Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1305

April 2, 2015

What Great Managers Do to Engage Employees

Less than one-third of Americans are engaged in their jobs in any given year. This finding has remained consistent since 2000, when Gallup first began measuring and reporting on U.S. workplace engagement.

Gallup defines engaged employees as those who are involved in and enthusiastic about their work and workplace. But the majority of employees are indifferent, sleepwalking through their workday without regard for their performance or their organization’s performance. As a result, vital economic influencers such as growth and innovation are at risk.

Gallup’s latest report, State of the American Manager, provides an in-depth look at what characterizes great managers and examines the crucial links between talent, engagement, and vital business outcomes such as profitability and productivity. Our research shows that managers account for as much as 70% of variance in employee engagement scores. Given the troubling state of employee engagement in the U.S. today, it makes sense that most managers are not creating environments in which employees feel motivated or even comfortable. A Gallup study of 7,272 U.S. adults revealed that one in two had left their job to get away from their manager to improve their overall life at some point in their career. Having a bad manager is often a one-two punch: Employees feel miserable while at work, and that misery follows them home, compounding their stress and negatively affecting their overall well-being.

But it’s not enough to simply label a manager as “bad” or “good.” Organizations need to understand what managers are doing in the workplace to create or destroy engagement. In another study of 7,712 U.S. adults, Gallup asked respondents to rate their manager on specific behaviors. These behaviors – related to communication, performance management, and individual strengths – strongly link to employee engagement and give organizations better insights into developing their managers and raising the overall level of performance of the business.

Communicate Richly

Communication is often the basis of any healthy relationship, including the one between an employee and his or her manager. Gallup has found that consistent communication – whether it occurs in person, over the phone, or electronically – is connected to higher engagement. For example, employees whose managers hold regular meetings with them are almost three times as likely to be engaged as employees whose managers do not hold regular meetings with them.

Gallup also finds that engagement is highest among employees who have some form (face-to-face, phone, or digital) of daily communication with their managers. Managers who use a combination of face-to-face, phone, and electronic communication are the most successful in engaging employees. And when employees attempt to contact their manager, engaged employees report their manager returns their calls or messages within 24 hours. These ongoing transactions explain why engaged workers are also more likely to report their manager knows what projects or tasks they are working on.

But mere transactions between managers and employees are not enough to maximize engagement. Employees value communication from their manager not just about their roles and responsibilities but also about what happens in their lives outside of work. The Gallup study reveals that employees who feel as though their manager is invested in them as people are more likely to be engaged.

The best managers make a concerted effort to get to know their employees and help them feel comfortable talking about any subject, whether it is work related or not. A productive workplace is one in which people feel safe – safe enough to experiment, to challenge, to share information, and to support one another. In this type of workplace, team members are prepared to give the manager and their organization the benefit of the doubt. But none of this can happen if employees do not feel cared about.

Great managers have the talent to motivate employees and build genuine relationships with them. Those who are not well-suited for the job will likely be uncomfortable with this “soft” aspect of management. The best managers understand that each person they manage is different. Each person has different successes and challenges both at and away from work. Knowing their employees as people first, these managers accommodate their employees’ uniqueness while managing toward high performance.

Base Performance Management on Clear Goals

Performance management is often a source of great frustration for employees who do not clearly understand their goals or what is expected of them at work. They may feel conflicted about their duties and disconnected from the bigger picture. For these employees, annual reviews and developmental conversations feel forced and superficial, and it is impossible for them to think about next year’s goals when they are not even sure what tomorrow will throw at them.

Yet, when performance management is done well, employees become more productive, profitable, and creative contributors. Gallup finds that employees whose managers excel at performance management activities are more engaged than employees whose managers struggle with these same tasks.

In our Q12 research, Gallup has discovered that clarity of expectations is perhaps the most basic of employee needs and is vital to performance. Helping employees understand their responsibilities may seem like “Management 101” but employees need more than written job descriptions to fully grasp their roles. Great managers don’t just tell employees what’s expected of them and leave it at that; instead, they frequently talk with employees about their responsibilities and progress. They don’t save those critical conversations for once-a-year performance reviews.

Engaged employees are more likely than their colleagues to say their managers help them set work priorities and performance goals. They are also more likely to say their managers hold them accountable for their performance. To these employees, accountability means that all employees are treated fairly or held to the same standards, which allows those with superior performance to shine.

Focus on Strengths over Weaknesses

Gallup researchers have studied human behavior and strengths for decades and discovered that building employees’ strengths is a far more effective approach than a fixation on weaknesses. A strengths-based culture is one in which employees learn their roles more quickly, produce more and significantly better work, stay with their company longer, and are more engaged. In the current study, a vast majority (67%) of employees who strongly agree that their manager focuses on their strengths or positive characteristics are engaged, compared with just 31% of the employees who indicate strongly that their manager focuses on their weaknesses.

When managers help employees grow and develop through their strengths, they are more than twice as likely to engage their team members. The most powerful thing a manager can do for employees is to place them in jobs that allow them to use the best of their natural talents, adding skills and knowledge to develop and apply their strengths.

[image error]

March 30, 2015

Looking for Problems Makes Us Tired

Photo by Andrew Nguyen

When employees see something amiss, you want them to be able to speak up. GM’s safety scandal last year is a good reminder why; the Challenger and Columbia explosions are classic case studies. People often avoid raising difficult issues, so the struggle to encourage this behavior has become a perennial management problem.

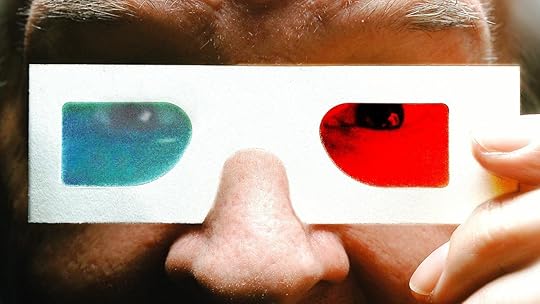

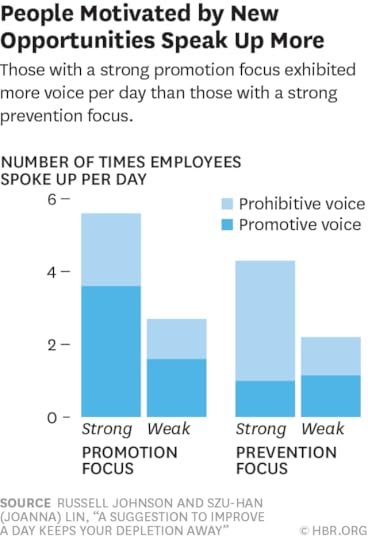

The latest addition to the corpus of research on this suggests why: Speaking up can wear us out. A new paper, forthcoming later this year in the Journal of Applied Psychology, studies the effects of different kinds of speech on employees. In “A Suggestion to Improve a Day Keeps Your Depletion Away,” authors Szu-Han (Joanna) Lin and Russell E. Johnson found that expressing concern and criticism (what’s called prohibitive voice) was more mentally taxing than suggesting ideas for improvement (promotive voice), and this mental fatigue led to increased reluctance to speak up again, later. Conversely, speaking up with ideas seemingly reduced employees’ fatigue.

This isn’t the first time the researchers have studied how desirable behaviors have consequences. We know that being fair, for example, leads to more motivated employees — but Johnson’s previous research found that enforcing fairness can take a mental and emotional toll on supervisors. He and Lin suspected that constantly monitoring for problems or mistakes could have a similar tiring effect.

To find out, they conducted two studies. Along with measuring the subsequent effects of prohibitive and promotive voice, they also looked at the personalities that prompted them. Psychologists have long drawn a distinction between promotion-focused personalities and prevention-focused personalities. People with a strong promotion focus are motivated by new opportunities and the potential for gain, while those with a strong prevention focus are more motivated by avoiding risk and loss.

In the first study, they collected data from self-reported surveys in four waves, separated by one-week intervals. Participants were asked to rate various statements on a five-point scale, with five being the most accurate. And according to the researchers, a separate validation study showed that the self-reports were good proxies for actual voice behavior.

The first week, researchers assessed focus with items such as: “Right now, I am focused on achieving positive outcomes at work” and “Right now, I am focused on preventing negative events at work.” The second week, they assessed voice behavior: “I proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit;” “I dare to point out problems when they appear in the unit, even if that would hamper relationships with colleagues.” Third, they measured mental fatigue or depletion: “I feel drained;” “Right now, it would take a lot of effort for me to concentrate on something.” Week four, they measured both voice behaviors again.

They used the same survey methods in the second study, except over four consecutive days. This time, they also controlled for things like perceived safety and motivation, and measured ensuing task performance.

The findings were consistent across both studies. Promotion focus predicted increases in promotive voice (and, also, though to a lesser extent, prohibitive voice). Prevention focus only predicted increases in prohibitive voice. And it’s worth noting that the two behaviors aren’t mutually exclusive — an employee can exhibit both types of voice in a day. Here are the averages from study 2:

The researchers also observed that expressing prohibitive voice increased employees’ sense of mental fatigue, while promotive voice appeared to reduce it. One potential reason for this, Johnson explained, could be that there’s a certain amount of excitement involved in thinking about how to make things better, and this might help counteract feelings of fatigue. When you look at how participants in the second study reported their fatigue, you can see that employees felt twice as drained when they had a strong prevention focus (and/or a weak promotion focus).

“In terms of wellbeing at work, it really does pay to not be constantly thinking about potential problems and mistakes that may be around the corner,” Johnson said. “It’s much better to think about potential good stuff that can happen and the benefits of being successful, as opposed to the pains of failure.”

Both studies suggested that increased fatigue also led to less speaking up overall in the future. After bringing up problems and concerns, employees felt more mentally drained the next week (study 1) or day (study 2), and were then less likely to speak up with any issues or ideas the following week or day. And in the second study, they also found that fatigue predicted lower productivity the next day, as well as more deviant and abusive behavior—a finding that’s consistent with other studies on fatigue, ethics, and engagement.

While there are some strong implications here, there were limitations to the research. First, causation could not be conclusively proved. Even though focus, voice, and fatigue were measured over time and in an order that suggests causation, the studies’ observational design couldn’t totally confirm this effect. Plus, other explanations still exist. Maybe how much energy we feel shapes what we focus on, and how we act, rather than vice versa. And while the researchers described several factors (goals, emotions, and so on) that may connect someone’s focus with their propensity to speak up, they didn’t measure those factors. In addition, the researchers caution that more research into types of fatigue — mental, physical, and emotional — is needed.

Employee silence will always be an issue, as will be figuring out how to encourage more (and better) voice. But in light of this research, it’s important to also consider how such speaking out affects the people doing the speaking. If you want your employees to be more vocal about mistakes and potential problems, be aware that doing so might wear them out.

[image error]

Two Ways to Clarify Your Professional Passions

Have you ever noticed that highly effective people almost always say they love what they do? If you ask them about their good career fortune, they’re likely to advise that you have to love what you do in order to perform at a high level of effectiveness. They will talk about the critical importance of having a long-term perspective and real passion in pursuing a career. Numerous studies of highly effective people point to a strong correlation between believing in the mission, enjoying the job, and performing at a high level.

So why is it that people are often skeptical of the notion that passion and career should be integrally linked? Why do people often struggle to discern their passions and then connect those passions to a viable career path? When people hear the testimony of a seemingly happy and fulfilled person, they often say, “That’s easy for them to say now. They’ve made it. It’s not so easy to follow this advice when you’re sitting where I’m sitting!” What they don’t fully realize is that connecting their passions to their work was a big part of how these people eventually made it.

Passion is about excitement. It has more to do with your heart than your head. It’s critical because reaching your full potential requires a combination of your heart and your head. In my experience, your intellectual capability and skills will take you only so far.

Regardless of your talent, you will have rough days, months, and years. You may get stuck with a lousy boss. You may get discouraged and feel like giving up. What pulls you through these difficult periods? The answer is your passion: it is the essential rocket fuel that helps you overcome difficulties and work through dark times. Passion emanates from a belief in a cause or the enjoyment you feel from performing certain tasks. It helps you hang in there so that you can improve your skills, overcome adversity, and find meaning in your work and in your life.

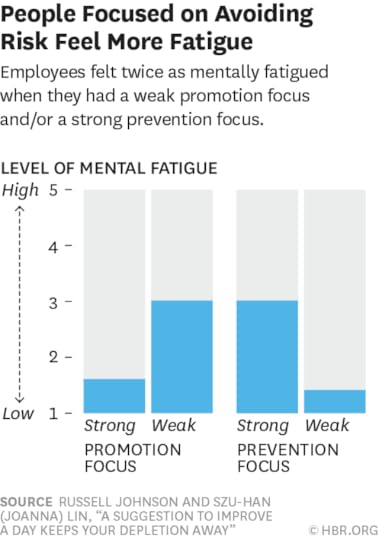

Adapted from

What You’re Really Meant to Do: A Road Map for Reaching Your Unique Potential

Leadership & Managing People Book

Robert Steven Kaplan

25.00

Add to Cart

Save

Share

In talking to more experienced people, I often have to get them to mentally set aside their financial obligations, their role in the community, and the expectations of friends, family, and loved ones. It can be particularly difficult for mid-career professionals to understand their passions because, in many cases, the breakage cost of changing jobs or careers feels so huge to them that it’s not even worth considering. As a result, they try not to think too deeply about whether they like what they’re doing.

The problem for many mid-career people is that they’re experiencing a plateau that is beginning to alarm them and diminish their career prospects. This plateau is often a by-product of lack of passion for the job. It may be that the nature of the job has changed or the world has changed, and the mission and tasks of their career no longer arouse their passions. In other cases, nothing has changed except the people themselves. They simply want more meaning from their lives and professional careers.

Of course, these questions are never fully resolved. Why? It’s because there are many variables in play, and we can’t control all of them. The challenge is to be self-aware.

That’s difficult, because most of our professional days are chaotic. In fact, life is chaotic, and, sadly, we can’t usually predict the future. It feels as if there’s no time to reflect. So how are you supposed to get perspective on these questions?

I suggest that you try several exercises. These exercises may help you increase your self-awareness and develop your abilities to better understand your passions. They also encourage you to pay closer attention to and be more aware of the tasks and subjects you truly find interesting and enjoyable.

Your Best Self

This exercise involves thinking back to a time when you were at your best. You were great! You did a superb job, and you really enjoyed it. You loved what you were doing while you were doing it, and you received substantial positive reinforcement.

Remember the situation. Write down the details. What were you doing? What tasks were you performing? What were the key elements of the environment, the mission, and the nature of the impact you were making? Did you have a boss, or were you self-directed? Sketch out the complete picture. What did you love about it? What were the factors that made it enjoyable and helped you shine?

If you’re like most people, it may take you some time to recall such a situation. It’s not that you haven’t had these experiences; rather, you have gotten out of the habit of thinking about a time when you were at your best and enjoying what you were doing.

After sketching out the situation, think about what you can learn from this recollection. What are your insights regarding the nature of your enjoyment, the critical environmental factors, the types of tasks you took pleasure in performing, and so on? What does this recollection tell you about what you might enjoy now? Write down your thoughts.

Mental Models

Another approach to helping you think about your desires and passions is to use mental models. That is, assume xyz, and then tell me what you would do — and why. Here are examples of these models:

If you had one year left to live, how would you spend it? What does that tell you about what you enjoy and what you have a passion for?

If you had enough money to do whatever you wanted, what job or career would you pursue?

If you knew you were going to be highly successful in your career, what job would you pursue today?

What would you like to tell your children and grandchildren about what you accomplished in your career? How will you explain to them what career you chose?

If you were a third party giving advice to yourself, what would you suggest regarding a career choice?

Although these mental models may seem a bit silly or whimsical, I urge you to take the time to try them, consider your answers, and write them down. You’re likely to be surprised by what you learn. Each of them attempts to help you let go of fears, insecurities, and worries about the opinions of others — and focus on what you truly believe and desire.

Passion is critical in reaching your potential. Getting in touch with your passions may require you to give your fears and insecurities a rest and focus more on your hopes and dreams. You don’t need to immediately decide what action to take or assess whether your dream is realistic. There is an element of brainstorming in this effort: you don’t want to kill ideas before you’ve considered them. Again, allow yourself to focus on the what before you worry about the how. These exercises are about self-awareness, first and foremost. It is uncanny how much more likely you are to recognize opportunities if you’re aware of what you’re looking for.

This article was adapted from What You’re Really Meant to Do, by Robert Steven Kaplan.

[image error]

Overcome Your Company’s Resistance to Data

When I started work on data quality nearly 30 years ago, I had no idea how revolutionary most people would find the concept of preventing data errors at their sources. Nor did I anticipate the outsize resistance that putting this simple idea into practice would engender. Over the years, I’ve learned some hard lessons about what it takes to advance a data agenda, whether that’s advocating for a new data quality program, a different type of data, or a fresh strategy that relies on data. These lessons are particularly timely as more and more people find opportunities to push data into previously uncharted territory.

Those advancing a data agenda — I call them “data revolutionaries” — need to realize just how disruptive they are to most people. Too many data revolutionaries focus only on the potential benefits: the money to be saved, the better decisions that will result, the new markets to conquer. They’re seemingly blind to the changes people and organizations must make to realize those benefits. Everything is disrupted, from the work itself to business relationships to power structures. Many people will feel uncomfortable — even fearful — as they learn new skills, build new relationships, and rate their performance differently. Some others may lose their jobs.

Given the disruption, resistance is both normal and natural. Bear in mind that most new ideas (particularly in the data space) fail. While many ideas are just plain bad and deserve to flop, too many good ones fail because those promoting them are too idealistic and politically naïve. Don’t let resistance surprise you.

In my experience, I’ve encountered four main types of resistors:

Virulent naysayers: Some resistors are opposed to any change, no matter what the circumstance. Often irrationally so. I’ve found it best to ignore them. You’re unlikely to change their minds and ignoring them frees up your time to work on more productive things.

Passive resistors: Some opposition is passive, as people wait to see which way the political winds blow. People have seen plenty of ideas come and go (people at one company I worked with refer to this as the “management flavor of the month”), and they see no sense committing. This can be frustrating, especially since many will privately admit that they like your ideas. Communicate constantly with these people — listen to their concerns, explain your vision for the future, and ask for their support.

Reasonable challengers: Other resistance is truly positive and comes from people with valid objections to your program. Listen to these people and understand their concerns. Addressing them can improve your program. Such individuals can become your biggest, most vocal supporters.

Organizational resisters: Some opposition is organizational, in the form of committees that vet ideas, approve budgets, allocate space, set performance standards, and so forth. I often find a not-so-subtle bias in such committees; they favor the status quo, starve new ideas of resources, set barriers, and beat those who think differently into submission. This problem is much more difficult. You must build a base of support to solve it.

Fortunately, many people in your organization also have open minds and can help you advance your data initiative — and overcome some of the resistance you face. You must make supporters out of them. To do so, first demonstrate that your ideas can work. A small pilot study, perhaps with one category of data, in the “data lab,” or in a single department, is the best way to do so.

Next, ask for their help. Too many data revolutionaries don’t do this. They may be too enamored of their ideas, overconfident in their abilities to take on the world, or unwilling to give up control. Their efforts are almost certainly ill-fated unless and until they build a base of support. I almost always find plenty of people willing, even eager, to help. But they don’t often come forward on their own. You have to ask.

You need senior managers among your most active supporters — I’ve yet to see a data agenda advance without senior leaders. They are in a unique position to provide the resources needed to scale up, break the organizational barriers noted above, and convince the passive resistors to sign on.

Once you’ve asked for what you need, actively engage your supporters in the effort. Help them see “what’s in it for me,” and ask them to do specific things. Too many data revolutionaries brief a senior manager, get a nod of support, then walk away. It is okay to admit, “I’m having a little trouble with the Budget Committee. I’m not getting what I need. Can you help me?”

Finally, really listen to those who’ve navigated similar terrain. They can show you ways to speed up, how to get around barriers, and help you make connections. You also need one person who will look you squarely in the eye and tell you when you’re just plain wrong, so you can correct course.

My last piece of advice is certainly the most important: Above all things, persist. While having a great idea is essential, it is not enough. A data agenda prevails because those advancing it work harder than anyone else and persist through thick and thin. They convince some people and outlast others. They figure out ways to make those who join them look good. And they work with senior leaders to show them how they could contribute while at the same time minimizing their exposure should the effort fail.

[image error]

How to Deliver Bad News to Your Employees

Kenneth Andersson

Delivering bad news is tough. It’s even harder when you don’t agree with the message or decision you’re communicating. Maybe you have to tell your star performer that HR turned down her request for a raise or to inform your team that the company doesn’t want them working from home any longer. Should you toe the line and act like you agree with the decision or new policy? Or should you break ranks and explain how upset you are too?

What the Experts Say

“In a managerial role, it’s natural to feel ambivalence” when delivering disappointing news, says Joshua Margolis, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School. This is because you always have two different parties’ interests at heart — that of your employees and that of upper management. Talent management expert and humanresources.about.com writer Susan Heathfield agrees: “As a manager, you walk a fine line between being a company advocate and an employee advocate.” Reconciling the two is no easy task and you often feel stuck between a rock and a hard place. Here’s how to navigate the situation.

Prepare for the conversation

Be sure to have all your ducks in a row before talking with your employees. Specifically, you need to know how the decision was made, who was consulted, what other possibilities were discussed, and the rationale behind the final outcome. “The manager should take as much time as necessary so that she is confident in her own understanding of the answers,” says Heathfield. “And, if you aren’t sure, go back to your boss, HR, or whomever made the decision to ask these questions again.” Margolis agrees: “If you think all concerns weren’t heard, you should seek further explanation and, if warranted, appeal the decision before conveying anything to your team.”

Further Reading

[image error]

How to Handle Difficult Conversations at Work

Communication Article

Rebecca Knight

Start by changing your mindset.

Save

Share

Be direct and avoid mixed messages

One of the biggest factors in whether employees will listen to and accept bad news is how it’s delivered. Watch your body language. “Be sure that your nonverbal cues aren’t telegraphing something different than what you’re saying,” warns Heathfield. Slumping your shoulders, avoiding eye contact, or fidgeting will send the wrong message. Even if this is an obvious setback for everyone, you need to confidently convey the information and leave no room for interpretation. Consider rehearsing what you’re going to say ahead of time. “Go to a buddy — a fellow manager — who can give you feedback on how you’re appearing,” she says.

Be thoughtful and caring but don’t sugar coat the news. That makes it more difficult for people to digest. Instead “laser-focus on the decision and explain why it’s the final call,” says Heathfield. “For example, if you need to explain to your team that the company has banned a particular software they’ve been using, you might say: We’ve made a decision. You may not use this software going forward. Our IT department determined that it’s a threat to our security system.

Explain how the decision was made

Studies show that people are willing to accept an unfavorable outcome if they believe the decision-making process was sound. This is often called “procedural fairness.” You might say to your employees, for example: Here’s the process that was followed, the people we spoke with, and where things came out.

Heathfield and Margolis agree that sharing your viewpoint on the decision is not necessary, and can in fact cause harm. “Managers have a great deal of influence on employees. If they give them the ammunition of ‘not even my boss believes this is right’ it can spark a lot of chaos, turmoil, and unhappiness,” says Heathfield. However, Margolis says, if you feel you need to acknowledge your disappointment in order to maintain credibility with the individual or team, you might add something like: It’s not ideally where we wanted it to land but they followed these steps.

If you disagreed with the process, be sure to share your misgivings with the higher-ups, but don’t do it with your people. “You won’t do anyone any favors by telling your team that you think the process was rigged,” Margolis explains. Instead, say: This is how we made the decision this time but we’re going to look into how these decisions are made going forward.

Allow for venting, not debate

Once you’ve delivered the news and explained the decision-making process, ask the individual or group for a reaction. “You have to listen to their concerns,” says Margolis, even if you’re uncomfortable. “It’s part of your role as a manager to absorb some of that emotion, whether it’s anger, surprise, or something else.” Heathfield points out that this is when most managers are quick to align with the team and say, “I think this is a bad decision, too.” But resist that impulse. “The one thing you don’t want to do is get into a debate about the merits of [a] decision” that has already been made, Margolis says. “This is not a time to revisit it,” Heathfield agrees.

Focus on the future

Once you’ve heard them out, take a break — this may be a few minutes or a few days — and let people process the information. Then help the team or individual move forward. Margolis suggests enlisting them in the problem-solving by saying something like: Now how do we make this best work given the concerns you have? Be sure to indicate that you are a partner in doing whatever comes next. If people are disappointed, they’ll need your support.

Putting it all together

To give you a sense of what this all sounds like, consider the following example. If you have to tell a direct report that he didn’t get the promotion he was hoping for you can say something like: We’re unable to give you the promotion (be direct). HR says that in order to be at a director level you need to have responsibility for a larger scope of the business (explain the rationale). It’s not necessarily how I’d approach it, but I understand why as an organization we do it that way (express procedural fairness). What questions do you have for me? How are you feeling? (Allow for venting). Now let’s look at what you can do to get that promotion next year or the following one (focus on the future).

Principles to Remember

Do:

Understand why the decision was made before sharing the news

Prepare and rehearse what you’re going to say

Explain the rationale and the process for making the decision

Don’t:

Sugarcoat the news — be clear and direct

Let your body language belie your words

Allow people to debate the merits of the decision — focus on moving forward

Case study #1: Explain the process and stand by the decision

Mark Costa’s (not his real name) team of IT professionals had put a lot of work into researching three software options their company might use to monitor employee’s online activities. They analyzed the costs and benefits for each one and strongly recommended the software that cost the most upfront but would yield the most long-term benefits, expanding easily as the company grew. But when management reviewed the team’s work, they decided to instead go with the cheapest option. Mark didn’t agree but he understood the reasoning: The recommended package was deemed too expensive and investing in it would result in a short-term risk to the cash position. He was therefore “happy to explain the rationale and support the process,” he says.

He walked the group through the logic of the decision and met one-on-one with members who were still unhappy with the decision, always keeping his personal opinion to himself. “I made it clear that there were pros and cons but there was no point in saying anything else as it would have demotivated the team,” he explains. “To be honest, as a manager, I sometimes have to take one for the people above me.” He also didn’t share some of the details he’d been privy to, like the concern about the company’s cash flow. He didn’t want to worry his employees, especially about something they had no control over.

The team took it well. They were disappointed that they had spent so much time coming up with the recommendation, but Mark focused them on their other work. “At the end of the day, there were bigger issues to address,” he says.

Case study #2: Focus on what you can do to help the person

As a regional HR director for a global company, Jihad Gafour, was responsible for onboarding a new project director to the Middle East office. The new hire, Sulayman (not his real name), had been recruited from outside the country and had quit his job to join Jihad’s firm, moving his wife and family with him. But only a few weeks after his start date, upper management began to complain about Sulayman’s performance and to question his trustworthiness.

Soon, the CEO asked Jihad to fire the new hire. Jihad worried that Sulayman was being judged unfairly since he was an outsider challenging the company’s status quo and told the CEO that, in his opinion, this was an unjustified termination. But the CEO would not reverse his decision, so Jihad set about preparing for the conversation with Sulayman. “I gathered a list of recruitment managers and consultants I thought would help him, his wife, and kids,” he says. Then, although almost all of his previous communication with the man had been over the phone, he arranged a face-to-face meeting. He cut right to the chase. He said, “As per the labor law and the contract between you and the company, senior management has decided to terminate the employment contract with immediate effect.”

Despite his repeated attempts to understand the reasons behind the firing, Jihad felt he couldn’t explain the rationale so he told Sulayman that he would be happy to set up a meeting with the CEO. Jihad offered his list of contacts, and closed the conversation by offering his help, saying, “Let me know if you need any other services from HR or from me personally. Here is my number.” Sulayman shed tears during the meeting but came away understanding that the decision was final. He did request the meeting with the CEO and Jihad succeeded in getting the two together, despite some initial resistance from the boss.

Sulayman found another position soon after, and several months later, Jihad also left the company. They’ve both stayed in touch.

[image error]

March 27, 2015

The Most Productive Way to Develop as a Leader

Everybody loves self-improvement. We want to get smarter, network better, be connected, balance our lives, and so on. That’s why we’re such avid consumers of “top 10” lists of things to do to be a more effective, productive, promotable, mindful — you name it — leader. We read all the lists, but we have trouble sticking to the “easy steps” because while we all want the benefits of change, we rarely ever want to do the hard work of change.

But what if we didn’t think of self-improvement as work? What if we thought of it as play — specifically, as playing with our sense of self?

Let’s say an executive we’ll call John lacks empathy in his dealings with people. For example, he’s overly blunt when he gives feedback to others and he’s not a very good listener. Thanks to a recent promotion, he needs to be less of a task-master and more people-oriented. He wants to improve on the leadership skills he’s been told are vital for his future success but, unfortunately, they are alien to him. What can he do?

John has two options. He can work on himself, committing to do everything in his power to change his leadership style from model A to model B. Or he can play with his self-concept by “flirting” with a diverse array of styles and approaches and withholding allegiance to a favored result until he is better informed. The difference between these two approaches is both nuanced and instructive for anyone striving to transform how they lead.

Let’s first imagine John working on himself. The adjectives that come to mind include diligent, serious, thorough, methodical, reasonable, and disciplined. The notion of “work” evokes diligence, efficiency, and duty — focusing on what you should do, especially as others see it, as opposed to what you want to do. I imagine John making a systematic assessment of his strengths and weaknesses, collecting feedback on areas for improvement, setting concrete SMART goals, devising a timetable and strategies for achieving them, possibly engaging a coach psychologist to dig deeper into the root causes of his poor people skills, monitoring his progress, and so on. With a clear end in mind, he proceeds in a logical, step-by-step manner, striving for progress. There is one right answer. Success or failure is the outcome. We judge ourselves.

Now, let’s imagine John being playful with his sense of self. What adjectives come to mind now? The words lively, good-humored, spirited, irreverent, divergent, amused, and full of fun and life now spring to mind. The notion of “play” evokes an element of fantasy and potential — the “possible self,” as Stanford psychologist Hazel Markus calls the cacophony of images we all have in our heads for who we might become. I imagine John saying, “I have no idea what to do, but let’s just try something and see where this leads me.” If it doesn’t work, he’s free to pivot to something completely different because he isn’t invested in his initial approach. Trial and error takes time, but getting to finish line first isn’t the objective, enjoyment is. Many different and desirable versions of our future self are possible. Learning, not performance is the outcome. We suspend judgement.

Whatever activity you’re engaged in, when you are in “work” mode, you are purposeful: you set goals and objectives, are mindful of your time, and seek efficient resolution. You’re not going to deviate from the straight and narrow. It’s all very serious and not whole lot of fun. Worse, each episode becomes a performance, a test in which you either fail or succeed.

In contrast, no matter what you’re up to, when you’re in “play” mode, your primary drivers are enjoyment and discovery instead of goals and objectives. You’re curious. You lose track of time. You meander. The normal rules of “real life” don’t apply, so you’re free to be inconsistent — you welcome deviation and detour. That’s why play increases the likelihood that you will discover things you might have never thought to look for at the outset.

Much research shows how play fosters creativity and innovation. I’ve found that the same benefits apply when you are playful with your self-concept. Playing with your own notion of yourself is akin to flirting with future possibilities. Like in all forms of play, the journey becomes more important than a pre-set destination. So, we stop evaluating today’s self against an unattainable, heroic, or one-size-fits all ideal of leadership that doesn’t really exist. We also stop trying to will ourselves to “commit” to becoming something we are not even sure we want to be — what Markus calls the “feared self,” which is composed of images of negative role models, for example, a former boss who we worry we’ll come to resemble if we stray too far from our base of technical expertise. And, we shift direction, from complying with what other people want us to be to becoming more self-authoring. As a result, when you play, you’re more creative and more open to what you might learn about yourself.

The problem is we don’t often get — or give ourselves — permission to play with our sense of self. As organizational sociologist James March noted in his celebrated elegy to playfulness, The Technology of Foolishness, the very experiences children seek out in play are the ones organizations are designed to avoid: disequilibrium, novelty, and surprise. We equate playfulness with the perpetual dilettante, who dabbles in a great variety of possibilities, never committing to any. We find inconstancy distasteful, so we foreclose on options that seem too far off from today’s “authentic self,” without ever giving them a try. This stifles the discontinuous growth that only comes when we surprise ourselves.

Paradoxically, my research finds that often the most productive way to develop as a leader is the most seemingly inefficient. It involves adopting a stance of what I call “committed flirtation,” fully embracing new possibilities as if they were plausible and desirable, but limiting our commitment to being that person to the “play mode.” I’ve found that committed flirtation frees people like John to do three things that will help him become a better leader:

In “pretend” play, it’s OK to borrow liberally from different sources. A playful attitude would free John from being “himself” as he is today. Play allows him to try out behaviors he has seen in more successful bosses and peers, perhaps stealing different elements of style from each to form his own pastiche, as opposed to clinging to a straight-jacketing sense of authenticity.

Playfulness changes your mind-set from a performance focus to a learning orientation. One of the biggest reasons we don’t stretch beyond our current selves is that we are afraid to suffer a hit to our performance. A playful posture might help John feel less defensive about his old identity — after all, he’s not forever giving up his “secret sauce” and fountain of past success, he’s just practicing his bad swing.

Play generates variety not consistency. By suspending the cardinal rule of unswerving, reliable behavior, it allows our “shadow,” as Carl Jung called the unexpressed facets of our nature, fuller expression. John might, for example, sign up for some new projects and extracurricular activities, each a setting in which he’s free to rehearse behaviors that deviate from what people have come to expect of him. He’s not being mercurial; he’s just experimenting.

Psychoanalyst Adam Phillips once said, “people tend to flirt only with serious things — madness, disaster, other people.” Flirting with your self is a serious endeavor because who we might become is not knowable or predictable at the outset. That’s why it’s as inherently dangerous as it is necessary for growth.

[image error]

Reassess Millennials’ Social Sharing Habits

Millennials are often maligned for their constant technology use and obsession with the social approval signaled by likes, shares, and retweets. But organizations need to start recognizing the benefits of such behavior and harnessing it. This generational cohort will, by some estimates, account for nearly 75% of the workforce by 2025. And, according to a recent Deloitte survey of 7,800 people from 29 countries, only 28% of currently employed Millennials feel their companies are fully using their skills.

How can smart leaders better leverage the talents of these future leaders? As organizational consultants, we tell our clients to consider what makes them tick and to see the value in those interests. Two points are of particular note:

First, social sharing. Neuroscientists have shown that any kind of positive personal interaction lights up a part of the brain called the temporoparietal junction, which stimulates the production of oxytocin, “the feel-good hormone.” Millennials, who have grown up interacting online, are able to get that same high, more often, though technology, by posting, messaging, forwarding and favoriting multiple times a day. They crave that connection and are therefore natural team players.

Second, constant, complex data flow. Research tells us that multitasking is impossible: people can only do two things at once if one of those things is routine. Also, those who regularly use multiple forms of media are more prone to distraction than those who don’t. But, according to Nielson Neurofocus, EEG readings suggest that younger brains have higher multi-sensory processing capacity than older ones and are most stimulated – that its more engaged with and more likely to pay attention to and remember – dynamic messages. Millennials probably aren’t more effective multitaskers, in the strict sense of the world, but, in their current stage of brain development, they seem better able to tolerate and integrate multiple streams of information.

Angela Ahrendts, the former CEO of Burberry, recognized that she could turn these two hallmarks of Millennial behavior into an asset for the fashion brand. In 2006, she hired a large number of “digital natives,” as she called them, to do what they do best: socialize through technology. As she explains in this video, they created an expansive digital platform, which transformed the company’s image and dramatically accelerated its growth. One highlight was “Tweet Walk,” which turned Burberry’s traditional runway show into a live web broadcast.

While Baby Boomers might see phones, tablets, and other devices as distractions, Millennials use them to collaborate and innovate in real time. While Gen-Xers may view aggressive social sharing as an unhealthy mix of the personal and professional, Millennials see it as a way to gather input and learn from others. Millennials understand, embrace and are evolving with our exponentially expanding digital world. Instead of judging their behavior, we need to better leverage it.

[image error]

How to Run a Great Virtual Meeting

Virtual meetings don’t have to be seen as a waste of time. In fact, they can be more valuable than traditional face-to-face meetings. Beyond the fact that they’re inexpensive ways to get people together – think: no travel costs and readily available technology – they’re also great opportunities to build engagement, trust and candor among teams.

Several years ago, my company’s Research Institute embarked on an exploration of the “New People Rules in a Virtual World” to explore how technology is shaping our relationships and how we collaborate. This multiyear journey also evolved my thinking on the subject, helping me recognize that virtual is not the enemy of the physical if key rules and processes are maintained and respected.

Going back through that research now, I’ve put together a comprehensive list of some simple do’s and don’ts to help you get the most out of your next virtual meeting.

Before the meeting:

Turn the video on. Since everyone on the call is separated by distance, the best thing you can do to make everyone at least feel like they’re in the same room is to use video. There are many options to choose from, such as WebEx and Skype. Video makes people feel more engaged because it allows team members to see each other’s emotions and reactions, which immediately humanizes the room. No longer are they just voices on a phone line; they’re the faces of your co-workers together, interacting. Without video, you’ll never know if the dead silence in a virtual meeting is happening because somebody is not paying attention, because he’s rolling his eyes in exasperation or nodding his head in agreement. Facial expressions matter.

Cut out report-outs. Too many meetings, virtual and otherwise, are reminiscent of a bunch of fifth graders reading to each other around the table – and that’s a waste of the valuable time and opportunity of having people in a room together. The solution is to send out a simple half-page in advance to report on key agenda items – and then only spend time on it in the meeting if people need to ask questions or want to comment.

Further Reading

Running Meetings (20-Minute Manager Series)

Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

This type of pre-work prepares participants to take full advantage of the meeting by thinking ahead about the content, formulating ideas or getting to know others in the group, which can help keep team members engaged, says business consultant Nancy M. Settle-Murphy in her book Leading Effective Virtual Teams. But one thing is critical: It has to be assumed that everyone has read the pre-read. Not doing so becomes an ethical violation against the team. I use the word “ethical” because it’s stealing time from the team — and that’s a disrespectful habit. The leader needs to set the tone aggressively that the pre-read should be done in advance.

Come prepared with the team’s opinions. Not only do you need to do your pre-reads, but once you see the agenda, make sure you discuss with your team what is going to be covered – that is, do your own due-diligence. What happens all too often is that people get on virtual calls with a point of view, but because they haven’t done any real homework before the call, they end up reversing their opinions once the call has ended and they’ve learned new information that they could have easily obtained in advance. If there’s a topic that seems to have interdependencies with people who work in our location, get their input ahead of time so you’re best representing those constituents in the meeting.

During the meeting:

Connect people. People perform better when they are comfortable with each other, which affords a greater degree of candor and mutual interest. Your job as a leader, particularly when people may not know each other, is to make them feel connected so you can have a productive meeting. How? Do a personal-professional check-in at the beginning of each meeting. Have team members take one minute and go around to talk about what’s going on in their lives personally and professionally. Go first to model the approach for what doing it “right” looks like, in terms of tone and candor. Remind everyone to respect each other by not interrupting and to only say what they’re comfortable sharing with the group.

Encourage collaborative problem solving. A collaborative problem solving session replaces the standard “report-outs” that can weigh meetings down. It’s when the leader raises a topic for group discussion and the team works together – and sees each other as sources of advice – to unearth information and viewpoints, and to generate fresh ideas in response to business challenges.

Give each person time on the agenda. Along with collaborative problem solving, giving each person time on the agenda fosters greater collaboration and helps get input from all the team members. Here’s how it works: In advance of the session, have team members write up an issue they’ve been struggling with and bring it to the table, one at a time. Each team member then gets five minutes on the agenda to discuss his or her issue. The group then goes around the meeting so everyone gets a chance to either ask a question about it or pass. After the team member answers everyone’s questions, people then get an opportunity to offer advice in the “I might suggest” format, or pass. Then, you move on to the next issue. It’s a very effective use of a collaboration technique that could easily be managed in a virtual environment.

Kill mute. In a co-located meeting, there are social norms: You don’t get up and walk around the room, not paying attention. Virtual meetings are no different: You don’t go on mute and leave the room to get something. In a physical meeting, you would never make a phone call and “check out” from the meeting. So in a virtual meeting, you shouldn’t press mute and respond to your emails, killing any potential for lively discussion, shared laughter and creativity.

As leaders, we need to establish a standard: Just because you’re in a virtual meeting and it’s possible to be disrespectful, it has to be understood that it’s unacceptable. We’re talking about civility and respect for people, so if you wouldn’t do it in person, don’t do it virtually.

Ban multitasking. Multitasking was once thought of as a way to get many things done at once, but it’s now understood as a way to do many things poorly. As science shows us, despite the brain’s remarkable complexity and power, there’s a bottleneck in information processing when it tries to perform two distinct tasks at once. Not only is this bad for the brain; it’s bad for the team. Managers should set a firm policy that multitasking is unacceptable, as it’s important for everyone to be mentally present.

Here are three ways to make sure the ban on multitasking is followed:

Use video: It can essentially eliminate multitasking, because your colleagues can see you.

Have the meeting leader call on people to share their thoughts. Since no one likes to be caught off-guard, they’ll be more apt to pay attention.

Give people different tasks in the meeting, rotated regularly. To keep people engaged, have a different team member keep the minutes of the meeting; track action items, owners and deadlines; and even come up with a fun question to ask everyone at the conclusion of the meeting.

Nick Morgan, president of consulting company Public Words Inc., recommends constant touchpoints: “In a virtual meeting, you need to stop regularly to take everyone’s temperature. And I do mean everyone. Go right around the list, asking each locale or person for input.”

Assign a Yoda. Candor is difficult even for co-located teams, but it’s the number one gauge of team productivity. To keep people engaged during virtual meetings, appoint a “Yoda.” Like the wise Jedi master in Star Wars, the Yoda keeps team members in line and makes sure everyone stays active and on topic. The Yoda keeps honesty from boiling over into disrespect by being courageous and calling out any inappropriate behaviors. At critical points during the meeting, the leader should turn to the Yoda and ask, “So, what’s going on here that nobody’s talking about?” This allows the Yoda to express the candor of the group and encourage risk-taking.

After the meeting:

Formalize the water cooler. Have you ever been in a meeting, and just when it ends, everybody walks out and vents their frustrations next to the water cooler? Make the water cooler conversation the formal ending of the virtual meeting, instead. Five to 10 minutes before the meeting ends, do what everybody would’ve done after the physical meeting – but do it in the meeting and make sure it’s transparent and conscious, processing people’s real feelings.

How? Have everyone go around and say what they would’ve done differently in the meeting. This is like the final “Yoda” moment – it’s the “speak now or forever hold your peace” moment. This is the time when you say what you disagreed with, what you’re challenged with, what you’re concerned about, what you didn’t like, etc. All of the water-cooler-type conversation happens right now, or it never happens again. And if does happen later, you’re violating the ethics of the team.

Most importantly in virtual meetings, civility and respect must be the norm. There have to be inalienable, ethical rules that you follow before, during and after a virtual meeting for it to be truly successful. And that means adhering to two fundamental principles: Be respectful of others’ time, and be present. Failing to do so steals precious hours from the team that can never be recovered. Co-located teams have enough problems building candor and trust; teams separated by distance really need to have great meetings to build these connections.

Want to help with our research? Please take this survey so we can see how many companies are using these practices.

[image error]

The Sales Director Who Turned Work into a Fantasy Sports Competition

Now that everything we do at work can be observed, measured, tracked, and reported — thanks to sensing technologies and cheap processing power — more organizations are relying heavily on “the data” to manage employees’ performance. They’re striving to assess people strictly on merit: how productive they are, how well they collaborate, how much value they create.

As human beings, we’re naturally biased in how we perceive others’ competence and worth. Analytics can help correct that problem, but sometimes even the data doesn’t seem fair. When we feel it doesn’t sufficiently account for our contributions, we lose confidence in it, feeling trapped by its failure to “understand” us. So then we explain the metrics away rather than using them to learn what’s working and improve the things that aren’t.

How do we fix that? Sports organizations have taken some of the apparent bias out of talent analytics by incorporating several factors into performance assessment, synthesizing numerous observable metrics into one “uber” number. In baseball, we have Sabermetrics, a set of stats that measure in-game activity; in football, the Total QBR, which captures the quarterback’s various contributions; and in basketball, the PER (player efficiency rating), an all-in-one measure of individual productivity. Though each rating system has its limits, the idea is to prevent recruiters and managers from assigning too much significance to some factors and not enough to others.

But does creating one synthetic score to manage performance make sense in non-sports organizations, as well? David Schwall, a director who heads up inside sales at Clayton Homes (a Berkshire Hathaway company that builds homes in the United States), says it’s working there. He implemented it last year with an interesting twist.

Schwall was looking for a way to improve his unit’s performance. The operation was the epitome of transparency — via Salesforce CRM integration, leaderboards displayed the top reps’ progress. People were rewarded for sustained performance and paid an additional bonus for each of their leads who visited a retail store.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

Still, Schwall thought his team could achieve more. Eager to try something different, he partnered with Ambition, a Y Combinator start-up that has created a platform to turn sales teams’ work into a fantasy sports competition. In fantasy sports leagues, which attracted over 41 million Americans in 2014, participants create their own imaginary teams with actual players, scoring points according to how those players perform that season. In the summer of 2014, Schwall turned his managers into team owners, who then drafted all the reps in Clayton’s inside sales unit into five fantasy football teams. (The unit itself served as the “league.”) Individuals scored points against a single, synthetic “Ambition” score according to their sales performance in three critical areas — how many calls they made to high-potential leads, what percentage of those calls resulted in a confirmed appointment at one of about 1,000 retail stores, and what percentage of those individuals they subsequently transferred by phone to the proper local store (which improves the likelihood that a customer will show up for his or her appointment). Different teams went head to head each week; the top four faced off in the championships.

Clayton essentially added what University of Pennsylvania professors Ethan Mollick and Nancy Rothbard would call a “game layer” to the work, altering how employees experience work and how managers evaluate it, even though the tasks have remained the same. (Note how that differs from job design, which changes the nature of the work — the workflow, the processes, and so on.) Of course, “gamification” has gone in and out of style many times over the past decade, since giving work a veneer of fun doesn’t always lead to better results. And even where performance does improve, the superficiality of the game layer often makes such improvements unsustainable.

But counter to expectations, Schwall’s organization experienced stunning productivity improvements for sustained periods of time. The league is between seasons now, but in the last, the inside sales team (which now handles 30,000 leads per month) saw an 18% spike in outbound calls, doubled the percentage of calls that resulted in an appointment, and increased the number of transferred calls eightfold. Overall, visits to retail stores tracked back to referrals by the inside sales team are now up over 200%.

What led to those striking results? Sure, the job at hand felt more social and interactive, which can have a positive effect on collaboration, productivity, creativity, and other aspects of performance. But those productivity increases suggest that something more is going on. We spoke with a number of employees who have participated in the fantasy league. As expected, they liked that the system seemed fair and kept them engaged: Scores were recorded in real time and calculated based on meaningful factors, and everyone (employees and managers) could see the same data. But there were also a couple of more-surprising discoveries.

The fantasy sports context helped alleviate the costs of transparency. While radical transparency about performance at work can feel invasive or dehumanizing, shifting the context to fantasy sports made people more comfortable with basing perceptions of competence and status on the cold, hard numbers. As one employee explained to us, “I’m used to seeing scores in sports, so I guess I didn’t really mind being publicly scored in Ambition.”

People really got into the game — but because it was set up like a sports league, they also maintained a level of sportsmanship. (Contrast that with the famous Robbers Cave experiments, where teams were vying for more-limited resources, and in-group/out-group effects spun out of control.) Peers made sure there was no cheating by others. In just one case, an employee tried to fake her numbers, but she was found out quickly in the transparent, peer-patrolled system, which put an immediate stop to the behavior. While many engaged in banter on the “Trash Talk” feed, which received hundreds of posts, they self-policed to keep it focused and appropriate.

Some employees checked scores and rankings every 5-10 minutes. That might have been unproductive if focused effort hadn’t increased dramatically, too. During the championships, many employees stayed late or came in on the weekend to put in a little extra “playing” time. One commented, “When I saw one of my colleagues leaving, I thought — ‘Yes, now I can catch up and climb above him in the ranks!’” Even with all the competition, employees consistently said that they were most often competing with themselves, trying to beat their own personal records (which were also tracked by the system).

Sales became more of a team effort. Before the fantasy football experiment, the sales reps had focused almost exclusively on their own tasks and outcomes. But when they created the imaginary teams, they began to reap many of the benefits associated with teams without actually engaging in interdependent work. Reps coached each other on how to do their tasks better; they celebrated each other’s rankings; and they held each other accountable. Commitment to the team score prevented a free-rider effect — individuals didn’t stop trying when they hit their own personal targets. They felt bad if they were dragging down the team and sought advice from teammates who exceled where they needed help.

Managers started seeing themselves as coaches, too, offering people guidance on what they could each do to help the team’s performance. Because scores were calculated based on a set of metrics, not just one, managers could spot where individuals were strong or weak and either provide mentoring or take a divide-and-conquer approach to the work.

The league also struck a balance between shaming the worst performers and celebrating the best. TVs publicly displayed the top scores and played individuals’ theme songs when people reached milestones. But there was no public view of the worst performers’ scores. Those were visible only within teams, so members could support those who were struggling.

So it wasn’t just “gamification” that changed how people experienced the work; it was “teamification,” as well. The employees we interviewed kept emphasizing the social aspect — they said it was key to creating the peer-to-peer accountability that they felt drove the increase in productivity. As one person said, “It wasn’t just about carrot-and-stick motivation (like traditional leaderboards), but rather about prolonged discipline.” In other words, employees saw this as a feedback tool for themselves, not as a “big brother” tool for their managers.

Of course, some people weren’t so fond of this approach to performance management. Particularly in the beginning, those who had thrived in the previous system — for instance, those who simply made a lot of calls — weren’t thrilled with the multimetric scoring, which allowed others to challenge their consistently high rankings. Less-experienced reps could now find at least one metric on which to successfully compete, and that leveled the playing field quite a bit.

On the whole, the data felt eminently fair in this system, so people were receptive to what it told them about their performance. At the end of the interviews, most of them said they couldn’t wait for another season to begin — they missed the immediate feedback, recognition, and energy. Seems like a good sign for sustainable improvement, but time will tell.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers