving fast.

Commitment

It might seem paradoxical but pioneers appeared more committed to innovations than followers. Because pioneers must get to market quickly, they do not interfere with development. Innovation teams have planning security and the confidence that the firm will do whatever it takes to bring a novel feature to market, undeterred by potential naysayers. Even if such critics turn out to be right most of the time, it is the few times they are wrong that matter for early-movers’ innovation success.

Followers are more cautious. They have the luxury of watching the performance of features launched by early movers, so they can adjust their commitment to innovations as they go along. Successful late-movers ax more projects during development than first-movers. That way the features they do end up launching are likely successes.

Incentives

Traditional incentive systems tend to reward innovation managers if they successfully complete a product launch. This works well for pioneers, for whom speed is important. But it can wreak havoc for second-movers who gain an edge by avoiding the mistakes of early movers. Managers whose salaries are tied to project completion have a powerful motive to decide against raising concerns about a troubled project. Followers thus need to tailor their incentive systems so that it encourages managers to pursue experimentation more than completion, and removes penalties for project cancellation.

Our research of the vibrant mobile-phone industry of the last decade shows that there is no obvious advantage to moving first —second-movers can be just as successful. What matters most is understanding that the two entry-timing positions differ in terms of uncertainty and size of returns. You need to build an innovation strategy to match your timing preference.

PepsiCo’s Chief Design Officer on Creating an Organization Where Design Can Thrive

Mauro Porcini is PepsiCo’s Chief Design Officer—the first to hold the position—where he oversees design-led innovation across all the company’s brands under CEO Indra Nooyi. Below is an edited version of my conversation with Porcini on a variety of topics, from prototyping to the essential qualities of a great design organization.

How do you define design?

Design can mean many different things. At PepsiCo, we’re leveraging design to create meaningful and relevant brand experiences for our customers any time they interact with our portfolio of products. Our work covers each brand’s visual identity, from the product itself all the way to the marketing and merchandising activities that bring a brand to life across different platforms—music, sports, fashion, and so forth.

This applies not only to the current portfolio of products, but also to PepsiCo’s future portfolio. That’s where our work is really about innovation. I strongly believe that design and innovation are exactly the same thing. Design is more than the aesthetics and artifacts associated with products; it’s a strategic function that focuses on what people want and need and dream of, then crafts experiences across the full brand ecosystem that are meaningful and relevant for customers.

What does this look like on a day-to-day basis, at PepsiCo or elsewhere?

Design in this context relies on the prototyping process, which can create a lot of value inside organizations because it aligns the full organization around one idea. For instance, if I say “knife,” you are going to visualize a kind of knife. I’m going to visualize another knife, and if there were other people in the room, they would visualize many different kinds of knives. But if I design a knife right now, I align everybody around that knife. Let’s say that in the room there is a marketer who tells me the brand is not visible enough. There is an ergonomist who tells me the handle is not comfortable enough. There is a scientist who tells me the blade is not sharp enough. These are not mistakes. They’re not failures in the process. They’re how prototyping surfaces issues that don’t emerge in the abstract. That’s the power of design and prototyping.

When you put a prototype, something that is new and that nobody has ever seen before, in front of people, they get excited, right? There is the sparkle in the eye. I’ve seen it so many times in so many meetings. People talk and talk about things until somebody arrives with an object, a prototype, and then everybody gets excited. That’s how you unlock resources. You unlock sponsorship engagement. That’s extremely powerful and lets you move really fast. It’s how you speed up your innovation process and make the outcome more relevant to customers.

What do you need in order to make design thrive inside an organization?

Certain circumstances are necessary for design to thrive in enterprises. First of all, you need to bring in the right kind of design leaders. That’s where many organizations make mistakes.

If design is really about deeply understanding people and then strategizing around that, we need design leaders with broad skills. Corporate executives often don’t understand that there are different kinds of design: There is brand design. There is industrial design. There is interior design. There is UX and experience design. And there is innovation in strategy. So, you need a leader who can manage all the different phases of design in a very smart way—someone with a holistic vision.

Second, you need the right sponsorship from the top. The new design function and the new culture need to be protected by the CEO or by somebody at the executive level. Because any entity, any organization, tends to reject new culture.

Once you have that, then you need endorsements from a variety of different entities. It could be from other designers outside your organization. It could be from design magazines. It could be through awards. But you need that kind of external endorsement to validate for those inside the organization that you’re moving in the right direction.

Then you need to identify quick wins: those projects where you can show the value of design very quickly inside the organization. On the basis of this early success, you start to build processes that can enable the new culture and approach to be integrated inside the organization.

The process is really an evolution. I see it as five often-overlapping phases. The first one is denial: the organization sees no need for a new approach or new culture. But somebody with influence and power inside the organization—often it’s the CEO or somebody at executive level—understands that actually there is a need, so they hire a design leader who tries to introduce a new culture.

Then comes the second phase: hidden rejection. There may be acceptance at the top that the organization needs to embrace a new approach, but the full organization isn’t there yet. The design leader is moving forward in alignment with leadership and thinks that things are working well, but in reality they are not. In this phase, it’s easy to fail, and it’s easy for the company to reject the new approach.

The third phase is what I call the occasional leap of faith. As the design leader, you find a co-conspirator inside the organization who understands the value of what you’re doing. He may or may not understand deeply what design is about, but he understands that there is value there and decides to build something with you, to bet on you. That’s when you start to get your quick wins. The quick wins are so important because they exponentially build understanding about the value of design.

The fourth one is what I like to call the quest for confidence. This is when the company understands that there is value in this new design culture and tries to integrate it throughout the organization. The problem is that when you try to do something different, there is always inefficiency and risk. This is especially true if you do design in innovation: There is risk not just in a process but in the market, in the brand and product you’re going to launch. That’s when you need to build confidence in the organization.

But at the very base of innovation and entrepreneurship is risk. Methodologies like Six Sigma are all about reducing risk, but they are not effective for innovation because innovation by definition is risky. Design, on the other hand, can build confidence inside the organization in a variety of ways. It comes down to building innovation know-how within the organization, and gaining input and buy-in from across the organization and from your customer through the prototyping process. The more you prototype, the more you build confidence in the organization, and the more you know that what you’re doing is the right thing. This quest for confidence is extremely important because so many corporations today are paralyzed by their fear of making mistakes or failing.

The last phase is what I like to call holistic awareness, when everybody understands that the new culture, in this case design, makes sense for the organization. This is when design is not about designers anymore. It becomes universal, and it prompts everybody to modify their own approach to work—whether it’s marketing, manufacturing, or any other function—to embrace it.

What does a design team look like at PepsiCo?

You need the design function—senior leaders with teams under them—embedded inside the business organization. Or integrated into it, I should say, because we don’t want design to report to another function. We want design to be a peer of marketing and to drive innovation.

At the center, we have been developing the key pillars of the design functions. We have a very senior leader running industrial design, another one running brand design, another one running innovation and strategy. And we are building digital as well. They are the ones who are nurturing the design capability.

Our hiring process is tough because we’re not just looking for good designers. When you’re creating a new design organization, a new culture, you need to hire change agents and people who understand how to change the culture of design. This makes things extremely difficult because you have many, many designers who may be amazing at what they do, but they have no idea how to explain what they are doing to a business organization. Those kinds of designers are a luxury we can’t afford in this phase of the organization’s evolution. If you have designers who can’t influence change, you get that familiar situation with designers whining that the business organization doesn’t understand them and the business organizations saying the design community has no clue what we’re trying to do.

You need the shared language, the structure, and most of all the right people to create a true design culture. I’m really against those design or innovation firms that claim they can come in and teach you design thinking. The result of their expensive workshops is people who are not design experts will start to think that now they get design and can do it by themselves. That’s a disaster because you do need skills and experience.

How do you convince others that investing in design is worth it?

For many, many years I’ve been asked in my corporate life to define the return on investment of design. The objective variables obviously are at project level and then at brand level—top-line and bottom-line growth. That’s a no-brainer.

Then there are subjective variables that we really want to take into consideration. One is consumer engagement. You can measure it in a formal way or you can measure it in the way consumers talk about your products, which is easy to do today via social media. Another variable is brand equity, meaning the impact on the brand. It’s customer engagement, the way your customers interact with you, the way they talk to you.

The truth is, once you embed design across your organization and people start to experience it, they stop asking you what its ROI is because they start to see the impact across all those variables.

Can you talk about a key business outcome from your time at PepsiCo so far?

When I joined the company a little less than three years ago, I was able to build a very strong partnership with our business organization and with R&D. We’ve been leveraging design to understand what our customers need and want from fountains, coolers, and vending machines. Then we’ve been crafting—prototyping, really—to create the ideal portfolio as fast as possible and take it to market.

The Spire family of equipment, launched about one year ago, is the first output of Pepsi’s design-thinking approach. Spire is a series of fountains and vending machines that let you customize your drink: you choose the beverage and add flavors. It’s been well received by the market, and it’s helped us as a design organization to show what design is about. We launched a new series of products this year and there is much more in the pipeline, but Spire is probably the project I love the most.

What makes Spire significant is that it’s such a change for the industry. Usually it’s external partners and suppliers that do a lot of the work on equipment, but.with Spire, we said, let’s reset and let’s try to understand what makes up the portfolio of products we really want to offer. We rethought the architecture of the existing machines, but we also reimagined how we might build beverage, and eventually food, experiences in restaurants in the future.

We actually projected further out, to the fountain and the vending machine of 20 years from now. We wanted to understand where we could go and then step back pragmatically to deliver innovation in the short term, the middle term, and then the longer term as well.

You need to prove the point of design through activity, actions, and projects—it’s not just top-line and bottom-line returns. That will come. But it could be speed to market. It could be efficiency in the process. It could be employee engagement.

Are there any final thoughts you want to leave our readers with?

As designers—industrial designers, product designers, innovation designers—we are trained to understand all the different worlds of brand and business, R&D and technology, and especially people. We become experts of everything and experts of nothing. What we’re really good at is speaking the languages of all the different worlds, then connecting those worlds to our design tools and to our ability to prototype and visualize ideas. When done well, design becomes a cultural interpreter and facilitator across the entire organization.

Two Ways to Better Care for Patients with Dementia

In September 2014, President Obama announced the $100 million federal Brain Initiative to revolutionize our understanding of the human mind and uncover new ways to treat, prevent, and cure brain disorders. In time, the unique public-private sector initiative will hopefully yield new ways to manage Alzheimer’s, dementia, and other related conditions.

The health care system has had little to offer the 5.2 million Americans who suffer from behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Nineteen percent of adults between 75 and 84 years of age and nearly half of those over 85 suffer from dementia. As physicians (an internist and a psychiatrist), we have found that patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s are profoundly mismanaged.

Over the past four years, there have been several efforts to improve the care or patients and families with dementia.

At the CareMore Health System, the health care delivery system where we work, we have piloted our own brain health program to address the needs of patients with signs and symptoms of dementia by identifying them early and working with their family members to improve their care.

With funding support from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, the University of California, Los Angeles, launched the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program in late 2012 to help patients and their families with the complex medical, behavioral, and social needs of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

Both programs point to several lessons that we believe can help other health care organizations respond to the onslaught of patients suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Consider the total impact. When first diagnosed with dementia, patients and their families are given diagnoses but little else in terms of guidance and support. The mismanagement of these patients results in costly but unhelpful diagnostic workups, countless avoidable emergency-room visits and hospitalizations, and most worrisome, profound feelings of loneliness, isolation, and hopelessness as patients and their families clumsily progress through a disjointed health care system.

To address this problem, CareMore built a multidisciplinary team that takes a broad view of the issues confronted by patients with dementia, including preventing falls, providing a safe environment, ensuring that medicines are being safely taken, legal challenges, and nutrition. Patients and their families were given access to a program to educate them about common issues faced by dementia patients and what to expect as the disease worsens. Every patient in the program has a care plan tailored to his or her need and stage.

Our pilot effort in brain health involved 42 patients. In the first year, patients had 10 total ER visits and 71% of patients suffered a fall. In the second year, there were no hospitalizations, only 14% reported any kind of falls, and just one had to go to the ER due to injuries suffered in fall. CareMore is in the process of scaling the pilot to a systemwide initiative for more than 100,000 patients.

Based on preliminary results, leaders of the UCLA program expect it will reduce and shorten hospital stays, reduce the number of emergency room visits, and improve patients’ and caregivers’ health. They estimate the program, which has more than 1,000 Medicare and Medicaid participants, will save approximately $6.9 million during its three-year demonstration phase.

Focus on caregiver involvement. Physicians and nurse practitioners often focus their energies on the patients in front of them. Forgotten are the adult children and other caregivers to whom responsibility falls. In dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, outcomes are very closely linked with caregiver engagement and involvement.

In addition to educating caregivers, the CareMore program follows up with them to reinforce the need for their involvement. In our pilot, nearly two-thirds of caregivers assumed an active role in monitoring the medication prescribed for patients, and 94% of caregivers stated that they felt the program improved their understanding of dementia and improved their ability to help the afflicted patients.

The UCLA program is taking a similar approach. It provides 24/7, 365-day-a-year access to a nurse or physician for caregivers who need assistance and advice.

Over time, scientific breakthroughs will enable us to identify and treat patients with dementia and other forms cognitive decline. We are closely monitoring these developments, including several phase III clinical studies of new therapies and other studies of diagnostic modalities to more rapidly identify patients with Alzheimer’s disease. As these therapies become available, we will integrate them into our care model.

But in the meantime, our health care system and others must strive to develop and scale better systems of care that address the medical, social, and educational needs of patients with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia and their families. If our early experience is any indication, these systems will deliver better clinical outcomes and, just as important, better support for patients and their families.

How to Give Tough Feedback That Helps People Grow

Over the years, I’ve asked hundreds of executive students what skills they believe are essential for leaders. “The ability to give tough feedback” comes up frequently. But what exactly is “tough feedback”? The phrase connotes bad news, like when you have to tell a team member that they’ve screwed up on something important. Tough also signifies the way we think we need to be when giving negative feedback: firm, resolute, and unyielding.

But “tough” also points to the discomfort some of us experience when giving negative feedback, and to the challenge of doing so in a way that motivates change instead of making the other person feel defensive. Managers fall into a number of common traps. We might be angry at an employee and use the feedback conversation to blow off steam rather than to coach. Or we may delay giving needed feedback because we anticipate that the employee will become argumentative and refuse to accept responsibility. We might try surrounding negative feedback with positive feedback, like a bitter-tasting pill in a spoonful of honey. But this approach is misguided, because we don’t want the negative feedback to slip by unnoticed in the honey. Instead, it’s essential to create conditions in which the receiver can take in feedback, reflect on it, and learn from it.

To get a feel for what this looks like in practice, I juxtapose two feedback conversations that occurred following a workplace conflict. MJ Paulitz, a physical therapist in the Pacific Northwest, was treating a hospital patient one day when a fellow staff member paged her. Following procedure, she excused herself and stepped out of the treatment room to respond to the page. The colleague who sent it didn’t answer her phone when MJ called, nor had she left a message describing the situation that warranted the page. This happened two more times during the same treatment session. The third time she left her patient to respond to the page, MJ lost her cool and left an angry voicemail message for her colleague. Upset upon hearing the message, the staff member reported it to their supervisor as abusive.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

MJ’s first feedback session took place in her supervisor’s office. She recalls, “When I went into his office, he had already decided that I was the person at fault, he had all the information he needed, and he wasn’t interested in hearing my side of the story. He did not address the three times she pulled me out of patient care. He did not acknowledge that that might have been the fuse that set me off.” Her supervisor referred MJ to the human resources department for corrective action. She left seething with a sense of injustice.

MJ describes the subsequent feedback conversation with human resources as transformative. “The woman in HR could see that I had a lot of just-under-the-surface feelings, and she acknowledged them. The way she did it was genius: she eased into it. She didn’t make me go first. Instead, she said, ‘I can only imagine what you’re feeling right now. Here you are in my office, in corrective action. If it were me, I might be feeling angry, frustrated, embarrassed… Are any of these true for you?’ That made a huge difference.”

With trust established, MJ was ready to take responsibility for her behavior and commit to changing it. Next the HR person said, “Now let’s talk about how you reacted to those feelings in the moment.” She created a space that opened up a genuine dialogue.

The subsequent conversation created powerful learning that has stuck with MJ to this day. “Oftentimes when we’re feeling a strong emotion, we go down what the HR person called a “cowpath,” because it’s well worn, very narrow, and always leads to the same place. Let’s say you’re angry. What do you do? You blow up. It’s okay that you feel those things; it’s just not okay to blow up. She asked me to think about what I could do to get on a different path.”

“The feedback from the HR person helped me learn to find the space between what I’m feeling and the next thing that slides out of my mouth. She gave me the opportunity to grow internally. What made it work was establishing a safe space, trust, and rapport, and then getting down to ‘you need to change’ — rather than starting with ‘you need to change,’ which is what my supervisor did. I did need to change; that was the whole point of the corrective action. But she couldn’t start there, because I would have become defensive, shut down and not taken responsibility. I still to this day think that my co-worker should have been reprimanded. But I also own my part in it. I see that I went down that cowpath, and I know that I won’t do it a second time.”

The difference in the two feedback sessions illustrated above boils down to coaching, which deepens self-awareness and catalyzes growth, versus reprimanding, which sparks self-protection and avoidance of responsibility. To summarize, powerful, high-impact feedback conversations share the following elements:

An intention to help the employee grow, rather than to show him he was wrong. The feedback should increase, not drain, the employee’s motivation and resources for change. When preparing for a feedback conversation as a manager, reflect on what you hope to achieve and on what impact you’d like to have on the employee, perhaps by doing a short meditation just before the meeting.

Openness on the part of the feedback giver, which is essential to creating a high-quality connection that facilitates change. If you start off feeling uncomfortable and self-protective, your employee will match that energy, and you’ll each leave the conversation frustrated with the other person.

Inviting the employee into the problem-solving process. You can ask questions such as: What ideas do you have? What are you taking away from this conversation? What steps will you take, by when, and how will I know?

Giving developmental feedback that sparks growth is a critical challenge to master, because it can make the difference between an employee who contributes powerfully and positively to the organization and one who feels diminished by the organization and contributes far less. A single conversation can switch an employee on — or shut her down. A true developmental leader sees the raw material for brilliance in every employee and creates the conditions to let it shine, even when the challenge is tough.

August 10, 2015

6 Ways to Turn Managers into Coaches Again

The role of the manager is currently undergoing a transformation. Historically, managers embraced the role of coach and mentor. Through informal conversations during the commute to work, over a coffee break, or while enjoying a burger after hours, managers passed along crucial information and knowledge about the organization’s culture. Even more formal conversations, like one-on-one meetings and small group gatherings, transferred insight and understanding to employees. This invaluable information wasn’t found in textbooks, from a class, or over an app, but given from someone with years — decades even — of experience.

But today, tighter budgets, flatter organizations, a heavy workload, and too many direct reports often leave managers without the time — and sometimes without the skills — to shoulder the responsibility of being coach and mentor. And yet, this function remains critical to the long-term health and productivity of the organization.

This erosion in the role of the manager has not gone unnoticed. As part of a recent research project into how top executives view training and development programs, executives overwhelmingly said the most urgent problem they face is igniting their managers to coach employees. What’s more, it’s also the challenge where executives said they are most desperate to find and deploy effective solutions.

In response, my team has compiled six practical tips to help managers slip back into the role of coach as effortlessly and efficiently as possible. These tips include:

Use regular one-on-one check-ins. Regular check-ins, as opposed to waiting for the annual performance review, allow you to work collaboratively with your direct reports to offer regular insight, knowledge, guidance, and suggestions to help them solve pressing problems, and to help them stay on track for their professional development goals. This is one of the most powerful tools that you can use to elevate coaching. Some managers we spoke with make it a point to schedule regular phone conversations or in-person meetings on a monthly — and sometimes even weekly — basis.

Encourage more peer-to-peer coaching. Peer-to-peer coaching offers some of the richest, most valuable learning in an organization. An easy way to incorporate more of this type of learning is to use your regular staff meeting as a collaborative problem solving session. This builds cohesion among your team, and inspires them to think creatively about how to solve pressing organizational challenges. It’s also an easy way for you to coach multiple people in one setting at one time, thus maximizing your time and efficiency.

Create mentoring partnerships. “Some of the richest mentoring I have experienced is through ‘reverse mentoring’ where a younger generation employee partners with a more senior employee and they agree to share lessons learned with one another,” says Michael Arena, Chief Talent Officer at GM, so consider pairing-up team members from different demographics. Those in the older demographics likely possess critical institutional knowledge and have collected a vast amount of life experience that would be beneficial to the younger generation, while those in the younger generation likely know all about the latest and greatest technology and how to find important bits of information rapidly, which they can pass onto their mentoring partner.

Tap into the potential coach within everyone. Hidden within many individuals is a fountain of information and knowledge waiting to be shared with the broader team. You can encourage your own team members to become coaches and trainers by allowing them to hold their own mini-seminars on an important topic or skill. Or if your organization offers software and applications, like its own private YouTube Channel or an intranet, encourage them to create and share their own learning content, stories, and tips for where to access the best learning activities.

Don Jones, former Vice President, Learning, Natixis Global Asset Management shared this example in a recent interview:

Employees are becoming “content developers” for our learning organization. Imagine a top sales person in the field giving his pitch on a certain product. He then uploads the content and others in the organization can share their thoughts and comments through Salesforce Chatter, or other online discussion groups. This is an example of the power of free-flowing knowledge that can be exchanged in an organization. It energizes, engages, and encourages learning. Plus, these videos and comments become material to create content to show our new sales hires during sales training.

Support daily learning and development activities. We’ve heard from a number of Chief Learning Officers who say employees regularly claim they don’t engage in learning activities because they don’t believe their managers would support them. It’s up to you to change this perception by creating an environment where it’s not only acceptable, but encouraged to use office time to engage in learning activities. Suggest that they digest small bites of content when it fits into their schedules during the day, or look for creative and engaging ways that you can bring learning and development into daily activities for your people.

Seek formal training. It seems obvious, but if you want your staff to engage in ongoing learning activities, then you’re going to have to model that behavior yourself. Consider seeking out formal training to enhance and improve your hard and soft skills, whether it’s one class, a certification program, or completing a more formal executive education or leadership training curriculum. In today’s modern world, you have numerous opportunities to engage higher education be it through an online, distance, local on campus, or a hybrid program. Pursing a more formal training program is one of the wisest investments you can make in your development.

Managers have an enormous impact on an organization’s ability to retain and attract top talent, and they remain the preferred, go-to source for passing on knowledge, skills, and insights to others in an organization.

The good news is that great coaches aren’t born; they’re made through dedication, commitment, and practice. By taking the initiative and proactively working to become a better coach, you will elevate not only your own performance, but that of your team, and by extension, your organization.

How to Keep Support for Your Project from Evaporating

Even years later, I still consider it my biggest professional failure: a company-wide employee training program that I’d developed and put through several rounds of vetting was shot down at the last minute. It was a painful surprise, and it changed the way I’ve sought support for new initiatives ever since.

As hospitals increasingly migrate their medical records from paper files to digital media, their employees face the challenge of making the information readily accessible to providers while adequately protecting patients’ privacy. At my hospital, I was a senior vice president with a long track record of establishing successful programs, and I had oversight responsibility for my hospital’s IT and Health Information departments.

To make sure our 23,000+ employees were up to date on the industry rules, policies, and procedures they were legally required to be familiar with, my department heads and I created a robust training program. We went well beyond the minimum that the law required, creating a curriculum rooted in industry best practices. We could have just printed out a thick informational packet to give to each employee, but we knew the training program had a much greater chance of being effective. And we gave the program a catchy name to top it off.

From the outset, I understood the training program would require the support of the entire senior management team, as they would have to direct their departments to complete the training and document that they had done so. As our multidisciplinary team developed the curriculum, I provided regular updates to my colleagues and asked for their input throughout the process. With each vetting, they indicated their support of the initiative. So when the pushback finally happened, I never saw it coming.

Timing is everything. When the final vote on the training program arrived, another vice president, who had been supportive of the program, had just come from a meeting where his pet project was shot down. He was livid about his defeat and was not in the mood to approve my program. In fact, he made such an angry speech that a few others in the room weren’t up to arguing with him. My initiative was tabled.

In hindsight, I had made two mistakes. In the highly regulated world of health care, training programs are introduced continuously with little fanfare. I gave my program a catchy name to make what was, frankly, a tedious chore a little more inviting to the many people who would have to complete it. Giving mine a sexy name made it sound like a full-blown program that would consume significant resources, raising its profile more than was warranted.

The second mistake was assuming that when my colleagues smiled and nodded every time I presented the details, that meant they would continue their support no matter what was happening outside the conference room. My angry colleague being so riled up was not the time to remind him that the training met a critical need and was something we had to pursue.

Of course, angry outburst aside, the work still needed to be done. So, I waited a few weeks and went to visit my disappointed colleague once he’d had a chance to cool off. I reminded him that it was important for this program to go forward, and I asked him what it would take to get him behind the effort. We negotiated a few points and came up with a plan we could both support. I then asked him to present our changes at the next senior management meeting so it would be clear to everyone in the room that he was back on board. That time, the vote carried.

Nearly a decade later, I’m actually grateful to him for teaching me a valuable lesson. I had been so sure of the strength of my professional relationships that I’d just assumed everyone would remain consistent and true to their word, regardless of what it would cost them in an unforeseeable situation such as the one we found ourselves in that day.

As a result of this experience, when I’m developing a project now, I ask for and record votes at every vetting and make those records available for review. That way, if there is ever a disagreement about the status of one of my projects, there is a clear record of everyone’s position, making it more difficult for people to change their stance in the heat of the moment. I also log undecided votes when people haven’t made up their minds yet, but I’ve found that people usually form opinions about new projects pretty quickly. If I’d had documentation of everyone’s support for the training program, their positions would have been clear, so there would have been no need for me to go up against our angry colleague.

Second, I learned to wait until something is actually approved to give it an eye-catching name and brand it as a standalone program. When the training was finally approved a few weeks later, we gave it a new name — the result of a contest among the employees who would have to take it — which truly helped people understand what needed to be done and how to do it. But naming a program too early runs the risk of creating a sense among your teammates, who may be promoting their own initiatives, that there are winners and losers.

Most of us work in environments where there are many initiatives competing for limited resources of budgets, time, and attention. Sobered by my surprising upset, I’ve taken pains to formalize the vetting process and not rely on friendships and collegial alliances. In fact, the higher the stakes, the more formal the process I use. Not all industries may need a process as formal as mine, but it’s important to figure out the best way to get projects approved where you work.

Here’s an example of how I use this process to facilitate budget negotiations. To prioritize the requests for expensive IT initiatives whose demands far exceeded the resources available each year, I created a multi-disciplinary senior level steering committee to evaluate various initiatives and sort them by order of strategic and operational importance. Votes were all documented. When I entered into budget negotiations with the other SVPs, I was armed with a record of who supported each initiative. The relevant SVPs either sat on the steering committee or were represented. In this way, we avoided the seriously unpleasant task of making the case for each initiative in the heat of the budget battle. The work of the steering committee allowed a full vetting in a neutral setting — which is exactly what the budget room is not.

I’m happy to report that since adopting these two practices, I’ve never endured the same kind of defeat, even when the stakes have been high. Maybe that experience wasn’t such a failure after all.

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the September 2015 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the September issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“If we’re out of paper, just run some off on the 3-D printer.”

Pat Bynres

Dave Carpenter

“…and this is our meeting simulation tank, where associates train for the rigors of long-term sitting.”

Teresa Burns Parkhurst

“That’s one of my early pieces.”

Martin Bucella

And congratulations to our September caption contest winner, Karen Stokdyk of Essex Junction, Vermont. Here’s the winning caption:

“That’s just one opinion. Personally, I love the new logo!”

Cartoonist: Tim Mellish

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by September 1.

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

Entrepreneurs, Economic Growth, and the Enlightenment

Diderot’s Encyclopedie, best known as an eighteenth-century repository of Enlightenment principles, might also serve as an interesting lens into what makes economies grow.

The Encylcopedie was a project spearheaded by Denis Diderot, published in 28 volumes between 1751 and 1772. It aimed to gather all the knowledge in the world, and, with 71,818 articles and more than 3,000 illustrations, it was a valiant effort. While the Encyclopedie (or, more properly, Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers [Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts]) is justly famous for containing essays by the likes of Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Voltaire, and promoting values like secularism, reason, and toleration, it’s the sciences et métiers – the mechanical arts piece – that interests us here.

In a new paper that will be published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, two economists – Mara Squicciarini from the University of Leuven and Nico Voigtlander from UCLA’s Anderson School of Management – argue, “Subscriber density to the Encyclopedie is an important predictor of city growth after the onset of industrialization in any given city in mid-18th century France.” That is, if you had a lot of smarty pants interested in the mechanical arts in your city in the late 18th century (as revealed by their propensity to subscribe to the Encyclopedie), you were much more likely to grow faster later on. Those early adopters of technology – let’s call them entrepreneurs, or maybe even founders – helped drive overall economic vitality. Other measures like literacy rates, by contrast, did not predict future growth.

Why? The authors hypothesize that these early adopters used their newly acquired knowledge to build technologically based businesses that drove regional prosperity. If that’s true, then “upper tail knowledge,” as the authors put it —knowledge of new technology, from chemistry to engine building — in the hands of highly talented people who could do something with it may be a major factor in creating prosperity, one distinct from a society’s overall level of education.

This argument does have precedent. Enrico Moretti and Dan Wilson, two economists, have written about the influence of star scientists on highly productive tech industries, and Dan Stengler, the head of research at the entrepreneurially focused Kauffman Foundation, has argued for the disproportionate impact of a small number of “gazelle” startups on economic growth. (For the classic economics paper on the role of technology on growth, see Paul Romer’s 1990 article “Endogenous Technological Growth” or read David Warsh’s terrific book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations.)

Joel Mokyr, a doyen of economic history writing in Science (where I first saw mention of the QJE paper), draws out one contemporary lesson from the example of the Encyclopedie. Mokyr writes, “For economies that are at the technological frontier, investing in the education of the best and the brightest may be as important as raising the mean of the entire distribution. For the rest of the world, which imitates and adopts rather than invents, investing in mass education is still the best strategy for economic growth.” For advanced economies, like that of the United States, “upper-tail skills – even if confined to a small elite – are crucial, fostering growth via the innovation and diffusion of modern technology.” For us today, “upper-tail” education isn’t a PhD in English lit (not that there’s anything wrong with that), it’s the kind of knowledge you need to create Tesla.

But “elite” is a tricky word, so let’s be careful to define our terms. In this case, the elite are not the rich or the one percent or the stars of stage and screen. In the historical context, it was those with the interest in and capacity to use the scientific and mechanical ideas in the Encyclopedie. It was they who set the groundwork for growth in the coming industrial era. While they may also have been rich, that wasn’t the point.

What Squicciarini and Voigtlander’s paper is capturing isn’t the importance of social elites per se (in fact, it would probably be better to jettison that word altogether for the confusion it can create); it’s the importance of scientific and technical knowledge, and its effective application. But the ability to understand and use those ideas isn’t confined to just the top of the socioeconomic ladder. Talent is spread evenly throughout the population. People who could make important breakthroughs in applying scientific and technical insight are as likely to be born into families at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum as among those at the upper end.

Which is a problem for Americans in particular, because the United States does a terrible job of educating smart but poor kids.

Consider a paper presented at the Summer Session of the National Bureau of Economic Research by Raj Chetty, Bloomberg Professor of Economics at Harvard University, “Innovation Policy and the Lifecycle of Inventors.” (The presentation was a preliminary version of research that Chetty has done with other researchers at Harvard, the Office of Tax Analysis, and the LSE; the slides are no longer available on the web, but the researchers will release a new version in a few weeks.) In it, Chetty and colleagues explore the relationship between the propensity to file a patent and socioeconomic status by linking millions of individual tax records to around 1.5 million patent filings, which allows them to “characterize the lives of inventors.” (No one is suggesting that filing a patent is the equivalent of being Elon Musk, but it’s at least directional.)

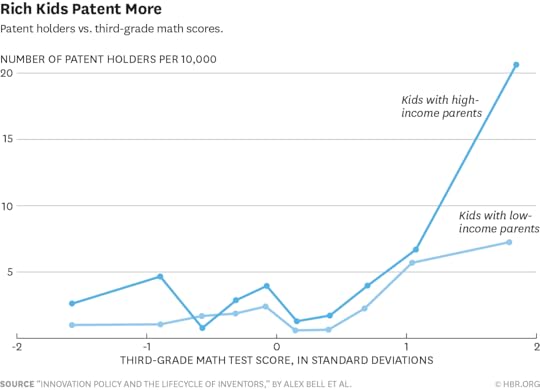

Perhaps unsurprisingly, children of low-income parents are far less likely to file patents than are children of the well-to-do. But what surprised me was the size of the gap that the researchers found, especially among the kids who were best at math. Third graders who do poorly on the standardized tests and those who do average to slightly above average pretty much patent at about the same rate, rich or poor. But among those third graders who scored two standard deviations above average on their math scores – that is, eight and nine year olds who were pretty darn good at math – those with high income parents were three to four times more likely to file a patent later in life than were those with low income parents (around 22.5 patents filed per 10,000 people versus around 6 per 10,000).

This innovation gap represents not just another instance of inequality of opportunity and outcome, as many have rightly noted, but also an insane amount of social loss. By not properly educating those people – rich or poor – who have the greatest propensity to understand and use technical knowledge of the kind similar to that which helped spur and spread industrialization in 19th century France, we may be slowing our future economic growth even more than we think. How many Tesla’s are we smothering by not focusing on young kids with a potential talent for STEM?

It also worth noting that poor kids who are good at math patent more than rich ones who aren’t. As a consequence, it can sometimes look like we’re in a meritocracy, since we can point to disadvantaged kids who make good. But that analysis ignores the counterfactual: that poor kid should really have patented so much more.

If we do want future growth, we should be focusing on young, smart kids and giving them access to whatever kind of knowledge and support they need. Make them subscribers, as it were, to our own Encyclopedie — which might include technical knowledge but also the right mindset, call it what you will: “maker,” “hacker,” “practical and creative.”

Of course, innovation policy and education have to focus on more than just smart people. Even if those with upper tail knowledge have disproportionate influence on productivity tech, it’s not the whole story. Productivity of new tech is “unlocked” over time during adoption process. (See this HBR post by Jim Bessen, for instance, on the diffusion of technological know-how). We can’t exactly abandon the educational goals that support diffusion (and, incidentally, a properly functioning democratic republic).

But it does imply that our current system is simply not going to help foster tomorrow’s explosive growth. If you take seriously the economic contributions of great entrepreneurs (and the evidence from the Encyclopedie and elsewhere suggests we have to), you have to grapple with the toll inequality takes on so many peoples’ ability to become one.

August 7, 2015

How to Break Up with an Innovation Project

Breaking up isn’t easy — especially if you are a leader “breaking up with” an innovation project that one of your teams still believes in passionately. It is a critical part of the innovation journey however, and done well can produce a positive outcome across the board.

Consider a conversation that might start like this:

“We need to talk,” she says.

There’s only one way this conversation ends, you think, but you paste a smile on your face and reply, “Sure. What’s up?”

“We seem to be stuck,” she says. “When we started it all seemed so perfect. But now every time we talk it is about the problems we face.”

“We just need more time,” you say. “We will get through this and come out the other side stronger. Remember why we started this in the first place?”

“Absolutely,” she says. “The story. Our story. It gave me chills the first time I heard it. I believed. And I still believed after you told me to wait and have faith six months ago. And three months ago. But we have to come to grips with reality. That vision we both believed in is an illusion. The data doesn’t lie. Think of the other things we both could be doing instead. We had some great times, and I don’t regret them at all.”

“But,” she finishes with authority, “it is time.”

And the project breakup process has begun.

Investors in startups have it comparatively easy. Breakup happens by default because the cash coffers run dry. Sure, investors need to have tough conversations about the need to change directions or make personnel changes, but there is no ambiguity when the end comes.

In contrast, rhythms inside organizations mean that ideas that are sanctioned tend to take on lives of their own. Further, strong penalties for failing to deliver against commitments make it in everyone’s interest to keep pushing ahead.

Any time you commission an innovative project, failing to achieve your commercial objectives is a real possibility. The more innovative the idea, the more it by definition rests on assumptions that may or may not pan out. The tools and techniques developed over the past decade around managing those assumptions, coupled with dramatic decreases in the cost of developing and testing ideas means you can learn much more efficiently than before, but that doesn’t change the fact that a good idea in theory might not be a good idea in reality. Customers rarely do what you expect them to. A promised benefit that worked in the lab might not work at any kind of commercial scale. A beautiful economic model in Excel might turn out to be an ugly one in reality.

Not every idea is destined for greatness. When it is clear an idea isn’t going to make the cut, perpetuating it can sap your organization’s innovation capacity and energy.

It can be hard for teams working on ideas to view the situation objectively. In the fog of innovation, data are rarely crystal clear. Every parent knows the biases that set in around things you played a part in conceiving. And it is far too easy for decision-makers to get seduced by the passion a team has for an idea.

The nameless executive above did an artful job of breaking up with the innovation project they were overseeing. Notice three key lines:

“The data doesn’t lie.” It is far easier to breakup with an idea if you’ve been clear from the beginning about what success looks like, and have brought rigor to the process of experimenting around key unknowns. You never know for sure when you experiment, but you always should have HOPE – a hypothesis, objective, prediction, and execution plan to measure and test the prediction. That gives you the best chance of having an honest conversation about your idea.

“Think of the other things we both could be doing instead.” Opportunity costs are real. Executives should never look at an idea in isolation, because there will always be an argument for pushing on. Making clear that there are other more attractive opportunities both for corporate resources and the team itself makes the breakup more palatable.

“We had some great times, and I don’t regret them at all.” Every time you innovate, Rita Gunther McGrath reminds us, two good things can happen. First, you can deliver some kind of commercial or operational benefit. Alternatively you can learn something that enables a future commercial or operational benefit. That learning could be about a market or a technology, but it also could be about how you do the work of innovating inside your organization. Maybe a team learned how to execute a particular type of experiment, or found a vendor that is particularly useful (or one that should be avoided). Capture that learning and recognize that something truly useful has happened.

Breaking up is never easy, but just like human relationships, when done constructively the net result is almost always positive. And it is an essential step, so that time and attention can be redirected toward new ideas. Don’t let the fear of confrontation stop these potentially positive outcomes.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers