Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1314

March 2, 2015

What Your Professional Bio Needs to Get Noticed

A professional bio is something that everyone needs, but not everyone bothers to write one. Or they write one once, and then never update it. Or they wait until a conference organizer asks them to send one in, and just jot down the first few things that occur to them.

That’s a pretty big missed opportunity. Your bio is a strategic play and should be treated as such. A bio can help you get hired, gain visibility, and win you serious respect. That’s why when I work with my clients, the first thing we work on is their bio.

Here are some of the main mistakes I see.

A lack of consistency. The biggest issue I see when working with client’s bios is a lack of consistency. If a journalist or recruiter cannot figure out who you are in under 30 seconds (because you have six different bios in six different places), you’ve lost your chance. You want to communicate who you are and what you do in a way that spans multiple websites. This means that all bios — from your personal website to your LinkedIn profile to your company’s site — need to be the same. You need to tell people who you are and drive the point home.

Everyone needs a long, short, and two-line bio. A long bio can be a full page, and can go on your personal website. A short bio is about a paragraph — probably the first paragraph of your long bio — and can serve as your default bio. A two-line bio can go under your byline or in a quick panel description. How do you decide what to cut for the shorter versions? Think of it as trying to give your bio as an elevator pitch. What summarizes you? Philanthropist? Serial entrepreneur? Connector? Try to describe yourself in 15 seconds. What you get across in there should be in your short bio.

The information is stale. Updating your bio regularly is very important. (This also means updating the short bio and two-line bio as well.) Every six months you should be revisiting your bio to see what has changed and what other experience you have accrued. Set a recurring calendar remind to do it. Have someone else read over it too — it’s hard to write about yourself, and you might be leaving a few things out.

There are no links. It drives me crazy to see accomplished people using bios that do not link to their work. Unless your bio is printed out on paper, such as in a pamphlet for a panel, link to your work. If you discuss running a campaign for a new product, show the outcome. Link to pieces you’ve written, press releases about an award, or your personal website. Your bio is a tool to showcase you and your work — and you need to make that as easy as possible for the reader. Don’t assume that someone will read your bio, alight on something you’ve done, open a browser tab, Google that accomplishment, search through the results, and then read about it. That’s too much work. You need to present it all, and hope that they will click on it. (You can also use bit.ly, which will allow you to track the number of clicks each link gets.)

Weak verbs. A cardinal sin is using the passive voice. When someone has used the passive voice in their bio, it always feels to me like they’re trying to downplay their achievements. The point of your bio is to emphasize your achievements. You are a person who has done things, so you need to write it that way — like you are proud and you mean it. Another type of downplaying is using verbs that suggest you are ”trying to” or “attempting” to do something, be that change an industry or work with an idea. That makes it sound like you’ve already failed. Remove it. You are not attempting to do it, you are doing it.

It’s just a list. A bio isn’t just a list of jobs followed by your degrees. A bio is a chance to sing your own praises about prizes, things you’ve written, positions you have held. Discuss an exciting project that received exposure and praise. It can contain information on passion projects, upcoming projects, or hobbies. Be careful to not be too casual or say things like, “In her spare time you can find Alice trying out the latest in microbrews.” This is a professional bio, so while you can include your hobbies, choose carefully and be straightforward rather than coy. Professional bios are not, in my experience, the place to be playful.

However, don’t throw in the kitchen sink. Every accomplishment you include should be there for a reason. And certain skills — like knowing how to use Photoshop or Excel — are such common skills you don’t need to list them. When it comes to your academic accomplishments, feel free to list your undergraduate or graduate degrees, but draw the line there. You don’t need to go into details (or high school).

The person refers to herself by her first name. ”William is an expert in iambic pentameter and revenge plots” does not sound as professional as saying that “Shakespeare” is an expert in those things. Not only is using your last name more professional, it’s also more memorable, since last names tend to be rarer than first names. What about referring to yourself as a “ninja” or “rockstar”? Drop it. While that might work in technology or the start-up world, it won’t read as professionally in more traditional industries. You want your bio to be something that travels across industries.

There are no calls to action. Your bio as a marketing tool for your business and for your career. If you speak, link to how to book you. If you offer an online course, link to that too. It would be a waste to have someone read your bio and not become a potential customer. That being said, any more than two calls to action reads as a hard sell, which isn’t the point of your bio. You want to save the calls to action for the most important clicks.

Tighten, strengthen, and regularly update your bio. When used correctly, it’s a tool that can help you stand out.

[image error]

February 27, 2015

Is Innovation More About People or Process?

What’s more critical to producing a breakthrough innovation – finding creative people or finding creative ideas? This is a question Pixar head Ed Catmull has asked a great many people, and he says they tend to be pretty much split on it 50/50.

This astonished Catmull. Fresh off eight blockbuster successes in a row in 2008, he was arguing in his article “How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity” that people exaggerate the importance of the initial idea, whereas, as he put it simply, “talent is rare.”

A trip through HBR’s archives shows that he’s hardly alone in this view. Bernard Arnault, for instance, the executive chairman of luxury goods maker LVMH, was clearly in the same frame of mind when we caught up with him in a 2001 HBR interview. “Our whole business is based on giving our artists and designers complete freedom to invent without limits,” he said, in describing his role in managing the likes of Dior’s top designer, John Galliano (who was in the midst of marketing a dress made from newspaper) and Vuitton’s Marc Jacobs (who came up with Vuitton’s signature graffiti handbag design).

Into the people camp also falls Michael Schrage, who in the same year wrote a particularly thoughtful account of IDEO, “Playing Around with Brainstorming,” one of the first of many articles on design thinking that have graced the pages of HBR, and still one of the shrewdest. Writing in response to the publication that year of IDEO cofounder David Kelley’s The Art of Innovation, Schrage argues that IDEO’s ability to innovate lies not so much in the methodologies of brainstorming, hot teams, and rapid prototyping that Kelley describes but in its culture. It is the intensity of its people’s passion for innovation that animates IDEOs processes, he contends, forming a culture that’s “not typical, and not easy to emulate.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising that companies full of motion picture, fashion, and product designers should feel comfortable with the notion that innovation depends on talent. Or that this approach doesn’t sit well with the more engineering-oriented innovation thinkers whose work forms a parallel stream of thinking in HBR (and perhaps represent the other half of the crowd in Catmull’s polls).

Let’s call this the “In my ideal world, great ideas are generated through a process anyone can follow” camp. At the most technical end, arguably, is Intel, whose innovation process, based on the precise exchange of information, is described in meticulous detail by Steven Eppinger in “Innovation at the Speed of Information.”

The goal of many thinkers in this camp is to turn the practice of innovation into something closer to a production process than a creative process precisely to produce “more ideas – better ideas!” as Robert Sutton and Andrew Hargadon put it in “Building an Innovation Factory.”

Sutton and Hargadon bring useful detail to what might seem like a generic process: start with good ideas from lots of sources, discuss them, play with them, imagine new uses for old ideas, and turn promising concepts into real products, services, and business models. Stefan Thomke describes Bank of America’s process for inventing new service offerings in similarly useful detail in “R&D Comes to Services,” in which a set of bank branches serve as a test bed for creative ideas that was “large enough to support a wide range of experiments but small enough to limit the risks to the business.”

Lego has used the systems approach to great effect; P&G has arguably elevated the factory approach to its most elaborate. Coming something of a full circle, Intuit has famously instituted a process to teach everyone to think as creatively as the talented professionals of Pixar, Dior, and IDEO. Vividly described by Roger Martin in “The Innovation Catalysts,” this process requires as much grit and persistence as systems thinking, bringing to mind Schrage’s warning that even systematically generated design cultures are hard to pull off.

An uncomfortable sense that some of these innovation processes are as hard to emulate as the innovation cultures that depend on rare talent recently led Scott Anthony to think about the most minimal steps an organization that lacked both the resources of a P&G and the creative genius of a John Galliano could take to create a reliable path to innovation. The four steps he and his colleagues lay out in “Build an Innovation Engine in 90 Days” don’t promise to turn your company into a P&G overnight. But even here, while the steps may be minimal, they are not all that simple. The first requires that top managers understand and explicitly determine how innovation fits within the larger corporate strategy. The second that they select a few areas to explore that fit with what a substantial number of potential customers really need and what the company is uniquely positioned to deliver. Then it’s time to appoint a small innovation team and assign executive sponsors to guide them.

To help in this effort, particularly for small companies that may be new to innovation, Anthony distills a great deal of knowledge from highly experienced innovators into a nicely practical assessment both the team and their sponsors can use to answer what is perhaps the most fundamental question of all — “Should we pursue this new project?” – and work out whether (or not) they’re on the right track.

In the end, the answer to the people or process question is probably “both”: people matter; process matters. Talented people can be hobbled by poor processes; hesitant people can be uplifted by smart processes. In the best of all possible worlds, extraordinary people pursue innovative ideas through processes that are perfectly suited to their talents. In the real world, less-than-perfect people are wise to use all the help they can get.

[image error]

What Greece Has to Do Now: Fix Its Economy

After weeks of media frenzy around the Greek election and the new government’s once-ambitious plans to renegotiate with the Eurozone over its debt crisis, the searchlights of publicity are shifting. For all of its bravado, Greece was pushed into a corner in an eleventh-hour deal that will extend a bailout agreement for four more months. And although it has been given a temporary lifeline, little has been resolved.

Greece’s creditors have by and large insisted that prior agreements be honored, and told the government that its radical plans for state largesse (let alone debt forgiveness) are off the table. A few verbal tweaks (such as renaming the “Troika” — which consists of the EU, the IMF, and the ECB — the “Institutions”) were given as a political concession to the newly elected government, which had created high expectations with its electorate.

The tentative agreement with creditors reached this week is much less favorable to Greece than what was on the table last fall. To be sure, the proposal set forth by the Greek finance minister is less detailed than that of his predecessor, and leaves some room for maneuvering, but this is a mixed blessing, as the EU, the IMF, and the ECB will need to sign off on specifics. Greece appears also to lose control of the €11 billion reserves of the Greek banking stability fund.

Worse still, the real issue, which is the possibility of lightening the real debt load by rescheduling payments and extending maturities (but without affecting the nominal value due to Greece’s official creditors), has been pushed away, and some in Germany would want to renege on a 2012 deal which reduced interest rates and extended payments.

This unfortunate state of affairs is partly the result of the difficult negotiating hand Greece dealt itself. Greece did have some good arguments going for it: It had achieved the biggest fiscal adjustment any developed country had mustered so far, stabilized its economy, and restructured its private debt. As for its official debt to the EU, the ECB, and the IMF, it consisted largely of payments that were made to pass through to EU financial institutions, between 2010 and 2012, so that the Eurozone banks and insurance companies would not be imperiled. So, clemency on loan terms might make procedural sense. It also made economic sense, allowing Greece’s GDP to grow, and thus ultimately pay the creditors, as Paul Krugman has repeatedly argued.

The initial reactions, in particular in the press, were positive. Greeks would be able to plead their case; to ask for support; to explain why they deserved it. But the new Greek team consisted of an inexperienced and ambitious set of politicians and academics with little, if any, policy experience. And as days unfolded, perceptions about them changed. Insistence was taken to mean intransigence and entitlement; gusto was seen as lack of respect; and the unusual negotiating style (which included leaking document drafts) infuriated the negotiators in the EU. The Greek team found out that in a restructuring, the debtor isn’t in the driving seat; and that Mediterranean posturing can win you more enemies than friends in Brussels and Berlin.

At the end of a difficult process, the Greek government has ended up deciding that a collapse of its banking system and a forced introduction of a parallel currency to pay state obligations is not a price worth paying in order to keep its promises to the electorate.

The EU is notorious for putting off its hard decisions. This is precisely what it did with Greece in the first place, by not allowing it to restructure in 2010, and thus building this mountain of debt. But this time around, kicking the can down the road has a silver lining in that it gives time to Greek society and polity to adjust. For ordinary Greeks, who were told by their politicians that there was an alternative way out, and that the EU would fold, it is certainly a rude awakening.

But it also means that public debate may shift from how best to renegotiate to how best to fix the Greek economy. For all the talk of reform, little has happened on the ground: this is partly a legacy of poor leadership from the previous government as well as of the Troika’s priorities. With financial negotiations now stalled, it’s time to focus on the “hard yard” — the issues in the public sector holding Greece back, such as red tape, barriers to competition, a clientelist, incumbent-friendly state, inefficient public services, and a challenging environment for new businesses. These were things that the previous government, especially from the summer of 2014 onwards, also failed to achieve, and that the Troika was unable to push for.

Will there be progress in this regard? Many a government has started with bold declarations, and the proposed agreement contains strong pledges. Yet when it was in the opposition Syriza, the new party of government, blocked any effort to reform the public sector, open up the economy, or infuse competition. It is now being asked to act against its ideology: its new commitments to stick with the agreed upon privatizations, to “fix” the pensions deficit, and to reform the inflexible labor market contradict its pre-election pledges.

Worse, Syriza started its tenure by appointing failed MP candidates to the position of Secretary Generals of key Greek ministries. The lack of experience, coupled with an inefficient public sector, does not bode well. Will an advertised collaboration with the OECD bear any fruits? It might, but so far there’s little evidence on the ground. It looks like “politics as usual,” and what will make or break this (or the next) government is moving beyond that.

One ray of hope is that some changes in the justice system may take place, and tax and duty evasion might be contained. Despite its travails, Syriza retains significant support from a large part of the electorate, which voted it in not because of its policies, but because of its quest for a fairer social system, with fewer people evading taxes or the law. But to do so will require determination, and a shift in government and governance.

This looks unlikely. The problem is that Greece needs operational, transformative changes in the short term, and a revamping of its productive base, starved of investment as it is, in the medium term. The Greek problem isn’t, as Krugman insists, a classic problem of macroeconomic policy. It’s primarily a problem of an economy rendered uncompetitive from state inefficiency and political turmoil.

So, what can we expect moving forward? Most probably another crisis, small or large. Organizations (and countries) in crisis really wake up only on the edge of the precipice. The tragedy is that sometimes this happens too late. The Greek crisis may have abated for a while, but if its root causes are not fixed, expect it to return, soon, to rock the Eurozone. And next time around, “the Institutions” may be less accommodating.

[image error]

Millennials Want to Be Coached at Work

Imagine showing up to play an important college basketball game on a fabled rival’s home court, only to find you’ve forgotten your shoes. Now consider what to expect from your coach, after losing the game. A royal chewing out for not having your head in the game? The cold shoulder? Worse?

Neither, according to NBA hall-of-famer Grant Hill, as he recalls the incident. His coach was Mike Krzyzewski of Duke, affectionately known as “Coach K,” and the winner of over 1,000 games, including the 1992 Olympic gold medal. Instead of a blistering by Coach K, there was an ice cream sundae party and another practice to help the team recover from the humiliation of the loss. Coach K’s focus was not on defeat, but on teambuilding and getting the heads of the young players ready for the next game. And recover they did, winning two national titles in and .

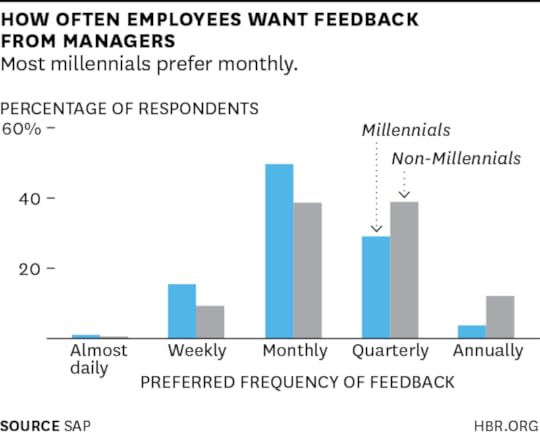

The young people in your office aren’t so very different from the young Grant Hill at Duke. They crave — and respond to — a good, positive coach, who can make all the difference in their success. In a global survey that we at SuccessFactors conducted in 2014 in partnership with Oxford Economics, 1,400 Millennials told us they want more feedback from their managers. As you can see in the chart below, most Millennials want feedback at least monthly, whereas non-Millennials are comfortable with feedback less often. Overall, Millennials want feedback 50% more often than other employees. They also told us that their number one source of development is their manager, but only 46% agreed that their managers delivered on their expectations for feedback. There’s a lot of room for improvement, according to the data.

Our subsequent conversations with hundreds of Millennials made it clear that what they want most from their managers isn’t more managerial direction, per se, but more help with their own personal development. One Millennial we spoke with summed up a theme we heard again and again: “I would like to move ahead in my career. And to do that, it’s very important to be in touch with my manager, constantly getting coaching and feedback from him so that I can be more efficient and proficient.” For coaching to resonate, managers should also consider a young person’s psyche. In an analysis of psychological tests of 1.4 million college students from 1938 to the present, Millennials were found to have more self-esteem while also having more anxiety and a higher need for praise. Great coaches understand this, and know that to create a winning team, they need to meet people halfway in their coaching needs. Specifically, Millennials have told us that they want managers to:

Inspire me. In all aspects of their lives, Millennials engage with causes that help people, not institutions. The team and the mission, especially tied to a higher purpose, are far more compelling motivators than a message of “Do this for the company,” or “Work on the department goals.”

Hill reminisced that, “One of the things that really impressed me [about Coach K] … was his ability to motivate and inspire … before games, in the locker room, having that right message to get you fired up, ready to run out there, and run through a wall. And that’s not an easy thing.”

Further Reading

HBR Guide to Coaching

Managing People Book

19.95

Add to Cart

Save

Share

When was the last time you experienced that level of motivation and inspiration from your manager, or the last time you created that experience for someone else? The good news is that you can learn how to inspire others, according to Joseph Folkman, founder of two leadership development companies. In his analysis, the four biggest traits of inspiring leaders are providing a vision, enhancing relationships, driving results, and serving as a principled role model. To a lesser degree, being enthusiastic and being an expert also matter. In fact, every behavior of a leader matters, and the little efforts add up. Just by noticing an employee’s efforts, commenting on it privately or at a team meeting, and telling her how she’s progressing toward her goals inspires an employee. I personally have a hand-written note from an old boss, Bill Johnson, who was then the CEO of H.J. Heinz, that says, “You made a difference.” Fourteen years later, it still sits on my desk, inspiring me to live up to that belief.

Surround me with great people. Young people repeatedly said, “Help me up my game by working with people who are talented and better than I am (now).” As Coach K said “All the players who arrive at Duke are immediately humbled in some ways because of the level of the work, the speed at which they have to play, and the fact that they are not always the best player on the court. A lot of them have never had to work that hard before because they had always been the best player.” That same experience can play out with a new college graduate who shows up in your office to find herself surrounded by extraordinary talent. Your job as a manager is to coach that new person while they are most fragile, rather than fostering a sink-or-swim environment. Take a lesson from Coach K, who uses techniques such as asking a more experienced player to boost the ego of the new player. Newcomers are fragile and malleable, and a little boost can go a long way toward reducing anxiety and improving performance.

Be authentic. Millennials seek an approachable manager and a role model whom they can emulate. Telling stories of your own failures and struggles, as well as your victories, makes you more approachable. Consider how Coach K would share his own stories about times when he’s felt overwhelmed whenever he’d see a new player daunted by the skills of those around him. Good coaches aren’t afraid to show emotions or experience those of their team, whether it’s the rush of victory or the disappointment of defeat. What an honor it is to share the deepest of human feelings with our coworkers. Managers who are authentic coaches and good listeners build trust — an essential foundation upon which to build a great team.

According to Tim Gallwey, author of a series of books about the inner game, “Coaching is unlocking a person’s potential to maximize their own performance. It is helping them to learn, rather than teaching them.” Or as applied to the business world, coaching is not about telling people what to do, but helping them to achieve all they are capable of doing and being. The best managers — and, indeed, the teams that go on to greatness — are the ones who understand this important distinction.

[image error]

How to Help Your Team Bounce Back from Failure

No one likes to fail. And while we all know the importance of learning from mistakes, both individuals and teams can struggle to bounce back from big blunders. Whether it was a project that didn’t meet its targets or an important deadline that you all missed, what can you do to help your employees recover? How can you help them see the experience as an opportunity for growth instead of the kiss of death?

What the Experts Say

It’s often harder to lead a team past a failure than it is to help one person. “People are coming into projects with different expectations, perspectives, levels of investment, and different things at stake,” explains Susan David, a founder of the Harvard/McLean Institute of Coaching and author of the HBR article, “Emotional Agility.” “Some people may be very resilient and others might feel more bruised,” Ben Dattner, an organizational psychologist and author of The Blame Game. “All the things that individuals fall prey to — misattribution and rationalization — are compounded on a team and add exponential complexity to the process.” It doesn’t matter whether one person on your team is at fault or if everyone bears some of the responsibility, it’s your job as the manager to help the entire group move on. Here’s how.

First, take control of your own emotions

Research shows that a leader’s feelings are far more contagious than a team member’s so, while “you don’t want to suppress your emotions, you don’t want to get stuck in a moody, negative space either,” says David. Do whatever you need to move on from the disappointment so that you’re ready to help your team deal with theirs. And don’t try to fake it. You need to be genuinely in control of your feelings or your team will see through you.

Give them space

At the same time, you shouldn’t become a “beacon of positivity” before the team is ready, David says. It’s okay to let everyone wallow in “disappointment and negative feelings,” for a little while. She points to a client whose team lost a client pitch they’d been working on for months. It happened on a Friday and on Monday morning she came in saying, “Let’s move on,” Although she was trying to be motivating and forward-focused, to her devastated team, she “came off as uncaring and uncommitted.” In fact, negative or neutral emotions are conducive to deductive reasoning, which means they can help your team more effectively process and analyze the failure. When you acknowledge the disappointment — with comments like “We’re feeling down” or “This is tough for us” — “you’re not just stroking people’s emotions. You’re facilitating a critical appraisal of the situation.”

Be clear about what went wrong

Don’t sugar coat what happened or resort to “corporate speak” that abdicates responsibility. Avoid phrases like “let’s look on the bright side,” “we’re lucky it happened this way,” “we suboptimized,” or “a mistake was made.” Instead, be clear: “We missed the deadline because we didn’t take into account how long each task would take.” When you focus on the facts, Dattner says, you can call it like it is without being demotivating.

Further Reading

Strategies for Learning from Failure

Leadership Article

Amy C. Edmondson

Begin by understanding how the blame game gets in the way.

Save

Share

But don’t point fingers

“It’s more important to focus on what’s to blame, rather than who is to blame.” Dattner says. If the fault really does lie with one person or a few people, then talk to those individuals in private and focus on their actions, not character. Dattner suggests you say something like: “Here’s the mistake you made. It doesn’t mean that you’re a bad person, but we need to understand why so it doesn’t happen again and we can move on.” You can also address the group but be sure to do it in a way that doesn’t single anyone out. David recommends an exercise where each team member writes down and shares a piece of feedback for each person on the team. “This allows for personal feedback that is also equitable,” she explains.

Shift the mood

At some point, it’s also important to move on from analyzing the failure to talking about what comes next. “The mutual commiserating and examination of what went wrong is useful only up to a point,” says David. After a day or two (or maybe longer if the failure was a big one), push your team to more strategic, open-minded thinking and discussing how you will avoid similar mistakes in the future. Call a meeting and make sure that the tone is positive and energized. Dattner says you can use humor to lighten the mood.

Tell a story

You can help everyone begin to see the experience as a learning one by telling them about a mistake you’ve made in the past. “It can be very powerful when a leader authentically shares a time when they have a crucible-type failure that became a stepping stone in their career,” says David. If you don’t have a story—or don’t feel comfortable sharing it—consider drawing one or two out from the group. You could say something like: “We’ve all been on failed projects that ultimately proved to be constructive. Would anyone be willing to share?”

Encourage collaboration

Then have a conversation about the lessons learned from this experience. Don’t lecture; discuss. David recommends dividing the team up into two groups: one half thinks through what could go wrong in future projects while the other half focuses on the positive—what the team can change going forward. It’s important to “focus more on solutions than problems, more on the future than the past,” says Dattner.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Deal with your own emotions about what’s happened so they don’t unduly influence the team

Give team members time to feel disappointed

Talk about what went wrong and why

Don’t:

Get stuck in a negative, analytical mood for too long — shift the conversation to focus on the future

Allow people to point fingers at one another — give constructive feedback and move on

Lecture the team about what they can learn — let the ideas come from the group

Case study #1: Allow your team to vent

Chris Bullock (not his real name) and his five-person team were responsible for upgrading application software for his company’s most challenging client. This involved a large data migration, which did not go as planned. The day after the group turned the switch on the migration, they noticed that the system wasn’t working properly and calls from the client started coming in. While Chris and his team hadn’t written the actual code, they had been the ones in charge when it failed, so many at the company were blaming them. They were disappointed and angry. “We put a lot of time and late nights into the project and for it to fail — and so spectacularly — was embarrassing,” he says.

The team worked through the weekend to fix the problem. On Monday, Chris left them alone. “For me, these types of failures are like bereavements, and as such people need to work through a similar process,” he explains.

On Wednesday, the group met to talk about what had gone wrong. They discussed questions like: “Could we have spotted it sooner? Why hadn’t the test cases found it?” This allowed them to vent and point fingers at other teams not in the room. As a result, by Thurday, they were ready to have a much more constructive discussion with a larger group about how to do things differently next time around.

“We got back on the horse quickly and did the upgrade again two weeks later, and this time, with a successful result,” Chris says. The team learned a lot from the experience — most importantly that they were: “stronger together.”

Case study #2: Get your emotions under control

Wendy Rodriguez has been the director of development at INCAE, the leading business school in Latin America with campuses in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, for eight years. The school celebrated its 50th anniversary last year and Wendy and her team were responsible for a series of commemorative events.

For the first one, a 700-person gala, they prepared an extensive program “We were under a lot of pressure and stress. We wanted everything to be more than perfect,” says Wendy.

But it was “a massive failure.” They’d planned to show videotaped speeches but none of the audio-visual technology worked, so the school president board chairman had to come up with off-the-cuff remarks.

Wendy and her team were crushed. “We didn’t talk about it for two weeks. No one wanted to. It was just too depressing,” she says. As the head of the office, she even considered resigning. But soon she saw that her mood was affecting her team, and she made a conscious effort to change it. “I decided to put the problem behind me and take control again. The office needed me to lead,” she says. “It took a lot of effort because I knew it needed to be authentic. It wouldn’t work if I was just faking it.”

She decided to set up two meetings every week. One was “more social”– the team would go out for lunch. And the other was focused on discussing the rest of the events coming up and how they could plan better. “We had nine more events to do. We knew we had to be more careful and have contingencies in place,” she says. By focusing on work and spending time together, the team began to get its confidence back. “We hadn’t wanted to say hi to anyone in the office but these meetings helped us to raise our heads,” she says.

All the other events went off without a hitch.

[image error]

Here’s Why People Trust Human Judgment Over Algorithms

You’d think after years of using Google Maps we’d trust that it knows what it’s doing. Still, we think, “Maybe taking the backroads would be faster.”

That’s an example of what researchers call “algorithm aversion”: even when an algorithm consistently beats human judgment, people prefer to go with their gut. This can have very real costs, from getting stuck in traffic to missing a sales target to misdiagnosing a patient.

Algorithms make better assessments in a wide range of contexts, and it might seem logical that if people understood that they’d be more trusting. In fact, seeing how algorithms perform makes things worse, because it means seeing the algorithm occasionally make a mistake.

In a paper published last year, Berkeley Dietvorst, Joseph Simmons, and Cade Massey of Wharton found that people are even less trusting of algorithms if they’ve seen them fail, even a little. And they’re harder on algorithms in this way than they are on other people. To err is human, but when an algorithm makes a mistake we’re not likely to trust it again.

In one of the experiments, participants were asked to look at MBA admissions data and guess how well the students had done during the program. Then they were told they would win a small amount of money for accurate guesses and given the option to either submit their own estimates or to submit predictions generated by an algorithm. Some participants were shown data on how well their earlier guesses had turned out, some were shown how accurate the algorithm was, some were shown neither, and some were shown both.

Participants who had seen the algorithm’s results were less likely to bet on it, even if they were shown their performance too, and could see that the algorithm was superior. And those who had seen the results were much less likely to believe the algorithm would perform well in the future. This finding held across several similar experiments in other contexts, and even when the researchers made the algorithm more accurate to accentuate its superiority.

It’s not all egotism either. When the choice was between betting on the algorithm and betting on another person, participants were still more likely to avoid the algorithm if they’d seen how it performed and therefore, inevitably, had seen it err.

When asked to explain themselves, the most common response from participants was that “human forecasters were better than the model at getting better with practice [and] learning from mistakes.” Nevermind that algorithms can improve, too, or that learning over time wasn’t a part of the study. It seems our faith in human judgment is tied to our belief in our own ability to improve.

If showing results doesn’t help avoid algorithm aversion, allowing human input might. In a forthcoming paper, the same researchers found that people are significantly more willing to trust and use algorithms if they’re allowed to tweak the output a little bit. If, say, the algorithm predicted a student would perform in the top 10% of their MBA class, participants would have the chance to revise that prediction up or down by a few points. This made them more likely to bet on the algorithm, and less likely to lose confidence after seeing how it performed.

Of course, in many cases adding human input made the final forecast worse. We pride ourselves on our ability to learn, but the one thing we just can’t seem to grasp is that it’s typically best to just trust that the algorithm knows better.

[image error]

When to Tell Your Employees to Stay Home

When I sat at my computer last week, trying to write out a policy explaining under what extreme circumstances we might need to close our office and how we would define our work schedule on days when people might not be able to get to the office, I thought back to a situation several years ago. One of my sons was working at a consulting firm in Nairobi, Kenya. He called to tell me that there had been a suicide bombing, with multiple fatalities, at the bus station, through which he sometimes commuted. He was obviously shaken and asked me for advice. Knowing that he was disenchanted with the job anyway, I said “Come home.” He did.

My son was lucky that he could pack up and leave when he wanted to. There are workplaces around the world located in violence-embroiled countries, or offices regularly assaulted by extremes of nature such as monsoons and sandstorms. As I sat down to craft our policy, I wondered how their employees knew whether they should go to work that day and who communicated that information. Over the past few weeks, my city, Boston, has faced the most disruptive commuting conditions in my lifetime, as a result of a record 100 inches of snow in a little over three weeks. The relentless snowstorms have caused a total failure of the city’s infrastructure, including the ongoing disruption of our entire public transit system.

My colleagues have been anxious, regularly emailing me at night to ask about work the next day. Would we be open? What if the train lines weren’t operating again, or facing multiple-hour delays? I would look out through my window, as another ten inches were falling, and feel at a total loss to provide a good answer. We were offering reimbursed cab or Uber service, but sometimes those vehicles weren’t able to navigate unplowed streets. Drivers who could get out struggled around the snow mountains jamming every intersection. And parking? What parking?

Human beings are drawn to rules. Whether or not we agree with specific policies, we want there to be a policy of some kind. We crave clarity. But we also demand flexibility. If school systems require that students attend a given number of school days to graduate, for instance, we also ensure that certain absences can be excused. As CEO of our company, whatever rules I might establish needed to cover both business continuity and appropriate concern for our colleagues’ safety. Having spent several hours one frigid and snowy night trying to change a tire that hit an invisible pothole, I realized that my determination to get into the office every day, regardless of the conditions, was possibly a sign of obsession rather than logic.

So I asked friends in other countries what happens when roads are impassible or police vehicles surround urban centers where they work. Respondents from Hong Kong to Israel explain that everyone just carries on as if the situation were “normal.” Government authorities rarely give any guidance as they worry that any widespread edict to close would be a sign of systemic weakness — which they are loath to express. Employees in developing counties, with fewer legal safeguards, fear that if they do not show up for work one day, at best they would lose a day’s pay and at worst, their jobs.

I then surveyed people who run investment companies (my field), venture capital, law, retail, and real estate firms, asking what they were doing about work interruptions. I had assumed that as an investment management company, which typically follows the calendar of the New York Stock Exchange, we should operate when the major exchanges are open, and fellow CEOs agreed with that. Thomas, one such executive, told his employees that safety was their number one goal, and to use their own best judgment. If travel was extremely difficult, employees were urged to work remotely or commute at less busy hours. Another, Steve, said that he’d received a number of emails from colleagues asking for flexibility given that they had to shovel or snow blow the driveway. Exhibiting some frustration, he told me, “I have the same problem. I’m not taking my G4 from Palm Beach every day. I’m shoveling and driving just like they are.” He was also crafting a new policy. Marcia, a venture capital executive, told me that she felt these policies encouraged critical decision making, and, at the very least, people needed to think through how important it was for them to be in the office, versus enduring a multi-hour commute.

Some non-investment companies found it easier to close the office on a couple of days, although the professionals were expected to keep working from home on current projects. Every CEO acknowledged that a parent with young children, whose schools were closed, and who had no childcare options, needed to stay home. John, a real estate executive, framed this as a labor relations matter to be handled carefully so that no one felt marginalized.

After listening to my peers discuss their firms’ policies on extraordinary conditions, I wrote up a draft and asked a couple of my partners to review and revise it if necessary. We agreed that we would be open if the New York Stock Exchange was operating, unless something truly disastrous occurred at our office’s location, or the state or city government ordered all offices to be closed. At the same time, our greatest concern was the safety of our employees. Some members of our team live within walking distance of our office, but others live much further away. They needed to use their own judgment on whether or how they might get to work, would be reimbursed for alternative transportation, and would not be penalized if they didn’t come into the office. Everyone seemed relieved to have something in writing.

And mercifully, spring will come. Eventually.

[image error]

February 26, 2015

You Don’t Have to Be the Boss to Change How Your Company Works

Most workplaces face constant imperatives for change—from trivial-seeming matters such as installing new office printers to major ones such as implementing new policies to support diversity. The question of how to drive change, though, is perennially vexing.

Some things make it easier: If you are the boss, you can order change (although that doesn’t always work). If you have a broad coalition, you can create the perception of a flood of support. If people rely on your work output, you can impose conditions on how and when you’ll deliver it.

Often, though, the people charged with driving change don’t have any of these things. Consider Brian Welle, a Google manager who needed to roll out a huge initiative to tackle the problem of unconscious bias in the workplace. Some people are very receptive to investigating their own biases and trying to reduce them. Others, though, reject the notion that they might unwittingly hold prejudice, as reflected in some people’s indignant reactions to the slogans “check your privilege” and #blacklivesmatter. Convincing a Google-sized workforce not to resist his ideas, let alone embrace his initiatives, was a huge challenge for Brian—who was not the boss, didn’t lead a huge coalition among those he was trying to influence, and couldn’t horse trade to compel their cooperation. He was just a guy from People Analytics—in other companies, that would mean HR—who was planning presentations to try to change people’s minds.

It’s no surprise that people resist organizational change—they are overworked and overburdened, and simply don’t have the bandwidth to embrace change. Further, they rely on habits and routines to help them meet their own work demands, and so change—which disrupts those habits and routines, and forces people to engage in new, active, and energy-demanding ways—appears highly undesirable. So when change agents like Brian can’t rely on power, rank, or wide support, they need good strategy.

An effective strategy for creating change requires several elements, but one of the most important is to convince people to alter their attitudes—to move from rejection to openness, at least, or embrace, at best. If you can create change in people’s attitudes, it’s much easier to change their behavior.

The Power of Baby Steps

Psychologists Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland identified a powerful dynamic about attitude change, and gave it a clunky name: the latitude of acceptance. Here’s how it works: We can think of any attitude on a continuum from pro to con. For example, some Googlers were likely excited to see the company address unconscious bias (strong pro), others likely resented the effort, believing that they were not biased and did not need to change (strong con), and others had reactions somewhere in between.

Wherever your own attitude along the continuum, Sherif and Hovland argued, you are willing to entertain some other views, but only within a narrow range around your own attitude—this range is the latitude of acceptance, or “OK zone.” A Google engineer in Brian’s presentation audience might think, “I’m not biased and I don’t need to change”; if so, her OK zone would likely include attitudes such as, “Diversity initiatives are a waste of time” or “Some people like to make me feel guilty about the success I’ve worked hard to attain.”

Are You the Best Messenger?

The “OK Zone” approach is extremely effective in many situations, but be aware of a key limitation: Sometimes people are strongly invested in a position not because they’ve thought it through, but out of a sense of identity or moral intuition. For example, in current debates over science-related policy (regarding vaccinations, climate change, or GMOs), some people embrace views that contradict scientific findings because of religious convictions or because they identify strongly with “clean” movements that oppose intervention in nature. Even before opening their mouths, advocates face huge challenges in persuading such individuals to consider a more pro-science view: Being identified with the scientific community paradoxically makes their arguments suspect. The OK zone can be used to produce movement even among strong partisans; however, it may have to be used in a more covert way. Recruiting someone less objectionable—a fellow clean eater or a credible religious figure—to deliver the message is one tactic that helps overcome this problem.

If Brian’s presentation started with a big slide proclaiming “All of you are biased”—that is way outside of this engineer’s OK zone. It’s in her latitude of rejection—or the “reject zone.” This is the crucial point: When attitudes are too far from our OK zone, we not only don’t buy them—we actively retrench against them. We marshal all of our resources to oppose the person making the argument. If Brian started his presentation by proclaiming that everyone is biased, the engineer would likely respond by becoming even more committed to denying any bias in herself. If we want to change someone’s attitude, first we need to understand where that person’s OK zone is. We do this by asking questions to identify where they are on the attitude continuum right now.

Finding the OK Zone

In 2005, Dave Licher was a project manager for a large defense contractor. One of his projects was to replace thousands of one-off copiers, printers, scanners, and fax machines—many sitting in people’s own offices—with multifunction devices (MFDs) that required leaving one’s office and walking down the hallway. These days, the office multifunction print machine is a familiar fixture. But 10 years ago, it was new, and introducing one to the workplace meant asking people to change habits that were deeply ingrained and replace them with something whose benefits were unknown, but whose immediate inconvenience was obvious.

Dave encountered immediate resistance, notably from Ken (not his real name), the manager of a large unit, who insisted that he didn’t want his people’s work “disrupted”—and Ken’s influence meant that many others followed his lead. Dave wasn’t sure why Ken was so vehement, but he knew he needed Ken on board. His first move was to get up from his own desk and walk to Ken’s office to ask—with genuine curiosity—for Ken’s views. Ken explained that his staff was already under the gun and couldn’t afford to spend the extra time needed for a new process. Then Dave asked how Ken typically handled his print jobs. Ken showed how he’d print from his computer to a local printer in his own office—a small, inefficient machine that took a long time to spit out the job. Then he’d have his administrative assistant walk that original down to a formal copy center to make stapled copies—copies that looked second-generation.

Dave had been prepared to pitch the new machines’ superior properties and the cost savings, but the chat with Ken revealed the need for a different approach. Dave asked for just one step from Ken: to allow Dave to install a software driver, right then and there, on Ken’s computer, so that he could show him one print process—and if Ken didn’t like it, Dave would go away (for now). Ken agreed, Dave installed, and then Dave asked Ken to print a document. This time, though, the job was sent to the new MFD, a few doors away. By the time they walked to it, Ken’s job—all copies, fully stapled, and all first-generation quality—were waiting for him. No assistant, no walk downstairs, no wait for the copy center to get to it. Ken became a big supporter, and when others heard that “hard case,” change-resistant Ken was on board, they decided the change must really be a good thing.

Dave’s willingness to understand Ken and tailor his “ask” to Ken’s OK zone meant that Ken was willing to embrace a change he had fought. The small step of getting Ken on board helped roll out the switch to MFDs. And the MFD switch, though it may seem like a small project, ultimately saved the company $85 million over 5 years.

Changing the OK Zone

Of course, changing the OK zone typically requires more than a simple, one-step demonstration. Consider Brian Welle’s initiative again. Brian designed an hour-long presentation (which you can watch online) to pitch Google’s new initiatives around unconscious bias. (A presentation is generally not the most powerful way to use the baby-steps approach to change—individual, face-to-face discussions tend to be more effective—but Brian had to influence a lot of people in a short time and he used baby steps so masterfully that he pulled off “change-by-presentation.”) Within the video, you can see how he went to his audience’s OK zone and moved it, step by step, toward his target.

First, he acknowledged Googlers’ identities as smart people who like data and evidence (0:30). He next encouraged audience members to acknowledge that it was possible that we all make suboptimal decisions at times—particularly about other people (0:53). He presented research (1:15) showing how people very much like his Google audience can be biased in some situations, and then (3:20) recast the notion of “bias” entirely by showing how bias can be a positive and adaptive thing, such as when it allows us to recognize dangerous animals and avoid being eaten. This let him, in short order, invite the audience to think they might sometimes show the positive kinds of bias (4:38) and then acknowledge that they definitely do so (5:00). From here, it wasn’t too big a step to helping the audience confront that they also have some biases they don’t like so much (9:27), and then that it’s worth trying to work on such biases.

Avoiding Common Errors

Using this incremental approach can help you avoid some of the major pitfalls that threaten efforts to drive change. These pitfalls include:

Trying to achieve “conversion” and not just progress. Don’t expect to achieve all your goals in a single shot.

Talking mostly to people who already agree with you.

Trying to drive change without others’ help. Messages are more persuasive when they seem to arise from many people, and they’re less easily dismissed as one person’s “pet project.”

Relying primarily on email blasts. Even well-crafted messages don’t result in major change.

Motivating change primarily by appealing to lofty principles. Self-interest beats lofty principles.

At this point, the phrase “slippery slope” may have come to mind. In fact, that’s exactly what we’re using. You create a slippery slope by presenting small, incremental attitude positions and helping the person move from one to the next. Time and patience are often required with this approach, though sometimes it goes very quickly. And the attitude change it creates is much deeper and more genuine than that created by speech-making, peer pressure, or giving orders.

The process of using baby steps can seem time consuming in the abstract. Brian shows that it doesn’t have to be. He uses just 13 minutes from the start of his presentation to bring the audience along on a step-by-step argument that—as we can see from the body language and energy of the audience members shown on camera—people are now buying. He never takes a rigid or confrontational stance, but acknowledges his audience’s likely views at each stage, treats those views as legitimate, and uses them to build a case that is effective because it incorporates their views.

Like any change effort, effective use of this approach requires some planning. You’ll work not by sending email blasts and trying to convert the entire organization at once, but by targeting carefully selected individuals in carefully tailored ways. A few key questions to ask yourself when you need to leverage the power of baby steps to create change are:

What is this particular stakeholder’s current attitude about the proposed change?

What are the small steps that will take this particular person from his current attitude to where you need him to be?

Can you enlist “evangelists” to advocate the change instead of carrying the water by yourself?

How much change do you require from each person? Does she need to come around entirely to embrace your view? Or is it sufficient to move her OK zone closer toward you, without getting all the way there?

Whether you’re buying new printers, reducing bias…or merging departments, revising reporting relationships, or anything else…consider using the power of baby steps in your change initiative. By investing just a bit of up-front effort, you’ll almost certainly achieve stronger and more widespread support.

[image error]

When Multitasking Makes You Happy and When It Doesn’t

Would you be happier if you spent an hour juggling emails, meetings, and data analysis, or if you spent that hour focused only on data analysis? Which would you enjoy more: a Saturday spent bouncing from running errands, to cooking an elaborate dinner, to playing with the kids, or a Saturday dedicated solely to playing with the kids? In short, how does variety among one’s activities influence happiness? Our research tackles this fundamental question.

To investigate, we conducted a series of experiments among a broad range of participants. After asking them to work on a variety of activities, we measured how happy they felt by combining their answers to these two questions: How happy do you feel right now? And how satisfied do you feel right now?

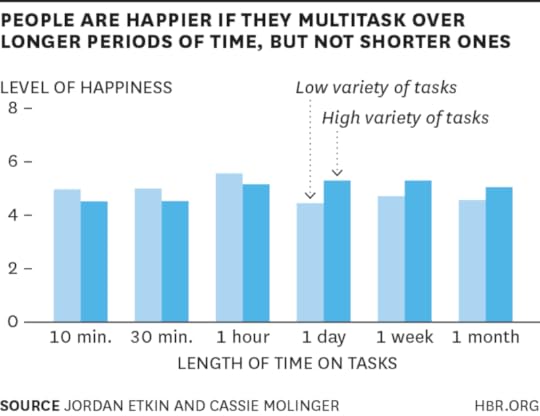

The results were surprising. Whereas participants expected that more variety would always make them happier, when looking back, more variety only made them happier for sufficiently long periods of time — like over a day, a week, or a month. Over shorter time periods, like 10 minutes or an hour, more varied activities actually made people less happy.

In one experiment, for example, we asked a group of college students to spend an hour working on materials from a variety of classes while a different group worked on material from one class. At the end of the hour, we measured how happy these individuals felt, as well as how productive they felt. The students who spent the hour on materials from a variety of classes reported feeling less productive than students who spent the hour on materials from just one class, and this led them to feel less happy.

In another experiment, we asked students to do a series of activities with different types of candy. One group performed a variety of tasks with the candies (they evaluated the taste of the gummy bears, named the jellybeans, and organized the M&Ms by color), while the other group performed the same task across candies (they evaluated the taste of the gummy bears, jellybeans, and M&Ms). All participants had 15 minutes to work on the tasks, and afterwards, we measured how happy and productive they felt. Again, the students who spent 15 minutes doing the same task felt more productive — and happier — than the students who spent the time on a variety of tasks.

Why does spending shorter time intervals on more varied activities make people less happy? The answer has to do with feelings of productivity. People value feeling productive in how they spend their time. When circumstances limit people’s sense of progress or accomplishment, this reduces their happiness. Research has shown that workers who switch between a variety of tasks in a short time period are less productive than workers who stick to a similar set of activities over that same period. Switching between tasks consumes cognitive resources and takes up memory space, which makes people feel stressed and limits their ability to excel at the task at hand. Shorter time periods simply do not provide a sufficient opportunity to compensate for these costs. Thus, increasing the variety among the activities that fill these shorter time periods decreases happiness by making that time feel less productive.

Our findings have clear and practical implications for how people can plan their time in order to feel happier and more productive. Start by scheduling more varied activities into your days, weeks, and months and removing variety from your hours and minutes. Even if the activities themselves can’t be changed (for instance, parents may have to multitask in that hour before getting themselves and their kids out of the door in the morning), simply focusing on the features that minimize the variety among the activities should be sufficient to obtain the resulting boost in happiness. So think about your morning tasks collectively as “getting ready tasks” rather than as a variety of different tasks that need to get done. That will make you happier and the time feel more productive.

This research also provides guidance for how workers’ time should be scheduled to balance dual interests in employees’ productivity and well-being. Although repetition can make workers more productive in the short-term, the lack of stimulation eventually detracts from their happiness. So within an hour, tasks should be kept consistent to increase productivity, but across days, tasks should be varied to maintain stimulation and interest.

So does multitasking increase happiness? This research indicates that it does, but not always. Variety may be the “spice of life” — but not of any given hour.

[image error]

If Your Boss Tells You to Get a Coach, Don’t Panic

How does it feel when you’re told that you need a coach, whether it’s your boss or someone else? For many managers it feels like a kick in the gut, a clear sign that you’re doing something wrong and your job might be in trouble. For others, who might be resistant to coaching in general, it raises questions about whether you really need the extra help.

Having worked with dozens of managers who’ve been in this situation, these reactions are completely natural, especially if the request to work with a coach comes as a surprise. In either case, before you get started with the coaching, you need to work through these feelings so that you can have a positive experience. Here’s how:

The first step is to recognize coaching for what it is: a fantastic opportunity for growth, development, self-insight, and career progression – and an endorsement that the company is willing to invest in you. After all, there are a number of reasons why your boss might want you to be coached, and some are quite positive. Your manager might think you have a great deal of potential and a coach would help you develop it. Your boss might also suggest coaching to fix a particular skill deficit. One of my clients, for example, was asked to work with a coach specifically to focus on presentation skills. Her senior manager planned to give her more exposure to the Board but wanted to make sure she had the confidence and capability to hold her own in that setting.

There are of course situations where coaching is given to a manager because of a performance issue – an inability to deliver certain results, poor project execution, or not getting along with other members of the team. But even in these cases, coaching is an investment, not a punishment. The boss isn’t giving up on you.

The second step is to understand the nature of your resistance or hesitation. Are you opposed to being coached because you’re not sure what you should focus on? Or because you don’t really understand what’s involved in the process? If these are your concerns, take control of the coaching process. Interview the potential coach (if it’s not going to be your boss) and make sure that there’s good chemistry between you two; if not, find someone else. Set clear goals with the coach about what you want to accomplish and how she can be helpful. Engage your boss in regular progress reviews so you get feedback about how you’re doing, and establish a time frame for the coaching (and the achievement of progress) so that it’s not an open-ended relationship. In other words, take the ownership away from your boss and make the coaching experience something that belongs to you. You can also talk to colleagues and friends who have worked with a coach and get a sense of their experience.

You and Your Team

Coaching

Get better at helping your employees stretch and grow.

But if you still don’t think working with a coach is necessary, make a list of reasons why. For example, does your resistance actually stem from an underlying anxiety about what coaching will reveal? A common concern is that the process might uncover issues that people don’t know how to deal with or threaten their self-image. Or maybe these are the reasons running through your mind: “I don’t have time for coaching.” “I’ve been successful so far — why fix something that isn’t broken.” “Coaching often doesn’t work, I’d rather try another approach to development.” “What I really need is better feedback and guidance from my manager.”

Each of these might be a legitimate reason for not wanting to work with a coach. But before you try and make your case, ask your boss why she recommended coaching in the first place. If there are skills she wants you to work on, ask if she would be open to you pursuing a different development approach. For example, you could take a course, or tackle a stretch assignment, or pick up some new responsibilities. If time is an issue, negotiate a development schedule that works for you – or suggest a better time of the year to do the coaching, based on the rhythms of your workplace.

In the end, if your boss still thinks coaching is the best option for you, put aside your resistance and make the most of it. Use it as an opportunity to get more feedback from your boss, and from your subordinates and colleagues as well. Everyone has something to learn, no matter how successful they’ve been in the past and how much potential they have for the future. That’s not to say that coaching is the magic key to success for every manager, but it’s a tool that may be useful and shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. The bottom line is to remember that coaching is an investment – and the more you put into it, the greater the chance that you (and your company) will get a positive return.

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers