Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1296

May 1, 2015

Why People Cry at Work

The stress of the workplace can bring out plenty of feelings in all of us. As an executive coach, I see joy, sadness, frustration, and disappointment on a daily basis. But while we may experience an array of emotions at work, there’s a general consensus that we shouldn’t see anyone reduced to tears, hopelessness, or defeat on the job. If you as a manager have caused an employee to cry, your primary objective is not to let it happen again. How?

First, you need to understand exactly what happened. What, specifically, caused the crying? Tears can signal sadness, or, quite frequently, they can be a cover for other feelings: frustration, anger, a sense of powerlessness, anxiety, poor self-esteem, or negative self-image. As a trained psychologist, I know that we have to consider the particular cognitive and emotional makeup of the person who’s in tears, as well as the situation that the person is in. What did that person really want to do: slug her insensitive boss, or walk away from a demeaning job? Those alternatives are rarely an option, so sometimes the only recourse may be to shed tears.

I’ve generally seen three primary circumstances that reduce people to tears:

The formidable manager:

It’s a good thing to be a manager who’s seen as extremely smart and highly accomplished. But remember that you may be viewed by your reports as someone who sets such a high bar that they’re quaking in their boots and sorely afraid of the consequences of not measuring up to your high standards at every turn. If that’s the case, then the simple critique you thought you’d delivered in the spirit of helping your report to develop her or his skills could have been translated as “You’ll never measure up,” resulting in a crying spell based on a sense of hopelessness. Other types of formidable managers might use fear to motivate employees, or might snap at subordinates in stressful situations, rather than using more skillful language, such as: “Hey, we’ve got a tough row to hoe here. Thanks for your effort; we all have to keep at it, but it will be worth it. Let’s stretch to reach this goal.”

Organizational culture and differences:

Like families, social groups, and geographical regions, each workplace has its own culture and expectations of behavior. In some organizations, an interaction with some edge to it is seen as the norm, and people rarely take offense. In another company, the expectation is that a critique or correction will be voiced with sensitivity and compassion. If you’re the new manager in an organization, or you’re managing a new employee, you may have erred on the side of directness when your team member was expecting more caution. I’ve often had to help a manager see that his or her definition of “calling it as I see it” equates to an employee’s sense of being unfairly attacked.

Personal life intersecting with professional life:

How many office conversations begin and end with:

“Good morning! How are you?”

“Fine; how about you?”

“Doing well, thanks.”

People don’t always reveal at work the challenges they’re facing in their lives outside of work. The person who started to cry when you mentioned that the quarterly results weren’t met may not have been hopelessly despondent about the fiscal outcome, but may have felt that everything in his or her life was currently going awry. Maybe your employee was given a diagnosis of a serious illness, experienced the loss of a close friend or family member, or was trying to absorb some other recent personal setback. Your simple observation or comment may have felt like the straw that broke the camel’s back.

You and Your Team

Emotional Intelligence

Feelings matter at work

Regardless of the source of your employee’s tears, it’s important to try to understand what happened. Here’s how:

First, listen. Find a safe but private place, such as an unoccupied conference room or office where you can speak quietly. Ask him what happened and listen as he tells you. It may take a while for him to formulate just what he’s feeling, so be patient. I’ve heard from formerly tearful employees that their manager’s willingness just to listen to their side restored the trust in their relationship and brought everyone to a more productive level of understanding.

Be empathic and willing to learn. Even if you don’t fully understand why your report or colleague would be upset over whatever it was that triggered the tears, your openness to consider the other’s feelings will help you work with that person more effectively and may help you to become a better manager in general.

Offer an apology if it’s appropriate. If your behavior was sub-par or could be viewed that way, let it be known that you regret your words or actions and the impact they had on your employee. If it turns out that the tears were primarily due to a personal struggle outside of work, acknowledge that pain and extend your best wishes.

Help them save face. Female or male, few people want to be seen blinking back tears at work. It can be humiliating. You can’t take back the incident that’s already occurred, but you can pledge not to be the cause of someone else’s tears ever again. If the incident was viewed by others, and your employee agrees to it, you can make a public apology and request that your employees let you know if you’re ever again keeping people on edge this way.

Take note if this employee is particularly sensitive by nature or going through a difficult time. Then, be specific about your objectives for this particular person and strive to catch her doing something right. That effort is always a key element in keeping people motivated, instead of hopeless, through challenging times.

Look at the big picture. You’ve talked over the situation with your employee, you’ve apologized if you contributed to that person’s distress, and addressed how you can change your own behavior. You’ve also considered the stressors that your employees may experience. If you realize that you need to listen more, create new means to express your faith in your employees, or change the organizational culture, start working on it. Demonstrate to your team that this is a workplace where no one needs to shed tears, ever.

Retirement Planning Needs a Better UX

President Obama recently called for a new fiduciary standard for retirement plan advisors, saying, “the rules governing retirement investments were written 40 years ago … I am calling on the DOL to update the rules.” You might have missed this story — or at least assumed that designing a fiduciary standard is the fraught work of policy makers. The reality, however, is that this issue is deeply connected to how we make decisions on digital displays, which is of crucial importance to investors, businesses, and policy makers.

The details of the proposed new rules are sure to raise questions about things like fee disclosures and conflicts of interest. Such a debate is unavoidable. But I also believe it will be a distraction, preventing us from considering a far more urgent set of questions for retirement plan advisors, consultants, and those tasked with evaluating benefit plans for their businesses. Simply put, we need a fiduciary standard for the digital age, one that takes into account the fact that people saving for retirement are increasingly making major financial decisions on screens and smartphones.

If the job of a plan fiduciary is to act in the best interest of their plan participants, then research suggests they need to understand how people think and choose in the online world. In the twentieth century, being a fiduciary for employee benefit plans meant having a deep knowledge and expertise of investing. Now, in the twenty-first century, these fiduciaries need to add digital expertise to their skill set.

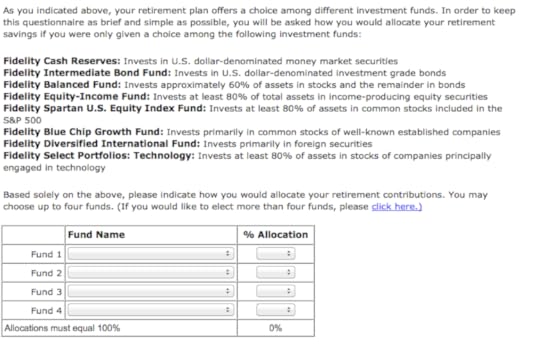

Let me explain with an experiment Professor Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago and I conducted on Morningstar.com. The experiment itself was straightforward: we asked two groups of Morningstar subscribers to allocate their retirement savings among eight different funds. The first group was presented with a website that had four blank lines on it, although there was a highlighted link if people wanted to select additional funds.

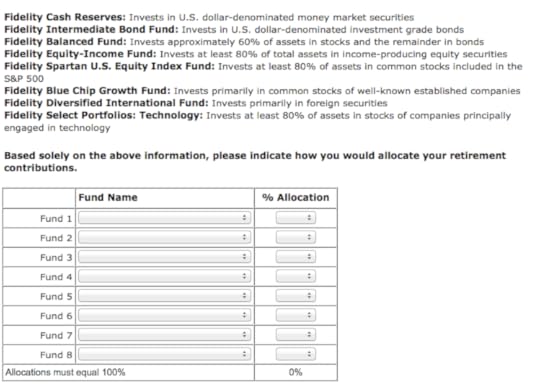

The second group was shown the same exact site, except their version had eight available lines.

This probably seems like a trivial design change. Nevertheless, Thaler and I found that the precise number of lines on a website dramatically impacted the level of diversification of Morningstar subscribers. While only 10% of people shown four lines selected more than four funds, that number quadrupled among subjects given eight lines. This means that the level of diversification was driven, in large part, by a seemingly minor website specification, almost certainly chosen by someone with little investing expertise.

The same principle applies to the opening of a retirement account. While these sign-ups used to be done with pen and paper, they are now typically done online, with people being asked to visit a website and set up an account. In theory, it’s a more efficient process.

However, there’s some evidence that the shift to screen enrollment can dramatically reduce the number of plan participants. I recently conducted a pilot experiment with John Beshears of Harvard and Katy Milkman and Yiwei Zhang of Wharton. After replicating a typical online enrollment procedure, we found that about 40% of college-educated subjects admit they are “not likely” to complete the process by themselves. Why not? One of the main impediments is the creation of a username and password, as people struggle to fulfill the security requirements. If we apply these findings to the real world, it suggests that many users will give up after a few frustrations with a website. Their choice to not enroll is not really a choice, then – it’s just a side effect of poor digital design.

How can we fix the digital problems around enrollment? One relevant solution comes from the world of college loan applications, which are also unwieldy, complex, and intimidating. To make this process easier, the U.S. government partnered with H&R Block to create software capable of automatically filling in up to two-thirds of the application based on available family tax returns. This simple intervention came with impressive results. After H&R Block made the forms easier to complete, students were 40% more likely to submit a loan application, 33% more likely to receive a needs-based scholarship, and 25% more likely to attend college. That’s a huge improvement from a simple digital fix. I believe similar strategies could dramatically increase the enrollment rate for retirement plans among employees by suggesting, for example, secure passwords.

Technology can even impact how people feel about their investment returns. Professor Thaler and I have found that giving people more feedback about their investments can trigger a mental error known as myopic loss aversion. That’s a technical term for a very common mistake, which occurs when investors make decisions based on short-term losses in their portfolio, even when they should have a long-term investment plan for their retirement funds. As Thaler and I demonstrated, this problem can be minimized if investors are shown longer-term rates of return.

In our digital world, people might look at their investment portfolio far more often, which means they are getting more short-term investing feedback. Unfortunately, this habit could actually lead to worse investment choices, especially in an age when we’ve got computers in our pockets and screens with a stock market app (as in the Apple Watch) strapped to our wrists. To help mitigate this problem, retirement plans should experiment with new default information settings, perhaps offering people longer-term return data instead of monthly or quarterly return data. (Consumers can still get the short-term feedback – it would just take a few extra clicks.) Research by Maya Shaton at the University of Chicago shows that after the Israeli government instituted a similar reform for all retirement funds in early 2010, the improvement was immediate, with investors trading less and taking smarter risks with their savings. Over time, this should lead to significantly more money in their accounts.

As President Obama said, our current fiduciary standard is woefully outdated. Given our changing world – by 2020, nearly 80% of human beings will own a smartphone – it’s easy to envision a situation in which fiduciaries would be required to consider and measure online participant behavior as part of their duties. The evidence, after all, suggests that even minor alterations – such as increasing the number of lines on a website, or changing the frequency of account feedback – can have a large and lasting impact on our financial success.

3 Steps to Break Out in a Tired Industry

Michael Levie, a seasoned hotel executive, and Rattan Chadha, a successful retail entrepreneur, were having dinner. The topic of conversation was the hotel industry. Both men thought that the industry was stale and too homogeneous relative to the diversity of customers it sought to serve. The industry had largely been unaltered since the onset of hotel chains over half a century ago. As Levie put it, “in this industry, people already think they have innovated if they have painted a grey wall green.” They two men were plotting to change that.

In 2008, they opened their first hotel, at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, followed by one in Amsterdam City in 2009. Further hotels followed in subsequent years, in Glasgow, London, Rotterdam, New York, and Paris. They called their budding chain “citizenM”; for mobile citizens. The customer group they envisioned consisted of frequent travelers. These are people who could just as easily be visiting the aforementioned cities for a quick business trip as for a leisurely weekend away with their partner. As they put it, “a mix of explorer, professional, and shopper.”

The men thought that these customers, on arrival, really did not need a porter to pick up their luggage and carry it to their room – after all, they had likely just brought it all the way from the airport on their own. Moreover, when entering the hotel, they would not find themselves in a large lobby with a check-in desk. Instead, citizenM installed check-in machines that dispensed keys when guests inserted their credit card.

Space comes at a premium in hubs such as New York and London, and Levie and Chadha realized return on square footage was going to be key. So they also crossed out restaurants, bars, and conference facilities — amenities most travelers rarely use. (The solo business travelers Levie and Chadha envisioned as their customers, for example, would prefer to get some sushi at a self-service counter to sitting at a table alone being served by a waiter, and weekend leisure travelers would likely be eating out at restaurants anyway.) Instead, what guests encounter when they enter a citizenM hotel is one large downstairs space, loosely subdivided by high-end designer furniture and pieces of contemporary art, with area central area referred to as “canteenM.” Here you can order coffee or a cocktail and pay for the food you have picked up in the self-service area.

Insight Center

The New Ways to Compete

Sponsored by Accenture

Strategies for staying ahead.

The aim of citizenM was to create a space so attractive that guests would prefer to spend their time there instead of in their rooms. This allowed Levie and Chadha to make the bedrooms quite small — the size of a shipping container. These rooms are entirely manufactured off-site at an assembly line and transported to the hotel site. There they can be stacked together in various shapes, “just like playing Lego,” Levie observed. Yet they are luxurious, with a power shower, high quality bedding, and in-room tablets that control free movies, internet, and personalized mood-settings. Once entered, the guests’ preferences are stored in a central database so that wherever they check in to a citizenM again, the room is personalized.

As a result of these decisions, citizenM’s construction costs are 40% lower than other 4-star hotels and staffing is 40% lower too, but occupancy rates (consistently above 95%) are considerably higher. Immediately after opening in 2008, citizenM won the Venuez Award for “Best Hotel Concept.” One year later, it was ranked as a best business hotel by the Sunday Times, CNBC, and Fortune. In both 2010 and 2011, TripAdvisor voted citizenM “The Trendiest Hotel in the World.”

The success of citizenM offers clear suggestions on what steps to take when looking for a new way to compete in a relatively stable and homogeneous industry:

Focus: Don’t try to be attractive to everyone.

Eliminate all things superfluous for your chosen customer base.

Replace them with new offerings found by analogy.

Consider citizenM’s use of the first step: citizenM decided immediately that it would focus on one particular type of customer only: individual, frequent travelers. Typically, competing hotels fill as many as 70% of their rooms long in advance with mass bookings for conferences, corporate rates, and airline personnel at large discounts. In contrast, citizenM accepts no such corporate clients, but prices all their rooms in real-time, dependent on supply and demand.

When you are in an industry where the firms are more homogeneous than the customers, it should be possible to define a subgroup whose needs are alike, which may well cut across traditional demographics. Focusing on that particular group often enables a new way to compete because the firms that try to be everything to everyone will inevitably be imperfect in their offering.

As Levie put it: “I think that when you decide on a niche market, what you decide on what you want to be doing, do that extremely well and don’t do other things. [Other hotels in] the industry create hotels that mid-week should be good for a business traveler. On the weekends it should be good for a group or a wedding party, or for family travel. Good luck! It ain’t happening. [You can’t] create a boat that has an engine, is a row boat and a sailboat all in one. Decide who you want to be and be very good at it!”

When having defined a subgroup, companies often proceed to think of things that those customers would value and be willing to pay for. But citizenM took another step first; it asked “what things can be eliminated for this particular group, without much affecting its willingness to pay?” It quickly came out at quite a lot of things (which, in turn, helped define the subgroup): facilities such as a restaurant, a separate bar, a spa, room service, and so on, were all excluded. This is an important step; yet asking what to reduce or eliminate is not a question that seems to come naturally to many executives.

Of course, developing a new model does not usually end with taking superfluous things out; a new way to compete is more than merely a stripped down version of what came before. New offerings will, however, by definition, not be found in the industry itself. citizenM explicitly used analogical reasoning to develop new elements in its hotels. The check-in machines are similar to those at airports; its luxurious, but small, bedrooms resemble those at a cruise ship; its booking and pricing system follows that of low-cost airlines; and hotel construction resembles Lego. The downstairs space – not coincidentally referred to as the hotel’s “living room” – with a “kitchen” as its center of activity, is made to mimic the feel of a luxurious and contemporary home, where there’s free Wi-Fi, quality furniture, and you can open the fridge to get a glass of milk at any time, and where bedrooms are only used for sleeping, showering, and perhaps watching a (free) movie.

Focusing on a core customer, eliminating unneeded elements, and its active use of analogies enabled citizenM to develop a new model in its industry. Today, citizenM is in the process of acquiring additional hotel sites in both Europe and the U.S., and has entered into an alliance to roll out the concept in Asia. Their new way to compete is likely coming to a place near you very soon.

The Myth of the High Growth Software Company

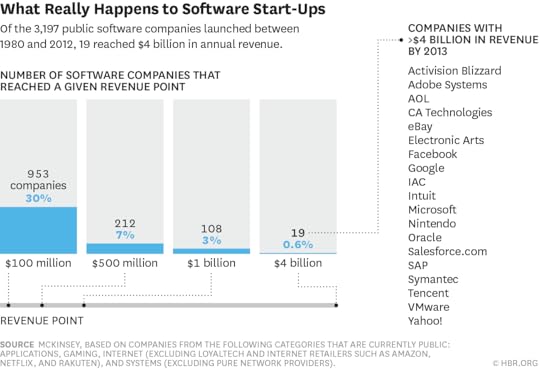

How many software companies really make it big, at least in terms of revenue? McKinsey analyzed more than 3,000 software and online-services firms from a 22-year period, finding that fewer than a third reached $100 million in revenue growth. Only a handful of companies reached the elusive $4 billion mark.

This data, combined with interviews with executives at 70 companies, led researchers to three main findings: Growth trumps all, including margin and cost structure; sustaining growth is really hard, even among companies with early momentum; and that (don’t fret!) there is a recipe for growth that involves four key principles. They are:

Growth happens in three acts.

The first must contain five steps: Picking the right market; defining a monitization model that makes room for scaling; focusing on rapid innovation; being stealthy and maintaining a low profile while developing new products; and creating the right incentives for senior leadership.

Succeeding in the second act requires a strategy that falls into one of three buckets: having a robust model you can expand upon easily as is (this is a rarity); expanding successfully into an adjacency; or transforming your product into a platform.

Companies that have figured out how to master the transition from one act to the next are the most successful.

Source: Grow Fast or Die Slow

April 30, 2015

The Assumptions That Make Giving Tough Feedback Even Tougher

Kenneth Andersson

What’s it like to be on the delivering end of a tough feedback conversation? In a recent conversation we had, a leader described his experience:

Q: What do you do to prepare when you have tough feedback to deliver to a subordinate?

A: I am super focused. I keep telling myself “be honest, and be totally direct.”

Q:Is it easy to be totally direct and honest with another person about their performance?

A: No, I want to tell them what they want to hear, but they need the truth. They need to clearly understand what’s really going on and how that affects me and everyone else in the team.

Q: Are you assuming that they don’t realize there’s a problem?

A: Of course! If they realized there was a problem then I would not have to straighten them out.

Q: Are you nervous? Do you find this difficult?

A: This is the absolute worst part of my job – I really have a hard time doing this. I can’t wait for it to be over.

Q: What’s your plan for the feedback session?

A: Shock and Awe! Get in the room, deliver my message, tell them what needs to change, and then get them out of my office!

When you consider how difficult it is to receive corrective feedback and then how hard it is for your boss to deliver it, you begin to see how truly challenging it is for both of you to have a meaningful and constructive conversation. A good place to start, we believe, is to examine some of the unwarranted assumptions our research shows many bosses have made that make the job even harder than need be.

Assumption 1: People don’t realize there is a problem

We asked a global sample of 3,875 people who’d received negative or redirecting feedback if they were surprised or had not known already about the problem that was raised. We were taken aback to discover that fully 74% indicated that they had known and were not surprised.

Very often, when we see someone performing poorly we say to ourselves, “If they only realized they had a problem they would do better.” But most of the time, that’s simply not so. A struggling employee may not realize how serious the problem is, but more likely, he or she is very much aware but hasn’t figured out how to do better. That means that simply pointing out the problem isn’t going to be all that helpful.

Assumption 2: It’s best to get it over quickly

Because both the person giving the feedback and the person receiving it are anxious, they both want to get it over quickly. That’s understandable: the human organism is wired to avoid pain. In practical terms, this usually means a meeting where the manager does a lot of talking and the subordinate remains silent. This might seem like the quickest and the kindest way to get things over with (on both sides), but it’s a terrible mistake.

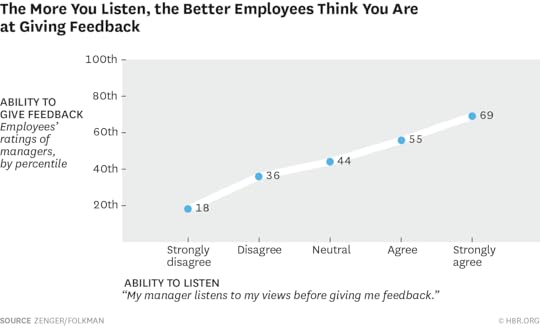

In the global study we also asked respondents to rate how well managers “carefully listened to the other person’s point of view about a problem before giving them feedback” and how effective the feedback was that their manager gave them. The graph below shows how strong the relationship is between these two factors. Simply put, the less people felt their managers listened to them, the more likely they were to believe that their managers were not being honest and straightforward. One could look at this the other way too – that is, those who felt strongly that their managers listened to them rated them high on their ability to give honest feedback.

In this assessment we also asked people whether they preferred — or wished to avoid — receiving negative feedback. In previous research we had found that people generally want to receive negative feedback, which they see as essential to their development, although managers generally prefer not to deliver it. But in this case, we found that subordinates whose managers did not listen to their point of view before offering up feedback were significantly less interested in receiving negative feedback.

So if shock and awe is a bad way to go, what would work better? We suggest managers begin by putting themselves in the place of their subordinates (which shouldn’t be hard, since after all everyone in an organization is subordinate to someone). Ask yourself as you prepare for that tough feedback session if your boss were giving you negative feedback, how would you like to receive it?

Would you like him to blast you with an intense and brief barrage of words, or would you prefer to be asked questions about the situation? Say, for instance, your boss was pointing out some specific mistake you’d just made: Would you want your boss to have his say and get it all over with? Or would you prefer to be given the opportunity to explain the circumstances and reconstruct what you were thinking at the time? Then, would you rather be told how to correct the situation? Or would you prefer to offer your own ideas for how you might do things differently next time? If you did that, would you then hope that your boss would offer support, advice, and some needed resources to help you? And if he said, “I will check back with you next week to see how things are going,” would that help keep you on track?”

It is something of a paradox that we crave constructive feedback and the same time we don’t want to give it. Perhaps getting past that paradox is a matter of remembering, when it’s your turn to be the giver, that it’s really so much better to receive. We can all think of some feedback that has been a gift – advice that has helped us perform better and made us more successful. When it comes to giving the gift of feedback, it’s worth the effort of putting yourself in the receiver’s frame of mind.

The Case Against Competing

Back in the Middle Ages when I was still with Fortune magazine, we had Warren Buffet in for an editorial lunch. With characteristic charming Midwestern self-effacement, the Great Investor waxed happy about a recent acquisition, the Buffalo Evening News. He loved the fact that it was the only player in what had become essentially a one-newspaper town.

“Gee, Warren,” I had the temerity to say to my fellow Nebraskan, “You don’t seem to like competition much.”

“I don’t, Walter” he replied heartily, “I don’t like it at all. I don’t know any good businessman who does.”

In subsequent pronouncements and actions, the Sage of Omaha has made clear his preference for businesses with “a moat” around them, a monopoly position or a formidable brand that spares them the necessity of constantly fighting off scrappy would-be rivals. The lesson seems clear: If you can avoid competing, by all means do so.

Buffet has done quite well following his own advice. But this isn’t a luxury afforded to all businesses, or even to most. There are libraries of books and articles offering counsel on how to steer clear of the profit-sucking aspects of competition—including via white spaces and blue oceans—and their advice can be invaluable. But I would go one step further and suggest that avoiding competition is a condition, or more precisely, a frame of mind, that more should aspire to. An overweening focus on beating the other guy, gal, or outfit is just as bad for your psychological and moral health as it is for your business.

The observation “comparisons are odious” dates back at least to the 15th century (long enough for Shakespeare to work a comic riff noting they’re also “odorous”). But with the rise of mass media (ranking everything—colleges, wines, doctors), social media (mean girls rule), and workforce management software, they stink even more. Particularly when applied to people, where they’re typically reductive, misleading, harmful, and say more about the person making the comparison than the persons compared. How many true winners divide the world into “winners and losers”?

Similarly, if your business and its people take competing as Priority Numero Uno, they’re prey to obsessing over comparisons—our market share vs. theirs, our cost position relative to them, our comparative product quality. While these are all good things to know, and may serve as goads to action, by themselves they rather miss the point. Did you or the founders of your enterprise get into business to take share, cut costs, and generally show the other guy up? One hopes—and suspects in the case of the best companies—that other ambitions were at work, other desires, dissatisfactions, or curiosities. Perhaps to create the best burger, medical device, smart phone, or advisory service. Such ambitions typically entail a focus on, even an obsession with, customers, clients, would-be users of your product. Someone out there that you can serve, in other words, not defeat. And to which banner do you expect to rally the best, most creative employees: “We can make something great” or “Kill the enemy”?

Insight Center

The New Ways to Compete

Sponsored by Accenture

Strategies for staying ahead.

Incitements to beat up the other guy too often lead to beating up yourself or your people. “Team,” accompanied by a heavy sigh or angry grimace, “I can’t believe you lost that sale to those devils from Zorch Corp.” Implicit message: “You are pathetic losers compared to that bunch of pitchfork wielders.”

It’s no better, and in fact may be worse, when the dialogue is purely internal: “Why can’t I ever do better than Dick and/or Diana Daring? WHAT’S WRONG WITH ME?” Answers are seldom in short supply. But the problem is that too tiresomely often they’re the same answers, not born of current competitive realities but from some chorus of nasty inner voices carried around since childhood.

Adam Phillips, the British psychoanalyst, recently wrote an essay in the London Review of Books, titled simply “Against Self-Criticism.” A Freudian himself, Phillips invoked the Founding Father’s tripartite division of the human mind into id (that churning cauldron of instinctual energies), super ego (sitting above it all, cheering or booing), and ego (sandwiched between the two, desperately trying to mediate between them and the outside world). The super ego, we are reminded, itself has two parts, the conscience (punitive, critical, nagging away at us) and the ego ideal (holding up the image of all the excellence we might become).

To simplify Phillips a bit, the problem with listening overmuch to the conscience is that the conversation gets boring really fast—it’s just the same old deflating criticisms hammering away at us like propaganda. You don’t learn anything new.

Which is precisely the danger to a business from too fanatic a concentration on competing. The corporate mindset gives way to “Why do we keep screwing up?”—perhaps interrupted by equally mindless episodes of chest-thumping if you happen to win. Lost along the way are, “Gosh, those devils over at Zorch seem to be doing something interesting. What can we learn from them?” Or, “We set out to make the best industrial fasteners in the world. What can we do today to move a little closer to that goal?”

And you can also take a cue from one of the hardest-throwing and most enduring pitchers who ever lived. Probably the best known quotation from the eminent “management philosopher” Satchel Paige is “Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.” But perhaps even more relevant here is another recommendation attributed to him: “Work like you don’t need the money. Love like you’ve never been hurt. Dance like nobody’s watching.”

Handling Emotional Outbursts on Your Team

Do you have a crier on your team? You know, the one with tissue-thin skin who expresses frustration, sadness, or worry through tears. Or maybe you have a screamer, a table pounder who is aggressively invested in every decision. These kinds of emotional outbursts are not just uncomfortable; they can hijack your team, stalling productivity and limiting innovation.

Don’t allow an emotional person to postpone, dilute, or drag out an issue that the business needs you to resolve. Instead, take the outburst for what it is: a communication. Emotions are clues that the issue you are discussing is touching on something the person values or believes strongly in. So look at outbursts as giving you three sets of information: emotional data; factual or intellectual data; and motives, values and beliefs.

We get stuck when we only focus on the first two — emotions and facts. It’s easy to do. When someone starts yelling, for instance, you might think he’s mad (emotion) because his project has just been defunded (fact). And many managers stop there, because they find feelings uncomfortable or aren’t sure how to deal with them. That’s why the first step is to become more self-aware by questioning your mindset around emotions. There are several myths that often get in a team leader’s way:

Myth #1: There is no place for emotion in the workplace. If you have humans in the workplace, you’re going to have emotions too. Ignoring, stifling, or invalidating them will only drive the toxic issues underground. This outdated notion is one reason people resort to passive-aggressive behavior: emotions will find their outlet, the choice is whether it’s out in the open or in the shadows.

Myth #2: We don’t have time to talk about people’s feelings. Do you have time for backroom dealings and subterfuge? Do you have time for re-opened decisions? Do you have time for failed implementations? Avoiding the emotional issues at the outset will only delay their impact. And when people don’t feel heard, their feelings amplify until you have something really destructive to deal with.

Myth #3: Emotions will skew our decision making. Emotions are already affecting your decision making. The choice is whether you want to be explicit about how (and how much) of a role they play or whether you want to leave them as unspoken biases.

You and Your Team

Emotional Intelligence

Feelings matter at work

With your beliefs in check, you’ll be better able to get beyond the emotion and facts to the values the person holds that are being compromised or violated. This is critical because your criers and screamers are further triggered when they don’t feel understood. The key is to have a discussion that includes facts, feelings, and values. People will feel heard and the emotion will usually dissipate. Then you can focus on making the best business decision possible.

Here’s how.

Spot the emotion: If you wait until the emotion is in full bloom, it will be difficult to manage. Instead, watch for the telltale signs that something is causing concern. The most important signals will come from incongruence between what someone is saying and what their body language is telling you. When you notice someone is withdrawing eye contact or getting red in the face, acknowledge what you see. “Steve, you’ve stopped mid-sentence a couple of times now. What’s going on for you?”

Listen: Listen carefully to the response, both to what is said and what you can infer about facts, feelings, and values. You will pick up emotions in language, particularly in extreme words or words that are repeated. “We have a $2 million budget shortfall and it’s our fourth meeting sitting around having a lovely intellectual discussion!” Body language will again provide clues. Angry (leaning in, clenched jaw or fists) looks very different from discouraged (dropping eye contact, slumping) or dismissive (rolling eyes, turning away).

Ask questions: When you see or hear the emotional layer, stay calm, keep your tone level and ask a question to draw them out and get them talking about values. “I get the sense you’re frustrated. What’s behind your frustration?” Listen to their response and then go one layer further by testing a hypothesis. “Is it possible that you’re frustrated because we’re placing too much weight on the people impact of the decision and you think we need to focus only on what’s right for the business?”

Resolve It: If your hypothesis is right, you’ll probably see relief. They might even express their pleasure “Yes, exactly!” You can sum it up “We’ve talked about closing the Cleveland office for two years and you’re frustrated because you believe that the right decision for the business is obvious.” You’ve now helped your team member articulate the values he thinks should be guiding the decision. The team will now be clear on why they are disagreeing. Three people might jump in, all talking at once “We are talking about people who have given their lives to this organization!” Here we go again…Use the same process to reveal the opposing points of view.

Once everyone is working with the same three data sets — facts, emotions, and values — you will be clear what you need to solve for, in this case, how will we weigh the financial necessity with the impact on people. Although taking the time to draw out the values might seem slow at first, you’ll see that issues actually get resolved faster. And ironically, as you validate emotions, over time people will tend to be less emotional as it’s often the suppressing the emotions or trying to cobble together facts to justify them that was causing irrational behavior.

If you’re leading a high performing team, you better be ready to deal with uncomfortable, messy, complex emotions. If there’s a situation you have failed to address because of an emotional team member, spend some time thinking about how you will approach it and then go have the conversation. Today. You can’t afford to wait any longer.

The 4 Types of Small Businesses, and Why Each One Matters

America loves small businesses. A 2010 poll by The Pew Research Center found that the public had a more positive view of them than any other institution in the country – they beat out both churches and universities, for instance, as well as tech companies. As Janet Yellen pointed out in a speech last year, “the opportunity to build a business has long been an important part of the American Dream.”

Governors, mayors and presidential candidates are therefore eager to declare their support for small businesses, but what do we mean by “small” and why do they matter? This is the part where we’re usually told that it’s startups that matter, not small businesses, since they’re the ones that create all the new jobs. There’s some truth to that, but it’s misleading as well. A blanket policy that just tries to create another Silicon Valley can turn out to be a disaster.

Sure, the local dry cleaner isn’t going to employ radically more people next year than it did this year. But these Main Street businesses employ a lot of Americans –as many as 57 million– and the policies they need are not the same as the ones required by startups. If policymakers really want to help small businesses — and they should — they need to understand that not all of them are alike. Each type has a way it contributes to employment and the vibrancy of the American economy.

There are 28 million “small businesses” in America, defined as firms with fewer than 500 employees, and they fall into four different segments:

(Note that these segments are not mutually exclusive. They are intended to represent different categories of firms of interest to policy makers.)

Most of these small businesses don’t actually have employees. Almost 23 million are sole proprietorships, covering a wide range of sectors, from consultants and IT specialists to painters and roofers. While only about 15 million of the self-employed earn receipts of over $10,000, recent research shows that sole proprietorships are achieving record profit margins—and numerous indicators predict the number of these businesses will continue to grow as technology allows more geographic flexibility and a continuing number of baby boomers take steps to open their own firms. They provide income to their owners, but by definition are not job creators.

The next-largest segment of small businesses is comprised of what I call Main Street entrepreneurs. These are the dry cleaners, restaurants, car repair operations, and local retailers that are part of the fabric of our daily lives. There are about 4 million of them, and they employ a significant portion of the workforce. Many of these businesses exist largely to support a family and are not principally focused on expansion. While these businesses have high churn rates—opening and closing frequently– they are critical to America’s middle class.

An important but less well-documented type is comprised of an estimated 1 million small businesses that are part of commercial and government supply chains (referred to as suppliers). These businesses are often focused on growth, domestically or through exports, and operate with a higher level of management sophistication than Main Street firms. These are companies like Hooven-Dayton in Miamisburg, Ohio which provides labels for Tide and Mr. Clean products. A robust network of small suppliers is important to the long-term competitiveness of large U.S. corporations and for companies considering moving production back to the U.S. from offshore. For example, a research and supplier park established in Prince George, Virginia in 2010 was part of bringing Rolls Royce production to the area. As Harvard Business School’s Michael Porter and Jan Rivkin have noted, strong supply chains bring “low logistical costs, rapid problem solving and easier joint innovation.”

Of the remaining small businesses, about 200,000 qualify as high growth startups and firms. These are the companies that punch above their weight when it comes to job creation. A study by economist Zoltan Acs in 2008 found that only about three percent of all businesses can be classified as high growth businesses or “gazelles,” but that they are responsible for 20 percent of gross job creation. A recent breakthrough by MIT’s Scott Stern and Jorge Guzman showed that the 5% of firms registered in Massachusetts that delivered 77% of the growth outcomes could be identified by growth factors evident at the time of their original business registration. These high growth firms have a disproportionate effect on the U.S. economy.

Treating all small businesses the same can lead to potentially misleading declarations, and bad policy. For example, a “mom and pop” Main Street shop has different financing needs than a high‐tech startup. One might need a bank loan while the other might need a patient equity investor like an angel or venture capitalist. Setting up an innovation ecosystem around a university or an emerging technology helps potential high-growth entrepreneurs, while downtown revitalization can help local businesses from the Main Street category. (In a forthcoming article we will review how in several policy areas — access to capital, skills and the creation of innovation ecosystems — the right policy depends on the type of small business you are trying to help.)

Once policymakers understand the different types of small businesses and hear that start-ups drive the bulk of new job creation, they are sometimes tempted to focus solely on those growth firms. That is a mistake. Just as important as differentiating between small businesses is realizing why each one matters.

Suppliers are an important, and underappreciated, part of this equation as they generate high paying jobs in both the small manufacturing and service sectors. And the success of large companies and growth start-ups often depend on a strong cluster of suppliers.

Sole proprietorships and Main Street businesses, for their part, can provide a critical pathway to economic mobility. And while Main Street may not create a lot of net new jobs, it does employ a large number of people. These businesses are also the restaurants, shops, and storefronts that shape and reflect a community’s identity and values.

Each type of small business matters for different reasons. The key is to remember that what helps one group will not necessarily have the equal or any impact for another. Praise for small businesses is warranted because of the role they play in driving an innovative and competitive economy and promoting social mobility, but when it comes to helping them succeed it’s essential to avoid treating them all the same way.

A Refresher on Cost of Capital

Babo Schokker

You’ve got an idea for a new product line, a way to revamp your inventory management system, or a piece of equipment that will make your work easier. But before you spend the company’s hard-earned money, you’ve got to prove to your company’s leaders that it’s worth the investment. You’ll likely be asked to show that the return on the investment will be better than your company’s cost of capital. But are you sure you know exactly what that is? And how your company uses it?

To learn more about this commonly used business term, I spoke with Joe Knight, author of the HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment and co-founder and owner of www.business-literacy.com.

What is the cost of capital?

“The cost of capital is simply the return expected by those who provide capital for the business,” says Knight. There are two groups of people who may put up the capital needed to run a business: investors who purchase stock and debt holders who buy bonds or issues loans to the company. Any investment a company makes has to earn enough money that investors get the return they expect and debt holders can be repaid.

You may be wondering if this is the same as discount rate and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, explains Knight. Though there is typically a distinction. “At most companies, the cost of capital is a mechanical calculation done by the finance people. Then the management team takes that number and decides on the discount rate, or hurdle rate, that you have to exceed to justify an investment,” he says.

In many businesses, the cost of capital is lower than the discount rate or the required rate of return. For example, a company’s cost of capital may be 10% but the finance department will pad that some and use 10.5% or 11% as the discount rate. “They’re building in a cushion,” says Knight, which is not a bad thing. And how much they pad it will depend on their appetite for risk. A risk-averse company might raise the discount rate even further, as high as 15-20%. But if the business is looking to stimulate investments, they might lower the rate, even if just for a period of time.

What do companies typically use it for?

There are two ways that cost of capital is typically used. Senior leaders use it to evaluate individual investments and investors use it to assess the risk of a company’s equity.

Further Reading

HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment

Finance & Accounting Tool

Joe Knight

29.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Let’s look at that first instance. “A wise company only invests in projects and initiatives that exceed the cost of capital,” says Knight. So once the finance department, CFO, or treasure department has determined what the rate is, managers know that is the number to beat if they want to win support for their projects or proposals. “If you make investments that don’t get a return that exceeds the cost of capital, you’re encouraging investors to go elsewhere,” explains Knight. “You’re basically saying that we’re not getting the return you expected.” Therefore it’s important that managers — often with the help of finance — take a close look at potential projects to make sure they exceed the cost of capital

Now for the second instance. Although this use is less common, investors will look at an aspect of the cost of capital — the beta or volatility (more on this in the next section) — which will help them understand if a stock is a risky investment or not.

How do you calculate the cost of capital?

In reality, few managers will ever make this calculation. “This is the job of finance professionals,” says Knight, “and to the average manager what goes into determining the cost of capital can often be opaque.” Here’s a brief overview (based on the example in Knight’s book, Financial Intelligence):

The first step is to calculate the cost of debt to the company. This is pretty straightforward. You take all of the money that the company has borrowed and look at the interest rates you’re paying. So if the company has a credit line with a rate of 7%, a long-term loan at 5%, and bonds that it uses to make acquisitions at 3%, you add that all up and calculate the average. Let’s say it’s 6%. Then because interest on debt is tax deductible you multiply it by the corporate tax rate (which is usually around 30% in the U.S.). The formula looks like this:

Cost of debt = average interest cost of debt x (1 – tax rate)

So you take your 6% and multiply it by (1.00-.30). In this case the cost of debt = 4.3%.

Now, set that number aside and move over to the equity calculation. This is a much more theoretical number and takes into account beta (risk) and prevailing interest rates.

The formula looks like this:

Cost of equity = risk-free interest rate + beta (market rate – risk-free rate)

Beta measures the volatility of the company’s stock compared to the market. The higher the beta, the riskier the stock is, according to investors. If a stock rises and falls at close to the same rate as the market, the beta will be close to 1. If it tends to rise and fall more than the market, it might have a beta closer to 1.5. And if it doesn’t fluctuate as much as the market, like a utility for example, it might be closer to 0.75.

The market rate is the expected return on the stock market right now. There is typically lots of debate about this number but generally it falls between 10-12%. The risk-free rate is the return you’d get on a risk-free investment, such as a treasury bill (somewhere between 1-3%). This figure can also be debated.

Let’s assume that that the company’s beta is 1, that it uses 2% for the risk-free rate and 11% for the market rate, then you’d get the following calculation:

2% + 1 (11% – 2%) = 11%

Note how important the beta can be. For example, if the company’s beta was 2 instead of 1, the cost if equity would be 20% instead of 11%. That’s quite a difference.

Now the next step is to take your two percentages – the cost of debt (4.3% in the example above) and the cost of equity (11%) – and weight them according to the percentage of debt and equity the company uses to finance its operations. Let’s assume the company uses 30% debt and 70% equity to run its business. So you’d do the following final calculation:

(0.3 x 4.3%) + (0.7 x 11%) = 8.99%

This is the company’s WACC.

Keep in mind that this is a number used to evaluate future investments so there is a lot of projecting going on. “You’re using the current structure of interest rates and business conditions to calculate a future return and there’s an implicit assumption that your current beta will be the same going forward. In a volatile market, that’s never true,” explains Knight. It’s hardly an exact figure and is, in fact, a very theoretical calculation. “Like everything in finance it’s based on a lot of estimates and assumptions. It may look like a hard, fixed number — but it’s far from that.”

What mistakes do people make when using cost of capital?

The biggest mistake managers make, according to Knight, is taking the number at face value. “Sure, some grouse about the number, claiming that it’s too high and it limits the investments that they can reasonably make, but most just take the figure handed to them by finance.” This is problematic because the cost of capital has a big influence on what you’re able to do. “It’s not something you should just accept. You should absolutely challenge it,” says Knight.

He recommends asking your counterpart in finance: What did you use for cost of equity? How did you come up with cost of debt? Or why do we use 12% as the market rate? “You can miss a lot of opportunities when you have to hit a higher standard,” Knight says, so it’s worth asking tough questions and seeing if you can negotiate the rate. What you want the rate to be will depend on the type of project you’re taking on. For example, if you’re a manager proposing a whole new R&D software for a new product that you’ve never done before, you want to use a high number, probably higher than your WACC, to show that this type of risky investment is worth it. But if your order processing system is breaking down and you need a new one, you can use a lower rate since this is part of the nuts and bolts infrastructure for running your business. After all, if you don’t have an order processing system, you’ll be out of business.

Another mistake managers make is to pad the number. “They like to bump it up to be safe,” explains Knight. If the corporate cost of capital is 12%, then a manager might think, I’m going to use 15% to be on the safe side. But the number likely already includes a cushion. Don’t up it again or you will be making things unnecessarily hard on yourself.

When finance tells you that your new project or initiative needs a return that beats the company’s cost of capital, it’s helpful to know what that figure is and how it’s calculated. Armed with this information, you’ll be able to better make the case that your idea is worth the company’s investment.

When It’s Safe to Rely on Intuition (and When It’s Not)

We often use mental shortcuts (heuristics) to make decisions. There is simply too much information coming at us from all directions, and too many decisions that we need to make from moment to moment, to think every single one through a long and detailed analysis. While this can sometimes backfire, in many cases intuition is a perfectly fine shortcut. However, intuition is helpful only under certain conditions.

The most important condition is expertise. If I am a novice mountain climber, then my intuition on whether or not a given route is safe is not going to be accurate – I have no previous knowledge on which to base that decision. Similarly, if a financial history professor is making an investment decision, her expertise in financial history does not automatically extend to financial investments, thus she should not rely on intuition for those decisions.

It takes a surprising amount of domain-specific expertise to develop accurate intuitive judgments – around 10 years, according to the research. And during those 10 years, repetition and feedback are essential. For example, a TV show producer, in order to develop accurate intuitive judgment about new TV shows, would need to repeatedly engage in making decisions about new TV shows and receive rapid and accurate feedback on whether those decisions were good ones. Eventually, this repetition and feedback becomes embedded as intuitive learning and can be used to make fast and effective intuitive decisions about new shows.

Learning can also happen subconsciously over time (also called “implicit learning”). For example, a factory foreman spends every day scanning the factory environment, ensuring it is safe and workers are productive. After many years of this, the foreman learns to recognise the most important signals or patterns of activity, ignoring irrelevant information. Thus the experienced foreman can respond to conditions on the factory floor in a rapid, accurate, and intuitive way.

The second condition relates to the type of decision you’re making. To be conducive to intuitive judgment, the problem should be unstructured. An unstructured problem is one that lacks clear decision rules or has few objective criteria with which to make the decision; for example, aesthetic judgments regarding whether a new movie or art exhibit will be a success, or political judgments regarding the best way to get a new initiative approved, or human resource judgments regarding the best way to resolve a conflict between employees.

The types of problems that do not benefit from intuition are ones that have clear decision rules, objective criteria, and abundant data with which to perform an analysis. In making a medical diagnosis, for example, computer algorithms tend to be more accurate than an experienced medical doctor’s judgment. This is because the computer can calculate the probability that a particular set of symptoms indicate a particular illness while also factoring in the patient’s age, sex, and other relevant factors. The human brain, when faced with such a large amount of data, must use heuristics, and those mental shortcuts can be imperfect. With hundreds of possible symptoms and illnesses, it would be very difficult for any individual doctor to develop the depth of expertise required to make an accurate intuitive judgment on a particular illness.

Of course, most decisions lie somewhere between the aesthetic judgment and computer algorithm. In buying a new car, you can feed data into a computer algorithm to calculate the most efficient and economical model for your needs, but the final decision will be influenced by your reaction to the look and feel of the car – something a computer cannot assess for you. Likewise, the decision to sell your product in a new market can be analysed quantitatively, but the final outcome will be affected by the new customers’ feelings about the product – something a computer cannot predict. Nonetheless, if there are clear decision rules that can be used to create an algorithm, if relevant data are available, and if the decision will be assessed with purely objective criteria (i.e., not aesthetic judgments or feelings), then an analytical approach is likely to be more helpful than intuition in reaching the best decision.

Finally, the third condition is the amount of time you have available. If you only have a small window in which to decide, intuition can be helpful because it is faster than a detailed analysis. This is especially true when there is very little information with which to make the decision. When information and time are scarce, using heuristics such as intuition can often be as effective as a rational approach. However, lack of time by itself is not necessarily a good reason to use intuition. As much as we want to believe that our intuition is telling us something meaningful, it is still a shortcut that could lead us down the wrong path.

Intuition is essentially a feeling, and we do not know the source of that feeling. It may be that our aversion to a particular option is reflecting a hidden nervousness, insecurity or fear of the unknown. If so, then our intuition will lead us to reject a perfectly good option. At the same time, research has found that feelings are relevant – even essential – to decision-making; a study of patients with a tumour in the emotion area of the brain found they could generate alternatives but were unable to choose one.

Ultimately, it may be that we should use both intuition and analysis. There may be times when intuition helps narrow down the options, which can then be analysed in a logical and rational way. Or the reverse: an initial detailed analysis may identify a few options that seem equally good, and intuition is needed to single out the right one. But before you decide to trust your gut, ask yourself: Am I an expert? Is this an unstructured problem? And how much time do I have to choose?

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers