Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1277

July 3, 2015

7 Myths About Doing Business in Sub-Saharan Africa

It’s 2015, and by now even latecomers among multinational corporations have decided to include African countries in their emerging market portfolios. However, many companies are not making the most of the Sub-Saharan Africa opportunity because of misconceptions about what it takes to succeed in the region.

Sub-Saharan Africa refers to countries below the Sahara desert, such as Kenya, Angola, Nigeria and South Africa. (Many companies separate their Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa operations because of strong cultural, economic, and linguistic differences between the two regions.)

Leveraging a combination of economic analysis and forecasting, on the ground interviews with policymakers, and a dialogue with executives responsible for Africa strategy and operations, we have identified the seven most prevalent myths that skew companies’ perceptions of doing business in Sub-Saharan Africa—and what executives can do to overcome them.

Myth #1: There is no competitive urgency to build a presence in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Sub-Saharan Africa is already a competitive market place. Whenever I travel to an African city, I marvel at the dynamism of business activity taking place on the ground. Asian companies dominate many sectors, while African companies are expanding their footprint and market-leading Western multinationals are also prominent. All are vying for a share of the continent’s growing consumer class and government spending.

As Sub-Saharan Africa continues its strong growth trajectory, competition will only intensify. Executives should build step-by-step long-term expansion plans, but avoid delaying entry as securing market share will become increasingly difficult.

Myth #2: Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth is all about natural resources and consumer spending.

The popular perception is that many African markets are all about energy. But, for example, our research found that oil and gas only made up 11% of Nigeria’s GDP in 2014, compared with 20% for construction.

Many companies are attracted to African markets because of fast-growing consumer spending—but greater purchasing power is also driving economic diversification. Consumer demand for new products and services is creating opportunities across a wide range of sectors. For example, as they want better public services and infrastructure, investment in industries such as healthcare and construction accelerates.

Myth #3: Fast economic growth means quick returns.

Many executives hope to compensate for sluggish growth in the Eurozone by making quick returns in Africa. While Africa’s economy is on track to be worth $3 trillion by 2025 (from $1.3 trillion today), benefiting from Sub-Saharan African growth is a long-term game. The region’s development will likely span several decades. Executives should commit to the region knowing that while top-line growth is likely to be strong, bottom-line returns on investment will take years to materialize.

For example, GE is already reaping the rewards of its long-term approach. It has been present in Sub-Saharan Africa for many decades and established local offices to advise governments of countries that are in the early stages of development on infrastructure projects, such as building railways and hospitals. This required a large upfront investment, but it has generated demand for the company’s products.

Myth #4: Sub-Saharan Africa is too volatile and unpredictable.

Like all emerging markets, Sub-Saharan Africa is exposed to risks. Companies need to be prepared to navigate volatility without losing sight of the fundamentals that make the markets attractive for them. For example, Nigeria has been the number one opportunity market for most multinational corporations in the region. But executives turned attention toward East Africa in mid-2014 when Nigeria was affected by fears over Ebola and tumbling oil prices slowed growth. They were therefore surprised by the country’s peaceful elections, which brought an opposition party to power. And they were reminded of East Africa’s long-standing security risks when Kenya experienced a brutal terrorist attack.

Such reversals and disruptions are unlikely to subside, but none of them fundamentally reduced the opportunities for MNCs in Nigeria or Kenya. Executives should carefully assess the level of volatility to understand if a change in strategy is really necessary, or whether a short-term contingency plan is the best solution.

Myth# 5: Sub-Saharan African markets can be prioritized merely by using data.

Many companies often don’t know which of the 48 countries in the region hold the largest opportunities for their business. Data on market sizes and product categories are largely non-existent or provide little information about the market’s potential.

For example, if a company wants to sell toothbrushes, it would be insufficient to assess the opportunity by only looking at numbers for toothbrush sales. These data points would substantially understate the potential size of demand, because they would not reflect the likely high numbers of people who will begin to use toothbrushes for the first time in the years to come, as they become more health-aware.

Macroeconomic indicators like GDP size and consumer spending are also insufficient measures of market conditions. For example, Angola’s market size and spending potential look attractive on paper; however, the market’s operating environment makes it very challenging to capitalize on these opportunities.

Executives should take a broader approach to finding the best markets for their business. They need to combine available data and forecasts with a thorough qualitative analysis that looks at the operating environment of each market.

Myth #6: Relying solely on distributors is a sustainable Africa strategy.

Many companies are reluctant to put feet on the ground before the market can fund them. But proximity to the market allows a company to adapt products and marketing strategies to local needs. For example, when Nigeria suffered its first Ebola cases and Boko Haram terrorist activity began to rise, consumers shifted to e-commerce to avoid shopping in public places. Companies with representatives on the ground were able to rapidly identify and adapt to this shift in consumer habits.

Companies should focus on putting at least one representative on the ground in priority markets to gather market intelligence, manage distributors, and build relationships with the government.

Myth #7: South Africa is the natural hub from which to manage a Sub-Saharan Africa business.

Many companies locate their African headquarters in South Africa as they usually already have a presence there for historic legacy reasons since South Africa is more integrated in global markets than other African economies. However, South African businesses are sometimes regarded with a certain amount of resentment in many countries in the region. Moreover, with scarce and expensive talent and increasingly unreliable power, South Africa does not offer a particularly welcoming business environment.

Leading companies are already beginning to think creatively about how different cities might be better suited to different priorities. For example, GE re-located its HQ from Johannesburg to Nairobi, because the latter is known for benefiting from a strong talent pool and strategic geographic location.

Companies should accelerate their expansion into Sub-Saharan Africa as the region continues to grow, becomes increasingly competitive, and is unlikely to be derailed despite sporadic volatility. To succeed in the continent, executives must develop long-term plans while remaining prepared to weather short-term disruptions.

An Experiment in Enlivening Stagnant Teams

People make big, difficult changes for two key reasons — to reap rewards and to avoid pain.

But what about entire teams that are deeply entrenched? How do you shake them up? As an HR executive, I’ve found that you sometimes have to show them future rewards or pain, especially if they’re comfortable and successful now. Though you may be able to see the writing on the wall, it can be tricky to get them to see it. That’s where data-driven experiments come in. They help shine a light on the opportunities and risks ahead, which can motivate stagnant teams to start thinking and behaving differently.

Here’s an example. In a prior role, I was heading up HR at a fifty-year-old company. Though we were in tech, the average age of our workforce was approximately 47, and turnover was extremely low. In fact, it wasn’t unusual for employees to celebrate 30 or 40 years of service. That set us apart from most other Silicon Valley firms, in both good and bad ways. The company was stable largely because of its healthy culture and loyal employees — but I worried about its future. What would happen when large portions of intact teams retired? Where would the knowledge go? Also, the innovation and speed of the R&D teams had begun to decrease. Were these factors linked to tenure, too? I thought they might be.

The analysis: HR and the R&D leaders looked for correlations between length of service and levels of engagement, innovation, and productivity on teams. HR also did predictive analysis for retention, creating a heat map of sorts to see where we had concentrated areas of risk.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

We found that we had a few teams that had been intact for more than eight years without a single new hire. They had, on average, lower engagement scores than teams with more recent changes in membership. (We typically saw a 5 to 15 point difference in surveys.) They also had longer product development cycles, which potentially signaled lower productivity and slower innovation. What’s more, the stagnant teams hadn’t made any plans to add new members. Anywhere from 20% to 50% of their members would be eligible to retire at the same time — in just three to five years. I was worried.

Even though we were seeing correlation but perhaps not causation, I believed there was enough of a link to do a little test.

The test: For the summer, we brought in an undergraduate or graduate intern for each team that had gone more than eight years without an infusion of fresh blood. We encouraged larger teams to take two or three interns, as we didn’t want the new voices to get drowned out by the more experienced team members.

Our hypothesis was that with hungry, talented individuals now on board, these teams would learn how to teach others again. They would need to respond to questions about why things were done in certain ways. Through their mentoring, we hoped, the more seasoned members would also begin to spot opportunities for improvements that they wouldn’t otherwise see.

The results: As hypothesized, engagement went up — by eight points, on average. In a post-intern survey, team members said they had more energy and reported greater group participation in problem solving and knowledge sharing. And about half the teams elected to convert their eligible interns into regular full-time employees upon graduation — they loved having fresh eyes and minds in their midst. These hires helped mitigate the risk of talent drain a few years out. Because the teams had to educate their new colleagues, they started doing a much better job of documenting core processes, which of course improved knowledge transfer.

They also thought they became more efficient and innovative, specifically in R&D — though it was hard to gauge direct impact, since the cycles for product development remained relatively long. In any case, the fresh questions and the eagerness to solve problems and collaborate across teams were believed to contribute to better quality. Team leaders consistently saw an increase in discretionary effort, which they felt led to better problem solving.

The value of “seeing is believing”: The team analysis pointed me to areas of the organization that needed a bit of a recharge. The key to driving change in behavior was to highlight future rewards and risks — and to disrupt current patterns — in ways that didn’t threaten the teams personally. They’d have the interns for a summer, and if they didn’t see any benefits, that would be the end of the experiment. Even so, the change wasn’t completely accepted out of the gate. I did have to agree to fully fund all the interns from the HR budget the first year. To do this, I had to delay other initiatives in my function, but I felt the risk/reward ratio was worth it. By year two, we knew we’d made an impact when the teams set aside funds in their own budgets for new interns.

The lasting impact: The teams absorbed some of the interns’ excitement and curiosity, which led them to challenge their own thinking. As a result, they now have more innovation in their pipelines. The interns that were converted are still there today — two years later. The intern program continues, and the energy during the summer is palpable.

Who doesn’t love fresh eyes and passion? Once the teams had that energy, they wanted to keep it. All we had to do was share the data and the rationale for change, test a theory, and see if we got the desired results. To keep the change going, we knew it was important to continue testing impact, gauging acceptance, and looking for new improvements to make. That allowed the team leaders to tweak the program — it gave them a feeling of ownership.

If you think you need to lead a team through change, look to the data for future risks and rewards. Then create nonthreatening experiments that give the team a taste of the success they’ll enjoy if they make the change. Keep testing — and keep sharing what you learn. Once the team is in there, trying the new path, you’ll gain momentum. And if it’s the wrong path, that’s good information to have. Try another.

July 2, 2015

The White House Selfie: The Visual Web’s Latest Victory

The White House announced a policy change this week, allowing people on tours of the historic residence to take photos and post them to social media during their visits. Selfies (but not selfie sticks) are now allowed. In part, this is a practical move. As cameras have become smaller and more discreet it’s become easier to sneak in a shot of a portrait, or some White House china, or a selfie — even if it was officially prohibited.

I was at the announcement and I got in on the now-legal act.

Watching @brilliantartistry line up a shot. #whitehousetour

A photo posted by Perry Hewitt (@perryhewitt) on Jul 1, 2015 at 8:27am PDT

Before you assume this new policy just means that the First Dogs’ social presence is about to skyrocket, look a bit closer. It’s actually a teachable moment for brands. The White House could have tried, like many brands and institutions do, to ignore or deny our new reality around visual content.

What is that new reality? Roughly two-thirds of Americans now own smartphones, and the camera is a core feature harnessed by third party apps from Asana to Zillow. Almost half of Millennials use their smartphone camera at least once a day — and at least a few of those aren’t selfies. More than 1.8 billion photos appear on social media each day. That means roughly a trillion photos were taken and shared socially in 2014. More than 50 billion photos have been pinned on Pinterest. Photo sharing is now a deeply ingrained daily human behavior. It’s become so commonplace to take photos of what we’re eating that restaurants are optimizing their tables and food presentations for Instagram, and home good manufacturers are designing plates that double as photo backdrops.

Short-form video isn’t far behind as a new norm. In just one example, Facebook users now view 4 billion videos per day.

All of which is to say: You can’t change or fight this. Logistically or culturally. So the White House stopped trying to and instead embraced the trend toward sharing visuals. The lifting of the ban presents an opportunity to engage visitors during their visit, enlist them in storytelling, and reach their expanded social networks. To take full advantage of the laxer rules, the government’s social feed will collect, curate, and amplify visitors’ content. The White House is doing what we tell brands to do all the time: embrace this world to validate and strengthen your connections to your consumers. Use visual content to engage different voices as brand storytellers. They are moving their marketing strategy from create and control to influence and leverage.

Brands have been told to do this for some time now, but they have a hard time with it, for two reasons. First, if brands want to explore making their own visual content it can be hard to make the switch technically. This often means acquiring new technical capabilities and platforms. Digital asset management systems originally designed for a limited number of approved photos and metadata now have to capture, store (or link), and tag a broader array of assets. New software and training are needed to create visual content using tools like Photoshop or SaaS solutions like Canva for business. To evaluate performance of visual content, new technology entrants like Ditto and Curalate have emerged to help brands identify where they appear in photos and track engagement. Existing analytics platforms are also evolving, finding ways to track impressions and sentiment. Marketing and IT organizations are partnering to create requirements, purchase, and deploy these technologies. But it’s more than just a technical leap – brands also need the right people in place to curate their social media conversation and engage with customers generating content on their own.

Two, it’s a big cultural shift to let go of complete control of the visuals being created about your brand. For some brands, visual content just wasn’t taken seriously in an alphanumeric culture. Broad adoption of visual content as a legitimate medium requires a shift in mindset. Throughout the 20th century, publications conveyed the seriousness of their enquiry through tightly-condensed lines of text. Serious publications limited illustration, and eschewed photography altogether. Brands that held these biases need to shift their mindset and build new visual content competencies, thinking in pictures when they’ve previously served up paragraphs.

One important caveat in all this change: This democratizing shift in who makes visual content does not signal the end of expertise, as some fear. Just because I can snap an artsy, filter-enhanced pic that gets re-grammed doesn’t mean professional visual artists are going away — quite the opposite. Just as desktop publishing software in the 1980s did not turn us all into great graphic designers, the availability of photography emphasizes, rather than masks, the profound difference that a creative eye and a skilled hand make.

New behaviors brought by the internet, like the rise of visual content, have us in a state of constant change. Smart brands are finding ways to see change coming, calculate the risk and opportunity it presents, and advance their strategy. Leaders will differentiate by thinking beyond tools and technology, and actively adapting culture and policy to help their audiences put themselves in the picture, like the White House has.

Figure Out Your Manager’s Communication Style

Effective communication takes a deft touch when you’re managing up. If your attempts to persuade are too obvious, they may not succeed. Yet you need to be deliberate in your approach.

As you engage with your boss in everyday activities, try to identify the messages behind her speech and behavior. The words and deeds matter, of course, but the values that underlie them often mean more. Listening with a keen ear and observing with a sharp eye can make all the difference in understanding, not just labeling, your manager’s communication style.

Consider the statement “My door is always open,” which many bosses make to their direct reports. That seemingly transparent sentence can have a variety of meanings. Here are three examples:

Rebecca:

When she says, “My door is always open,” Rebecca means it literally. To foster honesty and camaraderie, she wants people to feel free to approach her in person at any time. It invigorates her when a direct report has an idea and spontaneously pops into her office to share it. When a problem arises, she wants to hear about it immediately, because it reassures her that everyone is working as a team. She bristles when people who come in to speak to her close the door behind them. Indeed, she worries that colleagues will see a shut door as evidence of hypocrisy. If Rebecca must talk with someone in complete privacy, she reserves a meeting room.

Raul:

Raul’s open-door policy is one that he expects people to observe in spirit, not in absolute terms. The door to his office is open 90% of the time, but when a deadline is imminent, he shuts it so he can concentrate, especially if he is writing. He wants people to see him as easy to approach and “always available,” but he views e-mail and team meetings as legitimate ways for people to reach him. If someone considered him a hypocrite for shutting his door once in a while, Raul would think that the person lacked common sense.

Janice:

Janice works in a cubicle with low walls, as do all of her direct reports, so she doesn’t even have a door. To her, an “open door” is merely a metaphor for how colleagues work together. She doesn’t want people to fear making mistakes, even in front of her. But she also places a high premium on giving folks the mental space to do their work quietly and to consider proposals deliberately before acting on them. She wants her direct reports to share novel ideas but expects them to submit those in writing before asking other people to react. To Janice, an open door does not mean an “instant response,” a phrase that she often uses when describing slipshod work.

As varied as these “open door” interpretations are, at least Rebecca, Raul, and Janice give their employees something to go on. Some managers don’t even have an explicit policy about how—and how often—to communicate with them.

Excerpted from

20-Minute Manager: Managing Up

Organizational Development Book

Harvard Business Review

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Whatever your manager’s preferred style of interaction, you’ll probably need to do a little investigating to figure it out. Start by asking yourself these questions:

Is my manager a listener or a reader? Listeners want to hear information first and read about it later. Readers prefer to see a written report before discussing it with you.

Does she prefer detailed facts and figures or just an overview? If she thrives on details, focus primarily on accuracy and completeness; if she prefers an overview, emphasize the clarity and crispness of the main idea.

How often does she want to receive information? Your manager may always want to receive updates at specified junctures or she may have different thresholds for each project, such as daily reporting on critical endeavors and periodic updates on secondary initiatives.

Every exchange of information with your manager has implications for productivity. These tips will help you be more efficient:

When discussing deadlines, use specific language. Pinpoint a certain date—even a specific hour, if appropriate. Avoid vague commitments like “sometime next week,” “ASAP,” or “as soon as we can get to it.”

Be honest about what you can and cannot handle. When you commit to an assignment, clearly identify what resources you need to get the job done.

Explicitly identify your objectives each time you communicate with your manager.

Ask questions to clarify what you don’t understand. Inquire about opportunities for follow-up in case you think of other questions later.

This post is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press book Managing Up (20-Minute Manager Series).

A Framework for Strategists Assessing Emerging Markets

Steven Moore

Many companies start their search for global growth in an alphabet soup of emerging-market groupings such as the BRIC, CIVETS, MINT, Next 11, and so on. Is that smart?

Not really, suggests our analysis. There are several flaws in using such acronyms as the basis for entering overseas markets.

Country groupings tend to conceal more about a nation’s growth than they reveal. For instance, ever since Goldman Sachs coined the term BRIC, China and India have pulled ahead of Brazil and Russia, whose growth fell below the group average between 2001 and 2013. Likewise, Nigeria is the powerhouse among the MINT nations while Mexico’s performance may make investors question the rationale for its inclusion.

Many acronyms are rooted in the expectation that in these emerging markets, there is large, and fast-growing, demand for products and services. However, the sources of demand in each country differ, which will affect your strategy. For example, among the BRIC nations, consumption has played a key role in Brazil, India, and Russia, but in China, fixed investment was the driver until recently. As a result, some consumer-facing companies would do well to enter Brazil or India before targeting China.

Business growth can also depend on factors such as the availability of talent or scarce raw materials that influence, say, a company’s innovation capabilities or its ability to manufacture cost-effectively. However, all the popular acronyms only indicate the ripeness of countries’ consumer markets.

Similarly, when companies wish to manufacture overseas, they will encounter wide variations within the groupings. For example, the MINT nations may appear to be attractive locations, but they differ significantly. Mexico’s growth comes mainly from a growing labor force; Indonesia’s and Nigeria’s from capital productivity; and Turkey has seen positive contributions from the labor force, but negative contributions from capital. Those trends dictate different choices for a labor intensive retailer (who should choose Mexico or Turkey), a capital-intensive construction company (pick Indonesia or Turkey), and a high-value manufacturer that needs skilled labor (Nigeria may be the best bet).

Finally, operating conditions differ significantly within the country groups. The Next 11 is supposed to consist of high-growth economies, for instance, but the political instability in its member-countries such as Iran and Pakistan make the abbreviation an unhelpful guide for business. In fact, the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business lists show that the rankings of most emerging economies covered by acronyms and abbreviations have worsened. Between 2001 and 2014, for instance, Mexico’s rank slipped from 35 to 53; Bangladesh’s from 65 to 130; and Nigeria’s from 94 to 147.

Moreover, the differences between the countries have grown over time. Thus, most groupings may be valid only in the short run.

Having said that, it is also true that executives need help managing their globalization gambits. Every company requires a way of calibrating its strategy to the growth drivers in its industry, and developing a geographic value map. We call that process the A-B-C (which stands for Analyze-Benchmark-Calibrate) of developing a globalization strategy. The steps are:

Analyze the half-a-dozen key factors driving business growth in your home market and identify the specific economic indicators that represent them in the countries you are considering. Use a mix of supply and demand factors, but ensure they are all specific to your business model.

Benchmark all the economies for which reliable data are available. If a large number of indicators affect your business, weight them according to their importance. The resulting groupings may not trip off the tongue as easily as do some acronyms, but they definitely will help ensure growth.

Calibrate your geographic strategy by scanning the horizon every year. The risk of coining a list that sticks in your memory is that they quickly become out of date.

When companies re-evaluate their strategies using the A-B-C process, the results are often surprising. Consider, for instance, a healthcare company looking for double-digit growth in an emerging market. To it, the three most relevant indicators of a country’s attractiveness are disposable incomes, the size of the population over 65 years, and latent demand. If the company were to analyze the data for those parameters, as we did, it will find that China, Czech Republic, India, and Poland are its best bets.

Similarly, for a construction company looking to expand steadily into an emerging market, its drivers will include the growth rate and the extent to which the economy is urbanizing as well as the ease with which it can import and transport raw materials around the country. When we studied that country-level data, we found that the company should choose from amongst China, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria — not exactly a standard grouping.

Likewise, an insurance company seeking to create its geographic value map should consider factors such as the size of the middle class, the maturity of the capital markets, and the extent to which there is a local culture of saving. If it were to identify the top performers across those dimensions, China, India, Malaysia, and South Africa would be great prospects. In all three cases, by the way, we normalized the data for the economic indicators to generate a consistent basis of comparison and identified the markets by calculating a weighted average across all the indicators.

Globalization decisions are undoubtedly complex. The challenge is to avoid conventional wisdom and to develop a company-specific world view of which economies to invest based on the growth drivers of your business. A-B-C may not be the snappiest abbreviation in the world, but it is a simple and sound guide for your globalization strategy.

Tesla Is Betting on Solar, Not Just Batteries

Tesla’s Powerwall storage system is not a radical innovation, and it is not the first battery for energy storage on the market. But, as Elon Musk surely understands, it is not always the best technology that wins the innovation race. Rather, it’s often the one that best fits with existing dominant technologies, so that the success of the two becomes interrelated. And the Powerwall is the first battery on the market to provide a solution to solar energy storage that is simple to use, easy to install, relatively inexpensive to maintain, and more aesthetically appealing than existing home batteries and storage systems, such as small diesel generators. Powerwall therefore has all the characteristics needed to succeed in this market. At least as long as the technology it is tethering itself to – solar – succeeds as well.

The advantage of Powerwall will be greater for households and business customers who have already installed solar panels and perhaps own a Tesla electric vehicle. It would allow energy produced during the day to be stored for use in the evening and early morning (including for vehicle charging). This technical interdependence with solar is something that Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and chairperson of SolarCity, is trying to exploit by working in close collaboration with his cousin Lyndon Rive, CEO of SolarCity, the largest rooftop solar installer the US. In this way, Tesla’s batteries could become associated with an established technology (solar power) so that the two technologies start spreading together, ultimately becoming a new technical standard adopted by the majority of households and businesses.

To support this strategy and to encourage adoption, both companies have planned not only to work together but to scale up their activities in order to control costs and make solar more affordable to their customers: Tesla has announced the opening of a $5b Nevada plant, jointly with Panasonic, and SolarCity has announced the same strategy for the large scale production of solar panels in Buffalo, New York state. SolarCity’s effort, alongside the heavily subsidized production of rooftop solar from China, will help to make the energy source more affordable, meaning there will be more demand for storage solutions like the Powerwall.

Despite the potential benefits generated by the complementarities and the technological interdependency with solar power, Tesla’s Powerwall strategy includes risks. The company may become critically dependent on the successful development of solar power, but is solar worth the bet?

In recent years, solar has been part of an increasing trend together with other renewable sources such as wind, hydro, and nuclear. However, whether solar has won the battle against alternative clean energy technologies and against fossil fuel is still highly debatable. Despite the rapid price reduction of solar panels, newly available, increasingly affordable shale gas has reduced dependence on crude oil, leading to a significant drop in both demand and price of other fossil fuels such as coal. This might slow down the uptake of alternative energy sources. In short, the shale gas revolution has introduced significant uncertainty into the future energy scenario and the adoption of solar technology is not immune from it.

Of course, the success of solar is not the only factor that will determine the Powerwall’s success. Powerwall batteries are also subject to the uncertainty about their performance in comparison with other battery technologies, and it is also possible that technological advances that could make its components obsolete.

Tesla will also have to contend with government incentives designed to spur the adoption of solar power. Net metering policies in most US states let homeowners sell excess electricity back to the utilities. In the states that adopt such regulation, the advantage of using Powerwall for storage purposes will depend on the difference between the profit consumers can make by selling energy to the grid at subsidized prices during day time and the savings that come from avoiding having to buy from the grid at night time. If energy can be sold back to the grid at a high price, it will be more attractive than energy storage for homeowners with rooftop solar. That is the reason why the 7KWh battery (priced at $3000 by Tesla) is not going to be offered by SolarCity.

Still, there are clear advantages for Tesla in entering the market for batteries for domestic and commercial energy storage. It allows Tesla to further capitalize on its knowledge and competences developed in automotive batteries for electric vehicles.

The battle for the domestic storage market has only just started and Tesla has selected a powerful ally in the solar photovoltaic (PV) sector, but both technologies are vulnerable to threats from within and outside their industry, and the reliance on solar’s success might prove a risky bet for Powerwall’s future dominance of the market for storage systems.

Should solar not become the future, Tesla’s Powerwall line won’t necessarily be doomed. The company might just have to pay a conversion price to fit within new standards. However, should it be successful, Elon Musk would not only benefit from the sales of Powerwall (and indirectly from the sales of PV produced in Buffalo by the company he is chairman of) but also from increased sales of Tesla’s own electric vehicles, the company’s core product. The latter would benefit from an easy to use recharging facility, zero emissions, and possibly a cheaper alternative to the pump. As to the question whether solar is worth the bet, overall the answer for Musk seems to be at least in the short run that it is.

The 5 Paradoxes of Digital Business Leadership

“Leadership” has historically referred to “industrial leadership” – the managerial styles and structures that served industrial firms well for a century. But the leadership of digital businesses in the post-industrial age is fundamentally different and is defined by five paradoxes. Understanding them can help digital leaders identify and develop the capabilities they will need to transform the firm from a traditional to fully digital enterprise.

To lead this transformation, they must:

1. Radically innovate while optimizing operations. Operational excellence is a competitive requirement for any organization, and digital leaders have a key role in applying new technologies to achieve it. However, at the same time they must redesign their business models in order to compete in a digital world.

This requires two broad sets of skills: the ability to focus on what the firm does today and optimize its current execution, and the ability – and courage – to challenge the firm’s current model by answering fundamental questions such as “How will digital technologies change how we create value for our customers?” “What is the ‘job’ our customers are tying to do?” and, more broadly and disruptively, “What business are we really in?”

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

2. Compete in sprints while delivering long-term value. In a digital world, transient opportunities arise abruptly and frequently and must be exploited as they appear. At the same time, the ability to deliver agile, instantaneous responses must be coupled with an ability to build lasting relationships with customers based, for example, on purchase history and how the product is used.

As conventional products become increasingly smart and connected, relationships with customers are becoming ever more service-based and open ended. Thus, digital leaders must effectively change the interaction model with customers from the infrequent and random encounters in the analog world (a store customer meets a sales rep with no knowledge of prior purchases or the information collection process) to targeted digital business “moment exploitations” (an online customer receives personalized and updated offers or service that take online interactions, previous purchases, and digital product usage data into consideration).

3. Integrate external partners while operating as a single entity. The nature of digital offerings means that the cost of incorporating external digital innovations, for example off-premises (cloud-based) digital services, will often be less than creating and developing these solutions internally. However, customers seek seamless, integrated offerings that appear to come from a single provider.

Digital leaders must therefore be able to adeptly integrate (and disintegrate) both internal and external digital offerings in a way that presents a single, unified offering to customers. This has important implications for business design as it relies on the ability to build and run agile digital-partner networks – a leadership capability that didn’t exist in the industrial era.

4. Recognize that providing immediate digital value plays a large role in sales but that more value is delivered over time. Traditionally, the sale — the exchange of goods for payment — has been the defining transaction between company and customer. Though additional products may have been offered later, the purchase decision was based on the existing product at the time of sale. Product development typically occurred before the sale, with a clear line between it and sales. In digital business, the initial sale is more akin to establishing a platform for long-term value delivery as digital product characteristics are typically enhanced and customized over an extended period. Cars, for example, will increasingly be modified by software upgrades after sale.

For digital products, there increasingly is no single defining moment at which the product is exchanged for a price. By nature, a digital product establishes a long-term relationship with the customer, during which product characteristics are enhanced and individually customized, and payment is accordingly modified. In order to create this open-ended customer relationship, digital business leaders must be able to articulate the value that drives the initial transaction – while at the same time supporting the continuous development model that provides indefinite new value.

5. Provide technologically enabled offerings while focusing on value, not technology. Depending on the digital density of an industry, the amount of technology integrated into its products may vary. Nevertheless, the blurring of the digital and physical worlds that defines digitalization will always add a significant technology component to products.

However, if a product is to succeed with a wider audience, the integration of technology must be seamless and virtually invisible, as customers generally do not see technology as a goal in itself, but seek improvements in what the product can do for them. Consequently, digital leaders must develop a deep technology understanding. However they must use this understanding to create offerings that, while increasing products’ technological complexity, simplify the user experience and generate increased value.

As the paradoxes illustrate, digital business leadership is a complex and contradictory undertaking. Senior executives can address the challenges with partial measures, such as creating the position of chief digital officer or forming cross-functional and multidisciplinary digital business teams that include IT professionals and business peers.

However, executives must resist the temptation to act precipitously. Instead, they should take a structured approach and use the paradoxes to define the competencies necessary over the long term for building digital businesses, and leadership.

Debriefing: A Simple Tool to Help Your Team Tackle Tough Problems

Your team has identified an important goal to hit, challenge to be addressed, or opportunity to be pursued. You call a meeting or two, set objectives, put a plan together, and start to execute. Everything looks good on paper.

But then your plan starts to hit some snags. Certain objectives are harder to meet than you had hoped. Critical players get pulled onto another project. Timelines take longer than you had anticipated. The impact is smaller than you need it to be.

At this point you can either (1) keep muddling through with your fingers crossed, hoping that things get better (2) abandon the plan altogether or (3) recalibrate and jump back in. In my experience, number one never works, and number two doesn’t help in the long run. Only number three can drive the growth of your team and company over the long term. This is where debriefing, a simple and powerful tool, comes in.

Debriefing is a structured learning process designed to continuously evolve plans while they’re being executed. It originated in the military as a way to learn quickly in rapidly changing situations and to address mistakes or changes on the field. In business, debriefing has been widely documented as critical to accelerating projects, innovating novel approaches, and hitting difficult objectives. It also brings a team together, strengthens relationships, and fosters team learning. In my experience, teams who debrief regularly are more tight-knit than those who don’t. They communicate more effectively across the board. They are more aligned on values and purpose. In essence, they become higher performing teams.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Leading Teams Ebook + Tools

Leading Teams

Ebook + Tools

Mary Shapiro

39.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

So what does a debriefing look like? More than a casual conversation to discuss what did and didn’t go well, debriefing digs into why things happened and explores implications for the future. Accurate understanding and knowledge is placed ahead of egos. People participate with a desire to truly understand root causes of their successes and failures so they know what to repeat and what to change. The conversations may be uncomfortable, but participants realize that the discomfort of getting things out on the table is minimal compared to the pain of making the same mistakes again.

When and how often you want to hold debriefings depends on the nature of your work. In 2011, when the NY Giants won the Super Bowl, they held debriefings 1-2 days after every game to understand what did and didn’t work. Many software development teams hold mini-debriefs every morning to review yesterday’s progress and today’s goals—and longer debriefs every month or two to understand larger project wins and challenges. As a general rule, I tell teams to start with one debriefing a week to figure out what works best for them. You also may want to hold one after significant events or project milestones. Too many or too few can both diminish the value of debriefing, so you have to discuss appropriate frequency with your team.

A productive debriefing can last for as little as 10 minutes or as long as several hours, depending on the size and scope of the project or event that’s being debriefed. I’ve found 30-60 minutes is optimal for most debriefing meetings. Here are four steps to conduct an effective debriefing:

1. Schedule a regular time and place.

The key here is to make the debriefing expected, so everyone adopts a learning mindset before the activity at the center of the debriefing even takes place. When people know they’re going to be getting together afterward, and can anticipate the general structure of the conversation, they’ll begin gathering insights in advance. Eventually, the more you debrief, the more effective and efficient the whole process becomes.

2. Create a learning environment.

Expectations should be set so people know that learning is what’s most important — not one’s position on the org chart. The expression the Army uses is: leave your stripes at the door. The most senior leaders in the room set the tone. When they make themselves vulnerable and admit to errors, it gives everyone else permission to do so too. Along with this, the other key aspect of creating a learning environment is no pointing fingers. The results, both good and bad, should be considered team results, recognizing that everyone had a hand in creating them.

3. Review four key questions.

This is the heart of a good debriefing. Ask all participants come to the meeting with thoughts prepared on these questions:

What were we trying to accomplish? Every debriefing should start by restating the objectives you were trying to hit. The group should have agreed on clear objectives prior to taking action in the first place. If there’s lack of clarity here, the rest of the debriefing will be of little value because you won’t know how to judge your success.

Teams often struggle to set clear objectives if the initiative is at a conceptual phase. Push yourself to set these early on to pave the way for your team’s learning and rapid improvement.

Where did we hit (or miss) our objectives? With clear objectives, this is a pretty straightforward conversation as you either did or didn’t hit them. Review your results, and ensure the group is aligned.

What caused our results? This is the root-cause analysis and should go deeper than obvious, first-level answers. For example, if you were trying to generate fifteen wins and only generated five, don’t be satisfied with answers like we didn’t try hard enough. Keep digging and ask why you didn’t try hard enough.

For example, were you overwhelmed because the team hadn’t prioritized work? Were incentives misguided so people didn’t feel motivated to try harder? Was the task too complex so people gave up too easily? There are many reasons why people don’t try hard enough. If you don’t get to the root cause, you can’t create actionable learning for the future.

An effective tool for root-cause analysis is “5 whys.” For every answer you give, ask why that’s the case. By the time you answer the question five times, you’ve usually uncovered some fundamental issues that are holding you back.

What should we start, stop, or continue doing? Given the root causes uncovered, what does that mean for behavior or plan changes? Specifically, what should we do next now that we know what we know?

4. Codify lessons learned.

Make sure you capture lessons learned in a useable format for later reference/use. At a minimum this is taking notes and distributing them to the members present. Other methods can make the information more readily available to a broader audience. For example at Procter and Gamble, R&D professionals submit Smart Learning Reports (SLRs) to a database, based on monthly research lessons learned, that can be searched by anyone in R&D worldwide.

The biggest hurdle to debriefing is merely starting it, especially if you have a culture where this sort of open communication isn’t the norm. If that’s the case, pick some small projects and an intimate team to pilot the process. Once you begin to do it, you quickly realize how natural and intuitive it is. We experimented with some stuff, we talked about what worked and what didn’t, and then we used that learning to get smarter about our next set of experiments etc. That wasn’t so hard.

The most powerful change processes are usually the simplest.

July 1, 2015

Why Overtime Pay Doesn’t Change How Much We Work

Kenneth Andersson

America works too much. Half of salaried workers report putting in at least 50 hours a week, and surveys of white collar professionals report even higher figures. Long hours deplete our ability to make good choices and make it harder to fit in a full night of sleep. As a result, workers are less productive, less healthy, even less ethical. Long hours also make it harder for women to advance into leadership roles.

And in exchange for all this work, most workers never see any overtime pay.

Earlier this week the Obama administration announced an executive action aimed at changing that, by making more workers eligible for overtime pay. “Right now, too many Americans are working long days for less pay than they deserve,” wrote the President.

Supporters hope the rule change will either increase workers’ pay, or at least preserve it while decreasing their hours worked. Firms can choose to keep workers’ hours as they are now, but pay them time-and-a-half for overtime hours, thereby increasing wages. Or they can opt not to require overtime, in which case their employees work shorter days, meaning their hourly compensation increases.

Unfortunately, these aren’t the only options. In practice, the reform’s impact on wages will be less than one might expect, and its impact on overwork may be negligible.

Right now, nearly all hourly workers are eligible for time-and-a-half pay for time worked beyond 40 hours a week. Salaried workers are often exempt, either because of how much money they make or the sort of work that they do. The rule dates back to the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in 1938, though it has been changed many times since then, and it exempts “executives, administrators and professionals.” There are a number of complicated eligibility rules; administrative assistants are exempt from overtime pay, for example. But for many workers, eligibility depends on how much you make: if you earn less than $455 a week ($23,660 a year) and don’t fit in one of the other exemption categories, you’re eligible for overtime.

Obama is raising that threshold to $50,400 a year. As a result, somewhere between five and 15 million additional workers will be eligible for overtime, most in retail and food service and most of them women.

In the short term, this will likely mean a pay increase for newly eligible workers, at least on an hourly basis. But research suggests that over time firms will lower salaries in order to get the same amount of work at the same price. Let’s say you make $40,000 a year and work 60 hours a week. Instead of paying you more for overtime, or paying you the same salary for just 40 hours of work, your employer could decide to pay you $23,000 as a base salary, plus time-and-a-half for your 20 hours of overtime, for an annual total of $40,000. Nothing would have changed.

Workers probably wouldn’t stand for this treatment, and for that reason it’s unlikely to happen immediately. Instead, it will kick in over time as firms hire new workers, or as they forgo raises and inflation slowly chips away at existing workers’ pay. One study estimated that this effect offsets about 80% of the additional pay workers would see if they were simply paid for overtime at their current salaries. Advocates of the reform admit as much, but point to the short-term wage increase, as well as the fact that not all of that increase gets wiped out by lower base wages, even in the long term.

What about overwork? By raising the cost of overtime for employers, would reform lead to saner work hours? Not likely, according to research. Firms’ ability to lower base pay seems to erode interest in shortening work days, too.

Management seems intent on imposing long hours on workers, regardless of overtime rules, which isn’t surprising given that managers are often working brutal hours themselves. In fact, the cult of overwork is as much cultural as economic. As a paper on overtime in Britain put it, “the overtime premium is essentially the outcome of established custom and practice,” just one more aspect of the labor market that depends, at least in part, on social norms.

Adjusting overtime rules will likely raise some workers pay, and that’s to be applauded. But it won’t do much to curb America’s reliance on long hours. That won’t improve until management starts to realize that overwork isn’t a sign of productivity or achievement, and that in fact it rarely leaves either companies or their employees better off.

Are We Evaluating U.S. Presidential Hopefuls All Wrong?

Americans are starting the turn toward a presidential election. Candidates are announcing their bids and pundits are practicing their rhetoric. But despite my faith in the electorate, I’m worried. It’s not any specific candidate or issue or political ideology that’s the source of my concern. It’s the way we value certain leadership qualities – like experience – over traits like motivation, competence, and potential when we go to the voting booth.

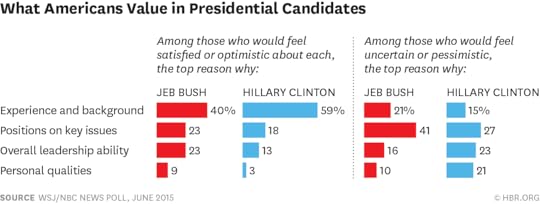

Consider the recent WSJ/NBC poll on the 2016 general election, which was conducted June 14-18. The graphic below shows, based on that same poll, the top reasons why voters would feel optimistic or pessimistic about each of the current major party frontrunners — Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush. The right part of the graphic, which shows reasons why voters might feel uncertain or pessimistic based on each candidate, reveals that voters place more importance on the leader’s position on key issues (what they say, largely conditioned by their political affiliation), followed by their leadership ability (what they do), and only in third place by their personal qualities (who they are, including their values and potential to continue growing and learning). However, this is exactly the reverse order that we should be following when predicting leadership greatness. Great leaders are truly great not because of what they say, or even what they do, but because of who they are.

The left part of the graphic, in turn, shows that voters place more importance on the leader’s experience and background, followed by their leadership ability (competence), and only in a very distant third place by their personal qualities (which include the individual’s potential to continue growing and learning.) Unfortunately, once again, the best practices for choosing great leaders should actually follow the exact reverse order: Potential trumps competence which in turn trumps experience and background.

It turns out we are poorly equipped at making political choices. Researchers at UCLA have used fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to measure people’s neural activity when they are asked to agree or disagree with political statements on hot-button issues. The images show that the most politically sophisticated individuals actually use the fewest cognitive areas to “vote,” showing the highest levels of activity in the “default state network” (specifically the precuneus and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex) of the brain, which typically dominates when we’re doing nothing, with no specific goals or tasks at hand. Dramatically, exposure to politics actually appears to make us worse at choosing our politicians.

As I argue in my June 2014 Harvard Business Review article on “21st Century Talent Spotting,” geopolitics, business, industries, and jobs are changing so rapidly that we can’t predict the competencies needed to succeed even a few years out in the corporate context. It is therefore imperative to identify those leaders with a strong ability to grow and adapt to fundamentally different and increasingly complex responsibilities.

In the context of a presidential election, we may feel more confident about a candidate’s background and experience as a predictor of success. The mistake we make, however, is valuing experience instead of competence, potential and motivation.

In order to better evaluate presidential candidates, we shouldn’t ignore factors like intelligence, experience, track record, and specific competencies, particularly the ones related to presidential leadership. But potential should be the most important factor, followed by competence, and then experience and background.

So here’s what voters should do to fight certain neural impulses, think straight, and consider the right combination of qualities in their next leader: Look for openness to change, willingness to surround themselves with the best, capacity for growth, and selfless commitment

Openness to change. Given the complexities of our political system, the volatile state of our world, and the passions that surround key issues, voters should carefully check an individual’s openness to change their views. The positions a political candidate holds on certain issues may feel of urgent relevance today. For example, we may spend a good deal of time considering someone’s definitive views on issues like healthcare, minimum wage, or foreign policy. But in fact, because the issues themselves are in a constant state of change we should also be choosing leaders based on their ability to adapt their decision-making or negotiating criteria in the face of uncertainty or unexpected events. How often do we ask ourselves how likely our candidate would be to change his or her views if necessary, challenging former positions, party loyalty, and stakeholder pressures?

Willingness to surround themselves with the best. Given the monumental job at hand, we should carefully check presidential hopefuls on their willingness to put together a smart team of advisers. This is an important attribute of some of our greatest business leaders, from Warren Buffett to Jeff Bezos, and is what the exceptional President Abraham Lincoln did while putting together his famed team of rivals. Any potential president needs to have a solid track record of “who” choices. Had they promoted stars and worked to reassign or develop underperformers? Fostered diversity and inclusion? Consistently mentored great successors throughout their career?

Capacity for growth. While no one is ever fully prepared to be a president, we should check their capacity to grow into that job by looking for four traits: curiosity, insight, engagement, and determination. Is the candidate someone who seeks new experiences, ideas, knowledge, and self-awareness, who solicits feedback and who stays open to learning and change? Someone able to gather and make sense of new information and to use his or her insights to shift legacy views and set new directions? What does their background indicate about these qualities? Is he or she a person who connects on an emotional level with others, demonstrates empathy, communicates a persuasive vision, and inspires commitment to the broader organization? Are they someone with the strength to persist in the face of difficulties and to bounce back from major set-backs or adversity?

Selfless commitment. A great leader has the right motivation. This is, of course, tricky to gauge when political ambitions and agendas are at play. But you can ask: Would your next president show the purest blend of fierce commitment together with deep personal humility? Someone genuinely devoted to making America and our world a much better place, and building lasting greatness long after he or she is gone? Someone prepared to do whatever is needed at whatever personal cost? Someone who uses the position to both attribute credit to others and hold himself accountable when things go wrong?

The qualities that make a good leader often sound simple in theory – and politics, as we all recognize, is not. There are many other factors that go into a candidate’s ascension to the highest job in the land, and modern American elections reward candidates in part based on their fund raising, their media skills, and their effectiveness at managing national campaign organizations. But away from the noise of an election cycle, voters can still consider the fundamentals that make a leader great and ask themselves if they would choose differently given different criteria.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers