Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1292

May 25, 2015

Why Today’s Teens Are More Entrepreneurial than Their Parents

My teenage daughter is going to Korea for two weeks this summer. Which meant she needed to earn nearly $3,000. So she decided to become an entrepreneur, and started a baking business that is financing her trip to Korea — one $5 loaf of hot, homemade bread, and $12 fresh-out-of-the-oven pan of cinnamon rolls at a time.

This is different from the work my husband and I did as teens; I worked as a cashier at a Burger Pit in San Jose, Calif., and my husband worked on a pick-your-own berry farm in southern Maryland. But among my daughter’s peers, becoming an entrepreneur appears to be the rule, not the exception.

The abysmal job market for teens is forcing many of them to think differently about work. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics the teen employment rate from 1950-2000 hovered around 45%, but since then has steadily declined. As of 2011, only 26% of teens were employed. Certainly the reasons for this decline are multifaceted, from a struggling economy, to competition with older workers, to time conflicts, to the fact that many teens just don’t want traditional “teen jobs.”

A quick poll of my peers revealed that about 60% of them had traditional “teen” jobs; flipping burgers, waiting tables, and the catchall “office work” — typing, filing, and reception. But when I asked what their children do to earn money, only 12% of them had jobs that I would describe as traditional teen jobs. A whopping 70% had jobs that are best described as self-employed; ranging from owner/operator of Diva Day Care to selling on eBay to teaching piano lessons. Today’s teens are getting a completely different work experience than I did – and it’s better preparing them to be innovators.

The media is playing an important role in this shift. Shows like “Shark Tank,” featuring young entrepreneurs, and local and national media covering feel good stories about successful teens have changed the way our youth view work. In fact, according to a Gallup poll, 8 out of 10 kids want to be their own boss, and 4 out of 10 want to start their own business.

There’s also a groundswell of support from parents and adults, generally. I saw this with my daughter’s business. Our friends and neighbors could just as easily have bought their bread and cinnamon rolls at the grocery store, but when they saw that my daughter was willing to get up at 5AM on Saturday to make fresh baked bread they were inclined to support her.

In addition to the ho-hum job market, and changing cultural zeitgeist, technology is changing where, when and how early we begin to work. Take, for example, Calum Brannan, a British teen who started PPLParty.com, a social networking site for clubbers, 17-year-old Nick D’Aloisio, an Australian app developer who sold his company Summly, that summarizes the news, to Yahoo for $30 million. Or Adora Svitak, an American writer, speaker and advocate who was introduced to the world at the age of six and whose 2010 TED talk “What Adults Can Learn From Kids” has over 3 million views. For these teens, the expanse of their network is not limited to their physical location. Because of technology, their “lemonade stand” can be on any street corner of any city in the world.

And don’t forget the competitive college admissions market. In order to get into the best colleges, teens must differentiate themselves. This means excelling academically as well as participating in evening and weekend extracurriculars. Not only does this leave little time for the kind of work their parents did after school, those part-time jobs to most admissions committees simply aren’t impressive enough. It is no longer sufficient to be civic-minded by showing up for a town cleanup, you need to organize the cleanup and run it for several years. You can’t tell the college that you love journalism and then only write 2-3 articles for the school paper. You need to write dozens of articles and then publish them in multiple sources. Or better yet, start your own newspaper – online. The need to be different is forcing them to innovate and diversify in ways that previous generations never did.

This unique confluence of circumstances – a tough economy, increasingly competitive college market, expanding networks and shifts in technology – is creating a culture of innovators. Needing to, and having the opportunity to, shape themselves into something quite different than their parents, the rising generation instinctively understands personal disruption. Some people call post-millennials Generation Z, but I think a more appropriate moniker would be Generation (I)nnovation.

The article was co-authored with Roger Johnson, who holds a PhD in microbiology from Columbia University, and is former Assistant Professor at UMass Medical School. He is the lead parent of our bread-baking, headed-to-Korea, daughter.

If You Want People to Listen, Stop Talking

Andrew Nguyen

George*, a managing director at a large financial services firm, had an uncanny ability to move a roomful of people to his perspective. What George said was not always popular, but he was a master persuader.

It wasn’t his title — he often swayed colleagues at the same hierarchical level. And it wasn’t their weakness — he worked with a highly competitive bunch. It wasn’t even his elegant and distinguished British accent — his British colleagues were persuaded right along with everyone else, and none of them had his track record of persuasion.

George had a different edge, which wasn’t immediately obvious to me because I was listening to what George said. His power was in what he didn’t say.

George was silent more than anyone else who spoke, and often, he spoke last.

I say “anyone else who spoke” because there are plenty of people who remain completely silent — they don’t say anything, ever — and they are not persuasive. For many people, silence equals absence. But George was not absently or passively silent. In fact, he was busier in his silence than anyone else was while speaking. He was listening.

It’s counterintuitive, but it turns out that listening is far more persuasive than speaking.

It is easy to fall into the habit of persuasion by argument. But arguing does not change minds — if anything, it makes people more intransigent. Silence is a greatly underestimated source of power. In silence, we can hear not only what is being said but also what is not being said. In silence, it can be easier to reach the truth.

There is almost always more substance below the surface of what people say than there is in their words. They have issues they are not willing to reveal. Agendas they won’t share. Opinions too unacceptable to make public.

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

We can hear all those things — and more — when we keep quiet. We can feel the substance behind the noise.

I could tell what George was doing, because when he decided to speak, he was able to articulate each person’s position. And, when he spoke about what they said, he looked at them in acknowledgement, and he linked what they had said to the larger outcome they were pursuing.

Here’s what’s interesting: Because it was clear that George had heard them, people did not argue with him. And, because he had heard them, his perspective was the wisest in the room.

This relates to another thing George consistently did that made him trustworthy and persuasive. He was always willing to learn something from others’ perspectives and to let them know when he was shifting his view as a result of theirs.

Because words can so often get in the way, silence can help you make connections. Try just listening, for once. It softens you both, and makes you more willing not only to keep listening, but to incorporate each other’s perspectives.

If you treat this silence thing as a game, or as a way to manipulate the views of others, it will backfire. Inevitably you will be discovered, and your betrayal will be felt more deeply. If people are lured into connection, only to feel manipulated, they may never trust you again.

You have to use silence with respect.

There are so many good reasons to be thoughtfully silent that it’s a wonder we don’t do it more often. We don’t because it’s uncomfortable. It requires that we listen to perspectives with which we may disagree and listen to people we may not like.

But that’s what teamwork — and leadership — calls us to do. To listen to others, to see them fully, and to help them connect their desires, perspectives, and interests with the larger outcome we all, ultimately, want to achieve.

There’s something else we offer, as persuasive leaders, when we are silent: space for others to step into. Lau Tzu, the ancient Chinese philosopher wrote: A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.

When people contribute their own ideas, they inevitably work harder than if they are simply complying with our ideas. Silence, followed by a few well-chosen words, is our best bet at achieving this leadership ideal.

So, how do we do it, in practice? We all know how to be silent. The question is: can we withstand the pressure to speak.

Few resist it, which is why we seldom have silent moments in groups. But that, according to George, can be used to our advantage.

“When you ask a question into a group,” he told me, “think of it as a competition. If you answer your own question, you’ve lost. You’ll be answering your own questions all day and no one else will do the work. But wait in the silence — no matter how long — until someone in the group speaks. And they will then continue to do the work necessary to lead themselves.”

There it is, his secret: Let other people speak into the silence and listen quietly for the truth behind their words. Then acknowledge what you’ve heard (which is, most likely, more than has been said) and, once the others feel seen and heard, offer your view.

And when they all agree with you? That’s the power of silence.

*I changed George’s name to protect his privacy.

May 22, 2015

3 Rules for Experts Who Want More Influence

In these days of social media chest-thumping, it seems like everyone is calling themselves an expert. This declaration is often in inverse proportion to how well-known the person is; back in the early days of my consulting career, I, too, clamored to label myself an “expert,” as though that would assuage potential clients who had never heard of me. Not so much.

The first rule of expertise, I’ve learned, is never to call yourself an expert. That’s for others to determine. But becoming a recognized expert in a world of pretenders is increasingly valuable. Here’s what I learned in the course of researching my book Stand Out: How to Find Your Breakthrough Idea and Build a Following Around It.

The first ingredient in becoming a recognized expert is, of course, cultivating true knowledge of your subject matter. Ramit Sethi – the bestselling author of I Will Teach You To Be Rich – developed his knowledge of personal finance the hard way, through his personal experience of winning a college scholarship and then almost immediately losing half in the stock market. “Oh, I better learn how money works,” he recalls thinking, leading him to start his blog and master the techniques he now teaches. Nate Silver, the famed presidential prognosticator, similarly taught himself the statistical skills he needed by creating a tool to track baseball players’ performance – techniques he later applied to the Electoral College.

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

The second step is sharing your knowledge, because if no one knows you’re an expert, it doesn’t really count. Sethi and Silver have written books to make their insights available to the broader public. Books themselves are rarely the most lucrative thing for a thought leader to focus on, but they’re essential to idea dissemination and building a broader audience (and can generate substantial returns in other ways, such as through speaking fees). Even if your goal isn’t becoming an international thought leader, sharing your ideas in book form can be a powerful tool. In Stand Out, I tell the story of Miranda Aisling Hynes, who self-published a book about creativity and leveraged it to land a coveted job at an arts organization, as well as Mike Lydon, an urban planner who launched his business on the strength of a free self-published book that went viral and established his reputation.

The final step in becoming a recognized expert – one who doesn’t need to shout it from the rooftops, because others are doing it for you – is to cultivate a following. Part of this comes naturally, as you create content over time and more people are exposed to your ideas. You move steadily from, “Who’s that?” to “I think I’ve heard of her” to “I love her work!” You also begin to have institutions jump on board and volunteer to spread your message further. When I first started to build my platform and create content regularly, I had to beg to get published, approaching dozens of publications and being rebuffed by all but a few. But within a few years, a major publication reached out to me on Twitter and asked me to start writing for them regularly. Now, they retweet my work and I have access to their fan base to grow my own.

Similarly, even as social media dominates the headlines, experts are increasingly recognizing that a direct link to their fan base is the real gold. “To me, the hottest and sexiest social network right now is your inbox,” blogger Chris Brogan delightfully said about email marketing. That’s why one of my top goals for 2015 is doubling the size of my email list – because as audiences fragment due to the decline of mass media, you can’t rely on a Today Show appearance to “make” your brand anymore (as Rachael Ray did). You have to build a following, but increasingly that’s your own responsibility.

In a world where too many people claim to be experts, it becomes even more important to be one, and ensure the right people know it. When you’ve cultivated genuine expertise, shared your knowledge generously, and worked to increase the scale of your impact by reaching more people, you’ve become worthy of the title.

If you’re just starting out and still building your credentials, read Dorie Clark’s previous post, Get People to Listen to You When You’re Not Seen as an Expert.

Lilly Pulitzer’s Target Disaster Was Actually a Success

At first blush, the recent rapid sell-out of the new “Lilly Pulitzer for Target” line — and the backlash it generated from disappointed customers — seems like a major screw-up by both companies. But it actually contains the keys to successful expansion for other high-end brands and designer labels and to improved brand perceptions for other mass retailers.

There’s no question that Target disappointed many customers by selling out of the exclusive line within hours. Its website crashed, mobs formed in its stores, and some pieces ended up for sale on eBay at multiples of their original prices. Reporters and business experts alike questioned how Target could have allowed such a snafu, particularly after experiencing similar problems a few years earlier with a line from Missoni. They also predicted significant damage to both the Lilly Pulitzer and the Target brands given how their customer relationships had been soured.

Some used the situation to bolster their criticism of Lilly Pulitzer’s wisdom in forming the partnership in the first place. Critics wondered why a designer brand would put its name on products perceived as lower quality reproductions of original classics and make them available to mass consumers in low-brow stores at a fraction of the prices it commands elsewhere. It seemed to dilute the brand’s exclusivity and premium image.

But unlike the market saturation and brand extension strategies that have de-valued other luxury brands like Michael Kors and Coach, the Target collaboration was a smart move for Lilly Pulitzer. The limited-item, limited time collection allowed the company to expand the brand while maintaining its exclusive appeal.

It generated awareness for the brand with new customers. Previously Lilly Pulitzer was well-known among the Palm Beach set and sorority sisters, but it lacked the mainstream awareness it needed to become a cultural icon. Target effectively introduced the brand to millions of younger consumers — people who influence whether brands are considered hot or not by injecting them into social conversations, haul videos, and Pinterest boards. Despite — or rather, perhaps because of — the fact that those new customers weren’t able to purchase the products, they were exposed to the brand style and the huge hype it generated.

The partnership with Target also expanded Lilly Pulitzer’s relatively small business into significant national distribution. Compare Target’s 1,800 stores to Nordstrom’s 116 and the brand’s own 29 — not to mention the different types of markets the companies operate in. Availability in new geographies and a new class of trade generated wider and more varied media coverage for Lilly Pulitzer — and it proved brand demand to new retailers in different markets that the company may aspire to distribute through. The sell-out only magnified the company’s exposure in both regards.

Most importantly, Lilly Pulitzer for Target increased the designer’s desirability through a different kind of scarcity. High-end brands have long used limited distribution and limited production quantities to boost their appeal — thanks to human psychology, people simply desire more those things they can’t have. The exclusive line at Target had always been intended as a limited-time only promotion and would have enjoyed some appeal because of that scarcity alone. But by selling out so quickly, demand increased that much more. While other designers and luxury brands have struggled with making their brands too accessible by making their products too broadly available, the Black Friday-style rush at Target managed to make even Lilly Pulitzer’s mass-targeted offering seem scarce.

The outcomes weren’t positive only for Lilly Pulitzer — Target also benefited significantly from the collaboration. Mass retailers struggle with value perceptions, since so much of their brand appeal is driven by low prices. Target has used its partnerships with designers to improve its perceived brand value and the buzz that the Lilly Pulitzer sell-out created only increased that perception. Given that items were resold with significant mark-ups on eBay proves that the relatively low prices offered by Target were only part of the collection’s appeal. Target had effectively shaped a new value equation for its goods.

Moreover, the promotion highlighted exclusive products, another powerful weapon many retailers use to combat commoditization. Lilly Pulitzer may have provided product differentiation for Target for only a short period of time, but it contributed to the positive halo Target has been developing over the rest of its assortment. And the next Target-designer partnership is likely to remind people of the Lilly Pulitzer scarcity, thus continuing a virtuous upward cycle for Target.

Given the harsh criticism both companies had to address, the problems Target and Lilly Pulitzer encountered can hardly be called desirable. But they’re not as problematic as they initially seem — and with better communication, more robust technology, and measures to prevent re-selling, the backlash could have been moderated. When all is said and done, the incident may end up inspiring other labels and retailers to use similar partnerships to achieve their brand goals.

Data Scientists Don’t Scale

Big data is about to get a big reality check. Our ongoing obsession with data and analytics technology, and our reverence for the rare data scientist who reigns supreme over this world, has disillusioned many of us. Executives are taking a hard look at their depleted budgets — drained by a mess of disparate tools they’ve acquired and elusive “big insights” they’ve been promised — and are wondering: “Where is the return on this enormous investment?”

It’s not that we haven’t made significant strides in aggregating and organizing data, but the big data pipedream isn’t quite delivering on its promise. Despite massive investments in technology to store, analyze, report, and visualize data, employees are still spending untold hours interpreting analyses and manually reporting the results. To solve this problem and increase utilization of existing solutions, organizations are now contemplating even further investment, often in the form of $250,000 data scientists (if all of these tools we’ve purchased haven’t completely done the trick, surely this guy will!). However valuable these PhDs are, the organizations that have been lucky enough to secure these resources are realizing the limitations in human-powered data science: it’s simply not a scalable solution. The great irony is of course that we have more data and more ways to access that data than we’ve ever had; yet we know we’re only scratching the surface with these tools.

A few innovative executives understand this and have sought scalable, automated solutions that interpret data, unlock hidden insights, and then provide answers to ongoing business problems. Artificial intelligence (AI) is beginning to transform data and analysis into relevant plain English communication. AI is shortening employees’ data comprehension-to-action time through comprehensive, intuitive narratives.

Any organization where employees are spending valuable time on manual, repetitive tasks is a prime case for intelligent automated solutions. There may be no better example of this than the financial services industry.

Take for example the necessary but incredibly manual process of producing performance reporting for mutual funds. Typically, marketing teams toil every quarter to document portfolio performance and add commentary (see an example here). Today, some funds are using advanced natural language generation (Advanced NLG) platforms, powered by AI, to automatically write these reports in mere seconds. (My company, Narrative Science, works with multiple financial services clients to do this sort of work.)

These are not simple, static reports, but are data-driven, complex, and dynamic, reflecting the brand voice most appropriate for the firm. The reporting incorporates disparate data sources and performs real-time analysis on portfolio performance. These systems examine the facts, determine which of these facts are most notable, and output these facts as readable narrative text. For instance, the report could be a bulleted list of key findings for portfolio managers who just need the facts, or it could be a lengthy detailed summary to meet an investor’s needs.

To do this work, the system starts with the goals of the report (e.g., did this portfolio outperform the benchmark?). Once the business need is clear, the system pulls in the necessary information (portfolio results compared to the benchmark), performs the relevant data analysis (cohort comparison), and finally decides which data is required to complete the task (portfolio attribution data, returns data, expected values, actual values, and any confidence weights on the expected values).

Once the report is created, it updates automatically as the data does, eliminating the need to redo the analysis and reporting each time there is a change.

The use cases for these systems are countless, but they all start with the question: What do I want to communicate that currently requires a significant amount of time and energy to analyze, interpret, and share?

Take medical billing. AI scours thousands of billing records across hundreds of hospitals and generates narrative reports that immediately provide the desired analysis. These reports can highlight changes to a hospital group’s insurance-provider portfolio or changes in demographic mix that are affecting revenue and cash flow, while simultaneously identifying room for growth by suggesting changes to a doctor’s workload.

There are also a number of examples where AI solutions are improving customer experience. AI is the first technology to make personalized, “audience of one” communication a reality. Companies can speak to each customer as if they are the only customer, offering personalized reports that seamlessly integrate with consumer applications and websites.

Wealth management is starting to see this benefit. Many of us have now heard of “Robo-advisors,” the automated financial advisor that can offer a low-cost alternative to expensive, human advisors. AI is being embedded into existing advisory platforms, delivering personalized portfolio reviews and recommendations in natural language to customers who are unsure as to what their charts and graphs actually mean. Unlike the Robo-advisors that operate in a “black box,” these AI systems provide transparency by communicating what has happened and offering recommendations in plain English that people can immediately understand.

The commonality across all of these new technologies is that they offer something additional humans cannot provide: the power of scale. Organizations that do not have a strategic initiative to regularly and organically engage with its customers will be at a serious disadvantage. Soon, AI-driven engagement models that interpret data and intuitively interact with clients will be the norm.

In the near-term, the adoption of AI within business intelligence platforms and customer-facing applications will accelerate. When a business user receives a dashboard, he will also receive an accompanying narrative to explain the insight within the visualization, easing consumption and quickening the pace of decision-making. Eventually, AI will offer even more complex analysis and advice. When a salesperson checks her pipeline status within her CRM application, she’ll be able to ask, “How am I performing compared to my colleagues this quarter?” and “Where should I focus my efforts to ensure I reach my quota?” The application will be able to respond immediately, with an explanation and sound advice she can understand and act on, in a back-and-forth, conversational manner.

The key to all of this is the intersection of AI and advanced natural language generation. We’re at the beginning of the next phase of big data, a phase that will have very little to do with data capture and storage and everything to do with making data more useful, more understandable and more impactful.

How to Get a New Employee Up to Speed

From a manager’s perspective, a new hire can’t come up to speed fast enough. Balancing the newcomer’s need to learn the ropes and your desire to have her quickly produce is a challenge for any time-strapped boss. What’s the best way to bring your new employee on board? Who do you enlist in the training? And how long should you expect it to take?

What the Experts Say

“If you want people to perform well, you have to get them off to a good start. That’s kind of obvious, isn’t it?” says Dick Grote, performance management consultant and author of How to Be Good at Performance Appraisals. It’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate about their first few months. “People are very excited and quite vulnerable when they take new jobs, so it’s a time in which you can have a big impact,” says Michael Watkins, author of the bestselling book, The First 90 Days. “Often the people who get the least attention are those making internal moves,” says Watkins, but those transitions, “can be terribly challenging.” Whether your new hire is joining the company for the first time or transitioning from another part of the organization, here’s how to make it as smooth as possible for everyone.

Focus on culture

Most managers focus on orienting the new hire to the business — strategy, formal structures — or explaining rules by going over the employee manual or sharing compliance regulations. All of that is important “but the focus should really be on culture and politics,” Watkins says. And you shouldn’t wait until the employee’s first day to broach the subject. Effective onboarding starts during the recruiting and hiring phase — when you’re interviewing the potential hire and assessing fit. Talk honestly about how things work and answer questions. Then, once the employee starts, set time aside in your initial meetings to continue the conversation. If your new hire is coming onboard from outside the company, don’t assume he knows the lingo of the organization and the industry. Take the extra time to translate for him. Help him understand meeting dynamics by debriefing afterwards, addressing some of the finer points of relationships between people that an outsider would have no way of knowing. Connecting socially will help your new hire better understand the culture or politics. So before he starts, consider: who does that person need to know to be successful? Start with three people, and facilitate introductions between them and the new teammate.

Get your entire team involved

Watkins recommends enlisting your team in getting their new teammate up to speed and sharing “collective responsibility” for his success. Ask one person to act as a sponsor, advises Grote, and designate him or her to be the go-to person when the new teammate runs into problems. This is good for the sponsor, for whom this is an opportunity to demonstrate leadership skills, and the new employee, who can get feedback without having to worry about asking his new manager (sometimes silly) questions. It also takes some of the responsibility off of your shoulders.

Set expectations early on

Your new employee needs to know job expectations from the start. Grote explains that at Texas Instruments, for example, each new or transitioning employee gets a copy of the performance appraisal. “On the first day, the manager goes over the form; they use it as a tool to explain how performance will be measured and what they’ll be held accountable for,” Grote says.

Don’t overlook the little things

Put yourself in the new hire’s shoes. “You want to make sure that his first day is memorable in a positive way,” says Grote. “Say an employee goes home at 5 PM on his first day, and his partner asks about his day. His response shouldn’t be that he filled out 37 forms.” Simple things make a difference. “Ask coworkers to coordinate so the new teammate doesn’t eat lunch by himself the first week,” Grote suggests. He acknowledges this may seem mundane but it makes a difference. Similarly, part of creating a welcoming environment includes having logistics like business cards, workstations, and access passes ready to go. Watkins explains that he’s seen companies forget to do this and it has an impact: “For the first week, the new hire had to walk around with a visitor tag, and that sent a particular message to the newcomer and everyone around him,” he says.

Give them time to grow

So, how long before your new hire is fully assimilated into her position? “90 days and not a minute longer,” Watkins jokes. Humor aside, Watkins explains there is no one-size-fits-all answer. “When you look at high-level employees transitioning within a company, research indicates they feel they add value by about six months,” he says. “But if you’re coming into a challenging job from outside the company, it may take a year.” Grote agrees: “Onboarding time is a function of the job.” The idea of a new employee “hitting the ground running” is a farce, he says. “You know what happens if you do that? You fall on your face.” Grote says new teammates need to start at a reasonably paced walk and accelerate as quickly as is comfortable. “Ask your existing employees how long it took before they felt they were part of the team. What they say is the best data you’re going to get,” he advises. While you’re at it, ask them about their overall onboarding experience. “The old-timers won’t remember, but those hired two months ago will have feedback about what they wish they’d learned earlier,” Grote says.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Take time to explain and answer questions about the company’s culture

Create collective responsibility for the success of the new teammate by sharing onboarding duties with their peers

Ask current teammates about their onboarding experiences to gain insight into the process

Don’t:

Bury your new hire in paperwork on the first day — make her feel welcome and happy to be there

Forget to handle simple logistics like workstation set-up and business cards

Expect your new teammate to “hit the ground running” — understand that the time it takes to get up to speed is a reflection of the position

Case Study #1: Stay organized so things don’t fall through the cracks

Emily Burns has worked for Ruan Transportation Management Systems for nearly four years, and currently works in human resources. After a year on the job, she noticed her team’s onboarding practices were too informal. “We often didn’t have everything ready for the new teammate on his or her first day,” she explains.

Emily set out to standardize the process. She created a master checklist that managers could go through and put all the relevant new hire documents in a shared file on the company portal. “These files document every single thing that has to happen, and by what day, in order for everything to be ready on the day the new hire starts,” Emily says. The list of tasks begins 14 days before the new hire starts and ends six months into their employment.

Have Emily’s efforts helped? “Well, turnover has decreased, and our new team members can start training and contributing on day one,” Emily asserts. Emily notes the new process makes new employees feel taken care of and more satisfied with their new job, manager, and company. “When they experience this type of security and stability on their first day and their onboarding has been seamless, they can better focus on learning their job and doing their work.”

Case Study #2: Help them learn the lingo

In the fall of 2014, Ryan Twedt, owner of Be Always Marketing, hired a new salesman, Justin Thompson, to join his team of seven employees. Because marketing terms seemed like such basic concepts, he didn’t think to incorporate them into Justin’s training, even though Justin was coming from a different industry.

He soon realized his mistake. When they went into their first sales meeting together, “Justin was using industry lingo at the wrong points in conversation, and it became clear there were basic definitions he didn’t know,” says Ryan. “It hurt our ability to close, and it impacted our client’s trust in us.”

Before he could train Justin, Ryan needed to set expectations. He created a formal description for Justin’s role, including accountability metrics. Then Ryan worked with Justin to help him practice sales techniques. “Justin had to call me every day and act as if he was trying to close a sale with me, and I would take on the role of a different industry leader each time,” Ryan says. Through practice, Justin learned the lingo and the techniques he needed to approach a potential client.

Justin’s performance improved rapidly as a result of Ryan’s efforts. “I saw a major improvement within the first week, but the tangible results started coming in about three weeks later.” Ryan noticed Justin’s closing rate increased, overall leads increased, and Ryan started to hear about Justin’s sales calls from people outside the company who were impressed with his skills. As a result of his experience with Justin, Ryan now takes the same approach with each new hire.

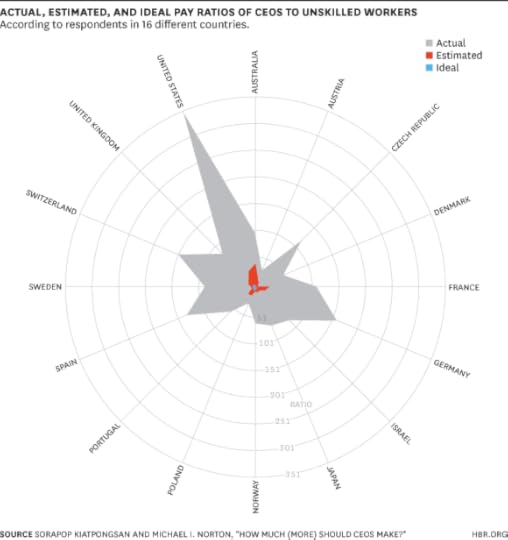

The Factors That Lead to High CEO Pay

No matter where you live, the difference between how much CEOs are paid and how much the average worker takes home is, well, big. Probably even bigger than most people think.

The reasons why the disparities vary country-to-country are complex, according to a recently accepted paper for the Strategic Management Journal by LSU E.J. Ourso College of Business professor Thomas Greckhamer. A social scientist, Greckhamer attempts to identify combinations of factors on a country-by-country basis that either widen or narrow the pay gap between CEOs and workers. Using data from the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook from 2001, 2005, and 2009 for 54 countries, he also configured a model featuring power structures he expected to influence compensation, based on prior research of determinants of executive pay.

His conclusions aren’t neat and tidy, but a few things stand out: A country’s level of development matters for workers’ compensation, but not so much for CEOs’. A country that has a high deference for power will probably have higher-paid executives. And the political strength of the labor movement matters. But you also can’t isolate a single one of these factors as the determinant of income inequality.

To better understand how he got these findings, it’s worth laying out the eight compensation-influencing factors used by Greckhamer in his analysis:

1) A country’s level of development. This is important for a variety of reasons he describes in-depth, though the basic point is that high development should result in less income inequality, with both CEOs and workers making more.

2) The development of equity markets. The more developed markets increase ownership “dispersion,” or the number of people who own shares in a company. Greater dispersion, writes Greckhamer, “implies reduced owner-control, which should increase CEOs’ power to allocate more compensation for themselves.”

3) The development of the banking sector. The more concentrated the sector is, the more that should “monitor and control firms and thus constrain CEO power and pay.”

4) Its dependence on foreign capital. When foreign investors have influence over a company’s stock, it can boost income inequality.

5) Its collective rights empowering labor. This is basically collective bargaining rights, which are “a vital determinant of worker compensation” according to Greckhamer, and can also potentially limit CEO pay.

6) The strength of its welfare institutions. Their job, of course, is to “intervene in social arrangements to partially equalize the distribution of economic welfare,” which generally means lowering CEO pay and increasing that of regular workers.

7) Employment market forces. In other words, the supply and demand for executives’ and workers’ skills.

8) Social order and authority relations. Greckhamer describes this as “power distance,” which basically means “the extent to which society accepts inequality and hierarchical authority.” A high power distance tends to lead to high CEO pay and low worker pay.

After running his analysis, he identified how all of these factors work together to shape how much CEOs and regular workers get paid.

The Combinations that Increase CEO Pay

In one scenario, for example, highly developed equity markets, a strong welfare state, and a high power distance – combined with a lack of foreign capital penetration and supported by a few complementary conditions – were key indicators.

Generally speaking, though, a lack of collective labor rights and a high power distance are two of the core and complementary factors most often present in countries with high CEO pay. “This suggests that a combination of high cultural acceptance of hierarchical power structures and a lack of institutions empowering labor are vital institutional conditions for highly compensated CEOs,” Greckhamer writes.

This is pretty obvious, but there’s also a surprise in the data, too. While a few predictors indicate that a shortage of candidates results in higher CEO pay (which would make sense when you think about how market conditions work), there are situations that contradict this. In some locations that are lucrative for top brass, there are plenty of available senior managers to choose from. Greckhamer posits that places with a competitive labor market that also accepts hierarchy and doesn’t have strong labor rights basically operates as “tournaments among an abundant cadre of senior managers and with relatively high prizes for the winners.”

The Combinations that Reduce Inequality

One factor that doesn’t play much of a role on its own, surprisingly, is a country’s level of development, a finding that contradicts previous research. But that changes when you look more closely. A high level of development combined with a lack of hierarchies seems to increase worker pay. “High development was necessary, but not sufficient, for workers to achieve high compensation,” he told me. This may also be one of those cases where the absence of something is more felt than its presence: “A lack of development was also important for several paths to the absence of high worker pay,” such as the presence of foreign capital and less-developed equity markets.

Unsurprisingly (but importantly), locations with low CEO pay tend to have strong collective labor rights, a strong welfare state, and less power distance across the board.

There’s evidence, Greckhamer explained over email, that countries that both empower workers and culturally reject inequality constrain CEO pay. This, he says, showcases the vital importance of “political forces” – government policies or strong unions, for example – when it comes to executive pay.

Almost across the board, a strong welfare state and/or strong collective labor rights are a core condition for higher worker pay. And low worker pay is almost entirely moderated by a lack of a welfare state and/or a lack of collective labor rights.

“I believe that pay dispersion between CEOs and rank and file employees is a vital questions of our time, both from the point of organization theory and from the point of view of the general public,” Greckhamer says. And because organizations don’t exist in a vacuum outside a nation or culture, studying them within those contexts is essential.

At the same time, because so many different factors are intertwined, the relative lack of action to limit CEO pay makes a certain reluctant sense: Because it’s so seemingly complex, where do you even start?

In light of this, I asked whether his findings were “actionable.” He replied that it “depends to a large extent on whether organizations (or societies) consider a certain issue a ‘problem’ and wish to take ‘actions’ to ‘resolve’ them.” So, for example, these actions could include “a combination of achieving high development, strengthening institutions empowering labor, and cultural interventions aiming to counter any ingrained cultural values accepting inequality between those and the top and those at the bottom of organizations’ hierarchies.” But only if inequality is considered a problem worth acting on.

May 21, 2015

Signs That You’re Being Too Stubborn

They’re hardheaded. They dig their heels in. You know the type — people who are way too stubborn for their own good. While it’s easy to point the finger at others who exhibit this behavior, it can be hard to recognize this trait in yourself. Here are the signs that you’re being too inflexible:

You keep at an idea or plan, or insist on making your point, even when you know you’re wrong.

You do something you want to do even if no one else wants to do it.

When others present an idea, you tend to point out all the reasons it won’t work.

You visibly feel anger, frustration, and impatience when others try to persuade you of something you don’t agree with.

You agree to or commit halfheartedly to others’ requests, when you know all along that you’re going to do something entirely different.

Stubbornness is the ugly side of perseverance. Those who exhibit this attribute cling to the notion that they’re passionate, decisive, full of conviction, and able to stand their ground — all of which are admirable leadership characteristics. Being stubborn isn’t always a bad thing. But if you’re standing your ground for the wrong reasons (e.g. you can’t stand to be wrong, you only want to do things your way), are you really doing the right thing?

Take Joe, a senior level executive whom I coached. Joe was known for his commanding presence, and for driving results within the organization. His decisiveness and ability to focus on key issues and solutions made him a valuable asset to his company. However, there were times when Joe was blinded by his own abilities and unable to see other courses of action that were in the best interest of the company and critical stakeholders. After Joe continued on with plans to reorganize a division in spite of his boss’s and the board’s caution against it, his boss aptly described the situation as such: “Joe is so laser focused on what he wants to do that he doesn’t realize he’s winning the battle, but losing the war.”

You and Your Team

Persuasion

You need influence to succeed.

Like Joe, the overly stubborn individual is often the victim of Pyrrhic victory — while they get what they want, the damage they’ve done along the way negates any good that could have come out of it.

So what do you do to ensure that your holding your ground doesn’t get in your way? Here are four strategies:

Seek to understand: Simply put, try listening to the other person. Rather than automatically shutting down the conversation, seek to understand her idea and rationale. Many people don’t listen because they’re afraid if they do, it will appear like they agree with the other party. This is not a valid reason for not listening. Just because you understand someone doesn’t mean you agree with her. But you’ll have a better chance of stating your position if you can show that you at least have a good sense of the bigger context. And who knows, you might actually change your mind once you have the whole picture.

Be open to the possibilities: Overly stubborn people often believe that there is only one viable course of action. As a result, they remain solidly staunched in their positions. By approaching a situation with an openness to at least explore other alternatives, you show some flexibility — even if you ultimately end up right back where you started. When someone is trying to persuade you on something you vehemently oppose, ask yourself “What conditions would need to be in place for me to be convinced of this idea?” By checking your assumptions, you might find yourself able to entertain other possibilities that weren’t originally in your purview.

Admit when you’re wrong: Being convinced that you’re right is one thing. Digging your heels in when you know that you’re wrong is inexcusable. In the latter situation, own up to your error and hold yourself accountable for your decisions and actions. In the long term, that will gain you far more credibility than sticking to your original plan.

Decide what you can live with: Being overly stubborn can become a habit. And while staying true to your stake in the ground is admirable, not every situation warrants that type of steadfast conviction. Rather than always pushing for your idea, decision or plan, recognize when it’s okay to go with a decision that you can live with even if it’s not your top choice. It may be that you have more to gain in the long term if you show that you’re persuadable in the short term.

At the root of all stubbornness is the fear of letting go of your own ideas, convictions, decisions and at times, identity. But as renowned author James Baldwin eloquently stated, “Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it… Yet, it is only when a man is able, without bitterness or self-pity, to surrender a dream he has long cherished or a privilege he has long possessed that he is set free… for higher dreams, for greater privileges.” Sometimes, letting go of an overly staunch position can result in greater value than you originally expected.

Health Care Transparency Should Be About Strategy, Not Marketing

Health care organizations need to re-think their concept of strategy to thrive in a marketplace driven by competition on value – how well they improve patient outcomes and reduce costs. That re-thinking begins with clarifying what the organizations are truly trying to accomplish, and for what “customers,” and how they are going to distinguish themselves from competitors and offer a unique value proposition. Make no mistake – improving value for patients is hard. But as Michael Porter and I write in our recent Perspective article in The New England Journal of Medicine, “Why Strategy Matters Now,” providers are unlikely to succeed if they cannot focus on this goal.

This critical question of organizational goal applies to how providers think about transparency – the growing trend to make their own performance data public. What are they trying to accomplish when, for example, they publicize surgical success rates or patient experience data and comments? Are they focused mostly on marketing (aka “reputation management”), or are they trying to improve their actual performance by engaging patients and caregivers with complete and objective data?

The answer is important, because the transparency movement will be a game changer. For years, most provider organizations were skeptical about whether “quality” could really be measured, and many resisted public reporting of any performance data or tried to focus their data collection on process measures that they could control. (I make these comments with appropriate humility, having at times pushed as a clinician and health care executive for “translucency” more than transparency in the past.)

The problem with translucency – in which selected data are released, but are presented in ways that make details difficult to discern – is that it isn’t particularly helpful. Patients can tell that they are not getting the complete story, and clinicians are not pushed to improve. For example, like their organizations, clinicians are most comfortable with transparency around measures that they can control (e.g., use of beta blockers after heart attacks) but the resulting data do little to distinguish performance differences among providers on what really matters – how their patients fare. This adds to skepticism among both clinicians and their organizations about the value of public reporting.

Now, however, an increasing number of health care organizations are publishing detailed data on patient outcomes, especially for major surgical procedures. And the University of Utah Health system has pioneered publication of data on patients’ experience, including virtually all patient comments. Others are following suit.

As provider organizations become transparent with their data, the question that each should ask is fundamental: Is the target the patient, and is the goal, simply, to paint a rosy picture? Or is the real goal to build patient trust by sharing true performance data and, in doing so, to help clinicians improve? When performance is on public view, everyone does their best work. And when providers receive this constant feedback on their performance, they’ll strive to get even better.

Engaging in improvement-focused – rather than marketing-focused – transparency is hard work. It requires organizations to rigorously collect data from as many patients as possible and to analyze it with the best available tools and benchmarks. It requires that the resulting data be displayed with unflinching honesty. And it requires that organizations make clear that the transparency effort is intended, above all, to drive improvement. If “transparency” initiatives have a different primary goal, they’ll only inspire cynicism.

Is Rooftop Solar Finally Good Enough to Disrupt the Grid?

Over the past two decades, there have been many attempts to reform the electric utility market. The costly and complex operations of transporting energy have made utilities natural monopolies, while regulatory barriers and the high fixed costs of building and maintaining regional electrical grid infrastructure have also kept much competition at bay. But recent technological advances and new business models are now allowing nimble players to compete and provide consumers with cost-saving alternatives. With the rise of distributed forms of energy, such as rooftop solar power, and batteries, it’s become much more feasible to match individual demand for electricity with on-site production.

Distributed energy systems are basically comprised of small-scale energy-generating devices (the most common example being solar panels) that allow for electricity to be produced on-site and consumed immediately, without drawing from the local electrical grid. Recent developments, such as falling solar panel prices and increases in efficiency rates (the rate at which sunlight hitting panels is turned into usable energy), have made distributed energy increasingly economical, while new business models and financing methods have made it more accessible.

This story of disruption should feel familiar. Consider how Uber opened up the transportation market. Prior to Uber’s ascendance, entrenched taxi companies oversaw highly centralized, often unresponsive, operations, leaving consumers with few alternatives for private transportation. So the company mobilized existing, under-utilized assets and connected them to a sharable revenue stream. And it built a strong technology platform that optimizes various factors like market conditions, location, and availability to meet your needs and those of the 100 other people within your half-mile radius.

While Uber’s app can make one’s car a potential source of income, a solar panel can turn a home or a company facility into a productive asset by allowing it to produce its own electricity. In both cases, the two goods (car and real estate) are given value-creating potential through a process of market fragmentation and consumer empowerment. The result is a new value proposition: consumers get more personalized, flexible service, and new companies can charge competitive prices.

In the case of distributed energy, various financing options let consumers save in a number of ways. They are offered either solar leases (leasing the panel and its energy for a fixed periodic payment) from a solar company, power purchase agreements (they purchase each unit of electricity produced by the panel at an agreed upon rate), or solar loans (the consumer, rather than the service provider, owns the panel; effectively a solar panel mortgage). In each case, the cost per unit of electricity is not only cheaper but more stable when compared to rates charged by utilities.

With the introduction of batteries that can store electricity, such as Tesla’s, solar energy’s value proposition may well increase. Batteries can store excess solar energy produced in the middle of the day when the sun is strongest and then release the energy at peak price hours. While this isn’t quite as cost-effective for the residential sector yet, due to battery costs and regulatory issues, batteries are already being used in commercial and industrial sectors, where extra charges for using energy during high-demand periods can make up 30% of electric bills. Instead, batteries can pull electricity from the grid when prices are low, like in the middle of the night, and store it. That electricity can then be consumed later when energy is more expensive and demand charges come into play.

New energy management software can also help identify consumption inefficiency and automate electricity usage when necessary by collecting site-specific energy data. But before distributed energy can make a greater impact, more comprehensive energy management platforms must be developed. Ultimately, Internet of the Things software could optimize the interactions between a distributed energy system comprised of solar panels, batteries, and commercial or residential buildings’ energy management systems, based on real-time data from each component — much the way Uber’s platform oversees and coordinates a ride by transmitting and analyzing data from mobile devices.

To build this kind of fully integrated, smart system, different firms will have to collaborate — even Elon Musk noted that Tesla couldn’t change the energy market alone. Some solar companies, battery manufacturers, and software companies are starting to work together. Google’s Nest, a smart thermostat, now has an agreement with SolarCity, the largest U.S. residential solar installer, to eventually integrate Nest’s smart thermostats with SolarCity’s panels, and presumably Tesla’s batteries at some point in the future. And SunPower, the second largest U.S. solar manufacturer, is partnering with EnerNOC, which provides energy management software and was also announced as an early Tesla Energy partner.

Meanwhile, utilities are not standing idle. More are looking into real-time data and batteries to make the grid more efficient and reduce the variability in electricity prices throughout the day. But similar to the taxi industry, one weapon utility companies are relying on is their political muscle, which is considerable, but anti-market. This trend is becoming so well-established that the term “utility death spiral” has been coined. Utilities raise prices on customers in order to combat lost revenues from those that have turned to distributed energy forms. Of course, this response only ends up making distributed energy forms even more competitive.

The electricity market won’t see change quite as fast or garner the same headlines that Uber has, primarily due to the sheer size and complexity of the electricity market. But despite the challenges, the signs from the marketplace are auspicious. Residential use of distributed energy grew at a 50% annual rate in the U.S. from 2012 through 2014. And as distributed energy and smarter management software systems evolve, the changes could be much more profound.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers