Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1302

April 8, 2015

The Subtle Ways Our Screens Are Pushing Us Apart

I once asked a former U.S. Navy admiral in charge of a fleet of aircraft carriers how he felt about collaborating with people through email, computers, smart phones, etc. In response, he told me the following story:

“I would never send a rookie pilot to land a fighter jet on a carrier deck in the middle of the night, in the middle of the ocean on a new moon. It’s pitch black. You can’t see your hand in front of your face. The pilot has all of his instruments at the ready. He always knows his exact altitude, speed, and distance from the ship. But he doesn’t have the one crucial thing he needs to land safely. He doesn’t have any depth perception. And that’s how I feel when I “talk” to people online — I have no depth perception.”

Like the fighter pilot armed with all the technology he would seemingly need to land safely onto the carrier, today’s workforce has more than enough tools to send information back and forth to people all over the world. But those tools — and the use of them — do not necessarily constitute collaboration.

Collaboration implies more than just passing data back and forth in an attempt to develop what is often a non-descript deliverable that can be as forgettable as the interactions themselves. Genuine collaboration is achieved through ongoing meaningful exchanges between people who share a passion and respect for one another. Trading ideas and taking risks on behalf of others and the organization is key. Ultimately, new innovations and critical problem solving are realized through relationships.

However, today’s keyboard-tapping workers have very little context around who their counterparts are, how they feel about things, or what they hope for — in other words, what motivates them. Without a panoramic perspective, it’s difficult to form a sense of common purpose. In fact, when a seemingly intelligent screen is the only frame in sight, people often default to decoding messages based on what they know, filling the contextual void using their own experience to color in the blank backgrounds behind their co-workers. But this can create distorted perceptions about other people’s values and beliefs, causing collaboration conundrums.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

Today’s global workforce is often blind to the bigger picture, other than being able to identify themselves as a dot in a social network map or a box on a bulky org chart. This lack of shared context — between team members and with the business itself — is at the heart of a rapidly growing phenomenon called “virtual distance.”

Virtual distance is a sense of psychological and emotional detachment that begins to grow little by little and unconsciously when most encounters and experiences are mediated by screens on smart devices. It’s often assumed that the usual suspects are to blame: physical separation or time zone gaps. But they’re not. Physical distance can certainly add to virtual distance; however, the main issues come through more subtle circumstances.

The virtual distance model is made up of three factors: physical distance, operational distance, and affinity distance. Physical distance is essentially geographic distance. Operational distance builds when there’s a lack of shared context that can produce unwanted noise in the system – such as miscommunications that can irritate people, or technical problems, like your Skype connection failing, or a conference call with a bad connection. Affinity distance comes from a set of ever-flowing undercurrents that can stop deep relationships from taking root. For example, you may not understand what your colleague values in his or her work, and vice versa. Or, you and others may not recognize that you share the same future or fate. This can result in the unintended consequence of avoiding the effort to build richer, longer-lasting relationships, because in the absence of meaningful mutuality, the motivation to do so may never manifest.

My colleagues and I have measured high levels of virtual distance around the world. The data clearly demonstrate that uncontrolled virtual distance can result in unintended and unwanted effects. For example when virtual distance is relatively high:

Innovative behaviors fall by over 90%

Trust declines by over 80%

Cooperative and helping behaviors go down by over 80%

Role and goal clarity decline by 75%

Project success drops by over 50%

Organizational commitment and satisfaction decline by more than 50%

Virtual distance generates a shift in how people feel about themselves, other people, and the way in which they see themselves as part of, or separate from, the larger organizational landscape. In the absence of shared context, the connectivity paradox emerges: the more people are connected, the more isolated they can feel. And isolates among isolates do not collaborate, instead they simply comply with management edicts. But compliance is not the same as collaboration. So, like pilots circling around in the dark, much of today’s workforce is lost in transmission because they don’t want to risk crashing on the carrier deck.

But this doesn’t have to be the case.

To restore true collaboration, leaders must continuously restore shared context. A simple example would be to make sure that all team members know what the local time is for each participant on a call. If it’s late for one member, the leader can acknowledge that whatever to-do list results from the call, they can start it in the morning. Believe it or not, this small thing — bringing the time of day into context and acting accordingly — can help a team member feel respected. It also shows other team members that the manager is compassionate, which makes everyone feel more at ease. Revealing shared context and making appropriate adjustments can have a profound impact on performance.

When leaders learn to lift the veil of virtual distance, people are able to see in others what matters most — what inspires them to act on behalf of others — their mutually shared humanity.

In one organization whose mission was to work on behalf of children’s health, we measured virtual distance and found it to be high on affinity distance – that is, people weren’t forming very good relationships. It’s an interesting case, because all of the employees were in one building, but spread across two floors. Most leadership might assume that because people were “co-located”, there would be no issues with virtual distance. However, it happens with people who sit right next to each other as much as it does between far-flung employees. Once the virtual distance was revealed, the C-level executives took action, putting strategies in place to increase social connections by regularly showcasing team member contributions. For example, senior management publicly recognized one individual’s work that had resulted in helping one of the member hospitals to save a child’s life, tying his efforts directly back to the company’s mission. Recognition came in the form of an email announcement, a newsletter post, and the manager verbally congratulating the team member during a regularly scheduled call. Had it not been for the virtual distance training the manager had enacted, that employee would never have gotten any of the kudos he deserved.

In another example, a virtual distance analysis conducted at a large financial services institution also revealed a high level of affinity distance. This particular problem was traced back to a $3 million dollar loss caused by a significant project delay. To ensure the situation would not happen again, executive management put a process in place to assure that when project teams were formed, they pulled from a diverse group of people, who had never worked together before but were acquainted. These “weak ties” facilitated faster trust formation. This approach also helps employees build wider social networks throughout the organization by reducing virtual distance between individuals and with the business itself from the outset. Projects that used this and other virtual distance heuristics were much more successful than projects that paid little attention to virtual distance dynamics.

Over time, by implementing these and other virtual distance management strategies, this organization reaped significant benefit by reducing virtual distance and increasing financial performance, which led to a rise in stock price and shareholder value.

For leaders, the very first step in reducing virtual distance is to become aware that it’s strongly embedded everywhere screen-based interactions occur — between people sitting side-by-side with thumbs thumping while meeting for lunch or amongst team members scattered across the globe with only a glowing screen to keep them company. To address it, leaders need to develop techno-dexterity, which is the ability to act deliberately when communicating, understanding which message to deliver when and through which channel (face-to-face, phone, email, video, etc.). For example, you would never fire someone by video chat, though it may sometimes be appropriate to meet a new client that way. Before you send a message, you should always ask yourself: “What do I want the receiver to do after I convey this message?” If you realize you just need a simple reply, then email may be best. If, on the other hand, you want a more detailed explanation, it’s probably better (and faster) to get that via phone. By thinking about the who, what, when, where, and how of messaging and by including how much context the other person might need to fully understand your message, you will reduce virtual distance and improve performance.

To establish closer confidences that fuel genuine collaboration, leaders need to reduce virtual distance and stimulate a shared sense that everyone is in the same boat — or at the very least — that there even is a boat.

Good Leaders Aren’t Afraid to Be Nice

It only took me about three seconds to decide what to wear on the first day in my new gig as strategy director at Genuine Interactive, a digital marketing agency (jeans and a wrinkled linen shirt, duh). Deciding what books to take was a bit trickier.

In the end, I decided to bring only one: The Power of Nice: How to Conquer the Business World with Kindness by Linda Kaplan Thaler and Robin Koval. Sure, the niceness principles in Chapter 1 are great, but what’s most intriguing about the book — especially for a strategy leader — is Chapter 8: Shut Up and Listen.

As strategists (and colleagues, and partners, and friends, and family members) we are often so eager to share what we think are dazzling insights that we cut things short and miss what’s important about a given interaction or relationship.

In a world filled with agencies, most of which offer the same services at roughly the same prices, the ultimate difference between success and failure is whether people want to work with your teams or not. It’s the same on the inside. Tara Back, my former boss and the new head of the event and experience lab at Google, used to say that success in an agency is when everyone wants you as part of their team.

In giving advice to customer experience professionals choosing an agency, Forrester Research advises: “Always consider how well the agency will be able to deliver a painful but necessary piece of advice or how comfortable it will be to work with the agency when something doesn’t go quite to plan.” And that’s where nice comes in. Everyone’s nice when things are going their way, but how nice are you when you find yourself in a tough situation?

In my experience, tough and nice don’t have to be incompatible. The most successful strategists are tough and intensely curious: tabloid reporters without the mean streak. The five goals listed in Chapter 8 are guides worth keeping in mind as my new team and I set strategy and I lead a new team:

Let the other guy (gal) be smarter. The person who desperately tries to be the smartest person in the room inevitably comes off as the least. During one pitch in which I was involved, the client told a strategist he reminded him of Cliff Clavin, the know-it-all postman from the TV show Cheers. (We didn’t win.) I know this is a tough balance — especially for young people starting out who want to show their smarts. But that’s where a little guidance from good mentors comes in.

Keep it simple. Life is complicated enough. Clients and colleagues expect us to be expert enough to keep things simple and easy to follow. It’s a constant struggle to focus more on the story you’re trying to tell than on the slides. But by reminding myself and my team that we’re sitting down with a client to have a nice conversation, we might be able to avoid coming across as the type of people who overly complicate things or act in a way that’s self-important.

Ask don’t tell. Even if you think you know the answer already, it’s worthwhile to ask someone to articulate it for you. You may be pleasantly surprised by what you hear. In my experience, this has the added benefit of conveying respect for work that has already been done and for the people who have done it.

Don’t argue so much. Really. Don’t. Everyone has a style and way of going about understanding and contributing to a project. But in my experience, if you slip from being challenging to being argumentative, your chances of getting chosen for a project or a team go down dramatically.

Everyone is worth a listen. Don’t confuse this with the idea that everyone deserves a medal; some ideas are better than others (enough said). But pretty much all are worth a bit of a listen before moving on.

I have plenty of company in my views: Everyone from Richard Branson to Barrie Bergman has claimed that being nice is in no way incompatible with being successful in business. Need proof? For this, you can turn to another new book, Return on Character: The Real Reason Leaders and Their Companies Win, that just came out and is featured in this month’s Harvard Business Review. It’s based on a seven-year study of 84 CEOS and 8,000 of their employees. Basically, leaders who display integrity, compassion, the ability to forgive and forget, and accountability — who are what most of us would consider nice — deliver five times the return on assets of their counterparts who never or rarely display those traits.

So as I tackle my new job, I’ll be keeping these two things in mind: you can build character if you make it a priority, and nice guys do finish first.

8 Reasons Companies Don’t Capture More Value

In general, companies don’t devote enough time to thinking about value capture. Their innovation efforts tend to be focused wholly on the creation of new value; meanwhile, the question of how exactly they will be compensated for it usually goes unexamined. Why is it that? One typical reason is that top executives haven’t managed to clarify something even more fundamental: how much priority they place on increasing profit margins.

That might sound strange. Doesn’t every business want to maximize its profits? Pricing textbooks certainly all assume they do, or at least that they want to achieve a certain profit level under given constraints. But in truth businesses rarely focus on only profitability; most strive to satisfy various stakeholders and meet the goals of balanced scorecards. And even when a company is focused tightly on financial performance, there are at least eight reasons it might have for deliberately accepting something less than the full value it could capture from an offering. They are listed below, each with an example:

Profit maximization (long-term): A bank offers accounts to students at a special interest rate to attract a segment of customers whose incomes will later increase.

Profit maximization (short-term): A shipping company increases freight rates by 50% to benefit from a capacity shortage in the market, even though doing so will strike customers as exploitative and damage loyalty.

Growth: A TV cable company offers special subscription plans for new customers, aiming to achieve a strong market position within 24 months.

Market share: An international beer company strives for at least 10% of market share in any national market, treating that as a strategic threshold level.

Market stability: A steel distributor does not follow a price reduction by a competitor, assuming that it will be temporary and that customers hate readjusting their inventory valuations frequently.

Price leadership: A no-frills airline constantly advertises the lowest fares on any route served.

Deterring new providers: A professional event technology firm offers rock-bottom quotes to special events to signal its pricing power to any potential new entrants.

Positioning: A watch company prices different brands along a predefined, brand-led price corridor.

The challenge for executives is, of course, to manage their conflicting goals, or so-called trade-offs. The most prevalent tension to resolve is between market share (or sales revenue) and margin. If the product manager in a consumer packaged goods company is focused on gaining market share within her category (perhaps because her bonus is predicated on that), a low-price attack by a competitor is likely to trigger a price decrease for her own product, even if the profit suffers more from the price decrease than from the market-share loss. Similarly, if the salesforce of an industrial equipment producer is offered incentives to hit revenue targets (“You get $10,000 extra bonus if sales exceed $5 million”), it is quite likely that salespeople will try to sell the products at any price.

Another typical trade-off is between resource allocation and profit. A manufacturer, for example, might maintain production levels to keep the workers and the machines busy, even knowing that the products are likely to be sold at a loss and the price dynamics could cause a price war.

With such trade-offs to manage constantly, it can be hard for companies to make unambiguous decisions about priorities. But the confusion runs deeper than that. In the real world, the decision-makers are not companies but rather people within those companies. Individual objectives often are not aligned. For example, the sales manager is interested in top-line revenues, whereas the factory manager is interested in capacity utilization and predictable ordering patterns.

All this makes it clear why it can be so hard to devise and stick to strategies for pricing – let alone to pursue the many options for capturing more value that go above and beyond mere pricing decisions. Indeed, it is sometimes shocking to see how much money and resources company spend on better pricing data, research, and tools, and how little is achieved, simply because executives are not aligned in their priorities.

In my experience of working with companies in various industries around the globe, two types of misalignment are most common. The first type occurs when different stakeholders make decisions that favor their preferences at the expense of other objectives, and everyone is aware of it. The more dangerous situation, which I call Type Two misalignment, happens when the different stakeholders are not even fully aware of conflicting goals and objectives.

The advice to address both types is to take on the task as a management team to set and broadly communicate the strategic priorities that should inform decision-making and innovation in value capture. Again, profit maximization is rarely the sole objective for a firm but just one of many dimensions to be considered, so a good starting point is to consider the company’s balanced scorecard and draw its strategy map.

Then, as the focus shifts specifically to value capture, everyone should be reminded of some basic truths. First: Market share is a dangerous key performance indicator (KPI). It is a backward-looking measure and likely to lead to price wars as soon as one competitor challenges the status quo with a low-price strategy. Second: Revenues and sales metrics should never be used in isolation to determine rewards or decisions of any kind, but only in conjunction with the contribution margin and profit figures. Practitioners sometimes justify their top-line focus by arguing that revenue is much easier to measure than profit (which is sometimes even confidential). In such a situation, the company has to define proxy variables that prevent fighting for nonprofitable deals. Third: When value capture objectives are not aligned within a company, the result is inconsistent behavior and frustration. Conversely, a shared sense of what must be achieved creates the climate for productive cross-functional collaboration.

There are all kinds of reasons, of course, for management teams to try to achieve more strategic clarity. But one of them is the fact that poor alignment on priorities is a serious obstacle to capturing value. Most companies have developed quite sophisticated processes and heuristics to balance competing objectives when it comes to creating value for customers. However, they are not as strategic in their thinking about how to capture value. As a rule of thumb, it might sound unhelpful, but yet it is true: Managers should always try to maximize profits, except when they should not. The occasions when they should not are when other strategic priorities must be considered, and are explicitly taken into account.

Building Relationships in Cultures That Don’t Do Small Talk

Michael has been in Frankfurt for about a week and is really missing his home office in Chicago. Everyone in Germany seems to be so serious at work. No small talk, no conversation about the weekend, no interest in his American background — in fact, no interest really in him at all, it seems.

At first, Michael blamed the “uncaring” Germans. But he then started to wonder whether he was, in fact, the problem. Perhaps if he were friendlier or tried even harder, he could make some quick friendships to ease his transition. Determined to make this happen, Michael started to make small talk anywhere and everywhere he could. But these efforts seemed to fall on deaf ears, and worse, alienate his colleagues, who appeared more distant than ever before. As he considered next steps, Michael wondered: What could have gone wrong?

As it turns out, Michael was the problem, but not in the way he thought. What he didn’t realize is that small talk simply isn’t as common in Germany where personal relationships at work take much longer to develop than in the U.S. As a result, Michael’s aggressive attempts at forcing chit-chat with colleagues didn’t go over too well. And it’s not just in Germany where small talk can backfire. In many places around the world, it is unbecoming to engage in trivial banter about the weather or the commute to the office, or to glide from one topic to the other in a lighthearted fashion. In China, for example, people can be quite guarded and protective with personal information among people they do not know well — especially people they perceive to be in competition with for limited resources. The logic is that if people reveal personal information, it could be used against them in some way and lead to a strategic disadvantage.

But what then can you do if, like Michael, you come from a small-talk culture and want to forge relationships with your colleagues, clients, and customers? One essential piece of advice is to take a longer-term perspective on developing relationships. If you assume that relationships and rapport can indeed be developed in a matter of moments, you’ll inevitably be disappointed.

In many cultures it can take quite a long time to establish a relationship, and if you haven’t readjusted your own expectations, you’ll likely misinterpret a lack of closeness as indications someone doesn’t like you, as opposed to the natural progression of a working relationship. In Germany, for example, it can take months or even years time to develop a relationship with your colleagues — but once that friendship has been developed, it is often a deep, personal, and long-lasting one. With this in mind, you can imagine how awkward and unnatural it probably felt for Michael’s German colleagues to be assaulted with questions about the weather, their families, or even to be asked “How it’s going?” when they didn’t know Michael yet. Adjusting expectations is essential when learning to establish bonds in a culture where small talk is not the norm.

But even if small talk isn’t in your arsenal, you can still lay the groundwork for a long-term relationship through other means. One way is to make sure your colleagues see you as someone worthy of having a relationship with, even if it’s not going to happen immediately. Make meaningful gestures that demonstrate sincere interest in the culture and building a relationship. For example, in a group-oriented culture like Korea, where being part of the group is key, even a small gesture like bringing the team a snack from the vending machine — when you initially went there for yourself — can go a long way toward creating a positive impression of yourself. By respecting the values of the local setting, you lay the groundwork for a future relationship when the time is right.

Also, even if chatty, American-style small talk doesn’t work, chances are that there are some topics that are acceptable, and certain occasions exist to discuss these topics. For example, sports is a topic that often translates across cultures and can be a great way to bond with people who share similar interests. Showing interest in local foods, languages, festivals, or sights is also a nice way to indicate appreciation for the other culture and spark a connection. Of course, you should find something you’re genuinely interested in to speak about; if it’s clear you’re talking about sports but know nothing about it, or mention cooking and have never picked up a pot or pan, the conversation probably won’t go very far, and it certainly won’t set the groundwork for a future connection.

Finally, in certain cultures, the key is to recognize when it’s acceptable to build personal connections, because that might vary significantly across the day. For example, in Japan and China, it’s quite common to go out after work late at night and have drinks or dinner. On these occasions it’s much more common to make small talk and discuss nonwork-related topics — even with your boss, who you’d never discuss topics like these with during daytime hours. Noticing and taking advantage of special occasions for relationship building is another critical tool in your arsenal.

In the end, small talk may not be universal, but relationships are. Smart managers realize this and adjust their behavior and expectations for establishing these relationships whenever doing business abroad.

How to Build Expertise in a New Field

Better pay, more joy in the job, or prerequisite to promotion? Whatever your reasons for deciding to build expertise in a new field, the question is how to get there.

Your goal, of course, is to become a swift and wise decision-maker in this new arena, able to diagnose problems and assess opportunities in multiple contexts. You want what I call “deep smarts” — business-critical, experience-based knowledge. Typically, these smarts take years to develop; they’re hard-earned. But that doesn’t mean that it’s too late for you to move into a different field. The following steps can accelerate your acquisition of such expertise.

Identify the best exemplars. Who is really good at what you want to do? Which experts are held in high regard by their peers and immediate supervisors? Whom do you want to emulate?

Assess the gap between you and them. This requires brutal self-assessment. How much work will this change require, and are you ready to take it on? If you discover the knowledge gap is fairly small, that should give you confidence. If you determine that it’s really large, take a deep breath and consider whether you have the courage and resolve to bridge it.

You and Your Team

Mid-Career Crisis

When you’re feeling stuck.

Study on your own. Especially if the knowledge gap between you and experts in the new arena is large, think about what you can do on your own to begin to close it. Self-study, talking to knowledgeable colleagues and possibly some online courses will help.

Persuade experts to share. Many will be pleased to do so — especially if you’ve done your homework and have some foundational knowledge. But some may resist for a host of possible reasons, ranging from a lack of time to fear that you are after their job. Their reactions depend heavily upon both personality and organizational culture. You can strengthen your case by focusing on how helping you will benefit them. Perhaps you could take over some routine tasks that are tiresome to them, but new to you. If the experts are in your own organization, management may reward any investment they make in developing talent. Emphasize that the time commitment can be minimal; you’ll find small time slots in which to query them.

Learn to pull knowledge. You need to become some combination of a bird of prey and a sponge — eagle eyed for opportunities to learn and avid to absorb. Don’t expect experts just to tell you their most critical know-how in bullet points. That’s impossible (because they know what they know in context, when it’s called upon), insulting (because if it were that easy to impart, their knowledge wouldn’t be worth much), and frustrating for you both (because lectures about how to do something rarely translate into true learning.) Instead, use the two most powerful questions in eliciting knowledge: “Why?” and “Can you give me an example?”

Observe experts in action. Concentrated observation is often more effective than interviews because it shows you how they think and act in real time. Ask to sit in on crucial meetings, accompany them to conferences and customer visits, follow them as they solve problems. This is far from a passive process; you’ll need to constantly ask yourself: Why did he or she do that? What was the effect? Would I have done it differently? Afterwards, insist on a few minutes to debrief—even if it’s just during a walk to the parking lot. Check what you observed against the experts’ intention and see if you can “teach it back” by explaining the steps taken and the reasons for them.

Seek mini-experiences. The next step, as I describe in my book Critical Knowledge Transfer, is to identify opportunities to experience in some limited fashion, the environments, situations or roles that have made the expert so valuable to the organization. Perhaps you can’t go to medical school before becoming an MRI-machine designer like the person you’re shadowing, but you can spend a week in a doctor’s office. Maybe you didn’t start out in your company’s call center, like the super sales manager you’re emulating, but you could certainly work the telephones for a few days. Any “mini-experience” that gives you a taste of the expert’s much deeper understanding of a context that informs their judgment will help you gain insights. If nothing else, you will be equipped to ask better questions and pull knowledge more effectively.

Add visible value as soon as possible. The experts and your new or future bosses will want to see some evidence that all this work is paying off. A log of what you have done and learned shows effort and progress. But if you can actually take over some small parts of an expert’s job that he or she is willing (or eager) to relinquish — even better. Perhaps you can attend a conference or association meeting, teach part of an in-house course, draft a report.

Developing expertise takes time. Estimates usually range from seven years or more. But if you follow the steps suggested above, you will have these smarts — and be able to use them — much sooner.

The Benefits of Unplugging as a Team

When turnaround legend Lou Gerstner took the helm at IBM in 1993, one of his boldest early actions was startlingly simple. As the projector bulb warmed up for the ritualized theater of yet another senior management meeting, Gerstner walked to the front of the room, turned off the machine and said, as politely as he could: “Let’s just talk about your business.”

Two decades later — despite that breath of fresh air and even as the overhead has given way to the touchscreen — senior executives’ best thinking is still being suffocated by gadgets: IT, once an acronym full of the promise of “information technology,” has shifted executive teams’ focus too much onto the “T” and not nearly enough onto the “I.”

A growing body of neuroscience research has begun to reveal the exact ways in which information age technologies cut against the natural grain of the human mind. Our understanding of all kinds of information is shaped by our physical interaction with that information. Move from paper to screen, and your brain loses valuable “topographical” markers for memory and insight.

Although screens have their strengths in presenting information — they are, for example, good at encouraging browsing — they are lousy at helping us absorb, process, and retain information from a focused source. And good old handwriting, though far slower for most of us than typing, better deepens conceptual understanding versus taking notes on a computer — even when the computer user works without any internet or social media distractions.

In short, when you want to improve how well you remember, understand, and make sense of crucial information about your organization, sometimes it’s best to put down the tablet and pick up a pencil.

I have seen this truth revealed again and again in my five years as senior managing director at the Drucker Institute, where I lead the Un/Workshops consulting practice. In one to two days, we take executive teams through a fast-paced, transformational experience that requires them to power down their devices and power up their brains.

We recently worked with apparel industry leaders from design, sourcing, manufacturing, and brand management to prototype a more innovative, responsive, and responsible supply chain. The workshop did not include a single PowerPoint slide or digital simulation.

Instead, we put participants in small groups and equipped them with just some Drucker-based prompts, a box of pens, and a few sheets of paper. People like to say that they “connect” with digital technology but there is no match for the physicality of really energized collaboration — people huddling side-by-side, everyone scribbling notes, all watching their work take shape in real time, without jumping prematurely to the air of finality that comes from a slick digital template.

They accomplished a tremendous amount of design and decision-making in a very short amount of time. Instead of pushing pixels around to make the best show of half-baked ideas, they pushed ideas around to arrive at plans with real promise.

My experience is that, when an executive team works “unplugged” for the first time, there is often a moment when the power of briefly setting aside technology shines through. We once asked a global technology firm’s leadership to try a “stone age” solution as they conferred on how to implement a newly hatched strategy. Heretical as it seemed, the meeting did not begin with a full rehash of their 80-slide strategy deck. Instead, we went straight to small groups and a 20-minute assignment: Working on one piece of paper per group, write down the answers to a few basic questions about the heart of the new strategy (on which they had already been briefed many times).

I watched as one top executive pontificated about the strategy to his tablemates … and then drew a total blank when handed the pen. Due to his seniority, I suspect, his colleagues didn’t call him on the failure. But the nearly blank page didn’t lie to anyone in the room, including him. The discussion that followed — Why are we having so much trouble answering some of these basic questions? — uncovered the essential disconnect between the strategy and the team’s understanding of the customer it was supposed to serve. I’m convinced the usual PowerPoint parade would not have paused to expose that gap.

The great news if you want to try unplugging is that the basic techniques are simple and free. Here’s an Un/Workshop-style exercise you can try on your own time, with your own team, in just a half-hour: Including yourself, get six or more of your colleagues together. Divide yourselves into two or more small groups. Give each group one piece of paper with a single question printed on it: Who is our customer?

Have each group spend 10 minutes writing down its answer. Then spend 15 minutes discussing how the groups’ answers are similar — and different.

There’ll be no need to collect phones at the door; from the very start, people will be too busy debating, iterating, and achieving better understanding to even bother reaching for their devices.

April 7, 2015

What Everyone Needs to Know to Be More Productive

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

Does it seem like you don’t have enough hours in the day to get through everything you need to do? With so many competing demands on our time, we can all benefit from learning to ramp up our own personal productivity. HBR recently ran a series called Getting More Work Done. Below is a summary of the advice and best practices our experts contributed to the series:

First, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach, so start by figuring out your own personal productivity style. Try this assessment to figure out how to align your work strategies with your cognitive style. You may or may not already be doing this subconsciously, but it’s helpful to think through: Are you a planner? An arranger? A visualizer?

Next, get organized. You can’t get work done if your life is in disarray. Start with your immediate environment — your desk. Research shows that a messy workspace can undermine your persistence, making you less efficient, more frustrated and more weary. Then, get your schedule and calendar organized. We all have a slew of business, home, family, and personal issues screaming for our attention — but they’re not all equally important. Consider laying all of your competing priorities out using a kanban board to help you decide which to focus on when. Having a constant visual reminder of your priorities and tasks will help you keep things moving in the right direction — and perhaps more importantly, will help you literally see when something’s getting stuck.

If you work independently or in a remote or virtual environment, it’s even more important to keep yourself on task. Here’s a list of things to buy, download or do to make sure you have the right infrastructure in place to be at your most productive. And if you’re a manager who’s been reluctant to let people work from home because you fear that it will reduce their productivity, consider that research shows that high performers can be even more productive at home than in the office.

Once you’ve got your environment and priorities in order, start thinking about how you’re managing your time. First and foremost, take ownership of your time. Set clear rules and boundaries so you don’t end up taking on too much from others. For example, have your project list on hand when you go to meetings so that if a new project is proposed, you can evaluate its importance in relation to your other commitments and propose a discussion about priorities if there doesn’t seem to be enough time to tackle everything. Or if you manage staff members who tend to turn in work at the last minute with way too many errors, insist on earlier deadlines. That will allow you to send work back to them to make corrections instead of doing them yourself just because you’re on a tight deadline.

You and Your Team

Getting More Work Done

How to be more productive at work.

Next, practice saying this all-important word: “No.” There are plenty of ways to push back without alienating people. Be selective about which meetings and events you attend, which projects and tasks you take on — and even which clients you work with. (While you may be loath to turn away business, recognize that there are times when it just makes good sense to fire a problematic client.)

Make the most of your precious time. Consider that even some of the most prestigious networking events can be a complete waste of time. And there’s a lot that you can accomplish in the 30-minute gaps between meetings (finish that expense report, or outline your next presentation, for example), and during your commute (make hands-free phone calls, or listen to audio books or podcasts related to your work).

Finally, realize that you’re not going to be at your best every hour of the day, so try to schedule your most important work to align with periods of peak energy. Research shows that people are most alert within an hour or so of noon and 6pm. Schedule your least important tasks for when you’re less alert — very early in the morning, around 3pm, and late at night. And make sure you’re getting plenty of sleep — and taking naps when needed — to keep your energy levels up.

Some experts recommend focusing on one thing at a time rather than multitasking, which can leave too many things incomplete — giving you, and others, the feeling that you’re not making any progress at all. Just think about how good it feels to cross something off of your to-do list and move on. To maintain focus, you also need to learn to regulate your emotions. Research shows that meditating for just a few minutes a day, spending just one hour a week in nature, or jotting down a few reflective notes in the evening can have a noticeable impact on your well-being and your attention. Conversely, don’t underestimate the impact of “attention leaks” on your ability to concentrate — every device that beeps, blinks, or thrusts red numbers in your face is designed to capture your attention and create a sense of urgency. But how often are any of these interruptions truly urgent? Almost never. When you’re trying to get stuff done, turn them off. And to really increase the odds of achieving your goals, set them with your spouse or partner. Research shows that it’s easier to cross the finish line when we’re not trying to go it alone.

Even with the best-laid plans, there will be plenty of times when you’re simply lacking the motivation or energy to power through your work. For times like this, you can try to trick yourself into doing the tasks you dread. Set up a compelling rewards system. For example, schedule a lunch date with a friend to motivate yourself to get that report done by noon. Save mindless tasks to complete while watching your favorite TV show at home. Treat yourself to concert tickets or a massage after hitting a major milestone. No matter what you choose, you’ll know the rewards are working when your to-do list no longer includes tasks you’ve been avoiding for weeks.

Don’t berate yourself if you’re having trouble getting or staying motivated. Research shows that the way you speak to yourself matters — and if you do it in the second or third person, it can help even more. Saying something as simple as “You can do it” or “You’ve got this” can help you mentally adopt a fly on the wall perspective on your problems, psyching you up for some surprisingly good results.

As a manager, it’s not enough to keep yourself on task. You also have to keep your team productive. Remember that your employees are as easily distracted as you are – but you’re setting the tone and providing the cues that collectively shape people’s views of what’s important. It’s up to you to create a climate in which everyone can be and do their best.

And while it may seem counterintuitive, consider that to be more productive at work sometimes means stepping away from the office. You can often get more done by focusing less on work, and committing to less. So by all means, take a break, regroup, and come back with renewed energy and focus. You’ll create a virtuous cycle where you’re more productive at work so you’ll also be able to carve out more time for what really matters — your life.

Why No One Uses the Corporate Social Network

Imagine an organization that is completely digitally connected. Colleagues connect seamlessly with each other across silos and across the globe. Management has its finger on the pulse of the company, aware of every crisis-induced quickening. And throughout the organization there is a deep sense of connection to the purpose and mission of the organization, and to each other, breaking down hierarchies in the process.

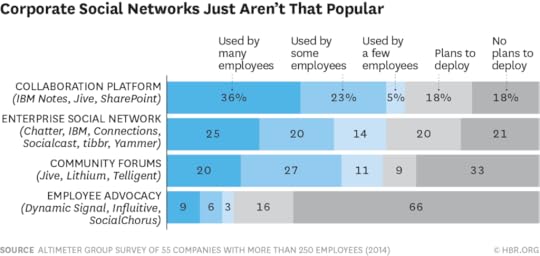

Snap! Leaders – it’s time to wake up from this fairy tale. This is the world spun by people pushing collaboration platforms and enterprise social networks as the panacea to our collaboration woes. The reality is that the landscape is littered with failed technology deployments. Altimeter’s research shows that less than half of the enterprise collaboration tools installed have many employees using them regularly (see figure below).

I recently spoke with the leadership team of a top Silicon Valley technology firm that had installed an internal enterprise collaboration platform for its employee engagement and collaboration efforts. After an initial spike in adoption, usage slowly dwindled. It was a disappointing outcome and they wanted to know how to fix it, or if they should maybe just toss it out and invest in a new platform.

As I stood in front of the executive team I posed an opening question: “How many of you have been on the platform in the past week?”

Only a single hand went up – the administrator of the platform.

The problem was simple and obvious – because the top executives didn’t see collaboration and engagement as a good use of their time, employees quickly learned that they shouldn’t either.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

Our research shows that leadership participation is crucial for collaboration. Leaders know they should engage with employees, especially via digital and social channels. But they don’t, and they offer a string of common excuses such as “I don’t have enough time” or “Nobody cares what I had for lunch.” More than anything else, they fear that engaging will close the power distance between them and their employees, thereby lessening their ability to command and control.

Here are three ways for leaders to take the first steps to becoming what I call an engaged leader – a person who is confident extending their leadership through and deeply into digital channels.

1. Listen at scale. At Red Robin, a chain of over 450 casual restaurants, Chris Laping, the CIO and senior vice president of business transformation, spearheaded the company-wide implementation of Yammer, an enterprise social network. When the chain launched its Pig Out Burger in 2012, employees posted that the new menu item was getting panned by customers. Reviews flooded in and were funneled to executives and to the test kitchens at headquarters. “Managers started talking on Yammer about ways to tweak the Pig Out recipe and four weeks later we had an improved, kitchen-tested version to roll out to customers,” Laping shared. “That’s a process that would have taken 12 to 18 months before.”

Laping and many other executives have realized that the simple act of listening—and letting colleagues know that they are being heard—is the first crucial step to meaningful collaboration. Determine who you want to listen to based on where collaboration would be most useful to your organization: who are they, what are their biggest pain points, what information do you need to make key decisions? In this case, the collaboration tool could be any sort of feedback mechanism—a bulletin board or even an email inbox is better than no feedback loop. The key is that you, as a leader, need to be on the other end, eager and open to learn and listen.

2. Share to shape. Rosemary Turner, the president of UPS North California District, has a major problem—when her team of 17,000 people are doing a good job they don’t see much of each other. That’s because her people are in trucks, on loading docks, or making sales calls. To keep people connected, Turner uses Twitter because it’s a platform that UPS employees are already comfortable with. Turner uses Twitter to share updates such as “Stay away from the Bay Bridge—there’s an accident” and so on. She also uses it to recognize employees, posing with them in pictures and sharing them online.

Because of how easily she shares in social channels, her people trust her. What’s more, this dovetails with the wider “open-door policy” at UPS, whereby employees, customers, and vendors are encouraged to maintain an open dialogue with company leadership. She shared, “I am finding that when I send out a blast on Twitter, I get just as much if not more reaction than if I send out a survey internally.” Turner’s approach to sharing enables employees to reach her anytime—thereby achieving her goals as well as the larger corporate mandate for openness.

To get started with sharing, identify the platform your employees are already using. Then think of a story you can tell there that will inspire someone to take action toward achieving a key objective. You could share the highlights of a customer conversation or a news article that reinforces a strategic decision. As a leader, the key is to start collecting and sharing in order to shape specific outcomes. While it’s true that no one really cares what you had for lunch, they are keenly interested in what you discussed over lunch. Rather than expecting employees to guess what’s important to you, now you can tell them, easily, with stories and pictures on the digital channels they already use.

3. Engage to transform. David Thodey, the CEO of Telstra, the largest telecommunications company in Australia, wanted to make it crystal clear that he was serious about using the organization’s enterprise social network for business. So he used it to ask, “What processes and technologies should we eliminate?” The question received over 700 responses within the first hour, and gave Thodey an immediate and intimate look into what wasn’t working at Telstra. But more importantly, Thodey and his executive team used the platform for the follow-up discussion, signaling that they were serious about creating a dialog to make making meaningful decisions in digital channels. By being responsive and closing the loop digitally, Thodey demonstrated that employee participation made a difference.

Employees are smart—they won’t waste their time on stunts that are purely for show. Think about the types of engagements you want to have in digital channels—with whom, about what, and when. Engaging to transform is the capstone step in the journey to becoming an engaged leader. It involves listening and sharing (both are integral parts of engagement) and interacting with followers in a thoughtful way, either at scale or one-to-one. This is part of what makes engagement precious—it has tremendous meaning for the people with whom a leader chooses to engage. It is a tool, therefore, that should be used wisely and intentionally. If it becomes commonplace, it may lose its value.

Collaboration depends on trust, and it’s crucial for leaders to learn how to do this in the digital era. The tools themselves matter less than the ability of leaders to describe the intent and purpose of the tools. Simply putting a technology platform in place won’t suffice—you must think through how the organization will change and how you will lead it into and through that change. Unless you have a magic wand, the fairy tale world of collaboration won’t happen simply because you plug in a technology. But you have something better—a leadership vision, strategic objectives, and the passion to guide your organization through the changes ahead. Rely on these foundational leadership skills and learn to extend them into the digital world. If you can do that, then collaboration will find its place in your organization.

Managing in an Age of Winner-Take-All

Over the last 250 years, waves upon waves of scientific and engineering advances have brought about an accelerating rise in living standards that even the two deadliest wars in history could not reverse. In recent decades, the digital revolution, propelled by Moore’s Law, has delivered the most far-reaching yet of general purpose technologies: digital connectivity, which is transforming the entire economy by augmenting the power of the human brain just as surely as steam, the internal combustion engine, and electricity transformed the world by augmenting human brawn.

But as stunning as humankind’s technical achievements have been, they have been only half the story of progress. The advent of the modern organization and the practice of management constitutes a “social technology” that has been equally transformative.

The forces of technology and management will continue to hold equal sway as the 21st century unfolds. Just as those previous technologies brought about dramatic changes in the human condition — including urbanization, mass literacy, large-scale employment, and generalized healthcare — today’s breakthroughs will upend much of the socio-economic infrastructure that was built over the past two centuries. Tumbling transaction costs are altering the economics of organizations and, at a stroke, invalidating old business models. New giants like Amazon, Google, Apple, and Facebook, along with emerging ones like Uber and Airbnb, reap the benefits of new phenomena such as “winner take all” network effects. Advancing technology will leave no aspect of working and private life unaffected — as many more of us will learn as automation expands beyond manual and service work and into the realm of knowledge work.

The question is: How will management advance to influence the path and force of these revolutions? In the past, the effects of technological change were very much shaped by business leaders’ embrace of scientific management with its emphasis on efficient uniformity, and by simplifying assumptions about the behavior of economic man and the efficiency of bureaucratic organizations. But increasingly this industrial-age management mindset is becoming an impediment to our fully realizing the promise of the digital revolution’s technologies. Our accustomed modes of thinking are straitjackets constraining the human energy and creativity these tools could unleash.

Consider management actions such as cutting jobs and investment as a response to currency fluctuations and the resulting accounting impact of those cuts on earnings per share (EPS). These types of cuts are applauded as canny, even heroic, by stock markets — despite their damage to the longer-term value-creating capacity of the enterprise. Share buybacks are preferred to investment in innovation, entrepreneurship, and value creation. And internal innovation often obsessively targets cost cutting instead of the search for new ways to delight customers or to enable employees and partners.

All such moves make sense according to the implacable logic of 20th-century measurements, formulas, and algorithms. There is just one problem: The most important indicators — the unmeasurable ones like trust — are missing from the equations. Our ways of measuring success are reductive and backward-looking. Based on an assumption that the business will just keep doing what it has done in the past, except more efficiently, they offer little guidance in innovation and the creation of new value. Even worse, they downgrade the human being to a mere resource, no more privileged than others in the design of systems to produce short-term gains for shareholders.

Peter Drucker observed decades ago that large organizations and institutions are among the “constitutive elements” of modern society — pillars, if you will, to uphold the values and provide the benefits people hold dear — and given their growing scale this is more true today than ever. But the measures at the heart of today’s management fundamentally misdirect those who are supposed to act as their stewards. This is a situation that cannot endure. Corporations operate at the behest of societies, and are able to do so only because of great privileges conferred on them (not least their very status as legal entities). The reciprocal duty of care to society is therefore not a charitable option, but a fundamental obligation of management.

The digital revolution — the “mother of all technology developments”— marks a fork in the road. One path invites us to depart from industrial-age management practices and mindsets and use the power of information-age technology to augment humanity’s role and importance in business. The other tempts us to apply the new abundance of data and expertise in creating software routines to automate the old logic of organizations, effectively hard-wiring the most dysfunctional rules managers relied on in the past.

To assume that businesses will succeed better by replacing more of their human factor with automated decision-making is to ignore much of the evidence around us. There are ample signs of the limits of rational logic and algorithmic determinism in complex social settings — and always, of the precious, unique capacities of human beings. Education expert and psychologist Howard Gardner has shown that analytical intelligence is just one of seven intelligence skills. The most important decisions are made where there is no replicable logic or algorithm. Rather, they consciously depend on human judgment, intuition, creativity, empathy, and values. This is the domain of entrepreneurial thinking and innovation, of strategy setting, of forming partnerships full of collaboration and trust — work that cannot be done better by whatever Singularity-seeking AI-creature the engineers in Silicon Valley might come up with.

Never in human history has there been a better opportunity to create a new world of prosperity for all. As the ultimate general purpose technology that pervades all aspects of life, digital technology has the potential to unleash what researcher Carlotta Perez calls “a new Golden Age”— one that could surpass the achievements of the steam, electrical, and fossil fuel revolutions. However, this outcome depends on the choices of those in a position to allocate economic resources. In other words, it depends on visionary management.

As Drucker put it: “Managers are society’s major leadership group … They command the resources of society.” Will these leaders choose to put the “creative” back in the process of creative destruction by privileging entrepreneurial investment in customer- and market-creating innovation over short-term profits? Will they use big data, analytics, and artificial intelligence in ways that augment rather than automate human judgment and values, taking them as what they are: tools and instruments to help us navigate a complex world?

To do so will require a new synthesis of the prevalent technocratic logic with a deep understanding of the human condition — nothing less than a reframing of management (along the lines traced by Drucker and others) to combine the best of art and science, imagination and logic, as a liberal art for the 21st century.

This post kicks off a series of perspectives by presenters and participants in the 7th Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 5-6, 2015 in Vienna. The theme: Claiming Our Humanity — Managing in the Digital Age.

The Skills Doctors and Nurses Need to Be Effective Executives

We are witnessing an unprecedented transformation of the health care industry. There has been a rapid growth in jobs and an explosion in the number of start-ups. There are new types of insurance companies such as Oscar; novel provider organizations such as OneMedical, IoraHealth, and ChenMed; and new health information technology companies such as Castlight, Vital, and WellFrame that aim to use technology to improve care and value. Physicians and nurses are being called upon to lead these new health care enterprises — and are assuming a higher level of influence in the business of health care than ever before.

Maximizing the effectiveness of physicians and nurses in these new positions, however, will require different skills than the ones they developed during their clinical training. Having managed or worked with clinical leaders in care-delivery organizations, the pharmaceutical industry, and government, I have observed three skills that are critical to the success of doctors and nurses as they make the transition to management:

Operations management and execution. Many physicians and nurses excel at operations management because it requires the same kind of detail and complexity that is required to effectively manage a large clinical load. In clinical work, we must constantly triage patients and parse significant amounts of low and high-level detail. Many clinicians manage a small operation in the form of their own clinical practice or ward before shifting to leading larger operations.

Still, many clinicians struggle with operations management because they fail to appropriately distinguish between urgent tasks and important, non-urgent tasks — often letting the latter fall by the wayside in favor of the former. Just as a first-year resident physician or a fresh nursing graduate must learn to manage his or her own workflows and develop a plan of attack to manage a patient’s issues, so too must a new clinician executive learn to act with urgency and ownership to build an organization’s workflows and address its problems. Clinician leaders should recognize this potential gap in perspective and work actively to make sure that tasks are appropriately triaged by priority level.

People leadership. When thrust into a management or leadership position, many clinicians have never hired or fired anyone in their life. The instincts crucial to deciding whom to hire and how to hire them managing others’ performance are often underdeveloped in clinical leaders. For example, many clinicians, by nature and by training, are kind and compassionate. While these qualities help engender loyalty, they often make some of the difficult conversations associated with managing people especially challenging.

To accelerate the development of their people-management skills, clinicians should partner closely with fellow business leaders and HR professionals. These colleagues can be instrumental in helping them surface their needs and identify tactics to build and manage high-performance teams. These colleagues can also serve as sounding boards when they must make hard decisions and hold inevitable hard conversations.

Setting and defining strategy. Many clinician leaders are drawn to roles in which they can actively work to define organizational structure and strategy. While strategy roles often tap the strengths and deep frontline knowledge of clinicians, executives with clinician backgrounds often forget that creating a strategy involves making trade-offs. The decision to pursue one set of activities is often a decision not to pursue another. Strategy guru and Michael Porter of Harvard Business School elegantly articulated this when he wrote that strategy is both what we choose to do — and what we choose not to do. Clinicians must work to develop organizational strategies with this simple and important maxim constantly in mind.

One CEO with whom I have worked remarked that physicians and nurses run the risk of losing their clinical identities as they develop into executives. It would be a shame if they did. As they transition to careers in the business of health care, clinicians must hold on to the heart and practice of medicine as they continuously develop the core executive skills required to effectively lead and shape their organizations. Health care will be markedly better for it.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers