Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1307

March 23, 2015

Empathy Is Key to a Great Meeting

Yes, we all hate meetings. Yes, they are usually a waste of time. And yes, they’re here to stay. So it’s your responsibility as a leader to make them better. This doesn’t mean just make them shorter, more efficient, more organized. People need to enjoy them and, dare I say it, have fun.

Happiness matters a lot at work — how could it not, when many of us spend most of our waking hours there. The alternatives — chronic frustration, discontent, and outright hatred of our jobs — are simply not acceptable. Negative feelings interfere with creativity and innovation, not to mention collaboration. And let’s face it — meetings are, for the most part, still where lots of collaboration, creativity, and innovation happen. If meetings aren’t working, then chances are we’re not able to do what we need to do.

So how do we fix meetings so they are more enjoyable and produce more positive feelings? Sure, invite the right people, create better agendas, and be better prepared. Those are baseline fixes. But if you really want to improve how people work together at meetings, you’ll need to rely on—and maybe develop—a couple of key emotional intelligence competencies: empathy and emotional self-management.

Why empathy? Empathy is a competency that allows you to read people. Who is supporting whom? Who is pissed off and who is coasting? Where is the resistance? This isn’t as easy as it seems. Sometimes, the smartest resisters often look like supporters, but they’re not supportive at all. They’re smart, sneaky idea-killers.

Carefully reading people will also help you understand the major, and often hidden conflicts in the group. Hint: These conflicts probably have nothing to do with the topics or decisions being made at the meeting. It is far more likely to be linked to very human dynamics like who is allowed to influence whom: headquarters vs. the field; expats vs. local nationals; and power dynamics between men and women, and among people of various races.

Empathy lets you “see” and manage these power dynamics. Many of us would like to think that these dynamics — and office politics, in general — are beneath us, unimportant, or just for those Machiavellian folks we all dislike. Realistically, though, power is hugely important in groups because it is . And it plays out in meetings. Learning to read how the flow of power is moving and shifting can help you lead the meeting — and everything else.

You and Your Team

Meetings

How to make them more productive.

Keep in mind that employing empathy will help you understand how people are responding to you. As a leader you are, possibly, the most powerful person at the meeting. Some people, the dependent types, will defer at every turn. That feels good, for a minute. Carry on that way and you’re likely to create a dependent group — or one that is polarized between those who will do anything you want and those who will not.

This is where emotional self-management comes in, for a couple of reasons. First, take the dependent folks in your meetings. Again, it can feel really good to have people admire you and agree with your every word. In fact, this can be a huge relief in our conflict-ridden organizations. But if you don’t manage your response, you will make group dynamics worse, as I mentioned above. You will also look like a fool. Others are reading the group, too, and they will rightly read that you like it when people go along with you. They will see that you are falling prey to your own ego or those who want to please or manipulate you.

Second, strong emotions set the tone for the entire group. We take our cue from one another about how to feel about what’s going on around us. Are we in danger? Is there cause for celebration? Should we be fed up and cynical or hopeful and committed? Here’s why this matters in meetings: If you, as a leader, manage your more positive emotions, such as hope and enthusiasm, others will “mirror” these feelings and the general tone of the group will be marked by optimism and a sense of “we’re in this together, and we can do it.” And, there is a strong neurological link between feelings and cognition. We think more clearly and more creatively when our feelings are largely positive, and when we are appropriately challenged.

The other side of the coin is obvious. Your negative emotions are also contagious, and they are almost always destructive if unchecked and unmanaged. Express anger, contempt, or disrespect and you will definitely push people into fight mode — individually and collectively. Express disdain, and you’ll alienate people far beyond the end of the meeting. And it doesn’t matter who you feel this way about. All it takes if for people to see it and they will catch it — and worry that next time your target will be them.

This is not to say that all positive emotions are good all the time or that you should never express negative emotions. The point is that the leader’s emotions are highly infectious. Know this and manage your feelings accordingly to create the kind of environment where people can work together to make decisions and get things done.

It may go without saying, but you can’t do any of this with your phone on. As Dan Goleman shares in his book Focus, we are not nearly as good at multitasking as we think we are. Actually we stink at it. So turn it off and pay attention to the people you are with today.

In the end, it’s your job to make sure people leave your meeting feeling pretty good about what’s happened, their contributions, and you as the leader. Empathy allows you to read what’s going on, and self-management helps you move the group to a mood that supports getting things done — and happiness.

[image error]

March 20, 2015

When Learning at Work Becomes Overwhelming

Many skilled jobs require a considerable amount of learning while doing, but learning requirements have reached unrealistic levels in many roles and work situations today. This phenomenon of “too much to learn” is not only feeding the perception of critical skills shortages in many sectors, but it can also accelerate burnout.

Consider this: chief nursing officers (CNOs), who oversee large nursing workforces in midsize and major health systems, have knowledge-intensive jobs to begin with. These leaders barely have time to brush their teeth. But with the rapid implementation of electronic health records (EHRs), CNOs are now expected to master new trends in health care information technologies to engage hospital leaders in strategic discussions about major technology investments.

This technology knowledge is piled on top of existing expertise nurse executives are expected to have about clinical practice, patient experience, finance, safety, employee relations, process improvement, leadership development, and managing interdisciplinary teams. The list goes on and on.

“Without sufficient time to process and make sense of all that must be learned, burnout manifests in several ways,” says Michael Bleich, president of Goldfarb School of Nursing. Executives can stop taking in information that seems too complex or problematic to interpret, and instead grab superficial summaries that preclude a deeper understanding of the subject. Thus, leaders faced with learning overload are more likely to default to intuition, rather than more evidence-based decision making.

This problem is not limited to top management, however. Even in an office setting, demands to learn more can become unrealistic. Young management accountants today are supposed to acquire competencies in a dizzying array of topics, such as advanced presentation skills, Six Sigma, quantitative methods, and even leadership. Is it surprising that management thinks there is a skills gap in management accounting?

Several things happen to less experienced employees when there’s too much to learn. A sense of frustration and incompetence can set in, as employees blame themselves for not knowing enough. Priorities get misplaced when it’s not clear what to learn first, and colleagues get angry if mistakes are made that hurt the group’s performance.

The primary driver for new learning is increasingly complex and essential technologies. In their important book Race Against the Machine, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue that, because of recent advances in information technologies, we have entered a new phase of history. These MIT economists insist we’re now in a race between education and technology, if workers’ skills are to stay economically viable. I’d argue that talk of a “skills gap” in any field (whether real or imagined) is evidence that education — both formal and informal — is losing the race with technology.

But it’s not just technology causing this learning overload. Other factors, such as a thin leadership pipeline, relentless emphasis on performance improvement, increased supply chain integration, continual new product introductions, and the demands of regulatory compliance, make intense learning an essential task in most jobs today.

Failure to anticipate and accommodate greater learning loads in many jobs produces more costly turnover as employees quit in frustration or are forced out because they can’t perform at the required level. As more experienced Baby Boomers retire and rapidly changing technologies and global competition demand more complex know-how, these learning dilemmas will only increase. Structuring roles with unrealistic learning requirements, combined with high performance standards, will be an increasingly costly problem.

You can reduce the risks that learning overload will increase unwanted turnover and hurt individual performance by answering three questions.

1. What is a realistic amount of learning to expect of people in this job?

Of course, learning capacity depends on the individuals involved and the specific profession. Medical interns in their first year out of school, for example, are expected to learn voraciously, while you wouldn’t expect the same behavior of risk managers in an insurance company. If it’s not already clear, management needs to set realistic expectations and make learning requirements for a particular role discussable.

Ironically, setting higher expectations for learning is likely to improve retention of younger employees, who are usually much more attracted to jobs where they are asked to learn a lot, as opposed to positions where learning is limited. Managers must keep that in mind as they’re assessing each position.

2. What are learning priorities?

Some jobs today require levels of learning than seem unsustainable. New nurses can be overwhelmed when they are hired into a complex health care setting, often leading to unwanted turnover. In order to be clear about what employees do and don’t need to learn, management must communicate what skills or know-how it considers most critical to success in a particular job. This means being more specific and realistic in defining particular roles. Does an internal sales job in manufacturing require mastering the entire product line and customer base all at once? Should certain segments be given priority? Is there a more logical order to master knowledge essential in the job?

In other words, clearly bound the scope of what has to be learned. Take the case of the chief nursing officer who needs to understand new health care IT options. This can be overwhelming, but CNOs don’t need a doctorate in the field. Eric Bloom, a former CIO and an expert in the education of IT leaders, says CNOs just need to learn what products are out there, and what the benefits and costs are. While some hospitals are hiring new experts in nursing informatics, another way to do this, Bloom says, is to bring in the top five vendors in the field to show you what’s available. Also, meet with experts from your hospital’s IT group to learn about applications that will enhance patient safety and make your nurses more productive. Ultimately, the CNO needs to learn the business questions to be asking about specific IT offerings, not the intricate details about the technology itself.

3. How can we make learning more practical and efficient?

Learning overload is exacerbated when employees don’t have the infrastructure they need to improve their know-how. My colleague Steve Trautman recommends an “air, food, and water” list of what’s needed to learn effectively in a particular job. This means identifying the fundamental computer setups and orientation, current documentation, network passwords, and introductions to key people — all that is needed to learn effectively. Without these basics, workers waste a tremendous amount of time trying to become more proficient on the job.

Probably the most important thing you can do to improve on-the-job learning is to enhance the mentoring capabilities of your most experienced employees. Just because someone is an expert in part of your business doesn’t mean they can teach others about it.

Shoshana Zuboff writes, “Learning is the new form of labor.” This is certainly true, but every major change brings unintended consequences. The problem of learning overload in high-skilled jobs is going to get worse, given advances in technology, the increased availability of knowledge, and the relentless drive for performance improvements. The failure to address this phenomenon will have costly impacts: increased risk of burnout, reduced productivity, and time wasted on the wrong tasks. Awareness of the presence and costs of learning overload are the first step to meeting this new challenge.

[image error]

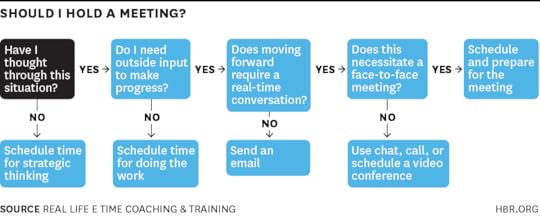

Do You Really Need to Hold That Meeting?

“Let’s schedule a meeting” has become the universal default response to most business issues. Not sure what to do on a project? Let’s schedule a meeting. Have a few ideas to share? Let’s schedule a meeting. Struggling with taking action? Let’s schedule a meeting.

Although scheduling a meeting can be the right solution in many instances, it’s not always the best answer. I’ve come up with a decision tree to help you quickly determine if a meeting makes the most sense.

Save or print out this decision tree to make deciding whether or not to hold a meeting as quick and easy as possible. As you go through it, here’s what you should consider at each step:

Have I thought through this situation? When you don’t have clarity about what you’re doing on a project, it’s tempting to schedule a meeting to give you the feeling of progress. But unless the meeting’s intent is to structure the project, at this point, scheduling a meeting is an inefficient use of your time — and your colleagues’. Instead, set aside some time with yourself to do some strategic thinking. During that time you can evaluate the scope of the project, the current status, the potential milestones, and lay out a plan of action for making meaningful progress. Once you’ve completed your own strategic thinking prep work, then you can move onto the next step of considering whether to hold a meeting.

Do I need outside input to make progress? You may be in the situation where you know what needs to be done, and you simply need to do the work. If you find yourself in this place, don’t schedule a meeting; update your to-do list and take action instead. However, if after clarifying what needs to be done to the best of your ability, you need outside input to answer questions or give feedback before you feel comfortable jumping into action, continue on.

Further Reading

Running Meetings (20-Minute Manager Series)

Managing People Book

12.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Does moving forward require a real-time conversation? If you need some answers to questions, but they don’t require a two-way conversation, e-mail can be an excellent option in lieu of a meeting. This is particularly true when you’re looking for feedback on your written plans or documents. It’s much more efficient for everyone involved if you send over items that they can look at on their own (while you’re not awkwardly watching them read during an in-person meeting) and then shoot you back feedback. If you feel your situation does require a real-time conversation, then examine different communication channels.

Does this necessitate a face-to-face meeting? When you need two-way communication but don’t necessarily need to see the person, you have a variety of options. An online chat can help you answer questions quickly, or for more in-depth conversations, scheduling a phone call or video conference can work well. This not only saves you transition time of going to and from a meeting place, but you will more easily able to get stuff done if someone is late, instead of having to sit and wait for them to show up.

If in the end, you decide that you need face-to-face, in-person communication, then schedule a meeting, and think through in advance how you can make it as efficient and effective as possible. That means considering your intent for the meeting, establishing your desired outcomes, and preparing any materials that you should review or send out in advance.

With the right decision-making process, you can radically reduce the number of meetings you attend and increase the amount of work that gets done.

[image error]

Why Remote Work Thrives in Some Companies and Fails in Others

Photo by Dietmar Becker

Since people began telecommuting decades ago, companies have been excited about the prospects to increase productivity, reduce costs, and gain access to a much larger talent pool.

But has remote work lived up to the hype? In some organizations, yes. Automattic (the creator of WordPress) and the U.S. government are two good — and very different — examples.

A completely distributed company born out of the open-source movement, Automattic doesn’t make anyone come to the office — and most of its employees choose not to. They’re given state-of-the-art technology, $2,000 to build a home office, and a large travel budget so they can meet up with other team members twice a year in beautiful, exciting places such as La Paz, Mexico, and Amsterdam. Ultimately, these perks help the company source the best talent, which is often found outside large technology hubs like Silicon Valley and New York.

In the U.S. government, though adoption varies by department, the Office of Personnel Management reports that remote work has increased job satisfaction, reduced employee turnover, and cut costs on several fronts, including real estate, utilities, and travel subsidies.

Elsewhere, though, it’s been a different story. Marissa Mayer famously declared the end of remote work at Yahoo! about two years ago, citing the need to improve the “speed and quality” and benefit from the “decisions and insights [that] come from hallway and cafeteria discussions.” In the wake of her controversial decision, several high-profile companies — including Best Buy and Reddit — followed suit.

Why are some organizations reaping benefits but others not? Conditions are seemingly ideal: More and more people are choosing to work remotely. By one estimate, the number of remote workers in the U.S. grew by nearly 80% between 2005 and 2012. Advances in technology are keeping pace. About 94% of U.S. households have access to broadband Internet — one of the most important enablers of remote work. Workers also have access to an array of tools that allow them to videoconference, collaborate on shared documents, and manage complex workflows with colleagues around the world.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

So what’s the problem? The answer is simple: Many companies focus too much on technology and not enough on process. This is akin to trying to fix a sports team’s performance by buying better equipment. These adjustments alone might result in minor improvements, but real change requires a return to fundamentals.

Successful remote work is based on three core principles: communication, coordination, and culture. Broadly speaking, communication is the ability to exchange information, coordination is the ability to work toward a common goal, and culture is a shared set of customs that foster trust and engagement. In order for remote work to be successful, companies (and teams within them) must create clear processes that support each of these principles.

Communication. In a virtual environment, it can be difficult to explain complex ideas, especially if people aren’t able to ask questions and have discussions in real time. The lack of face-to-face interaction limits social cues, which may lead to misunderstandings and conflict.

In one of my company’s workshops, we use this simple exercise to illustrate some of the pitfalls: After dividing participants into groups of three, we show one team member an image and ask him or her to describe it to another team member over the phone (without naming it outright). That person, based on the description, e-mails the third team member with instructions on how to recreate the image. As you can imagine, this produces a lot of laughs — and a lot of strange drawings.

The way to avoid miscues and misinterpretation is to match the message with the medium. To effectively share information that is complex or personal, you often need to observe body language, hear tone and inflection, and be able to see what you’re talking about. For those purposes videoconferencing is the next best thing to talking face-to-face. At the other end of the spectrum, small, non-urgent requests are best suited to e-mail, instant messaging, or all-in-one platforms like Slack. Although this seems commonsensical, many people instinctively default to their preferred method of communication, which can lead to misunderstandings, conflict, and lost productivity.

Frequency of communication also matters. Providing regular updates, responding to messages promptly, and being available at important times (especially when colleagues are located in different time zones) reduces the likelihood of roadblocks and builds trust.

Although communication happens at the individual level, companies can establish norms and provide training for their employees. The CEO of El Mejor Trato, an Argentine travel comparison site, went even further and banned e-mail for internal communications. In its place, he provided custom project management software. Employees resisted at first, but after a three-month trial period, they were hooked.

Coordination. At times, coordinating remote workers can feel like choreographing a troupe of blindfolded synchronized swimmers. Everyone should be working in harmony, but people often don’t know what others are doing and how everything fits together into a larger routine.

That’s why it’s important to create formal processes that simulate the informal ways we touch base when we are physically collocated — stopping by a colleague’s desk, for example, or eating lunch together. These interactions serve as course corrections. In their absence, it’s much more likely that people will wander astray.

To mitigate this problem, which is compounded when the entire team is virtual, managers should not only clearly articulate the mission, assign roles and responsibilities, create detailed project plans, and establish performance metrics — they should also document all that in a repository that’s easily accessed offsite. There are plenty of tools that will help you with coordination, such as Basecamp and Asana, but you also need to be disciplined about keeping documents up-to-the-minute — and that’s where process comes into play. Teams must know how and when individuals should provide updates, review deliverables, and make decisions.

Merely having processes isn’t enough. Managers must model and enforce them until they are completely assimilated. They also need to evaluate team members on how well they adhere to protocol. Otherwise, they’ll revert to old habits. It might be easier to send a quick e-mail to say a task is almost finished, for example, but people will inevitably get left out of the loop. Operating outside the established processes will undermine the team’s cohesion.

Culture. This principle is especially critical for virtual teams but also important for individuals who work remotely. Since these folks rarely meet with their teammates face-to-face, they tend to focus on tasks and ignore the team. This may work for a while, but you must develop a culture in order to foster engagement and sustain their performance over the long term.

The first step is establishing trust. Addressing communication and coordination problems will shore up cognitive trust (based on competence and reliability). But affective trust (based on feeling) is trickier to build virtually — you may need to bring team members together for short periods of time.

GitHub, which makes a platform for collaborating on software development, brings its entire team together once a year for this purpose. It also requires new hires to spend their first week in its San Francisco headquarters so they develop an understanding of the company’s culture. GitHub also rallies around its online platform with rituals that feed the culture and provide recognition for employees. One example is its #toasts forum, which functions as a virtual water cooler. Employees post major accomplishments to the forum, and colleagues from around the world post selfies toasting them — though they’re usually not drinking water. In the end, these photographs are made into a short video and uploaded to a shared repository. (To see this in action, check out this talk by a GitHub employee, at 15:25.) For remote workers located around the world, this type of quirky activity provides a connection to colleagues and to the company’s unique culture.

If in-person meetings aren’t possible and a virtual water cooler seems contrived, you can schedule regular informal calls — either one-on-one or as a group. They may not be as effective as spending time together in person, but they have the same objectives: to recognize remote team members as human beings, understand how they are feeling, and learn about their lives outside the office. It may feel awkward at first, but building a shared identity and personal connections will lead to greater engagement and better performance.

Implementing remote work successfully is difficult; it requires a thoughtful strategy and reliable execution. But when it’s done well, the reward is high: increased productivity, happier employees, and cost savings (which you can invest into building a better business). With major shifts in the workplace, such as the large increase in Millennials and the fading line between work and life, remote work will become an even more critical tool for recruitment and employee engagement. Companies like Yahoo! can try to reverse the trend, but they’re better off reevaluating what issues led them to ban remote work and putting the right processes in place to address them.

[image error]

Few Companies Actually Succeed at Going Global

We all like to learn from the best. So when it comes to growth it’s tempting to take global high-performers like GE, IBM, Shell, or BMW as role models and look for opportunities outside the home markets.

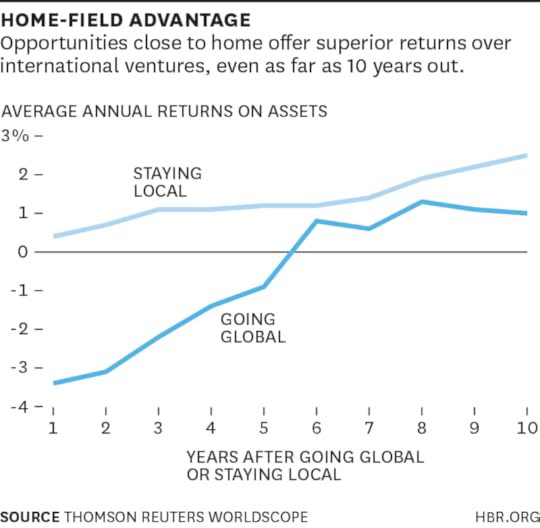

The trouble is that these global role models are much easier to admire than to imitate. In an analysis of 20,000 companies in 30 countries, we found that companies selling abroad had an average Return on Assets (ROA) of minus 1% as long as five years after their move. It takes 10 years to reach a modest +1% and only 40% of companies turn in more than 3%.

A look at Devon, a mid-size U.S. oil and gas producer, illustrates why international expansion produces such low numbers for so many companies. In 1999 Devon acquired PenzEnergy and in 2000 Santa Fe Snyder. The two deals gave it access to operations in Azerbaijan, West Africa, and Brazil.

After making some initial investments in these oil fields Devon eventually realized that it lacked the scale to absorb the risks that came with them. When approvals for environmental permits were delayed in Brazil, for example, the company was forced to incur rental costs on drilling equipment that it could not deploy to alternative fields and was forced to take a capital hit that a firm its size could ill afford. In 2009, Devon therefore sold off all of its foreign assets and used the proceeds to invest heavily in booming shale development in the U.S.

Global expansion is also more complicated to manage. In the 1990s Boise Cascade, a large, vertically integrated wood-products manufacturer in the U.S., decided to expand to Brazil, where it acquired timberlands and built a new mill.

Operating in Brazil, however, turned out to be much more difficult than expected because of regulatory, political, and cultural differences. Management attention, including frequent trips to Brazil, took far more time than for similar plants at home. While Boise was able to make the business profitable after a few years, the profits were not high enough to justify the added investment needed and the disproportionate drain on top management time. In 2008 Boise threw in the towel and sold the Brazilian operation to a local paper company for $47 million.

The lesson to be drawn from these experiences is that most companies should not treat international expansion as a default growth option. Like diversification it comes with many challenges. Few companies have the size or management capabilities to make a success of going overseas and for most it may well be more profitable to look closer to home.

Look at the data. We found that companies in our database that expanded domestically typically had an average ROA of +1% after five years, rising to +2.4% after 10 years, with 53% exceeding 3%.

And companies can excel without going abroad: although the global giants like GE, IBM, Shell, and BMW are undeniably high-performers, a full third of the top 10% ROA performers in our database conduct almost no international business.

[image error]

March 19, 2015

Artificial Intelligence Is Almost Ready for Business

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is an idea that has oscillated through many hype cycles over many years, as scientists and sci-fi visionaries have declared the imminent arrival of thinking machines. But it seems we’re now at an actual tipping point. AI, expert systems, and business intelligence have been with us for decades, but this time the reality almost matches the rhetoric, driven by the exponential growth in technology capabilities (e.g., Moore’s Law), smarter analytics engines, and the surge in data.

Most people know the Big Data story by now: the proliferation of sensors (the “Internet of Things”) is accelerating exponential growth in “structured” data. And now on top of that explosion, we can also analyze “unstructured” data, such as text and video, to pick up information on customer sentiment. Companies have been using analytics to mine insights within this newly available data to drive efficiency and effectiveness. For example, companies can now use analytics to decide which sales representatives should get which leads, what time of day to contact a customer, and whether they should e-mail them, text them, or call them.

Such mining of digitized information has become more effective and powerful as more info is “tagged” and as analytics engines have gotten smarter. As Dario Gil, Director of Symbiotic Cognitive Systems at IBM Research, told me:

“Data is increasingly tagged and categorized on the Web – as people upload and use data they are also contributing to annotation through their comments and digital footprints. This annotated data is greatly facilitating the training of machine learning algorithms without demanding that the machine-learning experts manually catalogue and index the world. Thanks to computers with massive parallelism, we can use the equivalent of crowdsourcing to learn which algorithms create better answers. For example, when IBM’s Watson computer played ‘Jeopardy!,’ the system used hundreds of scoring engines, and all the hypotheses were fed through the different engines and scored in parallel. It then weighted the algorithms that did a better job to provide a final answer with precision and confidence.”

Beyond the Quants

Interestingly, for a long time, doing detailed analytics has been quite labor- and people-intensive. You need “quants,” the statistically savvy mathematicians and engineers who build models that make sense of the data. As Babson professor and analytics expert Tom Davenport explained to me, humans are traditionally necessary to create a hypothesis, identify relevant variables, build and run a model, and then iterate it. Quants can typically create one or two good models per week.

However, machine learning tools for quantitative data – perhaps the first line of AI – can create thousands of models a week. For example, in programmatic ad buying on the Web, computers decide which ads should run in which publishers’ locations. Massive volumes of digital ads and a never-ending flow of clickstream data depend on machine learning, not people, to decide which Web ads to place where. Firms like DataXu use machine learning to generate up to 5,000 different models a week, making decisions in under 15 milliseconds, so that they can more accurately place ads that you are likely to click on.

Tom Davenport:

“I initially thought that AI and machine learning would be great for augmenting the productivity of human quants. One of the things human quants do, that machine learning doesn’t do, is to understand what goes into a model and to make sense of it. That’s important for convincing managers to act on analytical insights. For example, an early analytics insight at Osco Pharmacy uncovered that people who bought beer also bought diapers. But because this insight was counter-intuitive and discovered by a machine, they didn’t do anything with it. But now companies have needs for greater productivity than human quants can address or fathom. They have models with 50,000 variables. These systems are moving from augmenting humans to automating decisions.”

In business, the explosive growth of complex and time-sensitive data enables decisions that can give you a competitive advantage, but these decisions depend on analyzing at a speed, volume, and complexity that is too great for humans. AI is filling this gap as it becomes ingrained in the analytics technology infrastructure in industries like health care, financial services, and travel.

The Growing Use of AI

IBM is leading the integration of AI in industry. It has made a $1 billion investment in AI through the launch of its IBM Watson Group and has made many advancements and published research touting the rise of “cognitive computing” – the ability of computers like Watson to understand words (“natural language”), not just numbers. Rather than take the cutting edge capabilities developed in its research labs to market as a series of products, IBM has chosen to offer a platform of services under the Watson brand. It is working with an ecosystem of partners who are developing applications leveraging the dynamic learning and cloud computing capabilities of Watson.

The biggest application of Watson has been in health care. Watson excels in situations where you need to bridge between massive amounts of dynamic and complex text information (such as the constantly changing body of medical literature) and another mass of dynamic and complex text information (such as patient records or genomic data), to generate and evaluate hypotheses. With training, Watson can provide recommendations for treatments for specific patients. Many prestigious academic medical centers, such as The Cleveland Clinic, The Mayo Clinic, MD Anderson, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering are working with IBM to develop systems that will help healthcare providers better understand patients’ diseases and recommend personalized courses of treatment. This has proven to be a challenging domain to automate and most of the projects are behind schedule.

Another large application area for AI is in financial services. Mike Adler, Global Financial Services Leader at The Watson Group, told me they have 45 clients working mostly on three applications: (1) a “digital virtual agent” that enables banks and insurance companies to engage their customers in a new, personalized way, (2) a “wealth advisor” that enables financial planning and wealth management, either for self-service or in combination with a financial advisor, and (3) risk and compliance management.

For example, USAA, the $20 billion provider of financial services to people that serve, or have served, in the United States military, is using Watson to help their members transition from the military to civilian life. Neff Hudson, vice president of emerging channels at USAA, told me, “We’re always looking to help our members, and there’s nothing more critical than helping the 150,000+ people leaving the military every year. Their financial security goes down when they leave the military. We’re trying to use a virtual agent to intervene to be more productive for them.” USAA also uses AI to enhance navigation on their popular mobile app. The Enhanced Virtual Assistant, or Eva, enables members to do 200 transactions by just talking, including transferring money and paying bills. “It makes search better and answers in a Siri-like voice. But this is a 1.0 version. Our next step is to create a virtual agent that is capable of learning. Most of our value is in moving money day-to-day for our members, but there are a lot of unique things we can do that happen less frequently with our 140 products. Our goal is to be our members’ personal financial agent for our full range of services.”

In addition to working with large, established companies, IBM is also providing Watson’s capabilities to startups. IBM has set aside $100 million for investments in startups. One of the startups that is leveraging Watson is WayBlazer, a new venture in travel planning that is led by Terry Jones, a founder of Travelocity and Kayak. He told me:

“I’ve spent my whole career in travel and IT. I started as a travel agent, and people would come in, and I’d send them a letter in a couple weeks with a plan for their trip. The Sabre reservation system made the process better by automating the channel between travel agents and travel providers. Then with Travelocity we connected travelers directly with travel providers through the Internet. Then with Kayak we moved up the chain again, providing offers across travel systems. Now with WayBlazer we have a system that deals with words. Nobody has helped people with a tool for dreaming and planning their travel. Our mission is to make it easy and give people several personalized answers to a complicated trip, rather than the millions of clues that search provides today. This new technology can take data out of all the silos and dark wells that companies don’t even know they have and use it to provide personalized service.”

What’s Next

As Moore’s Law marches on, we have more power in our smartphones than the most powerful supercomputers did 30 or 40 years ago. Ray Kurzweil has predicted that the computing power of a $4,000 computer will surpass that of a human brain in 2019 (20 quadrillion calculations per second). What does it all mean for the future of AI?

To get a sense, I talked to some venture capitalists, whose profession it is to keep their eyes and minds trained on the future. Mark Gorenberg, Managing Director at Zetta Venture Partners, which is focused on investing in analytics and data startups, told me, “AI historically was not ingrained in the technology structure. Now we’re able to build on top of ideas and infrastructure that didn’t exist before. We’ve gone through the change of Big Data. Now we’re adding machine learning. AI is not the be-all and end-all; it’s an embedded technology. It’s like taking an application and putting a brain into it, using machine learning. It’s the use of cognitive computing as part of an application.” Another veteran venture capitalist, Promod Haque, senior managing partner at Norwest Venture Partners, explained to me, “if you can have machines automate the correlations and build the models, you save labor and increase speed. With tools like Watson, lots of companies can do different kinds of analytics automatically.”

Manoj Saxena, former head of IBM’s Watson efforts and now a venture capitalist, believes that analytics is moving to the “cognitive cloud” where massive amounts of first- and third-party data will be fused to deliver real-time analysis and learning. Companies often find AI and analytics technology difficult to integrate, especially with the technology moving so fast; thus, he sees collaborations forming where companies will bring their people with domain knowledge, and emerging service providers will bring system and analytics people and technology. Cognitive Scale (a startup that Saxena has invested in) is one of the new service providers adding more intelligence into business processes and applications through a model they are calling “Cognitive Garages.” Using their “10-10-10 method” they deploy a cognitive cloud in 10 seconds, build a live app in 10 hours, and customize it using their client’s data in 10 days. Saxena told me that the company is growing extremely rapidly.

I’ve been tracking AI and expert systems for years. What is most striking now is its genuine integration as an important strategic accelerator of Big Data and analytics. Applications such as USAA’s Eva, healthcare systems using IBM’s Watson, and WayBlazer, among others, are having a huge impact and are showing the way to the next generation of AI.

[image error]

Convincing Skeptical Employees to Adopt New Technology

Bringing new technology and tools into your organization can increase productivity, boost sales, and help you make better, faster decisions. But getting every employee on board is often a challenge. What can you do to increase early and rapid adoption? How can you incentivize and reward employees who use it? And should you reprimand those who don’t?

What the Experts Say

According to a study by MIT Sloan Management Review and Capgemini Consulting, the vast majority of managers believe that “achieving digital transformation is critical” to their organizations. However, 63% said the pace of technological change in their workplaces is too slow, primarily due to a “lack of urgency” and poor communication about the strategic benefits of new tools. “Employees need to understand why [the new technology] is an improvement from what they had before,” says Didier Bonnet, coauthor of Leading Digital and Global Practice Leader at Capgemini Consulting, who worked on the research and coauthored the study. “The job of a manager is to help people cross the bridge — to get them comfortable with the technology, to get them using it, and to help them understand how it makes their lives better.”

Leaders should expect to face luddites, people who aren’t naturally tech-savvy, and naysayers whose knee-jerk reaction is to oppose new things. “There are always some people who have their routines, and they just don’t want to change,” says Michael C. Mankins, a partner in Bain & Company’s San Francisco office and the leader of the firm’s organization practice in the Americas. “That [attitude] persists as long as the organization permits it.” Here are some ideas for encouraging the adoption of a new technology.

Choose technology wisely

When you’re shopping around for a new technology — be it a customer relationship management (CRM) program or software to better manage employee timesheets — bear your team’s interests in mind. Functionality is critical, but so is user-friendliness. “If your goal is a high adoption rate within the organization, make sure you’re choosing the most approachable, most intuitive system possible,” says Mankins. Technologies that require multi-day training programs and hefty user manuals are a surefire recipe for employee bellyaching and a stalled adoption. Bonnet suggests running “comparative pilots” of various technologies to ensure you’re choosing the right one. “Encourage your team to do trials, get feedback from users, and learn from that before you take the jump,” he says.

State your case

Persuading your team to adopt a new technology requires putting forth a “compelling vision for what the technology is and what it’s going to do,” says Bonnet. First, you must demonstrate the new service offers “economic and rational benefits for the organization and the individual,” says Mankins. Perhaps it will help the company quantify its marketing efforts; maybe it will enable employees to track customer data more easily. Help employees understand what’s in it for them, he adds. Will it enable salespeople to meet their quotas faster — which gives them the opportunity to make more money? Or increase productivity in a way that reduces weekend work? The best argument for a new technology is “that it will make your life better,” Mankins explains.

Customize training

Because “familiarity with and interest in digital technology varies widely” among employees, your training efforts should reflect those differences, says Bonnet. Some employees might prefer an online training session; others might need a bit more handholding and support in the form of a personal coach. “You don’t want to send people who are tech-savvy on a course because that’s a waste of time,” he says. “Instead, ask your team members what kind of training they’re most comfortable with.” During the instruction phase, it’s important that you “lead by example,” he adds. “Show that you are investing time in learning the new system. Show your humility and empathize with your team” about the challenges you’re all facing.

Get influencers onboard

In the early stages of the launch, focus on getting “a network of champions” fully invested in the new technology, so they can “coach others on how to use the tools to their benefit,” says Bonnet. This “group of evangelists” should “replicate the organization” and include your star performers. “Don’t just pick the geeks – those who are most interested in technology,” says Bonnet. “You want people who are able to work horizontally across the organization and who have good communication and networking skills.” “It’s most important not that early adopters adopt, but that influencers adopt,” Mankins emphasizes. “Getting those folks on board early is critical.”

Make it routine

As soon as reasonably possible, try to “institutionalize” the new technology and “show employees that you are transitioning from the old way of working to the new one,” says Bonnet. Make the technology “part of the routine of the way the place works,” adds Mankins. If, for instance, you’ve recently introduced a new sales-tracking technology, start asking for weekly updates on the numbers. Of course, employees could still use provide the information without using the new system, but it would be more cumbersome and time-consuming. The goal, says Mankins, is to “implicitly raise the cost of not using the new technology.”

Highlight quick wins

Once employees begin to use the technology more and more, draw attention to the positive impact it’s having on your organization. “Publicizing quick wins helps build a case for change” and encourages further adoption, says Mankins. Emphasize individual gains, too. “Say, ‘Ted uses this technology and he’s been able to retire his quota in 10 months rather than a year,’” says Mankins. Depending on the size and scale of the rollout, you might consider enlisting help in getting the word out about the early successes. “Leverage [your company’s] marketing department to communicate and disseminate that message.”

Make it fun

“Rewarding the behavior you want to see is much more effective than penalizing the behavior you don’t want to see,” says Mankins. You’ll need to know “which employees are adopting the technology and which kind of rewards means the most to them.” Is it compensation, perks, recognition, or the ability to innovate faster? Bonnet suggests experimenting with gamification to “make it fun and create a bit of buzz around the technology and motivate and engage people.” Employees might accumulate points, gain financial incentives, or achieve new levels of “status.”

Consider penalties

If you’re still having a hard time getting your team on board, consider instituting penalties for non-use. “It depends on how damaging it is to the organization to have resistors,” says Bonnet. “At a certain point, [lack of adoption] becomes an issue of productivity and the bottom line.” Let’s say, for instance, members of your sales team are especially resistant to the new technology. Mankins suggests telling them that only data entered into the new system will count toward their quota.” He adds that, although penalties like these can be effective, they should be used as a last resort. “They’re a blunt instrument,” he explains, “and they reinforce the notion that the new technology is a hassle.”

Principles to Remember

Do

Win hearts and minds by emphasizing how the new technology benefits the organization and makes employees’ lives easier

Encourage adoption by rewarding employees in ways that are most meaningful to them

Build the new technology into the routines and rhythms of the workday as soon as possible

Don’t

Pick a technology that’s more complicated than it needs to be; for a swift adoption, select a system that’s approachable and intuitive

Overlook the importance of getting your most influential employees on board early in the process; they will help you bring around others

Leap to punish employees who don’t use the technology; penalties should be a last resort if incentives and rewards aren’t working

Case Study #1: Focus on communication and training

Jill Mizrachy, a senior director at Booz Allen Hamilton and a senior associate in learning development at the firm, acknowledges that it’s a challenge to introduce new technologies to employees. “Folks are more and more dispersed,” she says, “and we have younger people who’ve grown up with the internet as well as older team members who are less comfortable with new technology.”

When Booz Allen began rolling out its new cloud-based computer system (internally known as “The Zone”), Jill knew that high-quality communication and training would be critical.

She first enlisted the help of a colleague in communications to assist her with messaging. “We wanted to explain what’s changing, what’s in it for them, and we wanted to create a ‘cool factor,’” she explains. “The biggest questions we get from people are, ‘How does this affect me?’ and ‘How will it change the way I work?’”

Before the launch, Jill also ran early sessions with a variety of senior employees from different departments, and geographies. They became a “cadre of ambassadors,” who could help get other employees comfortable with the new technology.

During launch week, the group stood in the lobbies of their respective offices to greet employees and hand out pamphlets with links to the new system and tips on how to use it.

Employees were able to choose from a variety of training options, including regularly scheduled live demonstrations of the new system, online recordings of those live demonstrations and an interactive social media tool where they could pose questions to an expert in real time.

So far, employee adoption of The Zone is proceeding at a steady pace. “This is Phase One and there’s more to come,” Jill says. “There’s a lot of excitement about it.”

Case Study #2: Gamify adoption to make it fun and engaging

A few years ago, William Vanderbloemen, the founder and CEO of Vanderbloemen Search Group — which specializes in executive recruitment for large and mid-sized churches — wanted to implement a new technology that would help his organization improve sales.

Bearing in mind his employees’ technological know-how, he researched his options then spent a few months test-driving them. He finally settled on Hubspot, the inbound marketing software that helps businesses generate sales leads through the creation of website content. “When I saw how intuitive it was and how seamlessly it interfaced with Salesforce [his firm’s CRM platform], I was sold,” he explains. “I wanted to sell others, too.”

His first priorities involved laying out “a vision for the future” and providing an explanation for how the new technology would improve the business. “I told [my team] that the days of cold calling and door-to-door salesmen were dead. I told them that there was a seismic shift happening in communication and marketing and that we had an opportunity to be on the front end,” he says.

With only five employees at the time, he decided against a formal training program. Instead, his team members learned how to use it by shadowing him. “They learned by osmosis,” he says. “I wanted to lead by example and show them that I was involved and that we were in this together.”

As the organization grew and began hiring more people who needed to use Hubspot, William instituted a contest to encourage fast adoption. The employee who generated the most internet traffic from a single piece of online content over a month-long period won two first-class airline tickets anywhere in the U.S. “It was a way to make it fun for people and also a way for us to unearth the folks we didn’t know were experts,” he says. “Now I have those people teaching others how to do it.”

[image error]

Dealing with the Unique Work-Life Challenges of Family Businesses

Howard is the brilliant and overpowering founder of a billion dollar vehicle business who pressed his elder son into the business. The son is himself a brilliant man who wished to be a physicist but, overwhelmed by a sense of duty to his father, studied business in college and then entered the family firm. His father demanded absolute commitment to the business, forcing his son to be “all in” and to follow the career path set down for him in early adolescence.

Howard didn’t allow his son to carve out any personal space for himself; there was no pretense of a work-life balance. Relations grew tense, and things finally blew up after a board meeting when Howard skewered his son’s wife behind her back. Tearful, Howard’s son quit the company, and for years stayed “all out” of the business, remaining part of the family, but harboring bitter resentments toward his father and everything to do with the family business.

Being “all in” or “all out” are two unproductive ways of finding a work-life balance in a family business. Neither alternative allows the family member room to sculpt a satisfying role in the family business system. Of course, finding a balance is difficult in a publicly-traded company, too, but in a family business the boundary between professional and personal lives is often fuzzy.

There is a third way, but it isn’t easy. Consider Charles, Howard’s younger son. Even before his brother exited the business, Charles entered it. Unlike his older brother, however, Charles has stayed and manages to survive and thrive. Significantly, he converted to a new religion in his early 20s despite his father’s vociferous objections. Although his religious choice was much more profound than a simple decision to establish a boundary between himself and the business, Charles’s religious identity separates him from his father. For example, he observes the Sabbath, effectively setting down concrete limits on how much the family business can encroach on his private time.

In one of the most powerful meetings that we have ever witnessed in a family setting, Charles told his father, “Don’t force me to choose between my religion and the chance to run this business because I’ll choose my religion.” His father had to respect the boundary that Charles had unilaterally imposed, or watch his younger son walk away.

By setting a boundary that his father honored, Charles found a way to live in both worlds — his own and that of the family business. The extreme boundary that he imposed also illustrates the difficulty that he faced in drawing a line between his love for his family and his personal need for some private space.

We see clients caught all the time on the horns of this dilemma. However much they love and support one another, even the closest family members find it difficult to live and work together all their lives. As one of our clients, the gifted CFO of a large manufacturing company, said when he quit the business, “I can’t continue going through life always being the younger brother.” His identity as a family member undermined his professional growth and effectiveness as CFO. When people are not allowed to be their “own person” in a family business, the tragedy is that both the family and the business lose out.

Here are some solutions that client families have come up with to find a reasonable middle way between the extremes of “all in” or “all out” in their search for a work-life balance:

Separate family time from work time. Something common to all our clients is that they are passionate about their work, sometimes to the point of being obsessive. One Latin American business family, for example, held weekly Sunday family lunches, but all the men sat at one table; all the women sat at another. The men talked business, and the meal turned into a de facto board meeting. At the time, the business didn’t have a board. A part of the solution was to create a disciplined, formal board – to establish a space and appropriate times for them to have business conversations. The other part of the solution was intentionally to draw a line between family and work. To take business off the table on Sundays, the matriarch mixed up the men and women by imposing formal seating arrangements. Though artificial at first, family members eventually mingled freely.

Use your work voice. In successful family businesses, family members learn to talk to one another as business partners and not as siblings or cousins. These family members implement certain rules that seem obvious, but which are not always practiced: Listen actively. Don’t interrupt when others speak. Ask for clarification when you don’t understand the other person’s point of view. Participate equally. This business-like communication style veers sharply from the free-for-all exchanges that go on in many families. Indeed, establishing a boundary between the personal and the professional in a family business really involves being more careful about how things are said rather than what is actually said.

Create healthy silos. Very often silos are disparaged as poor management practice. Indeed, they can cause problems when it comes to succession or when boundaries cut across customer needs or reduce operational efficiencies. But the vast majority of successful family businesses establish silos with clear roles: “I’m the Head of Retail, you’re the Head of the Textile Division.” Silos can be boundaries that prevent the confusion of responsibilities and authority that so often plagues a family business system. Silos have the added advantage of giving family members something that they can call their own.

Recognize the value of financial independence. In business families where wealth can be substantial, friction often develops between the robustness of the business and the financial dependence of family members. We know of one family where the siblings are now in their fifties and sixties, and they still rely on the matriarch for their “allowance.” The healthiest business families are those where parents respect the separate financial interests of the next generation, which isn’t easy. If the adult children or nephews and nieces aren’t responsible about money, then they will become more, not less, dependent on the older generation. But without establishing some boundary between what belongs to the business and what the individual family members want, need, and are accountable for, people remain beholden to the business in a way that breeds frustration and discontent. Without fiscal autonomy, a work-life balance cannot exist in a family business.

Create an identity outside the family business. Business families often have strong ties to the community, and their identity and status are deeply bound up with it. Yet an individual’s identity can get subsumed under the family’s prestige and stature in the outside world. While status confers many advantages, it’s important for family members to find a place in society where they can create an identity unrelated to the family. Charles finds that place in his religious community, where he feels that people don’t care about his last name. To them, he is just Charles, and that’s the way he manages to achieve a work-life balance in a very successful and demanding family business.

Some of the identifying details in this article have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

[image error]

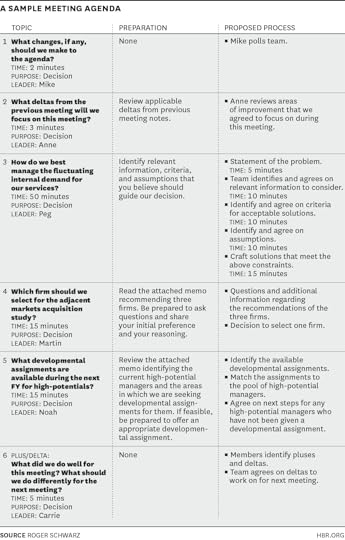

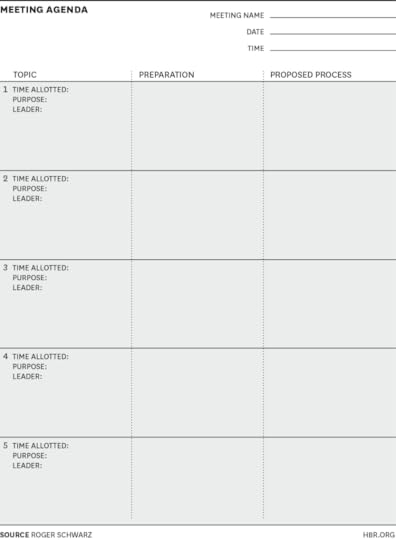

How to Design an Agenda for an Effective Meeting

We’ve all been in meetings where participants are unprepared, people veer off-track, and the topics discussed are a waste of the team’s time. These problems — and others like it — stem from poor agenda design. An effective agenda sets clear expectations for what needs to occur before and during a meeting. It helps team members prepare, allocates time wisely, quickly gets everyone on the same topic, and identifies when the discussion is complete. If problems still occur during the meeting, a well-designed agenda increases the team’s ability to effectively and quickly address them.

You and Your Team

Meetings

How to make them more productive.

Here are some tips for designing an effective agenda for your next meeting, with a sample agenda and template below. You can use these tips whether a meeting lasts an hour or three days and whether you’re meeting with a group of five or forty:

Seek input from team members. If you want your team to be engaged in meetings, make sure the agenda includes items that reflect their needs. Ask team members to suggest agenda items along with a reason why each item needs to be addressed in a team setting. If you ultimately decide not to include an item, be accountable — explain your reasoning to the team member who suggested it.

Select topics that affect the entire team. Team meeting time is expensive and difficult to schedule. It should mainly be used to discuss and make decisions on issues that affect the whole team — and need the whole team to solve them. These are often ones in which individuals must coordinate their actions because their parts of the organization are interdependent. They are also likely to be issues for which people have different information and needs. Examples might include: How do we best allocate shared resources? How do we reduce response time? If the team isn’t spending most of the meeting talking about interdependent issues, members will disengage and ultimately not attend.

List agenda topics as questions the team needs to answer. Most agenda topics are simply several words strung together to form a phrase, for example: “office space reallocation.” This leaves meeting participants wondering, “What about office space reallocation?” When you list a topic as a question (or questions) to be answered, it instead reads like this: “Under what conditions, if any, should we reallocate office space?”

A question enables team members to better prepare for the discussion and to monitor whether their own and others’ comments are on track. During the meeting, anyone who thinks a comment is off-track can say something like, “I’m not seeing how your comment relates to the question we’re trying to answer. Can you help me understand the connection?” Finally, the team knows that when the question has been answered, the discussion is complete.

Note whether the purpose of the topic is to share information, seek input for a decision, or make a decision. It’s difficult for team members to participate effectively if they don’t know whether to simply listen, give their input, or be part of the decision making process. If people think they are involved in making a decision, but you simply want their input, everyone is likely to feel frustrated by the end of the conversation. Updates are better distributed — and read — prior to the meeting, using a brief part of the meeting to answer participants’ questions. If the purpose is to make a decision, state the decision-making rule. If you are the formal leader, at the beginning of the agenda item you might say, “If possible, I want us to make this decision by consensus. That means that everyone can support and implement the decision given their roles on the team. If we’re not able to reach consensus after an hour of discussion, I’ll reserve the right to make the decision based on the conversation we’ve had. I’ll tell you my decision and my reasoning for making it.”

Estimate a realistic amount of time for each topic. This serves two purposes. First, it requires you to do the math — to calculate how much time the team will need for introducing the topic, answering questions, resolving different points of view, generating potential solutions, and agreeing on the action items that follow from discussion and decisions. Leaders typically underestimate the amount of time needed. If there are ten people in your meeting and you have allocated ten minutes to decide under what conditions, if any, you will reallocate office space, you have probably underestimated the time. By doing some simple math, you would realize that the team would have to reach a decision immediately after each of the ten members has spoken for a minute.

Second, the estimated time enables team members to either adapt their comments to fit within the allotted timeframe or to suggest that more time may be needed. The purpose of listing the time is not to stop discussion when the time has elapsed; that simply contributes to poor decision making and frustration. The purpose is to get better at allocating enough time for the team to effectively and efficiently answer the questions before it.

Propose a process for addressing each agenda item. The process identifies the steps through which the team will move together to complete the discussion or make a decision. Agreeing on a process significantly increases meeting effectiveness, yet leaders rarely do it. Unless the team has agreed on a process, members will, in good faith, participate based on their own process. You’ve probably seen this in action: some team members are trying to define the problem, other team members are wondering why the topic is on the agenda, and still other members are already identifying and evaluating solutions.

The process for addressing an item should appear on the written agenda. When you reach that item during the meeting, explain the process and seek agreement: “I suggest we use the following process. First, let’s take about 10 minutes to get all the relevant information on the table. Second, let’s take another 10 minutes to identify and agree on any assumptions we need to make. Third, we’ll take another 10 minutes to identify and agree on the interests that should be met for any solution. Finally, we’ll use about 15 minutes to craft a solution that ideally takes into account all the interests, and is consistent with our relevant information and assumptions. Any suggestions for improving this process?”

Specify how members should prepare for the meeting. Distribute the agenda with sufficient time before the meeting, so the team can read background materials and prepare their initial thoughts for each agenda item ahead of time.

Identify who is responsible for leading each topic. Someone other than the formal meeting leader is often responsible for leading the discussion of a particular agenda item. This person may be providing context for the topic, explaining data, or may have organizational responsibility for that area. Identifying this person next to the agenda item ensures that anyone who is responsible for leading part of the agenda knows it — and prepares for it — before the meeting.

Make the first topic “review and modify agenda as needed.” Even if you and your team have jointly developed the agenda before the meeting, take a minute to see if anything needs to be changed due to late breaking events. I once had a meeting scheduled with a senior leadership team. As we reviewed the agenda, I asked if we needed to modify anything. The CEO stated that he had just told the board of directors that he planned to resign and that we probably needed to significantly change the agenda. Not all agenda modifications are this dramatic, but by checking at the beginning of the meeting, you increase the chance that the team will use its meeting time most effectively.

End the meeting with a plus/delta. If your team meets regularly, two questions form a simple continuous improvement process: What did we do well? What do we want to do differently for the next meeting? Investing five or ten minutes will enable the team to improve performance, working relationships, and team member satisfaction. Here are some questions to consider when identifying what the team has done well and what it wants to do differently:

Was the agenda distributed in time for everyone to prepare?

How well did team members prepare for the meeting?

How well did we estimate the time needed for each agenda item?

How well did we allocate our time for decision making and discussion?

How well did everyone stay on-topic? How well did team members speak up when they thought someone was off-topic?

How effective was the process for each agenda item?

To ensure that your team follows through, review the results of the plus/delta at the beginning of the next meeting.

If you develop agendas using these tips, and the sample agenda and template below, your team will have an easier time getting — and staying — focused in meetings.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers