Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1267

August 4, 2015

When It’s OK to Ignore Feedback

TOM EVERSLEY

If we never listen to feedback, we’ll never improve. That’s certainly true, but in a world where everyone has an opinion (whether it’s about Hillary Clinton’s wardrobe or Ellen Pao’s leadership style), who should you actually listen to?

Over the past several months, I’ve appeared on more than 130 podcasts to promote my new book, Stand Out. Most of the queries are the same, but when someone recently asked me about the role of feedback in my life — a question I’d never received before — my own answer surprised me. “I try not to listen to feedback,” I told him. “Most of it is either useless or destructive.”

Of course I can point to useful pieces of feedback I’ve received over the years: my friend Eric the TV producer counseling me on how to present myself onscreen, or my former client Andrea suggesting a better way to do email introductions.

As my business has grown and my visibility has increased, I have received a steady stream of feedback. And for the sake of my own sanity — and accomplishing the goals that are most important to me — I’ve generally decided to tune out other people’s suggestions and advice. Here are the strategies I use to determine when to ignore feedback.

When it’s vague. In my first job out of graduate school, I was a political reporter. I had a reasonably good feel for language, but I was in my early twenties and had never been a professional journalist before. In short, I’m sure there were myriad ways for me to improve. But it was incredibly hard to figure out how because my editor, frustrated with the shortcomings of my prose, would simply snap at me to “Make it different!” Since she was my boss, it was my job to try to decode her meaning, so I’d try, often fruitlessly, to create different story openings and see which irritated her least.

As I’ve advanced in my professional life, I’ve found that many people who don’t have authority over me also want to share maddeningly non-specific feedback (“I didn’t think it was as strong as it could have been” or “There was just something off”). If they can’t tell you exactly what the issue is, it’s not your job to figure it out (unless they sign your paycheck).

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

When it’s exactly what you’re going for. Just the other day, I got an email from a disgruntled reader who was unsubscribing from my email list. “I enjoy your work,” she began. But she found my emails “overly familiar,” which I’m guessing is a critique of my decision to open them with a greeting of “Hi there!” and occasionally include pictures of Beyonce. Indeed, those aren’t choices that most business authors would make—which is exactly why I’m making them. In the marketing and branding world, it’s standard-issue advice that “If you’re trying to appeal to everyone, you’ll appeal to no one.” But the harder-to-swallow corollary is that in appealing to some people a great deal, you’re going to alienate others. Clearly this woman wasn’t a fan of my approach, and that’s perfectly OK. It simply means she’s not my target audience, and her unsubscribing—which would be easy to take as a rebuke or rejection—can instead be taken as feedback that my goal of being a different kind of business thinker is working.

When it’s only one person’s opinion. It’s easy to fixate on critiques; one friend I knew used to quote verbatim, at least every other week, a negative review of her work dating back more than a decade. But the opinion of one person, no matter how influential that person is, isn’t always reliable. You should be wary of such advice until you get confirmation (or not) from other people. It’s quite possible that their feedback isn’t about you at all; it could be the result of them having a bad day, or their own personal bias (you’re an abstract expressionist and they only like figurative painters), or the fact that you remind them of their mother-in-law. One person’s opinion isn’t a trend.

When it’s ad hominem. Especially on the Internet, where people don’t have to look you in the eye when they render their verdict, it’s easy for people to be snarky or snide in their commentary. It isn’t that your facts are wrong, it’s that you’re stupid. It isn’t that they disagree with your strategy, it’s that you’re ugly. (One Twitter user recently sniped about my haircut.) Is it possible there’s a grain of solid critique inside their schoolyard rhetoric? Maybe. But—per the policy of only listening to feedback when it comes from more than one person—you can safely ignore the overt haters. If they have a point, you’ll hear it eventually from someone else, in a form that’s more professional, respectful, and less damaging to your psyche.

When it comes from a dubious source. Here’s the most important reason why you should ask for feedback from people you trust. Everyone may have an opinion, but that doesn’t mean it’s useful. Just as, in the Internet era, it’s easy to drown in information overload if you don’t meter your intake, the same is true of feedback. The best way to sort the wheat from the chaff is to decide in advance who you respect, and only choose to listen to those people. If your friend who’s a speaking coach tells you how you can improve your stage presence, you may want to listen; a random audience member, not so much.

Feedback is a tool that can help us learn and grow. But it’s become a bit of a religion in the corporate world to believe that it’s always a good thing. Feedback from the right people—who are informed, helpful, and have your best interests at heart—is invaluable. But when it comes to everyone else, the best thing we can do is learn to ignore them.

August 3, 2015

Does Stating What Your Company Stands for Affect Your Bottom Line?

Babo Schokker

Respect, integrity, communication, and excellence: these were Enron’s self-professed values, before accounting fraud brought down the firm. So you’d be justified in thinking that the values listed on corporate websites don’t really matter.

But researchers at INSEAD and IMD business school weren’t so sure. Yes, talk is cheap, and public proclamations aren’t the same thing as living up to one’s values. (The Enron example is included in their paper.) Still, stated values might also represent a firm’s aspirations, the type of company it strives to be. If that’s the case, maybe the values on a company’s website are meaningful after all; perhaps Enron is the exception rather than the rule.

The upshot from the researchers’ paper, published earlier this year: don’t dismiss the corporate values statement. It seems to be linked to financial performance.

The paper, published in the European Management Journal, isn’t the first to look at the values firms list on their websites; a 2013 paper tried something similar but found no correlation with performance. But Charles Galunic of INSEAD and Karsten Jonsen, John Weeks, and Tania Braga of IMD did a few things differently than the earlier researchers. First, they looked not just at which values are listed but at the total number of values each firm includes. Second, they compared firms’ values to the values of their competitors. Finally, they considered how values change, the idea being that firms that don’t shift their values over time may fall behind more agile competitors. They measured all this for the Fortune 100 in 2005, and compared each measure to the firm’s return on assets over the subsequent three years.

They found that the more values a firm lists on its website, the better its financial performance. And the more those values differed from competitors’ values, the better the company performed. These relationships might not be causal, the authors caution, but they offer a plausible reason for the link. “One could argue that espoused values are the calling card to recruit talent and to show good citizenship,” they write. If firms that take recruiting seriously are more likely to post more values, that could help explain the relationship.

Why does listing different values than competitors correlate with performance? The authors argue that this reflects a timeless principle of competitive strategy: differentiating yourself is one classic way to stay profitable.

These results suggest that values do matter, and that when firms state those values publicly, they’re saying something meaningful about who they are. That’s likely no surprise to HBR readers. As James Collins and Jerry Porras wrote in their 1996 classic “Building Your Company’s Vision”:

Core values are the essential and enduring tenets of an organization. A small set of timeless guiding principles, core values require no external justification; they have intrinsic value and importance to those inside the organization. The Walt Disney Company’s core values of imagination and wholesomeness stem not from market requirements but from the founder’s inner belief that imagination and wholesomeness should be nurtured for their own sake.

But the new paper’s third finding contradicts the idea that values should be timeless. Companies that changed their values between 2005 and 2008 had higher return on assets than those that did not. You might argue that this is merely capturing short-term financial performance, and that more stable firms — the Disneys, with their timeless principles — will win out in the end. Maybe. But the paper hints at another explanation.

Companies that changed their values also tended to have more differentiated values, a key part of strategic advantage. So perhaps the lesson isn’t quite that dynamic values beat stable ones. It’s that even timeless values aren’t a substitute for good strategy.

How to Make Your Workplace Safe for Transgender Employees

“I applaud [Caitlin Jenner’s] moxie in stepping out in such a public way. But real courage for a trans person comes in just going to work—at a job—every day. Something Caitlin will likely not have to do,” said Jeremy Wallace, a transgender participant in my leadership training program and author of the memoir Taking the Scenic Route to Manhood. He’s right. The statistics are bleak. Transgender individuals are 40% more likely to attempt suicide and 50% more likely to be unemployed or homeless than the general population. The hard truth is that despite the splashy emergence of Caitlin, formerly Bruce, Jenner, as transgender, most trans people in our society remain largely invisible, rarely seen in large organizational settings, let alone in leadership roles. The “outing” of a major celebrity or sports figure (remember Renée Richards from the 70s?) has, up to now, barely made a dent in the harsh reality most trans people live every day.

Is it possible that things will be different this time? In the wake of Laverne Cox, trans star from the highly-regarded Netflix series, Orange is the New Black, gracing the cover of Time magazine, and the television show Transparent winning a Golden Globe for a searing portrayal of a transgender life, perhaps Caitlin’s big debut will accelerate a major shift in social awareness. Recent polls in the U.S. show that over 70% of Americans believe transgender people should be protected from discrimination in the workplace. Perhaps all of this publicity creates an opening—a moment of opportunity—for the “real” work to get done: making the world a safe place for trans people to live, work, and succeed.

As an executive coach and organizational psychologist who runs leadership training programs for large corporate firms and non-profits, I have rarely seen trans participants in my programs until recently. When I asked Jeremy why that might be true, he had a ready answer: “Trans people are still very unlikely to stand up or stand out in an organization. In fact, they more often try to do the opposite, to remain hidden, below the radar, and in many cases they exit the job world once they’ve chosen to undertake the process of a full transition. Most workplaces are hardly welcoming—and certainly not likely to send a trans individual to leadership training—at least not yet.”

That may be true, I thought, as I pondered Jeremy’s response. Yet here he was—a trans man being groomed to stand on the podium for a nationally recognized social advocacy organization. And he was no longer alone. I’ve recently met three other transgender individuals in my leadership programs, all of them very impressive. The times, as Dylan sings, “they are a changing.” But are we ready? Are we willing to turn, with an open mind—and heart—and not only accept, but work alongside or follow, emerging leaders like Jeremy?

Jeremy is in his mid-forties, a successful executive who manages a number of small business franchises in and around Las Vegas. In fact, his success as a business leader led him to want to give back to the community, so he recently volunteered to be a regional leader for the Human Rights Campaign, which sent him on to Washington DC, and to me, for leadership training. During the four-day leadership institute, we had the opportunity to talk at length about his story.

He told me that as a young girl growing up he always “thought he was a boy.” He did all the things boys did—climbing trees, playing with trucks and cars instead of dolls, and playing ice hockey. As a child and adolescent growing up in the American heartland, it never occurred to “Jennifer” that she could actually become a boy. She just lived—becoming increasingly isolated and depressed—with a seemingly intractable contradiction: “I was a misfit, a boy trapped in an alien body from which I could never escape.” It wasn’t until many years later that Jeremy learned it was even possible to “become the man I always knew that I was.” The decision to transition and the subsequent surgery happened “very fast” over a period of 8 months. As he put it, “Once I knew that it was possible… I wanted to do it!”

That doesn’t mean it was easy. He recalled painful memories of working up the courage to tell his family, then slowly informing his franchisees, who were in some ways more than just employees—they were “like family.” He was amazed to find that, with a few exceptions, most were surprised but ultimately accepting. The first lesson I gleaned from Jeremy was that getting others to understand and accept his transition was made easier by telling people that he was just as much a student of the process as they were. He didn’t expect them to know how to handle it at first, just as he didn’t quite know how to handle it himself. He was changing in appearance (over a period of many months) and finally claiming the male identity he had always felt was real. But deep down he wasn’t changing who he really was. If anything, it was the opposite: he was finally becoming who he had been all along.

Jeremy admits that he has been fortunate. He has an accepting family and was already running a successful business when he made the decision to transition. Unlike many of the transgender people he meets in support groups around the country, he didn’t have to worry about being fired. But he still grappled—and grapples to this day—with fears of being rejected or seen as crazy or unworthy. “In my experience,” he told me, “the real issue for trans people is not so much acceptance by the world, but self-acceptance. For so many years, I lived with a deep-seated feeling that there was ‘something wrong’ with me and even now, looking in the mirror and finally seeing the man that I always knew I should be, I have to work every day to feel safe in my own skin.”

In this sense, Jeremy is not so different from the rest of us. We all have to learn to accept our flaws, our gifts, all of who we are. His journey offers a number of lessons about self-acceptance along with acceptance in the workplace. So I asked him for advice on how to help managers turn what may initially feel foreign or awkward—learning that a trans individual is on their team—into a growth opportunity for everyone. The key, Jeremy pointed out, is fairly simple, but not easy: “Make everyone feel safe.”

Here are some other pieces of advice that Jeremy shared with me for creating an atmosphere of safety and inclusion:

Educate yourself about the issues and the language of gender identity (e.g. gender identity is not the same thing as sexual orientation)

Have a true open door policy so that an employee can approach you about their transition when they’re ready. A few best practices for achieving this?

Put your open door policy in writing

Actually keep your door open (!)

On a regular basis, schedule and communicate open-door hours when any staff member can stop by and see you

Treat every trans person as an individual. Discuss with them how they would like to announce their transition, and how and when they will be presenting their true gender identity full-time

Don’t be afraid to ask questions, make honest mistakes, and admit that you are learning

Maintain a sense of humor. Jeremy shared that when he felt awkward trying to explain his situation to confused employees, he would often use humor to get the ball rolling: “Hey, I’m new to this process myself,” he’d say. “Do you think going from shaving my armpits and legs to shaving my face is easy? If I can get through the nicks and bruises of that, we can all stumble our way through this together!”

Address the bathroom policy before the person “comes out” to co-workers (e.g. make it acceptable for trans people to use the bathroom that conforms to their identity, not just biology, or consider designating all bathrooms as all-gender. You can find more information on bathroom best practices from the U.S. Department of Labor.)

Seek out an expert for diversity training. The burden of education should not be on the trans employee (it can be frustrating to be perceived as a “token” or someone else’s teachable moment)

Take an interest in the transitioning employee but remember that there should be clear boundaries between home and work. As in any professional environment, the primary focus should be on the job and work performance, not the trans employee’s personal situation. The key for managers is to listen and be supportive but refrain from becoming embroiled in the transition process itself.

While this is the advice of one individual and is not meant to be representative of the experience of all transgender leaders, I think it is a good starting place for managers wondering how to create a safe workspace for trans employees. What was most noticeable to me as I reflected on the tips Jeremy shared is how, with the exception of #6 (bathroom norms being one area of unique complexity), all of the other suggestions are best practices for creating a welcoming, safe and empowering environment for all employees, not just those who identify as transgender.

The science of emotional intelligence demonstrates that the human tendency toward fear and judgment of others who are different can be overcome with empathy, deep listening, and a willingness to tap into our common humanity. But in order to get there, managers need to create a space for dialogue about the challenges of “otherness” faced by trans people and by many other employees as well.

The time is ripe for transformation. Not just because of celebrities like Jenner (who deserve praise for raising the public profile of trans individuals), but because leaders like Jeremy are emerging in organizations every day and deserve the opportunity to make their full contributions—for the good of themselves, their teams, and their employers. With humility, humor, and eloquence, LGBTQ leaders are becoming more visible at the water cooler. But beyond increasing visibility, I hope this heralds a new kind of workplace, one where “difference” is not just tolerated but embraced. Now that “the Caitlin is out of the bag” so to speak, perhaps the workplace will finally follow public opinion, becoming a space where human beings in all their endless variety, creativity and talent feel safe, welcomed, heard, and empowered to lead.

I am thankful for the wisdom Jeremy imparted to me about his experience as a transgender leader. But remember one of his most important tips: the burden of education should not fall on the trans individual. Bringing in a diversity expert can help your team operate more inclusively and ultimately become more productive. As we know, organizations tend to perform better when employees can bring their whole selves to work.

Tough Love Performance Reviews, in 10 Minutes

There’s growing evidence that conventional performance reviews are not working. According to a CEB analysis, organizations can only improve employee performance 3% to 5% using standard performance management approaches. Last fall, 53% of human resources professionals in a Society for Human Resource Management study gave a grade between B to C+ when rating how their organization managed performance reviews. Only 2% gave an A to their organization. As a result of findings like these, some companies are doing away with annual performance reviews altogether.

As my company grew, I started seeing the issues with conventional reviews firsthand. Most performance management systems are simply too cumbersome and formal for today’s startup world. Plus, the time reviews require is itself a huge barrier to doing them well. For me, spending one hour with 30 people each quarter, one-on-one, plus all the preparation and documentation required, didn’t seem scalable. And since our employees received immediate feedback on performance issues, I found there wasn’t a lot of new information to share at these check-ins.

At the same time, I felt it was important to do these reviews myself, rather than delegating them to others. As the company founder, I wanted to maintain a direct connection to my team. And I don’t think they wanted me to become more distant, either; many times, employees join smaller organizations because of the founder and her passion and vision. Finding the time to stay close and nurture employee growth was critical, but so was finding a feedback method that worked better.

You and Your Team

Giving and Receiving Feedback

Make delivery–and implementation–more productive.

I run a user experience-led innovation company—which means my profession is making products better, more intuitive, and more profitable—so we approached the performance review issue as a design problem. How could we get maximum impact in minimal time? I looked at different ways to change the process, including how feedback is given, the interview duration, who leads during a performance review, what the end goal is, and how often reviews occur.

When I unraveled these factors, what we now call our “Tough Love Reviews” emerged. A Tough Love Review is simply a 10-minute, one-on-one conversation with each employee to talk through the one thing he is doing exceptionally well and the one thing that he needs to improve to reach that next level. The result is a meaningful conversation that gives employees a choice in how the conversation unfolds, and results in two key takeaways that are memorable and actionable.

Here’s how they work.

First, create a spreadsheet with the following columns:

Column 1: Employee Name

Column 2: Tough—Two or three trigger words or phrases to serve as reminders during the review. Include performance issues, goals missed, interpersonal issues, and/or general quality of work feedback if it needs improvement.

Column 3: Love—Again, focus on two or three key words. Think highlights, goals achieved, great work, recent accomplishments, or accolades from clients or team members.

Think holistically about each person’s contribution to the business: What do you need this person to bring to the table? What does this person uniquely contribute? What is a barrier or simply annoying for the team? Ask teammates for confidential feedback if you need to.

A few days beforehand, set up a 10-minute meeting with each employee to go over the review. Here’s how the agenda typically breaks down:

Minute 1: Explain that the goal of the review is to bring awareness to positive traits and areas to work on. The employee will work with his/her manager to craft an action and accountability plan. Then ask: “How do you feel like receiving advice today on a scale of 1 to 10? One is kind and nurturing, and 10 is pointed and direct.” This scale gives control to the employee, and the reviewer becomes the servant leader, playing by each employee’s rules and preferences. It requires quick thinking, but tailoring your messaging reassures the employee that this is about helping him/her. An important note: those who select 10 don’t get a mean boss; they just get a direct, cut-to-the-chase one. The people who pick lower numbers also get the same honest content, presented with softer words.

Minutes 2-4: The Tough or Love section. For responses 7 or higher, start with Tough. Begin with Love for anyone who says 4 or lower. Those who respond in the middle, 5 or 6, get this question, “What do you think needs work?” which brings Tough to the forefront so you can end on Love.

Minutes 4-6: Switch to the remaining section, either Tough or Love.

Minutes 7-10: Now, let the employee take the driver’s seat and provide whatever response they want to close out the review session. Borrow from the discipline of design thinking: observe and absorb without bias, and know that you can follow up later if needed.

Finally, remember that while we often assume that people like to receive feedback, there are also many studies that show people actually hate it. As Stanford’s Carol Dweck has found, people approach feedback with either a fixed mindset or a growth mindset. People with a fixed mindset believe their qualities are fixed traits (“I am who I am”), while people with a growth mindset believe their qualities are just starting points, which can be developed through hard work, shaping who they could become. But you can help nudge your team into a growth mindset by framing your feedback in terms of growth.

For instance, Ken Moran, our head of client accounts and essentially our entire HR department, shares the feedback from his Tough Love Review, which was to work on his defensiveness: “My job is to make sure problems don’t happen, and when they do, to handle them. I was reminded that being defensive undermines my ability to be a team player and leader…[because it was put in those terms] for the first time I got why I needed to change.”

Since we’ve implemented this approach, we’ve seen a significant constructive change in our employees. We’ve seen turnarounds in team dynamics, and Ken has received more accolades from clients on team performance. We’ve also seen evidence of employees empowered to act on the feedback: one employee signed up for a public speaking class; another mentioned interviewing career coaches to talk through the Tough Love feedback in more detail.

Approaching reviews this way gives company founders a meaningful touchpoint with each employee to thank them for the great work they do—and helps employees figure out what is holding them back from realizing their potential so they can help their career, and the company, flourish.

The Pace of Scientific Research Is Picking Up

What’s really going on in science? For centuries there was no real way of knowing. It took months and sometimes years to find out whether a study mattered, in science and in the real world. That’s changing, thanks to the internet.

When I left academia five years ago I was a published scientist and feedback was slow. Most of my articles had appeared around the year 2008, but 2012 was the year I got the most citations from other academic papers. Citations are a proxy for influence in science. If someone’s citing what you wrote it means that it’s getting read and potentially used to further an idea or take it in a new direction. In my case, by the time my work was having influence, I had swapped my lab coat for my laptop and started a company.

There are two explanations for the time lag between publication and influence in science. Perhaps my publications just weren’t getting any attention earlier because I published many of my articles in journals that kept them behind a paywall. It could also be that it took the people who read and cited my work some time to come out with their own papers. It was probably a mix of both. But to at least some degree the dissemination of knowledge was slowed down by the way those papers were published and stored.

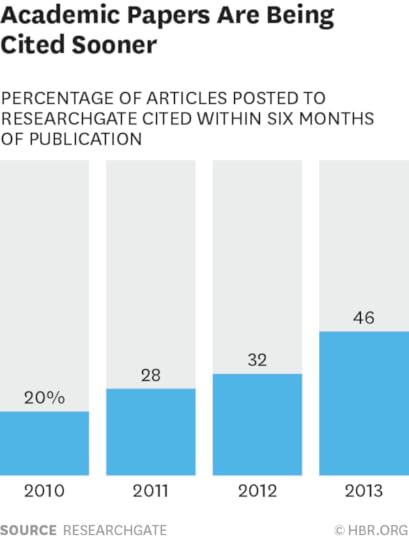

The good news is that this lag time is decreasing. Scientists upload their research to ResearchGate, the social network my co-founders and I founded in 2008, which provides us with a large dataset on how scientific process plays out. Here we see that of all articles published in 2010, only 20% had been cited six months later. Of all articles published in 2013, 46% were cited after six months. The cycle of scientific feedback and influence is speeding up.

What happened? For one, there’s more to discover without having to pay. More scientific literature is available earlier without being embargoed behind a paywall. A study in the journal PloS from 2013 showed that the rate of open access articles doubled from 2006 to 2010, from 26.3% to 50.2%. And on ResearchGate alone, full text downloads increased 140-fold from January 2013 to January 2015.

The citation lag time decreased by more than half in just three years, but more can be done to speed it up. Science will never be about rapid-fire responses, but it’s my hope that this cycle will continue to shorten. It should be easier for scientists to track interesting research in their fields (and outside them) and to see how their work is shaping other researchers’ thinking. At ResearchGate, anyone can now look at what researchers are reading in real-time. For instance, as I’m writing this article, hundreds of medical researchers are reading a paper on eradicating a bacterial infection which seems to have positive effect on the wellbeing of Parkinson’ patients. Another trending publication discusses inflammation related genes and their role in diabetes. Surely this interest tells us something important about the paper, and might interest others who’ve not yet read it, as well as the researchers themselves. In business, fast feedback like this is important. In science, it shows researchers whether they’re on track as well.

You’re Already More Persuasive than You Think

It’s amazing the opportunities we miss because we doubt our own powers of persuasion.

Our bosses make shortsighted decisions, but we don’t suggest an alternative, figuring they wouldn’t listen anyway. Or we have an idea that would require a group effort, but we don’t try to sell our peers on it, figuring it would be too much of an uphill battle. Even when we need a personal favor, such as coverage for an absence, we avoid asking our colleagues out of fear of rejection.

Yet our bosses and peers would be more receptive to our comments and requests than most of us realize. In fact, in many cases, a simple request or suggestion would be enough to do the trick. We persistently underestimate our influence.

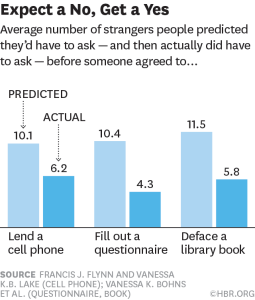

To get a sense of how far off people are in judging their influence, consider a set of experiments I conducted with Frank Flynn of Stanford: First, we asked each research participant to estimate how many people he or she would need to approach before someone agreed to fill out a questionnaire, make a donation to a charity, or let the participant borrow a cell phone.

Later, when the participants went out and made these very requests, strangers turned out to be twice as likely to say “yes” as the participants had expected. When they returned to the lab, many participants expressed surprise at how willing people were to go along with their requests. (In a separate set of studies, I found that the same holds true even when people ask others to engage in unethical behaviors, such as vandalizing a library book.)

This disconnect between expectations and reality is a particular problem in the workplace. Because most companies emphasize the rigidity and formality of their hierarchies, employees tend to assume that their influence is dependent upon their roles or titles — that if they lack official clout, they can’t ask for anything.

In research by Frances Milliken of New York University and two colleagues, the majority of 40 employees at knowledge companies reported having concerns about such issues as workflow improvement and ethics — but not speaking up about these issues to their supervisors. The belief that raising the issues would make no difference was the third most frequently cited reason. Said one employee: “Even if I did comment on the issue, it was unlikely to change anything.”

A major part of the problem is that employees tend to forget that managers are people too and that the dynamics affecting all relationships exist even in a boss-subordinate relationship. Bosses care about whether employees respect them, and they feel guilty and embarrassed if they let their direct reports down. However, people generally are unable to put themselves into the mindsets of those on the receiving end of requests. They don’t realize that the social pressure to comply with a request is very, very strong. It’s often harder for people, even bosses, to say “no” than “yes.”

To illustrate, imagine yourself in the following scenario: What would you do if you saw that the president of your company was failing to comply with a simple safety regulation? Would you stand up and ask her to comply? Or would you assume that as president of the company, she would simply brush you off? A team led by Joanne Martin of Stanford report a story of an assembly line worker who got up the nerve to ask her company president, as he was touring the production facilities, to put on his safety goggles. The president’s reaction? He turned “red with embarrassment” and quickly complied. This very human reaction suggests that the same self-conscious emotions and social pressures that drive students in a laboratory to comply with a request to borrow a cell phone affect everyone, right up to the president.

You might assume that if social pressure forces compliance, then succeeding in getting someone to agree to a request amounts to a hollow victory. After all, wouldn’t a person who gave in to social pressure, or was driven to comply out of guilt and embarrassment, end up resenting the asker? But that’s generally not the case.

Like all human beings, people who comply with requests unconsciously generate justifications for their actions. “If I granted this person’s request, I must like him,” is basically how the unspoken thought process works. So rather than feeling resentment, the person who complies with a request ends up feeling good about the asker. In fact, research suggests that the best method for smoothing over a conflict with someone may not be to offer help, but to ask for help. The target of the request is likely to comply, the justification process will follow, and feelings of positivity will start to restore the relationship. Try it. Or consider the coda to the story of the worker who asked the president to put on goggles: The executive eventually returned to tell her how impressed he was with her “guts.”

But again there’s a disconnect that stems from our inability to put ourselves in others’ mind-sets. We don’t realize that a request for compliance will stimulate a positive reaction. That’s partly because these unconscious processes aren’t widely understood, but it’s also because when we ask for something, we tend to focus too intently on our own feelings — of embarrassment, weakness, or shame — and don’t give enough rational thought to how others perceive us. We assume that persuading people will provoke enmity.

What this all adds up to is untapped potential: to influence others, to effect change, to blow the whistle on wrongdoing. We don’t venture to transcend our formal roles. We fail to benefit from others’ cooperation.

What happens when people do embrace the influence they didn’t know they had? They ask for things more readily. They don’t worry so much that people are going to refuse their requests. In a sense, they become more powerful — or at least they learn to acknowledge their latent power.

Take the story of Elizabeth, a part-time employee at a major New York City cultural institution whose boss and department head left in the middle of a massive organizational restructuring. Elizabeth herself had the expertise to take on the role, but she had an 8-month-old daughter at home and didn’t want to take on full-time work. Yet, given the organizational climate at the time, Elizabeth was worried that the senior management would simply cut her whole department — and programs she cared deeply about — rather than bring in a new person to run it. She had an idea for what to do, but she wasn’t sure whether the senior management would be willing to consider it. Despite her reservations, she came up with a proposal. She wrote out a job description in which she would take on the responsibilities of maintaining the department’s core programs, with the stipulation that her work hours would never exceed 30 hours a week and would be completely flexible.

The organization’s situation was extremely tenuous at the time, and Elizabeth was nervous approaching senior management with such an unorthodox proposal. “I felt incredibly vulnerable,” she said. But to her surprise, the management team agreed to all of her terms. “It wound up being the best job I could imagine,” Elizabeth said. “I had essentially hand-crafted it to meet my needs and utilize my skills. And I got to take my daughter to the park every afternoon. It was absolutely worth the risk and vulnerability of asking.”

Similar stories emerged when I polled my friends and colleagues — stories of asking one’s boss for a title change, a higher salary, a budget increase, or even just a smart phone — all accompanied by a sense of surprise each time at that magical response: “Yes.”

I find that my research has affected my own behavior: I’ve become more attuned to the things we don’t attempt, out of fear of being rebuffed. Because we’re not attuned to others’ motivation to help us, we limit our ambitions.

I’ve also learned to recognize the responsibility that comes with this latent power. Our words have surprising impact. Not only do we need to be careful about a throwaway comment’s possible unintended consequences — say something negative about someone’s recent absence, and another person in earshot might cancel plans for a needed personal day — but we also have an implied role when we see wrongdoing or room for improvement. Like it or not, we all have a powerful tool for making change: simple direct language.

How does all of this translate into getting what you need when you need it? Research my colleagues and I have conducted offers some practical suggestions on how to make requests.

Just ask. The number one mistake people make is psyching themselves out before even asking for something.

Be direct. Another common mistake is asking indirectly by dropping hints (“Hey Bob, what are you doing this weekend? I’m going to be working on a big project. I wish I had some more help…”). We think we’re being polite by doing so and that people will therefore be more likely to agree to our requests. But my colleagues’ and my research shows that people respond more positively to direct requests. (“Hey Bob, would you mind helping me out with a project this weekend if you have time?”)

Go back and ask again. Another assumption people make is that you shouldn’t ask a person who has previously said “no.” After all, if they said “no” once, they are likely to say “no” again, right? But another line of research by my colleagues and me shows that this assumption is not necessarily true; in fact, saying “no” can sometimes make people more likely to say “yes” to a subsequent request because they feel so guilty about having previously said “no.”

Incentives are not needed. Finally, we tend to think we need to offer someone something in return for a favor — a few dollars for the trouble. However, my research shows that people are just as likely to comply with certain requests for free as they would be in exchange for an incentive. People feel good when they can do something to help someone else out.

We tend to have a lot of misconceptions about influence — how much of it we have, the best way to wield it. Fortunately, the reality is more encouraging than we imagine. The power of a simple, direct request is much greater than we realize.

July 31, 2015

How to Bounce Back After Getting Laid Off

Losing your job is hard. It dents your self-esteem; it’s tough on your bank account; and if you’re not smart about your next steps, it can derail your career. Aside from getting back on the horse and looking for a new job, what else should you do to get back on track? How do you maintain your self-confidence? Who should you talk to about the situation? And how should you frame the layoff to future employers?

What the Experts Say

Getting laid off is perhaps the most professionally traumatic experience you’ll ever have. “The old adage that it’s not about you is nonsense,” says John Lees, the UK-based career strategist and the author of How to Get a Job You Love. “It’s a rejection — the company is saying, ‘We don’t need you. We can manage without you.’ It feels personal.” While it’s natural to feel this way, you mustn’t lose perspective. All in all, “getting laid off is a manageable setback on the scale of human experience,” Lees says. And it can even lead to something positive. “Try to think about it as an opportunity that’s ultimately going to do you some good,” says Priscilla Claman, the president of Career Strategies, a Boston-based consulting firm and a contributor to the HBR Guide to Getting the Right Job. “A lot of people stay in their jobs for too long; they get stuck and can’t move on.” A layoff gives you a fresh start. Here are other ways to bounce back from this difficult and often stressful situation.

Take a hiatus

In the immediate aftermath of a job loss, give yourself time to decompress by “taking a vacation of sorts,” suggests Claman. “You don’t need to go to Aruba, but take a break,” even if it’s just for a weekend or a few days, she says. Your goal is get out of your own head with a fun and “active hiatus.” Go hiking. Go camping. Go kayaking. “The first phase is recovery,” says Lees. Don’t make any big decisions in those first few days and don’t rush into the job market the day after you’ve received the news. You need time to process what happened and “how you feel about it.”

Do a financial assessment

Getting a handle on where you stand financially after a lay off is critical to keeping your stress and anxiety in check. Claman recommends doing an assessment that details your household budget in the context of your severance and any other unemployment benefits. “Figure out how long you have to look for a job — and give yourself as much time as possible to do so,” says Claman. “Also look at what you spend money on and think about ways you can cut back.” This shouldn’t be a solo endeavor, she says. “Involve your immediate family members and anyone else who’s financially reliant on you. You all need to understand the reality.”

Talk it out

When your emotions are still raw, you may feel a lot of “anger and resentment,” says Lees. That’s natural and it’s important to talk about those feelings. But share that story only with trusted friends and “people with whom you don’t need a script and who have no agenda,” he says. Tell it as many times as you need in order to resolve any “emotional baggage” and get it out of your system before you get in front of a recruiter. They will sense your bitterness, and it won’t reflect well on you, says Lees. “They will think: ‘Here is someone who’s been beaten up.’” Another danger of reaching out to recruiters before you’re psychologically ready is that you’ll be less likely to weather small setbacks such as not having your phone call or email returned. So before you make that call, Lees recommends asking your trusted circle for objective feedback on your job market-readiness. “Ask, ‘Do you think I’ve come to terms with the situation? Am I ready to go in front of a recruiter?’”

Frame your layoff

Once you’ve moved past your initial layoff story, work on crafting a simple explanation for your layoff that you can share with professional contacts and potential hiring managers, suggests Lees. Develop an “objective, short, and upbeat” message that shows you’re “not a victim and you’re not stuck.” Lees suggests saying something like: “My former company went through an extensive restructuring. I’ve been given an opportunity to rethink my career, and what I am looking for now is XYZ.” “It’s a strong technique that moves you from past to present to future in only a couple of sentences,” says Lees. And remember, redundancies and layoffs are “frequent occurrences” in today’s employment market, says Claman. “Everyone knows that it happens, and it’s acceptable.”

Surround yourself with positivity

As you begin to think about what your future may hold, it’s common to “feel flat and slightly depressed about your job prospects,” says Lees. The remedy is to surround yourself with “positive-minded people who will encourage you and help you move forward.” This group — comprised of mentors, former colleagues, and other professional connections—will help you catalog your strengths, remind you of your past accomplishments and achievements, and give you good ideas about what to do next. Family and friends play an important role here, too, adds Claman. “Explain to people that they will need to cut you some slack,” she says. “Say, ‘I’m going to need your help, your cheerleading, and your support.’”

Explore opportunities

Before you make any networking calls or answer job ads on Monster or Indeed, you need to get yourself together, says Claman. “Make sure your social media profile is up and running and [if applicable to your industry] that you have work samples in order,” she says. Then think about your job search in the broadest terms possible. Reach out to former colleagues and friends who work for organizations that interest you. “Talk to those people and get up-to-date on the latest issues and the new buzzwords. Think about headhunters you know. See if it’s worth becoming a member of a professional association,” she says. Lees recommends you network “with an exploratory mindset.” Your goal is to find out what’s going on in a given sector and organization and “learn what success looks like” in it, he says. Use what you glean from these conversations to rework your resume. The “language people use to describe success” should be reflected in “your LinkedIn profile,” he adds.

Sustain momentum

A job search requires incredible dedication. “It’s a volume game,” says Claman. “You need to have a lot of activity going on in order to get ahead, and if you get one callback for every 20 resumes you send out, you’re doing very well.” Don’t lose focus, she cautions. “The temptation when you get an interview or callback is to stop all other activities,” she says. “But if you don’t get the job, you have to go back to square one” and it can crush your confidence. In other words, even if you feel you’re getting close to a job, make sure you have other irons in the fire. One way to sustain momentum is to populate your calendar with professional meetings and networking events. “At least once a week, you need to put on smart clothes and take someone out for a business lunch,” says Lees. It will be a “positive, reinforcing experience for you.”

Tend to your wellbeing

The old cliché that looking for a job is a fulltime job holds some weight, “but try not to get obsessed by it and spend all your time staring at your computer,” says Lees. It’s unhealthy and often unproductive. “Take care of yourself.” Make sure you’re eating well, exercising, and getting plenty of sleep. “You need to keep your spirits up and your energy high,” says Claman. Watch your budget, of course, but don’t deprive yourself of fun. Most importantly, “be kind to yourself. Don’t be your own bad boss,” she says. “Don’t beat yourself up and don’t blame. Speak about yourself with pride.”

Principles to Remember

Do

Figure out where you stand financially by assessing your household budget in the context of your severance package and unemployment benefits

Craft a simple, upbeat explanation for your layoff to share with potential employers and contacts

Surround yourself with positive people to help you move forward

Don’t

Approach recruiters when you’re still emotionally raw — if you’re unsure of how you might come across, ask a trusted friend

Rush into the job market — instead, network with an exploratory mindset to uncover your next opportunity

Neglect your wellbeing — make sure you’re eating well, exercising, and getting enough sleep

Case Study #1 Decide how you’ll frame your layoff in a positive way

The day after John Denning* lost his job at a mobile technology company outside Boston, he took a long weekend in Maine. He went mountain biking, played golf, and hiked. “It was helpful to be in a different place and to step away from the routine of daily life,” he says. While away, John began to “think about next steps and how [the layoff] could be a good thing.”

John admits he felt angry about being laid off, but didn’t share his frustration with many people. He didn’t want to be seen as a victim. “I primarily vented to my wife,” he says. “And I moved quickly to frame the story of what happened in a positive way.” His story went something like this: “My company was acquired by a private equity firm that had different priorities. The acquisition has given me an opportunity to think about what I want to do next.”

John reached out to friends and former colleagues for advice and introductions and remembers that first flurry of networking as “easy and fun.” But “sustaining that was hard,” he says. “After that initial phase of personal networking to uncover opportunities, I moved into a less interactive phase where I was researching companies and looking at job postings online. Still I made sure I was doing a circuit of drinks, lunches, and calls to keep myself fresh.”

After three months, John accepted a job offer. He had spotted the posting online and — through his network of professional contacts — got a personal introduction to the hiring manager. “In retrospect, the entire experience was a good thing for me,” he says. “It was the first time in my life that I’d lost a job and it made me savvier. I realized I’m not untouchable. I am more aware about what goes on in companies.”

“It was also rewarding,” he says. “It was a reminder for me that I have a lot of generous and supportive people I can lean on.”

Case Study #2 Network with old colleagues to identify opportunities

The first emotion Paul Boyde* experienced after he lost his job at a non-governmental organization in Washington, D.C., was relief. “It didn’t feel good to be laid off, but at the same time, it was liberating to be let go of a job I was ready to move on from,” he says.

The second emotion he felt was worry. Paul’s wife, Susan, was six months pregnant. Susan had a relatively high-paying job, but still Paul felt uneasy. “I created a spreadsheet that looked at all our income and savings against all our monthly outgoings,” he says. “Knowing where we stood — and that we had enough money in the bank — made me feel less stressed about taking my time to find the right opportunity. It also helped to know that we could afford to order takeout and go to the movies every once in a while.”

To figure out what he wanted to do next, Paul emailed former colleagues, bosses, and classmates from graduate school and invited them for coffee or lunch. It was a “twofer,” says Paul, “I caught up with old friends and coworkers and I got to hear about their jobs and organizations.” The experience was also a self-esteem boost: “At a time when my confidence had taken a hit, they reminded me about what I was good at and helped me think about where my skills would be best put to use.”

During one of these meetings, Paul was introduced to the director of an NGO. “The director didn’t have a fulltime job that was quite right for me, but she offered me a consulting project that involved me interviewing the heads of other NGOs in the region,” he says. “It was perfect. I got to do interesting work; I got to network with potential employers; and I was able to make a little money.”

Four months later, Paul landed a new job with one of the directors he interviewed for the project. “I am much happier in this position and the job is more suited to my interests,” he says.

*Names have been changed

Companies Collect Competitive Intelligence, but Don’t Use It

The first requirement for being competitive is to know what others in your space are offering or plan to offer so you can judge the unique value proposition of your moves. This is just common sense. The second requirement is to anticipate response to your competitive moves so that they are not derailed by unexpected reactions. That’s just common sense, too.

The third requirement is to ask the question: Do we have common sense?

In my work in competitive intelligence I have met many managers and executives who made major decisions involving billions of dollars of commitments with only scant attention to the likely reaction of competitors, the effect of potential disruptors, new approaches offered by startups and the impact of long-term industry trends. Ironically, they spent considerable time deliberating potential customers’ reactions, even as they ignored the effect of other players’ moves and countermoves on these same customers. That is, until a crisis forced them to wake up.

In my experience, the competitive perspective is almost always the least important aspect in managerial decision-making. Internal operational issues including execution, budgets, and deadlines are paramount in a company’s deliberation, but what other players will do is hardly ever in focus. This “island mentality” is surprisingly prevalent among talented, seasoned managers.

The paradox is that companies spend millions acquiring competitive or market “intelligence” from armies of vendors and deploy the latest technology disseminating the information internally. Some estimate the market for market research alone at $20 billion annually. Specific competitor information is another $2 billion. On the other hand, management never questions the actual use of this information by employees in brand, product, R&D, marketing, business development, sales, purchasing or any other market-facing function. Instead, management implicitly assumes the information is being used, and used optimally. Leadership is happy to ask that proposals and presentations be backed by “data.” Every middle manager is familiar with the requirement for a 130- slide deck of tables, graphs and charts in the appendix for presentations to top executives.

Yet no one asks: which of the information purchased at high cost from the outside army of research vendors and consultants was ignored, missed, discounted, filtered or simply not used correctly?

What Did Peter Drucker Really Say?

Peter Drucker is often quoted as coming up with the managerial bromide, “What gets measured gets managed.” Yet this does not actually represent his thoughts on measurement. Some have argued that he never actually said that at all; others have claimed that the quote has been mangled, and that in context, it was part of a larger lamentation that managers would only manage what was easy to measure, rather than what was important or useful. Regardless, it’s clear from Drucker’s writings that he worried that management often measures the wrong things, and believed that some critical aspects of management can’t actually be measured.

And the impact of competitive information on an organization’s decisions is one of those things that can hardly ever be measured. It is neither direct, nor unambiguous. Since impact can’t be measured and therefore results can’t be directly attributed to the competitive information, management resorts to measuring the wrong thing, exactly as Drucker feared. For example, in several companies I worked with, management measured output. How many reports did the analysts issue? How many research projects were completed within budget and on time? This is the equivalent of searching for your car keys under the street lamp simply because that’s where the light is.

The failure to measure the impact of competitive data leads to an interesting dilemma for companies: even when it’s obvious that the company has missed an opportunity or been blindsided by a threat because they failed to consider competitive data, managers are at a loss how to improve the situation.

Improving decision quality – measured as the extent to which decision makers use all available competitive information- requires focus on usage rather than production of intelligence. This is a major mindset leap for most companies but if offers a way to improve decisions without directly measuring the elusive impact. Just ensuring that managers look at and consider competitive perspective should in principle, improve decisions. How can companies achieve that?

A Simple Yet Powerful Suggestion

Improving competitive intelligence usage requires an “audit” of major decisions – at the product/service or functional level – before they are approved by management. This competitive intelligence sign-off is simple to institutionalize. It replaces the haphazard dissemination effort of mass of information (much of it may be just noise to the user) with systematic competitive perspective.

Would a manager submit to a “sign-off” voluntarily? Maybe. Over the years I have encountered many managers who wanted to stress-test their plans and thinking against third parties’ likely moves via war games. But war games are the more advanced step, and they are typically not systematically applied in an organization. A competitive “audit” or review is the more basic level. The potential cost saving or growth opportunities afforded by institutionalized competitive reviews of major initiatives and projects can be significant. A byproduct of these reviews would be better use of costly information sources, or rationalization of the cost of these sources.

That said, a company can’t force its managers to use information optimally. It can, however, ensure they at least consider it. In many areas of the corporation, mandatory reviews are routine- regulatory, legal, financial reviews are considered the norm. Ironically, competitive reviews are not, even though the cost of missing out on understanding the competitive environment can be enormous. Consider this admittedly extreme example. Financial institutions are known to spend billions on mandatory regulatory and legal reviews of their practices. How much do they spend on mandatory competition review? To judge by the measly performance of mega banks’ in the past two decades, compared with more locally focused smaller banks, not much (The Economist, March 5, 2015, “A world of pain: The giants of global finance are in trouble”).

Drucker did say, “Work implies not only that somebody is supposed to do the job, but also accountability.” If managers choose deliberately to ignore the competitive perspective, they should be held accountable. And it is only reasonable to ask top management to apply the same principle to itself: a systematic, mandatory, institutionalized strategic early warning review may keep major issues on the table.

Think about it this way: If competition reviews were mandatory at Sears, Motorola, Polaroid, AOL, Radio Shack and A&P, to name a few, would they have failed to change with the times? We would never know. Common sense suggests a company shouldn’t wish to find out.

7 Ways to Improve Employee Development Programs

Making the right investments in learning and development programs has never been more important – or more of a challenge – for business leaders.

Unfortunately, despite spending approximately $164.2 billion dollars on learning and development programs, many executives still grapple with how to improve and enhance their effectiveness. As research shows, the need to revamp and improve learning programs is an important concern among HR executives.

To better understand this problem, my consulting firm did a thorough review of recent research into learning and development programs, followed by a structured survey with top training executives at 16 major corporations in a diverse set of industries, ranging in size from $1 billion to $55 billion in annual revenues. To understand how providers of training and development view these challenges, we also interviewed leaders of executive education programs at several leading universities.

From this research, we’ve observed seven challenges companies must meet to create development programs that really work:

1. Ignite managers’ passion to coach their employees. Historically, managers passed on knowledge, skills, and insights through coaching and mentoring. But in our more global, complex, and competitive world, the role of the manager has eroded. Managers are now overburdened with responsibilities. They can barely handle what they’re directly measured on, let alone offer coaching and mentoring. Organizations need to support and incentivize managers to perform this work.

2. Deal with the short-shelf life of learning and development needs. It used to be that what you learned was valuable for years, but now, knowledge and skills can become obsolete within months. This makes the need to learn rapidly and regularly more important than ever. This requires organizations to rethink how learning and development happens from a once-in-a-while activity, to a more continuous, ongoing campaign. As Annette Thompson, Senior Vice President & Chief Learning Officer at Farmers Insurance pointed out in an interview, avoiding information overload is vital, so organizations must strike a balance between giving the right information versus giving too much.

3. Teach employees to own their career development. Highly-structured, one-size-fits-all learning programs don’t work anymore. Individuals must own, self-direct, and control their learning futures. Yet they can’t do it alone, nor do you want them to. The development and growth of your talent is vital to your ongoing success, ability to innovate, and overall productivity. It’s a delicate balance, one Don Jones, former Vice President, Learning at Natixis Global Asset Management summarized like this: “We need to have ‘customized’ solutions for individuals, while simultaneously providing scale and cost efficiencies across the organization,” he said.

4. Provide flexible learning options. Telling employees they need to engage in more learning and development activities with their already heavy workload often leaves them feeling overwhelmed and consumed by the question, “When and how will I find the time?” Companies must respond by adopting on-demand and mobile solutions that make learning opportunities more readily accessible for your people.

5. Serve the learning needs of more virtual teams. While most organizations have more people working remotely and virtually, it does require more thought and creativity in how to train this segment of your workforce. This includes formal types of learning through courses, but also the informal mentoring and coaching channels. Just because employees are out of sight doesn’t mean they get to be out-of-mind when it comes to learning and development.

6. Build trust in organizational leadership. People crave transparency, openness, and honesty from their leaders. Unfortunately, business leaders continue to face issues of trust. According to a survey by the American Psychological Association, one in four workers say they don’t trust their employer, and only about half believe their employer is open and upfront with them. If leaders disengage or refuse to share their own ongoing learning journeys, how can they expect their people to enthusiastically pursue theirs? It’s the old adage of “lead by example.” If managers want employees to engage in learning and development, then they need to show that they are actively pursuing their own personal learning journeys as well.

7. Match different learning options to different learning styles. With five generations actively in the workforce, organizations must restructure the way employees learn and the tools and activities they use to correctly match the different styles, preferences, and expectations of employees. For example, Millennials came of age using cell phones, computers, and video game consoles, so they expect to use these technologies to support their learning activities.

As leaders, we know the value our learning and development programs bring to our organizations. But we also want to ensure we’re receiving a high return on investment. By clearly understanding the trends emerging in our learning and development programs, we’ll better position our companies to select the right targeted solutions to drive results, increase employee engagement, and increase innovation and productivity.

What You Miss When You Take Notes on Your Laptop

HBR STAFF

Even in my relatively short foray into office life, I notice that few people bring a pen and notebook to meetings. I’ve been told that over the years, the spiral notebooks and pens once prevalent during weekly meetings have been replaced with laptops and slim, touch-screen tablets.

I suppose it makes sense. In a demanding new age of technology, we are expected to send links, access online materials, and conduct virtual chats while a meeting is taking place. We want instant gratification, and sending things after the meeting when you’re back at your desk feels like too long to wait. It seems that digital note-taking is just more convenient.

But is longhand dead? Should you be embarrassed bringing a pen and paper to your meetings? To answer these questions, I did a little digging and found that the answer is no, according to a study conducted by Princeton’s Pam A. Mueller and UCLA’s Daniel M. Oppenheimer. Their research shows that when you only use a laptop to take notes, you don’t absorb new materials as well, largely because typing notes encourages verbatim, mindless transcription.

Mueller and Oppenheimer conducted three different studies, each addressing the question: Is laptop note taking detrimental to overall conceptual understanding and retention of new information?

You and Your Team

Business Writing

Don’t let poorly-crafted communications hold you back.

For the first study, the researchers presented a series of TED talk films to a room of Princeton University students. The participants “were instructed to use their usual classroom note-taking strategy,” whether digitally or longhand, during the lecture. Later on, the participants “responded to both factual-recall questions and conceptual-application questions” about the film.

The students’ scores differed immensely between longhand and laptop note takers. While participants using laptops were found to take lengthier “transcription-like” notes during the film, results showed that longhand note takers still scored significantly higher on conceptually-based questions. Mueller and Oppenheimer predicted that the decrease in retention appeared to be due to “verbatim transcription.”

But, they predicted that the detriments of laptop note taking went beyond the fact that those with computers were trying to get every word down. In their second study, Mueller and Oppenheimer instructed a new group of laptop note takers to write without transcribing the lecture verbatim. They told the subjects: “Take notes in your own words and don’t just write down word-for-word what the speaker is saying.”

These participants also watched a lecture film, took their respective notes, and then took a test.

They found that their request for non-verbatim note taking was “completely ineffective,” and the laptop users continued to take notes in a “transcription like” manner rather than in their own words. “The overall relationship between verbatim content and negative performance [still] held,” said the researchers.

In a third study, Mueller and Oppenheimer confronted a final variable — they found that laptop note takers produced a significantly greater word count than longhand note takers. They wondered, “Is it possible that this increased external-storage capacity could boost performance on tests taken after an opportunity to study one’s notes?” So while the immediate recall on the lecture is worse for laptop note takers, do their copious notes help later on?

For this study, participants “were given either a laptop or pen and paper to take notes on a lecture,” and “were told that they would be returning the following week to be tested on the material.” A week later, they were given 10 minutes to study their notes before being tested.

And again, though the laptop note takers recorded a larger amount of notes, the longhand note takers performed better on conceptual, and this time factual, questions.

This final test clarified that the simple act of verbatim note taking encouraged by laptops could ultimately result in impaired learning. “Although more notes are beneficial, at least to a point, if the notes are taken indiscriminately or by mindlessly transcribing content, as is more likely the case on a laptop than when notes are taken longhand, the benefit disappears,” said Mueller and Oppenheimer.

Though your days of cramming for tests may be over, you still need to recall pitches, dates, and statistics from meetings. That’s why we take notes in meetings. And while there are plenty of ways to work smarter with digital tools, you may remember more if you leave the laptop or tablet at your desk and try bringing a notebook and pen instead.

In addition to your mode of note taking, be extra aware of what you’re writing. Are you focusing more on recording what a speaker is projecting on a slide show, rather than actually listening to what is being said? Write your notes in your own words. It’ll encourage you to process and summarize what is being said rather than just regurgitating it.

Of course, not every meeting is the same, so you need to be able to distinguish what type of meeting you’re attending. Bring your laptop or tablet if you know you’ll need to just record a few key dates or a to-do list — and if you need access to materials or the internet. But keep in mind that meetings such as presentations, progress reports, and performance reviews contain information you need to stick. If you ditch your digital ways, and bring the pen and spiral notebook; your memory may thank you.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers