Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1287

June 8, 2015

Ease the Pain of Returning to Work After Time Off

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

As much as we all need vacations, the day or week after a vacation often leaves us wondering whether the joy of vacation is worth the pain of returning to work. Between the email backlog, the pain of readjustment, and the fight to get back into your work clothes after two weeks of eating all the biscuits in Oregon (strictly hypothetically), you may feel like you need another vacation just to recover from the stress of getting back into a work groove. But a simple set of digital tools and practices can make it easier to get your work mojo back—particularly if you lay the groundwork before your vacation.

Before your vacation

Triage and queue your tasks. Use the week before your annual or semi-annual vacation to do a ruthless cull of your task list: now is the time to move all those hazy or long-neglected to-dos out of your main task list and into a “someday/maybe/never” list.

Make a short priority list of what you actually need or want to tackle in the week or two after vacation, and annotate that list with where you’ll start with each one. (I like to put that list in a digital notebook like Evernote, but you could put it on Google Drive or even a Word document.)

Set up timed alerts that will remind you at a specific date and time for any task that must get addressed that first week back, in case it takes you a day or two to feel up to looking at your task list.

Along with your list of key priorities, make a separate list of fun or easy tasks you can tackle in week 1, so you’ll have some fun stuff you can knock off while you’re waiting for your work brain to turn back on.

Park on a downhill slope. A common bit of wisdom on writing is to “park on a downhill slope”: wrap up your day’s writing by leaving yourself a note about where you intend to pick up the next day. It’s actually easier to ease yourself into the next step of a project that’s already underway than to start from a blank page, so be sure to “park” at least a couple of projects on a downhill slope by writing yourself a note about where you plan to pick up again on your return.

If you’re choosing which projects to wrap up before vacation and which to leave for completion upon your return, leave the most enjoyable or interesting challenges unfinished—that way you’ll have something enjoyable to tackle when you get back. Put together a folder of emails or a project-related notebook in Evernote so you’ll be able to get underway as easily as possible.

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work

Managing Yourself Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Lower expectations for your return. Give yourself a little margin for getting back into the flow of online communications by setting expectations in your pre-vacation messages. When you set up your email vacation message, tell people you’ll be back on email a couple of days after you’re returning from vacation; my vacation message always tells people that while I’ll try to work my way through the backlog, I can’t guarantee it, so they should email again after X date if they need a response.

Make sure you also give yourself a little wiggle room for your return to any social networks you participate in regularly; whether you’re pre-scheduling social media updates (with a tool like HootSuite or Buffer) for your vacation, or simply telling people that you’re going dark while you’re on vacation, allow yourself an extra 3 to 7 days before you plan on resuming your usual social network posting schedule.

Plan for your first week back. Block off significant chunks of time in your calendar for the week after you get back so that you don’t return to a week of back-to-back meetings. Just as important, schedule a couple of lunch or coffee dates with people you’ll actually enjoy seeing, so that you have something to look forward to.

When you return

Stay in stealth mode. Leave your email responder on for an extra day or two, so your colleagues and clients don’t expect an instant response. In the same vein, stay off the intra-office chat network, and either avoid other in-house and external social networks (like Slack, Yammer, Twitter, and LinkedIn) or limit your participation to one or two short windows a day. Leave Skype and other chat systems in “do not disturb” mode, and the ringer off on your phone. The one exception: consider choosing one channel (like Google Chat or Facebook Messenger) that you’ll use to reconnect with family, friends and maybe one or two favorite colleagues.

Make work fun. Put your first week back to good use by doing neglected tasks you actually enjoy. I’m a productivity nerd, so (surprise!) my idea of fun is cleaning up my tech setup and adding to or improving the productivity tools in my toolkit. (The Apple app store always enjoys a little revenue bump the week I come back from vacation.)

Use technology to distract yourself. I know, I know: digital distraction is unhealthy. But here’s one time when it can really work for you, by taking your mind off the suffering of being back at work. When you’re working alone at your desk, use a new Spotify playlist to entertain yourself while you catch up on mundane tasks. When you go to a meeting (especially one you’re dreading) leave your phone on, and allow yourself the luxury of intermittently peeking at Twitter, Flipboard, or whatever else will keep you from standing up and doing a Don Draper-style walkout.

And if you find yourself desperate to just chuck it all, put a date in your calendar for three to six weeks from now with a timed alert, saying “consider quitting my job”—and then put it out of your mind until the alert pops up. The odds are good that you’ll be back in the swing of things by then, and if not…well, you probably should start thinking about your exit plan.

Even if you experience some residual vacation hangover, remember that’s not necessarily a bad thing: it’s more likely to be a sign that you’ve done a really great job of unplugging from work than a sign that you’ve returned to the wrong job. Use your tech setup to minimize the pain of the transition back to work, and you’ll maximize the restorative effects of the vacation itself.

Improve Your Ability to Learn

On the surface, John looked like the perfect up-and-coming executive to lead BFC’s Asia expansion plans. He went to an Ivy League B-school. His track record was flawless. Every goal or objective the organization had ever put in front of him, he’d crushed without breaking a sweat.

But something broke when John went to Asia. John struggled with the ambiguity, and he didn’t take prudent risks. He quickly dismissed several key opportunities to reach out for feedback and guidance from leadership. It became clear that John had succeeded in the past by doing what he knew and operating rather conservatively within his domain. It also became clear that the company was going to massively miss the promises it had made to the Board and the Street if John remained in the role.

With a heavy heart, BFC’s CEO removed his promising protégé from the role and redeployed him back in the US. He decided he had no choice but to put a different kind of leader in the role – Alex.

While talented, Alex had come to be known behind closed doors by the moniker “DTM” – difficult to manage. He marched to the beat of his own drummer, and he wasn’t afraid to challenge the status quo. He loved a challenge, and he was comfortable taking risks. It turned out to be the best move the CEO ever made.

No stranger to ambiguity, Alex was flexible in formulating his strategy and sought feedback from the people around him. He made a risky move at the beginning that backfired on him. But as a result, he learned what not to do and recalibrated his approach. That was the key to success. His tendency to buck the established BFC way of doing things was exactly what was required for the company to successfully flex its approach and win in the new territory.

What Alex’s success exemplifies is the importance of “learning agility”: a set of qualities and attributes that allow an individual’s to stay flexible, grow from mistakes, and rise to a diverse array of challenges. It’s easy to assume that those qualities would be highly prized in any business environment. Flexibility, adaptability and resilience are qualities of leadership that any organization ought to value.

But in practice, this is not the case. As a rule, organizations have favored other qualities and attributes – in particular, those that are easy to measure, and those that allow an employee’s development to be tracked in the form of steady, linear progress through a set of well-defined roles and business structures.

The Link Between Emotional Intelligence and Learning Agility

How does emotional intelligence connect to learning agility? In their groundbreaking 1990 article, researchers Peter Salovey and John D. Meyer defined it as “the subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.” Learning agility is central to the first part of the task – the ability to monitor and manage one’s own emotions. And since that leads naturally to an increased ability to listen, it is reasonable to suggest that learning-agile people might be more skillful at monitoring and responding to others’ emotions as well. The link between learning agility and sensitivity to others’ emotions has not yet been fully documented – but making the connection might prove to be a fruitful area for further research.

Learning agility, by contrast, has until recently been hard to measure and hard to define. It depends on related qualities such as emotional intelligence that are only just beginning to really be valued. It also relates to behaviors – such as the ability to recover from and capitalize on failure – that some managers would prefer not to think about.

The Pillars of Learning Agility

According to the researchers at Teachers College, Columbia University, and the Center for Creative Leadership, learning agility is defined as follows:

Learning agility is a mind-set and corresponding collection of practices that allow leaders to continually develop, grow and utilize new strategies that will equip them for the increasingly complex problems they face in their organizations.

Learning-agile individuals are “continually able to jettison skills, perspectives and ideas that are no longer relevant, and learn new ones that are,” the researchers say.

The research identified four behaviors that enable learning agility and one that derails it.

The learning-agility “enablers” are:

Innovating: This involves questioning the status quo and challenging long-held assumptions with the goal of discovering new and unique ways of doing things. Innovating requires new experiences, which provide perspective and a bigger knowledge base. Learning-agile individuals generate new ideas through their ability to view issues from multiple angles.

Performing: Learning from experience occurs most often when overcoming an unfamiliar challenge. But in order to learn from such challenges, the individual must remain present and engaged, handle the stress brought on by ambiguity and adapt quickly in order to perform. This requires observation and listening skills, and the ability to process data quickly. Learning-agile people pick up new skills quickly and perform them better than less agile colleagues.

Reflecting: Having new experiences does not guarantee that you will learn from them. Learning-agile people look for feedback and eagerly process information to better understand their own assumptions and behavior. As a result they are insightful about themselves, others and problems. In fact, in prior studies, Green Peak Partners discovered that strong self-awareness was the single highest predictor of success across C-suite roles.

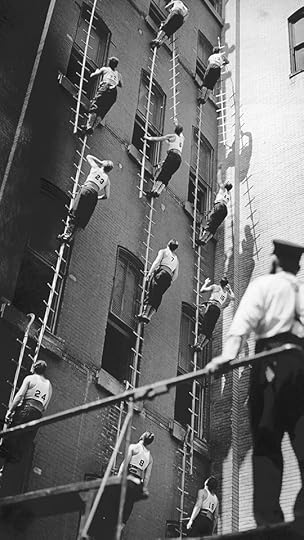

Risking: Learning-agile people are pioneers – they venture into unknown territory and put themselves “out there” to try new things. They take “progressive risk” – not thrill-seeking, but risk that leads to opportunity. They volunteer for jobs and roles where success is not guaranteed, where failure is a possibility. They stretch themselves outside their comfort zones in a continuous cycle of learning and confidence-building that ultimately leads to success.

The learning-agility “derailer” is:

Defending: Being open to experience is fundamental to learning. Individuals who remain closed or defensive when challenged or given critical feedback tend to be low in learning agility. By contrast, high learning-agile individuals seek feedback, process it and adapt based on their newfound understanding of themselves, situations and problems.

How do these five facets translate into behavior, performance and results at work? The researchers found that learning-agile individuals are notably:

More extroverted: They are more sociable, more active and more likely to take charge.

More focused: They continually refine and polish their thinking and their work. They are more organized, more driven and more methodical.

More original: They are more likely to create new plans and ideas, seek complexity and readily accept change and innovation.

More resilient: They are more “at ease,” calm and optimistic. They rebound more quickly from stressful events.

Less accommodating: They are more likely to challenge others, welcome engagement, and express their opinions.

The research also shows that while many individuals can model some aspects of these behaviors, learning-agile individuals stand out in particular for their resilience, calm, and ability to remain at ease. It’s not just that they are willing to put themselves into challenging situations; it’s that they’re able to cope with the stress of these challenges and thus manage them more effectively.

The “derailer” – defensiveness – also has an impact on performance, of leaders in particular. When the researchers reviewed 360-degree evaluations, they found that leaders who ranked high on the “defending” scale were considered less effective. By contrast, peers and direct reports rated more highly the leaders who ranked high on the “reflecting” scale.

Researchers at Columbia University and the Center for Creative Leadership collaborated to develop an objective test for learning agility, called the Learning Agility Assessment Inventory (LAAI). It’s a 42-item survey that measures learning-agile behavior by asking individuals about how they respond to challenging situations, then scoring the answers against the four enablers – innovating, performing, reflecting and risking – and reverse-scoring the derailer, defending. In developing the test, researchers compared the scores to a 360-degree assessment and to another established personality test, the Workplace Big Five Profile.

We then administered this test to over 100 executives –mostly private-equity backed C-suite leaders — that we had previously assessed in a rigorous half-day structured interview. In a 2010 study with Cornell University, we showed that our assessment grades predict performance, as measured not only by revenue and EBITDA but also by boss ratings (often issued by the Board). The more recent study extended that research by showing that those who out-performed in our assessments also scored higher on the LAAI.

Taken together, the two studies demonstrate that high learning-agile individuals are also high performers.

Cultivating Your Own Learning Agility – and Coaching It in Others

One of the best ways to coach for learning agility – or for that matter, any desirable set of behaviors – is to recognize and develop it in yourself. Becoming more learning-agile will help you cope with the turbulence of the workplace. And it will make you more aware of how to bring out the potential in your learning-agile people.

Among the ways to cultivate learning agility in yourself are:

Innovating. Seek out new solutions. Repeatedly ask yourself, “What else?” “What are 10 more ways I could approach this?” “What are several radical things I could try here?” It doesn’t mean you do all of these things, but you explore them before proceeding.

Performing. Seek to identify patterns in complex situations. Find the similarities between current and past projects. Cultivate calm through meditation and other techniques. Enhance your listening skills – listen instead of simply (and immediately) reacting.

Reflecting. Engage in “counterfactual thinking” – explore “what-ifs” and alternative histories for projects you’ve been involved in. Regularly seek out real input. Ask, “What are three or four things I or we could have done better here?” Frame the question in specific terms, instead of simply asking, “Do you think I should have done anything differently?” But make sure the questions are still open-ended – that will encourage colleagues to speak up.

Risking. Look for “stretch assignments,” where the probability of success isn’t a given.

Avoid defending. Acknowledge your failures (perhaps from those stretch assignments) and capture the lessons you’ve learned from them.

Reaping the benefits of learning agility takes effort and commitment. That said, the first step is simple: Recognize its attributes and that it is an asset that you need to cultivate. After that comes the hard work – creating accurate screening methods, putting the systems in place to identify learning-agile individuals and creating career paths and management techniques to get the most out of them.

But once you have started that process, you will begin to realize the benefit – an organization that is more flexible, more adaptable, better able to respond to business volatility and therefore more competitive in the face of unprecedented challenges. The results might even be revolutionary.

A Tournament Pits Strategists Against Each Other to See What Works

It is hard to study competitive strategy. As a result, we don’t know much about what actually works.

We don’t lack anecdotes and stories. A business goes under, we get an instant autopsy. A business takes off, we get an instant reverse-engineered recipe. That’s entertaining but not rigorous.

There’s plenty of evidence about what’s profitable to have. For example, The PIMS Program (a major observational study on thousands of businesses; I worked there for 15 years) showed that it’s profitable to have low investment intensity, high market share, positive differentiation, and more. There’s much less evidence about how businesses can get what’s profitable to have. Everyone wants to gain market share but not everyone can. In every market there’s always, always exactly 100% market share, and if you gain someone must lose.

It’d be helpful to run experiments. Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a double-blind randomized controlled trial in business. What placebo would businesses take? What businesses would sign up to take it?

I’ve been working on a different approach. If we can’t experiment on real-life strategists running real-life businesses, how about if we experiment on real-life strategists running simulated businesses? We can find out how strategically people think and how well they perform.

I’ve conducted the Top Pricer Tournament for several years. Over 650 people have entered the Tournament. They’re a mix of managers, consultants, academics, and students, from the United States and other countries. It’s too soon to report definitive results but some tidbits are ready.

The most intriguing finding: so far, no human has found the best possible Tournament strategies. We know that because the computer running the Tournament has found them. When I saw them, they made slap-my-forehead sense. Computer teaches human.

The Tournament is based on three fictitious industries: Ailing, Fast Growth, and Mature. Each industry has three competitors that start out identical in every way (cost structure, product line, performance, etc.). The Tournament takes into account price sensitivities and elasticities, customer loyalty, market growth, costs, and competitive response. Tournament entrants see the relevant information before they devise their strategies. The time horizon is three years and entrants devise strategies that make quarterly moves. Price is the only lever they can pull.

I know that sounds like a simple problem. It isn’t. The number of simulations the Tournament runs and analyzes, with the current 653 entrants, is just over 139 million per industry. The number of possible outcomes in each industry is 3,201,872,665,419. I am not making that up.

What I’ve observed from the data:

People selected different strategies in the three industries. Only 11 people out of 653 used the same strategy in all three, and only 35 used the same strategy in two. That suggests people took the Tournament seriously.

People specified their goals — profitability, market share, or a combination— differently in the three industries. Market share was heavily favored in Fast Growth, and profitability in the others. That matches conventional wisdom and again suggests serious entries.

Some people selected their strategies saying they wanted to achieve high profits without regard to market share. Others adopted precisely the same strategies saying they wanted to achieve high market share without regard to profits. That suggests people find it hard to predict the outcome of a strategy even in this seemingly simple problem.

Everyone chose the strategies he or she thought best. If they thought a different strategy would be better, they’d have chosen that. However, the range of outcomes their strategies produce is very wide. That suggests people find it hard to tell the difference between a good strategy — i.e., one that will get them what they want — and a bad strategy.

So far, demographics do not predict whose strategies perform well. Females and males performed equally well. So did young and old, introverts and extroverts, and more.

In my experience running business war games and real-time strategy simulations, people tend to think move by move. They speak of it as fine-tuning their strategies, but I think it’s more accurate to say they react to perceived events. I suspect that that’s a reason why people had such variation in their Tournament results: many are used to reacting, not to strategizing.

Until we know what works – or perhaps until we’re more comfortable and skilled at letting computers test and appraise strategies for us, but that’s a different discussion – human strategists must continue to react, guess, and gamble with competitive strategy. No experiment and no computer will find a (legal) strategy guaranteed to work. But we don’t need perfection. It takes only a few percentage points to separate the casino from the gambler.

If you’d like to enter the Top Pricer Tournament, which is free and confidential, please write to us at .

June 5, 2015

5 Rules for a Vacation that’s Truly Worth It

Photo by Jacob Walti

“A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play; his labor and his leisure; his mind and his body; his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always appears to be doing both.”

I love this quote from L. P. Jacks. It describes some of the most inspiring, happy, and successful professionals I know. The main message is clear: find a job that you love—one that allows you to be your best self—and it won’t feel like work at all. The corollary is also important, however: we must approach our vacations with the same tenacity as we do our vocations, and use them to come back to the office better than before.

Consider my friend John, the former chief executive and chairman of a top professional services firm, who is now active in several remarkable social initiatives. He sees holidays as a way to clear and sharpen his mind and has, for the past 25 years, organized annual hiking trips with his wife and three other couples. They walk for about a week in stunning mountains, national parks or nature preserves, pairing off differently each day so everyone gets a chance to chat. Before retiring from the CEO role, he would try to take these breaks just before his global partners’ meetings because he found that his ideas, initiatives, and even speeches would become much more focused, rich, clear and powerful as a result—even though he didn’t spend any time actively working on them!

You and Your Team

Vacation

Make the most of your time away.

For Richard, a respected academic and world authority on leadership, vacations are also serious stuff. He and his wife consciously vary the way they spend their time off. Once or twice a year they take “learning holidays” to places they don’t know well. They research all the must-see sights and must-visit restaurants in their chosen destination, meticulously plan their itinerary and often book a guide and driver if neither of them speak the local language. When there, they truly explore and spend a lot of time talking to the natives. They supplement these busy holidays with two kinds of relaxation: one annual stay at a quiet and interesting boutique beach hotel (no family-friendly places), to which they bring only books, sun screen and snorkeling gear, as well as frequent visits to their own beach house for “chill-out time”—no guests or work, just reflection and gardening.

What can we learn about how to take leisure time from these true masters in the art of living?

Move and exercise. Evolutionary science tells us that our fancy brains developed not while we were lounging but while we were working out. Our ancestors moved around all the time. And we should use our holidays to do the same—especially those of us in jobs that keep us at meeting tables or desks all day.

Find peaceful, beautiful surroundings. Nature not only helps you listen to your inner voices; it can also inspire new purpose and passions. My wife María and I were walking through the solemnly beautiful Júcar Canyon in Castilla-La Mancha, when we decided to move from Madrid to Buenos Aires so I could make the most important and successful job change of my life.

Meet different, interesting people. In one of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, there is a to-do list of 15 tasks. At least eight involve consultations with other people and two focus on other people’s books. The world’s most productive people are deeply curious and collaborative and constantly seek out new acquaintances and allies – even when they’re on vacation.

Be willing to invest. Many of us are biased toward tangible luxuries. We spend more on houses, cars, clothes, and other things, which very soon lose their initial attraction and generate all sorts of worries and maintenance needs, than we do on experiences, which, according to research, offer more long-term satisfaction, providing not only pleasure but also a chance to learn and grow. Quality vacations are one of the highest-return investments you can make.

Plan properly. Never leave your holidays to chance. Seamless air travel, nice accommodations, guaranteed restaurant and tour bookings—all of these will make your time off more productive and enjoyable. Besides, the preparation itself can be fun. Imagine everything you might possibly do, then pick the places and activities which will give you best opportunities for renewal and reinvention and let you create the most unforgettable memories.

The Internet of Things Is Changing How We Manage Customer Relationships

Steven Moore

Just as it’s hard to remember what life was like before the iPhone, it can be hard to remember business before there was CRM software — back when you still had to explain that it stood for “customer relationship management.” Today, CRM pervades the way many companies track and measure how they interact with other organizations, across many departments: marketing, sales, customer service, support, and others. CRM made it possible to determine precisely who responded to a specific marketing campaign and then who became a paying customer, which customer called the most for support, and so on. It gave companies some overall measure of revenue compared with marketing spend — something described in this 2007 article in The New York Times.

But now that Big Data and the Internet of Things have come along, we can go beyond the transaction to every little detail of the customer’s actual experience. You can know when customers enter your store, how long they are there, what products they look at, and for how long. When they buy something, you can know how long that item had been on the shelf and whether that shelf is in an area of things that usually sell fast or slowly. And then you can view that data by shoppers’ age, gender, average spend, brand loyalty, and so on. Today, this sort of thing is possible not just for online experiences; it’s possible for physical experiences as well — and not just retail shopping. This vivid view of the end-to-end experiences is rapidly changing the way people think about, measure, and manage their customer relationships.

Consider Waze, a wildly popular crowdsourced driving application that people use for real-time traffic information, warnings about hidden police, and turn-by-turn guidance about how to get around congestion. It only works because users give up their location information (on their mobile device) in exchange for information that will enhance their own experiences. So each mobile device pushes real time information into the main information hub, which processes all of the data and then pushes personalized messages back to every machine that is connected. It works incredibly well.

Another offering that taps the power of the Internet of Things and Big Data (and in whose development I was directly involved) is Disney’s MyMagic+. Disney customers (aka “guests”) wear a MagicBand bracelet that allows Disney to know where they are at all times. Guests use an application called My Disney Experience to plan all of their bookable and non-bookable activities: dining, rides, attending parades, and so on. Then, Disney can use the tracking information and send them personalized messages via their smartphones about things like where they might find a cold drink if they are ahead of schedule, what they might skip if they are running behind, and, if they are heading toward a congested area, a better route to take.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

In addition, guests can use the band to get into their hotel rooms in their resort as well as the park (by tapping a Mickey Mouse icon instead of going through a turnstile). This has greatly increased the rate at which guests can enter the park.

Customers can also tap the MagicBand to pay for things, and scanners read it during rides. This means that after you finish a roller-coaster ride, you no longer need to go and find your picture and write down some 10-digit number if you want to buy a copy; all of those images show up on your My Disney Experience page so you can buy them at any time.

With every passing day there are more examples of Internet of Things adoption. And with every passing adoption, what people will accept (giving up things like their location information) and what they expect (“If Waze can help me with my driving, why can’t my grocery store tell me the fastest way to get through my grocery list?”) both change. As this intersection of what people will accept and what they expect evolves, the kinds of experiences that can be captured in the form of new big data evolves with it.

Now you can have visibility into everything. Not only can you tell that Customer A (who has a shopping app) went into a Lord & Taylor store to buy an expensive pair of shoes (which you could know with CRM). In addition, you can know how long they were in the store, where they walked, and whether they lingered or went straight to the shoe department and bought the shoes. Then, you can compare that visit to every visit to that store that Customer A has had (since getting the app), and you can at least infer what is most valuable to her. If she is always a get-in, get-out kind of shopper, speed of service may be her #1 thing. If she spends a great deal of time shopping, maybe price or product selection is her thing. If she buys a lot at the store, maybe she wants some form of recognition for her loyalty (whether it’s points or just a “welcome back”). If you compare online experiences with in-store experiences and weekend vs. weekday behaviors, your picture of the customer becomes three-dimensional very fast.

As exciting as it can be to talk about this and to see that it is happening right now in broad daylight, talking about how to assess customer experiences and how to engage customers differently when they have this information gets complicated quickly. The important thing is to acknowledge that the measurements of yesterday may need an overhaul, and to understand where your customers are on the acceptance-expectation path so you can try to stay with, if not get ahead of, them. An increasingly common method for getting a handle on this is documenting the customer (and employee) experience journeys. What that means is examining high level areas such as:

Discover. How do they discover that they could have this experience?

Plan/Enroll. Do they need to sign up or enroll to have the experience?

Arrive. When do they begin to have the experience?

Engage. What are they doing while they are having the experience? What is their top priority (e.g., speed of service, best price, product selection)?

Complete. How do they choose to end their experience (e.g., when they are ready to leave that Lord & Taylor store)? Not all experiences start and end with entering a physical location, but that is a common, simple, and familiar experience boundary.

Reflect. After the experience, do they visit social-media sites to comment on their experience, do they look at a loyalty-program site to ensure they got the points or credits that they expected?

Once the experience steps have been documented for the experience that occurred today, be specific about how you will make it different in the future because of the additional information that you have. Where will you and won’t you use that additional information? Will you greet them by name when they enter your store? Will you offer them what they had last time? Will you instruct your staff to leave them alone so they can feel anonymous? Many things are possible with all of this new experience information. Using it in a way that is aligned with your brand, improves the customer experience, and makes things easier for your staff are the things to prioritize and try.

Your plan probably won’t be perfect, and you may need to make some new hires, or get some outside help from people who have done these Big Data and Internet of Things projects. But whatever you do, don’t underestimate the impact of acting on something seemingly minute. The right incremental changes can truly transform the way people experience your organization. So even if something seems trivial, try it and see how it goes. You might find that you had underestimated just how powerful a small change can be.

No One Can Think Outside the Box

Taxi services think inside a box. So did Blockbuster. So does Microsoft.

But here’s the thing. Uber, Netflix, and Apple also think inside boxes. So do you. So do I.

A box is a frame, a paradigm, a habit, a perspective, a silo, a self-imposed set of limits; a box is context and interpretation. We cannot think outside boxes. We can, though, choose our boxes. We can even switch from one box to another to another.

Boxes get dangerous when they get obvious, like oft-told stories that harden into cultural truth. Letting a box rust shut is a blunder not of intention but of inattention.

Boxes are invisible until we look for them. Let’s look.

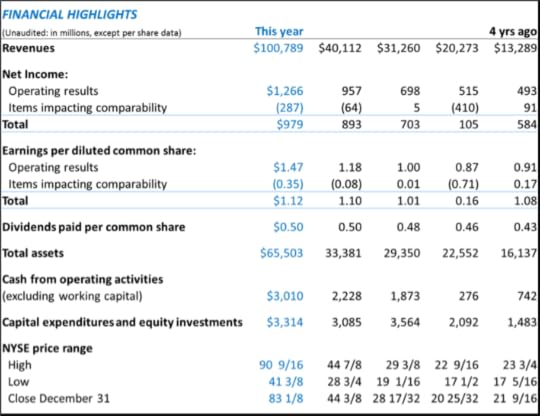

Figure 1 presents a real company as shown by its annual report. If you’d bought its stock at 21 9/16, you’d have almost quadrupled your money over the subsequent four years. My question for you: would you buy its shares now?

I’ve used the financial-history exercise in my corporate workshops on strategic thinking and in my classroom. I’ve observed that most people dive immediately into the numbers when I ask them whether they’d invest now. A cautious or suspicious few ask due-diligence questions.

Almost no one questions whether those numbers are appropriate for the decision at hand. They silently adopt the supreme box of the corporate world: the financial-accounting view of the company.

I am not saying that a neat tabular arrangement of money over time is inherently right or wrong. I am saying that it is unwise not to notice what analytic framework you choose to answer a question. Did the handy financial-accounting box keep you from noticing that I’d said nothing about the company’s market position, customer preferences, cost structure, and much more? Did a box stop you from refusing to make an investment decision based solely on the financials?

The company is Enron.

The numbers are from its 2000 annual report, a year before it went bankrupt. Does it matter that it was Enron in the exercise? Not a bit. Whatever the company, the numbers and insights inside one box don’t include the numbers and insights from other boxes.

Agility is much in demand. It doesn’t, or at least shouldn’t, merely mean hair-trigger reflexes. Something happened! Do something, quickly!

Agility means doing something smart, quickly. Here are some get-smart-fast methods I’ve learned while war-gaming and simulating Fortune 500 companies. Each of them involves noticing and switching boxes.

Role-play your competition. Prior to a war game, a company believed its planned price cut would work because its competitor couldn’t afford to match it. It changed its mind when its own people, role-playing the competitor, discovered they couldn’t afford not to match the price cut.

Reverse the labels. You can get an extra kick out of SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. When you’ve completed the lists in each category, reverse the labels. See how thinking grows when strengths become weaknesses (and vice versa) and opportunities become threats (and vice versa).

Resist the urge to converge. A company faced several competitors, restive customers, and government regulations in flux. In a 15-minute exercise we determined there were millions of possible scenarios ahead. That dispelled the notion that they could plan for “the” future.

Assume the presence of intelligent life. People often say “they were stupid to do X” when they see X lead to an unhappy outcome. I ask “why would a smart person do X?” I don’t mean that the person was necessarily smart, or that I agree with them; but it’s dangerous to assume bad outcomes meant that decision-makers were stupid. They might know something you don’t.

Thinking that you must act outside the box is also a box. My colleagues and I worked with a Fortune Global 50 company that had come up with a revolutionary change to its product. The change had passed every internal review. The company wanted one last test, a quantitative (simulation-based) war game, before they launched the revolution.

The simulation showed their revolution would work beautifully… as long as competitors didn’t mind. (Notice that such a possibility wouldn’t occur to companies in a Figure 1 box or even in a customer-research box. That’s why it’d passed the internal reviews.) Spending a little time thinking inside competitors’ boxes revealed that the revolution would trigger the equivalent of nuclear war. The company canceled the revolution.

So, don’t ask how you can think outside the box. Ask how many boxes you can think inside. Then, dive in. The revelations are fine.

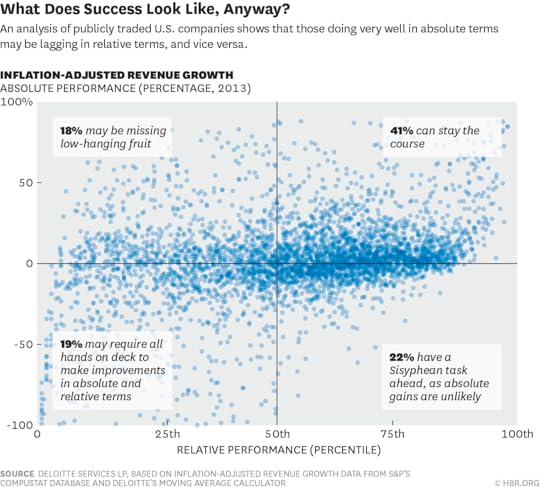

Performance Can’t Be Measured by Company Growth Alone

Is your company focused on the right priorities? How do you know?

Companies measure performance not only to learn where they’ve been, but also to figure out where they’re going. Since scarce resources often require setting priorities — doing more of one thing at the expense of doing less of another — knowing where improvement efforts are going to yield the greatest returns is critical to getting the most out of a given investment.

For example, when it comes to driving shareholder value, there are two fundamental components of cash flow: profitability and growth. Should you invest equally in both? If not, which of these two should get the nod? Should you focus on getting costs under control or expanding into a new geography? Should you invest in differentiation to command premium prices or work to secure more customers, even at lower margins?

Without a rigorous understanding of how you’re doing on each dimension, you risk focusing on the wrong things: You can end up trying to improve a measure that is already at the upper bound of what is reasonable or ignoring the low-hanging fruit that could make a real difference.

When setting priorities it is helpful to distinguish between absolute and relative performance. Absolute performance sets the minimum requirements — are you in the red or black, are you growing or contracting? Relative performance, expressed in percentile rankings, tells you where you have the most room for improvement and sets an upper bound on what is reasonable for you, given how well you’re already performing in comparison with other companies. (For more on assessing relative performance, see our earlier online article.)

How well or poorly companies are doing on absolute and relative performance says a great deal about where they are likeliest to achieve significant improvement.

Consider this chart, an analysis of the growth performance of U.S.-based, publicly traded companies. Start with companies in the upper left, those with positive absolute growth rates. Many appear to be doing quite well; some even show double-digit growth. The natural conclusion might be that these companies have no room left for improvement. Based on absolute figures alone, priorities for performance improvement are likely to be elsewhere; on the growth front, they’ve got it covered.

Yet when we augment the performance picture with relative standings, it becomes evident that many of these companies may still have significant opportunities for improvement. With growth rates that are below the median for their circumstances, these companies may have a great deal of growth headroom, if only they could see it. Their strong absolute results may be blinding them to the significant upside.

Note: Relative-performance numbers are based on the method described here . Percentages are the proportion of the total.

The challenge may be even greater for companies with the opposite performance profile, those in the lower right. Faced with flat or declining growth, they face the seemingly obvious task of focusing strongly on improving the top line. After all, in the face of such apparently poor results, their managers probably assume that significant improvement is largely a question of effort.

Not necessarily. Our analysis of relative performance suggests that some of these companies are already approaching the limits of what is feasible, given the structural constraints they face. For example, for companies in slow-growing industries, low or even negative growth might place them in the top quartile of relative performance. In other words, the mountain might be low, but they are already at or near the peak. Here, performance-improvement efforts risk mimicking Sisyphus, pushing his boulder uphill only to have it inevitably roll back down. An analysis of relative performance suggests that within their industries, absolute gains are unlikely.

The situations for companies in the remaining two cells are more straightforward. For those with low absolute and relative performance, the message is clear: All hands on deck. There is a need to improve in absolute terms, and there is plenty of headroom in relative terms.

Among those in the enviable position of having high performance in both absolute and relative terms, the challenge is to stay the course. This requires vigilance against complacency, but also the courage to resist the urge to “climb past the summit.” At the highest levels of relative performance, dramatic improvements are unlikely, and major growth initiatives are likely to fall short of expectations; they could even prove to be dangerous distractions from the important work of sustaining already-high levels of performance.

By extending this analysis of growth to other measures of performance — say, profitability — companies can begin to think more objectively about how they should set their performance-improvement priorities. Take, for example, a company with a 5% return on assets (ROA) and a 12% growth rate. Which should it seek to improve, and with what emphasis?

By translating those absolute performance measures into relative percentile ranks, companies can compare radically different dimensions of performance on a like-to-like basis. A 5% ROA might translate to the 85th percentile, while 12% growth lies at just the 50th. This suggests that there is more room to improve growth than there is to improve profitability — even as an unadjusted analysis of absolute measures suggests the opposite.

The implications of this sort of finding can be profound. For many companies, the initiatives most likely to drive growth — new-product introductions, geographic expansion, mergers and acquisitions — can look very different from profitability-driving initiatives such as R&D and improving operations and customer loyalty. And since you can spend a dollar — or an hour of executive time — only once, the choice of which path to pursue can have a significant and lasting impact on a company’s fortunes.

In our work with the C-suite executives of large, publicly traded companies we have found that a statistically valid analysis of relative figures often points in a surprising direction, even if the companies have been benchmarking by their industry peer groups.

You can apply our analysis of relative performance to your own company using our interactive tool. You might be surprised to learn that your low growth rate is actually quite respectable, given your company’s industry and size. Or you could learn that your double-digit ROA is merely middle-of-the-road. Similarly, you might find that there is more, or less, headroom available to you on the profitability front.

Either way, we believe that this additional perspective on your company’s performance will prove a valuable input in determining where you should focus your performance-improvement efforts.

We Should Want Robots to Take Some Jobs

The latest witch hunt is underway and gaining momentum. The witches are the rapid innovation in robotics and computing, slated to replace humans in performing increasingly sophisticated – i.e. “white collar” – tasks and so displace jobs across the employment spectrum. The dominant dismal view is that rapid technological innovation has been gobbling up jobs faster than it is creating them. Technological change is causally connected to the stagnation of median income and the growth of inequality in the United States.

For example, as David Rotman wrote in a 2013 MIT Technology Review called “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs” about the work of MIT’s Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee:

[Brynjolfsson and McAfee] have been arguing… that impressive advances in computer technology—from improved industrial robotics to automated translation services—are largely behind the sluggish employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even more ominous for workers, the MIT academics foresee dismal prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful new technologies are increasingly adopted not only in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in professions such as law, financial services, education, and medicine.

Two years later, this sort of pessimism is still the prevailing view.

But even class warfare and total societal meltdown is apparently not an apocalyptic enough vision for some. According to Ray Kurzweil, Elon Musk and others, once artificially intelligent machines are able to design other machines, humans will become an endangered species. Machines will have exponential improvement as a clear evolutionary advantage.

We appear to be cornering ourselves in the narrow view that crowds man and machine onto the same tasks. But there is an alternative view for a positive man-machine dynamic. While in the minority, arguments exist for a symbiotic man-machine future. They celebrate that which is uniquely human – meaning and creativity – and that which, in my humble opinion, should be the primary business of humans in the first place.

In his latest TechCrunch article, for instance, David Nordfors makes a distinction between a task-centered and human-centered economy. In the task-centered economy humans have no value beyond the tasks they perform. Consequently, they are indistinguishable from machines and will be replaced by them for reasons of cost-efficiency as soon as technically feasible. In the human-centered economy on the other hand machines liberate humans from predefined tasks with prestated outcomes. This allows them to exercise the value that emerges from collaborating with other humans on open-ended, creative endeavors. Nordfors cites Gallup’s astonishingly low figure of worldwide employee engagement (13%) to surmise the opportunity cost between the two economies: $140 trillion over the next few decades in favor of the human economy.

In “Reinventing the Sacred,” Stuart Kauffman pretty much puts to rest the notion that human brains can be framed as glorified computational devices and therefore are bound to become indistinguishable from algorithms as machines eventually attain astonishing sophistication. Kauffman draws from fields as varied as complexity, neuroscience, and cognitive science, and invokes Godel’s incompleteness theorem to point out that higher order human mental processes are beyond algorithmic enunciation. Philosophers such as Sanders Pierce and design thinkers such as Roger Martin have long proposed the ability of human minds to perform leaps of logic to get to creative solutions. Going beyond logical-based arguments and case study proof, Kauffman eloquently describes how machine algorithms, even based on the most sophisticated foreseeable AI technologies, can only solve problems which are bounded by prestated assumptions.

Why do I subscribe to Nordfors’ and Kauffman’s visions? For one, because in my life as a consultant I see the task economy that strips people of their uniqueness and dehumanizes them into glorified algorithm machines every day. It is the very reason why I have a job: because most of my clients have forgotten how to think and solve problems that aren’t tamable by an algorithmic framing. I like to call these “no precedent” problems.

We have, for the majority of humanity’s history, used humans for menial, mechanic, robotic, repeatable, efficiency-minded tasks. A select few were in the business of thinking creatively for the entire species. Technology has finally reached a threshold where creativity and meaning is accessible to everyone. In the 21st century, creating meaning and innovating will be democratized through technology. As David Nordfors rightly asserts, never yet seen avalanche of wealth and prosperity is waiting to be unleashed. We are on the verge of revolution of pace of progress that will forever eliminate the last form of human slavery: meaningless, dehumanizing, algorithmic work.

In closing, my test for outsourcing human work to machines is this: any task that has an output or outcome which can be pre-stated or even guessed, should eventually be performed by a machine. Humans should eventually be left to more or less exclusively deal with open-ended endeavors that generate new organic value (as opposed to efficiency derived value). Alluding to Peter Drucker’s thinking, effectiveness should be a human pursuit, while efficiency should be delegated to machines.

This post is one in a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

Zoning Out Can Make You More Productive

Thanks to our smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other devices, there is no longer a technology reason why we can’t be working every minute of every day. In principle, that should help us get more useful work done—we can use every minute for maximal efficiency. But while it’s obvious that our devices make us more productive in some ways, what’s less obvious is an important way they can actually harm our productivity: by interfering with mind-wandering, also known as daydreaming.

When we turn to our devices every time we get bored or find a break in the flow of work, we keep ourselves constantly processing new information. Being “always on” like this can make us less productive because it can block the brain processes that occur when we let our minds wander. Neuroscience and psychology research show that mind-wandering facilitates creativity, planning, and putting off immediate desires in favor of future rewards. Each of those can be important for working effectively. Not many other things we do can have such a broad impact.

For example, research published in the journal Psychological Science shows that we engage in what the researchers call “creative incubation” during mind-wandering. If we’re facing a challenge that needs some new ideas, we are more likely to find good solutions if we let our minds wander and then come back to the challenge. When we mentally drift to a new topic, our brains continue sorting out the tough challenge in the background. Tracking a lot of new information can interfere with that background mental work, limiting mind-wandering and blocking the incubation that leads to creative solutions.

Mind-wandering is also important for planning ahead. Researchers have found that what minds primarily sort out when left to wander is plans for our own future. Imagine you’re working hard on landing a new client. It’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day work of making calls, writing proposals, and so on, to the exclusion of planning what you will need to do to build a sustaining stream of clients. We often complain that we just don’t have the time for that longer-term view. But what we may not realize is that it is not just an issue of setting aside time to focus on planning. When we remain constantly focused on work, we can block the processing that would facilitate planning our lives.

Similarly, researchers in Germany have shown that mind-wandering helps with that ever-important challenge of holding out for something better in the future, rather than giving in to immediate desires. Suppose you’ve been working for months on landing that new client and they finally make you an offer to work together, but at a low price. It can be tempting to jump at whatever they offer, just wanting something productive to come from all the work you’ve already put in. But doing so would keep you from holding out just a little longer for a deal that would really make it worth your while. During mind-wandering, you are capable of connecting with your longer-term goals and discovering new ways to think about these kinds of situations.

Unless we turn off the information faucet from our devices, most of the information we take in is just going down the drain. I’m not suggesting we stop using our devices, but we should put them down from time to time, or leave them out of the room during a work session. That way, when we lose focus we are more likely to mind-wander than to get sucked into handheld distractions.

So if your mind is trying to wander, let it. Help it go to a new topic, but one that won’t need too much mental effort. Don’t check your favorite website or your email. Instead, allow the background processing that mind-wandering affords so you can get back to work and be more effective. Mind-wandering doesn’t need to take very long. You may be refreshed in a few minutes.

Here are some steps you can take to mind-wander:

The next time you find it hard to concentrate, walk to the window and think about the people or cars going by for a few minutes, until you get bored.

Close your eyes for a few minutes and notice the sounds in the room.

We used to take cigarette breaks. Now we pick up our devices. You can still step outside for a couple minutes without a cigarette. But leave your device inside.

To be effective, minds need opportunities to wander. Our devices make that hard. But with a few small changes, we can learn to help our minds help us be more productive.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers