Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1269

July 28, 2015

Who Benefits from the Peer-to-Peer Economy?

Barbara Ann Berwick drove for Uber for eight weeks in 2014. She, and two others, then brought suit against the company. On June 16, the California Labor Commission ruled that she as a driver should have been classified as an employee – not an independent contractor – and that she was due over $4 million in expenses and penalties. As expected, Uber filed its rebuttal on July 9, bolstered with written statements from more than 400 drivers supporting the company.

Are Uber drivers being exploited or fairly compensated? Should governments, consumers, and voters support or suppress the movement towards increasingly freelance labor? It depends.

The 150-year history of industrial capitalism has led the US (and others) to tie benefits and workplace rules to full-time employment. “Choose the full-time job with benefits!” parents urge their children.

Yet, in countries with national health benefits, free childcare, low-cost higher education, and robust social safety nets, working as an independent freelancer is great, and it is easier than ever with new, Internet-enabled platforms.

Jamie, who lives in France, sells handmade stationery on Etsy while working part-time as a family therapist. “I cannot imagine working for someone else. Being my own boss affords me the independence and flexibility I need to express my creative processes, be they typically artistic or intellectually creative. I am not tied down to other people’s wants and expectations and can choose the paths I want or need to focus on at any particular stage in my life.”

Sidney, who was working as an Uber driver in New York City when we met, told me that he loved being able to control the amount of money he’d earn in a week. If he needed $400 to cover rent, then he’d work the necessary hours to earn it. He told me if you were smart and hardworking, working for yourself was the only way to go. Yet I worried that his calculus didn’t include the full costs of the car, or factor in sick and vacation days, health insurance, or the inevitable retirement that stretched ahead.

This new way of working also rewards the ambitious, the hardworking, and the entrepreneurial, and it moves us closer to a real meritocracy. Our résumés become irrelevant, and we can try our hands at many things and more quickly figure out what we want to do more of. In the famous New Yorker cartoon, a dog seated at a computer says to another one looking on, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” We’ve moved beyond that. With the rise of social networks (and expectation of NSA-level spying), it’s become more true that “everyone knows you’re a dog, and nobody cares.” It’s your work product and your reputation that matter.

According to Economic Modeling Specialists International, the number of freelance workers in the U.S. grew from 20 million in 2001 to 32 million in 2014. Freelance work now comprises almost 18 percent of all jobs. This trend is expanding explosively. And not just because workers are unemployed or unable to make ends meet with traditional jobs (although this has some truth in it) but also because companies are finding it advantageous to rely on freelance labor.

It used to be that companies would gain a competitive edge by bringing more and more people, assets, and resources inside the company in order to reduce transaction costs. The Internet has stripped that advantage away. Now, the smartest companies are using the Internet’s ability to facilitate collaboration by leveraging assets, resources, and expertise outside of their sphere of control. I call this new collaboration “Peers Inc.” and we are seeing its transformative and disruptive power in every sector of the economy.

As early as 2000, Zipcar (which I co-founded) built a platform that empowered its members to do work that used to be done by car rental employees. The platforms created by Uber and Lyft (who invented the idea) have redefined what it means to be a taxi and a taxi driver, and Airbnb has done the same with hotels and hoteliers. The effect extends well beyond what has been called the “sharing economy” – featuring many instances of peer-to-peer coordination of the use of assets — to what I think of as the collaborative economy: marked by many platforms that engage a diversity of peers to contribute excess capacity which can be harnessed for greater impact.

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are challenging work flows in the education sector. 3D printing will restructure manufacturing. The music and print media – in fact, all content producers – have had to transform as new platforms increasingly give the small the powers of marketing and distribution that were once reserved for the very large.

Companies like these, who tap directly into the full diversity and energy of their human marketplaces, are able to scale faster, learn faster, innovate and adapt faster. Whether companies like this new approach or not wholly depends on whether they are part of the old or new economy.

Governments need to recognize and prepare for this new third way of working which is neither full-time nor temporary part-time, but a new way of life. The Internet exists and everything that can become a platform will. Local and federal governments need to start tying benefits to people and not jobs, ensuring that labor is protected during this disruptive and swift transition.

In a world struggling to cope with incessant disruption brought on by fast-paced technical innovation, climate change, urbanization, and globalization, Peers, Inc. is the structure for our times. It enables us to experiment, iterate, adapt, and evolve at the required pace. I’m happy this flexible new tool has come to exist. But while we are reaping the economic benefits brought on by individual contributions, we need to proactively share the productivity and innovation gains with individuals, too.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

Yes, Your Résumé Needs a Summary

How long will recruiters spend on your résumé before deciding to toss it in the recycle bin? Six seconds, says online job search site The Ladders. That’s about 20 to 30 words.

So how do you write those first few lines of your resume—the summary section—to compel the recruiter to keep reading? How do you make sure you get the call—and not the toss? How do you make your summary memorable?

Here’s a checklist:

Tailor your summary to each job application. Highlight your areas of expertise most relevant to that position.

Then focus on specific results you’ve achieved in those areas of expertise—how other organizations have improved because of you.

Note the types of organizations and industries you’ve worked in.

Include years of experience.

Avoid generic terms such as results-driven, proven track record, excellent communication skills, team player.

Let’s look at a few examples of powerful summaries:

“Pharmaceutical marketing executive with 20 years of experience creating commercial infrastructures, growing brands, and optimizing product value throughout launch, re-launch, and sunset life cycles across all customer segments—payers, physicians, and patients. Lead global marketing and commercial operations teams with P&Ls up to $2B.”

“EHS director with 20 years of experience driving regulatory compliance and employees’ health and safety across industries—manufacturing, retail, and healthcare. Develop award-winning, injury-reducing ergonomic equipment. Launch LMS training programs and engaging websites to inform thousands of employees.”

“Online ad sales director with 12 years of experience leading sales teams in start-up, rapidly growing, and established companies. Maximize profitability of ads across all platforms, including games, mobile, social, and web. Consistently exceed revenue targets—even when battling Facebook and other relentless competitors in crowded markets.”

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Better Business Writing

Communication Book

Bryan A. Garner

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Now let’s look at how these summaries followed the checklist:

Tailor your summary to each job application. Make a list of the three or four most important responsibilities of each posting and then highlight those in your summary. This immediately tells the hiring manager that you’ve solved the same types of problems she’s dealing with. And it’s worth her time to keep reading and then interview you.

Focus on specific results. How have other organizations benefited from your work? And which of your accomplishments distinguish you from other candidates?

The marketing executive (above) built commercial infrastructures from scratch, made drugs profitable from launch to sunset, and managed $2B P&Ls. The EHS director invented award-winning ergonomic equipment—quite a distinctive accomplishment within his more general health and safety achievements. And the sales director broke into the online game market with sponsored ads. He also left the reader eager to know more by noting his David and Goliath-like confrontation with Facebook.

Note the types of organizations and industries you’ve worked in. The marketing executive began her summary with “pharmaceutical”—the one industry she’s worked in throughout her career. The EHS director highlighted his work across three industries–retail, manufacturing, and healthcare. And the sales executive noted his accomplishments across media companies at three stages of development—start-up, growth, and well-established.

Now, if you’re applying for a position in an industry different from the one you’re currently in, here’s an example of an alternative structure for your résumé summary. This person was applying for a senior project manager position at Disney, but her most recent work was in children’s museums:

“Project manager with 18 years of experience leading cross-functional teams to deliver children’s technology products and family museum experiences to international audiences.

Strategy leader for brands with complex and diverse product lines.

Communicator skilled at exciting audiences at conferences, online, and in products and exhibits.”

She called attention to the three areas of expertise most important to the Disney position—project management, strategy leadership, and communication–using bullets and bolding. She then followed this summary with a Selected Accomplishments section documenting her achievements in each of those areas. The second page of her résumé used the more traditional Experience format to describe her positions in descending chronological order.

Avoid generic terms. Rather than simply claiming to be results-driven, all these summaries state the results the applicants achieved. Eschewing overused terms enables recruiters to immediately see what you’ve done, peak their interest, and encourage them to learn more.

A note about LinkedIn: Unlike three- or four-line résumé summaries, you have up to 2,000 characters in the summary section of your LinkedIn profile to highlight accomplishments and connect them to what you want to do next. For much more detail about how to write a LinkedIn summary, read How to Use Your LinkedIn Profile to Power a Career Transition.

The other sections of your resume are, of course, also important. But it’s a rich, accomplishment-focused summary that will stop the reader in her tracks and keep her from passing you over for the next candidate. Make it immediately clear that you have what it takes to excel in her position. Distinguish yourself from other applicants. And expect the phone to start ringing.

Customers Like Self-Service, Unless It Undermines Customer Support

Due to my inadvertent idiocy, I lobotomized my smartphone by accidentally deleting an essential function. After 20-plus minutes of laptop Googling, Binging and YouTubing for a quick fix, I gave up. Nothing helpful could be found.

Two days and mounting frustrations later, I pop into a Sprint store and whine for support. It takes the (very helpful) sales associate four swipes and fifteen seconds to make my phone smart again. After thanking her, I asked how she did it. She quickly demonstrates. I tell her I couldn’t find that on the Internet. She eagerly explains that my search needed to include the words “wallpaper” and “widgets.”

She was being serious, of course.

This sort of self-help is all too common. Survey after customer research survey suggests that even customers happy with self-service become less than thrilled with their options when—not if—something goes wrong. With apologies to the Poka-Yoke crowd, “fool-proof” is a moving target. Mistakes will be made. Accidents will happen. Customer-centricity that confuses and conflates self-service (systems design approach that lets people service themselves efficiently, effectively, and conveniently) with self-support (self-service when things go wrong) is bad design. Self-service optimizes what’s supposed to happen; self-support deals with what’s not supposed to happen. While I had a great (and brief) experience with the sales associate in the store, it would have been even better to have easily and quickly found the 15-second fix myself online.

True customer-centricity requires that answers can be quickly found and easily implemented with a minimum of muss and fuss. Respectful UX design doesn’t just lie in how quickly and easily customers can do what they want; it depends on how quickly and easily they can fix—or recover from—something that’s gone wrong. That should hold as true for the average, typical user as for the most knowledgeable and motivated. Indeed, average users are the likeliest to need the easiest, quickest and simplest support. “Undo” buttons aren’t enough.

Doing self-support should be as easy—or easier—than not doing self-support.

At one industrial equipment supplier, for example, a comprehensive review of customer support processes revealed that if just one-in-12 customers could better self-diagnose their technical issues, the firm could save roughly $10 million in maintenance costs in less than 18 months.

The problem? Equipment design teams had been so focused on prevention that error messages typically obscured root causes of the problems. Their diagnostics were overwhelmingly designed for engineers and trained technicians, not the everyday equipment operators. Most of the time, that didn’t matter. But the growing global size and complexity of the company’s systems converted this increasing inability to self-diagnose into costly technical interventions. Even a little self-support would go a long way. Emphasizing expert diagnostics and maintenance information at the literal and figurative expense of users scaled poorly. The UX failed to cost-effectively balance self-service with self -support.

The firm consequently revisited and revised use cases that undermined simple, fast and cheap customer self-support. Unsurprisingly, this review led to even greater process efficiencies and innovative approaches to new remote diagnostics. The company offered a free automated “chat support” function that could typically handle the most common fault modes without human intervention.

Equipment support teams were rewarded if issues could be resolved without click-to-call human support. The equipment operators were effectively being trained as collaborators in troubleshooting and self-support. Intriguingly, according to one large account executive, customers didn’t mind technical issues if they were easy to identify and simple to fix.

Needless to say, those chat scripts quickly became both checklists and recipes for self-support. Faster, better, and cheaper self-support bought more time and greater insight for presenting next-generation upgrades.

“Ease of use” as a design ethos should never be minimized or marginalized. But as systems and services become more complex and complicated, “ease of fix” deserves and demands greater design attention. An ounce of prevention may indeed be worth a pound of cure. But that’s a poor excuse for underinvesting in cures.

How Social Movements Change Minds

Marketers tend to like big, bold actions that grab attention and spew off metrics. Yet all too often, we ignore the much more mundane work that comes before. To market a product or an idea, you have to change minds, and that takes time and a lot of careful work.

That’s a lesson we’ve seen over and over in the social movements of the last century—although the outside observer may only notice the movement when the dominoes start falling, the people inside the movement worked tirelessly for months, years, or even decades, to change minds.

The arc of history is long—the length of a career, rather than a marketing campaign. And yet despite the differences, there are several lessons that marketers can learn from successful social movements.

First, successful movements start by attacking perceptions. For instance, at the beginning of the Civil Rights movement, many people thought of it as a “black problem” or a “southern problem” or even a states rights issue. However, a large part of the success of the movement was getting people to see that it was a fundamental problem of national identity.

Consider the March on Washington in the summer of 1963. That was when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his historic “I Have A Dream” speech. It designed to appeal to mainstream America. King’s invoked the Declaration of Independence, speaking not just to the problems of African Americans, but also to the founding principles of the republic. Even people who hadn’t experienced oppression had internalized the ideas embedded in that document.

Cognitive psychologists call this framing and it plays into how our brains work. We are not, as many would have us believe, rational calculators. We see things in the context of connections that already exist in our minds.

Framing and reframing is also something that successful marketers must also know how to do. When Helen Gurley Brown took over Cosmopolitan magazine, she transformed it from a guide for housewives to an icon of independence. Steve Jobs, when he returned to Apple, shifted the Macintosh from a standalone computer to a hub for devices.

Second, successful movements build connections through personal contact, rather than trying to burst on the scene all at once. This point is especially salient today, when modern day movements like those that resulted in rights for the LGBT community or in taking down the Confederate flag seem to explode onto the public consciousness as a result of a single event or court case. It’s easy for marketers looking to emulate their success to take note of the end game while ignoring the opening moves.

To return to our historical example, although the March on Washington is probably the most famous event of the Civil Rights Movement, its success built on years of effort. It was the culmination of hundreds of smaller events—sit-ins, boycotts and protests—staged by groups in cities and towns throughout the south.

More recent movements, such as Otpor in Serbia, have taken a similar approach, focusing on growing organically through attraction. Contrast that with the Occupy Movement, which quickly spread from its origins on Wall Street, but then died out almost as fast. Although much of its rhetoric about inequality still resonates, the movement itself is long gone. While there were many reasons for its failure, a big one is that it didn’t do the hard work of building connections both inside and outside the movement, and therefore lacked the mechanisms of governance needed to fulfill a specified purpose.

That brings us to the third essential attribute of successful movements: they connect to the mainstream.

This makes all the difference. While it may be more comfortable to cater to passionate enthusiasts, unless you can appeal to the mainstream, you won’t get very far. After all, while the Civil Rights Movement called for change, it was leaders outside it, like Lyndon Johnson, that codified that change with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Civil Rights protesters were careful to attract mainstream support even as they defied authority. They showed up well dressed, spoke to police and other authority figures respectfully, and eschewed violence. That’s what allowed those outside the movement to identify with and admire them. For instance, as John Lewis describes in Walking With The Wind, a few months before the march, Robert Kennedy turned to him and said: “The people, the young people of the SNCC, have educated me. You have changed me. Now I understand.” Movements gain traction when they attract new members.

Similarly, as Byron Sharp argues in How Brands Grow, the only way to build a successful brand is to reach new customers. While many marketers find comfort in catering to loyal customers, that will almost surely lead to irrelevance. Research shows that bigger brands tend to have higher loyalty rates anyway. Far too often, brands strive to be “edgy” in order to differentiate themselves, but end up alienating far more than they inspire. That may fire up the loyal base, but it limits the potential for growth.

Successful brands, like successful social movements, are about aspirations and aspirations are always about a better future. They seek to include, not exclude.

Probably the most important thing brands can learn from the Civil Rights movement is that it not only clearly defined its mission and values, but was in turn defined by them. Its determination to create a better world necessitated a commitment to nonviolence. That same commitment to nonviolence inspired supporters and diminished opponents. Its mission drove its strategy, not the other way around. Today we remember the movement for what it built, not for what it set out to destroy.

Great brands operate the same way. Rather than relying on empty slogans and artful positioning, great brands, like great movements, aspire not merely to sell more stuff, but to create a positive impact on the world.

July 27, 2015

Greece’s Problem Is More Complicated than Austerity

It is easy to see Greece as a clash between “austerity” and “progressive economics,” with the Germans (and Finns and Dutch, alongside various international public servants and economists) on one side, and Keynesians and progressives on the other as Paul Krugman’s recent CNN interview suggests. This has certainly been the picture painted by Syriza, the left-wing political party of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, and by many friends of Greece and progressive economists.

The reality, though, is more complicated. To be sure, excessive austerity is bad macroeconomic policy. But the issue at stake isn’t just austerity. The issue is that Greek “resistance”—not just Syriza’s, but also that of the previous government—takes the form of protecting rent-seekers. This is where the July 2012 memorandum of understanding between Greece and the Troika (the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank, and the European Commission) failed miserably; the previous government, much like Syriza, wanted to preserve the status quo.

Greece’s main economic problem is structural and an exit from the Eurozone will not solve it. Besides the short-term costs of such a move, history shows us that Greece has never managed to benefit from currency devaluations. What’s more, the recent McKinsey study on Greek competitiveness shows that the country’s biggest challenge has been a lack of investment.

Exit from the Euro would only increase that capital scarcity, as the foreign exchange uncertainties would need to be factored in. For a country that isn’t export-oriented, and whose major industry, tourism, relies on stability, having its own currency is not much of a solution to economic woes. The lack of investment, along with red tape, byzantine regulations, and corruption make it fiendishly difficult for new businesses to grow. This, more than anything else, explains why Greece been unable to benefit from lower wage costs in developing its economy.

The problem is compounded by the fact that many groups have strong motivations for preserving the status quo. From taxi and lorry drivers to lawyers to pharmacists to milk producers, regulations protect incumbents and forestall the introduction of new business models. On the social front, some groups enjoy truly outrageous benefits, even as others suffer. Take the case of pensions: the average pensioner under 55 is getting 46% more than the average pensioner over 70.

The previous PASOK and ND governments resolutely failed to address these evolutionary, structural problems, which create “haves” and “have-nots”; sets of incumbents (usually connected to the government) and outsiders. Justice can hardly be served when court proceedings take over seven years on average to reach a conclusion. And it all revolves around a statist model, with politicians creating influence zones.

It isn’t only the branded pundits who are neglecting these issues. Over the last few years, focused fiscal consolidation also failed to fix these underlying problems. The 2012 memorandum of understanding was supposed to address them, but Greek governments had neither the capacity nor the will to change. Yet if we want to understand and fix the Greek crisis, we must look at its structural causes, not just its symptoms.

Many reports have portrayed the Syriza government as the defenders of social justice and Greek national pride. On the latter, they have indeed done a terrific job—albeit at a heavy economic cost. But on social justice the claim is more than questionable. For all the party’s talk of “social justice” and “solidarity,” only €200 million has been granted to cope with Greece’s human crisis, and it has still not been fully disbursed. Meanwhile, the retirement fund for pensioners of DEO, the state electricity company, continues to receive an annual state subsidy to the tune of €600 million—at a time when most pensions are being slashed. Syriza, which is close to DEI unionists, even instituted a canteen subsidy a few weeks after taking office. Not only is there a lack of will; there’s a critical lack of skill. In the recent government reshuffle, a former comedian with no policy experience was made Minister of State for Pensions. He is a vociferous member of ANEL, Syriza’s far right-populist partner.

As for all Syriza’s pre-election noise about “oligarchs”, nothing has happened beyond a few nice headlines. And it’s interesting to note that although the party had threatened to check the licenses of the rich “entrepreneurs” who own the key media, they shelved the pledge a few weeks into their administration—after which media coverage of the party became broadly supportive (at least until the crisis peaked). Business as usual?

On tax evasion, despite clear evidence of malfeasance, and nearly 450,000 identified possible tax evasion cases, there have been no new concrete measures whatsoever. Syriza did change the makeup of the panels who evaluate corrupt officials, though: rather than judges, they now feature local union reps. And they did away with the rule that state officials found guilty of corruption could no longer work—now, those convicted can stay at their unit during the five- or six-year appeal process.

The record on economic policy-making is equally disappointing. Although former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis made eloquent appeals about the need to rethink macro, he said very little about changing how the economy is run. In his first four months in office, he put his signature to 403 documents, 245 of which were approvals for travel for himself and his appointees. In a country slipping from 1.8% growth in late 2014 to a 2.5% contraction today, there was no one in the finance ministry actually making policy.

Greece’s continued failure to fix its economy is an important part of the Greek crisis. But the Greek government is not the only guilty party and there is some truth to the claims that the debt crisis that Greece is currently enduring is in part the responsibility of its EU partners.

Many in the press fingered excessive and ill-judged lending by Greek banks as a prime cause of the crisis. In fact, Greek banks were some of the soundest institutions in Europe before Greece went into the crisis and Greeks didn’t borrow much. Their total debt (private and corporate) was between a half and a third of that in the UK and the US. It was sovereign debt that was off kilter. And amidst all today’s calls for debt forgiveness, people seem to forget that Greece did enjoy the biggest write-off in global economic history, when the 2012 bailout saw Greek-issued private debt cut by over 50%.

But the 2012 haircut only covered debt held by private creditors (including banks, insurance companies, and pension funds). By 2012, that was less than half the Greek debt—so Greece got a write-off on 50% of its 50%, or just 25% of the total. The IMF, ECB, and EU own the rest. So what about that debt?

Here’s where it gets interesting. Back in 2010, before the haircut, when Greece ran out of money, all of its debt was private and issued under Greek law. At the time, everyone knew that Greece was going to have to be forgiven some of its debt but the then president of the European Bank, Jean-Claude Trichet, would not entertain the idea. Why? Because French and German banks had gorged on Greek debt, and a haircut would mean that they, and the whole EU banking sector, would collapse. So he forced Greece to pretend that its solvency problem was a liquidity problem, and pushed it to substitute official debt for private debt. Effectively, between 2010 and 2012, Greece borrowed from the IMF, ECB, and EU in order to pay the banks that should have assumed the losses. At the same time, he forced Greek banks and pension funds to keep rolling over debt. This is why Greek banks got into trouble – it was not because of too much lending.

What happened was that the EU and taxpayers got dodgy Greek debt to help EU (but non-Greek) banks and hedge funds, which duly made a killing. Then, when Greece eventually got the debt forgiveness in 2012, its official debt to public institutions was excluded. This is the real scandal of the Greek crisis — not the profligacy of Greek individuals, corporates, or banks. The bottom line is that the Greek people are paying a heavy price today both for their government’s failure to restructure in 2010 and for their government’s bailout of French and German banks.

And what about that price? All in all, the current deal is really tough in terms of the fiscal targets; it’s punitive, focused on tax hikes rather than cutting expenditures, and probably makes little macroeconomic sense. Of course, there should be a medium-term program on debt relief – after all, we Greeks do deserve a payback for bailing out all those big German and French banks five years ago.

Yet we have to deal with political reality as it is and on balance the structural changes that the deal calls for represent a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They are reforms that no government in Greece, including Syriza, has attempted, for fear of upsetting powerful vested interests. By forcing the government to remove institutional barriers to competition and innovation the deal will create a sound basis for economic growth and development. If (and that’s a huge if) the politics work out, confidence returns, and people invest again, things could get back on track; the alternative may be a failed state. So, let’s keep a cool head, and not throw the baby out with the bathwater. There’s just too much at stake—for Greece, for the Eurozone, and for the European project more broadly.

How to Think About the Future of Cars

The average American in prime working age drives more than 15 thousand miles a year. For these commuters, the thought of not owning a car is ludicrous. With hours each day spent in transit, it’s no surprise they often obsess over what type of car to own and what routes to work to take.

But despite the prominence of today’s driving culture, disruption has planted its roots firmly in the transportation industry. Innovations in ride-sharing, car-sharing, and long-distance transportation are bringing us closer than ever to a world in which car ownership is a choice—not a requirement.

The businesses attacking this massive market are quickly finding both a variety of customers and enormous access to funding. Companies like Uber and Grabtaxi have quickly become dominant. But even with the emergence of large global players, there is still lots of opportunity for new transportation disrupters to claim new niches in the market.

For potential investors, entrepreneurs, and anyone with an interest in getting where they need to go, the billion dollar question is, “How will this market look after the dust has settled?” Although the market is enormous, some approaches to its revolution are better than others. And developing a thesis on the future of this industry is particularly challenging. To make any sort of prediction here, you need to consider changes in the sharing of transportation infrastructure, the driverless revolution, and the dramatic shift towards electric and hybrid architectures of cars. The impact of any of these trends represents a tidal shift. Thinking through all three simultaneously creates a thought experiment we might not see again for a long time.

It’s easy to foresee that transportation’s future will be be very different than its present. But what will that future look like? To bring it into focus, it’s useful to turn to an orthogonal industry: information technology, specifically cloud computing.

Twenty years ago, the world only had inklings of how the internet would revolutionize IT. When Marc Benioff introduced “Software as a Service,” skeptics emerged from every corner of the industry. It was heresy to claim that large businesses, with highly customized hardware and software solutions, would move their resources into someone else’s data centers. SaaS might be a decent solution for the small businesses who couldn’t afford their own infrastructure—but it was never going to be appealing to those with more complex demands.

We know how this story has played out. Today, cloud isn’t just the preferred delivery model for applications. Instead, cloud permeates everything in information technology. Cloud infrastructure provides a shared, flexible infrastructure for computing and storage resources. There have been almost two decades of innovation in hardware and software since SaaS emerged. Cloud vendors have worked diligently to ensure that all that innovation is available to each of their customers. With years of R&D, there are very few use cases that can’t be replicated relying on rented servers in an Amazon, Salesforce, or Microsoft datacenter with far more flexibility and far less headache.

Transportation seems to be following a very similar path to cloud computing. Renting a ride for point-to-point transportation with a click of a button (Uber), is a lot like renting some capacity within a server for web hosting (Amazon Web Services, or AWS). Today, it’s an absurdist claim to argue we’re near the point where we don’t need to own cars. In a couple of decades, owning a car will be much less critical.

A few factors play into this. First, the world is increasingly urban. 50 years ago, approximately three out of ten people lived in cities across the globe. Today it’s more than five out of ten and growing rapidly. More people in densely located areas means the cost of parking will rise ever higher, discouraging car ownership. At the same time, more people living close to work means it will become easier to manage a commute on public transportation.

Second, we’re getting ever closer to the point where renting is frictionless. The mobile internet is making the process of accessing resources on demand cheap and easy. Adam Smith’s invisible hand is getting a bit of an assist from AT&T, GPS satellites, and a slew of app providers. This ease of access to transportation will only increase once we have a fleet of autonomous vehicles roaming the roads. As the technologies improve, the relative benefits of car ownership will diminish.

It’s true that only a tiny segment of the population truly can view disruptive transportation services as real substitutes for car ownership in today’s market. However, it seems inevitable that innovation will make this option appealing to an ever larger group of people over time. Uber has already showed us glimpses of how this will occur by adding cars of all varieties: cars with car seats, wheelchair accessibility, and SUVs for larger groups. For new parents who couldn’t use the service before, Uber is finally an option. For people who sometimes need a car seat, sometimes need an SUV, and sometimes just want a ride in a sedan, it’s one of the better options.

As with all waves of disruption, cloud transportation vendors have every financial incentive to innovate in ways that allow them to serve more demanding customers over time. There will also be stumbles along the way. We’re seeing some of those as vendors battle regulators over the employment status of drivers. But the advantages of cloud transportation are too large to ignore. Despite stumbles, consumers will continue to seek on-demand transportation. Over time, cloud transportation services will offer solutions that help more and more people minimize car ownership—either by abandoning their cars completely or going from a two-car household to a single-car home.

The cloud computing wars started with a focus on buyers in the small business market who couldn’t afford expensive IT solutions. Cloud transportation started with a focus on urban residents who only owned cars as personal luxuries. Over time, cloud computing added the features and functionality that allowed it to compete in the most complex environments. There is no doubt that innovators in the transportation will follow the same path.

Why Cybersecurity Is So Difficult to Get Right

It seems like hardly a week goes by without news of a data breach at yet another company. And it seems more and more common for breaches to break records in the amount of information stolen. If you’re a company trying to secure your data, where do you start? What should you think about? To answer these questions, I talked to Marc van Zadelhoff, VP of IBM Security, about the current state of cybersecurity and the Ponemon Institute’s 2015 study of cybersecurity around the world, which IBM sponsored.

HBR: Did the study find any new trends in cybersecurity?

Marc van Zadelhoff: We have a large business dedicated to security and so we see even beyond the study, across thousands and thousands of customers that we monitor daily. One of the major things that we’ve seen over the last few years is how breaches are increasingly done by ever-more-sophisticated organized criminals. Forty-five percent of breaches occur because of criminals breaking in, so one of the reasons why the cost of breaches goes up is because we’re seeing more being caused by crime, as opposed to other factors like inadvertent mistakes.

It’s one thing to have a breach because an employee loses a laptop, but more and more of it is organized criminals who are very persistent in their approach. For example, when a criminal is involved, the cost for a breach is typically $170.00 per capita per breach, versus if it’s a system glitch or a human error it’s more like $140.00 a breach. It becomes more expensive because they steal more, they’re more persistent, they’re stealthy, they stick around, they’re harder to detect and harder to get rid of. It’s like a more difficult virus in your body. The best advanced attacks on our organization are just harder to inoculate against, and harder to get out of the system.

I’m surprised that the percentage of breaches caused by attackers isn’t higher. If you read the headlines in the papers, it seems like those are the ones you tend to hear about the most.

If you’re getting breached, there’s an incentive to talk about it as being an attack as opposed to a mistake. So I think that’s why the ones that do get covered a lot in the press are the ones where companies come forward and say, “Somebody spent a lot of time and did a professional job on us.” I think people get a little less vocal when it’s truly a mistake.

What about the breaches caused by mistakes, the ones you don’t hear about as much?

I think that not enough attention is being drawn to the careless exposure of data by internal mistakes—which happens quite often, even when there are no malicious actors prompting it. Aside from the most obvious slip-ups, such as leaving passwords in plain view or failing to report a lost or stolen corporate device, many people today are uploading personal and corporate information into third-party, collaborative platforms without thinking twice about how secure this action might be. While these tools are giving us a wealth of opportunity when it comes to working more efficiently and collaboratively, we have to remember to always be cautious in regards to how we’re using, sharing, and collecting data.

What are cybercriminals usually after? What should companies be protecting?

In general, organized criminals are trying to steal things of high value, and one of the most valuable industries, in terms of cost, is health care. So what you see is that criminals are going after health records because on the black market they can probably sell a health record of a person for about $50. If they only steal credit card data or a social security number, they might be able to sell that on the black market for $1. Or they may steal a health care record not to sell it, but to leverage that information to do a more sophisticated attack on you. They might impersonate a bank, saying, “Hey, I know you’re about to go and get an operation, don’t forget to transfer some money by clicking here,” or whatever. And then you think, “Well, they know I’m having an operation tomorrow, so they must be a legitimate bank.” So the initial crime results in more valuable data leaving the building.

If health care records are worth so much, why do hackers go after anything else?

While health records themselves are worth a lot on the Dark Web, there are other types of high-value data that can be pieced together to be used in sophisticated attacks. These types of information can be used to conduct malicious activities such as social engineering, creating dossiers on high-profile figures (with the end game to disrupt their lives in a malicious way), stealing identities, damaging a corporate brand, and more. Businesses of all types and sizes must seek to understand what types of information they have that would be of most value to hackers, as well as what would be most damaging to their company, employees, and customers if a breach occurs. By taking this first step of defining what is most important and where it resides, organizations can then personalize their security programs to adequately protect their unique “crown jewels.”

The study found that the factor with the highest impact on the per capita cost of a breach is employee training. Is that IT people’s training or the standard security training that everybody gets?

Both. You’ve probably had security training at work, maybe even been tested at the end of that training in terms of remembering things. But you can test people more throughout the year, and you can try to “trick” them. For example, we work with customers to do kind of a phishing attack on employees. It’s a way to see what employees click on in an email. We might send you an email saying, “Hey, I see you’re heading to California next week, click here to confirm your travel.” And we would have figured that out because you posted on Facebook that you’re headed to California. Well, if you click on that, since it’s your company doing it, a prompt will come up and say: “This actually a phishing attack, you should always look at the header and who’s sending it before clicking on anything.” So it’s a way of testing without it actually being an attempted hack.

If you have employees aware and a little bit paranoid, it can make a big difference. And often the more senior employees at an organization are the ones that are just less socially aware, in terms of Facebook and LinkedIn and all these things. They can be quite susceptible to still clicking on things, or assuming that if someone sends you an email and it has a couple of pieces of data that are accurate, that it must be legitimate.

Recent attacks on OPM and a London hedge fund show two different ways that cybersecurity is so difficult right now: First, even the U.S. government isn’t safe from attack, and second, the hedge fund’s CFO was able to be fooled into giving away information over the phone. If you’re a company following those stories, what should you take away from them?

The first takeaway from those breaches would be that today’s cybercrime gangs are brazen and operate with organization and sophistication like that of a well-funded company.

Employees can be seen as the Achilles’ heel of cybersecurity; mistakes by those with access to a company’s systems are the catalyst for 95% of all incidents. It can be as simple as accidentally clicking on a malicious link or failing to question the authenticity of a phone call or banking website. Even organizations with the most robust, forward-thinking security strategies aren’t immune to one lapse in employee judgment.

It’s critical that in addition to a strong technical security defense, companies should continuously educate employees on the dangers of security attacks, ensuring that they know what to look for and how not to fall prey to social engineering. They should continuously review and keep tabs on which employees have access to sensitive data, and ensure access is removed instantly once an individual disassociates with the organization, or changes roles to one that doesn’t require the same level of access.

As you’ve studied security around the world, what are the best practices that companies should be following?

Best practices are, first, having very good analytics and intelligence in place. You need to have probes available to get you information either as the data breach is occurring or afterwards, to be able to understand the damage. Next, having an incident response team that is trained and ready for the scenario of a breach. Like your kids at school practicing fire drills, you practice getting breached so if a breach occurs, you know, OK, she’s going to be in charge, he’s going to be the face to the press, and Larry and Sue are going to call the FBI. Companies that had a response team had an average $12 or $13 less expensive cost of a breach per capita than companies that didn’t.

Third is the use of encryption. If you have encryption layered on your data, maybe they get a user name, the password, maybe they get a social security number, but the health care record is actually encrypted. So they stole $1 worth of data, but they didn’t get the $50 worth of data.

Fourth is employee training. Fifth, all organizations have a business continuity management team. If there’s a tornado or a hurricane, they’re able to help companies stay up and running. Well, having them involved when there’s a breach is a best practice. And then finally, Board-level involvement. For example, say you got breached and went to the marketing department and said: “We need to shut down a particular database with customer data that’s often accessed.” They might look at you and say, well, why? But if you’ve taken the time beforehand to prepare and say, during a breach scenario, here are the things that we’re going to do, that can make a big difference,

And if you’re a company planning your security efforts, what should your goal be? Can you actually defend against getting hacked?

The reality today is that no matter how careful we are, no matter how well we design our strategies or how thoroughly we educate and engage employees, we’re never 100% safe against a cyber-attack. Our best defense is to revamp how we’ve been approaching security, and to move from constantly bombarded, isolated defensive positions to a united, intelligence-driven collaborative front against cybercrime.

We need to begin thinking like the hackers that are so successfully penetrating companies. Hackers use the Dark Web underground network to share data, expertise, and resources. Using collaboration, they’ve formed complex and highly efficient cybercrime rings, from which 80% of malicious campaigns start. The private sector is still largely working in silos, with no visibility as to what attacks are on the horizon until they hit.

To truly fight back as best as we can, we need to collaborate on the same level as hackers, sharing information across industries and organizations to see attacks in real time. Just like a disease epidemic, if we’re able to put the right infrastructure, warnings, and precautions in place before a malicious attack comes to us, chances are that we’ll be much better equipped to spot it and shut it down if it does get into our systems.

B-Schools Aren’t Bothering to Produce HR Experts

A few decades ago, U.S. companies were making progress on the operations front, but now they seem to have lost their way—and business schools are in a position to help set them right again. Let me explain.

In the 1980s, our organizations learned a great deal about how to improve productivity, quality, and costs from Japanese practices. Lean production, which includes a vastly expanded role for front-line workers in addressing problems, was brought to the United States by Toyota in its auto plants but has now spread to health care, professional services, and virtually every other industry. And in the 1990s, our companies began to learn more from innovations at home, particularly in the area of high-performance work systems.

At their heart, such practices were about redefining the role of supervisor—from controlling dictator to empowering coach—to tap into the discretionary effort that employees could produce when they were engaged in their work. There was compelling evidence that they paid off, too: Toyota management took over one of the worst plants in the General Motors system, in Fremont, California, and turned it into the best-performing plant in the U.S. Clearly, well-run operations and careful talent management went hand-in-glove.

But if you look inside most companies today, you see little left of those talent practices. Typically, management is based on a model of formal authority and “hard” incentives: Bosses get bonuses when their units succeed, they get fired when their units fail, and they push employees to hit the numbers in whatever way they see fit. This is actually a repeat of what we’ve seen during previous financial downturns, when line management rejected HR initiatives as unnecessary because it was easy to fill jobs with so many people desperate for work. (For more on how HR’s profile tracks what’s happening in the economy, see my recent HBR article.) What’s different this time is that the practices we’ve pushed aside were so widely documented as being successful. It’s as if businesses have forgotten that they work.

Business schools should do their part to remind them. Understanding HR innovations and figuring out which ones are effective is, sadly, a low priority in the world of scholarship. That would never fly in marketing, operations research, or even accounting, where academics are all over new developments. In most companies, the HR staff is many times larger than the marketing department—yet while all leading B-schools have a marketing department, almost none have any HR-dedicated faculty at all.

The lack of research interest in HR stems partly from carving up the topic into so many subfields. There are separate associations for labor economists, sociologists, and psychologists that look at the same problems, but these specialists don’t seem to be aware of one another’s efforts, let alone work together on solutions to our talent problems.

And solutions face a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem, anyway: If companies were hiring MBA graduates to address HR questions, that would get the attention of business school deans, who allocate where faculty attention and resources go. But MBA programs aren’t actually producing those students. If they were, employers might hire them instead of leaning on their data scientists for insights and context they aren’t equipped to deliver.

So schools need to step up. The State University of New York at Albany is one of the few trying to meet the market, with a program that blends information technology and human resources. Its graduates have been snapped up, especially by consulting companies leading the big-data charge.

Other schools should follow suit if they want to help organizations and leaders thrive.

Samsung Pay’s Older Technology Could Be an Advantage

The stakes are high in the mobile wallet market, projected to be over $140 billion by 2019. Most recently, Samsung has announced that it will roll out a payment system called Samsung Pay later this year and has already begun beta-testing it in Korea. Its foray into this industry comes on the heels of product entries by Google and Apple. But Samsung’s new mobile wallet strategy may be a sign that they are finally becoming a true leader and shedding their image as a fast follower. The irony is that they are embracing an older payment technology to pave the way for new growth, new visibility, and new strategic wiggle room.

Apple was the first mover into mobile payment options with its Apple Pay, introduced to great fanfare in late 2014. Not to be outdone, Google countered with Android Pay, an improvement over the much-maligned Google Wallet. Apple and Google both employ a NFC (Near Field Communication) technology where offline retailers install terminals that consumers can tap with their smartphones to securely pay (process called “tokenization) with preregistered credit cards. Samsung, in contrast, with their LoopPay acquisition, allows consumers the option to use MST (Magnetic Secure Transmission) instead of the NFC infrastructure. This allows people to use the Samsung’s payment system in areas where few of the newer NFC terminals have been installed, giving it a much broader potential market. In addition, Samsung, like Google, will not charge users for paying with their smartphones (Apple’s transaction fee of 0.15% of the purchase amount limits retailers’ adoption of Apple Pay).

The different configuration of Samsung’s pay system signals that this company can be an independent thinker about how they understand the broader mobile industry. The conventional wisdom was that consumers buy smartphones first and then worry about how to make payments with them, either online or off. Samsung Pay is flipping that equation around by looking at the payment environment first and then using the phone to accommodate the usage condition. When we consider how large the physical store market is ($3 trillion in the U.S. alone), that is the proper sequence to think about the overall payment industry.

This venture also allows Samsung to “de-Google” its brand in order to create a more distinctive identity for itself and to set it apart from other Android-based phones. Whereas Apple manages the whole stack of hardware, software, and apps, Google handles only Android and leaves it up to the OEMs and carriers to take care of features and elements of support. At least in terms of pay systems, Samsung is on equal footing with Apple and better than Google in claiming better integration of the value chain. More importantly, instead of being just one of many hard-to-differentiate Androids, Samsung has a golden branding opportunity to break out from the pack and claim payment-related user benefits that are truly unique to them.

Of course, there are some risks looming in the payment market horizon. The most pressing concern may be competition from companies other than device manufacturers. If the unit of analysis is overall payment, then retailers, both online and offline, are gearing up their own payment systems. Even though the payment system CurrentC, developed by a consortium of retailers including Walmart, has not received good reviews, it shows that the major payment players, including Samsung, have to forge alliances with retailers and convince them that they stand to benefit also in the new payment world. (In cases like these, having no transaction fee makes a big difference.)

Samsung will also need to monitor the “mobile only” evolution taking place in consumer purchasing. In developing countries like India or lower tier cities in China where offline retailing is still antiquated and inconvenient, e-commerce via smartphones became the high-growth retail space even before the modernization of retailing. The e-commerce juggernaut Alibaba has also set its sights on the mobile wallet market with Alipay. Even in an industrialized country like Korea, KaKao Talk, a free messenger app that traffics 3 billion messages a day, has come onto the payment scene with KaKao Pay. Both Alipay and KaKao Pay allow interpersonal money transfer, defining “payment” broadly beyond retailing transactions. The social network of these pay players may be a dimension that device-based players like Samsung have to counter by making the offline network bigger, the transaction faster and more secure, or by creating online linkages and benefits.

The mobile wallet market is still in its infancy. Companies coming into it from the device, credit card, retailer, or social network base need to be nimble-minded instead of sticking to their tried-and-true industry practices. Samsung has taken the right first step, but the payoff remains to be seen.

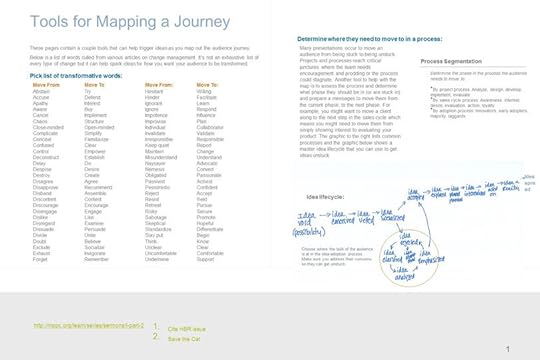

Why I Write in PowerPoint

When writing business documents (aside from emails), most people turn to word-processing software. That’s not the only option. You can do everything — outlines, drafts, revisions, and even layouts, if you’d like — in PowerPoint or similar presentation programs.

That’s what I’ve used to write my books, internal documents, sales collateral, and web copy, for several reasons:

I can brainstorm with abandon. Because PowerPoint is so modular, it allows me to block out major themes (potential sections or chapters) and quickly see if I can generate ample ideas to support them. In early stages, each slide resembles a Pinterest board, with a simple but descriptive title, some rough text, and a few sketched or found images that clarify the concepts. If I can’t produce enough insights for a particular theme, I abandon it before spending too much time crafting language. It’s easy to drag individual slides to the end of the deck, in case I’d like to revisit them later, or just delete them.

Below you can see an excerpt from the PowerPoint draft of my second book, Resonate. Every slide represents a two-page spread. The content is much denser than it would be on a typical slide, but that’s okay because it’s meant to be printed, not projected. And anyway, it’s a work in progress.

This was the idea-generation phase. In addition to the rough text and the bevy of images for inspiration, I included citations and links (in green) at the bottom of each page (the gray area) so I could have ready access to my research.

Here’s one spread, before and after the designer got ahold of it:

I can arrange and rearrange. It’s a struggle for me to begin drafting prose until I’m confident that the structure is sound. Working in slides, as opposed to one long document, helps me focus on organizing before I really begin writing. I think of the slides as index cards or sticky notes that can be arranged and rearranged until I’m sure my thoughts are in the right order. As I write, I can easily toggle back and forth from “Slide View” to “Slide Sorter” to get a sense of the whole and the parts. If I were working in a word processor, I would have to scroll through the entire document to move content around.

I also use color-coding to signal varying levels of completion throughout a deck. Once a slide has a green dot, that means it’s ready to be line-edited.

I can rein in the length. Slides also help me constrain the word count on each page. When writing the HBR Guide to Persuasive Presentations, I set the master font size so I would be limited to about 600 words for each of the 57 tips, to keep them as clear and concise as possible. If my writing extended beyond the bottom of the slide, I knew the tip was too long and would work to tighten it.

I can collaborate easily. Throughout the writing process, I ask for feedback from people I admire. Businesspeople are accustomed to consuming content in slide form, so providing comments on a PowerPoint deck is a natural way to work. Instead of circulating a lengthy draft, I print the deck and post the slides on a wall so others can react to the structure as well as the individual slides. For the first 20 minutes of the meeting, reviewers read through the concepts on the wall and write their feedback on the pages (or on sticky notes); then we discuss impressions and perspectives. In the beginning, my slides are a hot mess, but as I iterate and collaborate, the content gets more and more solid.

On a recent project, my coauthor graciously accommodated this method of thinking and writing, and it worked well. We worked on different sections individually and then recombined them by pasting them back together in Slide Sorter mode. We did have to be careful about version control. When one of us had a section “checked out,” the other couldn’t make changes in it. Google Slides is another option for coauthoring, because you can have multiple people working on slides at the same time. But we intentionally cut ourselves off from the internet for part of the drafting process, so we chose to stick with PowerPoint.

I can design and share the finished document. For printed books, I move out of PowerPoint once I have a solid first pass at the text, because most publishers like to go back-and-forth in Word and do their design in other programs. But for any documents that you edit and design internally, you can publish and distribute your work right in your presentation software. There are huge benefits to doing this — the slides are individual bites of content that can be quickly consumed and easily shared through email and social media. If you’re trying to spread ideas, this is a great format for doing it.

So instead of using PowerPoint purely for presentations, consider it as a tool for creating your next piece of business writing, whether it’s a report, a proposal, an article, or an entire book. It can help you generate, organize, refine, and visualize your ideas in a medium that your colleagues and partners use all the time.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers