Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1282

June 19, 2015

A Guide to Winning Support for Your New Idea or Project

You’ve got an idea for something that will improve your company’s bottom line or make it a better place to work. Nice going. Now for the hard part: How do you get people on board? How do you get funding? And what should you do if your idea doesn’t catch on?

What the Experts Say

In an ideal world, you’d come up with a genius new idea, tell your coworkers about it, and they’d immediately grasp its brilliance. Your boss would love it — and you! — and give you the resources you need to execute it. But that’s not reality. “It’s very hard to start a new initiative,” says John Butman, author of Breaking Out: How to Build Influence in a World of Competing Ideas. “It’s hard to get people to listen to your idea, to understand your idea, and to take action.” It may be difficult, but it’s also a vital skill to master. “Organizations need to keep changing, adapting, and innovating,” he says. “If they don’t, they stagnate and disappear.” But it’s not only the success of your company that’s at stake, says Susan Ashford, professor of management and organization at Michigan’s Ross School of Business. The ability to get new initiatives off the ground is also critical to your career. “You want to stand out, be visible, and get noticed as a leader,” she says. “And one of the ways to do this is by suggesting change ideas and implementing them.” Here are some pointers on how to get your idea moving.

Understand what’s motivating you

Before you breathe a word about your idea to a colleague, you must “think through your motives,” advises Butman. Ask yourself two questions: Why am I doing this? And what do I hope to accomplish? “You need to be able to express your motives” in a way that’s relatable and compelling to others, says Butman. “If the initiative seems like something that will only make you more successful, give you more exposure, or help you get a better job,” people will be skeptical. “It needs to benefit more than just you. Otherwise you’re going to run into trouble.”

Think small

Next, you need to pinpoint “your idea by making it as specific and small as it can possibly be,” Butman says. Pick precisely where you want to focus. If your new initiative involves, say, improving employee health, zero in on a particular goal, such as decreasing employees’ back pain or helping workers quit smoking. This exercise helps you “articulate the issue” you’re trying to address, and explain why your initiative “offers a possible solution,” says Ashford. Your colleagues are more likely to respond to specific initiatives rather than lofty, ambiguous goals.

Gather feedback

Test the waters for your idea by making frequent use of what Butman refers to as “the cocktail party test.” When you find yourself with colleagues who might be interested in your initiative — whether they are close coworkers or people from an entirely different department or division — broach your idea in an informal way. “Present your idea by saying something like, ‘I’ve been thinking about this,’ or ‘What would you think of this,’” suggests Butman. Then, listen carefully to what people tell you. “You want questions. You want opposing viewpoints. You want pushback,” he says. The goal is to get to a place that no matter what anybody throws at you, you have a response. “Be sure to integrate their feedback into your game plan,” adds Ashford. “It’s a process of iteration and figuring out” what works.

Shape your story for the audience

Strategize how you’ll sell your initiative to different groups of colleagues and higher-ups. “Think about the language you’ll use for each of your audiences,” says Ashford. “You need to be seen as credible” when you’re talking about the financial implications of your initiative to the finance group, for instance. “You need to be able to talk about your idea succinctly and vividly and in a solutions-oriented way,” she adds. After all, “if you’re in an elevator with a decision-maker, you have only so much time to talk and you can’t very well shoot your PowerPoint slides up on the walls.” And bear in mind that “everyone has different learning styles,” says Butman. “You can’t expect to write a white paper and slap it on people’s desks.” For this reason, it’s important to vary your messaging with “something written, something spoken, something visual, and perhaps even tangible.” Butman recommends using a personal story to provide context. “Give people some idea of how you came up with the idea and why it’s meaningful to you as a human being.” Ashford concurs. Your presentation and pitch “should not be just a bunch of charts and graphs; it should have visual appeal,” she says.

Sell, sell, sell

Selling your idea is “not a singular event — it’s a campaign,” according to Ashford. “You need to do a lot of water cooler talk with different kinds of people.” Getting people to nod their heads in agreement is the first step, but to spark excitement and secure funding you need to inspire. “You want to trigger people’s emotions as well as their rational selves,” she says. Your aim is to “reduce resistance, bring people on board, and band allies and resources together.” You should be “closing the deal all the time,” adds Butman. “When you talk about it, you want people getting a little bit more of the idea and signing on to it a little bit more each time.” The goal, he says, is “internal virality” through “incremental agreement.” One word to the wise: When you’re trying to get others on board, don’t use the word new. “That’s the language of marketing,” says Butman. Colleagues need to be able to understand your idea in the context of the company’s past measures. “People often think their initiative has to be newer than new, but really it should be between 80-90% old — not radically new, but incrementally so.”

Propose a pilot

Ashford suggests proposing a trial run. It could be in the spirit of, “Let’s not worry about making this change wholesale — let’s try a pilot,” she says. “It reduces the perceived risk” of implementing something big and new. Pilots “give people a chance to test out” the idea. “And they can also create data that changes minds.” If you don’t have the power to allocate budget to a pilot, you need to sell harder to those who do. “Organizations have limited time, attention, and money,” says Ashford. Don’t lose sight of the fact that you’re constantly “competing against other people’s ideas” and other people’s doggedness. “If you and your allies really care about something, you need to sell it”; a pilot is often a cost effective way to do it.

Don’t get discouraged

Even when it seems you’re constantly running into roadblocks and your initiative may never get off the ground, don’t be deterred. “Sometimes an idea catches on right away, and sometimes it takes decades for it take hold,” says Butman. Persistence is key. But this does not mean persistence at all costs. Make sure you’re incorporating people’s feedback — both the good ideas and the potential sticking points — to your pitch. “Give up your desire for credit and control, and let people help you,” says Butman. It all gets back to your motives, says Ashford. “You need to care about the idea, not getting credit for the idea,” she says. “Think about what’s good for all not just what will let you shine. Trust the universe,” that you will get credit when it’s due.

Principles to Remember

Do

Make your idea as specific as possible and emphasize how it offers a clear solution to a targeted problem

Adapt your sales pitch to the audience

Suggest a pilot of your plan — trials are less risky and less expensive

Don’t

Insist on getting credit for the initiative — colleagues are less likely to support your idea if they sense you’re only in it for yourself

Forget to solicit feedback from your colleagues

Give up if your idea doesn’t immediately gain traction — change sometimes takes longer than you’d like

Case Study #1: Gather feedback and, if necessary, adjust your message

Beth Monaghan, the principal and co-founder of Ink House, the PR firm, knew that she needed to take drastic action after she heard about the behavior of some of her young workers. “I started hearing stories about employees competing with each other to work late into the night, to only eat lunch at their desks, and to check emails at all hours,” she says. “I realized that the problem of balance was becoming pronounced.”

After talking with her management team, Beth decided to announce two new initiatives at a staff meeting earlier this year: a company-wide no email rule between the hours of 7pm and 7am, and an unlimited vacation policy. She wanted to “set the expectation that employees should have a personal life.”

Employees were excited about the no email policy — in emergencies, they were allowed to call each other — but the unlimited vacation idea was a different story. “I was expecting cheers. I didn’t get that per se,” she says.

In order to get employees on board, she needed to sell the idea — but first, Beth needed to understand the source of people’s resistance. She “informally solicited feedback from employees in a ‘Hey, what did you think of that?’ way.” It turned out that some senior workers felt they deserved more vacation time than junior members of the team; others worried about employees that might take advantage of the rule.

Listening to those concerns caused Beth to adjust her message and her delivery. Beth had multiple conversations with employees where her goal was to “shift the way people thought about the time they spent at work.” She also had a large wall decal made that summarized the company’s values. The wall reads, among other things, “We don’t confuse process with progress.” And she held a staff meeting to assuage concerns about potential violations. “I said, ‘We hired smart, responsible people, and we trust you to use good judgment. If a certain employee takes advantage, we’ll deal with it.’”

For the most part, the policy has been a success. Beth admits she occasionally violates the no email rule. “I really try not to, though. It’s a good forcing function for me to get my work done during the day.”

Case Study #2: Use a relatable story to sell your idea; be patient with implementation

Julie Wittes Schlack, SVP of Innovation and Design at C Space, the global consulting company, knew that her company needed to streamline its client services, but she wasn’t sure how to get the idea off the ground. “We had all these codified processes that we were doing just because that’s the way we had always worked,” she says.

Then, one day, when Julie and C Space’s management team were at the company’s annual off-site retreat, they had a moment of clarity. During one of the sessions, they read a case study about a hotel chain that trimmed labor and production costs by ceasing to launder guest sheets every day. It was a story that Julie and her team immediately related to.

“It was the first hotel chain to ask, is [every day] linen changing necessary?” says Julie. “Linen changing became a great metaphor for our own cumbersome and obsolete processes.”

When Julie and the other senior leaders returned to the office, they worked to get other employees on board with the initiative to restructure client services — which accounted for three-fourths of the organization. They began by sharing the hotel story in meetings and in casual conversation. “People internalized the idea,” says Julie, adding that from then on employees used “Are we just linen changing?” to refer to processes that were not critical to the organization. “It was a shorthand and an easy way for people to talk about [the restructuring] as they were going about their daily tasks. Is this [process] necessary? Is this desirable?”

They had buy-in from employees, but when it came to implementing the initiative and eliminating certain processes, Julie received some pushback. To deal with it, Julie diagrammed the current system to show how many different people and departments were involved in each process. “It became easier for others to see where there was overhead and get aligned on [where we could cut back],” she says.

Restructuring client services was a six-month process, but ultimately her employees embraced the initiative because it saved them time and it saved the company money. “They saw what was necessary and what was adding value,” she says.

June 18, 2015

Dear Boss: Your Team Wants You to Go on Vacation

Over the past decade, a staggering number of studies have demonstrated that our work performance plummets when we work prolonged periods without a break. We know that overworked employees are prone to mood swings, impulsive decision-making, and poor concentration. They’re more likely to lash out at perceived slights and struggle to empathize with colleagues. Worse still, they are prone to negativity — and that negativity is contagious.

Yet at the average American company, 4 out of 10 employees (including those in management roles) will forfeit vacation time this year.

There is every reason to believe that the cost of the mental and physical depletion that invariably results is exponential when its victim is a manager. Not just because a supervisor’s mood and decision-making affects more people, but because when a manager chooses to forgo time off, it starts a domino effect that shapes cultural norms.

As I describe in a new book on the science of building a great workplace, organizational culture has little to do with a company’s mission or vision statement. It is determined by the behaviors of those at the top. As humans, we’ve evolved to mimic those around us, especially those in higher status roles. Lower-status group members often copy the behaviors of those in leadership positions because it helps align them with individuals who hold more influence in the group. The best managers know that as leaders, their actions influence the behaviors of everyone around them.

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Managing Yourself

Managing Yourself Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When managers forgo vacation time, it not only places them squarely on the road to burnout, it also generates unspoken pressures for everyone on their team to do the same. And ignoring the body’s need for rest is not just a poor long-term strategy. It also comes with considerable opportunity cost.

We now have compelling evidence that the restorative experiences we have on vacations bring us a sharpened attention, mental clarity, and inspired insights. Take reaction time – a simple measure that indicates how quickly we pick up on new information. Research commissioned by NASA found that after just a few days of vacation, people’s reaction time jumps by an astonishing 80%.

Studies on creativity have found that spending time outdoors and traveling to a foreign country — two activities people commonly engage in when they go on vacation — are among the most effective ways of finding fresh perspectives and creative solutions. Simply put, you’re far more likely to have a breakthrough idea while lounging on a beach in St. Martin than you are while typing away in your office cubicle.

Vacations are not only a boon to the way we think; they also foster greater life satisfaction. Just last year, Gallup released an eye-opening study showing that how often you vacation is a better predicator of your well-being than the amount of money you earn. In fact, according to Gallup’s data, a regular vacationer earning $24,000 a year is generally happier than an infrequent vacationer earning 5 times as much.

And that elevated well-being affects more than just people’s moods. It also influences the way they think about their jobs. According to a Nielsen poll, more than 70% of regular vacationers are satisfied with their job. But those who don’t vacation? A measly 46% are satisfied.

Just why do vacations affect us so strongly? In part, it’s because they allow us to disengage from the stress of work and replenish our mental and physical energy. But psychologists believe there’s more to the story than just recovery. Vacations provide us with an opportunity to engage in autonomous experiences and allow us uninterrupted time with loved ones and close friends. They also enable us to build our competence in hobbies we cherish. In others words, a good vacation grants us what we desperately seek in our work — energizing experiences that fulfill our basic, human psychological needs.

Given all the benefits of vacations, perhaps it’s time we considered treating unused vacation days as a valuable metric — one that reflects the inverse of a healthy workplace culture; an indication that a company is suffering from energy mismanagement.

So how do we reverse the trend of unused vacation time? How do we get more people feeling good about taking vacations when clearly, their company benefits from them taking a break? Encouraging managers to model the right behaviors and educating employees about the benefits of time off is a good start, but it’s unlikely to be enough — not when recent economic struggles have trained so many workers to avoid appearing replaceable, even if it’s for just a few days.

For those who are genuinely serious about getting employees to vacation, a more promising approach involves offering a monetary incentive that rewards taking time off. It’s a tactic that’s slowly gaining traction among a growing number of companies. The RAND Corporation, for example, no longer pays employees their regular salary while they’re on vacation. Instead, they pay time and a half. The US Travel Association has set up an internal raffle worth $500. To be eligible, employees have to do one thing: Use up all of the previous year’s vacation days.

Then there’s the Rolls Royce of pro-vacation policies, furnished by FullContact. The Denver software company has implemented a program that actually pays employees $7,500 to take their family on vacation. The only stipulation is that they not do any work during their time off. If you’re on a FullContact-sponsored getaway and you’re caught opening a single work email, you’re obligated to return every penny. (As a result, job application numbers at FullContact are up, and turnover has dropped.)

What makes these policies notable is not their generosity. It’s that they provide clear evidence that a company is serious about encouraging employees to restock their mental energy so that they can continue to excel.

We live in an age when vacations and the restorative experiences they provide are no longer a luxury. They are essential to our engagement, performance, and creativity.

Why Startups Are More Successful than Ever at Unbundling Incumbents

Scale isn’t what it used to be. It’s never been easier to start a company, and as a result new entrants are unbundling incumbents’ businesses and chipping away at their advantage. Upstarts like The Honest Company, Warby Parker, and Airbnb are able to quickly win market share from leading businesses like Procter and Gamble, Luxotica, and Starwood Hotels by decomposing markets into highly customized niches so that the incumbents can’t compete on scale alone. And by now it’s clear that these companies are well positioned to achieve greater success than originally envisioned, and may displace many of the Fortune 500 brands over the next decade or two.

It’s also clear that this is an economy-wide phenomenon. The playing field is being leveled across a variety of industries: Tesla is a leading high-end automaker, SolarCity is taking share from electric utilities, Uber is reorganizing the taxi industry on its platform, and companies like Blue Apron and Casper are chipping away at various retail segments. There are companies attempting to redefine customer experiences in almost every industry including education, healthcare, and financial services.

There are two core drivers of this economy-wide unbundling.

First, these companies are essentially product design teams that are focused on iterating fast to find product-market fit. They are able to offer fundamentally better products and services than the incumbents because of the product-centric DNA of the management teams. They usually focus their product development on a sub-segment of the millennial demographic because millennial customers don’t have much loyalty to existing brands. Whether it’s consumer packaged goods or financial services, these customers are willing to try new brands and share their experiences openly with each other through rankings and reviews. As a result, momentum builds fast behind companies whose products and services are truly better in the consumers’ minds.

Second, these companies rent all aspects of operational scale from partners and eliminate any capital expenditures or operational inertia from their execution plans. They are therefore designed for growth, especially given their lean organizational structures. For manufacturing, logistics, customer acquisition, and commerce, there are third party services and APIs available to scale with customer demand as quickly as necessary. Once these companies have built a relationship with their customers, they quickly go on to re-bundle products and services to increase their share of the customer’s wallet.

As an example, The Honest Company has emerged in recent years as a new type of consumer goods company, focused on quality and sustainability. (Disclosure: my firm is an investor.) The company started by selling diapers that replaced petroleum-based ingredients with organic materials. Once it had built a relationship with the “millennial moms” as a safe and high-quality brand, it went on to bundle other household products in its offering. Today, the company looks like a fast-growing, early version of the next Procter and Gamble.

Lending Club is another example of a company that is taking share from incumbents in a massive category. It started in 2008 as one of the first applications on Facebook’s platform and allowed consumers to lend to other consumers. It offered a new type of investment opportunity, rather than the traditional option of investing money through banks. It can cost-effectively market to consumers on social platforms like Facebook, and it leverages cloud services to enable the lending workflow, movement of money, and management of risk. The company had originated over $7.5 billion in loans by 2014 and has become one of the largest financial institutions in just a few years.

This is a structural change. Today’s innovative companies also run the risk of being disrupted by a new generation of nimble upstarts that will use the very same unbundled business model to their advantage. Businesses will need to persistently focus on product and customer success, because for most firms scale isn’t a moat any more. (The monopolistic advantages of scale are shifting to platform companies like Amazon, Facebook, Apple Pay and YouTube. These platform companies are becoming essential to how the economy functions, as power companies and internet service providers have been for decades.)

The implications of this structural shift are quite profound.

For example, until now, policies designed to protect labor, consumers, and trade practices were set by law. Now these platforms make many of those decisions based on machine learning algorithms with the objective of maximizing profits. These platforms need to embrace a new level of algorithmic accountability as they become the utilities of the new economy.

These same platforms have also started to enable workers to make the profound shift from a being an “employee” to managing a “personal enterprise” which extends its services to various sharing economy platforms. All the labor protections that have been in place for decades need to be reimagined. (I will explore these topics in later posts.)

Still, the lessons for businesses are relatively simple. For incumbents: you can’t count on scale like you used to. For entrepreneurs: rent scale where you can, and focus on product design above all else.

Firms Need a Blueprint for Building Their IT Systems

Winchester House in San Jose, California, was once the residence of Sarah Winchester, the widow of gun magnate William Winchester. This mansion is renowned for its size, its architectural curiosities, and its lack of any master building plan. It is, unfortunately, also a great analogy for how many organizations have constructed their IT systems.

Mrs. Winchester began building her mansion in 1884 and its construction proceeded without interruption until her death in 1922. Workers labored on the house day and night until it became a seven-story mansion with 160 rooms, including 40 bedrooms, 47 fireplaces, 17 chimneys, and over 10,000 panes of glass.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

Mrs. Winchester did not use an architect, and all of the work was done in a haphazard fashion. The house contains numerous oddities like doors that go nowhere and windows overlooking other rooms. One window was designed by the famed Tiffany & Company so that when sunlight strikes it, a rainbow is cast across the room. The only problem is the window was installed on an interior wall in a room with no light exposure.

Many organizations are in a similar situation. Their structure emerged and continues to evolve without any blueprint or architectural integrity. Processes are bolted on in response to new products and services. Systems are implemented to support local initiatives. Policies to aid efficiency are ignored. IT applications to support local or functional strategies and initiatives are provisioned directly from the cloud, often without the knowledge of the IT department. The result is different data definitions, inconsistent business logics, multiple workarounds, unrealized synergies, redundancy, re-invention rather than re-use, and a myriad of different technologies.

Given how the importance and complexity of IT are rapidly increasing thanks to a variety of advances (e.g., analytics, sensors, the internet of things, social media, mobile computing and apps, 3-D printing, and the cloud), the lack of a plan is dangerous. It is imperative for firms to have a blueprint for how information will be used to help the business create and capture value, how different kinds of information will be integrated, and the extent to which organizational processes will be standardized (the more such processes are standardized, the more the IT systems supporting them can be standardized). At a time when the customer end of the business model seems to be getting all the attention, executives must not neglect the equally important operations back end.

IT systems “hardwire” an organization’s processes, practices, and information flows, ultimately determining what it can and cannot do. Indeed, any IT outsourcing contracts will be based on a particular way of running the business, locking these in for many years. This will inevitably have a significant impact on operations. Technologies such as “middleware” can provide short-term relief, but it is usually only papering over the proverbial cracks, adding to the problems that will inevitably be encountered in the future.

Without any integrity or coherence in the business operating model, the inevitable result is complexity and the inability to respond to changing competitive conditions and to embrace new digital opportunities because of the legacy of past decisions and indecisions. In response, many now seek agility yet simultaneously fail to address the issue of complexity and exorcise the spirits of legacy. Agility cannot be achieved without first tackling complexity.

But it need not be like this.

The discipline of enterprise architecture (EA)—creating and adhering to an overarching plan for building IT systems—has been around for some time. However, because of the reluctance of business managers to engage in this process of design, it is more often undertaken by IT professionals themselves, who end up guessing what the business will require.

In constructing any building, there are multiple perspectives to consider: the owner’s, the planning authorities’, the building contractor’s, the carpenter’s, the bricklayer’s, the glazier’s, the plumber’s, etc. All are interested in their view of what is being designed and built but need to work from a common vision if coherence is to be achieved. The same is true of IT. The key choices are around the degree of standardization, the extent of information integration, and how information will be used to support strategic and operational decisions. These choices will have significant impact on performance.

To make these choices, five things are required:

1. The leaders of the business must take responsibility for the design of the operating model that frames the EA from a process, people, data, and things point of view. This involves an integrated view of how value is created through products, services, and solutions and is then captured in the design of the operating model. Many executives focus on capturing value before they have figured out how to create it. As incumbent businesses are increasingly threatened by digitally oriented disruptors, the operating model is as important as the innovative design of the business model.

2. Enterprise leadership—a view of the business beyond optimizing functional silos between business functions and across support functions—is a must. Too many executives are still measured and rewarded for functional leadership and not for an integrated view of how strategy, structure, processes, culture, rewards, and information flows define how a business operates and continuously changes. Again, disruptive entrepreneurs in many established industries focus holistically on the operating model, while consciously abandoning established functionally-oriented ways of thinking and leading.

3. Firms must abandon the dominant IT paradigm of the IT department deploying systems within requirements, on time, and on budget, and then declaring “mission accomplished” once the system has gone live. To gain agility, the company leaders must adopt a usage-oriented view of turning data into useful information, designing software as usable applications, and leveraging technology and infrastructure from whatever combination of partners and suppliers can deliver desired functionality. Clearly, the consumer world of apps and usability is driving a usage-oriented paradigm into the corporation that is challenging the established IT view of the company dominated by big systems, big projects, and “deploy and go live” mind-sets, behaviors, and measures of IT functional success.

4. The enterprise architecture must be driven by a customer- and market-oriented view of a constantly changing business environment. If executives believe that their industry and business climate is driven by volatility, uncertainty, constant change, and ambiguity (VUCA), then their views of the business model and underlying operating model must be designed and built with simplification, flexibility, agility, and mass customization in mind. Despite the declining life cycles of companies in most industries, the IT view of EA is still dominated by views of stability, complexity, and standardization that are out of step with both the actual VUCA environment and the continuous forces for digital disruptions coming from the world of analytics, mobile, platforms, and social media.

5. Business and IT leaders must take a long-term view of how to design and build modularity into the databases, systems, and the processes that they support. When you cannot predict what data, systems, and technologies you will use in 5, 10, or 15 years, then you must view the operating model with an eye toward “flexible stability” where you design and execute with constant change in life cycles of processes, databases, systems, and technology in mind. Business and IT leaders must apply a “design for use” approach to their views of enterprise architecture rather than a “design to build” approach where stability, compliance and risk are the dominant views of EA.

Mrs. Winchester could afford to build a house with no real design and architectural concept in mind except her daily tastes. Business leaders cannot afford similar chaos within their organizations and an IT-dominated view of EA. Neither is acceptable in a world dominated by digital innovation, change, and disruption.

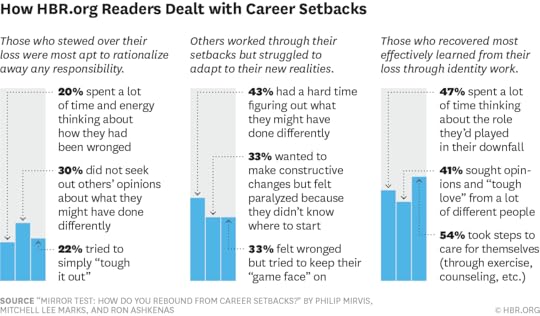

The 3 Ways People React to Career Disasters

It’s not how hard you fall, but how you pick yourself up that really matters. That is what we learned from 9000+ responses to our HBR survey on bouncing back from career setbacks. Resilience alone won’t cut it—you need to do some serious self-reflection.

We worked with Douglas (Tim) Hall, a leading expert on careers, and his doctoral student Lan Wang of Boston University’s School of Management to analyze the data about how managers said they recovered. Three overall patterns emerged. Some stewed over their loss and got stuck in a cycle of self-justification. Others tried to work through their setbacks but struggled to adapt to their new realities. But nearly half of respondents focused on learning from their loss through “identity work”—they thought about the role they played, sought opinions from different people, and took steps to care for themselves. They were the ones able to move forward most effectively.

The idea that you have to “work through” your feelings after a setback might seem self-indulgent to some but it may be the most productive route forward. No matter what their initial reactions, those who took a hard look at themselves, and spent time considering their careers and interests, were least likely to lurch into an aggressive job search and most likely to say, in the end, that their career loss was a good thing.

Hall has identified two competencies as crucial in successfully navigating today’s careers: personal adaptability and identity development. According to Hall, personal adaptability hinges on the “predisposition to scan and read external signals consciously and continuously.” Here we found that those managers who tried to understand the situation from all vantages and sought opinions from lots of different people were most apt to realize “I might have prevented what happened if I’d done certain things differently.”

However adaptability alone is not sufficient for moving forward smartly in your career. Hall writes that identity development that focuses on “a person’s ‘self-system,’ representing the person’s image of herself or himself in relation to the environment,” is also needed. Some executives fear that identity work leads to self-doubt and paralysis, especially when the situation calls for action. But the survey results provide an apt counterpoint.

Those who leapt into an aggressive job search absent of self-reflection were far more likely than other managers to keep operating as usual—and to have concluded that their career loss was “one of the worst things that ever happened to me.” Those who turned to identity work, by comparison, were more likely to experiment with new ways of working and also focused on “finding a good fit.” They were most likely to say that their loss was one of the best things to happen to them.

What the survey results show is that both adaptability and identity work are necessary in order to learn from and move forward after a career setback. In other words, winning at losing means not just traversing the stages of anger and grief, but also being open to the possibility of emerging from the twilight zone with a new sense of self that can guide how you respond to changing organizational realities. On this point, Hall believes that managers today need a more “protean” approach to career development. Like the Greek god Proteus, they must be able to change their shape to adapt to new situations. And as people move through successive stages of their careers, and their experience pool becomes richer and more complex, their sense of self must also grow—and this demands regular self-reflection to maintain an integrated personal identity.

From our experience, the formula for winning at losing is to become untethered from past success and to explore broader definitions of what it means to win both personally and professionally. This gives you a better chance to find self-expression and meaning at work, and while your next position may not be perfect, you’ll have a better sense of self, clearer intent, a plan of action for going forward, and experience you can draw on when you need it.

Case Study: Can Retailers Win Back Shoppers Who Browse then Buy Online?

Kenneth Andersson

Bertice Jenson couldn’t believe how shameless they were. Right in front of her in the Benjy’s superstore in Oklahoma City, a young couple pointed a smartphone at a Samsung 50-inch Ultra HD TV and then used an app to find an online price for it. They did the same for a Sony and an LG LED model, as the Munchkins from The Wizard of Oz danced across all three screens.

“Excuse me,” Bertice said. “I see what you’re doing. Don’t you think that’s kind of … unfair?”

The two shoppers looked at each other as though this hadn’t occurred to them. “We’re only comparing prices,” the young woman said, stroking the West Highland terrier nestled in the crook of her arm.

“But the app—it’s Amazon’s, right?” Bertice asked. “Once you figure out which TV you want to buy, you’re going to order it from Amazon.”

“Probably,” the young man said, shrugging.

“But Amazon … ” Bertice couldn’t articulate what she wanted to say. “See, Amazon … What I mean is, this isn’t Amazon’s showroom. Benjy’s doesn’t display these products and staff these stores for the benefit of Amazon. We want you to buy from us.”

They looked at her blankly. “Oh, you work here?” the woman asked.

Editor’s note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Bertice wasn’t dressed like the sales staff, and the couple had no way of knowing that she was the daughter of Benjy’s founder or that she’d been recently appointed to chair the board of the $40 billion electronics and appliance retailer. She was now making a routine drop-in visit to one of the chain’s 2,000-some stores. But that wasn’t worth explaining.

“Never mind,” Bertice said. “Just be aware that what you do has consequences. This real-live shopping experience you’re having here at Benjy’s is helping you decide which TV to buy. And if you order from Amazon, you’re basically stealing that experience and cheating us.”

She knew she sounded shrill. The couple looked as though they expected her next words to be, “I’ll get you, my pretties, and your little dog too!”

Caught in the Middle

Bertice wasn’t accustomed to playing the Wicked Witch. Although she prided herself on her financial toughness, she was a natural mediator. Her father, one of America’s most prominent African-American corporate leaders, had always counseled her to be even-tempered and even-handed, and she had been—through four years at a mostly white high school, six years in mostly male undergrad finance and MBA programs, the 15 years she’d spent working her way up the ladder at a top-tier accounting firm, and especially the decade she’d been on the board of Benjy’s.

Bertice was now preparing to mediate between her father and the company’s CEO, who had very different ideas about how to respond to what Bertice had seen in Oklahoma City: “showrooming.” Customers like the couple with the Westie weren’t unusual. More and more people were coming to Benjy’s to look at products but then buying them from online competitors whose lack of a bricks-and-mortar presence enabled them to offer discount prices. Research showed that 83% of people shopping for electronics and appliances were now practicing showrooming. The chain’s sales had nosedived as a result; the most recent quarterly loss was nearly $700 million.

“Baby, baby, baby,” Ben said as he hugged his daughter in the 16th floor hallway.

“I’m 41 years old, Daddy,” she chided him playfully.

“I didn’t hear that,” said a voice behind her. It was Stanley, or “Farb,” as everyone called him. Smiling, he shook hands with both Ben and Bertice.

“Why don’t we move into the boardroom?” Bertice said. “I think everyone else is here.”

After the usual pleasantries, Bertice jumped right in: “Showrooming is a serious problem for most retailers, but particularly those of us in electronics. Amazon keeps making it easier for shoppers to search, find, and order a product online. We need to decide on a counterstrategy. Farb, I know you’ve prepared a presentation for us.”

The projector was balky, and Ben took advantage of the pause to put his own views out there. “I think it’s obvious that we need to play both offense and defense. Offense should include providing more-aggressive discounts through the Benjy’s app and matching online prices. We also need to get more suppliers to impose minimum advertised prices on their online retailers, so that there’s a floor price for every product, online or off. We’re already working on that.

There was murmuring around the table. Apparently this was news to some of the directors.

“But there are ways to thwart object-recognition software,” Ben continued. “We create display structures within the stores that confuse the apps while still showing off the products. There are consulting firms that specialize in this. The costs are relatively minor and well worth it. Personally, I think this tactic is a no-brainer.”

“Bertice,” the CEO said.

She realized that she was letting her father dominate the conversation. She asked Ben to hold off, now that the projector was working, and she gave Farb the floor.

“The way they shop is killing us,” Ben interjected.

Ben sputtered: “We’re not running cafés, Farb!”

Farb gave her a grateful look. “TVs and laptops may seem like commodities that people want to buy only at the lowest possible prices, but so did coffee before Howard Schultz made Starbucks a destination. Why shouldn’t Benjy’s do the same—showcase only the highest-value products and educate customers about them, instead of letting them flounder in an overwhelming, uncurated retail landscape?”

“You’re sounding naïve, Farb,” Ben said. “People will still showroom if they find better deals online.”

“We could still match prices,” the CEO said.

“How could we afford that?” Bertice asked, keen to break up the back-and-forth between the two men.

“There’s no precedent for that in electronics retail,” Ben countered. “It’s a nonstarter. You’ll ruin relationships that we’ve spent decades building. And you’re talking about huge business-model changes that, even if we wanted to make them, would take months—maybe years!—to implement. We need a solution now!”

Several board members nodded in agreement. Bertice could sense that Farb was ready to respond and that her father was up for a fight, but she knew it wouldn’t be a productive one. “Farb, you’re proposing a pretty radical change and it’s a lot for us to digest,” she said quickly. “Dad, it would also be useful to have more detail on those countermeasures you mentioned. So let’s table this discussion for now and get through the other items on our agenda. Farb can send around his deck, with plenty of supporting data, and we can all take some time to review the information. If everyone is amenable, I’d like to arrange a conference call next week to discuss only this and decide on a course of action.”

New Ways to Make Money

The next day, Bertice was in Huntsville, Alabama, to join in the ribbon cutting for a redevelopment project. Several big-box superstores—including a Benjy’s—had been closed and replaced by a mixed-use residential-retail community. Benjy’s still had a presence but a much smaller one.

“Welcome to Benjy’s,” a store employee said when she walked in. “Did you come here today looking for something specific?”

So customers weren’t responding to price-matching, and they were being chased away by excellent service. All this put her in mind of Oz again. This time she didn’t feel like the Wicked Witch; she felt like Dorothy, uprooted by a whirlwind and thrown into a world that made little sense. But no ruby slippers were going to help her get back to the old predictability of retail. She would have to figure out herself how to move forward.

Question: Should Benjy’s fight the showroomers or welcome them?

What Private Equity Investors Think They Do for the Companies They Buy

The private equity industry has grown markedly in the last 20 years and we know more than we used to about its effects on the economy. We also know that private equity funds have outperformed public equity markets over the last three decades, even after the fees they charge are accounted for. What have been less explored are the specific actions taken by private equity (PE) fund managers. PE firms typically buy controlling shares of private or public firms, often funded by debt, with the hope of later taking them public or selling them to another company in order to turn a profit. But how do PE firms decide which companies to buy? And what do they do once they buy them?

Our research seeks to fill that gap. In a survey of 79 PE firms managing more than $750 billion in capital, we provide granular information on PE managers’ practices and how firms’ strategies relate to the characteristics of their founders. In particular, we are interested in how many of their responses correlate with what academic finance knows and what it teaches. Do PE investors do what the academy says are “best practices?”

PE firms typically take three types of value increasing actions — financial engineering, governance engineering, and operational engineering. These value-increasing actions are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but it is likely that certain firms emphasize some of the actions more than others. (We classify private equity as buyout or growth equity investments in mature companies. Private equity as we define it in this paper does not include venture capital investments.)

In financial engineering, PE investors provide strong equity incentives to the management teams of their portfolio companies. At the same time, debt puts pressure on managers not to waste money. In governance engineering, PE investors control the boards of their portfolio companies and are more actively involved in governance than public company directors and public shareholders. In operational engineering, PE firms develop industry and operating expertise that they bring to bear to add value to their portfolio companies.

Despite the growth in private equity, only a few research papers have studied the actions PE investors actually take. In particular, no paper examines detailed levers of value creation across financial, governance, and operational engineering. By reporting the results of a survey of private equity investing practices, our sample represents PE firms across a spectrum of investment strategies, size, industry specialization, and geographic focus. We ask the PE investors questions about financial engineering — how they value companies, think about portfolio company capital structures, and management incentives; governance engineering — how they think about governance and monitoring; and operational engineering — how they think about value creation, both before closing the transaction and after the transaction. We also ask questions about the organization of the private equity firms themselves.

How PE firms decide to invest

Our research shows that private equity investors don’t seem to rely on the financial tools taught at business schools. For instance, despite the prominent role that discounted cash flow valuation methods play in academic finance courses, few PE investors use discounted cash flow or net present value techniques to evaluate investments. Rather, they rely on internal rates of return and multiples of invested capital. Furthermore, few PE investors explicitly use the capital asset price model (CAPM) to determine a cost of capital. Instead, PE investors typically target a 22% internal rate of return on their investments on average (with the vast majority of target rates of return between 20 and 25%), a return that appears to be above a CAPM-based rate.

Our analysis of how private equity firms calculate hurdle rates – the minimum acceptable rate of return on an investment — also indicates also indicates a deviation from what is typically recommended in finance research and teaching. Another indication that PE investors are skeptical of CAPM-based methods for valuing companies is the fact that they rely on exit multiples as a shorthand for evaluating their investments. (If a similar company is valued at, say, 1o times its earnings, take the earnings of the company you’ve invested in, multiply it by 10, and you have a rough valuation.)

We also asked the PE investors how the funds that provide them with capital — limited partners (LPs) — evaluate their performance. Surprisingly, the PE investors believe that their LPs are most focused on absolute performance rather than relative or risk-adjusted performance. This is also puzzling given that private equity investments are equity investments, some of which had been publicly-traded prior to a leveraged buyout. Such investments carry significant equity risk, suggesting that equity-based benchmarks like public market equivalents (PMEs) are appropriate.

Our results on capital structure are more consistent with academic theory and teaching. In choosing the capital structures for their portfolio companies, PE investors appear to rely equally on factors that are consistent with capital structure trade-off theories (i.e., trading off the benefits of debt, namely tax shield and disciplining management, versus the costs of debt, the higher likelihood of financial distress) and those that are consistent with market timing (i.e., the notion that debt financing can be “cheap” at certain times). These results are somewhat different from those for large companies in which CFOs focus on financial flexibility.

What PE firms do after they invest

What about once PE firms make an investment? Here we find evidence of both financial and governance engineering. PE investors say they provide strong equity incentives to their management teams and believe those incentives are very important. They regularly replace top management, both before and after they invest. And they structure smaller boards of directors with a mix of insiders, PE investors, and outsiders. These results are consistent with research on value-enhancing governance structures that have been identified in other settings.

Finally, PE investors say they place a heavy emphasis on adding value to their portfolio companies, both before and after they invest. The sources of that added value, in order of importance, are increasing revenue, improving incentives and governance, facilitating a high-value exit or sale, making additional acquisitions, replacing management and reducing costs. On average, they commit meaningful resources to add value, although there is a great deal of variation in how they do so.

Not all PE firms use the same strategy

We take the responses to the various questions about individual decisions and analyze how various decisions are “related” to each other by employing cluster analysis and factor analysis. Essentially, we use cluster analysis to explore whether private equity firms follow particular strategies. We find that the answers to our survey cluster into categories that are related to financial engineering, governance engineering, and operational engineering.

Both the cluster analysis and the factor analysis appear to divide firms into those that have a focus on operating improvements versus financial engineering and those that have a focus on investing in new management versus sticking with the incumbent. These results provide one expected and one unexpected result. We do not find it surprising that private equity firms pursue strategies that are largely based on financial engineering and others pursue strategies based on operational engineering.

We then consider how those strategies are related to firm founder characteristics. We gather career history data for the founders of all 76 private equity firms in our survey. Private equity firms founded by financial general partners appear more likely to favor financial engineering and investing with current management. Private equity firms that have founders with private equity experience appear to be the most strongly engaged in operational engineering. They are more likely to invest with the intention of adding value, to invest in the business, to look for operating improvements, to change the CEO after the deal, and to reduce costs. Firms founded by general partners with operational backgrounds have investment strategies that fall in between the other two groups.

These results, while preliminary, do seem to indicate that career histories of firm founders have persistent effects on private equity firm strategy. The strategies identified for private equity firms clearly align with the firm founders careers. Future research should explore whether investments that align with the “strength” of the firm founders do better or worse in the long-run than do investments that deviate from these “strengths.”

Overall, our research indicates that the way private equity firms select companies to invest in differs substantially from what’s taught in the MBA classroom. But it confirms the basic strategies PE firms have for adding value to the companies they invest in: aligning incentives, changing management or the governance structure, and looking for operational improvements.

Leading People When They Know More than You Do

If you’re a manager in a knowledge-driven industry, chances are you’re an expert in the area you manage. Try to imagine a leader without this expertise doing your job. You’ll probably conclude it couldn’t be done. But as your career advances, at some point you will be promoted into a job which includes responsibility for areas outside your specialty. Your subordinates will ask questions that you cannot answer and may not even understand. How can you lead them when they know a lot more about their work than you do? Welcome to reality: You are now the leader without expertise—and this is where you, possibly for the first time in your career, find yourself failing. You feel frustrated, tired and disoriented, even angry. This is the point where careers can derail. If you get to this point, or see yourself headed in this direction, what can you do?

First, you need to resist your natural inclination, which is to put your head down and work harder to master the situation. Leaders who come up an expertise track almost always derail here because they react to the challenge by relying on their core strengths: high intelligence and the capacity for hard work. They frame the challenge this way: “I need to master this subject. Okay, no problem, I’m smart. I can learn.” And so they buckle down, and dive into the mastering the details so they can be an expert again. This is the road to disaster.

It is a disaster because if it took ten or twenty years to master your specialty you are not going to achieve a similar mastery in a new domain in the first 90 days—and 90 days may be all you have before you have to show results. Your staff, who know a lot more about their domain than you do, won’t respect you, your lack of confidence in the details will show when you talk to top management, and your attempt to work twice as hard as you already are will wear you down.

So what should you do instead? To succeed in this situation, you must learn and practice a new leadership style. Your old style of management, which I call “specialist management”, depended on expertise. You need to put that behind you and adopt a new style of management: the generalist style. Based on my work with leaders who have successfully made the transition, here are the four key skills to develop and practice:

1) Focus on relationships, not facts

One of the profound differences between the two managerial styles is that the specialist leader focuses on facts, whereas the generalist leader focuses on relationships. A specialist manager knows what to do; the generalist manager knows who to call. The specialist leader tells her staff the answer, the generalist brings them together to collectively find the answer.

How to focus on relationships: The single best tip for building relationships is to think about how you build relationships with clients and apply those same skills to colleagues. Spend a lot of time, face to face, getting to know people as individuals. In the generalist style you are constantly adapting your approach to the individual and the situation and that means knowing people very, very well. Flying overseas just to have dinner with an important colleague is not a waste of time—any more than it would be a waste of time to do so for a key client.

2) Add value by enabling things to happen, not by doing the work

As the expert leader it was easy to see your contribution: you were making decisions based on your unique knowledge. As a generalist you cannot do the work directly, but you can enable things to happen. A big part of enabling things to happen when you are not the expert involves knowing when to leave things alone and when to intervene. This isn’t easy because you have a broad array of responsibilities and you need to be able to tell at a glance where trouble lurks.

How to know where to intervene: How do you know where trouble lurks? One useful tactic is to sit in on a meeting between a direct report and his subordinates. If the conversation is two-way, that’s a good sign. If the manager does all the talking and the subordinates are passive, that’s a bad sign and you need to dig more deeply. Notice that you don’t need any expertise on the subject they are discussing; you just need to decide if the conversation is healthy.

Another tactic is to get feedback from your network—a network which exists because in the generalist style you focus on relationships. If your network says one of your teams isn’t delivering, but the team leader insists everything is on track, then you know there is a problem. Notice that if both the team leader and your network agree things are on track then you probably don’t need to intervene—the team leader will ask for your help if she needs it.

3) Practice seeing the bigger picture, not mastering the details

As a generalist leader much of your value comes from your ability to see the big picture better than others around you. You might think of the specialist leader as heads-down, deep in concentration, plotting a detailed course on a map, while the generalist is heads-up, looking around and noticing what is going on.

How to develop a generalist perspective: A useful tactic from consultant Rob Kaiser is to take the problem you are focusing on and see how it is affecting the people two levels below you. Then think how the problem is affecting people two levels above you. It’s a simple tactic to describe, but it really challenges you to think deeply, and you can develop a perspective that will make a real difference to the organization. Having a perspective that makes a difference is the value generalist leaders bring to the organization and one that may be noticeably absent in heads-down specialist leaders.

4) Rely on “executive presence” to project confidence, not on having all the facts or answers

When you make a presentation in your area of expertise you are confident in the facts and the facts speak for themselves. But what is it that “speaks” when the facts can’t do it for themselves? Where does the confidence come from when you are outside your area of expertise? As a generalist you must draw on that elusive quality of “executive presence” to inspire confidence in others.

How to develop executive presence: Executive presence isn’t a mystery any more than project planning is; it is a skill you develop. The most useful thing you can do is pay attention to presence. When someone who has presence walks into a meeting notice how they dress, how they speak, how they stand—these are not personality traits, they are skills. Watch some videos of world leaders on the World Economic Forum website. The specialist manager in you will want to pay attention to what they are saying, but the generalist should want to see how they are creating executive presence. Notice the relaxed body stance, the calmness in their voice, how their sentences are crisp and to the point. Notice how they connect to the audience through sincere emotion. Notice the behaviors, practice them, and get feedback—that’s the path to executive presence.

The transition to generalist management can signal the end for successful specialist managers. But if you realize that you no longer have to be, or even should be, the expert, this can be the most fulfilling and satisfying moment in your career. Your role as a leader is to bring out the best in others, even when they know more than you. The good news is that the tactics described above have helped many leaders across this treacherous gap, and they can work for you too.

How One Company Reduced Email by 64%

If you’re going to achieve growth in the knowledge economy, your employees need to be able to quickly find people inside and outside the company whose expertise can help them solve critical business problems. That takes a highly effective communication tool.

Oh, we already have that, you might say: email.

Email is indeed good for enabling employees to communicate with colleagues they already know. But it hasn’t changed much in all these years, and it remains ill-suited for helping employees find experts they don’t know, particularly in other companies.

And as younger employees join the workforce, who are used to communicating with friends via Facebook and Twitter, they find it restrictive to have to rely on email at work.

Frustrated by these limitations, the global information-technology service provider Atos, headquartered in France, sought an internal collaboration system that would do away with email’s “closed” form of communication.

It acquired social-software maker blueKiwi and combined the acquired company’s application with two from Microsoft, creating a platform that allows individuals and teams, including those in partners and clients, to enter virtual “communities” where they can collaborate on complex projects.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

The platform functions like a wiki, with members of a community — which might be based on a project, client, or topic — editing documents together and getting approval for changes from community members and other stakeholders. Each community has a volunteer leader who pledges to promote the community among colleagues. The platform ties together strands of communication such as messages and microblogs with discussion groups. It also helps participants maintain CVs that list past positions and projects, so that other community members can find people with needed skills.

The collaboration platform grew out of a 2011 announcement by Atos CEO Thierry Breton that the firm would become a “zero internal email” company over the next three years. Critics scoffed, but Atos took the challenge seriously, investing heavily in an alternative to serve its 86,000 employees in 66 countries. Gartner estimates that the company invested 500 times more than an average organization invests in social collaboration.

Despite the initial skepticism, by the end of May 2013 approximately 4,000 communities were up and running on the platform. By 2014, users had created more than 10,000 communities, some of which linked Atos to its business partners. By this year, 80,000 individuals were connected.

The investment is paying off. Atos employees now routinely use the platform for finding experts internally. For example, some of the company’s executives set up an internal “social help desk” to enable its SAP experts to increase their knowledge through exchanges with other SAP experts. The leader of this community of 2,000 members had previously tried creating the same function via email, but the SAP experts rarely read email queries, so askers weren’t getting responses. With the collaboration platform, Atos’s SAP specialists post a note with a question, and other experts within the community readily reply.

In another case, a corporate customer’s managers were expressing doubts about Atos’s value and were openly discussing dropping Atos and opening an internal IT-consulting unit. To increase the customer’s awareness of Atos’s contributions while improving communication with the customer, one Atos executive created a community that connected Atos employees to those working for the customer. By engaging with Atos’s experts directly through the collaboration platform, the customer’s executives exchanged knowledge with Atos, posted questions, and shared their experiences. This community helped the clients recognize that they were working toward a common goal with Atos. A better understanding of who they were working with at Atos also helped the customer’s executives to speed up problem solving. Thus the community helped Atos retain an important client.

Atos has grown through numerous acquisitions, and the platform has been helpful in enabling the firm to integrate its acquired companies. Atos finds that it now achieves a better level of integration, faster, than before the platform was implemented.

In the end Atos wasn’t able to hit that zero-email goal, but the platform did help the company reduce email by 64% — a big plus for employees who were suffering from email overload. Not only does the collaboration platform reduce email, it also enables community participants to filter content according to their individual needs and professional interests.

Atos’s experience is evidence that an effective collaboration platform isn’t just a tool for communication, it’s a key to achieving smooth, integrated growth and competitive advantage in the knowledge economy.

June 17, 2015

How IBM, Intuit, and Rich Products Became More Customer-Centric

How well do you know your customers? This seems to be a key question on the minds of not just marketers, but company strategists these days. We have shifted from a competitive landscape in which companies are more exclusively focused on external forces affecting their industries and sectors, to one that has become significantly more customer centric. This intensive customer focus has increased as technology-enabled transparency and online social media accelerate an inexorable flow of market power downstream from suppliers to customers. Now, every company of any scale and in any sector wants to be closer to its customers, to understand them more deeply, and to tailor their products and services to serve them more precisely.

Yet wanting to be closer with customers, and knowing what actual, operational pathways to take in order to achieve this are two very different things. In this article we look at three very different organizations – IBM, Rich Products, and Intuit – and the three different paths they have taken in reconfiguring their operations for more customer intimacy by changing methods, reengineering processes, and transforming culture.

IBM: Applying a Hybrid Design-Thinking Approach

Consider the battle waged by IBM’s software development teams between competing methods for getting closer to customers. The issue arose as a result of changes to IBM’s business model for software. In the past, IBM mostly provided enterprise software to customers who installed it on their own computers. Its product development teams followed a traditional software development method – called “Waterfall” — in which they spent months defining customer requirements and functional specifications, coding the software, and testing it for quality and reliability. They followed a sequence that resulted in new products or major updates to products every year or two.

The rise of cloud computing changed all this. Technology companies using the cloud model provide their clients software or other computer technologies in the form of services delivered over the internet. The clients don’t have to own or maintain the technology. That makes it possible for the producers of the software to improve it much more frequently, with no effort required by customers.

In response to the rapid advance of cloud computing, IBM’s software engineering groups embraced the Agile development method — with teams focused on incremental delivery of new capabilities every few weeks or months. Over time, teams adopted an even more aggressive approach to software development called “continuous delivery,” a highly automated method that enables them to make many small changes per day. This way, they can respond very quickly to new or changing customer needs, incrementally.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

At about the same time, however, IBM’s design group, which was created to improve the user experience, was adopting a new “design thinking” approach to application development. This method’s primary aim is to attain deep understanding of customer needs using ethnography, anthropology, and other user-research techniques — putting users, rather than features, first in the planning process. Designers engage directly with individual users, developing empathy, observing how they work, and uncovering surprising ideas to help make their lives better. With this approach, cross-functional teams quickly develop prototypes to bounce off of customers.

Charlie Hill, distinguished engineer and CTO, IBM Design, told us, “To deliver fundamentally different and better user experiences, designers want to take a step back and observe users actually doing their jobs. They want to understand what the user is trying to do at work, not simply how they interact with an existing application. Without this kind of understanding and exploration, a product team’s backlog of coding requirements is unlikely to deliver a compelling user experience. We want to bring our design thinking muscles to explore and play with how the user’s experience could be better in the future.”

As design expertise became more critical to the success of IBM products and services, increasingly designers worked more frequently in collaboration with software engineers on product development. They faced a culture clash, however. The designers were focused on creating better user experiences, while the engineers were focused on speed, quality, and efficiency. To the engineers, the design thinking process seemed like a return to the Waterfall method.

Phil Gilbert, general manager of IBM Design, told us: “In design thinking, you need to listen to the people doing the job, while in continuous delivery you don’t need to talk to users; you just monitor what they do on the web.”

In the end, through many discussions and much gathering of data, the company came up with a hybrid method for product development that combined elements of both approaches, which it calls IBM Design Thinking. It assembled teams for each product or service that combined designers with engineers and created a new development process. The key steps:

1) Clarify three key objectives (called “hills”) framed as target outcomes for users for each software release.

2) Engage people who are going to use the software or service (called “sponsor users”) from start to finish through the development process.

3) Demonstrate the state of the proposed solution from the standpoint of the user in periodic reviews (called “playbacks”).

This effort began two years ago, and more than 100 product teams have embraced IBM Design Thinking. These teams are delivering updates continually. Many of the updates are incremental improvements based on the data collected every time someone uses the application, and some are bigger changes to the experience resulting from insights gained during direct observation of users doing their jobs.

The new approach is working. The parts of the business where the approach is used most intensively grew revenue by double digits in 2014.

Rich Products: Achieving Customer Intimacy through Reengineering

Rich Products, a $3.3 billion food products company, has made a startling transition in its process for developing and introducing new products in response to customer requests. In Rich’s old, functional “silo-based” process, a marketing person with a new customer opportunity would contact his or her favorite R&D associate, the regulatory and quality assurance departments, packaging, and the plant. This ad hoc, sequential approach was replaced by a cross-functional team, which simultaneously accelerated its time to market and created a much more “intimate” relationship between Rich’s associates and its customers.

This transition was triggered both by struggles to meet the needs of customers with urgent turnaround requirements (such as a restaurant with a seasonal offer or a school system that needed to plan its menu) and by executives frustrated with losing the potential business from these custom orders. The pressure created by these inside and outside perspectives resulted in a strategic reengineering effort that targeted their new product development process, refocusing it to increase customer intimacy.

The first step for the process redesign team: living with the customer in order to map customer journeys. They looked at the end use of new products and asked how they could build it faster and stay close to the customer. They expanded the scope of the process to go from generating the new product idea to following up with the customer after the product launched, delivering not just a product, but a service. They mapped the process for their teams, then put the teams together to do it. And they are continuing to refine the process and remove bottlenecks, as they seek to improve new metrics for speed.

The new process design was reengineered with the customer as its main focus and the cross-functional team as its primary vehicle. Functions on the team include: process managers, dedicated coordinators, research and development, sales and marketing, operations, quality assurance, traffic, and regulatory. Rather than simply taking customers’ orders, these teams now push harder into exploring how the customer wants to use products and precisely how Rich’s can help the customer succeed. Bringing all of its functional capabilities together into one team, Rich’s can move far faster and with more agility than in its functional, sequential past. Decisions that once took weeks can now be made in moments as the team works together. These teams focus on more than just product formulation, now constantly probing customer usage, storage, and pricing plans to make sure that both Rich’s and the customer make profitable returns.

“This has been a game-changer for us,” said Maureen Lynch, the new product development process owner. “We’ve moved from ad hoc day-to-day product planning to the deployment of a long-term disciplined approach supported by purposeful metrics.” The main measure is the number of days from when a customer request comes in to when it goes out. The schedule is visible and there is clear communication about what they’re working on. They focus on fewer customer requests at a time, allowing for a more responsive turnaround.

Results have included improvements in customer satisfaction and an overall positive “Rich experience.” On-time-delivery has improved by 10%. Resource utilization accuracy has increased. Obstacles have been removed in getting resources from functional groups. And visibility has improved.

This new approach was recently on display in Rich’s participation with the “Pizza 4 Patriots” program. Using their new process design, Rich’s was able to ship 5,000 specially designed pizzas to military personnel in Afghanistan within a month to meet a Super Bowl deadline. They had a forum for a triage discussion already in place, and the group understood the requirements. They were ready to execute with a new process, clear roles, and the required tools.

Intuit: Reviving a Culture Built Around Customers

From its founding 31 years ago, Intuit has been an entrepreneurial company, creating personal finance and tax preparation products such as Quicken, TurboTax, and QuickBooks.

Intuit has always had a reputation as a customer-focused company, which is fairly unique among software companies. Hugh Molotsi, vice president, Intuit Labs Incubator, told us that in the early days (the 1990s), founder Scott Cook taught employees about observing customers and finding real problems in their lives and solving them. There were “usability labs” where customers would try products and employees would observe them and see where they had problems, and “Follow Me Homes” where employees would observe customers at work and at home. And they had an annual big survey to gather customer insights.

But as Intuit grew, informality and entrepreneurship began to morph into procedure and bureaucracy. The focus on customers slowly turned into a hunt for “bugs” and problems rather than acutely listening for and responding to customer needs. In other words, the traditional visits to customers were more focused on problem-solving than discovery. They were “fixing” rather than learning.

As Suzanne Pellican, vice president and design fellow at QuickBooks, told us, “The vast majority of our growth comes from word of mouth. When you fix bugs, it doesn’t generate enthusiasm from our customers. Fixing a bug isn’t compelling to get them to recommend us. We weren’t surpassing customers’ expectations. And it showed in our Net Promoter Scores. They were flat.”