Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1279

June 25, 2015

Local R&D Won’t Help You Go Global

Kenneth Andersson

In order to expand, digital businesses need to pivot to new and promising growth areas. Often that means making forays into new fields and taking on seemingly intractable business problems. Consider Google’s venture into maps or SAP’s Future Factory initiative, far-reaching projects that required new ideas from different places. The development of new technologies is complex and challenging, and to come up with the next big innovation, businesses must think — and operate — in new ways.

Given these challenges, it’s surprising to see younger firms trying to grow by tapping the same R&D resources that fueled their initial successes. Facebook and Salesforce.com, for example, conduct much of their R&D locally. Like a lot of young digital companies in the U.S., there is little evidence that they harness knowledge in fast-growing global centers of excellence such as Bangalore or Tel Aviv. However, in order to grow, companies need to draw on the world’s best knowledge, wherever it lives geographically.

Over the past two decades, we have seen a shift in the way R&D is dispersed around the world. Traditionally, multinationals have conducted their research in developed nations: IBM has an R&D center in Tokyo, for example, and Google’s European engineering hub is in Zurich. But more recently, emerging-market locations have featured prominently in global firms’ technology portfolios. Multinationals’ knowledge-intensive activities have set in motion virtuous cycles that have resulted in the development of innovation clusters in places including Shanghai and the aforementioned cities in India and Israel.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

What is so important about this trend is that global knowledge networks increasingly braid together R&D activities conducted in advanced and emerging economy locations. As the Economist Intelligence Unit has noted, emerging-market R&D is taking the lead on global projects because it has the best ideas to offer, rather than the cheapest. In our research, we call this “competence-creating” work. The more ideas that are brought to bear, the better chance companies have of solving big problems, and in a connected world, those ideas can come from a variety of places. As Julian Birkinshaw and Neil Hood noted in the pages of HBR, distance may actually be an asset.

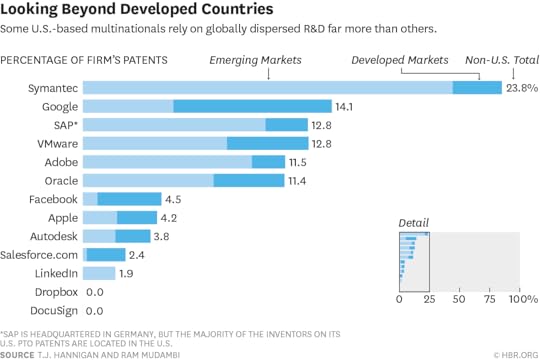

The global search for ideas is especially important for digital businesses. When we examine the patents of a series of established digital-technology companies, a clear pattern emerges: Certain companies rely on globally dispersed R&D far more than others. The more software-driven the company, the greater the reach into global R&D networks. To us, that demonstrates that all digital companies have an enormous opportunity as they mature and look to develop new areas of technology.

To be sure, a number of highly successful American companies have managed to pivot to new directions while keeping their R&D close to home. Apple’s design studio is nestled snugly in its Cupertino, California, campus. Autodesk tries out manufacturing prototypes on wholly owned factory floors in Manhattan. Our research on patents shows that fewer than 5% of Apple’s and Autodesk’s patents list inventors outside the U.S. (see the chart).

By contrast, Symantec (which is all digital) and SAP (whose businesses have both physical and digital components) source knowledge much more widely and draw on emerging-market locations. Nearly a quarter of Symantec’s, and more than 10% of SAP’s, patents come from outside the U.S., our research shows. And the vast majority of those patents come from emerging markets.

Symantec’s Centre of Innovation in Chennai, India, was conceived of not as an outpost of local adaptation but as a source of new-product innovation for the company as a whole. The company’s stance on innovation is truly global, with engineering teams collaborating among its network of locations. The Indian location was attractive on account of its strong engineering talent. A few years ago, a Symantec VP, Shantanu Ghosh, pointed out the “amount of true innovation from our India Innovation Centers.”

Meanwhile, SAP has been cultivating a worldwide R&D network through its Global Ecosystem program, sourcing ideas from geographically dispersed individuals and organizations and promoting diversity. The R&D coming out of SAP’s emerging-market locations has global significance: Its technology center in Tel Aviv has leaped to the forefront of innovation. SAP’s co-CEO Jim Hagemann noted in 2011 that the R&D group in Israel has “turned into a sort of front line where new ideas are tested out and turned into technology, and it is succeeding well.”

Indeed, firms whose products are mainly intangible have the geographic flexibility to draw on knowledge from all over the world. Because their businesses don’t rely on physical materials such as tangible prototypes and lab equipment, collaborating scientists don’t need to be physically colocated.

Yet there’s a group of young U.S. digital businesses that, while often growing at breakneck speed, haven’t embraced the promise of globally dispersed knowledge; their R&D is still highly localized. In our research we explored a series of such young firms, from those on the cusp of exploration (Facebook, Salesforce.com, and LinkedIn) to a series of “unicorns”: fast-growing start-ups such as Dropbox and DocuSign that have reached valuations north of $1 billion. The common thread among them? None have yet seized the opportunity that global knowledge hotspots can provide.

Facebook has recently looked beyond Silicon Valley, but its research remains in the developed world. Its London office, which represents its first international move, has a mandate to mirror the engineering undertaken at HQ. Salesforce.com, as a cloud-based service provider, believes in platform-driven R&D efficiencies, which demand a centralized engineering approach.

Emerging markets present their own challenges, of course. Companies risk rapid staff turnover and the leakage of key knowledge. Distance (cultural, geographic, technological) could lead to substandard work. A 2011 McKinsey study showed that smaller and younger firms are wary of global R&D plays. However, the same study showed that the challenges were well worth it: All high performing companies in the study did at least some R&D abroad.

Ultimately these companies will face important decisions regarding idea exploration. Growth requires a broad set of new ideas. Our research suggests that they will have to reach beyond technological capabilities and learn how to deal with the challenges of global knowledge sourcing — including addressing the many problems they will confront in emerging markets.

What VCs Can Teach Executives About What Drives Returns

Executives tend to turn toward fellow executives for advice. Historically, best practices on hiring, manufacturing, and sales all emerge when talking to someone else who has sat in the trenches. But the ways we do business have changed dramatically over the course of the last decade, and it’s become more necessary to reach outside of your expertise – or industry — to gain perspective on your business and leadership style.

In this era of continuous digital transformation, every manager can benefit from learning a few best practices from the boutique industry of venture capital. Motivating people to take moonshots, predicting changes, and making transformational bets are what the venture industry is predicated on. Great investors understand these things drive return and have structured their work lives to optimize these outcomes. As industrial era companies, from Mattel to GE, start to transform into software-enabled businesses, executives stand to benefit from understanding three principles that drive venture investors.

Returns are defined by home runs, reputations are defined by singles

Venture capitalists never expect their work to be repaid evenly. It’s a well-known characteristic of the industry that “home runs” define investor performance. Being an early investor in Uber or Facebook, for example, makes up for many other investments in unsuccessful businesses. But the best VCs also know that in order to hit home runs you need to have a good swing. That’s why they continue to support their entire portfolio of companies and entrepreneurs.

With the growing significance of software-enabled businesses, managers within companies of all sizes will see some projects scale enormously and drive performance — while others won’t be as impressive. When I was at SAP, we would outline around 10 key initiatives for the company on an annual basis. Not all of them would turn into meaningful businesses. However, if one or two of those did, it was transformative.

The challenge this creates is the potential for two very different types of employee experiences. A few employees will be seen as world conquerors, driving massive return for the business. The majority, on the other hand, will feel deflated after seeing their initiatives fail or their efforts unappreciated.

Execs need to take a page out of the VC playbook and ensure that they’re spending the right amount of time supporting, enabling, and advocating on behalf of all the company’s initiatives — not just the home runs. In order to keep making bets on what could be big businesses, execs need to create a culture that rewards all purveyors of strategic long-shots. Sometimes getting your hands dirty and trying to save a stalled project can inspire the sort of sentiment that leads employees to take more shots at creating value for you.

The best teammates don’t mind the hard questions

A lot of ideas sound great at first. I’d love a software-based assistant that anticipates my needs and schedules meetings accordingly. I’d love a CRM system that coordinates outreach among all my team members. I’d love an application that allows me to take a photo of my food and tells me how many calories I’m ingesting. But even the best sounding ideas often have little substance beneath them.

It’s far easier to figure that out when you’re surrounded by people who ask the tough questions. The best performing VC teams ask hard-hitting, but respectful, questions of one another. They help each other uncover the most challenging issues with any investment, so they can analyze them accurately and make a decision. Partners ask whether individual bias or affinity for a given founder is driving a decision. They dig deep into the assumptions of a potential investment, asking bluntly whether things like the unique behavior of Manhattan residents translate to other cities. And with every hard hitting question, the team finds itself in a better position to make the right decision faster.

Many corporations have cultures where asking pointed questions is viewed negatively. Politics dominates the psyches of employees, who have to carefully calculate whether to call out a problem, discuss it in private, or ignore it entirely. Your company can’t take advantage of every new opportunity, so to find the ones worth your time, you have to encourage senior management to ask questions and disprove assumptions. The folks who are willing to ask and answer the tough questions are the ones who keep you sharp, keep you moving forward, and keep you honest.

The future is far out, until it isn’t

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that there are two ways you go bankrupt: “Gradually. Then suddenly.” Binary events are like this. You’re profitable, then you’re not. You’re growing, then you’re not. You’re employed, then you’re not.

Every VC understands this from the other side of the equation. They look at tiny businesses and see a future world where they are significant. In the eyes of most onlookers the shift from irrelevant to meaningful happens in the blink of an eye. A fast-growing company might have just $5 million in revenue – a drop in the bucket for a global corporation. But two years later, it could have $50 to $100 million, and suddenly everyone is paying attention. That growth can even happen as companies scale. Just look to Tesla as an example. In 2012, Tesla had just over $400 million in revenue. In 2014, it was catapulted into the limelight and had surpassed $3 billion.

The future comes quicker than we think. When executives forecast on 3-5 year time horizons, they focus on the things that they can seemingly control. Unfortunately, focusing too heavily on near-term issues often leaves you unprepared for the future. By the time you start planning for a change on a three-year cycle, other companies will have been addressing those issues for years. Instead, it’s a much better strategy to acknowledge the future state of the world and focus your planning cycles on the inevitable changes you believe are going to impact your market. Mark Johnson, of Innosight, calls this planning based on your “Future State.” It a necessary piece of venture investing. But it’s becoming ever more critical for executives trying to adapt to an increasingly digital world.

During my time as an operator within SAP, I wish I’d truly appreciated these three things. Each amplifies your ability to execute, transform, and lead in an era defined by change and opportunity. To build teams that are willing to take home-run swings again and again, quickly identify what’s working and what’s not, and ensure long term opportunities aren’t missed, managers would do well to learn these lessons from VCs.

The C-Suite Needs a Chief Entrepreneur

The best CEOs are excellent at growing and running a company within a known business model. What they don’t do well enough is reinvent and innovate. It’s not because they’re incompetent, they just fall short at the task.

Sure, there are exceptions who are both visionary CEOs and innovators — Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, for example — but there are very few companies that can stomach that sort of leadership.

So if the CEO isn’t someone who can innovate, then who should? It’s a question that I’ve discussed with Lean Startup founder Steve Blank and business thinkers such as Yves Pigneur, Henry Chesbrough, and Rita McGrath. We believe that CEOs need a partner for innovation inside their companies, someone who will create and defend processes, incentives, and metrics that encourage radical ideas and find new areas for growth. It’s an executive who can help large companies reinvent themselves while they’re still successful. And this new role needs to sit in the C-suite.

You could call this person the Chief Entrepreneur (CE) — someone who can lead the future of the company while the CEO takes cares of running the existing business. This is a huge divergence from the traditional norm for chief roles, but the CE is a necessary position of power to ensure that a company innovates.

But how do you hire for the role? Where do you look? What qualifications must the candidate have? I’ve written up a job description below to make the search easier for Fortune 50 companies:

Are you a Chief Entrepreneur?

Fortune 50 company seeks a Chief Entrepreneur who will build the future. The Chief Entrepreneur will be responsible for managing a portfolio of entrepreneurs who experiment with new business models and value propositions. The candidate is someone with a passion for taking calculated risks. This is not a CTO role or a role that reports to the CEO. The Chief Entrepreneur is an executive as powerful as the CEO, with clear leadership over radical innovation within the company.

Look at the list below and see if any of this connects with you:

You’re passionate about building businesses. You produce growth engines with calculated bets, not “wild-ass gambles.”

You believe anything is possible. You persevere. You have the charm, charisma, enthusiasm, hard work, and marketing mind to encourage and drive your teams to think anything is possible.

You’ve built a $1 billion+ business from nothing. You’re especially valuable if you’ve met these figures in a large corporation.

You’re comfortable with uncertainty. You don’t fear failure. You see failure as an opportunity to learn and iterate toward a solution.

You’re tremendously diplomatic. You address conflict head-on with one focus in mind: secure the money and resources you need to test your ideas.

Sound like you? OK, now let’s consider your day-to-day tasks.

What are your responsibilities?

Build the future for the company. We cannot stress this enough. The CE is responsible for developing new business models and value propositions for the company’s future growth.

You guide and support your own team of entrepreneurs. You’ve been here before and you have knowledge to share. Your team will be searching for and validating business models and value propositions around opportunities for growth. This means managing entrepreneurs who can navigate trends and market behaviors.

Design/construct a space for invention. You are responsible for creating the habitat for your team to experiment, fail, and learn. This is an additional culture where ideas can be thoroughly tested. You must defend the culture, processes, incentives, and metrics that are born in this space.

Introduce innovation accounting. You must develop a new process that measures whether you’re making progress in building new businesses. How are your experiments helping your team to learn, reduce uncertainty and risk, and move forward?

Establish and nurture a partnership with the CEO. You will have to work with the CEO to ensure resources and assets are available to validate or invalidate your ideas. You will be responsible for building a partnership to discuss progress and share new ideas. Communication will be key to this partnership because the CEO is the person who can help finance your future experiments. You will also recognize the importance of handing over a validated business model that demonstrates opportunities to scale.

Report your progress directly to the Executive Chairman of the board of directors. You do not work for the CEO, or alongside the CTO, CIO, and CFO. These roles are mandated to keep the existing business in good shape. If the CE reported to the CEO, then the CEO could veto potential ideas in order to reserve resources and safeguard the company against failure.

Today’s corporate world needs more ambidextrous organizations: companies that execute and innovate at the same time. This setup will be hard to understand and realize because of the immense power that the CEO role has held for decades. But as Steve Blank points out, every large company must face the reality of continuous innovation and disruption or risk becoming obsolete.

There’s no doubt that the CE and CEO are going to experience conflict. But with a bit of patience and perseverance, this new role can be successfully integrated into an existing corporation. Potential CEs may already exist in many companies — we just don’t pay attention to their traits or give them the chance to lead innovation. This person might even be you.

A Look Inside Lockheed Martin’s Space-Age Operations

At Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company, we have the privilege of working for ambitious customers; their plans include missions to Mars, examinations of asteroids, and scientific explorations that push ever deeper into the solar system. Whether military, government, or commercial, they are doing exciting work, and to the extent they succeed, we all benefit – from stronger national security, better communication and navigation, more accurate weather and climate measurement, and greater knowledge of our universe.

Our job is to deliver the cutting-edge technologies they require. For example, as part of NASA’s Orion program, we’re responsible for making a spacecraft that will ultimately take the first humans to Mars. And, especially in recent years, as prolonged global economic challenges have rippled through the aerospace industry, we also need to make those technologies more affordable. That requires constant innovation, in both our products and our own operations.

One way we’ve responded is with expanding the use of virtual reality and 3D simulation to design satellites and spacecraft. Before, ideas and plans for space vehicles took shape on paper. No longer. By creating fully realized concepts virtually, we are able to test and refine designs, and spot errors while they are much easier and less costly to fix – before the physical build. Another line of innovation has us leveraging the growing capabilities of additive manufacturing. Given the nature of our business, the economics are compelling to move quickly beyond just creating prototypes with 3D printing. Already today, we print actual parts for satellites; one day, we will print an entire satellite.

More than any single design or manufacturing technology, however, it’s the integration of these technologies into a seamless, Digital Tapestry that is proving most valuable. We’ve created an end-to-end electronic domain that connects all elements of product development – conceptualization, design and analysis, simulation and optimization, manufacturing, assembly and test, and operations and sustainment. Because the tapestry weaves these together, we can now, for example, 3D-print satellite parts directly from the original computer design model. With no chance of information being lost in translation, the process minimizes waste and cuts cycle time.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

These new digital capabilities are powerful, but we always emphasize that the power is going into the hands of the people who use them. A fully integrated Digital Tapestry enables them to be more innovative, because it allows them to collaborate, simulate, create, communicate, and incubate ideas.

Collaborate. We know our teams perform best when they achieve “collective genius.” When we collaborate, we expand our range of ideas. Part of this comes from tapping into individual members’ different talents, perspectives, and experiences – so we must be inclusive. Another part comes from sharing information. Through the Digital Tapestry, system development teams working across all engineering disciplines, along with manufacturing, procurement, and quality, view the same information, move easily between steps, and take collaboration to a new level.

Simulate. As mentioned above, virtual reality and 3D-simulation technology are changing how we design systems; they allow designers to see at angles and through layers that they wouldn’t be able to in a two-dimensional presentation. Lockheed Martin has several virtual laboratories; the one I am most excited about is called CHIL, for Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory. In this Denver facility, we outfit engineers and manufacturers in VR equipment and let them “step into” new spacecraft designs. Once inside, they appear at human scale, and are able to try out ideas and make adjustments together — and all the while, the system produces a constant stream of automatically updated specifications. Using the CHIL, engineers have been able to work on processes virtually before releasing them to manufacturing; identify bottlenecks and worker challenges before they could become issues; improve resource utilization and material flow; improve producibility; reduce rework; and mitigate program risk.

Create. A company that depends on its people’s creative capacities should find ways to keep building them. Recently, more than 150 of our employees took part in an additive-design competition where we amped up that old, familiar engineering exercise: the egg drop. Teams had to show up with a 3D-printed solution, designed and built in-house, capable of protecting their egg from the impact of a five-story drop. As well as inspiring a lot of creativity, the competition reinforced important lessons, such as the need to understand design restrictions, and to investigate the available materials and how they changed tolerances and properties.

Communicate. Collaborative creativity depends on rich exchanges of information and opinion, and the digital environment we build must allow for that. Offline, too, communication skills are vital to exchanging ideas on complex matters. In particular, we try to put the emphasis on good listening. That means listening to customers to truly understand their needs, listening to each other as we suggest ideas or recount relevant experiences, and even listening to ourselves when we have a gut instinct about something but may feel hesitant to speak up.

Incubate. Innovation isn’t as simple as having an “aha” moment — there has to be a pathway for taking creative spark to commercial viability. To help pave the way, we have established Innovation Garages at our major sites which serve as incubators for our engineers’ best ideas. When they have a notion for a project, they present it to the leadership team, which then provides funding for teams to mature their concepts. The objective is to move from idea to rapid prototype in about 16 weeks. In one extreme case, a team assembled a cube satellite over just one weekend that constituted an important proof of concept. It showed how cube satellite systems could be developed using open-source and off-the-shelf technologies already commercially available.

Importantly, just as digital capabilities enable these elements of innovation, they also put new emphasis on certain qualities we need in our workforce. Increasingly, these are the strengths we are seeking in our people — that they be collaborative and imaginative, comfortable with working in virtual worlds and with listening for richer understanding. We need people with entrepreneurial spirit, motivated not just to have bright ideas but to get them to the launch pad.

We stand on the cusp of a new space age, and our innovations today will enable our customers to venture into new territory. With all our functions, from design engineers to the production line, digitally connected, using the same data and ensuring seamless operations, we will produce new solutions, solve implacable problems, and change the world. With a Digital Tapestry in place, it will become more clear than ever: stratospheric success always comes down to people.

Stop Worrying About How Much You Matter

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

For many years — almost as long as he could remember — Ian* owned and ran a successful pub in his small town in Ireland. Ian was well-known around town. He had lots of friends, many of whom he saw when they came to eat and drink, and he was happy.

Eventually, Ian decided to sell his establishment. Between his savings and the sale, he made enough money to continue to live comfortably. He was ready to relax and enjoy all his hard work.

Except that almost immediately, he became depressed. That was 15 years ago and not much has changed.

I’ve seen a version of Ian’s story many times. The CEO of an investment bank. A famous French singer. The founder and president of a grocery store chain. A high-level government official. And these are not just stories — they’re people I know (or knew) well.

They have several things in common: They were busy and highly successful. They had enough money to live more than comfortably for as long as they lived. And they all became seriously depressed as they got older.

What’s going on?

The typical answer is that people need purpose in life and when we stop working we lose purpose. But many of the people I see in this situation continue to work. The French singer continued to sing. The investment banker ran a fund.

Perhaps getting older is simply depressing. But we all know people who continue to be happy well into their nineties. And some of the people who fall into this predicament are not particularly old.

I think the problem is much simpler, and the solution is more reasonable than working, or staying young, forever.

People who achieve financial and positional success are masters at doing things that make and keep them relevant. Their decisions affect many others. Their advice lands on eager ears.

In many cases, if not most, they derive their self-concept and a strong dose of self-worth from the fact that what they do and what they say—in many cases even what they think and feel—matters to others.

Think about Ian. If he changed his menu or his hours of operation, or hired someone new, it directly affected the lives of the people in his town. Even his friendships were built, in large part, on who he was as a pub owner. What he did made him relevant in the community.

Relevancy, as long as we maintain it, is rewarding on almost every level. But when we lose it? Withdrawal can be painful.

As we get older, we need to master the exact opposite of what we’ve spent a lifetime pursuing. We need to master irrelevancy.

This is not only a retirement issue. Many of us are unhealthily—and ultimately unhappily—tied to mattering. It’s leaving us overwhelmed and over-busy, responding to every request, ring and ping with the urgency of a fireman responding to a six-alarm fire. Are we really that necessary?

How we adjust — both within our careers and after them — to not being that important may matter more than mattering.

If we lose our jobs, adjusting to irrelevancy without falling into depression is a critical survival skill until we land another job. If managers and leaders want to grow their teams and businesses, they need to allow themselves to matter less so others can matter more and become leaders themselves. At a certain point in our lives, and at certain times, we matter less. The question is: Can you be OK with that?

How does it feel to just sit with others? Can you listen to someone’s problem without trying to solve it? Can you happily connect with others when there is no particular purpose to that connection?

Many of us (though not all) can happily spend a few days by ourselves, knowing that what we’re doing doesn’t matter to the world. But a year? A decade?

Still, there is a silver lining to this kind of irrelevancy: freedom.

When your purpose shifts like this, you can do what you want. You can take risks. You can be courageous. You can share ideas that may be unpopular. You can live in a way that feels true and authentic. In other words, when you stop worrying about the impact of what you do, you can be a fuller version of who you are.

That silver lining may be our anti-depressant. Enjoying the freedom that comes with being irrelevant can help us avoid depression and enjoy life after retirement, even for people who have spent their careers being defined by their jobs.

So what does being comfortable with the feeling of irrelevancy — even the kind of deep irrelevancy involved in ending a career — really look like? It may be as simple as doing things simply for the experience of doing them. Taking pleasure in the activity versus the outcome, your existence versus your impact.

Here are some small ways you might start practicing irrelevancy right away:

Check your email only at your desk and only a few times a day. Resist the temptation to check your email first thing in the morning or at every brief pause.

When you meet new people, avoid telling them what you do. During the conversation, notice how frequently you are driven to make yourself sound relevant (sharing what you did the other day, where you’re going, how busy you are). Notice the difference between speaking to connect and speaking to make yourself look and feel important.

When someone shares a problem, listen without offering a solution (if you do this with employees, an added advantage is that they’ll become more competent and self-sufficient).

Try sitting on a park bench without doing anything, even for just a minute (then try it for five or 10 minutes).

Talk to a stranger (I did this with my cab driver this morning) with no goal or purpose in mind. Enjoy the interaction — and the person — for the pleasure of it.

Create something beautiful and enjoy it without showing it to anyone. Take note of beauty that you have done nothing to create.

Notice what happens when you pay attention to the present without needing to fix or prove anything. Notice how, even when you’re irrelevant to the decisions, actions, and outcomes of the world around you, you can feel the pleasure of simple moments and purposeless interactions.

Notice how, even when you feel irrelevant, you can matter to yourself.

*Not his real name.

How to Plan a Team Offsite That Actually Works

All around the world, teams large and small assemble at offsite locations to take a step away from their day-to-day work and build team spirit. Unfortunately, many team building offsites turn out to be ineffective, or worse. Sometimes, it’s because the sense of unity and cohesion that gets created when everyone is together having “fun” outside of the office doesn’t last long once everyone gets back to work. Other times, “team building activities” have the unintended consequence of bringing out competition and hostility between individuals instead of enhancing commitment and cohesion within the team.

In order to create a team-building offsite that will have positive, enduring effects, it’s helpful to think of offsite meetings as kind of a microcosm, or a “play within a play,” wherein the leader and the team use the stage to rehearse the new dynamics and norms that they want to perform back at the office or take on the road. It’s important to be mindful in scripting your team’s offsite that the same challenges and opportunities that you and your team are facing in general will come to the surface. For example, if the goal of the offsite is to encourage all team members to be more participative, it’s helpful for everyone to provide input into the structure and agenda for the meeting, and then to participate at the actual meeting. If the goal is to clarify roles and responsibilities, it’s useful to be very clear about everyone’s roles and responsibilities in preparing for the meeting, as well as during the meeting itself.

The paradox and the challenge of offsite meetings for leaders and their teams is that to raise the likelihood that the offsite will have a successful and lasting outcome, changes need to be made before the offsite even occurs. This kind of preparation makes progress much more likely. But getting all of this interdependent sequencing right is neither simple nor easy.

Some best practices can help. Here are some suggested “Don’ts and Do’s” for planning your next team offsite:

Don’ts:

Don’t let the team’s old dynamics constrain the new dynamics that you’re trying to create. For example, if members of your team are reluctant to speak up and challenge one another inside the office, don’t assume that they’ll magically feel more comfortable doing so just because they’ve gathered together at an offsite location. Consider randomly assigning people to argue opposing points of view, and encourage them to discuss and debate alternative perspectives or strategies.

Don’t focus too much on the strengths, development needs, or personalities of individual members of the team. Too often, offsite meetings involve each member of the team taking a personality assessment such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and then sharing their results with each other. While it is tempting to attribute team dynamics to the personalities and styles of individual members, it’s almost always the case that team interactions go beyond individual personalities and are impacted by factors such as stakeholder demands, the clarity of goals, roles and priorities, available resources, etc. How to collectively respond to the team’s overall challenges and opportunities should be a higher priority topic for discussion than how team members’ personalities may influence individual interactions. Focusing on individuals can be helpful at times, but comes at the cost of focusing on the team as a whole.

You and Your Team

Leading Teams

Boost your group’s performance.

Don’t abdicate your authority, or send mixed messages about your role. If you are the leader of the team, you will also be expected to exercise at least some leadership or decision-making in the “play within a play” at the offsite. Pretending that you are simply an equal member of the team during the offsite will not be credible or helpful to anyone, In order to empower your team, it’s best to be mindful of the leadership role you have, which enables you to delegate authority both at the offsite and thereafter.

Don’t have people dress up in military garb and hunt each other down in the forest, in the jungle, or anywhere else for that matter. Also, don’t get into go-karts and try to run each other off the track. And don’t do anything else that causes the team to engage in dysfunctional conflict or competition among individuals. Doing so will create dynamics that are “all against all” instead of the desired “all for one and one for all.”

Don’t force anyone to sing, or even to have to listen to, karaoke. “Trust falls” and singing Kumbaya are also best avoided, since trust falls can end badly, and very few people really want to sing Kumbaya. These kinds of activities can create the perfect storm of irony and cynicism among participants. Also, you and your HR business partner don’t want any embarrassing footage showing up on YouTube, do you?

Do’s:

Do be clear about goals for the offsite, and create an agenda that reflects and reinforces those goals. For example, in looking at its work, the team may want to do the following: 1) Engage in reflections about past performance to consider what the team has done well and what it could have done better; 2) Discuss and debate current opportunities and challenges; and 3) Create strategic plans for the future. The team may also want to set goals for how to do each of the above in a way that improves interactions at the meeting, e.g. to look at the past, present and future in a more open, constructive, participative, and forward-looking manner.

Do set ground rules. Make sure that everyone knows that the offsite should be a safe space where people can speak up and constructively challenge one another, and you, without any fear of reprisal. It’s also helpful to pledge confidentiality, meaning that the content of what is said at the offsite is for you and your team alone, and will not get shared with others back at the office — unless the team reaches a consensus about authorizing any specific messages or information that will be communicated.

Do gather anonymous input and suggestions. When a team has a given pattern of interactions, it may be difficult for team members to suggest how to change this pattern without implicitly or explicitly challenging one another, or you as the leader of the team. Soliciting anonymous suggestions about what should or should not be on the agenda can yield better choices for you and the team. Hiring an outside facilitator can also be helpful in this regard, as he or she can interview team members and gather their feedback and suggestions for both the structure and the content of the planned offsite.

Do plan activities that actually build the team. One activity that I’ve found genuinely builds a sense of interdependence and collaboration is cooking a meal together, and then eating it together as a group. At some primitive level, people that we hunt or gather with, cook with and then eat with become our allies rather than our adversaries. Public service and volunteer projects, such as fixing up a school or playground, or building housing for the needy, can also build team spirit while giving back to the community.

Do build in process reflection time. Towards the end of the meeting, ask yourself and your team “Have we achieved our goals during this offsite, in terms of tasks and interactions, processes and outcomes? Did we create a new, more effective pattern of communication and collaboration, or of discussion and debate? Did I effectively lead the meeting? Did we together successfully create a “play within a play” that sets a positive precedent for new ways of interacting going forward?”

Do schedule follow-up. The most common complaint about team building offsites is that there is no follow-up, or insufficient follow-up, that any progress that has been made turns out to be temporary, and that any goals that have been set fall by the wayside. Scheduling a follow-up offsite, or at least a check-in meeting, three months, six months or a year after the initial offsite can help ensure that the team stays focused on making progress and sustaining positive change.

A successful team building offsite can provide an opportunity for the team to change old patterns and create and sustain new ways of communicating and collaborating, thereby changing the team’s dynamics for the better. That is to say, with the right inputs, preparation, process and follow-up, the temporary microcosm of the “play within a play” at the offsite location can have enduring benefits in the team’s overall interactions once everyone is back in the office.

June 24, 2015

You Don’t Need a Promotion to Grow at Work

As organizations run leaner and flatter, your ability to move up can stall much earlier in your career because, simply put, there’s no place to go. This is true whether you work for a corporation, nonprofit, or public agency. So what should you do when you reach that plateau and you’re only midway through your career? First, take stock. Do you enjoy and learn from your colleagues? Are you still energized by the mission of the organization? If the answer is no, it may be time to move on. But if the answer is yes, consider ways to grow on the plateau.

There are at least four proven approaches, all of which require that you ask what energizes you and what saps your motivation.

Lateral moves within your organization can be a great way to build new skills and relationships and get exposure to different products or services. You can explore new internal opportunities in a few ways, by: conducting internal informational interviews and meeting with a leader in another division or unit; taking on cross-cutting assignments involving other business units; or volunteering to move, say, from a business unit to a staff function that transcends units, such as finance, HR, or operations. Indeed, corporations like Kraft, consider role rotation standard for building well-rounded leaders, and actively invite promising line managers to take on staff jobs and the reverse. One senior leader at a professional services company, whom we’ll call Bronwyn, made the move from client-facing partner to chief operating officer. She was able to build on the analytics and change management insights she had brought to clients to help strengthen her own organization from the C-suite. In the process she developed managerial muscle in finance, human resources, governance, and IT, and, as a bonus, Bronwyn gained more flexibility in her schedule since she didn’t have external client demands driving her day-to-day work.

Reshaping your current role is another way to grow on the plateau. This calls for taking inventory of what you’d like to do more of, less of, and start doing. In concert with team members, you can redraw some boundaries to create stretch opportunities for others as you shift responsibilities to make space for your own new challenges. Two good places to look for these challenges are on your supervisor’s plate (Does she have areas of responsibility that you find interesting that could help free her up?); and in employee and customer surveys (Are there needs the organization isn’t meeting that you have the skills to respond to?) An expert in customer strategy at a consumer products company,we’ll call Sandra, She wanted to stay with the company, however, so she looked for gaps in service delivery across business units – from supply chain to e-commerce – and then volunteered to help colleagues fill those gaps. Sandra spent the next several years intrapreneurially expanding activities within her vice president role, learning more about the company and gaining new skills, relationships, and a reputation for innovation.

Expanding your influence through actively mentoring others, building internal communities of practice, or stepping up to represent your organization with external bodies can forge satisfying new frontiers without changing roles. Take the program officer at a youth focused nonprofit whom we’ll call Maria. She had nowhere to move up internally unless the executive director moved on. So she began collaborating externally with other organizations in her city that aimed to help immigrant youth plug into education, training, and job opportunities, growing her network and innovating her programs. By expanding her influence outside the organization, she gained credibility within. When the time finally came to name a new executive director, Maria was a top internal candidate in part because to her external network, and eventually got the job.

Deepening your skills is another way to build credibility and opportunity on the plateau. You can accomplish this on the job, by seeking out a mentor or volunteering for special projects; and off the job through formal leadership training. A medical service head we’ll call Robert, at a large public hospital, for example, volunteered to lead a performance improvement exercise for one of the hospital’s acute care groups. The results in improved patient care and timelier billing led hospital management to invest in sending him to an executive education course at a top business school, a qualification that eventually garnered him an offer to run a much bigger service line at the hospital, with close to 300 medical staff and $380 million annual budget.

Most 21st century managers will find themselves on a similar plateau somewhere along their career. Before succumbing to the temptation to jump to a new escarpment, consider whether branching out in place may be the best way to build your skills, both personally and professionally, for your next ascent.

Inventory Management in the Age of Big Data

We are on the verge of a major upheaval in the way inventory is managed. This revolution is a result of the availability of the huge amounts of real-time data that are now routinely generated on the internet and through the interconnected world of enterprise software systems and smart products. In order to make effective use of this new data and to stay competitive, managers will need to redesign their supply-chain processes.

I am talking about going beyond using traditional historical data on past sales and stockouts. It is now possible to link data generated by all product interactions (including orders, examinations, and reviews by actual and potential customers) and transactions generated by suppliers and competitors who connect via internet web sites and cloud portals. This data can be used by material-management systems to control ordering and distribution of products throughout a company’s extended supply chain. In addition, any data that is coincident with these product interactions, that is derived from the firm’s external environment, can also be accessed and linked.

How will this work? Advanced machine learning and optimization algorithms can look for and exploit observed patterns, correlations, and relationships among data elements and supply chain decisions – e.g., when to order a widget, how many widgets to order, where to put them, and so on. Such algorithms can be trained and tested using past data. They then can be implemented and evaluated for performance robustness based on actual realizations of customer demands. For example, does use of these data-driven tools lower cost and/or enhance customer service?

Why does this matter? The traditional paradigm for supply-chain management is to develop sophisticated tools to generate forecasts that accurately predict the value and the level of uncertainty of future demand. These forecasts are then used as an input to an optimization problem that evaluates trade-offs and respects constraints in order to come up with decisions about managing materials. This two-step process, which is embodied in all current material-management planning and control systems, can be replaced by a single-step process that looks for the best relationship among all of the data and the decisions. Based on learning from the past, a “best” relationship can be identified, which will generate decisions, as future uncertainty is resolved, that are better than the decisions derived from the traditional two-step approach of first forecast and then optimize.

This approach is not restricted by any a priori assumptions about the nature of the market and the behaviors that lead to customer demands or about the trade-0ffs and constraints that have to be considered in order to evaluate material-management decisions. Instead, the power of computer learning, supplemented by management input based on context-specific knowledge, is used to find the best relationship between all possible decisions and full range of the data. Use of this relationship can lead to better operational performance. It will lead to better outcomes because it utilizes all of the data available to current methods along with extensive additional data that currently is ignored and which may be relevant.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

This scenario becomes even more compelling when the impact of the internet of things is factored in. As they are used by customers, smart, connected products can generate orders of magnitude more data about current operating conditions and real-time performance of products. This data, along with traditional historical sales-based data, can support better methods for maintenance and the replacement of products.

The approach described here extends the concept of prescriptive analytics, which is considered by many to be the ultimate use of Big Data. Prescriptive analytics, however, has eluded most users of Big Data to date. There are some notable exceptions in industries such as online apparel retailing, where companies can view real-time, customer-purchase decisions (e.g., to buy or not to buy) and also can change the price of each product frequently at a negligible cost. The online retailer, however, knows little about the probability that consumers will purchase at each prices it sets but can learn dynamically about expected demand from sales data.

While many challenges remain, it is clear that a new approach that exploits all of the data that is becoming available is inevitable, given the connectivity, capacity, and transparency of data sources along with the vast computing power and data storage capacity available at a low cost. Like all planning systems, the proof will be in the results, when intelligent systems based on this approach are applied in practice. Change is coming to the world of inventory management and those that embrace this change will be ahead of the game. Successful adoption of this change will require active involvement of multiple functions within the firm along with a high level of coordination with both upstream and downstream supply chain partners as well as engagement with customers.

How Local Context Shapes Digital Business Abroad

One of the most enticing global entrepreneurial opportunities these days is taking a digital business model that works in the U.S. and transplanting it somewhere else, particularly in a developing country.

Several students in my Leading Global Ventures class at Harvard Business School have done just that over the past few years, and many more would like to follow suit. The appeal is easy to understand: You don’t have to invent a new business model, and the digital nature of these enterprises seems to promise a smooth transition to a new environment. There doesn’t appear to be any supply chain or heavy machinery to worry about.

But strangely enough, it’s often the nondigital components of a digital business that are most important for creating value in a new environment. It’s a hidden snag (or opportunity, as we will see) that many entrepreneurs don’t discover until they’re deeply into trying to port a business model to a new place.

What do I mean by nondigital components? Let’s consider first the example of Blink Booking, which Rebeca Minguela started in 2011 after graduating from HBS. Minguela had observed the rapid success of the U.S.-based Hotel Tonight, a last-minute online-booking service founded in 2010. She identified her home country of Spain as a great market to port the model to.

First, she had to persuade many hotels in Spain to sign up for the service, often by conducting individual sales calls. Second, she needed to convince local residents to sign up, usually through tailored advertising campaigns and direct appeals. Furthermore, Blink Booking had to make the app available in multiple languages to draw in a European market. In fact, at one point, most of Blink’s employees were translators.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

Doesn’t this list sound a bit odd? We began by talking about replicating a digital business concept across borders, but most of the tasks facing Minguela were very local in nature. Blink Booking’s experience is not an aberration. Instead, it highlights the important irony about business-model replication: Models that generate the most value through global replication are often the most localized. Consider the flip side of this: Google, an extremely profitable venture that is almost never replicated. Absent regulatory barriers, Google can so easily extend its search technology to new regions and countries that would-be rivals struggle to find an untapped location.

As a broader observation of this point, consider Rocket Internet. Rocket Internet’s core business model is replicating successful business ideas globally, matching the latest-and-greatest e-commerce ideas to the biggest untapped markets. In less than a decade, the Samwer brothers have built a multibillion-dollar empire (and earned the ire of many of the businesses they cloned). A close look reveals that the digital businesses copied by Rocket Internet over the years — Groupon, Amazon, eBay, eHarmony — stress local features. Rocket’s competitive advantage often centers on achieving operational excellence in difficult settings (for example, in Amazon clones, getting books to customers in countries with poor infrastructure).

So there are a few key points for entrepreneurs to consider in replicating digital businesses abroad:

Barriers to entry can work for you. A classic lesson from strategy is that value can come from entry barriers. It can be a big mistake to focus on settings where there do not appear to be any local barriers to entry. While a frictionless environment can make your own entry faster, it can also enable future competitors. Overcoming local challenges can create entry barriers against future competition and generate value for the venture. When Groupon acquired Blink Booking in 2013, it saw lots of value in the hotel clients and customers that Blink had established through painstaking door-to-door sales. In fact, some entrepreneurs end up selling their businesses back to the companies they copied when those companies begin international expansion (for example, Rocket Internet sold its European clone of Groupon, CityDeal, to Groupon itself).

Much of the replicated model will need to change. Transplanted businesses often end up looking very different once they are established. Another recent HBS graduate, Oliver Segovia, began his e-commerce company, AVA.ph, in the Philippines by replicating the concept behind the luxury flash-sales site Gilt Groupe. Yet Segovia quickly discovered that major changes were needed for an environment in which two-thirds of customers accessed the internet from public computers, one-third paid via cash on delivery, and the major business hurdles involved infrastructure and logistics. In fact, Segovia found as he tackled these problems that a much bigger opportunity for AVA lay in providing a general e-commerce platform for women’s fashion that incorporated many local designers and brands.

Closely study the type of network effects involved. Most digital businesses involve network effects, where the user value of being a part of the platform depends upon the participation of others. Some digital businesses benefit from local (often meaning city or regional) network effects (eHarmony, Groupon), while others have strongly global connections (Airbnb, Elance-oDesk). Still others can be in-between and evolving: Much of Uber’s network effects are regional, but international business travelers also value Uber’s presence in major overseas cities. Digital businesses with local network effects have often been the easiest to replicate in ways that create sustained value; with broader effects, entrepreneurs need to think carefully about future competition scenarios as the original business expands or others react.

There is a long history to replicating business ideas in new locations, and several aspects of globalization make today a particularly ripe environment. But aspiring entrepreneurs need to recognize that behind many apps lie complex nondigital business operations that are crucial to the process of creating value.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers