Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1318

February 18, 2015

Reinvent Your Sales Process While Still Hitting Your Numbers

If you have a monopoly, then your reward is a quiet life, one devoid of having to deal with competition. But most firms face changing competition, threats to their installed base, and quarterly investor expectations — all of which place sometimes conflicting demands on sales efforts. Sales forces are expected to both:

Maintain the current business: Be predictable and consistent. Because the company relies on existing sources of revenue to keep the business going, sales faces constant pressure to “make the numbers” and focus on the short term. “Nothing happens until you make a sale” and achieve target numbers, and there are typically firm-wide consequences if you don’t.

Adapt to the new: Keep innovating. Current numbers are important, but preparing for future needs creates the necessary foundation for profitable growth. Sales must also generate new sources of revenue and so learn to sell new products, through expanded channels and applications, to new customer segments. This becomes more critical as market life cycles shorten and the time in which companies can maintain product differentiation shrinks.

Some executives refer to these dual requirements as the monkey challenge: in making its way through the competitive jungle, the smart monkey never lets go of one branch (an established means of generating sales and income) until its other hand is on the next branch. The problem is that this view of change is a prescription for inertia rather than adaptation and growth. The pull of current procedures trumps needed changes, and, ironically, many sales executives dig the hole deeper by doing what they always have done. Gartner calls this the Seller’s Dilemma, and research indicates that it now ranks among the bigger challenges facing firms and sales leaders for a number of reasons.

Buying behavior has changed in many markets. Customers via social media have access to more information about suppliers, their products and prices, and others’ experiences. Customers enter the sales cycle in different ways than in the past, creating less pipeline predictability and different selling tasks.

Compressed differentiation characterizes competition in more markets. The differences between products and vendors in many categories are narrower than ever before. In a recent poll of IT buyers, for instance, a majority saw little difference in their vendors’ offerings. A more general poll across product categories is even starker: 80% of managers said they believed their companies had strongly differentiated products, but fewer than 10% of those firms’ customers agreed.

C-Suite changes exacerbate the Seller’s Dilemma. The executives reporting to the CEO have doubled in the past three decades, mostly an increase in functional specialists like CIOs and CMOs, not general managers responsible for cross-functional integration [PDF]. When C-Suites are silo’d, so are resource allocations and front-line capabilities. While technology has seen huge advances in the past decades, sales models have not. In our experience, most sales models and performance practices are the ad-hoc accumulation of years of reactive decisions, often by different managers pursuing different goals.

To resolve the Seller’s Dilemma, start by recognizing and dealing with these core elements.

Disconnected Go-to-Market efforts. There is no such thing as effective selling if it’s not connected to your business strategy. The gap between strategy and sales is getting bigger as life cycles accelerate. Many companies lack processes for linking these important business activities. On average, companies only deliver about 50 to 60% of the financial performance their strategies and forecasts promise; other research indicates that less than 50% of employees in most firms understand their firm’s strategy and — here’s the perverse part — that percentage decreases the closer you get to the customer in responses from sales and service people. Further, chasing “best practices,” a common response when sales stall, can make things worse. Those practices were developed at other companies pursuing different strategies. Keep your eyes on the prize: the point is to have sales execute the tasks inherent in your business strategy, not those of a generic selling methodology or those relevant to a different set of strategic choices.

Selling is more about the buyer than the seller. A key to grasping the next branch is to adapt sales models to evolving buying processes, not ignore or resist them — a big transition for many firms whose marketing, sales-training and -enablement tools, and most selling expenditures focus on inside-out tactics, not a customer-centric process geared to today’s purchase criteria in their markets.

Innovate through experimentation. It’s not the market’s responsibility to accommodate your strategy and sales model. It’s the seller’s responsibility to adapt. That’s why innovation is essential. Companies now typically expect experimentation in R&D and product development. The same should be true in sales. Some firms are even introducing sales innovation teams reporting to the C-Suite. Their charter is to help deal with the monkey challenge: find current opportunities that can be further exploited, identify which go-to-market investments are not delivering results, and put in place new skills and capabilities required for growth

Like most important things in business, much of this is easy to say and hard to do. Any sales force consists of different people and personalities, embedded customer relationships, and diverse capabilities across a portfolio of talent. But if you look closely at videos of monkeys swinging through a jungle, you will see that they do in fact let go of one branch before grabbing the next. The smart ones can calibrate the required leap.

[image error]

Improving Innovation in Africa

Opportunity is on the rise in Africa. New research, funded by the Tony Elumelu Foundation and conducted by my team at the African Institution of Technology, shows that within Africa, innovation is accelerating and the continent is finding better ways of solving local problems, even as it attracts top technology global brands. Young Africans are unleashing entrepreneurial energies as governments continue to enact reforms that improve business environments. An increasing number of start-ups are providing solutions to different business problems in the region. These are deepening the continent’s competitive capabilities to diversify the economies beyond just minerals and hydrocarbon.

Despite this progress, Africa is still deeply underperforming in core areas that will redesign its economy and make it more sustainable. Its reliance on commodities remains its weakest link, causing cyclical trade shocks and welfare losses as the current fall in crude oil price has proven. Despite rosy economic statistics, strikes, riots, and protests are rampant, indicating that growth has not improved the lives of many, especially the young. According to McKinsey, youth unemployment in Africa’s largest economy, Nigeria, is around 50%. With the oil sector contributing more than 90% of the nation’s foreign exchange earnings and three-fourths of its budgetary revenues, the currency has since lost value to the U.S. dollars. Another oil exporter, Angola, introduced austerity measures and revamped its budget as oil price continues to collapse.

Innovation in Africa remains challenged by factors that indirectly stymie access to capital, including property rights, poor technical manpower, and inadequate infrastructure. Yes, in our work, from engineering to herbal medicine to craft, we have seen inventions — such as a local company that remakes automobile engines into electric power generators. But in most of the cases we’ve seen, how to invest to scale such inventions has not been evident. Despite the inventiveness of these entrepreneurs, some operate in the informal economy, without government registration, IP rights, or access to banking. Investors subsequently have a difficult time calculating their valuations. Getting over these hurdles will help Africa move from this invention economy — lots of ideas, but a relative lack of scalable products — into an innovation economy, with competitive local products and services.

Transitioning to an innovative, knowledge-based economy is necessary for sustainable progress. There are pockets of activities with both local and foreign firms working to create innovations within Africa and are facilitating the formation of sector-clusters. From our studies, insights from workshops in more than 82 African universities and companies, and ongoing data collection, we can identify the following clusters:

Information and Communications Technologies (ICT): ICT is driving efficiency in business operations across Africa from mobile payment to integrated banking systems. Major clusters are forming in Lagos, Nairobi, and Kigali. Both foreign-funded options, like the e-commerce site Kaymu, and local ones, like Iroko TV, are demonstrating that opportunities exist in the sector.

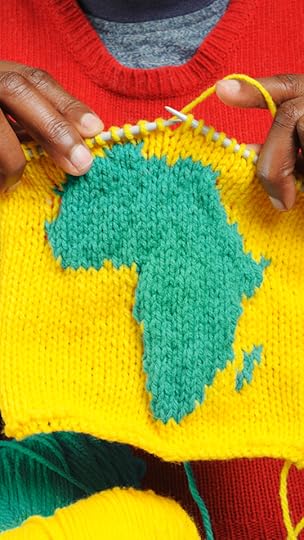

Local Craft: Africa is a land of craft with local artisans involved in leather works for shoes, bags, and fashion. Aba, Accra, and Ouagadougou are some major craft cities. But participants are poorly trained and produce low quality products. The sector needs modernization, and must deploy computer-aided-design tools to enhance quality and automate production for scale to win markets. There are talents that can build African version of Zara, just as Queens of Africa and Naija Princess dolls have knocked Barbie out of first place in Nigeria.

Healthcare/Medicine: Cape Town and Ibadan are promising clusters for this sector, but most African countries are yet to seriously invest in the sector. They import most of their medical systems, vaccines, and drugs including ones like typhoid fever Vi which is royalty-free from NIH.

Engineering/Science: In a continent with arable land and severe hunger, there is need to find effective local solutions to process and preserve food. The same applies to affordable housing, energy, and water. The era of Internet of Things will unlock opportunities in this sector for African entrepreneurs. Cairo, Johannesburg, and Lagos are important clusters emerging. The presence of IBM in Kenya will seed future start-ups in this sector.

Africa needs to nurture and strengthen its natural clusters. Industrial developments will require supporting infrastructure. Providing power, roads, post offices, airports, and seaports will cut the cost of doing business. In addition, Africa needs to develop its manpower. As of 2010, only 3% of Africa’s population attended post-secondary education (PDF). Without manpower development, Africa’s entrepreneurial quality will remain poor.

Africa needs to lessen its dependence on former colonial powers for processing its raw materials, and improve internal trade to give local manufacturing companies more opportunities to grow. (Its interregional trade is currently between 10% and 12%, compared with 40% in North America and 60% in the European Union.) The continent also needs to adjust its legal system; enforcing property rights laws, respecting land rights, and prosecuting violators of software IPs help to seed and attract companies of the future. Finally, Africa needs to improve its investment climate, due to the perception of corrupt public institutions, security, and weakening local currencies. Two reforms that would help meet these needs would be be a pan-African anticorruption institution with the power to prosecute corrupt leaders, and a mandate that countries invest 25% of their foreign exchange earnings on the pillars of knowledge economy — education, technology, and innovation.

Developing innovation ecosystems at regional levels will take a continent-wide effort, since some of the countries are still too weak to go it alone. Such improvements must be seen as a driver in positioning the continent for the post-mineral era. The asymmetry between expanding economic growth and high youth unemployment can only be solved when business ecosystems can grow local champions that can create jobs. By focusing on the factors that allow entrepreneurs to come up with bold ideas and allow investors to transform those inventions into products and services, we can redesign our society.

[image error]

How Great Coaches Ask, Listen, and Empathize

Historically, leaders achieved their position by virtue of experience on the job and in-depth knowledge. They were expected to have answers and to readily provide them when employees were unsure about what to do or how to do it. The leader was the person who knew the most, and that was the basis of their authority.

Leaders today still have to understand their business thoroughly, but it’s unrealistic and ill-advised to expect them to have all the answers. Organizations are simply too complex for leaders to govern on that basis. One way for leaders to adjust to this shift is to adopt a new role: that of coach. By using coaching methods and techniques in the right situations, leaders can still be effective without knowing all the answers and without telling employees what to do.

Coaching is about connecting with people, inspiring them to do their best, and helping them to grow. It’s also about challenging people to come up with the answers they require on their own. Coaching is far from an exact science, and all leaders have to develop their own style, but we can break down the process into practices that any manager will need to explore and understand. Here are the three most important:

Ask

Coaching begins by creating space to be filled by the employee, and typically you start this process by asking an open-ended question. After some initial small talk with my clients and students, I usually signal the beginning of our coaching conversation by asking, “So, where would you like to start?” The key is to establish receptivity to whatever the other person needs to discuss, and to avoid presumptions that unnecessarily limit the conversation. As a manager you may well want to set some limits to the conversation (“I’m not prepared to talk about the budget today.”) or at least ensure that the agenda reflects your needs (“I’d like to discuss last week’s meeting, in addition to what’s on your list.”), but it’s important to do only as much of this as necessary and to leave room for your employee to raise concerns and issues that are important to them. It’s all too easy for leaders to inadvertantly send signals that prevent employees from raising issues, so make it clear that their agenda matters.

In his book Helping, former MIT professor Edgar Schein identifies different modes of inquiry that we employ when we’re offering help, and they map particularly well to coaching conversations. The initial process of information gathering I described above is what Schein calls “pure inquiry.” The next step is “diagnostic inquiry,” which consists of focusing the other person’s attention on specific aspects of their story, such as feelings and reactions, underlying causes or motives, or actions taken or contemplated. (“You seem frustrated with Chris. How’s that relationship going?” or “It sounds like there’s been some tension on your team. What do you think is happening?” or “That’s an ambitious goal for that project. How are you planning to get there?”)

The next step in the process is what Schein somewhat confusingly calls “confrontational inquiry”. He doesn’t mean that we literally confront the person, but, rather, that we challenge aspects of their story by introducing new ideas and hypotheses, substituting our understanding of the situation for the other person’s. (“You’ve been talking about Chris’s shortcomings. How might you be contributing to the problem?” or “I understand that your team’s been under a lot of stress. How has turnover affected their ability to collaborate?” or “That’s an exciting plan, but it has a lot of moving parts. What happens if you’re behind schedule?”)

You and Your Team

Coaching

Get better at helping your employees stretch and grow.

In coaching conversations it’s crucial to spend as much time as needed in the initial stages and resist the urge to jump ahead, where the process shifts from asking open-ended questions to using your authority as a leader to spotlight certain issues. The more time you can spend in pure inquiry, the more likely the conversation will challenge your employee to come up with their own creative solutions, surfacing the unique knowledge that they’ve gained from their proximity to the problem.

Listen

It’s important to understand the difference between hearing and listening. Hearing is a cognitive process that happens internally — we absorb sound, interpret it, and understand it. But listening is a whole-body process that happens between two people that makes the other person truly feel heard.

Listening in a coaching context requires significant eye contact, not to the point of awkwardness, but more than you typically devote in a casual conversation. This ensures that you capture as much data about the other person as possible — facial expressions, gestures, tics — and conveys a strong sense of interest and engagement.

Effective listening also requires our focused attention. Coaching is fundamentally incompatible with multitasking, because while you may be able to hear what another person is saying while working on something else, it’s impossible to listen in a way that makes the other person feel heard. It’s critical to eliminate distractions. Turn off your phone, close your laptop, and find a dedicated space where you won’t be interrupted.

Coaching conversations can take place over the phone, of course, and in that medium it’s even more important to refrain from multitasking so that in the absence of visual data, you can pick up on subtle cues in someone’s speech.

In my experience taking brief, sporadic notes in a coaching conversation helps me to stay focused and lessens the burden of maintaining information in my working memory (which holds just five to seven items for most people.) But note-taking itself can become a distraction, causing you to worry more about accurately capturing the other person’s comments than about truly listening. Coaching conversations aren’t depositions, so don’t play stenographer. If you feel the need to take notes, try writing one word or phrase at a time, just enough to jog your memory later.

Empathize

Empathy is the ability not only to comprehend another person’s point of view, but also to vicariously experience their emotions. Without empathy other people remain alien and opaque to us. When present it establishes the interpersonal connection that makes coaching possible.

A key to the importance of empathy can be found in the work of Brené Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston whose work focuses on the topics of vulnerability, courage, worthiness and shame. Brown defines shame as “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging.” Empathy, Brown notes, is “the antidote to shame.” When employees need your help they are likely experiencing some form of shame, even if it’s just mild embarrassment — and the more serious the problem, the deeper the shame. Feeling and expressing empathy is critical to helping the other person defuse their embarrassment and begin thinking creatively about solutions.

But note that our habitual expressions of empathy can sometimes be counterproductive. Michael Sahota, a coach in Toronto who works with groups of software developers and product managers, explains some of the traps we fall into when trying to express empathy: We compare our issues to theirs (“My problem’s bigger.”), try to be overly positive (“Look on the bright side.”), or leap to problem-solving while ignoring what they’re feeling in the moment.

Finally, be aware that expressing empathy need not prevent you from holding people to high standards. You may fear that empathizing is equivalent to excusing poor performance but this is a false dichotomy. Empathizing with the difficulties your employees face is an important step in the process of helping them build resilience and learn from setbacks. After you’ve acknowledged an employee’s struggles and feelings, they’re more likely to respond to your efforts to motivate improved performance.

When you coach as a leader you don’t need to be the expert. You don’t need to be the smartest or most experienced person in the room. And you don’t need to have all the solutions. But you do need to be able to connect with people, to inspire them to do their best, and to help them search inside and discover their own answers.

[image error]

Visualizing Sun Tzu’s The Art of War

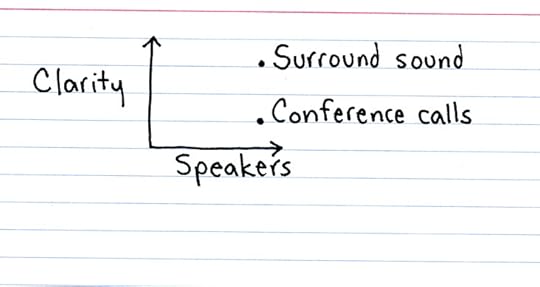

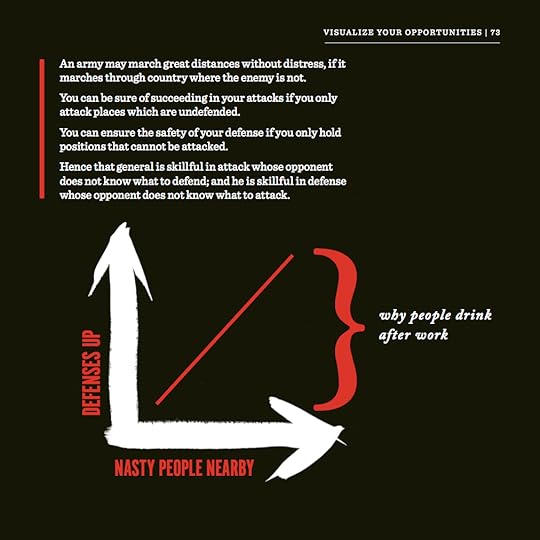

Jessica Hagy is a professional writer and illustrator well-known for her minimalist ink-on-index-card illustrations, which are found at her site Indexed. Hagy’s typical card is a venn diagram or x-y plot of a deceptively simple idea with a punchline. Like this:

One day, when Hagy was cleaning out her bookshelves, she noticed that she owned three copies of The Art of War, Sun Tzu’s legendary primer on winning military strategy. Hagy knew what it was — who hasn’t heard a coach or executive quote it at some point — but she had never read it. So she did.

She was struck with a jolt of inspiration. Each of Sun Tzu’s dictates felt like a caption, like something she could illustrate in her style. After posting a few efforts to her site, her agent called and suggested that she illustrate the entire book, which resulted in the upcoming The Art of War Visualized: The Sun Tzu Classic in Charts and Graphs.

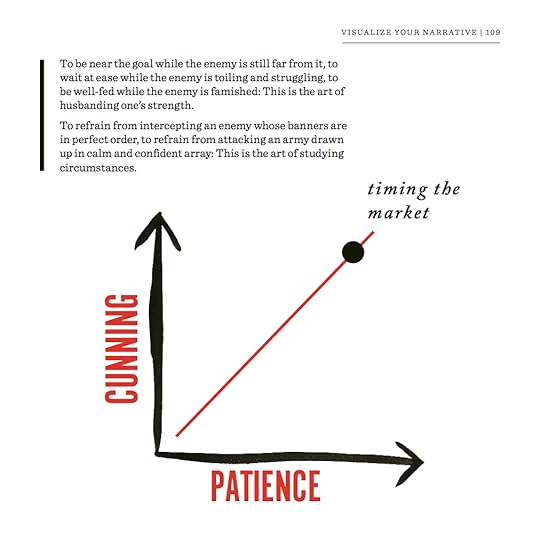

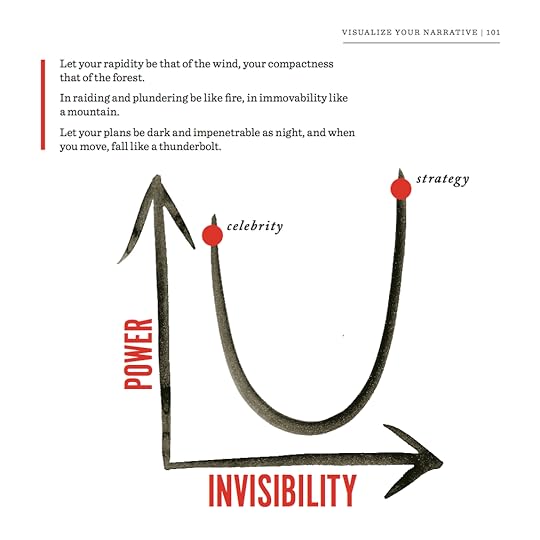

Hagy’s book may appeal to managers in a way the original doesn’t because she’s taken what has always been considered metaphorical business wisdom and visualized it, sometimes literally, as business wisdom. For example, in your next meeting, you can flash a quote of Sun Tzu’s tenets on maneuvering, on “the art of husbanding one’s strength” and “the art of studying circumstances” and explain what that means to the team. Or you can show Hagy’s interpretation of it:

Hagy eschewed her typical index cards for a much bolder style that echoes propaganda posters (and what she interpreted as a propagandist tone in Sun Tzu’s dictates). She achieved an organic feeling by brushing India Ink onto large rag paper. She then made high-res scans of the pages and added text digitally. “Art is in the title,” she says, “it had to be artful to me. The blend of tools felt right: a logical layer on top of an emotional base, like any strategic plan tends to be.”

The choice to work that way reflects what she learned reading the book, too. The digital media layer, for example, is a maneuver, the kind Sun Tzu describes here: “When you surround an army leave an outlet free.” Hagy explains: “Sun Tzu taught me to think about as many angles as possible. The digital text can be manipulated while the graphic structures done in ink remain consistent, thus removing a publisher’s hesitation to take on translating the book.”

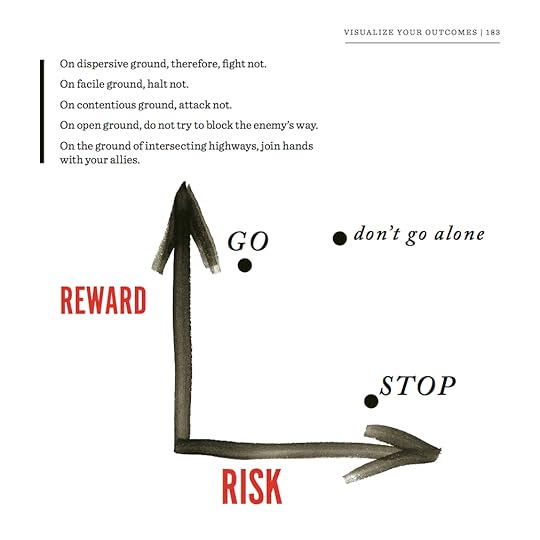

Hagy continues in her tradition of using primarily simple venn diagrams and x-y plots with a singular insight or punchline. Her interpretations are sometimes straight, what she calls visual synonyms, and sometimes they’re new and wry interpretations of the text, what she calls visual redirects. The mix of these two is meant to give the book the “cadence of a conversation,” she says.

For example, she goes with a reasonably straight visual synonym for Sun Tzu’s text on an the risk and reward of attacking:

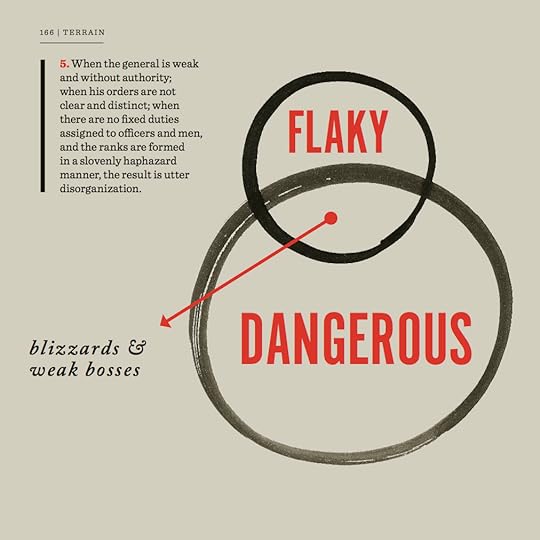

These direct translations may have managers nodding in affirmation. The visual redirects may make managers laugh. For example, Hagy puts a modern office politics spin on Sun Tzu’s meditation on weak points and strong points:

Other times, she thinks from the leader’s perspective, taking on big ideas. From one of Sun Tzu’s more melodic ideas about maneuvering, Hagy was moved to think about the nature of strategy:

Still, Hagy purposefully didn’t think of the book as something for leaders only. “I tried to make the book resonate at all levels. Are my readers CEOs with a 30,000 foot view of the competitive landscape, or are they independent contributors deep in the weeds of office life, fretting about whose turn it is to make the next pot of coffee?” That’s why not all the visuals speak only to the leader. Sun Tzu may have been warning generals about the “utter disorganization” that results when a general is “weak and without authority,” but Hagy sees it, delightfully, from the workers’ perspective:

“The Art of War works so well in part because it treats each conflict as important to overall success,” says Hagy. “Awareness of all levels of strategic behavior is key. Strategy happens at every elevation. I did my best to honor that sentiment.”

[image error]

February 17, 2015

The Mistake Companies Make When Marketing to Different Cultures

Smart consumer businesses are unanimous on the critical importance of “multicultural” growth opportunities. In the U.S., this is especially true now that Millennials — about 43% of whom are not white, according to Pew Research—make up a growing slice of most consumer markets. And it will be even more important for the generation that follows the Millennials; in 2011, non-Hispanic white births dipped under 50% for the first time.

Yet companies still cling to misconceptions about how to market to consumers of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, and their strategies aren’t evolving as quickly as they should. The most significant misstep: Most multicultural strategies and analysis still view consumers mainly via demographics — are you ethnic or not — instead of really trying to understand demand.

Assuming that certain ethnic demographics form the primary market for certain products results in missed opportunities at best — and sometimes it’s just flat-out wrong.

Consider a few examples. Suburban white men consume 80% of hip hop music, even though it’s typically considered a genre aimed at young, urban black Americans. Misconceptions like this aren’t limited to American markets. The Korean soap opera My Love From the Star, for example, has 200 times more views in China than Korea. This last fact was so alarming that China’s highest governing bodies met in Beijing last year to discuss the reasons why Chinese viewers display such high demand for non-Chinese shows.

And this doesn’t just apply to media. We’ve all heard that salsa is more popular than ketchup (in terms of money spent, if not volume), but the people doing most of the buying probably aren’t who you’d think. In previous posts, I’ve written about the concept of superconsumers — people who buy a disproportionate amount of a particular product. In the salsa category, Nielsen data shows that superconsumers are an important market — in fact, the top 10% of salsa consumers drive 50% percent of salsa sales. Interestingly, only 13% of salsa superconsumers are Hispanic. This means there are 5 million households buying lots of salsa who are white. Closer analysis shows they are more than just salsa superconsumers: These same white households also buy more than $1 billion dollars of other Hispanic food products.

Latino households in the U.S. are estimated at 20 million. If there are 5 million white superconsumers of Latino cultural products, is it possible that the market is understated by 25%? If that’s true, it’s a huge opportunity.

For managers, the implications are clear:

First, we need to look beyond demographics. Most likely the markets for all products we think of as culturally specific are understated by a significant amount, which should have big implications for resource allocation.

Second, culture is a choice and not a birthright. Culture, at its core, is a shared passion for distinct common experience. Sports, music, food, fashion, and hobbies are all culture. The currency of culture is how and where you spend your time and money. Ethnicity is not an exclusive passport that lets you in or keeps you out of a culture.

Given that culture is a choice, everyone — the white majority included — can choose to opt in. And while it is fine to share your culture, be careful not to superimpose it on others. As Korean American immigrant from Hawaii, I’ve felt a subtle yet strong pressure from “western business culture” to fake a passion for fine wine and French food, because that’s what well-educated professionals in America are supposed to enjoy consuming. But I didn’t grow up with these things, and I have other preferences. It wasn’t until I saw this as culture and a choice that I felt comfortable saying I enjoyed fermented Kim Chi as much as a fine French reduction.

For those of us who are minorities, recognizing that culture is a choice means being more inclusive. Authenticity is great, but adaptation can be great too. Everyone has the right to travel into new cultures should they choose to. And we as minorities should welcome them (and their dollars) in.

The best place to reach consumers who are multicultural in demand, not just demographics, may be in majority minority cities and markets. Just as superconsumers have a network effect on those around them, living near a large ethnic group has a big influence on what you watch and buy.

The bottom line is that a demographics-based view of culture is far less profitable than a demand-based view. As you create culturally specific products, TV programs, and marketing plans, make sure you’re not leaving money on the table.

[image error]

To Improve Sales, Pay More Attention to Presales

At a time when CEOs are in a constant quest for growth, there is a promising but often overlooked opportunity available close to home: presales. Distinct from marketing and sales operations, presales provides a specific set of activities that lead to qualifying, bidding on, winning, and renewing a deal. In our work with leading companies around the globe, we have found that companies with strong presales capabilities consistently achieve win rates of 40–50% in new business and 80–90% in renewal business—well above average rates.

Presales requires a dedicated team of experts split into roughly two-thirds for technical activities (crafting solutions to customers’ problems) and one-third for commercial activities (managing deal qualification and bid). These activities have two to three times more impact on revenue generation than generating leads. Souping up the presales engine can yield a five-point improvement in conversion rates, a 6–13% improvement in revenue, and a 10–20% improvement in the speed of moving prospects through the sales process. Despite this level of potential impact, presales doesn’t get much airtime in the C-suite—even though it gets a significant chunk of company resources, typically accounting for 30–50% of overall commercial headcount.

If you’d like your organization to take better advantage of presales and reap the advantages that result, here’s how to do so—at each stage of the sales journey:

Identifying Leads

Opportunities have exponentially increased for salespeople, thanks to digital innovations, more systematic RFPs, and the pervasive use of inside sales for lead generation. But more does not equal better. To achieve the ideal qualification rate of roughly 50%, today’s best-practice organizations rely on advanced analytics to identify opportunities early in the sales cycle and prioritize the most desirable ones. They use techniques such as propensity-to-buy modeling, micro-market targeting, account-level opportunity assessment, and churn prediction to separate the high-quality, high-probability opportunities from the rest.

One presales team helped a building materials supplier improve its qualification rate by using order histories of existing customers and analyses of prospective markets. From this data, they developed a list of prospective “ideal customers” most likely to buy the company’s products. Identifying which customers to pursue helped increase bid and bid conversion rates, resulting in a 3–5% improvement in win rates.

Submitting Bids

The root cause was inadequate presales allocation. The company’s technical presales experts were not assigned to the highest-opportunity bids, and there were frequent disruptions to their assignments (e.g., being reassigned to the priority du jour).

To turn things around, the company developed a staffing approach that gave an at-a-glance picture of the availability and skillsets of presales staff a quarter out. It redesigned and simplified its bid review and approval process, and instituted a mechanism that allowed key account managers to provide suggestions and recommendations to the presales team immediately following a bid submission.

This new approach helped the company staff 15 percent more deals with presales resources and anticipate 30 percent more “must win” deals (for the same number of total presales resources). Sales reps’ time on proposal development was cut in half.

Closing Deals

The key to closing deals is presales’ ability to shape conversations with the client to position the company’s solution as the ideal one. This approach is not about developing a “smoke and mirrors” pitch, but rather investing the time to have a deep understanding of the client’s needs (met and unmet) and then highlighting those elements of the solution that can address them.

This is precisely what a European telecommunications company did when it merged its mobile and fixed-line store networks to increase cross-selling opportunities. The company assigned presales “store rangers” (experts in both mobile and fixed-line options) to roam the stores and speak with customers. This had the dual benefit of increasing sales with individual customers and providing training for the full-time store salespeople. On days when a ranger was not on site, stores used videoconferencing to patch in a live presales expert to answer questions, help configure a new service, and even fill out paperwork. After a year, this approach resulted in an increase of 30% in overall sales for the store network.

Renewing Deals

While “presales” might imply that their work is finished once a sale is made, the best companies have presales teams that are active after the sale as well. Great sales reps have always tried to anticipate customer needs and to deliver on them consistently. But top-notch presales teams can help advance from anticipating customer needs to predicting them with greater precision, recommending what the sales force should sell to specific customers, and providing expertise.

Such tactics helped one U.S. insurance company improve customer retention rates by 20%. On presales’ recommendation, the company implemented a new call-center system that went beyond displaying a customer’s history (e.g., tenure and claims record). Additional analytics also assessed the customer’s real-time emotional state and predicted the likelihood of keeping or losing the customer if the issue was not resolved immediately. The system also recommended the conversational style the agent should use, such as a “soothing” or a “just the facts” approach. This helped bridge cultural differences between American customers and

call-center agents based in the Philippines.

Presales can also accelerate sales pipeline velocity by anticipating what will trigger a renewal, standardizing tools to ensure best practices across the sales team, and automating processes to send alerts and recommendations in advance of a contract’s renewal date. Companies that do this well can recommend special offers and promotional deals that will encourage a quick renewal—and even close the deal before an RFP is open to competitors.

When it comes to driving sales growth, quality trumps quantity. And that requires companies to improve the quality of their presales engine.

[image error]

Financial Rewards Make People Suggest Fewer but Better Ideas

Employees have proven to be a valuable source for innovative ideas. Which is why more companies are testing crowdsourcing initiatives and other ways to encourage people to innovate. Offering financial incentives has, for a long time, been one way to do this. But the research on whether rewards actually yield more innovation is mixed. On one hand, rewards can motivate employees to speak up; on the other, they bring in a flood of ideas that aren’t really actionable. In the pages of HBR, we’ve said to focus on culture instead of cash and to avoid offering big rewards for innovation, because luring employees with flashy prizes can kill intrinsic motivation.

In 2010, one large Asian information technology services company decided to run an experiment to see if rewards could actually improve and encourage employee ideas. People could already submit suggestions through an internal system, but the company wanted to test whether rewards would lead to better ideas. The results of the experiment were studied in a recent discussion paper out of the Centre for European Economic Research. The authors, Michael Gibbs, Susanne Neckermann, and Christoph Siemroth, found that when financial rewards were on the table, more people contributed — but on average, each person submitted fewer and better ideas.

The project arose when Gibbs learned that a former student of his at the University of Chicago was in charge of value-creation initiatives at the company (kept anonymous for confidentiality reasons) — and that its internal system (the “Idea Portal”) provided a dataset on employee ideas. He asked if he could use it for research. “This was quite exciting as most research on creativity is field research based on interviews, and is done by psychologists,” said Gibbs. “The opportunity to do statistical/analytics research on new ideas is quite rare.”

The company randomly assigned 19 teams (roughly 11,400 employees) to either a treatment or control group. The treatment group would receive rewards for ideas that were accepted for implementation. These rewards came in the form of points that could be used at an online store. (The points program already rewarded employees for things like good performance, project completion, and job anniversaries.) If the idea was accepted, each member of the contributing team got 2,000 points, which was worth about “2.2% of monthly after-tax salary for lower level employees.” And people could earn more if the client gave a good rating.

Only higher-level management and those managing the rewards program knew about the experiment, which lasted 13 months. Aside from the incentives, nothing changed about the process: Employees submitted ideas through the Portal (individually or in groups of up to three), a supervisor reviewed them, and a panel of senior managers decided which to share with clients. Those accepted by clients would be implemented, and their results tracked.

The hope was that by offering rewards for accepted ideas, employees would focus on ones that directly benefited clients instead of ones that improved internal processes — and that people would go through the Portal instead of trying to implement ideas on their own.

Analyzing the Idea Portal data from before, during, and after the experiment, the authors found that when rewards were introduced, more people participated, but there were fewer submissions per person, and these were higher quality ideas — meaning they were more likely to be shared with a client or implemented, or they had a high estimated profitability — than those from people who weren’t offered rewards. Employees at all levels were able to come up with valuable new ideas. The authors said the fewer ideas per employee couldn’t be explained by motivational crowding out, or the idea that extrinsic motivators (money) undermine intrinsic motivation. Instead, offering pay for accepted ideas seemed to focus people on producing better ones.

“It is often argued that incentives ‘crowd out’ intrinsic motivation, but we found the opposite,” said Gibbs. “Our view is that this issue is often misunderstood. Incentives can easily undermine intrinsic motivation, including creativity, if they reward the wrong outcomes or behaviors. But if they reward the right ones, they certainly can reinforce creativity.”

Younger employees had more ideas than older ones (after controlling for things like tenure), but tenure was positively correlated with the quality. The authors hypothesized two potential effects: those with longer tenure went for “low hanging fruit” while new employees took a more experimental and fresh approach; or longer tenure meant a greater understanding of clients’ strategies and business needs, leading to better ideas. Gibbs said the latter was more consistent with their findings. And although higher level employees generally had higher quality ideas, this effect topped off at the highest managerial ranks. Among executives, whose work is less client-focused, there were fewer ideas and they had less financial impact.

Interestingly, ideas with more authors were more likely to be shared with a client and accepted for implementation, reinforcing the research on the benefits of working in groups (as long as they’re not dumb). And the authors also found that once the experiment was over, people still continued to participate and suggest higher quality ideas, reflecting a “habituation” effect that could be explained by raised awareness of the Portal or perhaps a change in how people thought about innovation.

The paper’s main takeaway is that financial rewards can get employees to innovate, and can possibly fuel a more innovative culture. But if you want ideas that bring actual value to your company, and don’t want to be inundated with a bunch of mediocre ones, tailor the rewards so employees know what to reach for. As for the company in the study, the authors said that after reading their analysis, it rolled out the incentives program to the entire organization.

[image error]

You Might Be the Reason Your Employees Aren’t Changing

We all need a coach. Research we conducted at VitalSmarts shows that 97% of employees readily admit to having a “career-limiting habit” — some behavior that will forever hold them back, unless they can learn to change it.

Consider the example of a CFO we worked with who had his heart set on landing the CEO job when his boss retired. He acknowledged that his tendency to belittle people publicly was holding him back — and he was right. One day, his boss (the incumbent CEO and a former professional athlete) brought him into his office to “coach” him. “You’re arrogant and cruel,” he said. “If you don’t fix those things you’ll never be seen by the board as anything but a technician — and a dangerous one at that.”

The CFO was deeply embarrassed and vowed to change. But, he didn’t. When he was passed over for the CEO job, he resigned in anger.

This example isn’t uncommon. Our research shows that coaching rarely works. Fewer than one in five people who make a concerted effort to change some career-limiting habit actually do it. But even worse, most managers expect their coaching attempts to fail. And worse than that, most recipients of coaching give themselves little chance of real change.

In one study, we asked managers who had just finished coaching a direct report to rate the likelihood that the person would actually change. Fewer than 10% were willing to wager on success. Next, we asked those who had received advice how likely they thought they were to make effective use of it. While they were a bit more optimistic than their bosses, only about a third had high hopes.

Like the ill-fated CFO, many of us are “coached,” but few of us are changed by the experience. Why? Because of these three common — but fixable — mistakes:

Lecturing rather than interviewing. Whether people change is largely determined by why they change. And they are most successful at changing when they choose to change. This is where coaching attempts can create problems. “Coaching” is often imposed rather than invited. Successful coaching assiduously avoids any approach that might provoke resistance to the attempt at change. When we feel something is being imposed on us — even if it’s for our own good — our natural reaction is to resist.

If you’re trying to help someone change, your first consideration must be to approach him or her in a way that enhances, rather than dampens, motivation. Typically, as in the case of the CFO mentioned above, people are already aware that they should change. They may even want to change, but they aren’t changing. So we waltz in with five more good reasons why they should change. We deliver a pithy sermonette and we distract them from choosing to change by instead igniting rebellion.

You and Your Team

Coaching

Get better at helping your employees stretch and grow.

My colleague David Maxfield and I recently did a field experiment that demonstrates this problem and its solution. (See the experiment here.) We had a couple of teenage boys approach smokers in public and ask if they knew smoking was bad for them and if they would like information about why. They had few takers and met a lot of resentment. These folks neither wanted nor needed more information; they already had enough reasons to feel bad.

In the second round, the boys instead approached smokers to ask for a light for their own cigarettes. Not only did the smokers refuse to help the boys smoke, but — in a surprising reversal of reaction — they began lecturing the boys about the evils of smoking. Finally, the boys said, “You’re telling me that I shouldn’t smoke, but what about you?” Most of the subjects then confessed that they wanted to quit. Our experiment replicated one Ogilvy and Mather performed in Thailand; we conducted our own because we wanted to see the effect on a more heterogeneous group of Western smokers. On the day they carried out the original campaign, calls to smoking cessation lines in Bangkok went up by 40%.

It bears repeating: effective coaches ask more questions and give fewer lectures. Your job is to help people uncover and strengthen motives they already have. Think of your coaching conversations more as interviews than as sermons and you’ll be far more successful.

Motivating rather than enabling. We all have an inherent bias in judging what it will take to help people change — overvaluing motivation.

For example, if we’ve got a colleague — like our CFO friend — who demeans people, we assume the problem is a basic character deficit. Perhaps he’s just a sadist. Maybe he gets a kick out of flaunting his power or intellect. If we have a colleague who tends to procrastinate, we might assume the problem is basic laziness. Or, if we have a colleague who avoids making presentations, we might admonish her to “have some courage, for crying out loud!”

The problem is that when we assume that most issues are a simple matter of motivation, we commit what psychologists call the fundamental attribution error — that is, attributing behavior primarily to dispositional factors (“He’s too timid,” “She’s so aggressive,” etc.). Great coaches don’t make this mistake. They start by addressing ability barriers instead. For example, if someone struggles with procrastination, a good coach might suggest tactics for better managing interruptions. In the case of our CFO friend, his coach helped him recognize his own emotional triggers, which eventually helped him overcome his habit of public personal attacks. If you try to motivate people who lack ability, you don’t create change; you create depression.

Focusing on the actor and ignoring the context. We’re often blind to the many forces that create and sustain certain behaviors, so we tend to focus only on the ones we can see — for example, the CFO biting people’s heads off. But this is dangerously naïve and largely ineffective. Of course we need to address the person’s motives and abilities. But we also need to address four powerful sources of influence: fans, accomplices, incentives, and environment. Someone may feel emboldened to behave badly if:

a respected board member gives him a thumbs up after an ill-tempered outburst (fans)

those who disapprove say nothing (accomplices)

he continues to be promoted and rewarded in spite of (or in his mind, because of) his behavior (incentives)

unreasonable goals and deadlines keep him in a constant state of anxiety and fatigue — undermining his emotional reserves (environment)

These four factors can confound even the most resolute people in their efforts to change. But our study shows that when all of these sources of influence are engaged positively in the effort, the likelihood of rapid and sustainable change increases tenfold.

The CFO in this example did eventually change. He went on to become a leader who elicited deep loyalty and affection from many. Success came as he acquired new skills, distanced himself from unhealthy enablers, connected with people who modeled the behaviors he wanted to embrace, and removed himself from a context that overtaxed his ability to stay emotionally healthy.

In short, coaching works when it amplifies one’s own motivation, enhances ability, and equips people to address their context when it inhibits their ability to change. When it fails to do that, it simply doesn’t work.

[image error]

Women Directors Change How Boards Work

We know that getting more women on teams can boost performance. The examples are numerous: Citing private internal research of 20,000 client teams, EY’s vice chair Beth Brooke has said that the more diverse teams had higher profitability and great client satisfaction than non-diverse teams. And professors Anita Woolley and Thomas W. Malone have learned that increasing the number of women on a team also increases its collective intelligence.

Yet when it comes to one of the most important “teams” a company has — its board of directors — the United States seems to have hit a ceiling of about 16% women, with little by way of national efforts by government or business to increase that number.

Whether one agrees with quotas as a mechanism for an increase or not (spoiler: men are less likely to), a new look at Norway, which has a mandatory quota system of 40%, is helpful in understanding why having at least three women on a board is important. And while research about financial performance is still in its infancy — Catalyst has found a strong correlation between the number of women on boards and in the C-Suite and ROI and ROE of company returns — we’re starting to learn more about the important ways women are changing the inner workings of boards.

Aaron A. Dhir, an associate professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School, has done extensive research for his forthcoming 2015 book, Challenging Boardroom Homogeneity: Corporate Law, Governance and Diversity. Professor Dhir did a qualitative, interview-based study of Norwegian corporate directors, looking deeply into the experiences of 23 Norwegian directors, men and women who had appointments both pre- and post-quota. He wanted to understand, from the directors’ point of view, the actual meaning and effects of the quota’s impact, from cultural dynamics and decision making to the overall governance approach of the affected boards. Focusing on the human side of governance, he makes several observations, some familiar and others surprising.

First, many women brought to the boardroom, and to decision making, a different set of perspectives, experiences, angles, and viewpoints than their male counterparts. Board members also observed that female directors are “more likely than their male counterparts to probe deeply into the issues at hand” by asking more questions, leading to more robust intra-board deliberations. Most women appeared to be uninterested in presenting a façade of knowledge and were loath to make decisions they did not fully understand (something recent McKinsey research suggests might be fairly common). Board members observed that female directors tended to have a different style of engagement, seeking the opinions of others and trying to ensure that everyone in the boardroom take part in the discussion.

Outsider status and independence were also particularly powerful forces in board dynamics, helping to open up close ties and expand and rearrange social bonds between directors, the CEO, and high-level management. The quota also forced a movement away from closed social groups and in-group favoritism — that is, people tapping only their own networks. One question for future research is whether women, over time, lose their outsider status and the effects of that status.

Interestingly, Professor Dhir found that the concern about being stigmatized as a “quota woman” was not experienced by the women who became new board members, particularly because there was a critical mass and not token representation.

Taken together, Professor Dhir identified seven consequences of gender-based heterogeneity for boardroom work, board governance, and group dynamics:

Enhanced dialogue

Better decision making, including the value of dissent

More effective risk mitigation and crisis management, and a better balance between risk-welcoming and risk aversion behavior

Higher quality monitoring of and guidance to management

Positive changes to the boardroom environment and culture

More orderly and systematic board work

Positive changes in the behavior of men

This doesn’t mean there weren’t challenges. Some included more prolonged decision-making, less initial bonding, and additional conflicts due to the increase in different perspectives. Management had to get used to being deeply and fully prepared for the questions being asked.

In addition, diverse boards that were not properly managed created distrust and dissatisfaction. In part this is due to a common bias groups have. Homogeneous groups don’t come to better solutions, as Columbia University’s Katherine W. Phillips, the Paul Calello Professor of Leadership and Ethics, and others have found. They’re simply convinced that they did. Heterogeneous groups, on the other hand, come to better solutions. They just don’t think that’s the case.

There is heated discussion about the various mechanisms in place, and proposed, to include more women on boards. Amidst the debate, what seems clear, as Professor Dhir indicates, “the forced repopulation of boards along gender lines has disturbed the traditional order of corporate board governance systems, dislocating established hierarchies of power and privilege in key market-based institutions.” In other words, having more women does change the dynamics of a board and its governance. The Norwegian experience has provided a window into what might happen if and when board leaders and companies elsewhere decide to seriously commit to making sure their boards are truly diverse, moving consciously from homogeneity to heterogeneity.

[image error]

February 16, 2015

Marketing Is Dead, and Loyalty Killed It

So, you’ve worked your way up the corporate ladder to become Chief Marketing Officer. Pat yourself on the back – you deserve it! All done? Good. Now, please accept my condolences. Your job is obsolete, and unless you turn yourself into a Chief Loyalty Officer, you’re sure to eventually be replaced by one.

Want proof? Look no further than Apple’s record-smashing earnings release last month. We all know the colossus of Cupertino has amazing products and is constantly working on new ways to dazzle and disrupt, from the Apple Watch to Apple Pay. But the earnings report makes clear that intense loyalty to the iPhone– 87% loyalty, to be precise – is what really drives its success. Instinctively, we all know that, because we can all think of someone who pre-orders every new iteration of the iPhone before the shine has faded from the previous one. That kind of extreme loyalty inspires confidence in others, which in turn drives new sales – 74.5 million new phones last quarter – without Apple having to lift a finger. Indeed, aside from a few television spots and billboards here and there, Apple pretty much ignores marketing and advertising.

Of course, not every company is Apple. Letting the products do all the talking won’t work for everyone. But here is the takeaway that can work for every brand: try de-emphasizing traditional marketing and focusing on loyalty instead.

For most people, the word “marketing” summons up a single-minded focus on selling products – a one-sided endeavor. But one-sided doesn’t work in a world where social media has given consumers a megaphone just as powerful as that of traditional marketers.

Instead, there is loyalty, which requires communicating brand values that people want to be affiliated with. Consumers today have many options, and more than ever they choose particular brands to communicate something personal about their own beliefs and priorities. The best way to establish and reinforce common values is to create content that’s so highly specific it defines not only the brand, but the customer.

Take Chipotle, the good guys of fast food. Their produce is local, the meat is free of hormones and antibiotics, and their cheese comes from pasture-raised cows. But the company’s reputation for being the socially conscious, thinking person’s lunch is about more than just the food. Last year, the company started its “Cultivating Thought” initiative, in which writers such as Toni Morrison and Malcolm Gladwell write short texts that appear on the company’s cups and a dedicated microsite. The idea didn’t come out of the CMO’s office, or from a hotshot agency – it came about because Jonathan Safran Foer had nothing to read in Chipotle one day. This is loyalty talking, not marketing. Chipotle is devoting significant resources to something that won’t make the company any money directly, but that is an act of good faith, perfectly targeted to its customers.

J. Crew is another company that successfully uses content to define itself and its customer. The company’s blog is a master class in cozy chic, effortlessly affluent and gently outdoorsy. (If this blog were a person, its favorite activity would be sitting around an outdoor fire on a crisp fall evening, roasting homemade marshmallows on fragrant cedar sticks.) Recently, the blog featured a story about the history of the fisherman’s sweater, a nature photographer’s photo essay about working all over the world in one of the brand’s puffy vests, a how-to guide on caring for cashmere sweaters, and studio tours with designers. The content is beautiful, creative, and most importantly, it has a distinct personality that has nothing to do with shilling.

Customers keep coming back to J. Crew, Chipotle, and Apple because being a loyal fan of the brand reassures them that they are succeeding in being a certain kind of person. People expect convenience from a transaction, but what they crave is meaning. A marketer’s thundering from the top of a mountain like the voice of God will be quickly spotted for what it is – a disconnected jumble of hollow words bouncing along the canyon walls. Building loyalty is much harder work, and it requires not only valuing customers, but liking them enough to have a conversation every day. Bringing passion and excitement to that conversation requires genuine enthusiasm for your own products and mission. The Chief Loyalty Officer’s job isn’t about asking, “What should this company say?” It’s nothing less than answering the question, “What should this company be?”

[image error]

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers