Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1274

July 13, 2015

A Way to Know If Your Corporate Goals Are Too Aggressive

Has your company inadvertently set a goal with just a 1-in-20 chance of success?

That can happen all too easily, and the consequences are potentially serious. Setting financial performance targets that are too aggressive can mean that even the best efforts go unrewarded, leaving people demoralized. Worse, in an attempt to meet unrealistic targets, people may feel increasingly tempted to cut corners or to resort to unethical or illegal behaviors that they would otherwise be loath even to contemplate. Setting overly conservative goals is hardly an alternative, however; they can leave money on the table, leave people unmotivated, and lead to accusations of sandbagging.

For better goal-setting, it will help to understand where financial targets typically come from. Often, they’re based on past performance. But a company’s recent track record says nothing about how much its performance could or should improve; what’s needed is a useful assessment of a company’s probability of future success.

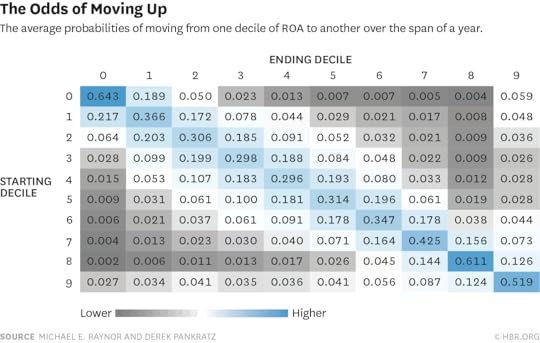

One way to think about the likelihood of hitting a given performance increase is to consider how frequently other companies have made similar improvements. Using more than four decades’ worth of data on U.S.-based public companies, we constructed a table that captures the frequency with which companies have moved from one relative performance rank to another in one year on a given measure. (For more on our approach to estimating relative performance ranks, see our earlier post. We believe that we can help you estimate the probability of success for your company’s goals. See the Deloitte Exceptional Performance website.)

For example, all else equal, the probability that a company will improve from the sixth decile of revenue growth (meaning that it’s better than six-tenths of companies, adjusted for industry and size) to the seventh (meaning that it’s better than seven-tenths) is 35%. In contrast, going from the sixth decile to the ninth (meaning better than nine-tenths of companies) is just 6%. The chart shows an abbreviated version of the “transition matrix” for ROA, with probabilities of advancing from one relative level to another expressed as fractions of 1.

This population-level analysis says little about what your company will be able to do, but it does provide an objective and quantitative way to know what’s been possible and feasible for other companies. Rather than relying on potentially impracticable targets such as “Take last year’s performance and add 10%,” you can use an assessment of the probability of success to anchor evaluation of performance-improvement strategies.

For example, if senior managers determine that a dramatic improvement — one that has a low expected likelihood of success — is called for, then they should be prepared to pursue a more aggressive strategy. Expecting low-likelihood increases in profitability when the plan calls for little more than garden-variety cost-cutting implies a potentially serious mismatch; aiming for a breakthrough disruption would be a strategy that, if successful, would be likelier to achieve breakthrough financial results. (See Michael Raynor’s The Innovator’s Manifesto for data on the financial performance of disruptors.)

These extreme examples might seem obvious, but the picture of corporate goal-setting that emerges from a survey we conducted recently suggests they may not be as far-fetched as one might think.

We polled 301 executives from large companies, asking them for their companies’ profitability and growth goals for the coming year and their views on their chances of hitting those goals. Using data on how frequently companies have made similar transitions historically, we then independently calculated their odds of achieving their goals. We found that respondents who were more confident — who thought there was a 75% chance or better of success — had not, in fact, set more-attainable goals. In any given individual case, of course, an optimist might be right; some of these companies may hit their low-probability targets. But overall, across the sample, there is a worrying disconnect between expectations and how American companies have historically performed. Note also that almost none of our survey respondents thought it was very unlikely (that there was less than a 10% chance) that they’d hit their goals.

Many budgets and strategic plans include financial performance goals of some sort. In many cases, leadership compensation, shareholder returns, and broader judgments about whether a company is considered a “success” or “failure” are based on whether it meets or beats these performance targets.

But with so little correspondence between reported chances of success and the probability of success as estimated by our method, there is too high a likelihood that the plans supporting companies’ objectives are similarly out of alignment. None of which is to say that companies should not set ambitious goals — or conservative goals, for that matter. But a company’s goals should be in line with the aggressiveness of its strategy, its appetite for risk, and its ability to manage that risk.

How to Manage a Team of B Players

In 2004, Greece surprised the world by winning the European Championship, the toughest tournament in international soccer. Despite not even being a dark horse in the competition, and with a team of mostly peripheral and unremarkable players, they overcame France and hosts Portugal (twice) to lift the trophy. Even hardcore soccer fans would be unable to name more than two players in that Greek squad, yet few will forget the remarkable collective achievement of a team that faced odds of 150/1 for winning the trophy.

What allows a team of B players to achieve A+ success? A great deal of scientific evidence suggests that the key determinants are psychological factors — in particular, the leader’s ability to inspire trust, make competent decisions, and create a high-performing culture where the selfish agendas of the individual team members are eclipsed by the group’s goal, so that each person functions like a different organ of the same organism. In the famous words of Vince Lombardi: “Individual commitment to a group effort — that is what makes a team work, a company work, a society work, a civilization work.” This is true for all teams, of course, but if you’re leading a team of B players (people who are just average in terms of competence, talent, or potential), your leadership matters even more. In fact, if you are leading a team of B players, you have to be an A-class leader; otherwise, your team will have no chance.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Although effective leaders can have a wide variety of styles, they do tend to share some common personality characteristics. First, they have better judgment than their counterparts, meaning they can make good decisions, learn from experience, and avoid repeating mistakes. Second, they have higher EQ, which enables them to stay calm under pressure, build close and meaningful relationships with their teams, and remain humble even in the face of victory. Third, they are insanely driven and tend to have very high levels of ambition, remaining slightly dissatisfied with their success: this is why they stay hungry and continue to work hard, as opposed to getting complacent.

In addition, there are four important tactics any leader can use to make their teams more effective. These key management elements have been found to work even with B players, and could transform a team of average individual contributors into an over-performing team. They are:

Vision. The first component needed to turn B players into an A team is vision, that is, a winning strategy that represents a meaningful — and attainable — mission for the team. Yes, it’s true that all teams need a vision, even teams of A players. But with A players, you might be able to skate by with a hazy picture of the future, or a goal that shifts over time, or an endpoint that doesn’t include a strategy of how to get there. If your players are not amazing, then you need to ensure that your goal is clearly defined and doesn’t waver. It should be something that stretches them, but doesn’t demoralize them by being unattainable. And it should include a plan of attack – milestones and tactics that will allow the team to figure out their next steps. When the strategy is right, success will be less dependent on the individual brilliance of the players (and you can always rely on the competition making a few mistakes).

Analytics. No matter how smart and experienced leaders are, they will make smarter and better decisions if they are armed with data. Data can cut through the biases and politics and create a culture of fairness and transparency. It can also highlight the key individual drivers of team performance, breaking down success into molecular factors that can be easily manipulated. Of course, intuition is still needed to translate any data-driven information into useful knowledge, and there are many problems data won’t solve (see point 4). But a team with better monitoring systems for quantifying performance will always have an edge, and the power of feedback will always depend on the accuracy of the analytics (see point 3).

Feedback. Meta-analytic studies have shown that individual and team feedback improves performance by around 25%. This margin is substantial enough that it lets less skilled teams who get a lot of feedback outperform more skilled teams that aren’t getting feedback. Why is feedback so important? Because it allows both individuals and teams to regulate their efforts – the essence of motivation is self-regulation, but self-regulation only works with accurate feedback. Of course, feedback is also essential to correcting mistakes and getting better, and leaders who fail to provide it risk coming across as indifferent and disinterested in the welfare and performance of the team. When you have a team of B players it is particularly important to be honest with them about their relative limitations. Instead of making them think that they are better than they actually are, tell them they will need to work hard to close the talent gap between them and their rivals because on skill and potential alone they would lose.

Morale. Leaders own the job of creating engagement. Although individual engagement is critical, team morale is the key. You might have a team of B players, but when they share common values, drivers, and motives, and care about each other much like friends, they will raise their performance for each other. Thus any leader should focus a great deal on helping his/her team members bond. If they fail to cohere, intragroup competition will trump any collective success, leading to intergroup failure. This may seem like common sense, but too many managers are so focused on managing processes and attending to the formal aspects of task performance that they forget to build an engaging culture. In addition, when leaders are interested mostly in their own career, and success is not defined in terms of their team’s performance, they will tend to neglect and eventually alienate their teams.

In short, good leaders can turn B players into an A team, by following the right strategy, gathering precise performance data, giving accurate feedback, and building and maintaining high morale. Since few leaders manage to achieve this even when they have a team of A players, there is much hope for those who do.

As Greece’s soccer coach Otto Rehhagel explained when asked the secret to is team’s success, he noted it was mostly about his relationship with the players: “I cherish them, I hold them in the highest esteem. I know what makes these boys tick. I don’t lead by committee. I take the responsibility for my choices.”

Just Because You’re Happy Doesn’t Mean You’re Not Burned Out

A new survey report just published by Staples Advantage offers a paradoxical set of findings about US office workers. Overwhelmingly, they are happy. Yet the majority of them feel burned out. How could both things be true?

First, a look at the statistics. The good news is that 43% of respondents report being “very happy” at work, and another 43% say they are “somewhat happy.” That is a fairly ringing endorsement of office work, especially in a culture where Dilbert comics and The Office have seemed to strike such a chord. The bad news, however, is that 53% of the same office worker population report feeling burned out at work.

My guess as to how these numbers can be reconciled would be that the overwhelming majority of these workers like the nature of the work they do. Perhaps, to borrow Gallup terminology, it gives them the chance to use their strengths every day. It might also enrich their lives by allowing them to contribute to products and services that make the world a better place. At the same time, however, most of these workers must be feeling stretched too thin. Their workplaces are making it hard for them to limit their hours and workloads to healthy levels.

You might say: so what? If 86% of workers are happy, that sounds like success. Why mess with it? Here’s the problem: When people tell you they are burning out, they are signaling trouble ahead. They are telling you the situation is unsustainable.

The causes of burnout can be many. Psychologists often point to jobs where workers have high demands placed them but are given low control as being the most stressful. In the case of the Staples survey, however, respondents are very specific about what is damaging their wellbeing. A 52% majority report burnout from putting in too many long days.

If too much time spent working is the problem, the solutions are not hard to devise. Most obviously, employers could reduce the overtime demands they put on people by assigning more reasonable workloads. Other strategies to retain the same productivity would be to provide more flexibility, to waste less of the hours workers are spending on the job, and to make the work less exhausting. Each of these deserves a closer look.

Rein in Excessive Time Demands

Many, including myself, have written about the toll chronic overwork takes on people’s lives and what employees can do to combat its effects. It’s a subject I researched extensively for my book, The Working Dad’s Survival Guide: How to Succeed at Work and at Home. The Staples study confirms it is a reality for many workers: a quarter of them say that after they leave the office at night, they “usually” continue their work at home. Fully 40% put in hours over the weekend at least once a month.

While I think most employees would agree that occasional overwork is an acceptable part of the modern workplace, no one should consistently be given more work than can be reasonably accomplished during paid hours. Rather than turning a blind eye to constant encroachment on people’s nonwork lives, employers should honestly assess the time workers are taking to accomplish the work being asked of them. When staffing levels are dialed down to “lean and mean,” employees are overburdened and overworked. When employees feel compelled to stay plugged into work 24/7, they have less time for life and to recharge. Rather, we should build in enough teamwork and overlapping responsibilities to allow emergencies to be handled and gaps to be filled without employees’ routinely being pressured to go above-and-beyond.

Provide More Flexibility and Autonomy

Workers are able to make the most productive use of their working hours when they can adjust the time and place of their work to best avoid conflicts with other responsibilities. Employers don’t necessarily have to institute formal programs to allow for telecommuting or flextime. Indeed, informal and ad-hoc arrangements often prove to be more effective. The key is simply the willingness to let employees construct working arrangements that suit the content of their jobs, their working styles, and their family and other non-work demands. By upholding performance standards, but providing autonomy regarding some of the where, when, and how of work, you can help your employees find more time in their days and avoid burning out.

Waste Less of Employees’ Time

More than a third of the office workers responding to Staples’ survey say they are victims of email overload and cite that as a negative impact on productivity. One in five report they spend more than two hours a day in meetings, and over a quarter characterize the meetings they attend as inefficient. Both forms of distraction are within management’s power to reduce. As the Staples report authors point out, policies can be devised to reduce message volumes and employees can be trained and encouraged to use email more effectively. Meetings can be required to have thought-out agendas and clear follow-up steps, and only called when necessary.

Make Work Less Exhausting

Finally, even if work hours are long, workers can experience less burnout if they are given chances throughout the day to recharge and refocus. It’s when employees feel compelled to press on through lunch and forego breaks that they hit their physical and psychological limits. Meanwhile, workers who modulate the pace of their work and occasionally step away from it – often literally, by taking a walk – experience overall boosts in productivity. Managers can model such behaviors and stop signaling in various ways that to be a great employee is to be a workaholic. Need a way to change the tone? Why not treat your team to lunch and steer the conversation away from work. Ask a colleague to go for a walk mid-afternoon. Give the break room a makeover so it’s more inviting.

In general, treat your people as exactly what they are: knowledge workers who are happy in their roles, and whose time is precious. People in offices today seem to love their work, but that doesn’t mean they can neglect everything else in their lives to take on more of it. And it doesn’t mean employers should take advantage of their desire to succeed. Managers who encourage the attitude that work is life only manage to burn their best people out, and have no one to blame but themselves when productivity goes up in flames.

July 10, 2015

Setting the Record Straight on Switching Jobs

“Stay in a job for at least two years.”

“Never leave a job until you have your next one lined up.”

Everyone from your mother to your mentor has advice about the best way to switch jobs. But how can you know whom to trust? Especially since what was true in the job market 20 years ago — even two years ago — is not necessarily gospel now. And the market is constantly changing.

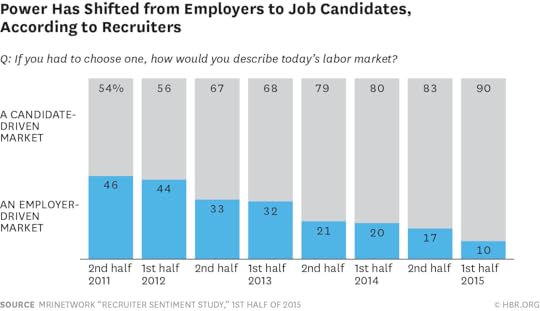

Consider the power dynamic between candidates and employers, for example. Though it differs across industries and regions, and is dependent on the health of the economy, in the past few years, experts have described the current labor market as “candidate-driven.” Job seekers hold more power than employers, a trend that seems to be deepening.

So does this mean when switching jobs, you’re in the driver’s seat? Not necessarily. But it does mean that you can’t rely on “age-old” guidance. We asked readers (and our own editors) what advice they hear most often about how to switch job and then talked with two experts to get their perspectives on whether the current wisdom holds up in practice and against research.

1. “Never tell your boss that you’re looking for another position.”

It may seem logical that you want to have a job in hand before you reveal to your manager that you’re leaving. After all, you don’t want your boss to be mad at you or stop investing in you. But things have changed. “It used to be when you left a job, you were seen as a traitor,” says John Sullivan, an HR expert, professor of management at San Francisco State University, and author of 1000 Ways to Recruit Top Talent. Companies have changed their tune and now make efforts to be sure people leave on good terms. They recognize that former employees are out there on social media, says Sullivan, and they don’t want to “risk being disparaged on Glassdoor, Yelp, Facebook, or Twitter.”

In fact, many companies now have programs that keep the door open in case employees want to return. The idea is that if you’re a valuable employee, the company wants to get as many years as they can out of your career — and those years may not all be in a row. Companies like Davita Healthcare, Yahoo, and KPMG are hiring large numbers of return employees. About 15% of Davita’s hires are people who have worked there before, says Sullivan.

Not only is there less risk in letting your manager know that you’re looking than there used to be, but there may be great upsides too, says Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, a senior adviser at global executive search firm Egon Zehnder and author of It’s Not the How or the What but the Who: Succeed by Surrounding Yourself with the Best. First off, your boss may want to figure out how to keep you. When Fernández-Aráoz worked for McKinsey in Europe in the 1980s, he wanted to move back to Argentina so he let the office leader know that he’d be leaving the job. They offered to let him work from Argentina while he looked so that they could get as much time out of him as possible. “Being open actually improved my last year enormously, and helped me get a terrific job,” he explains. He got a great reference from his former boss at McKinsey who talked about his openness and loyalty to the firm.

And if staying with the company isn’t realistic, you may find ways to continue to work with the company. Fernández-Aráoz points to the advice in The Alliance by Reid Hoffman (the cofounder and chairman of LinkedIn) and his coauthors that life-long employment is no longer realistic but being a completely free agent isn’t perfect either. “The alternative is what they call a ‘transformational alliance,’” explains Fernández-Aráoz, “where through honest conversations you explicitly agree on a temporary alliance, clarifying expectations regarding your contribution to the organization and what the organization will provide you in return, which may well be the support to continue your career elsewhere.” This is popular in Silicon Valley now, and “is probably showing the way to talent and career management over the next decades.”

Even if you think your boss or company might be open to the idea of you leaving and possibly maintaining a relationship in some way, the conversation can be uncomfortable. And it will be far worse if you suspect your manager won’t be understanding. Sullivan says: “If you’re boss is a jerk, you may want to wait.”

2. “Stay at a job for at least a year or two — moving around too much looks bad on a resume.”

“This is a popular piece of conventional wisdom,” says Sullivan, and it’s simply not true anymore. First of all, it’s not always realistic. “There are many times when you really need to leave your job without anything else,” says Fernández-Aráoz. You may need to relocate because of your spouse’s job or quit to take care of a family member.

Second, short stints no longer hurt a resume. Sullivan says that employers have become more accepting of brief periods of employment. As many as 32% of employers expect job-jumping. “It’s become part of life,” says Sullivan. In fact, people are most likely to leave their jobs after their first, second, or third work anniversaries. Millennials are especially prone to short stays at jobs. Sullivan’s research shows that 70% quit their jobs within two years. So the advice to stick it out at a job for the sake of your resume is just no longer valid.

Gaps in job history aren’t the sticking points they once were either, says Sullivan. “No matter what the reason — you got laid off, you took time to write a book, care for a family member, travel — it’s no longer seen as problematic.” You just have to show that your time off wasn’t a waste of time. Employers, says Sullivan, just want to know that you made use of the time either to gain a new skill, have a life-changing experience, or learn something new.

Still, says Fernández-Aráoz, you should avoid jumping around if you can, not because of any potential damage to your future job prospects, but because of the emotional drain. “The real problem is starting again to find a new place, a new location, new friends, constantly reproving yourself,” he says. You can avoid a lot of switching by thoroughly assessing any potential jobs. Because many interviews are what he calls “a conversation between two liars,” it pays to get a sense of what the job will truly be like in other ways. Some companies will offer a realistic job preview that will give you an inside view of the company, not the sugarcoated perspective you get in a series of interviews. Ask for one when considering your next job, suggests Fernández-Aráoz, or do as much research as you possibly can before accepting the offer.

3. “Don’t quit your job before allowing your current employer to make a counter offer.”

If you’re a valuable employee, Sullivan says that smart companies will make an attempt to convince you to stay. “If you’re on their priority list, it would be considered ‘regrettable turnover’ for them and they’ll do what they can to keep you.” Counteroffers have become much more common especially in industries where there’s talent scarcity or for highly specialized roles, according to Fernández-Aráoz. “They usually come with some form of flattery, promises, and even better conditions,” he says.

But be careful, he warns: “In my three decades of experience, I’m genuinely convinced that most counteroffers are bad for all parties.” He gives two reasons you shouldn’t accept a counteroffer. First, there was a reason you started to look for another job and that’s unlikely to change despite your employer’s promises. “The rule of thumb among recruiters used to be that 80% of those accepting counteroffers leave, or are terminated, within six to 12 months, and that half of those who accept them re-initiate their job searches within 90 days.” Even if your manager is able to make good on the promises in a counteroffer, there is the issue of broken trust. “They may still consider you less loyal and therefore offer you lower chances of future development.” Second, Fernández-Aráoz says, “you’ve made a commitment to the new company and you should honor it.”

Of course, you should make a sound decision based on the unique situation you are in and analyze both alternatives. Fernández-Aráoz suggests looking at the long-term potential rather than the short-term benefits. Which opportunity will give you what you want in the future?

4. “Never make a lateral move — a new job is your only chance of making a big leap in title and compensation.”

“That’s so last year,” says Sullivan. “Yes, the old model was that you were Assistant VP, then VP, then Senior VP. But that’s GM in the 1980s, not today’s organizations.” He says given how flat companies are today, there’s often nowhere to go in your current job or in another one. You should focus on finding interesting work rather than worrying about lateral moves.

Fernández-Aráoz agrees: “If you are going for title and compensation, think again!” More money and a better title rarely are what make you happy in a job, he says. Instead, look for autonomy, mastery, and purpose (as Daniel Pink describes).

5. “You should always be looking for your next job.”

You want to be happy, not constantly searching, says Fernández-Aráoz. “Ideally, you should never be looking for your next job, simply because you love what you do.” He points to research Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has done on the state of “flow,” describing it as “a neurological condition of our brain in which we achieve maximum productivity while our brain consumes very little energy. We are fully immersed in what we do, fully absorbed, even losing a sense of time, and we’re able to function at our best.” When you have found this in a job, looking for your next one is unnecessary.

But, even if you’ve found a role that keeps you happy, you should still be learning and growing, says Sullivan. He points out that this doesn’t have to be a new role with a new company, but can be a different role or challenge in your existing job. “The world is changing so rapidly that you have to be agile or adaptable. You should constantly look for projects that give you more skills, do things outside of your comfort zone, so that you have another skillset, not just the one you need for your current job.”

The average length of time a worker stays in a job these days is 4.6 years. That means over the course of your 40-year career, you’ll switch jobs just under 10 times. Ideally those moves will be in search of a more fulfilling, challenging, and satisfying job.

Successful Startups Don’t Make Money Their Primary Mission

Some people look at Silicon Valley and see a world filled with fortune-seekers come to strike it rich.

Yes, the Valley has its share of mercenaries. But you’ve never heard of the companies they founded or ran, because those start-ups couldn’t attract or retain good talent, win solid investment backing, or earn customers’ good will.

What drives the most successful start-ups isn’t the money, it’s the mission. The founders who go on to create the greatest value for themselves and their investors are those with a vision of changing the world in some way.

People outside Silicon Valley are often puzzled by the apparent contradiction between the idea of companies having missions and the goal of big returns for investors.

As Jim Barksdale put it when he was CEO of Netscape, “saying that the purpose of a company is to make money is like saying that your purpose in life is to breathe.” Of course, if you’re not breathing, it doesn’t much matter what your purpose in life is. If you believe in your mission, then it’s part of your moral imperative to attach a business model to it. There’s no faster way to achieve your lofty goals. But that’s the order for it: The business model exists to serve the mission, not the other way around. That’s how Google managed to organize so much of the world’s information in a few decades, and Facebook managed to connect the wired world in just one.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

But for founders who are in it just for the money, there are too many reasons and ways to quit before the company becomes a massive success.

After all, starting a new institution from scratch is really, really hard. Sometimes people stop because there’s no more money, or customers don’t like the product. High-profile secret-sharing app Secret just shuttered its virtual doors and gave its remaining money back to investors when customers started leaving.

Other forms of quitting are less obvious. When a social-mission company sells out to a big corporation, the founders all get rich and sometimes the investors even make a little money. But that’s quitting too; no company ever changed the world by selling early. Often what happens is the acquiring company eventually shuts down the project and reassigns or lays off the employees.

The selling-early kind of quitting is actually more dangerous and represents a greater loss for investors than the giving-up-under-hardship kind. For a start-up investor, losing the entire investment is the expected outcome. For good investors the losses are more than covered by the few massive successes — but a company with fantastic potential can’t become a massive success if it sells early.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin grew Google to its current dominance by sticking to their information-organizing mission. It was a mission they believed in enough to turn down an offer of $1 billion for their company from Yahoo. Google is worth over $350 billion today.

Yahoo also offered Mark Zuckerberg a billion dollars for Facebook while it was still an exclusive site that didn’t let most people join. He turned the offer down (along with many larger offers, including from Google). His mission to connect everybody wasn’t done yet. The company is worth over $200 billion today.

Imagine if Google and Facebook had sold to Yahoo for a billion each — a great outcome by any measure. But inside Yahoo, would Google have continued its crazy missionary projects, like scanning the world’s libraries or organizing all scholarly papers? Would Facebook have connected everybody with social news feeds and a constant flow of new mobile products?

In each case, the company’s greater mission and its financial success were intertwined.

Employees also have to be inspired by the mission. If employees are just mercenaries, they will disappear as soon as a better offer comes along. For investments to have a chance of becoming unicorns — billion dollar companies — they need management teams and talent that will persevere through the tough times and not sell out early in the good ones. Experienced investors know this — John Doerr at Kleiner Perkins often talks about looking for missionary founders rather than mercenary founders.

Of course every company has the obligation to become a successful financial business, but the reason it exists is its mission. Lose sight of that, and you lose the company.

Communicating a Corporate Vision to Your Team

Amit* manages a team of 40 people around the globe for a massive tech company. After months of furiously working on a new product to be the first to market, his boss told him that the company’s strategy had shifted. The product’s launch plans were then delayed, and competitors began gobbling up market share. Amit’s team felt deflated. Instead of celebrating a launch, they found themselves mired in more contract negotiations, tactical challenges, and follow-up calls. They doubted the new strategy. Amit had to restore their trust and motivation. He needed to communicate vision.

Let’s clear something up. Amit’s big task was not to set the vision. In this case, the product strategy had changed at the top. His job was to translate the executives’ thinking behind the changes, so his team could understand why things had changed and how they were supposed to redirect their efforts. After all, they were now being told to scrap all the work that was done, go back to the drawing board, and renegotiate every painstaking contract. Without clarity around the why and how, it would be hard for them execute the new strategy.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

There are two things to remember when trying to communicate an organizational vision to your team. First, you have to target your message. Your team in IT has different needs than Susan’s team in marketing. Leaders are responsible for translating the same vision into different messages that their unique teams will respond to. Second, augment logical reasoning with an emotional appeal to inspire. That’s how you get buy-in, and how you shift the team’s response from “I have to,” to “I want to.”

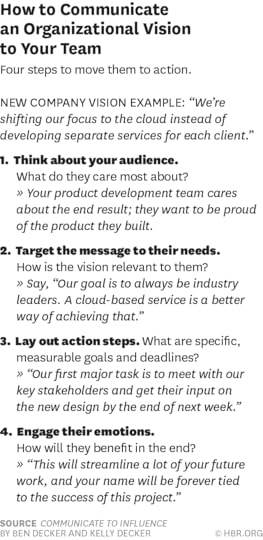

We’ve developed a communication approach that breaks this down into four key components to be addressed: listeners, point of view, actions, and benefits:

Understand your listeners. Step back and think about your team. Sure, you know the player roster well, but attitudes change over time (e.g., from the beginning of a project to the end). Before you start on the vision, take a few minutes to answer the following questions about your team:

What do they know about the current status of your project or goal or bigger strategy? What are they expecting? How do they feel about the team and organization right now?

How would they challenge the vision? What would make them resistant?

How can I help them? What problems am I trying to solve that will make their lives better in some way?

Find the lede of your story. With the broader vision in mind, it’s time to develop the specific point of view for your team. Think of this as the why behind the message. What is the one thing that you want everyone to walk away knowing? (Warning: Don’t get too granular or tactical. You’re looking for a motivator—some way to get the team to nod their heads and accept the change.)

For Amit’s team, he couldn’t default to something as narrow as, “We need to negotiate new contracts for the new changes to our product.” Yes, that was a key element (and it needed motivation!), but that wasn’t an inspiring vision. Instead, he had to make it bigger. “Our current product faced a massive risk of being commoditized. Our products have never been commodities! We must always position ourselves as the leader in this space.”

Point the way. After you have developed your point of view, it’s time to zero in on your next challenge: converting vision into action—or pointing your team toward the right direction so they can make something happen. You don’t have to lay out every step that leads to your ultimate goal, but you have to be specific and set benchmarks and deadlines. Action steps have to be physical, timed, and measurable to pave a way toward the vision that the team can actually see.

For instance, Amit’s team had much work to complete over the next quarter. To get them started on renegotiating the contracts immediately, he asked each of them to schedule meetings with three key stakeholders by the end of the week.

Give them a reason to believe. Your message also has to address what’s in it for them—each of them. Too often we provide a laundry list of general benefits that are far too removed to really motivate anyone. Better ROI, increased top-line growth, and greater customer satisfaction are all great for the organization … they just don’t mean that much to us as individuals.

Team leaders have to drive the benefit down to the individual level as much as possible. The best way to do this is to connect the dots. Go back to how you described your team. Amit could appeal to his team’s pride in leading the industry, or the accolades they would add to their professional trophy cases: “Look at what you’ll create.” This individual focus engages people’s emotions and moves them to action. After all, logic makes us think, emotion drives us to act.

Emotion can also come from analogies, stories, or concrete examples that illustrate what success looks like. As Chip and Dan Heath describe in Switch, you want to create a destination postcard, or “a vivid picture from the near-term future that shows what could be possible.” Describe exactly what success will look like for your team, so everyone envisions the same goal. They should reach the same answers for questions like: How will a customer feel when they use the product? What will the analysts say? How about kudos from the top? What do the ratings and reviews show?

In order to get his team’s buy-in, Amit had to be more transparent about why the company was shifting to the new plan. He also had to demonstrate that he was listening. So, he explained how individual strengths and contributions from team members would move them forward. This approach helped Amit’s team feel proud and invested, yet again. The change in morale was noticeable across emails and check-ins. His team started building momentum again.

As a team leader, you’re not always the one to set the grand overarching vision, but your role – communicating it and casting it in a way that motivates your team – is essential. Getting your team to see how their work matters on an organizational level will keep them motivated and productive—especially during times of change. It will also reflect well on you as their manager. That’s the value of the vision.

*Name has been changed.

Just Hearing Your Phone Buzz Hurts Your Productivity

By now we know that we’re (mostly) not supposed to multitask — that we can’t do two things at once very well and that it takes us a while to refocus when we switch from one task to another. This is why we put our phones screen-side down and slightly out of reach when we want to focus on something or show someone that we’re paying attention. But unless your phone is fully silenced or off, it’s probably still distracting you. The familiar buzz buzz of a new notification is not as innocuous as it seems.

This may sound intuitive. But many people (including myself) might not realize just how beneficial switching from vibrate to silent can be. A new piece of research, “The Attentional Cost of Receiving a Cell Phone Notification,” reports that the reverberations of new notifications can distract us, even when we don’t look over to see what they could be. It found that just being aware of an alert can hurt people’s performance on an attention-demanding task.

The authors, Cary Stothart, Ainsley Mitchum, and Courtney Yehnert of Florida State University, became interested in the impact of these notifications after noticing that they themselves got distracted by them.

“If we were driving and we felt a vibration for a phone call, that led us to think about the source of that call — who it could be, what the message was,” Stothart told me.

They knew from the literature on distracted driving that talking on the phone causes a cognitive load, which means it requires a certain amount of mental effort and working memory. Multitasking, for example, imposes a heavy cognitive load and hurts performance on a task, because our mental resources are finite and have to be allotted to discrete tasks. That’s why you’re not supposed to talk on the phone or text while you’re driving, and why many campaigns urge drivers to wait to respond until they’re no longer behind the wheel.

This led the authors to think that an alert or notification could also cause cognitive load, because that buzzing might make you wonder about the content or source of the message. So even if you wait to respond until you finish what you’re working on, the fact that you’re aware of something waiting for you could be enough of a distraction to make you perform worse than you would had you not received a notification.

In 2013, they recruited 212 undergraduate students at FSU to participate in an experiment. The students would come to their lab, provide their phone numbers, emails, and other information, and then complete a Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART). This measures sustained attention, or your ability to focus on one task without drifting off and thinking about something else. The task had students press a key any time a number flashed on a computer screen, unless that number was “3.” They did this for about 10 minutes — this was the first “block” of the task that gave researchers a measure of baseline performance —and then they had a minute-long break. Meanwhile, a computer had randomly assigned participants to one of three groups. So after the break, one-third of participants started receiving text messages as they completed the SART a second time (the second block), while one-third received phone calls, and another third served as a control and didn’t get anything.

Participants completed the experiment individually, with one experimenter in the room to note if anyone actually took out his or her phone. Since the researchers were only interested in how the knowledge of receiving a notification affected performance, they excluded people who interacted with their phones from the analysis. The experimenter didn’t know beforehand which people would get notifications, as a computer sent those out randomly.

The students weren’t told to leave their phones out or unsilenced or anything, but they were asked afterward if they had heard or felt the notifications. Stothart said that because people were divided into groups randomly, they could assume an approximately equal number of people had their cell phones, didn’t have their cell phones, or had them on silent — so the researchers were confident in looking at the main differences in performance among groups.

They measured performance by looking at the number of commission errors (someone pressed a key for “3” when they weren’t supposed to) during both blocks of the task and across the groups. These errors are analogous to action slips — so for example, say you’re writing an email to your colleague explaining next steps for a project, and you accidentally type “pizza” instead of “plans” because you suddenly thought about lunch. That’s an action slip. According to Stothart, when they compared the first block of the task to the second block, the probability of making an error increased by 28% in the group that received phone calls. For the group who got text messages, they made 23% more errors than they did during the first half of the experiment. And the group who received no notifications made 7% more errors. “That comes, we think, just from task fatigue,” Stothart said. “So if you’re doing this tedious task for a while, your performance declines regardless of whether or not you receive notifications.”

Were these results statistically significant? Short answer: Yes. Long answer: When the researchers looked at the relationship between block and group, they found that the percent change between blocks was greater for participants who received notifications, compared to participants who didn’t, and this was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. However, they didn’t find any significant difference in errors between people who received phone calls and people who received texts.

So basically, just having your phone near you can distract you and negatively affect your work performance. And this distraction-by-notification might even be comparable to interacting with your phone. Stothart said that in terms of effect size, their results were consistent with those of the distracted driving literature, which has looked at the effects of texting or talking on the phone (interacting) while driving. But what they weren’t able to pinpoint was what was actually behind the distraction.

“We think that the mechanism behind the distraction from knowing that you received a notification is mind wandering, but we haven’t actually looked at that in our study,” Stothart said. “It could just be prospective memory, or knowing that you need to do something in the future, that impacts performance. So the next step for us is to disentangle that — to actually determine if the mechanism behind our effect is mind wandering or something else.”

Regardless, if you want to stave off distraction and be able to perform a task at your very best, the researchers say it couldn’t hurt to put your phone on silent, or hide it so that you can’t hear, feel, or see any notifications. Maybe this isn’t that surprising. But digital distraction has been dubbed, “the defining problem of today’s workplace,” and our phones lie at the heart of that. For how relatively nascent smartphone ubiquity is, the line of research devoted to understanding its effects is far-reaching. You can read about how phones destroy our productivity, how their mere presence distracts us, and how phantom vibrations are a thing. And as we start getting more and more notifications (they’re the next big platform after all), we should be conscious of how the habitual buzz buzzing of our devices affects our ability to concentrate at work.

Google, Yelp, and the Future of Search

Why aren’t things better? This is something that I often feel these days when searching for information on the internet. And it is especially something I feel when I am searching for products where quality matters. This applies to restaurants, tradespeople, and books, for example. In each of these cases, I am looking for not just anything — but something that is good or even high quality. When I search on Google what I often find is a mess of links to sellers of those products and also lots of review sites. But I can also confine my search to something narrower. I can use Yelp, Zagat, or TripAdvisor for restaurants. I can use Amazon to search for books and read reviews even if I don’t purchase there, although the chances are surely high that I will make a purchase if I find what I want.

Not surprisingly then, the business of matching my search behavior with suppliers and information is a big one. There are people who will pay – usually suppliers themselves – for matches that work out. Google’s entire business model is based on that. People search and reveal their intent, giving advertisers who might satisfy that intent a clear in. All Google has to do is, literally, sit back, ask the advertisers to express just how much they are willing to pay for that connection and then connect accordingly.

There was a time, perhaps five or so years ago, when it was hard to imagine anyone being better at Google in finding stuff. But things have changed. Google is great for finding out the date of the Defenestration of Prague without even knowing what that is, or that there were actually two of them. But if I want a hairdresser who will do a decent job or someone to fix my air-conditioner, I’m never feeling lucky and know I’m in for more work in the form of “click – read – back arrow – click again.”

Many startups have realized this problem and have come into the breach to fix things. They offer specialized search (as distinct from Google and Bing’s universal search) which requires (a) consumers know they exist and (b) that their specialized search can actually give consumers the information they desire more efficiently.

Which brings me back to defenestration which, as Google’s luckiest result will tell you, involves the literal overthrow of rulers over the side of a building. But this isn’t “Game of Thrones.” It’s what search competitors hope to one day do to Google, and what some argue Google is doing to them in its own results in the meantime.

This is precisely what the specialized search companies are accusing Google of doing to them. A case in point is Yelp who, along with academics Tim Wu of Columbia Law School and Michael Luca of Harvard Business School have recently tried to measure what this action of Google has done to search consumers.

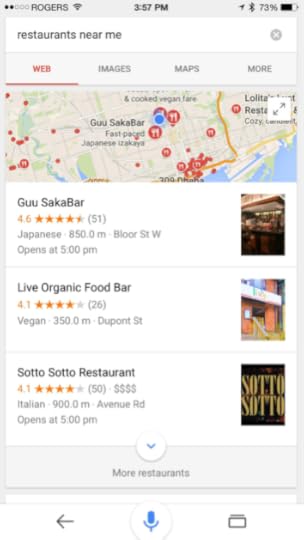

What Wu et al. do is consider Google’s search results for something quite specific like “restaurants near me.” This is the sort of thing someone might do from a mobile phone. Here is what I found when I tried it:

There are several options given but notice that they are ranked by reviews and ratings. What reviews are those? They are reviews that were posted on Google+, Google’s “Facebook killing” social network. What Google has done is taken a leaf from specialized search providers like Yelp and offered consumers search results based on their own specialized search product. In this case, it is Google+ but elsewhere it may be Zagat, which Google purchased in 2011. As I wrote at that time, this acquisition was a recognition by Google that having computers work things out wasn’t enough.

The problem, as Yelp sees it, is Google+ isn’t that good. Indeed, what Wu, Luca, and co. show is that if you replaced those Google+ reviews with reviews from other specialized search engines (including Yelp but there are others), then consumers would click on those results 50% more often. If the goal of Google is to provide people with the best results and if, as is plausible, clicking on them is an indication of that, the researchers have shown that Google is not achieving that goal when it favors its own specialized search product rather than being more neutral.

So what should be done about this? First of all, Google should thank the researchers for providing that information as it offers a guide on how to improve its product. But I suspect Google, famous for its experimentation, already knew that. So that means Google believes that it is better off using Google+ rather than its competitors. That is hardly surprising — but many have argued that Google isn’t quite free in its ability to defenestrate competitors and throw them out of search this way.

The reason is that Google has market power. In the U.S., some 80% of searches are on Google while in Europe and many other places, it is more like 95%. That is a challenge for specialized search engine providers because users of mobile devices, in particular, may not realize what they are being served up. From my screenshot above, it was far from obvious that the ratings were from Google+. The European competition authorities have been examining these practices and some other academics have argued that any favoring by Google of its own verticals should be considered illegal.

So what is the best way forward? Google often says it is providing services in the interests of customers. But this study challenges that, and Google’s defenestrations don’t give us comfort that every review is being given a fair go. Then again, this is the internet and so providers such as Yelp are just some good marketing and press away from being able to get people to bypass Google altogether.

One option is to partner with Google’s competitors. When I do the same “restaurants near me” search on Siri, this is what I got:

Notice that it is different from Google’s results but also tells me where the reviews are coming from (in this case, Yelp). But Apple isn’t running a neutral search engine and has just partnered with one that it believes best suits its own commercial needs.

Thus, we have a classic difficulty in antitrust law in a dynamic environment. Yes, there is currently a dominant firm that appears to be favoring its own verticals rather than being more open. But they are not a fortress. Even when they get thrown off the page, specialized search products can find some ways of reaching consumers. How this plays out is still uncertain.

Perhaps more importantly, we have to worry about what this type of behavior says about Google’s commitment to organizing the world’s information. It is certainly great to bring a human equation into search. But even if it’s fine from an antitrust perspective, for a brand built on neutrality, are the returns to favoring your own verticals really worth it?

July 9, 2015

A Way to Assess and Prioritize Your Change Efforts

Change is the status quo. Companies the world over realize that success depends on their ability to respond to new opportunities and threats as they emerge, and to keep rethinking their strategies, structures, and tactics to gain ephemeral competitive advantages.

As a result, change initiatives have become more complex than ever before, cutting across divisions and functions rather than staying confined to silos. They are global too, often extending across borders to several nations with different cultures.

Companies must set up and oversee change initiatives more systematically than they used to if they want to succeed. They must periodically evaluate projects against each other to ensure that they have deployed the right amounts of resources, people, and attention across competing efforts. Executives must also find ways of catalyzing the discussions that will result in reprioritizing, re-scoping, or retiring change efforts that no longer serve the organization’s objectives.

Accomplishing all that is tough, and keeps business leaders awake at night. Many tell us that they lack tools to help them check whether their change initiatives are likely to work, or to identify the drivers of success and failure. That’s why we decided to reintroduce a change management tool called the DICE assessment, which we have been refining since we first wrote about it in HBR a decade ago, and a version of which is now available for online use.

With the aid of the DICE tool, companies can assess the probability of success of change initiatives early in their lives. By evaluating projects with a standard scoring mechanism and monitoring those scores over time, the assessment helps managers preserve the odds of success.

It also enables executives gauge what is likely to happen if they shift attention and resources between efforts, which helps them make better-informed mid-course corrections. As companies launch new initiatives and redistribute resources, the DICE score, and the likelihood of success, for existing projects will change.

In addition, the scoring system helps turn challenges into conversations; everyone from the CEO to junior team members will gain a standard basis for discussing change initiatives.

The DICE assessment measures four elements that, according to our research, determine the fate of every change initiative:

Duration. The overall project time of the change initiative, or the time between learning milestones. The shorter, the better.

Integrity of team performance. An indicator of the team’s ability to complete the initiative on time based on members’ skills, traits, and experience as well as the leaders’ competencies.

Commitment. The support for, and belief in, the initiative at two levels: The senior management level, and among the directly affected employees.

Effort. The additional workload that affected employees must bear because of the change initiative.

The project team must score each of those elements on a scale from one to four and combine the weighted scores; performance integrity and senior executive commitment have a larger weight than the other parameters. The result will be a score that will range from seven to 28; lower scores are good signs while higher scores indicate trouble.

Having assessed literally thousands of projects, we find that every project will fall in one of three zones, indicating its likely outcome.

1. If the score is lower than 14, it indicates that the initiative has a high likelihood of success; welcome to the Win Zone.

2. A score in the middle (between 14 and 17) shows that there’s concern over the outcome’s likelihood; the initiative is in the Worry Zone.

3. Scores above 17 indicate that it’s unlikely that initiative will be successful; that’s the Woe Zone. Once the DICE score moves into the 21-28 range, companies must accept that the change project will most likely fail.

By using the DICE tool to score change efforts that are under way, leaders can prioritize efforts, identify trouble spots, and modify resource deployments to improve the odds of success. For example, when the CEO of a large Asia Pacific paper manufacturing company took over, he found that around 35 improvement initiatives were under way to increase output, improve operational times, and reduce costs.

Knowing that the company didn’t have the resources to accomplish all those objectives, he sat down with the team leaders, reviewed the projects, and together, they calculated the DICE scores for each of them.

The council finally identified five of the 35 as must-wins over the next two years. Consequently, the team leaders made several adjustments, allocating the strongest team members to, and building in intermediate milestones into the plans for those five initiatives. That way, they ensured that the DICE score for each of them was 10 or less, placing them securely in the Win Zone.

In the case of projects whose scores were in the Woe Zone, the team decided to delay their implementation and reallocated their resources to the higher priority initiatives.

This was not a one-time analysis; the council continued to conduct DICE assessments every quarter. As a result, the company was eventually able to execute most of the change projects on time and under budget.

Using the DICE tool over time changes the way companies manage transformation efforts. Indeed, it will help executives get better at the process, which will ensure that they no longer have to gamble with change.

What to Measure If You’re Mission Driven

My favorite Peter Drucker misquotation is, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Drucker wrote a great deal about how managers should measure performance, but this particular phrase didn’t come from his pen. Instead, his measurement advice was linked to his belief in “managing by objectives,” and above all urged managers to “focus on results.”

The challenge is that all too often, managers haven’t asked what results they ultimately want to achieve. Most of what an organization chooses to measure, and to do, must hinge on this question. I recently had the opportunity to learn from what, in design-speak, we might call an “edge case” of this: the question of what measures should guide the management of a church.

For churches today, the common answer is that growth is the goal, and membership is the measure. Typically, membership is one of the three top-line metrics used to assess a church’s health (along with worship attendance and fundraising levels). Churches fixate on membership on the theory that members are donors. But that theory is at best half true. More important, it mostly ignores the question of what results the church is aiming to achieve.

Consider All Saints Church in Pasadena, CA, widely regarded as one of America’s leading Episcopal parishes. Founded in 1882, All Saints has attracted much attention, including both support and protest, for its long history of progressive stances. The church fought the relocation of Japanese-Americans to internment camps in 1942, launched an AIDS Service Center in 1986, and blessed its first same-sex covenant in 1991. (Disclosure: I attend All Saints, and have consulted pro bono with the organization.)

The Episcopal Church officially reports that All Saints has about 8,000 members. Is that good? Would 9,000 be much better? All Saints Rector Ed Bacon (if you’re not Episcopalian, think of him as the CEO of the enterprise) doesn’t believe those are the right questions. “Sure, we love to see big numbers,” Bacon told me. “But what really makes our hearts beat fast is transformed people transforming the world. Membership isn’t our business. Turning the human race into the human family is.”

It doesn’t help that “member” turns out to be an ambiguous label. Do people become members of the flock when they make financial offerings, or make a habit of attending services—or must they appear on a mailing list, or have formally graduated with a new-member class? I couldn’t get a definitive answer from either the national church or parish administrators. I came away believing that the “member” designation, as Shakespeare wrote about reputation, might be “earned without merit, and lost without deserving.”

Of course, it’s possible to arrive at a consistent way of measuring membership, if that is what matters. Scott Thumma and Warren Bird, in their book The Other 80 Percent, offer a well-researched formula: replace whatever number you are using by tracking your average weekly worship attendance and multiplying by 2.2 (that being the average ratio of congregation size to weekly attendance in Protestant churches). Fair warning: the result will probably be much smaller than your mailing list total.

But All Saints decided to focus on something other than the membership rolls, however well calculated. Instead, its leadership wondered how to gauge the transformation of people that Bacon identified as the real objective. When the All Saints team focused on this, they made the same kind of discovery as many companies that use customer journey maps: people heading toward the same destination don’t always get there by the same path. Not everyone who is on a dynamic spiritual journey—and wants All Saints to be integral to it—is going to pass through the gate of membership. There is, however, one element they do share, and that is engagement.

As Warren Berger writes in A More Beautiful Question, solutions to apparently intractable problems begin when we “challenge [our] own assumptions, reframe old problems, and ask better questions.” This is what All Saints is doing as it replaces the old question—How do we grow our membership?—with a better one: How do we more deeply engage the people we serve?

To establish a baseline of performance on which to build, All Saints has begun using software (from Arena) to assign a score to every activity that signals some level of engagement. Regular attendance at a weekly study group, for example, is scored higher than signing a petition. By combining these scores with other kinds of participation records compiled in the past, the church generates an aggregate engagement score for everyone in its database. This “Spiritual Health Meter” suggests to pastoral staff to whom they could be reaching out more. Jeremy Langill, All Saints’ Director of Youth Ministry, offered the example of an All Saints kid who was consistently engaged in one youth program, but uninvolved in all others. Made aware of this by the data, Langill took note when the girl’s love of board games came up in a casual conversation with her parents. He made a point to tell her about game night, and that served as a pivot point. She went on to participate in a whole range of activities, and grew far more engaged.

Soon, All Saints will add another innovation: an online tool that parishioners can use to make the church aware of their particular talents and interests. Combining insights from this personality inventory with the Spiritual Health Meter, All Saints hopes to target its communications better. A music-lover too busy to read through an entire church calendar might like to get a Netflix-style “recommended for you” message about a forthcoming jazz service. “Christianity is such an incredible journey of self-reflection, of finding a calling in your heart,” Charlie Rahilly, a former warden of All Saints’ vestry (think member of the board), told me. Added Langill, “If we are really honest with ourselves, worship is not just on Sunday morning.”

Engagement is not the only objective All Saints needs to think about; the church must be financially healthy to keep doing its work. But these two objectives are undoubtedly aligned. All Saints’ fundraising data shows with great consistency that, for every additional year a person pledges, their pledge increases by 8%. That’s a rate of return most investors would take in a heartbeat, and it bespeaks the commitment that comes with deepening engagement, not continuing “membership.”

Beneath All Saints’ new understanding of its results is a deeper understanding of itself as an organization. It is too simplistic, as Drucker wrote in his book on managing the non-profit organization, to define enterprises in this sector by what they don’t do:

It is not that these institutions are “non-profit,” that is that they are not businesses. It is also not that they are “non-governmental.” It is that they do something very different from either business or government. Business supplies, either goods or services. Government controls. A business has discharged its task when the customer buys the product, pays for it, and is satisfied with it. Government has discharged its function when its policies are effective. The “non-profit” institution neither supplies goods or services nor controls. Its “product” is neither a pair of shoes nor an effective regulation. Its product is a changed human being.

Some businesses, too, are membership-based and need to focus on engagement. Other businesses might gain an edge in attracting and retaining talent if they were seen as more purely dedicated to engaging their customers and enhancing their lives. Whatever your business, the larger lesson of the All Saints story is that great organizations focus on results. They start with a clear idea of what counts, then find a good way to count it.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers