Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1309

March 16, 2015

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the April 2015 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the April issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“Now we’d like to ask the audience to name an organ to be removed.”

Bob Eckstein

“Did you see a cocktail napkin with our entire marketing campaign on it?”

Andrew Grossman

“I beat the snail. I blew out the sloth. But all anyone remembers is that damn tortoise.”

Patrick Hardin

And congratulations to our April caption contest winner, Robert Rak of Bridgewater, New Jersey. Here’s the winning caption:

“Innovation may not be a core competency at Franklin Electric.”

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by April 7.

Cartoonists: Elizabeth Westley and Steven Mach

[image error]

Engage Your Long-Time Employees to Improve Performance

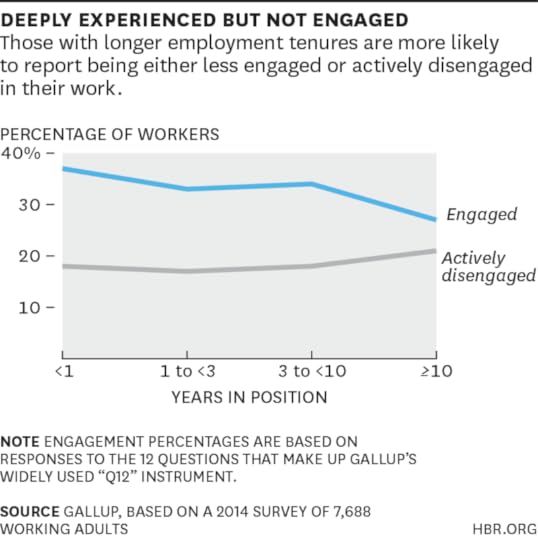

Let this be a wake-up call for business leaders: The employees with the longest tenures in your company are also the least likely to be engaged.

Somewhere along the way, most workers lose some of their motivation to make a difference and create value for their employers. Many grow apathetic over time and spend each day doing the minimum to get by. Some nurse grudges for years and even undermine the company when they get the chance.

It might be tempting to say this is their problem, but in fact it’s yours. In today’s knowledge-based economy, companies and products are intricately specialized and experience counts for a lot. Retaining long-tenured, highly capable employees might be challenging, but minimizing their turnover is more practical than churning through new hires who, even after costly training, might or might not turn out to be a fit for the complex requirements of a role.

More positively, the typical inverse relationship between tenure and engagement points to an important untapped opportunity for most organizations: the dramatic performance gains that can be made by thwarting it, and keeping long-tenured employees engaged.

Gallup’s data suggest that the highest performing individuals in companies have three things going for them: (1) they have tenures of a decade or more in their organizations; (2) they are engaged in their work; and (3) they are in roles where the expectations of the job align well their natural talents. Each variable affects outcomes on its own, but the highest performance comes from the combination.

But here’s the unfortunate fact: in the typical company among the hundreds we’ve studied, this combination exists in just 5% of individual contributors.

Tenure matters not only because years of work in a given profession yield deep specialist knowledge. Those years also cultivate a nuanced understanding of how a company operates and how to maneuver through organizational channels and get things done with a minimum of friction. Through countless hours of collaboration with the same coworkers and teams, veteran employees gain tacit knowledge that allows them to predict how colleagues will behave and anticipate how they will respond to everyday situations. This sort of in-depth knowledge is immensely useful to employers, but prospective employees can’t obtain it in business school or replicate it by working in a similar company or role.

Indeed, numerous academic studies have found that individuals with longer organizational tenures tend to achieve higher levels of performance. Their improvement trajectory, likely a mix of their growing capabilities and the growing importance of the jobs they hold, might become less steep over time, yet it continues upward year after year. Experience is such a strong driver of performance that it allows long-tenured employees to outperform the average even despite being less engaged than their colleagues. Still, to count on tenure alone to deliver competitive levels of performance would be folly.

Engagement also makes a big difference. Gallup gathered the evidence that this is true in the course of working with hundreds of organizations trying to increase their employees’ engagement. The effect is pronounced even in employees of under two year’s tenure – perhaps because greater engagement makes them more likely to interpret and use their early experiences productively. The effect of engagement on performance continues throughout the employee life cycle to employees of long-term tenures (10 years or more).

What kind of managerial interventions can increase engagement? Here’s a strong hint. Our past research shows clearly that employees have the best chance of being engaged (and staying with their companies) when they also report that their managers understand them and give them the chance to do what they do best every day. Managers can help employees find ways to do more of what they’re good at.

This brings us to the question of natural talents, and the importance of matching people well with roles. Success starts with hiring employees with the right talents for jobs in the first place – or failing that, being quick to reposition them in jobs that fit them better. Perhaps not surprisingly, people’s natural talents matter a great deal to how well they do their jobs. This shows up in hard data: of tenure, engagement and talent, Gallup finds the latter to be the strongest predictor of performance.

To put a finer point on that, our analysis shows that talented employees with longer tenures in their jobs can achieve above-average performance even in work environments that are not very engaging. Alternatively, talented and engaged employees can achieve above-average performance even with less than two years of tenure. The effect of talent is only minimized to below-average performance when a talented person has less than ten years of tenure and is actively disengaged at work.

To understand the combined effect of tenure, engagement and talent on performance, my colleagues and I launched a large-scale study. This study included recent data from 20 studies across seven organizations and more than 7,000 individual contributors in various roles, including customer service, call centers, financial consultants, sales representatives, nurses, support staff and clinical staff.

Our finding that just 5% of employees are in the proverbial “sweet spot” — engaged at work, in roles that are the right fit for them and at their company for 10 years or more —likely indicates that few organizations are examining their workforce to understand where their people fit in this configuration. Yet our results suggest there’s much they can gain by doing so.

Employees who hit the trifecta of tenure, engagement, and talent perform 18% higher than the average employee and 35% higher than a worker who goes zero for three. For skilled, production, and support staff, this equates to a financial impact of $6 million and $12 million, respectively, per 1,000 employees. For highly educated professionals, the economic impact essentially doubles from $12 to $23 million per 1,000 workers.

In many companies, it may seem unrealistic to have a surplus of workers with ten or more years of tenure. Even among workers who have less tenure and are engaged and highly talented for their role, their performance is 9 percent better than average and 24 percent higher than someone with low talent who is actively disengaged.

The most important thing that companies must do to get the most from their workforce is to align their talent, engagement and tenure strategies. Using scientific predictive analytics to hire people with the right talents for their role gives them a better shot at becoming engaged because they have more opportunity to do what they do best. And pairing talented employees with great managers helps to boost and sustain engagement, increasing the likelihood of retention. This leads to a longer, more meaningful tenure for employees and, ultimately, a more productive and valuable workforce poised to support high organizational performance. The three parts of the configuration inherently support one another. Organizations need to combine them in a more strategic way.

[image error]

Your Late-Night Emails Are Hurting Your Team

Around 11 p.m. one night, you realize there’s a key step your team needs to take on a current project. So, you dash off an email to the team members while you’re thinking about it.

No time like the present, right?

Wrong. As a productivity trainer specializing in attention management, I’ve seen over the past decade how after-hours emails speed up corporate cultures — and that, in turn, chips away at creativity, innovation, and true productivity.

If this is a common behavior for you, you’re missing the opportunity to get some distance from work — distance that’s critical to the fresh perspective you need as the leader. And, when the boss is working, the team feels like they should be working.

Think about the message you’d like to send. Do you intend for your staff to reply to you immediately? Or are you just sending the email because you’re thinking about it at the moment, and want to get it done before you forget? If it’s the former, you’re intentionally chaining your employees to the office 24/7. If it’s the latter, you’re unintentionally chaining your employees to the office 24/7. And this isn’t good for you, your employees, or your company culture. Being connected in off-hours during busy times is the sign of a high-performer. Never disconnecting is a sign of a workaholic. And there is a difference.

Regardless of your intent, I’ve found through my experience with hundreds of companies that there are two reasons late-night email habits spread from the boss to her team:

Ambition. If the boss is emailing late at night or on weekends, most employees think a late night response is required — or that they’ll impress you if they respond immediately. Even if just a couple of your employees share this belief, it could spread through your whole team. A casual mention in a meeting, “When we were emailing last night…” is all it takes. After all, everyone is looking for an edge in their career.

Attention. There are lots of people who have no intention of “working” when they aren’t at work. But they have poor attention management skills. They’re so accustomed to multitasking, and so used to constant distractions, that regardless of what else they’re doing, they find their fingers mindlessly tapping the icons on their smartphones that connect them to their emails, texts, and social media. Your late-night communication feeds that bad habit.

Being “always on” hurts results. When employees are constantly monitoring their email after work hours — whether this is due to a fear of missing something from you, or because they are addicted to their devices — they are missing out on essential down time that brains need. Experiments have shown that to deliver our best at work, we require downtime. Time away produces new ideas and fresh insights. But your employees can never disconnect when they’re always reaching for their devices to see if you’ve emailed. Creativity, inspiration, and motivation are your competitive advantage, but they are also depletable resources that need to be recharged. Incidentally, this is also true for you, so it’s worthwhile to examine your own communication habits.

Company leaders can help unhealthy assumptions about email and other communication from taking root.

Be clear about expectations for email and other communications, and set up policies to support a healthy culture that recognizes and values single-tasking, focus, and downtime. Vynamic, a successful healthcare consultancy in Philadelphia, created a policy it calls “zmail,” where email is discouraged between 10pm and 7am during the week, and all day on weekends. The policy doesn’t prevent work during these times, nor does it prohibit communication. If an after-hours message seems necessary, the staff is compelled to assess whether it’s important enough to require a phone call. If employees choose to work during off-hours, zmail discourages them from putting their habits onto others by sending emails during this time; they simply save the messages as drafts to be manually sent later, or they program their email client to automatically send the messages during work hours. This policy creates alignment between the stated belief that downtime is important, and the behaviors of the staff that contribute to the culture.

Also, take a hard look at the attitudes of leaders regarding an always-on work environment. The (often unconscious) belief that more work equals more success is difficult to overcome, but the truth is that this is neither beneficial nor sustainable. Long work hours actually decrease both productivity and engagement. I’ve seen that often, leaders believe theoretically in downtime, but they also want to keep company objectives moving forward — which seems like it requires constant communication.

A frantic environment that includes answering emails at all hours doesn’t make your staff more productive. It just makes them busy and distracted. You base your staff hiring decisions on their knowledge, experience, and unique talents, not how many tasks they can seemingly do at once, or how many emails they can answer in a day.

So, demonstrate and encourage an environment where employees can actually apply that brain power in a meaningful way:

Ditch the phrase “time management” for the more relevant “attention management,” and make training on this crucial skill part of your staff development plan.

Refrain from after-hours communication.

Model and discuss the benefits of presence, by putting away your devices when speaking with your staff, and implementing a “no device” policy in meetings to promote single-tasking and full engagement.

Discourage an always-on environment of distraction that inhibits creative flow by emphasizing the importance of focus, balancing an open floor plan with plenty of quiet spaces, and creating part-time remote work options for high concentration roles, tasks, and projects.

These behaviors will contribute to a higher quality output from yourself and your staff, and a more productive corporate culture.

[image error]

Introverts, Extroverts, and the Complexities of Team Dynamics

Let’s start with a short personality test. For each of the following dimensions, indicate the extent to which each of the following words describes you, with a 5 indicating “very much so” and a 1 indicating “not at all”: assertive, talkative, bold, not reserved, and energetic. Now sum up your scores. What’s the total?

If you scored under 10 points, you are likely to have an introverted personality rather than an extroverted one. If that is the case, you are certainly not alone. Studies find that introverts make up one-third to one-half of the population. Yet most workplaces are set up exclusively with extroverts in mind, a fact that becomes clear when you look at traits associated with the two personality types.

Extroverts gravitate toward groups and constant action, and they tend to think out loud. They are energized and recharged by external stimuli, such as personal interactions, social gatherings, and shared ideas. Being around other people gives them energy. In contrast, introverts typically dislike noise, interruptions, and big group settings. They instead tend to prefer quiet solitude, time to think before speaking (or acting), and building relationships and trust one-on-one. Introverts recharge with reflection, deep dives into their inner landscape to research ideas, and focus deeply on work.

What do these tendencies mean for the ability of extroverts and introverts to succeed in team settings, where they must interact and sometimes lead others? My research suggests that the answer depends on the types of team members being led.

Team leaders who are extroverted can be highly effective leaders when the members of their team are dutiful followers looking for guidance from above. Extroverts bring the vision, assertiveness, energy, and networks necessary to give them direction.

By contrast, when team members are proactive — and take the initiative to introduce changes, champion new visions, and promote better strategies — it is introverted leaders who have the advantage. Extroverted leaders are more likely to feel threatened, I’ve found. When employees champion new visions, strategies, and work processes, they often steal the spotlight, challenging leaders’ dominance, authority, and status. As a result, extroverted leaders tend to be less receptive: They shoot down suggestions and discourage employees from contributing. By comparison, an introverted leader might be comfortable listening and carefully considering suggestions from below. This finding is consistent with a wealth of research on what is known as dominance complementarity: the tendency of groups to be more cohesive and effective when they have a balance of dominant and submissive members.

Further Reading

Running Meetings (20-Minute Manager Series)

Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

The intuition here is that extroverted leadership may drive higher performance when employees are passive but lower performance when employees are proactive. To test this idea, my colleagues Adam Grant of Wharton, Dave Hofmann of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and I studied a U.S. pizza-delivery chain. Since the stores in the chain were highly similar, they offered a natural opportunity to track whether their success varied as a function of extroverted leadership and employee proactivity.

With the goal of isolating the influence of extroverted leadership, we compared the profitability of 57 different stores. We assessed each store leader’s levels of extraversion — how assertive, talkative, bold, and energetic he or she was. In addition, an average of six to seven employees per store completed surveys about how proactive their store was as a group: to what extent did they voice suggestions for improvement, attempt to influence the store’s strategy, and create better work processes?

Then, for the following seven weeks, we tracked each store’s profits. We statistically adjusted for factors beyond the leader’s control, such as the average price of pizza orders and the total number of employee labor hours. We found that extroverted leadership was linked to significantly higher store profits when employees were passive but significantly lower store profits when employees were proactive. In stores with passive employees, those led by extroverts achieved 16% higher profits than those led by introverts. However, in stores with proactive employees, those led by extroverts achieved 14% lower profits. As expected, extroverted leadership was an advantage with passive groups, but a disadvantage with proactive groups.

These results suggest that introverts can use their strengths to bring out the best in others. Yet introverts’ strengths are often locked up because of the way work is structured. Take meetings. In a culture where the typical meeting resembles a competition for loudest and most talkative, where the workspace is open and desks are practically touching, and where high levels of confidence, charisma, and sociability are the gold standard, introverts often feel they have to adjust who they are to “pass.” But they do so at a price, one that has ramifications for the company as well.

How can you get the best from deep, quiet team members during meetings? A look at practices used in some organizations points to an answer. At Amazon, every meeting begins in total silence. Before any conversation can occur, everyone must quietly read a six-page memo about the meeting’s agenda for 20 to 30 minutes. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos instituted this process after recognizing that employees rarely read meeting materials sent in advance. Reading together focuses everyone’s attention on the issues at hand.

The real magic happens before the meeting ever starts, when the author is writing one of these six-page memos, which are called “narratives.” The memos must tell a story: They have a conflict to resolve and should conclude with solutions, innovation, and happy customers — a structure that provides the meeting with direction. Writing forces memo authors to reason through what they want to present, spend time puzzling through tough questions, and formulate clear, if not persuasive, arguments. It’s no surprise that Bezos also banned PowerPoint presentations in meetings, thus doing away with simplistic and fuzzy bullet-point logic.

The type of clear thinking that these structured memos require also serves the purpose of leveling the playing field for team members who differ in their level of introversion and extroversion. The imposition of writing as a medium turns self-discipline and personal reflection into effective meetings and participative decision making. After devoting time to reading, the group can then focus on engaging in a valuable discourse: reaching shared understandings, digging deeper into data and insights, and perhaps most importantly, having a meaningful debate. The process gives introverted team members the time they need to formulate their thoughts and, for some, build up the courage to share them with the rest of the team. It also encourages the extroverted to listen, reflect, and become more open to the perspectives of their more silent peers.

Thinking more carefully about how to structure meetings can be very helpful to make sure they produce good outcomes. And it can also assure management can get the best out of the introverted members, in addition to the more extroverted ones.

[image error]

Stop Noise from Ruining Your Open Office

A beautifully designed office can be a useful factor in recruiting and retaining talent. Today’s brand-new workplaces may contain officeless offices, cubeless cubelands, and collaborative spaces only surrounded by glass walls. These workspaces certainly look unique and make a strong statement about company culture, especially to prospective employees walking through the door for an interview.

These open offices do offer important benefits. Natural light matters: research by Mirjam Muench has found that those work under artificial light become sleepier earlier than those who work in natural light. Studies of people with and without views of nature – as opposed to either no views, or views of built environments – have found that a view of nature makes workers less frustrated, more patient, more productive, and physically healthier. All those open floor plans and glass walls help both light and views filter through to the entire office, and there’s often a bottom-line benefit as well: open floor plans are often less expensive (on an employee-per-square-foot basis) than assigned cubes and individual, private offices.

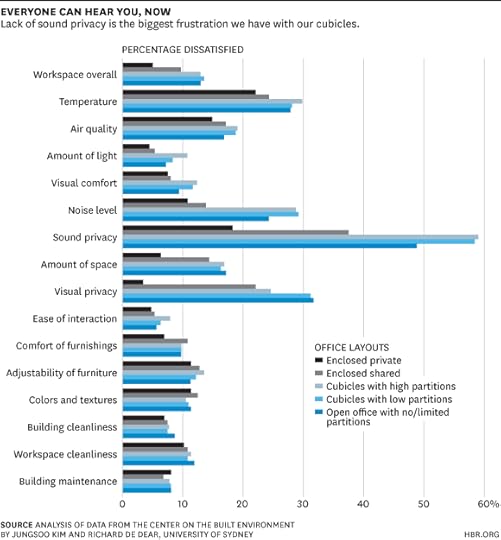

But an open office has downsides. A 2013 study from the University of Sydney found that a lack of sound privacy was far and away the biggest drain on employee morale:

Further, a 2014 study by Steelcase and Ipsos found that workers lost as much as 86 minutes per day due to noise distractions. Almost any office worker could share a story or two about annoying, loud, or obnoxious distractions – whether it be a coworker, a loud printer, a noisy heating and air conditioning system, or the ring of a cell phone.

Is it possible to have a gorgeous, open office and maintain peace and quiet, too?

We have found that there are several things businesses can do to reduce unwanted noise:

1. Provide dedicated quiet spaces. Similar to a quiet car on a train, businesses can use an empty office or unused conference room and turn it into a “Quiet Room” that employees can go to when trying to focus on an important task or project. These spaces are designated for non-group work and can help provide a place for workers to be more productive than at a shared desk or in a cubeless office.

2. Provide loud spaces, too. In contrast, businesses can also designate areas around the office that encourage interaction and discussion. Lunch areas, game rooms or even phone rooms can help communicate to employees that when working at their desks, those are the times to be quieter, but should you want to partake in a heated debate, feel free to go chat in the game room. Providing small enclaves containing telephones can encourage employees to make phone calls without disturbing their cubemates. There’s even an acoustic telephone booth that could be added to an office to be used for private phone calls.

3. Mask the sound by increasing background noise. It seems counter-intuitive, but adding more sound to an environment can actually make it seem quieter. Research suggests that noise itself isn’t distracting, but unwanted speech noise is. However, words that are incomprehensible are less likely to be distracting. By adding a continuous, low-level ambient sound to an environment (such as white noise, which sounds similar to the sound of airflow), sound masking can help make conversations for listeners that aren’t intended to hear them unintelligible, and therefore much easier to ignore.

4. Bring in sound absorbing materials without sacrificing design. For the organization that has a severe noise problem (think call centers or co-working spaces that are becoming very popular among entrepreneurs and startups), there are a few surprising and stylish fixes that can be installed to reduce sound.

Although trendy, open offices in renovated warehouses can be a nightmare when it comes to sound traveling across the space. Hard surfaces do a poor job at absorbing sound, so bringing in softer materials such as carpets can help minimize noise. Cubicle partitions and standard white acoustical ceiling titles are the most common ways to block and absorb sound, but they typically don’t evoke beautiful, modern design. Those with the budgets to get more creative can consider drop ceilings that soak up sound and incorporate shapes, colors, and designs. Walls can even be decorated with pieces that double as both high-quality soundproofing materials and unique pieces of art. Unfortunately these materials can often come with hefty price tags, but can be worth the investment for offices with major sound problems and employees who care about design.

Looking for a more natural option? Similar to planting trees along a loud highway, plants boast sound absorbing capabilities that can work just as effectively in an indoor environment as an outdoor setting. Furthermore, plants have other significant health benefits, including improving oxygen levels in an office.

If your company hasn’t decided to pursue any of these solutions, there are a few solutions you can try as an individual:

1. Speak up. If you’re finding that a poorly placed printer or loud officemates are causing too many distractions and interrupting your work, alert an office manager or human resources director of the issue. Oftentimes with bigger offices, someone farther removed from the source of distraction may not be aware of the productivity issues being caused. How can you as an employee help solve this problem? Form a coalition with other employees to help brainstorm solutions. An employee-driven initiative could generate more interest and ensure fellow coworkers would follow employee-implemented rules regarding noise levels.

2. Use an indicator. Should you find you are constantly being interrupted by coworkers, determining some sort of public signal that you are not to be interrupted might limit distractions. If you don’t have an office door to close, consider putting up a humorous sign or special figurine on top of your desk (both noticeable visuals) when you don’t want to be disturbed. Don’t even have a desk? A company called Luxafor makes a USB light that clips onto your laptop screen and changes colors to signal your availability.

3. Wear headphones. While wearing headphones at the office isn’t always appropriate, a pair of large headphones can sometimes serve as an obvious indicator that you’d prefer not to be disturbed and help you be more productive. Large, over-the-ear headphones often help block out unwanted noise better than earbuds. This is again particularly useful for open offices in which shutting a door to block out interruptions is impossible. And to put this back on the company’s plate, should your company have an open office layout, giving new employees a pair of nice headphones on their first day of work may be both an amusing, and useful, welcome gift.

[image error]

March 13, 2015

What Everyone Needs to Know About Running Productive Meetings

Raise your hand if you think the majority of meetings are a complete waste of your time — not to mention your organization’s time. You don’t need to look far for confirming evidence. Consider the data on how one company’s weekly executive committee meeting rippled through the organization in a profoundly disturbing way, ultimately taking up to 300,000 hours a year.

We could all use some of that time back. But, what can we do about the seemingly endless cycle of meetings that we’re all caught up in? I reached into HBR’s archives to find some of our best advice on meetings — how to have fewer of them, and how to make the ones we must have more productive. Here’s a summary of what I found:

Further Reading

Running Meetings (20-Minute Manager Series)

Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

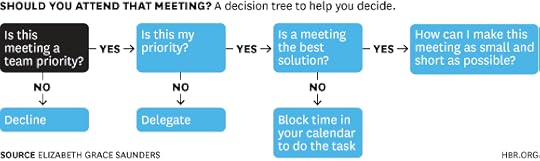

The best place to start is to address your, and everybody else’s, addiction to meetings. Many of us fall into the trap of attending a lot of meetings because it makes us feel important. But before you accept that next invitation, ask yourself: “If I was sick on the day of this meeting, would it need to be rescheduled?” If the answer is “no,” you probably don’t need to be there. When in doubt, follow this handy decision tree from author and time coach Elizabeth Grace Saunders:

If you truly can’t attend fewer meetings, try to at least reduce their length — instead of 60 minutes, start with 30, or even 15, and set a goal to finish early. Or, try to schedule your part of the discussion for the beginning of the allotted time, then excuse yourself from the rest of the meeting. This is especially important for conference calls — there is no reason that all attendees should be on the call from start to finish. All it takes is a little advance planning around which topics will be discussed when. When you consider what people are actually doing on conference calls, it’s worth the upfront time and effort:

There are, of course, times when meetings are necessary. These are the three reasons that warrant a face-to-face get-together:

To inform and bring people up to speed.

To seek input from people.

To ask for approval.

Don’t schedule a meeting for something that can be addressed in a phone call, and don’t make a phone call for something that can be communicated via e-mail. If you need to schedule a meeting to accomplish your goal, challenge yourself to make it quick and efficient, and keep these best practices in mind:

Start with a focused agenda. At HBR, many of us follow this rule: No agenda, no meeting. A well-executed agenda sets the tone and direction for a productive meeting. Speak with colleagues informally ahead of time to determine the most important discussion items. Be as specific as you can, and include a timeline that allocates a certain number of minutes to each item (then, be sure to stick to it during your meeting). Send the agenda to people in advance, so they have time to prepare for the meeting.

Limit attendees. When you’re scheduling a meeting, start by asking yourself what the priorities are, and who absolutely needs to be there. It’s important to control the size of your meeting and to have key decision makers in the room. (Don’t fall into the trap of sending out blanket invites just because online calendars, scheduling apps, and email distribution lists make it easy to do so.) If you need an important senior manager at a meeting, confirm the best time with that person first, and then schedule everyone else around it. And it should go without saying that if you’re holding a client meeting, always put the client’s calendar first.

Keep it on track. Once you have the critical players assembled, keep your meeting from getting derailed. This starts when you send out the agenda and any background materials. If people are logging on for a video conference, it’s imperative that you’re well-trained and comfortable using the tool’s features. If you’re not, be sure to bring someone who is; you don’t want to waste the first 20 minutes figuring out how to work the audio or the webcam.

Manage attendees. No matter how well-defined your agenda is, there will always be behind-the-scenes dynamics that can throw your meeting off track. After all, everyone comes with his or her own goals and those can influence the tone and direction of the meeting. Some will be highly engaged in the topic at hand, while others are there just because it was on their calendar. It’s up to you to be a steward of all the ideas in the room, striking the right balance between encouraging all voices to speak up and be heard, listening, and not letting people go off on tangents.

Set the right tone. Be cognizant of what your body language is communicating to people — how we say things is just as important as what we’re saying. For example, notice whether your pose is attentive or whether you’re leaning back with your arms folded, which can indicate impatience or withdrawn skepticism. If you’re shifting in your chair, drumming your fingers, doodling, gazing out the window, or looking at your phone, then you can be pretty sure that people will think that you’re not interested in what they have to say. Body language is especially important when you’re the boss, because everyone else will be following every arch of your eyebrow.

Define next steps and responsibilities. Never end a meeting without defining next steps, deadlines, and individual responsibilities. Keep a record of who’s responsible for what — and by when. If the meeting uncovered items that need to be further explored, set up a time for a follow-up discussion.

Of course, certain types of meetings require more strategic planning and execution, for example:

Teleconferences: Teleconferences can be a huge time suck. But, when conducted well, they can be even more productive than face-to-face meetings because they are a quick, easy, and relatively cheap way to bring people together. They also lend themselves well to being recorded, and it’s easy to patch people in and out as needed. Here’s how to make your next teleconference more productive.

Off-site meetings: Most management teams set aside a day to a week every year to get out of the office and do strategic planning. But too often, planners and participants assume that the off-site is just another meeting in another location. It’s really not, and needs to be approached very differently. Here’s how to make the most of an off-site meeting.

Leadership summits: Many large and midsize companies bring leaders together for a summit once a year. But too many squander this rare opportunity to harness the collective knowledge and energy of their top executives. Here’s how to make your next summit count.

Remember that the first — and most important — meeting you should be scheduling everyday is with yourself. Block off time on your calendar each morning to get clear on priorities and to focus on what absolutely needs to be done that day. No matter how many meetings you have on the calendar, this is the one that will position you and your team to make the most productive use of your time.

[image error]

Stop Distinguishing Between Execution and Strategy

It’s impossible to have a good strategy poorly executed. That’s because execution actually is strategy – trying to separate the two only leads to confusion.

Consider the recent article, “Why Strategy Execution Unravels — and What to Do About It“ by Donald Sull, Rebecca Homkes, and Charles Sull, in the March 2015 issue of HBR. Articles like this are well meaning and all set out to overcome the shortfalls of “execution.” But they all fail, including this one, and for the same reason: you can’t prescribe a fix for something that you can’t describe. And no one can describe “strategy execution” in a way that does not conflict with “strategy.”

Blaming poor execution for the failure of your “brilliant” strategy is a part of what I’ve termed “The Execution Trap” — how “brilliant” can your strategy really be if it wasn’t implementable?

And yet in virtually all writings about problems with “execution” the argument starts by positing that the problem with strategy is that it doesn’t get executed. That is, the authors create a clean logical distinction between “strategy” and “execution.” Then they go on to define “execution” as “strategy.”

To illustrate, “Why Execution Unravels“ defines execution as follows:

Strategy execution, as we define the term, consists of seizing opportunities that support the strategy while coordinating with other parts of the organization on an ongoing basis. When managers come up with creative solutions to unforeseen problems or run with unexpected opportunities, they are not undermining systematic implementation; they are demonstrating execution at its best.

The problem is that seizing unexpected opportunities is essentially strategy — not execution. In other words, “Why Execution Unravels” effectively argues that the problem with strategy execution is strategy, which, of course, contradicts the idea that strategy and execution are two separate things.

For me this produced a flashback to Larry Bossidy, Ram Charan, and Charles Burck’s book Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done, published back in 2002. After spending the first 21 pages explaining that “Most often today the difference between a company and its competitor is the ability to execute” and “Strategies most often fail because they aren’t executed well,” the authors provide this definition of “execution”:

The heart of execution lies in the three core processes: the people process, the strategy process, and the operations process. [Emphasis added]

This defines the whole of strategy as one of the three core pieces of execution! To the authors, execution is strategy mere pages after execution is completely different from strategy.

Execution writers fall into this trap because they want to make a distinction between strategy as deciding what to do and execution as doing the thing that strategists decided. But that begs the thorny question, especially in the modern knowledge economy, what exactly does that “doing” activity entail? If it is to be distinct from the antecedent activity of “deciding what to do,” then we pretty much have to eliminate the “deciding” part from “doing.” So to create the desired distinction, we would have to define execution as choice-less doing. There are no choices to be made: just do it (whatever “it” happens to be).

But most people, including the authors of the article and book above, would agree that “doing” clearly includes some “choosing.” So in the end, the only logic that can be supported by what really happens in organizations is that every person in the organization engages in the same activity: making choices under uncertainty and competition.

Calling some choices “strategy” and some “execution” is a fruitless distinction. In fact, it is worse than fruitless; it is the source of the observed problems with “execution.” So if organizations experience “bad execution” it is not because they are bad at the discipline of execution. It is because they call it execution.

[image error]

The Corporate HQ Is an Anachronism

Headquarters is typically where the senior-most leaders of an organization are based. The top floor of the HQ building is often reserved for such leaders, including the CEO and his or her lieutenants, and this is where decisions are made and disseminated, funds are allocated, and promotions are determined. The next rung of leaders who operate from different geographies or second-tier P&Ls often have to converge on this center of gravity for reviews and the occasional reprimand. The time has come for us to rethink this concentration of leadership.

Change today is exponential and calls for rapid information flows, quick decisions, and speedy responses to unforeseen events. Technology has compressed time, costs, and distance considerably. Given these shifts, organizations have to be agile, simple, and responsive. Once-a-year rituals like budgeting and strategic planning, which were important tasks for the senior-most leaders in the company, are a thing of the past. In a hyper-speed world with multiple divergences, a vertical chain of command with annual rituals creates isolation, sluggishness, and bureaucracy. Management attention needs to be real time and integrated into the everyday workings of the field.

The 21st century company should repurpose the role and placement of leaders. Leaders should be where the action is: where customers are and where decisions should be made. This way their understanding and appreciation of what is needed is multiplied and they become facilitators of action as it happens, not gatekeepers, reviewers, or controllers. By distributing leaders to these critical points, an organization can shape shift in accordance to the context and realities it has to deal with while they are happening. This is what is likely to make it more agile and responsive.

At GE, we have begun to use this approach to distributed leadership as a way of increasing our relevance to the marketplaces we serve or tap into. For instance, GE Oil & Gas used to be headquartered in Florence, Italy, but over the last few years, we have distributed the leaders of this business to places like Houston, London, and Aberdeen to take advantage of the presence of customers in these locations. A few years ago, for a similar reason, GE moved the base of its vice chairman, John Rice, to Asia. John’s move pulled a lot more leadership attention to the growth markets in that region. It allowed us to grow our presence from 100 countries in the world to over 175 countries now, which would not have been otherwise possible.

We have also applied the same concept to capabilities and have set up centers where there are proven talent pools. For instance, we opened the GE Software center of excellence in San Ramon, California, given the availability of talent and the need to firmly establish ourselves as a software company. Likewise, when our aviation business wanted to look for aerodynamics experts, it found them in Germany, which is where we have one of our core research centers.

In a networked world, the center of gravity is where the customers are, and leaders have to be part of that engagement. A leader is not someone who sits in judgment but is an active participant in the action, lending the necessary muscle on the ground. Consequently, where to position a leader is a strategic decision and should be determined by the place that will help the company achieve a competitive advantage.

[image error]

How to Get Your Team to Coach Each Other

No one grows as a leader without the support of other people. Effective peer-to-peer coaching can offer the encouragement people need to overcome the fear of starting something new. Peer coaches, like professional coaches, can also hold their “clients” accountable for moving in a new direction.

Setting up a peer-to-peer coaching network on the team you manage can accelerate your team’s learning. I’ve been providing peer-to-peer coaching opportunities for decades, in my Wharton courses and in all kinds of organizations, and most recently in a MOOC (massive open online course) I teach on Coursera called Better Leader, Richer Life. In this piece, I’ll explain how to set up a non-directive coaching peer coaching network, in the Socratic tradition (in which the client discovers solutions to problems via dialogue), as opposed to instructional, evaluative, and directive feedback (in which an expert coach solves the client’s problem). Through compassionate, caring inquiry, everyone can develop and improve their abilities through practice and reflection on what works (and what doesn’t).

Of course, it won’t absolve you of responsibility for making tough personnel decisions about pay and promotion and of everything else you must do with your authority. But there is a sense of camaraderie and good feeling that comes when you have positive impact as a coach on another person’s well-being, and peer coaches learn things about themselves both through the act of coaching others, and, of course, by receiving coaching themselves.

To construct a peer coaching network, start small. Set people up in trios or ask employees to find two other people so the three can take turns serving as both coach and client for each other: A coaches B, B coaches C, and C coaches A. Suggest each person start by discussing their goals. The more open we are about goals, the more we increase our commitment to them, and the more likely they’ll be realized.

It’s also useful to talk about how the triad will work together, establishing expectations, time to meet, and understanding each other’s interests, hopes, and fears. Clarify how each member will play the coach and client roles and suggest adjustments as needed. Encourage each person to gain a preliminary understanding of each other’s key relationships at work, at home, and in the community. But the most important ground rule is this: “You choose what you want to disclose.” Respect privacy and preferences for how much information members are willing to disclose.

Provide your team with some basic guidelines followed by most coaches. Ask your team to follow to these guidelines to get the most out of their peer-to-peer coaching relationships:

Show you care about helping your clients achieve their goals.

Share your experiences only to help the client feel accepted, not to focus on you.

Be as aware as possible of your own biases as a coach.

Stay in touch with the reality your client is facing — listen well.

Don’t hide your ignorance — ask questions, even ones you might think are dumb.

Encourage your client to get more help when needed, from all sources.

Try not to criticize your client’s ideas; usually it’s best to listen and offer alternatives.

Don’t promise more than you can deliver; this will decrease your credibility.

The heart of non-directive, or developmental, peer-to-peer coaching is asking useful questions. Many people fear change because it forces them into unknown territory, where things are unpredictable and unfamiliar. And yet there are predictable stages people go through when they undertake intentional change. Coaches help others to see and feel the need to create meaningful, sustainable change. Here are the stages and some of the key questions peer coaches can ask in helping clients face the challenges associated with each:

What’s the problem?

Simply identifying the need for change can be difficult, as many of us ignore information that disconfirms our current perceptions or threatens the status quo. Coaches can help identify blind spots by encouraging self-reflection about things that aren’t obvious to their clients. Asking these basic questions increases awareness:

As you think about your goals, what’s not working well in your life?

What are the consequences of this issue for you and the important people in your life?

What is the source of the need to change — is it in you or is it external?

Why bother?

Because we naturally tend towards continuing the status quo, if doing something new doesn’t feel urgent, it’s not likely to occur. Coaches can help raise urgency by asking questions such as these:

Looking ahead, what will happen if you don’t change?

What will happen if you do change?

What’s your decision?

The decision to change is a crucial moment because it marks the point when your mind shifts and you begin to see a different future. It is also a fragile point in planned change processes, fraught with temptations to revert to the way things have always been and with distractions away from the focused effort that’s required to do something new and make it stick. Coaches can help clients reach and move beyond this point by asking:

What have you decided to do differently and why?

What is the ideal outcome?

What are your new goals?

4: What steps exactly?

Good coaches ask clients to think out loud about what to do differently, how to overcome obstacles, and what skills or sources of support are needed. You can help your client discover specific ideas for how to better accomplish goals by asking:

What exactly will you do, and when will you do it?

How will you measure progress?

What stands in the way, and how will you overcome these barriers?

How will you generate needed support?

Are you really in?

Because commitment wanes without a sense of urgency, coaches should continually test for this. Coaches can ask:

What if this is harder than you think?

What are the first steps — and the next steps — you will take?

How will you maintain your sense of urgency?

How will you sustain it?

Encouragement at every small step builds momentum. As a coach you should provide frequent reinforcement and celebrate your clients’ successes to bolster confidence and help them avoid backsliding. The key questions here are:

What impact has your new behavior had on you and others?

What accomplishments are you proud of achieving?

Is there a smarter step that might help you build momentum?

How can I (as your coach) reinforce your commitment to action?

Getting good at both providing and receiving peer coaching requires some investment. Very few people are naturally gifted in this essential skill. But like any other skill, it can be learned – with practice. As the leader of your team, establishing a peer coaching network can empower your colleagues, expand their skill sets, enrich them personally and professionally, and ultimately help your organization. It’s free, it’s fun, and it’s rewarding.

[image error]

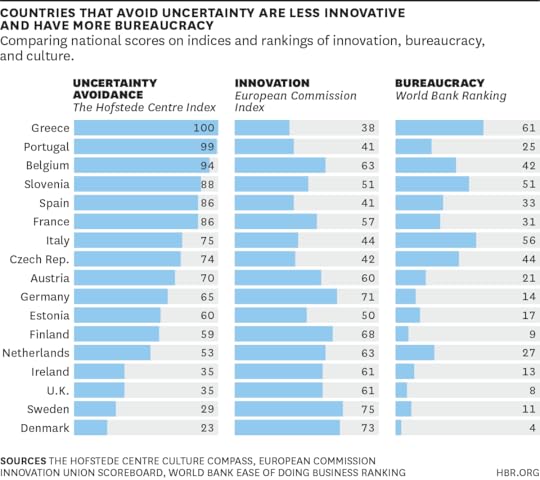

If Greece Embraces Uncertainty, Innovation Will Follow

No matter what happens with the Greek bailout, all parties agree that the Greek economy will have to become more competitive. Many politicians and commentators mention two critical factors in accomplishing this: increasing innovative capacity and reducing bureaucracy. Both are important, but they are far more difficult to achieve than many understand because they are, to a significant extent, influenced by culture.

“Culture” can sound like a catchall, a convenient way to place the blame outside the realm of policy, but I am talking about one specific dimension of culture: avoiding uncertainty.

Different societies deal differently with the fact that the future can never be known, and there is a well-known index to measure the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations. High uncertainty-avoidance cultures try to minimize the occurrence of unknown circumstances and proceed by implementing rules, laws, and regulations. In contrast, low uncertainty-avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or volatile environments, try to have as few rules as possible, and tend to be more tolerant of change.

The uncertainty-avoidance measure was originally created by Geert Hofstede through a cultural survey of more than 100,000 IBM employees around the world and subsequently confirmed in additional global surveys. The cultural dimensions identified by Hofstede have been used by more than a 1,000 academic studies.

Greece tops this index of uncertainty-avoidance across all countries, scoring 100 out of 100. Greeks’ high level of discomfort in ambiguous situations creates at least two effects. First, they are less likely to take risks – which means they are unlikely to invent new products, processes, or business models. This helps to explain why Greece has one of the lowest license and patent revenues from abroad as a percentage of its GDP, as well as one of the lowest contributions from high-tech product exports to its trade balance. Second, bureaucracy, laws, and rules exert particular influence in Greece because they help make life more structured and less uncertain. In Greece, acquiring construction permits, registering property, and enforcing contracts in courts require vast amounts of paperwork and time.

The data in the graph above demonstrate the link between innovation, bureaucracy, and uncertainty. Countries that score high on uncertainty avoidance score low on innovation (as measured in the innovation union scoreboard of the European Commission) and high on bureaucracy (as measured on the easiness to do business ranking of the World Bank). Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, the UK, and Finland all have low uncertainty avoidance, high innovation, and low bureaucracy. These countries have excellent research systems with a high number of influential scientific publications, relatively high levels of government and business R&D expenditure and venture capital financing, strong public-private collaborations, and a wealth of intellectual assets in patent applications and community trademarks. At the same time the citizens in these countries spend less time dealing with procedures to start a business, get electricity, register a property, pay taxes, enforce contracts in courts, and trade across borders. Their cultures’ comfort with uncertainty helps to make all of this possible.

This suggests that in addition to short-term policy changes, Greece needs a longer-term cultural shift. We Greeks must learn to accept and tolerate more risk and uncertainty about the future. And it all starts in school. We need to teach children to be courageous enough to take risks throughout their careers and to deal with the failures that unavoidably occur. To do this we must learn from the successes of other countries. Closer collaboration between schools, research institutes, and companies would enable the incubation of new ideas. Inventors’ competitions for young people held every few years could also stimulate new ideas and inspire a new generation of inventors and innovators. Mentorship of small companies by larger corporations and the public sector would also assist the training and professional growth of young entrepreneurs. Finally, the development of venture capital funds would provide the necessary financing for the development of new ideas since such ideas are typically too risky to receive bank financing.

Of course, in the near term, political stability and sound economic policies are necessary to avert crisis. But Greece cannot stop there. In the long term the goal must be broader: to create an economy built around innovation, one that embraces uncertainty.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers