Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1272

July 20, 2015

Managers Are More Connected, But Not For The Better

Managing does not change, not fundamentally. It is a practice, rooted in art and craft, not a science or a profession, based mainly on analysis. The subject matter of managing certainly changes, all the time, as do the styles that some managers favor, but not the basic practice.

There is, however, one evident change in recent times that is influencing the practice of managing: the digital technologies which over the past two decades have dramatically increased speed and volume in the transmission of information. Have their impacts on managing been likewise dramatic?

My answer is yes and no. No, because these technologies mainly reinforce the very characteristics that have long prevailed in managerial work. But yes, because this very fact may mean that the practice of managing is being driven over the edge.

What are these characteristics of managing? As I discuss in Simply Managing (and also observed long ago in The Nature of Managerial Work), managing is hectic: it is fast-paced, high-pressured, and frequently interrupted. In the words of one chief executive, managing is “one damn thing after another.” This is an action-oriented job. It is also significantly communicative: managers do a lot of talking and listening. Traditionally this has meant the job is mostly oral. And managing has generally been lateral as well as hierarchical: research has found that managers spend at least as much time with people outside their units as with those inside. Observe some managers as I did for the recent book (from a head nurse to a corporate CEO, in settings from a bank to a refugee camp), and you will likely see pretty much all of this. Does this suggest that there is a lot of bad managing out there? Not at all. It describes normal managing—inevitable managing.

Now let’s enter the digital age: how does it affect these characteristics of managing? Niels Bohr reportedly quipped that “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.” So let’s focus on the present, and the innovations in communications technology that managers have been most eager to embrace, particularly e-mail.

One thing seems certain: the ability to be in communication instantly with people anywhere increases the pace and pressure of managing, and likely the interruptions as well. But don’t be fooled. I found in my original research, long before anyone heard a machine say “you’ve got mail!”, that many managers choose to be interrupted. Digital communications bolster this. No one forces any manager to check messages the moment they arrive. And how many require the immediate replies they get? One CEO told an interviewer: “You can never escape. You can’t go anywhere to contemplate, or think.” But of course you can. You can go anywhere you please.

Internet connectivity has not reduced managers’ orientation to action – and their disinclination to engage in reflection. Quite the contrary: everything has to be fast, fast, now, now. How ironic that heavier reliance on information technology, technically removed from the action (picture the manager facing a screen), would exacerbate the action orientation of managing. With all those electrons flying about, the hyperactivity gets worse, not better. (Check your messages Sunday night; your boss has probably called a meeting for Monday morning.)

Of course, more time gazing at the screen and tapping away at the keyboard means less time spent talking and listening. There are only so many hours in every day. But text-based vehicles like e-mail are thin – limited to the poverty of words alone. There is no tone of voice to hear, no gestures to see, no presence to feel. Managing can be about interpreting and using these as much as it is about the comprehension of content. On the telephone, people laugh, interrupt, grunt; in meetings, they nod in agreement or nod off in distraction. Effective managers pick up on such clues. With e-mail, you don’t quite know how someone has reacted until the reply comes back, and even then you cannot be sure if the words were carefully chosen or sent in haste. I once met a senior governmental official who boasted that he kept in touch with his staff by e-mail early every morning. In touch with a keyboard perhaps, but his staff?

Finally, digital communications technologies, and in particular social media, push the lateral tendencies of managing further by making it easier to establish new contacts and keep “in touch” with existing ones. It has always been true that the people who report to a manager are few and fixed compared with that manager’s network of external contacts. Today, thanks to these media, it is exponentially more true. And so managers’ own reports may be getting less of their time—in quality as well as quantity.

As usual, the devil of these technologies can be found in the details. Changes of degree can have profound effects, amounting to changes of kind. When hectic becomes frenetic, managers lose it and become a menace to what is around them. The internet, by giving the illusion of control, may in fact be robbing many managers of control over their own work.

The characteristics of managing described at the outset are normal only within limits. Exceed them, and the practice of management can become dysfunctional. Put differently, this digital age may be driving much management practice over the edge, making it too remote and too superficial.

Perhaps the ultimately connected manager has become disconnected from what matters. Might therefore the new technologies be destroying the practice of managing itself, and thus impoverishing our organizations, and societies? We don’t yet know—there is more inclination to glorify new technologies than to investigate them. But look around you—at a colleague who burned out, at a boss who drives everyone crazy, at yourself and the kids you may rarely see. And then consider this: are these tools augmenting our best qualities or our worst? Each of us, manager or not, can be mesmerized by them, and so let them manage us. Or we can understand their dangers as well as their delights, and so manage them.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

How Startup “Joiners” Are (and Aren’t) Like Founders

Would you rather receive $1,000, or have a 50% chance at receiving $2,000? Most people are risk averse and would prefer the definite thousand, but entrepreneurs are more likely to be tempted by a shot at the bigger prize.

A long line of research has documented the preferences of entrepreneurs: they take more risks, place more importance on autonomy, and tend to be overconfident. But what about the people who join startups? Are they after the same things as founders?

A paper published earlier this year provides insight into what makes “joiners” tick. In terms of things like risk-taking, they’re sort of hybrids between founders and traditional employees. But in the type of work they want to do they differ sharply from entrepreneurs. For anyone running a startup, understanding the joiner mentality is essential.

Michael Roach of Cornell and Henry Sauermann of the Georgia Institute of Technology surveyed over 4,000 U.S. PhD candidates from top universities, and asked them about their interest in joining or founding a startup, working at an established firm, or staying in academia. (PhD students are of particular interest for entrepreneurship researchers because they’re disproportionately likely to be involved in the founding of high-growth firms in science and technology.)

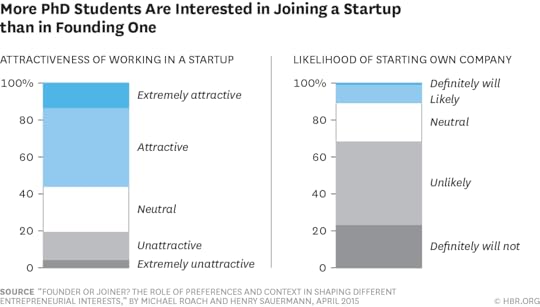

The first thing to know about joiners is that they’re far more common than founders. Although the majority of those surveyed said that working at a startup was an attractive option, most said they were unlikely to start their own company.

In terms of desire for autonomy at work and preference for taking risks, those who were drawn to joining a startup but not founding one scored in between those interested in founding a company and those interested in joining an established firm. That’s as you might expect; joining a young firm can be very risky, but not as risky as starting one from scratch.

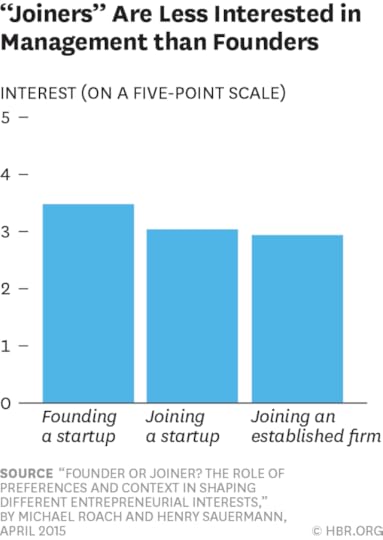

The researchers also asked about the sort of work the PhD students were interested in doing. Those most interested in founding a company were far more likely than joiners to express an interest in management. (Joiners were slightly more likely to be interested in management than those most interested in working for an established firm.)

The same thing was true when survey respondents were asked about their interest in “activities that commercialize research results into products or services.” Founders were most interested, followed by joiners and then those interested in established firms.

But when asked about their interest in “conducting research that contributes fundamental insights or theories” joiners scored higher than both founders and those interested in established firms. For PhD students, this means doing “basic research,” but you could imagine corollaries for other fields.

“Joiners are individuals who are drawn toward startups because they offer greater autonomy and more exciting work activities relative to large firms,” says Roach, “but joiners are more interested in technical or functional work activities rather than in managing and building the company. In other words, they want to be part of the entrepreneurial process, but they don’t necessarily want to be ‘the boss.’”

Think of the brilliant software engineer who hops from startup to startup but never founds her own. She may not care about being in charge, or about the latest sales figures. She’s animated by the work itself, solving difficult technical challenges for the satisfaction it brings.

The researchers also looked at the impact of culture and norms on entrepreneurial interest. The PhD’s were asked if their advisors had ever founded a company or whether others in their lab had been encouraged to work for startups. If a person has an entrepreneurial role model, or comes from a culture where entrepreneurship is encouraged, you might expect they would be more likely to found or join a startup.

But the researchers found no link between these cultural factors and interest in becoming a founder, after accounting for the entrepreneurial preferences like risk-taking discussed above. However, they did discover a link between culture and desire to join a startup. As the researchers write, “individuals who lack [entrepreneurial] preferences but are exposed to norms that encourage entrepreneurship are more likely to have a joiner interest, suggesting that norms may shape interests in joining a startup as an employee.”

If that’s true, encouraging more people to join startups may be easier than encouraging more people to found them. Lionizing entrepreneurs may have a limited impact on the number of companies founded, if interest in founding a company is mostly determined by preferences. But it could have a meaningful impact on the number of people who seek out a job at a startup. In fact, joiners might be the ones most affected by the growing effort to train more entrepreneurs.

The researchers caution that not everyone who applies to work for an early stage startup necessarily has the personality of a “joiner,” and they argue that founders ought to consider this when they hire. Rather than focusing just on ability, Roach says founders should look for candidates who have entrepreneurial traits, since they’ll be more likely to stick around, and may even be willing to work for less because they value the startup work environment.

Sauermann notes that potential acquirers need to understand the joiner mentality as well. “If a large firm buys a startup for its employees… they need to keep in mind that those startup employees may specifically want to work in the startup setting rather than a large firm,” he says. “So it wouldn’t be surprising to see many of the new employees leave once the startup gets folded into the larger organization.”

There’s one other statistic worth relating. As one of their control variables, the researchers measured overconfidence, by comparing survey respondents’ assessments of their own abilities to more “objective” measures like publications and awards. Not surprisingly, those interested in founding a company scored dramatically higher than the rest. Those most interested in joining a startup weren’t nearly as overconfident as founders. But they still scored higher than every other group.

7 Things Leaders Do to Help People Change

Ever tried to change anyone’s behavior at work? It can be extremely frustrating. So often the effort produces an opposite result: rupturing the relationship, diminishing job performance, or causing the person to dig in their heels. Still, some approaches clearly work better than others.

We reviewed a dataset of 2,852 direct reports of 559 leaders. The direct reports rated their managers on 49 behaviors and also assessed the leaders on their effectiveness at leading change – specifically, the managers’ ability to influence others to move in the direction the organization wanted to go. We then analyzed those who had the highest and lowest ratings on their ability to lead change, and compared that with the other behaviors we’d measured.

We found that some behaviors were less helpful in changing others. We found two that had little to no impact, thereby providing useful guidance on what not to do:

Being nice. Sorry, but nice guys finish last in the change game. It might be easier if all it took to bring about change was to have a warm, positive relationship with others. But that isn’t the case.

Giving others incessant requests, suggestions, and advice. This is commonly called nagging. For most recipients this is highly annoying and only serves to irritate them rather than change them. (This is the approach many tend to adopt first, despite its lack of success.)

We then analyzed the behaviors that did correlate with an exceptional ability to drive change. We found eight that really help other people to change. Here they are, in order from most to least important:

1. Inspiring others. There are two common approaches that most of us default to when trying to motivate others to change. Broadly, we could label them “Push” and “Pull.” Some people intuitively push others, forcefully telling them they need to change, providing frequent reminders and sometimes following these steps with a warning about consequences if they don’t change. This is the classic “hand in your back” approach to motivating change. (We noted earlier that classic “Push” doesn’t work well.)

The alternative approach is “Pull,” which we can employ in a variety of ways. These include working with the individual to set an aspirational goal, exploring alternative avenues to reach an objective, and seeking other’s ideas for the best methods to use going forward. This approach works best when you begin by identifying what the other person wants to achieve and making the link between that goal and the change you’re proposing. Inspiring leaders understand the need for making an emotional connection with colleagues. They want to provoke a sense of desire rather than fear. Another approach in many work situations is to make a compelling, rational connection with the individual in which we explain the logic for the change we want them to make.

2. Noticing problems. Lots of management advice focuses on the need for individuals to become better problem solvers; but there is an important step that comes even earlier. It is the ability to recognize problems (to see situations where change is needed and to anticipate potential snares in advance).

For example, in one company we worked with, it was common to hear people being praised for their heroic crisis management skills – rescuing projects on the brink of failure, or getting a delayed product to a client just in time. A new manager recognized this pattern as a serious problem. She correctly saw it not as a sign of hard work, but as a symptom of a broken process.

3. Providing a clear goal. The farmer attempting to plow straight furrows selects a point in the distance and then constantly aims in that direction. Change initiatives work best when everyone’s sight is fixed on the same goal. Therefore, the most productive discussions about any change being proposed are those that start with the strategy that it serves.

4. Challenging standard approaches. Successful change efforts often require leaders to challenge standard approaches and find ways to maneuver around old practices and policies – even sacred cows. Leaders who excel at driving change will challenge even the rules that seem carved in stone.

5. Building trust in your judgment. This is both about actually improving your judgment, and improving others’ perceptions of it. Good leaders make decisions carefully after collecting data from multiple sources and seeking opinions from those whom they know will have differing views. They recognize that asking others for advice is evidence of their confidence and strength, not a sign of weakness. Because of their ability to build trust in the decisions they make, their ability to change the organization skyrockets. If others do not trust your judgment it will be difficult to get them to make the changes you want them to make.

6. Having courage. Aristotle said, “You will never do anything in this world without courage. It is the greatest quality of the mind next to honor.” Indeed, every initiative you begin as a leader, every new hire you make, every change in process you implement, every new product idea you pursue, every reorganization you implement, every speech you deliver, every conversation in which you give difficult feedback to a colleague, and every investment in a new piece of equipment requires courage. The need for courage covers many realms.

We sometimes hear people say, “Oh, I’m not comfortable doing that.” Our observation is that a great deal of what leaders do, and especially their change efforts, demands willingness to live in discomfort.

7. Making change a top priority. One of Newton’s Laws of Thermodynamics was that a body at rest tends to stay at rest. Slowing down, stopping, and staying at rest does not require effort. It happens very naturally. Many change efforts are not successful because they become one of a hundred priorities. To make a change effort successful you need to clear away the competing priorities and shine a spotlight on this one change effort. Leaders who do this well have a daily focus on the change effort, track its progress carefully and encourage others.

Becoming a change enabler will benefit every aspect of your life, both at home and in business. It will even help you to change yourself.

July 17, 2015

How to Make a Team of Stars Work

In my early years as an executive search consultant in Argentina, I was frequently asked to hire senior investment bankers. Citibank and J.P. Morgan were the leading players in the region at the time, but as I contacted and interviewed most of their key bankers, I saw something strange going on. While both had top people, one was dramatically more successful in the market.

How did the stars at that firm manage to shine brightly together, while those at the other merely twinkled on their own?

For years, I puzzled over the huge performance gaps I often saw between teams that, on paper, looked as if they would be equally effective. You see it in business, in sports, in creative endeavors from movies to magazines. What made the difference? And what was the secret to both evaluating and enhancing team, rather than individual or organizational, dynamics?

My questions were answered in the late 1990s when Elaine Yew, my great colleague at Egon Zehnder, led a firm-wide project called the Team Effectiveness Review, or TER. This proprietary model analyzes six critical team competencies:

Balance: How well a team understands the importance of diversity of skills and strengths and is willing to incorporate them.

Energy:How ambitious the team is, and how much it takes the initiative and maintains long-term momentum at a high level.

Alignment: How well team members understand the larger team purpose, and focus their actions and those of the team on that objective.

Resilience: How well a team can hold itself together even under severe internal or external stress and remain effective.

Efficiency: How well a team understands the need to optimize resources and time and drives efficiently for results.

Openness: How much a team values engaging with the broader organization and the outside world and builds the connections do so.

The underlying premise is that it’s not enough to just hire the right people — those with strong values, great potential, and high competence — and develop them as individuals. You also have to help them work together. Indeed, based on our firm’s 50 years of practice and research, we believe that team effectiveness explains perhaps 80% of leaders’ success.

Don’t believe the popular myth that groups of all-stars don’t work. Of course they do, if you structure and lead them properly. Bain & Company’s Michael Mankins, Alan Bird, and James Root illustrate all sorts of wonderful examples in the article “Making Star Teams out of Star Players.” Some are huge project teams, like the 600 Apple engineers who successfully developed the revolutionary OS X operating system in just two years (compared with the five years it took 10,000 Microsoft engineers to develop, and eventually retract, Microsoft’s Windows Vista). Others are relatively small creative teams, such as the one that so successfully developed the digitally animated marvel Toy Story (which included not only Pixar’s top artists and animators but also Disney’s veteran executives and Steve Jobs himself). And then there are great sports examples, including Kyle Busch’s amazing six-man NASCAR pit crew.

You can and should create an A-team. But remember that it will only thrive when you’ve made it balanced, aligned, resilient, energetic, open, and efficient. In fact, big weakness in any of those six competencies can lead to big problems. For example, teams low on efficiency turn into debating societies that can’t prioritize or make decisions and miss deadlines as a result. Teams low in diversity often succumb to groupthink; they agree with each other too quickly and fail to consider novel courses of action.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

To understand the strengths and weaknesses of your existing team (and perhaps build a better one), rate the group on each of the TER dimensions, using psychometrics, questionnaires, and (most effective) interviews and reference checks with objective assessors. Do you have enough diversity of skills and strengths? Is everyone aligned with your fundamental purpose? Are you all properly prepared to face the inevitable hard times? How ambitious is your team? Have you developed a wide array of internal and external networks? Are you optimizing the use of your time and resources?

Just as no executive will ever be perfect, neither will any team shine on all six TER dimensions. But you can work to improve your scores – for example, by making sure to draw out everyone’s perspectives and encouraging debate at meetings to boost openness or by instituting new communication and decision-making protocols to improve efficiency.

Remember that different situations require different team patterns. For example, turnaround teams need to be very strong in efficiency and while groups working on a post-merger integration need to excel at balance and alignment. Your job is to make sure the group can meet its specific challenges.

Revisiting those teams of investment bankers, I realized that the winning firm had a group that was much more diverse in terms of skills and backgrounds (in fact, one top player was a college dropout and still whole-heartedly embraced by his colleagues with business and finance degrees). Members were incredibly aligned with each other and fully committed to the organization, making it almost impossible to hire anyone away, even at a huge premium in compensation. They were upbeat and engaged, open to new ideas, and able to bounce back from adversity. And, thanks to solid processes and protocols, they were able to collaborate efficiently and effectively.

They were bright stars, brought together in a beautiful constellation.

Adapted from It’s Not the How or the What but the Who (Harvard Business Review Press, 2014).

Why Higher Ed and Business Need to Work Together

Over the past decade, business has changed dramatically. As a result, workforce skills and requirements have also changed. There are jobs today that didn’t exist 10 years ago — data scientist, social media manager, app developer — and in five more, there will be new roles with new requirements that don’t exist now. But while this has happened, one sector has lagged behind: higher education.

The speed of technological innovation and industry demands is moving faster than higher education’s ability to adapt. The system continues to focus on lectures and exams, leaving students underprepared to enter today’s workforce. They’re suffering as a result – along with businesses and higher education institutions themselves. How can we expect students to be effective and successful employees when we’re using outdated models to prepare them?

When we at the IBM Institute for Business Value surveyed a group of academic and industry leaders about the current state of higher education, they agreed. We found that 51% of respondents believe that the current higher education system fails to meet the needs of students, and nearly 60% believe it fails to meet the needs of industry.

Industry and academic leaders revealed that the very skills needed for workforce success are the same skills graduating students lack — such as analysis and problem solving, collaboration and teamwork, business-context communication, and flexibility, agility, and adaptability. Underscoring this point, 71% of corporate recruiters indicated that finding applicants with sufficient practical experience is their greatest challenge when recruiting from higher education institutions.

Boosting the value of today’s higher education system and, most importantly, helping prepare students for life after class, means adopting a more practical and applied approach to education. Those surveyed overwhelmingly agree that providing experience-based and practical learning is critical to address the current performance gaps. Integral to this is building and expanding partnerships between academia and the private sector to create a more valuable education ecosystem.

San Jose State University (SJSU) is an example of an institution that has recognized the need to incorporate experience-based learning and a focus on skills related to social business. In partnership with IBM, SJSU created a program that provides students with the opportunity to deepen their social networking skills while learning to adapt to real-word business challenges. As part of their coursework, students are mentored by IBMers. They learn about internal and external uses for social networking technology, and how it can be applied to business operations — from HR to marketing to product development — for more efficient collaboration and faster innovation.

For example, during one project, students assessed the marketing environment of an IBM business partner. Performing “social business assessments,” the students looked at how the organization collaborated internally and built connections with suppliers. Then, working together, they created a plan to improve marketing operations, suggesting that the company make better use of blogs, videos, and content sharing to improve the flow of information and collaboration across the entire organization. The practical experience from assignments like this better prepares students for tasks they’ll have to do in the real world.

Students also expect their institutions to deliver technologically enhanced experiences, yet higher education doesn’t always deliver. Universities have to start embracing and exploiting new technologies in analytics, cloud computing, mobility, and social media to provide greater access to educational content, integrate physical and digital worlds for more engaging experiences, and improve decision making.

Consider what’s happening at EMLYON Business School. They developed a “Smart Business School” higher education environment that delivers personalized, on-demand business education globally via cloud computing. Business courses are available across devices, in multiple languages, at the school’s campuses in France, China, and Morocco as well as on “pop-up” campuses in emerging markets, such as West Africa. The combination of cloud, big data, and analytics, and EMLYON’s in-depth teaching expertise, creates a “learning by flow” education model that provides unique and personalized development and training that is more directly relevant to today’s workforce and skills requirements. In a similar way that consumers today choose their entertainment, EMLYON students can choose the courses and content relevant to their career path when, where, and how they want it.

Both of these examples also show that in order to transform curricula and embrace technology, institutions should consider collaborating with industry partners. In fact, 57% of industry and academic leaders agree that collaboration is necessary to effectively deliver higher education to students, while 56% believe collaboration is necessary during curriculum development.

The emergence of new collaborative education models are already starting to reinvent education. In 2011, IBM helped develop and introduce Pathways in Technology Early College High Schools (P-TECH), a completely new education model that blends career and technical skills, emphasizes STEM subjects, and combines free public high schooling with community college. It provides students with a solid foundation across the core academic curriculum that’s linked directly to common core standards. This new school of grades 9-14 pairs students, who are admitted with no special tests or requirements, with mentors from the business community. Affiliated companies also provide practical workplace experience with internships. After six years of study, students earn both a high school diploma and an associate degree, and many will receive job offers from sponsoring industry partners like IBM. In the fall of 2015, there will be at least 40 P-TECH schools, serving tens of thousands of students and 100 partner companies.

For multiple generations, higher education has successfully supported growth, economic development, and social change. While the industry has never faced the magnitude of change and disruption it does today, the challenges also come with tremendous opportunity for institutions and their leaders to find new ways to deliver more value to students and the workforce. By capitalizing on new technologies and collaborating with industry forces to build a new model of education and create a supportive ecosystem, we can shape a new way of working and learning. It’s time to reinvigorate our higher education system so students are adequately prepared to succeed in an evolving world.

Know When to Kill Your Brand

Killing off brands is not a popular or pleasant thought, but we should consider it more often than we do. It can be tough to admit that it’s time to pull the plug. Some executives may be reluctant to admit – perhaps for sentimental or political reasons — that their brand is sucking out more value from the company than it creates. Others may simply see no alternative to trying to keep the brand going at any cost, even if that means aggressive discounting, cheap licensing, or other tactics that erode long-term brand value.

Perhaps the source of the problem is that it’s not clear when a brand should be euthanized. Profitability isn’t a useful metric. Most corporations generate 80% to 90% of their profits from fewer than 20% of the brands they sell and many promising start-ups can fail to generate a profit for several years.

A better litmus test for keeping or killing a brand may be purpose. In a 2011 HBR article, Rosabeth Moss Kanter explains that companies are “vehicles for accomplishing societal purposes — by producing goods and services that improve the lives of users; by providing jobs and enhancing workers’ quality of life; by developing a strong network of suppliers and business partners; and by ensuring financial viability.”

In his book, Start with Why, Simon Sinek says that purpose should provide direction when deciding a company’s future: “Instead of asking, ‘WHAT should we do to compete?’ the questions must be asked, ‘WHY did we start doing WHAT we’re doing in the first place, and WHAT can we do to bring our cause to life considering all the technologies and market opportunities available today?’”

Purpose might have informed the management of two failed brands – Blockbuster and Radio Shack — differently. The first Blockbuster store opened in 1985 and quickly became a popular provider of video games and movies to be used on all the new VCRs people were buying at the time. Through the early 2000’s, Blockbuster served a valuable purpose to customers as well as movie studios, game makers, and other content producers – providing direct consumer access to entertainment content. But as Netflix and online media channels developed, Blockbuster was no longer unique in fulfilling that purpose, and the way it fulfilled it became anachronistic. The brand died a slow death, beginning when Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010 and then ultimately when its acquirer, Dish Network, decided to shut down all video rental operations in 2013.

Because Blockbuster could no longer deliver on its purpose in a relevant way, its managers should have euthanized that brand long before it drained shareholder value and became the butt of jokes. There may have been another business that they could have started, utilizing the company’s assets (real estate, technology, staff, etc.) and creating a different brand — or they could have shut down the company and sold off their assets sooner when they would have been more valuable.

Blockbuster’s executives didn’t act quickly enough, but Radio Shack’s leaders might have too ruthless in killing their brand. In 1921, two brothers started the company to serve the ham radio market. It continued to provide electronic parts and equipment for the next several decades and flourished in the 1970s and early 80s, becoming a top spot for electronics hobbyists. Eventually, though, Radio Shack expanded into phones and computers for mainstream consumers and its downfall followed. Competition from big box retailers and Amazon as well as CEO problems certainly contributed to the brand’s demise, but Radio Shack’s biggest misstep was its failure to stay true to its original purpose — equipping electronics DIY-ers and tinkerers. Today, fulfilling that purpose would look different, but it would still be important. The maker movement continues to expand, and demand for lower-cost electronic parts, products, and accessories remains strong. Radio Shack could have also fulfilled its purpose through services and content.

Unlike Blockbuster, Radio Shack’s original purpose still retains potential — if only its managers had realized that and seized it. Unfortunately the company has been taken over by groups that haven’t expressed any intention of leveraging the Radio Shack brand, and so the brand will be put to death prematurely.

When dealing with a struggling brand, managers should ask themselves if their brand is staying true to what it was made to do. Is their brand’s purpose is still relevant? And are they still able to deliver on its purpose in a way that increases differentiation and competitive advantage? If the answer to either of these questions is “no,” can the company pivot to a new purpose that makes use of its existing assets?

The owners of Service Merchandise and Woolworth’s have both benefitted from this line of thinking.

Service Merchandise had risen to prominence during an era when catalog showrooms played an important role in making housewares, electronics, and other goods accessible to mainstream America. But by the 1990’s, big box retailers had taken over the market and the Service Merchandise brand no longer offered meaningful differentiation. After a few unsuccessful efforts to restructure, the company leaders decided to kill the brand and close their stores. Two years later, one of the company founder’s sons sensed the brand could fulfill a more focused purpose — making discount jewelry and gifts accessible — and decided to resurrect the brand as an e-commerce play. Had the previous leadership licensed the brand off or let it deteriorate more than it had, the new owner might not have been able to re-deploy the brand – either because it wouldn’t have been available or because it wouldn’t have had enough equity to leverage.

A decline in the relevance of Woolworth’s purpose is what led the owners of that brand to euthanize it. Sensing the weakening appeal of general merchandise stores, the company leaders closed many Woolworth’s-branded units and converted others into closeout retailers branded The Bargain! Shop. They also acquired athletic shoe retailers whose importance rose as people became more fitness-oriented and more casual in their dress. Eventually they shut down the Woolworth’s brand so they could focus on the Foot Locker brand and renamed the corporation Foot Locker, Inc. Discontinuing the Woolworth’s brand was likely a difficult decision, given its 100-year history and its status as the pioneer of the five-and-dime concept, but it was the right thing to do to maintain brand integrity.

We all love a good comeback story, and corporate turnarounds can turn CEOs into stars. But sometimes the right decision is the more painful one. If your brand is struggling, take a hard look at your purpose, not just your balance sheets. Fulfilling a meaningful purpose in a compelling way can be as life-giving to brands as it is to people.

Recruiting for Cultural Fit

Culture fit is the glue that holds an organization together. That’s why it’s a key trait to look for when recruiting. The result of poor culture fit due to turnover can cost an organization between 50-60% of the person’s annual salary, according to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). But before the hiring team starts measuring candidates’ culture fit, they need to be able to define and articulate the organization’s culture – its values, goals, and practices — and then weave this understanding into the hiring process.

The process of defining organizational culture can take many forms, from working with an external consultant to staff-driven focus groups and discussions. And the result could be a formal statement from the CEO defining the organization’s culture or a list of operating cultural norms that govern the way staff interacts with one another — or both. What’s important is that hiring managers, interviewers, recruiters, and everyone at your company can identify critical characteristics that mesh well with that culture. For example, if a strong sense of entrepreneurism is one of your organization’s cultural hallmarks, ensuring that potential candidates are entrepreneurial, with a track record of thriving in similarly entrepreneurial environments, will be imperative. This would be a key signal of culture fit.

Cultural fit is the likelihood that someone will reflect and/or be able to adapt to the core beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that make up your organization. And a 2005 analysis revealed that employees who fit well with their organization, coworkers, and supervisor had greater job satisfaction, were more likely to remain with their organization, and showed superior job performance.

There has been a lot of talk recently about how looking for culture fit can lead to discrimination against candidates and a lack of diversity. It’s important to understand that hiring for culture fit doesn’t mean hiring people who are all the same. The values and attributes that make up an organizational culture can and should be reflected in a richly diverse workforce.

For example, if collaboration is a key organizational value, people who have a genuine, authentic belief in the value of collaborative work will be a stronger culture fit than those who are more comfortable as individual contributors. This doesn’t mean that only people who come from one particular background or have one particular set of experiences are collaborative. A savvy hiring manager knows that a deep-rooted belief in collaboration could just as easily be found in a candidate with a corporate background as a candidate who has worked in the nonprofit sector or a candidate who has spent most of her career in the military.

Here are some questions that will help assess culture fit in an interview:

• What type of culture do you thrive in? (Does the response reflect your organizational culture?)

• What values are you drawn to and what’s your ideal workplace?

• Why do you want to work here?

• How would you describe our culture based on what you’ve seen? Is this something that works for you?

• What best practices would you bring with you from another organization? Do you see yourself being able to implement these best practices in our environment?

• Tell me about a time when you worked with/for an organization where you felt you were not a strong culture fit. Why was it a bad fit?

You can assess the candidates’ work ethic and style by honing in on the following: whether they succeed in a virtual environment or with everyone in the same space; if they’re more comfortable with a hierarchical organization or can they thrive with a flat structure; and if they tend to collaborate across teams or operate in a more siloed approach.

Finally, expose your candidates to a larger picture of what it would be like to work at your organization. Give him or her a tour of the office and a chance to see how employees at all levels interact with one another at meetings or during lunch. Pay attention to the candidate’s comfort level and gather feedback from staff. The candidate whose behavior and values are consistent with your organization will naturally rise to the top.

If you assess culture fit throughout the recruiting process, you will hire professionals who will flourish in their new roles, drive long-term growth and success for your organization, and ultimately save you time and money.

OTT Video Is Creating Cord-Extenders, Not Cord-Cutters

This year’s Emmy ballot is being culled from the greatest number of scripted dramas eligible in the history of the Television Academy. From Orange Is the New Black to Game of Thrones, from House of Cards to Grace and Frankie, we are enjoying some of the highest-quality TV programming that’s ever been produced and we’re binge-watching many shows whenever and wherever we choose. The irony of this so-called “Golden Age of Television” is that in the corporate corridors of the TV industry, many are still searching for the pot of gold at the end of this programming rainbow – in other words, we’re still looking for the sustaining financial model that will secure the future of the medium.

To many bystanders, the dichotomy of watching the greatest number of big-budget quality productions being created at the very same time as pundits prognosticate the death of cable, satellite, and broadcast networks makes the off-screen drama as compelling as anything happening on-screen. Here’s what we know: The $290 billion global television market is being disrupted by six billion mobile devices and a new generation of consumers that demand their programing when, how, and where they want it. Multi-billion dollar media companies, broadcasters, and cable oligopolies are having to compete for both eyeballs and revenues with a plethora of multinational technology and telecommunications giants who know more about viewer behavior.

Megamergers won’t solve for this disruption. The industry is trying to make sense of over-the-top (OTT) video offerings like HBO Now and Netflix (as well as OTT platform providers like the one I work for), the potential unbundling of cable packages, and a fragmented, multiscreen advertising market.

But an analysis of a comprehensive panel of 22,000 adults fielded this past year by Frank N. Magid Associates yields a surprising finding: OTT is growing the overall pie, not slicing it up. According to Magid’s latest research, instead of fighting over crumbs, OTT is akin to having a second helping.

To understand the data, one first needs to understand how much the pay television industry has changed in the last five years. Video is no longer the cornerstone of revenue for cable operators. Only 40% of cable companies’ profits come from video. The majority of their income comes from broadband internet service. According to the FCC, 82% of American consumers have access to only one provider of broadband at 50 megabits per second or higher. Since OTT requires broadband, these consumers aren’t actually cutting any cords; they are just looking at different ways of managing of their entertainment budget.

If a cable operator, for example, has a 10% loss in video subscribers, topline revenues are reduced by 6%, but profits only shrink by 4%. If, as the current data show, OTT offerings expand the number of broadband customers by attracting those interested in HBO Now or a new “skinny” bundle, overall profits will likely increase until some other entity is willing to invest in competitive infrastructure such as Google fiber.

In fact, some of the biggest users of OTT today are not cord-cutters, but cord-extenders looking for more entertainment options. According to the Magid study, 90% of Netflix subscribers, 90% of Amazon Prime subscribers, and 88% of Hulu customers also maintain pay TV subscriptions. In this sense, multiscreen viewing is not reducing pay TV churn, it is actually increasing consumption.

The overall gender balance of OTT subscribers mirrors that of pay TV, but usage tells a different story and helps us understand who these viewers are. Consumption of OTT original programming skews heavily male and matches the profile of the typical early adopter of technology. Viewers of original programming among the leading three OTT providers break down as follows: Amazon Prime 65% male/35% female, Netflix 55% male/45% female, Hulu 63% male/37% female. Of all the major original OTT programming, only Orange Is the New Black skews female at 41% male/59% female.

Half a century ago, the feature film industry feared the rise of television signaled their demise, only to see the new medium grow the bigger entertainment pie. Each technological advancement since – cable, home video, DVRs – was regarded with caution by the establishment, only to be later embraced as consumer choice expanded both consumption and profits. In this age of endless innovation, the challenge for television industry leaders is to stop complaining about how much has changed and learn to embrace each obstacle as an opportunity.

Television may be one of the first industries to be so visibly disrupted by cloud computing, mobile communication, and big data, but it surely won’t be the last. If the industry can focus on providing better ways for viewers to discover, view, and share the entertainment they love then profits will follow. For the majority of the world, the second screen is quickly becoming the first screen for video consumption, e-commerce, and advertising. By embracing how consumers are managing their entertainment options, this “Golden Age” should turn out to become its most profitable age as well.

July 16, 2015

The Emotional Impulses That Poison Healthy Teams

Is anyone really an individual contributor at work anymore? I think not. Pretty much everything we do is done with others in groups. We’re tasked with planning and completing projects together. We negotiate roles and resources. We talk to one another—or text, tweet, email—and sometimes we listen, too. We’re dependent on and beholden to people above, around, and below us for collective success. We develop habits, over time, that dictate how we behave with one another. Add this up and you’ve got the definition of team: people who share a common purpose and goal, who have distinct roles and responsibilities, and who adhere to certain rules of interaction. Teams are everywhere at work. Sadly, though, most of them aren’t terribly effective—or fun.

How can we improve teams? How can we make them an aspect of work that contributes to our happiness rather than adding to our misery?

To start, we need to pay more attention to how important teams really are in the workplace. In most organizations, there’s a subtle undervaluing of teams. For example, while many companies nod to team-oriented behavior in performance management systems, it is not uncommon for this line item to be divorced from rewards and compensation. This reinforces the notion that we don’t have to pay attention to teams or teamwork (after all, we aren’t rewarded for it). What ends up happening, then, is that teams wither on the vine, at best. At worst, people—team members or leaders—are free to engage in bad behavior which leads to dysfunction, less than optimal results, and miserable team members. It doesn’t take much to blow up a team like this…and many of us have done it.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Paradoxically, it helps to learn what not to do with teams, before moving to what to do to make our teams more effective. Let’s look at some common mistakes even good people make when working together:

Forget your emotional intelligence (EI) and let your amygdala do the talking: Act on feelings and impulses, and don’t filter what you signal, say or do. Don’t let pesky things like social constraints or norms get in the way. Get really pissed off—and stay that way—when someone gets more than you do. Stereotype people who are different from you. Say what’s on your mind then excuse your behavior by telling people that you’re just honest and transparent, which maybe you are, but you’re also just being mean, and if it’s your direct reports, you’re bullying. Unfortunately, given the stress that people deal with at work today, an awful lot of people are walking around in a permanent state of amygdala hijack.

Stick to your guns: Awful phrase. How about “My way or the highway”? Same idea. If you want to ruin a team, be rigid, single minded, and obsessive about your goals or how to get things done.

See the glass half-empty: If you want to mess with people’s minds and kill a team’s spirit, focus on everything that could go wrong. Scare people. Be cynical. Emotions are contagious; and negative emotions and the cynicism and biting humor that go with them kill the trust, creativity, enthusiasm, and happiness that are so important to group success.

Truly don’t care about people: I once worked with an executive who was, in fact, blowing up his teams—and his family. He was at risk of losing the prize at work—the CEO job he’d been promised because he got results. The leaders of this company had, thankfully, figured it out. That this guy got results at the expense of every person and team he touched. Naturally, these results weren’t sustainable. When I asked him why he did this, he told me straight out: “I don’t care about those people.” “Really?” I asked. Underneath this total lack of empathy was a profound belief that his goals, and his way of accomplishing them, were more important. And he was smarter, so what those other people needed—well, it just didn’t matter. It wasn’t until he realized that he was blowing up his family—his wife was about to leave him and his kids had given up asking him to do things with them—that he understood why he was ruining every group and ultimately every part of the business he touched.

Don’t think too much—especially about your motives and feelings: Lack of self-awareness, whether conscious or not, is at the heart of pretty much all of the bad behavior I’ve seen in teams. Take the executive I mentioned above. When we really got down to it, the reason he was blowing everybody up was because he was scared. So, he got them before they could get him at work. And at home, he was scared of intimacy. Yes, he loved his wife and kids. But he just wasn’t ready for real intimacy—so he kept them all at bay.

Far too many of us work in groups that are more than dysfunctional—they are painful and they make us very unhappy. Unhappy people aren’t good workers, and that’s the least of it. People who are unhappy at work are unhappy at home, which means families are unhappy. And on and on it goes. We are better than that. And we can do something about it.

Working effectively in teams takes effort—and it takes emotional intelligence. If you want your team to be healthy, resonant, and effective, take responsibility for the way you show up and what you do.

Studies conducted by Vanessa Druskat and Steven Wolff show that emotional intelligence is essential for team effectiveness. They also show that when more members than not use their EI on a team, that team is more likely to develop norms that support trust, team identity, and sense of collective efficacy. These are the kinds of norms that support sustainable collective success.

Other studies have looked at the relationship of EI to managing conflict on teams, and not surprisingly, there’s a link. For example, Ayoko and colleagues explored the relationship of EI to climate and conflict. They found that there was more conflict around tasks and relationships when empathy, emotional management skills, and conflict management norms were less developed among team members and leaders, the climate suffered—and so did outcomes. Jordon and Troth presented similar findings when they looked at EI, problem solving and conflict resolution in teams.

Working well in groups demands high EI. And if you are going to develop self-awareness, not to mention other competencies like empathy and self-management, you’ll need to go deep. That’s because improving your EI is as much about personal growth as it is professional development.

A final note: That executive I worked with? He worked hard to develop his EI, especially self-awareness, empathy, and self-management. He got the job. And he applied what he learned about himself and his impact on others to his family. He started really seeing his wife and kids, maybe for the first time in years. It took time, but they became close again.

Will Africa’s Growth Help Africa’s People?

The Mediterranean Sea has become a graveyard for Africa’s youth. Every day, we see images of what would appear to be a continent racked by conflict and poverty, and people risking – often losing – their lives in an attempt to flee. Yet Africa has 11 of the 20 fastest growing economies in the world. Africa has enormous resources, and almost half of the world’s uncultivated land that is suitable for growing food crops. So why are so many people desperate to leave behind a land of such opportunity?

Part of the answer is that the vast wealth of Africa is often not being translated into development. Often it benefits only a few, or is squandered altogether. Illicit outflows from Africa totaled $69 billion in 2014.

So often the focus on Africa’s challenges is a call for more resources. But to achieve development, we need much more than money.

Certainly, money can address some of the deficits that trap millions of people – especially rural people — in poverty. They need infrastructure, starting with the roads that will take them to school or market, as well as electrification, water and sanitation systems. They need education, health care, decent wages, access to finance.

But there are also things that money can’t buy. Leadership, good governance, commitment to the rule of law, and an enabling environment to attract investment. The social responsibility to pay fair wages, create decent employment, and pay taxes.

The Third International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD), convening this week in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is one of several important milestones toward a new international consensus on eliminating extreme poverty and hunger. Without a solid consensus over the financing and resources needed, goals remain simply wishes.

But it’s not just about the money, still less about aid in the conventional sense. The key to a sustainable future free of poverty and hunger is people. The world leaders gathering in Addis need look no further than the continent where they are meeting to see this.

Africa is rich. Its extractive industries have provided revenues in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Yet Africa’s resource-rich countries have some of the world’s highest child mortality rates, and a dozen have in excess of 100 child deaths for every 1,000 live births. This travesty illustrates that there are other resources besides money that are necessary for development, starting with leadership, accountability and commitment.

It also points to the importance of developing the potential of Africa’s smallholder farmers. Three quarters of the world’s poor and chronically hungry people live in rural areas and are also mainly dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods. Smallholder farmers and rural entrepreneurs could contribute much more to producing food, job creation, national economic growth, and the preservation of natural resources. Yet they often lack the tools to do so. And many of those who are producers of food go hungry themselves.

Investment in rural development is key to delivering a host of development objectives, including adequate food, clean air, fresh water and biodiversity. And growth in the agricultural sector has been estimated to be at least three times more effective in reducing poverty as growth in any other area. In sub-Saharan Africa, the figure is 11 times.

Change must start from within. An institution like mine, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, offers support. We are investing. We are sharing knowledge and best practices. As the only international financing institution in the United Nations we are committed partners in rural transformation. But the fact remains that no donor institution can transform countries unless they are willing to transform themselves.

Ethiopia, a country once synonymous with famine, is now among Africa’s fastest growing economies. The introduction of sound macro-economic policies, strong leadership and a robust agricultural transformation agenda have done what no amount of aid alone could have. Ethiopia is Africa’s number one exporter of honey, and has the second largest horticultural industry.

So let us remember that commitments must not be measured in dollars alone. True, to save ourselves, our future and our planet, we need major resources, both public and private. But we also need the commitment of responsible governors, legislators, investors, business people and partners of all kinds to see that the investments are just and inclusive. And this has to happen beyond Africa. The Addis Ababa Accord provides a chance not just to count the money, but make sure the money counts.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers