Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1306

March 27, 2015

Case Study: Is It Teasing or Harassment?

“My, my, how tiny you are! You must be the smallest woman on earth. Hello, Dot!”

These were the first words Jack Matthews spoke to Sema Isaura-Mans.

Editor’s Note

This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Sema, a finance manager at the Dutch-British financial services consultancy Dirksen-Hall, had recently transferred from its Ankara office to its headquarters, in Amsterdam. Jack, the executive vice president for special projects, was her new boss. He’d also just relocated—from Manchester, where he’d been a VP of sales. They were meeting for the first time at the kickoff for a big project to which they’d both been assigned.

Sema was completely taken aback by Jack’s remark. Though she was barely five feet tall and weighed just under 45 kilos, she had never given her petite build a second thought at the office. For a few seconds, as Jack and the others around the table chuckled, she sat speechless. But then she looked the six-foot-five, potbellied Englishman in the eye and, without really thinking, replied, “Hello, Big Dot,” which made everyone laugh even louder.

“Well, she’s got a sense of humor—nice one!” Jack said, clapping his large hands. “I’m dead chuffed you’re on our team, Sema. I’ve heard only good things about you.”

He moved to the head of the table and asked all the others in the room to introduce themselves. Then he outlined the task that lay ahead. Their goal was to create a common platform for all the various back-office and client-facing computer and network systems used by the company’s international offices. This would both improve service provision globally and greatly enhance Dirksen-Hall’s ability to manage enterprise risk. Code-named “Samen,” the Dutch word for “together,” the project would affect some 600 employees in 40 offices across the 28 countries where Dirksen-Hall had a presence. It was a gigantic undertaking. However, Jack said, looking pointedly around the room, every person there had been handpicked by management in the knowledge that he or she could get the job done. By the end of his introduction, everyone could see why Jack himself had been appointed the project leader.

Sema felt excited. She had almost forgotten about the beginning of the meeting, but then Jack spoke up as she was walking out: “Sema, let’s get a meeting on the calendar for tomorrow, okay? Thanks, Dot.”

Bernhard’s Wife

Sema and her husband, Bernhard Mans, had been invited to a Dirksen-Hall welcome event that night. The company was growing rapidly; it hosted monthly parties for all newcomers and transfers. Bernhard worked for the company too, as an IT specialist. He and Sema had met when he’d gone to Ankara to install new systems, and the two had dated long-distance for a while after he returned to Amsterdam. They had been married only a few months when Sema was tapped for Project Samen, and both of them were thrilled: Finally they could share a house and a city.

“Luck is on your side,” Sema’s mother had said when she heard the news. “But remember who you are, Sema. You might work for a European company, and be married to a European Christian, and be moving to Europe, but you are still a Turkish Muslim. Don’t forget where you come from.”

Sema assured her mother that she wouldn’t.

She and Bernhard had been chatting with a few of his colleagues at the party when Dirksen-Hall’s CFO, Harold van der Linde, approached. One of the men started making introductions. “And this is Bernhard’s wife, Sema,” he said. She felt a rush of indignation as she held out her hand to van der Linde. Bernhard quickly piped up: “Yes, we’re here for Sema, actually. She’s the finance manager for Project Samen—” but someone tapped the CFO on the shoulder, and Van der Linde made a polite exit before he could hear anything more about her.

“Bernhard’s wife, indeed!” Sema fumed as they left the building. “Does that guy think all Turkish women wear a veil and clean toilets?”

“Come on, love, give him a break! I’ve worked with that guy for five years. It’s only natural that he’d refer to you as my wife, and—”

“So my master’s of science in finance means nothing, my MBA from Sabancı means nothing, my six years’ experience as a direct report of the Turkish CFO at Dirksen-Hall means little more. I see. My name is Dot, and I am Bernhard’s wife.”

Turkish Delight

Six months later, Sema still remembered the quarrel vividly. Of course, Bernhard’s colleague hadn’t been the real problem that night. She soon learned that he was a lovely Dutchman with the utmost respect for women; his wife was a surgeon, and they had two whip-smart teenage girls. The real problem was Jack. Although Project Samen was on track to be a huge success, and Sema was energized by the work, she’d grown increasingly uncomfortable with the informal team dynamics he encouraged. He still called her Dot all the time. It was a joke that wouldn’t die.

That night there was to be a team-building dinner at Toscanini, in the Jordaan district, and Sema knew it would be a lively affair. True to form, Jack rose to speak after the second course, tapping his glass with a spoon. “Thanks, everyone, for joining me for this great dinner,” he said. “You’ve all earned it. But we still have a way to go. So, to help us along the way… it’s time for the Dirksen-Hall Team Globes.”

The awards were meant to increase cohesion and commitment and to provide mutual recognition among the members of the team. They consisted of certificates on which individual members had written short messages for their colleagues. Jack handed out the awards, reading selected lines from each one before asking the awardee to come forward.

Turning to Sema, Jack read, “Given your tremendous addiction—number-crunching add-ic-tion—it is just as well that you live in Amsterdam!” “You are certainly a quick study—not only do you appreciate Dutch humor, but you give as good as you get!” “Goes the extra mile and always finds the time to help others.” And finally, a joke that could only have come from him: “Help! I’m short of money because my finance manager’s too small! But what a Turkish delight!”

Her teammates applauded loudly as Sema stepped up to receive her certificate. She took it, smiled briefly, returned to her place at the table, and stuffed it into her bag.

“Feel like joining some of us in the pub?” Jack asked after dinner. “I know it’s been a long haul, but hang in there, Dot.”

“No thanks, I think I’ll pass,” she replied, forcing another smile. She turned away, cheeks hot with anger, tears welling in her eyes.

The Breaking Point?

“Can’t sleep?” Bernhard asked her in bed later.

“No, I can’t.”

“What’s up?”

“It’s Jack again,” Sema said. “Something he wrote on a stupid award at dinner this evening. ‘Help! I’m short of money because my finance manager is too small.’” She tried to imitate his Mancunian accent.

Bernhard laughed.

“It’s not funny!” Sema said, pulling away from him. “He’s just an uncouth salesman who likes his beer too much!”

“Sema, we’ve gone over this before. He’s respected in the company. He has a brilliant track record. And you know these British types—especially the ones from the north. It’s a particular kind of humor.”

“Humor? To ridicule someone’s physical appearance? It’s now become acceptable for the entire team to make fun of my size. Last week he called me Dot in a meeting with Harold! And in front of a client!”

“Why don’t you just tell him to stop?”

“Everyone laughs at his jokes. And they respect him too. The whole team prides itself on being close and informal and having a good time even when we’re under intense pressure. I don’t want to be the killjoy.”

“Okay, then quit. Ask HR for another assignment. Or leave the company. There are plenty of finance jobs out there. No one is forcing you to stay.”

“How would I explain that? And why should I quit? That would be like exonerating Jack for his offensive behavior.”

“I know I’m supposed to just let you vent and not offer solutions, Sema. But this has been bothering you for six months, for the entire time you’ve been in Amsterdam, for most of our married life! If you’re this unhappy, you need to do something about it.”

Sema got up, went into the kitchen, and made herself a cup of sweet tea. Bernhard followed, but she gave him a kiss and told him to go back to bed. She wanted time to think.

Question:

Should Sema lodge a complaint against Jack?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

After a few minutes, she powered up her laptop, logged on to Dirksen-Hall’s intranet, and read the first paragraph of the HR director’s introductory comments, which stressed the company’s commitment to creating a work environment free from discrimination and harassment—one in which diversity was valued, and all employees were accorded dignity, courtesy, and respect. She clicked on a few links and found documents outlining the company’s ethics policies and grievance procedures. They offered contact information for both the HR director, Gerda van Leeuw, whom Sema had met during her relocation process, and the company’s ombudsman and head of corporate social responsibility, Tim Connolly. She opened up another window, logged on to her e-mail account, and started writing to both of them. But then she stopped cold.

Project Samen was more than half finished. And I’ve lasted this long, Sema thought. How could she complain—or quit—now?

[image error]

Relearning the Art of Asking Questions

Proper questioning has become a lost art. The curious four-year-old asks a lot of questions — incessant streams of “Why?” and “Why not?” might sound familiar — but as we grow older, our questioning decreases. In a recent poll of more than 200 of our clients, we found that those with children estimated that 70-80% of their kids’ dialogues with others were comprised of questions. But those same clients said that only 15-25% of their own interactions consisted of questions. Why the drop off?

Think back to your time growing up and in school. Chances are you received the most recognition or reward when you got the correct answers. Later in life, that incentive continues. At work, we often reward those who answer questions, not those who ask them. Questioning conventional wisdom can even lead to being sidelined, isolated, or considered a threat.

Because expectations for decision-making have gone from “get it done soon” to “get it done now” to “it should have been done yesterday,” we tend to jump to conclusions instead of asking more questions. And the unfortunate side effect of not asking enough questions is poor decision-making. That’s why it’s imperative that we slow down and take the time to ask more — and better — questions. At best, we’ll arrive at better conclusions. At worst, we’ll avoid a lot of rework later on.

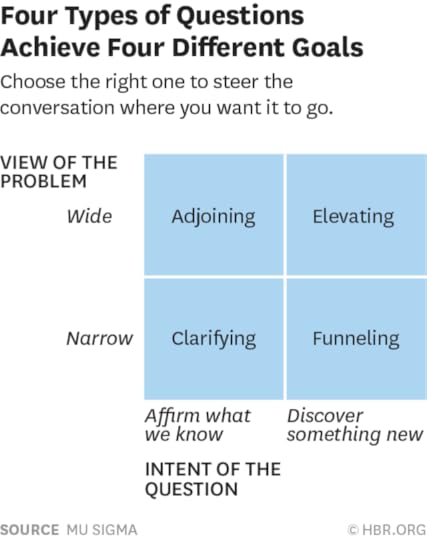

Aside from not speaking up enough, many professionals don’t think about how different types of questions can lead to different outcomes. You should steer a conversation by asking the right kinds of questions, based on the problem you’re trying to solve. In some cases, you’ll want to expand your view of the problem, rather than keeping it narrowly focused. In others, you may want to challenge basic assumptions or affirm your understanding in order to feel more confident in your conclusions.

Consider these four types of questions — Clarifying, Adjoining, Funneling, and Elevating — each aimed at achieving a different goal:

Clarifying questions help us better understand what has been said. In many conversations, people speak past one another. Asking clarifying questions can help uncover the real intent behind what is said. These help us understand each other better and lead us toward relevant follow-up questions. “Can you tell me more?” and “Why do you say so?” both fall into this category. People often don’t ask these questions, because they tend to make assumptions and complete any missing parts themselves.

Adjoining questions are used to explore related aspects of the problem that are ignored in the conversation. Questions such as, “How would this concept apply in a different context?” or “What are the related uses of this technology?” fall into this category. For example, asking “How would these insights apply in Canada?” during a discussion on customer life-time value in the U.S. can open a useful discussion on behavioral differences between customers in the U.S. and Canada. Our laser-like focus on immediate tasks often inhibits our asking more of these exploratory questions, but taking time to ask them can help us gain a broader understanding of something.

Funneling questions are used to dive deeper. We ask these to understand how an answer was derived, to challenge assumptions, and to understand the root causes of problems. Examples include: “How did you do the analysis?” and “Why did you not include this step?” Funneling can naturally follow the design of an organization and its offerings, such as, “Can we take this analysis of outdoor products and drive it down to a certain brand of lawn furniture?” Most analytical teams – especially those embedded in business operations – do an excellent job of using these questions.

Elevating questions raise broader issues and highlight the bigger picture. They help you zoom out. Being too immersed in an immediate problem makes it harder to see the overall context behind it. So you can ask, “Taking a step back, what are the larger issues?” or “Are we even addressing the right question?” For example, a discussion on issues like margin decline and decreasing customer satisfaction could turn into a broader discussion of corporate strategy with an elevating question: “Instead of talking about these issues separately, what are the larger trends we should be concerned about? How do they all tie together?” These questions take us to a higher playing field where we can better see connections between individual problems.

In today’s “always on” world, there’s a rush to answer. Ubiquitous access to data and volatile business demands are accelerating this sense of urgency. But we must slow down and understand each other better in order to avoid poor decisions and succeed in this environment. Because asking questions requires a certain amount of vulnerability, corporate cultures must shift to promote this behavior. Leaders should encourage people to ask more questions, based on the goals they’re trying to achieve, instead of having them rush to deliver answers. In order to make the right decisions, people need to start asking the questions that really matter.

[image error]

March 26, 2015

What Young vs. UPS Means for Pregnant Workers and Their Bosses

The U.S. Supreme Court case decided this week makes it significantly more likely that pregnant women denied workplace accommodations will succeed in their legal claims against the employers who denied them.

The Court’s decision in Young v. UPS holds that there may be some situations in which employers can accommodate some groups of employees, without also accommodating pregnant employees, but then creates a test so strict that it in effect eliminates employers’ ability to do just that.

Peggy Young, the plaintiff in the case, worked for UPS as a pickup and delivery driver. When she became pregnant in 2006, her doctor restricted her from lifting more than 20 pounds during her first 20 weeks of pregnancy and 10 pounds for the remainder. UPS informed Young that she could not work because the company required drivers in her position to be able to lift parcels weighing up to 70 pounds. As a result, Young was placed on leave without pay and subsequently lost her employee medical coverage.

Young claims that her co-workers were willing to help her lift any packages weighing over 20 pounds and that UPS had a policy of accommodating other, non-pregnant drivers. At the time, UPS accommodated (1) drivers who were injured on the job; (2) drivers who lost their Department of Transportation certifications; and (3) drivers who suffered from a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Young brought a federal lawsuit against UPS under the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1987.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to clarify that Title VII’s longstanding prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex includes a prohibition of discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions. Central to Young’s case, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act also requires that employers treat pregnant women “the same for all employment-related purposes . . . as other persons not so affected but similar in their ability or inability to work.” It is this clause that the Supreme Court’s decision in Young v. UPS interprets.

UPS argued that its decision not to provide an accommodation to Young was non-discriminatory because it followed a company policy that does not take pregnancy into account — a so-called “pregnancy-blind” policy. The Supreme Court disagreed, finding in Young’s favor after two lower courts had taken UPS’s side.

But as it turns out, despite finding in her favor — with Justice Breyer writing an opinion that was joined be all three female justices, and Chief Justice Roberts — the Supreme Court didn’t agree with Young’s interpretation of the law either. Young said that employers are required to accommodate pregnant women when they provide an accommodation to any other non-pregnant employee who is similar in ability to work. Breyer’s decision (and a separate concurrence written by Alito) did not buy into this analysis. However, that may not have much effect on the practical implications of the decision. The Court articulated a high legal burden employers will have to meet in order to justify their policies or practices that provide accommodations to some categories of employees, but not to pregnant women. The Court then remanded the case to the lower court to determine whether UPS can meet this burden here.

Under a “disparate treatment” theory of liability, as alleged by Young, an aggrieved employee must show that she has been intentionally discriminated against. The Supreme Court in Young found that to make this showing, the employee must demonstrate that the employer’s policies impose a “significant burden” on pregnant workers, and that the employer has not raised a “sufficiently strong” reason to justify that burden.

But what is a “significant burden,” and what is a “sufficiently strong” reason for imposing it?

An employee may persuade a court that a significant burden exists by providing evidence that the employer accommodates a large percentage of non-pregnant workers while failing to accommodate a large percentage of pregnant workers. For example, in Young’s case, she may show that UPS accommodates most non-pregnant employees with lifting limitations while categorically failing to accommodate pregnant employees with lifting limitations. Policies that provide accommodations or light duty to certain categories of employees, but not to pregnant women, will likely be found to impose a significant burden on pregnant employees.

As to evaluating the strength of an employer’s justification for imposing such a burden, the Court warned that the employer’s reason “normally cannot consist simply of a claim that it is more expensive or less convenient to add pregnant women to the category of those . . . whom the employer accommodates.” What justifications may be strong enough then, the court did not say, but sufficiently strong justifications based on factors other than cost or difficulty may prove to be rare. Further, the fact that an employer accommodates some employees tends to show that the employer does not have a good justification for not accommodating pregnant women also. As Justice Breyer put it: “why, when the employer accommodated so many, could it not accommodate pregnant women as well?”

It’s important for employers to understand that the Pregnancy Discrimination Act is not the only law that requires them to provide accommodations to pregnant women. The 2008 amendments to the Americans with Disabilities Act extended the scope of that legislation to require employers to provide necessary accommodations to pregnant women with pregnancy-related conditions that meet the definition of “disability” – and most now do meet that definition. Although the amended Act did not apply in Young’s case because it became effective after her case was filed, both the majority opinion and one of the dissenting opinions recognized the 2008 expansion of that law.

The law of pregnancy accommodation is becoming more complex, leading some lawmakers and advocates to call for clarity with a federal Pregnant Workers Fairness Act. The law would cover all pregnant women and ensure that the requirements are clear for employers and employees alike. In states where pregnancy accommodation laws have passed, there has in fact been a decrease in the number of pregnancy discrimination claims filed. There is also evidence that providing accommodations is good for business – it reduces employee turnover and absenteeism and boosts employee morale and productivity. Indeed, during the course of the Young litigation, UPS voluntarily changed its accommodation policy, even while maintaining that it was not required to do so by law.

Employers can make sure that they’re on the right side of the law by taking the following steps:

Ensure that light duty policies that apply to some categories of employees, such as those with on-the-job injuries, apply also to pregnant women.

Take a good look at other workplace policies to ensure compliance with both the Pregnancy Discrimination Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act’s mandates to provide accommodations to pregnant women. Employers in cities and states that have pregnancy accommodation laws will need to ensure compliance with those laws’ often more expansive requirements as well. Employers should review at least the following types of policies to ensure pregnant women are not disfavored: accommodation, leave, scheduling, and attendance. The easiest solution may be to simply amend existing policies and procedures to include accommodations on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions (including lactation).

Establish procedures for determining what accommodations are necessary and appropriate.

Train supervisors about how to recognize and respond to pregnant employees’ need for accommodation.

Most businesses already provide accommodations to pregnant women because they understand that it is in their best interest, and the best interest of their employees, to do so. The time has come for those who have not already complied to get on board. Liability under Title VII comes with not only compensatory and punitive damages, but often also hefty legal fees, which may far exceed actual monetary damages awarded. On the other hand, accommodations required by pregnant women are temporary and typically inexpensive. The smartest and safest course of action is to provide them.

[image error]

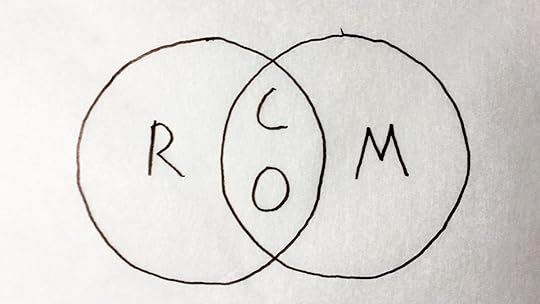

How CMOs and CROs Can Be Allies

Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) and Chief Risk Officers (CROs) may seem to have little in common. The CMO has historically focused on driving growth and brand engagement; the CRO has typically focused on safeguarding the bottom line and minimizing unwanted exposure. But the advent of Big Data, sophisticated modeling techniques, and robust algorithms are opening a door to cooperation and opportunities that have never been possible before.

Both practices have long developed insights into their customers based on data and analytics. But in the aftermath of the financial crisis, risk managers have become increasingly involved in business strategy and decisions. That has coincided with marketing’s increased influence on strategy, driven by the unprecedented level of insights into customer behavior and trends that are now possible through analytics.

This convergence creates a new opportunity for both disciplines, in effect, to pool their understanding of customer behavior and apply a broader range of sophisticated analytical approaches. By working together, both disciplines can provide more value to the business.

We speculate that because CMOs and CROs have historically focused on different aspects of the business, there are few examples of close CMO-CRO collaboration today. We believe, however, that there are several specific ways the two roles can work together more closely and learn from each other:

1. Take a customer–life cycle approach. Marketers recognize that buying behaviors change over time as customers get older, have children, switch jobs, build wealth, and retire. To get a handle on that changing value, marketers use an array of data, from prior transactions to predictive analytics.

By contrast, CROs have traditionally segmented customers through a narrower—and often static—range of data that usually reflects their current financial histories but ignores their brighter, more profitable future potential. CROs can increase market share among underserved customers, such as small business owners and the “unbanked” (i.e., those without bank accounts), by adopting the more dynamic “customer life cycle” view. After the recession, for instance, one large lender made a practice of looking for “rehab” customers whose credit suffered in the downturn but who had since managed to achieve more stable incomes. The lender targeted those customers with more attractive rates—rates that reflected the total life cycle value of these customers—allowing them to grow at a faster pace than peers while keeping losses within acceptable risk levels.

2. Use risk data as an avenue for innovation. CROs are deeply familiar with the troves of risk data, such as payment habits and internal credit scores, that their companies keep. With a little creativity, CMOs can work with them to monetize that data to create new products and, in some cases, whole new markets.

The marketing and sales team of one major technology vendor, for instance, partnered with risk to assemble a range of financing packages to help its mid-market clients fund upgrades, manage invoice payments, and smooth cash flows. The risk team helped run the numbers to ensure the client met the right credit threshold, then marketing prepared the package and the reps went to work. The ability to offer financing gave the technology vendor a point of differentiation that helped it beat its revenue projection for the year.

3. Gauge and influence a customer’s “next best action.” Better analytics and understanding of the customer decision journey have allowed CMOs to discern where customers become frustrated, tune out, or turn away. The CMO of a telecommunications company, for instance, found the biggest spike in churn came when customers moved. When marketing dug into the issue, they found the root cause had more to do with the tedium of calling the company and waiting on hold to reactivate an account—typically a 20-minute exercise—than dissatisfaction with the telephone service itself. By updating its website, the company let customers renew their service online in a matter of minutes and with just a few clicks—stemming the churn by 40%.

The risk function can do the same. Risk managers traditionally wait until a negative event has occurred before taking action, rather than looking for ways to intervene ahead of time to change or take the edge off the outcome. A customer prone to overdrafts, for instance, might receive an email when his account dips below a certain level. Mortgage payers with a track record of being more than 15 days late could receive incentives or loyalty points that reward early payment. By pairing behavior patterns in key segments with macroeconomic and demographic data, risk organizations can predict what those patterns portend—before the customer sinks into the red or starts shopping for a loan elsewhere.

4. Adopt a test-and-learn approach. Marketing leaders know that they have to be prepared to iterate and optimize on the go. Procter & Gamble, for instance, realized it was losing market share by testing its media campaigns exhaustively before releasing them. With its 2012 London Olympics sponsorship it resolved to optimize its ads in real time. When testing revealed its original tagline wasn’t connecting with consumers, P&G swapped it out for one that resonated better. And when tracking revealed one version of an ad was more successful than another, P&G immediately shifted media support to the stronger one. The overall media plan was optimized continuously, with the result that P&G saw a 40% bump in performance over its Vancouver Olympics campaign.

CROs can adopt a similar test-and-learn approach to their risk models, which typically see little modification. The CRO of one B2B, tired of getting stung by customers that ran afoul of the company’s 90-day credit terms, implemented a more dynamic way of anticipating delayed or partial payments. In addition to tracking the normal financial metrics, the risk team also kept tabs on unfolding news and events concerning their core client base. A product recall notice, a downstream supplier going belly-up, news of an acquisition or spinoff, or a sudden spike in the cost of a key raw material were all factors the CRO could use to help price the risk appropriately—and in near real time—before renewing the line of credit.

5. Protect and manage reputations. News travels fast in the age of digital, which raises the stakes not just for blunders but for everyday business activities. A small online retailer, for instance, ran a coupon promotion but neglected to ensure the coupons had individual codes to control their use and dispersion. The oversight exposed the company to a potential financial hit that was much deeper than intended. The company faced the choice of whether to cancel the coupon and suffer the brand backlash or honor the coupon and suffer the gross margin loss.

To figure out which way to go, marketing turned to the company’s head of finance and risk to help quantify the potential exposure. The finance team brought its scenario modeling tools to bear. They compared financial data from past campaigns to estimate the possible uptake of the coupon, then analyzed the estimated lifetime value of the customers who would be impacted by the potential cancelation. Running through a series of best, moderate, and worst-case scenarios improved marketing’s decision-making power and gave them a more concrete way to manage the uncertainty.

Effective risk management and effective marketing share the same analytical underpinning, the same need for sound business judgment to supplement the analytics, and the same demand for an integrated top-management perspective. Leaders who recognize this and act upon it can unlock new markets and earn greater risk-adjusted returns.

Here are a few tips for kickstarting a CMO-CRO partnership in your company:

Select one or two areas for an internal “joint venture.” CROs and CMOs have a full plate, so single out a few priority projects to demonstrate the value of collaboration and cultivating a team culture. Examples could include integrating risk profiles into customer segmentation, using customer risk profiles to target specific promotional offers, or trialing a new credit scoring model.

Cross-pollinate your talent. The risk and marketing functions share many similar roles—data scientists, modelers, technology professionals—so with the right incentives employees can learn from both disciplines. This talent- and knowledge-sharing approach can also help you develop a more comprehensive view of your customers.

Standardize customer data. To improve segmentation and targeting capabilities, CROs and CMOs should work to create a common way of capturing and sharing customer data across risk, marketing, fraud, and finance. Defining common standards can improve how data is shared and how it is understood. Also share your analytical methods and practices—knowing how each practice derives its “most valuable” customer list, for instance, can be an eye-opening exercise into each function’s priorities and decision-making criteria.

[image error]

Price-Sensitive Customers Will Tolerate Uncertainty

When I help a company with their pricing strategy, the typical first day of an engagement entails the client company’s vice president saying with a grin: “So, how are you going to help us raise prices?”

While price-raising opportunities generally do exist, this is a provincial view of the upside of revamping a company’s pricing strategy. The real creativity—and often, the bigger opportunity—involves growing a business by activating dormant customers. Contrary to popular thinking, this often requires offering selective discounts—in other words, lowering prices, not raising them.

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could identify price-sensitive customers and discreetly offer them discounts—without having to lower prices to those who are willing to pay full freight? This is the exact goal of individual negotiation. Car salesmen who inquire where you live and what other cars you are considering aren’t making idle chit-chat; they are sizing you up and seeking clues on the most you are willing to pay. This enables them to charge a range of prices for the same product—higher to those wearing designer clothes compared to those who dress down. (This is why my typical car-buying attire is jeans and a ratty T-shirt.)

Of course, negotiating price with each individual customer is labor intensive, so most products and services can’t viably be sold this way. (Can you imagine an individual price negotiation with every customer for each product in their cart at Wal-Mart?) The good news is there are a variety of retail tactics which can be used to offer carefully targeted discounts.

A key pricing strategy involves using hurdles to identify price sensitive customers. While everyone likes lower prices, hurdles separate those who truly won’t buy without a price break from the posers who don’t really care about price. For example, customers who take time to search for, clip, and redeem coupons are jumping over multiple hurdles to prove they are discount-worthy. Ditto for consumers who fill out rebate forms—their actions prove their price sensitivity.

One way to create a hurdle is to introduce uncertainty into your product. Consider the Rolling Stones’ 2013 U.S. tour. The Stones were able to attract plenty of expense-account types and diehard fans who were willing to pay high ticket prices (as much as $2,000)—just not enough to fill arenas. The challenge the Stones faced is how to lower prices without losing these high-margin sales. The solution: They sold $85 tickets with an unusual condition. Specifically, you wouldn’t find out exactly where the seat was until you entered the arena. The rationale, which made sense, is that fans with a high willingness to pay wouldn’t play this seating-roulette game, and would instead pay full price for certainty.

Uncertainty pricing is a powerful driver of new sales. Dubious? Discount travel company Priceline is now valued at over $61 billion based on a business model of using uncertainty to sell to the budget-minded. To book a highly discounted hotel room on Priceline.com, you have to select the general area in a city you want to stay in, as well as hotel quality level (1–5 stars), and then submit a non-refundable bid. Only after inputting this information do you find out if your bid is accepted—as well as which hotel you won. The process adds several elements of uncertainty: What hotel will I get? How much should I bid? The reward to consumers for jumping over these hurdles is big savings. Priceline’s pitch to hotels is just as compelling. It offers a distribution channel to discreetly sell excess capacity without having to advertise rock bottom prices. Regular customers continue paying full price and the hotel’s brand is not tarnished. No one is the wiser…except those who win Priceline bids. (Disclosure: I love Priceline and use it often. I travel to New York for business and even though I pass my travel costs on to clients, it bothers me to pay $450 (plus close to 15% in nightly taxes) for a small room in a non-luxury hotel.)

But now an interesting wrinkle has cropped up for Priceline and its rival Hotwire. Popular web sites such as BetterBidding and BiddingforTravel are now providing information to assist bidders in understanding how much to bid, as well as which hotel they’ll likely get. This resolves much of the uncertainty associated with purchasing through Priceline. Are these sites going to harm Priceline’s business model? Not really. Using them takes time and savvy, which is simply another hurdle. I recently tried to explain to a friend how to benefit from insights on these Priceline-information web sites and he quickly became frustrated, claiming he didn’t need the headache. What he was really saying is that he doesn’t value the cost savings enough to jump over the discount hurdle. Counterintuitively, these rival websites may actually boost Priceline’s sales. I, for instance, wouldn’t use Priceline if BetterBidding did not provide guidance on which hotel I’d likely win.

Most companies overlook the upside from high growth discounting. Creating hurdles can draw in new customers without cannibalizing full price sales.

The question managers should ask themselves: What type of uncertainty can you introduce to your company’s products to grow sales?

[image error]

Technology Alone Won’t Solve Our Collaboration Problems

Every week a vendor introduces a new gadget, system, or service that promises to make us communicate and collaborate better, faster. Just look at the comments below any article about virtual teams. They almost always include someone either evangelizing or peddling a particular piece of hard- or software that will make it easier to work with people in different time zones.

Sure, these technological improvements help in many ways. As a case in point, I just found out the precise location of a package in transit from China to France, all while on a train going through the forest. Our fast moving, globally networked economy simply was not possible a few years ago. But more often than not, the problem we’re facing isn’t a technological one, but a social one.

Teaching, consulting, and working with executives across industries and geographies has provided me with lots of evidence of a simple truth: it’s not what technology you’ve got, but how you use it. Let me share a few examples.

Give people the full context when video conferencing. Skype, FaceTime, and similar desktop videoconferencing tools are connecting us everywhere. At home they let my parents join in on the chaos of their grandchildren’s dinner. In the office they allow us to hear our distant colleagues’ voices and see them so we can pick up on important non-verbal cues. By providing more contextual information, they create an experience that’s richer and more complete than a simple phone call.

But they don’t provide all the contextual information we need. I’ve heard from many managers stories of being in a serious one-on-one discussion with a colleague over video, only to have their conversation partner turn and speak to someone they didn’t realize was in the room. This left these managers wondering just how much of their conversation was public and precisely who that public might be. Others report repeated interruptions by anything from an overly efficient administrative assistant to a neighbor with a lawnmower doing laps outside the window.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

You can overcome these problems by conducting a virtual tour to give your partner a sense of your environment. Pick up your laptop and walk your colleague around your office so they can see the context in which you’re working. Or zoom out on the computer’s camera. When doing this, point out things that may distract you (like your helpful assistant or your lawn-mowing neighbor). This is particularly helpful in ongoing collaboration when you’ll be video conferencing regularly.

Don’t take out tech troubles on the person. The unfortunate reality is that no matter what technology you choose, at some point it will break down. The call will be dropped. The picture on the screen will go fuzzy. Setting aside the bafflingly strong correlation between the incidence of failure and the importance of the meeting (perhaps a discussion for another time), such disruptions create real problems. Often the biggest one isn’t the loss of data or connectivity but our reactions.

Ask yourself if the following scenario feels familiar:

You’re speaking with a colleague on the phone and you’re deep into the conversation about a disagreement you had. After explaining your position at length, you pause and wait for a response…only to discover that the connection dropped.

Now be honest with yourself: When you finally resumed the call, did you find yourself frustrated or even annoyed at the other person when you had to go back and repeat your point?

This is a displacement where our frustration at the situation gets misattributed to the actor. Our conversation partner had nothing to do with the breakdown—it’s the technology’s fault, not theirs—but we take our frustrations out on them. You may not be yelling and screaming because often the manifestations are much more subtle – but even being in a negative frame of mind makes us less receptive to what others are saying and quicker to judge.

This isn’t easy to counteract, but start by being mindful of the tendency to displace. And when you feel your blood pressure rising as a result of a technology failure, follow this helpful, and frequently offered, piece of advice: take a deep breath, count to five, and remind yourself exactly what it is you’re mad about. This is simple and common sense, but that doesn’t mean we remember to do it.

Align knowledge management systems (or any system for that matter) with how people do work. Lew Platt, the former chairman, president, and CEO of Hewlett-Packard once said: “If HP only knew what HP knows, we would be three times more productive.” Even companies a fraction of the size of HP need a good knowledge management system (KMS) to make sure that knowledge is available and accessible throughout the organization. There are lots of technologies available, and the cloud has made things even faster but, as all good CIOs know, knowledge management is fundamentally not an IT issue — it is a social one.

I’ve studied the use of technology in organizations making everything from snack foods to satellite parts as well as those providing services around the globe, and I’ve seen plenty of examples of massive and costly undertakings to put KMS systems in place that in the end were largely ignored — or at the very least failed to live up to the hype. A system only works if employees are socialized to look to it for information and keep that data current. In putting in a KMS, or switching to a new one, it’s less important which technology you choose and more important that you align it with how people do work. Too often, a new KMS often conflicts with the way that employees currently use informal networks to seek and provide information. The chances of a new system —knowledge management or any kind of system —succeeding is dependent on choosing a technology that aligns with how people already work (or in some complex cases, overhauling how people get work done if the existing systems are inefficient— but that’s a longer discussion).

While we often think of the future of collaboration resting on the shoulders of technology, that is only part of the story. Sure, technology provides opportunities, but it’s important to view technology and social systems as partners. The promise of tomorrow’s collaboration requires actively considering, designing, and fine tuning both.

[image error]

March 23, 2015

Collaboration, from the Wright Brothers to Robots

Watson and Crick. Braque and Picasso. The Wright Brothers. Wozniak and Jobs … and Jony Ive. Great collaborations all. Transformative. But what really made them work? How did collaborative relationships so ingeniously amplify individual talent and impact? Was there a secret to success?

When I wrote the book Shared Minds: The New Technologies of Collaboration 25 years ago (!), I found technology central to the answers. The book was the first to explicitly examine how tools and technologies shape creative collaboration in science, business, and the arts. I argued new technology would invite and inspire new forms of collaboration. Like communication, collaboration would have to become more networked and more digital.

But what I didn’t know — and couldn’t anticipate — was how overwhelmingly collaboration’s creative past would influence its innovation future. Successful collaborators don’t just work with each other; they work together through a shared space. Shared space — whether physical, virtual or digital — is where collaborators agree to jointly create, manipulate, iterate, capture and critique the representations of the reality they seek to discover or design. This holds true for collaboration around products, processes, services, songs, or the exploration of scientific principles. Shared space is the essential means, medium, and mechanism that makes collaboration possible. No shared space? No real collaboration.

James Watson and Francis Crick didn’t do a single experiment on their way to discovering the double helix and winning the Nobel Prize. But the shared space of their helical metal models proved indispensable to their collaborative success. Wilbur and Orville Wright pioneered wind tunnel designs and tests as shared space for flight design. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, and then Jony Ive, relentlessly prototyped digital devices like obsessive perfectionists.

Character, cognition, and creativity remain undeniably important. But they play out in the collaborative context of shared spaces where the real work gets done. It takes shared space to create shared understandings. That’s the key.

Insight Center

The Future of Collaboration

Sponsored by Accenture

How tools are changing the way we manage, learn, and get things done.

Take, for example, when Tim Berners-Lee had just launched the World Wide Web at CERN — in no small part to help facilitate global collaboration in high-energy physics. It was clear that digital media offered radically different properties than, say, blackboards, whiteboards, and faxes for empowering shared space. Expanding the bandwidths of shared space accelerated opportunities for shared insight.

A quarter century later, the diversity and intensity of digital innovation remains astonishing. But, looking back to look forward, three particular collaborative themes stand out. They’re important because they say more about the human aspects of collaborative relationships than the technological ones. As most digital innovators know, improving technological performance is easy, elevating human performance is what’s hard. Technology remains an indispensable ingredient. But enabling collaborators to get greater value from their shared spaces remains both the most rewarding and frustrating challenge. Here’s what managers need to be thinking about:

Collaborative culture, behaviors, and norms. Knowing what I’ve observed and know now, if I rewrote Shared Minds, I would invest more care and thought into understanding collaborative cultures, not just collaborative relationships. What makes a scientific discipline or artistic community or academic institution or R&D group energized and excited about embracing shared spaces to make collaboration simpler, more accessible, more effective, and more satisfying? How does collaboration become as much a value and a behavioral norm as a core competence and pragmatic means to creative ends?

By emphasizing great collaborations, I inadvertently minimized and marginalized broader cultural contexts. Companies and cultures that celebrate heroes and entrepreneurs and visionaries all too frequently communicate that collaborative relationships are inferior to individual genius. That may not be the intent, but it is surely an outcome. Of course, technology impacts culture, too. We live in a time where undetected plagiarism is becoming harder even as public attribution and acknowledgement are becoming easier. All human behaviors live in cultural contexts. Living collaboration as a value is intellectually and emotionally different than just practicing it as a skill. This issue deserves top-management attention and respect from every organization that takes collaboration seriously. Being a holding company of shared spaces and collaborative talent is radically different from actually being a collaborative company.

Collaborative scale. My historical examples of collaborative success were almost exclusively duos, trios, and small groups of intensely creative and committed individuals. The shared space dialogue or conversation dominated. I once half-jokingly remarked that perhaps the future of collaborative conversations would be “kilologues” and “megalogues”… and then came Wikipedia!

Networked reality now offers the intimacies of small team shared spaces where a core three or four can iterate and innovate to their collective minds’ content. But it’s equally possible to craft, scale, and mass produce shared spaces that encourage millions — 100s of millions? — of individuals to collaborate. Is a recommendation engine a collaborative shared space? Is a Kickstarter? Should we think of crowdsourcing as a prototype for mass collaboration? Or is crowdsourcing less shared space than mass exploitation? That might depend, of course, on how one chooses to define “shared” and “sharing.” Sharing — and its rules — are about as human a behavior as one can find. Scale has huge impact on how sharing is perceived and realized.

Truly successful collaborations have an inherent quid pro quo — that is, the collaborators all know that their individual contributions are meaningful, essential, and acknowledgeable. That’s as true for Watson and Crick as it is for Jobs and Ive as it is for Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin. But what happens to those quid pro quos as scale skyrockets into the millions or billions is unclear. The Internet does brilliantly at technically scaling individuals, teams, and organizations. But, emotionally and culturally, how exponentially do networked collaborations scale? That question represents a huge entrepreneurial and institutional opportunity for innovators. If you’re Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, Salesforce.com, or LinkedIn, the answer could be worth 10X to your market cap.

Synthetic collaborations. By far the biggest technical change (to me) since Shared Minds publication has been the pervasive rise of machine learning. The ability to extract and abstract meaningful patterns from humongous datasets is transforming how human beings create and recognize economic value. The onrushing internet of things only accelerates — or exacerbates — that trend. The unavoidable implication? Our best, most loyal, most indefatigable, most challenging, and most creative collaborators may be our machines. Centaur chess is the prototype here. There’s no inherent reason why smarter machines won’t be superb — or superior — collaborators in all kinds of shared spaces.

The rise of synthetic collaboration revitalizes the importance of collaborative culture and scalability. Will tomorrow’s organizations encourage, value and/or reward person/machine collaborations the way they do purely human ones? Similarly, will the most effective human collaborators succeed by having intimate collaborations with two or three machines/devices/programs? Or will harvesting the collaborative contributions of millions of machines become the gold standard in new value creation and discovery? Much the way the best machine learning programs make it relatively easy to “train” machines to become pattern recognition experts and recommendation engines, no great conceptual or technical leaps are required to anticipate machine learning software that can be trained to collaborate with other machines. Again, the internet of things may quickly evolve into an “internet of collaborative things” that learn how to create or discover new opportunities for value creation. Collaboration is a behavioral choice, as well as a cognitive capability. Machines now have both. Should they be imbued with collaborative temperaments, as well?

Before the decade ends, oncologists, radiologists, and other medical specialists will be successfully collaborating with networked machine learning systems that recommend diagnoses and interventions that they would not have thought of on their own. The financiers, lawyers, accountants, and auditors won’t be far behind. Neither will software developers nor cloud services managers. Arguably one of the most important professional decisions they’ll be making each and every day is whether they’d be more effective collaborating with people, machines or some particular, value-added combination. The best machines — not unlike the better humans — will help innovate shared spaces, not just better collaborate in them. In essence, smartphones will computationally evolve into smarter collaborators. Shared minds need not be human.

That’s why the future of better collaboration is better technology … and the future of better technology will be better collaboration. Full circle.

[image error]

6 Rules for Building and Scaling Company Culture

Great founders start businesses not to create a company but to solve a problem, to serve a calling, and to understand that they have a purpose that can actually make a meaningful difference. But of course, they also want their businesses to survive – and thrive – after they’ve moved on.

Great performance can never come without great people and culture, and the opposite is also true – great people and culture are affiliated most with high-performing organizations. We can argue over which drives the other. But there is one undeniable truth: when a company is in its earliest days – when there is no performance or numbers to speak of – the key differentiators are the team, their purpose, and their culture. The team is the company’s raw DNA, the purpose their religion, and culture their unique way of operating based on common principles, norms, and values. Like aiming a rocket ship into orbit, if you get this wrong from the start, your trajectory will only get worse over time.

After some two decades of launching, building, and operating some of my own businesses to both meaningful failure and meaningful success, I’ve observed some important principles for building and scaling a culture that can live beyond a set of founders to become a lasting institution. I’m certain there are other key things to do regarding culture and variations on the themes I set forth below, but here are my top six immutable laws of building and scaling great culture:

Start with purpose. I learned this from my partner Mats Lederhausen who has had a string of great business and culture-building successes as the former Chairman of Chipotle, Chairman of Roti, and co-founder of Redbox. The common theme he sees is that you need to begin by understanding your “why” — from the inside out. This is about mission, not marketing. What calling does your business serve? This should feel authentic, inspirational, and aspirational. The companies with strong purpose are the ones we tend to love best because they feel different – Chipotle, Pret a Manger, Ikea, Container Store, or Apple to name a few. Whether it’s trying to just offer better food, or democratize great design, the cause behind the brand is clear.

Define common language, values, and standards. A great mentor of mine, Tsun-yan Hsieh, was one of the foremost leaders at McKinsey. Over 30 years, he shaped a large part of its people development program, and taught me the framework of “common values and common standards.” Great cultures need a common language that allows people to actually understand each other: first, a common set of values, which are the evergreen principles of the firm, and second, a common set of standards by which a business will measure how they’re upholding those principles. For example, if you have mentorship as a stated value, then you must consider how you define it and how to measure it. Will it mean that you expect employees to follow a certain promotion path and career timeline? Does it mean that you will hold internal 360s that determine mentorship scores, and tie those scores to people’s bonuses? Or will you create go further, and only promote the people who develop others? Only when you have common language, common values, and common standards can you have a cohesive culture.

Lead by example. Leaders must reflect the firm’s values and standards. They must be the strongest representations of the firm’s culture and purpose, not just writing or memorizing the mission statement, but rather internalizing and exemplifying what the company stands for. Again, a few examples bring this to life: do people feel that a Richard Branson lives the Virgin way of spirited fun when he makes daredevil entrances or entertains on his island? Do people have any doubt that John Mackey of Whole Foods approaches food with a greater consciousness about its quality and provenance? These types of leaders have not just an incredible passion and work ethic for what they do, but a cultural ethic in that how they do what they do inspires others.

Embrace your frontline cultural ambassadors. Every organization I’ve worked with has people throughout the employee base who are unsung heroes of brand and cultural ambassadorship. These are people who love the company and its core purpose. They are your best cultural cheerleaders. They may be the folks on the shop floor trying to solve a product issue, an assistant talking to countless stakeholders, an analyst crunching the numbers, a customer service rep empathetically talking with customers, or a mid-level manager developing other people every day. When they tell friends and family about where they work, they don’t talk about a workplace but a work story, with a voice that comes from the heart. You know them when you see them, but as a company grows, it can take more effort to identify them. Do you know who these people are? Have you rewarded them and thanked them? At a time when outsourcing functions such as customer service or automating checkout procedures are becoming more common, the role of frontline cultural ambassadors does not diminish, but rather disproportionately increases and can become a real competitive advantage.

Seek, speak, and act with truth. Arguably self-awareness and truth-seeking are a subset of one’s values (point number 2), but I would argue that self-awareness and truth-seeking are so important that they should be on every company’s list of values. Some call this integrity, but truth seeking and self-awareness are slightly different. If integrity is best described by C.S. Lewis as “doing the right thing, even when nobody is watching,” then truth-seeking and self-awareness are about having the ability to be completely honest about your own strengths, weaknesses, and biases. In an authentic and strong culture this applies not only to the leadership team, but every single employee. Such self-awareness and truth-seeking is easy to lose, and hard to win back. When cultures are failing, there are usually root causes that can rarely be fixed quickly. During these times, people want to flip a light switch and — ta da! – see that the culture is fixed. Unfortunately, building, evolving and transforming cultures takes both time and hard work.

Be greedy with your human capital – then treat them right. The mantra at our own firm is that in the end it’s always about people and character. When recruiting folks, spend more time screening for character than you do screening for skill. While skills can be learned, it is much harder to cultivate attitude and character. This practice, known as “hire for attitude and train for skill,” was pioneered by Southwest about 40 years ago, helping to explain its track record as an admired, purpose-driven company. There is no doubt that over time, institutional character and culture is the simple by-product of individual people. Whether you are hiring based on competency or character, remember that A’s will always attract other A’s — but B’s will attract C’s. Bottom-line: be super greedy with the talent you bring in to make sure you get the A players. Compromising on talent that is good enough but not necessarily the best you think you can get, especially in pivotal job roles, is a sure formula to short-circuit your own culture and long-term performance. Once you’ve hired the right people, treat them right. The best long-term retention strategy is to mentor people toward meaningful roles. I’ve found that what matters more than any extrinsic rewards — like compensation and title — is pushing and developing people towards their full potential.

In business, we often overweight the “what” of the business and underweight the “how” and “why.” But it is the “how” and “why” that form both the soul and character of business — what employees feel when they come to work, and what customers feel when they do business with you. If you’re lucky enough to hit upon the right culture, do everything you can to preserve and scale it. If you can do that, then you can have a chance of not just growing a successful business, but of building a business that will survive long after you’re gone.

[image error]

How an NBA Team Thinks About Data, Talent, and Pricing

Basketball is on the brain in March. And while the differences are aplenty between college basketball and professional hoops, this sports season got us thinking about the business of athletics. Between ticket sales, sponsorships, merchandising, and media rights, Price Waterhouse Coopers estimates global sports revenues will grow to total roughly $145 billion. For an inside look at some of the trends shaping the business of basketball, I reached out to Rich Gotham, President of the Boston Celtics. An edited version of our conversation follows:

HBR: You’ve been with the Boston Celtics for 12 years now. How has the business of running a professional basketball team evolved in that time?

HBR: You’ve been with the Boston Celtics for 12 years now. How has the business of running a professional basketball team evolved in that time?

Gotham: In the years that I’ve been involved, things have become exponentially more sophisticated. These aren’t mom and pop operations anymore. Asset valuations in our league have really grown over the years. For example, Steve Ballmer just bought the L.A. Clippers for $2 billion. We now have entire conferences dedicated to the analytics of our business and our basketball operations. We’ve hit a point of acceleration in video and wearable technologies that provide us with information that we’ve never had in the past about how to optimize player performance. We have a global audience that has an unending thirst for mobile content, and a sophisticated CRM database that allows us to be a state-of-the-art marketing operation. We talk about things like yield management, demand curves, and perishable inventory — factors that dictate our pricing strategies. We’re working with unprecedented levels of data. At the same time, so much of what we do is all about the intangible, emotional attributes that really drive fan passion and engagement — that’s what fuels our business, and always has.

You’ve been with the Celtics in good years and bad. How do you keep the business itself running steadily, when team performance can change so much year-to-year?

You need to have a business that’s flexible enough to respond quickly. That way, when the going is good, you can maximize your upside yield on assets like ticket sales and merchandise, and when the team isn’t performing quite as well, you have a hedge in place to protect your downside risk.

The big revenue drivers in our business are TV media rights — both national and local — and ticket sales. The bulk of the variability in our annual revenue is in ticket sales, which is most sensitive to team performance. So, it’s a matter of trying to keep our finger on the pulse of demand in order to maximize our return. We monitor pricing and demand in real time using algorithms to help inform our decisions. In some cases, demand says that you can raise the price. In others, it says lower the price to drive a higher volume. We have an analytics team that’s built some models using regression analysis to help us with dynamic pricing. It allows us to determine the right price, for the right game, for the right customer — and even factor in a sudden last-minute snowstorm on top of that to see how it affects demand. We were really the first team in the NBA to say that it’s OK to price your tickets differently for different games.

The negotiation of a long-term media rights contract with Comcast SportsNet provides the franchise with long-term financial stability and gives us the luxury of running our business strategically for the long-term, without having to make shortsighted decisions. In sports, the big cost driver is really players’ salaries. What tends to happen is if a team isn’t performing well, and the business is down, they may not be able to continue to pay their players, so they make decisions that are not necessarily the best basketball decisions, but rather business necessities. We’ve tried hard not to put ourselves in that place. We want to have all available options to improve the team. So, having long-term financial stability in the form of media rights deals at the national and local levels allows us to continue to manage and run the business without any pressure to cut corners in the short term.

When you’re guiding a historically successful franchise, how do you handle the down years in terms of bringing in and keeping talent, managing the expectations of fans, and handling the media scrutiny?

I think the most important thing is to have clear and transparent communications with all of your constituencies — the fans, the players, sponsors and the media. For us, it’s really all about making sure that we never lose track of the big picture — that the Celtics are a championship-driven organization. Our fans and the media understand that that doesn’t mean we’ll win a championship every year, but we have to be able to communicate a strategy for how we’re building toward one — and that we wake up every morning working toward one. This year, we’re clearly in a building/transition year, the second one in a row, and we have to explain to fans how we’re putting the pieces in place to get to the next championship — how the franchise has positioned itself through young player development, salary cap management, the accumulation of draft picks, and all the other variables that go into driving future success.

Major League Baseball has revolutionized digital coverage of baseball with live-streaming. The NBA seems to have lagged. As someone who has a background in digital media, is this something you see as a priority? Where do you think the NBA should be focusing in terms of digital coverage?

I would actually argue that this is pretty far off base. While the NBA has taken a different approach than MLB regarding digital content, we are not lagging and are widely considered to be innovators, as evidenced by our global digital footprint, rivaled only by European soccer. The NBA was the first to have a YouTube channel, and we just did a major digital streaming rights deal in China. The NBA has a digital television product called League Pass, which can be live-streamed onto smart phones, tablets and other devices. NBA TV is in more than 80 million households. So, it’s a huge priority — it’s our primary fan engagement vehicle.

The Celtics have 9 million Facebook followers, 1.6 million Twitter followers, and 600,000 Instagram followers, so for a local team, we’re actually truly global. We create 150 hours of video content each year that we push out via Facebook — it’s a huge part of how we engage with fans. Almost all of what we’re doing with the NBA is mobile first. The smart phone is the first screen, not the second. It’s a very big part of what we do, and a very high priority. I honestly don’t think the NBA takes a backseat in that regard.

What do you envision for the future of live sports on television, since it’s arguably one of the last things you need a cable subscription for?

I think live sports and the NBA and the Celtics will continue to drive huge value for sports properties — the teams and the leagues — as well as whoever is the media rights holder. The world is increasingly “TV anywhere,” so it doesn’t have to be delivered solely through cable TV. But, whoever owns the live sports rights across multiple platforms has obsolesce protection, so while consumption trends may change in terms of how people are viewing your content, it will continue to get a premium.

Sports has been very good for the cable industry. Certainly anyone who’s thinking of dropping their cable subscription has to consider whether they want to drop their sports, and it’s very clear to us that they don’t. But, it’s not so much about cord cutting; it’s more about cord shaving. If you’re a Comcast SportsNet New England subscriber, you can get access to the Celtics live-streamed through your laptop in the local market, but that requires that you’re a subscriber to Comcast. You could be a subscriber to Verizon or AT&T or Time Warner, as well, but you have to carry the Comcast SportsNet package on your cable. It helps them maintain their current business, but also allows them to extend their business to these other platforms and turn those into incremental growth. So, if you have the live sports rights, you still have that value proposition that people so far, knock on wood, are not willing to live without.

I talked to a few families who said that they’d love to attend a Celtics game, but between the tickets, parking, food and drinks, it’s prohibitively expensive. What would you say to those families?

Tickets to sporting events can be expensive. Our pricing, as I mentioned earlier, is demand-driven and what the market will bear, and generally the market will bear a lot. But having said that, we recognize that being accessible and affordable is important for growing our fan base, so we have a lot of entry points. You can buy a Celtics family pack, which gives you four tickets, concessions and a souvenir for $70-$90, which is pretty affordable for a professional sports game. We keep about 25% of our inventory in the form of individual tickets that are $30 or cheaper. The idea is that we cordon off a certain amount of our seats so that we’re not pricing people out. That math fluctuates from year to year based on changing demand dynamics. For as long as I’ve been here, we’ve always maintained 300 seats for every game at a $10 price point, but we found that the scalpers were scooping up those seats and selling them at higher price points, so we had to combat that a bit. It’s about educating the market that those alternatives are available. In a year when the team isn’t considered to be a championship contender, we’re doing more marketing of those ticket offers and promotions using database-driven marketing.

When you don’t need to win games to make money, what’s the incentive to win?

It comes back to our mission statement. It’s very clear that our priority is to win championships. That’s what our brand is about, and that’s what we’re all in it for. To be honest with you, if our owners at any point in the distant future decide to sell the Celtics, they will make out well on their investment, but as far as the operations go, they don’t talk about profit margins; they talk about investing in the team to win championships. It’s organizational culture and values that create that pressure that we feel every single day — it’s what fuels us all. It would be so easy to say “Let’s just run a good business,” and then just sit back, but none of us are in it for that reason. We want to win.

If you could give your younger self one piece of career advice, what would it be?

Learn how to run a regression analysis! I’m like the old man here because I have to ask other people to do that for me. But more seriously, I think I would probably tell myself to ask more questions or to seek more advice from people around me. It takes humility to do that. When I was younger, I probably had a little too much pride about being able to do things myself. As you get a little more experienced, you realize how much you can learn from the people around you — not just the people who are more senior to you, but everyone in the organization, especially those who have different viewpoints. If I could go back, I’d try to be more cognizant of that.

What do you like most about your job?

So many people care so very deeply about the Celtics and what we do. I want our fans and our community to be proud of their team. I think that, more than anything, impacts how I feel and what I do when I go to work every day. That’s what’s driven me to get into this business, and it’s what makes it so much fun.

[image error]

When It Pays to Think Like a Finance Manager

If you want approval for a new project — purchasing new equipment or computer systems, applying for a patent, building a new store — chances are you need your company’s finance department on board. To get the green light, it helps to understand how finance people think.

Most finance managers in both large and small businesses encounter numerous proposals for capital investments and many of the people proposing these investments don’t have a clear picture of what the return will be. They’re essentially asking the company to take the cash it has generated through its business operations and spend it on something with an uncertain future return.

But finance people like me are skeptical even when the proposals do project a return. Here’s why.

Excerpted from

HBR TOOLS: Return on Investment

Finance & Accounting Tool

Joe Knight

29.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

Everyone always wants new equipment — new computers or other hot technologies. Do you think they’re going to do a net present value (NPV) analysis that shows they don’t need that computer? Of course not. They figure out how much the new computer system and software will cost and they compare that with the cash flow generated through efficiencies (assuming they know how to analyze returns based on cash flow). If the numbers show a negative NPV, meaning that the proposed investment isn’t justified, they change the assumptions until the NPV turns up positive.

From our point of view, in other words, most people use ROI analysis as a way to justify something they really want to do anyway. If you understand this, you will understand why experienced finance people are skeptical about proposals submitted by others. After all, you have to prepare an analysis that can stand up to their scrutiny.

Here’s a real example that happened in my business. In addition to my work as a financial trainer, I am part owner of a small manufacturing engineering company with a lot of technical employees. The two founding partners were both engineers who loved technology.

Several years ago, when I was serving as the company’s CFO, one of founders came to me and said, “Joe, I would like to buy a new three-dimensional printer.” A three-dimensional printer at that time was a big investment. He explained that when they do CAD drawings, they design the part on a flat screen and send it out to be fabricated, but often the part comes back and doesn’t fit. Then they have to scrap the part, go through a redrawing process, and have new parts fabricated. With this new technology they could take a CAD design, send it to the three-dimensional printer, and get a plastic model of the part. They could make sure it fits before they cut a more expensive metal version, thus eliminating the cost of rework.

He then said to me, “So can you do an ROI analysis? Compare the cost of the printer with the amount of cash we are going to get back over the next three to five years based on the fact that we no longer have to scrap parts?”

I asked him, “How much is a printer?” He told me that the kind he wanted would be at least $100,000.

“That’s a lot of money,” I said. “Let me ask you this question. Let’s say we figure out how much money we spend every year on rework, redrawing, and all the costs associated with that over five years. Suppose it turns out that it’s cheaper to scrap parts occasionally and spend those extra hours redesigning them than it is to buy the new printer?”

What do you think he said? Of course he said, “Well, if that’s your conclusion, then I know your analysis is wrong, because I know we need the printer.”

I replied, “So what you really want me to do is come up with a cost-justification model so that you feel good about yourself through the analysis.”

Guess what? We bought the printer. I could also tell you the story of a company owner who wanted to buy an airplane. When the CFO analyzed it and said “No way,” the owner got another CFO.

This happens more frequently than we would like to admit with capital budgeting analysis and the tools of ROI. Even large companies make investments such as acquisitions based on irrational projections. The CEO negotiates with a company he or she wants to acquire. If the numbers don’t work, the CFO is told to revise the projections so that they do.