Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1289

June 2, 2015

Persuasion Depends Mostly on the Audience

Dale Carnegie once noted that the only way to get someone to do something is to get that person to want to do something. Thus all persuasion is ultimately self-persuasion. Even if I put a gun to your head, you are still free to decide what to do, albeit admittedly somewhat constrained.

Scientific meta-analyses show that we are more likely to be persuaded when requests are congruent with our values, self-image, and future goals. In other words, people are easily persuaded of that which they wanted to do in the first place. As the French philosopher Blaise Pascal noted: “People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the mind of others.”

That said, it is also clear that some people are generally more persuasive than others. These charismatic, politically savvy, and socially skilled individuals tend to be sought-after salespeople, managers, and leaders. Thanks to their higher EQ, they’re better equipped to read people and are able to leverage this intuitive knowledge to influence others’ attitudes and behaviors. And because they seem more authentic than their peers, we tend to trust them more, to the point of outsourcing our decision-making to them. This is what most people hope to get, but not always receive, from their politicians.

Yet we may be giving these alleged superstars of persuasion more credit than they deserve. In fact, a great deal of psychological research indicates that, much like Dale Carnegie suggested, the key triggers of persuasion take place in the receiver of the message, whereas persuaders typically account for less than 10% of the effect. What, then, are the main psychological forces that explain when and why we are likely to be persuaded by others? Here’s what the science actually shows:

We yield to persuasion because we cannot tolerate ambiguity. Indeed, our need for closure – the desire to maintain internal consistency between our different beliefs and behaviors – can generate abrupt attitude changes and a passionate sense of certainty. For example, interviewers rate candidates more negatively when they have been given negative information about them beforehand; and most people would switch instantly from liking to disliking an idea when they find out that it was proposed by someone they dislike. By the same token, our subconscious drive for maintaining consistent thoughts and ideas can often make us immune to persuasion even in the presence of irrevocable evidence. For instance, managers are less likely to notice mistakes in their employees when they were responsible for hiring them, because the alternative would be to admit that they were wrong, which would make them feel stupid. The bottom line is that persuasion depends more on what we think of ourselves than what we think of the message. As Nietzsche observed: “One sticks to an opinion because he prides himself on having come to it on his own, and another because he has taken great pains to learn it and is proud to have grasped it: and so both do so out of vanity.”

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

We tend to see others as more gullible than ourselves. This so-called third-person effect is well-established and suggests that there is a comforting and ego-enhancing element in feeling more independent than our peers, and this feeling fuels our self-deception. In line with this, we are generally more capable of spotting persuasion attempts when they are directed at others than at ourselves. Even when scientists explain this to laypeople, most still see themselves as less gullible than others, much like with other better-than-average biases.

Few things are more persuasive than fear. With the exception of psychopaths, the most effective way to persuade people is by activating their threat-detection mechanisms. This explains why people are generally more motivated to avoid losing something they perceive they have (e.g., love, health, money) than gaining something they may want to have. “Buy this and you’ll live longer” is generally less effective than “buy this or you’ll die sooner.”

Persuasion is emotional first and rational second. Indeed, we are more likely to yield to persuasion in order to maintain or attain certain mood states than in order to gain knowledge or advance our thinking. When someone makes us feel good – intentionally or not – we will be more likely to agree with their views and be persuaded by them. In persuasion, warmth and empathy go a lot further than logic and evidence. It is for this reason that much of advertising targets our emotional processes. That said, it is important that these attempts are subtle, so that they seem genuine. Over-the-top manifestations of warmth will seem as fake and artificial and deliberately manipulative as those Super Bowl commercials with cute puppies stranded in the rain.

In short, effective persuasion highlights the irrationality of human thinking. We may be living in a data-driven world, but that does not make people more logical. This is why the same people may regard an idea as absurd one day, and amazing the next. As Arthur Schopenhauer noted: “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

Be a Leader Who Can Admit Mistakes

This might sound obvious, but if you want to build a more engaged workforce you need to, well, engage. That means, whether you are a CEO or a frontline manager, you need to be working hard to connect, face-to-face, with your people. That can mean anything from walking around and making pit stops in offices and cubicles to holding town hall discussions with your teams and staying to answer questions afterward. But most leaders simply can’t make time to sit down with every person in the company, in every office around the world, on a regular basis. It’s mathematically impossible. So what should leaders do instead?

In my experience as CEO of Red Hat, I’ve learned to keep the lines of communication open and find ways to connect with associates when I can, either in person when the opportunity presents itself, or virtually via email and other electronic correspondence. Being accessible and approachable is critical to effective leadership.

For example, recently I was involved in a roundtable of CIOs from many of our customer companies where I was talking about leadership lessons (like this one) from my book, The Open Organization. As it happened, there were a few Red Hatters in the audience as well. After the meeting wrapped up, a couple of these associates came right up to me to talk about some of the themes in the book that resonated with them. They also recommended several other books they thought I would appreciate. I love that this happened because it shows that members of the organization whom I have never met before are comfortable approaching me and having candid discussions with me about leadership. How many CEOs with close to 8,000 associates at their company can say the same?

As powerful as accessibility is—and without it engagement is impossible—I’ve learned that nothing builds engagement more than being accountable to the people in your organization. You simply have to have the confidence to own your mistakes and admit when you’re wrong.

Being a leader doesn’t mean that you’re always right or that you won’t err. What being a leader does mean is airing the reasons for why you did something and then making yourself accountable for the results—even if those you’re accountable to don’t directly work for you.

That’s how you truly sow the seeds of engagement. Think about it: who would you rather trust—the person who denies anything is amiss or the person who admits their error and then follows up with a plan to correct it? Better yet, what if that same person who admits they made a mistake reaches out to their team for ideas on how to make things right? I’ve found that leaders who show their vulnerability, and admit that they are human, foster greater engagement among their associates.

I speak from experience. Early on in my tenure as CEO of Red Hat, we acquired a company whose underlying technology wasn’t entirely open source. But rewriting the code and making it open source was going to mean months of work, something I didn’t think we could afford. So, after much debate and back-and-forth, I made the call to go to market with the product as is. Big mistake. It soon became clear that both our associates and our customers disliked using the product. There was only one thing to do at that point: rewrite the code. Only now, instead of being a few months behind schedule, we would be off by more than a year. Ouch.

Of course, there was quite a bit of anger and frustration among Red Hatters about the extended delay. But I owned it. I put myself out to the company and my board of directors by admitting I was wrong and that we were going to do our best to address the mistake.

I realized that our associates deserved to hear the story of why we made the decision as much as the board did. When you don’t make the time to explain why you made your decision, people will often assume the worst all on their own: that you’re detached, dumb, or don’t care. But when I made the time to explain the rationale—that we had in fact put a lot of thought into it—people finally understood.

Many Red Hatters told me how much they appreciated that I admitted my mistake. They also appreciated that I explained how I came to make the decision in the first place. That earned me their trust. If you want to have engaged employees, in other words, you need to explain why decisions were made. That’s how you build engagement—which also makes you a stronger leader.

In short, being accessible, answering questions, admitting mistakes, and saying you’re sorry aren’t liabilities. They are exactly the tools you can use to build your credibility and authority to lead.

Innovation Isn’t the Answer to All Your Problems

What should leaders do to boost their organization’s ability to innovate? There’s a seemingly endless list of options to consider. Set up a new-growth group. Launch an idea contest. Change the reward systems. Run an action-learning program to develop the top leadership team’s ability to confront ambiguity. Form a venture investment fund. Take a road trip to Israel or Silicon Valley. Build an open innovation platform. Bring in outside speakers. Hire seasoned innovators. Paint the walls blue. Buy a lot of books.

And what’s the point of all these approaches? To infuse innovation into day-to-day activities of your company so your frontline workers will identify customers’ problems and solve them in novel ways? To create an elite squad of business builders that can launch a disruptive business? To change the way senior leaders think so they are more comfortable with ambiguity? To developing a structured approach to rolling out a series of new-growth ventures? Some combination of all of the above?

Too frequently, companies decide what they’re going to do before determining why they’re going to do it. That’s challenging, because developing innovations that have a lasting impact requires going beyond doing one single thing. Improving innovation is a system-level issue, requiring a coherent and consistent set of organizational interventions. To begin to determine what set of interventions makes the most sense for your company, first you need to step back and answer a fundamental question: What problem does innovation need to solve?

The answer to this question matters substantially because it determines in which part of the organization a company needs to intervene, what resources leaders need to be ready to commit to, and how long it will take before any impact is felt.

One clear problem innovation can solve is creating new growth. An executive who has this problem recognizes that the company needs to push the boundaries of today’s business to achieve its financial objectives. Perhaps competitive intensity has increased, a new disruptive development has emerged, or a company’s core business has begun to slow. Hitting growth and profit objectives, then, requires boosting the ability to create new businesses that wouldn’t naturally result from day-to-day operations.

If this is the only problem innovation needs to solve, efforts are best isolated from the core business to minimize distraction. A good starting point is to build what we have called elsewhere a minimum viable innovation system, a focused but connected set of interventions designed to kick-start new growth.

Competing more effectively in existing markets is a completely different problem. In this circumstance the organization might still be seeking to spur growth but be confident it could if the creativity and ingenuity they see occurring in spurts throughout the organization could be more systematically harnessed. Perhaps frontline salespeople and customer service representatives could find innovative ways to attract and retain customers. Maybe internal support functions could find innovative ways to actually deliver more with less. If an organization tapped into its full innovation potential, perhaps employee engagement and loyalty would increase.

The fundamentally different nature of this problem demands a different set of interventions. Rather than isolating innovation efforts, here innovation mind-sets and behaviors need to be infused into the day-to-day activities of a broader population. High-leverage interventions might include investing in employee training or dedicating a team to help others with common innovation activities, like designing and executing experiments. DBS, one of Singapore’s leading banks, has set up just such an innovation function under Paul Cobban, the chief operating officer of its technology and operations group. One thing Cobban’s team provides is “experimentation as a service” to other teams in the bank working on new ideas, helping them design, execute, and draw insights from such experiments as consumer use tests, operational pilots, and the like.

Organizations may wish to tackle both of these problems simultaneously – reaping new growth from existing operations while also pursuing business beyond its current boundaries. Executives in this circumstance recognize that they need a portfolio of innovation efforts that balance current and future needs. Here, efforts should focus on institutionalizing innovation by working on underlying systems that govern resource allocation and decision making. This kind of intervention requires serious senior leader commitment because of the scale and scope of the effort. In describing our work with Procter & Gamble, we used the metaphor of a factory for new growth. Just as building a factory takes time to build, truly institutionalizing innovation takes years of hard work.

Investing in innovation isn’t a cure for all ills. If the core business is in crisis or is struggling with basic operational issues, leaders ought to focus on fixing those problems first. Innovation also isn’t a quick fix for a struggling business: the full benefits of investments in innovation are only fully apparent years in the future. Finally, innovation is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Leaders need to make the strategic choice: whether to isolate new growth efforts, infuse everyday innovation into daily routines or truly institutionalize innovation. Taking the time to determine which choice is appropriate for you will focus your attention and accelerate the impact of your subsequent innovation efforts.

June 1, 2015

The Right Time to Mention Your Vacation Plans in a Job Interview

The interview is going well and you think you might be the preferred candidate. However, you have a problem. You know that the hirer wants to fill the role quickly, but you have an extended vacation already booked. The job starts in July, but your non-refundable plane tickets are booked for August.

When do you mention this?

Candidates get worried about anything they think may get in the way of a job offer, and time off work is high on the list. When is the right time in the hiring process to mention existing vacation plans, or ask about time off policies?

Timing matters enormously; think about when this information needs to be disclosed. Clearly, you don’t want to be saying, “I can’t wait to start” one moment and then saying “I’m not available for four months” the next, whether it’s because of a vacation or because you’ve got a major project at your current job you’d like to see through.

A good rule of thumb is to wait until the organization has decided you’re number one. Save any concerns or questions about vacation or flexible working until after you have been made a verbal offer – that’s part of your due diligence process between offer and acceptance. You can always talk about how you’re excited to start “once the details can be worked out.”

Further Reading

HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Managing Yourself

Managing Yourself Book

24.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When the time comes to disclose your plans, think hard about what this really means, both for you and the employer. Even if you don’t have a vacation already booked, it’s sensible to want to take some time off between jobs, since this could be one of the few times in your work history when you’re not checking emails on the beach. But listen hard to the employer’s problem list. If it’s vital to get boots on the ground, you may have to think about losing deposits and canceling flights.

But first, try the language of deal-making rather than the language of worry. Instead of identifying your vacation as a problem issue, mention it in passing as one of the minor things that need to be tidied up before you join, alongside finessing your contract and role description. The approach “I’m sure we can work around this” is stronger than “I’m sorry, but…”

You can also offer a “happy sandwich” of information – one negative between two positives. So, enthuse about the role, mention your vacation plans, then talk about what you hope to achieve in the job. If they want you, this will work, because “I want” is drowned out by “this is what I bring.”

Rehearse how you will talk about this with the same attention you’d give to disclosing any other negative. The reality is that anything you think might get in the way of a job offer will get in the way – but only with your help. So, for example, talking about commitments outside work could pitch you as a well-rounded personality, or could plant the idea that your job is not your main focus in life.

As you practice what you’ll say, listen to the messages you’re foregrounding – how much is about your world, and how much is tuned in to the employer’s perspective? If you’re entering discussions talking about needing a break, this can quickly translate into “burnt out.” If your schedule is already overstuffed with personal matters, how are you communicating the idea that you’re hungry and ready for the role? They want you to say “yes” with genuine enthusiasm, otherwise you sound like someone checking your diary after being invited to the best party on the planet.

Hirers can often come across as tough cookies, but they want to be liked as much as you do – or, at least, they want you to look and sound as if this role is the perfect next step in your career. And what they want from you is high commitment and low risk. If you can demonstrate both of those, you should be able to get the job you want and the time off you need.

Prioritize Your Life Before Your Manager Does It for You

In their several years of working together, Jin-Yung had never really negotiated with her manager. She would simply say yes even if it threw her life into temporary turmoil, as it often did. She had given unknowable hours to executing every request and task, diligently delivering them in neat and complete packages, no matter the sacrifice.

After attending a workshop I was teaching on “essentialism,” or the disciplined pursuit of less, she decided to create a social contract to draw some boundaries at work. Specifically, it outlined how she could increase her productivity at work while also having five days off of work to focus entirely on preparing for her upcoming wedding. Jin-Yung’s manager agreed to the terms she presented and was surprised and delighted when she put in several especially-focused days and completed her usual work ahead of schedule. This allowed Jin-Yung the chance to immerse herself in the uninterrupted days of wedding planning that her boss had agreed to.

However, in the midst of her wedding planning, her manager asked her to take on an additional project prior to an upcoming board meeting because someone else on the team had dropped the ball. This time, instead of capitulating to pressure from her manager, she pointed to the social contract and said words to the effect, “I would love to help with this project and I can see that this is a problem. However, we came to a clear agreement on this and I have completed my side of the bargain. I have planned for this time, I have worked hard for it and I deserve to have it…guilt-free!” She then spent five days immersed in preparing for her big day.

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

At first, her boss was fuming. But after laboring over the task herself for days, she saw all sorts of flaws in the way she’d been managing the team. She soon realized that if she wanted to be a more effective manager, she needed to pull in the reins, and get clear with each member of the team about expectations, accountability, and outcomes: basically to set up a social contract with every member of the team. Jin-Yung not only opened her manager’s eyes to unhealthy team dynamics and opened up a space for change, she did it in a way that earned her respect.

Jin-Yung was so affected by this experience that she decided to incorporate the experience into her vows, promising that she would prioritize her relationship with her husband above all others.

Many of us are faced with similar high-stakes negotiations with our managers when we want a raise, a stretch assignment, flex time, or the ability to work from home. Here are three rules for negotiating for what you need more effectively:

Rule 1: You can’t negotiate if you don’t know what you want.

It never ceases to amaze me how often I ask people, “What do you really want?” and they look at me blankly, unable to articulate the answer. It’s not that they don’t want things, it’s just that they don’t have a high level of clarity regarding the matter.

This matters because our work life doesn’t take place in a neutral vacuum. What we spend our time doing is the result of a dynamic interaction between internal clarity (what we want to do) and external pressure (what other people want us to do). Indeed, our era is distinguished not so much by information overload, but by opinion overload. To ensure that our own voice is not lost in the noise around us, we need to know what we really want. If we don’t get really clear about that, then other people will fill the void with their agendas.

Rule 2: Clarity is the beginning of all empowerment.

Key to Jin-Yung’s story was creating a social contract which clearly articulated what she would do, by when, and what the positive and negative consequences would be for compliance and noncompliance. By getting clear about this, she was able to better negotiate what not to focus on both before her five-day leave and while she was on it.

Here are the six most important questions to answer when writing out a social contract:

What is the most important, mutually beneficial, desired result over the next X period of time?

Why is this important?

What needs to be eliminated, deferred or reduced?

What resources need to be reallocated or increased?

When will we get together to review progress?

What are the consequences (positive or negative) for performance or nonperformance?

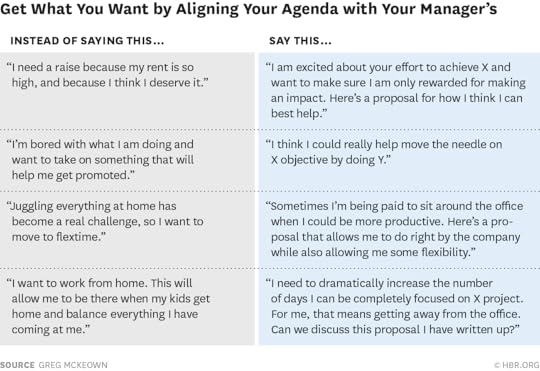

Rule 3: Speak in terms of your manager’s agenda (not your own).

Especially when working with busy executives, there is little point in simply talking about what you want. They are often so focused and burdened with their own agenda that an additional request, however valid, can feel like an additional pressure or a burden. With a little preparation, you can express the same desires in a way that is aligned with your manager’s agenda, thus significantly increasing the chance that you will be heard and that the negotiation will go well, as shown in the chart below.

None of these examples is perfect, but each illustrates how much better it is to start with your manager’s agenda. The truth is that to get anyone to act, we have to create an eager desire in the other person by speaking to what he or she wants most.

By following these three rules, we can be better negotiators at work, we can make that critical shift from “order taker” to “trusted advisor,” and we can learn to better balance our lives.

Get Your Organization Ready for 3D Printing

In the late 1980s, Motorola faced a major threat to its fast-growing cell phone business. Rivals were developing digital technology to replace the existing analog standard. Internal debate raged. Should Motorola keep its focus on analog, or switch over to digital? Build off its core competence, or play from weakness? Could both technologies exist side by side? Or would only one survive?

Engineers at the company came down squarely on the side of analog. Digital, they pointed out, was simply inferior to analog as a medium for storing and transmitting audio. After all, it stripped away 60% of the information contained in the original analog message.

What those engineers couldn’t see was that, for most listeners, digital technology’s advantages far outweighed the often undetectable losses from digitization. That’s partly because they had spent much of their lives building up their expertise in analog technology. A shift to digital would require them to learn a great deal from scratch. So it was easier to see the negatives than the positives. The end result was that Motorola’s conversion to digital took much longer than it needed to. The company lost its leadership of the very industry that it had invented back in 1973. And it wasn’t alone – another audio leader, Sony, similarly lost market share in electronics because of its analog bias.

An equivalent challenge is now looming for companies in many industries. 3D printing, or “additive manufacturing,” essentially digitizes the production process. Like digital audio in the 1980s, this young technology has some drawbacks compared to conventional “subtractive” manufacturing. But as I explained in an article in the May issue of HBR, the flexibility and versatility it offers will eventually make it the preferred choice for companies in many industries. And the opportunities to combine parts, reduce inventory costs, and earn a premium price for customization often compensate for the higher direct costs of 3D printing.

Insight Center

The Future of Operations

Sponsored by GE Corporate

The technologies and trends shaping tomorrow’s businesses.

I recently attended a private conference with panels led by manufacturing experts from multi-billion dollar firms. One after another they explained why 3D printing wasn’t ready for high-volume manufacturing in their industry. They feared problems with durability and strength, not to mention customer reactions to the horror of discovering that their products were printed. (It was as though they’d never heard of Walmart, whose profitability depended on selling products from overseas factories with lower quality standards.)

Then a young woman shook things up. She got up to the podium and said, “It’s a good thing I never met any of you before. Otherwise my firm wouldn’t have made $40 million last year. You are so busy looking at what 3D printing can’t do that you’re ignoring what it can do!”

While her competitors had dismissed additive manufacturing because it couldn’t (at that point) print an entire product, she had focused on just one element of the product. Her firm ramped up from 100 customized parts to 10,000 in just one year. It is now expanding into other parts, and will soon be able to offer customization of the overall product at a premium price. As the company moves down the learning curve and costs come down, the savings from reduced waste, inventory, and assembly labor will even make it competitive for the mass production segment of the market.

Her secret is a process I call “Just Say Yes”: Listen to what your engineers say, then put them to work solving those problems one by one, even if the solutions aren’t immediately apparent. Just say yes is much like Gene Krantz’s famous command, “Failure is not an option,” when faced with the Apollo 13 crisis that nearly killed three astronauts on the way to the moon. Here’s the process in four steps:

1. Gather knowledge from the outside. Don’t rely solely on your in-house engineers – some of them are likely to be guardians of the status quo. Reach out to additive manufacturing printer and software providers, and your industry associations, to see what already exists for your product categories. Talk to universities and governmental laboratories to learn about the current state of 3D printing and how well it performs on the materials and attributes that your customers prefer – not just the ones you have always provided. Include your staff engineers on the learning teams but make sure they don’t dominate the discussion.

2. Move one baby step at time. Build expertise and reduce internal resistance through incremental experiments, exploring and adjusting to new technological development as you go. Engineers love challenges, so internally you can set up tiny, non-threatening pilot programs and see where these take you. Always listen to skeptics and take the problems seriously, but project confidence that the kinks will be worked out over time.

3. Focus and prioritize. No firm can explore the many possibilities of additive manufacturing all at once. So you’ll want to start with the most promising and feasible choices first, and build up small wins. But don’t expect a carefully planned sequence of development. As technology and the industry ecosystems develop, you may well adjust your priorities as you meet various milestones.

4. Keep an eye on the long run. Especially for large companies, the goal is to revamp the industry’s value chain and ecosystem to reduce total costs of the value chain and especially your firm. So look for opportunities to develop or support an emerging software platform or superior printer technology. Your explorations should have a logical, cohesive, long-term goal of pulling together the initiatives into an integrated 3D-printing-based manufacturing system.

With enough encouragement, you’ll see 3D printing champions emerge in your organization to help drive the process forward and build momentum. Some people (and organizations) won’t be able to embrace the technology in time and will be passed by. If you keep Motorola and Sony in mind, you won’t be one of them.

When a Mid-Career Move Falls Flat: The Story of Stripedshirt

In the early 1990s, Laura Beck was a college student living in Boston who regularly attended Red Sox games. She’d dutifully don a Red Sox jersey, but she’d quietly seethe. “I didn’t want Wade Boggs’s name on my back,” she recalls. “I didn’t want to wear a jersey.” So in 2010, after a successful 18-year-career in high-tech PR, she quit her job to launch Stripedshirt, a company selling fashionable, feminine shirts in team colors. This month, after five years of agonizingly slow sales, she called it quits by posting a funny video that reflects on her entrepreneurial failure, shows her garage filled with unsold merchandise — and offers a liquidation-sale discount. In its first three days, the video was viewed more than 100,000 times on Facebook. In a conversation with HBR, Beck reflected on how a midlife crisis led her to launch the business — and why she opted to advertise her failure in a bid for closure. An edited version of our conversation follows:

HBR: Why did you launch the business?

Beck: I had what I consider a midlife crisis. I was on the brink of turning 40. I have two daughters, and my oldest was about to start kindergarten. I’d worked for 18 years in tech PR, and I loved my job and was good at it — but day care had raised my babies, and I’d made myself a promise that when my children entered elementary school, I’d change my career so I had more time to spend with them. And I’d dreamed about starting this business for years. I’m a big sports fan, and every time I’d put on a stupid sports shirt to go to a game, I’d think: “Why can’t I just wear an orange-and-white striped shirt to a University of Texas football game, or a gray-and-black striped shirt to see the Spurs?” But it really was a midlife crisis and this sense of now-or-never, I need to do it.

You and Your Team

Mid-Career Crisis

When you’re feeling stuck.

What went wrong?

A lot of things. There were three big lessons. The first was about inventory, which is especially hard in apparel. To get a manufacturer to make your stuff, you need to place gigantic orders, and that makes it very difficult to test or prove a concept. My initial order was for 14 color varieties (representing the most popular team colors) in 15 sizes, which was more than 10,000 shirts, and even then I had to beg a company in India to take my tiny order. The second mistake was that I didn’t want a partner or investors or a board — I’d done PR for too many startups where partnerships created squabbles and conflict, and I didn’t want a team. But because of that, I never really had my feet held to the fire. I kept taking on part-time PR work on the side, which was a distraction. The third lesson, which was probably the biggest, is that marketing alone does not a company make. It’s ironic because I spent years in PR preaching that to clients — “just because you get media coverage doesn’t guarantee you sales” — but when it came to my own dumb business, I somehow thought I could create sales and demand by doing PR. I never had a sales team. I never had distributors or agents. Somehow I thought word of mouth and buzz could get this business up and running, and it never did.

When did you know it wasn’t going to work?

About 18 months ago. I’d given away tons of shirts to fashion bloggers, to events, to charity. It created name recognition, but it never led to big orders. I stopped doing outbound PR. I’d still sell a few shirts every week, but in my mind I was done. Our accountant began pressing me to figure out what I wanted to do about write-downs.

What advice would you have for anyone thinking of doing a startup in the physical goods space, as opposed to a digital product or an app?

Don’t do it. Seriously — don’t. Consumer products are brutal. Apparel is especially so — it’s all about what’s hot and popular now, and that can be very fleeting.

Where did the idea for the video originate?

For the last few months, when people asked me about the business, I’d joke that I was a failed entrepreneur. Then at lunch with a friend in April, I joked that while many startups launch on Kickstarter, I needed to do a “Kickstopper.” One of my friends said we should call it “Indie-No-Go.” I wrote the script and blocked it out myself — I really wanted to show people how a business like this can take over your house, your garage, your spare bedroom. Everything in the video is true. My daughters are completely sick of wearing striped shirts, and their friends are tired of getting them as birthday gifts.

Is the video mostly an attempt to liquidate inventory?

I’m more excited about how many views the video is getting than I am about sales. The video is about closure — it’s a bookend on the five years I spent on this. Publicly admitting defeat in the video gets me off the hook from having to explain how the business is doing every time somebody asks me. I think of it kind of like a relationship. Until you tell all your friends your boyfriend broke up with you, they are going to keep asking about him every time they see you. Everyone asks me “how are the stripes?” Now I can just point them to YouTube. My business failed, and I wanted to be out loud and proud about it — that Stripedshirts and I are over.

What comes next?

I’m going to clean the shirts out of my garage, continue doing part-time PR work, and have more time to be an active mom. I figure have another five years before my daughters want nothing to do with me.

How Marketing Is Evolving in Latin America

Latin America is a modern marketer’s dream, and not just because of its size. By 2020, nearly one out of every 10 dollars in the world economy will come from Latin America. The region will soon represent 10% of the global population and 9% of global GDP, with 640 million customers. It also has the in the world, with social media adoption even surpassing that of the United States. Positioned at the forefront of digital and mobile adoption, Latin America provides an interesting look into how new marketing trends are taking hold on a global scale.

At HubSpot, we conduct an annual global survey on the state of inbound marketing, which involves capturing customers’ attention with valuable content discoverable through social media and organic search — a more efficient approach to lead generation in the internet era than traditional “push” marketing efforts. As part of this omnibus research effort, we surveyed 2,700 marketers who reside in Latin America, where inbound marketing is seeing a wave of growth. We also spoke with several Latin American businesses that are practicing this new way of marketing to hear about what it’s like to undergo this shift. Our research reveals that inbound methods are a particularly good fit for small and medium-sized businesses, which are plentiful in Latin America, that have traditionally struggled to compete with larger companies and their marketing budgets. A few highlights show how marketing is evolving in Latin America—especially when it comes to inbound techniques:

Inbound marketing is commonplace in Latin America. The vast majority (86%) of Latin American marketers surveyed were familiar with inbound marketing, and 60% said they practice it today. (Since this was the first year we had a large sample size from Latin America, we won’t have comparison data until next year.) Roberto Madero, the CEO of GROU Crecimiento Digital, a marketing agency in Mexico, explains that Latin America is following the lead of business leaders in the United States and Europe. “Financial pressure is forcing companies to become more efficient, and more Latin American executives have started shifting some of their marketing dollars to search engine marketing. It’s more measurable, targeted, and effective than traditional advertising,” Madero said.

These sentiments are echoed by Andre Jensen, director at Agência Inbound, a marketing agency in Brazil. He sees inbound marketing as a way to gain a strategic advantage over local competitors and explains, “Inbound marketing provides a considerable competitive edge for companies wanting to increase win rates while shortening their sales cycles.”

Marketing automation software is not prevalent yet. More than one in every three companies in North America purchase some type of marketing automation software. These tools do some of the heavy lifting for marketers by automating processes such as sending e-mail campaigns to segments of a database, guiding them to marketing offers, collecting their data, and adding them to workflows.

By comparison, very few companies in Latin America use marketing software today, and only 3% of respondents listed automation as their top priority for software features. Instead, these marketers are more focused on other areas, such as content creation and SEO. Why so? Generally, leads that come to salespeople from inbound techniques, in which someone is already searching for a solution, tend to be highly qualified and close more rapidly than leads obtained from outbound methods.

The cost of acquiring leads is lower for companies that use inbound marketing. Companies in Latin America that are using inbound techniques spend 63% less to acquire new leads than those that do not. This is likely because inbound marketing focuses a marketer’s efforts on reaching buyers at the time they are already searching for something. Outbound techniques are far more expensive, and often involve flooding the market, including those who are not necessarily interested, with messages in an effort to lure buyers out of the woodwork.

In fact, some businesses, such as Samba Tech, a video hosting company in Brazil, have redesigned the entire marketing function in response to the inbound trend. A year and a half after moving toward an inbound-led strategy, they reported impressive results. “Inbound marketing has helped us close four times more clients than in the previous year,” explained Pedro Filizzola, the company’s CMO. In short, Samba Tech has found what many other companies are discovering: inbound marketing costs less and leads to more revenue.

Other types of marketing are getting more expensive. In the past, paid search was an inexpensive way to reach customers in Latin America. However, costs are rising slowly over time, as there is more competition from companies trying to out-bid each other. Even though the price hikes have been gradual so far, budgetary constraints are causing more businesses to move toward less costly inbound approaches. Javier Morales, co-founder and director of Leads Rocket, a marketing agency in Chile, pointed out, “As pay-per-click grows in Latin America, we have found that our clients do significantly better when we complement it with content, social media, and other tactics.”

Visual and video content are more important in Latin America. When asked about their top priority projects, 17% of marketers in Latin America reported prioritizing visual and video content, compared to 11% of their North American counterparts. With higher adoption of mobile and social in this region, it makes sense that this type of content would be prioritized. Latin America has been picking up steam for online video consumption for a while now, with countries like Chile leading the way.

Every business seeks to find a competitive advantage, but in today’s increasingly online world, small and medium-sized businesses with less capital are more empowered than ever to gain market share from larger rivals by expanding their reach faster and inexpensively. Inbound marketing amplifies this trend, and is already becoming widespread in North America as a result. However, as the inbound marketing trend moves beyond borders, it appears to have even greater potential and importance for marketers in other parts of the world. Now these global businesses are not only embracing the inbound marketing trend, they’re driving it forward.

Note: the full reports are also available in Portuguese and Spanish.

Why Mega-Mergers Are Back in Vogue for Internet Companies

A growing number of publicly traded consumer internet companies are making the choice to “go private” which is creating a wave of consolidation. The most recent example is AOL, recently acquired by Verizon — but this merger won’t be the last. So why is this happening, and what happens next? Based on my experience going through three mega-mergers, at Trulia, Nokia, and Siebel, and on dozens of interviews with industry insiders, I see two major reasons for the trend, and three ways companies are likely to respond to it in the future.

First, consumer internet companies tend to go public too early.

Since the last financial crisis, many new regulations have been implemented to protect shareholders, increasing the pressure on management to meet earnings expectations by prioritizing short-term over long-term. For many consumer tech companies, this post-IPO pressure on financial returns is too high.

Because they are innovative by nature, consumer tech companies need to invest heavily in research and development, which could be done if they had a portfolio of products at different stages of maturity, with some of them being established cash cows. However, many of them go public at a point when they only have one product, even if it’s still unrefined. Some of them go public before even turning a profit.

What compels these companies to IPO prematurely is that they need to provide a liquidity event for their institutional investors, and sometimes for their founders or early employees. A soaring stock price is one of their strongest employee retention tools, especially right now, when there is a war for technical talent in booming Silicon Valley. Facebook tried to ignore Wall Street pressure in 2012 upon its IPO, but quickly decided to shift course after experiencing attrition.

The impact of going public too soon is “a death by a thousand tweaks.” Left with the only option to show revenue growth by milking a single product, many consumer tech companies resort to tactical optimization which delivers very little value to their consumers, if any. The extra revenue that these tweaks generate gives the impression of momentum but only the market leader in any category has a real chance at surviving too many of these cycles.

Because of the post-IPO pressure, many emerging tech companies like Uber are trying to stay private at all costs (this is what resulted in the term “unicorn” for startups that raise over a billion dollars in investment without going public). However for the companies that are already public and don’t have a dominant position in their category, they have become acquisition targets. The good news is that there are many buyers out there.

The second major reason this is happening now is that the economic recovery has strengthened two currencies: cash and stock.

Just like people do, companies tend to buy more when they feel rich. With interest rates at an all-time low, investors have turned to Wall Street for higher returns, so stock prices are climbing. As a result, a number of companies find themselves in a position where they can afford to make a large acquisition because they can use their stock, which is trading high, as a currency. This timing is especially of interest to telecom and media incumbents, who are now ready to place their bets in the Internet space, now that it has matured and that the survivors like Yahoo and AOL are struggling.

In addition to stock, cash is another widely available currency at technology giants like Google, which is not ready to give its cash back to shareholders in the form of dividends, as Microsoft recently started doing. It wants to continue to fund innovative projects, particularly in connected car and local businesses, both of which are natural complements to its Maps business. Besides, the internet giant recently missed the boat on critical innovation sectors, one of them being social. This is one of the reasons for the recent rumors of a possible acquisition of Twitter by Google.

It’s chess time. Companies who have the currency to buy and a strategic reason to do so are the most likely to make a move.

With consolidation ahead, the consumer internet space is going be very dynamic over the coming months. There are three types of moves we can expect:

Defensive move: A few years ago, Microsoft acquired Nokia as a way to enter the mobile market after it had missed its window. Today, telco market leaders like Verizon and Sprint are in a similar position. They need to maintain their leadership in the mobile space. In the last era, they spent most of their energy creating walled-gardens to protect their position on the voice segment, while new entrants carved out a position for themselves in the data segment. Now that the battle for voice is over, telcos are turning their focus to data. Because they struggle to drive innovation internally, they look to buy an internet brand, like Yahoo or AOL. Other rumors of defensive moves include Google trying to acquire Twitter, and YellowPages.com trying to acquire Yelp.

Offensive move: In 2014, Facebook purchased WhatsApp when it realized that it needed to have a dominant position in the messaging segment. Marc Zuckerberg seems to have an incredible talent for timing the acquisition of winning consumer services like Instagram and WhatsApp. Had he bought them later, he may have had to pay a much higher price; had he bought them sooner, he would have taken the risk to make the wrong bet. Today, companies like Apple and Google are ready to make similar bold offensive moves in the connected car market. Rumors of a Tesla acquisition have been heard, Lyft could be another candidate.

Portfolio approach: The two previous types of moves demonstrate how hard it is even in bleeding-edge companies to drive innovation continuously. Hard but not impossible for someone like Barry Diller. His internet conglomerate, IAC, which owns Match.com and OKCupid among others, has recently launched a new dating service called Tinder, which is taking over the world of young singles. IAC is taking the same approach to dating as most traditional consumer packaged goods companies do to products like dishwashing powder. Instead of making costly acquisitions to expand their portfolios, they constantly launch new products at small scale, in what is called a test market, until it has been optimized enough to be broadly rolled out.

What’s exciting about the upcoming wave of consolidation in the consumer internet space is that there will be many winners. Acquirers will survive and strive, targets will be able to innovate again, and consumers will get a better product. The danger would be if monopolies start to emerge as a result — but there is still some time for regulators to think about how to prevent this from happening.

Too Much Profit Can Doom Your Company

What defines success for a business? For most of the last century, it was profits. The leading enterprises of the world were ones that fashioned a profitable business model and leveraged it over time. Profitability as the key measure of business success was akin to a law of physics – like gravity – a foundational assumption which we all take as given: you have to deliver profits to create long term shareholder value. But what was once a natural feature of the competitive landscape has now become a trap for people and companies who are not able to adapt to a new landscape and change their focus.

Two big, well-known tech companies neatly illustrate this shift. Consider Microsoft under Steve Ballmer. The former CEO believes that delivering profits is the main measure of a company, and he’s justly proud of the $250 billion of profits Microsoft generated during his tenure over 14 years. Then consider Amazon, the first big company to deliver long term stock growth for the better part of two decades with essentially no profit to show for it. The contrast could not be clearer: Amazon – fearlessly making big, risky bets like a serial entrepreneur; and Microsoft, eschewing disruptive innovation in favor of remaining the “fast follower” it has always been, wringing profit from previously proven technologies.

Coming from a profitability-focused paradigm, it is not surprising that Ballmer was critical of Amazon, Microsoft’s Seattle neighbor, and its focus on growing and expanding its range of services instead of profits. From the old paradigm perspective, it was as if Amazon was attempting to defy gravity. But the contrast has come to favor Amazon. Many people in Silicon Valley see Microsoft as irrelevant today, while Amazon investors focus on its future growth. Profits appear more and more as a lagging indicator of yesterday’s innovations. Around three-quarters of Microsoft’s profits come from two extremely successful products that the company introduced in the 1980s and 1990s: the Windows operating system and Office productivity suite. As Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator wrote, “Microsoft cast a shadow over the software world for almost 20 years starting in the late 80s … But it’s gone now. I can sense that. No one is even afraid of Microsoft anymore. They still make a lot of money … But they’re not dangerous.” And that was in 2007.

Amazon keeps margins razor thin, as part of its mission to become the best place to buy just about everything. As CEO Jeff Bezos has said, “Your margin is my opportunity.” Amazon is maniacally cost-focused, but rather than letting benefits flow to profit, they pass them along to their customers. Also, Amazon needs to spend a lot as it grows its existing and new businesses. For example, as part of its same-day delivery service, it is dramatically expanding its distribution centers and hiring thousands of people in California and other states. It spends its earnings on creating and expanding new products (mobile phones, tablets) and continuing to build out Amazon Web Services (AWS). In 2006, AWS began offering IT infrastructure services to businesses in the form of web services – now commonly known as cloud computing. Today, AWS powers a growing universe of more than a million active customers in 190 countries around the world.

This can be very hard to do given the incredible pull of profitability in driving strategy. And therein lies the “trap”: a company’s success at generating profits can prevent the investment in innovation it needs. Profit-focused companies focus on scaling efficiency and cutting costs, and miss new opportunities. While Ballmer was focusing key resources on a new version of Windows (“Longhorn”) to defend Microsoft’s core product line, he missed big opportunities in search, social media, and phones. (Both the Bing search engine and the Windows Phone were just too late to mount serious challenges to Google, on the one hand, and the iPhone and Android, on the other.) Microsoft seemed to become rigid and bloated, and had difficulty with mergers and acquisitions. A friend of ours said recently, “In its early days Microsoft took more risks than a pirate; now they take less risk than an insurance company.”

A New Model for Growth

What lessons can we learn from Microsoft’s and Amazon’s differing emphasis on profits? How do you know when to focus your attention on defending a cash cow, and when to worry about winning in the future?

Despite its scale, Amazon still thinks and acts like a startup. It has maintained its openness to invention that was characteristic of its beginnings. It is focused on growth and continues to create new things. It is expanding its core business by increasing selection (the range of products it sells) and improving the customer experience (for example, Amazon Prime and next day and same day service). Here’s a rough illustration of this new model compared to Microsoft’s.

Microsoft’s model, which reflects its definition of success, revolves around profits. As our friend said, it wasn’t always this way – earlier in its corporate life, the Microsoft model no doubt looked very much like the Amazon one. But Amazon has found a way to sustain its more entrepreneurial model, growing its business at the edge, with services like AWS, and products like the Kindle and Fire. Amazon still has the founding phase zeal for creating and building. It measures its success by revenue growth and satisfied customers, not big profits.

High tech companies provide a useful laboratory to explore the tension between profit and innovation since high tech product lifecycles are short and shrinking. As companies like Microsoft succeed and grow to be very big, they tend to become stewards of the formulas that got them their success, and they focus on profitability. They milk their cash cows. But an excessive focus on profits can compete away investments that could lead to creating the next big thing.

Can Microsoft escape from the profit trap, recapture its founding spirit, and start taking more risks? Or does it feel there is no benefit to reducing margin on many of their products, as Amazon does, since it will not increase share? There are some interesting recent developments. The traditional shrink wrapped software business model surrounding Microsoft’s core Windows and Office products has been breached. Current CEO Satya Nadella seems to be inching forward by introducing more reasonably priced “Software-as-a-Service” (cloud) versions of Windows and Office, at the expense of profit. And it appears that Nadella has a renewed interest in taking risks and making big bets, such as the virtual reality HoloLens. Might Microsoft be willing to concede their traditional profit margins to win in this new category, effectively taking a page from the Bezos playbook? Time will tell.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers