Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1293

May 21, 2015

Measure Your Team’s Intellectual Diversity

Inventive thinking in a team setting is fueled by a blend of talents, skills, and traits that rarely all exist in a single person—such as an ability to see problems through fresh eyes, a knack for understanding a frustrated customer’s complaints, or a flair for turning a creative idea into a profitable innovation. This kind of intellectual diversity is more likely to be present when individuals on the team come from different disciplines, backgrounds, and areas of expertise. A choir can’t perform well if it’s made up of all sopranos; similarly, on an innovative team, you won’t achieve good results with people whose strengths and styles are all the same.

The most productive creative teams often exhibit characteristics that seem contradictory. For example, a group needs both expertise in relevant subjects and fresh eyes that can see beyond the established ways of doing things. Its members need the freedom to decide how to achieve goals while also having the discipline to work in alignment with the organization’s strategy. An innovative team needs to be both playful and professional, and it needs to be able to plan out a project carefully while also accepting that projects don’t always go as planned—and being willing to improvise when unexpected events arise.

To build a team that can navigate effectively among these different dynamics, you need to shape your group so that each individual brings a unique combination of knowledge and skills. You may need people with relevant experience within a specific industry, the ability to perform a particular technical skill, or a talent for writing or presentation. You’ll also want team members who excel in interpersonal dynamics such as building consensus, giving feedback, communicating in groups, and motivating others.

In addition to recruiting team members with a mix of skills and experience, you’ll want to include individuals with a blend of different preferred thinking styles, or unconscious ways of looking at and interacting with the world. There are many different ways to describe how people think. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, for example, divides thinking preferences into four categories:

Extroverted or introverted. Extroverts look to other people as their primary means of processing information. They quickly share ideas or problems with others for feedback. Introverts tend to process information internally before presenting their results to others.

Sensing or intuitive. Sensing people prefer using facts and hard data to help them make decisions. Intuitive people tend to be more comfortable with “big picture” ideas and concepts.

Thinking or feeling. Thinking people use logic and order to make their decisions. Feeling people are more attuned to emotional cues; their decisions are guided by the values or relationships involved.

Judging or perceiving. People who judge prefer having closure, with all loose ends tied up, when managing tasks and making decisions. Those who perceive are more comfortable with openness and ambiguity. They often want to gather more data before making a final decision.

Everyone exhibits all eight of these qualities in varying degrees, though we do have innate preferences. For example, a feeling person is not incapable of logical thought, nor is intuition absent in a sensing person. But a feeling person is more likely to respond emotionally to a problem before applying a logical lens, and a sensing person may prefer to make a decision based on hard data rather than on a theory. Preferences can also change in different contexts. You may have a tendency toward perception when visiting your child’s classroom but employ judgment when at jury duty.

Excerpted from

Innovative Teams (20-Minute Manager Series)

Organizational Development Book

Harvard Business Review

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

No one style is better than another, and each carries its own set of benefits to a collaborative discussion. The ideas and solutions that an intellectually diverse team generates will be richer and more valuable due to the wide variety of perspectives that inform them. Diversity of thought and perspective can protect your team from groupthink and can spark creative abrasion, a process in which potential solutions are generated, explored, and altered through debate and discourse.

Assess your team

Now that you understand what an innovative team looks like, think about your own group. If you’ve inherited an existing team or are newly embarking on the creative process with a group you already manage, take this opportunity to get to know each individual, assessing her skills and other elements of intellectual diversity.

The best way to get to know your team and assess its range of skills and experience is through conversation. It can be helpful to do this as a group, so everyone can learn what each team member brings to the table. Ask each person a few directed questions:

What’s your work history, both at this company and in previous jobs?

What’s your educational background? What did you study in college or for an advanced degree?

What strengths do you have, and what do others say you do well?

What are your passions and hobbies?

You may already know the answers to some of these questions, based on your prior experience with these individuals. But many of us have interests and experiences unrelated to our jobs. Tapping into these areas at work can kindle passion and introduce ingenuity. The sales manager who is interested in art history may be your best big-picture thinker. The sound engineer who used to work as a stage director might bring expertise to the management of the creative process. And the marathon runner can bring grit and commitment to your team, motivating others when times get tough.

Also ask about prior team experiences, which will allow you and the rest of the team to learn about people’s preferred work styles and different ways of thinking. For example:

What was your best team experience? Why? What did team members or the leader do to make it a good experience?

What was your worst team experience? Why? What behaviors made you frustrated or uncomfortable?

What do you like most about working on a team, and what do you struggle with?

How do you define a good teammate, team leader, and meeting?

What do you need from a team to do your best work?

You may not be able to meet every request or preference discussed, but understanding team members’ strengths and proclivities will help you bring out the group’s inventiveness as you progress through the creative process.

This post is adapted from the Harvard Business Review Press book Innovative Teams (20-Minute Manager Series).

Let’s Stop Arguing About Whether Disruption Is Good or Bad

Kenneth Andersson

The idea of disruption excites some people and terrifies others. Consider the recent case of The New Republic, in which a new, disruptive CEO came in and vowed to “break shit.” The company’s top journalists balked, the brand was sullied, and the business still struggles. And all that for what?

That was the essence of Jill Lepore’s essay last year in The New Yorker about the “disruption machine,” in which she argued that, “disruptive innovation is competitive strategy for an age seized by terror” and referred to startups as “a pack of ravenous hyenas” intent on blowing things up.

Most people over thirty have probably felt something akin to what Lepore described. Yet as I argued in my reply to Lepore, she presents a false choice between blind obedience to disruption and blind obedience to continuity. Clearly, neither is a winning strategy. In truth, successful disruption does not merely destroy, but creates a shift in mental models.

The primary target of Lepore’s attack was Harvard Professor Clayton Christensen, whose groundbreaking book, The Innovator’s Dilemma coined the term disruptive technology (later transformed into disruptive innovation). In her telling, he is the business equivalent of Mad Max, advocating for the destruction of the corporate order or, as she puts it, “disrupt, and you will be saved.”

You can see why Lepore is concerned. A “pack of ravenous hyenas” wildly intent on “breaking shit” certainly does sound menacing. Especially one empowered by a staid Harvard professor. Visions of the 60’s counterculture abound.

However, Lepore does Christensen’s work a tremendous disservice. A more thorough reading would reveal that he wasn’t, in fact, advocating for the destruction of the corporate order, but trying to save it. His research showed that once-successful firms often failed not because they lacked competence or conscientiousness, but because they were operating according to a defective model.

Since ancient times, from Aristotle to Ptolemy, leading all the way up to the present day, we have built working models to explain how the world works and we act on those models to solve problems.

Yet as Thomas Kuhn points out in his classic, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, we inevitably find that even the most successful models are incomplete. When an anomaly first appears it is usually treated as a “special case” and we worked around. However, at some point, we realize that the old theory is fundamentally flawed and that we need to shift paradigms.

Unlike Lepore’s disruptive “hyenas,” who revel in the destruction of the existing order, Kuhn noted that successful new models often include old ones. To illustrate the point, he offers the example of Einstein and Newton:

Relativistic dynamics cannot have shown Newtonian dynamics to be wrong, for Newtonian dynamics is still used by most engineers and, in selected applications, a great many physicists. Furthermore, the propriety of this use of the older theory can be proved from the very theory that has, in other applications, replaced it.

In other words, we use Newton’s model to create things like buildings and bridges and Einstein’s to create smartphones and GPS devices. Nothing has been subtracted, only added.

Following in the Kuhnian mold, Christensen points out in The Innovator’s Dilemma that there comes a time in which the practices derived from established mental models fall short. More specifically, he argued that when new competitors arose that targeted less profitable customers with a new business model, standard business practices—like those taught at his school—would fail to meet their challenge.

So Christensen’s work was in no way an attack, but in fact an acknowledgement of the shortcomings of his own profession. In essence, his point was that businesses that fail are often not the feckless bumblers they’re made out to be. Rather that by diligently following the precepts of incomplete models taught in business schools, they fall prey to assumptions that do not apply.

While Christensen’s ideas are noteworthy and important, they — like all models — are also incomplete and that, I think, is the source of Lepore’s confusion. While Christensen’s book focused on a specific type of business case, it also pointed to a much larger phenomenon that, when he first wrote it, was still in a nascent state.

Today, as Moisés Naím points out in his book, the End of Power, we see a great many disruptions today in politics, religion, and military affairs. At first glance these may have nothing to do with disruptive business models, but if we look closer we find that many of the same forces are at work: small groups, linked together by new technologies, and united by a common purpose can challenge even the most powerful institutions.

In the past, bureaucracies played a crucial coordinating role. It was through their vast control of assets that we were able to mobilize resources on a massive scale. Large institutions dominated because they could do what others could not. Yet now it is not control of resources that is important, but access to them. Digital technology enables relatively small actors to synchronize their actions through networks. Power, as Naím puts it, has become easier to get, but harder to use or keep. This is why we see disruption happening with increasing frequency, all around us.

This shift itself is apolitical, amoral. That’s why there can be both disruptors that set out to destroy, and disruptors that aim to create. The former are ego driven, seeking to replace the powers that be with a different version more to their liking. The latter are inclusive, working to create an alternative that outperforms the pre-existing model.

It’s not always easy to tell these two types apart. When an executive urges his team to “break shit” or “move fast and break things” he sounds more destructive than disruptive. So the question is not whether disruption itself is good or bad, but disruption in the service of what?

And that’s the difference between Lepore’s hyenas and the likes of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. Successful disruptors might break old models, but they build better ones that benefit us all, which is why we embrace, rather than fear them.

Your Presentation Needs a Punch Line

It was late Saturday night on Chicago’s North Side, and the historic Green Mill jazz club was buzzing with nervous energy. So was I. Pacing on the edge of the tiny stage, I gave my notes one final glance, exterminated the butterflies in my stomach, and stepped into the blinding spotlight. “Welcome to the inaugural edition of Mortified Chicago!” I shouted into the mic. “Tonight, real people will read their teenage diaries in front of you, total strangers. It’s an unusual experiment that’s equal parts comedic, cathartic, and, yes creepily voyeuristic!”

That was 2006. The first time I’d ever produced a live comedy show. Since then, I’ve helped hundreds of Mortified performers—ordinary, courageous people—turn extraordinarily embarrassing artifacts of their teen angst into professional bits of comedy. I also started to work at IDEO as a writer and marketing professional.

These days, most of my time is spent in conference rooms instead of comedy clubs, and the performers I coach are designers and consultants who want their ideas to land successfully with clients. I’ve found that many of the same storytelling approaches apply in either circumstance.

Since TED has upped the presentation game for business professionals, and PowerPoint-as-usual no longer cuts it, you may find them just as useful. Here are the five techniques I’ve found most applicable outside the comedy club. These come not just from my own experience, but also from my obsession with watching, reading about, and talking with comedians.

Take a bar exam. Unlike conference rooms, bars are friendly, social places. People expect stories told there to be succinct and entertaining. That’s why at IDEO, we tell our designers to “Take a Bar Exam.” Go to a bar with a colleague—or imagine you’re in one—and tell your story using only napkin drawings as your visuals. Have your friend repeat back your story to see what’s sticking and what’s not. Refine and repeat. Once you can keep his or her attention over “hecklers” like blaring TVs, you’ll be in good shape for sharing your presentation in a conference room.

Be immediately interesting. Any time you stand in the front of a room you’re saying, “Please be quiet. I’m very interesting,” which also happens to be Zach Galifianakis’ opening line in “The Comedians of Comedy.” People expect you to be prepared, confident, and interesting. That’s especially difficult if you’re nervous. “Do some light exercises before to raise your adrenaline (but not so much you’re sweaty),” advises Neil Stevenson, an IDEO Managing Director who coaches TED presenters. And instead of dribbling out a throat-clearing intro, stand up straight, project your voice, and nail the delivery of your opening lines. The first line or two set the tone for the rest of your presentation and put the audience at ease.

Find the “you” in your presentation. It can be hard to find the emotional core, or the “you,” inside of presentations on “robust product road maps” or “incentivizing customer loyalty,” but it can be done with a bit of story “therapy” similar to what we do with Mortified performers. Why should you be telling this story? What’s your unique POV? What are you passionate about? For instance, maybe the emotional drive at the center of creating a “robust product road map,” is your love of planning and belief in a new design direction for the company. Whatever it is, your story’s emotional core will give you credibility as a speaker and help you better connect with your audience

Simplify and exaggerate. Having a story unfold in real time in front of a live audience takes a lot of effort on the part of listeners. They have to hold many details in their heads simultaneously like characters, setting, plot lines, and so on, and they don’t have the luxury of rewinding or rereading. To make it easier, ditch unnecessary details and business jargon, supply sensory details (sight, smell, sound, touch, taste) to make your story more immersive, and exaggerate the main points to make them more unexpected. Or as I tell Mortified performers, “Pretend I’m a drunk college kid in the back row and tell me your story.”

Close strong. “If people don’t know a joke’s over,” says Chicago comedian Adam Burke, “it’s not a joke.” Why do you think a punch line’s called a punch line? People instinctually crave strong, simple resolutions to stories. Weak endings such as, “Well, it looks like we’re out of time” are the storytelling equivalent of falling offstage. They leave an audience feeling unsettled and zap a room’s energy. When in doubt, refer back to your opening lines to bring your story full circle.

This final piece of advice is less a stage trick and more of a mental shift. Start subbing “performance” for “presentation,” even if it’s just in your head. This simple reframing will automatically help you deliver a story in a more entertaining, engaging way.

May 20, 2015

Secret’s Problem Wasn’t Trolls

At the end of April, the Silicon Valley startup Secret opted to return a bunch of venture capitalists’ money and shut down. Secret had created an app that allowed its users to share anonymous thoughts. They raised more than $35 million and were covered by every major tech publication, as well as some mainstream outlets.

Although Secret did its best to close quietly, the controversial company was bound to attract postmortems, including an op-ed in the New York Times that blamed “cyberbullying” and “novelty.” Most of these postmortems are rife with misunderstandings of the startup ecosystem, social media, and digital anonymity. For instance, many commentators are claiming that Secret failed because anonymous sharing platforms can’t work. They ignore anonymous sharing platform YikYak, which has two million users and $72 million in venture capital, and competitor Whisper, which has ten million users and $61 million.

I’ve lived and worked in San Francisco/Silicon Valley tech for several years now, and for much of that time, I used Secret with my friends. I also have significant experience developing anonymous and pseudonymous digital identities; last year, in The Atlantic, I wrote about how I used social media to build a pseudonymous blogging brand. Drawing from my experience in the space, and from other Secret users’ commentary around Silicon Valley, it’s obvious to me that Secret failed due to ill-considered product decisions — it did not fail because of anonymity, cyberbullying, or other buzzwordy critiques.

As the Internet has become civilized (one might say colonized), there’s been a strong backlash against digital anonymity and pseudonymity. Lately, commentators often cite cyberbullying and trolling as reasons to enact “real name policies.” But there’s surprisingly good evidence that real name policies do not, in themselves, make lasting improvements to the civility of online discourse. For example, as tech journalist Greg Ferenstein back in 2012, the entire country of South Korea has passed multiple laws intended to enforce real name usage on digital media. Yet after several years of attempts, the laws were ditched because they didn’t meaningfully reduce abusive and malicious comments.

This is not to say that cyberbullying and trolling aren’t real problems. Indeed, these are problems that can destroy communities, unless they are addressed by moderators with specialized skills and tools. But those problems are not unique to platforms that allow pseudonymity and anonymity. Plus, anonymity platforms have a lot more going on than vicious gossip — including concrete business applications.

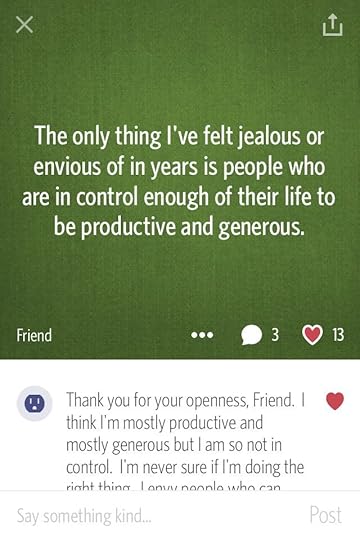

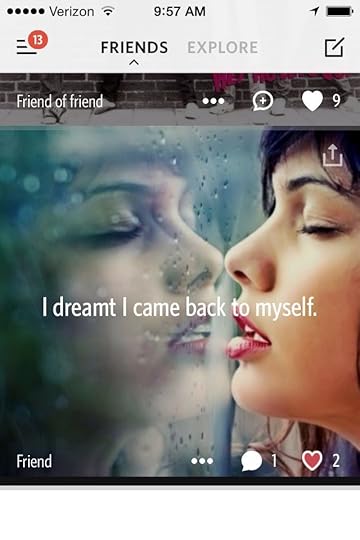

In other words: Secret was not a wasteland of spite. During 2014, I took many screenshots of Secret, some of which you see in this piece. I’ll use these screenshots to give you a sense of my experience on the platform, and then I’ll explain why Secret’s product decisions killed the company.

As you can see, the secrets of Secret were tagged with “Friend” (meaning the person was among my cell phone contacts) or “Friend of friend.” My friends used Secret to share tiny, poignant moments. Occasionally, they scheduled dinner parties. These sweet moments get lost when people focus on the seedy, salacious side of Secret.

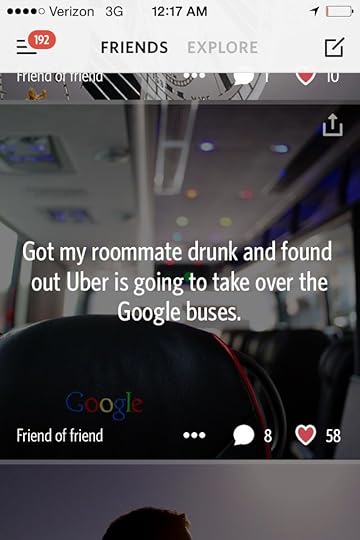

And what was the salacious side? There was the inevitable sex, drugs, and money talk, including plenty of tech industry gossip. But some of my favorite “industry gossip” from Secret demonstrates its users’ knowledge that none of us could trust what we saw there.

These clearly fake “rumors” showcase Secret users’ collective understanding that anything we saw there could be a lie. In general, we traded a lot of jokes on Secret — jokes about our lives, our work, and about Secret itself. Yet in the midst of this madness, tech employees managed to discuss important but taboo business topics, and to share information under the veil of plausible deniability.

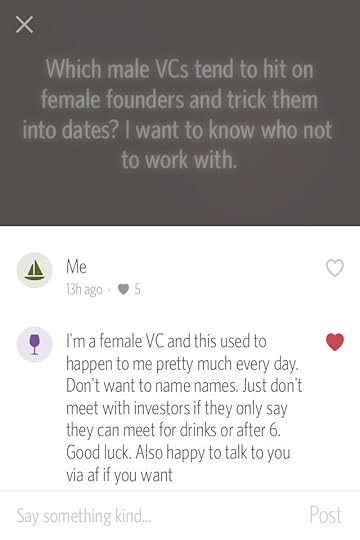

Take this secret as another example. Was it true or false? I don’t know, but if it was true, then this was valuable information for everyone involved.

There were many Secret threads where users traded advice and anecdotes about salaries, workplace norms, and tough negotiations. On one memorable occasion, a user posted that the company she co-founded had been acquired by Google, yet Google had hired everyone but her. She then noted that she was the only woman of five co-founders. The secret went viral and eventually reached journalist Kevin Roose, who managed to get in touch with the author. He confirmed her identity, then wrote up her story in New York Magazine. As Roose explained at the time:

The Secret thread quickly became the talk of Silicon Valley. It was seeming proof that even within the happy-go-lucky world of tech start-ups, there are winners and losers, and more often than not, the losers in situations like these are the designers, who are more likely to be female than their engineer counterparts, and whose “soft” skills are seen as less valuable than coding chops. … Making offers to four-fifths of a company as part of an acqui-hire, while legal, is nearly unheard of in Silicon Valley, where mergers and acquisitions are still generally governed by a certain type of decorum.

Just in case this isn’t making Secret’s value clear, here is a final shot from my collection:

Here, one user seems to need advice about male VCs who trick female founders into going on dates. In response, another user offers thoughts on how to avoid such men, then goes the extra mile and offers more advice in private (over an external anonymous messaging platform called Anonyfish). This demonstrates how Secret formed an important safe space, even while being laden with ridiculous comments (like “Me”).

In short: Secret enabled users with a sufficiently rich network to ask a bunch of their social connections for help, quickly and in relative anonymity. Of course that made it useful for scattered groups handling stigmatized, socially complex problems — such as female founders attempting to raise money in a pressure-cooker environment where they are marginalized, they are never supposed to complain, and the occasional powerful man will want something quite different.

To be clear, Secret was not always fun. Scrolling through the feed was sometimes stressful, and I occasionally uninstalled the app and took a break after reading things that left a bad taste in my mouth. But commentators who discount Secret’s rise and fall with buzzwords like “cyberbullying” and “novelty” are doing the platform a huge disservice.

So what really happened to Secret? No one knows for sure, but many users have observed that the company changed the product frequently and drastically. A number of Silicon Valley insiders have offered thoughts about the moments they themselves stopped using Secret, which often coincided with big product updates and feature changes. One person used the phrase “death of a thousand cuts” as a metaphor for how Secret “revised itself into obscurity.” (Full disclosure: I have done contract work for Quibb, the media platform hosting the conversation I linked above.)

For instance, in response to concerns about cyberbullying, Secret users’ ability to post custom photos — a popular feature that they later added back. That was a big change in itself. Yet in the same product update, Secret introduced a completely new polling feature, which proved unpopular and was quickly removed. (Interestingly, Facebook and LinkedIn have both developed and then removed polling features, which suggests that social media polls seem like a great idea in theory but are hard in practice.)

Shortly before the startup folded, Secret re-hauled its product to be more like the anonymous chat app YikYak, which is currently popular with college students. The changes were fundamental, and some cite them as the final nail in Secret’s coffin. As the tech publication Re/code put it, Secret became “unrecognizable” — it “looked like a lot of another anonymous chat apps.” Around the same time, Secret’s co-founder and Chief Product Officer left the company.

As a general rule, useful product changes can be unpopular at first, but Secret made so many unpopular changes that it’s hard to imagine the process behind them. How were those decisions made? Were they grounded in careful user research? From outside the company, it doesn’t seem that way. After creating such a popular product, Secret could have slowed down, and they could have carefully gauged each change separately. Instead, they seemed to overreact to media criticism and successful competitors. They moved too fast, and they broke too many things.

The lesson of Secret is not to stop building anonymity-focused media tools — again, Whisper and YikYak are doing very well. Nor should we conclude that the product failed because it was a fad and everyone got bored.

Instead, the lesson is do thorough and continuous user research while developing a product. As a product begins to succeed, the team ought to be cautious in pivots, ensuring that they consistently respect and express the central value that users find in their product. Identifying a famous product’s true value among the noise of pundits, detractors, funders, and superfans can be challenging — but it’s crucial to a company’s long-term success.

Editor’s note: The author would like to thank Alex Kawas for his feedback on the first draft of this piece.

Focus on Winning Either Hearts or Minds

We’ve all heard the axiom that to persuade others effectively, we have to win both the hearts and minds of our audience. For people who are naturally persuasive (or overwhelmingly charismatic) this comes naturally. The rest of us have to cultivate the ability to persuade others. All too often winning hearts and minds feels like a paradox. Why? People are complicated and so are the problems we’re solving. Trying to leverage both emotion and logic can actually make us less influential if we don’t have a plan.

In my work as a business adviser, I help leaders simplify their approach to persuasion by identifying which lever (winning hearts or winning minds) is most important in a particular circumstance to gain the trust of others and influence their perspective. In most situations, you’ll use both tactics, but identifying which one is likely to be the most compelling up front provides a strong foundation for your argument.

Winning Hearts

The art of persuading by winning hearts is about connecting people emotionally to your idea or position. In any persuasive dialog, you need to connect with others to some degree. However, this approach is highly effective in certain circumstances such as:

Introducing a new idea and trying to pique interest.

Gaining support for a decision that’s already been made.

Raising the bar on performance or commitment.

Leading a team that is struggling with discord or conflict.

Aligning with creative colleagues, like those in design or marketing.

The best method of persuasion in these circumstances is to connect with people on a very personal level. This is often referred to as a “hook.” Use vivid descriptions and metaphors to draw others into your vision. Share personal stories and experiences to demonstrate that what you’re suggesting is the right choice.

Let’s say you’re announcing a big reorganization to your team. Your message might go something like this:

“I know this announcement may be unsettling for you. Changing any aspect of your work process while you’re this busy is challenging. But I hope you’re also excited about the change, and let me tell you why. Our new organization has been designed specifically to address some of the challenges our teams have struggled with for years: conflicting priorities, lack of alignment on goals, and disjointed processes that get in the way of your success. Our teams will finally not only be in the same boat, but also rowing in the same direction. The destination? Achieving our 2015 results. Imagine how great it will feel when we hit our targets — when we crush the competition and claim the market share we deserve? Every one of you plays a key role in that victory. This new organization will make it easier for us to win, individually and as a team.”

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

Make sure you highlight what’s in it for them personally if they adopt your perspective or make a change. What fears can you address to build trust and cultivate a feeling of safety in supporting your position? What motivations can you tap into to create alignment? Where can you find common ground to unite viewpoints? You still need a logical, well-informed message; but you are at your most convincing when you first appeal to the perspective, fear, or motivation of your audience.

I’ve found that the most effective way to win others’ hearts is to share why your idea is important and why now is the time to act, and then to highlight how it benefits the individual, the business, your clients, your partners, or the broader environment. Transparency and authenticity drive success here.

Your goal in winning hearts is to make whatever you have to say matter on a personal level. Of course, it also has to make sense. And this is where winning minds comes into play.

Winning Minds

The science of persuasion lies in winning minds with logical, well-articulated positioning and analysis in favor of your idea. If you’re trying to persuade anyone of anything, you certainly need a logical argument to support your perspective. But sometimes this is particularly important to do well — and first. Winning minds is almost always the best option when you’re:

Trying to change direction on something previously decided.

Advocating for one choice over another in a decision-making process.

Helping an overwhelmed team stop over-analyzing and see a situation clearly.

Addressing a highly complex or technical set of problems.

Asking analytical, financial, or executive types to agree with your perspective.

To win the minds of others, carefully construct your message. Start by describing a situation everyone can agree is worth discussing, including both what it is and why it warrants attention. Establish common ground. Share your expertise and understanding of the issue at hand, highlighting analysis you’ve done or consultation with others. Provide proof to support your position in the form of data, research, expert opinions, and analysis. Discuss benefits in very tangible ways.

Here’s an example of the kind of message you should craft to win people over with logic. Let’s say you’re suggesting a product change:

“Today I’d like to talk with you about Product A. We launched the product with the expectation that customers would embrace new self-service features, and in turn, we would lower our support costs, further strengthening our market position. Our strategy was, and still is, innovative and viable. That said, we’ve learned that customers like the new features, but our support costs haven’t declined by 5% as expected. In fact, they’ve increased by 2% quarter-over-quarter as we trained customers on how to use the new features. The team has an enhancement that will allow us to provide customers with even more self-service features while lowering our support costs over time. A cross-functional team has analyzed outcomes and assessed our risk to be low. Early indications of our ROI suggest that we’ll show margin improvement exceeding our original plan within twelve months by implementing three key changes to the product. If we gain approval for this plan today, we will have this enhancement to market in 90 days with a net-positive effect on our financials by year-end.”

To get your framing right, imagine that you’re a trial attorney offering your opening argument and proceeding to make your case. To do it well, you have to put yourself in the mind of your jury. What do they believe to be true today that you intend to challenge? What did they want to do before talking with you, that you now want them to revisit? Is history informing their current judgment and, if so, how can you challenge it effectively? How do they measure success, and does your proposal support their success or put it at risk? What concerns will they have, and how can you address them in advance?

To win minds, you have to do your homework. Often you have just one chance to influence others. Put yourself in their position and do the work to prepare. If possible, you’ll also want to relate your proposal to what matters personally using the tactics outlined in the section on winning hearts.

Putting It All Together

The paradox of persuasion doesn’t have to get in the way of influencing others effectively. Giving equal weight to emotion and logic can make you less convincing, so pay careful attention to your audience and the task at hand. Identify your strongest position based on the circumstances. Is it most important to appeal to people’s hearts or minds? Be thoughtful and prepare with intention. Learn the right methods and before long you’ll be winning both hearts and minds with ease.

How to Earn Respect as a Leader

In this adaptation from his new book, the CEO of Red Hat, Jim Whitehurst, shares advice for how to build credibility in an organization — especially if you are new to it, have a different background than others on your team, or are not in a position of authority.

How would you be perceived in your organization’s meritocracy? Ask yourself if you command respect because people have to respect you or, rather, because you’ve truly earned respect. Many people aspire to titles because that forces others to respect them. But, to me, this is the lowest form of respect, especially if the person you’re receiving respect from is more junior than you or works at a lower rung in the bureaucracy. Respect has to be earned. It’s not about a title.

When people respect you only because of your authority, they will give you the minimum effort. Some incredibly brilliant people have earned respect because they are so smart, but most people aren’t incredibly brilliant. So how do you go about it? There are three ways:

Show passion for the purpose of your organization and constantly drive interest in it. People are drawn to and generally want to follow passionate people.

Demonstrate confidence. Many people in positions of authority don’t show confidence well, especially with their team. It’s one thing to convey confidence to your own boss, but it’s just as important to share that same confidence with those who report to you.

Engage your people. Trust has to be earned, and it’s not enough to call a meeting and tell people what to do and then retreat behind your own closed door. You also need to be open about your weaknesses and ask the team to help you address them. Nobody expects perfection, so don’t hold your cards too close; get your team to work with you.

Joining Red Hat posed a challenge for me — would I be trusted and respected as a leader? While I had considerable leadership experience and a degree in computer science, I had no background in enterprise IT. In a very open, interactive culture like Red Hat’s, there was no way for me to fake it. However, I found that being very open about the things I did not know actually had the opposite effect than I would have thought. It helped me build credibility. My team learned that I wouldn’t feign knowledge where I did not have it and therefore was more likely to give me the benefit of the doubt when I did talk confidently. No one expects leaders to know everything all the time, but we do expect our leaders to be truthful and forthright.

Owning up to what you don’t know is an important way to build trust. But it’s just as important to be able to contribute your knowledge and expertise in a way that’s more about the community and what it needs than it is about you and your ego. At Red Hat, one of the greatest insults or blows to your ego comes when you put something on one of the internal discussion threads and receive nothing back—neither positive nor negative. “That’s the worst outcome, truly,” Kim Jokisch, director of Red Hat’s employment branding and communications team, told me. “That means they’re likely ignoring it, which means you’ve failed in some way.”

Even so, the goal is not simply to generate posts and responses. That’s not what builds your credibility. Rather, it’s all about your true purpose. “People smell out intention around here,” says Emily Stancil Martinez, a member of Red Hat’s corporate communications team. “If your intention is just to stick your nose into every little thing so you can be front and center, people see it and will take note. But if you are thoughtful when you weigh in, in order to make a real contribution for the greater good, that’s what truly builds your credibility and raises your profile.”

Adapted from

The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance

Organizational Development Book

Jim Whitehurst

30.00

Add to Cart

Save

Share

But having the patience to build up that level of credibility can be frustrating to someone who joins the team. A new hire — especially someone who hasn’t already built a reputation in the open source community — simply won’t have the same level of influence. It doesn’t always seem fair, and some good ideas are likely never heard as a result. An enthusiastic new hire may join the company with the thought that his ideas will be heard equally, only to fall into a rut when he feels as if his good ideas are ignored. That can quickly lead to a disengaged employee who either leaves the company or, worse, becomes a cultural naysayer. Part of the solution is to set expectations so people know that earning a reputation takes time and hard work. It’s as if you want to sell something on a site like eBay: without any history or reputation score, you can find it far harder to locate buyers interested in what you’re selling. That takes time, patience, and a commitment to working at building your reputation, which isn’t something everyone enjoys doing. To make the process easier, here are some tips:

Don’t use phrases like “the boss wants it this way” or rely on hierarchical name dropping. While that may get things done in the short term, it can curtail discussion that’s core to building a meritocracy.

Publicly recognize a great effort or contribution. It can be a simple thank-you e-mail in which you copy the whole team.

Consider whether your influence comes from your position in the hierarchy (or access to privileged information), or whether it truly comes from respect that you have earned. If it is the former, start working on the latter.

Proactively ask for feedback and ideas on a specific topic. You must respond to them all, but implement only the good ones. And don’t just take the best ideas and move on; take every opportunity to reinforce the spirit of meritocracy by giving credit where it’s due.

Reward a high-performing member of your team with an interesting assignment, even if it is not in his or her usual area.

This post has been adapted from The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance.

4 Business Models for the Data Age

Organizations have always depended on data — to manage operations, to communicate with customers, to pay employees and suppliers, to plan their futures, and so forth. Those with the best data have enjoyed distinct advantages — in commerce, for example, better understanding the market leads to better products offered at better prices, and so forth. Data has enabled strategy, but, with few exceptions, neither driven strategy nor sat at its heart.

That’s changing. Data is invading every nook and cranny of every sector, every company therein, every department, and every job. As it does, it’s flexing its strategic muscles, and four ways to compete with data are starting to emerge.

The first involves cost reduction through improved data quality. Too much data is not up-to-snuff, and it wreaks all sorts of havoc — the drone strike that killed an American and an Italian because no one knew they were there is one spectacular example. Fortunately, most data quality issues are more mundane, but in aggregate they add enormous cost as people and departments check and correct data that just doesn’t look right before making a decision; reconcile data from sources that employ similar, but not quite-the-same, data definitions; and fix mistakes — rerouting packages that were sent to the wrong address, correcting customer bills, and redoing decisions gone wrong.

In a nutshell, improving quality takes those costs out, largely by creating data correctly the first time. The sums can be enormous. AT&T, for example, saved tens of millions yearly in a single department and company-wide, giving it a great advantage.

Improved data quality also lies at the root of the second strategy, which I call “content is king.” This strategy aims not to reduce internal cost, but to provide additional, more relevant, or newer data to the customer. There are at least three types of content providers.

Pure content providers, which capture new or novel data, or data that simply had not been captured before, and build a business around it. These businesses include Bloomberg and Morningstar, which provide data about financial markets. Uber is another example. It found a way to connect “I need a ride” and “I’m looking for a fare,” and provide a service that people love. Similarly, Fitbit counts steps and provides some simple summaries that help people better manage their fitness. I expect an almost limitless parade of such opportunities as drones, the Internet of Things, and nanotechnologies create data only dreamed about a few years ago.

Informationalization of existing products and services, where you build in data that customers need. Route guidance, based on GPS in cars, and the mountains that turn blue on a can of Coors when the beer is cold are classic examples. The strategy appears quite profitable — some years ago Wired magazine predicted that, by 2010, half the value in the delivery of a shipping container, from half-way around the world, would lie in the data associated with the contents. My friends in the industry tell me that bogey was met by 2005.

Infomediation, where you do not to create new data per se, but mediate the exchange, helping people find the data they need. Think Google. There will be lots of mediators; after all, more data means more data to exchange. For example, I view much of the data about myself as mine. Any number of companies would like that data, and I’d be happy to provide it to some, at a price. But how, and at what price? I’ll love the company that mediates on my behalf!

“Building a better data mousetrap” — or data-driven innovation — is the third way to pursue competitive advantage through data. Indeed, discovering a game-changing relationship previously hidden in the data and using big data and advanced analytics inspires data scientists everywhere. More practically, the strategy aims for a series of small discoveries, a few larger insights, and, maybe, just maybe, the occasional big one. The strategy has deep roots in science and is beginning to prove itself across a broad spectrum. Insurance companies are developing new understandings of risk, retailers are better stocking their shelves, and human resources is finding new sources of talent, just to name a few.

Finally, the fourth strategy is to become increasingly data-driven, in everything one does. Academic research suggests that the strategy is very profitable. To simplify just a bit, the idea is that everyone — individually and in groups, up and down the organization chart, across internal silos, and with business partners — makes better decisions by using more and better data. Since the data can only take the decision-maker so far, they must learn to combine that data with their intuition. Everything is just a little better as result.

Of course, competing through lowered cost, providing better products, and innovating are nothing new. Similarly, managers have always strived to make better decisions. Driving these efforts with data, however, is new. And for most, data is an unfamiliar asset, with different sorts of properties. It will take real effort to relearn these strategies. But the benefits could be huge for your business.

May 8, 2015

You Can’t Move Up If You’re Stuck in Your Boss’s Shadow

Having a good boss — someone who stands up for you, who buffers you from interoffice politics, and who competently represents your team to the rest of the company — is a wonderful thing. Except when it’s harmful to your career. If you aren’t visible to others in the company, you’re unlikely to have a strong network, expand your influence, and move up in the organization. How do you come out from behind your boss’s shadow?

What the Experts Say

It used to be that the surest path to career greatness entailed “hitching your wagon to a star manager — as your boss rose, you rose too,” says Priscilla Claman, the president of Career Strategies, a Boston-based consulting firm and a contributor to the HBR Guide to Getting the Right Job. Today, things are different. “Attaching yourself to someone who has a bright future is not the best strategy for getting ahead,” she says. For one, people change jobs more than they used to, which means you can’t predict where your boss is going to end up. For another, your company could alter its management structure or change directions. “And your boss may fall out of favor,” Claman says. “The only way to survive that is if you have relationships across the organization and are seen as credible on your own, not just [someone] who’s ridden your boss’s coattails.”

Putting aside a worst-case scenario, being seen as just your boss’s right-hand man can also be “detrimental to your career in the long run because nobody but your boss appreciates what you can do,” says Karen Dillon, coauthor of How Will You Measure Your Life? “You need others to know your value, and understand where you fit in the organization.” After all, she points out: decisions on raises, promotions, and bonuses are rarely made by your boss alone. Here are some strategies for how to make that happen.

Recognize the problem

Even when you have a good relationship with your manager, it can still be a struggle to make your mark. The problem is often that one, you’re not visible to others in the company — perhaps because your boss does not give you public credit for your contributions — and two, you don’t have a big enough network on your own. A good litmus test for determining whether you are in your boss’s shadows is to ask yourself: Can I name three people outside my department who understand what I do and what I’m good at? You may have plenty of surface-level relationships with other folks at the office, but the mark of a good network, according to Dillon, is “at least three people—at your level and above—who can describe your job and the value you bring to the organization.” Of course it’s also important to know colleagues who sit beneath you on the org chart, but peers and senior managers are typically “the ones who can pull you into interesting projects and open doors for you,” she says.

Ask your boss for help

The best-placed person to increase your visibility at the company and expand your network is your boss. So, make the request. Ask your manager to publicly recognize your contributions at high-level meetings so that others will begin to recognize your value. And ask for help connecting with colleagues across the organization. Preface the conversation by saying something like, “I love working with you and I want to talk about how I can continue to grow and find opportunities to learn new things” and meet new people, says Dillon. By beginning this way, she says, “you’re implicitly saying, ‘I want to represent you, but I also want to broaden my horizons.’” Then ask your boss, “Who should I get to know better?” And, “Who would be valuable for me to connect with?” “If you work for a big company, ask your boss to make an introduction — you’re looking for a blessing and endorsement,” she says. “Your boss should want you to develop your own reputation because that enhances his reputation as well.”

Seek new and different opportunities

“If you’re viewed as a mini-me of your boss, you need to identify opportunities to differentiate yourself,” says Claman. Offer to help with a project that will increase your exposure to new parts of the company. Serve on a focus group to assess a new vendor or benefit options. Volunteer for a committee that will include people from other functions and departments. “If, for instance, you hear about a newly formed task force, tell your boss you think it would be a good idea for you to represent your department on it.” Your boss will be unable to turn you down if you volunteer in a meeting where others have heard you volunteer, or if the request is an important administrative priority, says Claman. To get your boss to say yes, “You have to show the value to your boss, your department, and your organization,” she says.

Speak up in meetings

Expanding your relationships at work and increasing your interaction with senior management requires you to make concerted efforts to raise your profile. Ask your boss if you can sit in on an important meeting with higher-ups; ask the marketing team if you can tag along on a sales call with a prominent client. “Before the meeting, ask your boss if there is anything he’d like you to prepare,” says Claman. And during the meeting, make yourself useful. “You’re there to learn,” she says. “Offer to take notes and then afterwards, distribute the notes under your name.” Don’t interrupt your boss and “don’t undermine what he’s saying, but look for opportunities where you can chime in and display your knowledge and expertise in a way that genuinely enriches the conversation,” adds Dillon. Share your ideas. Offer your opinion. And use the “we” pronoun, she says. Your comments should “reflect the work you did with your boss.”

Socialize with your colleagues

If you want colleagues to get to know you better and to see you as your own person, you need to put yourself in a variety of professional and social situations. “Look for places where you can establish a personal connection with the people you work with,” says Claman. Take advantage of informal opportunities — in the cafeteria, through the company softball league, or through a charity run. If your office doesn’t have philanthropic activities, consider organizing one. At formal occasions, such as the company holiday party and the office picnic, you need to make a concerted effort to socialize. Even if these events are not your thing, it’s important to go and “make it your mission” to connect with people outside your typical work orbit, says Dillon.

Be patient

“Sometimes the real world moves more slowly than you would like,” says Dillon. Establishing a reputation independent of your boss takes time.” If you’re feeling frustrated by the pace of your career and are worried about being forever in the shadows of your manager, ask yourself: Am I growing? Am I learning? Am I enjoying what I’m doing?

Principles to Remember

Do

Ask your boss to introduce you to others in the company

Volunteer for projects and committees that enable you to meet new colleagues and learn new skills

Make an effort to socialize with coworkers and get to know people on a personal level

Don’t

Be a wallflower in high-level meetings; look for opportunities to display your expertise

Be afraid to apply for jobs and opportunities that would take you away from your boss

Lose sight of the fact that establishing your own reputation sometimes take longer than you’d like

Case Study #1: Volunteer your time and expertise

Laura Troyani had a good job in marketing research at a consumer products company in the Boston area. Her colleagues were professional, and her boss — the head of the department — was a “great manager” whom she “learned a lot from.”

But the work — more advisory than direct marketing — did not excite her and Laura knew her career path would be limited if she simply followed in her boss’s footsteps. She felt in the shadows and knew she needed to not only expand her skillset but also to broaden her network.

She took matters into her own hands. Laura set up a meeting with the leader of the broader marketing team. “I told him that I loved the company and had some extra time on top of the job I was doing, then asked if there were any side projects I could help out with.”

Her boss signed off and Laura started helping out with a couple of the marketing group’s data-oriented projects, which complemented work she did in her primary role. Laura enjoyed the experience and through that formed new professional relationships with the sales team.

In addition, Laura, a self-described “a natural introvert” forced herself to participate in social activities at work. She played in the company’s softball league and joined its dodgeball team.

A year later, after an internal restructuring, a position opened on the consumer marketing team that called for someone with a quantitative background. Laura was the perfect fit. “It ended up being the slam-dunk job I really wanted,” she says.

Today she is the marketing director of TINYhr, the Seattle-based company that makes employee engagement software.

Case Study #2: Capitalize on opportunities to offer your ideas and insights

Connie Bentley left her career in teaching for a sales job at a large business services corporation. She excelled in the new role and was soon promoted to district sales manager covering Connecticut and Massachusetts. But after three years, she had twice been passed over for a regional manager job.

Connie’s boss was a “good guy” with whom she had a “candid” relationship. “I asked him what I needed to do to be considered for regional manager and how I could bring more value to the company.”

Scott’s advice was not particularly helpful. “He told me that I already brought value to the company and that I needed to keep doing what I was doing,” she recalls.

Connie was dispirited and considered quitting. “When you’re feeling stuck or in the shadows, you think the only way out is to leave the company,” she says.

But just as she was starting to dust off her resume, she was invited to a recognition dinner for top performers. Fortuitously, she was seated next to the president of her division. He praised her for having done well at the company and asked how the company helped make that happen.

Connie wanted to make a good impression, but she decided to be respectfully frank. She told him that while the company had helped her progress, it could have done a lot more. “I gave him some ideas: a formal boot camp for rookie sales people, or a safe practice environment where they could learn-by-doing before going out on calls.”

Soon after that dinner, the division president called her to ask if she’d be willing to move to New York City to become the company’s first sales training and development manager. “I said I wanted the job, but first, ‘Have you spoken to my boss? And is he okay with this?’”

Scott signed off on the move. Today Connie is based in San Francisco as the US General Manager for Insights, the global talent development firm. “That job got me into the field where I belong,” she says.

A Way to Gauge How Well Your Company Is Really Performing

Do you have an accurate sense of how your company stacks up?

Figuring out a company’s relative performance is ferociously problematic. It depends on which other companies are included in your comparison. Just change the peer group, and a laggard becomes a leader, or vice versa.

And if a company’s relative performance is in doubt, so are its goals, because the two are tightly linked. When Jack Welch was CEO of GE, he famously tasked each business with achieving number 1 or number 2 status in its industry, a goal-setting principle that echoes across the decades. But applying this benchmark effectively requires choosing a comparison group, and there are two challenges that inevitably crop up: what we call the “microscope” and “telescope” problems. That is, you get a meaningless result if you look at too small a comparison group, and an equally meaningless answer if the sample is too large and heterogeneous.

For example, what if your industry has just a few key players, and they’re perennial poor performers? Is it wise to compare yourself only with them? And what about size? Can you measure your organization’s performance against firms whose annual revenues are orders of magnitude different? And then there’s the time factor: Does being “number 1” this year offset years of poor results? What about the effect of macroeconomic ups and downs?

With questions like these in mind, we recently set about developing a benchmarking method that would give executives the ability to solve both the microscope and the telescope problems, allowing them to compare their companies against a very large sample, but on a more-or-less equal footing.

How is this possible? Our method relies on specialized regression analysis, which is designed to correct for company-specific factors that affect performance. It also is designed to assist you in identifying your company’s percentile rank among all publicly listed U.S. companies, as if yours and all the other firms were roughly the same size and in approximately the same industry.

We believe that the method, which has been published in a top peer-reviewed journal, is statistically sound. Best of all, it’s easy to use. Any company, public or private, in any industry, can access our method via a simple online tool to begin to evaluate its performance. The tool is accompanied by a detailed technical note.

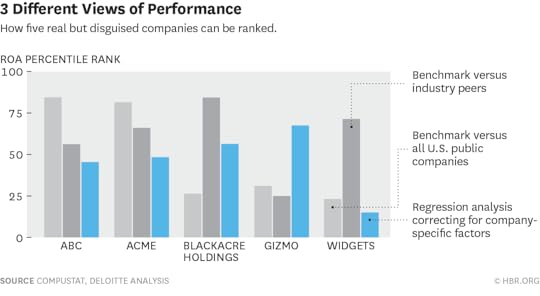

The approach yields some revealing results, especially as compared with more widely used methods. We’ve plotted five randomly selected companies’ 2013 ROA rankings according to three methods: a comparison with the overall market, a comparison with industry peers, and our statistical method. The data points are percentiles, which show the proportion of companies with worse performance (so if a company is in the 90th percentile, its performance is better than that of 90% of others in the comparison group).

We’ve changed the companies’ names, but the data points are real. ABC and Acme appear to be doing quite well relative to the market: If you make a simple comparison, they’re around the 80th percentile. But once we apply our method to correct for industry, size, and long-term performance, it becomes clear that they’re little better than middle-of-the-road.

By contrast, if Gizmo compared itself with its closest peers, its leaders would probably conclude that urgent improvements are needed. But our method shows that the company is doing quite well, given its circumstances. Finally, Blackacre and Widgets do well in their industries but poorly versus the markets.

These five companies are not outliers. For the full population of U.S.-based, publicly traded companies, the average absolute difference in percentile rank between our method and the more common approaches is between 18 and 25 percentile ranks for both profitability and revenue growth. That means it would be typical for a company that considered itself to be in the top quarter of its peer group to be, based on our statistical approach, no better than average. Or for a company’s simplistic benchmarking approach to mask, in part, its excellent performance.

Think about that: You might discover — to your surprise — that your company is a standout.

And you wouldn’t be alone. To probe corporate leaders’ sense of where their companies stand, we polled 301 executives from large, U.S.-based corporations and asked them to report a recent performance figure (ROA of 5%, for example) and estimate that data point’s meaning in terms of percentile rank, taking into account their companies’ industry and size. We also plugged each data point into a version of our statistical model.

When we compared the results, there was little correlation between the executives’ percentile estimates and our statistical findings. These results closely parallel two earlier survey efforts we undertook. With more than 800 executives polled overall, we have seen little evidence that business leaders can readily assess their firms’ relative positions.

Setting corporate financial goals isn’t simply a quantitative exercise in prediction, of course, and it never will be. Goals are aspirational. Ideally they reflect a healthy tension between what a company can achieve and what its key stakeholders want it to achieve. Yet goal-setting inevitably begins with an answer to the question “How have we done so far?” Goals mean little if a company lacks a clear understanding of how the organization stacks up.

The potential downside from getting it wrong is significant: Underestimate your performance and you risk setting your sights too high, whipping a horse that’s already running as fast as it can. Overestimate your performance and you could end up settling for a lazy canter, when there’s a full gallop to be had.

How New Technologies Push Us Toward the Past

Reading all the stories and hearing the rumors about Apple’s autonomous vehicles, Google’s drones, and Amazon’s experiments with new delivery systems, it’s easy to imagine looking out your window in a few short years and seeing a world that is positively Jetsons-like. Think through the implications of these technologies, however, and an even more startling vision emerges: the future will look more like the past.

Much has been written over the last decade about how the Internet, by enabling online commerce, social networks, and easy access to information and entertainment, has transformed the global economy. But we’re just beginning to see the dramatic changes this will in turn bring to the physical landscape. Ubiquitous connectivity will not only supercharge our way of life and our ways of working, it will in some sense reverse them.

To understand why, consider that the physical infrastructure of today’s society evolved in response to basic information transfer problems. In order to efficiently exchange the information necessary to buy and sell goods, produce things of value, learn, or be entertained, people had to gather in physical places. Thus, you can see our existing infrastructural assets, and the business processes supporting them, as information transfer proxies. Consumers go to retail stores to find out what is available at what prices—in other words, in large part, to get information. Workers go to office buildings to gain access to files and communicate with co-workers—again, for information access and transfer processes. Walmart stores and office buildings are essentially giant file cabinets where shoppers and workers go to get and exchange information.

Today, information and communications technologies remove the need for such proxies. To name some obvious examples, eBay, Google, Amazon, and Orbitz have each in their own way reversed traditional requirements that the customer travel – to a garage sale, library, bookstore, or travel agency – to obtain a good or service. Information transfer processes are efficient enough to allow stores to come to shoppers, files to come to laptops, and work to come to workers.

Helping to effect this reversal are any number of new technologies. Beyond the drones and autonomous vehicles, we’re entering the age of remote “printing” of physical objects, remote health monitoring, advanced battery technology, global wireless broadband, robotics and AI, distance learning, virtual teams, virtual design and manufacturing, virtual retailing, Cloud memory – all of it tied together through high-bandwidth networks, social networks, groupware, crowd-sourcing and funding, and a host of other software innovations.

So let’s imagine what our economy’s physical landscape might look like when three things are true:

We mainly buy at home. Amazon and Federal Express are pointing the way to a future when no one need venture outside the comfort of home to procure the goods they want. Rather than having stores in shopping centers, retailers will construct massive warehouses and home-deliver products directly. Those massive warehouses are much easier to automate. So robots will play a more important role in retail’s future. Virtual shopping on high-def screens will replace much of traditional shopping because virtual stores are always open, have full inventory, and are infinitely scalable.

Even health care is harking back to the days of the house call. The latest evidence is the recent news that healthcare companies are experimenting with “hospitals at home” for patients – not surprising, given that the cost of adding a new in-hospital bed now averages well above $1.5 million.

We mainly work at home. The costs associated with bringing people to specific buildings where they can access the information they need to accomplish work are increasingly untenable. The average office worker earns $28,050 per year currently. Statistics also show that the average worker spends about $3,000 annually on commuting – and loses time in the process worth $2,850. On the employer side, the cost of maintaining the average office space is $5,000 per year. Everything argues for reverting to a time before office buildings. As information transfer devices, they have already outlived their usefulness.

We mainly learn and are entertained at home. Any accounting of middle-class earners and how their household incomes are allocated tells the same tale: more and more as a proportion is being spent on virtual goods and services. Money is increasingly going to buy bandwidth, music and entertainment, cloud services, education content, information services, and games. Global spending on broadband alone is expected to increase from $431 billion in 2014 to $558 billion in 2017 (and with improved broadband, consumers will purchase even more content). Of course, any monies spent on virtual services are not available to spend on physical alternatives.

As this future unfolds, much of today’s infrastructure to provide and support information transfer proxies will rapidly become irrelevant. And our social landscapes might well revert to something more like the walkable, livable, sociable communities that urban activists like Jane Jacobs have rued the disappearance of.

Eventually it will even be true that the human-driven automobile no longer dictates infrastructural decisions. America’s love affair with the car fueled its economic growth for a good part of the 20th Century. But that affair is turning sour. A Texas A&M study forecasts that by 2020 Americans will spend 45 hours per year tied up in traffic (compared to 38 hours in 2011). So the inclination to work at home, or use some form of mass transit, is only going to increase. It’s no wonder that sales of cars to Millennials fell from 2007 to 2011 by almost 30 percent – and that, according to a Goldman Sachs survey, more than half of this generation (the largest population cohort ever) has little interest in ever owning a car. Automotive sales slammed into reverse while options for shared transportation grow could change the scene outside our windows considerably.

There will be other aspects and angles to this time of reversal – too many to discuss here. One implication is that those who think through the likely course of this revolution will be able to not only enjoy it but also profit from it. Here, for example, is a tip that might not already be obvious: Expect construction to boom. It will go hand in glove with all the deconstruction of what no longer makes sense. We’ll go further to predict that construction might be the largest source of job creation in the Great Reverse.

A world where things come to us will have a very different physical infrastructure. As less retail and office space is needed, that square footage will be converted to serve different purposes. In hyper-expensive places like Silicon Valley, it might be used for homes (just as, in New England, scores of 19th century mills are being repurposed into character-rich condominiums). Home space itself will also be reconfigured. Three-car garages might downsize to yield office space for home workers.

The demand will grow to wire the country with fiber to better service the needs of home workers, to bring better virtual experiences into our living rooms, and to satisfy the needs of commerce. It is entirely possible that people will discover they want to live in different locations once high-speed interconnections satisfy a lot of their transportation needs. The automobile created the suburbs; now perhaps high bandwidth will power a resurgence of the city for residential living – and that would be the biggest construction project of all.

Renewed investment in infrastructure has been a big theme in policy discussions lately – but the key thing to understand is that the money won’t be best spent on repairing and reinforcing today’s obsolete assets. Building the future that resembles the past will require the infrastructure of information. A good place to start would be to wire the country with the fastest broadband available, funded by some of the money currently dedicated to traditional infrastructure. We also must start rethinking everything from building codes to transportation regulations. Big choices will have to be made, and in a time of rapid transformation toward both the future and the past, the time to start this conversation is now.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers