Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1276

July 7, 2015

What People Analytics Can’t Capture

After I gave a talk at a global consultancy about how to better handle the strains of extensive travel and demanding clients, one of the consultants took me aside and confided that it’s not just the clients who make them crazy – her own boss was a tyrant and bully who screamed at people for the smallest lapse. He made life so miserable for his direct reports that many of the best had moved on to other companies.

That encounter came to mind as I read TIME’s recent cover story on the latest fad in human resources, using big data analytics and personality test scores to predict who is best for a given job – so-called “XQ.”

Of course many businesses are reaping rewards from big data analytics. But there are also some areas of disappointment. Experts caution that big data, like any other, is only as good as the questions being asked – and that some algorithms can make unhelpful assumptions.

There’s a saying in the sciences, “Statistics means never having to say you are certain.” In any massive data analysis, for instance, there will be random correlations that look “significant” but actually are noise, not signal.

And then there’s the question of what metrics a personality test uses to gauge “success.” Big data needs a hard outcome metric for performance, but the most readily available metrics may not actually be the most important variables in organizational flourishing.

A manager – like the demotivating petty tyrant mentioned above –can force his people to work hard to meet quarterly targets, for example, while destroying the emotional climate that sustains the life-blood of any organization. We have long known that managers who focus too much on performance at the expense of people can be ruinous to the organization over the long term. Using an outcome metric like an executive’s earnings performance, while ignoring his role as a boss and his impact on the morale, loyalty, focus, and stress levels of his direct reports, may result in a false indication of who’s really the best boss.

It’s telling that at Google, that bastion of algorithms emerging from giant data sets, engineers refused to use just such a method to decide on promotions. As Laszlo Bock, head of hiring at Google explained, the very fact the company knows so much about algorithms lets it see their limits. The assumptions built into a test can themselves be biased against certain traits and so discriminate unfairly.

But the biggest objection comes from the fact that the strongest predictor of a person’s future behavior is their past performance itself. And that performance gets evaluated best by people who know that person well.

That’s the case made, for instance, by Claudio Fernandes-Araoz in his instant classic on hiring, It’s Not the How or the What But the Who. He advises that the most trustworthy and valuable information will come from honest interviews with people who have worked in the past with a given job candidate.

Consider the power of a leader’s character – a factor that interviews, not multiple-choice tests, can assess best (after all, someone who lacks integrity is likely to lie about indicators of honesty). As Fred Kiel’s research shows, character traits like integrity and compassion are surprisingly strong drivers of business success. Those high in these qualities, Kiel found, got five times better business results than did those low in them.

In evaluating a candidate’s integrity, which would you trust: how that person answered test questions bearing on honesty, or what people who know that person have actually experienced?

So here’s what I’d recommend. Keep in mind the distinction between a threshold competence and a distinguishing one. A threshold skill means everyone must meet this criterion just to be considered for a job. At Google, the threshold includes test scores showing you are in the top 1% of IQ. For companies using the so-called XQ, big data analysis of test scores, a certain level of correlation could be taken as the threshold.

After that, though, are distinguishing competencies, the skills or abilities that you find in star performers in an organization but not in those who are mediocre – those just good enough to keep their job. It’s the distinguishing competencies you’re looking for in your due diligence with people who have worked with this person in the past.

The Right Way to Plan an Innovation Tour

Kenneth Andersson

Innovation tourism: it’s a thing. The tourists are entrepreneurs looking for the right economic microclimate to start a business; corporate scouts looking to expand their company’s reach or improve their supply chain; policy makers trying to figure out the right balance of rules and infrastructure to create a thriving economy; investors searching for the next crop of opportunities. These well-intentioned professionals travel the world in pursuit of the secret sauce of innovation. Typically, tourism involves guided tours, pitch events, conferences with lots of panels, and well-planned visits to companies, universities, and government agencies tasked with increasing entrepreneurship and innovation.

The problem is, all of these good people are often guided to see a distorted reality. Not that more formalized presentations and assessments are necessarily Potemkin villages, but they often miss what’s really going on. It’s just that these actors naturally tend toward self-promotion. (If you ask the director of a government innovation agency how influential or effective they are, what answer do you expect, other than “extremely?” Have you ever encountered a university tech transfer office director who says, “Sorry, we are a drain on the university’s cash?”)

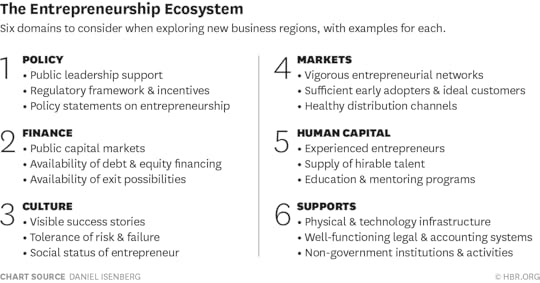

But an innovation tour can be valuable, as long as you know what to look for and think about. Entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems aren’t simple, easily graspable objects; they are a construct we use to make sense of an exceedingly complex reality. And they are indeed important to be able to see and understand. To get at their essence, you need to think and act like the anthropologist doing field research by observing, questioning, and listening to many different parts of the land you are visiting. Here are some tips for a useful innovation tour:

Tip 1: Look for the “software,” not the “hardware.” Many people, including business experts, misconceive entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems as consisting of the activities and structures which are easily visible – what I call the entrepreneurship ecosystem “hardware”: startup incubators, angel investor meetings, tech transfer offices, innovation centers, entrepreneurship courses, business plan competitions. Yet the most important drivers of entrepreneurship are often the more subtle “software”: the networks of trust going back to high school or military service, the belief systems or values at the root of people’s resilience in the face of setbacks, or the social norms which encourage thinking out of the box.

So try to find networking events, engage in conversations, or participate in the programs that shape that software. In 2009, I took 42 Harvard Business School students to Israel for a week of entrepreneurship exploration. I first had them meet with an Israeli army signal corps general (who was in the midst of overseeing a military operation); then we headed to a beach to engage in team building and camouflage exercises with young Israelis preparing for elite military combat units. Since military service is mandatory in Israel, this provided useful insights into the culture and mindsets of Israelis.

In addition, we also went to the discos to experience the culture’s youthful exuberance. And we spent time at Kibbutz Ein Shemer’s field house for ecological initiatives and experimentation. This helped underline the idea that cultural and social “software” is every bit as important as business and economic “hardware” in assessing a region’s business ecosystem.

Tip 2: Talk to all the actors, not just entrepreneurs. Don’t ignore the bankers, business families, corporate executives, private equity investors, researchers, service professionals, and educators. My ecosystem map is a good way to make sure you are touching all the bases.

I took an HBS student group to India in 2008 and met with CEOs of public companies, heads of family business groups, and visited Keggfarms, an innovative chicken breeder trying to make a dent in poverty. Thinking that entrepreneurs alone reflect the entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem is a common mistake by even esteemed experts. It’s a bit like saying that a baseball game is exclusively about the pitcher. Without the lonely right fielder, baseball wouldn’t work either. Don’t just make a beeline to the entrepreneurs and venture capitalists; get a broad multi-disciplinary cross section.

Tip 3: Talk to people in mixed groups rather than in isolation. In over a dozen locations, including Istanbul, Edmonton, Copenhagen, and Puerto Rico, I have facilitated roundtable group conversations among researchers, investors, government officials, entrepreneurs, and non-profits. Not only does it become clear that they can have radically different views, but these group conversations will teach you important lessons about people’s naturally heterogeneous motivations for wanting more entrepreneurship. The university administrators want to attract students and donors with entrepreneurship activities. City officials want to create jobs. Non-profits want to accomplish a social mission while being self-sustaining financially. Entrepreneurs want to grow their ventures for wealth, challenge, and impact. These different objectives are natural and need to be understood in order to understand the entire ecosystem.

By listening to and observing these actors in groups, you can usually see if the different domains of the ecosystem are disconnected or aligned, polite or candid, collaborative or conflicting. Further, you can see parts of the entrepreneurship culture enacted in front of your eyes: Are people independent thinkers? Do they encourage different viewpoints, experimentation, and risk-taking? Have they even met before?

Tip 4: Pay more attention to scale-up and growth, than to startup. Seek out entrepreneurs who are trying to grow their companies from $1-$10 million rather than startup entrepreneurs (who are often first-timers) pitching ideas that aren’t yet on the market. This is harder than it seems: Around the city of Milwaukee there are 14,000 companies in this size range. In fact, Wisconsin is number two in the U.S. in the proportional size of its mid-market business sector. But most of them are hunkered down running their businesses and talking to customers, rather than going to hyped-up pitch fests or taking part in accelerators or conferences. It is surprisingly rare for entrepreneurship observers to put growth at the center of the dialogue. But you get a very different view of the ecosystem by looking at growth.

At Colombia’s Manizales Más, we conducted a study with the Chamber of Commerce of the local factors inhibiting or facilitating the growth of 100 companies. The responses put an emphasis on the challenge of attracting and retaining talent rather than on raising risk-capital. Again, the focus lands on scaling up and growing your business, not just getting it off the ground.

Focusing on scale-ups also matters when you talk to bankers. You will lose the bankers if your guidepoint is startups rather than growth; it is not banks’ business to invest in startups with few assets to secure as guarantees. But bankers are paying keen attention to those ventures who break away into rapid growth.

Tip 5: Study the financing food chain starting from the end, not the beginning. It goes without saying that finance is an essential element in entrepreneurial innovation, but don’t start with the angel investors or VCs. Start with the investment bankers whose livelihood it is to advise on acquisitions, talk to stock exchange officials, and meet with the late stage PE fund managers. Don’t ignore the companies who are leasing equipment to growth firms. In Colombia, as part of Manizales Más, we are developing financial instruments for rapidly growing businesses. By starting at the end of the financing food chain, it became clear that the exit possibilities in Colombia are so limited that VCs and angel investors will have great difficulty seeing a return for decades to come. As a result, we are developing hybrid financial instruments to give investors faster (if smaller) and more secure returns.

Tip 6. Look beyond what people tell you. When you talk to entrepreneurs (or any other actors for that matter) take what they say with a big grain of salt. Most people are not trained at observing or explaining their own behavior, let alone that of others, and entrepreneurs are no exception. I have talked to entrepreneurs in over 40 countries, and the story is always the same: “It is difficult to get access to early stage capital, hard to find talent, aggravating to fight with regulation and bureaucracy.” Sound familiar? Furthermore, innovation agency officials, or the national SBA, will gladly talk about how influential they are in all the successes. Talk to venture capitalists and they, too, will tell you how essential they are in leading the charge. Leaders of startup communities will passionately explain how startups are so important.

So you need to dig beneath the surface of what you hear. For example, one senior government official I know visited Israel and learned about Yozma, the gold standard of government efforts to stimulate venture capital, which was a $100 million fund of funds in the 1990s. Hearing about the positive impact of Yozma (a view more widely held by government officials than by Israel’s first generation of investors), his takeaway was to promote a similar VC fund in his country. Yet when I debriefed him, no one had told him that perhaps the critical element in Yozma’s success was the option the investors in each fund had to buy out the government’s interest at a pre-defined price. It’s essential to ask good questions and avoid taking success stories at face value.

Tip 7: Beware of macro-economic statistics applied to specific regions. Since innovative entrepreneurship is by definition rare and entrepreneurship ecosystems are by definition hyper-local, even metro area statistics often mask the realities of entrepreneurship in a region. Recently Scale Up Milwaukee hosted a visitor from a prominent entrepreneurship institute who came with well-prepared data showing Milwaukee’s population was in decline, researchers per capita were low, and the startup rate was abysmal. But after three days of seeing pockets of vibrant growth, the community engagement of the many large local corporations, and talking with investors who are actually investing, he changed his view of Milwaukee as a “challenged city” on par with Detroit (and Detroit may be rapidly changing as well) to one of strong potential.

Tip 8: Try to identify and meet the hidden heroes. Two years ago I had lunch with MIT entrepreneurship Professor Ed Roberts who had been one of my early entrepreneurship mentors in the 1980s. Since the 1960s, Roberts has been at the nexus of the Boston entrepreneurship ecosystem. Decades before the Cambridge Innovation Center was established, Roberts had researched Boston entrepreneurs, created the first seed capital fund (Zero Stage Capital), co-founded Meditech, and sat on boards of many technology companies. We were interrupted five times by entrepreneurs stopping in the MIT Sloan School cafeteria to thank Ed for investing, or for making a key introduction, or for giving good advice. Clearly Roberts was a key feature of the ecosystem of entrepreneurship in Cambridge. Finding these hidden heroes should be part of your research gathering.

In sum, innovation tourism is not really tourism. At root, it’s an important endeavor in attempting to understand how a complex economic and cultural reality actually works. To do this successfully, you need to become an anthropological investigator, ask tough questions, and get beyond appearances.

What Every Manager Should Know About Machine Learning

Perhaps you heard recently about a new algorithm that can drive a car? Or invent a recipe? Or scan a picture and find your face in a crowd? It seems as though every week companies are finding new uses for algorithms that adapt as they encounter new data. Last year Wired quoted an ex-Google employee as saying that “Everything in the company is really driven by machine learning.”

Machine learning has tremendous potential to transform companies, but in practice it’s mostly far more mundane than robot drivers and chefs. Think of it simply as a branch of statistics, designed for a world of big data. Executives who want to get the most out of their companies’ data should understand what it is, what it can do, and what to watch out for when using it.

Not just big data, but wide data

The enormous scale of data available to firms can pose several challenges. Of course, big data may require advanced software and hardware to handle and store it. But machine learning is about how the analysis of the data also has to adapt to the size of the dataset. This is because big data is not just long, but wide as well. For example, consider an online retailer’s database of customers in a spreadsheet. Each customer gets a row, and if there are lots of customers then the dataset will be long. However, every variable in the data gets its own column, too, and we can now collect so much data on every customer – purchase history, browser history, mouseclicks, text from reviews – that the data are usually wide as well, to the point where there are even more columns than rows. Most of the tools in machine learning are designed to make better use of wide data.

Predictions, not causality

The most common application of machine learning tools is to make predictions. Here are a few examples of prediction problems in a business:

Making personalized recommendations for customers

Forecasting long-term customer loyalty

Anticipating the future performance of employees

Rating the credit risk of loan applicants

These settings share some common features. For one, they are all complex environments, where the right decision might depend on a lot of variables (which means they require “wide” data). They also have some outcome to validate the results of a prediction – like whether someone clicks on a recommended item, or whether a customer buys again. Finally, there is an important business decision to be made that requires an accurate prediction.

One important difference from traditional statistics is that you’re not focused on causality in machine learning. That is, you might not need to know what happens when you change the environment. Instead you are focusing on prediction, which means you might only need a model of the environment to make the right decision. This is just like deciding whether to leave the house with an umbrella: we have to predict the weather before we decide whether to bring one. The weather forecast is very helpful but it is limited; the forecast might not tell you how clouds work, or how the umbrella works, and it won’t tell you how to change the weather. The same goes for machine learning: personalized recommendations are forecasts of people’s preferences, and they are helpful, even if they won’t tell you why people like the things they do, or how to change what they like. If you keep these limitations in mind, the value of machine learning will be a lot more obvious.

Separating the signal from the noise

So far we’ve talked about when machine learning can be useful. But how is it used, in practice? It would be impossible to cover it all in one article, but roughly speaking there are three broad concepts that capture most of what goes on under the hood of a machine learning algorithm: feature extraction, which determines what data to use in the model; regularization, which determines how the data are weighted within the model; and cross-validation, which tests the accuracy of the model. Each of these factors helps us identify and separate “signal” (valuable, consistent relationships that we want to learn) from “noise” (random correlations that won’t occur again in the future, that we want to avoid). Every dataset has a mix of signal and noise, and these concepts will help you sort through that mix to make better predictions.

Feature extraction

Think of “feature extraction” as the process of figuring out what variables the model will use. Sometimes this can simply mean dumping all the raw data straight in, but many machine learning techniques can build new variables — called “features” — which can aggregate important signals that are spread out over many variables in the raw data. In this case the signal would be too diluted to have an effect without feature extraction. One example of feature extraction is in face recognition, where the “features” are actual facial features — nose length, eye color, skin tone, etc. — that are calculated with information from many different pixels in an image. In a music store, you could have features for different genres. For instance, you could combine all the rock sales into a single feature, all the classical sales into another feature, and so on.

There are many different ways to extract features, and the most useful ones are often automated. That means that rather than hand-picking the genre for each album, you can find “clusters” of albums that tend to be bought by all the same people, and learn the “genres” from the data (and you might even discover new genres you didn’t know existed). This is also very common with text data, where you can extract underlying “topics” of discussion based on which words and phrases tend to appear together in the same documents. However, domain experts can still be helpful in suggesting features, and in making sense of the clusters that the machine finds.

(Clustering is a complex problem, and sometimes these tools are used just to organize data, rather than make a prediction. This type of machine learning is called “unsupervised learning”, because there is no measured outcome that is being used as a target for prediction.)

Regularization

How do you know if the features you’ve extracted actually reflect signal rather than noise? Intuitively, you want to tell your model to play it safe, not to jump to any conclusions. This idea is called “regularization.” (The same idea is reflected in terms like “pruning”, or “shrinkage”, or “variable selection.”) To illustrate, imagine the most conservative model possible: it would make the same prediction for everyone. In a music store, for example, this means recommending the most popular album to every person, no matter what else they liked. This approach deliberately ignores both signal and noise. At the other end of the spectrum, we could build a complex, flexible model that tries to accommodate every little quirk in a customer’s data. This model would learn from both signal and noise. The problem is, if there’s too much noise in your data, the flexible model could be even worse than the conservative baseline. This is called “over-fitting”: the model is learning patterns that won’t hold up in future cases.

Regularization is a way to split the difference between a flexible model and a conservative model, and this is usually calculated by adding a “penalty for complexity” which forces the model to stay simple. There are two kinds of effects that this penalty can have on a model. One effect, “selection”, is when the algorithm focuses on only a few features that contain the best signal, and discards the others. Another effect, “shrinkage”, is when the algorithm reduces each feature’s influence, so that the predictions aren’t overly reliant on any one feature in case it turns out to be noisy. There are many flavors of regularization, but the most popular one, called “LASSO”, is a simple way to combine both selection and shrinkage, and it’s probably a good default for most applications.

Cross-validation

Once you have built a model, how can you be sure it is making good predictions? The most important test is whether the model is accurate “out of sample”, which is when the model is making predictions for data it has never seen before. This is important because eventually you will want to use the model to make new decisions, and you need to know it can do that reliably. However, it can be costly to run tests in the field, and you can be a lot more efficient by using the data you already have to simulate an “out of sample” test of prediction accuracy. This is most commonly done in machine learning with a process called “cross-validation”.

Imagine we are building a prediction model using data on 10,000 past customers and we want to know how accurate the predictions will be for future customers. A simple way to estimate that accuracy is to randomly split the sample into two parts: a “training set” of 9,000 to build the model and a “test set” of 1,000, that is initially put aside. Once we’ve finished building a model with the training set, we can see how well the model predicts the outcomes in the test set, as a dry run. The most important thing is that model never sees the test set outcomes until after the model is built. This ensures that the test set is truly “held-out” data. If you don’t keep a clear partition between these two, you will overestimate how good your model actually is, and this can be a very costly mistake to make.

Mistakes to avoid when using machine learning

One of the easiest traps in machine learning is to confuse a prediction model with a causal model. Humans are hard-wired to think about how to change the environment to cause an effect. In prediction problems, however, causality isn’t a priority: instead we’re trying to optimize a decision that depends on a stable environment. In fact, the more stable an environment, the more useful a prediction model will be.

It’s important to draw a distinction between “out-of-sample” and “out-of-context”. Measuring out-of-sample accuracy means that if we collect new data from the exact same environment, the model will be able to predict the outcomes well. However, there is no guarantee the model will be as useful if we move to a new environment. For example, an online store might use a database of online purchases to build a helpful model for new customers. But the exact same model may not be helpful for customers in a brick-and-mortar store – even if the product line is identical.

It’s tempting to think that the sheer size of data available can get around the issue. That’s not the case. Remember, these algorithms draw their power from being able to compare new cases to a large database of similar cases from the past. When you try to apply a model in a different context, the cases in the database may not be so similar any more, and what was a strength in the original context is now a liability. There’s no easy answer to this problem. An out-of-context model can still be an improvement over no model at all, as long as its limitations are taken into consideration.

Even though some parts of model-building can seem automatic, it still takes a healthy dose of human judgment to figure out where a model will be useful. Furthermore, there’s a lot of critical thinking that goes into making sure the built-in safeguards of regularization and cross-validation are being used the right way.

But it’s also good to keep in mind that the alternative — purely human judgment — comes with its own set of biases and errors. With the right mix of technical skill and human judgment, machine learning can be a useful new tool for decision-makers trying to make sense of the inherent problems of wide data. Hopefully without creating new problems along the way.

July 6, 2015

Comparing the ROI of Content Marketing and Native Advertising

Many companies today rely on content marketing and native advertising to gain visibility for their brand — after all, 70% of people say they’d rather learn about products through content rather than through traditional advertising. But is either content marketing or native advertising a surefire way to boost brand awareness? And which one offers more bang for the buck?

To answer this question, we at Fractl, a content marketing firm, collaborated with Moz to survey over 30 agencies specializing in content marketing about content formats and the metrics they use to track ROI. And I’ll get to what we found, below. But first, let’s remind ourselves how each approach is different, and what each approach aims to do.

Content marketing agencies produce campaigns for brands (this is an example) and then pitch these to multiple top-tier publishers for coverage. Each time a publisher writes about a campaign, it will usually link back to the company as the source. These links increase a company’s organic search rankings, direct traffic to the company’s website, and drive user engagement for the brand via social media.

Whereas content marketing usually tries to secure dozens of media pickups, native advertising promotes content by paying to partner with a single publisher. (This is an example of a native advertising partnership between BuzzFeed and all Laundry Detergent.) Native advertising (also known as sponsored content) offers a guaranteed placement with a top-tier publisher that might have monthly unique visitors in the multi-millions.

We took a data-driven approach to compare the efficacy of native advertising versus content marketing. Here’s what we learned about how the two strategies stack up.

First, we looked at content marketing services. On average, 65% of agencies produce between one and 10 campaigns per month for each of their clients. The process for a single campaign includes idea generation, concept research, asset design, and – the final step – promotion. Once a team has completed production, they pass the campaign to a media relations associate who secures press coverage for the campaign. The goal: getting staff writers at a high-authority websites to produce a story about the campaign for their publishers.

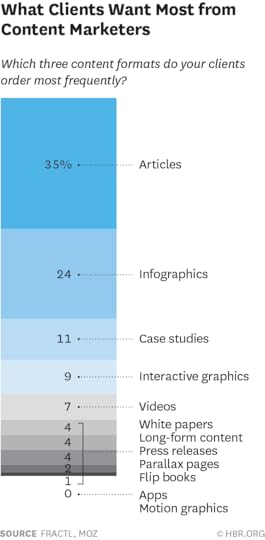

In the early days of content marketing, widgets, and “listicles” dominated the landscape. As Google began penalizing brands for thin content pages and low-value link schemes, the industry scrambled to produce higher-quality content. Thus, like some publishers, content marketing agencies started to produce more articles and infographics than other content formats.

Almost half of clients measure content marketing success by the number of leads (i.e., customer conversions based on campaigns), high-quality links (i.e., links from high-authority publishers), and total social media shares generated by each campaign. Excluding outliers, the average content marketing campaign earns 27 links from publisher stories (media pickups), whereas the average for each agency’s “most successful campaign” is 422 links and the median is 150 links.

How much does this cost? We found that 70% of content marketing agencies offer monthly retainers, and these fall into five buckets: Less than $1,000, $1,000–$5,000, $5,000–$10,000, $10,000–$50,000, and $50,000–$100,000. Content marketing costs largely relate to the scope of the projects being produced (e.g., press releases versus interactive graphics) and their reach (e.g., influencer marketing versus no outreach). We found that a price tag of between $5,000-$50,000 correlated with campaigns that generated the most links, which suggests that agencies were able to produce innovative, larger-scope campaigns, influencer marketing, and content amplification, rather than just issuing press releases. At the lower end, we did not see as much activity, and we speculate that those firms did not have the resources to generate compelling campaigns. But interestingly, at the higher end, we did not see considerably more value being created once companies went over $50,000.

Next, we wanted to see how native advertising compares. We gathered native advertising cost data from a report by Relevance, another content marketing agency, to which we added 100 additional data points to see what nearly 600 publishers charge for native advertising. We included general news publishers that tend to dominate search engine results and have a collective social following of more than 100,000 people.

At first glance, we saw that the minimum investment to partner on a native advertising is exorbitant for most brands. For example, to team up with TIME on a native advertising campaign, a client can pay up to $200,000. On average, the cost of a native advertising campaign for top-tier news publishers was $54,014.29. (For lower-tier publishers, which we categorized as having a domain authority of less than 80, the cost drops to an average between $70 and $8,000.)

Clearly, native advertising is expensive. But what’s the return? We reviewed 38 native advertising campaigns published on BuzzFeed, a leader for sponsored content, alongside 58 Fractl content marketing campaigns, to evaluate the reach (in terms of links) and engagement (social shares) of each. (Full disclosure again that my company Fractal is a content marketing agency.) Overall, Fractl’s content marketing campaigns were republished and shared more than BuzzFeed’s native advertising. For example, just comparing the top performing campaigns for each, we found that Fractl’s 11 campaigns for client Movoto resulted in, on average, 146 pickups and 17,934 social shares. BuzzFeed’s 13 campaigns for Intel resulted in one pickup on average and 12,481 social shares.

And in line with these findings, a report by eMarketer found that the most common issue cited by executives who use native advertising was of scale. Of course, you’re paying to publish content solely on the site you’re partnering with, which limits potential reach. One additional stumbling block: Google considers native advertising to be paid links, which prevents campaigns from improving the company’s search engine rankings.

With its smaller reach, is native advertising ever worth the cost? For some firms with large budgets, the expense is worth it if it means aligning their brand with a high-authority publisher and the right niche audience. Ultimately, native advertising has been proven effective in drawing higher click rates than traditional banner ads and other outbound marketing methods, so as a replacement for those, it could make sense.

While I may be biased, these data-driven findings suggest how companies might get a better bang for their buck with content marketing — especially if they’re looking for a wide reach with different publishers and audiences. However, for those mainly interested in guaranteed placement with a big-name publisher, native advertising might be the way to go.

How the Digital Wind Farm Will Make Wind Power 20% More Efficient

Sponsor Content Insight from GE.

Few people embody the backyard inventor better than Charles Brush. In 1887, he built behind his mansion in Cleveland, Ohio, a 4-ton wind generator with 144 blades and a comet-like tail, and used it to power a set of batteries in his basement. Although by today’s standards the huge, 60-foot machine was massively inefficient, it started a new industry that pushed generations of engineers to make it better. Now GE has decided to go further and improve on the entire wind farm in one fell swoop.

“Every wind farm has a unique profile, like DNA or a fingerprint,” says Keith Longtin, general manager for wind products at GE Renewable Energy. “We thought if we could capture data from the machines about how they interact with the landscape and the wind, we could build a digital twin for each wind farm inside a computer, use it to design the most efficient turbine for each pad on the farm, and then keep optimizing the whole thing.”

GE calls the concept the “digital wind farm” and the company has just offered the first glimpse at what it’s going to look like.

The concept has two key parts: a modular, 2-megawatt wind turbine that can be easily customized for specific locations, and software that can monitor and optimize the wind farm as it generates electricity.

GE says that the technology could boost a wind farm’s energy production by as much as 20% and create $100 million in extra value over the lifetime of a 100-megawatt farm. That value will come from building the right farm at the right place and then using data to produce predictable power and further optimize the farm’s performance.

“The world’s electricity demand will grow by 50% over the next 20 years, and people want to get there by using reliable, affordable, and sustainable power,” says Steve Bolze, president and CEO of GE Power & Water. “This is the perfect example of using big data, software and the Industrial Internet to drive down the cost of renewable electricity.”

The Industrial Internet is a digital network connecting, collecting and analyzing machine data. GE believes that the Industrial Internet could add $10 to $15 trillion to global GDP in efficiency gains over the next two decades.

Each digital wind farm begins life as a digital twin, a cloud-based computer model of a wind farm at a specific location. The model allows engineers to pick from as many as 20 different turbine configurations – from pole height, to rotor diameter, to turbine output – for each pad at the wind farm and design its most efficient real-world doppelganger. “Right now, wind turbines come in given sizes, like T-shirts,” says Ganesh Bell, chief digital officer at GE Power & Water. “But the new modular designs allow us to build turbines that are tailor-made for each pad.”

But that’s only half of the story. Just like Apple’s Siri and other machine learning technologies, the digital twin will keep crunching data coming from the wind farm and providing suggestions for making operations even more efficient, based on the software’s insights. Longtin says that operators will be even able to use data to control noise. “If there is a house near the wind farm, we will be able to change the rotor speed depending on the wind direction to stay below the noise threshold,” he says.

The data comes from dozens of sensors inside each turbine monitoring everything from the yaw of the nacelle, to the torque of the generator, to the speed of the blade tips. The digital twin, which can optimize wind equipment of any make, not just GE’s, gobbles it up and sends back tips for improving performance. “This is a real-time analytical engine using deep data science and machine learning,” Bell says. “There is a lot of physics built into it. We get a picture that feels real, just like driving a car in a new video game. We can do things because we understand the physics – we build turbines – but also because we write software.”

The digital wind farm is built on Predix, a software platform that GE developed specifically for the Industrial Internet. Predix can accommodate any number of apps designed for specific wind farm tasks – from responding to grid demand to maximizing and predicting power output. Says Bell: “This is the start of a big journey for the wind industry.”

See how GE can give you the edge: gesoftware.com

The Risks of Changing Your Prices Too Often

Today’s technologies allow digital businesses (as well as a growing roster of traditional companies) to change prices frequently, even minute-by-minute in real time if they want to. It is not unusual for prices to change on sites like Amazon, Expedia, and Priceline several times a day. But managers are struggling to understand these tactics. How often should companies really change their prices?

For any enterprise, the biggest constraint in changing prices is the “menu cost.” Historically, price changes were expensive and time-consuming. Price lists had to be recalculated, typed up, and mailed to distributors and customers; new catalogs, labels, and signs had to be printed and press releases drafted. This forced companies to maintain prices. Throughout the 2000s, even as the internet continued to grow, prices remained the same for months at a time.

Over the past few years, however, technology has drastically shifted the economics of price changes. Pricing optimization software helps companies link cost, customer, and sales-performance data and dynamic pricing methods allow firms to take account of market factors, competitor actions, and customer responses.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

Menu costs have fallen dramatically. In industry after industry, this puts pressure on managers to change prices frequently. The popularity of short-lived price promotions, flash sales, and daily deals has further destabilized prices. But the trend is most pronounced among digital businesses, where price-change costs are virtually zero.

Many marketers see frequent price changes as a way of keeping customers on the hook and luring them back to their store or sites. Constant price shifts seem to be a good way to offer discounts selectively and protect margins.

But for a lot of consumers, fluctuating prices are merely confusing, frustrating, and annoying. Changes stop customers in their tracks.

Price changes often make the buying decision infinitely more complex. Customers no longer have clear reference prices, so they don’t know when to pull the trigger. Research shows that when decisions become complex, many people delay making decisions or back out of them altogether. For example, when a price moves around on an hourly basis, the best option for many consumers is to simply tune out and postpone the purchase.

Another insidious consequence is that constant price changes shift the customer’s attention away from the product’s features to its price. Humans are hardwired to pay attention to stimuli that change and ignore those that remain stable. So when prices fluctuate constantly (and other features don’t), customers naturally turn their attention away from hedonic and experiential aspects of the product — the very factors that make a strong brand and allow the company to enjoy a price premium — and focus on price. Even products that used to be differentiated are seen as commodities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more evident than in furniture, where incessant sales have commoditized an entire category.

Frequent price changes are also perhaps the single biggest instigator of price wars. Most price changes, especially those that are publicized by companies, tend to be decreases. And when competitors see that a price is cut, they feel compelled to respond. Many airlines and supermarkets have fallen into this trap, ending up in bruising price wars as they match each others’ cuts and get caught in fast-moving downward price spirals.

There are legitimate reasons to change prices, of course. A company may want to get rid of its remaining inventory and introduce new versions of its products. Companies like Apple, Sony, Dell, and LG have to do this. And in nondigital businesses, many products are seasonal: It makes sense to mark down sweaters in April and linen suits in October, for example. Other valid reasons for changing prices include rising raw material or labor costs, encouraging customers to try something new, and rewarding loyal customers.

But customer reactions to cavalier pricing actions may make quick fluctuations unproductive at best, and inflict lasting damage to a company’s bottom-line at worst. Prices should be changed only as often as the enterprise’s tactical objectives and overarching goals dictate.

Pitfalls to Avoid When You Inherit a Team

Taking over as the leader of an existing team can be daunting. The team’s response to your new processes or style can make you feel a little like the evil stepmother who’s stepped into their formerly happy lives. Your team was once someone else’s team. They’ve developed habits in response to the preferences of the previous leader. Adjusting those habits is going to be challenging, but there are things you can do to make the transition easier on all of you.

In spite of (or perhaps because of) your efforts to get off to a good start, you risk making a few common mistakes. Here are three that I see frequently:

Trying to be a friend rather than a leader. While I urge you to be aware of and empathetic to the whiplash your team might be experiencing in going from one leader to another, it’s a mistake to allow that empathy to translate into weak leadership. Investing too much energy in befriending the team confuses the power relationships and ultimately increases the likelihood of a backlash when you begin to exert your control. Most teams are looking for clear, confident leadership. Be friendly and understanding but don’t wait too long to share your vision and to set your standards.

Expressing frustration with the quality of team. The team you inherit is the product of its previous leader: what team members pay attention to and what they’re good at is a reflection of what that leader expected of them. If your expectations are different, you need to help your team make that shift. Getting angry or frustrated, or being condescending will only create resistance and reduce their motivation to change. And if you introduce your own hires to the team and make the mistake of favoring them while treating long-standing team members as damaged goods, that demotivation will just turn to despair.

Attempting to force trust and candor too quickly. Many new team leaders want to create a frank and transparent culture from the start. While that’s a noble objective, exposing contentious issues too soon can be destabilizing. Until team members have had time to build their confidence and see how you handle uncomfortable topics, too much candor will do more harm than good. That’s because you are naively and inadvertently exposing people along with issues. Some of those people will lash out in self-defense and others will take their grievances underground. To avoid that bad behavior, let trust build by discussing increasingly sensitive topics and showing that you’ll address them calmly and constructively.

These are only three of the common mistakes I see new team leaders make. But they give you the idea that in the tricky business of taking over an existing team, balance, empathy, and patience go a long way.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

While you’re being patient, there are a few things you can do to create a strong connection and get your team off to a good start. I recommend using three 2-hour meetings to address the following topics:

Share your story and your owner’s manual. One of the things I always do when I start to work with a new team member is to share what I call my “owner’s manual.” Just as your dishwasher has a manual to tell you where to place the bowls so the insides get clean, there are ways of working that allow team members to get the best of you, and other ways that will cause a major malfunction. For example, do you want informal daily check-ins on the progress of a project or would you prefer a scheduled weekly update? Do you want your team to come to you at the first sign of a problem or would you prefer that they do the investigation and come with a proposed solution? Team members will appreciate you sharing your backstory and helping them understand the evolution of your preferences and idiosyncrasies. It’s also a nice way of creating a personal connection. Once you’ve shared your story, ask team members to share theirs. If you have the luxury, this is a great exercise to do over dinner.

Define the purpose of the team. Although it sounds obvious, being explicit about what you all need to accomplish together is one of the most effective things you can do with a new team. Start by discussing the external environment and the trends that are affecting your organization. Boil them down to the biggest opportunities and threats and then identify the unique value of your team in that context. From that starting point, define the parts of that mandate that you can only accomplish together — they should form the core of your time together. Then, set your meetings to accommodate the different aspects of your mandate. Use quick weekly or daily huddles for the tactical or urgent issues so they don’t bog down your other meetings. Use bi-weekly or monthly two-hour meetings to have the whole team weigh in on important operational items. Reserve longer meetings each quarter to anticipate and address strategic issues. That way, your meeting structure will keep you focused on the value your organization needs you to add.

Articulate the tensions that should exist and how to manage them. Once you’ve created a connection among the people on the team and rallied them together with a clear purpose and mandate, the last step in getting your new team off on the right foot is to create the ground rules for how you will operate. Of all the topics for ground rules, the most critical is that you understand the tensions that will exist on the team and set the standards for how you will deal with them. To do this, refer back to your mandate and ask people to encapsulate their role in achieving the mandate. Highlight where these roles will be in tension with one another (e.g., the operations leader will be pushing for stability and consistency while the product leader will be looking for novel solutions to take to the market). This will give the team a language to describe the conflicts that will emerge. Then come up with your rules for how you’ll handle these moments to ensure the conflict is constructive.

It’s a delicate business taking over a team with existing relationships and established processes. Tread carefully and make sure you’re balancing your empathy for team members with your drive to increase effectiveness. Don’t rush. Instead, use a series of extended conversations about the individual members, the mandate of the team, and the rules of the road to start to build and bolster trust. And when you make a mistake, own up to it — it’s the best way to become a leader the team can rally behind.

The Condensed Guide to Running Meetings

We love to hate meetings. And with good reason — they clog up our days, making it hard to get work done in the gaps, and so many feel like a waste of time. There’s plenty of advice out there on how to stop spending so much time in meetings or make better use of the time, but does it hold up in reality? Can you really make meetings more effective and regain control of your calendar?

Paul Axtell, who has worked for 35 years as a personal effectiveness consultant and wrote Meetings Matter: 8 Powerful Strategies for Remarkable Conversations, says that this is a major pain point for almost every manager he works with. “People are absolutely resigned. They have given up on the hope that it could be different. People are looking for tactics, tips, and gimmicky ideas and they don’t always work,” he says. I asked Axtell and Francesca Gino, a professor at Harvard Business School and the author of Sidetracked: Why Our Decisions Get Derailed, and How We Can Stick to the Plan whether much of the conventional wisdom holds true.

1. “Keep the meeting as small as possible. No more than seven people.”

Of course, there is no magic number. Though research does not point to a precise number, “there is evidence to suggest that keeping the meeting small is beneficial,” says Gino. For one, you’re better able to pick up on body language. “In a group of 20 or more, you can’t keep track of the subtle cues you need to pick up,” says Axtell. And if you want people to have the opportunity to contribute, you need to limit attendance. Axtell says that in his experience limiting it to four or five people is the only way to make sure everyone has the chance to talk in a 60-minute meeting.

The challenge with large meetings isn’t just that everyone won’t have a chance to talk, but many of them won’t feel the need to. “When many hands are available, people work less hard than they ought to,” explains Gino. “Social psychology research has shown that when people perform group tasks (such as brainstorming or discussing information in a meeting), they show a sizable decrease in individual effort than when they perform alone.” This is known as “social loafing” and tends to get worse as the size of the group increases.

This isn’t to say that your 20-person meeting is doomed for failure. You just need to plan much more carefully. “The degree of facilitation has to go up,” says Axtell. You have to be more thoughtful about getting input from the group and reading people in the room. “You need someone who is masterful at managing the conversation.”

2. “Ban devices.”

Both experts agree this is a good idea, for two reasons. First, devices distract us. Gino points out that many people think they can multitask—finish an email or read through your Twitter feed while listening to someone in a meeting. But research shows we really can’t. “Recent neuroscience research makes the point quite clear on this issue. Multitasking is simply a mythical activity. We can do simple tasks like walking and talking at the same time, but the brain can’t handle multitasking,” says Gino. “In fact, studies show that a person who is attempting to multitask takes 50% longer to accomplish a task and he or she makes up to 50% more mistakes.”

And to make matters worse, those who pick up their devices during meetings may well be the worst multitaskers. “The research finds that the more time people spend using multiple forms of media simultaneously, the least likely they are to perform well on a standardized test of multitasking abilities,” explains Gino.

The second reason to ban devices is that they distract others. Gino recently conducted a simple survey that assessed whether people thought reaching for a phone, posting a status on Facebook, or writing a tweet during a meeting was distracting or socially inappropriate. The subjects “found the same action to be much more problematic if their friend or colleague engaged in it, but did not find it to be very problematic when they were the ones who were (arguably) being rude,” she says. These results suggest that we feel annoyed when others are on their devices during a meeting. “Yet we fail to realize that our actions will have the same effect on others when we are the ones engaging in them,” she says. This is what Axtell sees in practice—that people feel hurt or insulted when someone reaches for their phone, especially if that person is a senior leader. “If you’re presenting or talking about an idea and you see a senior manager on their phone, it hurts,” he says.

Still, there are some good reasons to use technology in a meeting, says Axtell. You may want to take notes, or retrieve reference material. “Perhaps they need to be available because something important is going on in their lives,” he says. But if you’re not doing any of those these things, turn your phone or tablet off and pay attention.

3. “Keep it as short as possible — no longer than an hour.”

Research shows that there are advantages to keeping it shorter. For one, people stay more focused. “Classic studies have found that groups adjust both their rate of work and their style of interaction in response to deadlines and time constraints,” says Gino. For example, one study showed that “groups solving problems communicated at a faster rate and used more autocratic decision-making processes under high time pressure than they did when time pressure was low.”

“Once people realize you’re tight on time, they stop asking questions or talking and focus on getting the work done,” says Axtell.

This doesn’t mean you should try to cram every meeting into 30 minutes. Axtell warns that there are conversations that necessitate more time and you shouldn’t rush over topics. “If the purpose of your meeting is to talk through something, you need to give people enough time to voice their opinions, build on one another’s ideas, and reach a conclusion,” he says. Time pressure will make this more efficient, but you don’t want to make the time so short that you truncate important conversations.

4. “Stand-up meetings are more productive.”

While some might feel this is a gimmick, Gino points out that there is empirical data that proves stand-up meetings work. In this study (which was done in 1999 before stand-up meetings were a staple in most offices), Allen Bluedorn from the University of Missouri and his colleagues concluded that they were about 34% shorter than sit-down meetings, yet produced the same solutions.

Axtell finds these types of solutions encouraging. “I like that people are trying to do something bold to change up meetings — going for a walk, standing up,” he says. But, he warns, don’t let the format distract you from doing what really matters — running an effective meeting. “I’d prefer people have the guts to say, ‘I’m going to run this meeting well.’ Plan ahead, ban distractions, etc.”

5. “Make sure everyone participates and cold-call those who don’t.”

Some people may want to speak up but don’t feel like they can unless they’re asked, says Axtell. This may be due to “cultural reasons, or language barriers, or general disposition.” The people who hold back often have the best perspective on the conversation and definitely need to be drawn out.

Having everyone contribute isn’t just good for the end result of your meeting but for the participants themselves as well. People like to know that their opinions are being heard and considered, says Gino. And, “just by asking people in the meeting for their opinion, you’re going to raise their commitment to the issues being discussed.”

For people who feel too put on the spot, you can talk to them ahead of time and tell them that you’re hoping they’ll contribute. That way, they’ll have time to plan what they’ll say. Then in the meeting, you may still need to ask for their perspective but they’ll be primed to do so.

6. “Never hold a meeting just to update people.”

“If you’re already meeting for worthwhile topics, you can do a quick update,” says Axtell. You might say at the end, Is there anything that the group needs to be aware of before we leave? Is there something going on in your department that others needs to be know about? “But if you’re only meeting to transfer information, rethink your approach. Why take up valuable time saying something you can just email?” says Axtell.

And update meetings aren’t just time-wasters. Gino explains that research by Roy Baumeister, Kathleen Vohs and their colleagues suggests that we have a limited amount of what they call “executive” resources. “Once they get depleted, we make bad decisions or choices,” says Gino. “Business meetings require people to commit, focus, and make decisions, with little or no attention paid to the depletion of the finite cognitive resources of the participants — particularly if the meetings are long or too frequent,” says Gino. She finds something similar in her own research: that “depletion of our executive resources can even lead to poor judgment and unethical behavior.” So if you can avoid scheduling yet another meeting, you should.

7. “Always set an agenda out ahead of time – and be clear about the purpose of the meeting.”

It’s hard to imagine more sound advice about meetings. Axtell and Gino agree that designing the meeting and setting an agenda ahead of time is critical. “You should explain what’s going to happen so participants come knowing what they’re going to do,” says Axtell. In her book, Sidetracked, Gino talks about how lacking a clear plan of action is often why groups get derailed in decision-making. “Having a plan gives us the opportunity to clarify our intentions and think through the forces that could make it difficult for us to accomplish our goals,” she says.

There is a lot of data out there that shows how much time we’re all wasting in meetings. But you don’t need research to prove what you intuitively know. Next time you need to bring a group together, do the best you can to make it a good use of everyone’s time—including your own.

July 3, 2015

What Apple, Lending Club, and AirBnB Know About Collaborating with Customers

The idea of “co-creating” with customers has been circulating for years, but until recently few companies effectively exploited its power or understood its contribution to the bottom line. True, customers can customize their M&Ms, build their own bikes with Trek Project One, create unique doors for their home at Jen-Weld, and design their own Nike running shoes. But these co-creation models produce only one-off physical goods, and none represents a fundamental shift in how these companies create value; they’re peripheral to the core business.

Today, however, by exploiting new digital technologies, firms like Apple, Lending Club, and AirBnB have made customer co-creation of value central to their business models and in doing so now rank among the world’s most innovative and valuable firms. Our research indicates that companies that make their customers partners, and share the value created, lead the pack on revenue growth, profit margins, capital efficiency, and enterprise value. We call these companies Network Orchestrators. By leveraging customer networks and their tangible (e.g. homes and cars) and intangible (e.g. expertise and relationships) assets, firms can gain these advantages of the Network Orchestration business model.

How, then, do firms cultivate these valuable customer networks? It starts by understanding customers’ affinity with the brands.

Four levels of affinity

Through our research on network-centric businesses and our experience advising hundreds of companies we have developed a framework for understanding customer affinity.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

Most leaders are already working to deepen customers’ relationships—converting uninterested consumers (transactors) into passionate brand advocates (promoters). However, what these executives don’t fully appreciate is that the customer affinity spectrum extends far beyond promotion. Through co-creation, companies can access a deep well of customer capabilities, knowledge and assets.

Although the Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a market standard, customer promotion alone can’t sustain a co-creation model. Promoters might give you their dollars and promote your brand with their Tweets or Facebook “likes”, but today’s connected customers want to give, and receive, more. Creating models based on co-creation requires identifying the subset of customers with the right kind of brand affinity.

These four types of customers represent different levels of brand affinity:

1. Transactors: These customers have no loyalty to your brand. Although they may make purchases, they are unaware of or not swayed by your brand proposition and do not desire a relationship with your company.

Example: Carol owns a small business and needs a customer relationship management (CRM) platform. Overwhelmed with choices, she signs a one-year contract with the first salesperson that returns her call, planning to reevaluate next year.

2. Supporters: These customers are aware of your company and brand, and buy from you consciously. They support your company by purchasing regularly. However, they do not promote your brand and they may switch easily to other products.

Example: Jim’s firm has used the same CRM software for ten years. The functionality barely meets his needs, but he hasn’t yet had the time to invest in finding a better solution so renews his contract, but only on a month-to-month basis.

3. Promoters: These customers frequently purchase your products or services and are very loyal. Their affinity is strong enough that they advocate for your company to their networks helping your company grow through word-of-mouth.

Example: Ann just switched to a new CRM platform and has heard from the sales team that it saves time and increases conversion. Happy about these results, Ann recommends it to all of her followers on social media.

4. Co-creators: These customers are so engaged with the brand that they share in the value creation, and receive value back. They create and offer their own assets, knowledge and relationships in exchange for a share of the value generated—including revenue and profits.

Example: Jacob loves his CRM software and has become an expert in its use. He decides to use its open source platform to create add-on apps that he believes will be useful to other users and posts it on the company’s app exchange.

A significant shift happens when customers reach co-creation status with a brand. With Transactors, Supporters, and Promoters, the company is responsible for fulfilling the customers’ needs. However, when a company co-creates with its customers (usually by providing a technology platform which facilitates interactions and transactions), company and customers create shared value.

To help you better understand where you and your customers fall on the customer affinity spectrum, take our Customer Type Assessment. While there are many ways to segment customers, this type of segmentation is particularly useful because of its implications for the business model.

Companies that co-create

Let’s look at three companies that leveraged digital capabilities to build customer co-creation into their business models. Each has moved beyond allowing customers to design their own products, to share value by acting as a platform to promote the customer networks’ talents and assets.

Apple’s Developer Network: Apple provides the platform; companies and individuals provide the applications. They each receive a portion of the value created, whether revenue, awareness, or utility. Over its lifetime, the app store has generated more than $25 billion for developers.

Airbnb.com: Airbnb provides the online database and some additional services; their partners provide the good sold—the properties for lease. Revenues are shared and together Airbnb and its “hosts” have built a company that was most recently valued at more than $25 billion, more than the value of Hyatt Hotels.

Lending Club: This peer-to-peer lending platform connects would-be borrowers and lenders. All of the “products”—loans and investments—are created and provided by its members. Lending Club went public in 2014 and its enterprise value is nearly $9 billion.

Co-creation advantages

Customer co-creation is central to the Network Orchestration business model. Our research shows that companies that facilitate a network of co-creators deliver shareholder value two to four times greater than companies that don’t leverage co-creation business models. We see four main reasons for this value gap:

Greater revenue growth: As co-creating partners, customers have an incentive to help grow the business. Your success is theirs, whether the rewards are monetary or intangible. Co-creation is less a measure of “customer loyalty” than an indicator of “reciprocal loyalty,” where both parties serve each other.

Lower marginal cost: Your customer co-creators bring an entirely new set of assets to the company, at a very low or near-zero cost (see Rifkin’s The Zero Marginal Cost Society). They may be willing to share their opinions, skills, relationships, and even their real assets (cars, apartments, etc.) for the right incentives and shared value.

Improved customer insight: The increased customer intimacy that comes with co-creation deepens your understanding of your market, enabling you to serve it better. When customers co-create and have a vested interest in its success, they are more willing to share personal data and other assets with it.

Increased organizational flexibility: A network of customer co-creators increases the company’s adaptability and speed. This network is distributed and self-organizing, which makes it highly responsive to changing customer needs. When a new vacation hotspot emerges, Airbnb does not need to change its supply chain or purchase new properties; instead its co-creation network naturally expands to satisfy the demand.

Five steps to co-creation

Customers cannot be coerced into co-creating. They must be eager participants in the value equation. To drive co-creation, you must invite your customers into the value equation. We recommend a five-step process called PIVOT: Pinpoint, Identify, Visualize, Operate, and Track.

1. Pinpoint where your customers currently lie on the customer affinity spectrum and the areas where they will be most interested in co-creating. Evaluate your leadership team’s openness to co-creation as well.

2. Identify the characteristics of your key customer groups, including their level of engagement, their unmet needs, and any tangible or intangible assets that could be leveraged in a co-creative relationship.

3. Visualize a new business model where your customers co-create with your firm to help meet their own needs. Based on their characteristics, design a system that will incent them to participate, with a particular emphasis on leveraging digital technologies as the platform.

4. Operate your new co-creative digital business. Fund it, recruit the right digital talent, and insulate it from the politicking of the broader firm. Experiment and iterate rapidly.

5. Track the performance of your co-creative customers and the value they add. Add new metrics to standard financial reports, including the revenues customers generate and the costs saved through their participation.

As written, these five steps seem relatively simple, but we all know they are far more difficult in practice. The biggest hurdle to co-creation is usually shifting the leadership team’s mental model. Most leaders are so accustomed to owning the value creation process that they cannot imagine the customers as active participants, instead of passive recipients.

Think of it this way: Does the hospital ask patients to help design their own healthcare? Do professors enable college students to contribute to the curriculum? Do auto manufacturers allow drivers to co-create their next car? In general, no. But they might see a dramatic change in engagement and innovation if they did.

Giving up control, and sharing rewards, may seem terribly risky, but it is the key to the co-creative business models that generate unprecedented value with lower marginal costs, and greater profits. It’s unwise to delay this journey any longer. Your customers are waiting.

Susan Corso contributed to this article. She is a leadership consultant with OpenMatters.

Digital Tools to Make Your Next Meeting More Productive

This spring, I wrote about how the right digital tools can help you work more efficiently before, during, and after a meeting. Let’s look more closely at how to use the tools during your meeting to better lead the conversation.

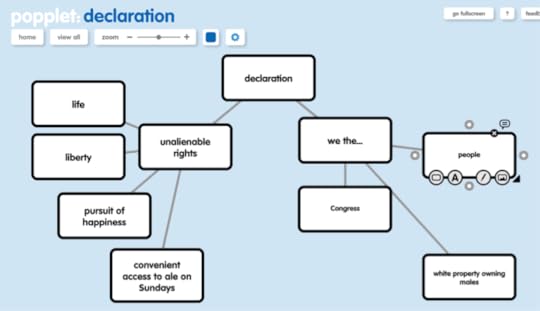

For an example, I’ll use the Second Continental Congress, one of the world’s most productive off-sites, which resulted in the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Here are tools you can use to:

Inspire new thinking. Your meeting outcomes will only be as good as the thinking that goes into them. But huddling around a PowerPoint presentation is hardly a recipe for inspiring bold new ideas. Instead, think about using a collaborative visual tool like Popplet to share ideas, so that you can reorganize them on the fly.

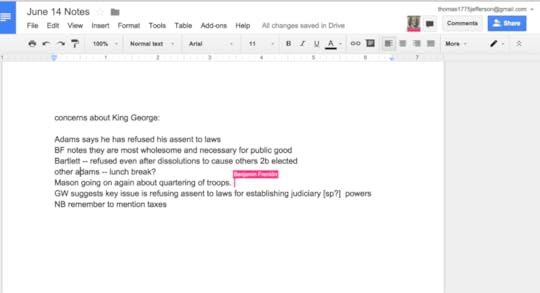

Engage multiple voices. Not everybody is equally comfortable speaking up during a meeting. To surface the best ideas, you need to hear from as many people as possible. Real-time collaborative note-taking — which you can accomplish using a tool like Google Drive — ensures you actually capture everything that happens during a meeting. Best of all, it acts as a back channel that allows people to add comments and ideas even if they’re not comfortable speaking up (or if they’re working remotely!). And if the Founding Fathers had had access to Google Drive, their resulting document would have been a whole lot more legible.

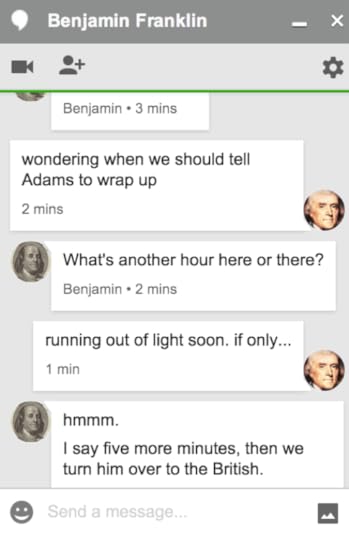

Coordinate for results. One of the biggest obstacles to achieving a tangible meeting outcome is the way conversations tend to veer off course. A backchannel chat (using a tool like Skype or Google Hangouts) provides a way of discreetly asking someone to let the conversation move forward, or of checking in with other meeting attendees to see if they feel like your meeting has lost focus. I’m sure that’s something the Founding Fathers would have welcomed, particularly while stuck in a late June meeting clad in wool coats.

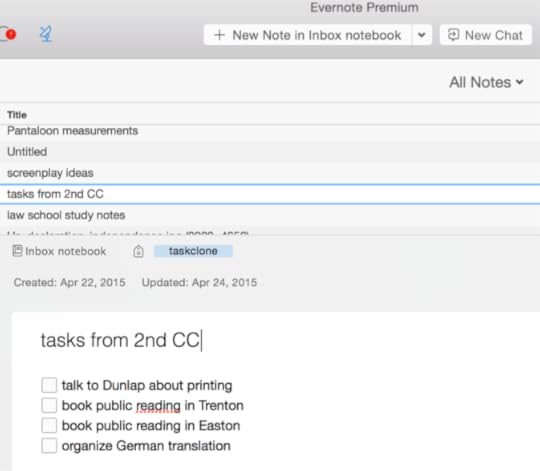

Convert action items to tasks. Once you leave a meeting, it’s easy for action items to fall by the wayside. It really helps if everyone in a meeting actually puts their action items into their task manager — something that’s a lot easier with TaskClone. A commenter on my post about digital meeting tools put me onto this service, which can scan Evernote to find any action items and then import them into your favorite task management tool.

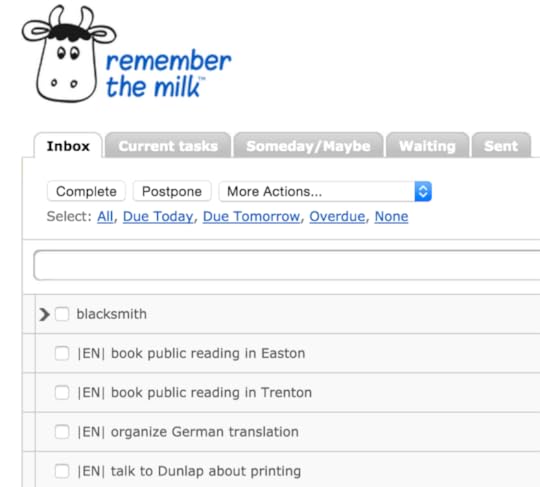

If Thomas Jefferson had taken his meeting notes in Evernote, TaskClone would also have made it easy for him to import them into his task list in Remember The Milk.

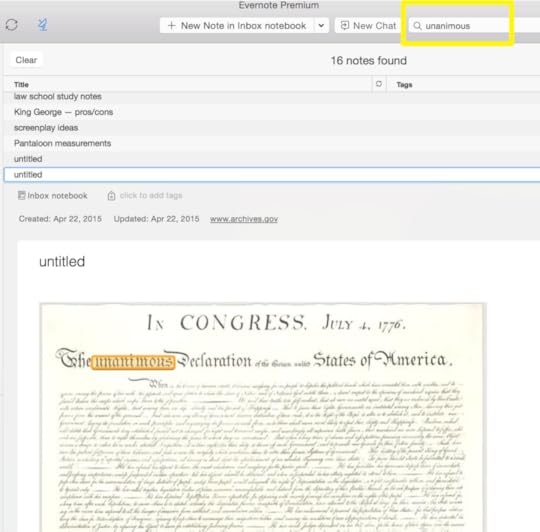

Access your outcomes. Too often, we leave meetings with a tangible outcome, only to lose it in the digital morass. Even if you generally take your meeting notes in Evernote or another digital note-taking program, you may still have trouble tracking down that brilliant brainstorm that occurred on a pile of post-its, the inspired idea you wrote in your paper notebook, or the meeting notes written on a flipchart. That’s why it’s handy to snap any written output and add it to Evernote, so that it becomes searchable. Any Founding Father who added the Declaration of Independence to his Evernote file would have been able to find the document in an instant.

Most meeting attendees count themselves lucky if they leave the room with clear action items, let alone a tangible work product that survives for more than 200 years. But making smarter use of digital meeting tools may get us a little bit closer to that dream.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers