Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1298

April 24, 2015

The Remedy for Unproductive Busyness

Raise your hand if you feel busy. Keep it up, still, if you think the busyness is hurting your productivity. If your hand is still up, then you should keep on reading.

It’s very easy to succumb to the temptation of staying busy even when it is counterproductive: It is the way our brains are wired. But there is a remedy that we can employ to translate that predisposition into productivity.

Research points to two reasons we often feel busy (but not necessarily productive) — and they are both self-imposed.

People have an aversion to idleness. We have friends who will, by choice, drive miles out of their way to avoid waiting for a few minutes at traffic lights, even if the detour means their journey takes more time. Research suggests that the same applies to work, where many of the things we choose to do are merely justifications to keep ourselves busy.

We have a bias toward action. When faced with uncertainty or a problem, particularly an ambiguous one, we prefer to do something, even if it’s counterproductive and doing nothing is the best course of action.

Consider the case of professional soccer goalies who need to defend against penalty kicks. What is the most effective strategy for stopping the ball? Most of us think that if we were in their shoes, we would be better off jumping to the right or to the left. As it turns out, staying in the center is best. Research has found that goalkeepers who dive to the right stop the ball 12.6% of the time and those who dive to the left do only a little better: They stop the ball 14.2% of the time. But goalies who don’t move do the best of all: They have a 33.3% chance of stopping the ball.

Nonetheless, goalies stay in the center only 6.3% of the time. Why? Because it looks and feels better to have missed the ball by diving (an action) in the wrong direction than to have the ignominy of watching the ball go sailing by and never to have moved. The action bias is usually an emotional reaction to the sense that you should do something, even if you don’t know what to do. By contrast, hanging back, observing, and exploring a situation is often the better choice.

The action bias can lead us to jump into developing solutions before we fully understand a problem. In one study we conducted, we found that people feel more productive when they are executing tasks rather than when they are planning them. Especially when under time pressure, they perceived planning as a waste of time — even if it actually leads to better performance than jumping into the task head-first.

Choosing to be busy over real progress can be an easy choice; being productive, by contrast, is much more challenging. What helps? Reminding ourselves that taking the time to reflect can help make us more productive.

In a study we conducted at the tech-support call center at Wipro, a business-process outsourcing company based in Bangalore, India, we found that thinking improves performance. We asked groups of employees going through training to spend the last 15 minutes of each day writing about and reflecting on the lessons they had learned that day. Other employees just kept working at the end of the day for those 15 minutes and did not receive additional training. The result? Over the course of one month, the reflection group increased its performance on the final training test by an average of 22.8% more than the control group of trainees who had been working 15 minutes longer per day!

Reflection has such beneficial effects on performance because it makes us more aware of where we are, gives us information about our progress, and lends us the confidence we need to accomplish tasks and goals.

This type of thinking is also beneficial when it takes the form of planning. In one field study, Oriana Bandiera of the London School of Economics and her colleagues had 354 CEOs of listed Indian manufacturing firms record the activities they engaged in at work over the course of a week. The research team identified two types of CEOs. The first engaged in advance planning, interacted primarily with his or her direct reports, and was more likely to have meetings with many people who performed different functions. The second type of CEO was less likely to plan ahead and more likely to meet with outsiders in one-to-one meetings. The most successful were the planners, who were linked to higher firm-level productivity and profitability.

Learning to stay in the center, as goalkeepers should, involves stepping back, allocating time to just think, and only then taking action. Through reflection, we can better understand the actions we are considering and ensure they are the ones that will make us productive. As a mentor once told one of us: “Don’t avoid thinking by being busy.”

An Anti-Creativity Checklist for 2015

Five years ago I published a version of this tongue-in-cheek checklist on HBR.org that highlighted how organizations kill creativity. It really touched a nerve—people flooded the post with examples from their own organizations of how their managers and colleagues stifled innovation. Even clichés like “We’ve always done it this way” seemed to be alive and well back then. Given all the talk in recent years about unleashing creativity in organizations, I wondered whether the same creativity killers are still at work today. So, I’m posting a slightly edited version of the original video to ask viewers around the world what’s changed. What happens in your organization today that shuts down creative thinking? Please post your examples of anti-creativity in the comments section. Thanks, and enjoy.

Video Metrics Every Marketer Should Be Watching

Roughly half of companies currently use video in their marketing strategies, and two-thirds of marketers expect to do so in the near future. But how do they actually measure the success of these videos? For many marketers, the key focus is view count. But if you look under the hood of what really drives a video strategy, it becomes clear that view count is primarily a vanity metric. You have no guarantee that these views are driving your business forward.

Even if your goal for the video is simply nebulous “branding” or “exposure,” there are better ways to measure ROI.

The Shortcomings of View Count

Why is video view count inadequate? The argument has echoes of the debate over how we value pageviews on websites. First, video view count tells you nothing about your audience. Who is watching is just as important as the number of people watching. If the audience is made up of people who don’t fit your target customer profile, those views are fairly worthless. You’d benefit more from a smaller view count by people who align with your target customer. Companies need data on who their viewers really are.

Second, view count sheds no light on whether your videos are actually resonating. If most of your viewers are watching your video all the way to the end, that’s a pretty telling sign. It indicates that you’ve chosen a good topic and created content others find valuable. If, instead, people opt out of your video after three seconds, you might need to take a different approach. Looking at metrics like these can help determine whether you chose the wrong topic, used the wrong delivery, or simply put the video in the wrong place.

Video Metrics that Actually Tell You Something

Who is watching: Ideally, you’re using a professional player that matches IP addresses of viewers with the email addresses in your system. In this case, if your site visitors have volunteered their email address, (through a gated piece of content, for example,) you’ll be able to see which videos they watch across your website and landing pages. This benefits your business in a few respects. First, you can nurture these prospects in a segmented way. Have they watched your product overview? If so, send them a link to the pricing video. Have they watched just the pricing video? If so, share the product video. Second, it lets your sales team have more targeted conversations. Because a salesperson can see exactly which videos (and which parts of the video) a prospect has watched, they can focus on the topics that are most relevant to that customer. Finally, you can further gauge whether the right people are viewing your content if you cross-reference video viewing activity with other user behavior in your CRM.

Play rate is the percentage of people who click on the video divided by the total number who access the page where it’s embedded. While play count is an absolute number, play rate indicates how appealing your video is, in the context of those who visited the page. A high play rate means that you’ve done a good job creating the right context for your video. For instance, it suggests whether the description adequately reflects the topic, whether the thumbnail image is appealing, and whether your video is prominent enough to attract attention. Ideally, we like to see play rates above 50%, especially if the video is the “main event” on the page. Focusing on play rate helps you optimize the context in which people view your video. As a sidenote, there are ways to drive up the playrate, such as autoplaying your video. We generally dissuade people from autoplaying, given that it can make site visitors feel tricked or blindsided. But there are certain contexts and applications that go over better than others, such as a silent looping autoplay.

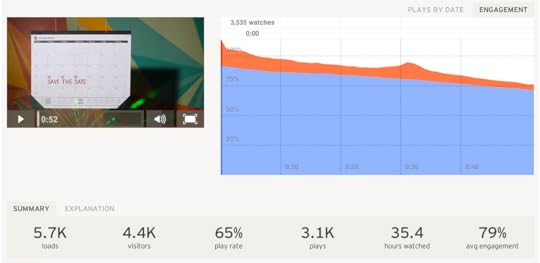

Average engagement: On average, what proportion of your video do viewers watch? Clearly, more is better; you want most people to watch your video all the way to the end. If many people click “play” only to exit the video immediately, you’re not meeting viewer expectations and your message isn’t having much impact. A high average engagement means that you’re sharing valuable information in a clear and interesting way. Ideally, you can also see where people are rewatching your video. For instance, take a look at the graph below, which shows user engagement for a video we made about our upcoming conference. The graph below shows average engagement over time, (indicated in blue). The red area indicates where people chose to re-watch this video. The red blip around 32 seconds shows that something attracted a lot of people’s attention there. In this case, it was a particularly cool camera trick. The blip tells us that perhaps we should use more camera tricks, or even make some videos about how to do the camera trick we used.

Action completions: Focus on the number of people who complete your calls to action and whether using video helps drive this number up. Does having a customer testimonial on a product page result in more sales than a page without the video? Test it. You can also test different types of video: maybe an explainer video that showed how to use the product would result in even more sales than a testimonial. You should also pay attention to whether having video on the page increases call-to-action completion rates for actions not located within the video itself — such as testing a newsletter sign-up immediately below the video, or as post-roll on the video itself.

Comments and social shares: if someone cares enough to comment on your video (or share it with their own audience), this means you’re making the right content. Not only does this get you in front of new audience members, but the credibility of the “sharer” rubs off on you. Furthermore, you can start creating a community via comments. Ideally, a rich discussion springs up around your video, with the video itself as the centerpiece. This fosters a sense of ownership by those who choose to actively participate by commenting or sharing the content. For example, this video prompted the creation of an ad hoc community, with participants sharing valuable information that empowers one another. These participants are adding real value to our website at no cost to us.

Non-Video Metrics to Watch

There are other metrics that can indicate whether you’ve made a successful video but that aren’t “video metrics” per se. Still, your videos can have a direct impact on their outcomes:

Keep an eye out for increased time on page (how long someone stays on your webpage). Having a video on your page should increase the time people spend interacting with your business. Take a look at the average time on page before and after you launch a video, in order to gauge the impact of that content.

Also look for decreased bounce rate. Ideally, your video prompts people to look for other great content you’ve made, rather than just leaving your site after viewing one page. You can facilitate this process by using mid-roll links (or other calls to action) at the end of a video or surrounding the video on the page.

The metrics you choose to watch can have a tremendous impact internally. Get others on the same page about the metrics that matter, so that everyone is working towards the same goals at the same time.

Watching the right metrics allows you to use video strategically. They indicate whether a video is accomplishing the business goal you want it to. Rather than focusing on quantity — how many people watched a video — focus on the metrics that indicate perceived quality. This will help your business focus energy on creating content that not only delights your customers, but also increases revenue.

CEOs, Stop Trying to Manage the Board

It’s understandable that most CEOs try to manage their boards. With directors often attempting to take a more active role in decisions these days, CEOs naturally feel a bit threatened. They’re trying to lead a group of people who typically lack the time or expertise to fully understand what’s going on — but who have real power.

At most companies, despite all the best intentions, managing the board usually means keeping directors at arm’s length. Most CEOs I’ve known are inclined to give out just enough information to satisfy their fiduciary obligations, often in highly structured meetings that leave little to chance. They hold off on revealing the deeper challenges or complexities that might provoke tough questions.

But as I learned over the course of my career, there’s a better approach with boards. A CEO can work in partnership with directors without sacrificing his or her authority — and thereby accomplish far more than is possible with an arm’s-length relationship. It’s all a matter of developing trust. In my five years as CEO of The Hartford, a Fortune 100 insurer, winning trust was crucial to turning around the company in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Building trust can be a delicate thing, but it isn’t magic. You don’t need special charisma. All you really need is courage and self-confidence.

The first step is to show that you trust your directors. In practical terms, that means not trying to stage-manage board interactions. When I took over at The Hartford, the management team took up most of our board meetings going through long slide decks. I got rid of that barrier. We distilled the most important information into pre-reads for the directors to study in advance. The meetings themselves, aside from the CFO’s report on financials, focused on discussions of the main issues. Real transparency, I learned, isn’t so much in the numbers, but in open conversation.

That wasn’t easy at first for my executives, who were used to wielding their slide decks to control their presentations. I had to coach them not to worry and to remember that directors were genuinely interested in their businesses and in getting to know them as managers. So they should just be open to the discussions that came up.

These unscripted meetings not only freed directors to ask more questions, but also gave them more of a window into the company. They got to see the other executives in action, including my potential successors.

It’s important to remember that boards see only a small part of you, and even less of the company. They visit for a day or two and get a snapshot. How you work with them is often as important as the substance of what you say. If you give the board unfettered access to executives, you’ll build trust with the directors as well as with your management team. Openness and transparency in board meetings over time can go a long way toward making everyone comfortable with everyone else.

Still, those steps weren’t enough for me to build a strong basis of trust. It’s one thing to allow open discussion on the usual company topics. But what about the issues that involved me personally? How could I get the directors to trust me on my own performance? Obviously a CEO will want to maintain some discretion here. But openness on even these issues can pay off enormously.

A year into my tenure, a senior executive quit abruptly and, on the way out, criticized my management style to the board. I was concerned enough to get a coach, who conducted a full 360-degree feedback process for me. But instead of just telling the directors about the coaching, I decided to give them an overview of my coach’s findings. Her report was generally positive, but it had some tough parts in it, and I decided to discuss these openly. It may have been risky, but it helped to break the ice. The board members felt relaxed enough to give me some feedback of their own. My lead director even became something of a second coach. All of this was invaluable, and it wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t made myself vulnerable in the first place.

That trust made a big difference in 2012, when an activist investor challenged us to restructure the company. We were still in the process of developing our new strategy, and the stock price was disappointingly low. The controversy could have led to my departure and, more important, a costly delay in the company’s revival. Instead the board stayed unified and we stuck to our plan, which turned out to be a better approach than the strategy the activist was pushing.

All along the way, as we developed trust, I grew to welcome the board members’ tough questions. I could see they were focused on helping me protect and improve the company. A CEO’s job is hard enough. One of your biggest responsibilities is to avoid making dumb decisions. Wouldn’t you want all the directors to feel comfortable challenging you and each other?

Trial and Error Is No Way to Make Strategy

For decades now, both consultants and academics have been arguing that the world has become so fast paced, so hypercompetitive, so complex, so ambiguous, and so uncertain, that the death knell has sounded for strategy’s central concept of sustainable competitive advantage. Competitive advantage has become fleeting, easily disrupted by actors both inside and outside an industry.

The common prescription for competing in the absence of competitive advantage is the concept of strategic agility or adaptability, which involves rapid pivots, self-disruption, and abundant experimentation. Success, in this worldview, often entails mimicking the lean startup, strategically maneuvering with nimbleness and flexibility.

Perhaps. But personally, I find it hard to agree with this prescription. Look at the big corporate success stories of the new economy: Apple, Google, FedEx, Amazon, Alibaba, Mittal, Facebook, Costco, Starbucks, and Express Scripts. Can you really say that these companies are not profiting from a sustained competitive advantage?

Insight Center

The New Ways to Compete

Sponsored by Accenture

Strategies for staying ahead.

My bigger concern, though, is that this intense debate about the death of competitive advantage promotes a profound misunderstanding about strategy. Sustainable competitive advantage is an important strategic concept, to be sure. And creating a sustainable competitive advantage can even be a corporate goal. But it is not a firm’s ultimate strategic goal.

So what is? My contention is that the true object of strategy is to sustain value creation, which demands a capacity to relentlessly create and capture new value. The difficulty with setting a given market position or competitive advantage as your strategy’s goal is that its direction-giving guidance is effectively dead upon your arrival. It fails to reveal what’s next.

Rather than merely having a path to a given competitive advantage, firms need what I call a corporate theory — a theory that provides ongoing guidance that reveals a succession of paths to new competitive advantages, new sources of value. This corporate theory has three components. It offers:

Foresight into an industry’s future evolution.

Insight into what is distinctive and uniquely valuable among the assets and capabilities of the firm.

Cross-sight into how various combinations of currently owned and externally available assets and opportunities can be combined to create value.

When you have a well-crafted corporate theory, it becomes clearer to you what your next strategic move or competitive advantage will be. Each of these moves can be seen as a test of your theory. If the move works out and creates value, then the theory it tests is validated.

As I’ve described elsewhere, years ago as an undergraduate I toured the Xerox PARC research facility and observed much of the same technology that Steve Jobs had famously observed about eight months prior to my visit.

But what he saw and what I saw could not have been more different. I saw some cool technology. He saw key elements vital to testing and composing his emerging theory of value creation. This theory prompted a succession of strategic moves with outcomes that continue to deliver vast amounts of value for Apple shareholders. Similarly, remarkably valuable strategic experiments have flowed for decades from a corporate theory that Walt Disney composed many years ago. While not all have proven valuable, most certainly have.

This is very much like scientific progress. Scientists design experiments to test a theory, and the more thought-through the theory is, the more likely it is to be validated. Experimentation around less-thought-through theories produces more failures. This may be acceptable if your goal is to simply create and test new theories (which is often how academics compete) but there’s no doubt that experimenting on underdeveloped theories is more wasteful than experimenting on well-developed theories. And in business, where strategic experiments involve large investments and real jobs, experimentation uninformed by theory is a hugely value-destroying process.

It’s here that I really take issue with the agility school of thought. The prescription boils down to this: In a world where sustainable competitive advantage is harder to come by, you need to experiment more in order to find it — rapid experimentation, therefore, is the cure. Moreover, their advice to move, rather than think, seems to accelerate as the complexity of the strategic landscape intensifies. Essentially, the philosophy seems to be: “If you don’t know where you’re going, any path will do.”

I can see that this kind of advice resonates with executives. Most see themselves as “doers” rather than thinkers. But additional thinking is needed more than additional doing. The more complex and varied a terrain, the more valuable a map. In a simple competitive landscape, everyone can see the strategic solution and success is about winning the race to the top. On a complex terrain, however, those with a guiding theory will be more likely to identify new positions of competitive advantage.

The bottom line? The difference between strategic successes and failures has far more to do with the quality of the theory that’s behind a company’s strategic experiments than with the pace of the experimentation. Sustaining value creation, by extension, requires better corporate theories — not faster-paced pivots.

How to Help Someone Develop Emotional Intelligence

If you are one of the unlucky people who must deal with a clueless colleague or a brutish boss, you’re not alone. Sadly, far too many people at work lack basic emotional intelligence. They simply don’t seem to have the self-awareness and the social skills that are necessary to work in our complicated multicultural and fast-moving companies. These people make life hell for the rest of us.

What can you do to turn these folks around and make work a healthier, happier, more productive place to be? Whose job is it, anyway, to fix these people?

If one of these socially awkward or downright nasty people works directly for you, it is indeed your job to do something. They ruin work teams and destroy productivity, not to mention morale. They’re little time bombs that go off when you least expect it — sucking up your time and draining everyone’s energy. They need to change, or they need to leave.

Here’s the problem: EI is difficult to develop because it is linked to psychological development and neurological pathways created over an entire lifetime. It takes a lot of effort to change long-standing habits of human interaction — not to mention foundational competencies like self-awareness and emotional self-control. People need to be invested in changing their behavior and developing their EI, or it just doesn’t happen. What this means in practice is that you don’t have even a remote chance of changing someone’s EI unless they want to change.

Most of us assume that people will change their behavior when told to do so by a person with authority (you, the manager). For complicated change and development, however, it is clear as day that people don’t sustain change when promised incentives like good assignments or a better office. And when threatened or punished, they get downright ornery and behave really badly. Carrot and stick performance management processes and the behaviorist approach upon which they are based are deeply flawed, and yet most of us start (and end) there, even in the most innovative organizations.

What does work is a) helping people find a deep and very personal vision of their own future and b) then helping them see how their current ways of operating might need a bit of work if that future is to be realized. These are the first two steps in Richard Boyatzis’ Intentional Change theory — which we’ve been testing with leaders for years. According to Boyatzis — and backed up by our work with leaders — here’s how people really can begin and sustain change on complex abilities linked to emotional intelligence:

You and Your Team

Emotional Intelligence

Feelings matter at work

First, find the dream. If you’re coaching an employee, you must first help him or her discover what’s important in life. Only then can you move on to aspects of work that are important to this person. Then, help your employee craft a clear and compelling vision of a future that includes powerful and positive relationships with family, friends, and coworkers. Notice that I’m talking about coaching your employee, not managing him. There’s a big difference.

Next, find out what’s really going on: What’s the current state of this person’s emotional intelligence? Once a person has a powerful dream to draw strength from, he’s strong enough to take the heat — to find out the truth. If you are now truly coaching him, you’re trusted and he’ll listen to you. Still, that’s probably not enough. You will want to find a way to gather input from others, either through a 360-degree feedback instrument like the ESCI (Emotional and Social Competency Inventory), or a Leadership Self Study process (as described in our book, Becoming a Resonant Leader), which gives you the chance to talk directly to trusted friends about their EI and other skills.

Once you have the dream and the reality, it’s time for a gap analysis and a learning plan. Note that I did not say “performance management plan,” or even “development plan.” A learning plan is different in that it charts a direct path from the personal vision to what must be learned over time to get there — to actual skill development.

Learning goals are big. Take, for example, one executive I know. Talented though he was, he was in danger of being fired for his distinct lack of caring about the people around him. He wanted what he wanted, and watch out if you were in his way. He couldn’t seem to change until it finally dawned on him that his bulldozer style was playing out at home too, with his children. That didn’t fit at all with his dream of a happy, close-knit family, living close to one another throughout their lives. So, with a dream in hand and the ugly reality rearing its head at work and at home, he decided to work on developing empathy. As a learning goal, empathy is one of the toughest and most important competencies to develop. The capacity for emotional and cognitive empathy is laid down early in life, and then reinforced over many years. This gentleman had a good foundation for empathy in childhood, but intense schooling and a stint at an up-or-out management consulting firm drove it out of him. He needed to relearn how to read people and care about them. He was able to succeed. Yes, it took a good while, but he did it.

This sounds like a lot of hard work for your employee, and it can be. Here’s where a final important piece of the theory comes into play. They — and you — can’t do it alone. People need people — kind and supportive people — when embarking on a journey of self-development. Are you there for your employees? Do you help thme find other supporters, in addition to yourself, who will help when their confidence wanes or when they experience inevitable setbacks?

Developing one’s emotional intelligence can make the difference between success and failure in life and in work. And, if you’re the one responsible for people’s contributions to the team and your organization, you are actually on the hook to try to help those (many) people who are EI-challenged, deficient, and dangerous. It’s your job.

But what if you’re not the boss? You can still make a difference with colleagues, too. All of the same rules apply to how people change. You just need to find a different entry point. In my experience, that entry begins with you creating a safe space and establishing trust. Find something to like about these people and let them know it. Give them credit where credit is due, and then some (most of these folks are pretty insecure). Be kind. In other words, use your EI to help them get ready to work on theirs.

And finally, if none of this works, these “problem people” don’t belong on your team — or maybe even in your organization. If you’re a manager, that’s when it’s time to help them move on with dignity.

April 23, 2015

Do CEOs Really Have the Power to Raise Wages?

Here’s how one introductory economics textbook begins its discussion of how much workers get paid:

“We explain how a wage rate is determined in much the same way we’d explain how the price of soybeans is determined. We do this for one simple reason: It works.”

Except it doesn’t always work. Supply and demand can’t explain why Dan Price, the founder of a small credit card processing firm, would raise the minimum salary at his company to $70,000. Price is “cutting his own salary from nearly $1 million to $70,000 and using 75 to 80 percent of the company’s anticipated $2.2 million in profit this year” to pay his employees. It’s hard to imagine the same thing happening in the market for soybeans.

Price’s story is extreme, but his divergence from textbook economics is more than a theoretical curiosity. American companies are flush with cash, while wages remain stagnant. Plenty of policy changes have been proposed to address this imbalance, but what, if anything, can companies do on their own to put a dent in income inequality? Specifically, what would happen if more CEOs took a page, or even a paragraph, from Price’s book and raised their employees’ salaries? The conventional wisdom here is shifting quickly, with implications for how companies should compensate their workers.

When McDonalds’ CEO announced last month that he was raising 90,000 employees’ wages, he claimed he was “taking action to make McDonald’s a modern, progressive burger company.” When Walmart announced something similar in February, its CEO positioned the move as a show of solidarity: “After all,” he wrote, “we’re all associates.”

Pundits weren’t buying it. Several suggested that the real reason for the wage hikes was an improving economy. More jobs and fewer unemployed workers should translate into higher wages, just like with soybeans.

Supply and demand often do a decent job of explaining how workers are compensated. To this way of thinking, no single firm sets wages; the price of labor is set in a competitive market. If that’s true, firms can’t raise wages much above market rates without hurting their competitiveness. As my former colleague Justin Fox writes, “By the mid-1990s the idea that companies had to keep wages low to be competitive globally, and that this thing called ‘the market’ simply could not be defied, was pretty widespread.”

But in recent years, a growing chorus of commentators have rejected this reasoning, citing research suggesting that the market for labor isn’t like the markets for everything else. “Wages are not, in fact, like the price of butter,” Paul Krugman wrote in March, “and how much workers are paid depends as much on social forces and political power as it does on simple supply and demand.” Furthermore, he argued, “Paying workers better will lead to reduced turnover, better morale and higher productivity.” For companies, that last bit is particularly worth paying attention to.

In 1914, Henry Ford famously announced that his company was doubling wages for most of its male factory workers, raising them to $5 a day. He didn’t need to attract more workers — candidates would line up around the block to apply — and by all accounts he already paid competitive wages. He did have a problem with absenteeism.

Larry Summers and Daniel Raff of Harvard examined Ford’s decision in a 1987 paper, and found that the move reduced turnover, boosted productivity and profits, and attracted even more candidates to apply. They present Ford’s experiment as a case study in the benefits of what economists call “efficiency wages” — paying workers more than a company might be able to get away with.

The theory of efficiency wages has made a comeback in recent years. It suggests that firms sometimes have an incentive to pay workers more than the going rate because doing so attracts better candidates, motivates them to work harder, and encourages them to stay at the company longer. Since shirking and turnover are costly, higher wages make financial sense, at least up to a point.

But the story of efficiency wages doesn’t start and stop with traditional economic incentives. The justification for higher wages also hinges on psychology and the “social forces” that Krugman alludes to. For instance, workers have strong views about how much profit is fair for their company to make, and when they’re paid less than they think is fair they don’t work as hard. These views aren’t set by supply and demand, but depend on social context. That’s why lower paid workers tend to make significantly more in industries where other positions are well paid. Administrative assistants who work alongside highly compensated engineers make more than their counterparts in other fields, because the norm of fairness partially trumps market forces.

“Social custom” also shapes what managers think is fair, according to Jonathan Schlefer, a researcher at Harvard Business School who has written extensively about the shortcomings of modern economics. “If you actually look what CEOs were saying in the ‘50s and ‘60s they were saying that good wages are an important part of the American way of doing things,” says Schlefer. “Things that you couldn’t imagine the U.S. Chamber of Commerce saying today. It’s not as if businesses in the 50s and 60s didn’t care about making money because they clearly did. They just saw it in different terms.”

Not everyone agrees that paying workers more will benefit firms, and even advocates of efficiency wages note that there are limits. “I think that we have a chunk of evidence that efficiency wages can work as one (possibly underutilized) approach,” says Jan Zilinsky, a research analyst at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, which recently published a white paper explaining the benefits of higher wages. “But it is not a universal theory that necessarily applies to every worker.”

“It depends on the work that they’re doing,” says Barry Hirsch, a labor economist at Georgia State University. “If it’s the type of workforce where you can’t measure what they do very well, and it involves a lot of goodwill on their part, then taking a high-wage strategy might work.”

This point was echoed by Zeynep Ton, a professor at MIT Sloan School of Management and author of The Good Jobs Strategy, who emphasized that high-wage strategies require firms to actively change the way they design work for their employees. “What I found in my research is companies in the retail sector that paid people more also asked them to do different things,” Ton says. “For example, [at the convenience store chain QuickTrip] people don’t just sell merchandise, they also order merchandise. They can contribute more to the company.”

Adam Ozimek, an economist at Moody’s Analytics, is more skeptical. He finds it plausible that workers who are paid above the market rate work harder, but questions why, if that’s true, firms haven’t figured it out by now. “Where’s the hedge fund or private equity firm that has formed on the basis of buying companies and raising wages for increased profit?” he asks. In fact, some of the work on efficiency wages assumes companies are already paying them, which would mean they can’t pay more without facing competitive pressure.

Still, some experts believe there are plausible reasons why companies would fail to recognize the benefits of paying workers more.

Former labor secretary and Berkeley professor Robert Reich points to firms’ obsession with short-term performance. “Companies haven’t figured it out because they’re focused on quarterly earnings, not long-term productivity gains,” he says. (Ton also made this point.) “Furthermore, Wall Street looks at payroll costs, not at productivity gains. Even if they’re a private company, productivity gains are more difficult to measure than costs.” (I interviewed Reich earlier this year about Obamacare, full-time work, and the labor market.)

Managers may also be too risk-averse to recognize the benefits of higher pay. “The manager can easily rationalize staying the course, or simply doing roughly what the competition is doing,” says Zilinsky. “Bold moves, like company-wide raises, are not guaranteed to work precisely as desired. So the risk of having to explain suboptimal outcomes after a policy change is not an appealing prospect.” (Price has been praised, but also widely criticized for his decision.) Zilinsky also notes that some CEOs may fear that such a move would give the impression of “giving in to labor.”

Price told The New York Times that “there is nothing in the market that is making me do it,” meaning he isn’t raising wages just to boost profits. Traditional economic theory would predict that he’ll pay for it, as less generous firms are able to reinvest more of their profits back into their businesses. But there’s no guarantee that that’s right. There really are many ways in which labor and soybeans are different, and in some cases that means that paying workers more will pay for itself through increased productivity.

Much of the psychological research on wages focuses on the idea of a “gift exchange” between employer and employee. When a firm offers the gift of generous wages, employees reciprocate with the gift of harder work. Price, perhaps like Ford before him, is certainly giving his employees a gift. We’ll see what he gets in return.

New Hires Create More Anxiety at a Midsized Company

My company keeps growing. We add clients, revenue, profit, and of course, we need to add people when some of us are too busy to handle the added workload. But I’ve noticed a pattern over the past few hires: the very people who would benefit most from additional help at first resist the idea of a new arrival. Initially, I was surprised by this phenomenon, but I’ve since recognized that it’s not an uncommon response.

Many articles have been written about why employees resist change and how to overcome that fear and defensiveness. Most refer to organizational changes such as restructuring, mergers, acquisitions, downsizing or moving locations, all of which may result in abrupt shifts in reporting lines, job responsibilities, or the physical environment. Having spent my entire (long) career since college working for only three companies, including ten years at the one I co-founded, I am an Exhibit-A creature of habit, who has problems with any change whether it’s moving the position of my PC or adding a security code to our elevator. These small changes pale in comparison with adding a new senior member to the team.

However, as the CEO of a small investment firm, I am in a position to observe when it’s time to hire someone new. I realize that mostly often, it’s the anticipation of the unknown that creates the stress. However, I never expected resistance to the idea of a new hire from the very people who need relief. (We have not added layers above our current team — it’s either someone hired to work under our current managers or a person coming on board to a new role, made necessary because of growth.)

To shed some light on this mystery, I surveyed 60 top-level executives, most of whom had also founded their company, to ask about resistance to hiring. All but one were involved with personnel decisions, the vast majority were currently hiring someone (76%) and 84% of the time it was because of growth in the company’s business or expansion of the skills required.

I was sure my fellow CEOs would share their own experiences with executives who were hesitant about hiring. However, it didn’t quite turn out that way. Only 22% reported that they encountered resistance among their existing team compared to 78% who found none. I was amazed to see those numbers until I looked more closely at one important factor: size of the company.

The majority of CEOs from my survey pool led corporations with over one hundred employees, and experienced very little push back in adding personnel. The same was true with very small companies. However, half of the CEOs of businesses with between 12 and 55 full-time staff responded that they faced resistance.

The CEO respondents believed that the reason was concern about change in job responsibility and the company culture. This was true across a wide range of industry sectors and longevity of the enterprise. Two technology CEOs, Jeff Flowers and David Friend, the co-founders of several companies including Carbonite and Storiant, told me that original members of growing organizations may become anxious about losing influence and power when they hear about new hires, until they feel secure enough in a larger corporate setting.

At a small, brand-new company, everyone realizes that growth is an important part of success. At a large company, there may be one or two who might be nervous about any one hire, but not the management team overall. In the middle are firms such as mine, where each senior partner or executive has carved out an area of her or his expertise and responsibility, and any bad hire could affect the firm culture or cause an uncomfortable shift in job function. (Interestingly, there were very few mentions of compensation as a factor in discontent.)

Leadership consultant Sam Bacharach points out that when any job responsibility status quo is threatened, employees at every level may panic. He and others recommend implementing change slowly, but it’s pretty tough to hire a person in increments.

What you can do is introduce the idea of a new person slowly, letting it sink in with one or two other executives, and listen to their thoughts and concerns – which is what I’ve begun doing. From there, we build a very specific job description, including input from several members of our team who would like to offload some responsibilities. It’s critical that they feel secure that they will retain control over the essential elements of their work.

As I’m considering the type of person we need for our next professional, I am compiling a very specific list of tasks that we would like this individual to perform, with help from those who are stretched to the limit. As CEOs and leaders of enterprises, we need to add new members to our team carefully, paying attention to both the organizational needs and the points of resistance so that we manage our growth with everyone in mind.

A Process for Empathetic Product Design

The discipline of product management is shifting from an external focus on the market, or an internal focus on technology, to an empathetic focus on people. While it’s not too difficult to rally people around this general idea, it can be hard at first to understand how to translate it into tactics. So in this article, I’ll walk through how we applied this approach to a particular product at a start-up, and how it led to large-scale adoption and, ultimately, the acquisition of the company.

I was previously VP of Design at MyEdu, where we focused on helping college students succeed in college, show their academic accomplishments, and gain employment. MyEdu started with a series of free academic planning tools, including a schedule planner. As we formalized a business model focused on college recruiting, we conducted behavioral, empathetic research with college students and recruiters. This type of qualitative research focuses on what people do, rather than what they say. We spent hours with students in their dorm rooms, watching them do their homework, watch TV, and register for classes. We watched them being college students, and our goal was not to identify workflow conflicts or utilitarian problems to solve; it was to build a set of intuitive feelings about what it means to be a college student. We conducted the same form of research with recruiters, watching them speak to candidates and work through their hiring process.

This form of research is misleadingly simple – you go and watch people. The challenge is in forging a disarming relationship with people in a very, very short period of time. Our goal is to form a master/apprentice relationship: we enter these research activities as a humble apprentice, expecting to learn from a master. It may sound a little funny, but college students are masters of being in academia, with all of the successes and failures this experience brings them.

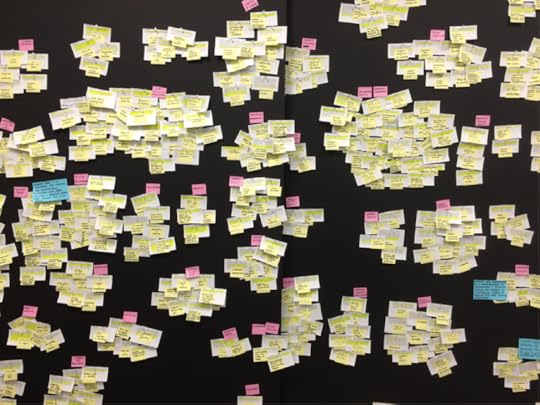

As we complete our research, we transcribe the session in full. This time-consuming effort is critical, because it embeds the participants’ collective voice in our heads. As we play, type, pause and rewind our recordings, we begin to quite literally think from the perspective of the participant. I’ve found that I can repeat participant quotes and “channel” their voice years after a research session is over. We distribute the transcriptions into thousands of individual utterances, and then we post the utterances all over our war room.

The input of our behavioral research is a profile of the type of people we want to empathize with. The output of our research is a massive data set of verbatim utterances, exploded into individual, moveable parts.

Once we’ve generated a large quantity of data, our next step is to synthesize the contents into meaningful insights. This is an arduous, seemingly endless process – it will quite literally fill any amount of time you allot to it. We read individual notes, highlight salient points, and move the notes around. We build groups of notes in a bottom-up fashion, identifying similarities and anomalies. We invite the entire product team to participate; if they have 15 or 30 minutes, they are encouraged to pop in, read some notes, and shift them to places that make sense. Over time, the room begins to take shape. As groupings emerge, we give them action-oriented names. Rather than using pithy labels like “Career Service” or “Employment”, we write initial summary statements like “Students write resumes in order to find jobs.”

When we’ve made substantial progress, we begin to provoke introspection on the categories by asking Why-oriented questions. And the key to the whole process is that we answer these questions, even though we don’t know the answer for sure. We combine what we know about students with what we know about ourselves. We build on our own life experiences, and as we leverage our student-focused empathetic lens, we make inferential leaps. In this way, we drive innovation, and simultaneously introduce risk. In this case, we asked the question, “Why do students develop resumes to find jobs?” and answered it, “Because they think employers want to see a resume.” This is what Roger Martin refers to as “abductive reasoning” – a form of logical re-combination to move past the expected and into the provocative world of innovation.

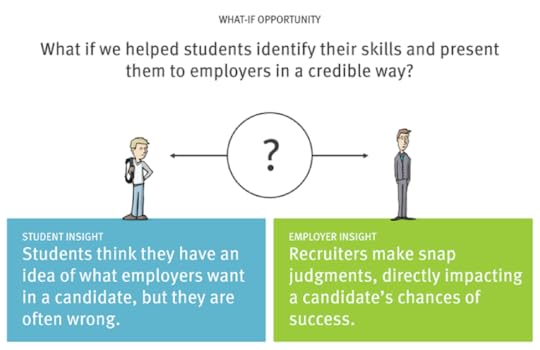

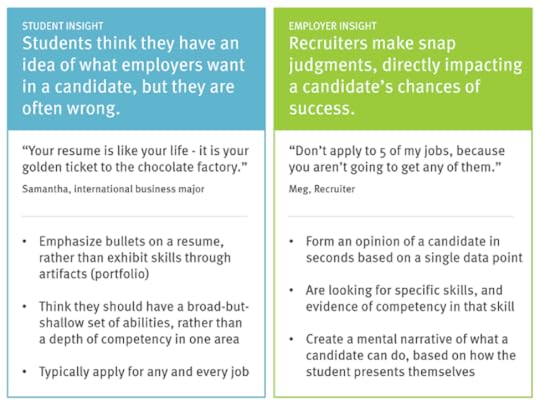

Finally, when we’ve answered these “Why” questions about each group, we create a series of insight statements. Insights are provocative statements of truth about human behavior. We’ll build upon the why statement, abstracting our answer away from the students we spent time with, and making a generalization about all students. We asked “Why do students develop resumes to find jobs?” and we answered it, “Because they think employers want to see a resume.” Now, we’ll craft an insight statement, “Students think they have an idea of what employers want in a candidate, but they are often wrong.” We’ve shifted from a passive statement to an active assertion. We’ve made a large inferential leap. And we’ve arrived at the scaffold for a new product, service, or idea.

We can create a similar provocative statement of truth about recruiters. Based on our research, we identified that recruiters spend very little time with each resume, but have very strong opinions of candidates. Our insight statement becomes “Recruiters make snap judgments, directly impacting a candidate’s chances of success.”

The input of our synthesis process is the raw data from research, transcribed and distributed on a large wall. The output of our synthesis process is a series of insights – provocative statements of truth about human behavior.

Now, we can start to merge and compare insights in order to arrive at a value proposition. As we connect the two insights above and juxtapose them, we narrow-in on a what-if opportunity. What if we taught students new ways to think about finding a job? What if we showed students alternative paths to jobs? What if we helped students identify their skills and present them to employers in a credible way?

If we subtly shift the language, we arrive at a capability value proposition. MyEdu helps students identify their skills and present them to employers in a credible way.

This value proposition is a promise. We promise to students that, if they use our products, we’ll help them identify their skills and show these skills to employers. If we fail to deliver on that promise, students have a poor experience with our products – and leave. The same is true for any product or service company. When Comcast promises to deliver internet access to our home, but doesn’t, we get frustrated. If they fail frequently enough, we dump them for a company with a similar, or better, value proposition.

Insights act as the input to this phase in the empathetic design process, and the output of this process is an emotionally charged value promise.

Armed with a value proposition, we have constraints around what we’re building. In addition to an external statement of value, this statement also indicates how we can determine if the capabilities, features, and other details we brainstorm are appropriate to include in the offering. If we dream up a new feature and it doesn’t help students identify their skills and present them to employers in a credible way, it’s not appropriate for us to build. The value promise becomes objective criteria in a subjective context, acting as a sieve through which we can pour our good ideas.

Now, we tell stories – what we call “hero flows,” or the main paths through our products that help people to become happy or content. These stories paint a picture of how a person uses our product to receive the value promise. We write these, draw them as stick figures, and start to actually sketch the real product interfaces. And then, through a fairly standard product development process, we bring these stories to life with wireframes, visual comps, motion studies, and other traditional digital product assets.

Through this process, we developed the MyEdu Profile: a highly visual profile that helps students highlight academic accomplishments and present them to employers in the context of recruiting.

During research, we heard from some college students that “LinkedIn makes me feel dumb.” They don’t have a lot of professional experiences, so asking them to highlight these accomplishments is a non-starter. But as students use our free academic planning tools, their behavior and activities translate to profile elements that highlight their academic accomplishments: we can deliver on our value proposition.

Our value proposition acts as the input to the core of product development. The output of this process is our products – facilitating the iterative, incremental set of capabilities that shift behavior and help people achieve their wants, needs, and desires.

The case above illustrates what we call ”empathetic research.” We marinated in data and persevered through a rigorous process of sensemaking in order to arrive at insights. We leveraged these insights to provoke a value proposition, and then we built stories on top of the entire scaffold. And as a result of this process, we created a product with emotional resonance. The profile product attracted over a million college students in about a year, and during a busy academic registration period, we saw growth of 3000-3500 new student profiles a day. After we were acquired by Blackboard and integrated this into the flagship LMS, we saw growth of 18,000-20,000 new student profiles a day.

The process described here is not hard, and it’s not new – companies like frog design have been leveraging this form of approach for years, and I learned the fundamentals of empathetic design when I was an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon. But for most companies, this process requires leaning on a different corporate ideology. It’s a process informed by deep qualitative data rather than statistical market data. It celebrates people rather than technology. And it requires identifying and believing in behavioral insights, which are subjective and, in their ambiguity, full of risk.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers