Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1311

March 11, 2015

GM’s Stock Buyback Is Bad for America and the Company

General Motors’ announcement that it will settle a fight with activist shareholders by buying back $5 billion in stock over the coming year is a major loss for American taxpayers and GM’s workers. The investors’ leader, Harry J. Wilson, called the deal a ”win-win outcome.” But the only real wins are a victory for the hedge funds, and a Pyrrhic victory for GM in that it managed to keep Wilson off its board and reduced the size of the buyback from the $8 billion the investors had been demanding.

In 2009, Wilson was part of a Wall Street team that the Obama administration hired to structure the bailout of GM, after the company, once the world’s largest automobile producer, sustained over $88 billion in losses in the previous four years. During the bailout, financial firms, including hedge funds, were nowhere to be found. Instead, U.S. taxpayers put up $49.5 billion in rescue funding, and Canadian taxpayers pitched in another $10.9 billion, allowing GM to emerge from bankruptcy after just 40 days. In 2010 the “New GM” did one of the largest initial public offerings in history, with share sales to the public of $23.1 billion by the U.S. and Canadian governments as well as the United Automobile Workers (UAW) through its Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA) Trust. By the time the U.S. government sold off all of its GM holdings in December 2013, U.S. taxpayers had absorbed a $11.2 billion loss.

The UAW made big sacrifices, allowing GM to reduce labor costs by $11 billion. There were 21,000 layoffs; a wage freeze for current workers; a halved wage of $14 per hour for non-core new hires; elimination of a funding program for unemployed workers; a no-strike agreement until 2015; and the VEBA that shifted UAW retiree healthcare and pension benefits from GM to the UAW, saving the company $3 billion per year. (In early February, a day after she met with Wilson, Barra decided to grant 9,000 UAW workers as much as $2,400 each in extra profit-sharing bonuses that were over and above the amount stipulated in the union contract. But this “Barra bonus” totals only $115 million, a pittance compared with the $5 billion that GM will spend on the buyback.)

While the restructuring certainly helped GM return to profitability (its annual net income averaged $6.7 billion from 2010 through 2013), it would probably still be bankrupt but for the booming Chinese market. In 2013 GM produced 3 million cars in China, or 45% of its global car production; that was up from 1.1 million vehicles in 2008. Indeed, in 2013 GM produced only 12% of its passenger cars and 21% of its motor vehicles in the United States.

Going forward, GM will need all the financial resources it can muster to produce automobiles that buyers in diverse global markets want at prices that they are willing to pay. In an industry characterized by intense global competition and major technological challenges, GM cannot afford to be held hostage by hedge funds in the name of “maximizing shareholder value.”

One of us (Bill Lazonick) has been extremely critical of the kind of buybacks — open-market stock repurchases — that GM has pledged to undertake. Their only purpose is to give manipulative boosts to GM’s stock price. The winners will be public shareholders, including the hedge funds, who stand ready to gain by selling their GM shares. If U.S. corporate history of the past three decades is a guide, the $5 billion in buybacks won’t be the last. The pump-and-dump hedge funds will come back to GM’s buyback well year after year until the cash flow once again runs dry.

GM did $20.4 billion worth of buybacks from 1986 through 2002. If it had saved that money and earned a modest 2.5% on it, the company would have had $35 billion on hand when the financial crisis and Great Recession hit and probably would not have had to file for bankruptcy protection. As Bob Lutz, the veteran auto executive, said recently, stock buybacks are “always a harbinger of the next downturn…in almost all cases, you regret it later.”

So why is GM risking déjà vu all over again? Surely GM CEO Mary Barra understands the deadweight loss that stock buybacks pose for her company. She has been with GM since 1980 when, at the age of 18, she entered General Motors Institute to get an engineering degree. She must know that public shareholders, including the hedge funds, whose only relation to the company is to buy and sell outstanding shares, contribute nothing at all to the creation of high quality, low-cost vehicles. One would hope that Barra’s motivation in caving in to the hedge funds has nothing to do with her $10 million in stock awards waiting to vest.

Taxpayers and workers brought GM out of bankruptcy, yet it is the hedge funds that will reap the biggest rewards. Taxpayers and workers should demand that open-market repurchases by all companies be banned. Stock buybacks manipulate the stock market and leave most Americans worse off. In this case, it is clear that what is good for the hedge funds is bad for the United States.

[image error]

March 10, 2015

How to Manage Someone Who Can’t Handle Ambiguity

Joan, a senior executive I coached once, had many excellent leadership qualities. She was creative, hardworking, and extremely knowledgeable about her industry. But most people working with or for her also found her impossible to deal with.

Rigidly opinionated and prone to angry outbursts, she was constantly critical of everything and everyone and played vicious office politics. With Joan you were either for her or against her — there was no middle ground. She would only deal with the people she perceived as “good,” and lost no time in vilifying those she perceived to be “bad.” The consequence of this behavior was intense strife wherever she went.

After she got a very negative 360 feedback, Joan’s boss laid it on the line: she needed to change her behavior or there was no question of her getting the promotion she was expecting. At the same time, cognizant of Joan’s qualities and contributions to the success of the company, he arranged for me to support her as she worked on trying to change.

Many of us have come across a Joan, who is what psychologists would call bivalent, a person who splits the world into friends and enemies, seldom examining their own behavior and attitudes. The strategy is as old as human nature. Everywhere we go, we fall into interpreting the world in binary terms: good and bad, negative and positive, hero and villain, friend and foe, believers and unbelievers, love and hate, life and death, fantasy and reality, and so on.

Like most behavioral patterns, splitting originates in childhood. It is related to insecure or disrupted attachment behavior patterns. How the caregiver interacts with the child is the major factor in the child’s ability to subsequently form relationships effectively. If the child is exposed to strife and discord early in life, before he has learned to tolerate ambiguity, it is more likely that he will cope by categorizing people and situations as either all good or all bad.

Essentially, splitting is a failure to integrate the positive and negative qualities of one’s self and of others. People like Joan struggle to accept that they can have both positive and negative feelings about someone or something and splitting gives them clarity, of a sort. They are able to take a confusing mass of experience or information and divide it into meaningful categories. But the cognitive distortion brought on by viewing a multi-faceted complex world through a binary lens means that we are bound to miss out on essential details.

Coaching bivalent executives isn’t easy, whether you’re a professional coach or a manager trying to help them learn to interpret the world around them in a more productive way. They are resistant to interventions, quickly interpreting any attempt at behavioral change as an attack. You have to begin by helping them acknowledge that they don’t understand as much as they think they do about their own inner thoughts, beliefs, desires, and intentions — let alone anyone else’s. And it is extremely difficult to interpret other people’s desires and motives accurately unless you have some understanding of your own.

A good way to do this is to turn the lens of analysis onto the relationship you have with each other first. When something happens within your relationship, work together to explain what happened and why, exploring alternative interpretations and intentions from both points of view. This gives the person you’re coaching an opportunity to contrast her perception of herself and her perception of you. It is particularly important for her to learn that her anxiety narrows her focus so that she ends up concentrating only on potential threats.

In addition to focusing the engagement on our relationship, I also encourage the bivalent people I coach to keep a diary in which to reflect on each day’s events. Recording thoughts explicitly helps people think about them more deeply, an essential step in making them more effective at replacing negative self-defeating thoughts with more nuanced, realistic ones. When you actually find yourself writing down your perception that your boss was late at a staff presentation you organized because she wants to undermine your credibility with your reports, for example, you are more likely to question the reality of that perception.

This two-pronged approach helps people who struggle with this start paying attention to their feelings and make an effort to stop and think about what is happening before reacting. By using our relationship as an experiment and by keeping a diary Joan gradually learned to bring her impulses under some control. This helped her to realize that at work she was projecting her own fears and insecurities onto others. Slowly but surely, she became ready to accept that we all have flaws, and not everything is either black or white. After a year of learning to let in the grey, she got the promotion her boss had previously ruled out.

[image error]

Tackle Bias in Your Company Without Making People Defensive

Unconscious bias is all the rage. Barely a blip on Google’s radar in 2010, a Google trends search shows how much the term has now gone mainstream. This is progress. Every manager can learn from the excellent The Invention of Difference by Jo and Binna Kandola, the 4-part series by Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant in the New York Times, or the various articles that have appeared in this magazine, by Herminia Ibarra, Robin Ely, and Deborah Kolb, Joan C. Williams, and others. And at our firm, we’re seeing a sudden surge in interest for sessions on unconscious bias to address gender imbalances. It’s a promising shift from the exclusively women-focused initiatives that have dominated corporate balancing efforts for the past couple of decades.

I applaud this progress, and to maximize its impact, I’d like to suggest a productive way of bringing bias to the table, without losing half your guests. While hitting people over the head with accusations of bias may be a satisfaction for some, it is not well received by many.

The Chief Diversity Officers who ask us for these programs love them. But managers generally don’t. Defensiveness, contempt, or stonewalling are all on pretty immediate display. Is there a better, less abrasive way to achieve the same outcome? Can we build more inclusive management styles that leverage today’s talent and serve today’s heterogeneous customers without alienating the people we want to engage? Yes, and it starts with what we call it. Focusing people on positive outcomes is far more motivating than accusing them of misbehavior – conscious or unconscious. And it’s simple enough to do. It starts with branding.

Recently, we were invited to help with the launch of a company’s gender initiative. They were all set with presentations that highlighted the gender imbalance in their management teams and framed the loss of female talent as a serious problem that needed management’s attention. This is the common default framing. (We call it the unconscious bias of the gender teams.) The Head of Diversity was going to announce, at the annual company management conference, that she was launching a series of unconscious bias training sessions on gender for the several hundred managers in the room.

The only problem is, this is a guaranteed, set-up-to-fail mechanism. How enthusiastic do you think the people in the room, 80% of them men, will be to hear that? Most of your company’s managers, male or female, are probably committed to the idea that their company’s systems are based on a meritocracy principle. They don’t really like being accused of gender bias before they even enter the room. The fact that all humans are biased to some degree is well researched. And addressing this reality is key. But there are more or less effective ways to bring the topic into companies. It starts with flipping the issue from a divisive, negative problem to a unifying, shared opportunity.

So focus on the opportunity, not the problem. Start by focusing on the key strategic goals. What are your 2020 objectives, targets and milestones? Get the CEO to start there. And then suggest that gender balance is a lever to help you reach that goal. Here’s an example from a real company we’ve worked with:

We set a bold target of hitting $10 billion in revenue by 2020. Getting the very best talent and delivering the very best customer service will be the dual keys to our success. Understanding, anticipating and delighting customers means ensuring we know what they want and how they feel. That requires having the best balance of talent in-house, talent that “gets” where our fast-changing market is heading. I believe gender balance is one of the key levers to unlocking huge, untapped talent and market opportunities. Today’s talent pool is balanced, so are our customers. We want to reflect that reality inside. So we are going to focus on leadership skills and tools to build balanced teams that continually deliver stellar service.

This “tone from the top” has a different impact. It results, from the start, with a more engaged, less defensive management team.

So, in summary, if you are working on launching or accelerating a push for more gender balance in your company, start by asking these questions:

Strategic opportunity: Are you positioning gender as a problem or as an opportunity?

Positive branding: Are you using language that accuses or language that invites them to build skills and enhance leadership impact?

Authentic leadership: Are you engaging with the majority of your managers on things they understand are central to both their individual and company success? Or are your efforts perceived as politically correct, tick-the-box exercises?

It is an important moment on the road to more balanced businesses. But the final goal isn’t balance. The goal is more engaged employees and more connected customers. You probably can’t repeat that too often. Leaders need to keep everyone’s eye on that ball, while drawing everyone into the game.

Best-in-class companies are moving on from an era of over-focusing on women as the solution to balance. Now, they are focusing on managers. It’s an unprecedented opportunity to get everyone positively primed for balance. Let’s not lose them by accusing them. Companies are spending a lot of time and money on leadership. Let’s make sure that whatever the 21st leadership model you work with, gender “bilingualism” is built in.

We must practice what we preach about leading inclusively. Do your messages speak to 100% of your people?

[image error]

Why Your Customer Loyalty Program Isn’t Working

Aggressive moves by airlines to migrate frequent flyer metrics from miles flown to dollars spent have caused bargain-hunting road warriors worldwide to whine about “disloyalty programs.” A PriceWaterhouseCoopers review suggests roughly 45% of flyers would lose under the new schemes. Conversely, about 40% would benefit.

Flyers taking shorter, more expensive trips, in other words, will reap more benefits than passengers purchasing long-distance discounts. This shouldn’t surprise. Airlines have clearly calculated that customers who spend more are more valuable to them than customers who fly more. The economics are simple and straightforward.

This latest frequent flyer reboot is an example of how the meaning, measure, and management of “customer loyalty” are changing. Nurturing customer loyalty requires a better understanding of its nature, and the nature of loyalty depends on the economics of the business: loyalty to automobiles and mobile phones is qualitatively and quantitatively different than loyalty to hotels and airlines. So serious customer-centric organizations and innovative marketers are decreasingly asking, “How do we make our customers more loyal?” and instead asking themselves, “What kind of loyalty do we want our customers to have, and do we want to have for our customers?”

Organizations need to identify the loyal behaviors that most deserve explicit recognition, reward, and investment. How should loyalty from the best and/or most valuable customers be recognized and rewarded differently from that of typical or average customers? The answer depends on how businesses and their customers define, perceive, and value loyalty. Those answers aren’t obvious.

Walmart’s “savings catcher” initiative offers a brilliantly simple approach to these questions. Unlike Tesco, which pioneered data-driven customer loyalty programs, Walmart has never sought to discriminate between best and typical customers. Walmart says it wants to offer everyday low prices to everybody. That’s central to its brand equity, unique selling proposition, and customer experience. But Walmart’s savings catcher app is a clever loyalty play because it effectively promises shoppers that they will never overpay for purchasing at the store. By submitting their receipt through the app, Walmart customers receive credit in their account if the product was available for a lower price elsewhere. Walmart is loyal to its customers by providing a tool and technology that allows it to honors its “everyday low prices” promise to shoppers. Shoppers are rewarded for their loyalty to Walmart by having Walmart do comparison shopping for them. Savings catcher creates and cultivates a loyalty behavior that makes the relationship more valuable to both. That’s not a loyalty program based on points, frequency, or customer profiles but a loyalty mechanism built on the foundation of the company’s brand promise.

True loyalty doesn’t just serve and preserve valuable customer relationships; it creates and inspires more valuable customers. Loyalty is a mutual investment, not just an exchange. That’s why improving the loyalty of bargain hunters rarely delivers sustainable value. Promotions acquiring customers who care more about momentary transactions than ongoing relationships is bad business. Retaining costly customers who stress out customer service staff usually proves a money-losing proposition.

When loyalty involves bribery, it’s bad for business, morale, and customer expectations. Confusing loyalty with retention, promotion, and rewards undermines brand equity more than it creates new value opportunities. Organizations should have the courage to either take loyalty seriously — to be as loyal to their customers as they hope their customers will be to them — or get out of the game.

Ironically but appropriately, the rise of social media platforms such as Yelp, Facebook, Twitter, and TripAdvisor guarantee that customers will get a global say on what loyalty should mean and who “loyal customers” really are. They’re rewriting the economic rules about customer value. Who is truly more valuable to an airline or hotel chain? A profitable repeat customer? Or a two-thirds as profitable customer whose comments and critiques on Twitter and Yelp influence hundreds of prospects?

Similarly, how valuable is a “typical” customer who makes suggestions to a hotel — or retailer or software developer — that can be worth hundreds of thousands in insight? When loyalty can be defined as innovative contributions and influential word-of-mouth as opposed to repeat high-margin business, traditional measures and metrics for loyalty decay into anachronism.

Loyalty here is as much about ethics as it is business. Loyalty shouldn’t be a data-driven gimmick for capturing customers and market share. It is one of those rare virtues that can be both a means and an end for new value creation in healthy relationships between consumers and companies. But that only happens if companies commit to offering loyalty as well as asking for it.

[image error]

The Right (and Wrong) Way to Network

Some people line up lunches and coffee dates because they’re in search of a job, venture funding, or clients for their company. But if that’s the reason you’re having a networking meeting, you — and your invitee — aren’t likely to get much satisfaction. As Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino and her colleagues have noted, “transactional networking” — i.e., “networking with the goal of advancement” — often makes participants feel so bad about themselves, they feel “dirty.”

That doesn’t mean you should never initiate meetings if you have a specific, immediate goal in mind. But that shouldn’t be confused with “networking.” If you’re honest with your intentions upfront (“I have a new startup, I’m seeking angel funding, and I think you’d be a great partner”), then the other person can make an informed decision about whether to connect. But networking — meeting with the goal of building a robust set of connections over time — is a different process with its own set of best practices. Here’s how to do it successfully.

Research in order to find a commonality. How do you build an immediate connection? According to psychologist Robert Cialdini, the answer is to find a commonality with the other person as quickly as possible. If you happen to meet someone at a conference, you can steer the conversation and try to dig for possibilities (perhaps you might live in the same neighborhood or have kids the same age), but with a pre-planned networking meeting, you have an edge that surprisingly few people take full advantage of: the ability to research the person online beforehand.

Using LinkedIn, Twitter, and other online search results, you can almost certainly find something you share that will serve as a conversation starter. A shared alma mater, hobby, or professional interest can quickly get the person to see you as a peer and someone “on their team.” Starting with a commonality, and then branching into some thoughtful prepared questions about them and their business, will ensure the discussion gets off to a good start. (And help you avoid painfully hackneyed queries like, “What keeps you up at night?”)

Further Reading

Running Meetings (20-Minute Manager Series)

Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Meet in person if possible. In a globalized world, geography often intervenes. Last week, I had an initial call with a friend-of-a-friend in Singapore, and we’re not likely to connect in person anytime soon. A phone call is a good start (they’ll at least remember your name and know something about you), but it’s a much weaker form of connection than the alternatives. Video conferences are slightly better; as I describe in my forthcoming book Stand Out, my friend John Corcoran, a Bay Area podcaster, makes sure to conduct his interviews with Skype’s video feature, even though he only uses the audio tracks, because he wants to establish a face-to-face connection. But wherever possible, find out when the person will next be in your city (or vice versa) and make a plan to connect then to cement your new tie.

Arrive with a hypothesis on how to help. It’s a sweet gesture, but I’m often flummoxed when people conclude a meeting with me by asking, “So how can I help you?” Often, I have no idea (I don’t know enough about them yet), and feel bad when I’m left with nothing to say. There’s also the lingering suspicion that in some cases, it may be a quid-pro-quo offer and that if I respond, “I don’t know, how can I help you?” they may unleash a torrent of requests.

Don’t make your colleague do the work. In advance of the meeting, formulate a hypothesis about how you can be helpful to them, and throughout the course of your conversation, test it with subtle questions. Then, at or near the end of the meeting, you can ask them explicitly whether your idea would actually be useful. For instance, if you’re meeting an entrepreneur, it’s a pretty safe bet that they’re looking for new clients, so if you know someone who could use their product or services, they’d probably appreciate an introduction. Similarly, offers of publicity are likely to go over well (perhaps you know the program chair for the Chamber of Commerce or your professional association). Even small gestures, such as sharing someone’s social media posts or commenting on their blog, are thoughtful forms of giving that are likely to be noticed.

Don’t ask for favors – for a very long time. I recently received a LinkedIn request from someone I didn’t know (or barely knew – his message mentioned meeting me, but I have no idea where). I accepted, and within minutes, a message flooded into my inbox. “This is totally asking a big favor,” he began. But, he went on, he’d like an introduction to an editor at a high-level publication I write for. Hint: if you have to use the phrase “this is totally asking a big favor” with someone you hardly know, you shouldn’t be making the ask.

I learned this the hard way early on in my career. I’d connected with a woman who had recently spoken at a major conference I was eager to break into. Shortly after meeting her, I followed up with an email, asking how she’d managed to land the speaking engagement. I was genuinely curious about the process; I wasn’t asking for an introduction. But I subsequently realized it may have come off that way implicitly, and she never wrote me back – then or ever again. My new rule of thumb, which may sound draconian, is to wait at least a year to ask someone for a favor of any magnitude. It’s fantastic if someone proactively offers to help you before that – and people often will — but it’s essential they feel it’s their idea, rather than something they’re coerced into doing.

Of course, there are exceptions to the “rule” and if you’ve become fast friends with someone to the point where it’s clear you’re not using them, then ask away. But it’s far better to err on the side of waiting and establishing trust early on by helping them, rather than extracting a short-term payoff that damages the relationship.

Networking meetings can be the start of intensely fruitful relationships. They may lead to business deals, connections to other great people, job offers, and more. But those are side effects of relationship building, and your meetings will be far more successful if you don’t go in explicitly seeking them.

[image error]

Why Greece and Cyprus May Be Better Off Without the Euro

The battles may be over, but the war is just beginning. Although the Eurozone’s 19 finance ministers recently threw Greece a much-needed economic lifeline, and the latter repaid the first of four loan installments that it owes the IMF in March 2015, there’s no long-term relief in sight for the troubled economy.

Greece has only managed to wrest the four-month extension of a stability program. Soon, the newly elected Alexis Tsipras administration will have to start implementing the cost-cutting measures that it had promised voters it would avoid. The question is whether the austerity program will help or hurt Greece.

Judging by the travails of another struggling Eurozone economy, Cyprus, the outcome is far from certain. Two years ago, the much-hated Troika (the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the IMF) provided €10 billion to Cyprus after insisting that it should contribute €5.8 billion (later, that went up to €13 billion) to the rescue package. The bailout was small compared to the sums the Troika gave Greece (€240 billion in two rounds), Spain (€100 billion), and Ireland (€85 billion), and the latter was a significant percentage of Cyprus’ GDP of €17.7 billion in 2012. Yet, Cypriot policymakers had no choice but to accept the harsh terms; the alternative would have been economic collapse.

The austerity program is threatening to be more a curse than a panacea, with Cyprus’ economy contracting by 2.4% in 2012; 5.4% in 2013; and by an estimated 2.8% in 2014. In fact, the island’s growth has been below the global average since 2009, with the gap widening since 2012. Unemployment in Cyprus touched 16% last year, with 35.5% of its youth without jobs.

Worse could happen in Greece. While the Troika has refused to budge on the austerity agenda, Greece’s GDP has shrunk every year since 2008, with the biggest contraction being 9% in 2011. With youth unemployment of over 50%, and total unemployment of around 25%, the Greeks’ living standards have plummeted.

Austerity programs, several economists argue, have lost their credibility. When governments reduce fiscal stimuli, it tends to lead to deeper recessions. To be sure, policymakers have to tackle the structural issues, such as bloated public sectors and high national debt, in Cyprus and Greece. However, that should be done over time, and, ideally, when those economies are strong enough to deal with reductions in government spending rather than when they are at their most vulnerable.

Clearly, the exit of both Cyprus and Greece from the European Currency Union is a distinct possibility. The scares about what would happen if they left are unjustified, especially in the medium term.

A return to the national currency would give the governments of Greece and Cyprus control of key economic levers rather than having to bear the fiscal inflexibility and targets necessitated by a single cross-national currency. In fact, Cyprus and Greece probably don’t need to be part of the Eurozone to grow. Cyprus’ growth was higher between 1980 and 2004, before it joined the Eurozone, than between 2004 and 2014, and it has been particularly low since 2008, when it adopted the Euro. There’s no reason why its economy cannot be strong without being part of the Eurozone, or that foreign currency deposits will flee the island if the local currency is not the Euro.

An alternate way forward may be to use higher government spending to assist vulnerable people, to lend to business, and to execute projects that inject money into the economy. The state can do that in conjunction with structural reforms that will, over time, reduce the size of the public sector, increase the flexibility of labor, improve tax collections, invite foreign direct investment, and get debt under control. The relatively cheap national currencies would provide a boost to exports, real estate, manufacturing, agriculture (for instance, olive oil production), and services such as tourism.

Business thrives under conditions of certainty, which has been sorely lacking in Cyprus and Greece since the implementation of the austerity agenda. A managed exit from the common currency could alter that.

Local companies would be able to focus on globalization strategies and exports in order to capitalize on cheaper currencies. They would become more efficient and productive; they would have to optimize the use of more expensive imports. Foreign companies might find the greater confidence and low costs attractive for making investments in Greece and Cyprus, which would further enhance business confidence. These outcomes seem more desirable than an era of austerity with no end in sight, an epoch that will leave Greece and Cyprus unable to cope with future crises.

[image error]

March 9, 2015

Cancelling One-on-One Meetings Destroys Your Productivity

We all can agree that we have too many meetings. From the one-off event to the weekly check-in with an employee, meetings are taking an increasing amount of time in our daily work. But removing meetings from your calendar isn’t always the best way to take back your time.

When faced with an onslaught of regular meetings, many managers fall into the trap of believing that they’re too busy to keep their one-on-one meetings with their direct reports, figuring that these sit-downs are not as important as all the other items they have on their agenda. They assume these meetings can be substituted with an email exchange or an open-door policy, whereby people can stop by with a quick question, instead of demanding a 30-minute chunk of a day. But this strategy is highly inefficient. It’s true that canceling one-on-one meetings can appear to open up more space on your calendar, but in my experience as a time coach, I see again and again that not taking the time at the front end to effectively manage your direct reports leads to a lot of wasted time on the back end.

There are some obvious issues that come from cancelling these meetings with regards to your direct reports’ work. Not having a predictable scheduled time with you can lead employees to work on something incorrectly, which can cause unnecessary emergencies and wasted time fixing errors. Or it can lead to a decrease in productivity because employees are confused and unclear about their priorities and therefore don’t accomplish much.

But the costs of not keeping one-on-one meetings — and not running them effectively — are in fact much, much higher in terms of your own time management and productivity. When you don’t commit to specific time with boundaries when you will devote your attention to your direct reports, they need to find other, much less effective ways to connect with you. They may start sending you lots of e-mails because, as questions come up, they’re unsure of when they will meet with you next. They may hover outside your office trying to catch you in between meetings. This is not only a waste of their time, waiting for a response or hanging out like lobbyists in hopes of catching a few distracted minutes with you, but also this leads to you feeling no sense of control over your schedule. You’re constantly distracted. You never know when someone will be at your door, so you don’t feel like you can plan to get your important work done (or even answer e-mails) in the gaps between meetings. If they knew they could count on their one-on-one time with you, they could save those questions and go through them with you all at once.

You and Your Team

Meetings

How to make them more productive.

When you cancel one-on-ones and compensate with an open door policy, your time investment mimics that of a call center employee who takes requests in the order they are received, instead of an effective manager and executive who aligns his time investment with his priorities. Yes, giving feedback and support is part of your role, but it’s absolutely not all it takes to operate in an effective way in your position.

To help reinstate a sense of predictability with your direct reports, get in place weekly or biweekly recurring meetings. Make a commitment to do whatever possible to keep them, even if it means you connect by phone instead of in person or for a shorter amount of time.

Then, as you increase your level of commitment to your employees, require that same level of commitment from them by holding them accountable for the effectiveness of their interactions with you. Request that tracking documents are updated in advance of your meetings and reports on action items are sent in advance for you to review quickly. This teaches your staff to think activities through, anticipate issues, problem solve on their own, and effectively leverage your time instead of dropping by whenever questions come up. Your one-on-one time can then be spent on answering questions, problem solving, and strategic thinking instead of status updates. This is also an opportunity for you to offer direction on priorities and strategy, since with your uninterrupted open time, you can think strategically about what’s happening and communicate that to your direct reports.

This also means that you want to create the expectation that all nonurgent items will be covered in your scheduled meetings and that it’s not acceptable to drop by on a frequent basis with questions that could easily be covered in a one-on-one. You can also save your nonurgent e-mails and reply to them all verbally when you meet.

To maximize the effectiveness of this strategy — especially when you’re retraining your staff — you may need to close your door during some portion of the day so you can focus on the activities you need to get done, whether it’s strategy work, prep for a presentation, or simply pounding through some e-mail. Closing your door isn’t saying you don’t care about people or their work problems, but it is saying that you honor your commitments to yourself and other important work. Your direct reports are less likely to violate this uninterrupted work time, since you’ve shown them the respect of making and keeping your one-on-one meetings with them. They should have what they need to move forward with their own projects, so you can focus on yours without concern that you’re the bottleneck.

Of course, I’m not suggesting that you keep your door closed all the time or that you never accept questions in between one-on-ones. But by creating a culture where these regular meetings are respected and dropping by is the exception, not the norm, you create a much more respectful, efficient, and effective culture in which everyone has a better ability to align their time investment with their priorities.

[image error]

Why Congress Needs to Pass the Innovation Act This Time

In 1939, the most notorious politician in notoriously corrupt Chicago was Alderman Mathias “Paddy” Bauler. When he managed to beat a reform-minded opponent by just 243 votes (four of which cast by ghost-voters purporting to live at the address of Bauler`s own tavern) he made a declaration that still lives today: “Chicago ain’t ready for reform.”

Looking at the current calls for patent law reform, are we in the same state of readiness? Our patent system, designed to protect inventors by granting them limited-term monopolies over their innovations, has over the last twenty years largely collapsed, buried under an avalanche of new and generously-granted patents for so-called “business methods” and for software-related inventions, which are doubly protected under copyright law.

Legal standards are also deteriorating, encouraging abusive lawsuits. Firms who buy up vast swaths of dubious patents and then use them to squeeze settlements out of deep-pocketed (or not) technology companies and their customers troll the federal courtrooms of the Eastern District of Texas, notorious for its excessive jury awards to plaintiffs. Elsewhere, judges are quick to grant injunctions banning infringing items from sale or importation, even in complex devices such as smartphones and tablets made up of thousands of components, in which the alleged infringement is for a trivial or obvious design element.

All told, according to the Consumer Electronics Association, a leading trade association, patent abuse is costing the U.S. economy $1.5 billion a week. Yes, a week.

If there’s consensus on anything in Washington these days, it’s on the need for some reform of the patent system. So what’s the holdup? Last year, a modest reform bill passed the House by a whopping 395 to 91 vote margin, only to die in the Senate, apparently at the behest of former Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV).

That bill, known as the Innovation Act, was reintroduced last month in the House by its author, Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-VA), Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, along with a bi-partisan group of 20 co-sponsors. And this time, there’s no Majority Leader Reid to stop it in the Senate. So patent reformers are cautiously optimistic that real change may come this year.

The Innovation Act’s provisions would make an important dent in the worst excesses of the system. If passed, it would force plaintiffs to be more specific about the patents they are asserting as infringed. It would help unmask the true identity of companies who stand to benefit financially from the litigation of so-called non-practicing entities (NPEs), more frequently known as “patent trolls.” It would limit the extent of pre-trial discovery, which can cost millions and put pressure on innocent defendants to settle. And it would protect product users from being sued, allowing the manufacturer to take over the case.

The Act also includes an important provision that would permit trial judges to force a losing party to pay the legal fees of the winner, a further disincentive to what many see as frivolous lawsuits, often involving “junk” patents that never should have been granted in the first place.

Most of the provisions range from common sense to obvious.

But it’s still only a start. Even if the Innovation Act passes this time, structural defects in the patent system will be left unaddressed. The scourge of NPEs will be deterred, but hardly stopped. The Patent Office will still have incentives to err on the side of approving a tidal wave of applications, outsourcing to the more expensive, slower, and more random courts to work out which patents actually meet the stringent requirements for protection. Too many cases will still be left to lay juries, increasingly unable to make sense of the complex technical testimony with which they are bombarded.

The Innovation Act also does nothing to tighten loosening standards for granting injunctions that keep many valuable products out of the hands of consumers. That’s an increasingly serious problem. As the commercial life of high-technology products grows shorter than the term for patents that surround them, even leading innovators are leaning on the patent system as a crutch to protect their market position more than any particular product.

This week, for example, a federal appellate court in Washington, D.C. heard arguments in a case pitting Apple against Samsung, one of hundreds in the all-consuming patent war that has plagued the smartphone and tablet industries since the late Steve Jobs famously declared “thermonuclear war” over the release of Google’s Android operating system. Apple’s campaign, which eventually drew in every major manufacturer, has not only failed to stop Android, but has largely backfired against Apple, which has found itself sued for patent infringement by smaller manufacturers and NPEs. Last month, the company lost a case involving patents for downloading and paying for digital content on its devices, with the jury awarding NPE Smartflash over half a billion in damages.

Apple settled all of its remaining cases with Google and others last year, and ended its war with Samsung over Galaxy devices running Android, at least outside the U.S. In the last U.S. trial, which ended last year, federal judge Lucy Koh awarded Apple about $100 million for Samsung’s infringement of a handful of patents, including the design of Apple’s “slide to unlock” feature. (In an earlier 2012 trial, also on appeal, the same judge awarded Apple close to a billion dollars for infringement found in earlier Samsung devices).

Last year’s victory was pyrrhic, to say the least. The $100 million award, offset by a verdict for Samsung on its claim that Apple violated one of Samsung’s patents, is probably less than Apple paid to litigate the case. And adding insult to injury, the judge refused to issue an injunction against sale of the infringing Galaxy devices in the U.S., the only major issue Apple is challenging on appeal and likely the real point of bringing the suit in the first place.

A 2006 U.S. Supreme Court case involving eBay requires courts to weigh several factors before deciding on the extraordinary remedy of a permanent injunction. But Apple has challenged the application of that test on the novel theory that companies with a reputation for innovation deserve more deference. Consumers, they argue, are more confused by infringing products when the patent holder projects an image as the industry leader.

Whether or not that’s true, as Florian Mueller of the influential FOSS Patent blog notes, Apple didn’t actually invent the slide-to-unlock design in the first place. And other design patents in the Samsung case are being reexamined by the Patent Office, making application of the standard proposed by Apple inappropriate in any case. “In patent law, as Mueller writes, “it’s about who’s first to come up with something, not who’s first to convince millions of consumers to buy and use technologies that, for the most part, others created before Apple.”

So it isn’t just NPEs who take advantage of the quirks and inefficiencies of the patent system to secure in the courts what they can’t control in fast-evolving technology markets (markets characterized by fickle consumer tastes, or what Paul Nunes and I call “near perfect market information”). The most innovative companies in the world are likewise unable to resist the temptation to fight competition with litigation – even when it leaves them wide open to accusations of the same misconduct of which they say they are victims.

All the more reason for Congress to close as many as possible of the loopholes and yawning chasms that clever lawyers have introduced into the patent system – and to do so quickly. There will always be voices declaring we’re not ready for reform. It’s time to stop letting them win.

[image error]

How Smart CEOs Use Social Tools to Their Advantage

Advances in digital technology and their use in organizations carry huge promise to empower people at all levels. Social media and collaboration tools not only open the door to faster and more extensive knowledge-sharing, but they also enable conversations that skip levels, silo-busting, and self-organization. Big data and analytics can make organizations more efficient and agile by empowering middle-level and far-flung managers to make decisions and seize business opportunities that previously required scarce data and executive approval. But without an organization-wide understanding of what’s good for the business and what’s not, these powerful tools can be dangerous. Empowerment—in whatever form—requires alignment around purpose, strategic intent and the boundaries within which decisions can be made. Otherwise, it could result in confusion, contradictory behaviors and chaos.

Savvy CEOs use fire to fight fire, effectively employing digital media inside their organizations to create the kind of alignment and shared purpose they need. In our research, we find that smart leaders do these three things:

Tune into global conversations: It may seem odd to refer to the daily torrent of emails, tweets and posts as conversations, but in reality they are. Collaboration software and mobile apps make it possible for these conversations to connect practically everyone in the organization — and to distribute information and authority much more widely than ever before. Rather than be paralyzed by fear about who has access to what, savvy leaders recognize that information can empower employees to move the business closer to customers, that decision-making can be accelerated when vital data is not held hostage (or lost) and that visible conversations can prevent wasted effort and even spark innovation. For example, Microsoft IT leaders take their organization’s pulse using analytical software that monitors trending topics in their Yammer collaboration space. This allows CEO Satya Nadella to hear early warning signals. According to Microsoft, the goal is go beyond using scorecards and KPIs — historical views — to absorb and respond to real-time sentiments. Tools like Oblong Industries’ Mezzanine can bring multiple streams of data onto HD displays where they can be easily organized, manipulated, and archived into files that can be accessed for later use.

Smart leaders listen ahead — anticipating and shaping the way conversations move next — by inserting questions that stimulate or re-direct the conversation. Salesforce.com CEO Marc Benioff actively participates in conversation threads in order to stir the pot and keep current on the ways programmers and customers test the limits of his company’s products. His goal, like many of the leaders we interviewed, is to establish a presence that reliably represents who he is and what he stands for so that in the decentralized world of autonomous teams — that his company’s software has helped create — people can formulate strategy, make decisions and deal with ambiguity.

Leverage global networks: CEOs need to choose the most effective influence channels through which to create alignment. Interestingly, it’s here that an old and venerable feature of organizations — informal networks — takes on new prominence with social media. It is common knowledge that some of the most influential people don’t register on the formal org chart. Yet, what’s less well known is that when researchers conduct social network analyses, executives often cannot name even half of the “central connectors” (people to whom others turn for information and advice, in other words, the influencers) in their organizations.

In the digital enterprise, that unknown other half could turn out to be critical to establishing new directions about purpose, intent and boundaries — especially when everyone has the potential to connect with everyone else. Soon, leaders will be able to see and tap into influence networks inside their organizations using tools similar to those available in Facebook and LinkedIn. Knowing the real central connectors will mean that leaders can address more people faster than would be possible with a company-wide email blast.

As well as knowing who’s who in an organizational network, leaders need to be alert to the blind spots that may exist in their own personal networks. Personal networks can insulate, even diminish a leader’s presence. For example, a study of a multinational pharmaceutical company revealed that leaders in its U.S. subsidiary’s networks were skewed to “familiar” faces: people from similar functional backgrounds, hierarchical levels, and cultural and gender groups. Their networks kept divergent or controversial news from getting in and hindered their ability to get important messages out. This might not have mattered in a time when “old boy networks” ruled the roost, but in an era when workforces are increasingly diverse and difference is a source of both innovation and revenue, leaders cannot afford to cut themselves off from the networks that compose their organizations.

And, in a networked environment where everyone can be a fact checker, trust is essential to aligned action. As Luis Di Como, Unilever’s senior vice president for digital media, told us, when leaders venture online (whether internally, externally or both) authenticity matters hugely: “Authenticity must be at the center of your online presence in order to have credibility with the people who work with you.”

Deepen the dialogue: It is well understood that a leader’s ability to articulate strategic priorities in a compelling way can mean the difference between moving fast in a common direction and spinning in place. However, traction depends on more than the frequency with which strategy is communicated. It depends on the richness and the accessibility of the leader’s thinking. One emergent use of social media is a new sort of leadership mind map, i.e., a model of the CEO’s key ideas accessible to any corner of the organization.

Popularized in the 1980s, mind mapping was designed as a visual technique for individuals to array topics of interest, much like some people use their computer’s virtual desktop to create clusters of activities or ideas. Now, programmers are replacing hand-drawn diagrams with robust digital illustrations connected to databases that can be easily accessed and queried. Harlan Hugh, CEO of TheBrain.com, told us that mind mapping will soon evolve into a vehicle for rich communication: “I can put my thinking into something and then another person who is on the same topic can get the benefit of my analysis.” Dr. Craig Baker, Chief of Cardiac Surgery at the University of Southern California developed his private store of data, articles and videos into a public “brain,” accessible to students in his absence. It has since become a team brain — a resource for a rapidly evolving field — built with contributions from colleagues at USC and beyond.

Until now, the biggest drawback to mind-mapping has been the amount of time it takes to build a brain and keep it current. However, semantic software and unstructured data analytics tools are making it possible to scan speeches, memos, blog entries, etc., to automate the creation of mind maps and, by extension, to create leader “brains” that employees and others can access and explore. When they can digitally share their brains, leaders can achieve a more robust digital presence than would be possible even by the most ambitious internal media campaign or whistle-stop tour of the company. Leaders will be able to provide insight, even wisdom, without being physically present.

The implications are clear: savvy leaders make the most of digital technology to galvanize their organization around a shared understanding of the business. When leaders use social media to become aware of the conversations within their organizations and can identify those that generate the most energy or emotion, they can allocate their attention and their interventions with greater impact. When they are able to see and tap into social networks, leaders will be able to interact with their organization the way a symphony conductor does — in real time with nuanced or direct intervention depending on what’s needed. And when leaders can share how they think about a problem — with many people at once and without even being there — everyone in the organization has a better understanding of where the organization is going and why. Even as digital media can sometimes create cacophony and confusion, few tools give leaders more power to strengthen their organizations.

[image error]

Setting the Record Straight on Negotiating Your Salary

You got the job. Now you’ve just got to settle the details, in particular how much you’ll get paid. If you’re like many people this gives you a pit in your stomach and sends you straight to the Internet (or a friend or a mentor) for advice. Are you supposed to negotiate no matter what they offer? Should you start with a really high number knowing you’ll have to come down? Do they expect you to play hardball to demonstrate you’ve got negotiating chops? The trouble is that there is a lot of conflicting advice out there.

We asked readers (and our own editors) what advice they hear most often on negotiating a salary and then talked with two experts to get their perspectives on whether the conventional wisdom holds up in practice and against research.

1. “Don’t ever name a figure, even if they ask. Instead wait for them to give the first number and negotiate from there.”

Deepak Malhotra, a professor in the Negotiations, Organizations and Markets Unit at Harvard Business School, says that it’s a reasonable question for a potential employer to ask and it’s in your best interests to answer it. “If there is too great a discrepancy between what you think you deserve (or can get elsewhere) and their expectations regarding what you should be paid, it is better to uncover this and try to reconcile the differences in expectations,” he says.

Both Malhotra and Jeff Weiss, a partner at Vantage Partners, a consultancy specializing in corporate negotiations, and author of the HBR Guide to Negotiating, point to research that suggests that there is great benefit to making the opening offer in a negotiation. “It can be a good thing to set the tone,” says Weiss. And you may also be able to nudge them upward if you can justify a “higher number than the one they would have started with,” says Malhotra.

Further Reading

15 Rules for Negotiating a Job Offer

Negotiations Feature

Deepak Malhotra

Save

Share

However, what matters is less about who goes first in a negotiation and more about how you approach the conversation. “Too many salary discussions are just ‘offer-counteroffer’ games. But that’s just a sure-fire way to end up with a number you won’t be happy with,” Weiss says. This does not mean that you want to talk about salary too early, warns Malhotra. It can be awkward if it’s one of the first things you bring up and it’s also “somewhat risky if you end up asking for too little.” His advice? Learn as much as you can—before and during the interview process—so that you can answer the question appropriately, if and when asked.

“If, despite all of this, you find yourself feeling quite unprepared to answer the question, you can honestly tell the other side this,” says Malhotra. It’s OK to say that you need more information, such as about what the role will be, before you answer.

Besides, your alternative to answering the question is refusing to. “That can make you seem difficult or unprepared,” says Malhotra. It goes without saying that you don’t want to look like a jerk. As he wrote in his article, “15 Rules for Negotiating a Job Offer,” “People are going to fight for you only if they like you. Anything you do in a negotiation that makes you less likable reduces the chances that the other side will work to get you a better offer.”

2. “Do your research and find out what other people with your title make in the company, or in the industry.”

You should do as much research as possible. “Search the Internet, use your network, go to your career development office or a trade association, if there is one,” says Weiss. There is lots of information out there that will help you piece together what people are making at the company,” says Weiss.

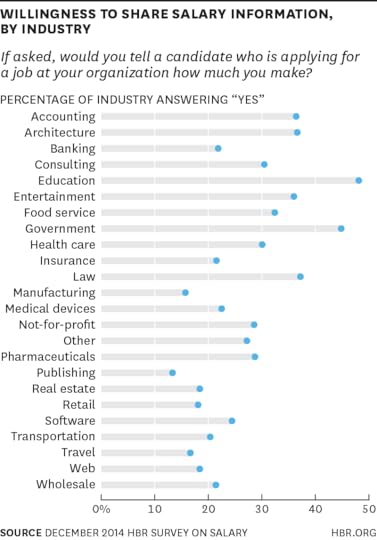

Reach out to people who work at the company through LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter and ask them what people make there. You might think this is an inappropriate question but in a recent HBR survey, 27% of respondents said that if asked, they would tell a job candidate how much they make. Of those who worked in education, government, and law, 48%, 44%, and 37% respectively said they would share that information with an applicant.

Of course, there may be limits to what you can find out, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Come prepared to the conversation with a list of the information that would be helpful to you in determining what a fair salary is. “It’s OK to ask questions that put the onus on the employer to gather more information,” says Weiss. You can inquire, “What is the typical salary range for a position like this one?” or “What do people with my same qualifications and years of experience make?”

It’s also helpful to find out what limitations your hiring manager is working with. Malhotra writes, “they may have certain ironclad constraints, such as salary caps, that no amount of negotiation can loosen. Your job is to figure out where they’re flexible and where they’re not.” Some companies may have a cohort of employees at the same level whom they have to pay the same. But they may be flexible on other things like signing bonus or vacation time. “The better you understand the constraints, the more likely it is that you’ll be able to propose options that solve both sides’ problems,” says Malhotra.

3. “Don’t accept the first offer — they expect you to negotiate and salary is always negotiable.”

“That’s just not true,” says Weiss. Sure, much of the time there is an opportunity to negotiate, but some hiring managers genuinely give you the only number they can offer. The best way to find out, says Weiss, is to inquire. And don’t just say, “Is that number negotiable?” but dig into what went into calculating the figure. Weiss suggests asking: Where did the number come from? What did you count as my years of experience? “There are many companies that don’t want you to negotiate but that doesn’t mean you don’t come back with questions,” he says. “If an offer is made, there is an opportunity to explore and expand it.”

But don’t negotiate just to negotiate, advises Malhotra. “Resist the temptation to prove that you are a great negotiator,” he writes. “If something is important to you, absolutely negotiate. But don’t haggle over every little thing. Fighting to get just a bit more can rub people the wrong way — and can limit your ability to negotiate with the company later in your career, when it may matter more.”

4. “Play hardball because it shows you’re good at negotiating.”

“If hardball means you’re well prepared, you come to the table with creative ideas, you negotiate with discipline, and you don’t roll over when pushed, then, yes, play hardball,” says Weiss. On the other hand, if it means making threats and banging the table, forget it. “You might win, but you also might piss a bunch of people off,” he says.

A smarter strategy, says Malhotra, is to think about what you feel you deserve and be prepared to explain why that is “the appropriate or fair amount.” Tell the story that goes with that number. “Far from playing hardball, you should be in the business of making their life easier,” he says. Think about how the hiring manager will be able to justify the amount you’ve requested to his boss or to HR. “Work with them to come up with creative solutions,” he advises.

5. (Corollary to #4) “If you’re a woman, don’t play hardball because you’ll look too aggressive.”

“There are very few contexts where the person hiring you wants to see you play hardball—whether you are a man or a woman,” says Malhotra. And Weiss agrees: “It might be more acceptable for men to rant and rave and make threats but I don’t think that’s good behavior for anyone.”

That’s not to say that women and men are on a level playing field. If fact, women are more hesitant to negotiate job offers precisely because they are treated differently. Research has shown that women are nervous about negotiating for higher pay because advocating for themselves presents a socially difficult situation for them. “Tragically, women do face greater potential backlash than do men when they try to negotiate for higher salaries,” says Malhotra. These risks may be mitigated only when “the other side sees the negotiator—man or woman—as being fair-minded, empathetic, collaborative, and well-prepared to discuss not only what is appropriate, but how best to achieve it.”

6. “Don’t just focus on the money. Think about the overall package.”

Many people think about a job negotiation as being about one number, but it’s not. It’s about the overall package: who you work for, what kind of training you’ll have, when you’ll start, etc. “Companies sometimes won’t budge on the dollar amount,” says Weiss. “But you can get a lot of value by asking for things that don’t cost much.” And often, says Malhotra, these other aspects of the job are where your satisfaction with the job will lie.

“Don’t get fixated on money. Focus on the value of the entire deal: responsibilities, location, travel, flexibility in work hours, opportunities for growth and promotion, perks, support for continued education, and so forth,” writes Malhotra. To figure out what specific aspects you want to negotiate, first think about what you want. Weiss advises exploring your interests behind the number. For example, if you want to make $75,000 at your job, ask yourself why. Is it because you want to travel or save up to eventually go back to school? If so, perhaps you would take less if the job allowed you to travel and came with a tuition reimbursement.

There are benefits that come at an additional cost to the company (e.g. a higher signing bonus), those that don’t cost anything (e.g. a flexible work schedule or rotations within the company), and those that have a price but are already existing benefits and therefore don’t cause trouble for the person you’re negotiating with (e.g. tuition reimbursement, participating in training). Things in the latter two categories are likely to be easier requests than the first and you shouldn’t hesitate to ask for them. With those in the first bucket, think carefully about how many requests you make.

Of course, even if you are able to create a sweeter deal for yourself with the overall package, the number still matters. “The salary you accept sets a baseline for the future — it’s often what your bonus is calculated on and is the basis for the raises you’ll get in the years to come,” says Weiss. So it’s worth getting to a number you feel good about.

But, if at the end of the day, you still haven’t reached your ideal number, don’t beat yourself up, or walk away necessarily. “Salaries are often renegotiable,” points out Weiss. “If you can’t get to the dollar amount you want today, keep in mind that you’ll be even more persuasive six or twelve months into the job when you’ve proven yourself.”

If you love the job and you want it, there is no question you should negotiate with the above principles in mind. But if you’re $10K shy of your request, don’t obsess over it. Instead, says Weiss: “Go in, be indispensable, and then negotiate a raise.”

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers