Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1284

June 15, 2015

Focus On the Customers You Want, Not the Ones You Have

In the 1990s, I worked for a company whose tag line was: “We build digital businesses.” What many entrepreneurs quickly realize is that building the business is often the easy part. Growing and maintaining the business can be much tougher and figuring out how to appeal to new consumers is no small feat.

One reason is that consumers are far from homogeneous. Different segments have different risk tolerances, ways of making decisions, and — perhaps most challenging for growing businesses — preferences for when and how they adopt innovations.

After Everett Rogers famously made the distinction between early and late adopters, academics in marketing and technology identified a number of differences between those who take quickly to innovations and those who don’t. Early adopters are typically younger, more willing to take risks, more eager to try new things, more affluent, and substantially less numerous.

For digital businesses looking to grow, these distinctions lead to two important consequences. First, what worked with early adopters isn’t likely to work with later adopters. In launching new products or services, start-ups tend to accumulate deep knowledge about customers at the leading edge of a technology. But that knowledge doesn’t necessarily apply to other consumer groups; that’s one reason so many new firms struggle to create second rounds of offerings. To be successful, companies need to innovate for the consumers they want, not the ones they have.

Insight Center

Growing Digital Business

Sponsored by Accenture

New tools and strategies.

Take Snapchat, for example. The company built its current market and reputation on photo- and video-sharing technology that was intended to be temporary — pictures and messages disappear within 10 seconds of being viewed. While the app is notoriously viewed as a medium for sexting, most users seem to use it simply for entertainment, taking pictures of silly and amusing things to share with friends. But now Snapchat is looking to move beyond its early adopters — many of whom are students with minimal purchasing power — and get into a broader and more lucrative demographic. This has meant offering fundamentally different types of content, including mini-TV series (see the announcement from Sofia Vergara) and news (see the hiring of ex-CNN correspondent Peter Hamby).

Second, early adopters often view later adopters with disdain, especially if the offering can be seen as a status symbol or there are opportunities for different user groups to interact. Remember that sinking feeling you had when your mother joined Facebook? That’s what I’m talking about.

In extreme cases, an inflow of late adopters can prompt early adopters to abandon a business entirely. There are many reasons why MySpace failed, but early users’ frustration with the invasion of businesses and unsophisticated consumer groups undoubtedly played a significant role.

Given the relatively small size of the early-adopter pool, sacrificing a few first-generation users may seem like a minor loss and a worthwhile trade-off. But original users confer a certain legitimacy to a business. Moreover, these risk-seeking, innovative, exploratory consumers pose a potential competitive threat if they become disenchanted and leave. They may wind up leading the charge for — or even founding — a competing business that they feel is truer to your business’s original purpose. While there is no way to know for sure, it is likely that the early adopters of Google’s search, the iPhone, and Facebook included many disenchanted early adopters of Yahoo!, Blackberry, and MySpace.

If that happens, you may find yourself in the midst of a competition between user generations or in a fad cycle where start-ups’ short-term popularity is followed by saturation and then by the birth of new start-ups, and so on. Twitter or even Facebook may be vulnerable to this type of cycle.

What to do?

Make sure your innovation efforts are aimed at the expectations and needs of the next wave of adopters, not just those on the leading edge. Firms often have much more data on current users than prospective customers, and in organizations that put a lot of emphasis on data, the consequence is that projects targeting existing users tend to win resources while those targeting new ones don’t. Firms need something other than beta testing with existing users to figure out how late adopters might respond to a given innovation. Identify the demographics and characteristics of specific potential adopter groups, then use classic tools like focus groups (online or offline) to gain a better understanding of the needs and wants of the next wave of adopters.

At the same time, actively engage early adopters to ensure that they remain connected to and happy with the business. Even after these early adopters have served their purpose as tastemakers who helped to bring in new consumers, they are still important to the business. Making sure you don’t lose them can reduce long-term risk. Amazon’s continuous innovation through its Prime program has played a significant role in giving heavy-using early adopters a reason to remain connected to the brand and the company.

By being aware of the differences between adopter groups and taking those differences into account for strategic decisions, you can help your digital business move past “build” and into “grow.”

Simplify Your Analytics Strategy

While the interests in analytics and resulting benefits are increasing by the day, some businesses are challenged by the complexity and confusion that analytics can generate. Companies can get stuck trying to analyze all that’s possible and all that they could do through analytics, when they should be taking that next step of recognizing what’s important and what they should be doing — for their customers, stakeholders, and employees. Discovering real business opportunities and achieving desired outcomes can be elusive.

To overcome this, companies should pursue a simpler path to uncovering the insight in their data and making insight-driven decisions that add value. Following are steps that we have seen work in a number of companies to simplify their analytics strategy and generate insight that leads to real outcomes:

Accelerate the data: Fast data = fast insight = fast outcomes. Liberate and accelerate data by creating a data supply chain built on a hybrid technology environment — a data service platform combined with emerging big data technologies. Such an environment enables businesses to move, manage, and mobilize the ever-increasing amount of data across the organization for consumption faster than previously possible. Real-time delivery of analytics speeds up the execution velocity and improves the service quality of an organization. For example, a U.S. bank adopted such a technology environment to more efficiently manage increasing data volumes for its customer analytics projects. As a result, the firm experienced improved processing time by several hours, generating quicker insights and a faster reaction time.

Delegate the work to your analytics technologies. Uncovering data insights doesn’t have to be difficult. Here are ways to delegate the work to your analytics technologies:

• Next-Gen Business Intelligence (BI) and data visualization. At its core, next-gen business intelligence is bringing data and analytics to life to help companies improve and optimize their decision-making and organizational performance. BI does this by turning an organization’s data into an asset by having the right data, at the right time and place (mobile, laptop, etc), and displayed in the right visual form (heat map, charts, etc) for each individual decision-maker, so they can use it to reach their desired outcome. When the data is presented to decision-makers in such a visually appealing and useful way, they are enabled to chase and explore data-driven opportunities more confidently.

For example, a financial services company applied BI and data visualization to see the different buckets of risk across its entire loan portfolio. After analyzing its key data and displaying the results via visualizations, the firm identified the areas in the U.S. where there were high delinquency rates, explored tranches based on lenders, loan purposes, and loan channels, and viewed bank loan portfolios. Users were also able to interact with the results and query the data based on their needs — select different date ranges, FICO scores, compare lenders and loan types, etc. Due to the flexibility and data exploration capabilities of the interactive BI and visualization solution, insight-driven decisions could be made and actions could be pursued that would benefit the business.

• Data discovery. Data discovery can take place alongside outcome-specific data projects. Through the use of data discovery techniques, companies can test and play with their data to uncover data patterns that aren’t clearly evident. When more insights and patterns are discovered, more opportunities to drive value for the business can be found. For instance, a resources company was able to predict which pipelines are most risky from both physical and atypical threats through data discovery techniques. Due to the insights gained, the firm was able to prioritize where they should invest funds for counter-failure measures and maintenance repairs.

• Analytics applications. Applications can simplify advanced analytics as they put the power of analytics easily and elegantly into the hands of the business user to make data-driven business decisions. They can also be industry-specific, flexible, and tailored to meet the needs of the individual users across organizations — from marketing to finance, and levels from C-suite to middle management. For example, an advanced analytics app can help a store manager optimize his inventory and a CMO could use an app to optimize the company’s global marketing spend.

• Machine learning and cognitive computing. Machine learning is an evolution of analytics that removes much of the human element from the data modeling process to produce predictions of customer behavior and enterprise performance. As described in the Intelligent Enterprise trend in the Accenture Technology Vision 2015 report: With an influx of big data, and advances in processing power, data science and cognitive technology, software intelligence is helping machines make even better-informed decisions. As an example, a retailer combined data from multiple sales channels (mobile, store, online, and more) in near real-time and used machine learning to improve its ability to make more personalized recommendations to customers. With this data-driven approach, the company was able to target customers more effectively and boost its revenues.

Recognize that each path to data insight is unique. The path to insight doesn’t come in one single form. There are many different elements in play, and they are always changing — business goals, technologies, data types, data sources, and then some are in a state of flux. Another main component of a company’s analytics journey depends on the company’s culture itself: is it more conservative or willing to take chances? Does it have a plethora of existing data and analytics technologies to work with, or is it just starting out with its first analytics project? No matter what combination of culture and technology exists for a business, each path to analytics insight should be individually paved with an outcome-driven mindset.

To do this, companies can take two approaches depending on the nature of the business problem. First, for a known problem with a known solution — such as customer segmentation and propensity modeling for targeted marketing campaigns — the company could take a hypothesis-based approach by starting with the outcome (e.g. cross-sell/up-sell to existing customers), pilot and test the solution with a control group and then scale broadly across the customer base. Second, for a known problem area, fraud for example, but with an unknown solution, the company could take a discovery-based approach to look for patterns in the data to find interesting correlations that may be predictive—for instance, a bank found that the speed at which fields were filled out on its online forms was highly correlated with fraudulent behavior. Of note, when determining which problem to address, companies should first focus on the one that can offer the highest value, then it can choose a hypothesis-based or discovery-based approach based on the degree of institutional knowledge it has to solve that kind of problem.

Once insights are uncovered, the next step is for the business, of course, to make the data-driven decisions that place action behind the data. It is possible to uncover the business opportunities in your data and increase data equity, simply.

The Age of Smart, Safe, Cheap Robots Is Already Here

Robots have been doing tough jobs for over half a century, mostly in the automotive sector, but they’ve probably had a bigger impact in Hollywood movies than on factory floors.

That’s about to change.

Today’s robots can see better, think faster, adapt to changing situations, and work with a gentler touch. Some of them are no longer bolted to the factory floor, and they’re moving beyond automotive manufacturing. They’re also getting cheaper.

These improvements are helping to drive demand. In fact, we expect the global industrial robot population to double to about four million by 2020, changing the competitive landscape in dozens of fields — from underground mining to consumer goods and aerospace manufacturing. Robots will allow more manufacturers to produce locally and raise productivity with a knowledge-based workforce.

These changes have profound implications for millions of laborers around the world and thousands of companies. Manufacturing footprints are likely to change substantially, and new business models will emerge to help innovators tap new opportunities and disrupt industries.

Three powerful trends are spurring the rise of the machines.

1. They’re much cheaper. As technology has advanced and robot production has scaled up, costs have fallen by about 50% since 1990 — while U.S. labor costs have risen 80%. In China, manufacturing wages have risen five-fold just since 2008 as employers have chased workers eager to switch jobs for better pay.

Not surprisingly, Chinese companies are automating at an accelerating rate. Foxconn, which employs more than a million workers in mainland China, plans to automate 70% of its assembly work within the next three years. Before then, the nation should account for more than half of worldwide robot sales, according to the International Federation of Robotics.

2. They’re smarter and more autonomous. Advances in artificial intelligence and sensor technologies are giving robots the power to cope with task-to-task variability. Flex Track robots now crawl around airframes on their own, “seeing” exactly where to drill without human intervention.

Far more advanced sensors, and the computer power needed to analyze the data flowing from those sensors, will allow robots to take on complex, delicate tasks, such as cutting gemstones, that previously required highly skilled craftspeople.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

Advances in automated guided-vehicle technology are giving robots the mobility needed for underground mining, warehouse navigation and parts delivery in manufacturing plants — just the beginning of what will be possible in the next 10 years.

The data generated in these activities will travel along the digital thread to help designers, engineers, and managers understand the drivers of quality, process time, flow, and inventory in real time. Companies that can harness this data, will improve their products and processes faster than competitors.

3. Safer, gentler machines are integrating with the workforce. Advanced safety systems are making it possible for people and robots to work side by side, complementing each other’s strengths. Robots can now detect the proximity of operators and adapt their speed, force, and range of motion to prevent collisions, making it far easier to assign tasks to robots in otherwise manual assembly lines.

While today’s general-purpose robots can control their movements to within a tenth of a millimeter, new assembly robots will be accurate to within two hundredths of a millimeter with high dexterity. Their vision and force-sensing abilities will allow them to participate in increasingly delicate handling and assembly tasks, such as those required for sophisticated electronic devices. One robot manufacturer says its machines can already thread a needle.

They’re also getting more coordinated. With controllers that can simultaneously drive dozens of axes, multiple robots can work together on the same task.

At one car company, collaborative robots now work side by side with people to assemble doors. The robots apply water seals exactly the same way every time with far less variability than human workers can manage, preventing leaks that could damage the doors’ costly mechanical and electrical systems, which the humans install. At a jet manufacturer, twin-armed humanoid robots turn on multiple axes and combine vision and artificial intelligence to locate each work piece and adapt to its specific condition.

Industry leaders are already capturing value. A multinational company struggled for years to coordinate the flow of multiple products and steam pressures among the units of a fertilizer operation, resulting in an estimated 10% in lost revenues. Engineers installed sensors at each step in the process and an artificial intelligence and machine learning system to track and adjust changes in flows across units. Efficiency improvements have cut the revenue losses by three-quarters so far, in effect boosting revenue by 7% to 8%.

A mining company now uses tele-remote and semi-autonomous underground load-haul dumpers controlled from the surface. Production variability has declined, and with fewer people underground, safety, productivity and labor utilization have improved. Overall equipment effectiveness has also risen, and automated guidance systems mean fewer collisions and less damage to equipment.

A packaged goods manufacturer raised productivity by installing 22 automated guided vehicles to deliver materials to and from the line. A small team can now oversee the work of the vehicles, provide quality control, collect and organize data from the product and process, and drive problem-solving efforts for continuous improvement. This transformation of a human role — from forklift driver to analyst, from cog to contributor — reflects one of robots’ most meaningful contributions to the labor force.

Implications for the workforce. Yes, robots will replace some people who now perform manual work. But they will also require companies large and small to employ thousands of workers with skills in analytics, programming, system integration, and interaction design. Ambitious workers — especially those with access to training — will gain new perspectives and new opportunities to contribute.

Robots can do some things better and faster than we can, but they’ll never completely replace human perspectives or judgment. They’ll just do more of the math, pound more of the rivets and thread more of the needles, sometimes on their own and sometimes with a member of the frontline team.

How to Make Unlimited Vacation Time Work at Your Company

When Netflix’s founder Reed Hastings published the company’s Reference Guide on our Freedom and Responsibility Culture on SlideShare it made an unexpectedly huge impact. The slide deck itself was viewed over 11 million times, and newspapers around the globe picked it up. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg called the deck the most important document ever to come out of Silicon Valley.

Out of the 128 slides in the document, the one most people remember was about unlimited vacation. Or more specifically, a “no vacation policy” policy. Netflix’s leaders had decided to stop tracking how many vacation days its employees were taking. The rationale, according to the slide deck, was: “We realized we should focus on what people get done, not on how many days they worked. Just as we don’t have a 9am-5pm workday policy, we don’t need a vacation policy.” Instead, employees take as much or as few vacation days as they feel they need.

The reaction since has been mixed. Some companies, such as Richard Branson’s Virgin, reacted by adopting similar policies. A few of these implementations failed spectacularly and publicly. Skeptics have argued that employees with unlimited vacation actually feel pressured to work more, work during their vacations, and take fewer days off altogether.

For the most part, whether or not these fears become reality is a matter of culture and whether or not your culture has one crucial element: trust.

Leaders who successfully implement unlimited vacation policies operate in companies that are already high in trust. But there’s some evidence to suggest that showing trust in others actually helps them trust you more – researchers who study game theory consistently find that when one person shows faith in another, the second person’s faith in others also rises. They’re also more likely to pay that trust forward, by trusting third parties who weren’t involved in the additional transaction. So there’s some theoretical evidence that implementing such a policy not only takes advantage of existing trust, but builds additional trust.

That’s exactly what Netflix experienced. Shortly after the unlimited vacation experiment, Netflix leaders shortened the travel and expenses policy considerably. Instead of dictating when and how money should be spent and reimbursed, they wrote five simple words: “Act in Netflix’s best interest.” Just as with the vacation policy, the response to this act of trust was responsible behavior by employees (and actually a cost savings since employees didn’t need to go through a costly travel agency any more.)

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Managing Yourself

Managing Yourself Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Switching from a traditional vacation policy to unlimited vacation can be tricky. It’s always difficult to be the one extending trust, hoping employees will believe your act to be sincere and reciprocate. In many cases, organizations that make the switch successfully also make sure that managers get excited when employees take their days off. In addition, many managers and senior leaders get very public about taking time off and taking it in long stretches. That way the message is clear that taking vacation won’t hurt your performance review or career prospective. Some companies, at least initially, went so far as to bribe employees to take their vacation: for example, software company Evernote pays employees a $1,000 bonus if they take a week or more vacation. Marketing company HubSpot lets salespeople reduce their monthly quota twice a year to coincide with their vacation time.

On an individual level, the benefits of unlimited vacation can get even better if the culture of trust extends laterally as well. Windsor Regional Hospital, which switched to unlimited vacation a few years ago, found that in addition to coming back to work well-rested, employees began working better together too. Before the switch, a co-worker taking time off was seen purely negative, a hole that other employees were obliged to fill. Now, keeping the hospital running is seen as a team effort, and that teamwork has spilled over beyond just setting schedules. Employees know they can trust their coworkers to cover for them when they take time away. So, when they’re back on the job, they know they can trust each other just as much.

These are just a few of the ways that show that unlimited vacation isn’t about how much or how little time off your employees take. Instead, it’s a means to gauge whether or not employees trust leadership, which starts with leaders trusting employees. If you’re a senior executive trying to decide whether such a policy is right for your company, know that if your organization hasn’t built a culture where leaders trust followers and followers trust leaders, then unlimited vacation probably won’t work.

But, you probably have bigger issues to tackle first anyway.

Why CEOs Don’t Get Fired as Often as They Used To

The number of chief executive officers who were dismissed from their jobs at large global companies fell to a record low last year. At first glance that might suggest complacency on the part of boards of directors, but it’s actually good news about corporate governance in general and CEO succession planning in particular. It means that boards are doing a better job of choosing top leaders — far better than they were doing a decade ago. Data for the world’s largest 2,500 companies also suggests that better CEO succession practices are converging around the world, as regional differences in CEO succession rates have narrowed sharply in recent years.

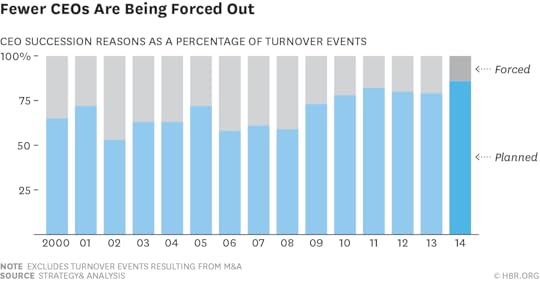

The reduction in forced successions indicates that boards of directors have become significantly more practiced at selecting the right chief executives, and planning and executing smoother transitions from one to the next. From 2000 to 2008, the average number of planned successions as a percent of turnover events per year (excluding turnover events resulting from M&A) was only 63%. But from 2009 onward, the percentage of planned successions has steadily increased, to a record 86% in 2014. Forced turnovers have become much less common. In 2004, for example, 37% of departing CEOs were forced out, but in 2014, that figure had fallen to 14%.

One reason for this improvement may be the increased focus on corporate governance over the 2000-2014 period, starting with the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the U.S. in 2002, as well as significant corporate governance reforms in the U.K. and the European Union. Momentum for increased transparency in governance and for better-qualified and more independent directors has continued to the present, as has the convergence of governance standards. At the same time, increased regulation has also heightened compliance risks for companies and their directors, underscoring their duty to choose senior leaders carefully. The rise of “activist” investors, which challenge boards at companies where shareholder returns are lagging, may also be a factor.

But a more fundamental reason for better CEO succession practices is that directors and senior corporate leaders are learning from the mistakes of the past. It has become increasingly clear that unplanned CEO changes — which are evidence of underlying problems with CEO succession practices — are bad for corporate performance and are very costly to shareholders. We quantified these costs in Strategy&’s annual Study of CEOs, Governance, and Success, which estimated that companies that fire their CEOs forgo an average $1.8 billion in shareholder value compared with companies that have planned successions.

If a failed CEO succession is so costly, then how does it happen? We found that failed successions are typically a result of boards not paying close enough attention to the senior leadership pipeline. Instead, they’ve often delegated the job of finding a replacement to the incumbent CEO. Boards at companies that have to fire their CEOs also tend to rely overly on candidates’ track records, effectively making their choices based on what worked in the past rather than on what will work in the future.

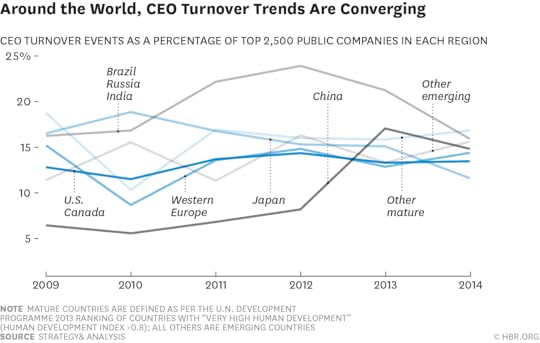

We’ve also seen global CEO succession rates converge in recent years, as the exhibit below shows. In 2004, the global rate of successions at the world’s 2500 largest companies was 14.7%, and the spread between the lowest regional rate (North America, at 12.8%) and the highest (the BRIC countries, 23.9%) was more than 11 percentage points. In 2014, the global rate of successions was slightly lower, at 14.3%, but the spread between the highest (Other Emerging countries, 15.9%) and the lowest (North America, 13.2%) had fallen to less than three points.

It is a similar story with regional rates of planned successions. In 2004, the global rate was 7.7% for all companies, with a spread of more than 15 percentage points between the highest and lower regional rates. In 2014, the global rate had risen to 11.2%, and the spread between the highest and lowest regional rates was only 5.1 points.

The fact that succession rates are more universally aligned is a sign of continued globalization. Governance practices have been converging steadily since 2000, capital has become increasingly mobile, and senior leaders at the largest corporations find themselves, more and more, facing the same kinds of challenges and opportunities no matter where they are headquartered or where they do business. In addition, we hypothesize that the benefits of better succession planning are becomingly increasingly well understood worldwide.

The long-term improvement in CEO succession practices and the global convergence we have seen has benefited shareholders, and there is room for significant further improvement. We estimate that if the world’s 2,500 largest companies continue the trend toward more planned CEO changes — to the point that they reduce the share of forced turnovers to 10% from the average of 18% over the last three years — they could collectively generate an additional $60 billion in shareholder value.

June 12, 2015

Get What You Need from Your Hands-Off Boss

It’s nice when your boss trusts you. But some managers let you have such a long leash that they don’t know what you’re really doing or can’t provide the feedback you need. Worse yet, it’s difficult to tactfully request more involvement without pushing your boss further away. How do you work with a manager who is too hands-off? And if she resists, is it possible to get what you want from her in other ways, or from someone else?

What the Experts Say

Having a passive boss can be a frustrating experience. “They don’t know the details, they don’t want to know the details, and they don’t follow up. You might wonder what they do all day long,” says Jean-Francois Manzoni, a management professor at INSEAD and author of The Set-Up to Fail Syndrome: How Good Managers Cause Great People to Fail. Many bosses don’t give enough direction, provide feedback on your work, or fight for the resources you need. “Of course, people like to feel trusted and depended on, but there are drawbacks: you may not get the recognition or appreciation you need,” says Annie McKee, cofounder of Teleos Leadership Institute and author of several books on leadership, including Primal Leadership. Your boss may not be a bad person or even an incompetent manager. “Too many managers are just too busy to manage well,” she says. Whatever the reason for your boss’s hands-off approach, you don’t have to accept it. Here’s some advice on how to get what you need from an overly passive manager.

Start with you

First things first: ask yourself why your boss isn’t giving you as much support as you’d like. Are you the sole person who feels alienated, or is it the entire team? “If the only person not getting support is you, you might be the cause of the disconnect,” says Manzoni. When people don’t get what they want from their boss, it can cause disenchantment, resentment, and cynicism — emotions that are hard to hide. If you’re annoyed and irritated with your boss, it’s going to show whether you use the words or not. “If we work together regularly, I will know that you think I’m a schmuck. And if that happens, you won’t be getting more attention from me,” says Manzoni. Try to look objectively at the situation so you’re not placing all the blame on your boss when you may be contributing to the problem.

Avoid labels

Negative labels change the dynamic of the relationship and affect the way you look at working with your boss. Manzoni worked with a client who aggravated a situation by labeling her boss a “slacker” and a “schmoozer.” She didn’t call him names to his face but this was how she thought of him. “This lady was the task-focused, industrious type, while he focused on fostering relationships,” says Manzoni. “She believed she was doing all of the work.” Manzoni helped her realize her boss was working in a different way; he used his extensive network to benefit their team. No matter how frustrated you feel, don’t label your boss. Doing so only reinforces your frustration and diminishes your ability to see your boss’s work from a positive angle. Instead, focus on the helpful aspects of your boss’s leadership. “If your boss is capable of managing up, and has a great network, and if he can share those resources with you, then enjoy it,” he says. No one is hands-off 100% of the time so appreciate your manager’s different leadership styles.

Practice compassion

You can manage your frustration by seeing things from your boss’s perspective. Are these his natural tendencies, or is something pushing him to be more distant than usual, like stress? By putting yourself in your leader’s shoes, you’ll be able to better understand the reasons for his behavior — and you’ll be better prepared to respond.

Then try giving your boss what you want. “If you feel you’re missing support or appreciation, find opportunities to appreciate your boss in private and public,” McKee says. It’s not necessary to fawn, but find real reasons to appreciate their efforts and what they do well. Give them recognition for what they’ve helped the group achieve. “When people are treated that way, they often start reciprocating,” says McKee.

Focus on your needs

“If you approach your boss with aggression or anger, you’re just going to push him or her into a corner; they’ll become defensive, angry, and they’ll feel ‘less than’ as opposed to valued by you,” McKee explains. Before you address the issue with your boss, redefine the situation. “When you say ‘I want to approach my boss because they’re too hands-off,’ you’ve already judged this person,” says Manzoni. Reframe it as having a conversation about your needs, and be prepared to define exactly the kind of support you’re seeking. Are you looking for a weekly call, a monthly meeting, or quicker email responses? When you have the conversation, make it a two-way interaction and find out what your boss needs as well. Assure her that you’re committed to her and share what you like about her management approach. “Then she knows that you understand the good side of her style, and that you’re just asking for a little more in one area,” Manzoni says. That puts your boss in an open frame of mind, and then it’s just a question of whether she can give you what you want or not.

Know when to move on

There’s a fine line between being persistent and being stubborn. “Ask once, twice; if you see no progress or movement, it’s time to accept how they are as a leader,” says Manzoni. Recognize that there are times you’ll be in a situation where you won’t get what you need, no matter what you do. “When that happens, you have three choices: change how you feel about it, get your needs met elsewhere, and if you’re really unhappy, find a different job with a different boss,” says McKee. Find another person within your organization who can mentor and support you.

Step into leadership

In some cases it might be time for you to step up and take the lead. “In the best case, a hands-off boss will at least set the direction and provide an inspiring vision” before moving out of the way, says McKee. “This can be powerful and motivating for many people.” Look for ways to take on responsibility that will lighten your boss’s load, and to support those around you, especially if they’re experiencing the same lack of leadership. Having a hands-off boss can be a blessing in disguise as it might be just the opportunity you need to fill the void in leadership. And when others, including your manager, recognize that you’re doing that, you may well be rewarded.

Principles to Remember:

Do:

Examine your own part in the disconnect between you and your leader

Practice empathy and try to understand the situation from their point of view

Seize the opportunity to step up and take responsibility

Don’t:

Label your boss with negative monikers — understand there may be reasons for his behavior

Approach with accusations — make it a two-way conversation about mutual support

Harp on the situation — know when to move on and seek support elsewhere

Case Study #1: Adjust your approach to get what you need

William Powers works with a bitcoin crypto currency company and is responsible for raising investor capital. William and Jon, the CEO of the company, work remotely and communicate mostly by email. When they first started working together, William sent Jon long emails loaded with detailed information and questions about the software application developments. “Jon would respond, but he wouldn’t give me with answers,” says William. The less Jon said in his emails, the more William felt frustrated. It was hard to hide his irritation and he began to subtly point out that Jon lacked a clear vision and failed to communicate. Jon eventually stopped answering his emails altogether.

William looked at his own behavior within their relationship and realized he needed to adjust the way he communicated. He saw that his boss was busy and didn’t have time to wade through long emails and composing thorough responses. So rather than harping on the lack of updates or direction, William began formatting his emails to include one action item. Then he listed his questions — never more than two at a time. “I made it exceedingly simple and easy to respond to my questions. Essentially, I was selling him on answering the email,” jokes William.

After William changed the way he communicated, Jon’s leadership style became much less of a problem for him. “He answered questions much more quickly, and I was able to take the information he provided and use it to raise capital with investors and gain media attention,” says William. Their relationship improved, as well. “It wasn’t like night and day, but it was a big improvement.”

Case Study #2: Fill the leadership void

Kyle Scifert served as a staff sergeant in an Army military police company during the initial invasion of Iraq. He was in charge of leading 11 enlisted soldiers and turned to his supervisor, platoon leader Natalie (not her real name), for guidance when preparing for missions. But he didn’t get the guidance he wanted. “She made the assignment, but failed to give any feedback about potential issues or how to complete the mission,” he explains. His requests for more information went unmet and Kyle often felt he was unprepared. To make matters worse, Natalie criticized every one of his decisions during his debriefing. His team started to suffer from the overall lack of leadership; morale was low, and his team members didn’t feel confident in the mission.

Kyle realized it was time to step up. Instead of seeking Natalie’s guidance to prepare for missions, he took matters into his own hands. “I started doing as much research as I could on each mission, and then I shared that research with other squad leaders,” says Kyle. As a result, he was much better prepared for each mission and began to stand out as a leader; in fact, other staff sergeants came to him for guidance about their own missions.

At first, Natalie wasn’t pleased that he was taking this initiative, but it wasn’t long before they reached a new level of respect for one another. “It was difficult at times, but eventually she recognized that I had stepped up as a leader and credited that initiative,” says Kyle. Natalie recommended him for officer school, and he went on to become an officer. “It didn’t necessarily change her behavior,” says Kyle, “but it lead me to become a better leader.”

Innovation Starts with the Heart, Not the Head

I recently got a call from a CEO of a health system that encompasses several hospitals, medical practices, and clinics. Lakeland Health employs about 4,000 associates and takes in nearly $500 million per year. Its facilities are spread across the southwest corner of Michigan — where median income is 70% of the national average and the incidence of chronic diseases is substantially higher than the norm. It’s a challenging environment in which to be a healthcare provider.

The CEO knew I was a fan of passion-fueled innovation and thought he had a story I’d find inspiring, hence the call. A year earlier he had taken up his new post at Lakeland. Shortly thereafter, he had called a meeting to review patient satisfaction scores. U.S. hospitals have to report this data to the federal government, and if they fall below certain thresholds, they pay a penalty in reduced reimbursement rates. Given that, the CEO was distressed to learn that when it came to patient satisfaction, Lakeland was a laggard — with scores between the 25th and 50th percentile. How could this be?

His senior team told him it wasn’t for lack of trying. Lakeland tracked the things that drove patient satisfaction — response times to call lights, pain management, the quality of the food, the effectiveness of patient communication, and so on. By most of these metrics, the care compared well with others in the industry — but this wasn’t showing up in the overall satisfaction scores. Part of the problem, the execs suggested, was the hardship and ill-health that surrounded them. Lakeland drew from a shallow hiring pool and had to treat a disproportionate number of seriously ill and often uninsured patients. Many were frequently readmitted when they failed to follow post-care instructions. Having benchmarked other hospitals, Lakeland’s leaders knew that more favorably located hospitals typically achieved higher patient scores with similar service levels. Conversely, hospitals in comparable locations delivered scores that more or less matched those at Lakeland.

How, the CEO wondered, could Lakeland reinvent the experience of healthcare for its patients? Lakeland had a team of service leaders who were responsible for benchmarking and applying best practices, and there didn’t seem to be a lot more that Lakeland could learn from its peers. Neither could the problem be solved with money. Lakeland didn’t have the cash to make big investments in additional staff or new patient amenities.

After a few weeks of reflection and some personal soul-searching, the CEO thought he had a plan. What would happen, he wondered, if Lakeland’s associates brought their hearts to work, as well as their professional skills?

With this thought in mind, he asked his team to rent cinemas in three cities and sent around a schedule of more than 20 kick-off events. The theme, plastered on posters at each venue, was “Bring Your Heart To Work.” Over the next several weekends, nearly all of Lakeland’s staff showed up at one of the events. The CEOs message was simple, unexpected, and daunting: None of us aspire to work in an organization that frequently lets down its customers. We can and must do better than this. So let’s set a goal of getting to the 90th percentile in 90 days. We can’t scale up much in the way of additional resources, so we’re going to have to be resourceful. We’re going to raise our scores by touching the hearts of our patients — by making sure they know not only how well we care for them, but how much we care about them. We’re going to learn to be more loving. To do that, he said, I want to challenge you to bring your heart to work in new and creative ways.

For a nurse or an x-ray tech with 10 or 20 years of experience, delivering health care is a routine. But for a patient, the experience is anything but. Lakeland’s CEO reminded his associates that a hospital visit is one of the most emotionally charged events any human being can ever experience—something that is remembered for years afterward. Borrowing from research done at Florida Hospital, he characterized a hospital visit as a drama in three acts. First, there’s admission—typically accompanied by pain, fear and anxiety. Next is in-patient care, which often involves alternating bouts of discomfort and boredom. Third is discharge, when out-going patients often feel unprepared or even abandoned. Using associates to play the role of patients, the CEO demonstrated how each stage of the drama offered opportunities to create loving connections with patients — by demonstrating concern and tenderness, and providing consolation and cheer.

The CEO didn’t offer his associates a script or a training program. Instead, he challenged them: “Every time you interact with a patient, tell them who you are, what you’re there to do, and then share a heartfelt why. For example, ‘I’m Tom, I’m here change your dressings, ‘cause we want you home in time for your granddaughter’s wedding.’” The heartfelt why needed to be stated in a way that put the patient’s hopes and fears at the center of the healthcare drama.

Over the next 90 days, the CEO “rounded” 120 times. He showed up in every department, on every shift, in every facility. “How’s it going?” he’d ask. “Have you made any heartfelt connections? If so, tell me about it. If not, let’s role-play right now. Let me be the patient.”

Initially, many of his associates struggled to come up with a “heart-felt” why. Despite all the caring that goes on in health care, making it personal doesn’t always come naturally. It takes practice. “How will we know if we’re succeeding?” was the most frequent question directed at the CEO. His answer: “You’ll see it in a patient’s smile, you’ll here it their voice, you’ll sense it when they take your hand — and ultimately, you’ll feel it in your own heart.”

Over the ensuing months two things became apparent. First, success required that everyone, every day, opened their hearts to those they were caring for. One person with a bad attitude could undo the heartfelt efforts of a dozen colleagues. Not surprisingly, front line employees and their managers started to become less tolerant of colleagues with crappy attitudes. In the end, more than a few of the curmudgeons were asked to leave.

And second, though the focus of the CEO’s initiative wasn’t on call-light response times, pain management, or discharge planning, patient scores on all these conventional metrics started to climb as the heart-to-heart message took hold. The lesson: love someone better, and they’ll extend you grace on all the less important things.

Before long, Lakeland was reverberating with stories about heartfelt connections. So how to thank all of those who were bringing their hearts to work? Here, too, the CEO had a plan. Whenever a patient or a colleague reported a small act of heartfelt service, a senior leader would show up within minutes to personally thank the warm-hearted associate. Surrounded by their nearby co-workers, the leader would retell the story, thank the individual, and pin a heart on their badge. Over the course of a few months, more than 6,000 stories were celebrated across Lakeland, and more than 6,000 hearts were affixed to employee IDs.

Listening to all of this, I asked the CEO to share a typical story:

There was a wicked commotion in the hall, and two security officers suddenly found themselves facing a husband in complete emotional melt down. He had come in with his wife who was desperately ill. After the medical work-up, he was told that his wife was dying of cancer and probably won’t leave the hospital alive. The news struck like a thunderbolt, and he simply lost it. Having been called to the scene, the security guards were ready to phone the police when an associate nurse comes around the corner. Seeing the distraught husband lashing out at everyone around him, she walked up to him and calmly asked, ‘Can I hug you?’ When the man nodded yes, she wrapped her arms around him and for the next 20 she held him as he wept into her uniform. Finally calm, he returned to support his wife and the nurse went on with her duties. She was an LPN, who had never been through any course on conflict management, or de-escalation, but she had heard lots of stories about how to connect with another human being.

“Now,” the CEO continued, “not every story is that dramatic, but many of them will bring a tear to your eye and all of them will put a smile to your face.” Some associates simply found a more thoughtful way to say something to a patient. For example, a receptionist responsible for scheduling follow-up appointments, discovered that she was more likely to get a smile when she switched from saying “the doctor wants you back in two weeks,” to, “the doctor would like to invite you back in two weeks.” That was a tiny change but it made a positive emotional difference.

But, as the CEO constantly reminded his colleagues, little things could also destroy a patient’s emotional equilibrium. He frequently recounted a conversation he’d had with a mother who’d delivered a child at Lakeland several years earlier. The newborn had arrived healthy and happy, but as the mother recounted her birthing experience, her eyes filled with tears. Upon arriving at the hospital, the first person she encountered in the OB unit had failed to look up and greet her with a welcoming smile. When you’re an expectant mother, both hopeful and anxious, you need a bit of reassurance—and it hadn’t been forthcoming. Years later, that disappointed mom still remembered the cold welcome she’d received.

“So,” I asked the CEO, “6,000 stories later, how did this all turn out?” “Well,” he replied, “within 90 days we were at the 95th percentile … for the first time ever.”

He went on. “Beyond the improved satisfaction score, there was a clinical benefit. We are in the business of saving lives, of enhancing heath, of restoring hope. When we touch the hearts of our patients we create a healing relationship that generates a relaxation response, lowers the blood pressure, improves the happy neurotransmitters, reduces pain, and improves outcomes — for both the patient and the caregiver.”

By the way — that CEO was my brother, Dr. Loren Hamel.

For me, the point of his story was simple but profound: empathy is the engine of innovation. That’s why I often worry about just how de-humanized our organizations have become. Listen to the speech of a typical CEO, or scroll through an employee-oriented website, and notice the words that keep cropping up—words like execution, solution, advantage, focus, differentiation and superiority. There’s nothing wrong with these words, but they’re not the ones that inspire human hearts. And that’s a problem—because if you want to innovate, you need to be inspired, your colleagues need to be inspired, and ultimately, your customers need to be inspired.

Writing in the early years of the 20th-century, Max Weber, the famous German sociologist, said this about the modern age:

The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, the disenchantment of the world. The ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life.

A century later, Weber still seems on the mark. We live in a secularized, mechanized and depersonalized world—a fact that strikes me anew each time I find myself scrunched into seat 22B on a dyspeptic airline, or when I’ve been compelled to navigate through an endless phone tree in a quest for “customer service,” or have gotten lost in the maze of a government website that purportedly has a form I need to complete.

It does not have to be this way. These are exactly the sorts of soul-destroying experiences that energize innovators.

In one of his last presentations as Apple’s CEO, Steve Jobs said his company lived at the intersection of “technology” and “liberal arts.” If he had been the CEO of a different company, Jobs might have talked about the intersection of construction and liberal arts, or airlines and liberal arts, or banking and liberal arts, or energy and liberal arts. To Jobs “liberal arts” was another name for “the humanities” — the encapsulation, in poetry, prose, art and music, of what the ancient Greek philosophers called the just, the beautiful and the good.

The best innovations — both socially and economically — come from the pursuit of ideals that are noble and timeless: joy, wisdom, beauty, truth, equality, community, sustainability and, most of all, love. These are the things we live for, and the innovations that really make a difference are the ones that are life-enhancing. And that’s why the heart of innovation is a desire to re-enchant the world.

You Innovate with Your Heart, Not Your Head

I recently got a call from a CEO of a health system that encompasses several hospitals, medical practices, and clinics. Lakeland Health employs about 4,000 associates and takes in nearly $500 million per year. Its facilities are spread across the southwest corner of Michigan — where median income is 70% of the national average and the incidence of chronic diseases is substantially higher than the norm. It’s a challenging environment in which to be a healthcare provider.

The CEO knew I was a fan of passion-fueled innovation and thought he had a story I’d find inspiring, hence the call. A year earlier he had taken up his new post at Lakeland. Shortly thereafter, he had called a meeting to review patient satisfaction scores. U.S. hospitals have to report this data to the federal government, and if they fall below certain thresholds, they pay a penalty in reduced reimbursement rates. Given that, the CEO was distressed to learn that when it came to patient satisfaction, Lakeland was a laggard — with scores between the 25th and 50th percentile. How could this be?

His senior team told him it wasn’t for lack of trying. Lakeland tracked the things that drove patient satisfaction — response times to call lights, pain management, the quality of the food, the effectiveness of patient communication, and so on. By most of these metrics, the care compared well with others in the industry — but this wasn’t showing up in the overall satisfaction scores. Part of the problem, the execs suggested, was the hardship and ill-health that surrounded them. Lakeland drew from a shallow hiring pool and had to treat a disproportionate number of seriously ill and often uninsured patients. Many were frequently readmitted when they failed to follow post-care instructions. Having benchmarked other hospitals, Lakeland’s leaders knew that more favorably located hospitals typically achieved higher patient scores with similar service levels. Conversely, hospitals in comparable locations delivered scores that more or less matched those at Lakeland.

How, the CEO wondered, could Lakeland reinvent the experience of healthcare for its patients? Lakeland had a team of service leaders who were responsible for benchmarking and applying best practices, and there didn’t seem to be a lot more that Lakeland could learn from its peers. Neither could the problem be solved with money. Lakeland didn’t have the cash to make big investments in additional staff or new patient amenities.

After a few weeks of reflection and some personal soul-searching, the CEO thought he had a plan. What would happen, he wondered, if Lakeland’s associates brought their hearts to work, as well as their professional skills?

With this thought in mind, he asked his team to rent cinemas in three cities and sent around a schedule of more than 20 kick-off events. The theme, plastered on posters at each venue, was “Bring Your Heart To Work.” Over the next several weekends, nearly all of Lakeland’s staff showed up at one of the events. The CEOs message was simple, unexpected, and daunting: None of us aspire to work in an organization that frequently lets down its customers. We can and must do better than this. So let’s set a goal of getting to the 90th percentile in 90 days. We can’t scale up much in the way of additional resources, so we’re going to have to be resourceful. We’re going to raise our scores by touching the hearts of our patients — by making sure they know not only how well we care for them, but how much we care about them. We’re going to learn to be more loving. To do that, he said, I want to challenge you to bring your heart to work in new and creative ways.

For a nurse or an x-ray tech with 10 or 20 years of experience, delivering health care is a routine. But for a patient, the experience is anything but. Lakeland’s CEO reminded his associates that a hospital visit is one of the most emotionally charged events any human being can ever experience—something that is remembered for years afterward. Borrowing from research done at Florida Hospital, he characterized a hospital visit as a drama in three acts. First, there’s admission—typically accompanied by pain, fear and anxiety. Next is in-patient care, which often involves alternating bouts of discomfort and boredom. Third is discharge, when out-going patients often feel unprepared or even abandoned. Using associates to play the role of patients, the CEO demonstrated how each stage of the drama offered opportunities to create loving connections with patients — by demonstrating concern and tenderness, and providing consolation and cheer.

The CEO didn’t offer his associates a script or a training program. Instead, he challenged them: “Every time you interact with a patient, tell them who you are, what you’re there to do, and then share a heartfelt why. For example, ‘I’m Tom, I’m here change your dressings, ‘cause we want you home in time for your granddaughter’s wedding.’” The heartfelt why needed to be stated in a way that put the patient’s hopes and fears at the center of the healthcare drama.

Over the next 90 days, the CEO “rounded” 120 times. He showed up in every department, on every shift, in every facility. “How’s it going?” he’d ask. “Have you made any heartfelt connections? If so, tell me about it. If not, let’s role-play right now. Let me be the patient.”

Initially, many of his associates struggled to come up with a “heart-felt” why. Despite all the caring that goes on in health care, making it personal doesn’t always come naturally. It takes practice. “How will we know if we’re succeeding?” was the most frequent question directed at the CEO. His answer: “You’ll see it in a patient’s smile, you’ll here it their voice, you’ll sense it when they take your hand — and ultimately, you’ll feel it in your own heart.”

Over the ensuing months two things became apparent. First, success required that everyone, every day, opened their hearts to those they were caring for. One person with a bad attitude could undo the heartfelt efforts of a dozen colleagues. Not surprisingly, front line employees and their managers started to become less tolerant of colleagues with crappy attitudes. In the end, more than a few of the curmudgeons were asked to leave.

And second, though the focus of the CEO’s initiative wasn’t on call-light response times, pain management, or discharge planning, patient scores on all these conventional metrics started to climb as the heart-to-heart message took hold. The lesson: love someone better, and they’ll extend you grace on all the less important things.

Before long, Lakeland was reverberating with stories about heartfelt connections. So how to thank all of those who were bringing their hearts to work? Here, too, the CEO had a plan. Whenever a patient or a colleague reported a small act of heartfelt service, a senior leader would show up within minutes to personally thank the warm-hearted associate. Surrounded by their nearby co-workers, the leader would retell the story, thank the individual, and pin a heart on their badge. Over the course of a few months, more than 6,000 stories were celebrated across Lakeland, and more than 6,000 hearts were affixed to employee IDs.

Listening to all of this, I asked the CEO to share a typical story:

There was a wicked commotion in the hall, and two security officers suddenly found themselves facing a husband in complete emotional melt down. He had come in with his wife who was desperately ill. After the medical work-up, he was told that his wife was dying of cancer and probably won’t leave the hospital alive. The news struck like a thunderbolt, and he simply lost it. Having been called to the scene, the security guards were ready to phone the police when an associate nurse comes around the corner. Seeing the distraught husband lashing out at everyone around him, she walked up to him and calmly asked, ‘Can I hug you?’ When the man nodded yes, she wrapped her arms around him and for the next 20 she held him as he wept into her uniform. Finally calm, he returned to support his wife and the nurse went on with her duties. She was an LPN, who had never been through any course on conflict management, or de-escalation, but she had heard lots of stories about how to connect with another human being.

“Now,” the CEO continued, “not every story is that dramatic, but many of them will bring a tear to your eye and all of them will put a smile to your face.” Some associates simply found a more thoughtful way to say something to a patient. For example, a receptionist responsible for scheduling follow-up appointments, discovered that she was more likely to get a smile when she switched from saying “the doctor wants you back in two weeks,” to, “the doctor would like to invite you back in two weeks.” That was a tiny change but it made a positive emotional difference.

But, as the CEO constantly reminded his colleagues, little things could also destroy a patient’s emotional equilibrium. He frequently recounted a conversation he’d had with a mother who’d delivered a child at Lakeland several years earlier. The newborn had arrived healthy and happy, but as the mother recounted her birthing experience, her eyes filled with tears. Upon arriving at the hospital, the first person she encountered in the OB unit had failed to look up and greet her with a welcoming smile. When you’re an expectant mother, both hopeful and anxious, you need a bit of reassurance—and it hadn’t been forthcoming. Years later, that disappointed mom still remembered the cold welcome she’d received.

“So,” I asked the CEO, “6,000 stories later, how did this all turn out?” “Well,” he replied, “within 90 days we were at the 95th percentile … for the first time ever.”

He went on. “Beyond the improved satisfaction score, there was a clinical benefit. We are in the business of saving lives, of enhancing heath, of restoring hope. When we touch the hearts of our patients we create a healing relationship that generates a relaxation response, lowers the blood pressure, improves the happy neurotransmitters, reduces pain, and improves outcomes — for both the patient and the caregiver.”

By the way — that CEO was my brother, Dr. Loren Hamel.

For me, the point of his story was simple but profound: empathy is the engine of innovation. That’s why I often worry about just how de-humanized our organizations have become. Listen to the speech of a typical CEO, or scroll through an employee-oriented website, and notice the words that keep cropping up—words like execution, solution, advantage, focus, differentiation and superiority. There’s nothing wrong with these words, but they’re not the ones that inspire human hearts. And that’s a problem—because if you want to innovate, you need to be inspired, your colleagues need to be inspired, and ultimately, your customers need to be inspired.

Writing in the early years of the 20th-century, Max Weber, the famous German sociologist, said this about the modern age:

The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, the disenchantment of the world. The ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life.

A century later, Weber still seems on the mark. We live in a secularized, mechanized and depersonalized world—a fact that strikes me anew each time I find myself scrunched into seat 22B on a dyspeptic airline, or when I’ve been compelled to navigate through an endless phone tree in a quest for “customer service,” or have gotten lost in the maze of a government website that purportedly has a form I need to complete.

It does not have to be this way. These are exactly the sorts of soul-destroying experiences that energize innovators.

In one of his last presentations as Apple’s CEO, Steve Jobs said his company lived at the intersection of “technology” and “liberal arts.” If he had been the CEO of a different company, Jobs might have talked about the intersection of construction and liberal arts, or airlines and liberal arts, or banking and liberal arts, or energy and liberal arts. To Jobs “liberal arts” was another name for “the humanities” — the encapsulation, in poetry, prose, art and music, of what the ancient Greek philosophers called the just, the beautiful and the good.

The best innovations — both socially and economically — come from the pursuit of ideals that are noble and timeless: joy, wisdom, beauty, truth, equality, community, sustainability and, most of all, love. These are the things we live for, and the innovations that really make a difference are the ones that are life-enhancing. And that’s why the heart of innovation is a desire to re-enchant the world.

This Airbus Makes Pilots Smarter

Sponsor content – insight from GE.

At first glance, Air Asia’s fleet of Airbus A320 planes look like any other passenger aircraft. But look under the hood and you will find an array of sensors and proprietary technology developed by GE that make their pilots smarter.

That’s because the systems gather performance, weather, flight path and other data and feed it over the Industrial Internet to the cloud, so that it can be crunched by software and analytical engines built and operated by GE Aviation’s Flight Efficiency Services unit. The system looks for hidden patterns and saving opportunities, and allows the airline to cut its annual fuel bill by more than 1 percent. Doesn’t seem like much? Consider that it’s on average about 550 pounds of jet fuel – the equivalent of 11 packed suitcases – per hour of flight.

Pilots and airline managers see the results on a dashboard and use it to make better informed decisions about how much fuel they need and which path they are going to take. There are dozens of other airlines around the world already using the system, including Air New Zealand, China Airlines, WestJet, and EVA Air.

But the smarts go beyond fuel savings. GE is also working with Air Asia and the Department of Civil Aviation (the regional equivalent of the FAA) to roll out a GPS-based flight path program at 15 Malaysian airports, and another eight in Thailand and Indonesia. The goal is to improve their efficiency and possibly increase capacity.

While GPS does not sound revolutionary in other contexts, keep in mind that most aircraft still use radio beacons to determine their position. The new system, called Required Navigation Performance (RNP), was first designed by Alaska Airlines pilot Steve Fulton after going through many sweat-soaked night landings at the mountain-rimmed airport in Juneau, AK. It was further developed by GE Aviation.

“The inspiration was both frustration and concern,” Fulton said. “As pilots in southeast Alaska, we were regularly operating in difficult weather conditions with limited navigation aids. We understood that there was very little margin for error. We had training, experience, and the best in that generation of ground-based navigation equipment and the associated aircraft instrumentation. But still, even with all of that, there were times when a pilot could be put in a very tight spot.”

The system has since helped open up airports in the Himalayas, mountainous southern New Zealand, hilly downtown Rio de Janeiro and elsewhere around the world.

Subscribe to GE Reports and stay tuned for more aviation coverage from the Farnborough Airshow.

See how GE can give you the edge: gesoftware.com/solutions/aviation

What Happens When an Interim CEO Takes Over?

Twitter chief Dick Costolo is leaving his post in two weeks, and co-founder and chairman Jack Dorsey will be taking the reins as interim CEO. It’s not the company’s first leadership shakeup, but unlike previous ones, it’s a response to sluggish performance, rather than to rapid growth.

So what happens now? In 2007, researchers at the University of Virginia explored the interim CEO phenomenon, and their findings provide context for how Twitter will fare under Dorsey.

Interim CEOs are quite common. Seventeen percent of successions at publicly traded firms between 1996 and 1998 included the appointment of an interim CEO for at least 45 days.

They don’t stay long. The vast majority of interim CEOs stay for at least a quarter (92%), but just a third of them stay on for more than a year.

Performance suffers. Firms that appoint an interim CEO as part of their succession process have lower return on assets and are more likely to fail than those that appoint a new permanent CEO right away.

But chairmen do better as interims. The majority of interim appointments are insiders, and 42% are the current chairman (like Dorsey). The researchers found that firms that appointed the chairman as interim CEO were less likely to fail and had better return on assets than firms that appointed a non-chairman.

The search for a new CEO may be less biased. One of the main benefits of an interim CEO, according to the researchers, is that it makes it easier to search for a new chief executive unencumbered by the interests and biases of the old CEO. Sitting executives can exert influence on the search for a replacement, often in order to preserve their own legacy.

Interim CEOs don’t rewrite the strategy. Though interim appointments may be more common in cases where the shareholders disagree with the sitting executive on vision, interim CEOs tend not to take on big strategic reorientations during their tenure. The researchers interviewed three former interim CEOs and conclude that they focus their “attention on short-term, tactical crisis management.”

Of course, Twitter’s transition isn’t necessarily typical. In the researchers’ sample, interims were more likely to be older than the executives they replaced. Dorsey is 13 years Costolo’s junior. Dorsey is also Twitter’s former CEO, and has also reportedly coveted a return to the top job. In an interview Thursday, he said he’s focused on his role as interim CEO, but didn’t rule out taking the position full-time. Finally, Dorsey is also the CEO of Square and will continue in that role simultaneously.

Research suggests that Dorsey’s status as co-founder and chairman leaves him relatively well positioned to navigate the transition. But perhaps the biggest clue as to whether he’s truly taking an interim role vs. auditioning for the job will be the moves he makes in the next few months. If they’re mostly tactical, that could be a sign the company is waiting for a new CEO to adjust its path. If he starts making major changes to strategy and vision, that might mean he’ll be around for a while.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers