Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1268

July 31, 2015

How I Brought Ashley Stewart Back from Bankruptcy

In 2013, Ashley Stewart was on the brink of bankruptcy — its second in a little over three years. Decades of operating losses and rampant turnover in both the employee base and ownership group had cemented a fearful culture. The fast-turning nature of the company’s inventory and the constant specter of insolvency undermined long-term investments and strategic planning. The company did not even have WiFi at its corporate headquarters — a dark, converted warehouse that time had forgotten. The nascent e-commerce effort, viewed suspiciously by most in the company, operated independently on an antiquated platform.

I did not want the company to liquidate. I had been a member of the board since 2011 and loved the brand and everything it stood for. Ashley Stewart had been founded to provide plus-size fashion for women in boutique-like settings in urban neighborhoods across the United States. After listening to our customers, I came to realize that the brand stood for more than that — values like respect, empowerment, and joy. In tightly knit communities, shopping routines are interwoven amongst generations of women, often times around important moments for them like church, family reunions, or a new job interview. In short, I felt Ashley Stewart stood for kindness and embodied community.

To give her a chance, I resigned from the board to become CEO in August 2013. I decided I’d give it six months and my best shot.

On my first day, I confessed to the entire home office and field management team that I was the least qualified person to run the business. After all, as a long-tenured private equity investor and former high school teacher, I had never been an employee of a fashion brand or retailer, let alone held the CEO title. I imagine that this was of small comfort to a fractured company less than three years removed from one bankruptcy and six months away from a second. Things probably only got worse when I concluded my first town hall meeting with a statement that kindness, as the bedrock of innovation and consumer engagement, was a go-forward core strategic pillar.

For the next six months, leading up to our March 2014 bankruptcy filing, we relied on math, changing the company culture, a mission-driven dedication to our core customer, transparent communication, lean processes and — yes — kindness:

Changing the company culture: We knocked down walls to create a more open floor plan, and I immediately shut down the C-suite offices and moved into a cubicle. In July 2014, following our emergence from bankruptcy in April 2014, we moved to a new office, on a shoe-string – basically moving ourselves in U-Hauls. I still do not have an office. I sit at a desk, with no drawers, in the middle of a wide open, trading floor-type space. There is no correlation between seniority and office size – only those who need real quiet to do their jobs get offices. We’ve also gotten rid of most formal job descriptions.

Most of the management team could not adapt to the new professional services-type environment, while others were doomed by our new start-up mentality. Those who could adapt, thrived. In the end, we downsized corporate headcount by 40%.

Operations streamlined around the core customer: With our core customer’s needs foremost in mind, we closed almost 100 stores, renegotiated or rejected close to 150 executory contracts, replatformed the website, outsourced all distribution and virtualized our fleet of servers. We also made sure the algorithms we were using for goods flow and markdown cadence had been derived from close study of, first, our customers’ psyche and emotional tendencies, and, second, their physical shopping behaviors. We did all of this in six months with a skeleton team.

Transparent communication. We outlined in advance each and every step, and we took great care to explain why our decisions were best for Ashley Stewart and her customers. We used SMS, email, and social media to engage directly with our customer, and we had very direct conversations with our field associates. By broadcasting our operational changes this way, we helped engender trust and build a foundation for the open door policy of our new social-first, mobile-delivered customer engagement strategy.

Kindness: Despite our financial plight, we reintroduced a generous local charitable giving program during the 2013 holiday season. We were penniless, frightened, and exhausted, but we knew that our philanthropic efforts were the right thing to do on multiple levels. A picture from our YWCA event in Brooklyn still hangs next to my desk to this day. It reminds me daily of the importance of staying true to core values, a commitment I made to my father, who dedicated his life to the well-being of children.

Today, Ashley Stewart is thriving. Operating profits are at unprecedented levels, organic sales growth is north of 25% and our asset productivity, through the implementation of lean processes, has shot up. Our digital business is booming. Our e-commerce business accounts for roughly one-third of total net sales and it is growing at over an 80% clip. Our mobile metrics are particularly encouraging, with demand growth at 200%+ and demand penetration at well north of 30% of total e-commerce demand. We’re also seeing some of the highest levels of social media engagement amongst all brands. We are one of the largest, most profitable and fastest growing plus-size fashion brands in the world.

My six-month stint is now turning into a two-year anniversary. Looking back, I realize that in some ways, we were blessed with how broken the business model was and how dire the circumstances were. We got the opportunity to rewrite everything from scratch. The bankruptcy process allowed us to re-assess and renegotiate all vendor relationships. We were also lucky, and good — our small team, without the help of a single third-party consultant, executed seamlessly on a well-scripted set of operational changes, any one of which could have ended the company had it gone wrong.

But I still believe that the single biggest contributor to our success has been the fostering of a teaching culture with deep roots in kindness. Kindness enables innovation by creating a safe work environment and it serves as the foundation for our meritocratic, performance-based culture. Kindness also supports our fiduciary-type sensibility towards our customer.

We are a mission-driven business — we believe in advocating for a woman who could sometimes use more advocacy. Everything we do is to serve her. Period. And she has led the way forward for us. She has driven us to become a global leader in social media. She is driving us to explore enhancements to our nascent mobile capabilities. And yet until and unless she cares, we are not concerned in the least about winning a “Store of the Future” award. Indeed, some of our most innovative forms of consumer engagement are laughably old-fashioned, like “sip and shop” events and in-store model searches. We are investing heavily in customer service and employee training, because we believe that’s what she wants. And we will continue to work hard for her and show her the respect she deserves.

July 30, 2015

What Email, IM, and the Phone Are Each Good For

A few weeks ago, I saw an email in my inbox from a member of my sales team. I realized an appropriate response would take more time than I had at that moment. So I skipped it, planning to return to it later. The email quickly got buried, and after a week went by, it was forwarded to me again, with a note: “Wanted to make sure you received this.” This time, I picked up the phone, and after a five-minute discussion, he got what he needed.

We default to email to connect with people – to the tune of 122 business emails, on average, per person per day. And while email is great for recaps, updates, and other informational exchanges, there are many situations where it’s not the best form of communication. In fact, it can slow you down or muddle an important message, such as in the example above.

As the person sending the message, it’s your job to select the right vehicle for what you’re trying to convey or ask. Your colleagues have plenty on their own to-do lists. In order to get the response you need, when you need it, you must make it as easy as possible for the recipient to get back to you—and this is where choosing the right medium makes a difference. To determine whether it is more effective to IM someone, send an email, pick up the phone, or schedule a meeting, ask two questions:

What is the nature of the subject? Is it specific and purely informational? Then an IM or email may be the best route. But if there are complex details and nuances—or if you’re dealing with a sensitive topic—a phone call or quick face-to-face might be more appropriate. And if your message requires input from multiple stakeholders, you’ll likely want to plan a conference call or meeting.

What type of response do you need? There is a major difference between answering, “Will you be joining us for lunch before the team meeting?” and “Can you give me the details about the work we did for the client during Q2?” You want to make it easy for people to respond by choosing the most convenient route. If your request is urgent, how can you help someone respond quickly? Perhaps with an IM. If you’re looking for a more detailed answer, then it might be more useful to get on the phone so they don’t have to craft a long email.

Once you answer these two questions, you’ll know which route is best to get the response you need. The next step is crafting your message in a way that efficiently cues up context and a response. Consider these tips for using popular communication methods more effectively:

IM is efficient. The quickening pace of today’s workplace means it’s often easier to ping someone than to walk over to her desk, especially if the response you need is finite and a quick answer. Of course, office culture also dictates whether or not it is acceptable to message or text someone. Just remember that if you don’t need a response immediately, IM is probably not the best way to reach out. To get the answer you need:

Give a bit of context. Just because the subject is top of mind for you does not mean someone else is thinking about it too. You want to provide just enough context to get you both on the same page: “I’m finalizing the purchase order. What’s the name of our contact at Acme Co.?” “Working on the board slides – how many new hires did we have last year?” “Figuring out transportation – will you be joining us for lunch?”

Stick to three questions or less. Think of IM as a great place to get an immediate answer to keep the ball moving—not as a place to collaborate. If you have more than two follow-up questions, you probably want to pick up the phone.

Handwritten notes feel special. Ideal for an RFP, follow-up to an interview, or a special thanks to team members, old-fashioned notes still have a place in business. And usually no response is expected. They’re useful for getting someone’s attention, gaining a competitive advantage, and connecting on an emotional level. A sticky note that says, “The meeting went great,” might linger longer than an email. Notes can also be surprisingly persuasive and serve as more effective reminders, particularly if you stop to hand-deliver them. But, of course, don’t overdo it. Save handwritten memos for special moments so you don’t clutter people’s desks. Keep in mind:

You have to write legibly. Make your message as readable as possible. This also means keep it brief.

Don’t let lag time hold you back. People resist sending handwritten notes when they want more immediate action. In this case, send the handwritten note as a lead-in. For example, “A proper thank you is on the way…” is a nice way to get, and keep, someone’s attention. (Just be sure it really is.)

Calls can be easier. When you have a lot to say or are dealing with a sensitive topic, a quick chat on the phone or in person is more ideal than volleying emails back and forth. And if you’re engaging multiple people, that’s when you want to schedule a more structured meeting or conference call. To make these run smoothly:

Give people enough time to prepare. Be sure that people have been able to think through a thorough response—and have time to talk. If someone’s on deadline or about to meet a client, you’re better off postponing your conversation.

Give context. You often need to bring people up to speed on the who, what, where, when, and why up front. As opposed to writing, speaking gives you more room to do this.

But if email really is the best option… at least make it more manageable, by forcing yourself to remember to:

Manage your recipients. Put the correct people in the “To” and “CC” lines. If you want to keep people in the loop, but they don’t need to act or respond, CC them. And be careful of “reply all,” which is undoubtedly one of the most abused email functions. Reserve this for when the subject is relevant to everyone on the thread.

Write your subject line as if it will be searched later. It will be. So it helps to include the action needed and the deadline. One of our clients prefaces each subject with IO (Information Only) or AR (Action Required) – for example, “IO: Q1 Town Hall Recap.” You can also change the subject to keep the chain relevant. So if you’re done with Meeting Recap, you can change the subject to “Next step assignments Due by Thursday.”

Lead with the bottom line. Don’t go into all the details without a two-sentence “here’s the deal” executive summary first. If the bottom line is, “I’m not sure what the next step is. Can you review this new proposal before tomorrow at 3pm?” then lead with that. With people reading email on their phones and in between meetings, you want to be sure to cut to the chase.

Keep it short. Long emails can be especially daunting on a smartphone screen. Leave out any fluffy details so your core message doesn’t get lost.

Being able to get your point across most effectively is increasingly necessary in today’s workplace. This means taking responsibility for the way you choose to communicate – in terms of the vehicle with which you are communicating and the words you use. Remember, when it comes to business writing, you’re in charge of getting the response you need from people. If you make it as convenient as possible for them to give it to you, everyone wins.

Question What You “Know” About Strategy

Say you are competing in a fast-growing industry. How much do you care about profits versus market share?

It’s a common rule of thumb that businesses should go for market share in fast-growing industries. It’s conventional wisdom, though, not a law of physics; you don’t have to go for share.

Whether to pursue profits or share is one of the questions posed in I conduct that uses computer simulation to test strategic decision-making among executives, students, and other management enthusiasts. Over 700 people have entered pricing strategies in the tournament.

A good strategy decision gets you what you want, so the tournament asks entrants what they want. That’s where the profits-versus-share question comes in: allocate 100 points between profits and market share as your goal. On average, those 700+ people allocated 55 of their preference points to market share and 45 to profits in the tournament’s “fast growth” industry. That means they clearly, though not unanimously, intended their strategies to gain market share. In the tournament industries with much slower growth, people put markedly more emphasis on profits. That’s just as conventional wisdom would advise.

And yet in over 173 million tournament simulations – every unique combination of the 700+ strategies for the three competitors in the fast-growth industry – the quest for market share led to price wars 90% of the time, subtracting value from the industry. In other words, following the “rule” produced results worse than if the participants had taken naps and done nothing at all.

It’s hardly surprising that tournament strategists would compete ruinously on price, since price was the only lever they could pull. But that’s not the point. The point is that they cut price because they obeyed the common-practice rule of going for market share in fast-growing industries. They made different decisions in the other tournament industries, where growth was slow or negative.

Here’s a law-of-physics rule: there is only, always, exactly 100% market share in any market. That’s why, despite the vigorous price-warring, tournament strategists gained little or no share. (No one gets ahead when everyone moves in the same direction.) What they got, 90% of the time, was mutually assured destruction. The only way to win a price war is to be the only one fighting, and that’s not much of a war.

Knowing that, and knowing that your competitors know that, would you change your preference for profits or market share? Would you challenge the go-for-share rule?

Perhaps you would, perhaps you wouldn’t. Cogent arguments can be made either way. But I hope you now see go-for-share less as a hard-and-fast rule and more as an assumption to be assessed thoughtfully and critically.

Here’s another rule: we must keep our strategy secret from competitors.

When I conduct business war games for companies and when I run other games in workshops on strategic thinking, groups always hide their thinking and strategies from the other groups. I don’t tell them to do that. Real-life collusion is illegal and it’s explicitly forbidden in those games, but nothing (as in real life) prevents groups from signaling or taking action visible to other groups. I’m not saying that they should or shouldn’t do those things. I’m saying that by reflexively hiding they obey a rule that isn’t there. They treat a common practice as an immutable law, and they hold themselves back because they limit their options.

Fortunes are made by noticing such practices and challenging the assumptions behind them. Companies are lost by hardening common practices into shackles.

Fortunately, breaking rules is free. All you need is curiosity, attentiveness, and the courage to challenge conventional wisdom.

Switch mindsets and mentally place yourself outside your company as a dispassionate analyst. Observe the company’s people. What rules are they following?

When you hear advice containing “obviously”, ask the speaker whether that advice is based on evidence. Is the speaker obeying a law of physics or coasting with common practice?

Think of famous rule-breakers. What would they say to your company?

Extra credit: apply all of the above to yourself.

Author’s note: You can enter the Top Pricer Tournament. It’s free and confidential, and you’ll get a report on your strategies’ performance. Please write to TopPricer@decisiontournaments.com.

6 Reasons Marketing Is Moving In-House

A new research report from the Society of Digital Agencies finds that in the past year there has been a dramatic spike in the number of companies who no longer work with outside marketing agencies — 27 percent, up from 13 percent in the previous year. This continues a trend The Association of National Advertisers first reported in 2013.

But these companies aren’t getting rid of marketing – they’re just bringing it in-house. Mitch Joel, president of Mirum, recently has also noticed this movement of agency talent to the client side, calling it one of the most disruptive trends in the industry right now.

SoDA describes this trend as “alarming” (and it is, if you work for an agency) but stops short of fully explaining why it’s happening. After interviewing several ad agency executives and marketing leaders in a diverse group of businesses — pharmaceutical, high-tech, manufacturing, retail, sports, and others — I’ve found a few common themes that could help explain what is going on.

1. Agencies are slow. An executive from one of the world’s largest ad agencies told me that his company was too big – and consequently, too slow — to compete in the lightning-fast digital space.

“We have too many people,” he said, “too many contracts and too many approvals to be able to react and work effectively in a real-time world,” he said. “The work is moving closer to where the customers are, where the responses can be more rapid and connected.”

2. Agencies are stuck on advertising. Agencies have been too slow to adjust to industry fast-changing industry needs.

A brand manager at a Fortune 100 company expressed deep frustration to me: “We want to connect to our customers in a new way. We want to leverage social media, content marketing, and integrated models but every time we ask our agency for a proposal, it comes back as advertising. I’m sick of it. I am ready to break our contract at any cost because they just don’t get it.”

Another brand manager told me that many agencies are creating social spin-offs but they still operate like traditional ad agencies. Perhaps the cultural transitions are not happening fast enough at these agencies.

3. Continuity has become more important than campaigns. There’s a key difference between funding an ad campaign and supporting a social media effort.

In an ad campaign, you make a pitch, win a deal, execute the creative, provide a report and start over. Agencies are generally funded and organized by campaigns.

But in a socially-oriented world, the connection never stops. You fund, staff, and execute continuously. The traditional agency structure, forged over decades, is not necessarily built for that model.

4. Companies no longer want to outsource customer relationships.

As analytics improve and Big Data gives way to the real insights in Little Data, we are able to drive our efforts down to individuals. I believe this is where the real power in marketing is going to be in the near future — focusing like a laser on the most active customers driving our business (what I’ve called the “Alpha Audience” in the The Content Code).

When the primary focus of our marketing finally shifts from mass broadcasting to discrete customer relationships, is that something we really want to send to an outside company? Do we want somebody else to own critical relationships?

5. Companies want to own the data. Marketing activities today generate unprecedented amounts of data.

In the “old days,” we might get a standard report of “impressions” from an agency, but today taming that data to make the numbers behave in surprising new ways needs to be developed as an internal core competency.

Who owns the data? Who owns the algorithms to interpret the data? This must be kept in-house.

6. Are agencies attracting the best digital marketing talent?

I only have a couple of data points on this, so I’m framing it as a question, but I recently had a shocking look into the digital competency at big agencies.

I was brought in to do marketing triage for a large company in Florida. They had already fired two agencies before they hired me. When I was finally an “insider” I was allowed to see the two social media marketing plans that had been provided by the two previous incumbents (both large national agencies).

I was dumbfounded by the total lack of digital marketing understanding these plans demonstrated. They had provided formulaic, cookie-cutter approaches that were unrealistic, out of touch with the strategy, resources, and political realities of the company. The plans were simply destined to fail.

Like I said, this is just one data point, but I was left wondering how these two well-known and respected agencies had provided plans that were so… well… dumb. There’s really no way to sugar-coat it.

One Atlanta agency friend told me, “Agency employees are stretched thin, and their ideas are too. It’s harder to invest in a brand and do a bang up, non-cookie-cutter job for a client when you have 12 other brands on your time sheet. Moving to the client side allows for more opportunity to really invest in one brand and watch it grow.”

The market dynamics and customer needs are rapidly out-pacing the agency model, at least for some traditional tasks. But perhaps this is a healthy trend. Maybe it’s time for companies to be more directly involved with their marketing, more accountable, and more intimately involved with their customers.

Obama’s Former “Body Man” on Being the Ultimate Assistant

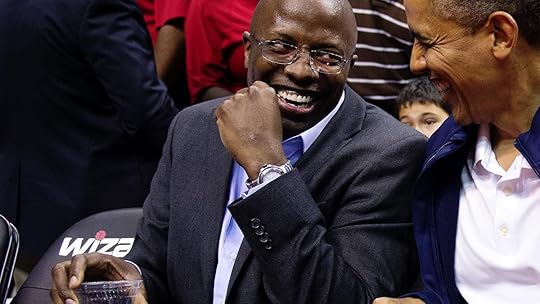

At Duke University, Reggie Love played football and basketball, and after his 2005 graduation he tried out for two NFL teams, without success. He thought about joining an investment banking firm. Instead, in 2006 he took a job in the mail room of Senator Barack Obama, and a few months later became the presidential candidate’s “body man”—the staffer who awakens him each morning and travels at his side, procuring meals and providing support.

After Obama won the 2008 election, Love spent three years as the president’s personal assistant before leaving to earn an MBA at the Wharton School. Earlier this year Love, now 33 and a vice president at RON Transatlantic Advisors, published a memoir—Power Forward: My Presidential Education—about the experience. Love told me how he made the most of a support role. Here’s an edited version of our conversation:

Some young people might have bristled as some of the menial tasks your job required. Why is that the wrong attitude?

I didn’t look at the job as being about me. I looked at it as working for the only African American in the U.S. Senate at the time, someone who was offering hope for the country. Being a small cog on that team was an opportunity, so you do whatever you can to help the team. You carry bags. You wash dishes. You answer mail. Whatever it takes. It’s not really about you and your own trajectory—it’s about the greater good.

To really learn from an assistant role, you need to take advantage of proximity and observation. How did you do that?

There’s no better way to learn than through experience. It’s one thing to read a paper or a case study, or look at cash flows on a spreadsheet. But it’s another thing to see somebody deal with [issues] firsthand, to see how people reason. You can have the greatest ideas in the world, but if you don’t have the ability to understand people and to deal with people, you’ll have no way to know how to implement those ideas or to lead.

In the book you describe a lot of awkward moments before you knew Obama well—having nothing to talk about with him, losing his luggage, bringing him food he didn’t like. Those moments sounded really unpleasant. How did you get through that?

Awkwardness is an interesting phrase. When you’re on a team and you played sports in college, as I did, you’re doing stuff with people all the time. In some scenarios you’re leading. In some scenarios you’re following. For me personally, I didn’t take one specific instance or one moment of awkwardness as a total sum. You have to say “this is a small piece of a bigger puzzle.” You have to have a good attitude, and recognize that things aren’t always going to be perfect.

Early on, you decided not to talk politics with him, and over time that helped you develop an easy camaraderie focused on your shared interest in sports. Why did you take that tack?

I was 23 when I started working for him. What was I going to advise him on? When there was something he couldn’t do or didn’t understand, he’d ask me, and I’d give my take. Sometimes you can give advice to people and they don’t even know it’s advice. If you spend your time trying to convince someone what you want to do is the right thing, you’re not always going to have a great success rate. Sometimes the best way to be an advisor is to ask good, thoughtful questions, to show you’re paying attention, to show you understand.

A lot of people look at an assistant job as a starting point, but you didn’t seem to be angling for promotions. Why not?

Everything doesn’t have to be linear. Just because you don’t move up today doesn’t mean you can’t move up a few years from now. Also, one of the challenges of being 23 and going to work for someone is that when you’re that young, people tend to always see you as that 23 year old, even once you’re 30. That’s partially the reason I went to get my MBA.

CEOs typically don’t have a “body man,” but Amazon and other companies do run programs in which high-potential managers spend a year as an assistant to the CEO. Should more companies look at these jobs as developmental roles?

My assumption is if you’re hiring someone who’s going to work for your company, it’s always developmental … [But] I don’t know how easy it is to recreate the job I had, because in a normal job you don’t spend that much time with anyone else. Even in very competitive workplaces, you might work 7 am to 9 pm, but people typically have dinner on their own, they wake up on their own, they have weekends off.

How are you using what you learned as an assistant in your career today?

I learned that it’s really important to build great relationships with people who are in a support role to a principal, and that the thing that makes an opportunity [like the one I had] successful is trust. You need to trust that the person has the know-how and perception to act, and to represent their boss, when dealing with other employees or other businesses. Trust is what lets you sleep well at night—it’s really invaluable.

July 29, 2015

Create a Conversation, Not a Presentation

Nicholas Blechman

When I worked as a consultant, I was perennially guilty of “the great unveil” in presentations—that tendency to want to save key findings for the last moment and then reveal them, expecting a satisfying moment of awe. My team and I would work tirelessly to drive to the right answer to an organization’s problem. We’d craft an intricate presentation, perfecting it right up until minutes or hours before a client meeting, and then we’d triumphantly enter the room with a thick stack of hard copy PowerPoint slides, often still warm from the printer.

But no matter how perfect our presentation looked on the surface, we regularly came across major issues when we were in the room. These one-sided expositions frequently led to anemic conversations. And this hurt our effectiveness as a team and as colleagues and advisers to our clients.

The last-minute nature of the unveiling meant that our clients (or internal teammates to whom we were presenting) did not have time to fully understand the information and were not prepared to participate in discussion. This made our problem-solving, and consequently, our solutions worse. Group intelligence typically trumps individual intelligence, and the insights our clients and teammates could have added with further reflection would have improved our results tremendously.

The great unveil—particularly when unaccompanied by careful pre-discussions with the members of the client team—would also lead us to make interpersonal and organizational mistakes. Team members, seeing a controversial solution for the first time, would become defensive. We’d miss problems, or solutions that had already been tried and failed, and if someone brought these up in the middle of our presentation, we’d end up distracted and confused.

When we created a perfect solution in isolation and made it “ours” to present, we ignored the fact that each individual needed to arrive at the conclusions independently to really understand it, to believe in it, and to be willing to work hard to execute it.

And frankly, relying entirely on the presentation made for boring meetings. No one wants to sit and listen to another person present for hours on end. People want to ask questions and to provide their own insights. They want to problem-solve and debate.

We’re all familiar with these issues, and yet the tendency toward “the great unveil” presentation style persists. If we want to foster conversations rather than presentations, what are some effective ways to do so?

First, draft the materials in careful partnership with important members of the audience. Often the best way to start problem-solving is simply to have an initial discussion with everyone involved and get their thoughts on the issues and potential outcomes in play. This helps surface the broadest array of topics and allows everyone to feel heard and included. Then, as the problem-solving evolves, work with these team members consistently at key checkpoints to review the latest information and get their thoughts. Keep them informed throughout the process so that at the end of it, there are no surprises in the room.

Second, design a presentation that invites insight and discussion. For most meetings, you want presentations that have enough detail to be read and understood in advance. You want to include key insights on most pages, along with call-out questions for discussion to keep readers thinking critically about the issues in play. Finally, use “punchline first” communication. If you start the presentation with an executive summary that lists key conclusions, your counterparts can keep those conclusions in mind, testing them as they encounter the more in-depth information throughout the presentation.

Third, send the “final” materials well in advance of any group discussion and require a pre-read. If you show up to the meeting with a warm deck that no one has seen, most thoughtful people will spend their time in the meeting trying to read and absorb it, even if you’re describing the material in detail in person. This is particularly true of introverts and others who prefer time to absorb information before speaking about it and drawing their own conclusions. Requiring a pre-read and offering a few days over which to accomplish it guarantees that everyone has an opportunity to fully consider a presentation in advance of the meeting.

Fourth, avoid marching through any document page-by-page, and disperse responsibility for leading components of the discussion. If everyone has prepared, they will be more informed—but they’ll also disengage if you then try to painstakingly read every word. The best approach is to appoint someone to facilitate the conversation, then have that person or others discuss the executive summary, any crucial ideas within the text, and open the dialogue. The presentation or document you’ve routed then becomes a reference for points of conversation. This works even better when several people help introduce the key facts rather than one lone presenter—establishing the environment for inclusive discussion.

Finally, appoint facilitators to draw out comments and questions from the whole group. If one or two people are primarily responsible for the project or viewed as the senior people or leaders in the room, have them ask questions of the group and assure that everyone’s voice is heard. This can be formulaic by surveying each person about key conclusions one-by-one, or with adept facilitators, it can be more free-flowing, drawing out opinions from various people as the conversation develops.

Communication between groups of people is most effective when participants are engaged, and the discussion is both inclusive and collaborative. Creating an ethos of conversation, rather than a one-sided presentation, for critical discussions can better leverage the collective intelligence of the team, make solutions to organizational problems better and more comprehensive, and improve ownership for execution of ideas.

What the Auto Industry Can Learn from Cloud Computing

Transportation is one of the world’s largest industries. The five largest automotive companies in the world generate more than 750 billion euro in annual revenue. The names in the industry are global brands – BMW, Ford, Daimler. Yet despite its size and stature, it’s also an industry in the midst of transformation. Today, new transportation vendors like Uber, Lyft, Zipcar, and Grabtaxi are changing our relationship with cars.

Few other industries with such a pervasive and tangible impact on each of our lives have gone through recent periods of similar upheaval. Information technology, however, is one of those industries. We all interact with computers on a near daily basis, and like cars today, the IT industry has been undergoing its own transformation over the past 15 years.

Some of the same factors that have driven the transformation in IT help point the way toward the future of transportation. Namely, four themes from the growth of cloud computing help us understand why a shift to “cloud transportation” is underway.

1. Renting is almost always cheaper than owning.

Historically, renting infrastructure has been relatively expensive. Any renter needed to both cover the profit offered to rental companies and settle for less customized infrastructure. That changed in the world of computing over the last decade – mostly due to the sheer growth in consumers of IT infrastructure.

Today’s cloud IT vendors have both the buying power and the operational discipline to minimize the cost to the customer of a unit of data storage or computing power. With the addition of self-service infrastructure, powered by scalable web interfaces, the cloud IT vendors are also able to provide incredible variety to their customers without dramatically increasing their costs.

The same shift can be anticipated in transportation. Huge vendors of cloud transportation — just like their counterparts in IT — have every incentive to optimize their fleets against cost per mile driven. Unlike the average consumer, cloud transportation vendors will attempt to ensure they (or their drivers) buy the most efficient cars per mile, service them optimally, and retire them on the best schedules. (Ever wonder why Hertz doesn’t have many cars with more than 30,000 miles?)

It may be a long time before cloud transportation companies offer anywhere near the same variety that ownership can confer. But for many of us, what they offer will be good enough. And when it is, we should expect renting to become cheaper than owning.

2. Network effects will be critical to performance.

In a world of cloud infrastructure (whether in software or transportation), there are a number of advantages to scale. Beyond purchasing power, scale helps companies establish strong network effects. In software, these network effects help draw new developers and consumers to a given platform, simplify application deployment and service, and streamline the act of finding relevant talent.

In transportation, networks create value in a couple of ways. The first is convenience. The more Zipcars in your city, the more compelling it is for people to sign up for Zipcar, and the more Zipcar locations can be supported. Similarly, the more Uber drivers there are in a city, the more likely people are to sign up for Uber, and the more likely drivers are to opt into it.

A dense network also limits transaction costs. Every mile driven by a ride-sharing driver with no customer in the seat is a mile of costs that need to be covered. But once a ride-sharing company has built meaningful network density, a driver might leave you on one corner and pick up his next rider only a block down the road.

In cloud computing, we’ve seen these network effects help solidify the position of massive players – locking new entrants out of the market. In the world of transportation, this is definitely a possibility and one of the primary reasons so many next generation companies are trying to expand so quickly.

3. Most of the old guard will struggle to adapt.

As is the case with most waves of disruption, suppliers trying to make the shift to cloud business models will struggle to adapt.

Why? Mainly because the most valuable customers in their portfolio today aren’t necessarily the most valuable customers in the new world. Today, car companies might treasure the luxury customer willing to pay for a highly customized interior. Tomorrow, the best segment to own might be the B2B buyers who are buying at massive scale. Unfortunately, these new buyers have different needs entirely. They’ll care about extremely minute efficiency gains that even the pickiest individual buyers wouldn’t even notice. They’ll look for cars that cost little to maintain, get great gas mileage, and last forever. And in a world with driverless transportation, they may want cars with very different service models, layouts, and architectures.

The theory of disruption would suggest that, for these reasons, traditional automakers will struggle to make the shift, even armed with the massive scale and brand advantages they have today.

4. Change will be slow, and edge cases will persist for decades.

If the cloud revolution in information technology has taught us anything, it’s that edge cases will persist for decades. Despite the known advantages of cloud computing, we’re far from a world where cloud can do everything. But for the vast majority of companies, cloud is a godsend.

Transportation will follow a similar path. We’re a long way from being able to serve many suburban and rural areas with next-generation infrastructure. Genuine car enthusiasts might never make the shift. And there is nothing in place today to help address the edge needs of those doing things like hauling junk, transporting construction tools, or moving people long distances on a regular basis.

Beyond the purely functional limitations of the technology, regulatory issues will persist for decades. We’re seeing the beginning of these issues arise with the questions surrounding the employment status of Uber and Lyft’s contract employees. We’ll only see more of these issues over time. Regulatory issues haven’t slowed cloud computing all that much — but then, data security seems almost insignificant when compared to the physical safety of our loved ones and children. Background checks and security screening issues will be ever more critical in a world of transportation marketplaces. Adapting rules, testing product, and creating the software to enable driverless cars will take quite some time.

But just like with cloud IT, even if we don’t see everyone move en masse, the change will be noticeable. And it will be noticeable soon. Within years, we’ll have trends that point the way toward a very different future.

A decade ago, it was clear to a lot of thoughtful folks that cloud software was going to be the clear choice of the future. Today, the same theme seems to hold for transportation. We should assume that cost advantages will favor the cloud vendors, that scale will improve performance, that the old guard will have to adapt to flourish in the new world, that the edge cases will slowly fill in, and that the change is coming — eventually.

Stop Trying to Please Everyone

Many of us are familiar with the concept of Getting to Yes, an iconic negotiation strategy developed by Harvard professor Roger Fisher and others. For many managers, however, the more difficult day-to-day challenge is “getting to no” which is what we call the process for agreeing on what not to do.

“Getting to no” is a classic management issue because the vast majority of us tend to accept requests and assignments without first filtering them by what’s possible, what’s urgent, and what’s less of a priority. In an age when we are encouraged to be “team players” and responsive to colleagues, it may seem counter-intuitive or even selfish to encourage managers to say no more often, but that is exactly what many need to do. While saying yes to every assignment may initially please senior execs, it usually leaves people over-stressed and inundated with work — a lot of which ends up half-finished or forgotten. In the long run, no one is happy.

In one media company that we worked with, for example, the senior executive team developed a three-year strategy for getting ahead of the increasingly digital and socially driven media environment. They assigned different pieces of it to middle managers who had relevant knowledge, experience, and organizational responsibility. Given the importance of this work, all of these managers accepted their assignments. But since they didn’t drop anything else from their plates, the entire strategic endeavor was akin to an after-school elective – something that had to be worked on once all of the regular work was completed – and not much was actually accomplished.

Similarly, a technology firm hired a new president for one of its regions to jump-start local sales growth. Once she arrived, a dozen different leaders, from marketing to IT to R&D, invited her to meet with their teams. Meanwhile, the CEO kept asking her to come back to headquarters to update the corporate leadership team. After six months of saying yes to every meeting, the constant travel had begun to take its toll. She had a much better understanding of the company, but she had made no progress at all on the growth objective.

In both of these companies, the managers were setting themselves up for failure by trying to over-please. In the media company, nobody was going to refuse a key strategic assignment, especially with board and senior executive involvement; yet there was no way to actually accomplish these projects without stopping lots of other work. A more productive approach might have been for one or more of the overloaded middle managers to cut through the conspiracy of silence by organizing a meeting with the head of strategy, the CEO, and other senior executives. As a group, they could have talked about the common dilemma they all were facing and considered either taking something off of their plates or changing timelines.

In the technology firm, the new president wanted to please all of her constituents, so she filled her first six months with meetings, leaving no time to address her most significant challenge. As an alternative, she might have established a “calendar budget” for herself from the beginning – with a commitment to spend only a certain amount of time away from the region, and a focused amount of time on the growth challenge. Then she would have had a good rationale for postponing some of the “get to know you” trips and meetings until she had a solid plan for addressing her most significant business issues.

What’s worth remembering is that learning how to “get to no” is critical for both your success and your company’s. Organizational effectiveness requires tradeoffs. Managers are responsible for addressing which ones to make when new assignments are doled out. They are not responsible for pleasing everyone. For example, if a new strategic project becomes top priority, managers need to ask what tradeoff should be made to accommodate it. And it’s important to engage in these dialogues regularly.

The other key lesson is to remember is that it’s okay to raise questions and push back on assignments and requests, even if it feels somewhat scary to do, such as when you’re answering to powerful people. For example, you could ask senior leaders whether a new assignment takes precedence over some other project that’s already on your plate, and if so, how should you let people know about the change of timing and shift of resources. You also could ask how the new project fits with the broader strategy and the organization’s priorities. And you can team up with colleagues to pose these questions. Senior leaders may not have thought every scenario through, so raising them likely won’t be viewed as insubordination or trying to get out of extra work, but rather a constructive approach to exploring what needs to be done.

Sure it’s easier to just say “yes” in the short-term; but taking on an assignment that you don’t have the bandwidth for, or ones that will compromise other key goals, won’t make anyone feel good about you in the long run — and it won’t help your organization achieve its goals. That’s why “getting to no” is such a critical challenge to master.

Improve Your Writing to Improve Your Credibility

People jump to all kinds of conclusions about you when they read documents you have written. They decide, for instance, how smart, how creative, how well organized, how trustworthy, and how considerate you are. And once they have made up their minds, it is hard to get them to see you differently. Research in social psychology shows how sticky early impressions are. It takes serious work on the receiving end to undo them — work that your colleagues, customers, and partners may not have time (or feel motivated) to do.

In my editorial career, I’ve met hundreds of writers. Sometimes I can see that the person has more to offer than the prose would suggest, and the disconnect leads me to judge, uncharitably, that he or she has not tried hard to write well or does not know how.

All you can be is you, of course, and nobody is perfect. But if you want to be as impressive in writing as you are in person, may I suggest:

Give your audience the benefit of the doubt. Don’t waste everyone’s time explaining or, worse, repeating what your readers already know.

Help readers trust you by not being full of yourself. If you need to have this suggestion explained, ask someone whose opinion you value whether you seem full of yourself and take it from there.

Also help readers trust you by obsessing about your credibility. You know how to be credible in person: Be charming and forthright, tell the truth, and present solid evidence and logic. If obsessing doesn’t come naturally to you, delegate someone to do it for you, checking your facts, the clarity of the relationships between facts, your spelling and grammar, and your tone. Even if you are obsessive, you may want to find a colleague or friend you can rely on to be your first critical reader and help you be your best self in writing.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Better Business Writing

Communication Book

Bryan A. Garner

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When you’ve finished drafting your document, set it aside for as long as you can. It’s a good idea to build a resting period into your timeline for a writing project. When you pick it up again, try to approach it as someone else — a skeptical reader coming to it fresh. How do you feel about what the document says, and how do you feel about the writer?

Now here are some specific things that I think cast a writer in an unflattering light:

Loading up documents with pairs or with sets of three. Supple thinkers avoid sentences like this: “The policies and practices of businesses and nonprofits can be expected to change over time and distance.” They see more varied numbers of possibilities, and their writing reflects that.

Inventing names or acronyms for things. When writers make up terms, they look pompous, not smart. (“We call this paradigm for developing talent internally ‘talent infrastructure optimization,’ or TIO.”)

Using scare quotes. People seem sniffy when they put normal, talky language inside quotation marks. (“Managers who find themselves ‘behind the eight ball’ may need to be more proactive.”) Either use talky language straightforwardly or find another way to say what you mean.

Changing the order in which things are presented. It’s confusing to read a document that refers to A, B, and C; discusses them more fully in the order of A, C, and B; and then reminds readers of the discussion by mentioning C, A, and B. The writer comes across as poorly organized and inconsiderate of readers’ time.

Using nonparallel bullet points. Let’s say three of four are complete sentences and one is only a phrase. That’s sloppy. You’re allowed to draft things like that — we’re all sloppy on first pass. But you, the writer, are supposed to notice your own inconsistencies and correct them.

Repeating words with no good reason. Writers seem inattentive when they have a lot of empty echoes in their documents. (“It is important to prepare important documents carefully.”) Repetition can add emphasis, but only if it is used with care.

Teeing up lists or paragraphs inaccurately. Writers further seem inattentive when they lead into a series of bullet points or a new section by promising something different from what they deliver.

Writing well is a learned skill; it isn’t the same as being a considerate, interesting, admirable person. But if you do your best to be considerate and interesting and admirable — or whatever else particularly matters to you — no doubt you will have an advantage in the writing department over the thoughtless, the dull, and the contemptible.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers